Abstract

AN ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEDIEVAL HEALING can expand beyond the confines of textual sources. This is exemplified by the discovery of bloodletting fleams from medieval Oslo, iron tools used in the medical practice of phlebotomy. Based on the archaeological context of these finds, phlebotomy was not undertaken solely in monastic institutions or the elite secular settings of manors and castles in the medieval North, but also in urban residential areas. The material properties of the fleams furthermore provide an insight into the process of venipuncture as well as the embodied experience of bloodletting for both practitioners and patients. The paper positions itself within the theoretical framework of archaeologies of corporeality in order to reflect on the correlation between the practice of bloodletting and cultural conceptions of the body as humoral. The archaeological evidence for bloodletting in urban contexts indicates a widespread conception of the medieval body and its fluid boundaries with the natural environment.

Résumé

Ouvrir la veine : lancettes à saignée à Oslo au Moyen-Âge par Hólmfríður Sveinsdóttir

Une archéologie de la guérison au Moyen-Âge peut aller au-delà des limites des sources textuelles. C’est ce qu’illustre la découverte de lancettes à saignée médiévales à Oslo, des outils en fer utilisés pour les interventions médicales de phlébotomie (prélèvements sanguins). En se basant sur le contexte archéologique de ces vestiges, la phlébotomie n’était pas pratiquée uniquement dans les institutions monastiques ou dans le cadre séculaire privilégié des manoirs et châteaux du nord au Moyen-Âge, mais aussi dans des zones résidentielles urbaines. Les propriétés matérielles des lancettes laissent entrevoir par ailleurs la procédure de ponction veineuse ainsi que l’expérience concrète de la saignée du point de vue des praticiens et des patients. Le papier se place dans le cadre théorique des archéologies de la corporalité afin de réfléchir à la corrélation entre la pratique de la saignée et les conceptions culturelles du corps renfermant des humeurs. Les traces archéologiques de saignée dans des contextes urbains indiquent une conception médiévale largement répandue du corps et de ses limites poreuses avec l’environnement naturel.

Zussamenfassung

Aderschlag: Aderlasslanzetten aus dem mittelalterlichen Oslo von Hólmfríður Sveinsdóttir

Die archäologische Betrachtung der mittelalterlichen Heilkunst kann über die Untersuchung von Textquellen hinausgehen. Ein Beispiel dafür ist die Entdeckung von Aderlasslanzetten aus dem mittelalterlichen Oslo. Diese Eisenwerkzeuge wurden in der medizinischen Praxis der Phlebotomie verwendet. Aus dem archäologischen Kontext dieser Funde geht hervor, dass der Aderlass nicht nur in klösterlichen Einrichtungen oder in den elitären weltlichen Umgebungen von Herrenhäusern und Schlössern im mittelalterlichen Norden, sondern auch in städtischen Wohngebieten durchgeführt wurde. Die materiellen Eigenschaften der Lanzetten geben darüber hinaus einen Einblick in den Prozess der Venenpunktion sowie in die verkörperte Erfahrung des Aderlasses sowohl für die Praktizierenden als auch für die Behandelten. Der Beitrag ordnet sich in den theoretischen Rahmen der Archäologie der Körperlichkeit ein und zielt darauf ab, über den Zusammenhang zwischen der Praxis des Aderlasses und kulturellen Vorstellungen nachzudenken, denen ein humoralistisches Körperverständnis zugrunde liegt. Die archäologischen Belege für den Aderlass in städtischen Kontexten weisen auf eine weit verbreitete Vorstellung vom mittelalterlichen Körper und den fließenden Grenzen zwischen ihm und der natürlichen Umwelt hin.

Riassunto

Entrare nella vena: lancette per salassi nella Oslo medievale di Hólmfríður Sveinsdóttir

Un’archeologia delle guarigioni medievali si può estendere al di là dei confini delle fonti scritte. Ne è un esempio la scoperta nella Oslo medievale di lancette per salassi, strumenti in ferro utilizzati nella pratica medica della flebotomia. In base al contesto archeologico di questi reperti, la flebotomia non veniva praticata esclusivamente negli istituti monastici o negli ambienti elitari secolari dei manieri e dei castelli nel nord medievale, ma anche in aree residenziali urbane. Le proprietà materiali delle lancette danno inoltre un’idea del procedimento di venipuntura oltre che dell’esperienza concreta del salasso sia per i medici che per i pazienti. Questo studio si pone nell’ambito teoretico delle archeologie della corporalità per riflettere sulla correlazione tra la pratica del salasso e le concezioni culturali del corpo come umorale. Le testimonianze archeologiche sul salasso in contesti urbani indica il concetto diffuso del corpo medievale e dei suoi confini fluidi nell’ambito dell’ambiente naturale.

INTRODUCTION

In the lively imagery of the marginalia of the 14th-century Luttrell Psalter [MS 32130], which ranges from the wonderous to the grotesque (Sandler Citation1996), a vivid bloodletting scene has been illuminated in fol 61r (). The procedure, which is witnessed by an extraordinarily large kingfisher on the right, involves a barber-surgeon leaning over his seated patient, in fact standing on his foot, intently focused on the cut he is making in the right forearm with a bloodletting instrument. The patient aids the procedure by holding on to a wooden staff, providing a steady outstretched work-surface for the practitioner, and carrying a bleeding bowl in his left hand, into which he watches his draining blood flow with a worried expression. Such art-historical depictions of bloodletting provide, along with written evidence, valuable information about the process of bloodletting in medieval society. However, archaeological material can further expand upon the medical practice of bloodletting, in this case through the study of preserved bloodletting tools.

Fig 1 Bloodletting scene from the Luttrell Psalter, MS 32130, fol. 61r.

Photograph © The British Library.

Extensive archaeological excavations which have taken place in the town of Oslo since 1970, continue to shed light on life in medieval Oslo from its foundation in the 11th century ad up until when the town was destroyed by fire in 1624 and consequently moved to the other side of Bjørvika bay (Molaug Citation2015). In the 1970s, a pair of bloodletting fleams, specialised instruments for bloodletting, were found during excavations in the Old town of Oslo (Færden Citation1990, 264–66) with a few more potential phlebotomy tools having been retrieved from the area in recent years. The urban context of these finds is noteworthy as the practice of phlebotomy has been closely associated with monastic medicine or high-status contexts in a secular setting. In this article the archaeological evidence for bloodletting practices from the medieval town of Oslo will be studied. The main research questions asked are firstly, what can the archaeological evidence for urban bloodletting inform us about its social context? Secondly, what can the material properties of the objects inform us about the phlebotomy practice? And thirdly, can these objects reflect cultural conceptions of the human body?

THEORETICAL APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY

Rather than viewing the human body as static, an archaeology of the body or corporeality considers its social and cultural dimensions as well as the diversity of past embodied experiences (Hamilakis et al Citation2002; Joyce Citation2005). Rosemary Joyce has suggested that archaeology can provide an important contribution to studies of corporeality, as the field centres on ‘the materiality of human experience’ (Joyce Citation2005, 140). A growing emphasis has been put on the study of corporeal experiences (Hamilakis et al Citation2002, 5), which will here be reflected upon in the case of the bodily practice of bloodletting. In the discussion, the theoretical approach of archaeologies of corporeality is applied to the case study of bloodletting fleams, in order to reflect on cultural conceptions of the human body in the medieval North. The methodology applied here is that of a case study, in-depth research into a particular collection of artefacts of the same type. Gavin Lucas and Bjørnar Olsen have recently called for a reconsideration of the archaeological case study, not as examples, but a ‘site of encounter’ for theoretical discussion (Lucas and Olsen Citation2022).

Historical archaeology has the great benefit of being able to use both written sources and archaeological evidence, not as a sub-discipline meant to confirm or contradict the historical sources but rather by examining in tandem the myriad of material traces from the past preserved to this day, whether those would traditionally be categorised as being of a historical, archaeological or even art-historical nature (for application in medieval archaeology see for example Gilchrist Citation2012; Standley Citation2013). John Moreland has suggested that an in-depth engagement with the material at hand, akin to that of active microhistory, is a particularly useful approach for historical archaeology where all data can be examined, whether text or artefact (Moreland Citation2003, 83). The approach of focusing in-depth on a few objects within an artefact collection is an increasingly common one within historical archaeological studies of the significance of objects within their social context of use (Beaudry et al Citation1996, 273). In the case of material culture studies within historical archaeology, archaeologists such as Eleanor Standley have advocated for the use of artefact analysis in conjunction with the use of other available data, such as written accounts and art-historical evidence, to reflect on the social aspects of the use of medieval artefacts (Standley Citation2013, 1). Beaudry et al. (Citation1996) have proposed an interpretive approach to the subject of material culture within historical archaeology, corresponding to that of interpretive anthropology which allows for a consideration of worldviews within a given historical and cultural context. This approach, which is adopted here, combines the descriptive analysis of the materiality of objects, with their archaeological context as well as their social context, as studied through a critical reading of written sources (Beaudry et al Citation1996, 274–5). In the following section, preserved bloodletting fleams from medieval Oslo are examined and consequently discussed in terms of what they add to our understanding of bloodletting as a bodily practice in a Nordic context.

BLOODLETTING FLEAMS FROM MEDIEVAL OSLO

One of the earliest allusions to bloodletting in Nordic literature is Snorri Sturluson’s mention in Heimskringla of bloodletting being the cause of death of Jarl Eirik in England in 1023 (Jónsson Citation1895, 33; Grön Citation1908, 35). Written evidence indicates that bloodletting was widespread within medieval Norway. A 13th-century example is Magnus the Law-mender’s municipal law on the emergency towing of ships. Along the list of those excused from helping are men who are being cauterised, are in the ‘baðstofa’, ie sauna, or are being bloodlet – ‘eða liggir undir elldi oc lætr brenna sik. eða er maðr i baðzstofo. eða lætr ser bloð [at bloðlati]’ (Keyser and Munch Citation1848, 251). The retrieval of bloodletting fleams from medieval contexts supports the notion that bloodletting was practiced in Norway from the high medieval period onwards.

The fleam can be defined as a metal instrument for bloodletting with a lateral blade. Fleams might constitute the earliest instrument made specifically for phlebotomy, used from antiquity (Thompson Citation1929, 40), but it is considered that prior to its use, flint, wooden sticks or other sharp materials were used for bloodletting (Holmqvist Citation1942, 43; Davis and Appel Citation1979). In England, medieval bloodletting fleams are known from York and Winchester (Ottaway and Rogers Citation2002, 2932). In Scandinavia, bloodletting fleams have most notably been found in monasteries in both Denmark and Sweden (Holmqvist Citation1942; Møller-Christensen Citation1980, 440; 1982, 257–9; Bergqvist Citation2013). A couple of objects have furthermore been found in relation to hospitals or charitable institutions in Sweden (Bergqvist Citation2013, 293) as well as manor houses or castle ruins (Holmqvist Citation1942; Færden Citation1990, 265). However, a few finds have been found in urban contexts, notably in Sigtuna in Sweden and to this assemblage three finds from the medieval town of Oslo in Norway can be added.

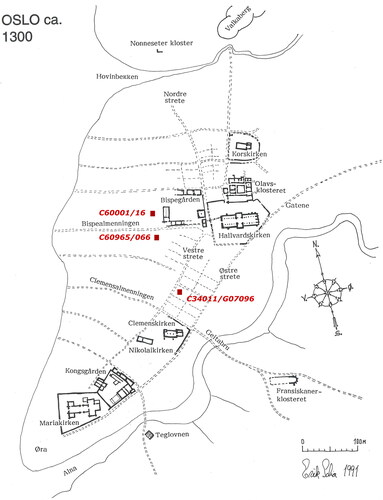

The oldest of the bloodletting instruments from medieval Oslo is a highly corroded iron object (C60965/066) dated to AD 1240–1260, which, based on x-ray analysis, is likely a fragmented bloodletting fleam. The artefact was found in a common backyard of residential buildings, interpreted as a production area (Berge et al forthcoming), at a site south of the medieval wood-paved street of Bispeallmenningen (), which led from the bishop’s quarter to the harbour (Wilster‐Hansen et al Citation2022, 2). Another bloodletting instrument, find C60001/16 (), was retrieved from a waste deposit [layer SL751] north of Bispeallmenningen, where three stone buildings were located in the 14–16th centuries, considered to have belonged to the bishop’s territory (Haavik and Hegdal Citation2020). The third fleam, C34011/G07096 (), was found at Mindets Tomt, located between the St Clement’s church and the bishop’s quarter, in a phase with remnants of wooden buildings dated to AD 1400–1500 (Høeg et al Citation1977, 241–2). No written evidence is preserved regarding the residents of this area, although archaeological evidence suggests that it was residential, where trade and production are likely to have taken place (Schia Citation1991, 44–5). The archaeological site of Mindet’s Tomt is in fact located just east of Vestre Strete, one of the medieval town’s main streets (Schia Citation1991, 35).

Fig 4 Plan of the medieval town of Oslo, c 1300 AD.

Drawing by Erik Schia (Citation1991, 32), with approximate locations of artefacts added by author.

A high- to late medieval dating of bloodletting fleams is comparable to that of other Northern European collections (Holmqvist Citation1942, 45–6; Ottaway and Rogers Citation2002, 2932). The bloodletting fleams have many common traits, such as a looped terminal, rectangular cross section and a u-shaped blade. A looped terminal is similarly a common trait of finds from Scandinavia as well as England (Holmqvist Citation1942; Ottaway and Rogers Citation2002, 2932). The form of the fleam seems to have been consistent through the medieval period but in the 17th and 18th centuries fleams were overtaken by straight double-edged lancets for surgical bloodletting (Thompson Citation1929, 41). Mechanical spring lancets were subsequently developed for bloodletting (Davis and Appel Citation1979). The term and form of the fleam however continued to be used for veterinarian bloodletting as exemplified by the variety of veterinary fleams preserved from the 18th and 19th centuries (Thompson Citation1929, 40).

The ambiguity of historical medical instruments results in their difficult identification in the archaeological record, in part due to the multipurpose use of tools such as knives and scissors (Watson and Gilchrist Citation2021, 114). They are therefore often solely identified as such if they come from medical contexts, such as monastic infirmaries or hospitals (Watson and Gilchrist Citation2021, 109). Four religious houses were located in and around medieval Oslo, the Dominican Olavsklosteret, the Benedictine nunnery (Nonneseter), the Franciscan monastery as well as the Cistercian monastery on the island of Hovedøya (Schia Citation1991). Furthermore, the discovery of a graveyard east of the city limits with numerous examples of leprosy in the osteological material, has been interpreted as evidence for a leprosy hospital located close to the church of St Laurence (Lavranskirken) (Schia Citation1991, 19, 101, 103). However, none of the three bloodletting fleams were found in relation to these institutions but in the centre of the medieval town of Oslo. The archaeological context of these finds can provide an insight into who both the practitioners and ‘patients’ were.

DISCUSSION

The Practitioners and the Patients

Phlebotomy was used to treat all sorts of ailments in different parts of the body. However, bloodletting was not practiced for physical ailments alone but also mental illness. Additionally, the bloodletting of healthy individuals was undertaken as a preventive caution against illness or plagues (Møller-Christensen Citation1980, 439). Periodic bloodletting was practised in monasteries, four times a year for Cistercian monks for example (Møller-Christensen Citation1944, 107). Bloodletting practices are described in Nordic medical books, most notably the work of the Danish physician Henrik Harpestræng (died in Roskilde in 1244) (Møller-Christensen Citation1980). Harpestræng’s work seems to be mostly based on the Salernitan school of medicine, as seen in both his herbal books and writing on bloodletting which bear similarities to the 11th century writings of Odo Magdunensis and Constantinus Africanus, the North African physician who translated Arabic medical texts into Latin (Reichborn-Kjennerud et al. Citation1936, 82–3). Harpestræng is an important source for the criteria of practitioners, how bloodletting should be performed and who should—or more accurately, who shouldn’t—be subjected to the practice (Møller-Christensen Citation1980). While both men and women undertook bloodletting, for both physical and mental problems, Harpestræng describes female-specific reasons for bloodletting, including to aid with pregnancy and birth as well as recommending cupping the sacrum to remove a woman’s lust (Harpestræng Citation1908, 97). This references the Hippocratic belief that women inherently had a higher sexual drive than men, which influenced medieval and Renaissance understanding of female physiology (Peterson Citation2005, 153). The bloodletting of children and older individuals was forbidden according to Harpestræng (Harpestræng Citation1908, 93) and he also advises against the bloodletting of slaves, as in the case of injury, the slave’s master could demand compensation from the practitioner (Harpestræng Citation1908, 93). Other Nordic sources reference kings (Jónsson Citation1895, 33) and bishops (Sigurðsson et al Citation1858, 848) undertaking bloodletting as well as húskarlar or manservants (Sturluson 1872, 250).

Through a comparative analysis of archaeological as well as historical evidence, a more comprehensive understanding of the practice of bloodletting in the Nordic countries can be reached, including who the patients were. Bloodletting fleams in Scandinavia have been found in monasteries as well as castle ruins (Holmqvist Citation1942) and urban areas such as Sigtuna and Oslo. It can therefore be inferred that bloodletting was widespread in different strata of Nordic society in the high and late medieval periods. While bloodletting was routinely undertaken in monastic settings for periodic renewal and cleansing, it was also practised outside the confinement of monasteries by men and women as a solution for both physical and mental problems. However, not all members of society would have undertaken bloodletting, as children and the elderly were advised against the practice, as well as slaves for a more sinister reason, where the financial liability of their bloodletting was considered to outweigh the treatment’s possible benefits. The archaeological context, in conjunction with written accounts, can therefore provide an insight into the identity of the phlebotomists.

Roberta Gilchrist and Gemma Watson have emphasised the unique position of archaeological research into medieval medicine to shine light on little known practitioners in the historical record (Watson and Gilchrist Citation2021, 128). In Johanna Bergqvist’s comprehensive work on medieval medical practices in Sweden, she observes a distinction between phlebotomy and other healing practices undertaken within the realm of physicians. In fact, the archaeological and written evidence indicates that bloodletting was performed by specialised phlebotomists or barbers (Bergqvist Citation2013, 355). Furthermore, the Swedish accounts indicate that the practitioners were both male and female, with a named 16th-century female phlebotomist being referred to as ‘Birgitta åderlåterska’ (Bergqvist Citation2013, 232). Medieval barbers would not only shave and cut the hair of their client but also pull teeth, provide surgical operations and perform bloodletting (Ackerknecht Citation1984, 545–6). Similarly, bloodletting seems to have been undertaken by barber-surgeons in medieval Norway, as a tax was imposed on barbers for bloodletting by King Erik Magnusson in Bergen in 1282 (Keyser and Munch Citation1849, 15). Noticeably, this law uses the word barberr but between 1200 and c 1500, barber-surgeons were simply referred to as barbers (Ackerknecht Citation1984, 546). The Norse equivalent for barber-surgeon, bartskeri (‘beard-cutter’), is first used in 16th-century Icelandic sources, detailing the payment of barber-surgeons for healing syphilis patients with ointments (Sigurðsson et al Citation1857, 290, 363). Ian McDougall has suggested that the mention of an agreement of surgeon Vilhjálmr’s payment in Þorgils saga, in reference to the operation on Þorgils Skarði’s cleft lip in Bergen in 1248, might indicate that a qualified league of barber-surgeons was established in Norway by the 13th century (McDougall Citation1992, 60). The one performing the bloodletting should according to Harpestræng have sharp eyes, have a good knowledge of vein anatomy, and not be drunk (Harpestræng Citation1908, 93–4). In some cases the more academic surgeons in mainland Europe would specifically try to distinguish themselves from the barber-surgeons, who were considered to practise a more ‘lowly’ craft (Hartnell Citation2017, 27). Nonetheless, the requirements for a barber-surgeon would involve skill as well as anatomical knowledge, identifying which condition could be healed through bloodletting and from which vein, and the right time to undertake the procedure.

While it is difficult to determine whether the phlebotomy practitioners in medieval Oslo would have had the title of barber based on the archaeological evidence, the contexts of the finds do provide an insight into the practice of bloodletting, including its social context. An urban context for bloodletting fleams can be made from finds in Sigtuna in Sweden and York and Winchester in England (Holmqvist Citation1942; Ottaway and Rogers Citation2002, 2932). While a central find location in the prospective towns is recorded for both Sigtuna and Westminster, York in particular makes an interesting comparison to the find locations in Oslo. Similarly, the fleams from York were found in residential areas, in tenement plots at Coppergate, and in connection with a religious context, that of Bedern Chapel and the College of the Vicars Choral of York Minster (Ottaway and Rogers Citation2002, 2674, 2687, 2932). The establishment of barber-surgeon guilds, including in late medieval York (Wragg Citation2021), furthermore substantiates how regulated the role of barbers was in Northern Europe at the time and their importance in urban medical care. The identification of the Oslo finds within an urban context, both in the area between St Clement’s church and the bishop’s quarter as well as within the area belonging to the bishop, further substantiates the notion that bloodletting was carried out in all strata of society, as indicated by written accounts. These objects are representative of the medical care accessible in the Old Town of Oslo in the High to Late Middle Ages, and point to the prominence of barbers in that context. As barbers were trained through apprenticeship, in contrast to the university-educated physicians, they were seen as craftspeople (Ackerknecht Citation1984, 546; Wragg Citation2021, 4). This fits with the urban setting of medieval Oslo, where diverse trade and crafts were carried out (Hansen Citation2017), from the shoemakers, smiths and comb-makers to the barbers.

Prior to this study, phlebotomy in a secular setting has been interpreted as being reserved for the social elite, due to the discovery of fleams at manor houses and castles, or being practised within the confinement of health and sanitary institutions, from hospitals to public bath houses (Bergqvist Citation2013, 355). However, the evidence of bloodletting from Oslo, and other towns including York, has been retrieved from residential areas. The archaeological context of the town finds indicates that phlebotomy was undertaken in different strata of society, outside the confines of manor houses and monasteries. The find locations of the Oslo fleams, close to the bustling streets of Bispeallmenningen and Vestre strete, indicate a proximity between barbers and other craftspeople, traders and residents in the area.

Hitting the Vein

Material culture can provide important data for the study of past embodied experience, from jewellery and dress items to artefacts used in bodily practices. Through an interpretive approach, a comparison with written and art-historical sources and the material properties of the fleams discussed here can shine light on the embodied experience of bloodletting. The material properties of the phlebotomy fleams themselves can elucidate the embodied experience of both patient and practitioner as bloodletting was carried out in a medieval Nordic setting. Notably, the object seems to have been held by its looped terminal and, rather than cutting, the object would be swung to precisely hit the lateral blade into the patient’s vein (Færden Citation1990, 264). This corresponds with Harpestræng’s description of the letting of blood as ‘hitting’ (sla) a vein (Harpestræng Citation1908, 93–4). This provides an important insight into the embodied experience of bloodletting of both practitioner and patient.

In terms of written evidence, Harpestræng describes the process of bloodletting in detail, which is equivalent to that of art-historical depictions (see for example, ). The vein should be exposed by tying the arm with a linen band, three or four fingers above the vein. The patient then lets the vein ‘rise’ by holding onto a wooden staff, before the vein is hit to make an appropriately large cut—neither too big nor too small (Harpestræng Citation1908, 94). This is not unlike present-day phlebotomic practice where patients are commonly asked to form a fist to make the veins prominent (World Health Organization Citation2010, 15). Cupping is similarly described to bloodletting in Harpestræng (Citation1908, ch 149–50), by placing the cup on the skin until it swells up, cutting with an iron and then placing the cup again until it fills with blood (Harpestræng Citation1908, 98–9). From textual as well as art-historical sources it is evident that multiple objects were needed to perform bloodletting. This could include a fleam or another bloodletting instrument, a wooden staff held by the patient, a linen cloth wrapped around the arm, a bleeding bowl to both contain and measure the amount of blood, and perhaps also a stool or bench upon which the patient sat. Although no bleeding bowls have been definitively identified from Oslo, small bowls such as a high-medieval pewter dish (C60768/01), 130 mm wide, found in the Old town of Oslo (Klypen K134, context 1037), could possibly have served such a function. Furthermore, the process of bloodletting, as detailed in written as well as depicted in art-historical evidence, reflects the relationship between the barber-surgeon and the patient, who is an active participant in the procedure. In the case of a phlebotomy of the arm, the patient participates by gripping the barber’s staff in one hand, exposing their veins, and in the other holding the bleeding bowl.

An analysis of surgical instruments is also essential to an exploration of the medicinal practice to which they belong, from surgical saws to bloodletting fleams (Hartnell Citation2017, 26). The study of utilitarian objects such as surgical or medical tools as ‘significant possessions’, additionally highlights that artefacts other than elite or religious objects should be viewed as meaningful (Moreland Citation2003, 29, 80, 103). The relationship between the practitioner and their fleam can here be interpreted as an important one. Jack Hartnell has pointed out that surgeons’ instruments were likely of great importance to their owners, as both essential to their practice but furthermore a representation of their expertise and social standing (Hartnell Citation2017). Just how valuable these tools were is indicated by preserved medieval wills which state how tools were passed down from surgeons to their successors (Hartnell Citation2017, 34). The regard to which bloodletting fleams were similarly held can be interpreted from the written evidence. It is noteworthy that Harpestræng lists a criterion for the bloodletting tool, which is simply referred to as an iron (iærn), which he does not for example do in terms of cupping instruments. The iron should be light and shiny, thin and not thick and not long so it doesn’t make a deep cut (Harpestræng Citation1908, 93). The correlation between the length of the blade and the cut made is an essential one, as the practitioner could not make a wound deeper than the blade, which from the preserved tools commonly seems to have been c 10–15 mm long. The bloodletting fleam can be identified as fundamental to the craft of the barber—not too big and not too small, just adequate like the wound they skilfully made.

Of Fleams and Fluids

As emphasised above, the archaeological evidence of bloodletting in medieval Oslo can, through an interpretive approach, elucidate past embodied experience. But can these objects also reflect cultural conceptions of the human body? An archaeology of the body allows for an understanding of the body as a dynamic, not static phenomenon, temporally or cross-culturally, shaped by the social conceptions surrounding it (Joyce Citation2005). A good example of socio-cultural understandings of corporeality is that of the humoral body, which influenced the practice of bloodletting from Antiquity onwards. Classical Greek medical writing and philosophy had theorised that the human body was made of a balance between different humours, the term humour deriving from the Greek word χυμóς for juice or fluid (Nutton Citation1993, 283). As all humours in balance constituted an individual in perfect health, a humoral imbalance was considered the cause of many illnesses. An excess of any humour could be remedied for example through diet or by its partial removal from the body, through purging such as vomiting or by bleeding. Bloodletting was considered an effective remedy to humoral imbalance, as the arteries contained all four humours, although dominantly the humour of blood (Nutton Citation1993, 287).

While the earliest work on the medical implications of humours is ascribed to the Hippocratic corpus, it was Galen of Pergamum (AD 129–c 200/210) who gathered humoral theory into a comprehensive system, where the four bodily humours of blood, phlegm, bile and black bile correspond to the four elements of water, fire, air and earth (Sigerist Citation1961, 317–35; Nutton Citation1993, 286). After classical medical writings were translated into Arabic in the 9th century and as the field of medicine was flourishing along with mathematics and other sciences during the Islamic Golden Age of the 9th–13th centuries, humoral theory became widespread across the Islamic World (Nutton Citation1993, 281–2; Edriss et al Citation2017). This knowledge was later transmitted to continental Europe, making humoral theory influential in European medical practice from the 11th century onwards (Nutton Citation1993, 281–2). Humoral theory places the microcosm of the human body and its humoral constitution within the wider macrocosm, which encompasses the elements of the Earth, seasons, the planets and God (Jónsson Citation1892a, 180–1). The popularity of humoral theory in the medieval context can in part be explained by its suitable adoption to a Christian and Islamic cosmology (Nutton Citation1993, 288). The transmittal of humoral theory to the Nordic countries is reflected in Old Norse manuscripts, the oldest being the Af natturu mannzins ok bloði treatise in Hauksbók, considered to be written between AD 1302 and 1310 (Karlsson Citation1964; Þorgeirsdóttir Citation2018, 35).

Although written evidence supports the notion that humoral theory was known in the Nordic countries from the beginning of the 14th century, it remains unclear how widespread this knowledge was. Hauksbók, which contains the aforementioned Old Norse humoral treatise, Af natturu mannzins ok bloði, has been interpreted as a reflection of the intellectual interests of an Old Norse social élite, with this specific treatise being attributed to a Norwegian scribe most likely copying an Icelandic original text (Jónsson Citation1892b; Jakobsson Citation2007; Harðarson Citation2016; Þorgeirsdóttir Citation2018). This raises the question of whether humoral theory was solely known to a literate Scandinavian elite, such as the audience of Hauksbók, or whether it affected the daily lives of the general public. Could the archaeological evidence for bloodletting help answer this question? Bergqvist observes a distinct difference in the type of bloodletting fleams used in secular and monastic settings in Sweden, which could reflect a disparity in phlebotomic practices in secular and religious settings (Bergqvist Citation2013, 294, 355). Johanna Bergqvist theorised that secular bloodletting might have been a health practice rooted in humoral theory, unlike monastic phlebotomy (Bergqvist Citation2013, 355). Mary K K Yearl has pointed out that from the 12th century onwards monastic bloodletting was seen as recreation, quite literally in the sense of a renewal of the body and its blood, with a connotation to spiritual cleansing (Yearl Citation2011, 217–20). However, it is likely that bloodletting in a monastic setting was done to support humoral balance (Gilchrist Citation2020, 74).

While the Nordic medical texts do not specifically state that bloodletting was performed to aid a humoral balance, the described phlebotomy practice has many common traits with humoral theory. One such is the use of bloodletting to improve mental health, which humoral imbalance was considered to affect. Each person’s humoral make-up, or krasis, was thought to influence their state of mind and personality. For example, a majority of phlegm was considered to make an individual cold and unstable while black bile would result in a withdrawn and tired individual, heavy in spirit (ie melancholic) (Jónsson Citation1892a, 181). The earliest description of bloodletting for mental health reasons in the Nordic countries is from around AD 1200, when the Icelandic doctor Hrafn Sveinbjarnarson (d 1213), considered to have studied in the renowned medical school of Salerno in Italy, is said to have bled a woman to heal her depression (Møller-Christensen Citation1980, 439). Additionally, Harpestræng recommended bloodletting from a forehead vein for both headaches and if one ‘loses their senses’ (Harpestræng Citation1908, 95). In fact, both bloodletting and cupping, where a local suction is created on the skin with the application of heated cups, continued to be practised in Norway until the 19th century to aid mental illness (Ulvik Citation1999, 2489).

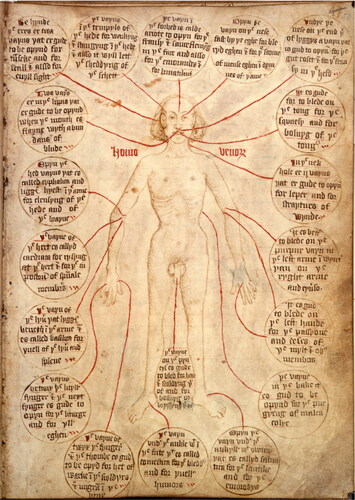

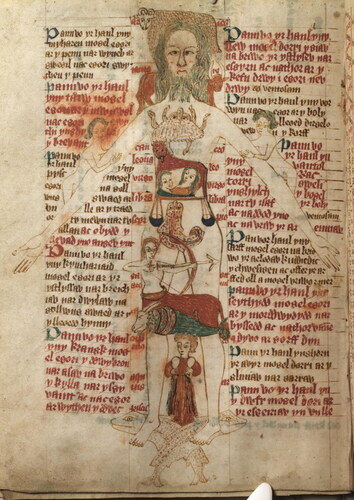

Another correlation between Nordic written accounts of bloodletting and humoral theory, is the affect of the seasons or astrology upon the anatomy in question. The humours were connected to specific body parts with a certain outlet from sensory organs, red bile from the ears, black bile from the eyes, blood from the nose and bile from the mouth (Jónsson Citation1892a, 181–2). The humours would change with the seasons and an individual’s age; phlegm was for example said to increase during winter and be prevalent in childhood and mature age (Jónsson Citation1892a, 182; Þorgeirsdóttir Citation2018, 57). The placement of the human physiology (humours and age) within a wider temporal and astrological context is frequently illustrated in medieval manuscripts (Nutton Citation1993, 288). The correlation between the specific vein drawn during bloodletting and its medical benefits for a particular body part or organ were depicted on ‘phlebotomy man’ illustrations in Europe (), with a few surviving examples from Scandinavia (McDougall Citation1992, 63). Due to the dangers of bloodletting, the right time to undertake it was considered essential for the patient not to bleed out (Davis and Appel Citation1979). Medieval physicians would look towards the presumed astrological associations with the human body, as seen in numerous preserved depictions of the homo signorum or The Zodiac Man (), showing the zodiac sign ruling each body part. Attributing the moon’s attraction of ocean tides with a similar control of the body’s humours, piercing a particular body part when the moon controlled its sign was believed to result in uncontrollable bleeding (Wee Citation2015, 127). This temporal aspect of bloodletting seems to have also affected the practice in a Nordic context as Harpestræng specifies which vein should be drawn in which month (Harpestræng Citation1908, 94–5).

Fig 5 Medical illustration of a vein or phlebotomy man, showcasing where on the body bleeding should be performed, from a 1486 manuscript (Egerton MS 2572, f. 50).

Photograph © The British Library.

Fig 6 A Late 15th-century example of a ‘Zodiac man’, a diagram of the astrological associations with each body part. Page 26 in a Gutun Owain manuscript (NLW MS 3026 C).

Photograph © The National Library of Wales.

Previous works on medieval corporeality have emphasised the importance of noting the diverse multiplicity of bodies rather than an understanding of a universal human body (Kay and Rubin 1996; Barbezat and Scott Citation2019, 1). This is further exemplified by the aforementioned Nordic sources from the Middle Ages, which emphasised the very individualised humoral composition of different bodies. While humoral theory can be seen as broadly general, placing each human body within the macrocosm, it is nonetheless individualised, depending on the specific humoral make-up of the individual in question (Nutton Citation1993, 281). However, an individual’s, and even the humoral composition of a particular body part is not static but fluid, changing with the seasons and the individual’s age as well as the astrological relation with this body part (Barbezat and Scott Citation2019, 1–2).

The adoption of post-humanism within archaeology has allowed for a consideration of the multiplicity of bodily experiences cross-temporally, including boundaries between the human and non-human such as the environment, animals and objects (Crossland Citation2012, 391; Cipolla et al Citation2021, 6). Humoral theory and medieval corporeality are a particularly apt subject area for a post-humanistic approach, as the interconnectivity of the body and the wider cosmos, from the prime elements to the seasons and astrology, is seen as essential (Montroso Citation2022). Stacy Alaimo’s concept of trans-corporeality is particularly fitting here, where the human body is seen as inseparable to its environment, constantly effected by the more-than-human world (Alaimo Citation2010, 2). The fluidity between body and environment in humoral theory is furthermore emphasised by descriptions of the microcosm of the human body as reflecting the natural environment, with the humours representing a landscape within. An example of this from Hauksbók is a description of the watery humour phlegm, which surrounds blood like the great ocean around the earth’s globe (Jónsson Citation1892a, 181).

Regardless of whether the practitioners and patients of phlebotomy would have associated the practice with humoral theory, it can be inferred that the bodily practice was evidently rooted in a culturally specific medical understanding of the body. Therefore the identification of bloodletting tools in urban contexts in the medieval North is evidence for cultural conceptions of the human body. An archaeology of the body explores the effect of material culture in forming and reshaping an individual’s culturally specific perception of their body (Watson and Gilchrist Citation2021, 109). In that vein, bloodletting fleams can be viewed as playing a role in the habitual bodily practices that shaped an individual’s perception of their body. By hitting a vein and allowing its bodily substance to flow into the outside world, these objects could actively participate in this entangled relationship between the medieval body and its environment.

CONCLUSION

The archaeology of medieval medicine adds a valuable insight to the historical record, as it can provide a glimpse into the embodied experience of patients and the role of practitioners as well as medieval understandings of the human body (Watson and Gilchrist Citation2021, 128). The archaeological evidence of bloodletting from the urban context of medieval Oslo elucidates how widespread the bodily practice of bloodletting was in different strata of society. Further archaeological evidence could expand upon urban healthcare in the medieval North, including other medical objects preserved from medieval Oslo. In addition to the fleam, a further surgical tool, a scalpel, was found during the excavation at Mindets Tomt (C34011/G 10031). This object had a triangular-shaped blade, common for scalpels from the 11–16th century, sharp at its point and wider at the base (Thompson Citation1929, 4–5). Additionally, ointments have been found in the medieval town of Oslo, such as the remains of an anti-septic salve contained in a small wooden box (C60005/055) and found in a latrine situated to the south of Bispegata (AD 1275–1350) (Nordlie et al Citation2020, 342–3). The procurement of ointments seems to have fallen within the realm of the medical care provided by barbers (Ackerknecht Citation1984, 545). Not only do the bloodletting fleams discussed here give an insight into urban medical care in the high to late medieval period but also denote that a certain conception of the human body—as fluid in a multitude of ways—permeated medieval Nordic society.

As elucidated here, archaeological research can add value to discussions on medieval corporeality. An example of this is burial customs identified by Roberta Gilchrist as a way of healing the dead, a rite which is not described in extant written evidence but provides a new insight into medieval understanding of the body, health and the life cycle (Gilchrist Citation2008, Citation2012; Watson and Gilchrist Citation2021, 128). While medieval conceptions of the body are hard to access through the archaeological record alone, the record does provide a unique access to bodily practices and an insight into the lived experience associated with them—including through interactions with objects. The material properties of bloodletting fleams give a valuable insight into the bodily experience of both patient and practitioner. Material culture can be identified as playing an important part in bodily practices in everyday life, including the perception of one’s body (Crossland Citation2012, 391). Bloodletting fleams are not only passive reflections of medieval corporeality but could themselves play an active role in an understanding of the human body as fluid in nature—directly perceived by the patient watching their blood flow into a bleeding bowl.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ackerknecht, E H 1984, ‘From barber-surgeon to modern doctor’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 58:4, 545–53.

- Alaimo, S 2010, Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self, Bloomington (Indiana): Indiana University Press.

- Barbezat, M D and Scott, A M 2019, ‘Introduction: bodies, fluidity, and change’, in M D Barbezat and A M Scott (eds), Fluid Bodies and Bodily Fluids in Premodern Europe: Bodies, Blood, and Tears in Literature, Theology, and Art, Leeds: Arc Humanities Press (Borderlines), 1–14.

- Beaudry, M C, Cook, L J and Mrozowski, S A 1996, ‘Artifacts and active voices: material culture as social discourse’, in C E Orser (ed), Images of the Recent Past: Readings in Historical Archaeology, Walnut Creek (California): Alta Mira Press, 272–310.

- Berge, S, Haugan, K Ø, Holmen, K O, et al forthcoming, Follobanen Bispegata. Gamlebyen, Oslo (NIKU Rapport), Oslo: Norsk Institutt for Kulturminneforskning.

- Bergqvist, J 2013, Läkare och läkande: Läkekonstens professionalisering i Sverige under medeltid och renässans, Lund: Univ (Lund Studies in Historical Archaeology, 16).

- Cipolla, C N, Crellin, R J and Harris, O J T 2021, ‘Posthuman archaeologies, archaeological posthumanisms’, JoPH, 1:1, 5–21.

- Crossland, Z 2012, ‘Materiality and embodiment’, in D Hicks and M C Beaudry (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 386–405.

- Davis, A and Appel, T (eds) 1979, Bloodletting Instruments in the National Museum of History and Technology, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Edriss, H, Rosales, B N, Nugent, C, et al 2017, ‘Islamic medicine in the middle ages’, American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 354:3, 223–9.

- Færden, G 1990, ‘Metallgjenstander’, De arkeologiske utgravninger i Gamlebyen, Oslo. 7: Dagliglivets gjenstander; Del 1. Arkeologiske utgravninger i Gamlebyen, Oslo, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Gilchrist, R 2008, ‘Magic for the dead? The archaeology of magic in later medieval burials’, Medieval Archaeology, 52:1, 119–59.

- Gilchrist, R 2012, Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course, Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Gilchrist, R 2020, Sacred Heritage: Monastic Archaeology, Identities, Beliefs, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grön, F 1908, Altnordische Heilkunde, Harlem: Erven F Bohn.

- Haavik, A and Hegdal, H 2020, Follobanen 2015 Områdene Nord for Bispegata (NIKU Rapport 102), Oslo: Norsk Institutt for Kulturminneforskning.

- Hamilakis, Y, Pluciennik, M and Tarlow, S 2002, ‘Introduction: thinking through the body’, in Y Hamilakis, M Pluciennik, and S Tarlow (eds), Thinking through the Body: Archaeologies of Corporeality, New York: Springer Science + Business Media, 1–22.

- Hansen, G 2017, ‘Domestic and exotic materials in early medieval Norwegian towns: an archaeological perspective on procurement and consumption’, in Z T Glørstad and K Loftsgarden (eds), Viking-Age Transformations: Trade, Craft and Resources in Western Scandinavia, 1st ed. New York: Routledge, 59–94.

- Harðarson, G 2016, ‘Old Norse intellectual culture’, in S G Eriksen (ed), Intellectual Culture in Medieval Scandinavia, c 1100–1350, Turnhout: Brepols, 35–73.

- Harpestræng, H 1908, Gamle Danske Urtebøger, Stenbøger og Kogebøger, København: H H Thieles Bogtrykkeri (Udgivne for Universitets-Jubilæets Danske Samfund).

- Hartnell, J 2017, ‘Tools of puncture: skin, knife, bone, hand’, in L Tracy (ed), Flaying in the Pre-Modern World: Practice and Representation, Cambridge: D S Brewer, 20–50.

- Høeg, H I, Liden, H -E, Liestøl, A, et al 1977, De arkeologiske utgravninger i Gamlebyen, Oslo. 1: Feltet ‘Mindets tomt’, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Holmqvist, W 1942, ‘En gammal hälsokur och dess instrument’, Situne Dei. Sigtuna Fornhems Årsbok 1942, 41–50.

- Jakobsson, S 2007, ‘Hauksbók and the construction of an Icelandic world view’, Saga-Book, 31, 22–38.

- Jónsson, F (ed) 1892a, Hauksbók: Udgiven Efter de Arnamagnæanske Håndskrifter No 371, 544 og 675, 4 ̊ Samt Forskellige Papirshåndskrifter, Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskrift-Selskab.

- Jónsson, F 1892b, ‘Indledning’, in F Jónsson (ed), Hauksbók: Udgiven Efter de Arnamagnæanske Håndskrifter No 371, 544 og 675, 4 ̊ Samt Forskellige Papirshåndskrifter, Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskrift-Selskab, i–cxxix.

- Jónsson, F (ed) 1895, Heimskringla: Nóregs konunga sǫgur af Snorri Sturluson, København: (STUAGNL, 23).

- Joyce, R A 2005, ‘Archaeology of the body’, Annual Revie of Anthropology, 34:1, 139–58.

- Karlsson, S 1964, ‘Aldur Hauksbókar’, Fróðskaparrit: Annales Societatis Scientiarum Færoensis, 13, 118–20.

- Kay, S and Rubin, M (eds) 1996, Framing Medieval Bodies, Paperback ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Keyser, R and Munch, P A (eds) 1848, Norges Gamle Love II, Christiania: Chr Gröndahl.

- Keyser, R and Munch, P A (eds) 1849, Norges Gamle Love III, Christiania: Chr Gröndahl.

- Lucas, G and Olsen, B 2022, ‘The case study in archaeological theory’, American Antiquity, 87:2, 352–67.

- McDougall, I 1992, ‘The third instrument of medicine: some accounts of surgery in medieval Iceland’, in S Campbell, B Hall, and D Klausner (eds), Health, Disease and Healing in Medieval Culture, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 57–83.

- Molaug, P B 2015, ‘From the farm of Oslo to the townyard of Miklagard’, in I Øye, I Baug, J Larsen et al (eds), Nordic Middle Ages — Artefacts, Landscapes, Society: Essays in Honour of Ingvild Øye on her 70th Birthday, University of Bergen archaeological series 8, Bergen: University of Bergen, 213–26.

- Møller-Christensen, V 1944, Middelalderens Lægekunst i Danmark, København: Einar Munksgaard.

- Møller-Christensen, V 1980, ‘Årelating’, in F Hødnebø (ed), Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder, Oslo: Gyldendal, 438–40.

- Møller-Christensen, V 1982, Æbelholt kloster, København: Nationalmuseets forlag.

- Montroso, A S, 2022, ‘Medieval posthumanism’, in S Herbrechter, I Callus, and M Rossini (eds), Palgrave Handbook of Critical Posthumanism, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 101–22.

- Moreland, J 2003, Archaeology and Text: Duckworth Debates in Archaeology, London: Duckworth.

- Nordlie, E, Haavik, A and Hegdal, H 2020, Follobanen 2015 Områdene Sør for Bispegata (NIKU Rapport 103), Oslo: Norsk Institutt for Kulturminneforskning.

- Nutton, V 1993, ‘Humoralism’, in W F Bynum and R Porter (eds), Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine, London: Routledge, 281–91.

- Ottaway, P and Rogers, N 2002, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Medieval York, 17/15, York: Council for British Archaeology for York Archaeological Trust.

- Peterson, K L 2005, ‘Re-anatomizing melancholy: burton and the logic of humoralism’, in E L Furdell (ed), Textual Healing: Essays on Medieval and Early Modern Medicine, Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions, Leiden: Brill, 139–68.

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, I, Grøn, F and Kobro, I 1936, Medisinens Historie i Norge, Oslo: Grøndahl & Søns Forlag.

- Sandler, L F 1996, ‘The word in the text and the image in the margin: the case of the Luttrell Psalter’, The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 54, 87–99.

- Schia, E 1991, Oslo innerst i Viken: Liv og virke i middelalderbyen, Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Sigerist, H E 1961, A History of Medicine, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sigurðsson, J, Þorkelsson, J, Ólason, P E, et al 1857, Diplomatarium Islandicum IX (1262–1536), Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag.

- Sigurðsson, J, Vigfússon, G, Bjarnarson Þ, et al (eds) 1858, Biskupa sögur, I. b, Copenhagen: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag.

- Standley, E R 2013, Trinkets and Charms: The Use, Meaning and Significance of Dress Accessories, 1300–1700, Oxford: Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford Monograph 78.

- Sturluson, S 1872, Heimskringla eða Sögur Noregs Konunga III, eds Linder, N and Haggson, K A, Uppsala: W Schulte Reprint of 1868 Edn.

- Thompson, C J S 1929, Guide to the Surgical Instruments and Objects in the Historical Series with Their History and Development, London: Taylor and Francis.

- Ulvik, R J 1999, ‘Årelating som medisinsk behandling i 2500 år’, Tidsskriftet for Den norske legeforening, 119, 2487–9.

- Watson, G L and Gilchrist, R 2021, ‘Objects: the archaeology of medieval healing’, in R Cooger (ed), A Cultural History of Medicine, London: Bloomsbury Academic, 107–30.

- Wee, J Z 2015, ‘Discovery of the Zodiac man in cuneiform’, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 67, 217–33.

- Wilster‐Hansen, B, Mannes, D C, Holmqvist, K L, et al 2022, ‘Virtual unwrapping of the BISPEGATA amulet, a multiple folded medieval lead amulet, by using neutron tomography’, Archaeometry, 64:4, 969–78.

- World Health Organization 2010, WHO Guidelines on Drawing Blood: Best Practices in Phlebotomy, <https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44294> [accessed 28 October 2022].

- Wragg, R D (ed) 2021, The Guild Book of the Barbers and Surgeons of York (British Library, Egerton MS 2572): Study and Edition, 1st ed., Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer.

- Yearl, M K 2011, ‘Bloodletting as recreation in the monasteries of medieval Europe’, in F E Glaze and B Nance (eds), Between Text and Patient: The Medical Enterprise in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Firenze: SISMEL, Edizioni Del Galluzzo (Micrologus’ Library, 39), 217–44.

- Þorgeirsdóttir, B 2018, ‘Humoral theory in the Medieval North: an Old Norse translation of Epistula Vindiciani in Hauksbók’, Gripla, 29, 35–66.