Abstract

Two silver beakers now in the collection of the Denver Art Museum bear some of the most complex iconography known from the ancient Andes. The vessels are stylistically associated with Lambayeque, a culture that at its greatest extent thrived in the coastal valleys between Chicama and Piura from the 8th–14th centuries. Based on recent technical and iconographic studies of the vessels, this paper sheds light on metalworking, ceremonial behavior, cosmology, and funerary practices in the centuries between the fall of the earlier Moche culture and the rise of the Chimú state.

Dos vasos de plata ahora en la colección del Denver Art Museum poseen una de las más complejas iconografías conocidas de los antiguos Andes. Estos vasos están estilísticamente asociados con Lambayeque, una cultura que en su mayor expansión prospero entre los valles costeños de Chicama y Piura desde los siglos VIII al XIV. Basado en recientes estudios técnicos e iconográphicos de estos vasos, este articulo arroja luz sobre el trabajo en metales, comportamiento ceremonial, cosmología, y prácticas funerarias en los siglos entre la caída de la cultura Moche y el levantamiento del estado Chimú.

One of the signal developments of the late Middle Horizon (AD 600-1000) and Late Intermediate (AD 1000-1470) periods on Peru’s North Coast is the rise of the use of gold and silver drinking vessels. This development speaks to both a re-orientation of ritual practice in the wake of the Middle Horizon period and a substantial increase in the access to, and production of, objects made of these metals. Two silver beakers now in the collection of the Denver Art Museum (1969.302 and 1969.303; ) bear some of the most complex iconography known from this period. Both beakers are Lambayeque in their stylistic and cultural affiliation. The Lambayeque culture (AD 750-1375) succeeded the earlier Moche culture (AD 100-800) and at its apogee spread to multiple valleys along the North Coast from Piura to Chicama (Aimi et al. Citation2017; Fernández Alvarado and Wester La Torre Citation2014). The political organization of Lambayeque has been described as a non-state society made up of dispersed ceremonial centers (Kosok Citation1965:178; Mackey Citation2011), but its homeland was the Lambayeque Valley. Its ceramic style was complex, influenced by earlier Moche culture and highland Wari (Shimada Citation1990:317).

Figure 1. Two Lambayeque silver beakers in the collection of the Denver Art Museum (left, 1969.303; right, 1969.302). Photograph courtesy Denver Art Museum.

Elaborate drinking practices have a long tradition in Peru, and the Denver vessels’ beaker-with-flared-rim shape likely originated in the south-central Andes and spread more broadly in the Middle Horizon. During the Inca period, beakers were made of different materials, including ceramic; those made of wood were called keros, and those in gold and silver were known as aquillas. In this article, the vessel is referred to as a beaker.Footnote1 Drinking vessels were closely associated with rulership: they were markers of social distinction, but they were also critical components of rituals that linked the living—and inevitably the dead—as these items ultimately were placed in burials.

The collapse of the Moche polity ushered in a period of greater cultural fluidity on the North Coast, and “foreign” elements were introduced, including new vessel types such as flared beakers. Drinking vessels were important in Moche times—think, for example, of both actual goblets and those that appear in a ritual scene on fineline vessels known as the Sacrifice Ceremony (Donnan and McClelland Citation1999:Figure 4.29)—but in post-Moche times high-status vessels became increasingly abundant in rich burials, and they were often made of silver and gold, rather than ceramic.

The site of Batán Grande (Bosque de Pómac), for example, can be taken as a case in point. A major Lambayeque center in the La Leche drainage, Batán Grande is known as the capital of Sicán, a specific polity within the broader Lambayeque cultural sphere. Shimada (Citation1990:299) has proposed a three-phase chronological sequence for Sicán: Early (AD 700-900); Middle (AD 900-1100) and Late (AD 1100-1375), this last period ending with the Chimú conquest of Lambayeque. Batán Grande became a hub for metal production of epic proportions and vast numbers of objects were produced from its smelting furnaces and workshops (Merkel and Velarde Citation2000; Shimada Citation2000:56). One tomb—looted in the 1950s but surely one of the wealthiest at the site—included some two hundred gold and silver beakers of various sizes (Carcedo Muro de Mufarech and Shimada Citation1985:62–63). It is most likely that the two silver vessels under discussion here () were produced during the Middle Sicán period or perhaps slightly later.

Colonial-period accounts underscore the importance of drinking vessels in later periods on Peru’s North Coast. During the Chimú reign (AD 1000–1470), silver drinking and serving vessels became increasingly prominent. In the list of objects looted c. 1558–1559 from Huaca Yomayoguan, a monumental structure at the Chimú capital of Chan Chan, silver cups, jars, and pitchers made up almost 87% percent of the total registered bullion (Ramírez Citation1996:126–127). This shift in both the quantity and the material speaks to an evolution in ritual practice and beliefs.

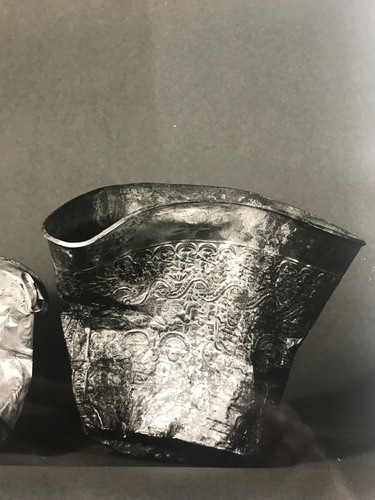

The present study is the outgrowth of earlier research on the two silver vessels in the Denver Art Museum presented by the authors in 2002 (Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2002). As noted at the time, the two vessels have closely linked iconographic programs. The first of the two vessels (called here Denver 1, or the Water Channel Beaker, ) was published by the authors in 2013 (Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013) and will be briefly summarized here. Since that time, other publications have appeared that have addressed the iconography of the two Denver vessels briefly, as well as related works, including a flaring beaker now in the collections of the Museo de Oro del Perú, Lima ( and ).Footnote2 The present study will focus on the second vessel in the Denver Art Museum’s collection, here called Denver 2 or the Medallion Beaker (), and will examine its technological features and iconography with the aim of deepening our understanding of Lambayeque metalworking and ritual practice.

Figure 2. Unknown Artist, Double-walled Silver Beaker with Mythological Scene (The Water Channel Beaker or Denver 1). Hammered silver, 6 × 5.5 × 4.5 in. (H. 15.5 cm). Denver Art Museum: Gift of Frederick and Jan Mayer; 1969.302). Photograph courtesy Denver Art Museum.

Figure 3. Beaker now in the Museo de Oro, Lima (M-1947), prior to restoration (detail). The American Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Junius Bird Archive. Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History.

Technological Features of the Denver Beakers

The two Denver silver beakers were reportedly part of a large find of silver vessels and disks on Peru’s north coast around 1965.Footnote3 Both vessels were acquired by the Denver Art Museum in 1969 via the art market. The Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1; H. 15.5 cm), was a museum purchase (1969.302) and the other, the Medallion Beaker (Denver 2; H. 16.8 cm), was a gift of Frederick Mayer (1969.303). Both beakers have a pouring lip, type of spout to facilitate pouring or possibly drinking, and were constructed of a similar silver alloy. Pouring vessels, while not common, were in use in the Andean region since at least the beginning of the Common Era (see, for example, a Paracas vessel with a pouring lip in the collections of the Met, acc. no. 62.266.76).Footnote4

Thanks to the generosity of Victoria Lyall, curator of ancient American art at the Denver Art Museum, we were able to study the two vessels at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the spring of 2019, following the close of the Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas exhibition, where they were featured (Pillsbury et al. Citation2017). Analyses were conducted by Federico Carò, Department of Scientific Research, and Caitlin Mahony, Department of Objects Conservation, with additional support from her colleagues in that department, including Sara Levin and Ellen Howe. The two vessels were constructed from sheet metal bearing comparable amounts of silver. Both vessels were shaped by repeatedly hammering and annealing sheet to achieve the vessel form, and then the repoussé was added.

Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1)

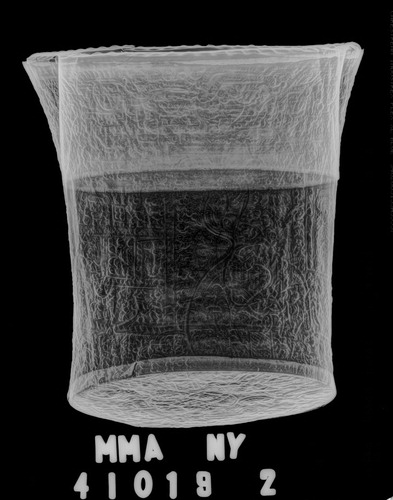

This vessel (), the shorter of the two beakers, is constructed of three separate pieces: a hollow cylinder for the main section of the vessel; a flat disk with a short cuff that sleeves into this cylinder; and a third piece over the upper third of the cylinder (a sort of cuff), shaped and repoussed separately and then attached with solder, creating a double wall on this portion of the beaker, with a 4.5 cm wide, 4.5 cm deep spout for pouring or drinking (replaced with sterling silver in modern times) (). Analysis of a cross-sectioned sample of the hammered sheet collected from the “cuff” revealed a composition of approximately 90.4% silver, 7.4% copper, and 1.9% lead, with traces of bismuth (0.2%), and gold (0.1%) (Carò Citation2019; Mahony Citation2019).Footnote5 Non-invasive X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) analysis indicates that the three separate silver pieces have comparable alloy compositions.

Figure 6. X-ray image of the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1; 1969.302). Image prepared by Caitlin Mahony, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

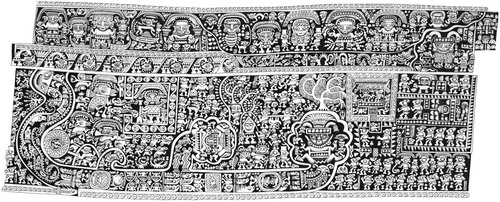

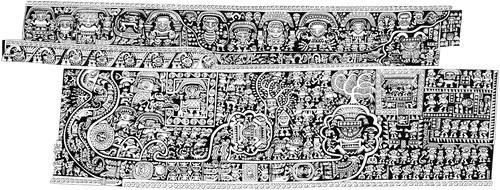

Lambayeque in style,Footnote6 Denver 1 presents elaborate repoussé and chased imagery, laid out using lightly etched guidelines on the surface of the silver. The iconography features a prominent water channel undulating across two-thirds of the center section of the vessel, with supernatural figures and creatures in the channel, and an architectural enclosure, trees, hunting scenes, and other themes above it (). The water channel continues onto the base, which is also embossed (). On the far right of the rollout drawing () a procession leads to an architectural structure with a prominent roof crest. The upper register (the “cuff”) is populated with supernatural figures, including a priestess with two streamers from her headdress, seen on the far right of the rollout drawing.Footnote7 It should be noted that this vessel had been damaged in modern times and was reconstructed at the Denver Art Museum.Footnote8 The “cuff” is in comparatively better condition than the cylinder, suggesting that it was already separated from the cylinder when the damage occurred; the cylinder may have also been damaged when the parts were joined or rejoined (Mahony Citation2019).

As we noted earlier (Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:134), the vessel was likely reconstructed incorrectly in modern times, as the water channel on the side of the beaker currently does not line up with the continuation of the channel on the base, where it should connect up in two places (the widths of these iconographic connections on the base match the openings in the water channel on the sidewall). The outside wall on the upper portion of the vessel (the “cuff,” or upper register) may have been reattached in such a way that a few millimeters of the design on the upper part of the cylinder are obscured, covered over slightly by the cuff. Furthermore, a photograph of the vessel pre-conservation suggests that this upper register (the “cuff”) was once attached in a slightly different manner. In an archival photograph (), a supernatural figure with arthropod characteristics, perhaps a scorpion, at the center top of the image, is located above the architectural enclosure on the cylinder. This is about 2 cm off its current location, which has the upper register oriented so the scorpion is above one of the trees. If this earlier orientation between the cuff and the cylinder is the original and correct one, then the priestess figure would be located to the left from our original drawing, and appear above the architectural structure with a roof crest adjacent to the procession ().

Medallion Beaker (Denver 2)

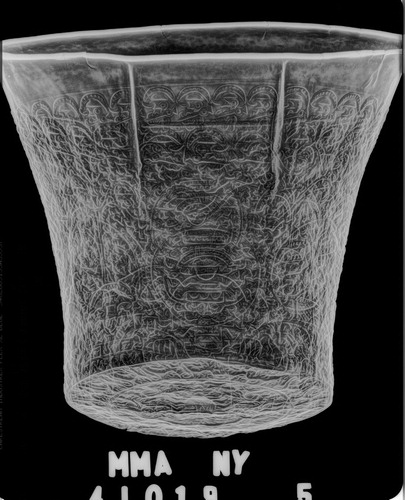

The Medallion Beaker, the taller of the two vessels, is likely from the same workshop as Denver 1 and the Museo de Oro del Perú beaker.Footnote9 With the exception of a c. 2.5 cm band at the top that is unornamented, the entire vessel is profusely decorated with repoussé designs. Denver 2 is more orderly in its composition than Denver 1, with four distinct registers (). The sense of narrative is also less strong in this vessel than in Denver 1, and there is a greater emphasis on repetition, especially as seen in the top three registers.

Unlike the Water Channel Beaker, Denver 2 was constructed from a single piece of hammered silver sheet (). Its alloy composition is approximately 92.4% silver and 5.9% copper, with traces of bismuth (0.2%) and gold (0.1%)Footnote10 (Carò Citation2019; Mahony Citation2019). This alloy composition is quite close to that of Denver 1. It is somewhat different from Lambayeque silver objects excavated by Carlos Wester La Torre and his team at Chornancap, with an alloy of 89% silver, 10% copper, and trace elements of nickel, iron, lead, and bismuth (Brunetti et al. Citation2016; Wester La Torre Citation2016), and also objects stylistically identified as Chimú in the Met’s collection, such as 1987.394.335, which has an alloy of approximately 89% silver and 10.5% copper with traces of elements of lead (0.25%), gold (0.1%), arsenic (0.04%), and nickel (0.03%)Footnote11 (Carò Citation2019; Mahony Citation2019). It is important to bear in mind, however, that these distinctions, particularly between the Denver compositions and those of Chornancap, can be the result of the errors involved in the alloy calculation, and in the possible natural variability of copper and lead contents during alloying (Carò, personal communication, 2020).

Figure 11. X-ray image of the Medallion Beaker (Denver 2). Image prepared by Caitlin Mahony, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The pouring lip/spout on Denver 2 is 6 cm across and 8–10 cm deep. Unlike Denver 1, which has a double wall facilitating a more formal spout, the spout on this vessel is incorporated into the rim itself, almost like folds in cloth (). Other than a c. 2.5 cm band left unworked at the upper part of the vessel, under the lip, the entire vessel, including the base ( and ), is decorated with repoussé designs with additional chasing. The design on the interior base was achieved through repoussé, meaning it was hammered from the exterior, so the raised imagery is oriented to the drinker or the person pouring. This is distinct from Denver 1 where the repoussé imagery on the base faces outward. This feature—the presence of imagery on the interior base—can be noted on other Lambayeque vessels (Mackey Citation2003).

When filled with chicha (a type of maize beer) or other liquid, the two Denver vessels would have been quite heavy—Denver 2 could have held over a liter of liquid—and would have likely required two hands to lift either one of them.Footnote12 In this sense they are distinct from the type of slender beaker excavated at the site of Chornancap in the lower Lambayeque Valley (Wester La Torre Citation2016:213), or one with imagery related to the Denver vessels in the collection of the Museo Oro del Perú (Carcedo Citation2017:fig. 9), which could have been hefted with one hand.

The Medallion Beaker’s imagery was laid out using guide lines or planning marks, thin shallow lines in the metal that define the four registers and larger patterns (; Mahony Citation2019). Such sketch lines have been documented on Moche ceramics (Donnan and McClelland Citation1999:31), and can be seen on other silver vessels and disks with imagery related to the Denver vessels and possibly from the same 1965 find (Carcedo Citation2017; Pillsbury Citation2003). These lines serve as a guide for artists, providing a way to plan the composition across the surface of a vessel.

Figure 15. Detail of guidelines on the surface of the Medallion Beaker. Photograph by Joanne Pillsbury.

The two Denver beakers are closely related from a technological standpoint including methods of ornamentation and alloy composition. Given that few alloy compositional analyses have been conducted on Lambayeque and Chimú silver objects to date, however, such correlations cannot be considered conclusive until a larger data set can be assembled. Although the two vessels were composed in distinct ways (three-part construction v. single sheet), they achieve the same ends as similarly sized, heavily ornamented pouring vessels.

Iconography of the Denver Beakers

In our previous discussion of Denver 1 (Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013), we followed the convention in Moche studies of describing the imagery from the lowest register first and then moving upward, and we continue to do so here.Footnote13 As the iconography of Denver 1 was covered in detail in the above-mentioned article we will only briefly summarize it here.

Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1)

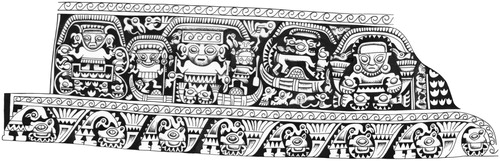

The imagery on the sidewalls of Denver 1 can be divided compositionally into two principal portions, determined by the physically separate components of the cylinder (the lower two-thirds of the rollout drawing) and the upper band or cuff (the upper third) ( and ). A thin border of wave motifs is found at the bottom and top of the vessel’s sidewalls.

The lower two-thirds of the vessel’s walls (the single-walled portion) are dominated by an undulating form we refer to as a water channel, and it may represent a stream or some other body of water. A snakelike creature with the features of a classic Lambayeque-style funerary mask (at the far left of the rollout drawing; Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:120, fig. 6) and other aquatic and anthropomorphic creatures are depicted within the borders of the channel. The water channel connects with the base in two places, where the aquatic and terrestrial imagery continues, including depictions of a Lambayeque-style double-spout-and-bridge vessel, textiles, and a walled garden (; Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:134–135).Footnote14 Other densely populated scenes are located above the water channel on the sidewalls of the vessel (Sections B and C in Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:130–134), including anthropomorphized birds facing an architectural enclosure with a figure inside (to the left of the rollout drawing), and a deer-hunting scene (in the center of the rollout drawing).

One of the most interesting sections of the vessel depicts a procession in a clearly delineated architectural space (on the right in the rollout drawing; also ; Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:13, Section A: Procession and Presentation). Many small profile figures appear to be moving through architectural spaces, perhaps toward a structure with a roof crest (seen at the far upper left of ). One of the chambers adjacent to this structure (upper center of ) contains Spondylus shells. Spondylus, also known as the thorny oyster, was harvested in the warm, tropical waters off the coast of the extreme north coast of Peru and farther north (Carter Citation2011). It was closely linked with deities and supernatural powers, and the Lambayeque and Chimú imported it in vast quantities (Cordy-Collins Citation1990; Pillsbury Citation1996). A priestess, similar to a figure known in Moche iconography (Donnan and Castillo Citation1992; Donnan and McClelland Citation1999:131) and identifiable from her characteristic dress and double plumed headdress, is seen at the upper right of the rollout drawing. To her right, an individual with a cylinder headdress, rendered in small scale, presents a Spondylus shell to her. To the left of the procession in Section A are two large seated female figures who may represent burials (one figure is rotated sideways). Shown within the borders of the Water Channel, they are surrounded by abundant marine creatures and plant life (Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:15).

The uppermost register of Denver 1 is the “cuff.” As noted earlier, the “cuff” was formed separately from the cylinder of the vessel and then attached. The rim of the vessel—where the cylinder and the cuff join—is raised from the cylinder and ornamented with a line of small circular bosses (). The upper register features a band of front-facing supernatural figures (Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:135–137). The six on the left of the rollout drawing () are associated with the sea and are separated from the lower sections by a border of anthropomorphized waves, a motif that first appears in Moche iconography (McClelland Citation1990). The six on the right () are associated with the land and are separated from the lower sections by a band of zoomorphic motifs.

Figure 18. Detail of the rollout drawing of the Water Channel Beaker showing supernaturals associated with the sea. Drawing by Hélène Bernier.

Figure 19. Detail of the rollout drawing of the Water Channel Beaker showing supernatural figures associated with the land. Drawing by Hélène Bernier.

Wester La Torre (Citation2016, Citation2017), who has been conducting excavations at the site of Chornancap, has drawn interesting comparisons between recent discoveries at that site and the imagery on this vessel, particularly the connection between the image of the priestess on Denver 1 and the tomb of a high-status female with similar regalia found at that site and dated to the 12th or 13th century (Wester La Torre Citation2016:395). The prominence of female imagery on Denver 1 and the material from which it was constructed may be linked, as silver was closely associated with women in ancient Peru (Calancha [Citation1639] Citation1974-Citation82: vol. 3, ch. 19, 934; Pillsbury Citation2017:37). Female figures appear on Denver 2 (see below), but they tend to be in subsidiary positions.

Medallion Beaker (Denver 2)

The second Denver vessel—the Medallion Beaker and its iconography—are the focus of this article. The authors presented the Medallion Beaker in 2002 and it has subsequently been discussed in passing by other authors as part of larger studies (Carcedo Citation2017; Narváez Citation2014). Here we present a new rollout drawing of it () and discuss the imagery in detail, along with observations about its relationship to Denver 1. We conclude with a discussion of the possible functions and meanings of these extraordinarily complex works.

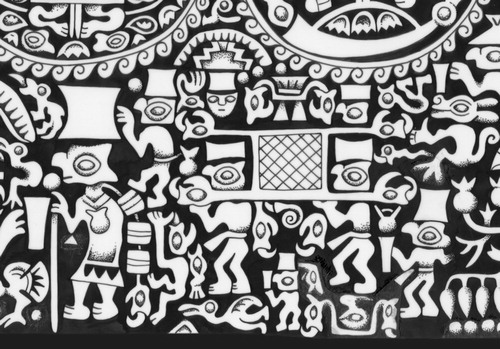

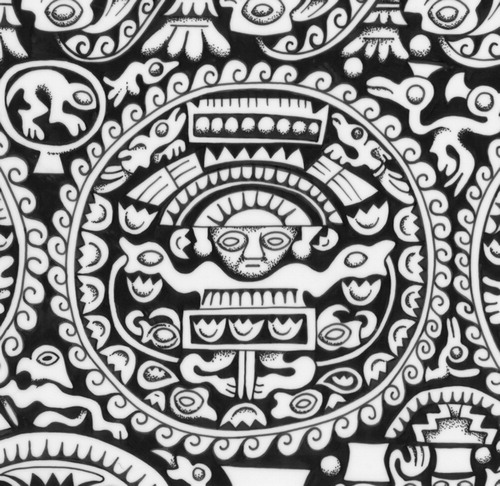

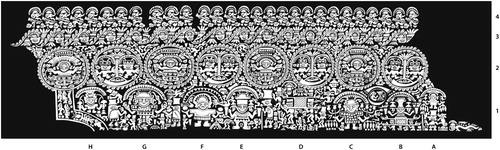

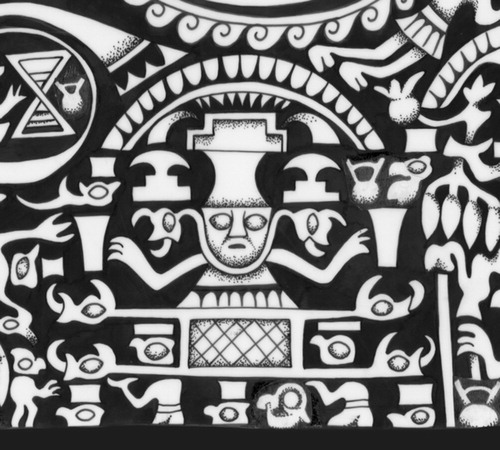

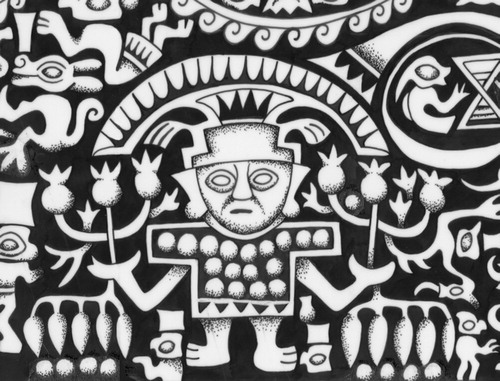

Figure 20. Rollout drawing of the Medallion Beaker (Denver 2). Original drawing prepared by Hélène Bernier; revised by Wilson Santiago.

The composition on the sidewalls of the vessel can be divided into four registers: a first, or lowest register, containing eight major front-facing figures; a second register consisting of eight medallions with scenes of frontal supernatural figures with Spondylus divers alternating with pairs of figures on a crescent-shaped boat; a third register with repeated anthropomorphized waves; and the fourth or top register with zoomorphic figures with crescent headdresses. In a manner analogous to the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1), here on Denver 2 a stream or water channel with fish and crustaceans descends from one of the medallions with divers (on the far left of the rollout drawing, ).

Medallion Beaker, Register 1

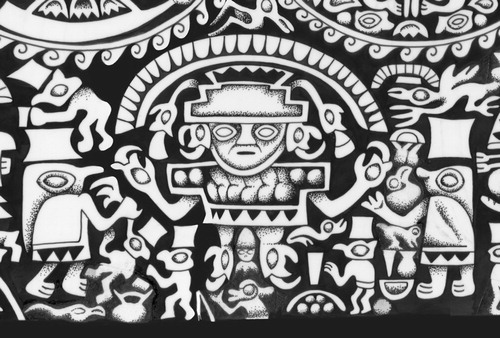

The lowest register (Register 1) contains the most complex, potentially narrative imagery. This band presents eight frontal figures wearing various headdresses, with arms outstretched, grasping a variety of items. These figures have clear connections with figures on the Water Channel Beaker, and the comparison is interesting. On the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1), a band of supernatural figures, some associated with the land, and some with the sea (with anthropomorphic waves below them), form the uppermost register. On the Medallion beaker, sea-associated figures are located in the central medallions and the anthropomorphized wave band above it (Registers 2 and 3), and the land-associated figures are on the lowest register (Register 1) and the top register (Register 4). As in the Water Channel Beaker, the figures in the lowest register on Denver 2 share some similar features, but no two of these eight figures in the lowest register are exactly alike. We have designated these figures A-H, starting on the far right of the rollout drawing ().

Figure A

Beginning on the far right of the rollout drawing, to the left of a tiny upside down three-pronged motif representing a Spondylus valve and snakelike creature is a small, front-facing individual with a cap-crescent headdress surmounted by a larger, uppermost crescent likely representing feathers (). This type of headdress is on one other figure in this lower register (Figure F) and on four supernatural figures in the medallions (Register 2). Figure A holds tubers in either hand. This figure is reminiscent of one of the supernatural “land” figures associated with plants in the Denver 1 beaker. Below him is a figure, shown in profile, wearing a cylinder-shaped headdress, likely associated with Figure B.

Figure B

This figure (), shown seated on a litter, wears a headdress composed of two distinct types of headdresses: a cylindrical one, and a stepped-crescent one. Figure B wears a Lambayeque bicephalic “scarf” (Mackey Citation2001:128; see also Wester La Torre Citation2016:217–219) and has a beaker next to each hand. Litters are closely associated with high-status individuals on the North Coast, and are often depicted in funeral processions or other ceremonies where revered ancestors are venerated.

The litter is shown with a woven seat and horizontal bars terminating in animal heads. This figure is held aloft by two bearers and accompanied by several figures shown in profile, each wearing a cylindrical headdress that tapers at the center and is characteristic of the Lambayeque region (see the Metropolitan Museum of Art accession number 66.196.13 and Shimada Citation1995 for examples in gold sheet). Such headdresses may be indicative of rank or ethnic affiliation. This type is worn by four figures on the Water Channel beaker (Denver 1), and by over twenty figures on this vessel. One of the large profile figures with a cylindrical headdress, to the right of the figure in the litter (Figure B), carries a staff and is flanked by a creature with a serrated back on the right as well as an upside-down head, and has a classic Lambayeque double-spout and bridge bottle in front of him.

A circular form surmounted by an element with a fringe at either end, possibly representing a piece of cloth, located above and to the left of Figure B in the rollout drawing (visible on the upper right in ), is reminiscent of an element in the Denver 1 beaker. A seated figure shown in profile faces an X-shaped loom, which is next to a double-spout-and-bridge vessel ( is a miniature version of such a loom; see also Hamilton Citation2018 for a thoughtful discussion of these). A similar X-shaped loom also appears on the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1), in the upper register, by the side of the priestess. In that instance a prone figure is shown beneath the loom; here the figure is an upright female and active. Similar weavers feature prominently on a gold crown excavated by Carlos Wester La Torre and his team at Chornancap (Citation2016:197–198).

Figure C

To the left of Figure B is a figure that is also found in the upper band of the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1) on the “land” side (). As in Denver 1, the figure wears a shirt with circular elements, perhaps representing ornaments of gold, gilded copper, or some other material, sewn to a cotton backing, with a lower border of repeated triangular forms or zig-zags, perhaps representing bells. As with many of the other frontal figures, the ears are characteristic of the Lambayeque region. The compound headdress is a stepped crescent with featherlike extensions surmounted by a larger crescent, also likely representing feathers. The lower stepped crescent may have been feathered as well. A stepped headdress, for example, reportedly recovered from Chan Chan in the early twentieth century, also features feathers attached to a cloth structure (). Figure C holds a plant, most likely cotton, in either hand and tubers are shown below the hands.

Figure D

This figure better understood as a cluster of images making up a scene of a procession. The front-facing figure here is quite small (, center top), and limited to a head with a headdress composed of two types of headdresses seen elsewhere: a lower cylinder headdress surmounted by a step-crescent one. The smaller scale of this figure may be related to the need to indicate, in great detail, other elements of the procession or his relative status within the procession. Four figures with cylindrical headdresses are shown carrying the litter, and they are surrounded by other figures with cylindrical headdresses, and one with a more triangular headdress, some bearing beakers. This litter is similar to that shown with Figure B, with a woven seat and carrying poles that terminate in zoomorphic heads. In contrast to Figure B, however, the occupant (the head, or Figure D) is shown above and to the left of the litter. A double-spout and bridge vessel is shown behind the litter, and small zoomorphic elements, including a seabird, surround these figures.

Alternatively, the primary figure in this scene could be the tall figure leading the procession, carrying a staff and wearing a prominent cylindrical headdress with a tapered midsection. Shown in profile, this figure wears a longer garment with a lower border of triangular or zig-zag forms. An element on the figure’s chest is like the silver tweezers or pincers in the shape of Spondylus valves in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (; see also Pillsbury et al. Citation2017:cat. 54, p. 162), while a complex element terminating in a zoomorphic head hangs down the figure’s back. Given the extensive documentation of important individuals depicted in litters (Ogburn Citation2008), however, it would seem that the smaller head is meant to represent the key figure in this scene.

Figure 27. Pincers in the shape of a Spondylus shell. Chimú. Huarura Province, Huacho, Hacienda Humaya, Peru. Silver. Dimensions: 4 × 7.1 × 6.9 cm (1 9/16 × 2 13/16 × 2 1/16 in.). Museum purchase, 1948 © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 46-77-30/6158.

Figure E

Left of the complex litter scene on the rollout drawing is a full-size frontal figure, Figure E (). Like Figures B and D, this figure also has a composite headdress (a cylinder headdress below and a stepped-crescent headdress above) and a bicephalic scarf. In contrast to the other frontal figures, Figure E wears a broad collar of the type known from the Moche period and is shown with a shirt or tunic with a zig-zag or serrated lower border. Like Figure B, this figure has a beaker next to either hand, and is flanked by seabirds—including one with its catch in its beak—and other creatures.

Figure F

This figure () wears a cap-crescent headdress similar to Figure A and four of the supernatural figures in the medallions. This headdress consists of a semi-circular cap-shaped base from which the (presumably feathered) crescent extends. Two creatures float above right and left of Figure F’s headdress. The figure’s shirt terminates in a fringed border, and he holds a round object in each hand, often referred to by the Spanish term, “bolas” (Mackey Citation2001:118, fig. 6). A small wide-necked jar is shown below his left arm and below his right is a small figure rendered in profile, wearing a cylinder headdress and holding a beaker. Another figure wearing a cylinder headdress floats above left of Figure F’s headdress, and a single cylinder headdress is to the right. A related figure wearing a similar garment and holding circular objects is seen on the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1) in the top band on the “land” side.

Figure G

This frontal supernatural being wears a large step-crescent headdress and is flanked by two female figures wearing cylindrical headdresses (). Figure G’s appendages terminate in snakelike heads, as do the scarf and two streamers extending from the lower stepped portion of the headdress. The figure’s shirt is decorated with circular forms with a lower border with a zig-zag design, similar to Figure C. Multiple smaller figures with cylindrical headdresses are above and in front of the flanking figures, including one with a beaker and one with a double-spout-and-bridge bottle. Other vessels and creatures fill in the remaining spaces.

Figure H

Figure H holds a crescent-shaped knife (tumi) in either hand (). The figure has characteristic Lambayeque-style ears—pointed rectangles terminating in circular forms representing ear ornaments—and a stepped-crescent headdress. Figures with tumi knives are generally associated with sacrifice.

Medallion Beaker, Register 1—Discussion

As noted above, the Medallion Beaker’s lower register contains the vessel’s most complex imagery, and it is likely that it may have been perceived as presenting a narrative sequence, perhaps a mortuary ritual. Key to the interpretation of this scene is the variation in headdress type, which, along with the tunic design, may have been understood to indicate a figure’s status or ethnicity. Three types of headdresses are shown on the major front-facing supernatural figures in Register 1. These include the cap-crescent headdress worn by Figures A and F; the step-crescent headdress worn by Figures C and G (Figure H wears a variant of this); and the composite cylinder-step-crescent headdress—essentially two headdress types combined—worn by Figures B, D, and E. The headdress type worn by the largest number of figures in this register, however, is simpler: a plain cylinder without a feather crescent. The twenty figures who wear this headdress type are generally shown smaller in scale and in profile—often indicators of lesser status—but they are notably active.

The significance of three figures (B, D, and E) wearing the composite cylinder-step-crescent headdress is unknown, but there are multiple interpretative possibilities, including viewing the three as part of a single narrative. Although this interpretation is admittedly speculative, the three figures may represent the same individual shown in separate stages of a procession or assembly, possibly a funerary ritual. Guaman Poma de Ayala’s early seventeenth century manuscript, for example, includes several depictions of mummies born aloft in litters (Guaman Poma de Ayala Citation1615: 377 [379]).

The composite headdress itself may signal two distinct but simultaneous identities. The cylinder headdress rests atop the head and may indicate an identification with a specific social group—it is the headdress type associated with the largest number of figures, and the most humanlike of the figures in the compositions. Such headdresses also appear on Denver 1, but they are fewer in number. The second part of the composite headdress—the step-crescent—is generally associated with supernatural figures. Does the placement of the step-crescent over the cylinder suggest a transformation of an identity or state of being, perhaps an apotheosis? The location of the beakers near, but not in, the hands of Figures B and E may reinforce the interpretation that the figures are deceased. Deceased individuals in both Lambayeque and Chimú iconography often have objects placed next to them, as one would see in a burial. The living are shown holding objects in their hands, such as the figure holding the tumi knives (Figure H) and the figures holding plants (Figures A and C).

Medallion Beaker, Register 2

The second register from the bottom is made up of eight medallions of slightly differing size and alternating imagery. Medallion layouts are a feature of Moche I-II ceramics (Donnan and McClelland Citation1999:35), an example of the integral part Moche art played in the development of the Lambayeque and later Chimú styles (). Four medallions contain two profile creatures with crescent headdresses grasping a vertical element, perhaps a mast over a crescent-shaped reed boat with three Spondylus shells in the hold (; see also Narváez and Delgado Citation2011:117), and five or six additional valves above the mast, and additional valves in the headdresses and elsewhere.

Figure 32. Bowl with medallion decorations. Silver. Dimensions: H. 2 1/4 × W. 8 × D. 7 3/4 in. (5.7 × 20.3 × 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1969 (Accession Number: 1978.412.220).

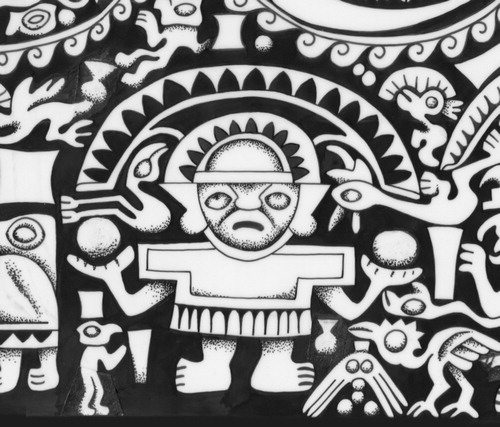

The other four medallions feature the upper body of a frontal supernatural being with the most elaborate headdress of any of the supernatural figures atop a rectangle with three Spondylus valves (). The cap-crescent headdress is surmounted by a larger crescent with wings, another feature that is typical of Lambayeque (Mackey Citation2001:120, fig. 11; Shimada Citation1990:323, fig. 16). This figure’s zoomorphic hands hold ropes attached to divers shown upside down. The divers, in turn, hold a vertical element connecting a Spondylus valve with the rectangle. The supernatural figure in this medallion is similar to one in the upper register of the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1), seen at the far left of the rollout drawing ( and ). Five Spondylus shells line the middle of the inner border of the medallion, flanking the central figure. As noted above, three more are in a rectangular form where the lower part of the supernatural figure’s body would be, perhaps indicating the hold of a boat or raft (cf. Narváez and Delgado Citation2011). Small birds are indicated on either side of the top of the frontal figure’s headdress.

Medallion Beaker, Registers 3 & 4

The upper registers of Denver 2 are simpler than the lower two registers, and each consists of one motif repeated with little variation. Register 3, the second register from the top, is a band of anthropomorphized waves, the eye and beaklike nose of the head, and its crescent headdress, visible under the curve of the wave. This well-known Lambayeque motif is also found in the same relative position (second register from the top) on Denver 1.

The Medallion Beaker’s top register contains a line of largely identical anthropomorphized creatures with beaklike maws but the protruding tongues of snakes. The creatures wear crescent headdresses and carry maces. The stance of the figures is similar to the anthropomorphized birds in Denver 1, although in Denver 1 they carry what appear to be agricultural implements (Mackey and Pillsbury Citation2013:19, ). Beneath the creatures’ hands are tri-pronged elements representing Spondylus valves and profile heads with birdlike beaks.

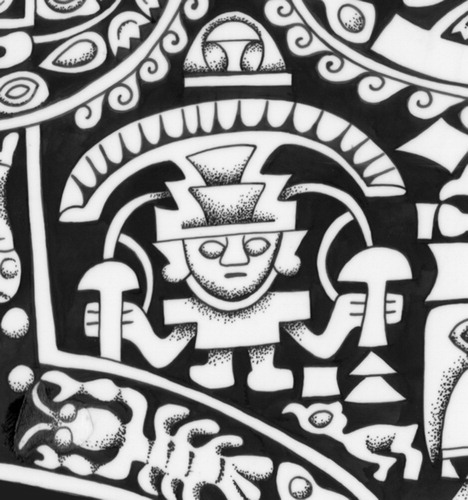

Medallion Beaker, Base

Unlike the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1), the imagery on the sides of the Medallion Beaker (Denver 2) does not connect to the base. Also, as noted above, in contrast to Denver 1, where the repoussé imagery was worked from the inside so the imagery is meant to be viewed on the outside, toward others, here the beaker was worked from the outside so the design is oriented to the server or drinker as the cup was drained.

The base of the Medallion Beaker is organized into two registers, divided by a thin, plain border ( and ). A scorpion, a predatory arachnid, dominates the center. A somewhat similar creature appears in the upper band of Denver 1, but that creature has ten legs. The creature on Denver 2 features the characteristic eight legs, grasping pedipalps, and the narrow, segmented tail and stinger of a scorpion, but the head is anthropomorphized, with ears rendered in classic Lambayeque fashion (pointed rectangular, with a circular lower section referencing ear ornaments) and a large compound step-crescent headdress. The scorpion is encircled by a band of quadrupeds, possibly camelids, linked together by a rope, consuming sprigs, along with smaller elements such as disembodied animal heads. A band of curled-tailed felines and tiny zoomorphic heads encircles the edge of the base. The head of the scorpion is oriented to the spout of the vessel, so if you were drinking from the vessel you would see the stinger of the creature first as the base is revealed.

Concluding Thoughts

The two Denver vessels, although constructed differently, share close correspondences in fundamental technologies, including alloy composition, and iconography. Both feature specific iconographic motifs such as the double-spout-and-bridge vessel that are considered diagnostic of the Lambayeque style. Both vessels also highlight Spondylus shells—in diving scenes, as the focus of a procession, and in the hands of divinities. This focus underscores the profound ritual importance of this bivalve and its prominent role in religious thought on Peru’s North Coast in pre-Columbian times.

Both vessels also show a strong relationship with funerary practices, from the female burials on the Water Channel Beaker (Denver 1), to the narrative scene of the mortuary ritual shown in Register 1 on the Medallion Beaker (Denver 2). Female imagery is more prominent on Denver 1 than on Denver 2, where the primary figures are all male. On both vessels, figures are associated with beakers, or they present beakers, underscoring the importance of such objects in rituals, on a ritual vessel itself. In this sense, the two Denver vessels are very “meta” in their self-reference, guiding or instructing the viewer in the proper context and meaning of such beakers. There is something almost prescriptive in the iconography, a listing of the necessary elements for a proper ritual, including a stream or water channel, a weaver, specific supernatural figures, and the double-spout vessels that occur on both beakers. More than anything else, these two vessels underscore the importance of such objects in ancient Andean ritual practice.

The Denver vessels’ imagery is rendered at an intimate scale: they are works designed to be viewed up close.Footnote15 These are not monumental public works, but delicate, esoteric reminders of practices and beliefs, not likely intended for extensive use in this world but certainly meant to have an enduring efficacy beyond any immediate funerary events as part of a tomb assemblage. Seen in aggregate, the imagery on the Denver vessels may reference ideas about enduring life, ancestors as a source of renewal and regrowth, and a generalized abundance. In the absence of texts contemporary to the vessels it is unlikely that the iconography can be determined with any degree of specificity, but the litters, the boats, and the Spondylus on the vessels may refer to an idea of a funerary procession and an afterlife. Seventeenth-century clerics on the coast of Peru noted that indigenous ideas about an afterlife included a maritime journey (Arriaga Citation1968 [Citation1621]:64; Calancha Citation1974–82 [1639]: Book II, Chapt. XII:379). The strong presence of the marine bivalve Spondylus in both vessels is particularly striking. Called the “daughters of the sea, the mother of all waters” in the colonial period, the thorny oyster was closely linked to ideas of water, fertility, and abundance (Pillsbury Citation1996). The sixteenth-century Huarochirí Manuscript (Citation1991 [Citation1598–Citation1608]:116) tells us that thorny oysters were the food of the gods, sustenance for the divine. Closely linked with deities and supernatural powers, Spondylus shells were often included in high-status burials (Shimada Citation1995; Wester La Torre Citation2016).

The constellation of elements on the two Denver vessels may have referenced ideas about renewal and fertility, and the rituals enacted to secure continued abundance. One of the ironies of the two vessels—whose imagery is so closely bound up with enduring presence—is that they were created from a metal, silver, perhaps thought to be eternal, but actually quite fragile in the saline conditions of burial. The two silver beakers are remarkable, exceedingly rare works that shed light on our understanding of ritual practices and cosmological beliefs in the centuries before the arrival of Europeans in the Andean region of South America.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Victoria Lyall of the Denver Art Museum for her interest in this project and her permission to study the vessels. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, we are indebted to Marco Leona, Scientist in Charge, Department of Scientific Research, and Lisa Pilosi, Conservator in Charge, Department of Objects Conservation, for their support for this project. The study of the vessels was greatly aided by the work of conservators and scientists at the Met, especially Federico Carò and Caitlin Mahony, but also Sara Levin and Ellen Howe. We are also indebted to Sumru Aricanli (American Museum of Natural History) and Emily Kaplan (National Museum of the American Indian) for assistance with the archival research. The initial rollout drawings were created with Hélène Bernier, and revised on the basis of digital studies at the Met. We thank Scott Geffert, Senior Imaging Manager, for his support of this project, and especially Wilson Santiago for his insightful work in developing the new drawing. Additional thanks to Sara Chen, Adela Oppenheim, and Diana Craig Patch, colleagues in Egyptian Art, for their help in the preparation of several of the final images. We are particularly grateful to Cathy Costin, Edward Harwood, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper. Finally, we wish to thank our colleagues Paloma Carcedo, Lisa DeLeonardis, Christopher Donnan, Andrew Hamilton, Heidi King, Jerry Moore, Margaret MacLean, Hillary Olcott, Dan Rifkin, Lisa Trever, and Carlos Wester La Torre for their help and suggestions on this study. All errors remain our own.

Notes

1 On the subject of drinking vessels, see, among others, Cummins (Citation2002) and Vetter Parodi (Citation2011).

2 In addition to the beaker in the Museo Oro del Perú (M-1947), highly similar to Denver 2 (1969.303), other works, such as a pedestal bowl in the Museo Larco, Lima (ML100755) bear related iconography. See Carcedo (Citation2017), King (Citation2000), and Narváez (Citation2014) for further discussions of these works. As noted in our 2013 article, there are also related textiles now in the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin (see Schmidt Citation1929, 488–96).

3 There are no reliable data on the precise context of the find. According to Alan Lapiner (Citation1976, 447, note 600), they were part of a cache containing dozens of effigy vessels, cups, and worked and unworked disks found on the grounds of Hacienda Mocollope in the Chicama Valley. A letter from Alan Sawyer to Junius Bird from April 16, 1966, however, suggests that the silver objects came from Chan Chan, during the reconstruction of the Nik An (Tschudi) palace (The American Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Junius Bird Archive).

4 All works in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art cited here are available online: www.metmuseum.org/art.

5 Normalized alloy compositions expressed in weight percentages, calculated by wavelength dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) in a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Carò Citation2019).

6 The use of the term “Lambayeque” here refers to the broader post-Moche tradition in the Lambayeque region and neighboring valleys, rather than the more specific Sicán tradition (Shimada Citation2014). Sicán metal beakers are iconographically and technologically distinct from the two Denver silver vessels. Sicán beakers were produced in great quantities, often shaped by raising the basic form from a single piece of hammered metal sheet with the use of a wooden form or template. Generally simpler compositions, many possess the shape of the torso and head of a being called the Sicán Deity. Gold and copper appear to have been preferred over silver at Batán Grande: one of the richest unlooted tombs contained some 1.2 tons of grave goods, of which more than two-thirds were made of copper, gold, or copper-gold alloys (Shimada Citation2000, 49–64, 97–110, 56).

7 Here we use the term “supernatural” to indicate figures with appendages and other characteristics denoting a non-human quality. In this particular instance, the “priestess” has zoomorphic hands and feet, and is distinct from depictions of similar priestesses in Moche art, or women buried with similar regalia excavated by Donnan and Castillo (Citation1992).

8 “Chimú Silver Notebook,” Junius Bird Archive, Department of Anthropology, The American Museum of Natural History.

9 See Carcedo de Mufarech (Citation2017) for a discussion of the Museo Oro del Perú beaker (M-1947). The upper two registers, for example, are nearly identical to Denver 2. See also Göransson and Carcedo de Mufarech (Citation2011).

10 Normalized alloy compositions expressed in weight percentages, calculated by wavelength dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) in a scanning electron microscope (SEM) as for Denver 1 (Carò Citation2019).

11 This average composition was calculated by non-invasive, surface XRF analysis.

12 See Torres della Pina and Mujica (Citation1999: fig I-3) for a silver figure lifting a vessel with two hands.

13 See Castillo (Citation1989) and Donnan and McClelland (Citation1999, 182) for a discussion of narrative and directionality in Moche fineline painting.

14 As we noted in 2013 and above, the base and the cylinder were reattached slightly incorrectly in modern times. The current registration between the two is off by approximately 2 cms.

15 See Costin (Citation2019) on vessels, scale, and esoteric knowledge.

References Cited

- Aimi, Antonio, Krzysztof Makowski, and Emilia Perassi (editor) 2017 Lambayeque: Nuevos horizontes de la arqueología peruana. Ledizioni, Milan.

- Arriaga, Pablo José de 1968 [1621] The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru. Translated and edited by L. Clark Keating. University of Kentucky Press, Lexington.

- Brunetti, Antonio, Julio Fabian, Carlos Wester La Torre, and Nick Schiavon 2016 A Combined XRF/Monte Carlo Simulation Study of Multilayered Peruvian Metal Artifacts from the Tomb of the Priestess of Chornancap. Applied Physics A 122, 571 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-016-0096-6.

- Calancha, Antonio de la 1974–82 [1639] Crónica moralizada. 6 vols. Edited by Ignacio Prado Pastor. Reprint, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima.

- Carcedo de Mufarech, Paloma 2017 Reflexiones sobre la producción Sicán y Chimú de vasos tipo kero y discos en plata: Su iconografía y su relación con las miniaturas chimú. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Etudes Andines 46(1):37–75. doi: 10.4000/bifea.8428

- Carcedo Muro de Mufarech, Paloma, and Izumi Shimada 1985 Behind the Golden Mask: Sicán Gold Artifacts from Batán Grande, Peru. In The Art of Precolumbian Gold: The Jan Mitchell Collection, edited by Julie Jones, pp. 60–75. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Carò, Federico 2019 Denver Art Museum Precolumbian Vessels Silver Alloy Compositions. Report on file, Department of Scientific Research, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Carter, Benjamin 2011 Spondylus in South American Prehistory. In Spondylus in Prehistory: New Data and Approaches, edited by Fotis Ifantidis and Marianna Nikolaidu, pp. 63–89. BAR International Series, vol. 2216. Archaeopress, Oxford.

- Castillo, Luis Jaime 1989 Personajes míticos, escenas y narraciones en la iconografía mochica. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Fondo Editorial, Lima, Peru.

- Cordy-Collins, Alana 1990 Fonga Sigde, Shell Purveyor to the Chimu Kings. In The Northern Dynasties: Kingship and Statecraft in Chimor. A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 12th and 13th October 1985, edited by Michael E. Moseley and Alana Cordy-Collins, pp. 393–417. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

- Costin, Cathy 2019 Revisiting North Coast Formative Period Ceramic Iconography: the Case for Foundational Ritual Power. Institute for Andean Studies Annual Meeting. Berkeley, CA.

- Cummins, Thomas B. F. 2002 Toasts with the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

- Donnan, Christopher B., and Luis Jaime Castillo 1992 Finding the Tomb of a Moche Priestess. Archaeology 45(6):38–42.

- Donnan, Christopher B. and Donna McClelland 1999 Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, Los Angeles.

- Fernández Alvarado, Julio César, and Carlos Eduardo Wester La Torre (editors) 2014 Cultura Lambayeque en el contexto de la costa norte del Perú: Actas del primer y segundo coloquio. Colección Cultura Lambayeque 1. EMDECOSEGE S.A., Chiclayo, Peru.

- Göransson, Kristian, and Paloma Carcedo de Mufarech (editors) 2011 Inca: Gold Treasures in the Skeppsholmen Caverns. Varaldskulturmuseerna, Stockholm.

- Guaman Poma de Ayala, Felipe 1615 Nueva crónica y buen gobierno. http://www5.kb.dk/permalink/2006/poma/info/en/, accessed March 23, 2020.

- Hamilton, Andrew J. 2018 Scale and the Incas. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.

- King, Heidi 2000 Rain of the Moon: Silver in Ancient Peru. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New York.

- Kosok, Paul 1965 Life, Land, and Water in Ancient Peru: An Account of the Discovery, Exploration, and Mapping of Ancient Pyramids, Canals, Roads, Towns, Walls, and Fortresses of Coastal Peru with Observations of Various Aspects of Peruvian Life, Both Ancient and Modern. Long Island University Press, New York.

- Lapiner, Alan C. 1976 Pre-Columbian Art of South America. H.N. Abrams, New York.

- Mackey, Carol J. 2001 Los dioses que perdieron los colmillos. In Los dioses del antiguo Perú. Tomo 2, edited by Krzysztof Makowski, pp. 110–157. Banco de Credito del Perú, Lima.

- Mackey, Carol J. 2003 Field Notes from the 2003 season at Farfán. Unpublished notebook in possession of the author.

- Mackey, Carol J. 2011 The Persistence of Lambayeque Ethnic Identity: The Perspective from the Jequetepeque Valley, Peru. In From State to Empire in the Prehistoric Jequetepeque Valley, Peru, edited by Coleen M. Zori and Ilana Johnson, pp. 149–168. BAR International Series vol. 2310, Archaeopress, Oxford.

- Mackey, Carol J., and Joanne Pillsbury 2002 Sacred Silver Keros from the North Coast of Peru. Paper delivered at the New World Art Symposium, Denver Art Museum.

- Mackey, Carol J., and Joanne Pillsbury 2013 Cosmology and Ritual on a Lambayeque Beaker. In Art of the Pre-Columbian World: Honoring the Contributions of Frederick R. Mayer, edited by Margaret Young-Sánchez, pp. 115–141. Denver Art Museum, Denver.

- Mahony, Caitlin 2019 Technical Examination, DAM 1969.302, .303. Report on file, Department of Objects Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- McClelland, Donna 1990 A Maritime Passage from Moche to Chimu. In The Northern Dynasties: Kingship and Statecraft in Chimor, edited by Michael E. Moseley and Alana Cordy-Collins, pp. 75–106. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

- Merkel, John, and María Inés Velarde 2000 Naipes, Pre-Hispanic Axe Money Currency of Peru. Minerva 11(1):52–55.

- Narváez, Alfredo 2014 Dioses de Lambayeque: Estudio introductorio de la mitología tardía de la costa norte del Perú. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, Unidad Ejecutora 005/Museo de Sitio Túcume, Lambayeque, Peru.

- Narváez, Alfredo, and Bernarda Delgado (editors) 2011 Huaca las Balsas de Túcume: Arte mural. Museo de Sitio Túcume, Lima, Peru.

- Ogburn, Dennis 2008 Dynamic Display, Propaganda, and the Reinforcement of Provincial Power in the Inca Empire. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 14:225–239. doi: 10.1525/ap3a.2004.14.225

- Pillsbury, Joanne 1996 The Thorny Oyster and the Origins of Empire: Implications of Recently Uncovered Spondylus Imagery from Chan Chan, Peru. Latin American Antiquity 7(4):313–340. doi: 10.2307/972262

- Pillsbury, Joanne 2003 Luxury Arts and the Lords of Chimor. In Latin American Collections: Essays in Honor of Ted J. J. Leyenaar, edited by Dorus Kop Jansen and Edward de Bock, pp. 67–81. Ed. Tetl, Leiden.

- Pillsbury, Joanne 2017 Imperial Radiance: Luxury Arts of the Incas and their Predecessors. In Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim Richter, pp. 33–43. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

- Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter (editors) 2017 Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

- Ramírez, Susan E. 1996 The World Upside Down: Cross-Cultural Contact and Conflict in Sixteenth-Century Peru. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- Salomon, Frank, and George Urioste (editors and translators) 1991 [1598–1608] The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- Schmidt, Max 1929 Kunst und Kultur von Peru. Propyläen, Berlin.

- Shimada, Izumi 1990 Cultural Continuities and Discontinuities on the Northern North Coast of Peru, Middle-Late Horizons. In The Northern Dynasties: Kingship and Statecraft in Chimor, edited by Michael E. Moseley and Alana Cordy-Collins, pp. 297–392. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, Washington, DC.

- Shimada, Izumi 1995 Cultura Sicán: Dios, riqueza y poder en la Costa Norte del Perú. Fundación del Banco Continental para el Fomento de la Educación y la Cultura, Edubanco, Lima.

- Shimada, Izumi 2000 The Late Prehispanic Coastal States. In The Inca World, edited by Laura L. Minelli, pp. 49–110. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- Shimada, Izumi (editor) 2014 Cultura Sicán: Esplendor preincaico de la Costa Norte. Translated by Gabriela Cervantes. Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú, Lima.

- Torres della Pina, José, and Victoria Mujica (editors) 1999 Tradición y sentimiento en la platería peruana. Obra Social y Cultural CajaSur, Córdoba, Spain.

- Vetter Parodi, Luisa María 2011 Drink, Music, and Libation in Pre-Columbian Rituals: Drinking Vessels as Guiding Elements. In Inca: Gold Treasures in the Skeppsholmen Caverns, edited by Paloma Carcedo and Kristian Göransson, pp. 172–195. Varaldskulturmuseerna, Stockholm.

- Wester La Torre, Carlos 2016 Chornancap: Palacio de una gobernante y sacerdotisa de la cultura Lambayeque. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, Chiclayo.

- Wester La Torre, Carlos 2017 Chornancap. In Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim Richter, p. 36. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

![Figure 25. Feathered headdress, reportedly recovered from Chan Chan in the early 20th century, National Museum of the American Indian, no. 157355.000 [15/7355]). Photograph courtesy of Heidi King.](/cms/asset/c61e5425-5ee3-4974-8c57-9f244fa8497f/ynaw_a_1795413_f0025_c.jpg)