ABSTRACT

Community resilience can be quantified using available data to inform policy decisions. Identifying vulnerable or deprived communities in New Zealand is straightforward because social, cultural and economic indicators are correlated. However, that is just the first step. Resilience is also a matter of perspective, which means engaging with people in communities affected by policy decisions. When resilience is viewed as multi-dimensional, success in the formal and informal economies is linked to social resilience. However, social resilience cannot flourish in the absence of other resources.

Introduction

Resilience is a term that sometimes seems hopelessly vague. After 15 years of research on resilient rural communities (Brown, Kaye-Blake, & Payne, Citation2019), I have some observations about resilience and its usefulness for policy. This short article makes three points about resilience and then draws some lessons for policy. The first point is that resilience can be operationalised, that is, it can be turned into a meaningful metric. The second point is that resilience is also a matter of perspective, so that any single metric is incomplete. Finally, resilience has social as well as economic dimensions, and economists should be wary of focusing only on transactions and markets. These observations lead to policy recommendations on becoming informed about resilience and taking it into account for policy decisions, especially for place-based policy (Beer, McKenzie, Blazek, Sotarauta, & Ayres, Citation2020).

The research that underpins this article involved many researchers working in two large science programmes (Brown et al., Citation2019; Wedderburn et al., Citation2011). The research drew on other work, especially rural resilience research in Australia and the United Kingdom. In particular, when developing a framework for resilience and indicators for the framework, we drew heavily on work by Geoff Wilson (Kaye-Blake, Stirrat, Smith, & Fielke, Citation2019; Wilson, Citation2010). Rural communities in these countries are facing the same issues as communities in New Zealand. They have developed their own approaches to developing community resilience, for example, the Transition Towns initiative in the UK. Our work was different from that overseas research in three ways. First, we took the concept of resilience as a quantifiable property seriously and attempted to measure it. Our results are discussed below. Second, we incorporated a focus on institutional resilience, which is sometimes considered (Oncescu, Citation2014) but often not. Third, Māori issues are important in Aotearoa New Zealand, which affects rural community research. In practice, ‘cultural resilience’ can become synonymous with ‘Māori’. The benefit is that this visibility can prompt discussions about Māori issues, but the drawback is that those issues may then be set off to the side. Nevertheless, it is a unique aspect of community research in this country.

Quantifying and describing resilience

Our work on rural community resilience has been interdisciplinary and has taken a multi-methods approach (Brown et al., Citation2019). One method was statistical analysis of official data, mainly Census data from Statistics NZ from the 2013 and 2018 Censuses. We conducted a principal component analysis of 14 variables at the community or Statistical Area 2 (SA2) level, which tend to contain a few thousand people. The variables were chosen based on the literature on community resilience (Kaye-Blake et al., Citation2019; Payne, Kaye-Blake, Kelsey, Brown, & Niles, Citation2021), with variables for most of the dimensions in a resilience framework we developed. Included were social, cultural, economic and institutional dimensions, and excluded were the environmental dimension (for data availability reasons) and the external dimension (for definitional reasons). The first principal component accounted for 55 percent of the variation in the dataset, and we used it to create a linear index of community resilience and scored and ranked over 300 rural New Zealand locations. Weightings derived from the 2018 Census are provided in Table .

Table 1. PCA weightings from 2018 Census variables for resilience index.

There are three main things to report about the resilience index. First, it was able to differentiate among communities: some scored highly and others did not. Second, we compared it with the New Zealand Deprivation Index (Salmond & Crampton, Citation2012) and found a 94.6 percent correlation. These two findings suggest that the index tells us something, and that something is similar to measures of deprivation. The third finding was that the variables that made up the index were highly correlated. Across income, education, smoking rates, rates of Māori identification, voting participation and more, each individual variable had much the same thing to say as the composite index. These statistical findings suggest that resilience is related to inequality. Communities that score lower on the resilience index have lower income, lower levels of educational achievement and lower levels of employment.

Our research used other methods, too, especially community-based workshops. We found that the official statistics aligned poorly with how community members felt about their own communities (Payne et al., Citation2021), and indeed with observable resilience behaviours. The workshops took participants through a process of reflecting on a the strengths and challenges of a community, and then asked them to rate its resilience (Brown et al., Citation2019). We found that the view from the inside was different from the view from the outside. One aspect of that difference was that community members, especially those people who participate in workshops, are aware of the resources and potentials in their communities. For example, we held a recent workshop in a town that statistically is in the bottom quintile of rural community resilience. We found, however, that the community has a strong network of people who do things for the town: they come up with ideas, plan them out, obtain funding from different sources, and make them happen. They still have empty shopfronts on the main street, and the main historical industry has left town, but they also have their own capabilities and agency. These workshop findings temper somewhat the connection between resilience and inequality. If resilience is about the ability to adapt to changing circumstances (Brown et al., Citation2019), then it is not determined solely by income, education and other resources that are not equally allocated in New Zealand.

Across the research, we found that social resilience is important for communities, bearing in mind the general patterns of correlation across all dimensions. At the community level, this includes education levels and participation in volunteering. At the personal level, it includes knowing people and having personal networks to rely on. We found that these networks allow community members to recover from adverse events, such as floods. In separate research, we also found that businesses in the primary sector relied on social relationships and networks to deal with the disruptions of COVID-19 in 2020 (Snow et al., Citation2021).

We can put an economic lens on social resilience, although this is not likely the way that community members themselves might view their social relationships. These relationships provide sources of non-market transactions in an informal economy that boosts consumption without increasing monetary income. For example, bartering childcare services for food from the garden, or volunteering at the school or marae increases the goods and services consumed by the community. These networks also reduce transactions costs, substituting a repeated-game trust relationship for a negotiated contract. Especially in a situation characterised by uncertainty or multiple low-value transactions, low transactions costs can create welfare gains. Social relationships can also be a risk-mitigation strategy. Adverse events tend to have uneven impacts: flood damage, earthquake damage, and even machinery that breaks at inopportune times all are unevenly distributed. A large and strong social network can share resources between the more affected and less affected, effectively spreading risk.

Policy implications

These findings have implications for policy. The first implication is not to overcomplicate things: targeting resources does not have to be difficult. Identifying a vulnerable or deprived community is as simple as looking at smoking rates or income. The fact that indicators are highly correlated, and that this interdisciplinary, multi-dimensional analysis aligns with earlier research, suggests that more work on identifying whom to target has diminishing returns. This simplicity also means that it is easy for policy-makers to gain an initial sense of a place – a community or district – by looking at official statistics. The website for the 2018 Census results makes the data easy to access at several geographic scales. For any place, it is easy to find economic and demographic statistics that provide some idea of community resilience.

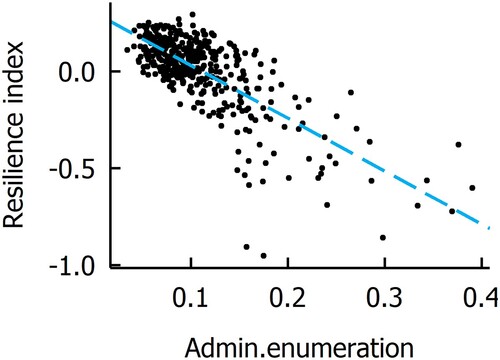

Once these communities have been identified, they can be prioritised for scarce public resources. Here is an example of using resilience indicators to allocate scarce funding. The 2018 Census took a digital-first approach and allocated fewer resources to in-person and mail-in enumeration. A possible policy question is, ‘how should we allocate the enumeration resources?’ In the event, the 2018 Census needed to be supplemented by administrative data, a process called administrative enumeration. Statistics NZ reported the percentage of data that needed to be supplemented for each SA2. Figure provides a scatterplot, with a trend line, of the resilience index with the percentage of data obtained by administrative enumeration. It shows that administrative enumeration is correlated with the resilience index, which suggests that the index could have been used beforehand to identify communities where additional enumeration resources might have produced higher response rates.

Another implication for policy is that we outsiders – researchers and policy-makers – should be wary of assuming we know more than we do about a place. The trend towards place-based policy is an improvement on spatially blind policy because it recognises the variation across locations and communities (Beer et al., Citation2020). At the same time, effective engagement with communities is important for understanding how they function (Brown et al., Citation2019). We have often advised government agencies that their people need to sit down for a cuppa with the communities for which they are responsible. While that approach may seem resource-intensive, it can lead to better allocation of resources and outcomes. Furthermore, our research has shown the value of social networks for dealing with the unexpected. The unexpected or unusual is by definition not the thing for which policies and procedures are fully developed. It requires some creativity and flexibility to achieve a good-enough solution in the moment. Where policy manuals can provide guidance for the ordinary times, social networks can provide structure during unexpected times and help define what is appropriate and achievable. The role of networks and personal relationships was specifically mentioned in interviews about the government’s handling of COVID-19 (Snow et al., Citation2021). People in the agricultural sector were able to deal directly and openly with policy-makers with a sense of a shared problem, and together they figured out how to deal with the pandemic and keep that essential sector operating. Their cooperation reduced economic damages from the pandemic.

It is also important not to make social resilience bear too much weight. I have seen a temptation to treat ‘social capital’ as a cheap and easy way to fix problems in communities. The thinking is that a small amount of funding for a few community courses or events will make communities resilient. This is a misreading of our findings in three ways. First, the correlations across dimensions and the interactions among social, cultural, economic and institutional resilience suggest that multiple dimensions need to be involved in improving community resilience. For a social network to reallocate resources through an informal economy or through cooperation after a disaster, those economic resources have to be there in the community. In addition, institutions like schools and rugby clubs provide stability for communities and social networks (Oncescu, Citation2014). Closing down a community’s government offices, major employer or school and assuming that social resilience will fill the void is asking that resilience dimension to do too much work.

The other two misreadings are aspects of social resilience that we have highlighted less in our work. One is the amount of investment involved in producing social resilience. In our workshops and discussions with community members, it is clear that they have invested considerable time and energy in their social networks and relationships. This observation is a commonplace in feminist economics (Waring, Citation1988): building and maintaining relationships requires time, emotional energy and cognition. These are all resources, and community members have invested their scarce resources in building the relationships that keep communities resilient. Among Pākehā, some people will have known each other for decades or all their lives. Their parents or grandparents might have known each other; the family ties with cousins and marriages can be extensive. Among Māori, whānau, hapū and marae communities have extensive and remembered interpersonal networks, helping these communities survive in spite of the impacts of colonisation (Smith, Citation2012). Policy-makers should remember that creating and maintaining social resilience requires resources. The second aspect to consider is highlighted in the community-led development literature (Rhodes, Kaye-Blake, & Bewsell, Citation2016). Rural communities are small, and often there is only a handful of people taking on many roles. These keystone people can become overburdened and burn out. Policy-makers should not expect them to do more and more for their communities without support and resources.

These observations raise the possibility of additional research on social resilience. The information gaps are around how people allocate their time outside of work hours, and then how they are connected to each. Detailed research could focus on both individuals and groups of people using time-use studies and social network analysis. With that information, it may be possible to develop an analysis of how people invest in and build social networks and resilience. Another approach could be retrospective: after an event like a flood or pandemic, it may be possible through interviews to establish what a network looked like, how it was produced and how it was used in the event. In particular, it could be informative to connect economic decisions to those social networks: which work was done first, who accessed which resources, or whose livestock was accepted by the meat works? To add a personal anecdote: after the major Christchurch earthquake in February 2011, we had to make our house weathertight. We contacted a builder we knew because our children had gone to kindy together, and he did the work right away. Our ability to find and employ a builder in a crisis depended on my wife’s social network and prior volunteering.

Additional research could also help deepen policy-makers’ understanding of resilience. In particular, resilience is often discussed in the context of sudden events, such as floods and earthquakes. Resilience is seen as the ability to bounce back from an adverse event. While this is true, it misses the longer-term nature of resilience. First, the resources required to be resilient are built up over time. Whether those resources are social connections, money, equipment, storage space, the manaakitanga shown in the Kaikōura earthquakes, alternative sources of drinking water, or any other resources that help people get through, they exist in that moment because they were created and maintained over time. People and communities are in that sense always preparing for the next shock. Second, communities are also responding to slow change and seeking to bounce forward and bounce back (Brown et al., Citation2019). Bouncing back is about maintaining identity as society, the economy, culture, institutions and the environment change. Bouncing forward is about adapting to those changes in useful, positive and constructive ways. Communities know that the world will not stay the same forever. What do they try to hold on to, and how can they make changes that improve their lives? These are the questions that face rural communities over issues like depopulation, an ageing population, climate change, land-use change, and access to healthcare and transportation. These issues play out over a longer timeframe but are just as disruptive as a flood.

Conclusion

Our research suggests that resilience is a useful concept for policy, but it requires a shift in mindset to have the largest impact. Resilience can be measured, at least to some extent, and measuring it can provide policy-makers with information about affected places and communities. Thus, the first step to bringing resilience into policy is simply to see what the numbers say. The second step is harder, and it is to engage directly with people in communities to hear what they have to say. Their perspectives may be different from the direction of policy, conventional wisdom or the official picture, but it is part of place-based policy (Beer et al., Citation2020). The third step is equally difficult, and it is to approach communities holistically. A ‘whole of government’ approach would be useful: it would try to understand how social policies and economic policies and environmental policies combine to affect people and communities. However, it is also easy for government agencies to focus on their particular responsibilities rather than inform or collaborate across agencies. Although we recognise that some of this is difficult, we hope that our research can do its little bit to make it easier to lift community resilience.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this short note relies has involved a large number of colleagues and community contributors, whom I gratefully acknowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beer, A., McKenzie, F., Blazek, J., Sotarauta, M., & Ayres, S. (2020). Every place matters: Towards effective place-based policy. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Brown, M., Kaye-Blake, B., & Payne, P. (Eds.). (2019). Heartland strong: How rural New Zealand can change and thrive. Palmerston North: Massey University Press.

- Kaye-Blake, W., Stirrat, K., Smith, M., & Fielke, S. J. (2019). Testing indicators of resilience for rural communities. Rural Society, 28(2), 161–179.

- Oncescu, J. (2014). Creating constraints to community resiliency: The event of a rural school’s closure. Online Journal of Rural Research & Policy, 9(2).

- Payne, P. R., Kaye-Blake, W. H., Kelsey, A., Brown, M., & Niles, M. T. (2021). Measuring rural community resilience: Case studies in New Zealand and Vermont, USA. Ecology and Society, 26(1), art2.

- Rhodes, H., Kaye-Blake, W., & Bewsell, D. (2016). Experts and local people in community-led development (p. 43). Palmerston North: AgResearch.

- Salmond, C. E., & Crampton, P. (2012). Development of New Zealand’s Deprivation Index (NZDep) and its uptake as a national policy tool. Canadian Journal of Public Health / Revue Canadienne de Santé Publique, 103(Supplement 2), S7–S11.

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Dunedin: Otago University Press.

- Snow, V., Rodriguez, D., Dynes, R., Kaye-Blake, W., Mallawaarachchi, T., Zydenbos, S., … Stevens, D. (2021). Resilience achieved via multiple compensating subsystems: The immediate impacts of COVID-19 control measures on the agri-food systems of Australia and New Zealand. Agricultural Systems, 187, 103025.

- Waring, M. (1988). Counting for nothing: What men value & what women are worth. Wellington: Allen & Unwin, Port Nicholson Press.

- Wedderburn, M. E., Kingi, T. T., Mackay, A. D., Brown, M., De Oca, O. M., Maani, K., … Kaye-Blake, B. (2011). Exploring rural futures together. Proceedings of the New Zealand Grassland Association, 73, 69–74.

- Wilson, G. (2010). Multifunctional ‘quality’ and rural community resilience. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35(3), 364–381.