ABSTRACT

The need for agriculture to contribute to economic development in the Pacific is greatest in Melanesia, given rapid population growth and limited emigration options compared with those available to the Polynesian countries. The non-agricultural sector in Melanesia has not grown fast enough to enable rapid labour transfer out of agriculture. With high labour costs and remoteness from world markets the main internationally competitive export industries exploit non-renewable resources or use unsustainably high extraction rates for renewable resources such as forests. These activities fund imports and government revenue but generate little employment. Given this limited structural transformation, the major role of agriculture is in providing food and livelihoods for most households. Policy interventions are not always helpful because of confusion between food security and self-sufficiency and due to data weaknesses. Whether indigenous farming systems can continue to adapt to rising food demand fuelled by rapid population growth remains an open question.

Introduction

Economists who helped shape our understanding of the role of agriculture in development were familiar with island economies. The first Nobel Prize-winning development economist, Sir Arthur Lewis, was born and raised in the Caribbean. Balanced growth in a Lewis-type model occurs if rising agricultural sector productivity allows some surpluses to be invested in non-agricultural sectors to create employment opportunities for workers released from their rural activities while also raising rural incomes to create demand for the non-agricultural outputs. Perhaps the best real world example of this balanced growth was another island economy, Taiwan (Park & Johnston, Citation1995).

Yet development has not taken this path in the Pacific island economies. This note discusses how agriculture’s role in economic development in the Pacific differs from the models, and considers some policy implications. The focus is on Melanesia, notwithstanding links (and responsibilities) New Zealand has with Polynesia. While Polynesia’s working-age population is forecast as an unchanged 0.4 million in 2030 (UN medium variant forecasts), Melanesia’s rises from 6 million in 2015 to 8.2 million in 2030. This growth is especially in Papua New Guinea (PNG), whose working-age (total) population is expected to be 6.6 (10.5) million by 2030. Not only is there greater need for development in Melanesia, there is less opportunity for emigration than from Polynesia if the situation at home becomes untenable.Footnote1

Limited structural transformation

At least two factors account for failure of the non-agricultural sector to expand sufficiently to enable rapid labour transfer out of agriculture. First, the Pacific is far more remote than the Caribbean. Gibson (Citation2007) used a matrix of great-circle distances between 219 countries, weighted by GDP, and found the average Melanesian country was 207th most remote, while the average Caribbean country was only 100th most remote. Further, an economic-distance measure based on transport costs found that remoteness of the Pacific countries was even greater. In addition to being distant from locations of concentrated economic activity, high labour costs have limited the chance for competitive industries to develop. For example, in the lead-up to independence in 1975, the urban minimum wage in PNG was raised sharply by the outgoing Australian administration, going from one-eighth of the Australian minimum to one-third (Howes, Mambon, & Samof, Citation2022) and further rising to be equivalent to almost one-half the Australian minimum wage during the ‘hard Kina’ policy of the 1980s.

With this high cost structure and remoteness, internationally viable export industries rely on exploiting oil and gas fields and mineral resources. While these provide government revenue and fund imports, few jobs are generated and much activity is diverted into rent-seeking, nationally in terms of political focus and locally because most land is in customary (tribal) ownership so royalty payments to landowner groups generate disputed claims. A development model that relies on depleting natural capital also applies to deep-sea fisheries and forests – resources that are, in principle, renewable – that are being harvested in unsustainable ways more akin to mining. For example, log exports provide about half the foreign exchange and one-fifth of government revenue for the Solomon Islands, and these logs are almost all from non-plantation sources (Gibson, Citation2018).Footnote2

Another feature of the Pacific is also shown by Solomon Islands logging. Prior to 2001 log exports were about 50% above sustainable yield with no trend increase. Yet since then export volumes grew over 11% per annum, to seven times sustainable yield. The driving force for this increase is exports to China, whose market share was 13% in 2001 but 95% by 2014; effectively, as other countries withdrew from the tropical logs trade PNG and the Solomon Islands expanded exports to became the top two suppliers to China (Gibson, Citation2018). The quest for resources exacerbates the effects of diplomatic competition in the region – one vote per country in international bodies makes the Pacific an attractive place for influence-seeking, as switches in recognising Taiwan show – and so it is not surprising that some of the highest aid inflows per capita are found in the region. The combined effects of aid inflows and resource rents contribute to overvalued real exchange rates that hamper development of more labour intensive export industries, including of processed agricultural products.

A key policy response from Australia and New Zealand to mitigate effects of low economic density and remoteness in the Pacific islands is to let workers from selected countries temporarily migrate to access their higher-paying labour markets, particularly for work in sectors like horticulture that seasonally suffer labour shortages (Gibson & Bailey, Citation2021).Footnote3 These schemes were badly disrupted by the closed borders response to COVID-19 but a recent estimate is that about 35,000 seasonal workers from the Pacific are in Australia and New Zealand as of mid-2022, with one-third from Vanuatu and then Samoa and Tonga as the next most important suppliers (Howes, Curtain, & Sharman, Citation2022). Polynesian countries had existing migration linkages but Vanuatu’s rise as a labour supplier is policy-driven, with little diaspora when these programs began 15 years ago. Impacts of emigration – both seasonally and for settlement – on agriculture in the Pacific remain an open question; on the one hand prime-age and typically male labour is removed but on the other hand there is an increase in capital (remitted and repatriated) to fund productive investments.Footnote4 Gibson (Citation2015) found that adding international circular migration to the portfolio of available activities for a sample of mostly rural households in Vanuatu raised incomes without causing a rise in inequality; the schemes have greatly expanded since then so more economic differentiation may yet emerge.

What role is agriculture playing?

Given this limited structural transformation, the major role of agriculture is in providing food and livelihoods for most Pacific households. In this role, local policy often hinders because of a confusion between food security and self-sufficiency. For example, despite large increases in both total and urban populations, the locally produced share of dietary energy for Papua New Guineans stayed constant at about 80% over the last three decades (Sharp, Busse, & Bourke, Citation2022). Yet much policy focus is devoted to the small share of imported calories, with ongoing attempts to increase local production of cereals, especially rice (Gibson, Citation1994). This involves trying to produce a crop that is a poor agronomic fit with the environment and with indigenous farming systems and whose long-term real world price continues to fall for structural reasons (Timmer, Citation2009). In other words, the opportunity costs of local resources diverted into import-substituting rice production will ever rise due to unfavourable terms of trade with crops better suited to the Pacific.

Another barrier to improved agricultural policy is inadequate, unreliable, data due to under-funded and poorly focused statistical systems. For example, every year agriculture agencies in the Pacific report production to the FAO, for compilation into Food Balance Sheets. Yet measurement of indigenous food production does not inform these figures (in contrast to efforts spent measuring minor introduced food crops such as rice). The colonial era had micro-level measurement attempts for root crops and tree food crops (e.g. breadfruit), such as Conroy and Bridgland (Citation1947), but more recent figures are just extrapolations from earlier periods by assuming that food production keeps up with population growth. Even with proper efforts, root-crop farming systems are harder to measure than cereals-based ones. Production cannot be estimated remotely (e.g. by satellites); vegetative growth is not proportional to tuber production, especially after crop failures when the data would be most useful (Kanua, Bourke, Jinks, & Lowe, Citation2016). Harvesting is progressive, with second and third crops taken as the smaller tubers mature, and so no single point-in-time measurement can capture production like post-harvest surveys do in cereals-based farming systems. Households have complex margins of adjusting utilisation of food production which also complicates measurement. For example, PNG’s first national household consumption survey (Gibson & Rozelle, 1998) volumetrically measured consumption from own-production (respondents used standardised sacks to measure for two weeks and local weighing trials provided metric conversions), finding that national accounts understated household agricultural production by almost one-half (Gibson, Citation2001). Yet the imputed production of key staples like sweet potato was still far lower than estimates by expert agronomists; part of the gap was due to the survey just measuring food bought back to houses, and not everything grown in the food gardens – normally the opportunity cost of female time is such that small tubers are not harvested and instead left for pigs to eat in situ after the best tubers have been harvested for humans but if a food shortage looms the small tubers (and other in-ground food stores such as cassava roots) get harvested for humans.

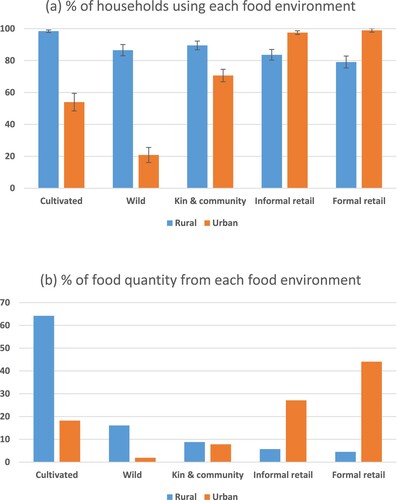

Despite these difficulties, carefully conducted household consumption surveys can provide some insights into Pacific agriculture. shows the reliance of Solomon Islanders on five types of ‘food environments’, which are the places or pathways through which people acquire or consume food. The evidence comes from the 2012/13 Household Income and Expenditure Survey which used a 14-day diary with bi-daily enumerator visits to weigh food production (Bogard et al., Citation2021). Urban households rely mostly on formal and informal retail but one-half also engage in urban gardening (‘cultivated’) – often on land with only informal tenure, which can create tensions with traditional landowners. The importance of common pool resources shows up in ‘wild’ food from rivers, reefs, lagoons, and forests; these food environments are used by one-fifth of urban households and by 85% of rural households. Such ‘wild’ foods are pro-poor (Gibson, Citation2018) but are rarely the focus of policy, and little is known about whether they are being over-exploited – as may be expected with settlers and traditional landowners unlikely to coalesce into Ostromian structures to govern the commons. The ‘kin and community’ food environment is used by over 80% of the population, reflecting the importance of the informal safety net and yet little is known about how this interacts with formal interventions (e.g. new safety net initiatives might crowd out informal arrangements).

Figure 1. Reliance on Different Food Environments in the Solomon Islands. NB: Error bars show 95% confidence interval. Source: Bogard et al. (Citation2021).

The data on quantities from each food environment (panel (b)) also highlight limits to policy. Over 80% of food consumed by rural households is either self-produced (‘cultivated’) or ‘wild’ and even though these foods can enter market channels the transactions costs are high (poor infrastructure, bulky crops) so pricing interventions likely have little effect. Perhaps agronomic research to improve productivity is one way for interventions to influence this large group (85% of households are rural) but much local agronomic research traditionally focused on introduced rather than indigenous crops and so was inversely proportionate to the dietary importance of foods. Moreover, there are challenges in disseminating improved varieties or techniques through a farming system that makes little use of purchased inputs and relies on vegetative propagation, compared to the circumstances that enabled rapid spread of high-yielding cereals varieties. While there is a germplasm collection at the Pacific Community’s Centre for Pacific Crops and Trees, much of the genetic diversity in the region is managed in situ by thousands of smallholder (and typically female) subsidence food crop farmers whose needs have been poorly met by many government agricultural agencies.

Conclusions

The most important role that agriculture is playing in development in the Pacific, to date, is providing sustenance for growing populations (especially in Melanesia) that are increasingly urban. A review of six decades of research on outdoor markets notes that selling fresh food provides income for more rural households in PNG than any other activity (Sharp et al., Citation2022). The same will be true in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. Yet the focus of much agricultural policy discussion is elsewhere; on export tree crops like coffee and cocoa, or on attempts to grow foods that are more efficient to import. Whether farming systems can continue to adapt to rising food demand fuelled by rapid population growth in the Melanesian countries remains an open question.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This reflects a far larger Polynesian diaspora, allowing possibility of family reunification migration, and is also due to concessional schemes such as the Samoan Quota and Pacific Access Category. Once migrants gain New Zealand citizenship they have access to live and work in Australia under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement, creating de facto preferences. So even with the proximity of Australia to Melanesia and the former colonial ties, there are also far more Polynesian than Melanesian emigrants in Australia, mirroring the situation in New Zealand: https://devpolicy.org/pacific-islanders-in-australia-where-are-the-melanesians-20140828/.

2 Moreover much logging in Melanesia is sea-based (due to limited roads) and harms reef and lagoon resources and inshore fisheries, which are important food sources for the coastal poor (Gibson, Citation2018).

3 It is an open question as to how much useful knowledge is transferred from working in horticulture in these two countries. While high altitude parts of Melanesia can be cold enough to grow some of the temperate crops that New Zealand specializes in, limited photoperiod variation hampers fruiting. Introduced vegetables such as cabbages and pumpkins have had more success. Likewise, the transfer of livestock farming technologies has been largely unsuccessful, with aid-driven village cattle projects in the 1970s and sheep projects in the 1990s failing. There has been more success with small livestock, such as poultry.

4 Transactions costs on remittances to the Pacific remain high despite more than a decade of policy attention, including aid agencies in Australia and New Zealand funding a cost comparisons site (sendmoneypacific.org) and supporting financial literacy interventions to help remitters choose lower cost providers. Moreover, many of the islands lack banking facilities, forcing reliance on in-person and other informal transfers.

References

- Bogard, J., Andrew, N., Farrell, P., Herrero, M., Sharp, M., & Tutuo, J. (2021). A typology of food environments in the Pacific region and their relationship to diet quality in Solomon Islands. Foods (basel, Switzerland), 10(11), 1–17. doi:10.3390/foods10112592

- Conroy, W., & Bridgland, L. (1947). Native agriculture in Papua New Guinea. Report of the New Guinea nutrition survey expedition. Canberra: Department of External Territories, pp. 72–91.

- Gibson, J. (1994). Rice self-sufficiency in Papua New Guinea. Review of Marketing and Agricultural Economics, 62(1), 63–77.

- Gibson, J. (2001). The economic and nutritional importance of household food production in PNG. Food Security for Papua New Guinea (ACIAR Proceedings, No. 99). RM Bourke, MG Allen and JG Salisbury (editors), pp. 37-44.

- Gibson, J. (2007). Is remoteness a cause of slow growth in the Pacific? A spatial econometric analysis. Pacific Economic Bulletin, 22(1), 83–101.

- Gibson, J. (2015). Circular migration, remittances and inequality in Vanuatu. New Zealand Population Review, 41(1), 153–167.

- Gibson, J. (2018). Forest loss and economic inequality in the Solomon Islands: Using small-area estimation to link environmental change to welfare outcomes. Ecological Economics, 148(1), 66–76. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.02.012

- Gibson, J., & Bailey, R. (2021). Seasonal labor mobility in the Pacific: Past impacts, future prospects. Asian Development Review, 38(1), 1–31. doi:10.1162/adev_a_00156

- Gibson, J., & Rozelle, S. (1998). Results of the household survey component of the 1996 poverty assessment for Papua New Guinea. Washington DC: Population and Human Resources Division,World Bank.

- Howes, S., Curtain, R., & Sharman, E. (2022). Labour mobility in the Pacific: transformational and/or negligible? DEVPOLICY BLOG, Australian National University. https://devpolicy.org/labour-mobility-in-the-pacific-transformational-and-or-negligible-20221010/.

- Howes, S., Mambon, K., & Samof, K. (2022). PNG’s minimum wage. DEVPOLICY BLOG, Australian National University. https://devpolicy.org/pngs-minimum-wage-20220928/.

- Kanua, M., Bourke, M., Jinks, B., & Lowe, M. (2016). Assessing village food needs following a natural disaster in Papua New Guinea. Church Partnership Program, Port Moresby. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/109282/1/Assessing-food-needs-following-a-natural-disaster-in-Papua-New-Guinea.pdf.

- Park, A., & Johnston, B. (1995). Rural development and dynamic externalities in Taiwan's structural transformation. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44(1), 181–208. doi:10.1086/452205

- Sharp, T., Busse, M., & Bourke, M. (2022). Market update: Sixty years of change in Papua New Guinea's fresh food marketplaces. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 9(3), 483–515. doi:10.1002/app5.368

- Timmer, C. P. (2009). Rice price formation in the short run and the long run: The role of market structure in explaining volatility. Working Paper No. 172, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC.