Abstract

SUMMARY: This article explores the development of coffin furniture in 18th- and early 19th-century London through analysis of the styles and motifs of items in contemporary trade catalogues and excavated assemblages. Developments in coffin furniture were compared with styles of headstones and monuments of the same period. This study confirmed and added detail to the disjunction between below- and above-ground funerary material culture, showing that coffin furniture was stylistically distinct from contemporary funerary monuments and developed at a slower rate. It is suggested that this was influenced by the development of undertaking and the mediated relationship between producers and consumers.

INTRODUCTION

Coffin furniture of the 18th and early 19th centuries has only been the subject of archaeological interest in the UK for around 30 years, and has not always been recognized as material that is worthy of careful excavation, preservation and research,1 and yet post-medieval burial archaeology has enormous research potential,2 of which the material culture of the grave is an important aspect, demonstrated by the publication of large assemblages in recent years, giving new insights into death and life in this period.3 This study aims to explore the stylistic development of coffin furniture in the period c. 1700–1850, examining both the material offered for trade sales in contemporary catalogues and items selected for use in London, excavated from burial grounds and vaults. The production and consumption of coffin furniture is examined in order to inform exploration of its meanings and the factors that influenced its development, in the context of commercialization and the development of the profession of undertaking and associated funeral furnishers and suppliers.

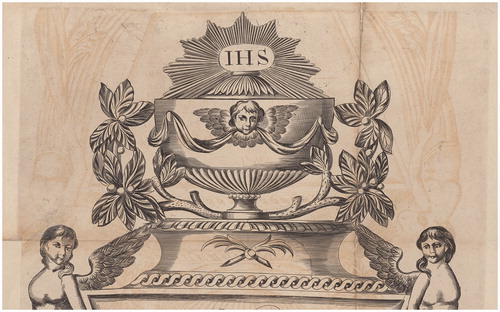

Coffin furniture consists of the metal items attached to coffins. During the period under study, the use of coffin furniture increased dramatically, and a full set consisted of a breastplate (sometimes known as a depositum plate), handles (known as grips), decorative grip plates and large and small decorative plates, known as lid motifs and escutcheons or drops respectively. By the early 18th century, a coffin was a minimum expectation for a ‘decent’ burial,4 and they were widely used by the 19th century,5 but the most basic pauper funerals did not include coffin furniture at all, and comparisons of excavated burials of poor burial grounds and those of wealthy parishes demonstrate a vast difference in the quantity and quality of coffin furniture. No breastplates were found on the coffins of poor patients interred in the early 19th-century burial ground at the London Hospital, although the excavators noted that all were probably originally coffined, and only one of 111 coffins recorded had iron grips, the others being entirely plain.6 Excavations of mid 19th-century burials at the Cross Bones burial ground, the ‘poor ground’ of the parish, found that only 23.4% of the coffins had any surviving decoration.7 By contrast, most coffins at the burial ground of the wealthier parish of Chelsea Old Church had decorative upholstery studs, with lead plates and a range of grips also identified.8 The cost of a coffin varied widely depending on the materials and quantities of fittings used. More expensive coffins could include larger individual elements such as breastplates and grip plates, as well as large numbers of escutcheons. The large ‘glory and urn’ lid motif sets are more expensive than ‘angel and flowerpot’ sets () in both the trade catalogues and an 1838 trade price list,9 for example, and one of the more expensive coffins in the trade price list of 1838 included eight dozen escutcheons.10 Lead plates are mainly associated with burials in vaults and therefore with more expensive coffins, as interment in vaults beneath churches carried higher burial fees and usually required a triple-shelled coffin, with the central layer made of lead. Tinplate (tin-dipped iron) breastplates were significantly cheaper.11 The earliest stamped tinplate breastplates were produced towards the end of the 17th century and, in 1769, a new production method was patented, enabling higher levels of production.12 Surface treatments, such as paint or shellac, could also add to the cost of coffin furniture bought by undertakers and funerary furnishers, and these costs were passed on to purchasers with a large mark-up.13

Fig. 1 ‘Angel and flowerpot’ lid motif design from a trade catalogue of c. 1783. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Analysis of chronological change in the excavated assemblages has focused on breastplates, as they are the most accurately dated items. In addition, breastplates are the largest and most elaborate items, with, therefore, the largest range of motifs on any item on a coffin. They were also of primary contemporary importance: the service provided by one undertaker for the London Poor Law Union in the early 19th century included a plain coffin, but relatives could pay for extra elements, including a plate with a painted inscription,14 and a later report on pauper burials noted that even these cheapest coffins had a ‘scanty tin plate’ with the name and age inscribed,15 suggesting that, by the 1880s, a breastplate, at the very least, had become a minimum expectation.

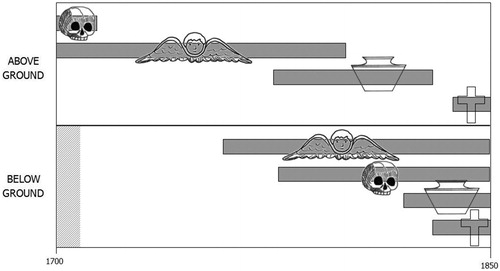

Coffin furniture might be expected to develop in similar ways to headstones and monuments, and work on the symbolism of coffin furniture motifs has drawn on research on symbolism of monuments, such as that of Frederick Burgess, Betty Willsher, Harold Mytum and Julian Litten.16 Headstones in the 18th century show a shift from symbols of mortality, such as skulls, hourglasses and scythes, to symbols of resurrection, such as cherubs and angels with trumpets.17 A recent study combining samples of monuments from different regions confirms this overall pattern, while recognizing regional variations, and also charts the use of urns in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and the introduction of Gothic revival styles from the 1840s.18 The well-known work by Edwin Dethlefsen and James Deetz on New England gravestones has also been influential, suggesting that changes in gravestone designs related to a change in religious values and attitudes to death in this period.19 However, Jonathan Finch’s detailed examination of the iconography of wall monuments in Norfolk suggests that changes in style in the 18th century are better explained by the commodification of monuments, leading to the importance of fashion in consumer choice, rather than ideological explanations.20 Further, he suggests that meanings cannot be straightforwardly ascribed to motifs, as ‘fashion intervened between the artefact and its symbolic meaning’.21 Adam R. Heinrich has also suggested that the ubiquitous winged cherub heads on New England gravestones were the result of Rococo fashion in England spreading to the American colonies in the early 18th century, ascribing their popularity to consumer choice rather than to religious symbolism, as has previously been supposed.22

RESEARCH AIMS

This study considers how coffin furniture changed in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and whether the motifs used show chronological development. Coffin furniture designs of this period are compared with contemporary funerary monuments to explore the relationship between above- and below-ground funerary material culture. The conservatism of coffin furniture styles has been noted in previous and recent work on mortuary material culture of this period,23 as well as the continued use of particular styles over many years,24 and this study explores this in detail. It also aims to examine the impact of the funerary industry on the consumption of coffin furniture in this period.

METHODOLOGY

Coffin furniture from the London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre (LAARC) and the three trade catalogues of the period in the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) collections were analysed to enable comparison between the range of styles produced and those selected for consumption. The excavated coffin furniture examined consisted of previously published material from Christ Church Spitalfields25 and St Pancras26 and small, unpublished assemblages from Christ Church Greyfriars27 and Broadgate,28 which were catalogued in detail. The assemblages were selected in order to analyse representative material across the full date range of the study (1708–1857) from both vault and flat cemetery burials. The trade catalogues produced by coffin furniture manufacturers are dated to c. 1783,29 c. 1821–430 and c. 1826.31 The c. 1783 catalogue was produced by Tuesby and Cooper, a ‘Coffin Furniture & Ironmongery Warehouse’ in Borough, London. Although clearly supplying the London market, it is unclear where their stock was manufactured. At this date, it may have been in London or Birmingham, where coffin furniture was produced from the mid 18th century.32 The catalogue of c. 1826 is almost certainly that of Edward Lingard, a Birmingham manufacturer.33 The c. 1821–4 catalogue has not been associated with a particular maker, and may also be from Birmingham. A system of coding of each motif was developed, based on that devised by Harold Mytum for recording gravestones,34 and adapted to include all motifs found on coffin furniture. Every item in the trade catalogues, each breastplate type identified in the Christ Church Spitalfields35 and St Pancras36 assemblages, and any additional types in the unpublished assemblages were recorded by type, and the motifs were identified and recorded. The Christ Church Spitalfields and St Pancras types were cross-referenced so that designs common to both typologies were noted. Analysis of chronological change in the excavated assemblages focused on breastplates, as in many cases they retain the inscribed date of death, so are the most accurately dated items. The three trade catalogues were examined to discern similarities and differences between designs over time, and dated breastplates from the excavated assemblages were also analysed to identify the persistence of motifs and the development of plate types. Comparisons between the catalogues and excavated assemblages were made to examine similarities and differences between items that were produced and those selected for use. The assemblages were also compared with headstones and wall monuments of the period, both in general, drawing on previous studies37 as well as specifically with the catalogues of wall monuments at Christ Church Spitalfields38 and the catalogue of selected headstones from St Pancras.39

RESULTS

Analysis and comparison of the trade catalogues and excavated material revealed a pronounced stability of design throughout the period.

CATALOGUES

Of the eight plates in the c. 1783 catalogue, six are found in one or more of the later catalogues. When examined closely, these designs are very consistent with those in the later catalogues, dated to around 40 years later, although with subtle stylistic differences, such as increased symmetry and greater regularity in later versions. It is also possible that these small changes represent a change in how the items were illustrated, rather than in the objects themselves. There are two plate types from this earliest catalogue that are not in the later catalogues. However, one of these (V&A E.998-1902, pl. 50), an infant’s plate consisting of a drapery backdrop with winged cherub heads at the top and bottom, is very similar to another plate (V&A E.997.1902, pl. 51) in the same catalogue, a child’s plate in which the lower cherub is replace by a winged skull, which is also in the c. 1821–4 catalogue (V&A E.1009-1978, pl. 1023). The other (V&A E.1006-1902, pl. 59) is a very large, elaborate plate, which includes two cherubs holding a crown with radiance over a skull at the top in the centre. A fragment of this type was found at Spitalfields, dated to 1794, and an undated fragment was recovered at St Pancras (type 13). In many of the similar plates in the later catalogues with angels or cherubs and a radiant crown, the skull is replaced by a dove, representing the Holy Spirit (e.g. V&A E.3100-1910, pl. 602), or, rarely, an urn (e.g. V&A E.3103-1910, pl. 54) in place of the skull. While the earlier plate does also include a dove, it is near the lower edge of the plate and the skull is clearly in a more prominent position. Additionally, a change in the escutcheon illustrated on the first pages of both the c. 1783 catalogue and the c. 1826 catalogue is noticeable. The first pages of both catalogues are very similar, with decorative letters and numbers and a single escutcheon on both. The earlier escutcheon includes an hourglass and scythe, both symbols of mortality (V&A E.997-1902, ornament 155). In the later example, the mortality symbols are absent and the top of the escutcheon is more regular in form (V&A E.3096-1910, ornament 144). The predominance of the Holy Spirit motif in the later plates could suggest a shift from symbols of mortality to symbols of resurrection. However, the overall number of items with mortality motifs in the catalogues, aside from crucifixes, is very low. Of 48 items with motifs in the earliest catalogue, only seven include motifs of mortality, and nine appear in the catalogue dated c. 1826, of 148 items with motifs. This may be explained by the fact that all were produced after the date when mortality motifs were used on funerary monuments, suggested by Frederick Burgess as being in the 17th and early 18th centuries.40 On the other hand, the continued supply of items with skull motifs in the 1780s, and even into the 1820s, supports the view that styles of coffin furniture were conservative.

EXCAVATED MATERIAL

The excavated breastplates analysed, dated 1729–1852, also demonstrated a pronounced lack of development of motifs in items selected for use, despite some limited stylistic development. One change in design that is clear from the excavated material is a shift from Rococo to classical forms in a widely used breastplate type. One of the most commonly found lead breastplate forms is rectangular with a shield at the top centre with flowers or foliage either side. Of the 114 breastplate types identified at Spitalfields, 22 are of this form, although one is trapezoidal. There are no parallels in the catalogues for any of these types, and the possibility that the two later catalogues are not fully representative of the supply to London funeral furnishers and undertakers has been considered. However, the growing dominance of Birmingham as a centre for coffin furniture manufacture in the 19th century suggests that the availability of styles in London is unlikely to have differed significantly from those illustrated, and, while a comment by a manufacturer in an article published towards the end of the period in question refers to regional and national preferences in coffin furniture, these relate to surface treatments and quantities, rather than choices of motifs.41 Furthermore, none of the St Pancras plates are of this ‘shield and flowers’ type, reinforcing the view that the designs in the catalogues are more associated with tinplate, although a few catalogue designs are found on lead plates. These 22 types range in date from 1765 to 1852 at Spitalfields, and include 86 plates. They show a clear shift over time from a Rococo-style central shield to a classical shield shape, which was previously noted by Adrian Miles in his analysis of the lead plates at St Marylebone.42 Those with a Rococo-style shield are dated 1765–1825 at Spitalfields and those with a classical shield, which are also more symmetrical in design, date from 1820 to 1852. This shift can also be seen in the assemblage from Christ Church Greyfriars (CCN80, pls 93 and 102), and the incomplete and undated plate from this assemblage which includes a Rococo-style shield (CCN80 pl. 108) can therefore be dated with some confidence to no later than 1825.

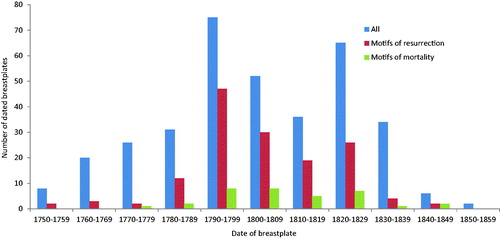

However, in other respects the lack of variation over time was notable. The excavated breastplates analysed also had a low level of mortality motifs, with motifs of resurrection dominating. compares plate types from Christ Church Spitalfields and St Pancras by the date range and median dates of all plates, plates containing motifs of mortality and plates containing motifs of resurrection. In all cases this refers to plates that retain a complete year of death. The mortality motifs are skulls, bones, hourglasses, scythes and Father Time. The resurrection motifs analysed here are cherubs, angels, palms, branches of bay leaves and crowns, representing respectively the winged soul, angels of the resurrection, victory over death and the reward of a Christian life.43

TABLE 1 Motifs of mortality and resurrection on coffin breastplates from Christ Church Spitalfields and St Pancras.

Of the 114 Spitalfields plate types, only five include any motifs of mortality and, in general, these are very small: a tiny skull and crossed longbones are included in the large and elaborate plate type 6, for example. There are 28 dated plates of these four types, and these actually have a slightly later average date than the dated plates as a whole, with a mean and median date of 1811, compared with a mean date of 1801 and a median date of 1803 for all plates. At St Pancras only three plate types include mortality motifs (plate types 9 (), 13 and 29). The six dated plates are all of type 29, which is also Spitalfields type 6, where the skull and longbones form a very small part of a large and complex plate. At St Pancras this plate has a date range of 1800–9, but is found at other sites with a combined range of 1783–1847,44 so the mortality symbolism on this plate does not appear to be chronologically significant.

Fig. 2 St Pancras breastplate (type 9) with motifs of mortality (winged skull) and resurrection (winged cherub heads). Courtesy of the Museum of London.

Motifs of resurrection are found on a large proportion of the plates from St Pancras, which are overwhelmingly tin-dipped iron plates. The date ranges and median dates of plates with motifs of resurrection are very similar to those of all plates in both assemblages. The lower proportion of motifs of resurrection and the later median date at Spitalfields may be explained by the stronger association of cherub and angel motifs with tinplate breastplates, which, at Spitalfields, tended to be used later in the period of use of the vaults. The chart () combines data from the Christ Church Spitalfields, St Pancras and Christ Church Greyfriars assemblages for the period in which motifs of mortality and/or resurrection were noted on dated breastplates (1757–1849). This demonstrates the prevalence of motifs of resurrection throughout the period in question, the low numbers of motifs of mortality and their persistence to the end of the 1840s.

COMPARISON WITH MONUMENTS

In his study of English churchyard monuments, Frederick Burgess noted that motifs of the means of salvation, such as allegorical figures of theological virtues, biblical texts and representations of judgement and resurrection, appear on monuments ‘during the last fifty years of the Georgian period’.45 All three trade catalogues fall within this period of the 1780s to 1830s, but none of the illustrated breastplates—or excavated examples—include these more elaborate scenes, although many are large enough to have accommodated them.

Urns are ubiquitous on wall monuments in the 19th century and a popular motif on headstones.46 At Christ Church Spitalfields a clear difference can be seen between the tall urn on a monument of 1737 and the later wide urns, which are the only decorative motif on monuments of 1823, 1831 and 1840.47 These wide urns are found in the later trade catalogues, but in only a small proportion of the designs. Furthermore, other than on one grip accompanied only by palm leaves, the wide urn appears alongside a range of other motifs including cherubs, angels and foliage, rather than in stark isolation, as on the church monuments ().

Fig. 4 Breastplate design (detail) featuring urns from a trade catalogue of c. 1783. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Frederick Burgess described how the Gothic revival in the 1830s re-established the popularity of the cross as a motif on monuments.48 Of the church monuments from Christ Church Spitalfields (sixteen in total, six dated 1830 or later), only one includes any kind of cross, and this appears to be heraldic.49 However, 25 headstones from St Pancras contain a cross, of which 23 are dated, ranging from 1709 to 1845.50 Only nine date to the 19th century, three of which were dated to 1830 or later. However, the headstones of St Pancras may be seen as anomalous, in that a significant proportion of those buried there were Roman Catholic.51 Crosses appear only rarely in breastplate designs, although the later catalogues include crucifix lid motifs and four of the twelve lid motif types at St Pancras are crucifixes.52 These obviated a need for the inclusion of crosses on plates. The three plates that included a cross motif from Spitalfields are dated from the 1830s and 1840s, as expected, but the low numbers and the fact that all were of a single type suggests that the Gothic revival had only a limited impact on the designs of coffin furniture by the time of the last interment in 1857. These differences between the use of motifs in above- and below-ground funerary material culture in this period are summarized in .

Fig. 5 Comparison of motifs used on above- and below-ground funerary material culture. Above ground: the development of headstone motifs (after Burgess 1963). Below ground: the date range of selected motifs on coffin breastplates in this study: mortality, resurrection, urns and crosses. The earliest excavated breastplate in the studied assemblages is dated 1708 (indicated by the shaded area) and those with at least one of these motifs date between 1757 and 1849.

INTERPRETATION

It has been suggested that the method of manufacturing was a factor in the slow development of coffin furniture designs, due to the cost of creating new die-stamps.53 However, it seems unlikely that manufacturers in the growing metal goods industry in Birmingham and elsewhere in the late 18th and early 19th centuries would not have responded to market demands for novelty as they did with other items, such as medals.54 Furthermore, the use of drop stamp technology has been described as ‘cheap and adaptable’.55 Rather than resting with manufacturers, the responsibility for the slow development of styles must lie either with their customers, the undertakers and funeral furnishers, or with the eventual purchasers, the bereaved family and friends of the deceased, or both.

Clearly, there are important differences between the purposes and uses of coffin furniture and the headstones and monuments of this period, and Harold Mytum has suggested that these roles may be a factor in the differing rates of development.56 Some material objects associated with death are intended for permanent preservation and some are temporary and destined to decay.57 Coffin furniture is of the latter type, designed to be visible for a limited, if intensely emotional time (the use of plates in vault burials to assist sextons in interring family members together is only a partial exception). Throughout this period it was usual at all levels of society for the corpse to remain within the house until the funeral and to be viewed by the family and friends of the deceased.58 The viewing of the coffin was a common aspect of mourning for public figures, and illustrations of lyings-in-state show the coffins uncovered and the rich decoration visible.59 The visibility of the coffin was otherwise limited; hearses could be closed, and, whether carried on foot or transported by hearse, the coffin would, at all but the very cheapest funerals, be covered by a pall60 and remained covered until the interment. The role, then, of the coffin in funerary rituals was brief, mainly visible to friends and relatives, whereas an important aspect of monuments is that they were publicly and permanently visible. However, in the period between death and burial, the corpse was the centre of attention61 and the coffin, as the container for the body and the visible representation of the deceased once the lid was sealed for the funeral, was the focus for the burial rituals. Although the coffin would not have been visible for long, its emotional significance as the representation of the deceased may be imagined to have emphasized its impact on those who saw it.

Consumer demand drove the dramatic increase in the use of coffin furniture in this period, facilitated by technological changes that increased availability. However, it does not appear to have had an impact on design. It has been suggested that coffin furniture was chosen by undertakers, rather than their clients,62 and this is supported by evidence from Chadwick’s Citation1843 enquiry in which a client was described as having requested a ‘respectable’ funeral, rather than giving a specific order.63 The funeral registers of an undertaker in Ipswich in the late 18th and early 19th centuries indicate that the undertaker made most decisions on funeral arrangements.64 This is in contrast with the purchase of gravestones. A study in York noted that Victorian purchasers of gravestones obtained them directly from the producer,65 suggesting a much higher engagement with selection than has been suggested for the furnishing of a coffin. Harold Mytum has also suggested that ‘there may have been weaker consumer control at the time of the funeral than by the time that memorials were commissioned’,66 and has attributed this to the different stages of the grieving process within which choices of coffins and monuments were made.67 Headstones also offered the opportunity for more personal choice and elaboration. Although some designs were standard, the lettering had to be inscribed by hand, and it was possible to include more detail than on coffin breastplates, such as information on family relationships.68

The first undertakers appeared in London in the late 17th century, and their numbers increased significantly through the 18th and early 19th centuries.69 By the 19th century, the funerary industry had become layered and complex, with layers of subcontractors adding to rising costs.70 Always regarded with a degree of ambivalence, towards the end of this period the profession as a whole was increasingly viewed with suspicion or hostility by those who variously held it responsible for excessive expenditure, promotion of un-Christian iconography and the menaces to public health caused by burial practices.71

If, as suggested above, consumers preferred—by choice or custom—to allow undertakers to select or provide guidance on customary coffin furniture, then undertakers (and other funerary suppliers) were well placed to influence the development of designs from their intermediary position as both consumers and suppliers. A coffin furniture manufacturer reported in 1851 that it was demand from undertakers that prompted new designs, rather than from bereaved relatives, as ‘They either are, or affect to be, too much afflicted to look after such matters themselves’.72 It is unclear whether this demand for novelty was apparent earlier in the period in question and whether it was widespread. Certainly, it does not appear to be reflected in the material analysed in this study. The same manufacturer described purchasing plate designs including ‘heads of cherubim’,73 so even ‘new’ designs included motifs that were already outdated outside of a burial context. The continued use of shapes with heraldic significance,74 although not always correctly applied in practice,75 suggests the appropriation of established practices and their application to new materials and customers. This could represent an appeal to tradition by a new profession under pressure and attempting to establish respectability.

CONCLUSIONS

An issue with comparing headstones and monuments with coffin furniture is that the latter was much more widely accessible to bereaved purchasers, and so one aspect of the differences between the two may lie in the inequalities in (average) wealth and/or status between those whose loved ones could afford monuments and those who could not. Although the headstones and monuments analysed in this study related to the same burial population as the coffin furniture, the samples were small and direct comparisons for individuals were not possible. Furthermore, the key studies of funerary monuments consulted are either general,76 or based on material from areas other than London.77 While the overall developments may be expected to be similar, chronological differences between areas may be expected. A wider problem is that headstones (cheaper than church monuments and therefore potentially reflecting a higher proportion of the buried population) are vulnerable to weathering, pollution and cemetery clearance, and few legible examples survive in central London, in contrast with rates of surviving memorials in comparison with burials in rural and small town burial grounds.78 A study in Leicestershire found a wide disparity between the proportion of individuals recorded in burial registers with surviving monuments between rural and urban parishes, with a much lower proportion of people commemorated in urban graveyards, which the authors ascribe to a range of factors, including burial density and post-depositional losses.79 The selective retention of larger and more prestigious examples further skews the material available for study in favour of those relating to richer and more famous individuals.

The material studied covers a limited time frame. The coffin furniture trade catalogues date to between c. 1783 and c. 1826 (and the earlier two, at least, are incomplete), representing only around 43 years of the period in question. Although the excavated coffin plates cover a longer period, those from the larger assemblages date from 1729 onwards, with the median date around 1800. Despite this, the lack of stylistic development still contrasts with the changes noted more generally in monuments and headstones of the same date, specifically those recorded at Christ Church Spitalfields80 and St Pancras.81

The changes observed in coffin furniture between the 18th and mid 19th century are changes of degree, rather than changes of kind. Many motifs persist throughout the period, but some change in subtle ways. Overall, the long-term similarities are more apparent: most plates in all three catalogues and the tin-dipped iron plates of the excavated assemblages contain cherubs, angels or both, and the vast majority contain floral or foliate decoration. Acanthus leaves, very often in combination with scrolls, are also ubiquitous, although these became more regular and stylized over time.

It is clear from the comparison of the general forms and specific motifs of headstones, church monuments and coffin furniture that each had a distinct visual language, with only limited overlap, and that they diverged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The densely elaborate decoration of coffin furniture, motifs ‘mingled together in a glorious confusion’, as Augustus Pugin critically noted,82 is in marked contrast to the classical simplicity of church monuments and plainness of headstones in the early 19th century. Despite limited developments, many of those buried in the 1840s were interred in coffins with furniture that was essentially late 18th century in design. The longevity of these styles, already traditional, if not outdated, by the mid 19th century, can be seen by the fact that some continue to appear, as ‘general furniture’ (to be used for ‘parish work’),83 in a catalogue of the 1920s.84

It is suggested that the conservatism of below-ground funerary material culture in the 18th and early 19th centuries is related to the practice of undertakers having control over the choice of designs and styles used. This represents a group of specialists managing the below-ground aspects of the funerary rites, in this case as providers of a service for which bereaved consumers would pay. This may have implications for contexts other than later-historical England, as a case study for places and times where intermediary specialists controlled below-ground aspects of funerary rites, leading to slow or imperceptible changes in below-ground rites, but a faster rate of change in above-ground memorials.

This study confirms the disjunction between coffin furniture designs and the design of contemporary headstones and church monuments, leading to a distinct material culture of the grave, styles of which developed at a slower rate than those of funerary monuments above ground. This disjunction and the longevity of designs and motifs of coffin furniture could be explained by the unique nature of the use and consumption of these items, as it can be argued that the growth and nature of the funerary industry, and the way that transactions between undertakers and clients appear to have been structured, militated against wholesale innovation.

Further research, currently underway, seeks to expand upon the results reported in this paper. In particular, it aims to examine the nature of the mediated relationship between the production, consumption and stylistic development of coffin furniture during the 18th and 19th centuries.

| ABBREVIATIONS | ||

| LAARC | = | London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre |

| V&A | = | Victoria and Albert Museum Collections |

SUMMARY IN FRENCH, GERMAN, ITALIAN AND SPANISH

RÉSUMÉ

Meubles de cercueil à Londres vers 1700–1850: l’établissement d'une tradition dans la culture matérielle de la sépulture

Cet article explore le développement des meubles de cercueil au XVIIIe et au début du XIXe siècle à Londres à travers l’analyse des styles et motifs des objets des catalogues de commerce contemporains et des assemblages mis au jour. Les développements du mobilier de cercueil ont été comparés aux styles de pierres tombales et monuments de la même période. Cette étude confirme et détaille la disjonction entre les cultures matérielles funéraires hors-sol et sous-terre, montrant ainsi que le mobilier de cercueil était stylistiquement distinct des monuments funéraires contemporains et s’est développé moins rapidement. Le développement de l’entreprise funéraire et la relation particulière de médiateur entre producteurs et consommateurs de ce mobilier peuvent avoir influencé cette distinction.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Sarg-Ausstattung in London c. 1700–1850: die Entwicklung der Tradition in der materiellen Kultur der Gräber

Dieser Artikel untersucht die Entwicklung der Sarg-Ausstattung im 18. und frühen 19. Jahrhundert in London, durch Analyse der Stile und Motiv-Elemente in derzeitigen Handelskatalogen und ausgegrabenen Sammlungen. Die Entwicklungen der Sarg-Ausstattung wurden mit Arten der Grabsteine und Denkmäler aus der gleichen Zeit verglichen. Diese Studie bestätigt die Trennung zwischen unter- und oberirdischen Grabbeigaben materieller Kultur und zeigt, dass Sarg-Ausstattungen sich stilistisch unterschiedlich von heutigen Grabdenkmälern, in einem langsameren Tempo entwickelten. Es wird vorgeschlagen, dass dies durch die Entwicklung der Begräbnis-Unternehmen beeinflusst wurde, sowie durch die vermittelten Beziehungen zwischen Erzeugern und Verbrauchern.

RIASSUNTO

Bare in legno a Londra (1700–1850 ca.): la creazione di una tradizione nella cultura materiale della tomba

Questo articolo esplora l’evoluzione delle bare in legno nella Londra del XVIII secolo e dell’inizio del XIX attraverso l’analisi dei diversi stili e dei motivi decorativi degli articoli presenti nei cataloghi commerciali dell’epoca e nei depositi scavati. L’evoluzione stilistica delle bare è messa a confronto con quella di lapidi e monumenti funebri dello stesso periodo. Questo studio ha confermato, aggiungendo dettagli, l’incongruenza fra la cultura materiale funeraria ‘sopra al suolo’ rispetto a quella ‘sepolta’: le bare erano stilisticamente diverse dai monumenti funerari coevi e cambiavano più lentamente. Viene suggerito come questo processo sia stato influenzato dalla relazione mediata fra produttori e clientela attraverso lo sviluppo del settore.

RESUMEN

Apliques de ataúd en Londres en c. 1700–1850: el inicio de una tradición en la cultura material del enterramiento

Este artículo explora la evolución de los apliques de ataúd utilizados en Londres en el siglo XVIII y principios del siglo XIX mediante el análisis de los estilos y motivos que aparecen en los catálogos comerciales contemporáneos y de ejemplos excavados. Su evolución se compara además con lápidas y monumentos del mismo período. Este estudio confirma y añade detalles a la separación existente entre la cultura del material funeraria utilizada sobre el suelo y por debajo de él, mostrando que los apliques del ataúd eran estilísticamente distintos de los monumentos funerarios contemporáneos y se desarrollaron a un ritmo más lento. Sugerimos además que el nacimiento de las funerarias tuvo una influencia importante al mediar entre productores y consumidores.

Sarah Hoile, UCL Institute of Archaeology, 31-4 Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PY, UK

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study formed part of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MA at University College London in 2013. Ongoing related research is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council through the London Arts and Humanities Partnership.

I am very grateful to Professor Mike Parker Pearson for his support and guidance during the preparation of this article, and as supervisor of the Master’s dissertation on which it is based, and to Dr Ulrike Sommer and Professor Stephen Shennan for their feedback and encouragement. I would also like to thank Francis Grew and Steve Tucker at the London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre (LAARC) for their advice and guidance during my research, and Stephanie Bonnici-Smith and Anna Bloxam for comments on the dissertation and a previous draft of this article respectively. Dr Hilda Maclean very kindly shared her knowledge of Birmingham coffin furniture manufacturers and Professor Harold Mytum sent me a copy of his recent chapter ahead of publication, for which I am very grateful. I would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Notes

1 Sayer & Symonds Citation2004, 57.

2 Mytum 2017; Renshaw & Powers Citation2016; Tarlow Citation2015.

3 e.g. (from London) Boston et al. Citation2009; Boyle, Boston & Witkin Citation2005; Emery & Wooldridge Citation2011; Henderson, Miles & Walker Citation2013; Citation2015; Miles, Powers & Wroe-Brown 2008.

4 Houlbrooke Citation1999, 193.

5 Cherryson, Crossland & Tarlow Citation2012, 60.

6 Fowler & Powers Citation2012, 33.

7 Brickley & Miles Citation1999, 26.

8 Miles Citation2008.

9 Turner Citation1838.

10 Turner 1838, 4.

11 Turner 1838, 10.

12 Litten Citation1998, 14; Rugg Citation1999, 222.

13 Litten Citation1991, 29.

14 Litten Citation1991, 165.

15 Greenwood Citation1883, 74.

16 Burgess 1963; Litten Citation2004–10; Mytum Citation2000; Willsher Citation1985.

17 Burgess 1963, 165–6.

18 Mytum Citation2018.

19 Dethlefsen & Deetz Citation1966.

20 Finch 2000, 169.

21 Finch 2000, 169.

22 Heinrich Citation2014.

23 Gentle & Feild Citation1975, 105; Miles Citation2011a, 176; Mytum Citation2015, 275; Citation2017, 168.

24 Boyle, Boston & Witkin 2005, 100.

25 Reeve & Adams Citation1993.

26 Emery & Wooldridge Citation2011.

27 LAARC, CHR76 and CCN80.

28 LAARC, LSS85.

29 V&A, E.997 to E.1011-1902.

30 V&A, E.994 to E.1022-1978.

31 V&A, E.3096 to E.3134-1910.

32 Church & Smith Citation1966, 621.

33 Hilda Maclean, pers. comm.

34 Mytum 2000.

35 Data on the coffin furniture of Christ Church Spitalfields were derived from the digital archive deposited with the Archaeological Data Service by the Spitalfields Project team (Friends of Christ Church Spitalfields 2003). Those who carried out the original collection of the data bear no responsibility for the analysis and interpretation in this paper.

36 Miles Citation2011b.

37 Burgess 1963; Finch Citation2000; Willsher 1985.

38 Friends of Christ Church Spitalfields 2015.

39 Rendall Citation2011.

40 Burgess 1963.

41 Anon. Citation1851, 6.

42 Miles, Powers & Wroe-Brown Citation2008, 60; Miles, Ritchie and Wroe-Brown Citation2015.

43 Burgess 1963, 178; Willsher 1985, 28–9.

44 Miles 2011b, 9.

45 Burgess 1963, 166.

46 Finch 2000, 148.

47 Friends of Christ Church Spitalfields Citation2015.

48 Burgess 1963, 167.

49 Monument to Elizabeth Catherine Graves Boyd, 1836, Friends of Christ Church Spitalfields 2015.

50 Rendall 2011.

51 Emery & Wooldridge Citation2011.

52 Miles 2011b, 14–17.

53 Richmond Citation1999, 150.

54 Anon. 1851, 6.

55 Courtney Citation2000, 164.

56 Mytum Citation2004, 106; Citation2018.

57 Hallam & Hockey Citation2001, 9.

58 Hotz Citation2001, 23; Jalland Citation1996, 213–14; Misson Citation1719, 90–2.

59 Litten 1991, 167 fig. 82, 168 fig. 83.

60 Litten 1991, 127.

61 Hotz 2001, 23.

62 Litten 1991, 30; Mytum 2015, 277.

63 Chadwick 1843, 50.

64 Fritz Citation1994–5, 248.

65 Buckham Citation1999, 201.

66 Mytum Citation2006, 105.

67 Mytum Citation2018.

68 Tarlow Citation1999, 74.

69 Fritz 1994–5.

70 Morley Citation1971, 24.

71 Howarth Citation1997, 124.

72 Anon. 1851, 6.

73 Anon. 1851, 6.

74 Litten 1991, 109.

75 Mahoney-Swales, O’Neill & Willmott Citation2011, 221.

76 Burgess Citation1963.

77 Finch 2000; Tarlow Citation1999.

78 Mytum Citation2002.

79 University of Leicester Graveyards Group Citation2012.

80 Friends of Christ Church Spitalfields 2015.

81 Rendall 2011.

82 Pugin Citation1844, 72.

83 Plume c. Citation1910, 18.

84 Dottridge Brothers c. Citation1925, 32.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Anon. 1851, ‘Labour and the Poor—Birmingham (from our special correspondent), Die-Sinkers, Medallists, Coiners &c. Letter XVII’, The Morning Chronicle, 10 February 1851, 5–6.

- Boston, C., Boyle, A., Gill, J. & Witkin, A. 2009, ‘In the Vaults Beneath’: Archaeological Recording at St George’s Church, Bloomsbury, Oxford Archaeol. Monogr. 8.

- Boyle, A., Boston, C. & Witkin, A. 2005, The Archaeological Experience at St Luke’s Church, Islington, Oxford: Oxford Archaeology.

- Brickley, M. & Miles, A. 1999, The Cross Bones Burial Ground, Redcross Way Southwark, London: Archaeological Excavations (1991–1998) for the London Underground Limited Jubilee Line Extension Project, London: Museum of London Archaeology Service and Jubilee Line Extension Project, MoLAS Monogr. 3.

- Brooks, A. (ed.) 2015, The Importance of British Material Culture to Historical Archaeologies of the Nineteenth Century, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Buckham, S. 1999, ‘“The men that worked for England they have their graves at home”: consumerist issues within the production and purchase of gravestones in Victorian York’, in Tarlow & West 1999, 199–214.

- Burgess, F. 1963, English Churchyard Memorials, Cambridge: Lutterworth Press.

- Chadwick, E. 1843, Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. A Supplementary Report on the Results of a Special Inquiry into the Practice of Interment in Towns, London: W. Clowes and Sons for HMSO.

- Cherryson, A., Crossland, Z. & Tarlow, S. 2012, A Fine and Private Place: the Archaeology of Death and Burial in Post-Medieval Britain and Ireland, Leicester: Sch. of Archaeol. and Anc. Hist., Univ. of Leicester, Leicester Archaeol. Monogr. 22.

- Church, R.A. & Smith, M.D. 1966, ‘Competition and monopoly in the coffin furniture industry, 1870–1915’, The Economic History Review. 19:3, 621–41.

- Courtney, Y. 2000, ‘Pub tokens: material culture and regional marketing patterns in Victorian England and Wales’, International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 4:2, 159–90.

- Cowie, R., Bekvalac, J. & Kausmally, T. 2008, Late 17th- to 19th-Century Burial and Earlier Occupation at All Saints, Chelsea Old Church, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, MOLAS Archaeol. Stud. Ser. 18.

- Cox, M. (ed.) 1998, Grave Concerns: Death and Burial in England 1700 to 1850, Counc. Brit. Archaeol. Res. Rep. 113.

- Dethlefsen, E. & Deetz, J. 1966, ‘Death’s heads, cherubs and willow trees: experimental archaeology in colonial cemeteries’, Am. Antiq. 31:4, 502–10.

- Dottridge Brothers Ltd c. 1925, (General catalogue) [of coffins and mortuary fittings]. London.

- Downes, J. & Pollard, T. (eds) 1999, The Loved Body’s Corruption: Archaeological Contributions to the Study of Human Mortality, Glasgow: Scottish Archaeological Forum, Cruithne Press.

- Emery, P.A. & Wooldridge, K. 2011, St Pancras Burial Ground: Excavations for St Pancras International, the London Terminus of High Speed 1, 2002–3, London: Gifford Monogr.

- Finch, J. 2000, Church Monuments in Norfolk before 1850: an Archaeology of Commemoration, Brit. Archaeol. Rep. Brit. Ser. 317.

- Fowler, L. & Powers, N. 2012, Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men: Excavations in the 19th-Century Burial Ground of the London Hospital, 2006, London: Museum of London Archaeology, MOLA Monogr. 62.

- Friends of Christ Church Spitalfields 2003, Christ Church, Spitalfields: Investigations of the Burial Crypt 1984–1986 [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service

- Friends of Christ Church Spitalfields 2015, Monuments catalogue, <https://www.christchurchspitalfields.org/CAT_ListCategories.aspx?cid=397&pid=0&category=Monuments-catalogue> [accessed 19 September 2018].

- Fritz, P.S. 1994–5, ‘The undertaking trade in England: its origins and early development, 1660–1830’, Eighteenth-Century Studies. 28, 241–53.

- Gentle, R. & Feild, R. 1975, English Domestic Brass 1680–1810 and the History of its Origins, London: Paul Elek.

- Greenwood, J. 1883, ‘Buried by the Parish’, Mysteries of Modern London, London: Diprose and Bateman, 70–6. <http://www.victorianlondon.org/publications4/mysteries-10.htm> [accessed 24 October 2015].

- Hallam, E. & Hockey, J. 2001. Death, Memory and Material Culture, Oxford: Berg.

- Heinrich, A.R. 2014, ‘Cherubs or putti? Gravemarkers demonstrating conspicuous consumption and the Rococo fashion in the eighteenth century’, Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 18, 37–64.

- Henderson, M., Miles, A. & Walker, D. 2013, ‘He being dead yet speaketh’: Excavations at Three Post-Medieval Burial Grounds in Tower Hamlets, East London, 2004–10, London: Museum of London Archaeology, MOLA Monogr. 64.

- Henderson, M., Miles, A. & Walker, D. 2015, St Marylebone’s Paddington Street North Burial Ground: Excavations at Paddington Street, London W1, 2012–13, London: Museum of London Archaeology, MOLA Stud. Ser. 34.

- Hotz, M.E. 2001, ‘Down among the dead: Edwin Chadwick’s burial reform discourse in mid-nineteenth-century England’, Vic. Lit. Cult. 29:1, 21–38.

- Houlbrooke, R. 1999, ‘The age of decency: 1660–1760’, in Jupp & Gittings 1999, 174–201.

- Howarth, G. 1997, ‘Professionalising the funeral industry in England 1700–1960’, in Jupp & Howarth 1997, 120–34.

- Jalland, P. 1996, Death in the Victorian Family, Oxford: University Press.

- Jupp, P. & Gittings, C. (eds) 1999, Death in England: an Illustrated History, Manchester: University Press.

- Jupp, P. & Howarth, G. (eds) 1997, The Changing Face of Death: Historical Accounts of Death and Disposal, Basingstoke and London: Macmillan Press.

- King, C. & Sayer, D. (eds) 2001, The Archaeology of Post-Medieval Religion, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, Soc. Post-Medieval Archaeol. Monogr.

- Litten, J. 1991, The English Way of Death: The Common Funeral since 1450, London: Robert Hale.

- Litten, J. 1998, ‘The English funeral 1700–1850’, in Cox 1998, 3–16.

- Litten, J.W.S. 2004–10, Symbolism on Monuments, <http://www.churchmonumentssociety.org/Symbolism_on_Monuments.html> [accessed 24 October 2015].

- Mahoney-Swales, D., O’Neill, R. & Willmott, H. 2011, ‘The hidden material culture of death: coffins and grave goods in late 18th- and early 19th-century Sheffield’, in King & Sayer 2011, 215–31.

- Miles, A. 2008, ‘Coffins’, in Cowie, Bekvalac & Kausmally 2008, 31–5.

- Miles, A. 2011a, ‘Coffins and coffin fittings’, in Emery & Wooldridge 2011, 166–78.

- Miles, A. 2011b, ‘Coffin furniture catalogue’, in Emery & Wooldridge 2011, CD appendix 2.

- Miles, A., Powers, N. & Wroe-Brown, R. 2008, St Marylebone Church and Burial Ground in the 18th and 19th Centuries: Excavations at St Marylebone School, 1992 and 2004–6, London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, MoLAS Monogr. 46.

- Miles, A., Ritchie, S. & Wroe-Brown, R. 2015, ‘Recording and cataloguing the University of Reading collection of coffin plates from St Marylebone Church, Westminster’, London Archaeologist 14:5, 128–30.

- Misson, H. 1719, M. Misson’s memoirs and observations in his travels over England. With some account of Scotland and Ireland. Dispos’d in alphabetical order. Written originally in French, and translated by Mr. Ozell, London: D. Browne.

- Morley, J. 1971, Death, Heaven and the Victorians, London: Studio Vista.

- Mytum, H. 2000, Recording and Analysing Graveyards, York: Counc. Brit. Archaeol. in assoc. with Engl. Herit.

- Mytum, H. 2002, ‘A comparison of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Anglican and Nonconformist memorials in North Pembrokeshire’, Archaeol. J. 159, 194–241.

- Mytum, H.C. 2004, Mortuary Monuments and Burial Ground of the Historic Period, Boston: Springer.

- Mytum, H. 2006, ‘Popular attitudes to memory, the body, and social identity: the rise of external commemoration in Britain, Ireland and New England’, Post-Medieval Archaeol. 40:1, 96–110.

- Mytum, H. 2015, ‘Artifacts of mortuary practice: industrialization, choice and the individual’, in Brooks 2015, 274–304.

- Mytum, H. 2017, ‘Mortuary culture’, in Richardson, Hamling & Gaimster 2017, 158–71.

- Mytum, H. 2018, ‘Explaining stylistic change in mortuary material culture: the dynamic of power relations between the bereaved and the undertaker’, in Mytum & Burgess 2018, 75–93.

- Mytum, H. & Burgess, L. (eds) 2018, Death Across the Oceans: American, British and Colonial Historic Burial Archaeology, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

- Plume, S. C. 1910, Coffins and Coffin Making, London: Undertakers’ Journal.

- Pugin, A.W. 1844, Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament and Costume, Compiled from Ancient Authorities and Examples, London: Henry G. Bahn.

- Reeve, J. & Adams, M. 1993, The Spitalfields Project Volume 1, the Archaeology: Across the Styx, Counc. Brit. Archaeol. Res. Rep. 85.

- Rendall, H. 2011, ‘Memorial stones and tomb fragments’, in Emery & Wooldridge 2011, CD Appendix 1.

- Renshaw, L. & Powers, N. 2016, ‘The archaeology of post-medieval death and burial’, Post-Medieval Archaeol. 50:1, 159–77.

- Richardson, C., Hamling, T. & Gaimster, D. (eds). 2017, The Routledge Handbook of Material Culture in Early Modern Europe, Farnham: Routledge.

- Richmond, M. 1999, ‘Archaeologia Victoriana: the archaeology of the Victorian funeral’, in Downes & Pollard 1999, 145–58.

- Rugg, J. 1999, ‘From reason to regulation: 1760–1850’, in Jupp & Gittings 1999, 202–29.

- Sayer, D. & Symonds, J. 2004, ‘Lost congregations: the crisis facing later post-medieval urban burial grounds’, Church Archaeol. 5–6, 55–61.

- Tarlow, S. 1999, Bereavement and Commemoration: an Archaeology of Mortality, Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tarlow, S. (ed.) 2015, The Archaeology of Death in Post-Medieval Europe, Berlin: De Gruyter Open <http://www.degruyter.com/view/product/458680> [accessed 23 October 2015].

- Tarlow, S. & West, S. (eds) 1999, The Familiar Past? Archaeologies of Later Historical Britain, London: Routledge.

- Turner, J. 1838, Burial Fees of the Principal Churches, Chapels, and New Burial-grounds, in London and its Environs, London: Cunningham and Salmon.

- University of Leicester Graveyards Group 2012, ‘Frail memories: is the commemorated population representative of the buried population?’, Post-Medieval Archaeol. 46:1, 166–95.

- Willsher, B. 1985, Understanding Scottish Graveyards: an Interpretive Approach, Edinburgh: Canongate Books.