SUMMARY

The modernization of fortifications during the early modern period and their spatial development had a profound impact on the structure of the city and the everyday lives of its inhabitants. Using the example of the city of Wrocław/Breslau in Silesia (present-day Poland), we discuss the changes that occurred in the perception of fortifications between the Habsburg period, when the city authorities were responsible for their development, and the Prussian period, when the development of fortifications was a subject to central authority. Drawing on written, iconographic, and archaeological sources, we obtain a comprehensive picture of the process of city prestige-building through investments in fortifications. Additionally, we observe fortifications as a factor that negatively influences spatial development and diminishes the quality of life in the city. Preserved documents allow us to trace the losses incurred by residents and institutions due to the expansion of fortifications.

INTRODUCTION

In addition to their obvious military function, fortifications also had a social and symbolic meaning (Creighton and Higham Citation2005, 165–173). City walls and gates appeared in coats of arms of cities and on their seals and their role as an emblem of 'urbanity’ has continued into the modern period, where they come to the fore in views of cities (Braun, Hogenberg, and Koolhaas Citation2015, among others). However, urban fortifications did not only protect the inhabitants, but also limited the possibility of urban development. The modernisation of fortifications affected the buildings that already existed, and this in turn affected the burghers and their professional activities, production, trade and other ways in which they made money. It also affected the private sphere by defining where and how they lived, entertained themselves and even what happened to them after death. It thus impacted the quality of life in the city.

The aim of this text is to demonstrate how the construction and existence of fortifications affected the use of space of the city and the well-being of the townspeople. We are interested in presenting the transition of the fortifications, which were the pride of the city at the dawn of the modern period, to the role of a factor limiting and lowering the value of space. The city of Wrocław [ger. Breslau], due to its long history of urban fortifications development, is an excellent case study for considering the impact of fortifications on city space.

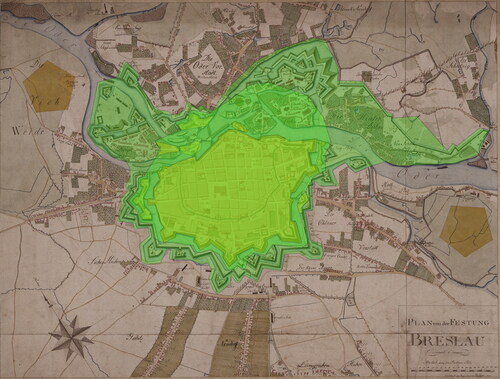

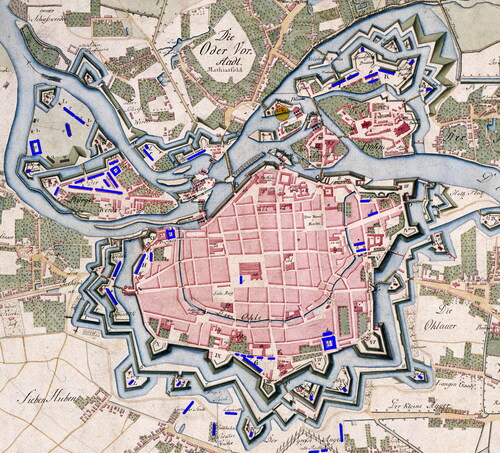

Wrocław was a large and significant urban centre, the provincial capital of Silesia—an important and rich region located between Bohemia, the Polish—Lithuanian Commonwealth and Brandenburg (; Mühle Citation2015). Here, as in Prague, Nuremberg, Dresden, Berlin or Vienna, the spatial development of the city, and the associated interests of its inhabitants, were constantly influenced by the limiting factor of the presence of fortifications. With the development of the fortifications, the reserve of land for development was not growing and the new fortifications perpetuated the city boundary set in the thirteenth century. Bastion fortifications began to be built in the first decades of the sixteenth century, the first example of which is the Scheren Bastion, from 1544. This date will be for us the conventional beginning of the period under consideration. Another time caesura was in 1741, when Wrocław came under Prussian rule during the First Silesian War (Ziątkowski Citation2001). Until 1741, it was the burghers, or more specifically the municipal government, who decided where the new defensive structures were built. What areas they would occupy was determined as much by the fortification needs as by the possibilities of the city budget and the interests of the inhabitants. In 1741, the city of Wrocław lost its self-government and, consequently, its influence on the development of fortifications. From then on, the construction of new defensive works resulted solely from the military needs of the Prussian authorities. The upper limit of our interest is 1807, when, after the fortress was captured by Napoleonic troops, the fortifications were dismantled and Wrocław became an open city.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

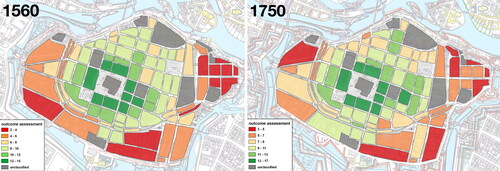

Historical sources and material remains of modern fortifications discovered in archaeological research undertaken in the city since the mid-twentieth century will form the basis for the considerations undertaken. Research documentation is stored in the Archives of the Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków in Wrocław and was only partially published. An important source was archival documents concerning the development of fortifications in the Prussian period deposited in the State Archives: the Archiwum Państwowe in Wrocław and in the Geheimes Staatsarchiv in Berlin. Iconographic and cartographic materials dating from the 16th to 19th centuries also provided important information. The georeferencing of maps and plans made it possible to identify the relics discovered as specific defensive works. The spatial analyses used the original method of valorisation of the city space, developed in a GIS environment allowing the visualisation oftransformations that took place in urban development during this period ().

DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN FORTIFICATION OF WROCŁAW

MEDIEVAL HERITAGE

At the dawn of the modern period, Wrocław was a self-governing city with a strong political position. The city had a system of medieval fortifications erected in the 13th–14th centuries and modernised in the fifteenth century, mainly near the city gates (Bimler Citation1940, 9; Konczewski, Mruczek, and Piekalski Citation2010). This system became the basis for the development of modern fortifications (Piekalski Citation2007). In the 1480s, the expansion of the perimeter of the fortifications began with aiming to adapt them for defence using firearms. The construction of a protruding round bastion near the flow of the Oława river into the city moat initiated the construction of a zwinger and a second defensive wall (so called round-bastion wall). This ambitious investment, financed by the city budget, was interrupted and abandoned during the economic crisis at the beginning of the sixteenth century (Stein Citation1995). At that time, the space inside the city walls was not entirely filled with buildings. Barthel Weiner’s plan of 1562. – Contrafactur der Stadt Breslau, shows numerous undeveloped spaces, intended as gardens or public squares ().

HABSBURG MONARCHY PERIOD

The incorporation of Silesia into the Habsburg monarchy began a period of more than two hundred years in the city’s history in which the supreme authorities sought to limit the position of the city council. The reluctance of the authorities in Vienna increased further during the Counter-Reformation period, in view of the fact that the majority of the Council was Protestant (Gierowski Citation1958, 371–372).

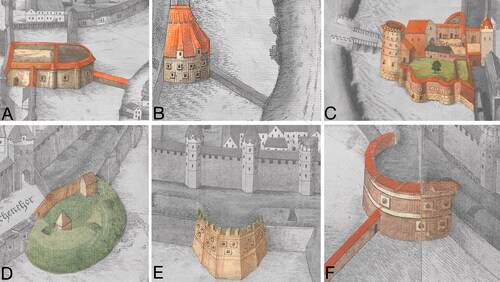

The trepidation before the Turkish army after the Battle of Mohács in 1526, provided an excuse to continue the expansion of the city’s defence system, for which the fortifications became a means of demonstrating political power. By the end of the 1540s, the second perimeter of the outer ramparts had been expanded, supplying it with a series of defensive works in the form of round bastions—roundels (ger. Bastei/Rondell)—low towers with a semicircular or polygonal outline. works of this type had been erected (Bimler Citation1940, 22–6). They varied in form and construction from timber and earthwork, through earthwork on a brick foundation to complete masonry ().

FIG. 3 Examples of different types of round bastions erected in Wrocław between 1486 and 1544, fragments of Contrafactur der Stadt Breslau 1562, by Barthel Weiner. (BUWr ref. 2318, PDM 1.0 DEED).

Surrounding the town with a second ring of walls did not complete the modernisation process. The new defensive systems, in the form of polygonal bastions, which had begun to be popular in Italy, appeared soon in Europe north of the Alps, primarily through imperial investments, in cities such as Vienna, Ghent and Antwerp (Duffy Citation1995) The construction of the Scheren Bastion, initiated in the 1540s, testifies to the rapid adoption of the new models in Wrocław (). The unusual form of the bastion, which has a split saillant, indicates that the design was adapted to local conditions. The construction was the responsibility of the city architect Lorenz Gunter, who visited the fortifications of German cities to improve his competence. His stay in Hanau is documented (Bimler Citation1934, Citation1940, 28). Nor is it a coincidence that Italian names appeared among the members of the Wrocław building guilds at this time.

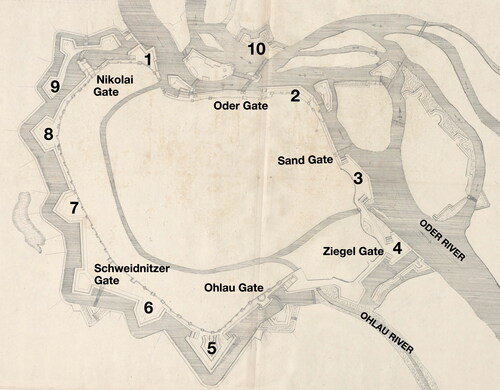

FIG. 4 Main city gates, bastions and defensive works in Wrocław in the seventeenth century, based on the plan by Albrecht von Säbisch circa 1650: 1—Scheren Bastion, 2—Burg Bastion, 3—Sand Bastion, 4—Ziegel Bastion, 5—Taschen Bastion, 6—Zwinger Bastion, 7—Graupen Bastion, 8—Hund Bastion, 9—Nikolai Crownwork, 10—Oder Crownwork (BUWr ref. 2494-IV.B, PDM 1.0 DEED).

Another investment demonstrably linked to an Italian architect was the extension of the Ohlau Gate fortifications in 1576. The city council tried to recruit a recognised architect, Bernard Niuron (Neuroni), who came from a colony of Italian builders employed to service the princely investments in nearby city of Brzeg (Wernicke Citation1881; Michael Citation2006, 30–31). The next phase of urban investment was the construction of fortifications on the side of the Oder River (1581–1586). For their construction, the Dutch-born builder Hans Munting from Groningen was employed. The greatest increase in fortification activities is connected with the activity of another architect, Hans Schneider von Lindau (from Lindau am Bodensee), who had previously worked on the fortifications of Gdańsk (ger. Danzig) and the Wisłoujście Fortress (ger. Weichselmünde) (Bimler Citation1934; lewicka-Cempa Citation1980). Initially, he was a consultant supporting the city builder Friedrich Gross in continuing work on the fortifications along the Oder (Sand Bastion, Sand Gate). Between 1591 and 1606, already as city builder, he was responsible for the construction of the bastion fortifications of the eastern part of the city, including the Ziegel, Hiob, Bernhardiner and Taschen Bastions, as well as the reconstruction of the waterwork (water supply building—ger. Wasserkunst) and weirs on the moat.

The continuation of work to create an overall defence system for the city was related to the need to secure the city during the Thirty Years’ War. The next defence works were built in the Dutch manner and were made of earth reinforced with fascine (Mruczek and Stefanowicz Citation2010). Their construction is the achievement of the subsequent urban architects Valentin and Albrecht Saebisch (Frank Citation1995).The completion of the bastion-like circuit of fortifications around the city occurred only in the second half of the seventeenth century, thanks to their efforts. At that time: Zwinger, Graupen and Hund Bastions were built. In addition to replacing the outdated roundels with modern and larger bastions, the gates were fortified with additional works. Ravelins were built in front of the Ohlauer and Schweidnitzer Gates, and in front of the Nikolai Gate an extended Nikolai Crownwork (Nikolai Kronwerk). A second crownwork was built on the north bank of the Oder River—the Oder Crownwork. Some of the islands on the river were also fortified.

PRUSSIAN PERIOD

Breslau, along with most of Silesia, was taken by the Prussians as a result of the First Silesian War. It was not besieged. The city concluded a neutrality agreement with the King of Prussia on 3 January 1741, giving Prussian troops freedom to march through the city. This agreement was broken by the Prussian side on 9 August 1741 and Frederick the Great’s army occupied the city without a fight (Podruczny Citation2011, 111–112). The expansion of Wrocław’s fortifications in the first years after the Prussian occupation of the city was slow. The most important work was the construction of new sections of the covered way and the glacis preceding it. By 1747, two sections of it had been completed—in front of the Nikolai Gate and in front of the Ziegel Gate, where a ravelin with characteristic retired flanks was constructed in addition (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12195, vol. 1, 70–4). In 1754, the fortifications of the Ohlau Gate were transformed—the bastion and ravelin defending it were rebuilt. The section of the moat in front of these works was widened and deepened, and a section of covered way was built in front of them (GStA PK, I HA Rep. 96 No. 616, Bd. G, 62). A year later, similar works were carried out in front of the Schweidnitzer Gate—the moat of the ravelin protecting it was widened and deepened, and a section of a covered way was built in front of it (APWr, AMWr, sygn. 12196, V. 2, 7, 15, 24–5). In 1751, a new gunpowder magazine was erected in the lunette near the Nicolai Crownwork, (GStA PK, I HA Rep. 96 no. 616, Bd. F, 27).

During the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) Wrocław was besieged three times. In 1757 Habsburg troops captured the city after a brief (23–25 November) siege, which followed a major Prussian-Austrian battle fought on 22 November in the south-western suburbs. Maria Theresa’s troops immediately set about reinforcing the fortifications. Although they held the city for less than a month, they built a long stretch of covered way between the Nikolai Gate and the Schweidnitzer Gate (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12190, 1–3). On 5 December 1757, another, even bigger battle took place a dozen or so kilometres from Wrocław, at Lutynia (ger. Leuthen), which resulted in the defeat of the Austrian army and another, this time Prussian siege of Wrocław (10–19 December). As a result, the fortress once again fell into Prussian hands (Podruczny Citation2011,112–123).

In 1758, after the recapture of Wrocław by the Prussians, another section of the covered way was completed, between Schweidnitzer and Ohlau Gates (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12190, 10–43). In parallel, repair work was carried out on the reconstruction of the destroyed section of the Taschen Bastion and the adjacent curtain, which began in spring of 1758 (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12197, 1–5).

For the last time during this conflict, Wrocław was besieged in 1760. It was attacked, unsuccessfully, by Habsburg troops (Podruczny Citation2011,123–127).

All this war activity around Wrocław was a strong impetus for the modernisation of fortifications. Another expansion of the fortress began in mid-1762. This time the work was carried out on a much larger scale, the land taken for the new fortifications being about 34 hectares in area. As part of the new action, a 3.5 km long envelope (an additional defensive rampart protruding from the main moat, preceded by its own narrower moat), a new defensive structure in front of the Ziegel Gate and fortifications were built on Burgerwerder, in the form of a large hornwork preceded by a water moat. Work on these defence works was completed in 1765 (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12197, 36-8, ref. 12190,55-6, 64, 76-78, 103-4,117). In 1768 the missing section of the main rampart between the Nikolai Gate and the Scheren Bastion was erected (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12197, 44-5). Another modernisation of the fortress took place in the 1770s. It involved the reinforcement of the envelope with new defensive works, the construction of further facilities on Burgerwerder and the erection of fortifications on the north bank of the Oder River—in the Oder Suburb and around Dominsel.

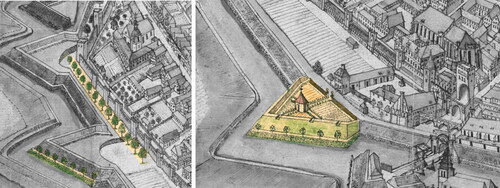

Work began with the construction of works reinforcing the envelope of the city fortifications, and was carried out from 1771 until the middle of the decade. In 1772, the erection of Springstern began, and the construction of this fortification complex continued until 1777. At the same time, new works were constructed on Burgerwerder and those on the northern bank of the Oder (). In front of the Oder Crownwork a new envelope and the so-called Silber Sconce were constructed between 1770 and 1774 (Menzel Citation1807, 816; APWr, AMWr, 12191; 12194).

FIG. 5 Area of Burgerwerder. Development of fortification in 1562, 1750 and 1802. Fragments of plan of Weiner, Wernher (BUWr ref. 2318; ref. R 551, PDM 1.0 DEED) and Poblotzky (GStA SPK XI. HA, ref. E 72090, PDM 1.0 DEED).

In the meantime, the newly created fortifications began to be filled in with military buildings—between 1773 and 1776, Frederick’s Gate was erected within Springstern, together with a casemate for the crew; while between 1780 and 1783, a second casemate was built between the Bastions of Hundsfeld and Neudorf (Luchs Citation1866, 11; Kieseritzky Citation1903, 12).

The fortifications of Wrocław were completed in the suburban village of Szczytniki. First, in 1776, a sluice separating the waters of the old Oder riverbed from the main riverbed and a redoubt shielding it was erected near the Pass Brücke (now the Zwierzyniecki Bridge). In 1777, a casemate was to be built in this redoubt (GStA SPK, I HA Rep. 96 B, Bd. 75, 911, Luchs Citation1866, 11). Finishing work on these structures continued until 1781 (GStA SPK, I HA Rep. 96 B, Bd. 79, 723, 848, Bd. 81, 815). The last stage in the expansion of the fortifications of this site and at the same time of the fortifications of Wrocław was the construction of the so-called Communication on Hinterdom. This defensive structure had the form of a long rampart, tick-like in outline, preceded by a water moat. It ran from the Dom Ravelin up to a redoubt with a casemate at the Pass Brücke. It was built between 1782 and 1784 (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12192, 1-7).

INVESTMENTS IN FORTIFICATION AS A WAY OF BUILDING A TOWN'S PRESTIGE

The construction of fortifications in the early modern period was of crucial importance for the city. It accounted not only for its security, but above all for its political position among the cities of the Habsburg Monarchy. The impressive size and modernity of the fortifications, together with the city’s right to have its own military garrison (ius preasidi), meant that the municipal government was reckoned with (Igert Citation1939, 22).

The rapid appearance of modern bastion fortifications, despite the absence of any real threat of war for the city, should be considered as an element of prestige building process by following innovations and world trends. Archaeological research on the first one in Wrocław—the Scheren Bastion—confirms the high technological level of the workshop erecting this structure (Kmiecik et al. Citation2021). Subsequent realisations, such as the Ohlau Gate associated with its piatta forma and the New Gate at the Imperial Castle, refer to models tested in Italy and the Netherlands.

Expertise and the ability to design and build fortifications of the Italian and later Dutch type were a prized commodity in the 16th-17th centuries. The city authorities’ prestige-building efforts involved seeking out architects with proven skills. The few masters could count on many offers of cooperation, and cities employing outstanding builders could grant permission to hire them. The city council of Wrocław, consulting on the work and looking for an architect, corresponded with Gdańsk, Kostrzyn (Küstrin) and Dresden (Lewicka-Cempa Citation1980, 39). The correspondence preceding the start of cooperation with Bernard Niuron or Hans Schneider von Lindau has been preserved (Bimler Citation1934). The importance of the latter architect to the city authorities is evidenced by the value of the contract. Hans Schneider’s salary was more than double that paid to previous city builders and amounted to 525 marks (Bimler Citation1934, 120). His experience attested by his achievements as a builder in Elbląg (Elbing) and Gdańsk must have impressed the Wrocław town authorities, although his involvement in the construction of fortifications is not documented, apart from his cooperation in the construction of the fort at Wisłoujście. The architect’s fame, however, extended far beyond Silesia, and the city authorities had to compete with commissions from Prague and Vienna as well as offers of cooperation from local rulers (Śledzik-Kamiński Citation2021).

The construction of the fortifications by Hans Schneider von Lindau involved considerable expense. Not only was the size and consumption of building materials of these defensive works impressive, surpassing all previous and subsequent investments, the attention to detail, such as the stone decorative elements, is also noteworthy. The characteristic star or floral ornament appears not only in the portals of the city gates, but is also an element of the casing of the gun emplacements, which is quite unusual and even extravagant. Numerous fragments of architectural details were found during archaeological investigations and inventoried (Chorowska, Rajski, and Serafin Citation2012) (). However, the need for representation was not at odds with the principles of elementary thriftiness, demonstrated by the use of demolition bricks and elements of older defensive works in the construction (Caban Citation2015).

FIG. 6 Remains of embrasures with decorative details, designed by Hans Schneider von Lindau in the Ziegel Bastion (by M. Legut-Pintal).

Central European cities of the late 16th and early 17th centuries also took care to train native master builders, whose loyalty to their sponsors compensated for their lesser experience. This is evidenced by travels financed through the city budget for master builders to visit the latest fortification investments (Dybaś Citation1994). The erudition acquired in this way and the broad horizons of successive city builders are evidenced by the legacy of archival material preserved (BUWr collection ref. R 943 b). Collections of drawings concerning fortifications testify to their familiarity with the achievements of the Dutch school, as well as their ability to adapt solutions to local conditions. The artistic achievements of the Sabisch family were appreciated not only in Silesia, but also in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

After the Prussian takeover of Wrocław, much had changed in this respect. Without exception, the engineers who designed and built the fortifications were officers in the Prussian army, not city officials. What is more, for the most part they were relatively unknown. Wrocław was only briefly home to a well-known fortification designer, Cornelius Walrave, who famously rebuilt fortresses in Mainz, Magdeburg, Szczecin (ger. Stettin), Nysa (ger. Neisse), Kłodzko (ger. Glatz), and also built the first fort-fortress in history—the fortress in Świdnica (ger. Schweidnitz) (Podruczny Citation2024, 319–323). Unfortunately, his contribution to the rebuilding of the Wrocław fortress was small, amounting to the design of a small work in front of the Ziegel Gate. The other engineers who worked on the modernisation of the fortifications here—Captain Giese, Major Balbi or Major Haab—were relatively unknown. Nonetheless, the solutions introduced here during the Prussian modernisations had some influence on the development of European fortifications, especially the artillery casemates, which were erected in the 1770s in two works—the Graupen Bastion and the Nikolai Gate Bastion. Not only were these structures among the first casemates of their kind erected in Prussian fortresses, but they were also noted by one foreign observer. The French politician and writer, Honore-Gabriel de Riquetti de Mirabeau, in the fourth volume of his description of the Prussian monarchy under Frederick II, published in 1788, devotes a large section of his reflections on Prussian fortresses to the Prussian artillery casemates, which in his opinion were the first to be erected in Wrocław. Interestingly, he compares the solutions applied in Wrocław by the Prussians with the ideas of Marc Rene de Montalembert, the most important fortification theorist of the late eighteenth century, and evaluates the Wrocław examples better (de Mirabeau Citation1795, 425).

However, it was also during this period that a well-known architect—Carl Gotthard Langhans, author of the Frederick Gate erected in the Sprinstern complex, and the Barbara casemates—was among those designing defensive works. For our considerations, the first building, specifically its sculptural decoration, is crucial. Symptomatic is the absence of motifs referring to local tradition in its iconography—the rich panoply decoration of the gate emphasises the military function of the building, and the eagle placed in the centre of the tympanum, as a heraldic animal of the Prussian state, refers to the new sovereign, which was the Prussian king (GStA SPK XI. HA, D 70140). The same is true of two other military buildings designed by Langhans in Wrocław—in the city’s guardhouse and the monumental artillery barracks on Burgerwerder. It should be emphasised, however, that in the works of Carl Gotthard Langhans one can see a continuation of a trend that was present in Wrocław during the Habsburg period—the employment of quality architects to build buildings serving the military. Langhans is considered to be the architect who introduced classicism to Central Europe, and his most famous building, the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, is still one of the icons of Central European architecture.

TRANSFORMATIONS OF URBAN SPACE CAUSED BY THE CONSTRUCTION OF FORTIFICATIONS

Until the mid-sixteenth century, the modernisation of the defensive works did not significantly affect the space of the medieval-formed city. There was still a large reserve of building land within the city walls, which was used as gardens. The number of plots, amounting to approximately 2,100 inside the city walls at the end of the Middle Ages, remained relatively constant until the end of the modern period. However, the density and height of buildings increased systematically, with the result that the modern city was virtually devoid of green space and recreational areas were located outside the walls.

CONSTRUCTION OF BASTIONS

Changes in land use, however, occurred during the construction of the bastion fortifications. The construction of fortifications in the Oder belt restricted the inhabitants’ access to the river. The warehouses and mills located there were removed. During the construction of the Sand Gate and the Sand Bastion, a bathhouse, two inns and houses were demolished in 1589 in order to build a new city gate. In return offering space to rebuild them in other favourable locations (Pol Citation1823, 154). The timber yard was relocated and it was also decided to demolish the buildings of the Holy Spirit Hospital (Pol Citation1823, 157). As a result of the construction of the Ziegel Bastion, it was decided to close the city brickyard located with it, and a new timber yard was established in its place.

However, the expansion of the fortifications and above all the widening of the moat and the need to clear the foreground resulted in changes to the landscape of the suburbs. The suburbs consisted mainly of urban pastures and arable fields, but also cemeteries, a shooting range, gardens and homesteaders’ houses. Elements of permanent buildings that could provide shelter for enemy troops were removed. This argument had earlier become a pretext for the demolition of the large monastery complex on Ołbin in 1529 (Żurek Citation1997, 7). The demolition material was used in the construction of numerous urban developments, including the construction of new fortifications—sculptural elements were found, among others, on the site of the hospital adjacent to the fortifications and in the arsenal (Kmiecik and Szwed Citation2018).

However, the ban on foreground buildings ceased to be observed during the period of prolonged peace. At the end of the sixteenth century, gardens of a representative nature belonging to wealthy bourgeoisie and Lusthaus buildings of permanent construction could be seen there (Brzezowski and Jagiełło Citation2014). It was not until the events of the Thirty Years’ War that the foreground was permanently cleared, which was later entered by the expanded fortifications of the town. The construction of the crownwork and ravelins moved the suburbs away from the city gates by almost 200 m.

PRUSSIAN FORTRESS

The Prussian expansion of the Wrocław fortress had a very strong impact on the urban space. The fortifications erected by the Prussians after 1741 covered an area of about 94 ha, almost double the area of the fortress to date (about 55 ha) and only slightly less than the urban development within the walls (up to 107 ha). Furthermore, when the expansion was completed, the fortress-defences, the connecting ramparts and the numerous moats together had a larger area than the urban buildings (149 ha compared to 107 ha) (). Before 1740, the fortress was an addition to the town, half a century later it was the other way around. All this newly fortified land had previously been in civilian use, which meant that the burghers lost a lot of land. A large group of property owners suffered damage as a result. Among those affected were both private individuals and institutions—hospitals, monasteries, and the town itself. Private individuals ranged from the nobility (Prince Hohenlohe), local government officials (Councillors Soya and Müller) to ordinary burghers. The military authorities spared no-one, when planning fortifications they took defence into account rather than anyone’s interests. Even people high up in the local hierarchy were not protected from the requisitioning of property belonging to them for the construction of fortifications. An example of this was the town councillor Georg Friedrich Soja, who had been mayor of Wrocław since 1777. In 1771 he lost his house on Hinterdom, which had been bought only five years earlier and newly renovated, due to the construction of the Springstern fortifications. His property was worth a total of 3240 thalers and was taken in its entirety (APWr, AMW, ref. 12194, 78–19, 104–111; Notitz Citation1770, 148; Markgraf and Frenzel Citation1882, 130). Many properties were lost by the magistrate itself—the timber yard in front of the Ziegel Gate, the area of the Swine Pond, the shooting range in the Oder Suburb, the cemetery area at the Salvatore Church, the hospital buildings in the area of the Barbara Cemetery and the houses in the Nikolai Gate. Church institutions also suffered significant losses. The largest loss was suffered by the Poor Clares convent, which had part of its manor of as much as 16 hectares, worth 5338 thalers, taken away from it for the construction of the Springstern fortifications(APWr, AMW, ref. 12.194, 104–111). The other owners lost less—the Holy Sepulchre Children’s Hospital—a meadow on Burgerwerder worth 1560 thalers, the Cathedral Chapter—two outbuildings worth 337 thalers, the St Vincent Monastery—a fragment of a harbour worth 73 thalers and the St Giles Altar Foundation—a fragment of a field on the outskirts of Schweidnitz suburb worth 196 thalers (APWr, AMW, ref. 12.191, 118–119; ref. 12.194, 104–111). However, most of the properties requisitioned were lost by ordinary burghers who had their houses or workplaces there. The most frequently mentioned are lost fields, orchards and gardens, both those at home and those producing food for sale. An example of the latter category are the property owners from the vicinity of the village of Siedem Łanów (ger. Sieben Huben), who lost their gardens and who were described in the sources as 'vegetable growers’ (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12191, 95–123). Significantly, compensation was paid not only for lost land, but also for fruit trees and lost crops. Usually, these were sowings, although the compensation of 10 thalers paid in 1743 to Henryk Mithmann for lost asparagus growing in his field near the Nikolai Gate stands out (APWr, AMWr, sygn. 12222, 19). In the Ohlau Suburb, among the property owners harmed by the construction of fortifications, alcohol producers were particularly numerous, and the sources mention as many as seven (APWr, AMWr, sygn. 12190, 120–1). In six cases they are described as producers of brandy (Weinbrenner) in one as a distiller (Destilateur). Inns were another element of infrastructure typical of suburban areas—sources mention 3 such facilities. One of them called Walfisch (Whale) in the suburb of Nikolai, was removed in 1763 as part of the construction of the enweloppe. Second was an inn on the site of the shooting range, and another was located near Springstern (APWr, AMW, ref. 12190, 8–9, 104–111; ref. 12193, 6–8). However, the vast majority of buildings that were removed in whole or in part in connection with the construction of the fortifications were residential houses. This means not only a loss of residential buildings, but also a decrease in the profits of the owners of these buildings, as many times these were not the inhabited houses of their owners, but also buildings generating rental income.

St SALVATOR CEMETERY

An area worth paying more attention to is the cemetery area next to the Salvator church () The matter of the construction of fortifications at this location dragged on for more than 15 years and is well documented in both written and cartographic sources, besides which the remains of the fortifications built there have been archaeologically examined twice (Wojcieszak Citation2015, 19; Szwed, Dąbrowski, and Kmiecik Citation2023, 4–15). The first time the cemetery was covered by fortifications was in 1755. At that time, the moat of the Schweidnitz Ravelin was widened, at the expense of the church area, and the cemetery was surrounded by a glacis. The burghers protested against the military decisions, until it was announced that it would still be possible to bury the dead in the glacis (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12196, 15). In 1762, there were further plans to incorporate the cemetery within the fortifications. The new outer moat in front of the town envelope was to cut through the cemetery and for this reason there were plans to remove the mortuary and the belfry house, and of course to liquidate part of the cemetery. As in 1755, the burghers protested and requested that the moat be run beside, rather than through, the cemetery. The complaint was successful; the new work bypassed the cemetery. (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12197, 36–38, 64–65).

FIG. 8 Developement of the fortification before the Schweidnitzer Gate in 1562, 1750 and 1802. Fragments of plan of Weiner, Wernher (BUWr ref. 2318; ref. R 551, PDM 1.0 DEED) and Poblotzky (GStA SPK XI. HA, ref. E 72090, PDM 1.0 DEED). Area of the St. Salvator cemetery—blue.

Despite the efforts of the municipal authorities, the cemetery next to the Salvator church was eventually included within the fortifications. In September 1770, another project for the expansion of the fortress was drawn up, which, among other things, included fortifications around this cemetery (GStA SPK, I HA Rep. 96 B, V. 71, 473). In 1771, as a result of this project, the buildings surrounding the church were finally demolished. The church survived but burials were prohibited. The sources are silent about the formal liquidation of the cemetery; correspondence between civil and military authorities focuses on maintaining the possibility of further burials (APWr, AMW, ref. 12197, 49–50). This was made possible by the designation of a site for a new cemetery, which was located near the foreground of the new fortifications, by the road between Schweidnitz and Ohlau Gate, opposite Werner’s barracks. (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12194, 92, ref. 12197, 48–50, GStA SPK, I HA rep. 96B, V. 72, 188). Written sources do not mention issues related to burials left in the closed cemetery, which clearly indicates the indifference of the city authorities to their fate. This is confirmed by the results of archaeological research carried out on the former cemetery in 2006–7 and in 2022 (Wojcieszak Citation2015, 19; Szwed, Dąbrowski, Kmiecik 2023, 4–15). The first, carried out as part of the expansion of DH Renoma, led to the discovery of relics of around 1,200 burials associated with the church cemetery, numerous ossuaries and also relics of fortifications. As many as 37 of the burials found had been cut by the excavation for the construction of the moat—some parts of the skeletons that did not interfere with the excavation were left in situ, while the rest were removed. Similar finds were uncovered in 2022, during work carried out by Robert Szwed and Piotr Kmiecik. As a result of these, an 11-metre-long fragment of the moat was found. It consisted of sections of a masonry buttress and counterscarp, preserved at about 100–120 cm from the bottom of the moat, a short fragment of the buttress of the right front and a relic of a masonry object from inside the work, probably a gunpowder magazine. Burials associated with the cemetery at the Salvator church, were located under the relics of the presumed gunpowder magazine (). Both the ossuaries from removed bones, as well partially destroyed and intact burials were also found, analogically as during the 2006 survey.

CHANGES ON THE FOREGROUND

It should be emphasised that the expansion of Wrocław’s fortifications in the modern period was associated with constant pressure on the properties lying in the foreground, and in this respect the Prussian period was characterised not by a qualitative but a quantitative change. This was due to the continuous development of bastion fortifications and the ways in which they were conquered, resulting in the need to build defensive works further and further out into the foreground. As a result, properties spared in one period of fortification development were taken for fortifications in subsequent periods. A prime example of this was the area in front of the Ziegel Bastion. Its construction in 1589 resulted in the removal of the town’s brickworks, while a timber yard was established in its foreground, moved there from the previous location occupied by the construction of the fortifications. The same square was occupied in part for the expanded fortifications even before 1747, when a short section of counterguard was built there, then in 1747 and then again, in the 1770s ().

MILITARY BUILDINGS

While in the case of the construction of new defensive works, the Prussians only greatly intensified the pressure from fortifications on municipal property, a completely new phenomenon was the pressure on civilian property from non-defensive military buildings. Before 1740, this phenomenon did not exist, as there was no garrison in Wrocław, only a small number of troops hired by the magistrate. After the city lost its independence, soldiers began to be permanently quartered here, with as many as 6,000 at its peak (Podruczny Citation2011, 70). This necessitated the construction of an infrastructure for the garrison from scratch. Between 1741 and 1806, Wrocław saw the construction of more than a dozen different types of barracks buildings, a large military grain storehouse and numerous less exposed buildings such as coach houses, drill halls and stables (). These buildings were constructed both inside and outside the city centre, in the former suburbs surrounded by the new fortifications. In the centre, they were built in hitherto poorly urbanised areas, usually in outlying districts, on plots of land located in the immediate vicinity of the fortifications. This was the location of the first barracks complex, the so-called Kreuzhoff barracks, added to the old city wall in the 1740s. Later, only the Barbara barracks were built in this location. The others—Werner, Carmelitan, Balhaus and St Clement’s barracks—were built in areas of less intensive urban development. This does not mean that they were built in completely empty locations. The first two structures were built in an area where there had previously been loose urban buildings adjacent to the powder magazine of the Taschen Bastion, which was blown up during the siege in 1757. St Clement’s and Ballhaus barracks were built on the New Town site—but only the first was built on a site free for development, as it was the site of the ruined St Clement’s Church. The second was built on the site of a functioning municipal building, the Ballhaus, for which the magistrate was to receive compensation, initially of 1300, later reduced to 500 thalers (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12277, 117).

FIG. 11 Location of military buildings with various functions (by G. Podruczny on the plan of GStA SPK XI. HA, ref. E 72090, PDM 1.0 DEED).

The huge barracks complex on Burgerwerder, consisting of 5 residential buildings around a triangular courtyard, a square stable building and a dozen or so ancillary structures was built on a hitherto undeveloped section of the suburb. Little is known about the smaller complex of garrison buildings built at the back of the Springstern fortifications. Two residential casemates (including one housing Frederick’s Gate), a garrison bakery and a wooden storage facility were erected there. Although the buildings of the manor belonging to the Poor Clares Order existed in this area, which had been completely decommissioned. It is not clear whether the garrison buildings were built on the site of the former buildings, as the cartographic sources for this location are too inaccurate.

BARRACKS OF ST BARBARA

Particular attention should be paid to the complex of military buildings established in the cemetery at St Barbara’s Church. In the 1770s, two buildings serving the military were built there—the non-defensive Barracks of St Barbara and the casemates of St Barbara, where soldiers lived during the war (Podruczny Citation2011, 45, 78, 79, 83, 84, 91–3). They were erected on the site of the church cemetery, which was closed in the mid-1770s. The situation was similar to that described in the context of Salvator Church. Although St Barbara’s cemetery was closed along with the other cemeteries within the city walls by a royal decision, this did not happen until 1776 (Menzel Citation1807, 487). Meanwhile the decision to build military buildings on the cemetery at St Barbara’s church had already been taken three years earlier. Moreover, the military development took away not only the burial ground itself, but also other important parts of the town’s infrastructure. The cemetery was at the same time the site of the ancillary buildings of the town’s All Saints’ Hospital—a home for mentally ill and infectious patients (in the words of town officials, 'quite newly built a few years ago’ (APWr, AMW, ref. 12.194, 118), a flat for gravediggers, a bell-ringer and other smaller buildings belonging to the town. All these buildings, as well as the cemetery itself, were removed between 1773 and 1774 (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12194, 118-28, ref. 12277, 283). We do not have exact dates for the construction of the casemates. The barracks were erected between September 1773 and November of the following year. Significantly, both the sources and the archaeological research show the absolute indifference of the municipal civil authorities to the existing burials, identical to the case of the Salvator cemetery described earlier. As a result of the works carried out in the buildings of the former All Saints’ Hospital in 2017, relics of the Barbara casemate were discovered − 11 preserved sections and relics of the foundations of a further 6 sections, and beneath them burials associated with the cemetery at St Barbara’s Church—both preserved in situ and human remains destroyed and displaced during the construction of the casemate (; Kmiecik, Szwed, and Lasota Citation2018, 36). It means that no care was taken to exhume the burials in any form during the construction of these defensive structures. Moreover, the correspondence of the civil authorities focuses exclusively on the issues of compensation for the building of the gravediggers’ house (525 thalers) and the hospital for the mentally and infectiously ill (831 thalers). Interestingly, the issue of compensation for the buildings removed in 1773 dragged on for over 20 years, during which the military authorities of Wrocław refused to pay the magistrate for the demolished buildings (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12194, 130–144).

NON-MILITARY FUNCTIONS OF FORTIFICATIONS

The fortifications were part of the urban space and, in peacetime, may have had various utilitarian functions to serve the citizens. The earthen ramparts housed gardens, hop yards and could also serve as linen bleaching places. In the inter-embankment on the south side of the town from the fifteenth century there was a shooting range of the merchant shooting guild (Neugebauer Citation1876, 69–71). In the seventeenth century, two garden buildings and a colonnade were erected next to it, and the shooting range became not only a place for practice, but also for shows and competitions admired by the audience.

During the Prussian period, the only example of the positive impact of fortifications on urban space was an attempt to establish promenades in the suburbs adjacent to the fortifications (). In the autumn of 1755, the idea of planting linden and chestnut trees along the glacis in the Schweidnitz suburb was born (APWr, AMWr, ref. 12.196; 45, 47, 54, 55). This idea was partly realised in the spring of 1756, when saplings of 500 chestnut and 600 larged-leaved lime trees (Tilia platyphyllos) were planted. A railing separating the glacis from the promenade was more than 2 kilometres long (600 rods). The planned continuation of this green establishment the following year was hindered by the onset of armed conflict and the recently constructed section of the promenade was promptly dismantled due to the city’s siege and the construction of new fortifications (AWr, AMWr, ref. 12196, 45–99).

FORTIFICATIONS AS A BARRIER OF DEVELOPEMENT

The taking of suburban land for the construction of fortifications or the occupation of property inside the city walls for the construction of military infrastructure facilities was the biggest, but not the only, impediment to the urban economy associated with the existence of the fortress. The very presence of the fortifications was also a nuisance and associated with losses. Above all, the suburban buildings in the immediate vicinity of the fortifications were destroyed during sieges. One of the preparations for a siege was the removal of buildings so that a potential attacker had nowhere to hide. Moreover, siege work also led to destruction—not only the trenches dug by the attackers, but also the fire of the fortress artillery fighting the siege army’s positions. However, until the end of the eighteenth century, in peacetime the buildings close to the fortifications were not threatened by anything. Everything, at least in theory, changed in 1797, when a law came into force forbidding the erection of any building within 800 paces (600 metres) of the fortification boundaries, and within 1300 paces (975 metres) only with the permission of the authorities (AWr, AMWr, ref. 12197, 116). This law was a handicap for the inhabitants, as there were almost entire suburbs with hundreds of existing brick houses within the prohibition area. However, as this regulation came into force exactly a decade before the fortress was liquidated by Napoleonic troops, it did not cause many problems for the townspeople.

The limitation of space within the fortifications and the increase in the number of inhabitants led to a decrease in hygiene conditions. In 1790, Johann Wolfgang Goethe wrote: 'We are again in this noisy, dirty, stinking Wrocław, but I hope to be able to escape from here soon…' (Eysymontt and Klimek Citation2007, 3). The liberation of the city from the fortifications resulted in the development of the suburbs and an almost fourfold increase in the built-up area. This was accompanied by a fivefold increase in population. This process gave rise to the development of the modern city (Eysymontt and Klimek Citation2007, 16)

CHANGES TO THE URBAN SPACE CAUSED BY THE CONSTRUCTION OF FORTIFICATIONS

In order to illustrate the transformation of the city space inside the walls, under the influence of the new military developments, we used the author’s method of space valorisation. This method is based on an assessment of the value of residential space, which is carried out on the basis of selected criteria: distance from the centre, the most important roads in the city, the architectural quality of the buildings (number of storeys, construction material, roofing and architectural decorations), the density of development, and the impact of adverse and prestigious neighbourhoods. Each residential quarter receives a point rating in each category. The sum of the ratings determines the final rating. The evaluation results are represented by a colour scale on the plan. Buildings of a military nature were categorised as having an adverse impact on the city space. We have developed assessments for 1550, when the bastion fortifications were just being formed, and for 1750, when the ring of fortifications was completed. A comparison of the images obtained shows a general increase in building density and height, due to the increase in population (). The zone of buildings next to the fortifications is one of the least developed in the sixteenth century. This trend continues into the eighteenth century, despite a general increase in land values. The quarters with the lowest property values are most often located in this zone. Their low valuation is also often influenced by the proximity of other nuisance businesses, which were located on the outskirts of the city. The exceptions are the streets adjacent to the city gates, where the potential benefits of increased traffic compensate for the inconvenience and danger associated with the proximity of fortifications.

CONCLUSION

Although each case of urban development is unique and dependent on a number of factors, case studies make it possible to reveal processes that are universal.

Wrocław is just one of many examples of European cities where there has been significant interference with the urban structure as a result of central government-inspired fortification expansion. Often such interference went even further, what can be seen, for example, in local, Silesian examples. The first is Głogów (ger. Glogau). This city became a strong, bastion-like fortress as a result of the Thirty Years’ War and lost its extensive, densely built-up suburbs, with an area equal to the city itself, and 486 houses, 3 churches, and 4 municipal hospitals (Klawitter Citation1941, 21–22, 31). A similar example was Nysa (ger. Neisse), which until the Thirty Years’ War consisted of two adjacent centres, the Old Town and the New Town. The latter was surrounded by a bastion perimeter during the Thirty Years’ War, resulting in the decline of the former, which was gradually liquidated throughout the second half of the 17th and first half of the 18th centuries, before finally disappearing in the 1740s as a result of the Prussian siege of the city in 1741 and the post-war expansion of the fortifications (Podruczny Citation2023, 21).

Even more urban substance was lost in Freiburg im Breisgau, where, after the French captured the city in 1679, several densely built suburbs were razed to the ground, with numerous burgher houses, 14 churches and chapels, 4 monasteries, and 4 hospitals (Schreiber Citation1858, 209). These were replaced by new regular fortifications designed by Sebastien le Prestre de Vauban. A similar scale of destruction of civilian buildings can be observed in Olomouc, which as a result of the First Silesian War (1740–42) became a key fortress defending the Habsburg state against the Prussian invasion. As a result of the construction of the fortress, the state bought an 800-metre-wide strip around the city walls, with a total area of 139 hectares, for almost half a million florins and erected new fortifications there. Around 350 houses, inhabited by 4,000 people, had previously stood in the area (Kuch-Breburda and Kupka Citation2003, 80). Another example of the same phenomenon is the citadel at Alessandria, erected by the Sardinian-Piedmontese King Victor Amadeus II, after the takeover of the town, previously ruled by the Habsburgs. The citadel was built to the design of the Savoyard engineer Ignazio Bertola between 1707 and 1728. For its construction, the entire town of Borgoglio, with a population of 4,000 inhabitants, was removed (Minola Citation2010, 51–52). The topic of similar cases occurring in various European cities of the period, from Italy to Germany to the Netherlands, unquestionably warrants additional investigation.

From the point of view of the history of urban planning, this was a period when cities adopted the function of defending the territory. The fortifications were not only intended to provide security for the inhabitants, but were also important for the defence of the whole country. Town fortifications have come a long way from being the symbol of a self-governing town, as they were in the Middle Ages, to the function of a modern state fortress. The fortress function was not always beneficial to the city government and its inhabitants. The role of a military base also fell to the city, and being a strategic point of defence increased the danger of attacks, prolonged sieges and bombardments. In many cases, the fortifications became a limiting element in the territorial development of the city, affecting the density of buildings and a general decline in the quality of life of the inhabitants.

In the cited case of Wrocław, such a process is the restriction of the development of cities of an earlier metric by modern fortifications. The Wrocław archives also document the process of building fortifications and its consequences for ordinary citizens. Particularly interesting are the stories in which the interests of the state and the great politics associated with it come into contact with the interests of ordinary people and their everyday life. We also encounter a similar conflict of interests in the modern world.

SOURCES

Archiwum Państwowe we Wrocławiu, Akta miasta Wrocławia

ref. 12190, (1651), Acta wegen einiger unterschiedenen Erbsassen vor dem Schweidnitzer Thore und Ohlauischen Thor zur Fortification gegebenen Ackerstücken. Vol. I.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12191 (1652), Acta wegen einiger unterschiedenen Erbsassen vor dem Schweidnitzer Thore und Ohlauischen Thor zur Fortification gegebenen Ackerstücken. Vol. II.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12192 (1653), Acta wegen einiger unterschiedenen Erbsassen vor dem Schweidnitzer Thore und Ohlauischen Thor zur Fortification gegebenen Ackerstücken. Vol. III.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12193 (1654), Acta generalia von dem Wiederaufbau der vor dem Nicolai—Thore und Ohlauischen Thore abgebrandten Häuser, deren Plätze woraus für gestanden zur Fortification gezogen worden und Verabfolgung sämtliche darauf haffenden Bonifications Gelder

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12194 (1655), Acta die Abschatzung und Vergütigung der zur Fortification eingezogenen Fundorum betr.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12195 (1656), Fortifications—Acta. Vol. I.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12196 (1657), Fortifications—Acta. Vol. II.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12197 (1658), Fortifications—Acta. Vol. III.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12222 (1683), Acta wegen der vom Niclas—Thore und Ziegel—Thore neuangelegten Festungwerke desgl. Wegen des Weges vom Niclas—Thore bis an die Huben.

APWr, AMWr, ref. 12277 (1738), Projekt zu Erbauung einiger neuen Kasernen in Anno 1772 und würdlichen Aufbauung derselben in Anno 1773 und zwar auf Ihre Koenigl. Majestät Kosten im Julio 1773 der Anfang.

Geheimes Staatsarchiv Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz

I HA, Geheimes Zivilkabinett, Rep.96, nr 616, Vol. F, G.

I HA, Geheimes Zivilkabinett, Rep.96 B, Abschriften von Kabinetsordres, 1740-1786, Vol. Vol. 71,72, 75, 79, 81

GStA SPK XI. HA, ref. D 70140, Straßenfassade der 1776 erbauten kasemattierten Kaserne

GStA SPK XI. HA, ref. E 72090, Plan von der Festung Breslau, Inglt. v. Poblotzki 1802

Biblioteka Uniwersytecka Wrocław

BUWr collecton ref. 2318, Barthel Weiner, Contrafactur der Stadt Breslau 1562, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:110177

BUWr collection ref. R 943 a, Architectura militaris. Gedr. Tabellen und Kupferstich-Zeichnungen. 1-13 u. A-XXXX, Valentin von Säbisch, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:119507

BUWr collection ref. R 943 b, Zeichnungen in KK. zur Fortificationslehre. J.B. Scheiter Ingen. invenit. Hennep sculpsit, Valentin von Säbisch, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:119508

BUWr collection ref. R 943 d, Handzeichnungen von festen Orten in Frankreich, Holland und Deutschland 1567–1635, Valentin von Säbisch, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:119360

BUWr collection ref. R 943 e, Handzeichnungen von festen Orten besonders in Italien und Ungarn 1565–1617, Valentin von Säbisch, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:119361

BUWr collection ref. 2494-IV.B. Bastion fortification project, by A. von Säbisch, circa 1630–1650, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:36750

BUWr collection ref. IV F 113 b vol. 2, Wernher, Friedrich Bernhard, Topographia seu Compendium Silesiae. Pars II, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:16339

BUWr collection ref. R 551, Wernher, Friedrich Bernhard, Topographia oder Prodromus Delineati Silesiae Ducatus, oai:www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:14302

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Bimler, Kurt. 1934. “Hans Schneider von Lindau ein Breslauer Stadtbaumeister.” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Geschichte Schlesiens 68: 118–132.

- Bimler, Kurt. 1940. Die schlesischen massiven Wehrbauten. 1. Fürstentum Breslau: Kreise Breslau, Neumarkt, Namslau. Breslau: Kommission Heydebrand-Verlag.

- Braun, Georg, Frans Hogenberg, and Rem Koolhaas. 2015. Cities of the World. Edited by Stephan Füssel. N.p.: Taschen.

- Brzezowski, Wojciech, and Marzanna Jagiełło. 2014. Ogrody na Śląsku, I, Od średniowiecza do XVII wieku, Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej.

- Caban, Mariusz. 2015. “Porównawcze badania pomiarowe cegieł z kościoła Salwatora we Wrocławiu.” In Cmentarz Salwatora. Pierwsza nekropolia wrocławskich protestantów, edited by Krzysztof Wachowski, (Wratislavia Antiqua 21), 197–213. Wrocław: Instytut Archeologii Uniwersytet Wrocławski.

- Chorowska, Małgorzata, Paweł Rajski, and Jerzy Serafin. 2012. Sprawozdanie z nadzoru architektonicznego nad wydobyciem detali kamiennych w trakcie porządkowania terenu Wzgórza Polskiego. Wrocław: typescript in the Archive of WUOZ.

- Creighton, Oliver, and Robert Higham. 2005. Medieval Town Walls: An Archaeology and Social History of Urban Defence. Stroud: Tempus.

- de Mirabeau, Honore-GabrielRiquetti. 1795. Von der Preußischen Monarchie unter Friedrich dem Großen. Leipzig: Dykische Buchhandlung.

- Duffy, Christopher. 1995. Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World 1494-1660. London: Psychology Press.

- Dybaś, Bogusław. 1994. “Podróż Tymoteusza Josta: przyczynek do kształcenia budowniczych w wielkich miastach Prus Królewskich na przełomie XVI i XVII w.” Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici. Nauki Humanistyczno-Społeczne.” Zabytkoznawstwo i Konserwatorstwo 25 (280): 111–125.

- Eysymontt, Rafał, and Stanisław Klimek. 2007. Wrocław. Architecture and History, Wrocław: Via Nova.

- Frank, Anita. 1995. “Albrecht von Sebisch (1610-1688): Das Leben eines Vermittlers und Bibliophilen.” Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis: Neerlandica Wratislaviensia 8: 73–93.

- Gierowski, Józef. 1958. “Dzieje Wrocławia w latach 1618-1741.” In Dzieje Wrocławia, edited by Wacław Długoborski, Józef Gierowski, and Karol Maleczyński, 337–540. Wrocław: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Igert, Arwed. 1939. Wehrrecht der Stadt Breslau unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der habsburgischen Zeit, Beiträge zur Geschichte der Stadt Breslau. Neue Folge, Heft 10. Breslau: Verlag Priebast. https://bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/107823/edition/106531/content.

- Kieseritzky, Ernst. 1903. Das Gelände der ehemaligen Festung Breslau. Breslau: Morgensterns Verlagsbuchhandlung.

- Klawitter, Willy. 1941. Geschichte der Schlesischen Festungen in vorpreußischer Zeit, Breslau: Kommissionsverlag Trewendt & Granier.

- Kmiecik, Piotr, Justyna Kleszcz, Katarzyna Gemborys, Robert Szwed, and Samuel Adu-Gyamfi. 2021. “A Methodology to Identify a Fragment of Painted Glass from Excavations at John Paul II Square in Wrocław.” Cogent Arts & Humanities 8 (1): 1. doi:10.1080/23311983.2021.1977511.

- Kmiecik, Piotr, and Robert Szwed. 2018. “Wystrój Kamieniarski Opactwa na Ołbinie w Świetle Najnowszych Odkryć Archeologiczno-Architektonicznych na Terenie Byłego Szpitala im.” Józefa Babińskiego we Wrocławiu, in: Od Benedyktynów i Premonstratensów Do Salezjanów. Dzieje Kościoła i Parafii św. Michała Archanioła na Wrocławskim Ołbinie, 79–85, 331–340. Wrocław-Borowianka: Instytut Historyczny UWr, Parafia św. Michała Archanioła we Wrocławiu.

- Kmiecik, Piotr, Robert Szwed, and Czesław Lasota. 2018. Wnioski konserwatorskie z badań archeologiczno-architektonicznych na terenie byłego szpitala przy ul. Jana Pawła II we Wrocławiu przeprowadzonych w obrębie bastionu kleszczowego. Wrocław: typescript in the Archive of WUOZ.

- Konczewski, Paweł, Roland Mruczek, and Jerzy Piekalski. 2010. “The Fortifications of Medieval and Post-Medieval Wroclaw.” In Lübecker Kolloquium zur Stadtarchaeologie im Hanseraum VII. Die Befestigungen, edited by Manfred Gläser, 597–614. Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild.

- Kuch-Breburda, Miroslav, and Vladimir Kupka. 2003. Pevnost Olomouc, Praha: Fort print.

- Lewicka-Cempa, Maria. 1980. “Szesnastowieczny projekt fortyfikacji bastionowych Nysy Jana Schneidera z Lindau.” PhD thesis. Wrocław: Instytut Historii Architektury Sztuki i Techniki Politechniki Wrocławskiej.

- Luchs, Hermann. 1866. “Über das äußere Wachstum der Stadt Breslau,mit Beziehung auf die Befestigung derselben.” Zweiter Theil, Jahresbericht der städtischen höheren Töchterschule am Ritterplatz zu Breslau, 1–11. Breslau: Graß, Barth & Comp.

- Markgraf, Hermann, and Otto Frenzel. 1882. Breslauer Stadtbuch enthaltend die Rathslinie von 1728 ab und Urkunden zur Verfassungsgeschichte der Stadt. Breslau: Josef Max & Comp.

- Menzel, Karl Adolf. 1807. Topographische Chronik von Breslau, neuntes Quartal, Breslau: Grass und Barth.

- Michael, Oda. 2006. Die Werkmeisterfamilie Bernhard, Peter und Franz Niuron – ihr Wirken in Schlesien, Anhalt und Brandenburg im späten 16. und frühen 17. Jahrhundert im Spiegel historischer Quellen, PhD thesis, Halle: Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg. http://sundoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/diss-online/06/06H100/prom.pdf).

- Minola, Mauro. 2010. Fortezze del Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta, San Ambrogio di Torino: Susalibri.

- Mruczek, Roland, and Michał Stefanowicz. 2010. “Południowy pas obwarowań i fortyfikacji Wrocławia w rejonie obecnego pl. Wolności na tle przemian przestrzennych i prawnych miasta średniowiecznego i nowożytnego.” In Non solum villae. Księga jubileuszowa ofiarowana profesorowi Stanisławowi Medekszy, edited by Jacek Kościuk, 401–454. Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr.

- Mühle, Eduard. 2015. Breslau. Geschichte einer europäischen Metropole. Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau Verlag.

- Neugebauer, Julius. 1876. “Der Zwinger und die kaufmännische Zwingerschützen-Brüderschaft nebst einer historischen Einleitung über die ehemalige Bürgermiliz und die Bürgerschützen-Brüderschaft.” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Geschichte und Alterthum Schlesiens, Beilage zur Bd 13.

- Notitz, 1770. Schlesische Instantien-Notitz oder dasitzt lebende Schlesien. Breslau: Verlag der Brachvogelischen Erben.

- Piekalski, Jerzy. 2007. “Neubau oder Weiterentwicklung? Frühneuzeitliche Stadtbefestigung in Breslau und Krakau.” Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit 18: 131–140.

- Podruczny, Grzegorz. 2011. Twierdza Wrocław w okresie fryderycjańskim. Wrocław: Atut.

- Podruczny, Grzegorz. 2023. “Czas wojen.” in Nysa, historia miasta, tom. 2, W cieniu twierdzy – na fali przemian (1741-1945) edited by Tomasz Przerwa, 12–44. Wrocław: Gajt.

- Podruczny, Grzegorz. 2024. The King and His Fortresses. Frederick the Great and Prussian Permanent Fortifications 1740–1786. Warwick: Helion & Company.

- Pol, Nikolaus. 1823. Jahrbücher der Stadt Breslau von Nikolaus Pol 4, edited by Johann Gustav Gottlieb Büsching, Büschingand Johann Gottlieb Kunisch, (Zeitbücher der Schlesier 4). Breslau: Verein für Schlesische Geschichte und Altertümer.

- Schreiber, Heinrich. 1858. Geschichte der Stadt und Universität Freiburg im Breisgau. Freiburg: Verlag von Franz Xavier Wangler

- Stein, Bartholomäus. 1995. Die Beschreibung der Stadt Breslau der Renaissancezeit durch Bartholomäus Stein. Edited by Rościsław Żerelik, Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Arboretum.

- Śledzik-Kamiński, Rafał. 2021. “Bastion fortifications in Wiązów and Żórawina as an example of less known Silesian implementations by Hans Schneider von Lindau.” Architectus 4 (68): 121–128. doi:10.37190/arc210412.

- Szwed, Robert, Dąbrowski Paweł, and Kmiecik Piotr. 2023. “ANEKS 1 Wnioski z badań archeologiczno-architektonicznych na terenie działki przy ul. Czystej 4 we Wrocławiu." Wrocław, typescript from the author’s archive.

- Wernicke, Ewald. 1881. “Die italienischen Architekten des 16. Jahrhunderts in Brieg.” Schlesiens Vorzeit in Bild und Schrift 3 (38): 265–275.

- Wojcieszak, Magdalena. 2015. “Obrządek pogrzebowy na cmentarzu Salwatora we Wrocławiu w świetle badań archeologicznych.” In Cmentarz Salwatora. Pierwsza nekropolia wrocławskich protestantów, edited by Krzysztof Wachowski, (Wratislavia Antiqua 21), 19–58. Wrocław: Instytut Archeologii Uniwersytet Wrocławski.

- Ziątkowski, Leszek. 2001. “Die räumliche und architektonische Entwicklung Breslaus vom 16. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert.” In Atlas historyczny miast polskich, IV, Śląsk, 1, Wrocław, edited by Marta Młynarska and Rafał Eysymontt, 21–24. Wrocław: Via Nova.

- Żurek, Adam. 1997. “Dawny zespół klasztorny Benedyktynów, następnie Norbertanów pw. św. Wincentego na Ołbinie.” In Atlas architektury Wrocławia, t. 1, edited by Jan Harasimowicz, 7. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie.