ABSTRACT

This paper describes a virtually unknown Russian alphabet table, Alphabetum Russarum. It consists of only two leaves and presents the Russian alphabet, including detailed pronunciation rules in Latin. The copy is damaged, the impressum is lost. It is clear, however, that the printer was Peter van Selow (1582–1650). The only known copy belongs to the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar, where it functions as a kind of appendix to the Lutheran catechism, printed in Stockholm in 1628 by the same printer, Van Selow. Alphabetum Russarum was undoubtedly intended as an “international” counterpart to the well-known Swedish edition Alfabetum Rutenorum, although the former does not contain any texts from Luther’s catechism. Both tables appeared without a print date, but they were apparently issued in the late 1630s or the early 1640s. The unique Weimar copy of Alphabetum Russarum is also very special in another way: along with minor additions and corrections to the printed text it also contains a handwritten appendix in Latin, most likely written by Laurentius Rinhuber, the assistant to the first “Russian playwright” and author of the first court plays ever presented in Moscow (in the 1670s), the Lutheran pastor Johann Gottfried Gregorii.

1. Introduction

The Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek (HAAB) in Weimar hosts a small imprint of only two leaves with the title Alphabetum RussarumFootnote1 (henceforth: A. Russarum). The imprint has been added as a kind of appendix to a Lutheran catechism, translated into Russian by Hans FlörichFootnote2 and printed in 1628 by Peter van Selow (1582–1650):Footnote3 “Κατηχήσις [sic!] си есть грѣческое слово. А поруски именуется Хрстьянское учение перечнем … ” (‘Κατηχήσις. This is a Greek word, and the Russian title is summary of Christian teaching’).Footnote4 The seventeenth-century vellum binding (with the signature Cat XVI 517a) thus contains two related imprints.Footnote5 They are both extremely valuable for our knowledge about Russian (and, to a certain extent, Swedish) cultural history: the copy of the Russian catechism is extraordinary because it contains an interesting hand-written introduction in Latin, as well as a Latin parallel text, both added, I suggest, by Laurentius RinhuberFootnote6 (who played an important role in connection with the early Russian court theatre). The alphabet table – which also contains additions made by Rinhuber (see section 2.2) – is altogether unique, and whereas the catechism is relatively well preserved, the A. Russarum is in a very poor condition; as a result, the whole volume can be studied de visu only with special permission and in the presence of a book restorer.

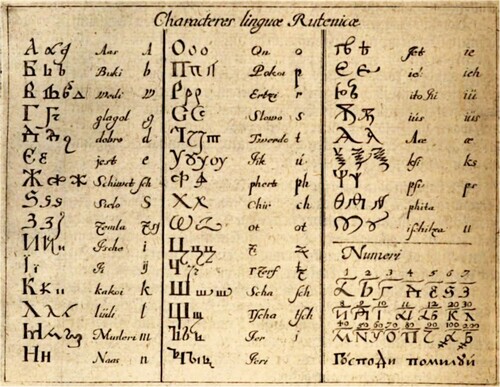

Figure 1. (left): The “title page” of the Alphabetum Russarum. (right): Verso of fol. [1].Footnote7

![Figure 1. (left): The “title page” of the Alphabetum Russarum. (right): Verso of fol. [1].Footnote7](/cms/asset/f8fc31d5-1795-4afc-b5ef-42dbc13efa14/ssla_a_2270944_f0001_oc.jpg)

Unfortunately, the Weimar A. Russarum is damaged (as can be seen in ): approximately one fourth of the first leaf is missing (about 20% of the text). The reason for this damage is apparently that this imprint had to be folded both vertically and horizontally in order to fit the quarto leaves into the octavo book, something that can be seen clearly on the following leaf:Footnote8 at the horizontal folding line of the first leaf, the lower part must have been torn off. Although in this way the part where the impressum would have appeared is lost, it is clear to all specialists that A. Russarum comes from Peter van Selow’s printing office. It is also evident that A. Russarum is a very close relative to Alfabetum Rutenorum (A. Rutenorum), a more widely known item produced by Van Selow, which has been preserved in several complete copies.Footnote9 A. Russarum has never been mentioned in any bibliography, nor in studies about Van Selow.Footnote10

When I first studied the Weimar copy of Van Selow’s catechism (in 2017), A. Russarum did not have a separate bibliographic entry at HAAB. I had ordered the volume exclusively because of the catechism, so the extremely rare alphabet table came as a big surprise. Nowadays the imprint can easily be found in the library’s digital catalogue: the term Alphabetum Russarum has been entered among the metadata information.

Since the title is now known, an internet search today yields some results. Surprisingly enough, they are neither from scholarly work about the book’s history nor from Slavic studies: the Hungarian folklorist Gyula Sebestyén (1864–1946) found a copy of A. Russarum during a research trip to Germany at the beginning of the last century. In two publications he mentioned the imprint he had seen in a manuscript miscellanea volume at the city library in Hamburg (Sebestyén Citation1903, 258–259; Citation1915, 105). The imprint was bound within the second manuscript of this volume (as No. 342), “Grammatica Syriaca ad Methodum Schickardianam adornata, indicans tantummodo, in quibus Syri ab Ebraeis dissident” (fols. 33–40). Sebestyén was totally uninterested in the printed A. Russarum – he was only concerned with the manuscripts in the volume, so his information about the imprint is terse: “It should be noted that between fols. 4 and 5 of the second study (manuscript No. II, between fols. 36 and 37 of the [whole] volume), a quarto imprint of four pages has been bound, from the eighteenth century,Footnote11 with the title: Alphabetum Russarum Stockholmiae. Typis Petri a Selav. Without a year.”Footnote12 Our conclusion must be that the whole imprint consisted of only two leaves and that the Weimar copy thus is complete, except for the paper loss of the first leaf. Although libraries and archives in Hamburg have been provided information about this volume, it could not be located, and there is reason to fear that it did not survive the bombing of World War II. Therefore, for the time being, the damaged Weimar copy must be regarded as the only surviving one.Footnote13

2. Historical Background: Why Did Sweden Become the Cradle of Russian-language Lutheran Catechisms?

After the conclusion of the Stolbova Peace Treaty between Sweden and Russia (1617), the Swedish Crown for the first time had to deal with Russian-speaking Orthodox subjects within its own borders. Sweden had been a multilingual and multicultural country for a long time, so Russian-speaking subjects would not per se have been a major problem for King Gustavus Adolphus, but it was harder for the Swedish government to accept the fact that large territories were now inhabited by Russian-Orthodox believers. As a result, the king decided that religious books were to be issued in Russian, first and foremost a Lutheran catechism. Apparently, he had been informed about the existence of Van Selow, the young and promising type founder, who – among other things – had assisted the Silesian-born scientist and medical doctor Petrus Kirstenius with the Arabic typefaces for the 1608 imprint Tria specimina characterum Arabicorum in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland).Footnote14 Van Selow came to Sweden in 1618; however, he stayed for only two years, returned to his home town in Mecklenburg, and only when he was summoned to Stockholm for a second time did he move to the Swedish capital with his wife and childFootnote15 – apparently, he had not been satisfied with the working conditions and/or payment during his first period in Sweden.

The first printed translation of Luther’s catechism into Russian is Van Selow’s earliest Stockholm imprint. The translation was made by the Swedish Crown’s translator Hans Flörich, a German-Russian bilingual, presumably born in Russia to German parents. Flörich – or Anca Arpov, as he was called in Russia – started his career as a German-language translator in the service of three subsequent Russian tsars: Fedor I, Boris Godunov, and Vasilij Šujskij. In September 1609 he was sent to Jacob de la Gardie’s troops in Kexholm. Together with his brother-in-law Hans Brakel (in Russian service called Anc(a) Brakelev), he entered the service of King Charles IX and continued to work for Gustavus Adolphus. Most likely Flörich never learned Swedish during his new life in Sweden: all his preserved translations are made from Russian into German.Footnote16 Although he undoubtedly was a native speaker of both languages, he presumably lacked formal education when it came to writing. In any event, a Russian chief clerk (d’iak), Isa(a)k Torčakov, was ordered to produce the fair copy for the typesetter.Footnote17

3. The Weimar copy of the Alphabetum Russarum

3.1. General Remarks

In another paper I have argued that A. Russarum and A. Rutenorum are “unidentical twins” in the sense that they are closely related: they were produced by the same printer (most probably at just about the same time) and allegedly written by the same author (see Maier Citation2021). They are also both printed on paper of low quality, either with no discernible watermarks at all or marks that cannot be identified in the existing watermark albums.Footnote18

What do we know about the print date? For the totally unknown A. Russarum, of course, no dating attempt has been made. (Sebestyén’s guess “18th c.” can hardly be considered as a serious suggestion.) For A. Rutenorum, library catalogues have adopted the year suggested by Rudbeck (Citation1925, 320), viz. 1638 (he does not exclude an earlier year).Footnote19 I do not find Rudbeck’s argumentation convincing and have previously dated this imprint to the period 1638–1645 (Maier Citation2012, 353). It may be impossible to prove which one of the “siblings” came first, but I would suggest that A. Rutenorum – a Swedish edition, aimed for the education of the Swedish Crown’s “Russian translators” – was the earlier publication, and that it was then decided to make an “international” edition, too, without the catechism texts included in the Swedish version. (Any bilingual texts would certainly be impossible in an international edition.) Also the fact that the version in Latin shows some improvements in comparison to the Swedish one points to the hypothesis that A. Russarum was issued after the publication of A. Rutenorum. There are two areas in particular in which A. Russarum enhances the “Swedish” edition:

| (1) | A. Rutenorum does not mention the number values of the Cyrillic letters, whereas these are listed in the “international edition,” A. Russarum. | ||||

| (2) | More phonetic rules were added: A. Rutenorum contains only 10 pronunciation rules, whereas the “international version” gives rules for nearly twice as many letters (or letter groups), viz. 18.Footnote20 | ||||

3.2. Handwritten Additions to the Printed Letter Table

The only copy of A. Russarum known today contains some handwritten corrections and additions (see below). I attribute these additions (hand 1) to Rinhuber: the handwriting is very similar to Rinhuber’s, as preserved in numerous signed documents. Apparently, the annotator knew some Polish – although the author of the lines added in brown ink in (hand 2) is more knowledgeable in Polish than the first hand. Rinhuber may have picked up some Polish words and phrases already as a child, growing up in the eastern part of the German-speaking territory. (That he was interested in languages and managed to learn them with good results becomes clear from his numerous long letters in really good Latin, spiced with Greek citations, and also from his letter in French to King Louis XIV, which is reproduced in the appendix of Mazon and Cocron 1654; moreover, he learned Russian while in Moscow.) Apparently he understood that for a large group of Russian consonants – the sibilants – a correlation with Polish would be more helpful than any comparison with Latin sounds or letters, so a Polish column was added to the left of the printed table for eight Cyrillic letters, under the headline “Pol.” However, Rinhuber’s knowledge of Polish was inadequate and he made some mistakes. Thus on p. [2] the Polish graphemes ‹ż, ś, z› were added, as correspondences to Russian ‹ж, s, з›. Whereas ‹z› is correct and ‹ż› acceptable, the parallel does not make sense at all for the second Russian sibilant, ‹s› (“Zelo”); this letter should have been transcribed into Polish in the same way as ‹з›, that is ‹z›. The annotator might have been confused because the imprint had ‹s› in the Latin column for all three Cyrillic letters – a very rude approximation, based on the fact that [s] is the only sibilant sound in (Classical) Latin. (On the same page, the letter ‹w (vv)› in the second column was corrected: it was “replaced” with a cursive variant, ‹w›.)

On p. [3], the letters and letter groups ‹c, ć, ſz, cż/ſzcz› were added,Footnote21 as correspondences to Cyrillic ‹ц, ч, ш, щ›. Here only the first part of the last correspondence, ‹cż›, raises some questions, whereas ‹ſzcz› can be regarded as an acceptable solution. Moreover, the horizontal line of the letter ‹ш› has been reinforced in ink – it was present (as can be seen in the Cyrillic letter name, “Ша”), but apparently not prominent enough for our annotator. Two lines further down, to the left, in the line of the grapheme ‹ъ›, the phrase “in abbreviat[ura] y “ has been added – apparently, the annotator found it necessary to introduce the paerok ( ̾), a sign often used as a “short form” of ‹ъ› (e.g., об ̾явить for объявить).

On the top of this page, above the ligature ѿ (Latin “Ot”, listed with the number value 800), our annotator has noted: “ѿ. Est contractio ex ω et T. Mirum cur literam peculiarem faciant” (‘ѿ is a contraction of ω and t. [It is] astonishing that they make a special letter [of these two]’).

For Cyrillic ‹ы› and ‹ѣ›, which did not have Latin correspondences in the imprint, the transcriptions ‹ü› resp. ‹ie, i› were added (), and the form itself of the ‹ы› was “improved” by adding a small horizontal line to the right element of the letter (the result being something like ‹ьɨ›, albeit without a dot on the second element).

It is impossible to decide when the additions to the imprint were made. It cannot be excluded that Rinhuber himself might have used this very copy of A. Russarum when he was learning Russian, probably after his arrival in Moscow in 1668.Footnote22 Another possibility is that he annotated the copy when he planned to sell or give away the combined volume, presumably during his extended tour through Europe in 1678–1684.

3.3. The Handwritten Appendix

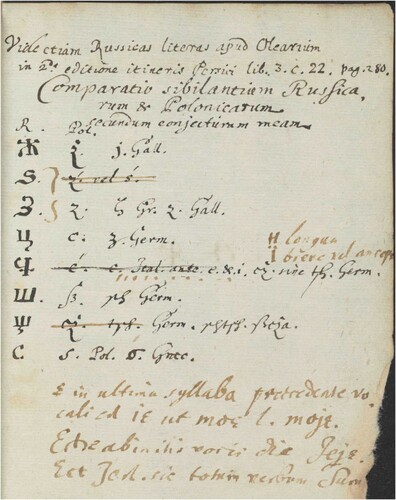

After the imprint follows an appendix of four pages (), written in ink on empty leaves. In these additions we can clearly discern two different hands, which I will call “hand A” and “hand B” (as above). Most of the text was written by hand A, whereas some corrections were made – and a couple of sentences added – by hand B (in another ink; see ):

In his introduction (), the annotator first refers to a comparable alphabet table, notably from the second edition of Adam Olearius’ book about his travels to Russia and Persia: “Vide etiam Russicas literas apud Olearium in 2da editione itineris Persici lib[er] 3 c[aput] 22. Pag. 280” (see ).Footnote23 Olearius’ table first presents the Cyrillic letters in two to four different variants (print forms, then cursive forms), followed by their Russian names, in transliteration: Aas, Buki, Wedi, … , and also their “correspondences” in German.Footnote24 At the end – after a horizontal line – the number values are given, followed by the phrase “Господи помилуй” ‘God, have mercy’. We note that for “2” the Cyrillic letter ‹в› should have been used (instead of ‹б›), and that “#а #б” – correctly: #а #в – should have been translated as 1000 resp. 2000, not 100, 200.

Figure 6. “Characteres linguæ Rutenicæ” according to Olearius (Citation1656, 280).

The table presented on the following pages of the appendix () roughly follows the order of Olearius’ table, but it refrains from repeating the letter names and the Latin correspondences from the printed A. Russarum. Moreover, the list in the appendix is limited to cursive letter forms (including superscript letters). It also adds a special line for the letters ‹у› (in addition to ‹ȣ›) and ‹ь›, not listed in Olearius’ table, and while Olearius in the third column presents additional forms of the letter ‹Є›, the annotator follows A. Russarum and gives the “new” letter ‹Э›, nowadays known as “э оборотное,”Footnote25 thus relying in these instances more on A. Russarum than on Olearius. We can also note some interesting additions: after the cursive forms of the letter ‹г› there is an addition “g. Belgicum.” It is not quite clear what the annotator wanted to tell his reader: was he thinking of the “sacred word” Бог ‘God’, where the fricative pronunciation of the last consonant is in fact quite similar to that of Dutch ‹g› (in initial, middle, and final position, cf. geografie, Haag)? A pronunciation rule for one word, not even mentioning the relevant word? Or might he have had in mind another sacred word, господи ‘Lord’, or Бога ‘God’ (gen./acc.), both pronounced with a voiced fricative sound, [γ]? Or was he thinking about the South-Russian fricative pronunciation of ‹г› in many different positions? In the last two cases, a comparison with the Greek letter ‹γ› would have been a better choice; cf. γόνος ‘offspring’ or γάλα ‘milk’ (but perhaps not all students of classical Greek were aware of this “modern” Greek pronunciation), because in Dutch (or Flemish) ‹g› is pronounced as a voiceless fricative. Two more letters have comments, ‹ѣ› and ‹Ѫ›. The former is about pronunciation: “ut бѣ bie῎Footnote26 lege bje῎ ụel bä” (‘like бѣ, bie, pronounce [bje] or [bæ]’; this comment differs from the pronunciation rule given in the printed table); the latter, ‹Ѫ›, has the comment “jus nusqua[m] scribitur” (‘jus is not used in writing’; ).

Before the “Olearius-inspired” list of cursive letters, on the first page of the appendix (), hand A presents a comparison between Russian and Polish sibilants under the headline “Comparatio sibilantium Russicarum & Polonicarum secundum conjecturam meam.” First the Russian consonants are listed (under the letter “R.”), followed by a column for Polish (“Pol.”); in the third column we find comparisons with French, German, Italian, and Greek (without a specific headline).

contains only the text written in black ink (hand A), before the corrections and additions made in brown ink (by hand B). The corrector (B) changed only those comparisons that did not make sense. For instance, he deleted the correspondence “ź. vel ś.” for Cyrillic ‹S› (“Zelo”) and correctly combined this grapheme with ‹З› – the pronunciation for both is [z] (incidentally, ‹ś› had also been erroneously given in the addition to the imprint; see ). Where hand A had deleted the line “ć. c. Ital. ante e. & i.” (a correct statement!), hand B brought it back, using a dotted line. Above this, hand B added the words: “и longum | ï breve vel anceps,” meaning ‘‹и› is [pronounced as] a long sound; ‹ï› either short or indefinite [i.e., short or long]’. The corrector (B) accurately deleted the comparison of ‹щ› with Polish ‹cż› and German ‹tsch›, leaving only the variant “schtsch. ßcża” [ = szcża]. All in all, the original table by hand A contained some erroneous information, and all these cases were corrected by a person with greater knowledge of both Polish and Russian pronunciation than that of the original author.

Table 1. Pronunciation of Russian sibilants (only hand A; for corrections by hand B, see below)

We also have one longer addition by hand B (brown ink). It is not about Russian sibilants; here, the pronunciation of the Russian letter ‹e› is explained:

Є in ultima syllaba praecedente vo-

cali est iє ut moє ł. [ = vel] mojє.

ЄжєFootnote28 ab initio vocis dic Jeje.

Єст Jest. Sic totum verbum Sum.Footnote29

3.4. Who Was the Annotator of the Imprint, the Author of the Appendix, and the “Corrector”?

There is strong evidence for the hypothesis that the main annotator was Laurentius Rinhuber, to whom I also attribute the introduction and the Latin parallel text to the 1628 catechism. Regarding the corrector (hand B), we are looking for someone who – in addition to Latin and Greek – also knew Russian and Polish. My first hypothesis was the famous orientalist Hiob (or Job) Ludolf (1624–1704), but comparisons with his signed manuscripts did not confirm this assumption.Footnote31 However, the Ludolf family is not yet ruled out completely: Hiob’s nephew, the Slavist Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolf (1655–1712), is another strong candidate. Hand B is not exactly like H. W. Ludolf’s handwriting in his signed letters, but there can be decades between the corrections of the A. Russarum and the diary entry of 1711 that I used as an object of comparison.Footnote32

4. How Did the Alphabetum Russarum End Up in the Weimar Library?

Since this small imprint formerly was not catalogued as a separate entity, we have to search old library catalogues for Van Selow’s Russian catechism (1628). According to librarian Katja Lorenz, it might have belonged to the collection of catechisms (comprising about 1 200 volumes) that was once in the possession of Caspar Binder (1691–1756). In this case the volume would have been acquired by the Ducal Library of Weimar in 1757. However, the book itself does not contain an owner’s note, and the two volumes of the Binder catalogueFootnote33 also mention titles received after the acquisition of the Binder collection. The addition “a” in the signature (517a) might point to a later acquisition date,Footnote34 as does the fact that the entry about Van Selow’s catechism is placed on a left-hand side in the catalogue, which is where later acquisitions (up to the year 1849) used to be registered. The entry reads: “Catechismus Lutheri Slavonice translatus. Stockh. 1628,” followed by the – correct – information that the translation was initiated by King Gustavus Adolphus for the church of Ingria,Footnote35 and the allegedly wrong statement that the handwritten Latin parallel text in the margins was added by Hiob Ludolf (“c[um] vers[ione] Lat[ina] Mspt [ = Manuscripta] clariss[imi] Jobi Ludolfi”). In fact, it cannot be excluded that Hiob Ludolf might have been the owner of the book at some time, but I do not agree that he was the annotator of the catechism; as mentioned before, I attribute both the handwritten introduction and the Latin parallel version in the margins to Laurentius Rinhuber.

I will dwell a bit on Rinhuber because his role in Russian cultural history during the 1670s and the first half of the 1680s can hardly be overestimated.Footnote36 Born in the Thuringian town Lucka (Landkreis Altenburger Land),Footnote37 presumably around 1648–1649, he studied at the gymnasium of Altenburg for six years, 1660–1666. In January 1668, after having studied at Leipzig University for slightly more than a year, Rinhuber joined medical doctor Laurentius Blumentrost, the tsar’s future physician, to go to Moscow as an assistant. Rinhuber played a very important role in the context of the first Russian court plays, starting in 1672, particularly the first one, about the biblical story of Esther and Ahasverus (commonly known as Artakserksovo dejstvo), written by J. G. Gregorii, the Lutheran pastor in Moscow.

Rinhuber would not generally stay for long in any given place. He was an adventurer who loved to travel and had many travel plans. His activities as a diplomat (sometimes self-proclaimed) in the service of Tsar Alexis (Aleksej Michajlovič, r. 1645–1676), Duke Ernst (“the Pious”) of Saxe-Gotha (and after 1675 his son Frederick/Friedrich), the elector of Saxony, and possibly some other rulers, helped Rinhuber to carry into effect some of his travel plans. He stayed in Moscow four separate times: first from spring 1668 to October 1672, next for a very short sojourn during the summer of 1674, and again from August 1675 to March 1678, when he set out for a new long trip – to England (via Helsingør), France, Italy, and Germany (via France once more). On 7 June 1684, he was back in Moscow for the last time (and only for a couple of months):Footnote38 on 20 June he delivered letters from Duke Frederick of Saxe-Gotha (of 1 May 1683), from the Elector Johann Georg III (of 9 April 1684), and his own letter (dated 10 June) in the presence of the co-tsars Ivan and Peter.Footnote39 On 10 July he presented some gifts from Duke Frederick to the Boyar V. V. Golicyn; medicine and a copy of Hiob Ludolf’s book about Ethiopia are mentioned (Dumschat Citation2006, 439 – apparently, a copy of Ludolf Citation1681). Although Rinhuber’s travel routes during the years 1678–1684 are not known in every detail, it is likely that he was in contact both with the Saxon elector (presumably in Dresden) and Duke Frederick of Saxe-Gotha on his way to Moscow in 1684. One hypothesis would be that the volume containing the Stockholm catechism with the appended A. Russarum might have been handed over to one of the dukes in 1684. Rinhuber also might have given – or sold, since he always was lacking money – the volume to Hiob Ludolf.Footnote40

There are some more open questions when it comes to the history of the volume from Stockholm via Moscow to Weimar. For instance, we do not know whether the copy of A. Russarum was bound together with the catechism already in Sweden, before it was sent to Moscow, or if Rinhuber had the volume bound in vellum in Germany. The two imprints might have been bound together because the alphabet table was considered to be a helpful means for some speaker of another language who wanted to read the Russian (and Slavonic, for the citations from the Bible) book. Another interesting question is how Rinhuber might have obtained the catechism of 1628 and A. Russarum in the first place (either as two separate imprints or already bound together in one volume). My most qualified guess is that he might have come across these treasures through pastor Gregorii’s widow (the pastor had died on 16 February 1675; Bogojavlenskij Citation1914, 45). The Lutheran communities in Moscow apparently had at their disposal some copies of the Stockholm catechism.Footnote41 The “Rinhuber-Moscow connection” could also explain why not only the printed catechism (with A. Russarum) ended up in Weimar, but also a fragment of the earliest Russian court play, about Esther and Ahasverus.Footnote42 It appears that Rinhuber’s hand can be identified also in the additions and corrections to this manuscript, so possibly the vellum book and the fragment of Gregorii’s Esther play might have been given away (or sold) together and ended up in the Weimar library at the same time. Rinhuber was busy cultivating possible sponsors, and he might have used these Russian rarities as a kind of “currency.” If we suppose that Rinhuber sold the combined volume to Hiob Ludolf, perhaps together with the fragment of the play text, Ludolf might have passed it on to his nephew, Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolf, who was a really good Slavist and might have corrected and annotated Rinhuber’s appendix. He would have appreciated these Russian rarities more than anybody else. (However, I am not aware of any direct contact between Rinhuber and H. W. Ludolf.)

A subsidiary effect of this research about the Alphabetum Russarum is that Laurentius Rinhuber’s role in dispersing cultural-heritage objects from one country to another seems to have been confirmed once more. His participation in the production of the Lyon copy of Artakserksovo dejstvo has been known for many decades (see Mazon and Cocron Citation1954). In that case, and also in the case of the “Weimar fragment” of the same play, Rinhuber was spreading, in the first place, Russian cultural heritage to France and Germany respectively, but actually also German cultural heritage, because we would not have access to the original play text at all without his adding the German parallel text in these two copies with his own hand. But last and most important, it can now be shown that two Swedish cultural-heritage prints – one rare book and a unique seventeenth-century Russian alphabet table – also came back to Western Europe from Russia through the activities of the Saxon adventurer. Rinhuber himself was certainly not aware of his contribution to cultural history; for him, these manuscripts and imprints were rather valuable objects that could open a door for him or bring him some other compensation.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the librarians at the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek (Weimar) for their valuable help during my two stays in Weimar, especially Katja Lorenz. I am also grateful to Lars Bruzelius, Claudia Jensen, Sebastian Kempgen, and Robyn Radway, who have read a previous version and proposed some improvements, as well as the anonymous peer reviewers for their meticulous reading and helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The feminine form Russarum is surprising. This might have been the result of a mistake, instead of Russorum, or Russae, Russarum can have been formed in analogy to forms like Sarmatae, Sarmatarum; Getae, Getarum; Odrysae, Odrysarum (I am grateful to Hans Helander for these parallels).

2 Flörich’s own text is in Russian. However, many passages in the printed book are verbatim quotations from the Church Slavonic Bible (1580–1581). Flörich’s knowledge of Church Slavonic was rudimentary, almost non-existent; he could not translate anything into this language – however, he managed to transcribe from a printed Slavonic book. In this he followed King Gustavus Adolphus’ order of 10 June 1625: Luther’s explanations were to be translated into colloquial Russian, and all Biblical quotes were to agree with the Church Slavonic Bible (National Archives Stockholm, Riksregistratur 1625, June – Sept., fol. 269v).

3 The years of Van Selow’s birth and death appear in a funeral sermon by Johann Christopher Hingher: “Leichbegäng- und Ehrengedächtnis-Predigt dem weyland ehrnvesten und kunstreichen Herrn Peter von Selow, gewesenen Buchdrucker, Schriftgießer und Buchstabenschneider: den 8.Martij, im Jahr 1650” (Stockholm: Meurer 1650), which is not documented in Sweden and – to the best of my knowledge – has never been mentioned in Swedish scholarship. Württembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart houses two copies (WLB, Theol.qt.3269; Fam.Pr.oct.K.1651). I wish to thank this library for their quick response to my copy request. For a detailed study of Van Selow’s life, see Maier Citation2022.

4 The whole volume is accessible on line via HAAB’s catalogue, https://haab-digital.klassik-stiftung.de; the URN is: urn:nbn:de:gbv:32-1-10026516257 (A. Russarum starts at image No. 163). The Russian orthography in the quotation from the title page and also in all subsequent quotations from seventeenth-century Russian imprints and manuscripts has been slightly modernized: letters that are no longer being used in Russian have been substituted by their modern equivalents (an exception is made for the letter ѣ, which has been kept, and in discussions about specific letters mentioned in the alphabet table). Spaces have been added in cases where they make the text easier to read (e.g., Апоруски → А поруски). Superscript letters are written in italics on the baseline.

5 The binding thread goes through the abecedarium, it is slightly visible between the two leaves of the imprint.

6 The handwritten additions to both imprints were compared with numerous letters written by Rinhuber, among them one datelined Dresden, 10 March 1673, signed by Rinhuber, with his “m[anu] p[ropria]” (‘[written] by my own hand’; Landesarchiv Thüringen – Staatsarchiv Gotha, Immediate, No. 1647, fols. 1–5). Other manuscripts that have been attributed to Rinhuber – for instance, his additions to the Lyon manuscript of the Esther play – are more problematic because they are not signed, although the attribution made by Mazon and Cocron (Citation1954) is certainly correct. On the Russian court theatre, which was established during Tsar Alexis’ final years, see the recent monograph Jensen et al. Citation2021.

7 The photographs from Alphabetum Russarum are printed with permission by Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek (Cat XVI 517a). All rights reserved.

8 This fact is also mentioned in the library’s bibliographic data: “Scope: [71] fols., [2] folded leaves.”

9 I have studied five complete copies de visu: Uppsala University Library (two copies, one of which is available online: http://libris.kb.se/bib/2512716), The National Library in Stockholm, Gothenburg University Library (online: http://hdl.handle.net/2077/39963), and The Royal Library in Copenhagen. In 1876, a copy (defective, with three leaves missing) was acquired by the Imperial Library in St. Petersburg; however, it is no longer in this library, nowadays Russian National Library (for details see Maier Citation2012, 335, note 9).

10 Cf., for instance, the detailed, almost complete list of Peter van Selow’s print production, compiled by the well-known Swedish book historian Gustaf Rudbeck (Citation1925). He lists 40 items, printed between 1628 and 1648.

11 Sebestyén’s dating was a bad guess since Van Selow died in 1650. His last known imprint dates from the year 1648 (Rudbeck Citation1925, 333–334).

12 “Megjegyzendő, hogy a II. sz. értekezés 4–5. (a kötet 36–7.) lapja közé egy négyoldalas 4-rétű XVIII századi nyomtatvány van kötve e czimmel: Alphabetum Russarum Stockholmiae. Typis Petri a Selav. Év nélkül” (Sebestyén Citation1915, 105, note 1; the same information is given in ibid. 1903, 258–259). On the back of the volume its title was written: “Philologica miscellanea. Ms App. XX. 4o.” There was also an Ex libris with the text “ex Biblioth. Hamburg. Wolfiana” and an entry made by a librarian: “Critica Varia. Contenta hujus vol. vid. in fine pag. ult.” This table of contents at the end of the volume lists ten miscellaneous manuscripts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; the list is reproduced in ibid.

13 Of course, this situation could change as more studies and digital catalogues from both libraries and archives become available.

14 Van Selow’s assistance is attested by Kirstenius in another book published during the same year: Grammatices arabicae liber primus, Sive orthographia et prosodia arabica (Breslau 1608). A whole paragraph is dedicated to the man who had cut and cast the Arabic typefaces, notably “the honorable, talented and diligent young man Petrus à Selaw” (Kirstenius Citation1608, 12–13). A fulltext version of this book is available on line via VD17 (www.vd17.de).

15 See the funeral sermon by Johann Christoph Hingher (cf. note 3). It has been asserted many times that Van Selow had Dutch roots, following Jensen (Citation1912, 138) and Collijn (Citation1913, 247). This hypothesis, which has never been substantiated, can now be discarded. I suppose that the word van in the printer’s name was the only reason for this assumption. Van Selow might have preferred this “Dutch” form to the German von because the Dutch connection might have been advantageous for a type founder and printer, but it might also just render the Low German form used in his home town, Grevesmühlen in Mecklenburg. (Hingher writes Gröbißmöhlen / Gröbeßmöhlen; however, there can be no doubt that Grevesmühlen is meant, near Wismar, where the future type founder went to school for two years, from 1594.)

16 The most up-to-date study about Hans Flörich’s life and activities both in Russia and in Sweden, based on Russian and Swedish archival documents, is Droste and Maier Citation2010.

17 About the translation of Luther’s catechism into Russian see, for instance, Ďurovič Citation2003; Jensen Citation1912; Nyholm Citation1996; Sjöberg Citation1975; Citation1984; Tarkiainen Citation1974. A. Pereswetoff-Morath (Citation2010, Citation2012) has studied the corrector Isaak Torčakov’s life. A monograph about all Russian catechisms printed in Sweden between 1628 and 1701 and their handwritten copies is in preparation (Maier, Citationforthcoming).

18 For the watermarks in A. Russarum see the photographs made available by HAAB (images No. 182 and 183): https://haab-digital.klassik-stiftung.de/viewer/image/1713185296/182/LOG_0014. One of the five copies of the A. Rutenorum that I have studied (notably one of the two kept at Uppsala University Library) differs in this respect from the other four: it is printed on better paper.

19 Already Kari Tarkiainen (Citation1974, 75) disputed Rudbeck’s dating method, which was based exclusively on a possible damage of the ornament – a vignette with flowers and leaves – on the last page of the imprint.

20 For a complete transcription and discussion of the pronunciation rules in A. Russarum, in comparison with A. Rutenorum, see Maier Citation2021.

21 The digraphs ‹ſz, cż› and especially the group ‹ſzcz› are very hard to read because the ink has spread and the letters become blurred. I am grateful to Lars Bruzelius, who has managed to elucidate the original letter shapes, using image enhancement.

22 It is hard to imagine that Rinhuber would have found this introduction to the Russian alphabet in Germany, before he set out for Russia. However, it does seem plausible that the Lutheran communities in Moscow had been provided not only with copies of the 1628 Lutheran catechism (see note 41), but also with copies of Van Selow’s alphabet table.

23 Rinhuber refers to Olearius’ book also in other contexts, for instance in his letter of 15/25 April 1673 (Rinhuber Citation1883, 42).

24 It is not made explicit that Russian and German are being compared, but ‹ch› for Cyrillic ‹х› or ‹sch› for ‹ш› make it clear that Olearius in the first place collates the Russian letters with his native German language. On the other hand, ‹æ› for Cyrillic ‹я› looks more Latin than German.

25 A. Rutenorum and A. Russarum are the first printed alphabet tables that list the letter ‹Э› – incidentally in the place it was to occupy in Russian dictionaries after Tsar Peter’s reforms (Maier Citation2012, 351).

26 The syllables “bie, bje” are followed by something like an accent sign, similar to the Russian “iso” (῎).

27 Although the second letter combination is clearly written in the form “ßcża,” the writer apparently did not have in mind the German letter ‹ß› (=[s]) but rather the Polish digraph ‹ſz/sz›, [ʃ], thus ‹szcża›, which then would have been an acceptable approximation to the pronunciation of the Russian letter name “ща.”

28 The letter ‹ж› has a very unusual form, which I had never seen before. It looks like an “unfinished” ‹ж› (see ). I am indebted to Sebastian Kempgen, who has helped me to identify this form as a South Slavic – more exactly Bosnian – variant of ‹ж›; see Truhelka Citation1889, 3 and Kempgen Citation2015, 284, 285. (The last letter in this word is very similar to a Latin ‹z›, which would not make sense in this “Russian” word, so I have read it as ‹e›).

29 I am grateful to Johan Heldt and Marianne Wifstrand Schiebe for sharing their ideas about this short text with me.

30 Apparently, the author was using the two ‹j› letters for two different sounds, the first one to be pronounced like a German ‹j›, that is [j]; the second one as a French ‹j› ([ʒ]), so the result will be [jeʒe]. Presumably, the second instance of the letter ‹j› was underlined in order to signal that the pronunciation is not similar to the first instance of the letter.

31 Hiob Ludolf’s Stammbuch (kept at HAAB) does not contain much text written by him; his Reysebüchlein (Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, Weimar) is written in German Kurrent script, except foreign names, loanwords etc., so there was not much text to compare. (Both manuscripts are available via the HAAB catalogue.) I am very grateful to Héctor Canal Pardo, who has compared the additions in brown ink with documents written by Hiob Ludolf, kept at the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv (for instance, draft letters).

32 Cf., for instance, H. W. Ludolf’s entry in his diary from 13 May 1711 in Latin (fol. 203; available via Franckesche Stiftungen in Halle; direct link: https://digital.francke-halle.de/fsha/content/pageview/617793).

33 Signature: Loc A: 56.1. The entry about Van Selow’s catechism is on fol. 286v.

34 E-mail from Katja Lorenz, 15 Feb. 2021.

35 The information about King Gustavus and Ingria was taken from the handwritten “preface” added to the printed book, which I attribute to Rinhuber.

36 The best and most complete summary about Rinhuber’s life is Dumschat Citation2006, 426–441, 666–68 (short biography), but see also Brikner Citation1884; Brückner Citation1884; Pierling Citation1893.

37 In his letter to Duke Ernst of Saxe-Gotha, datelined Dresden, 10 March 1673, he writes: “Patria est Luccau, Misniæ oppidulum.” My transcription is from Rinhuber’s original document, kept in the Gotha archive (see note 6). This letter is published in Rinhuber Citation1883 (the quotation – where the spelling of the place name is Lucau – is on p. 26; the publication is based on a copy of Rinhuber’s letter).

38 The date, 7 June, is according to Dumschat Citation2006, 438 (based on archival documents); the date 6 July given by Brikner (Citation1884, 414) is apparently wrong, as are several other dates in his study.

39 Dumschat Citation2006, 439; see also Rinhuber’s own report in Rinhuber Citation1883, 223–31.

40 One occasion to do so was in May 1683, when Rinhuber visited Ludolf in Erfurt. Cf. Ludolf’s letter to the duke of Saxe-Gotha from Erfurt, 15 May 1683: “Sonsten ist der Dr. Rinhuber bey mir ankommen, undt hat mir sein Vorhaben nach Moßkau u. Persien auch weiter zureysen eröffnet, auch die Schreiben von Chur Sachsen und E.F.Dhl. [=Euer Fürstl. Durchlaucht] gezeiget […]” (Forschungsbibliothek Gotha, Chart. A 102, fol. 170). The letter is published in Rinhuber Citation1883, 195–196.

41 Cf. Cvetaev Citation1889, 6 (who erroneously gives the year 1626 for the Stockholm catechism). At least one more copy – the one kept in Stuttgart – can also be traced to Moscow (see Maier, Citationforthcoming).

42 HAAB, Hs. Fol. 426e. The fragment contains Act 2 of the play (partially with the original German text added in the margins or between the lines of the Russian text). For details about Rinhuber’s additions to this manuscript see the forthcoming monograph by Claudia Jensen and Ingrid Maier, dedicated specifically to the first play of the Russian court theatre, the Esther play.

References

- Bogojavlenskij, S. K. 1914. “Moskovskij teatr pri Carjach Aleksee i Petre.” Čtenija v Obščestve istorii i drevnostej rossijskich 2:1, iii–xxi, 1–192.

- Brikner, A[leksandr]. 1884. “Lavrentij Ringuber.” Review of Relation du voyage en Russie fait en 1684 par Laurent Rinhuber (Berlin 1883). Žurnal ministerstva narodnogo prosveščenija (Fevral’ 1884):396–421.

- Brückner, Alexander. 1884. “Laurentius Rinhuber. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte Rußlands im 17. Jahrhundert.” Historische Zeitschrift 52, N.F. 16:193–253.

- Collijn, Isak. 1913. “Der in Stockholm gedruckte russische Catechismus aus dem Jahre 1628.” Archiv für slavische Philologie 34:246–51.

- Cvetaev, C. V. 1889. “Pervye nemeckie školy v Moskve i osnovanie pridvornogo nemecko-russkogo teatra.” Varšavskie universitetskie izvestija VIII:1–24.

- Droste, Heiko and Ingrid Maier. 2010. “Från Boris Godunov till Gustav II Adolf: översättaren Hans Flörich i tsarens och svenska kronans tjänst.” Slovo. Journal of Slavic Languages and Literatures 50:47–66.

- Dumschat, Sabine. 2006. Ausländische Mediziner im Moskauer Rußland. Stuttgart: Steiner (= Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte des östlichen Europa. 67).

- Ďurovič, Ľubomír. 2003. “Russisch und Kirchenslavisch in Gustav Adolfs Schweden.” In Rusistika. Slavistika. Lingvistika. Festschrift für Werner Lehfeldt zum 60. Geburtstag (Die Welt der Slaven. Sammelband 19), edited by S. Kempgen, U. Schweier, and T. Berger, 99–108. München: Otto Sagner,

- Jensen, Alfred. 1912. “Die Anfänge der schwedischen Slavistik.” Archiv für slavische Philologie 33 (1912):136–165.

- Jensen, et al. 2021. Claudia Jensen, Ingrid Maier, Stepan Shamin, with Daniel C. Waugh. Russia’s Theatrical Past: Court Entertainment in the Seventeenth Century (Russian Music Studies). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Kempgen, Sebastian. 2015. Slavic Alphabet Tables. Vol. 2 (1527–1956) (Bamberger Beiträge zur Linguistik 12). Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press.

- Kirstenius, Petrus. 1608. Grammatices arabicae, liber I. Sive orthographia et prosodia arabica. Breslau: Baumann.

- Ludolf, Hiob. 1681. Historia Aethiopica. Frankfurt am Main: B. C. Wust for J. D. Zunner.

- Maier, Ingrid. 2012. “Wer war der Autor von Alfabetum Rutenorum (Stockholm ohne Jahr)?” Schnittpunkt Slavistik. Ost und West im wissenschaftlichen Dialog: Festgabe für Helmut Keipert zum 70. Geburtstag. Teil 3: Vom Wort zum Text. Göttingen: Bonn University Press, 333–357.

- Maier, Ingrid.. 2021. “Russian Pronunciation Rules in the Alphabetum Russarum.” Slovo. Journal of Slavic Languages and Literatures 62:39–60.

- Maier, Ingrid.. 2022. “Did Peter van Selow (1582–1650) Have Dutch Roots? New Sources about a Well-known Type Founder and Printer.” Jaarboek voor Nederlandse boekgeschiedenis / Yearbook for Dutch Book History 29:235–264.

- Maier, Ingrid.. Forthcoming. Lutheran Catechisms in Russian Translation “made in Sweden” (1628–1701).

- Mazon, André and Frédéric Cocron. 1954. “La Comédie d’Artaxerxès” (Артаѯерѯово дѣйство) présentée en 1672 au Tsar Alexis par Gregorii le Pasteur. Paris: Institut d’Études slaves de l’Université de Paris.

- Nyholm, Alf. 1996. Två “svenska” lutherska katekeser på ryska. Uppsala: Slaviska institutionen, Uppsala universitet [Licentiate dissertation].

- Olearius, Adam. 1656. Vermehrte Newe Beschreibung Der Muscowitischen und Persischen Reyse […]. 2nd ed. Schleßwig: Johan Holwein.

- Pereswetoff-Morath, Alexander I. 2010. “Isaak Torčakov och diakerna: kring den äldre svenska slavistikens historia.” Slovo. Journal of Slavic Languages and Literatures 51:7–32.

- Pereswetoff-Morath, Alexander I.. 2012. “Isaak Torčakov: en ingermanländsk diak.” In Novgorodiana Stockholmiensia, edited by E. Löfstrand and Gennadij Kovalenko, 80–110. Stockholm: Slaviska institutionen, Stockholms universitet.

- Pierling, Paul. 1893. Saxe et Moscou. Un médecin diplomate. Laurentius Rinhuber de Reinufer. Paris: Émile Bouillon.

- Rinhuber, Laurent. 1883. Relation du voyage en Russie fait en 1684. Berlin: Albert Cohn.

- Rudbeck, Gustaf. 1925. “Peter van Selow stilgjutare och boktryckare i Stockholm 1618–1648.” Bok- och bibliotekshistoriska studier tillägnade Isak Collijn på hans 50-årsdag, edited by Axel Nelson, 303–334. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Sebestyén, Gyula. 1903. “Telegdi János 1598-iki Rudimentájának hamburgi és marosvásárhelyi kézirata.” [Manuscript of János Telegdi’s Rudimenta of 1598 in Hamburg and Târgu Mureş. Magyar könyvszemle [Hungarian Book Review, N.F.] 11 (3):247–280.

- Sebestyén, Gyula.. 1915. A magyar rovásirás hiteles emlékei [Authentic Monuments of Hungarian Runic Writing]. Budapest: Kiadja a Magyar Todományos Akadémia.

- Sjöberg, Anders. 1975. “Luthers katekes på ryska och Alfabetum Rutenorum (Två ryska tryck från början av 1600-talet).” Kring den svenska slavistikens äldsta historia (Slavica Lundensia, 3), edited by Ľ. Ďurovič, 9–25. Lund: Slaviska institutionen vid Lunds universitet.

- Sjöberg, Anders.. 1984. “Hans Flörich och Isak Torcakov, två ‘svenska’ rusister i början av 1600-talet.” In Äldre svensk slavistik. Bidrag till ett symposium hållet i Uppsala 3–4 februari 1983 (Uppsala Slavic Papers 9), edited by Sven Gustavsson and Lennart Lönngren, 25–35. Uppsala: Slaviska institutionen vid Uppsala universitet.

- Svenskt biografiskt lexikon. 1945. Bd. 11. Stockholm: Svenskt biografiskt lexikon.

- Tarkiainen, Kari. 1974. “Den tidiga kyrkliga slavistiken i Sverige.” Kyrkohistorisk årsskrift 74:71–96.

- Truhelka, Ćiro. 1889. “Bosančica. Prinos bosanskoj paleografiji od dra Ćire Truhelke.” Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Bosni i Hercegovini. Godina I. Knjiga I, 65–83. Sarajevo: Zemaljska štamparije.

![Figure 4. Pp. [2]–[3] of the handwritten appendix.](/cms/asset/a8569583-193d-4032-b5c2-712e41c5f443/ssla_a_2270944_f0004_oc.jpg)

![Figure 5. Page [4] of the handwritten appendix.](/cms/asset/069fd8f5-6e8f-44a0-a1ce-3974f7b62519/ssla_a_2270944_f0005_oc.jpg)

![Figure 2. Fol. [2] r-v of the Alphabetum Russarum.](/cms/asset/86761251-0945-4291-aafb-5c3926a4d79c/ssla_a_2270944_f0002_oc.jpg)