?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the salience of five phonological variables: pre-sonorant voicing, nasal stopping, nasal assimilation, the czy-trzy merger, and denasalization in Greater Poland Polish. We elicited both production (audio recordings) and perception (psycholinguistic study) data from 65 participants. On this basis, we categorize the five variables with regard to the stereotype - marker - indicator scale suggested by Labov (1972). Nasal stopping and the czy-trzy merger are the most salient and the most negatively judged, suggesting they are stereotypes; pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation attract little attention, suggesting they are indicators; denasalization is associated with little agreement among the participants as to its acceptability and is avoided in formal speech, suggesting it is a marker, with the caveat that denasalization is not restricted to Greater Poland Polish.

0. Introduction

Considering linguistic variation, some variants may be perceived as more salient than others. Social salience, as defined by Preston (Citation2011, 10) is the “[attribution of] non-specialist belief about and reaction to language use, structure, diversification, history, and status.” In this paper, we investigate the salience of a selection of features of Greater Poland Polish by looking at production data and at elicited judgments. Our aim is to harness both production and perception data to shed light on the salience of the selected features, as well as to find out whether overt judgments match participants’ productions. The variables we consider are (1) pre-sonorant voicing (e.g. the realization of brat rodzony ‘natural brother’ as [brad rɔd͡zɔnɨ]) (2) nasal stopping (e.g. the realization of siedzą ‘they are sitting’ as [ɕεd͡zɔm]) (3) nasal assimilation (e.g. the realization of panienka ‘miss’ as [paɲεŋka]), (4) the czy-trzy merger (e.g. the realization of both trzy ‘three’ and czy ‘whether’ as [t͡ʂɨ]), and (5) denasalization (e.g. the realization of idę ‘I’m going’ as [idε]).

Since the bulk of the pioneering theory and empirical research in sociolinguistics has been conducted on English, our introduction relies heavily on sources on English.

In his model of social salience, Labov (Citation1972) suggested a taxonomy of variables based on the level of awareness in a community: variables that speakers are the least aware of and that involve no stylistic stratification, the so-called “indicators,” variables that are on the level of awareness of social meaning and that are subject to style shifting – “markers,” and variables that demonstrate overt social awareness – “stereotypes.” For example, in his sociolinguistic interviews, Trudgill (Citation1986, 7–11) found that in Norwich English, T-glottaling (the use of glottal stop for syllable-final /t/) is a marker since over the course of the interview he accommodated the use of this feature to his interlocutor. On the other hand, he did not modify the degree of fronting or backing of /aː/, which suggests that the variable /aː/ was an indicator. There are also researchers who consider social salience to be a dynamic process depending on different properties of speakers, situational cognitive load, or a situation in which a given variant is encountered (Preston Citation2010; Citation2011). For example, in their experiment on sociolinguistic salience of different variables in a Scottish/English boundary zone, Llamas et al. (Citation2016) found that perception was indicative of production; the tendency in Scottish English to avoid the realization of /r/ in coda positions was mirrored in perception since /r/ in coda positions was not frequently matched to the category “Scotland.” As Llamas et al. (Citation2016, 15) conclude, “the strength of their socio-indexical value as seen through the lens of shared social meaning dictates how salient the forms will be. As production patterns change, so may the agreed social meaning of the form”. Salience of a given variant may be determined on the basis of a set of criteria. For example, a given variant may be categorized as a marker if it is a high prestige variant, a stigmatized variant, if the variable is undergoing linguistic change, if there is a phonetic distance between variants, or if there is phonological contrast between variants (Trudgill Citation1986, 11). Of particular interest may be the impact of highly salient forms, defined as the ones which “index social information more unequivocally than do forms with lower salience” (Llamas, Watt, and MacFarlane Citation2016, 2), on language variation and change. Trudgill (Citation1986) argues that in dialect contact situations high salience inhibits the acquisition of new features.

Salience is considered to be a dynamic, multidimensional property that evolves over time. Preston (Citation2010; Citation2011), for example, differentiates four stages of assigning social salience to linguistic forms: noticing, classifying, imbuing (e.g. associating a variant with positive or negative features), and reaction, which is given most attention in language attitude studies since it reveals secretly coded information about the speaker as well as the recipient. To take one example, “an American may think a stranger ‘cultured’ and ‘refined’ simply because his or her accent is deemed British” (Cargile and Giles Citation1998, 338). Speakers who use standard forms are usually perceived as being more intelligent and having higher socioeconomic status, while those using non-standard forms are perceived as kinder and more attractive, a case in point being speakers of RP in America who are generally considered to have a higher status, but believed to be conservative and less attractive (Cargile and Giles Citation1998, 340–342). It may also happen that the same variant is perceived differently by different listeners. For example, in her study on the English variable ING, Campbell-Kibler (Citation2008) found that the speaker who used the standard velar variant was perceived by some as intelligent, while others believed the speaker to be deliberately making an impression on listeners. Thus, to some listeners, this pronunciation had also some negative connotations.

1. Factors Influencing Speech Perception

How listeners perceive speech is dependent on numerous sociolinguistic factors, a good case in point being location. There is a plethora of studies dealing with the identification of the regional dialects of speakers. Clopper and Pisoni (Citation2004), for example, asked people from Indiana to determine which region of the United States the speakers they heard came from. They observed that identifications were based on the recognition of dialectal variants such as r-lessness or vowel qualities. Jansen (Citation2014) explored salience effects in the Carlise dialect. Among her variants of interest was TH-fronting, which is the realization of /θ/ as /f/, and /ð/ as /v/. She found that despite being attested in the Carlise dialect, TH-fronting was associated with London/Cockney speech, not the Carlise dialect, which means that this dialectal variant operates under the level of consciousness. Levon and Fox (Citation2014) examined social salience of two variables: ING and TH-fronting. When it comes to ING, British listeners did not perceive the alveolar variant as less professional, even though the variable has reached the level of awareness. In the case of TH-fronting, while Northern listeners perceived increased fronting as less professional, Southern listeners displayed no such sensitivity. Llamas et al. (Citation2016) wanted to find out how people from a Scottish/English border region differed in categorization of some variables as being Scottish or English. They found that Scottish listeners proved to be more accurate in terms of association between “high consensus forms” (forms that yielded a high level of consensus among community members) and region (England/not England/Scotland/not Scotland) than English listeners.

Of particular interest may also be the impact of the speakers’ location, gender, education, or age on their use of regional and standard variants. For example, in a survey on the use of regional dialects, Hansen (Citation2014) found that in Poland, speakers from smaller towns and villages declared using their regional accents more frequently than speakers from larger urban centers. The willingness to preserve the regional accent was also reported more frequently by less educated speakers and men. Paltridge and Giles (Citation1984) focused on the perception of four different accents of French by male and female judges. It turned out that Brittany-accented speakers were rated as less positive in terms of “professional appeal” by men, while in terms of “social appeal” it is women who more positively judged Parisian-accented speakers. Bergstorm (Citation2017) investigated the impact of age, dialect, and gender on the perception of the personality of speakers – New Zealanders and Utahns. It turned out that older speakers were perceived as more credible than young and middle-aged groups of speakers. In terms of dialect, New Zealanders were rated as more pleasant and more prestigious, and in terms of gender, women tended to rate male speakers as more prestigious. Bergstorm observed that not only the speaker’s but also the listener’s gender influenced the perception. As she says, “[i]rrespective of the age, dialect, and gender of the speaker, women tended to be more favorable in their perceptions of 26 speakers when compared to men” (Bergstrom Citation2017, 25–26).

2. Variables in Greater Poland Polish

Participants of the current study come from Poznań (a major Polish city in the West of the country) and surrounding areas. As such, they can be thought of as speakers of Greater Poland Polish, a variety long recognized to have features distinct from standard Polish (the latter having its major source in Warsaw speech). Among the characteristic features of Greater Poland Polish, Witaszek-Samborska (Citation1985, 31) lists the realization of word-final obstruents as voiced when the following word begins with a sonorant (henceforth pre-sonorant voicing), the realization as [ɔm] (henceforth nasal stopping) of the word-final structure represented by the letter <ą> in the spelling (corresponding to the historical nasal vowel */ɔ̃/), the realization of the post-dental nasal /n/ as a velar nasal [ŋ] (henceforth nasal assimilation) when followed by /k/ across a morpheme boundary, and the realization of the plosive-fricative cluster /tʂ/ as an affricate [t͡ʂ] (henceforth czy-trzy merger), as widespread features of this Polish variety. The realization of the word-final structure represented by the letter <ę> in the spelling (corresponding to the historical nasal vowel */ε̃/) as an oral /ε/ (henceforth denasalization), though not restricted to Greater Poland Polish, is certainly present in it (Baranowska and Kaźmierski Citation2020), and as such it completes the list of variables investigated in this paper. For a phonologically-oriented treatment of these variables, see e.g. Gussmann (Citation2007).

2.1 Pre-sonorant Voicing

Pre-sonorant voicing is a process of voicing word-final obstruents in the context where the following word begins with a vowel or a sonorant consonant (Dejna Citation1973), e.g. brat rodzony ‘natural brother’ is realized as [brad rɔd͡zɔnɨ] (Strycharczuk Citation2012, 71–72) (cf. standard Polish [brat rɔd͡zɔnɨ]). Early accounts (e.g. Bethin Citation1984) treat the process as a case of regressive assimilation. Andersen (Citation1986) provides a diachronic account which sees the origins of pre-sonorant voicing in the way in which an earlier “protensity” contrast was reinterpreted as a voicing contrast. Cyran (Citation2012) rejects the notion that sonorants spread voicing and trigger pre-sonorant voicing since sonorants cannot be specified for voicing. Instead, he suggests that word-final obstruents are subject to ‘spontaneous voicing,’ meaning that word-final obstruents in Greater Poland Polish are not specified for voicing. Settling the issue of the diachronic origins, or of the best synchronic characterization of pre-sonorant voicing, is beyond the scope of this paper. We are solely investigating the salience of this feature.

There is much experimental evidence of the existence of pre-sonorant voicing in Greater Poland Polish. Witaszek-Szymborska (Citation1985) found it to be widespread, used by speakers from all three age groups she investigated. Similarly, Strycharczuk (Citation2012) found pre-sonorant voicing to be frequent in the speech of 6 female speakers from Poznań, but not in that of 6 female speakers from Warsaw. Wojtkowiak and Schwartz (Citation2018) attest it in the speech of ten speakers from Oborniki Wielkopolskie, a small town north of Poznań. Kaźmierski et al. (Citation2019), investigating the speech of 14 speakers from Poznań, found that they voiced 42% of word-final pre-sonorant obstruents (301/723 tokens). The difference between Strycharczuk’s (Citation2012) result, with pre-sonorant voicing being less frequent than pre-obstruent voicing, and Wojtkowiak and Schwartz’s (Citation2018) results, with equal frequencies, might suggest that the more highly educated speakers of Strycharczuk’s (Citation2012) study are avoiding pre-sonorant voicing. Based on that, as well as on our knowledge of forms with pre-sonorant voicing being overtly stigmatizedFootnote1, we tentatively categorize pre-sonorant voicing as a non-standard process, even though normative descriptions tend to see it as a feature of one of the two standard norms of Polish.

2.2 Nasal Stopping

In standard Polish, the reflex of the historical nasal vowel */ɔ̃/ (represented by the letter <ą> in the spelling) is typically realized as a nasalized diphthong [ɔw̃] (Zaleska and Nevins Citation2015), that is a sequence of the oral vowel [ɔ] and a nasalized labio-velar consonant [w̃] when it occurs before fricatives word-internally e.g. wąsy [vɔw̃sɨ] ‘moustache,’ as well as in word final position idą [idɔw̃] ‘they are going,’ or a nasalized palatal glide [j̃] when it occurs before alveolo-palatal fricatives e.g. ukąsi [ukɔj̃ɕi] ‘will bite.’ However, word-internally before stops, orthographic <ą> corresponds to a sequence of an oral vowel [ɔ] and a nasal consonant homorganic with the following stop, e.g. kąp [kɔmp] ‘bathe.imp,’ kąt [kɔnt] ‘corner,’ pąk [pɔŋk] ‘bud’ (Lorenc et al. Citation2018). Interestingly for this paper, in Greater Poland (and in southwest and central Poland more broadly), the phonological material represented by orthographic <ą> may be realized as an oral vowel followed by a nasal stop [ɔm] in word-final position, e.g. siedzą (‘they are sitting’) [ɕεd͡zɔm] contrasting with the standard realization [ɕεd͡zɔw̃] (Dubisz, Karaś, and Kolis Citation1995, 114). Further examples include: robią ‘they are doing’ [rɔbjɔm] ∼ [rɔbjɔw̃], małą ‘small.fem.ins’ [mawɔm] ∼ [mawɔw̃], drogą ‘road.ins’ [drɔgɔm] ∼ [drɔgɔw̃]. Let us refer to the [ɔm] realization of word-final orthographic <ą> as nasal stopping. Witaszek-Samborska (Citation1985) classified nasal stopping as widespread, while a later study (Kaźmierski, Kul, and Zydorowicz Citation2019) found nasal stopping in only 25% of tokens. Previous research reveals how nasal stopping may be dependent on sociolinguistic factors. For example, Baranowska and Kaźmierski (Citation2020) investigated the impact of age, gender, education, location, and style. They found that the rate of nasal stopping increased with the age of speakers. Moreover, a statistically significant association was found between nasal stopping and education, since speakers with higher education had the tendency to realize /ɔ̃/ as [ɔm] less frequently than speakers with elementary education. This education-driven and age-driven stratification might suggest that nasal stopping is salient and avoided.

2.3 Nasal Assimilation

Across Polish dialects, in morpheme-internal /nk/ sequences dental /n/ undergoes assimilation to velar [ŋ], e.g. punkt ‘point’ [puŋkt]. A dental /n/ occurring before /k/ across a morpheme boundary, however, remains dental in Warsaw speech: panienka ‘miss’ [paɲεn̪ + ka] (Ostaszewska and Tambor Citation2000, 86; Kaźmierski, Kul, and Zydorowicz Citation2019). Since recovering morpheme boundaries in Polish may be non-trivial, Klemensiewicz (Citation1965, 37) reformulates the environment for the blocking of this assimilation without reference to morpheme boundaries and states that in Warsaw speech, /n/ remains dental whenever /n/ and /k/ are separated in inflected forms of the same word, or any other related words, e.g. panienka ‘miss-nom.sg’ – ‘panienek’ ‘miss-gen.pl’; rynku ‘market-gen.sg’ ∼ rynek ‘market-nom.sg.’ This limit on nasal assimilation is notably absent from Greater Poland Polish. In Greater Poland Polish, /n/ in this position does assimilate to the following velar, i.e. panienka [paɲεŋ+ka] ‘miss’ (Ostaszewska and Tambor Citation2000, 86; Kaźmierski, Kul, and Zydorowicz Citation2019). Further examples include Irenka ‘Irene.dim’ [irεŋ+ka] ∼ [irεn̪ + ka], sarenka ‘doe.dim’ [sarεŋ+ka] ∼ [sarεn̪ + ka], and wisienka ‘cherry.dim’ [viɕεŋ+ka] ∼ [viɕεn̪ + ka]. While variants with nasal assimilation are also accepted as the standard in some normative descriptions which treat Polish as having two standard norms (e.g. Madejowa 1992; Dunaj Citation2006), given the reasons presented for pre-sonorant voicing above for suspecting that local Greater Poland Polish features are not treated as standard, we again tentatively categorize nasal assimilation for the purposes of this paper as non-standard.

This velar realization of nasals before velar consonants across morpheme boundaries has been found to be characteristic of Greater Poland Polish in various experimental studies (Witaszek-Samborska Citation1985; Kaźmierski, Kul, and Zydorowicz Citation2019) since the variant was frequently produced by speakers from the dialect area. For example, in Kaźmierski et al’s study (Citation2019), nasal assimilation was found in 71% of tokens (37/52). We are not aware of any experimental evidence pertaining to the salience of this feature.

2.4 The czy-trzy Merger

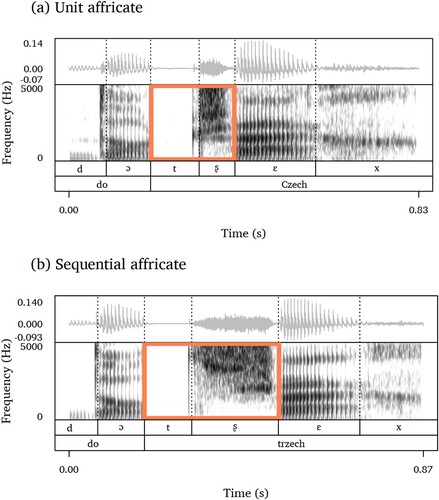

Standard Polish maintains a contrast between the /tʂ/ plosive-fricative sequence e.g. trzy /tʂɨ/ ‘three’ and the affricate /t͡ʂ/ e.g. czy [t͡ʂɨ] ‘whether.’ Phonetically, the contrast is often maintained in the form of an opposition between an affricate-fricative sequence, e.g. trzy [t͡ʂʂɨ] ‘three’ and a sole affricate, e.g. czy [t͡ʂɨ] ‘whether.’ Zagórska-Brooks (Citation1964) found acoustic evidence for the difference in the realization of the two structures. In her study, two native speakers of Polish recorded a list of minimal pairs contrasting the plosive-fricative sequence and the affricate in word initial, medial, and final position, e.g. Czech [t͡ʂεx] ‘Czech man’ vs. trzech [t͡ʂʂεx] ‘three’ (our transcription). The acoustic analysis revealed, inter alia, that what differentiated the ‘unit affricate’ [t͡ʂ] from the ‘sequential affricate’ [t͡ʂʂ] the most was the length of the fricative constituent [ʂ], which was relatively longer in the ‘sequential affricate’ [t͡ʂʂ] as in trzech ‘three’ (as reflected in our adapted transcription). This is illustrated in , which visualizes the first author of the present paper pronouncing do Czech ‘to Czechia’ [dɔ t͡ʂεx] with a unit affricate (top panel) and do trzech ‘to three’ [dɔ t͡ʂʂεx] with a sequential affricate (bottom panel). As in Zagórska-Brooks’ data, the first constituent of the affricate has a similar duration in either case, while the second constituent is considerably longer in the sequential affricate (do trzech, bottom panel) than in the unit affricate (do Czech, top panel).

Figure 1. Waveforms and spectrograms of the first author pronouncing do Czech (a), top panel, and do trzech (b), bottom panel. Re-creation of one example from Zagórska-Brooks (Citation1964).

Greater Poland Polish is known to neutralize this brittle contrast: e.g. both trzy ‘three’ and czy ‘whether’ may be realized with the unit affricate [t͡ʂɨ]). Further examples of words which may have the unit affricate [t͡ʂ] in Greater Poland Polish (but not in other varieties) include trzymać ‘hold’ [t͡ʂɨmat͡ɕ], potrzebować ‘need’ [pɔt͡ʂεbɔvat͡ɕ], and patrz ‘look.imp’ [pat͡ʂ]. Witaszek-Samborska (Citation1985) characterized this czy-trzy merger as widespread in Greater Poland Polish, as it was used by speakers of all age groups. Kaźmierski et al. (Citation2019) attest it in a mere 23% of tokens (21/92). The direction of the merger, i.e. towards the unit affricate rather than the sequential affricate, could potentially be driven by ease of articulation: the longer fricative of a sequential affricate arguably involves more articulatory effort than the shorter one of a unit affricate.

2.5 Denasalization

The word-final reflex of the historical vowel */ε̃/ represented by <ę> in the spelling, for example in words like idę ‘I’m going,’ has two common realizations: it can be realized with a nasalized glide [εw̃], here: [idεw̃], or denasalized to an oral vowel [ε], here: [idε]. Other examples include: kartę ‘card.acc’ [kartεw̃] ∼ [kartε], mogę ‘I can’ [mɔgεw̃] ∼ [mɔgε], nogę ‘leg.acc’ [nɔgεw̃] ∼ [nɔgε]. There is no consensus as to which variant is more standard and more prestigious. Some (e.g. Zajda Citation1977) regard [ε] as less prestigious than [εw̃]. At the same time, because of its prevalence, denasalization could be considered as standard (Dunaj Citation2006, 163), while the realization of /ε̃/ as [εw̃] as “unnatural” (Karaś Citation1977)Footnote2.

Denasalization may be subject to sociolinguistic variation. Johnson (Citation1984) found that speakers from a higher social class opted for the [εw̃] variant. On the other hand, a recent study (Baranowska and Kaźmierski Citation2020) found that speakers with higher education had higher rates of denasalization than speakers with elementary education, which lends support to the recognition of denasalization as a standard variant. However, denasalization was more prevalent in the more informal of the two speech styles elicited in the study, which implies that speakers still perceive denasalization as less prestigious, since they avoid it in controlled speech (Baranowska and Kaźmierski Citation2020); spelling apparently affects the language users’ perceptions of correctness, as <ę> and <e > are distinct orthographic entities, linked to two distinct realizations.

3. Research Questions

With our empirical studies, we aim to address the following research questions:

Which of the five variables of Greater Poland Polish can be regarded as indicators, markers, and stereotypes?

Is there any relationship between speakers’ overt judgments and their productions?

We hypothesize that regional variants will be judged as less correct than their standard counterparts. Nasal stopping and the czy-trzy merger result in hypercorrection. Words spelled with <cz>, that is words containing the unit affricate [t͡ʂ] are occasionally pronounced with the sequence [tʂ], as if they were spelled with <trz>Footnote3. Similarly words ending in orthogrhaphic <om>, i.e. words ending in the [ɔm] sequence, are occasionally pronounced with [ɔw̃], as if they were spelled with <ą>Footnote4. Hypercorrection suggests overt social awareness of these variables, and so we predict these two variables to serve as stereotypes, while the others may be considered as indicators. Finally, since perception exerts an influence on production, we believe that speakers who judge a given variant as incorrect may not produce it because of being aware of little prestige that the non-standard variant carries, and because the production task is a word-list reading task which elicits very careful speech, allowing speakers to exert greater control over the variants they use.

4. Method

4.1 Participants

The participants were 65 students at Wyższa Szkoła Bezpieczeństwa (Private University of Security) in Poznań. There were 42 women and 23 men, aged between 19 and 46 (mean = 24.8, sd = 5.5). All participants were native speakers of Polish living in Greater Poland. They were all extramural students of psychology, national security, or health security.

4.2 Materials

A questionnaire consisting of 12 questions was prepared. The first part of the questionnaire elicited sociolinguistic data, such as age, gender, education, place of residence, mobility, and hand dominance. The second part of the questionnaire asked about participants’ opinions concerning the use of regional accents. The original questionnaire is available as Appendix 1, its English translation as Appendix 2.

We selected five variables to investigate their salience in Greater Poland Polish. Four of them are well-known features of Greater Poland Polish (Witaszek-Samborska Citation1985; Kaźmierski, Kul, and Zydorowicz Citation2019): pre-sonorant voicing, nasal stopping, nasal assimilation, and the czy-trzy merger. Additionally, we included a fifth variable: denasalization. Baranowska and Kaźmierski (Citation2020) found that denasalization may not be considered standard in Greater Poland Polish since speakers avoid it in formal style; however, in informal style, denasalization is frequent, particularly in the speech of highly-educated speakers. Thus, we believe that the salience of denasalization in the Poznań dialect is worth investigating.

The token frequency of words and phrases that served as stimuli was controlled for by means of frequency lists based on the SUBTLEX-PL corpus (Mandera et al. Citation2015). Each of the five variables was represented by four words or phrases (giving a total of 20 test items). To distract participants from focusing on the test variables, we added two filler variables: the palatalization of /g/, in e.g. inteligenty [intεligεntnɨ] ‘intelligent’ to [intεliɟεntnɨ], and the retention of voiced /v/ after voiceless consonants, e.g. twój [tfuj] ‘yours’ realized as [tvuj]. The final list of stimuli consisted of 28 items (20 test items + 8 fillers): rzut oka, świat oszalał, zbyt ostry, nawet oni; będą, mają, twoją, mogą; sukienka, panienka, panienko, łazienka; trzecie, trzymać, strzały, patrz; muszę, idę, robię, piszę; inteligentny, generał, geniusz, agenci; stworzenia, twój, oszustwo, łatwo.

For the second part of the study, the perception experiment, each word or phrase was included in two versions: standard and Greater Poland Polish. The stimuli were recorded using a USB microphone connected to a laptop computer. They were spoken by 18 native speakers of Polish, who were asked to read each word/phrase naturally. Afterward, we chose one token of the standard variant, and one token of the Greater Poland Polish variant for each of the five variables. No more than three tokens produced by the same speaker were used. No two variants of the same word/phrase produced by the same speaker were used, not to inflate type I error rate and to ensure the ecological validity of the results (cf. Winter Citation2015). Desilenced recordings were high-pass filtered at 300 Hz with smoothing at 100 Hz using PraatR (Albin Citation2014). Consequently, the length of the recordings was normalized to 600 ms with a Praat (Boersma Citation2018) script. In total, 56 stimuli were presented to the participants in the perception experiment: seven variables (five test variables) * four items * two variants.

4.3 Procedure

Participants began by filling out consent forms and questionnaires. Not to bias participants with the perception experiment, the production part came first. Each participant read aloud all test words/phrases and fillers into the microphone plugged into a laptop computer. The stimuli were presented visually in a pseudo-randomized order with the Speech Recorder software (Draxler and Jänsch Citation2004).

The subsequent perception test was divided into a training block and a test block. All instructions were presented on a computer screen. Each stimulus was played back over headphones, after which a response was provided with the keyboard: either poprawny ‘correct’ or niepoprawy ‘incorrect.’ The stimuli were played back in isolation; they were not embedded in any carrier sentences or phrases. The responses, as well as the reaction times of the responses, were recorded. The order of stimuli within each block was randomized. To control for hand dominance effects, halfway through each block the value assigned to the two response keys was switched, with an instruction screen informing of the change. The test was implemented in PsychoPy v3.2.4 (Peirce et al. Citation2019).

4.4 Data Screening

For the perception test results, all data points with reaction times above 5 seconds (7 cases) and below 0.5s (3 cases) were removed. This has brought the original N of 2730 down to 2720.

4.5 Statistical Analysis

Data transformation, visualization, and modeling were conducted primarily by means of the dplyr (Wickham et al. Citation2017), ggplot2 (Wickham Citation2016) and lme4 (Bates et al. Citation2015) packages respectively, all being extensions of the R statistical environment (R Core Team Citation2022).

For the linear mixed-effects model of reaction times from the perception test, the response variable was transformed from reaction time (RT) to its inverse, 1/RT, which can be construed as processing speed. This transformation has been shown to reduce the skewness of residuals before (cf. Kliegl, Masson, and Richter Citation2010; Baumann and Kaźmierski Citation2018), and it has done so with the present data set as well.

5. Results

We begin by presenting the results of the perception study, including the categorization of variants into ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’, as well as the processing speed of the responses. We then present results of the production study, after which we juxtapose participants’ productions with their categorizations.

5.1 Perception

5.1.1 Categorization

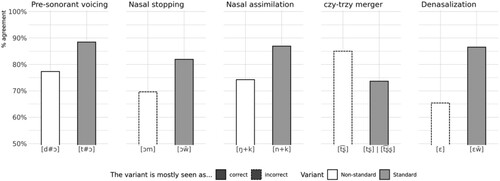

lays out the categorization of responses by variable by variant. For the czy-trzy merger, denasalization, and nasal stopping, the non-standard variant was mostly judged as incorrect (in 80%, 70%, and 65% of cases, respectively), while the standard variant was mostly judged as correct (in 73%, 83%, and 87% of cases, respectively). However, for the remaining two variables, pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation, the non-standard variant was mostly judged as correct (78% and 65% respectively), and the standard variant was mostly judged as correct as well (in 88% and 74% of cases, respectively).

The above suggests that the participants are aware of the different variants of the czy-trzy merger, denasalization, and nasal stopping, and that they see the standard variants as considerably more correct. This suggests high salience of these three variables, and the perception of their non-standard variants as incorrect. While standard variants are rated as correct slightly more often than non-standard variants are for nasal assimilation and pre-sonorant voicing, in the case of these two variables, most of the time the non-standard variant is seen as correct as well. These two variables, then, seem to be less salient.

shows agreement among the participants in categorizing the 10 variants. If the variant was predominantly (> 50%) seen as correct, then % agreement is the percentage of “correct” categorizations. Otherwise, it is the percentage of “incorrect” categorizations. Therefore, in each case the base line is 50%, which would mean that the number of participants who rated this variant as correct was the same as the number of participants who rated it as incorrect.

Figure 2. Agreement among participants as to correctness of variants. Dashed outline indicates variants which the majority of participants judged as “incorrect”.

For both nasal stopping and denasalization, the participants showed a relatively high agreement that the standard variant is correct, while they showed much less agreement that the non-standard variant is incorrect.

For the czy-trzy merger, the reverse is the case. The participants showed a relatively high agreement that the non-standard [t͡ʂ] is incorrect (85% agreement), while they showed less agreement that the standard [t͡ʂʂ | tʂ] is correct (∼74% agreement).

For pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation, for which as already seen in both the standard and the non-standard variants are mostly seen as correct, there is somewhat higher agreement as to the correctness of the standard variant.

Table 1. Examples of two-word sequences with and without pre-sonorant voicing.

Table 2. Categorization of perception responses by variable by variant.

To verify the statistical significance of differences between the chances of non-standard and standard variants to be seen as “correct,” we used mixed-effects binomial logistic regression modeling. We fit a model of response (binary response variable, reference: “incorrect,” remaining level: “correct”) as a function of several predictors: variable (multi-level categorical predictor: “czy-trzy merger,” “nasal stopping,” “nasalization,” “pre-sonorant voicing,” “nasal assimilation,” reference: “czy-trzy merger”), standard_language_dominance (binary predictor variable encoding answers to the question “Should all Poles […] speak Polish in the same, standard way?”, reference: “no,” the other level: “yes”), mobility (binary predictor variable encoding answers to the question “How many times have you moved in the last 10 years?”, reference: “low,” the other level: “non-low”), and age (a continuous variable). Each of the four predictors interacted with a fifth predictor variant (binary predictor, reference: “standard,” the other level: “non-standard”). Additionally, the model contained by-word and by-participant random intercepts to quantify individual-level and item-level differences, as well as a by-participant random slope for trial, to account for potential learning effects or fatigue effects.

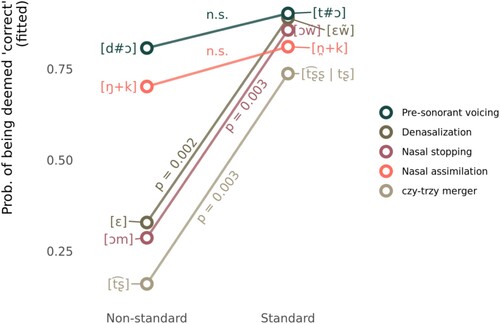

A likelihood ratio text () showed that the variable * variant interaction term was statistically significant. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were performed with the emmeans function from the eponymous package (Lenth Citation2021). They showed that the standard variant was significantly more likely to be rated as correct for denasalization (

= 2.82,

= 0.002), nasal stopping (

= 2.71,

= 0.003), and the czy-trzy merger (

= 2.7,

= 0.003). No statistically significant difference between the standard and the non-standard variant was detected for pre-sonorant voicing (

= 1) and nasal assimilation (

= 1). This effect is illustrated in .

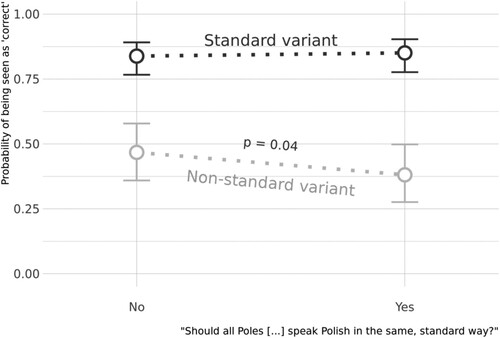

Additionally, as visualized in , listeners believing all Poles should speak Polish in the same standard way were more likely to judge the local variant as incorrect than those who did not express this view ( = -0.45,

= 0.04).

Figure 4. Partial effect of the interaction between variant and views on the dominance of the standard variety of Polish.

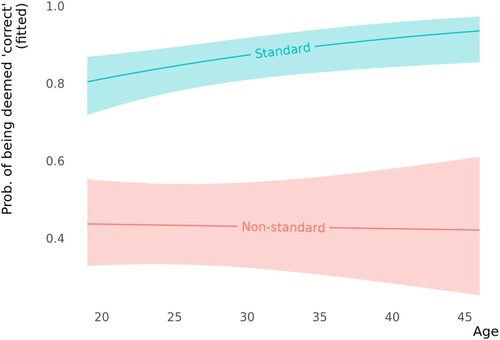

Finally, the likelihood to see the standard variant as correct increases with age, as attested by the significance of the positive estimate of the age predictor ( = 0.05,

= 0.01) (notice the top line going up from left to right in ). The influence of age on the judgments was not attested, as shown by the ‘neutralization’ of the former estimate by the estimate of the age:variant predictor (

= -0.05,

= 0.02) (notice the bottom line staying almost flat in ).

5.1.2 Processing Speed

Categorization results suggest a division grouping pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation as variables with relatively little salience on the one hand, and the remaining three variables, that is denasalization, nasal stopping, and the czy-trzy merger as variables with relatively higher salience on the other hand. Looking at descriptive statistics of processing speed, however, a different grouping seems to emerge (see ). Pre-sonorant voicing and the czy-trzy merger are responded to the fastest (721 ms and 722 ms, respectively), then come nasal stopping (738 ms) and denasalization (737 ms), while nasal assimilation elicited the slowest responses (758 ms). There is an asymmetry within the two variables that elicited the fastest mean responses: for pre-sonorant voicing, it is the non-standard variant the was responded to faster, while for the czy-trzy merger it was the standard variant.

Table 3. Mean processing speeds of the variables and variants.

To test the statistical significance of these differences, we fit a linear regression model with processing speed (1/rt) as the response variable, with the same architecture as the binomial logistic regression model described above. A likelihood ratio text () has not shown the variable * variant interaction to be statistically significant. In view of this, we have not conducted any post-hoc pairwise comparisons.

5.2 Production

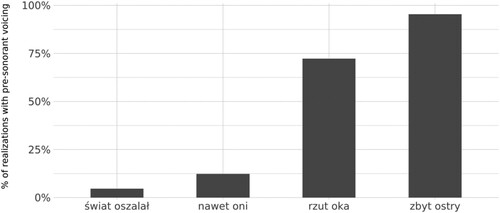

Looking at production data (see ), we can see that the participants produced predominantly standard variants for the czy-trzy merger (98%), nasal stopping (95%), denasalization (90%), and nasal assimilation (85%). The non-standard pre-sonorant voicing, on the other hand, was applied nearly as often (46%) as not (54%).

Table 4. Production rates of the variables and variants.

Pre-sonorant voicing, which showed the largest proportion of non-standard realizations, displays stark by-item variation (see ). świat oszalał ‘the world has gone mad’ and nawet oni ‘even them’ showed very little pre-sonorant voicing (5% and 12%, respectively), while ‘rzut oka’ a glance was realized predominantly (72%), and zbyt ostry ‘too spicy’ almost exclusively (95%) with pre-sonorant voicing. At any rate, these differences warrant further research: perhaps transitional probabilities or prosodic boundary strengths influence pre-sonorant voicing (cf. Wojtkowiak Ewelina & Schwartz Citation2018).

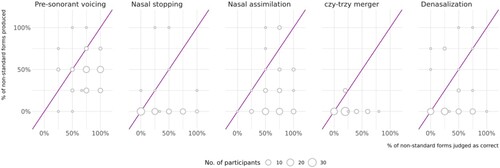

5.3 Perception vs. Production

Pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation are the two variables for which there were the smallest differences in correctness judgments of the standard vs. non-standard variants. Pre-sonorant voicing is the variable most often produced with its non-standard variant (46%). Nasal assimilation is the second most often produced with its non-standard variant, though with a much lower rate (15%). There is some correspondence, then, between participants’ productions and their judgments.

In , each circle is a group of participants, with the size of each circle corresponding to the number of participants it represents. Groups that align on the diagonal line are made up of participants whose judgments perfectly match their productions. For example, for pre-sonorant voicing, there is a circle right in the middle of the plot: these participants produced pre-sonorant voicing in 50% of their productions and judged 50% of the stimuli that contained pre-sonorant voicing as correct. Most participants are not like that, however. The circles that are in the bottom right-hand half of each plot group participants who judged the non-standard variant as correct more often than they produced it themselves. The majority of participants are in this group. Finally, there were participants who produced non-standard forms more often than they judged them as correct: they form the circles in the top left-hand half of each plot. Interestingly, there is a participant who produced nasal stopping at a rate of 100%, but they judged only one out of four stimuli with this variant as correct.

6. Discussion

6.1 The czy-trzy Merger and Nasal Stopping

Following Labov’s distinction into stereotypes, markers, and indicators (Labov Citation1972), we believe that nasal stopping and the czy-trzy merger serve as stereotypes in Greater Poland Polish. First of all, the participants demonstrated a high level of awareness of the non-standard variants of the two variables since [ɔm] and [t͡ʂ] were significantly more often judged as “incorrect.” The elicited careful speech samples allowed us to see which variants are stigmatized, and thus consciously avoided. As evidenced by production rates, participants avoided the use of the non-standard variants [ɔm] and [t͡ʂ]: nasal stopping was used only in 5%, and the czy-trzy merger in 2% of tokens. Further, the participants demonstrated a high degree of agreement (85%) when rating the variant [t͡ʂ] as incorrect, while the percentage of agreement was lower (74%) when rating the variant [tʂ] as correct. One possible explanation of the relatively low agreement that the standard variant is correct may be that the [tʂ] sequence often results from hypercorrection. Speakers who have the merger but are aware of the stigmatization of the affricate [t͡ʂ] have the tendency to avoid the affricate altogether. Words which contain the affricate [t͡ʂ], e.g. oczy ‘eyes,’ are then realized with a stop-fricative sequence here: [ɔtʂɨ]. Listeners noticing the discrepancy between such productions and the standard variants might develop a distrust of the plosive-fricative sequence as well. Taken together, the fact that the czy-trzy merger is consciously avoided in careful speech and that it shows hypercorrection lends support to our claim that the czy-trzy merger is a stereotype in Greater Poland Polish. In addition, looking at the relationship between perception and production, even though some speakers judged the non-standard variants as correct, few produced them in their formal style. Rating non-standard forms as correct may be linked to general beliefs about the dominance of the standard dialect. The respondents who do not believe that standard Polish should be used by everyone, regardless of place of origin, perceived non-standard variants as correct more often. Still, the majority of participants judged the two non-standard variants as incorrect, so overall [t͡ʂ] and [ɔm] are seen as carrying little prestige.

Our findings concerning the czy-trzy merger and nasal stopping agree with extant research. When it comes to the czy-trzy merger, the current study corroborates Kaźmierski et al.’s (2019) findings in that the czy-trzy merger was avoided in production. While in Kaźmierski et al.’s study (2019) it was present in 23% of tokens, in the current study it was produced only in 2% of tokens. This difference can be accounted for in terms of the type of production task – Kaźmierski et al. (Citation2019) used the Greater Poland Speech Corpus containing recordings of interviews (casual speech), while we used a word-list reading task, which elicits very controlled speech (cf. Trudgill 1974). Even though both studies show that the czy-trzy merger is not dominant in contemporary Greater Poland Polish, the current study additionally sheds some light on the cause of low production rates of the merger: speakers avoid it, in particular in formal speech, since they have internalized the view that the merger is incorrect. Similarly, in the case of nasal stopping, the results of the current study dovetail with previous research which demonstrated that the variant [ɔm] is retreating from Greater Poland Polish (e.g. Kaźmierski and Szlandrowicz Citation2020; Kaźmierski, Kul, and Zydorowicz Citation2019; Baranowska and Kaźmierski Citation2020). Again, this tendency may be accounted for in terms of social salience: since nasal stopping is subject to overt social comment and as such judged as incorrect, it is avoided in production in careful speech.

6.2 Pre-sonorant Voicing and Nasal Assimilation

As the standard variants of these two variables were not judged to be correct significantly more often than the local variants, both pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation can be classified as indicators. While these variables, pre-sonorant voicing in particular, may be very well-known to linguists as features of Greater Poland Polish, they seem not to attract the attention of speakers. In terms of production, pre-sonorant voicing was the most frequently produced variant (46% of tokens) out of all five non-standard variants in this study. Additionally, in the case of pre-sonorant voicing, there was the greatest overlap between production and perception scores. This could mean that participants neither heard nor produced the difference between the local and the standard variant in some phrases, which further lends support to our claim that pre-sonorant voicing is an indicator. Stark by-item variation in pre-sonorant voicing is a strong incentive for further research into factors influencing its realization. In the case of nasal assimilation, perception did not strongly affect production since nasal assimilation was observed in only 15% of the tokens. However, given that in Kaźmierski et al.’s (2019) study it was the most frequently produced non-standard variant of Poznań speech, and given that in the current study the participants did not judge it as incorrect, nasal assimilation can also be tentatively classified as an indicator.

6.3 Denasalization

Although denasalization, just like the czy-trzy merger and nasal stopping, was significantly often judged as incorrect, the difference between the standard variant [εw̃] and the non-standard [ε] in terms of salience and stigmatization is not that clear-cut. Baranowska and Kaźmierski (Citation2020) found that denasalization was subject to style-shifting: in a reading task it was significantly less frequent than in the picture description task, which elicited more casual speech. On the other hand, though, speakers with higher education showed more denasalization. It seems that denasalization, though still not a part of the standard dialect, does carry prestige (cf. Baranowska & Kaźmierski Citation2020, 156). We can further substantiate this claim with the results of the present study since there was a high agreement that [εw̃] is correct, but much less agreement that [ε] is incorrect. Moreover, the juxtaposition of perception and production reveals that even if some speakers produced [ε] word-finally, the majority did not perceive this variant as correct. Potentially, in our experiment, the participants’ judgements were at least to some extent influenced by the fact that in the production part of the experiment the stimuli were presented to the participants in written form: the nasalized pronunciation of word-final <ę> seems to be much more frequent when speakers read a text rather than when they speak. As already indicated, the status of denasalization is not well established: some publications (e.g. Karaś Citation1977; Dunaj Citation2006) see it as standard, while others point to it carrying less prestige than [εw̃] (e.g. Zajda Citation1977). The present study suggests that denasalization is still not fully a part of standard Polish (it was produced in only 10% of the tokens); however, it is not overtly stigmatized the way nasal stopping and the czy-trzy merger are. We can conclude then that denasalization could be considered to be a marker in Labov’s salience hierarchy. It is not a marker of Greater Poland Polish, though, given that it is widespread throughout Poland, and that different prevalence for different Polish accents has yet to be shown.

6.4 Loss of Lexical Contrasts vs. Salience

Arguably, the salience of the variables might be related to the number of lexical contrasts lost when one of the variants is usedFootnote5. We have the degree of this homophony by taking a list of spell-checked word forms appearing in SUBTLEX-PL (Mandera et al. Citation2015) at least three times, and replacing standard orthographic representation of one of the variants (<trz > for the czy-trzy merger, < -ą> for nasal stopping, and < -ę> for denasalization) with spellings of their non-standard counterparts (<cz>, < -om>, and < -e > respectively). By this estimate, nasal assimilation, nasal stopping, and the czy-trzy merger yield relatively few word-form homonyms (4, 32, and 45 respectively), while denasalization yields the vastly higher count of 2,815 homonyms (see ). The czy-trzy merger results in homophony on an accidental basis. For nasal stopping, there is homophony between third person plural verbs and related plural dative nouns. For denasalization, there ensues a systematic and widespread homophony between first and third person singular verb forms, as well as homophony between singular accusative and plural accusative/nominative noun forms. If the extent of homophony were a decisive factor in the salience of the variables, one would expect very different results for the czy-trzy merger and nasal stopping on the one hand, with a couple dozen resulting homophonic word forms for each of them, and for denasalization on the other hand, with nearly three thousand resulting homophonous word forms. In the perception experiment, however, these three variables pattern virtually alike (cf. ).

Table 5. Estimated number of homophonic forms that ensue when the non-standard variant of each variable is used.

Pre-sonorant voicing takes place across word-boundaries, so it cannot be directly compared with the other four variables in which single words are concerned. When the second word in a sequence begins with a sonorant, the voicing contrast is lost both with pre-sonorant voicing (all word-final obstruents surface as voiced, e.g. but ojca [.dɔ.] ‘father’s shoe’ = bud ojca [.dɔ.] ‘father’s shacks.gen’) and without pre-sonorant voicing (all word-final obstruents surface as voiceless, e.g. but ojca [.tɔ.] ‘father’s shoe’ = bud ojca [.tɔ.] ‘father’s shacks.gen’Footnote6). What can be compared, however, is the number of two-word sequences that become identical to single words if pre-sonorant voicing applies versus if it does not apply. For example, krat nie ‘bars no’ is not homophonous with any existing Polish word if pre-sonorant voicing does not apply: [kratŋε] *kratnie, but is homophonous with the word kradnie [kradŋε] ‘steals’ if pre-sonorant voicing does apply. Conversely, chomik i ‘hamster and’ is homophonous with an existing Polish word chomiki [xɔmici] ‘hamsters’ when pre-sonorant voicing does not apply, but is not homophonous with any existing Polish word if pre-sonorant voicing does apply [xɔmiɟi] *chomigi. To estimate how widespread such homophony is depending on whether pre-sonorant voicing applies or does not apply, we worked with a list of bigrams generated from SUBTLEX-PL and counted how many of the two-word orthographic sequences in which the first word ends in a voiceless obstruent and the second word starts with a sonorant are identical to existing single wordsFootnote7: the resulting number is 1,270 (see ). Then, simulating the application of pre-sonorant voicing, we replaced all word-final letter sequences that correspond to voiceless obstruents with their voiced counterparts, and counted how many of these orthographic sequences are identical to single words: the resulting number is much lower: 134. It seems, then, that pre-sonorant voicing, through signaling a word boundary, helps avoid ambiguity instead of introducing it. Perhaps it is one factor contributing to this variable’s low salience.

Table 6. Estimated number of two-word sequences identical orthographically to existing single words, with as opposed to without pre-sonorant voicing.

7. Conclusion

Our study scrutinized the salience of five variables in Greater Poland Polish: pre-sonorant voicing, nasal stopping, nasal assimilation, the czy-trzy merger, and denasalization. Through an analysis of how native speakers of Polish living in Greater Poland perceive, react to, and produce the variables of interest, we found evidence which suggests that, in line with Labov’s model of social salience (1972), nasal stopping and the czy-trzy merger may be classified as stereotypes, pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation as indicators, and denasalization as a marker.

The linguistic evidence adduced in this study provides a valuable insight into linguistic variation in Greater Poland Polish. While previous studies sought to determine most characteristic variables in this dialect area and investigate their production rates (e.g. Witaszek-Samborska Citation1985; Kaźmierski et al. Citation2019), our study juxtaposed the production rates of these variables with their perception through the lens of Labov’s model of social salience (Citation1972). This can allow us to make tentative predictions as to the direction of linguistic change in Greater Poland Polish. Since stereotypes, in this case nasal stopping and the czy-trzy merger, are overtly stigmatized, they are likely to decline in the future, while, on the other hand, indicators, i.e. pre-sonorant voicing and nasal assimilation, may well remain stable in Greater Poland Polish. While social factors are not the only ones influencing the trajectory of language change, with other factors, such as articulatory difficulty, perception, or contrast preservation likely playing a role as well, the social dimension is certainly one to be considered.

Denasalization necessitates further research. On the basis of previous research (e.g. Baranowska and Kaźmierski Citation2020), and the current study, we postulate an intermediate status of denasalization: speakers tend to avoid it even if they do not consider it incorrect. The standard form, [εw̃], on the other hand, is often seen as hypercorrect. Future research could therefore seek to probe deeper into this apparent case of linguistic insecurity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For example, our friend’s mother (both Greater Poland natives) would respond to Jak nie? [jag ŋε] ‘What do you mean, “no”?’ with Jagnię [jagŋε] to taka mała owca ‘A lamb is a little sheep,’ mocking our friend’s Greater Poland Polish form [.gŋ.] with pre-sonorant voicing, which contrasts with the Warsaw-oriented standard [.kŋ.].

2 As one of the Reviewers notes, for sequences with multiple word-final <ę>’s, such as widzę tę dziewczynę ‘I see this girl,’ the proponents of [εw̃] over [ε] advise to use [εw̃] only in the final instance of <ę> rather than in all of them. It is highly unlikely, as the Reviewer points out, that this is a natural phonological rule.

3 For a certain elementary school principal from Poznań, poczet sztandarowy ‘honor guard’ is [pɔtʂεt] instead of the expected [pɔt͡ʂεt], and school children at the said school end up pronouncing czytać ‘read’ as [tʂɨtat͡ɕ] instead of the historically and orthographically justified form [t͡ʂɨtat͡ɕ].

4 For example, dzieciom /d͡ʑεt͡ɕɔm/ ‘children’ occasionally becomes [d͡ʑεt͡ɕɔw̃].

5 We wish to thank one of the Reviewers for raising this important point.

6 Though compare Schwartz et al. (Citation2021), who found small differences in closure durations before underlyingly voiced and voiceless word-final obstruents in Polish.

7 First, we excluded bigrams that occur less than three times; bigrams for which either of the two words does not occur in the spell-checked list of single words, and bigrams in which the first word consists of a single letter (a rough method of excluding prepositions, which do undergo voicing throughout Polish). We extracted bigrams in which the first word ends in a sequence of letters corresponding to a voiceless obstruent, and in which the second word begins with a sonorant. Note that this method disregards lexical stress.

References

- Albin, Aaron. 2014. “PraatR: An Architecture for Controlling the Phonetics Software “Praat” with the R Programming Language.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 135 (4):2198.

- Andersen, Henning. 1986. “Sandhi and Prosody: Reconstruction and Typology”. In Sandhi Phenomena in the Languages of Europe, edited by Henning Andersen, 231–248. The Hague – Berlin: Mouton der Gruyter.

- Baranowska, Karolina, and Kamil Kaźmierski. 2020. “Polish Word-Final Nasal Vowels: Variation and, Potentially, Change.” Sociolinguistic Studies 4(1–2):135–162. DOI:10.1558/sols.37918.

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. “Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4.” Journal of Statistical Software 67 (1):1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

- Baumann, Andreas, and Kamil Kaźmierski. 2018. “Assessing the Effect of Ambiguity in Compositionality Signaling on the Processing of Diphones.” Language Sciences 67 (May):14–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2018.03.006.

- Bergstrom, Brittni Elizabeth. 2017. “Effect of Speaker Age and Dialect on Listener Perceptions of Personality.” Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6397.

- Bethin, Christina. 1984. “Voicing Assimilation in Polish.” International Journal of Slavic Linguistics and Poetics 29:17–32.

- Boersma, David, and Paul Weenink. 2018. “Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program]. Version 6.0.41, retrieved 15 Aug 2018 from http://www.praat.org/.”

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2008. “I’ll Be the Judge of That: Diversity in Social Perceptions of (ING).” Language in Society 37 (5):637–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404508080974.

- Cargile, Aaron Castelan, and Howard Giles. 1998. “Language Attitudes Toward Varieties of English: An American-Japanese Context.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 26 (3):338–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909889809365511.

- Clopper, Cynthia G., and David B. Pisoni. 2004. “Some Acoustic Cues for the Perceptual Categorization of American English Regional Dialects.” Journal of Phonetics 32 (1):111–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0095-4470(03)00009-3.

- Cyran, Eugeniusz. 2012. “Cracow Sandhi Voicing Is Neither Phonological nor Phonetic. It Is Bothphonological and Phonetic.” In Sound Structure and Sense. Studies in Memory of Edmund Gussmann, edited by Eugeniusz Cyran, Bogdan Szymanek, and Henryk Kardela, 153–83. Lublin: KUL.

- Dejna, Karol. 1973. Dialekty Polskie. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolinskich.

- Draxler, Christoph, and Klaus Jänsch. 2004. “SpeechRecorder. A Universal Platform Independent Multi-Channel Audio Recording Software.” In Proceedings of LREC, 559–62. Lisbon: European Language Resources Association.

- Dubisz, Stanisław, Halina Karaś, and Nijola Kolis. 1995. Dialekty i Gwary Polskie. Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna.

- Dunaj, Bogusław. 2006. “Zasady Poprawnej Wymowy Polskiej.” Język Polski 3: 161–72.

- Gussmann, Edmund. 2007. The Phonology of Polish. Oxford University Press.

- Hansen, Karolina. 2014. Stosunek Polaków Do Dialektów Regionalnych: Raport Na Podstawie Polskiego Sondażu Uprzedzeń 2013. Warsaw: Centrum Badań nad Uprzedzeniami.

- Jansen, Sandra. 2014. “Salience Effects in the North-West of England.” Linguistik Online 66 (4). https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.66.1574.

- Johnson, Jane. 1984. “Variations in Polish Nasal /ę/: A Contribution to the Development of Contrastive Sociolinguistic Methodology.” In Papers and Studies in Contrastive Linguistics, Vol. XVIII, edited by Jacek Fisiak, 31–41. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu.

- Karaś, Mieczysław. 1977. “Przedmowa.” In The Dictionary of Polish Pronunciation, VII–VIII. Warsaw: PWN.

- Kaźmierski, Kamil, Małgorzata Kul, and Paulina Zydorowicz. 2019. “Educated Poznań Speech 30 Years Later.” Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 136 (4):245–64. https://doi.org/10.4467/20834624SL.19.021.11314.

- Kaźmierski, Kamil, and Marta Szlandrowicz. 2020. “Word-Final /ɔ̃/ in Greater Poland Polish: A Cumulative Context Effect?” Research in Language 18 (4):381–94. https://doi.org/10.18778/1731-7533.18.4.02.

- Klemensiewicz, Zenon. 1965. Podstawowe wiadomości z gramatyki języka polskiego. Warszawa: PWN.

- Kliegl, Reinhold, Michael E. J. Masson, and Eike M. Richter. 2010. “A Linear Mixed Model Analysis of Masked Repetition Priming.” Visual Cognition 18 (5):655–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506280902986058.

- Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Lenth, Russell V. 2021. “Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means.” https://github.com/rvlenth/emmeans.

- Levon, Erez, and Sue Fox. 2014. “Social Salience and the Sociolinguistic Monitor.” Journal of English Linguistics 42 (3):185–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424214531487.

- Llamas, Carmen, Dominic Watt, and Andrew E. MacFarlane. 2016. “Estimating the Relative Sociolinguistic Salience of Segmental Variables in a Dialect Boundary Zone.” Frontiers in Psychology 7 (August). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01163.

- Lorenc, Anita, Daniel Król, and Katarzyna Klessa. 2018. “An Acoustic Camera Approach to Studying Nasality in Speech: The Case of Polish Nasalized Vowels.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 144 (6):3603 –3617.

- Mandera, Paweł, Emmanuel Keuleers, Zofia Wodniecka, and Marc Brysbaert. 2015. “SUBTLEX-PL: Subtitle-Based Word Frequency Estimates for Polish.” Behavior Research Methods 47 (2):471–83.

- Ostaszewska, Danuta, and Jolanta Tambor. 2000. Fonetyka i Fonologia Współczesnego Języka Polskiego. Warsaw: PWN.

- Paltridge, J., and H. Giles. 1984. “Attitudes Towards Speakers of Regional Accents of French: Effects of Regionality, Age and Sex of Listeners.” Linguistische Berichte 90: 71–85.

- Peirce, Jonathan, Jeremy R. Gray, Sol Simpson, Michael MacAskill, Richard Höchenberger, Hiroyuki Sogo, Erik Kastman, and Jonas Kristoffer Lindeløv. 2019. “PsychoPy2: Experiments in Behavior Made Easy.” Behavior Research Methods 51 (1):195–203. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y.

- Preston, Dennis R. 2010. “Variation in Language Regard.” In Empirische Evidenzen Und Theoretische Passungen Sprachlicher Variation, edited by Peter Gilles, Joachim Scharloth, and Evelyn Zeigler, 7–27. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Preston, Dennis R. 2011. “The Power of Language Regard — Discrimination, Classification, Comprehension, and Production.” Dialectologia Special Issue, II:9–33.

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Schwartz, Geoffrey, Kamil Kaźmierski and Ewelina Wojtkowiak. 2021. “Perspectives on Final Laryngeal Neutralization. New Evidence from Polish.” Phonology 38 (4):693–727. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952675721000373

- Strycharczuk, Patrycja. 2012. “Phonetics-Phonology Interactions in Pre-Sonorant Voicing.” PhD Thesis, University of Manchester. https://personalpages.manchester.ac.uk/staff/patrycja.strycharczuk/Research_files/PhD_2_sided.pdf.

- Trudgill, Peter. 1986. Dialects in Contact. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wickham, Hadley. 2016. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Second. Berlin: Springer.

- Wickham, Hadley, Romain Francois, Lionel Henry, and Kirill Müller. 2017. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr.

- Winter, Bodo. 2015. “The Other N: The Role of Repetitions and Items in the Design of Phonetic Experiments.” In Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, edited by The Scottish Consortium for ICPhS 2015, Paper number 0181.1–5. Glasgow, UK: University of Glasgow. https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/icphs-proceedings/ICPhS2015/Papers/ICPHS0181.pdf.

- Witaszek-Samborska, M. 1985. “Regionalizmy Fonetyczne w Mowie Inteligencji Poznańskiej.” Slavia Occidentalis 17:91–104.

- Wojtkowiak, Ewelina, and Geoffrey Schwartz. 2018. “Sandhi-Voicing in Dialectal Polish: Prosodic Implications.” Studies in Polish Linguistics 13 (2):123–43. https://doi.org/10.4467/23005920spl.18.006.8745.

- Zagórska-Brooks, Maria. 1964. “On Polish Affricates.” WORD 20 (2):207–210.

- Zajda, Aleksander. 1977. “Problemy Wymowy Polskiej w Ujęciu Słownika.” In The Dictionary of Polish Pronunciation, XXVII–XXXIX. Warsaw: PWN.

- Zaleska, Joanna, and Andrew Nevins. 2015. “Transformational Language Games and the Representation of Polish Nasal Vowels.” In NELS 45: Proceedings of the 45th Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society: Volume 3, 251–60. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Appendixes

Appendix 1: Questionnaire (original)

ANKIETA

Nr uczestnika … … … … … … … … …

2. Wiek … … … … … ..

3. Płeć:

□ KOBIETA

□ MĘŻCZYZNA

□ ŻADNA Z WYMIENIONYCH

4. Miejsce zamieszkania … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..

5. Wykształcenie … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..

6. Ile razy zmieniał Pan/i miejsce zamieszkania w ciągu ostatnich 10 lat? … … … … … … … … …

7. Czy chciałby się Pan/i wyprowadzić do innej miejscowości? TAK/ NIE

8. Jestem:

□ Praworęczny/a

□ Leworęczny/a

9. Czy mówi Pan/Pani z akcentem regionalnym? TAK/ NIE

10. Czy Polacy powinni pielęgnować swoje regionalne dialekty, gwary i lokalne sposoby mówienia? TAK/NIE

11. Czy wszyscy Polacy, niezależnie od pochodzenia i miejsca zamieszkania, powinni mówić po polsku w taki sam, standardowy sposób? TAK/NIE

12. Czy Polacy powinni mówić z akcentem regionalnym nie tylko w domu, ale również w miejscach publicznych, pracy, szkole? TAK/ NIE

Appendix 2: Questionnaire (translated)

QUESTIONNAIRE

1. Participant’s number … … … … … … … … …

2. Age … … … … … ..

3. Gender:

□ WOMAN

□ MAN

□ OTHER

4. Place of residence … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..

5. Education … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..

6. How many times have you changed your place of residence in the last 10 years? … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..

7. Would you like to change your place of residence? YES/NO

8. I am:

□ right-handed

□ left-handed

9. Do you speak with a regional accent? YES/NO

10. Should Poles cherish regional accents and dialects? YES/NO

11. Should all Poles use only standard Polish regardless of their place of residence? YES/NO

12. Should Poles be allowed to use their reginal accent not only at home, but also in public places (at work, school, etc.)? YES/NO