Abstract

We have heard and read much about the wartime bravery of Gurkha soldiers, the idea of the Gurkhas as a martial race and how British recruitment practices targeted them. But much less is known about the experiences of Gurkha prisoners of war in World War I. The Germans captured thousands of soldiers fighting in the British Indian Army, and among these were a large number of Gurkhas. This imprisonment of soldiers not only served German strategic goals, but also offered a good opportunity to collect source material for research. This paper will briefly shed light on the scholarly activities engaged in by German scholars in Halbmondlager (Half Moon Camp), with a focus on the self-referential writing of one of the Gurkha prisoners of war, Jas Bahadur Rai, who never returned from the camp, but who did bequeath to posterity a song which he sang for the Germans. We will discuss whether Jas Bahadur had freedom of agency while recording his song, and if this song indeed qualifies as life-writing.

Introduction

More than 940,000 South Asian soldiers and labourers were shipped across oceans between August 1914 and October 1918 to help sustain the British war effort.Footnote1 Of these, some 200,000 Gurkha soldiers are reported to have served in the British Indian Army,Footnote2 with one in ten never returning home from the battlefield.Footnote3 In addition, 16,544 soldiers from the Nepalese Army, including crack units from Maharaja Chandra Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana’s personal bodyguard, were loaned to British India for garrison duties on the North-West Frontier and in the United Provinces, which thus freed large numbers of troops from the regular Indian and British Armies for active service in the European theatre.Footnote4 Thus substantial numbers of men of Nepalese origin were deployed militarily outside their country during World War I.

The literature on South Asian soldiers during World War I, Gurkha soldiers in particular, is relatively small, and finding new sources always comes as a pleasant surprise. This essay will focus on Gurkha prisoners of war (POWs) in German camps during World War I. Gurkha POWs are often grouped together with Indian soldiers in prevailing studies, but aside from the fact that the Gurkhas were recruited in India and fought under the British Indian Army, they constituted a distinct military entity. We are therefore justified in attempting to explore the distinct experience of Gurkha POWs. Where, though, to start? One place would be with individual soldiers. One such was Jas Bahadur Rai, one of the Gurkha POWs who were confined in Halbmondlager (Half Moon Camp) in Wünsdorf, Germany. He has drawn attention to himself previously, having been focused on variously as an Indian Gurkha soldier by researchers studying World War I Indian POWs in Germany.Footnote5 They looked briefly at a song that Rai left behind, but leave unanswered many questions about both the song and the composer. Taking Das and Lange’s brief studies as a point of departure, I explore what we can learn about the person by conducting a closer analysis of his song—by ‘reading between the lines’ of his verses. Jas Bahadur was one of the Gurkha soldiers who never returned home. Given where his life took him and how it ended, this composition sung in his own voice is a valuable piece of primary source material.

Life history research, which has strong roots in sociology, is also widely used in other disciplines. Beyond the popular practice of using first-person narratives, personal interviews and other material containing information about some particular subject, this article will present Jas Bahadur’s song as a self-life witness in its own right—that is, it will treat it as encapsulating his lived experience as a Gurkha soldier and a POW. It will contend that his song is not only about himself but also about the social and political spaces that he and his comrades inhabited. The song reflects his personal experience of fighting a war in Europe, becoming a prisoner of war in Germany, and succumbing to nostalgia. But we may ask, although Jas Bahadur composed the song on his own, did he have freedom of agency in the production of the recordings? Or was he merely saying or singing what the German scholars asked or ordered him to? Does he truly represent himself in the two recordings of his that contain the song? What does the content of the song tell us, not only from a linguistic perspective, but also as historical, sociological or literary source material? Reading between the lines and conducting an analysis of his song in this almost forgotten archive will help us offer answers to these questions. Before turning to focus on Jas Bahadur and his song, it will first be useful to set out what we know about the POWs, Halbmondlager and the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission which recorded his song in the camp.

POWs in Halbmondlager

By late 1914, following the departure of the first units of soldiers from India, many Gurkhas from the north of the Indian subcontinent were already being mobilised and deployed in France and Belgium. In the first year of World War I, most of the Gurkha Rifles regiments arrived at Marseilles, were transported to the front, and fought in Neuve Chapelle in northern France and Ypres and Givenchy in Flanders in Belgium, among other battle sites. In World War I, nine million soldiers were captured on both sides. Two and a half million men fighting on the British side were captured on the battlefield and imprisoned in Germany as POWs,Footnote6 and among them were a large number of Gurkhas.Footnote7 South Asian soldiers who were captured by Germany on the Western Front were first taken to various POW camps in Germany; from the early months of 1915 onwards, Indian POWs were kept in Halbmondlager in Wünsdorf, south of Berlin. Having been categorised as Indian soldiers, most of the Gurkha POWs were also held in Halbmondlager. All of the Gurkha soldiers in the camp arrived there in the first year of the War.Footnote8 The imprisonment of soldiers fighting on the British side not only served Germany’s political aims, but the internees themselves were soon serving as primary informants for German scholars in various fields.

Halbmondlager (Half Moon Camp) in Wünsdorf and Weinberglager (Vineyard Camp) in nearby Zossen were sonderlager (special camps), set up for propaganda purposes and designed especially to imprison soldiers from the Entente powers’ colonies in Africa and Asia. In contrast to other POW camps, the prisoners of these two camps were to be treated in accordance with their religious practices; simultaneously, they were politically indoctrinated as part of a secret German military strategy to persuade them to turn against their colonial masters and join the German forces. Half Moon Camp, a so-called Inderlager (Indian camp), was built about forty kilometres from Berlin in order to keep South Asian prisoners separate from both French colonial soldiers from North Africa and Russian POWs. It was also an important training site for German troops before they were sent to the Western Front from Wünsdorf railway station. Though life was very rough in these camps and the mortality rate was high, prisoners usually enjoyed better conditions and better treatment than in standard POW camps.Footnote9 The inmates were from various ethnic (Gurkha, Rajput, Punjabi and Pashtun), social and religious (Muslim, Hindu, Sikh and Christian) backgrounds. As this was a propaganda camp, built in part for show, more cultural and physical activities were provided than in the other camps, along with facilities for religious practice. Thus, a mosque was built not far from the camp, and the street it was on is still called Moscheestrasse (Mosque Street), even though the mosque itself was demolished after the building allegedly fell into disrepair around 1930. However, all such activities were restricted by the limited camp space.

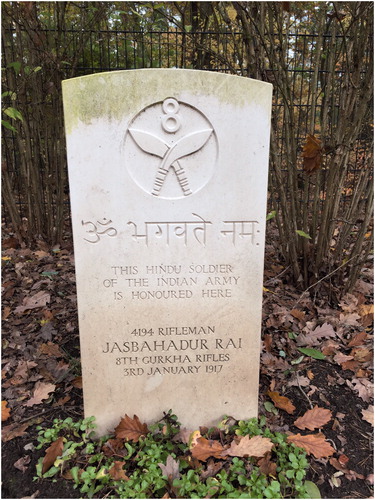

Halbmondlager included fifty barracks and associated outbuildings for 4,000 prisoners, housed separately according to religion and nationality. Each barracks had eighty inmates, a substantial space of some 103 square metres per prisoner (much more than the sixty square metres per prisoner at Weinberglager). Sanitary facilities in the camp were also generously apportioned,Footnote10 and the camp had a library with books in various languages. Propaganda lectures were a regular occurrence. However, the weather was not very kind to the South Asian POWs, and this was one cause of the comparatively high mortality rate among them. The cold, harsh winter climate often led to fatal cases of tuberculosis.Footnote11 A cemetery for deceased Indian camp inmates is located in the nearby village of Zehrensdorf, and contains 85 headstones of Gurkha soldiers from various Gurkha regiments,Footnote12 and four from the Burma Military Police. The POWs were kept in Halbmondlager until 1918. Towards the end of the War, before British forces could free the survivors, the POWs, including the Gurkhas from the Himalayas, were transferred to the Indian camp at Morile-Marculesti in southern Romania, where the climate and living conditions were healthier and more like what they were used to.Footnote13

The Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission and Gurkha recordings

At the suggestion of Wilhelm Doegen, a German high school teacher, the Royal Prussian Phonetic Commission was established in October 1915 to record the numerous languages, dialects and music of the soldiers and civilians imprisoned in Germany’s international POW camps. The commission, comprised of German researchers, aimed to compile a sound archive of all the languages in the world.Footnote14 Indeed, the camps filled with POWs were collectively a Mecca for the commission, providing as they did access to soldiers from around the globe.

The commission comprised thirty academics from different fields of research, including anthropology, linguistics, musicology and even Indology. The commission’s broad objective was to make systematic recordings of languages, music, phonetic sounds and stories representative of the prisoners’ countries of origin and store them in one comprehensive sound archive. The commission was divided into eight subunits: music (Carl Stumpf); anthropology (Felix von Luschan); English (Alois Brandl); Romance languages (Heinrich Morf); African languages (Carl Meinhof); Oriental languages (Eduard Sachau); comparative and Indo-Germanic languages (Wilhelm Schulze); and Indian and Mongolic languages (Heinrich Lüders).Footnote15 Equipped with phonographs, the members of the Phonographic Commission set out to record the voices of as many prisoners as possible in the POW camps by asking the prisoners to tell a story or sing a song in their mother tongue. Between 1915 and 1918, about 1,650 wax records in more than two hundred languages were produced by the commission under the leadership of Carl Stumpf and with the technical production assistance of Wilhelm Doegen. To complement the phonographic corpus, the members of the commission sought to produce a transcript of the recordings in the native script, a reproduction in phonetic notation, and a translation into German, together with a standardised personal-bogen (personal file) containing the personal data of the recorded prisoners and metadata about the time, location and type of recording. Today the records, together with all the existing files, are part of the Sound Archive of Humboldt University of Berlin. At the beginning of this century, all records and files were digitised and made accessible for scholarly research, but up until now, only very little such research has been carried out, and that focusing mostly on the production process. The more than one hundred recordings made by the POWs from the Himalayas have remained completely unexplored for almost a century.

Heinrich Lüders (1869–1943) was in charge of the recordings of Indian languages of South Asian prisoners, including those relating to the Gurkhas. For this purpose, he visited Halbmondlager, and also the Indian camp at Morile-Marculesti in southern Romania after the POWs were transferred there in 1918. Lüders was a German Orientalist and Indologist and had learnt South Asian languages including Sanskrit, Bengali and Pashto.Footnote16 During the period of recording in 1915–16, he was professor of Indian philology at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin and a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Lüders’ essay, ‘Die Gurkhas’,Footnote17 and his archive preserved in the Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften show that he was very much engaged with the Gurkhas and their languages.Footnote18 He writes in his essay that when he and Wilhelm Schulze visited the camp for research on the Gurkha (Nepali) language, the brave Gurkhas enthusiastically provided information. They were proud, Lüders writes, to know that German scholars attached such importance to their language. Some of them wrote down long stories drawn from memory on their own, while others, instead of reading out a long piece of text, chose to sing a song.Footnote19

Though the exact number of recordings produced by Lüders during his work for the commission is still unclear, we can verify that he and his associate Schulze were responsible for at least 109 recordings of POWs from the Himalayas. Since the categorisation of languages is not entirely reliable, we expect the number to be even higher, to include more recordings of Gurkhas and in other languages spoken in Nepal. For almost every record there exists at least one personal file, but phonetic transcripts are rare, and very few translations into German are available.

We turn now to Jas Bahadur Rai, one of the Gurkha POWs imprisoned in Halbmondlager who sang for the German scholars. Before delving into his song, we first review what we know about the man himself. The personal information sheet that was produced for him before his recording contains only scant personal information. This is the main primary evidence we have about him; the rest we must furnish by seeking links to wider recorded historical evidence.

Jas Bahadur Rai: A Gurkha rifleman

The personal file attached to the records of the sound archive both corroborates some other biographical information relating to Jas Bahadur Rai and also provides valuable additions. From the very limited information available on Jas Bahadur in the POW camp records, we learn that he belonged to a migrant Nepalese Rai family living in Sikkim. He was recruited by the 8th Gurkha Rifles (henceforth 8GR) in India. At the time the recording was made, in June 1916, Jas Bahadur was 23 years old, so he must have been born in 1892 or 1893. The record is less specific on the birthplace, stating only that it was Sukhim (today’s Sikkim). His personal file also mentions Darjeeling district or Darjeeling as the big city nearest to his home. It states that from the age of eighteen he lived in Shillong, today the capital of the Indian state of Meghalaya. Furthermore, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) files tell us that his father was Tas Bahadur Rai from Sikkim and his parental home is again given as Sikkim in the personal file. From these details we can conclude, then, that he was born in Sikkim and was recruited as a Gurkha soldier in Darjeeling since there was no recruitment station in Sikkim at the time, and recruits accordingly had to journey across the border.Footnote20 Before India’s Independence, each Gurkha regiment was established at a permanent home cantonment in the hills or foothills of the Himalayas, although battalions of the regiment would frequently be away from their home base during exercises or when on active service.Footnote21 The 8GR was headquartered in Shillong.Footnote22 We can surmise that Jas Bahadur was recruited to the 8GR from Darjeeling at the age of eighteen and was thereafter stationed at the headquarters in Shillong. That means that he was recruited around 1911 before being sent off to Europe in 1914. It is very unlikely that he went home to his family once he had left in search of a place among the Gurkha troops since a six-month holiday was granted only every three years.Footnote23 He never attended school and did not receive any formal education, but he could read and write in the Devanagari script. This suggests that he learned these skills in his regiment during training. He spoke Nepali (the ‘Gorkha’ mother tongue), Rai and Hindustani, registered his religion as Hindu and his profession as farmer. He did not play any musical instrument. Jas Bahadur Rai held the rank of rifleman in the 8th Gurkha Rifles and his service number was 4194.

Rais were a minority in Gurkha regiments until World War I, whereas Magars and Gurungs had been the most desirable ethnic groups prior to the war.Footnote24 Two decades before the war, Eden Vansittart stated that there were four major fighting elements in the Gurkha army, namely the Khas, Magar, Gurung and Thakur;Footnote25 there were ‘also a few Limbus and Rais to be found in most of our Gurkha Regiments’ who were residents of eastern and northeastern Nepal.Footnote26 Unsurprisingly, the recordings of the POWs in Halbmondlager tapped very few Rais: a mere three—Jas Bahadur Rai, Birkhe Rai and Bhawan Singh Rai—recorded their voices, and, of them, only Birkhe Rai used the Rai language. The Rai people are divided into many subgroups, each with a mother tongue of its own. It is not known which subgroups of the Rais the three POWs belonged to. Lüders writes in his notes that he worked with two different subgroups of Rais.Footnote27 They could not communicate with each other in their native languages, so they used Nepali to do so:

Finally we worked with the Rais, who also belong to a very different group.… We worked with two different Rai subgroups, the Khaling and Kulung. They were not able to speak with each other in their own tongue, but both languages undoubtedly have a common origin. There is only a remote link with Tibetan. Rai languages are not monosyllabic languages but have developed into multisyllabic ones, and, most importantly, into inflected languages.… Like Limbus, Rais belong to a Tibeto-Burmese group. At a very early period they penetrated into the country from the east; they are probably descendants of the Kiratas, who are described in Sanskrit texts that are more than 2,000 years old.Footnote28

There is no information as to where, when and under what circumstances Jas Bahadur Rai became a prisoner. Nor is it clear to which battalion of the 8GR he belonged. The dates of his journey to Europe and his imprisonment are not available. However, based on Lüders’ information that the POWs were brought to Half Moon Camp in the first year of the War, we may provisionally assume that he was part of the 2/8 GR. Available literature shows that the 2nd Battalion of the 8th Gurkhas, under the Meerut Division, had arrived in Marseilles by October 1914.Footnote29 It reached the Western Front on 29 October 1914 and promptly advanced to the front line near Festubert, south of the Ypres Salient.Footnote30 Jas Bahadur Rai was captured in battle in 1914, and was transported to Germany and imprisoned in the camp in Wünsdorf.

As with many other South Asian men, Jas Bahadur Rai’s journey to Europe did not come with a return ticket to family and friends. Not much information is available about his family or marital status, but his song hints at some sort of intimate relationship that, one may speculate, reflected his own circumstances. For all his memories of his homeland, his desire to return remained unfulfilled and he died on 3 January 1917 at the age of 24. He was buried in the Indian cemetery at Zehrensdorf. The cause of his death is not known, but we may conjecture, along with Lüders in similar cases that, as it was the peak of winter in Germany, he was among those who died of tuberculosis ().

Jas Bahadur Rai’s song

At 4 o’clock on 6 June 1916, Lüders and his associates recorded Jas Bahadur Rai’s song. A note in the personal file says that the song was selbstverfasst: composed (by the singer) himself. The recording required two cylinders, labelled with the call numbers PK 307/2 and 308.Footnote31 The first part of the song is on record PK 307/2 and lasts for 1:36 minutes (), while the second and longer part of the song, on PK 308, has a duration of 2:35 minutes (). Altogether, this provides a song of 4:11 minutes as material for analysis. The personal file also informs us that the recording took place in the Ehrenbaracke (Honour Barracks).

Table 1. The first part of the song by Jas Bahadur Rai: Stanzas 1–4.

Documents in the sound archive and Lüders’ archive in Berlin tell us that the songs were first written by the singers and then transcribed and translated. Once the manuscript was approved by Lüders’ committee, the recording could go ahead. Lüders’ archive also contains some manuscripts of the recordings written in Devanagari, transcribed into Roman script, and translated into German. Jas Bahadur Rai’s song, however, is not among those that had all these versions. Lüders mentions other songs in his handwritten manuscripts, but this song is not recorded there either. Sheets of paper containing Jas Bahadur’s song wholly in handwritten form are preserved in Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften’s (BBAW’s) archive in Berlin,Footnote32 and one can assume that Jas Bahadur himself penned it. The last three stanzas of the second part of the song were not recorded on PK 308,Footnote33 and the written version is not identical with the oral version. Since the spellings of words are not clear in the written version, the audio recording was comparatively easier to make sense of. In the case of the unrecorded stanzas, guesswork was sometimes needed to yield a reasonable reading. In the last stanza of the song Jas Bahadur wrote his name, so claiming authorship of the song—he was thus conscious of his right to be acknowledged for his own creation, while at the same time continuing a long South Asian tradition of authors being mentioned at the ends of manuscripts containing their works.

Jas Bahadur Rai’s song takes the form of a folk song, jhyāure or lok-gțt. There were two kinds of song or poetic compositions popular in Nepali between 1914 and 1918. The first was poetry in Sanskrit meters, which was often written by educated intellectuals; the second was folk songs or lok-gțts. Lok-gțts represented the voice of the public or common man and were transmitted through the oral tradition. This was a genre perfect for singing when people gathered in the fields, forests or villages, and people sang to give expression to their sadness or to entertain themselves. Most such songs describe social or personal concerns, with singers often making improvised changes to the text, and sometimes to the melody as well. The sentiments expressed are typically easy to identify with, and the melodies are simple to sing.

Describing the Nepali folk song, Krishna Prasad Parajuli writes that the first line introduces a phrase which is used as a filler or supporter.Footnote34 The second line carries the main content of the song. The third line, called the antarā, is again a filler or supporter, which completes the stanza and moves the song forward. This antarā can be repeated as the third line in every stanza throughout the song. Thus, a stanza will have three lines, with only the second line containing a significant portion of text. Following Parajuli’s description, I have divided Jas Bahadur’s song into separate numbered stanzas, categorised individual lines as either fillers or main content, and finally translated the whole as a basis for line-by-line and between-the-lines analyses.

Heinrich Lüders explains the nature of the songs sung in the camps in a similar way: ‘[T]he main message can be found only in the second line.… The first half-line is borrowed by the singer from somewhere else.… The second line is created [by the singer] on his own, and this is how a new song is created’.Footnote35 While working with the Gurkha POWs, Lüders must have confirmed this with the singers. Considering Jas Bahadur’s song in the light of Parajuli’s and Lüders’ remarks, we can say that he most likely adopted a well-known melody and elements of songs that he had heard and sung back home, then expressed his own feelings in the second line:

The Teesta river came flooding over. By what fault [of ours] did it carry [us] away?

Under England’s command we ended up in Germany.

Oh listen, listen, golden bird: under England’s command.

This is the first stanza (henceforth ‘S’) of Jas Bahadur’s song. This is a very good start to describing his life history as a POW and provides important information. The first line of the song refers to a flood on the Teesta river that carried him away. The Teesta originates in the Sikkim Himalaya and joins up with the Brahmaputra river which crosses almost all of Sikkim, some of Darjeeling district in India, and the northern part of Bangladesh. The Teesta is therefore an important feature in Sikkim and would naturally be mentioned often in regional songs. The introduction of the Teesta at the very beginning of the song indicates that the river had left a deep impression on Jas Bahadur, and by including it he reveals himself as a son of Sikkim; while travelling to Darjeeling for recruitment, he must have crossed it. Moreover, the river has symbolic meaning too, since even as the flooding of the Teesta carried people away, so did the war. And just as it is not clear what possible bhool (‘mistake’) might have caused the flood, so too is it unclear what human failings may have resulted in the calamity of World War I. Here the picture being painted is of guileless soldiers being swept into a conflict not of their own making, and on towards death. In fact, the 2/8 Gurkha Rifles sustained huge losses in the War.Footnote36 Just one ‘sweep’ of the German attack on the very first day could be compared to a sudden river flood that claimed many lives. As a POW in Germany singing this song in 1916, Jas Bahadur had likely been a witness to this onslaught but had somehow managed to survive it.

Jas Bahadur goes on to state that under England’s authority, the Gurkhas had been sent to Europe and ended up in Germany. His use of the first person plural pronoun ‘hamț’ (‘we’) denotes that he was speaking as a representative of all the Gurkhas fighting on Britain’s side: those still fighting, the POWs and those who had died. His phrase ‘Under England’s command we ended up in Germany’ demonstrates that the English had not ordered them to go to Germany; rather, the order was to participate in the war on the British side, and it was doing so that had led them to Germany.

Although Jas Bahadur was recording his song in the presence of fellow Gurkhas and German scholars, he directed his song not just to them. Unsure who would listen to it in the future, in the third line he requested a golden bird to take note of what he was saying. In South Asian literature, and in mythology in particular, birds are often assigned the role of messenger. Perhaps, therefore, Jas Bahadur intended the golden bird as a means of ensuring that his message reached back to his homeland.

The first part of the recording, PK 307/2, follows the three-line formula throughout, but in the second part, PK 308, the song changes form slightly. The first stanza has three lines, but after that, the third line is dropped. What does this tell us? Perhaps Jas Bahadur himself decided to omit it, wanting to make best use of the limited recording time to pack more substance into the text; perhaps the German scholars in charge of the recording decided to have him cut the third line as being unnecessarily repetitive: ‘Oh listen, listen…’. The first part of Jas Bahadur’s recording is fluent, and he evinces considerable self-confidence, but in the second part his singing is interrupted. Perhaps used to singing three-line stanzas, he felt uncomfortable not doing so in the second part. Whatever the reason, the second part of the song is longer and more expository (second line) ().

Table 2. The second part of the song by Jas Bahadur Rai: Stanzas 5–15.

Jas Bahadur did not borrow all the first lines in his song, as claimed by Lüders; he created some of them himself. Those which are about Germany, France and Belgium could not have been from his homeland because these places were not sufficiently well known to the public in northern South Asia to have found a place in local songs. This is one indication of Jas Bahadur’s authenticity: his own experiences and feelings were being expressed. The war broke out in Europe in the summer of 1914 after the German invasion of Belgium, thereby triggering Britain’s entry into the war on 4 August 1914. Jas Bahadur tells the Belgian monarch that neither he nor anyone else was enjoying fighting in the war: the conditions were not right for staying, nor were they right for dying. Here Jas Bahadur seems to be mindful of the Hindu belief according to which someone dying outside the Indian subcontinent will not attain salvation. That state can be reached if one dies in a holy place, but nowhere in Germany counted as such a place, nor anywhere in Europe or any other country across the ocean (S. 7, 8). To be sure, France and the broader European continent are featured in the second part of the song in glowing terms: the low-lying land with its shining blades of grass (S. 5), a beautiful garden of mustard flowers that Europe is compared to (S. 6), the beautiful plains of France and its large orange trees (S. 10). But such pictures only serve to draw Jas Bahadur’s thoughts back to his homeland and the love he has left behind. It is not clear from the available documents whether he was married, but he remembers someone beloved, and the beautiful mountains and the ricks of hay or straw north of Hindustan. He regrets that the knot of their love has come undone and asks her to retie her heart tightly to his, to retain her inner strength to survive their separation (S. 4).

Jas Bahadur is thus very outspoken in this recording. He sings confidently and in a commanding voice, revealing his feelings openly. He does not want to stay in Germany, or in any European country for that matter. He asks to be returned to India: from the headquarters in Shillong he could have travelled to his native Sikkim on his own. Yet he feels helpless, seeing no way out of imprisonment. He can neither fly away home, nor can he be happy in the camp—a painful situation that causes his heart to shed tears (S. 2). Because of his inner pain he has lost a lot of weight and become a mere shadow of his former self. He cries out in pain; he can see no use nor end to it, and there is no one to share his pain (S. 9). His mouth has become so small, he says, that there is no point in opening it. Not that he does not want to: he says he would gladly share his feelings with his German captors, but he cannot do so because of his poor command of the German language. As well, a sense of shame holds him back (S. 11). He asks if he presents an honest appearance. He is aware that Gurkhas are known as a decent lot, and the pride that that occasions is enough, in his imagination, to put some weight back on him, if only a few ounces (S. 10). Jas Bahadur has consigned himself to his fate. Neither he nor anyone else is sure who will win the war, and this state of uncertainty, like the beginning of the war itself, is cause only for tears (S. 5, 6). He is tired of being in Europe, and his heart, which the Germans cannot imprison, flies back to his homeland (S. 13, 14).

Jas Bahadur’s song was recorded in June 1916, apparently during a period of oppressive summer heat and food shortages. Food was conspicuously mentioned; he obviously missed mutton and rice, the preferred festival food of non-vegetarian Nepalese. The idea of Gurkhas eating swans is wholly abhorrent to him (S. 7, 8).

Towards the end of the second recording, Jas Bahadur seems to be in a hurry to get through to the end. As a consequence, he repeats himself often, and is confused at times about the lyrics and the melody. It is possible that he was used to singing, or had earlier practised the whole song in three-line stanzas and felt uncomfortable cutting out the third line. Or perhaps he was worried about how to make the best use of the occasion to get his message across via machine to an audience he saw as including a girl clothed in gold.

Conclusion

Having undertaken this analysis, we return once again to the central question: at whom was Jas Bahadur’s song aimed? Was he speaking to a particular person or persons? To the king of Belgium? To his beloved? To his captors? To the public at large? Or simply to himself? Had he been asked by the Germans to compose a song or had he one ready at hand? Clearly, he must have hoped that his song would be heard by others who would be moved to respond in one way or another to his mental and physical situation, which he expressed with great feeling. When he says that he does not understand what people are saying in Germany (S. 11), it seems most likely that his song was composed in captivity, and he certainly would have been aware that his captors would be listening closely. I am quite sure that such thoughts led him to make the bold request in his song to let him go back to India (S. 7, 13, 14), so making clear his unwillingness to stay any longer in Europe. Thus, he not only relates his personal emotions, but paints a vivid picture of the space he inhabits, which has a direct bearing on those emotions. The repeated lines in his song are not merely fillers; they serve to provide additional significant information. In the first part they speak about his homeland, whereas in the second part it is more about where he finds himself now. Europe’s natural beauty is not enough to deflect his attention from his abject circumstances.

Returning, then, to the questions raised at the outset: who did Jas Bahadur imagine that he was in the social terms of community, ethnicity, religion and culture? He clearly defines himself as a ‘Gurkha’ and sees himself as representing that group. Up to the end of the nineteenth century, the Rais had not been thought to be as good as the other martial castes. Characterising the Rais and Limbus together, Vansittart had written: ‘they are very brave men, but of headstrong and quarrelsome natures, and, taken all round, are not considered as good soldiers as the Magar or Gurnng’.Footnote37 However Jas Bahadur is a Gurkha soldier and he firmly thinks of himself as part of his Gurkha regiment. His characterisation of himself in the song as someone who is shy and sparing with his words is the opposite of Vansittart’s characterisation of Rais. It may be that his song describes the person he had become as a Gurkha POW in a German camp by the time of the recording.

Was Jas Bahadur perhaps aware that the recording presented a precious occasion for a self-life narration that might outlive him, and did he compose the song with this aim in mind? Can we say that his own life was the primary subject of the song? In a sense, Jas Bahadur was probably not consciously aware of self-life writing: he was surely not singing the song just about himself; rather, he sang what he knew and felt as being representative of what his fellow internees were thinking and feeling, and he was aware that the medium of the song provided a friendlier vehicle for such expressions. He articulates his feelings carefully and concisely—even diplomatically. He would have been aware that if he strongly criticised German authority, his song would not be passed by the censorship committee. He therefore took a rather neutral position between the British and the Germans. But he still managed to convey a starkly personal outlook, read both directly and between the lines. In the last stanza which states his name, he made clear how he viewed his situation—as comparable to the one Ram and Lakshman faced in exile as hunters in a dark forest (S. 15). Sadly, these last stanzas containing Jas Bahadur’s heartfelt emotions remained unrecorded.

The work of the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission was not designed to broadcast the output of the POWs to a wider German audience or to their homeland; rather the recordings were being made for their linguistic value alone. Yet some of the songs do have a more universal appeal, conveying as they do the ever-recurring predicament faced by those who, like the Gurkha POWs, have been robbed of their freedom far from home. The recordings produced by the commission are therefore very valuable, whether in historical, linguistic, literary or simple human terms.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a draft of a book in progress on Nepali literature, Gurkha soldiers and World War I. I am grateful to Stefan Lüder for accompanying me during my fieldwork in Germany and for his immense help in material collection. I am thankful to the South Asia anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments, as well as Britta Lange, Heike Liebau and Santanu Das for sharing their experiences in POW archival research. I am also grateful to Major S.K. Rai at Headquarters Brigade of Gurkhas, Camberley, UK, Chandra Laksamba at CNSUK, and the staff of BBAW & Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin for their interest in my work and kind support during my fieldwork in the UK in 2016.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Ravi Ahuja, ‘Lost Engagements? Traces of South Asian Soldiers in German Captivity, 1915−1918’, in Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), When the War Began We Heard of Several Kings: South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany (New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011), pp. 17−52.

2. Lionel Caplan, Warrior Gentlemen: Gurkhas in the Western Imagination (Providence, RI: Berghahn, 1995), p. 22.

3. David Bolt, Gurkhas (London: White Lion, 1975), p. 66.

4. Ibid.

5. Santanu Das, ‘Touching Semiliterate Lives: Indian Soldiers, the Great War, and Life-“Writing”’, in Maria Dibattista and Emily O. Wittman (eds), Modernism and Autobiography (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 127−42; Santanu Das, ‘Indian Sepoy Experience in Europe, 1914–18: Archive, Language, and Feeling’, in Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 25, no. 3 (2014), pp. 391–417; Santanu Das, ‘Reframing Life/War “Writing”: Objects, Letters and Songs of Indian Soldiers, 1914–1918’, in Textual Practice, Vol. 29, no. 7 (2015), pp. 1265–87; Britta Lange, ‘South Asian Soldiers and German Academics: Anthropological, Linguistic and Musicological Field Studies in Prison Camps’, in Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), When the War Began We Heard of Several Kings: South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany (New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011), pp. 147–84; and Britta Lange, ‘Poste Restante, and Messages in Bottles: Sound Recordings of Indian Prisoners in the First World War’, in Social Dynamics, Vol. 41, no. 1 (2015), pp. 84–100.

6. Franziska Roy, ‘South Asian Civilian Prisoners of War in First World War Germany’, in Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), When the War Began We Heard of Several Kings: South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany (New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011), pp. 53–95.

7. My research until now has uncovered 300-plus POWs in Halbmondlager.

8. Heinrich Lüders, ‘Die Gurkhas’, in Wilhelm Doegen (ed.), Unter fremden Völkern: Eine neue Völkerkunde (Berlin: Stollberg, Verl. für Politik u. Wirtschaft, 1925), p. 128.

9. Lange, ‘South Asian Soldiers and German Academics’, pp. 147–84.

10. Martin Gussone, ‘The “Halbmondlager” Mosque of Wünsdorf as an Instrument of Propaganda’, in Erik-Jan Zürcher (ed.), Jihad and Islam in World War I: Studies on the Ottoman Jihad on the Centenary of Snouck Hurgronje’s ‘Holy War Made in Germany’ (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2016), pp. 181–3.

11. Heinrich Lüders, ‘Die Gurkhas und Nepal’, Brandenburgrische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Archiv, Berlin, Nachlass Heinrich Lüders, Vol. 1, no. 14 (n.d., handwritten manuscript), p. 12 (hereafter referred to as Archive of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Heinrich Lüders Collection).

12. Gurkha Regiments 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8 and 10.

13. Gerhard Höpp, Muslime in der Mark: Als Kriegsgefangene und Internierte in Wünsdorf und Zossen (Berlin: Das Arab. Buch, 1997), pp. 44–5; and Leonhard Adam, ‘The Social Organization and Customary Law of the Nepalese Tribes’, in American Anthropologist, Vol. 38, no. 4 (1936), pp. 533–47.

14. Wilhelm Doegen, Unter fremden Völkern: Eine neue Völkerkunde (Berlin: Stollberg, Verl. für Politik u. Wirtschaft, 1925), p. 10.

15. Ibid.

16. Later, while working with POWs in the camp, Lüders also learnt the Gurung language.

17. Lüders, ‘Die Gurkhas’, pp. 126–39.

18. Archive of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Heinrich Lüders Collection.

19. Lüders, ‘Die Gurkhas’, p. 135.

20. The first authentic Gurkha recruitment office was established in Gorakhpur in 1886, while by around the turn of the century, a recruiting office had been opened in Darjeeling to service the eastern regions. See John Parker, The Gurkhas (London: Headline Book Publishing, 2005), pp. 78–9.

21. Caplan, Warrior Gentlemen, p. 22.

22. Ibid., p. 27.

23. Parker, The Gurkhas, p. 83.

24. Brian Houghton Hodgson, Essays on the Languages, Literature and Religion of Nepal and Tibet (New Delhi: Manjushri Publishing House, repr. 1972); and Caplan, Warrior Gentlemen.

25. Eden Vansittart, ‘Tribes, Clans, and Castes of Nepal’, in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. 63, no. 1 (1894), pp. 213–49.

26. Ibid., p. 215.

27. Lüders, ‘Die Gurkhas und Nepal’, p. 60.

28. ‘Zu einer ganz anderen Gruppe gehören auch die Rais, mit denen wir uns zuletzt beschäftigt haben…. Wir hatten es mit zwei Vertretern vom Rai Stamm zu tun, einem Kaling und einem Kulung. Sie waren nicht im Stande sich miteinander in ihrer Sprache zu verständigen, aber beide Sprachen haben unzweifelhaft einen gemeinsamen Ursprung. Mit dem Tibetischen besteht nur eine ganz entfernte Verwandtschaft. Die Rai Sprachen sind überhaupt keine einsilbigen Sprachen mehr, sie sind mehrsilbig geworden und was wichtiger ist, sie haben sich aus sich selbst heraus zu einer Art von flektierenden Sprachen entwickelt;… Die Rais gehören ebenso wie die Limbus zu einer tibeto-birmanischen Gruppe, die in sehr früher Zeit von Osten her in das Land eindrang; sie sind wahrscheinlich zu den Nachkommen der Kiratas zu zählen, von denen die Sanskrittexte schon vor mehr als 2000 Jahren erzählen’. Lüders, ‘Die Gurkhas und Nepal’, pp. 60–1, translation by author.

29. ‘The Meerut Division was disembarking by 11th October’. See General Sir James Willcocks, With the Indians in France (London: Constable & Co. Ltd, 1920), p. 20.

30. E.D. Smith, Valour: A History of the Gurkhas (Stroud, UK: Spellmount, 2007).

31. Lautarchiv (sound archive) at Humboldt-Universität, Berlin, Sound Files Archive nos. PK 307/2 and PK 308.

32. N.L. Lüders, Nr. 5 Bd. 2, pp. 45–8, Archiv der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (BBAW).

33. The unrecorded part is in italics in .

34. Krishna Prasad Parajuli, Nepālț lokgțtko ālok (Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 2064 V.S.), p. 77.

35. ‘…der eigentliche Sinn stecke nur in der zweiten Zeile…. Die erste Halbzeile hat der Sänger anderswoher entlehnt…. Die zweite Zeile dichtet er selbst dazu und schafft so ein neues Lied’. Lüders, ‘Die Gurkhas und Nepal’, p. 52, translation by author.

36. ‘I had known the 2nd battalion 8th Gurkha Rifles since 1886…. They were composed of a fine sturdy lot of men, and had they not had the misfortune to start their very first day in France exposed to a prolonged shelling, followed by a series of heavy attacks, they would not have been so heavily handicapped during the entire campaign as they were by the loss of practically all their own officers at one sweep—the most severe trial an Indian battalion can possibly undergo’. Willcocks, With the Indians in France, p. 79.

37. Vansittart, ‘Tribes, Clans, and Castes of Nepal’, p. 236.