Abstract

Partition produced newer anxieties for Delhi’s Muslims as they became subject to the everyday violence of both state and society, exacerbated by the rise of Hindu nationalism and the organised demarcation of Muslim-dominated areas as ‘exclusionary’ and ‘contested’ zones. While the city was fraught with violent conflicts and exclusionary politics, gender was also being redefined and renegotiated. This article will query the particular lived experience and embodied agency of Muslim women in order to study gender and space within the context of social, cultural, economic and political changes after Partition. It will explore the ways in which women exercised agency and claimed space and belonging in everyday negotiations and strategies for survival, thereby contributing to family income and small capitalism in the Old City. It will study their diverse experiences which were shaped by their social location and challenged by the political, religious, economic and social processes that impinged upon their lives. Rather than seeing them as passive subjects of history, it foregrounds Muslim women’s navigation of state, community and the household in independent India.

On 31 December 2019, Delhi experienced its coldest day in more than a century. But that did not deter the women of the Shaheen Bagh neighbourhood. Armed with thick blankets, warm cups of tea and songs of resistance, they had not left their spot under a tent on a public street since 15 December. And that is how they rang in the New Year—a few minutes after midnight, they stood up to sing the Indian national anthem.Footnote1

Leading newspapers across the world reported this as a story of the Muslim women of Shaheen Bagh ‘coming out’ of zenanas (inner quarters of the home) and purdah (veiling) to protest on Delhi’s streets. They were demanding the revocation of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which offered amnesty to non-Muslim migrants from neighbouring countries, but did little to reassure India’s Muslims, many of whom feared the law would discriminate against them. When used in tandem with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which requires people to prove their citizenship by producing legal documents going back generations, the Act is essentially intended to exclude Indian Muslims from citizenship.

It is worth examining who the women of Shaheen Bagh are. As a simple explanation, they are the women (or women from families) who were driven out of their homes during the horrors of the September 1947 Partition violence in Delhi.Footnote2 Nevertheless, despite what had happened, for various reasons, they had made the difficult decision not to move. Since then, the community has been subject to the politics of fear and suspicion on account of religion, but women have been made more invisible due to their gender. This article traces a history of their everyday negotiations and their survival against the backdrop of marginalisation and ghettoisation in post-colonial Delhi. It investigates how women claimed space by making certain life choices, thereby configuring their post-Partition identities. Their economic and social survival is at the heart of this story, as is also the women’s lived experience, economic livelihoods, social networks and connections that enabled this survival. The aim is to give visibility to Muslim women as multifaceted historical actors—as social workers, activists or ordinary women—who simultaneously occupy several social locations and negotiate through and around different constraints.

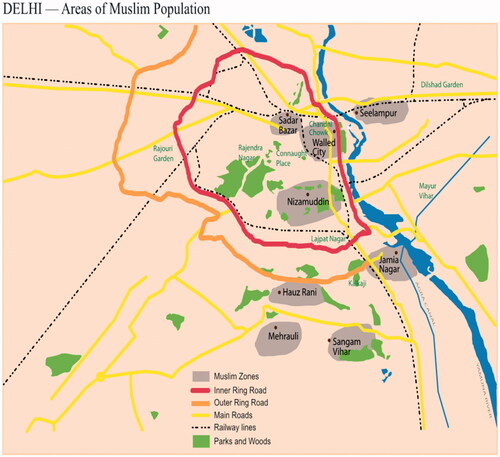

Delhi is an ideal location for such an investigation. The historic city of Shahjahanabad, commonly referred to as the walled city or ‘Old’ Delhi, had been the nerve centre of Indian Muslim political and cultural life for centuries. Partition resulted in the most dramatic events: the massacre of thousands and the departure of an estimated 330,000 Muslims, leaving the remaining Muslim community demographically and politically weak.Footnote3 An even greater influx into the city of Hindu refugees from Punjab, within a short span of time, caused a radical break with many existing structures of the past. Hindu refugees not only became the occupants of Muslim properties, but also took over the economy of Shahjahanabad. Scholars have talked about the ‘ghettoisation’ of the Muslim population when it was simultaneously pushed into ‘Muslim Zones’ by the state, but where it also chose to stay together for security and cultural affinity.Footnote4

Muslim women were not silent spectators to the city’s profound demographic, economic, social and cultural change. Partition impinged upon their lives in manifold ways. It led to the compression of space for Delhi’s Muslims as they became ‘refugees at home’ and came to huddle around their community.Footnote5 But it also led to the superimposition of gendered and patriarchal norms around Muslim women’s mobility due to a fear of ‘outsiders’ and the arrival of Hindu refugees in the city. While the state offered training and support to some Hindu women, it did not see Muslim women as in need of rehabilitation despite their experiences of violence and displacement. Elsewhere, I have discussed the commercialisation and feminisation of space with the arrival of Hindu refugees in Delhi,Footnote6 yet the assumption that Muslims were passive recipients of ghettoisation is misleading. This article shows that Muslim women too negotiated their post-Partition identities and subverted state and patriarchal assumptions about their roles and positions, contributing to the area’s economic livelihood and small capitalism there.Footnote7

The Muslim (woman’s) question

What does a focus on Muslim women’s subjectivity in Delhi reveal about the politics of the new nation of India in which citizenship and belonging came to be defined in religious terms, and in which people and communities spent the rest of their lives having to prove their loyalty? Although the ‘Muslim question’, as it is called in India, predated Independence and Partition, it acquired a special urgency during and after 1947. As Pandey asks, ‘Can a Muslim Be an Indian?’.Footnote8 Decolonisation was achieved along the idea of a ‘singular nation’ established around a particular core or ‘mainstream’—the Hindu majority in India. The ‘others’ or minorities were a means of constituting the national majorities or mainstreams. Muslims were seen as a minority that had wanted the founding of, or fought for, Pakistan, and they now had to not only choose where they belonged, but also demonstrate the sincerity of their choice. This, as Pandey argues, is one of the enduring legacies of Partition, and it has more than a little to do with the way the Indian nation has gone about the task of managing ‘difference’.

Muslim women are even more marginalised in this discourse due to their religious identity and gender. Colonial obsession with the veil and harem produced negative stereotypes of Muslim women as a ‘secluded species’,Footnote9 and Hindu nationalist discourse continues to typecast them as symbols of the backwardness of India’s Muslims. This discourse justified sexual violence against women during Partition and subsequent violence in various pogroms such as the recent communal attacks on Muslims in Delhi in a bid to humiliate the Muslim community.Footnote10

However, in the context of 1947, displacement generally refers to cross-border migration; scholarly work on people who did not move remains scarce. Some work, particularly by Vazira Zamindar and Joya Chatterji, focused on the internal displacement of Muslims who moved temporarily to refugee camps or other places within India during Partition rioting and who became refugees through the application of evacuee property laws to vacated houses. These works emphasise the role of the police and state complicity in this process of dispossession.Footnote11

But even these dominant historiographies have failed to recognise the experiences of Muslim women. Scholars of Partition have mainly focused on Hindu refugee women, while research on Muslim women remains largely neglected.Footnote12 Urvashi Butalia brought to the fore that women were the casualties of decolonisation and nation-building because they became the repositories of family, community and national honour.Footnote13 Mushirul Hasan reminded us that even after Partition, Muslims were far from being a homogenous community.Footnote14 But other than a handful of works which focus on religious practices, purdah, Muslim personal law and contemporary social issues, there is a dearth of scholarly engagement with Muslim women. Existing scholarship ascribes religion as the main, if not the only, aspect of Muslim women’s lives. One significant exception is Zoya Hasan and Ritu Menon’s anthology which calls for a ‘contextualised approach’ that treats Muslim women as located at the intersection of gender, family and community within the dynamic context of the Indian polity, society and economy.Footnote15 However, their focus is contemporary debates on education, employment and marriage following the Sachar Committee Report, which leaves the first two decades after Independence something of an empty slate.

While filling this gap in historiography, this article will ask about the particular lived experience and embodied agency of Muslim women in order to study gender and space within the context of social, cultural, economic and political change after Partition. In doing so, it will rely upon the analytical framework expounded by feminist scholars who make a persuasive argument that women’s agency is not only wielded in resistance to relations of domination, but also in the capacity to act according to the exigencies of a specific socio-cultural context.Footnote16 For this I use official records and contemporary reports; however, because of the nature of investigation that delves into aspects on which archives are famously silent, I also rely upon memoirs and oral histories that I collected during two rounds of fieldwork in 2016 and 2018 in Delhi. The respondents were chosen on the basis of gender, age, religious affiliation, community history, class, spatial location and nature of employment. Most respondents were interviewed in their own settings, over a period of time, to make conversation as comfortable as possible.Footnote17 This allowed women to speak for themselves, thus opening up possibilities for a complex consideration of their various social locations. However, in so doing, I am cautious to not reify the category ‘Muslim’ and so reduce their identities merely to religious affiliation, or assume that ‘Muslim women’ is an undifferentiated and stable category.

The article is divided into four sections. The first section will foreground Partition violence and the process of Muslim marginalisation in Delhi; the second will examine women’s social location and their diversity of experience with a particular focus on the politics of the refugee camps that brought about Muslim displacement; the final two sections will demonstrate women’s agency and space-making in Old Delhi through the choices women made for survival and livelihood in the years following Partition.

Partition and Muslim displacement in Delhi

As the rituals of Independence were being enacted in Delhi in August 1947, and Hindu refugees from Punjab were pouring into the city for safety and shelter, serious communal violence erupted in Old Delhi.Footnote18 A curfew was declared on 25 August.Footnote19 The situation was so bad that Maulana Azad stated: ‘no Muslim could go to sleep at night with the confidence he would wake up alive next morning’.Footnote20 Driven by fear and insecurity, Muslims were left with no option but to seek shelter in refugee camps, either waiting for the trouble to abate so that they could return home, or waiting to leave for a safe haven. By the evening of 9 September, there were some 25,000 refugees in the Purana Qila camp alone, and still more were arriving from all directions.Footnote21

The incidents of communal violence in Delhi in August–September 1947 were not entirely unexpected.Footnote22 A number of clashes, including stabbings and looting, had actually begun well before August as rumours about Partition started circulating. But Delhi faced orchestrated violence in August–September with the arrival of the refugees. The influx of Hindu and Sikh refugees from Punjab and Sindh created an unprecedented crisis. Delhi had a population of about 950,000 in 1947. Nearly 500,000 Hindu and Sikh refugees arrived in Delhi in the immediate aftermath of Partition; Muslim mosques, dargahs and graveyards were all occupied by refugees.Footnote23 Almost 330,000 Muslims left the Delhi region within a short time, and when the census was taken in 1951, the city had just 99,000 Muslim residents.Footnote24 According to Pandey, Delhi became a ‘refugee-istan’ with a staggering number of Hindu refugees seeking new homes, and an equally staggering number of local Muslim refugees imprisoned in their own homes or in refugee camps nearby.Footnote25 Old structures of Mughal glory such as Jama Masjid, Idgah and Palace-Fort became sites of Muslim refugee camps.Footnote26

The Government of India’s Delhi Emergency Committee advised Muslims not to vacate their houses and asked Muslim refugees to return to their homes from the refugee camps. But in most cases, Muslim refugees had no place to return to because their houses had been occupied by Hindu and Sikh refugees. The majority of Muslims in Delhi wanted to stay on and resume their livelihoods, but their confidence in the administration had been deeply shaken. A military spokesman estimated that on 18 September there were 121,000 Muslim refugees in various camps in Delhi living in filthy conditions, unprotected from sun or rain, and exposed to outbreaks of disease and epidemics. Their number eventually grew to 164,000.Footnote27 Gandhi, who visited the Muslim camps on 13 September, described their condition as one of ‘squalor’. At a prayer meeting, he said:

I went to the camps of Hindu as well as Muslim refugees. The camp for the Hindus is a different place. There is so much stench in the Muslim camps; I wonder why they are not cleaning the place.Footnote28

The basic principle on which land is given to refugees is that the land which has been evacuated by the Muslims in Delhi, who have migrated to Pakistan, should be given to Hindu and Sikh refugees, whose properties the Muslims who have migrated to Pakistan will eventually possess. Then on that premise, it is fair that we give preference to incoming migrants in the light of their need.Footnote29

Vazira Zamindar portrays the long-lasting outcomes of Partition which extended well beyond 1947. In the early 1950s, the Indian government introduced permit systems which set limits on who could return to India to prevent an influx of Muslims attempting to take back their original homes. She touches on the many ways in which citizenship was made ambiguous for those who wanted to return.Footnote30 In effect, many traditional quarters of Old Delhi, such as Mori Gate, Chandni Chowk and Kashmere Gate, lost the greater part of their occupants in a very short period. After a visit to Old Delhi in November 1947, Gandhi said regretfully:

It hurt me deeply to not see a single Muslim as I passed through Chandni Chowk yesterday. Chandni Chowk had been for centuries a predominantly Muslim business locality.Footnote31

The census of 1951 stated that about 190,000 refugees in Delhi were accommodated in houses left by Muslims.Footnote32 These changes not only alienated Muslim residents of the area, but also left a deep imprint on their traditional economy. In his memoir, Jalil Abbasi noted that some of the best traditions in art and craft were lost in the process of migration and refugee occupation of Old Delhi.Footnote33 Many Muslims who were left in the city belonged to the lower economic strata, such as dafali (drum) makers, dhobi (washermen), gadheri (bricklayers), ghoshi (milk men), qasai (butchers) and mirasi (folk singers).Footnote34 Anthropological studies of occupations such as the zardozi craft and teli (oil pressers) revealed their stagnation. According to the findings of the 2006 Sachar Report, the bulk of urban Muslims were either self-employed or employed in small informal businesses and enterprises.Footnote35 Many of them worked as artisans in weaving, carpentry, metal work or mechanics and in petty trade. These businesses remained outside, if not wholly excluded from, the new economy of India.Footnote36

The state dealt with the disputes over housing by settling Muslims in ‘zones’ which were considered an immediate solution to the law and order problem.Footnote37 ‘Muslim zones’ such as Jama Masjid, Sadar Bazaar, Bara Hindu Rao and Pul Bangash were deliberately created by police intervention, and Muslims who had fled their homes were encouraged to settle in these zones (). The Muslim-dominated neighbourhoods that emerged in this process of ‘regrouping’ (or ‘un-mixing’, as Chatterji has described it in the case of Bengal)Footnote38 were increasingly referred to as Muslim ghettos. This aggravated the marginalisation of the community because ghettos became sites of suspicion. This classification had other serious implications too—it denoted the estrangement of Muslim localities, and their residents, from the rest of the city. The subjective sense of closeness among the residents of these neighbourhoods, and their neglect by state authorities, translated into a lack of infrastructure, educational facilities and other amenities. This classification received semi-official recognition in the Sachar Report when the authors claimed that ‘fearing for their security, Muslims are increasingly resorting to living in ghettos across the country’.Footnote39

Gendered realities of Muslim refugee camps

Even when the city was surcharged with violence, many Muslims who had familial, business or property stakes in Delhi were eager to return to the city. Nehru himself estimated that about half of Old Delhi’s Muslim evacuees wished to return to their own homes and neighbourhoods and had no desire to migrate to Pakistan.Footnote40 The displaced population in the Muslim refugee camps needed urgent attention. Many nationalist women were commissioned by the state to look after the vulnerable and displaced population.Footnote41 Women’s involvement was justified as service to the nation, and while most of these were elite women, they were recruited for their experience of nationalist politics and the fact that they could spare time and energy for this voluntary task. Women social workers took their roles seriously, and a few even wrote about their experience of social work.

One such social worker, Begum Anis Kidwai, wrote a moving account of life in Delhi’s Muslim camps, particularly the conditions for women and children. Her memoir, Azadi Ki Chaon Mein, gives a heart-wrenching story of India’s Partition by describing the differential treatment given to Muslim camps and the condition of women and children there, who are otherwise missing in official narratives. Kidwai was an activist and politician; like many of her counterparts—Surayya Tayabji, Saeeda Khurshid and Qudsia Aizaz Rasul and others—she was deeply invested in nationalist politics and the nation-building project in the early years of India’s Independence. Her political career started with her role as secretary of the Women’s Congress Committee from 1921 to 1923. In 1947, Kidwai received a setback when her husband, Shafi Ahmed Kidwai, was murdered in a communal attack in Mussoorie while fighting against the forcible occupation of Muslim evacuee property. After his death, Kidwai devoted herself to social work, primarily serving in refugee camps in Delhi at Gandhi’s behest. She also played a pivotal role in the government’s project of recovery of abducted women. Kidwai recalled that neither at Purana Qila nor at Humayun’s Tomb were Delhi’s famed Muslim aristocracy—nobles, their begums and nawabzadas—to be found. She wrote: ‘they had trickled away in ones and twos to Pakistan in September itself. Any visit they might have made to the camp had been for one or two days at most’.Footnote42 The bulk of the camp population were ordinary people—metal workers, shopkeepers, artisans, cattle-grazers and lower-level salaried workers—awaiting their turn to leave for Pakistan or to return home safely. Kidwai, like Gandhi, gathered the impression that Muslim camps were being treated differently compared to the ones for Hindu and Sikh refugees. She summed up the government’s bias against Muslim refugees thus: ‘while the latter (Hindu and Sikh refugees) were being rehabilitated, the former (Muslims) were being driven out of their homes. Muslim refugees were convinced with the belief that the Indian government wanted to throw them out of India’.Footnote43

Kidwai did not hail Independence as a moment of triumph, instead seeing it as a betrayal of nationalist hopes and expectations due to violence and the treatment of Muslim refugees. Her memoir is enmeshed in an intimate history of emotion and personal experience as she saw her loss being experienced by countless other women. She was conscious of her class position and her role as a social worker commissioned by the state, yet for her, social work had the cathartic function of narrating trauma, dealing with pain and complicity, and negotiating her class position with the lived experience of ordinary women. She wrote:

September 1947 arrived, bringing in its wake scores of anxieties and tribulations. Delhi whose bylanes are redolent with a sense of history, a city that has been resettled as many times as it has been destroyed, a city, to whose history, a new and bloody chapter was being added by the violence that had consumed [it] since 5 September 1947. I was going to this city to drown the greatest sorrow of my life, in the hope that in the deluge that washed over us, I would sight some distant shore upon which I may anchor my future.Footnote44

Kidwai’s memoir is one of the most vivid accounts of the patriarchal nature of the programme of recovery of abducted women and the state’s complicity in violence against Muslims. It is also revealing of the myriad examples of women’s agency from their multiple social locations, even when it was denied to them. In one instance, one of the camp inmates, a woman called Kajalshah Begum, whom Kidwai describes as ‘sitting amidst a veritable mound of trunks and chests, screened off by a makeshift tent of sheets, and wearing silken clothes and exquisite jewellery’, said angrily, ‘what heroes have these Hindus become after attacking women and children? Let them try it once more and I will thrash them! Give us knives and watch a different outcome!’Footnote45 On other occasions, Kidwai described the conditions in the Purana Qila camp, largely full of the ill, aged women and children who had fled Paharganj, Karol Bagh, Multani Dhanda, Shidipura, Sabzi Mandi and nearby areas:

In October, the number of Muslim refugees in Purana Qila numbered about 60,000, barring a few who had found time to carry their belongings, most refugees had left their homes with only [the] clothes [they had] on…they had almost spent a month and a half in soiled clothes…. Every day a child, who was now an unwanted guest, arrived in the camp unbidden. The numbers ranged from fifteen in the day to ten at night. Mothers cried, fathers cursed their ancestors and midwives snapped in irritation to end the incessant stream of births. There was no one to look after these infants, or bathe them. As the midwife on night duty, cursing loudly, savagely severed the umbilical cord, and dunked the child in water, mothers had to look [on] helplessly, hearts gripped by panic. Weak and helpless, these mothers could not get even a moment of rest. One day I asked one of the midwives, ‘Will you return to your jobs once the camp is disbanded?’ They replied ‘Of course not! We were better off without this freedom. All we want is our salaries from Municipality. Once we get our money, we will leave for Pakistan’. Another refugee complained, ‘look at the way these Hindus look at us? Why do they come to the camp to laugh at us, to rub salt on our wounds?’Footnote46

To Kidwai, social work represented service to the nation, but she was far too aware of the complexities and limitations of the nation-building project in India; she saw the violence of Partition as a betrayal of all those who had tirelessly worked for India’s Independence. Yet Kidwai’s account went beyond just narrating violence; it carried everyday observations about the gendered lived realities of the camps, and insights into what displacement meant to those who were made refugees in their own city.

Gender and ‘immobility’ in Old Delhi

How did ordinary Muslim women who did not move away negotiate their identities after the upheavals of Partition? Unlike women social workers, they did not leave behind memoirs; their histories mattered even less to the nation, as most of them were subsumed into narratives of victimisation. Both colonial and nationalist rhetoric restricted them to the zenana—depicted as sites of sedition and confinement. Such spaces were eroticised and sexualised as places of immorality, of deviant sexual behaviour and the subordination of women.Footnote47 Indian nationalists used this imagery of the ‘backward’ and ‘victimised’ Muslim woman as a foil against which to contrast the category of the ‘ideal Indian woman’ as essentially ‘upper-caste, middle-class and Hindu’. This not only rendered Muslim women invisible, but also provided an explanation for their lack of public involvement in nationalism.Footnote48

Yet, in Delhi, which was a Mughal imperial city of tradition and custom (unlike Calcutta, known now as Kolkata, with its reforming middle class), Muslim women were active in political and social life, even though their numbers were lower than in Calcutta. Stephen Legg demonstrates that during the 1930s and 1940s, Old Delhi witnessed an upsurge in the activity and profile of its middle-class female population. Women became involved in processions, pickets and preaching in the street.Footnote49 His investigation has illustrated a number of ways in which women helped to ‘politicise the home’ and assert their agency in a space often read as one of silence and subjection. Women adopted traditional nurturing roles as well as transforming previous duties into new techniques of protest such as spinning, cooking, sewing and singing, thereby constructing political home spaces.

Research has also highlighted that zenana life was more prevalent among the upper classes. Most women of the middle and lower strata neither lived in houses large enough to support the concept of an inner quarter for women, nor did they have the resources to maintain segregation. Women in urban areas spent a great deal of time on their rooftops, conversing between one house and another. Gail Minault’s research reveals that women talked in the female-only Begamati zuban (women’s Urdu), and that the language of the zenana was earthy, graphic and colourful.Footnote50 Women visited one another frequently within their neighbourhood or close circle of relatives, and shared food on festive occasions with a whole network of families bound together by ties of blood or social and economic obligations.Footnote51 Women had multiple roles within the extended family and community, and well beyond their household duties. The segregation of the male and female spheres was less marked for working women—the washerwomen, milkmaids, female workers in karkhanas (factories) and sex workers who were lower than the tawaifs (courtesans) in rank and accomplishments, and who lived in the market area and catered to lower-class clients, including labourers.Footnote52 These women moved between the zenana and the streets, and were quite often visible in the public space of the mohalla and the bazaar.Footnote53

Partition produced newer anxieties for Delhi’s Muslims. Many families found compelling reasons to not move. People stayed behind due to familial and business obligations, but lower-class Muslims did not have enough pre-existing networks and ‘mobility capital’ to undertake the risk of migration. Joya Chatterji outlines physical frailty and obligations of care as crucial factors in shaping immobility in Bengal. Relations of gender and generation, as she argues, produced obligations to people and places that tied people down despite fear and poverty. Many Muslims stayed on due to complex ties or countervailing obligations. The make-up of a migrant’s particular bundle of ‘mobility capital’ influenced the trajectory of their movement.Footnote54

Whatever the reasons in Delhi, the decision to stay behind had gendered implications. The demographic and cultural upheaval of Partition and sexual violence against women led to women’s vulnerability and heightened anxiety around their mobility. For instance, Sakina’s family discontinued her secondary education and insisted on early marriage, although her two brothers continued to attend school. Sakina was not allowed to see her friends without a male chaperon as communal tensions continued in her neighbourhood.Footnote55 Rashida’s family, who were amongst the few ‘left over’ Muslim households in Gali Wazir Beg in Turkman Gate, grew increasingly anxious about her safety. She recalled:

Punjabi refugees occupied houses and businesses in the city. Hindu women bathed at community taps and thronged in gurudwaras for food and shelter, their men ran shops and businesses wherever they could find space. Strange men loafed around in our streets and police did nothing to evict them. How could we trust outsiders? My parents were worried about my safety, the horrors of Partition were too fresh in their minds. We feared for our well-being in those galis (streets) and kuchas (lanes) where we had lived for several generations. Our city became estranged and we never felt secure again.Footnote56

Women were made vulnerable by the sexual violence of Partition, but some women also exemplified courage and resilience in the face of adversity. For instance, Bismillah Begum, the young bride of the owner of Kallan Sweets Shop in Jama Masjid, saw no reason to leave Jama Masjid, the area where she had grown up and where her family had lived and worked for many generations. Bismillah relied upon her familial and social networks for her everyday life; she knew no other place that could give her the comfort and security of home. Bismillah lived in her family house, which was in the vicinity of the great mosque. The house was given to her in inheritance by her father, who ran a business in spare motor parts in Jama Masjid.

Bismillah’s family had been nationalists and supporters of Gandhi; her father accompanied Gandhi on his visit to Old Delhi in September 1947 because the family believed Gandhi’s arrival could end the communal violence. However, Bismillah’s husband, Kallan, was keen to move to Karachi, where a lot of their family were relocating. The violence of Partition had left Muslims weak and on the city’s social, political and cultural margins—many were left with no choice but to leave the city. But Bismillah threatened to go on a ‘fast until death’, as she cried in anguish: ‘yeh kaun hote hain mujhe bedakhal karne wale (who are they to displace me )?’Footnote57 Kallan finally conceded when he was given the choice of staying on or leaving without her even though many family members had left to save their lives and businesses. Bismillah was among those Muslims in India who chose to stay behind; she and Kallan continued to live in Jama Masjid even when the family witnessed considerable hardship and marginalisation as a result of incoming Hindu Punjabi refugees who occupied many of Old Delhi’s properties and businesses. When asked about her decision to stay on in India, she replied: ‘there was no way I could have left my home in Delhi; this is where I belong, and this is where I will die’.

Bismillah offered to do social work and activism; she was not educated but she campaigned against the government’s decision to close down Urdu-medium schools in the city. She established cultural and social ties amongst communities who had stayed behind, including organising monthly meetings at her house. She also helped revive the family’s sweets shop, their chief source of income which survived the test of time. It is today run by her grandsons who take pride in calling it a ‘generational venture’—Old Delhi’s ‘original’ sweets shop. Bismillah might not have transformed her structural conditions, but she was agential in shaping her life and claiming her own space, and she contributed to small capitalism and community life in Old Delhi. Yet her decision to stay behind was fraught with difficulties. Bismillah’s grand-daughter, Raheela, divulged that survival in Delhi was difficult for the family; many of her uncles were denied government jobs, and Raheela and her cousins faced discrimination at the university. The family remains close-knit, and most relatives live within five miles, but, according to Raheela, this was a conscious choice made by the family to stay close and together due to fear and insecurity.Footnote58

For Sadia Bano, a resident of Ballimaran, her sense of security was located in her space where she felt safe in the city. Sadia defined safety as a ‘Muslim environment’ where she could practise her faith and follow cultural norms. Asked about her decision to stay on in Delhi, she said:

We couldn’t have taken the risk to leave because we didn’t know anyone. My father was a sunar (goldsmith); we had our generational house in Delhi, a roof above us, and while we didn’t have a lot of money, we had our family and familiar relations around. Partition brought upon us an uncertain future but how could we have just left our house? That was our only proof of belonging to our homeland and link to the city. Those neighbours who left, could never really return home.Footnote59

Gender, space and small capitalism

There was considerable change in the economic profile of Delhi as many traditional crafts and industries declined in the absence of old patrons and the emigration of skilled workers. Those employed in traditional artisanal industries such as embroidery, weaving, metal work, mechanics or petty trade looked for new ways to survive. Thomas Blom Hansen’s work on Muslim areas in Aurangabad affirms that the majority of Muslims relied upon informal credit systems and informal jobs leading to ‘economic introversion’ amongst them.Footnote60 In Delhi, issues of survival and livelihood led Muslims to irregular and informal jobs. They used their old skills to adapt to change. Women combined household duties with earning responsibilities, and often relied upon familial and communitarian networks to eke out a living. In the process, they made the choice to engage, or disengage, with the state. This section investigates women’s strategies of survival that constitute the formation of Muslim subjectivities of the urban poor, who are almost wholly excluded from the constructs of the nation-state and denied the possibility of subjecthood within this broader, normative concept. Hence, this section reveals subject formation and the location of agency from the spaces of marginality.

Old Delhi had traditionally been a hub of craft production, and most urban artisans were either employed workers or independent pieceworkers operating out of small workshops.Footnote61 There were lohars (ironsmiths), qatibs (calligraphers), naqshanabis (artists), zildsaaz (bookbinders), kumhars (potters), embroiderers of zari, zardozi, kamdani, salma sitara, and so on. The majority of small artisans were Muslims belonging to the lower classes, although there were significant chains of business owners, middlemen and agents who were also Muslims. It was not uncommon for women to work as artisans and many provided labour in family workshops.Footnote62 There were streets and localities dedicated to particular crafts, hence Kucha Rahimullah Khan was where there were artisanal workshops engaged in chitai (engraving); Chandani Mahal boasted mirasi (musicians); Suiwalan was the traditional home of blue potters and bookbinders; and Kallu Hawas ki Haveli was where traditional embroiderers, zardozi workers and makers of tarazu (scales) worked. But there were also homes that had sections dedicated to family workshops, and very often there was specialisation of work within the household.

But with the flight of labour after Partition, these household workshops and chains were disrupted. Old markets disappeared, leading to only sporadic opportunities for work. In this situation, along with having to adjust their craft, the survivors had the additional burden of finding markets. The state was unable to recognise the needs of urban artisans, which also provides an explanation for the fragmentary nature of their work. Nagma Bi, a skilled zardozi worker from Matia Mahal, who had been trained in zardozi embroidery at her family workshop in colonial Delhi, found work as an independent pieceworker selling embroidered fabric to local traders in post-Partition Chandni Chowk. She recalled:

My father had a passion for embroidery; this is what he had inherited from his father. He used to sell his embroidered fabric to traders and owners of expensive shops in the market. I remember, some of the best shops in the city—Nadia fashions and Jafri emporium—used pieces from our workshop. Within home, we were all engaged in embroidery. We specialised in several styles, creating dazzling effects such as the stained-glass look, long cross-stitch, textured panels and much more. My mother knew chikankari (another form of intricate embroidery). But zardozi requires a special metal wire, and sometimes for very exclusive orders, we used pure silver wire coated with gold. It is not for everyone to do, as it requires sheer magic of fingers. My mother had made my own sharara (wedding dress) with zardozi. She often remarked, my daughter won’t always sew, but also enjoy embroidery on herself.Footnote63

During Partition, Nagma’s family decided to stay on because of generational ties with the place and the responsibility of caring for her disabled grandmother who could not move with them. Many of their customers moved to Pakistan, and the business never recovered. Nagma was engaged to be married by then, but the alliance could not be fulfilled because the boy moved to Karachi with his family. Thus Partition impinged on her family because it cut familial channels and networks they had relied upon to maintain social and economic life. After a few years, her father’s health deteriorated and Nagma married Rasik Miyan who ran a construction business in the same area. In her new home, about two miles from her natal home, Nagma continued her skill and passion for zardozi, although her husband did not want her to embroider for money despite the low returns from his own business. Nagma continued to sew for friends and family; after some time, she started taking ‘orders’ at home with the help of her neighbour, who ‘fetched’ work from the bazaar. Nagma’s income from her embroidery became a significant part of the family income and her networks in the locality helped her establish her business. She would finish her household chores and sew in the rest of her time and this continued for many years.

Nagma’s small business, which arose in response to her predicament post-Partition, not only sustained her family but gave her a sense of connection with the past. Like Nagma, many women made productive contributions to society and the economy, albeit in changed conditions. Amina worked as a cook and domestic help at Muslim weddings. Besides earning an income, community service was also important to her for the sense of belonging it gave her. A significant part of Amina’s family had migrated to Pakistan and her regular participation in community life was a way of maintaining social networks in an otherwise estranged city.Footnote64 Ferozah started a silai (sewing) centre at home to train young Muslim women in stitching babies’ frocks. She later joined the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), which brought her into contact with credit and marketing networks that transformed her home-based work into a local enterprise.Footnote65 She connected many local women with SEWA networks so they could earn a livelihood.

Women navigated the uncertainty of Independence and Partition in numerous ways. They did not necessarily acquire new skills and they often relied upon community networks and family connections. Their household vocations mostly operated at the margins of the mainstream economy, but nevertheless helped maintain family, household and community relations and gave them a sense of localised cultural identity. However, most women lived a precarious, fractured and marginalised existence, and their work was often subsumed into household responsibilities.

Nevertheless, women participated in a range of activities and multiple factors accounted for these. They engaged in child-rearing, food preparation, jewellery-making, hairdressing, domestic work, street hawking, social work and sewing. Munar stamped labels on jute bags for the wholesale grain market; Bushra taught in a local madrasa; and Samina continued to work as a midwife.Footnote66 These activities reveal women’s myriad ways of navigating marginalisation and claiming space and belonging in a changed milieu. When we think of women like Bismillah choosing to stay on and claiming her space in Jama Masjid, and Nagma’s reluctance to move to Karachi and navigating household and community to earn her family an income, we see them exercising their agency not just in exceptional circumstances, but also in everyday actions and negotiations.

Conclusion

Partition historiography on gendered experience centres around the experiences of the Hindu refugee woman as an exemplifier of refugee will and agency. However, there is hardly any scholarly engagement with the Muslim woman, even though Muslim marginalisation in independent India is well acknowledged by historians. One reason for this, as this article suggests, is to do with the larger discourse—colonialist, nationalist and post-colonialist—around Muslim women as the hapless victims of religious fundamentalism confined to purdah and zenana, which has also permeated historical writing and which denies agency to Muslim women as historical actors. Another significant factor relates to the lack of historical sources—official and institutional—in line with the larger agenda of the state to downplay Muslims as citizens and nationals of India. This has been made evident and obvious in repeated pogroms and Hindu nationalist violence against the Muslim community in recent times.

This article has relied upon alternative sources—oral testimonies and memoirs—to explore Muslim women’s subjectivities in Old Delhi. It has revealed that any simplistic characterisation of Muslim women as ‘victims’ and ‘oppressed’ are misrepresentations of their multifaceted engagement with and navigation of independent India. By focusing on the early decades of Independence, the article has demonstrated that Muslim women were not merely silent spectators to the changing dynamics in Delhi after Partition. While the city was riven by violent conflict and exclusionary politics, gender was also being redefined and renegotiated in relation to everyday spatiality. Women exercised agency and claimed space in their everyday negotiations and strategies for survival in order to meet their personal and familial goals.

Partition brought significant strains to Delhi’s urban world. With the arrival of Punjabi refugees, thousands of properties changed ownership in the first few years after Partition. The scale and extent of business and commercial activities multiplied as Old Delhi emerged as an important centre of Punjabi retail trade. This article has located Muslim women in this rapidly changing milieu. At one level, the arrival of Punjabi refugees and the rising communal and nationalist politics of independent India led to increased vulnerabilities for Muslim women, and heightened restrictions on their mobility and social life. Partition compressed the social spaces available to Muslim women and confined them within the walls of the Old City. But at another level, Partition also provided new social and economic exigencies for them to draw upon community networks, earn family income, and claim their space and belonging in the new nation.

More than half a century after Partition, not much has changed for India’s Muslims. If anything, their condition has deteriorated with the exponential rise of Hindu nationalism. In times of everyday backlash and violence against Muslims, the women of Shaheen Bagh bring hope and optimism for India’s democracy. This article urges that momentous milestones like the Shaheen Bagh movement should be located in the longer history of Muslim women’s resilience and their everyday negotiation of state, community and the household. For while the Shaheen Bagh movement attracted women of all ages, of particular importance were the ‘Grandmothers of Shaheen Bagh’ who acquired nationwide popularity as ‘heroes’ of the movement. In an interview with NDTV, 90-year-old Aasma Khatoon, who had not left the protest site for several days, asserted: ‘I won’t leave this country, and I don’t want to die proving I am an Indian’. Similarly, 82-year-old Bilkis said angrily: ‘How is this ever freedom for us? I am having to prove my identity for the last 70 years!’Footnote67 The grandmothers of Shaheen Bagh, like the women I interviewed, have seen it all, and weathered it all. They have faced insecurity and discrimination, but also exhibited tremendous courage and resilience.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the ‘Women, Feminism and Nation-Building Conference’ at Wolfson College and the ‘World History Seminar’ at Magdalene College, University of Cambridge. I am thankful to Joya Chatterji, Uditi Sen and Mytheli Sreenivas for their detailed feedback on draft versions, and also to the two anonymous reviewers of South Asia who helped improve its assertions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. BBC News, ‘Shaheen Bagh: The Women Occupying Delhi Street against Citizenship Law’ (4 Jan. 2020) [https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-50902909, accessed 3 Mar. 2021].

2. Begum Anis Kidwai, Azadi ki Chaon Mein (1949), English translation by Ayesha Kidwai, In Freedom’s Shade, Delhi: Penguin, 2011.

3. Lakshmi Chandra Vashishta, Census of India, Delhi District Census Handbook, Vol. 27 (Delhi: Directorate of Census Operations, 1951), p. xv.

4. See the collection of essays in Christophe Jaffrelot and Laurent Gayer (eds), Muslims in Indian Cities: Trajectories of Marginalisation (London: Hurst & Co., 2012); Vazira Zamindar, The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia: Refugees, Boundaries, Histories (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007); and Nazima Parveen, Contested Homelands: Politics of Space and Identity (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

5. Gyanendra Pandey discusses the making of Delhi Muslims into refugees in their own homes: see Gyanendra Pandey, ‘Partition and Independence in Delhi 1947–48’, in Economic & Political Weekly, Vol. 32, no. 36 (1997), pp. 2261–72.

6. On training and work for refugee women, see Anjali Bhardwaj Datta, ‘“Useful” and “Earning” Citizens? Gender, State and the Market in Post-Colonial Delhi’, in Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 53, no. 6 (2019), pp. 1924–55.

7. Scholars have talked about the persistent presence of small capitalism and its contribution to the regional economy. They describe it as an economic activity that frequently operates at the margins of the mainstream economy and the state, but nevertheless helps maintain community relations and a localised cultural identity. See David Washbrook, ‘South Asia, the World System and World Capitalism’, in Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 49, no. 3 (1990), pp. 479–508; Douglas E. Haynes, Small Town Capitalism in Western India: Artisans, Merchants and the Making of Informal Economy, 1870–1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Tirthankar Roy, Traditional Industry in the Economy of Colonial India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Samita Sen, ‘Gendered Exclusion: Domesticity and Dependence in Bengal’, in International Review of Social History, Vol. 42, no. 5 (1997), pp. 65–86; and Maxine Berg, ‘Skill, Craft and Histories of Industrialisation in Europe and Asia’, in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 24 (2014), pp. 127–48.

8. See Gyanendra Pandey, ‘Can a Muslim Be an Indian?’, in Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 41, no. 4 (1999), pp. 608–29.

9. Mahua Sarkar, ‘Muslim Women and the Politics of Invisibility in Late Colonial Bengal’, in Journal of Historical Sociology, Vol. 14, no. 2 (2001), pp. 226–50.

10. Paola Bacchetta, ‘Communal Property/Sexual Property: On Representation of Muslim Women in a Hindu Nationalist Discourse’, in Zoya Hasan (ed.), Forging Identities: Gender, Communities and the State (New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1994), pp. 188–225; and Rashmi Varma, “(Un)Modifying India: Nationalism, Sexual Violence and the Politics of Hindutva”, in Feminist Dissent, Vol. 2 (2017), pp. 57–83.

11. For several scholarly works on internal displacement, see Zamindar, The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia; Joya Chatterji, ‘Of Graveyards and Ghettos: Muslims in West Bengal, 1947–1967’, in Mushirul Hasan and Asim Roy (eds), Living Together Separately: Cultural India in History and Politics (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 222–49; and Shail Mayaram, Resisting Regimes: Myth, Memory and the Shaping of Muslim Identity (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

12. On gender and Partition, see Urvashi Butalia, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1998); Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin, Borders and Boundaries: Women in India’s Partition (New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1998); Jasodhara Bagchi and Subhoranjan Dasgupta (eds), The Trauma and the Triumph: Gender and Partition in Eastern India (Kolkata: Stree, 2003); and Kavita Daiya, Violent Belongings: Partition, Gender and National Culture in Postcolonial India (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2008).

13. Urvashi Butalia, ‘Legacies of Departure: Decolonisation, Nation-Making and Gender’, in Philippa Levine (ed.), Gender and Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 207.

14. Mushirul Hasan, Legacy of a Divided Nation (London: Routledge, 1997), p. 7.

15. Zoya Hasan and Ritu Menon, Unequal Citizens: A Study of Muslim Women in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004).

16. On gender, space and place, see Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994); Liz Bondi, ‘Gender and Geography: Crossing Boundaries’, in Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 17, no. 2 (1993), pp. 241–6; Linda McDowell, Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies (Cambridge: Polity, 1999); Ghazi-Walid Falah and Caroline Nigel, Geographies of Muslim Women: Gender, Religion, and Space (New York: Guildford Press, 2005); and Farha Ghannam, Remaking the Modern: Space, Relocation, and the Politics of Identity in a Global Cairo (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

17. The interviews drawn upon here were conducted, transcribed and translated between 2016 and 2018 by the author. All names of interviewees are the names told to the author.

18. D.M. Malik, ‘The Tragedy of Delhi (through Neutral Eyes)’, Provincial Muslim League Committee, Mss Eur F164/18, p. 5, the British Library (BL), London.

19. ‘Curfew in Delhi’, Hindustan Times (26 Aug. 1947); and ‘Weekly Diary of Incidents’, 9 Sept. 1947, n.1b, Special Branch, Delhi Police Records, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, (NMML), Delhi.

20. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, India Wins Freedom (New Delhi: Orient Longman, 1988), p. 229.

21. ‘Weekly Diary of Incidents’, 9 Sept. 1947; and ‘A Statement on Delhi Disturbances by a Military Officer on 21 September 1947’, Mss. Eur. F 164/21, p. xli, BL.

22. See Stephen Legg, ‘A Pre-Partitioned City? Anti-Colonial and Communal Mohallas in Inter-War Delhi’, in South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol. 42, no. 1 (2019), pp. 170–87.

23. 26/49-C, chief commissioner Confidential Branch, Delhi State Archives (henceforth, DSA).

24. Vashishta, Census of India, Delhi State District Census Handbook, Vol. 27, p. xv; and V.K.R.V. Rao, Greater Delhi: A Study in Urbanisation, 1940–1957 (New Delhi: Planning Commission, Govt of India, 1965), p. 55.

25. Gyanendra Pandey, Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 122.

26. Azad, India Wins Freedom, p. 230.

27. Malik, ‘The Tragedy of Delhi (through Neutral Eyes)’, p. 19.

28. Mahatma Gandhi, ‘Speech at a Prayer Meeting in Delhi’, 14 Sept. 1947, Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. LXXXIX (Delhi: Publications Division, 1983), p. 185.

29. ‘Distribution of Land Evacuated by Muslim Refugees in Delhi’, 31 Dec. 1947, Rx (5)/48 genl., DSA.

30. See also Rotem Gewa, ‘The Scramble for Houses: Violence, a Factionalised State, and Informal Economy in Post-Partition Delhi’, in Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 51, no. 3 (2017), pp. 769–824.

31. Mahatma Gandhi, ‘Speech at a Prayer Meeting’, 23 Nov. 1947, Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. XC (New Delhi: Publications Division, Govt of India, 1984), p. 127.

32. Census of India, Delhi State District Census Handbook, Vol. 27, p. lxiii.

33. Jalil Abbasi, Kya Din The: A Memoir, English translation by Arif Ansari (Delhi: Notion Press, 2020), p. 135.

34. Fortnightly Reports, Chief Commissioner’s Office, 11 Oct. 1947, CC 1/47/C, DSA.

35. Sachar Committee, Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India—A Report (henceforth, Sachar Committee) (New Delhi: Prime Minister’s High Level Committee, Cabinet Secretariat, Govt of India, Nov. 2006), p. 84.

36. Thomas Blom Hansen, ‘The India that Does Not Shine’, in ISIM Review, Vol. 19, no. 1 (2007), pp. 50–1.

37. ‘Report on the Housing Problem’, Chief Commissioner’s Office, 60/47-C, DSA.

38. Chatterji, ‘Of Graveyards and Ghettos’, pp. 222–49.

39. Sachar Committee Report, p. 14.

40. ‘Letter from Nehru to Vallabhbhai Patel’, 6 Oct. 1947, Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vol. 4, 2nd Series (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 127.

41. ‘Appointment of Social Workers’, R&R 22(3)/1950, DSA. The government recruited well-known nationalist women for social work, mainly from among the families of nationalist elites. It was believed that as women, these social workers would be more sensitive to the needs of displaced women. Mridula Sarabhai was placed in overall charge, and assisting her were Rameshwari Nehru, Kamlaben Patel, Anis Kidwai, Sushila Nayyar, Premvati Thapar, Bhag Mehta, Ashoka Gupta and Damyanti Sehgal.

42. Anis Kidwai, Azadi Ki Chaon Mein, p. 54.

43. Ibid., p. 65.

44. Ibid., p. 18.

45. Ibid., p. 41.

46. Ibid., p. 37.

47. Mahua Sarkar, Visible Histories, Disappearing Women (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2008), p. 49.

48. For elaboration of this paradigm, see Partha Chatterjee, ‘The Nationalist Resolution of the Women's Question’, in Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid (eds), Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990), pp. 233–54.

49. Stephen Legg, ‘Gendered Politics and Nationalised Homes: Women and the Anticolonial Struggle in Delhi, 1930–1947’, in Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, Vol. 10, no. 1 (2003), pp. 7–27.

50. Gail Minault, ‘Begamati Zuban: Women’s Language and Culture in Late Nineteenth Century Delhi’, in India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 11, no. 2 (June 1984), pp. 155–70.

51. Nazir Ahmed, The Bride’s Mirror: A Tale of Domestic Life in Delhi Forty Years Ago, G.E. Ward (trans.) (Delhi: Aleph Books, 2002), p. 72.

52. See Ratnabali Chatterjee, ‘The Queens’ Daughters: Prostitutes as an Outcast Group in Colonial India’, CMI Report R1992:8 (Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute, 1992), pp. 1–34; Sarkar, Visible Histories, Disappearing Women; and Kokila Dang, ‘Prostitutes, Patrons and State: Nineteenth Century Awadh’, in Social Scientist, Vol. 21, no. 9 (1993), pp. 173–96.

53. Chatterjee, ‘The Queens’ Daughters’, p. 21.

54. Joya Chatterji, ‘Dispositions and Destinations: Refugee Agency and “Mobility Capital” in the Bengal Diaspora’, in Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 55, no. 2 (2013), pp. 273–304.

55. Author’s interview with Sakina, 19 Dec. 2017, Delhi.

56. Author’s interview with Rashida, 12 Dec. 2017, Delhi.

57. Author’s interview with Bismillah Begum, 21 Aug. 2016, Delhi.

58. Author’s interview with Raheela, 2 Sept. 2016, Delhi.

59. Author’s interview with Sadia Bano, 28 Aug. 2016, Delhi.

60. Hansen, ‘The India that Does Not Shine’, pp. 50–1.

61. See Mira Mohsini, ‘Crafting Muslim Artisans: Agency and Exclusion in India’s Urban Crafts Communities’, in Clare M. Wilkinson (ed.), Technology, Globalisation and Capitalism (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), pp. 239–58.

62. Hamida Khatoon Naqvi, ‘Shajahanabad: The Mughal Delhi, 1638–1803’, in R.E. Frykenberg (ed.), Delhi through the Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 143–51; and Tripta Verma, Karkhanas under the Mughals: From Akbar to Aurangzeb: A Study in Economic Development (New Delhi: Pragati Publications, 1994), p. 2.

63. Author’s interview with Nagma Bi, 18 Aug. 2016, Delhi.

64. Author’s interview with Amina, 14 Dec. 2017, Delhi.

65. Author’s interview with Ferozah, 17 Dec. 2017, Delhi.

66. Gathered during author’s fieldwork in Delhi in 2017.

67. ‘At Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh, Dadis Unite against Citizenship Law’, NDTV (1 Jan. 2020) [https://www.ndtv.com/video/news/left-right-centre/at-delhi-s-shaheen-bagh-dadis-unite-against-citizenship-law-536691, accessed 6 Feb. 2021].