Abstract

This article traces the evolution of branded commodity advertising and consumption from corporeal health concerns to the racialisation of beauty through skin-lightening cosmetics in late colonial India. It centres two empirical foci: the marketing of personal hygiene products to Indian markets, and their racialised and gendered consumption. This article argues that the imperial economy tapped into and commodified ideals of cleanliness, beauty and fairness through marketing—ideals that continue to pervade contemporary South Asian communities. Contrary to claims that multinational corporations permeated Indian markets after the economic liberalisation of the late 1980s, there is a much deeper genealogy to the racialised imperial economy operating in European colonies. This article also examines the phenomenological underpinnings of imperial whiteness in colonial encounters to demonstrate how certain commodities appealed to Indians as ‘modern’ consumers, as well as how middle-class Indians and local entrepreneurs became active participants in the demand for, consumption and production of personal hygiene commodities.

Introduction

Combining ‘expert planning and supervision with local marketing knowledge’—this promise can be found in a guidebook by the Colman, Prentis & Varley (CPV) advertising agency showing a portfolio of personal hygiene branded products, including toothpaste and tonics.Footnote1 The guidebook boasted of advertising in ‘some seventy territories, using more than twenty-five languages’, and targeted as potential clients transnational companies that exported products to colonial markets.Footnote2 By coalescing vernacularised-local and imperial-global settings, CPV endeavoured to appropriate indigenous ‘needs’ in their advertising narratives. This article traces the evolution of branded commodity advertising and consumption, from corporeal health concerns to the racialisation of beauty through skin-lightening cosmetics, in late colonial India. It centres two empirical foci: the marketing of personal hygiene products in and to Indian markets, and their racialised and gendered consumption. Focusing on health and beauty commodities, this article analyses how the imperial economy commodified ideals of cleanliness, beauty and fairness through branded marketing—ideals that continue to permeate contemporary South Asian communities and markets. There is a longer pre-colonial history to the racial hierarchies and iterations of colourism in South Asia, including the racialisation of geographies and lineages (some groups evoke Kashmir and Punjab, while certain Muslim communities claim Persian and Afghan heritages).Footnote3 However, this article focuses on colonially-sanctioned commodification to argue that ready-made branded products appropriated and racialised corporeal anxieties to offer new conceptions of womanhood and beauty to Anglo-IndianFootnote4 and Indian women, premised upon idealised fairness. More significantly, contrary to claims that foreign companies found their way into Indian markets after the economic liberalisation of the late 1980s,Footnote5 this article argues that there is a much deeper genealogy to the racialised imperial economy operating in European colonies. Multinational firms included Lever Brothers (LB)Footnote6 and Burroughs, Wellcome & Company (BWC), both founded in England, and the Pond’s Extract Company (USA). These firms were budding multinational corporations which expanded through targeting colonial markets across Asia and Africa and the settler dominions.Footnote7

This article also examines the phenomenological underpinnings of imperial whiteness in colonial encounters to demonstrate how certain commodities were incorporated into Indian markets. It teases out how ideals of beauty and health were sold in two ways: by examining English and vernacular print advertising, and by analysing commercial reports to understand how companies envisaged ‘race’ across imperial markets. Upper- and middle-class Indian women were presented with racialised ideals of cosmopolitan beauty and modernity in English- and vernacular-language cross-regional advertisements, which appealed to notions of hierarchical progress by tapping into indigenous tastes and exploiting class and caste stratifications. Douglas Haynes and Timothy Burke have argued that ‘advertisers cannot be seen simply as figures capable of creating out of thin air a “false consciousness” or inventing “false needs” [and instead] must draw in some part upon existing understandings and values to be successful’.Footnote8 I adopt Arjun Appadurai’s and Igor Kopytoff’s conception of commoditisation as lying at the ‘complex intersection of temporal, cultural and social factors’ in which commodities are cognitively and culturally marked as being a ‘certain kind of thing’.Footnote9 In the colonial context, commodities are able to assume independent lives, but ones dependent on ‘concrete material expressions of colonial capitalism’s resources for domination’.Footnote10 This formulation of ‘commodity’ as an unfixed, value-laden entity can be seen in the praxis of middle-class formations and their consumption patterns, in which marked and marketable values are applied to certain products.

Analyses of the marketing reports of manufacturing firms and advertising agencies augment readings of advertisements. These reports provide fascinating insights into the kinds of things firms interpreted as patterns of consumption and custom—anticipating the needs and desires of the ‘natives’. Reading advertisements alongside company reports reveals how adverts were constructed as well as how they came to be read by distinct readers. In many cases, both European and Indian women were targeted simultaneously. Alongside exploring the activities of foreign actors, this article shows how middle-class Indians and local entrepreneurs also played an active role in what Harminder Kaur has called the ‘co-opting’ of European commodities, by adapting existing tastes and bodily practices to cultivate local products.Footnote11 Marketing appealed to the sensory and employed ‘affect’ in advertising messages which enabled both foreign and Indian brands to engage with new consumers of personal hygiene commodities. Thus, Indians were participants in the demand for, consumption and production of personal hygiene commodities, adapting indigenous and foreign commodities to suit evolving needs, desires and tastes as modern consuming subjects.

Corporeal anxieties and anxieties of whiteness

Patent medicines were heavily advertised in vernacular- and English-language newspapers of the early to mid twentieth century, dwarfing other commodities including clothing and food. These Western medical preparations ranged from cures for ailments to strengthening tonics for blood and bones. The popularity of such products reveals the intimate corporeal anxieties of both the English and Indian communities. For the colonial community, these anxieties were indicative of longstanding imperial concerns about health and acclimatisation.Footnote12 Discourses of science and racial weakness played out in product advertising that pledged to eradicate mental and physical deficiencies. Sanatogen tonic promised ‘healthy blood’ and ‘strong nerves’, using jargon such as ‘vitality’.Footnote13 Fears surrounding the degeneration of European blood in India, rooted in late eighteenth century narratives about the temperate climates of northern Europe fuelling civilisation, increased with eugenic theories.Footnote14 The physicality of race gained traction in late nineteenth century ethnographies.Footnote15 These theories also fed into stereotypes about the worth of the native population, particularly in Bengal. European observers noted that Bengali men wore dhotis, easily deprecated as a dress, whilst others assumed the demeanour of women was due to their submission to various gods—in short, Indians were seen to be ruled by womanly men.Footnote16

Many historians and anthropologists have explored how the East India Company, followed by the British Raj, moved away from homogenising Indians within the eighteenth century Orientalist frame of barbaric and backward natives (although these ideas continued to attest to observable differences) to accounting for regionally-categorised racial appellations as territories across the subcontinent were conquered. David Arnold notes that the ‘travelling gaze significantly augmented the institutional one’ in the pre-1857 awareness of regional differences which served the ‘narrativization of place and race’.Footnote17 In response to these enduring associations, Indian elites were eager to assert their variegated articulations of physical equivalence and modern status in burgeoning public spaces by the late nineteenth century. Indian consumers also bought into discourses of the body, some of which followed on from older influences of hygiene originating in the indigenous medicine systems of Unani Tibb (Greco-Arabic medicine) and Ayurveda (rooted in Vedic texts). At various points, indigenous forms asserted independence from, rejected or incorporated aspects of colonial medical expertise and institutions like dispensaries, and later pharmaceutical operations, to appeal to customers.Footnote18 Gangadhar Ray and Neelamber Sen, who established the N.N. Sen and Company Private Limited to undertake large-scale pharmaceutical production, also sold health vitalisers.Footnote19 By the 1920s, competing European and Indian tonic advertisements evoked ‘meanings of special salience to members of the middle class in the making’,Footnote20 meanings about the ideal healthy body and mind.Footnote21

Moreover, colonial medicine played a central role in conceptualising the darker skin tones of colonised people as signs of racial degeneration, following colonial ethnographers. H.H. Risley most prominently advocated for the biological classification of Indian society at the turn of the twentieth century by promoting the use of anthropometrical tools to argue that physical characteristics were the best ‘test of race’, as opposed to Sir William Jones, who articulated the race affinity of Indo-European languages in the 1870s.Footnote22 These conceptions of race endured into the twentieth century whereby the Anglo-Indian community continued to rearticulate the boundaries of whiteness along class, wealth and birth lines as well as skin colour; these configurations were reflected in the commodities on offer.Footnote23 Brands such as Sphagnol peddled a range of British-made soaps, creams and ointments to women as part of holistic self-care packages ‘for tropical skin troubles’.Footnote24 In this way, connections between medicine and racial health were reinforced as well as tackled via popular consumption. These advertisements, in newspapers read by English-speaking Indians, also fed into wider discourses of, and intimate connections between, cleanliness and civilisation.

Civilising soaps and the ‘Indianisation’ of soap

The domestication of empire manifested in reforming various sartorial, behavioural and household practices. Observing cleanliness methods, Europeans were impressed by the regular bathing habits of Indians and were willing to integrate cold baths into daily routines as measures for toughening bodily fibres.Footnote25 But practices such as rubbing oil on bodies and chewing paan (betel leaf) were seen to be repulsive and malodorous.Footnote26 This aversion to Indian odours featured in European constructions of dirt and smell and the need to preserve health, purity and strength on the colonial stage.Footnote27 A manufactured desire for cleanliness and whiteness, as Radhika Mohanram notes, was premised on a fading sense of smell whereby ‘white[ness] was to be dislocated from carnality’.Footnote28 By 1840, health was as integral to Britain’s imperial identity as commerce and agriculture.Footnote29 Regional public health and education departments instituted training in hygiene and inspections in hospitals, dispensaries and schools in response to ongoing public health concerns.Footnote30 In this context, the use of soap was imbued with symbolic meanings of progress for Europeans and Indians alike. The ‘prior meanings’ attached to particular commodities, which buttressed their use in local settings, finds a compelling example in Indian soap use.Footnote31 Soap was not prevalent in Indian households in the early nineteenth century; instead, soap-nuts, flours, oils and homemade concoctions were popular. By the last two decades of the century, however, soap had become a crucial part of disease prevention and sanitary hygiene. Kaur notes that ‘the use of western conceptions of cleanliness to perceive Indian civilisation as inferior had a profound impact on the western-educated Indian elite’.Footnote32

Associations between soap use and civility manifested in the inculcation of hygienic practices amongst poorer Indians too. In a memoir penned in the 1930s, the American Irene Bose writes of a request made by a Parsi mill manager for her to undertake health work amongst the women workers and their children. Concluding that ‘cleanliness came first’, Bose and her staff taught women to wash with soap and oil and to comb their hair, a project that meant ‘supplying soap, oil and combs for four thousand women and girls’.Footnote33 The attention to ‘cleanliness first’ and soap instruction demonstrates the palpable cultural and symbolic value that soap represented to Western observers, arming themselves and sermonising the civility of soap in colonial encounters.Footnote34 Thus, as a ‘civilising’ signifier, soap came to represent a modern device for cleanliness for emerging middle-class Indian consumers who reworked their relationships to homemade cleansing concoctions.

Crucially, personal hygiene advertising signalled the broader contours of transition among growing urban populations in cities like Bombay (now Mumbai) and Calcutta (now Kolkata), where conspicuous consumption and domestic economy denoted behaviours indicative of a rising middle class. Advertising branded soap and personal hygiene products involved the navigation and manipulation of sensory ‘affect’. Here, affect signifies visceral forces of feelings, emotions and intensities transmitted onto bodies through what Sianne Ngai calls the predicaments posed by a state of obstructed agency as colonial subjects.Footnote35 Srirupa Prasad, in a study of colonial Bengal, has considered affect in evoking connections between advertisements and the cultural politics of hygiene, as well as the consumption of affective things as variously provoking imbuement and resistance in the embodiment of new practices and ideas.Footnote36 The engendering of affect in soap advertisements was key to distinguishing it as a modern cleansing implement. Anne McClintock’s incisive deconstruction of late nineteenth century Pears soap sales campaigns exposits how the reproduction of images of colonised peoples not only fed into imperial dialogues of civilisation (white children literally rubbing black children ‘clean’ with soap), but sustained British attitudes towards empire.Footnote37 These objects appealed to existing imperial sentiments about the role of the white race in the world and found resonance in Indian advertising—appealing to pre-existing concerns with hygiene and racial affinities. McClintock also argues that there was a shift from scientific racism to ‘commodity racism’.Footnote38 In India, however, this scientific racism was combined with commodity racism in advertising directed at colonial subjects. The ‘social life of commodities’ was imbued with new meanings and values.Footnote39 This measure of civility was taken up by aspiring Indian elites in response to expressions of superiority and colonial racism. Responses were indicative of Homi Bhabha’s articulation of colonial mimicry and ambivalence: the coloniser’s desire to create ‘a reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of a difference that is almost the same, but not quite’.Footnote40 This reading of ‘almost the same, but not quite’ translates to a gendered affect of beauty in the consumption and material self-fashioning of aspiring middle-class women—including instances of emulation that could be performed with and without (un)conscious desires to ‘transform one’s own identity after the fashion of the other’.Footnote41

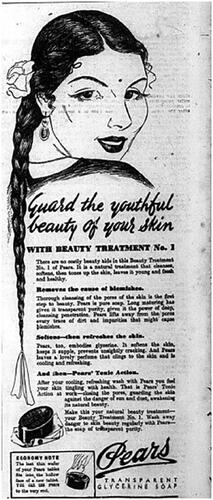

Inter-war marketing strategies shifted from selling soap for clothing and bodies as part of hygiene regimens to retailing soap as a cosmetic for women.Footnote42 Pears soap was taken over by LB in 1917 and toilet soaps became beauty soaps.Footnote43 Pears advertisements in vernacular- and English-language newspapers specifically targeted Indian women from the 1920s onwards (). The woman is identifiably Indian through several sartorial signifiers: the first, floral hair adornment, was noted in many investigatory marketing reports;Footnote44 other identifiers of long plaited hair (signifying Indian) and a bindi (signifying Hindu marriage) portray a married Indian woman.

Figure 1. Advertisement for Pears soap (Oct. 1940). Source: The Illustrated Weekly of India (Bombay) (20 Oct. 1940), p. 51, British Library, London.

One can infer that the married woman is imparting her beauty wisdom to help other women succeed in the marriage market and secure that bindi. It also points to the affective reification of happiness and security: these feelings are intimately embodied in and connected to the use of specific technologies. Such inferences became bolder in the sale of beauty and fairness creams. The textual detail also represents a major shift from earlier advertisements of the Pears brand which included minimal text and literally let the image do the talking. In contrast, a step-by-step guide and daily regimen was provided. The use of the terms ‘natural beauty’ and ‘transparent purity’ alongside ‘young and fresh and healthy’ are also noteworthy.

Many social reformers and commentators critiqued progress in women’s education by arguing that literate women would imitate the behaviours and artifice of memsahibs.Footnote45 Anxieties about ‘natural beauty’, or beauty perceived to be natural, saturated mass print. These anxieties betrayed the concerns of women imitating or being mistaken for undesirable others who adorned themselves in particular ways, including those defined as ‘bazaari’ women connoting loose women, courtesans or prostitutes or the multifaceted ‘modern girl’, all of whom were cited in critiques of, and resistance to, modernity. Thus, the respectability politics of artifice were articulated in the intimate relational and patriarchal discourse of various communities. Foreign companies made sure to temper the affect of branded products by incorporating a familiar lexicon into their advertising copy. The use of ‘transparent purity’, for instance, elicited culturally-affective reactions about the maintenance of caste purity as an end goal to beauty. In Gandhian thought, pollution was vital in a ‘vocabulary of contagion and hygiene’ and was part of a never-ending process of self-disciplining over the consumption of food, medicine and other desires such as sexual urges and lusts for wealth.Footnote46 Although soap as a means to achieving whiteness was not explicitly stated in Lux or Pears advertisements, as it had been in earlier European ones, the undertones of a racialised hierarchy through the employment of modern ‘pure and white’ coalesced with the vocabulary of purity in readings of how the commodity worked.

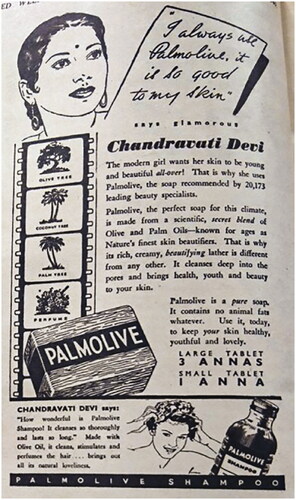

Brands such as Lux and Palmolive also started using Indian and Hollywood endorsements in their advertisements (). This advertisement carries a testimonial from Chandravati Devi, an actress known for the 1935 cult classic, Devdas. The text states that the ‘modern girl wants her skin to be young and beautiful all-over’, which can be achieved through using beauty soaps.

Figure 2. Advertisement for Palmolive soap (Nov. 1940). Source: The Illustrated Weekly of India (Bombay) (6 Oct. 1940), p. 2, British Library, London, UK.

Notions of romantic love and the glamour of the cinema are employed to depict an ideal of beauty. Cinema became a cultural weapon for advertising branded goods and lifestyles in magazines.Footnote47 Appealing to the visual in cinema ‘reinforced the place of photography as an enduring frame of reference’.Footnote48 Part of the appeal of motion pictures came from the ‘modern fantasies of control’ and experiences that they imagined visually for audiences.Footnote49 Neepa Majumdar suggests that, from the 1930s, the glamour and appeal of early Indian stardom and cinema was combined with cultural elements.Footnote50 Reformist associations such as the Brahmo Samaj (founded in 1861) and Arya Samaj (founded in 1875) were concerned with ‘cleaning up’ particular images of Indian society, such as the purported depravity of nautch (dancing) girls and devadasis (temple dancers), to dictate the development of a cultural nationalistic discourse.Footnote51 Similarly, attempts were made to morally improve cinema and redeem it from its bad reputation through the growing installation of ‘the cultured lady’—that is, educated, upper-class women working as actresses. Anticipating the direction of advertising in the post-war period, an LB report noted that ‘Pears beauty appeal will be linked up either with the work of Indian artists or with photographs of leaders of Indian feminine society’.Footnote52 Thus, foreign advertisers were successful in part because they were able to visualise cultural elements through actor testimonies which emphasised the smell and texture of soaps, transporting the private, intimate-affective act of tactile application into the public imagination via cinema reels (from the late 1940s) which reached a growing subsection of cinemagoers.

Endorsements were also effective tools in navigating concerns about quality and authenticity. Preoccupations with making wise consumer choices appeared across the Urdu, Hindi and Bengali press.Footnote53 A regular ‘House Management’ (Khanadaari) column in the Urdu-language magazine Ismat emphasised the use of good genuine soap (achhi khalas sabaan).Footnote54 Concerns about the authenticity of branded soaps were not unfounded: imitation by local and international competitors constantly plagued administrators at LB and BWC, and competition from local manufacturers as well as American, Swiss and French companies grew rapidly in the inter-war period.Footnote55 As early as 1907, competitors were accused of copying the designs and packaging of more established brands such as Pears and Sunlight. A March 1916 letter from LB to a trader in Madras (now Chennai) complained that the use of similar packaging by some retailers and manufacturers was designed to actively mislead consumers.Footnote56 The company also attempted to get reassurances from retailers across India not to sell imitation products.Footnote57

Soap-use advertisements evolved to include both evocations of cleansing with progress and associations between racial health and beauty. Soaps and cosmetics became mimetic devices for attaining physical whiteness in attempts to achieve the status that whiteness represented.Footnote58 However, alongside creating demand and positing idealised images of health and beauty, businesses and advertising agencies responded to evolving local specificities. How did soap manufacturers adapt their approach to focus on the values and sensibilities of Indian women? Bhabha has asserted that ‘mimicry repeats rather than re-presents’.Footnote59 This is certainly true of the pre-war period of soap advertising before companies started to tap into Indian identifiers. Rather than soap being indigenised by local businesses incorporating popular Indian ingredients into products, as suggested by Kaur, we see a distinct ‘Indianisation’ of soap in local advertising campaigns that appealed to Indian women.Footnote60 Indian entrepreneurs capitalised on the popularity of floral and herbal scents to create homogenised, nationalised and identifiable symbols of Indianness. The Bombay-based Godrej company, for instance, launched Vatni soap in the late 1930s, a name taken from the turmeric body salve used in Hindu and Muslim weddings.Footnote61

Despite local competition, British corporations continuously worked on expanding their consumer bases by appropriating local sensory knowledge and appealing to cultural affect, using the vast amounts of power and capital at their disposal. A 1935 LB report noted the popularity of perfumes in India and recommended that the company work on incorporating scents like sandalwood into their products.Footnote62 Here, it is worth taking time to consider the epistemological bounds of knowledge-making. Countless reports on peoples, places and patterns of consumption enabled advertising and manufacturing firms to interpret customs, both real and imagined. CPV popularised their mantra, ‘markets are people’, by illustrating common advertising mistakes, including a food manufacturer ‘whose Indian advertisements showed the food held left-handed—because nobody had told him that food so touched in India offends the caste system’.Footnote63 This attempt to get into the minds of discrete Indian consumers, particularly upper-caste Hindus with greater purchasing power, via data collection exercises was inherently extractive, reminiscent of and borrowing from tools of colonial domination—ethnographies and censuses.Footnote64 CPV was not alone; information-gathering exercises were either outsourced to advertising agencies or undertaken by specialist departments made up of purported field experts. Native agents were also hired for language expertise and to act as local vendors.Footnote65

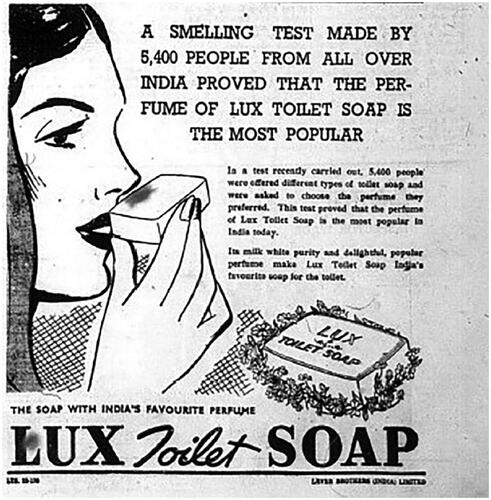

A 1938 sourcing report from another prolific advertising agency, J. Walter Thompson Company (JWT), reads just like a colonial information-gathering exercise in its attempts to ascertain Indian purchasing potential: ‘the individual family income is infinitesimal, but collectively the village population has considerable earning power’.Footnote66 Thus, foreign companies capitalised on colonial readings of the tactile body and transformed them to create commodifiable corporeal objects. The real and imagined renderings of knowledge gained from such field operations were used to understand distinctions along regional, religious and linguistic lines, and were consistently incorporated into visual and textual storytelling via sartorial details and physical appearances. In other words, advertisements produced knowledge, but this knowledge was ‘produced from something already known’—to fill gaps, agencies needed to know what to fill.Footnote67 In the Lux soap campaign, images of Indian women were used to evoke a nationally-inclusive project of finding India’s favourite scent for soaps (). Once again, LB appealed to touch and smell to incorporate the senses into a holistic consumption project. Rather than the absence of smell that had marked earlier hygienic whiteness, the acts of feeling the texture of soap and smelling bars to choose Indian aromas that clung to the urban modernising body-in-the-making indicate how companies responded to indigenous tastes and the evolving, independent life of the commodity. This kind of advertising continued across other mid twentieth century personal commodity and luxury advertising.

Figure 3. Advertisement for Lux soap (Oct. 1940). Source: The Bombay Chronicle (Bombay) (4 Oct. 1940), p. 9, Centre for South Asian Studies, Cambridge, UK.

There was also nascent local competition across India. During World War I, there had been a decrease in foreign imports and a growth in local production with (often) nationalistic underpinnings such as the Bengal Chemicals and Pharmaceutical Works Limited—which became the first drug factory to be owned and managed by Indians—creating a ‘pluralistic marketplace’.Footnote68 Businesses like Mysore Industries tapped into the appeal of scents by using locally-sourced oils, and the Calcutta Chemical Company promoted the medicinal qualities of the neem tree in its soap promotion.Footnote69 These companies leveraged their local knowledge whilst borrowing from the advertising techniques of Western companies. The manufacture of the soap brand Hamam by Tata, today a major Indian multinational conglomerate, undercut sales of Lux toilet soap due to its cheaper cost and Swadeshi appeal; nevertheless, it employed JWT to design ‘attractively wrapped’ and ‘modern packs’.Footnote70

Many others wanted a piece of the soap pie too. Local entrepreneurs attempted to take advantage of emerging class sensibilities through various heuristic resources. In 1938, Hanuman-Prasada Goyal published Vyapara aur Kari-Gari, a Hindi-language book of recipes for preparing homemade soap, oils, hair lotions and scents so that unemployed individuals could capitalise on the hygiene commodity market.Footnote71 Soap was also indigenised with the use of vegetable oils instead of animal fats, including those manufactured by the Godrej company. Such experimentation tapped into upper-caste Indian values and tactile sensibilities. Companies emphasised that soaps were ‘untouched by hand’ and made without animal substances to play into the dichotomous relationship between purity and pollution in food preparation and somatic regulation amongst Muslims and high-caste Hindus. The consumption of soap also spoke to caste mobility and aspiration in the absence or cultivation of specific smells. Like the selection of caste-neutral surnames,Footnote72 consumption of or abstention from foods (like meat) was a way for lower castes to emulate Brahmans and other upper sub-castes.

Manuals, pamphlets and magazines published from the end of the century also included recipes for homemade composites for personal use. Some of these responded to, and resolved, fears about preparation and frugality. In some instances, soap-making was also articulated as a legitimate way for struggling middle-class women to make money inside their homes.Footnote73 In this way, Indians were active participants in the consumption and production of this commodity, buying into narratives of civility, modernity and status engendered by sensory appeals. These associations continued to develop with the evolution of other beautifying agents.

From civilising soaps to beautifying creams and skin lighteners

There has been a considerable amount of attention paid to the contemporary, globalised marketing of skin-lightening products in the late twentieth century.Footnote74 Studies have documented the use of skin lighteners, also referred to as ‘skin whiteners’, ‘skin bleachers’ or ‘depigmenting agents’, in Africa, Europe, North America and Asia, which often contain harmful chemicals like hydroquinone and mercury.Footnote75 In India, the skin-lightening market was estimated at over US$250 million out of a total dermatology market of US$410 million.Footnote76 Researchers have utilised post-colonial, transnational feminist frameworks in their analysis of cosmetic consumption, Eurocentric beauty ideals, and the role of the entertainment industry (such as Bollywood) in perpetuating ideals of fairness and colourism.Footnote77 Many sociologists attribute the growth of beauty cosmetics in India to economic liberalisation.Footnote78 In her study of global skin-lightening markets, Evelyn Glenn suggests that only a few skin-lightening products were available to Indian women before 1991.Footnote79 However, I argue for a re-evaluation of these claims and historicise their use within a racialised capitalist-imperial economy. Despite Nehruvian economic policies of closing markets to foreign competition, the practice of establishing subsidiaries enabled corporations to navigate this policy. British multinational firms established subsidiaries inside India’s tariff walls by making a substantial turn to local manufacturing. The Indian subsidiaries of LB (Hindustani Vanaspati Manufacturing Company and Lever Brothers Limited) and United Traders sold personal hygiene and cosmetic preparations.Footnote80 The tendency to connect the growth of the skin-lightening market with the liberalisation of the economy from the late 1980s onwards obscures the prowess and manoeuvring of British power brokers, amongst others, in ensuring their foothold in Indian markets after 1947. Field reports from the late 1940s reveal how administrators attempted to follow political developments to determine the state of Indian, and then Pakistani, markets.Footnote81 One such subsidiary, Hindustan Unilever Limited, established in 1933 as Lever Brothers, launched the (now) infamous Fair & Lovely skin whitener in 1975, often marked as the first commercial skin-lightening cream on the Indian market. Fair & Lovely is the best-selling skin-whitening cream in the world, holding a commanding 50–70 percent share of the skin-lightening market in India in 2006.Footnote82

The marketing of fairness technologies demonstrates an evolution from portrayals of civilising medicines and hygienic soaps between the 1890s and 1920s to more explicit messages about idealised beauty and fairness in the 1930s and 1940s. Economic and political incentives do differ, but, as Prasad notes, the juxtaposition of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and the present neo-liberal moment highlights the importance of affect in charting trajectories of public hygiene and health.Footnote83 During the 1920s, most advertisements focused on ‘clear’ complexions and protecting the skin from the climate. However, terms such as ‘bleaching’, ‘whitening’ and ‘vanishing’ became more prominent, initially targeting European women in the colonies.

One of the earliest cold creams to be sold in the Indian market as a skin-whitening cream was BWC’s Hazeline brand from the first decade of the twentieth century. Jessica Clark has shown that a whole array of products had been used in Victorian England to attain a natural English rose complexion in opposition to darker Mediterranean tones, promising to keep ‘skin soft smooth and white in all seasons’.Footnote84 In the cases of Hazeline Cream and Hazeline Snow, they were initially sold as medicinal cold creams alongside medicines and first-aid kits catering to colonial communities.Footnote85 Gradually, however, they were marketed as beauty creams by reinforcing connections between racialised health and beauty and accentuating their lightening properties: ‘beautifying the skin, making it soft and white’.Footnote86 The ideal English rose complexion took on a further racialised impetus for English women living in the colonies who marked themselves apart from an additional set of undesirable others—the ‘natives’, poor white domiciled communities, and ‘Eurasians’ (mixed-race communities). At the same time, the machinery of cinematic ‘stardom’ continued as Hollywood models and other prominent women promoted complexion aids.Footnote87 Early twentieth century Eurasian actresses were instantaneously visibilised as white, and Hinduised by selecting Hindu names to appeal to Indian audiences: Sulochana (Ruby Myers), Sita Devi (Renee Smith) and Sabita Devi (Iris Gasper).Footnote88 Later, in the 1930s and 1940s, popular actresses such as Durga Khote and Devika Rani, though playing very different kinds of heroines, were both appropriately fair, Indian, and upper caste and upper class.Footnote89 Thus attaining fairness or lightness (as equivalent to whiteness) was a classed, caste-based and racialised aspiration, perpetuated in a modern way on screen.

From the turn of the twentieth century, BWC had been increasingly occupied with protecting its trademark from infringement.Footnote90 Administrators noted the difficulty of using one trademark ‘in all countries and for all time’.Footnote91 More specifically, BWC had to contend with imitations of the Hazeline name in the Indian market because many businesses were able to appropriate the use of ‘-ine’ by subverting irregular international trade laws. In 1944, LB agent Gourley noted the saturation and profitability of beauty creams in Indian markets and the popularity of Hazeline: ‘creams do not have a penetration quite equal to powders but are still accepted as a normal need in most households from the middle-class upwards, particularly in the form of “Snows” regarded to some extent as medicinal products…. The demand is overwhelmingly for Vanishing or Foundation cream’.Footnote92 The report compared sales of the Oatine brand, Hazeline Snow, Pond’s Vanishing Cream and local Snows including Pattanwalla Snow and Himani Snow. It recommended adding ‘Rexona Snow’ to the company’s existing Rexona line to capitalise on the popularity of facial cosmetics.Footnote93 The choice to extend ‘Rexona’, a line sold in other colonial markets too, would well be understood by Indian consumers as a play on the Indian girl’s name Ruksana, thus constructing a veneer of Indianisation for the LB brand.

Naming complexion creams ‘Snow’ and the use of mountain and snow imagery proved popular due to associations with fairer and whiter skin. In one imitation, Mehta Bhuta & Company of Bombay had to apologise to BWC for simulating the style of Hazeline Snow advertising, namely the ‘predominant use of snow-clad mountain’.Footnote94 BWC’s concern with securing sole use of this motif certainly attests to its popularity and resonance with Indian consumers. Mountains were recognisable as racialised entities—hill stations linked elite social life, northern climates and racialised genealogies. One popular localised Snow product that employed such lineages was Afghan Snow, produced by Ebrahim Sultanali Patanwala of Bombay. It was advertised as an ‘Indian Face Cream’, selling authenticity as well as distance and difference from foreign-owned Snows to appeal to nationalist sentiment (similar to Godrej’s soap-selling strategy).Footnote95

Alongside Hazeline creams, Pond’s creams were the most popular creams of the early twentieth century, manufactured by Pond’s Extract Company. In 1916, JWT devised a new marketing strategy for Pond’s Vanishing Cream and Pond’s Cold Cream to persuade women to incorporate both into their daily beauty regimen.Footnote96 A JWT scoping report for Pond’s hinted at a colour hierarchy amongst ‘well off’ Indian women who paid ‘attention to their complexions…depend to a large extent upon their colour’. Footnote97 This observation reminds us that a racialised imperial gendered hierarchy was not originated by such products but consolidated and commodified by them. Accounting for different women, the report singled out ‘olive-skinned or light-brown’ Parsi women as ‘more westernised’ and European in their ‘standards of beauty’ and noted other colour gradations.Footnote98 The degree to which marketers attempted to create a standardised colour chart, which often failed to match observable realities yet became widely accepted by Europeans and Indians alike, speaks to the visual and textual entrenchment of ‘colourism’ that was navigated through skin lightening.

Indeed, ‘The Modern Girl in the World’ Group, in their transnational comparison of beauty advertisements, suggests that Pond’s creams’ images conveyed the message that women could achieve ‘real beauty’ regardless of, or traversing, caste and class—attaining whiteness through the use of lightening agents helped to neutralise caste and classed identities.Footnote99 From the late 1930s, two key strategies were implemented by marketers: the use of images associated with science and modernity, and images that foregrounded enlightened domesticity, often portrayed simultaneously. Pond’s creams’ advertisements also proffered narratives of the burgeoning but contested ‘new woman’ of the aspirant middle classes: the ‘modern married housewife’ and the ‘modern girl’ in complementary and competing ways—indicative of negotiations around modernity, urbanisation and conjugality. They often epitomised a younger ‘modern girl’, not necessarily married, going out to work, to college, to shop and to socialise.Footnote100

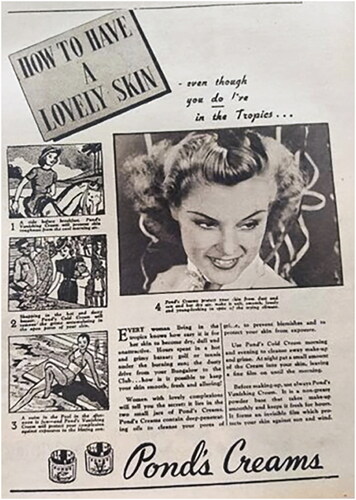

targeted white women with the slogan, ‘How to have a lovely skin even though you do live in the Tropics’.

Figure 4. Advertisement for Pond’s Creams (Oct. 1940). Source: The Illustrated Weekly of India (Bombay) (6 Oct. 1940), p. 63, British Library, London, UK.

Another English Pond’s advertisement used an image of an Indian woman with the sartorial markers of a dupatta (scarf) and bindi to address Indian readers.Footnote102 Like the Pears soap advertisement, it included a detailed description of the benefits of using Pond’s as well as an instructional beauty regimen. This stylistic form would be familiar to Indian audiences used to following the prescriptions (nukshas) provided in vernacular-language domestic manuals and by medical practitioners. Although ‘whitening’ was not mentioned explicitly, women were encouraged to use cold and vanishing creams to ‘eliminate all impurities from the skin’, for a ‘glowing’ skin and for ‘protection against the sun’—in other words, protection from tanning and becoming darker. A comparable coded lexicon was also inscribed in the vernacular—Urdu-language domestic manuals employed the language of colour preservation (rang ki hifazat).Footnote103

This advertisement also linked the use of creams to attractiveness and focused on what one would gain: ‘what a delight to meet the admiring smiles of your husband and friends…to know that [you] look attractive’ and ‘nothing wins admiration quicker than your skin’. In this way, Ponds could be used as a resource to garner social capital. Here, I utilise Margaret Hunter’s exposition of Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘social capital’ to propose how beauty work generates forms of social, cultural and racial capital.Footnote104 Social capital enabled the middle-class married woman to maintain respectability and gain status amongst friends and family. Prasad notes that domesticity in Bengal was the centrifugal focus of early beauty and hygiene advertisements: whitening creams targeted Bengali women so that they could become fairer like their European counterparts, but depicted them in the home space rather than in the public realm like representations of European women.Footnote105 A 1949 Urdu-language advertisement () was formatted like an English-language Indian-targeted one; again, the images and text were changed to suit the publication’s readership.

Figure 5. Advertisement for Pond’s Creams (June 1949). Source: Shama magazine, Abdul Majeed Khokhar Yadgar Library (Gujranwala) and EAP566, British Library, London [https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP566].

![Figure 5. Advertisement for Pond’s Creams (June 1949). Source: Shama magazine, Abdul Majeed Khokhar Yadgar Library (Gujranwala) and EAP566, British Library, London [https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP566].](/cms/asset/ec3a53b8-ea45-423a-9d65-fa15c15e644e/csas_a_1968599_f0005_c.jpg)

This advertisement also presented two complementary visual and textual narratives. The larger visual image depicted explicit identifiers that marked the woman as Muslim through the draping of the dupatta over her head and the absence of a bindi. It played into the ‘modern girl’ narrative; unlike the earlier Pond’s advertisement, this advertisement does not mention a husband. The start of the text translates as: ‘Make the colour (rang) of your face beautiful (khoobsurat) and attractive (dilkash) and maintain it using Pond’s two creams. To quickly give yourself beautiful and translucent (shafaf) colour’. Rather than asserting that Pond’s creams made skin beautiful, the advertisement promised that creams made skin colour more beautiful and attractive. Beauty was commoditised alongside the products themselves to suggest that beauty could be acquired. The instructions were accompanied by an image of a white woman, marked by fairer skin and the absence of indigenous sartorial symbols, using the product. This image attempted to give the commodity racialised authority. Whiteness, through the mediation of fair skin coded as an ideal, was an aspiration attained by utilising beautification as a transformative form of capital. This capital could ‘buy’ other things: social and/or familial admiration and better marital prospects. Many other variations of the Pond’s advertisements portrayed fictionalised Indian women as representative archetypes, such as Shanti, the wife of an ‘ambitious young political worker in Delhi’, in order to target various women.Footnote106

Pond’s marketing transformed the consumption of a commodity into a ‘need’—a need that appealed to the reification of affect by representing routes for women to gain coveted ways of being and feeling. Soap had represented a tangible route to purity and civilisation and lightening creams a way to achieving gratifying relationships and happy homes, both underpinned by progress and modernity. The plurality of advertising confirms the interdiscursivity between health and beauty. It also points to a hermetically racialised schema which marketed the same products in different ways, employing racialised, regionalised and religious portrayals of women to perpetuate specific ideals of beauty and femininity. Storytelling strategies about self-fashioning and mobility sold fairness to all communities indiscriminately but exploitatively, playing upon desires for whiter or lighter skin and caste mobility as well as adherence to individual family and community values and identities.

Skin-lightening commodity advertisements spoke to female consumers by virtue of being situated within broader beauty discourses connected to indigenous rituals and shopping practices and within other self-fashioning opportunities. In this socio-cultural landscape, ‘things out of jars’Footnote107 were rapidly becoming popular as ready-made, easier-to-apply products in urban middle-class spaces by the mid twentieth century. These developments are reflected in the growing number of publications written for, and by, women. For instance, similar to concerns over achha soap, misgivings about the contents and types of creams were also part of the textual dialogue of the 1930s and 1940s—Ismat’s column Khanadaari (Household Management) entreated women to apply a ‘good well-prepared (achhi si banawati) kind of cream or lotion’.Footnote108 From the mid 1940s, the use of other cosmetics (from lipstick to nail varnish) offered by European firms such as Goya and BourjoisFootnote109 represented the next step to achieving a highly-racialised, globalised, superior and modern beauty standard.

Conclusion: Commodifying corporeality and marketing fairness

Numerous skin-lightening methodologies existed in colonial India and were enacted in subversive and playful ways by a range of interlocutors who dispensed advice and offered different and often contested ways of self-fashioning the body. This article, however, has focused on connections between the historical construction of civilisational hygiene, racial health, colourism and marketisation. The pervasiveness of colourism was fuelled and exploited by Western multinational companies who expanded their consumer bases in colonial markets through extractive and exploitative processes. Manufacturers commoditised intimate bodily practices alongside institutional imperial practices—a praxis which also influenced reforms in vernacular instructional literature about hygiene, health and beautification. Data-gathering techniques, developed in earlier colonial encounters, were honed by a new set of business interlocutors who targeted Indians as active consumers. Aspirational stories of health, conjugal and familial love, success, and ways in which to be ‘modern’ were proffered using culturally affective and racialised imagery depending on the targeted consumer space. Earlier health commodities focusing on blood and bodily racial prestige evolved into heightened aesthetic concerns about skin colour in the creation of an idealised beauty in caste and class formations. Fair skin, as the dominant beauty ideal, was depicted in ways that offered women chances or resources in their own communities, and in emerging occupational and educational spaces. Local manufacturers also tapped into these specific needs and desires, particularly in the cultivation and utilisation of customary scents. As such, branded hygiene and beauty became increasingly popular and normalised in the 1930s and 1940s as part of household and hygiene regimens.

Compared to today’s fairness creams, which are explicitly advertised as fairness or bleaching creams, colonial-era marketers employed numerous subterfuges to illustrate the ‘lightening’ and colour ‘cleansing’ effects of the soaps, creams and powders they promoted. They tapped into notions of racialised fairness as well as Indian assumptions about particular products. By maintaining consistent imagery and marketing techniques between soap and cosmetic advertisements, advertisers relied on accumulated and assumed knowledge about how soap cleanses and protects the skin to ‘do the work’ of showing how beauty creams worked too. Indeed, current global marketing strategies continue to envelop consumers in these affect-dependent stories. By understanding how this commodification and narrative-making occurred after the turn of the nineteenth century, we are able to think through some of the most enduring, unconscious and nascent representations and idealisations of racialised health, colour and beauty, and perhaps start to dismantle them.Footnote110

Acknowledgements

This article is based on my doctoral thesis, ‘Race, Gender, and Beauty in Late Colonial India c.1900–1950’, University of Cambridge, UK, 2021. I extend my thanks to the special issue editors, Christin Hoene and Vebhuti Duggal, the South Asia reviewers of this article, and Dr. Leigh Denault for their useful comments and feedback. Images have been included with permission from the British Library and the Centre for South Asian Studies, Cambridge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Colman, Prentis & Varley (CPV), ‘Marketing Throughout the World’, c. 1940s–1950s, HAT/21/73/9, History of Advertising Trust, Raveningham, UK.

2. CPV, ‘Export Advertising 1947–1948’, HAT/21/73/1A/1–32, History of Advertising Trust, Raveningham, UK.

3. I interrogate such genealogies, associations and representations of race and colour in colonial ethnographies, Hindu scriptures and vernacular mass print elsewhere: see Mobeen Hussain, ‘Race, Gender, and Beauty in Late Colonial India c.1900–1950’, unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2021.

4. Here, Anglo-Indian refers to the English colonial community living temporarily in India.

5. Evelyn Nakano Glenn, ‘Yearning for Lightness: Transnational Circuits in the Marketing and Consumption of Skin Lighteners’, in Gender and Society, Vol. XX, no. 3 (June 2008), pp. 281–302 [290]; and Kavita Karan, ‘Obsessions with Fair Skin: Color Discourses in Indian Advertising’, in Advertising & Society Review, Vol. IX, no. 2 (July 2008), pp. 1–23 [1].

6. Lever Brothers merged with Dutch Margarine Unie in 1929, resulting in a portmanteau of both companies to Unilever. Many of its business operations continued to use ‘Lever Brothers’.

7. Geoffrey Jones, Merchants to Multinationals (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 288.

8. Douglas E. Haynes, ‘Creating the Consumer? Advertising, Capitalism and the Middle Classes in Urban Western India, 1914–40’, in Douglas E. Haynes et al. (eds), Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 185–224 [186].

9. Arjun Appadurai (ed.), ‘Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value’, in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 3–63 [11, 13]; and Igor Kopytoff, ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process’, in Arjun Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 64–92 [64].

10. Timothy Burke, Lifebuoy Men, Lux Women: Commodification, Consumption, and Cleanliness in Modern Zimbabwe (London: Leicester University Press, 1996), pp. 5, 10.

11. Harminder Kaur, ‘Of Soaps and Scents: Corporeal Cleanliness in Urban Colonial India’, in Douglas E. Haynes et al. (eds), Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 246–67 [261].

12. Amina Mire, ‘“Skin Trade”: Genealogy of Anti-Ageing “Whiteness Therapy” in Colonial Medicine’, in Medicine Studies, Vol. IV, nos. 1–4 (May 2014), pp. 119–29 [120].

13. ‘Sanatogen’, in The Illustrated Weekly of India (Bombay) (25 May 1930), p. 40.

14. David Arnold, ‘Race, Place and Bodily Difference in Early Nineteenth-Century India’, in Historical Research, Vol. LXXVII., no. 196 (May 2004), pp. 254–73 [225].

15. Ethnographies include H.H. Risley, The People of India (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co., 1915).

16. Indrani Chowdhury, ‘The Effeminate and the Masculine: Nationalism and the Concept of Race in Colonial Bengal’, in Peter Robb (ed.), The Concept of Race in South Asia (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 282–303 [282].

17. Arnold, ‘Race, Place and Bodily Difference in Early Nineteenth-Century India’, pp. 263, 254.

18. Seema Alavi, Islam and Healing: Loss and Recovery of an Indo-Muslim Medical Tradition, 1600–1900 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), pp. 185–6; and Kavita Sivaramakrishnan, Old Potions, New Bottles: Recasting Indigenous Medicine in Colonial Punjab (1850–1945) (New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2006), p. 89.

19. Srirupa Prasad, Cultural Politics of Hygiene in India, 1890–1940: Contagions of Feeling (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), p. 96.

20. Haynes, ‘Creating the Consumer?’, p. 94.

21. Pernau explores how josh (vigour or passion) permeated the language of vitality and virility in Urdu discourse on the body, mind and character: Margrit Pernau, Emotions and Modernity in Colonial India: From Balance to Fervor (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 8.

22. Arnold, ‘Race, Place and Bodily Difference in Early Nineteenth-Century India’, p. 261; and Risley, The People of India.

23. For Anglo-Indian anxieties about whiteness, see Satoshi Mizutani, The Meaning of White: Race, Class, and the ‘Domiciled Community’ in British India 1858–1930 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); and Christopher Hawes, Poor Relations: The Making of a Eurasian Community in British India, 1773–1833 (London: Routledge, 1996).

24. ‘Sphagnol’ advertisement, Bombay Chronicle (Bombay) (1939), Cambridge South Asia Archive, Cambridge, UK.

25. Elizabeth Collingham, Imperial Bodies: The Physical Experience of the Raj, c. 1800–1947 (Oxford: Polity, 2001), p. 45; and Pratik Chakrabarti, Medicine and Empire: 1600–1960 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p. 58.

26. Kaur, ‘Of Soaps and Scents’, p. 249.

27. Early sites of imperial concern about tropical diseases were the Imperial Navy and the colonial armed forces: see Chakrabarti, Medicine and Empire, p. 50.

28. Radhika Mohanram, Imperial White: Race, Diaspora, and the British Empire (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), p. 106.

29. Mark Harrison, Climates and Constitutions: Health, Race, Environment and British Imperialism in India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 173.

30. Reports of the Director of Public Health, IOR/V/24/3704–708, India Office Records and Private Papers, British Library, London, UK.

31. Burke, Lifebuoy Men, Lux Women, p. 6.

32. Kaur, ‘Of Soaps and Scents’, p. 253.

33. Irene Bose, Unwoven Carpet of Hindustan—Memoir: From Time to Time Throughout Her Life in India, c. 1930s, Irene Bose Papers, Centre for South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, pp. 13–4.

34. Industrial sites were early test subjects for colonial ‘civilising’ experiments: see Rajnarayan Chandavarkar, Imperial Power and Popular Politics: Class, Resistance and the State in India, c. 1850–1950 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 243.

35. Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), p. 3.

36. Prasad, Cultural Politics of Hygiene in India, 1890–1940, pp. 20–1.

37. Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest (New York: Routledge, 1995), p. 214.

38. Ibid., p. 32.

39. Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

40. Homi Bhabha, ‘Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse’, in Discipleship: A Special Issue on Psychoanalysis, Vol. XXVIII (Oct. 1984), pp. 125–33 [126], italics in original.

41. Ngai, Ugly Feelings, p. 143.

42. Foreign manufacturers also capitalised on marketing different soaps for different uses in colonial Rhodesia: see Burke, Lifebuoy Men, Lux Women, pp. 150–7.

43. Haynes also notes this trend in Bombay newspapers: see Haynes, ‘Creating the Consumer’.

44. Report on India, Burma and Ceylon Compiled on the Basis of Messrs. Lehn and Fink’s Questionnaire, J. Walter Thompson Company, Bombay, June 1931, Reel 225, p. 21, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

45. Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1994).

46. Prasad, Cultural Politics of Hygiene in India, 1890–1940, p. 59.

47. Kaushik Bhaumik, ‘At Home in the World: Cinema and Cultures of the Young in Bombay in the 1920s’, in Douglas E. Haynes et al. (eds), Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 136–55 [141].

48. Sudhir Mahadevan, A Very Old Machine: The Many Origins of the Cinema in India (New York: SUNY Press, 2015), p. 53.

49. Tom Gunning, ‘Doing for the Eye What the Phonograph Does for the Ear’, in Richard Abel and Rick Altman (eds), The Sounds of Early Cinema (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2001), pp. 13–31 [29].

50. Neepa Majumdar, Wanted Cultured Ladies Only! Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s–50s (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), p. 10.

51. Charles Heimsath, Indian Nationalism and Hindu Social Reform (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1964), p. 113.

52. A.D. Gourley, ‘India Report of Mr A.D. Gourley on His Visit 1944: Advertising in the Post-War’, UNI/RM/OC/2/2/46/42, p. 4, Unilever Archives, Port Sunlight, UK.

53. An advertisement for the Himani brand noted that ‘only things with [the] Himani logo are up to the mark, and trustable’: ‘Himani’, in Banglalakshmi (Calcutta) (Feb. 1932).

54. Mohammad Zafar, ‘Khanadaari’, in Ismat (New Delhi) (Nov. 1932), pp. 425–8 [425–6].

55. Late nineteenth century technological advancements reduced trading times, enabling colonial peripheries to be integrated into the global economy.

56. ‘Imitation Cases Letters 1916–17’, letter dated 10th Mar. 1916, AFP/4/7/2 (6)-(8), Unilever Archives, Port Sunlight, UK.

57. Ibid.

58. Komal K. Dhillon, ‘Brown Skin, White Dreams: Pigmentocracy in India’, unpublished PhD dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2015, p. 40.

59. Bhabha, ‘Of Mimicry and Man’, p. 128.

60. Kaur, ‘Of Soaps and Scents’, p. 262.

61. Ibid., p. 261.

62. Mark Vardy, ‘Report on India, Burma and Ceylon, January 1935’, UNI/RM/OC/2/2/46/24, p. 56, Unilever Archives, Port Sunlight, UK.

63. CPV, ‘Marketing Throughout the World’ (1947–48).

64. Broader cyclical capitalist (neo-)colonial practices included exploiting labour and extracting raw commodities for the manufacture of consumer goods, then selling the goods back to colonial subjects, buying out smaller business competitors, and setting up colonial subsidiaries.

65. European firms scrambled to open separate departments for data collection: see Burke, Lifebuoy Men, Lux Women, p. 125.

66. Notes on Indian Advertising, J. Walter Thompson Company (Eastern Limited), Bombay (1938), India 1938–1939, Reel 232, p. 1, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, NC.

67. Judith Williamson, Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising (London: Marion Boyars, 2002), p. 99.

68. Prasad, Cultural Politics of Hygiene in India, 1890–1940, pp. 96–7.

69. ‘The Industrial Growth of Mysore’, in The Illustrated Weekly of India (10 Oct. 1937), pp. 32–3; and Vardy, ‘Report on India, Burma and Ceylon, January 1935’, p. 55.

70. Sidney van deh Bergh, ‘Mr Sidney van deh Bergh’s Report on Lever Bros. (India) Ltd. Business March 1936’, UNI/RM/OC/2/2/46/31, p. 7, Unilever Archives, Port Sunlight, UK; and Vardy, ‘Report on India, Burma and Ceylon, January 1935’, p. 55.

71. Hanuman-Prasada Goyal, Vyapara aur Kari-Gari (Benares: Bhargava-Pustaka-laya, 1938).

72. Gyanendra Pandey, A History of Prejudice: Race, Caste, and Difference in India and the United States (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 208–9.

73. For instance, Mawlana Thanvi, Bahisti Zewar (1901), advised on making and selling soap for ashraf (respectable) Muslim women.

74. Evelyn Nakano Glenn, Shades of Difference: Why Skin Color Matters (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009); and Radhika Parameswaran and Kavitha Cardoza, ‘Melanin on the Margins: Advertising and the Cultural Politics of Fair/Light/White Beauty in India’, in Journalism & Communication Monographs, Vol. XI, no. 3 (Sept. 2009), pp. 213–74.

75. Many governments have taken steps to ban these chemicals: see Lynn M. Thomas, Beneath the Surface: A Transnational History of Skin Lighteners (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020).

76. Shyam B. Verma, ‘Obsession with Light Skin—Shedding Some Light on Use of Skin Lightening Products in India’, in International Journal of Dermatology, Vol. XLIX, no. 4 (Mar. 2010), pp. 464–5 [465].

77. Meeta Rani Jha, The Global Beauty Industry: Colorism, Racism, and the National Body (London: Routledge, 2016); and Samra Adeni, ‘The Empire Strikes Back: Postcolonialism and Colorism in Indian Women’, unpublished MA dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2014.

78. Anita Anand, The Beauty Game (New Delhi: Penguin, 2002), p. 37.

79. Evelyn Nakano Glenn, ‘Consuming Lightness: Segmented Markets and Global Capital in the Skin-Whitening Trade’, in Evelyn Nakano Glenn (ed.), Shades of Difference: Why Skin Color Matters (Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2009), pp. 166–87 [178].

80. Amar K.J.R. Nayak, Multinationals in India: FDI and Complementation Strategy in a Developing Country (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), p. 29.

81. ‘Notes on the Political Situation in Indian Pakistan, 1949’, UNI/RM/OC/5/32, Unilever Archives, Port Sunlight, UK.

82. Aneel Karnani, ‘Doing Well by Doing Good: Case Study: “Fair & Lovely” Whitening Cream’, in Strategic Management Journal, Vol. XXVIII, no. 13 (Dec. 2007), pp. 1351–7 [1352].

83. Prasad, Cultural Politics of Hygiene in India, 1890–1940, pp. 20–1.

84. Jessica P. Clark, The Business of Beauty: Gender and the Body in Modern London (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020), p. 9; and Rose & Lily Skin Cream, c. 1890–99, EPH136, Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

85. Souvenir of the First Universal Races Congress, London, 1911, Burroughs Wellcome & Co., Cambridge University Library, Cambridge, UK.

86. ‘Three Dummy Jars of Hazeline Snow in Presentation Box’, WF/M/Obj/15, Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

87. The begum of Bhopal described Hazeline products as health and beauty aids in her health manual: see Sultan Jahan, Hifz-i-Sihhat (Preservation of Health) (Bhopal: Sultania Press, 1916).

88. Majumdar, Wanted Cultured Ladies Only!, pp. 69, 115.

89. Ibid., p. 79; and Bhaumik, ‘At Home in the World’, p. 152.

90. Cases of brand imitation with German and Japanese manufacturers’ correspondence, WF/L/06/177, Box 4, 1928, Burroughs and Wellcome, London, UK.

91. Correspondence dated 23 Aug. 1928, F/L/06/177, Box 44, Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

92. Gourley, India Report 1944, p. 43, emphasis added.

93. Ibid., p. 44.

94. ‘Trademark Correspondence 1887–1939’, letter dated 6th Oct. 1922, WF/L/06/194, Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

95. ‘Afghan Snow’, Hindustan Times (New Delhi) (10 May 1931), p. 14.

96. Geoffrey Jones, Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Industry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 100.

97. Report on India, Burma and Ceylon Compiled on the Basis of Messrs. Lehn and Fink’s Questionnaire (1931), p. 37.

98. Ibid.

99. The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group and Alys Ev Weinbaum (eds), ‘The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device: Collaboration, Connective Comparison, Multidirectional Citation’, in The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), pp. 1–24.

100. The ‘modern girl’ was read by many as a disruptor of familial ties and patriarchal norms.

101. Margery Hall, ‘And the Nights Were More Terrible than the Days’: Autobiography c. 1938–1947, Mss Eur F226/11, pp. 19–20, India Office Records and Private Papers, British Library, London, UK

102. ‘Pond’s Creams’ advertisement, in The Illustrated Weekly of India (Bombay) (6 Oct. 1940), p. 63, British Library, London, UK.

103. See Sultan Jahan, Hifz-i-Sihhat.

104. Hunter argues that beauty is a crucial resource for women operating at the level of social capital: see Margaret L. Hunter, Race, Gender, and the Politics of Skin Tone (New York: Routledge, 2005).

105. Prasad, Cultural Politics of Hygiene in India, 1890–1940, p. 105.

106. All India Women’s Conference: Journal Roshni, 1946–48 (Feb. 1947), Or.Mic.14127, India Office Records and Private Papers, British Library, London, UK.

107. Ikramullah, a politician from an elite Muslim family, disparaged branded products as ‘quick fixes’: see Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah, Behind the Veil: Ceremonies, Customs, and Colour (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 36.

108. Zafar, ‘Khanadaari’, in Ismat (July 1937), pp. 185–7 [187]; other magazines also debated these issues, including Bangalakshmi (Bengali) and The Indian Ladies Magazine (English).

109. CPV represented Goya and Elizabeth Arden.

110. Unilever recently announced the replacement of ‘Fair’ in their brand-name Fair & Lovely with ‘Glow’ to include ‘diversity’ in beauty. However, the choice of ‘Glow’ is reminiscent of early twentieth century advertising. The rebranding responded to contemporary social-political sentiments (including Black Lives Matter protests) without any systematic recognition of and recourse to the company’s complicity in racist messaging and racial capitalism: Unilever information published on 25 June 2020 [https://www.unilever.com/news/press-releases/2020/unilever-evolves-skin-care-portfolio-to-embrace-a-more-inclusive-vision-of-beauty.html, accessed 25 June 2020].