Abstract

This paper traces the centrality of rivers in twentieth-century and contemporary popular music and poetry in the regional context of Punjab in the north-west of the subcontinent. In contrast to the riverine imaginations in the songs of eastern or central India, we look at the very different evocations of rivers—both real and conceptual—in the subcontinent’s north-west. Rivers feature centrally in the love legends, devotional and folk poetry, and songs of Punjab, and here we trace a river-based ‘hydropoetics’ in Punjab, querying land-focused perspectives. From the metaphysical and the sacred to the sensual, and from the realms of the quotidian to those of mourning and trauma, we argue that in Punjab, ‘singing the river’ is central to people’s definitions of regional and ontological identity, and to the way they understand their place in the world.

Introduction

This paper was prompted in part by an observation made by Punjabi scholar-singer Madan Gopal Singh, who expressed a sense of disturbance at ‘the way we as a people have related to our rivers’, noting ‘a distinct absence of celebrative songs of rivers in our folk memory’, when compared to other regions criss-crossed by rivers, like Bengal.Footnote1 The deeply mystical genre of songs dedicated specifically to river(s) in eastern (e.g. the bhaṭīyālī boat song genre) and central India are sung in praise, awe and reverence of rivers, and personify them as a sacred mightier Other. Such songs are certainly absent in the Punjab, likely on account of the shorter courses of its rivers, when compared to the vastly lengthy courses of the Brahmaputra, Ganga or Narmada rivers. Beyond geographical reasons, there are also linguistic and cultural ones that link the region to Perso-Arabic literary traditions, which could explain why Punjab and Sindh’s rivers have not primarily been apotheosised as mother goddesses, in the way rivers like the Ganga, Yamuna, Narmada and Godavari have been.Footnote2

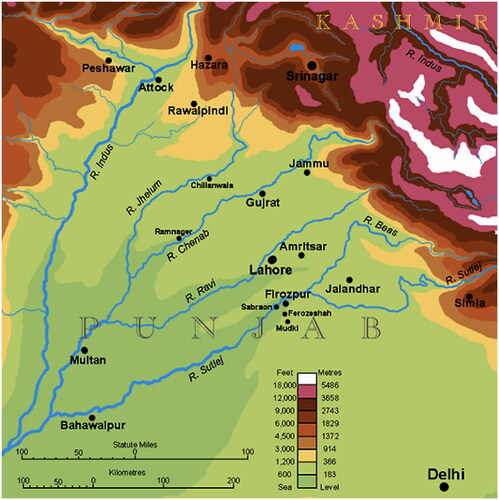

However, as the evidence presented below shows, instead of an absence in Punjab’s folk memory, there is, in fact, a ubiquity, even omnipresence, of the river as metaphor. Equally embedded in this folk memory are cultural, regionally-specific understandings of each of the five rivers—from east to west, Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab and Jhelum, all tributaries of the Panjnad river, itself a tributary of the mighty Indus.Footnote3 Over the past 200 years, each of these rivers has acquired multiple, shifting meanings ().

Figure 1. Topographic map of Punjab, ‘The Land of the Five Rivers’. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Footnote50

In this paper, we examine the range of political associations, regional ascriptions, and the ontological and mystical meanings that Punjab’s rivers acquire through an analysis of folk songs, proverbs, poetry, and recorded and film music in modern and contemporary Punjab: across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, leading up to the present. Through the verses on water in Punjabi song and poetry discussed here, we argue that across time, the river as metaphor, and the five rivers as symbols, are centrally tied to representations of the Punjab’s landscape and cultural geographies. These songs and poems reveal how rivers function as a crucial part of the Punjabi cultural identity—both in regional cartographic terms and in affective terms through a literary and sonic engagement of all the human senses. The broader framework relevant here is that of ‘hydropoetics’, which recognises ‘human interdependencies with rivers’, foregrounding the ‘inherent language of rivers’ (rather than simply ‘giving voice’ to them).Footnote4 Using the lens of Punjab’s rivers as they figure in the worlds of performed music and poetry, then, we connect to the wider questions about ecology, identity and culture in South Asia, with which this Special Section engages.

Throughout Asia, as Sunil Amrith argues, ‘dreams and fears of water’ have shaped visions of political independence and economic development across time, outlining the cultural centrality of water, oceans and rivers, especially to the subcontinent.Footnote5 Ray and Madipatti’s edited volume further explores the longue durée intersections between the environmental and the cultural, arguing how material cultures of water generate technological but also aesthetic acts of envisioning geographies in South Asia.Footnote6 Such acts of envisioning geographies through rivers come organically to Punjab and Sindh, since the etymologies of both stand out in their derivation from a riverine connection. Punjab (lit. ‘five rivers’) was so named during the reign of the sixteenth-century Mughal emperor Akbar. The historian J.S. Grewal points out that Punjab was the land of six, not five, rivers, and that the name ‘Punjab’ itself was originally given to the Lahore province to cover the five doabs (interfluvial plains) of the region.Footnote7 Given the current political borders between east and west Punjab, the three eastern rivers are controlled by India (Sutlej, Ravi, Beas), while Pakistan controls the three in the west (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab).Footnote8

Anjali Gera Roy has argued how, in Punjab, the new colonially sanctioned borders replaced a landscape and geography informed by natural markers like rivers.Footnote9 The emphasis on the so-called fertility of Punjab’s land is also grounded in a specifically colonial transformation of the Punjab landscape through canal colonies that diverted water from the Sutlej and Jhelum rivers to the new canal colonies in west Punjab. David Gilmartin’s recent history of the Indus river basin in modern history has revealed the links of Punjabi social and cultural history with the different phases of the Indus basin’s transformation after 1850. Gilmartin notes the praise often reserved for British government engineers, who entered the folk poems of people benefitting from the waters newly flowing near their fields.Footnote10 These colonial era transformations leave their mark on the present, with central Punjab strongly associated with tropes of ‘fertility’ ever since the transformations of irrigation under British rule. In contrast, the people in the Cholistan desert of south-west Punjab have a very different relationship with water, one mediated by scarcity, resulting in an abundant genre of river songs, as studied by Nasrullah Khan Nasir.Footnote11

The primary aim of this essay is to emphasise ‘rivercentrism’ in the Punjab’s spatial and affective geographies, contrasting this with the prominence of land (zamīn), as codified in proverbial triangulations like ‘zar, zamīn, zan, jhagṛe kī jaṛ haiṅ (wealth, land and women are the root of all conflict)’, which normalise a terracentric view of Punjabi regional identity.Footnote12 Distinct from such proverbs, we seek out those axioms and songs that centre round rivers and waters, as for example in a popular adage emphasising the indivisibility of water—‘pāṅī soṭā māreyāṅ kadī do nahī hunde (even when beaten by a stick, water will never divide into two)’—commonly invoked to build unity in the face of family feuds. In contrast to this proverb, though, water-sharing disputes continue to riddle the region today, especially in India, where the Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) canal—still under construction—is at the heart of a five-decade-old conflict between the state of Punjab and that of neighbouring Haryana. The emotional charge behind this dispute is evident in the 2022 song ‘SYL’, written and composed by the recently assassinated singer-politician Sidhu Moosewala. He placed water at the heart of Punjabi statehood, sovereignty and a belligerent cultural hegemony, with the forceful main refrain of the controversial song noting: ‘Ho Jinnā Chir Sānū Sovereignty Dā Rāh Nī Dende, Onhān Chir Pānī Chhaddo, Tupkā Nī Dende (O, those who deny us the path to sovereignty/To them (we say), forget water, we shan’t give you a single drop)’.Footnote13

Thus, we stress the Punjabi interdependence on the ‘panj darīyā’ or five rivers, which are axiomatic not only in the region’s eponymous name, but also in its inhabitants’ mental mapping, epics, water-sharing settlements and performance practices, to recover the inherent language of the rivers. Through this, we unsettle the ‘terracentrism’ implicit in socio-cultural and political constructions of Punjabi regional identity by drawing on Ryan’s idea of hydropoetics and hydrocentricism to propose an ecopoetics of Punjabi folk and popular song. The paper is divided into three sections: Section 1 explores liquescent metaphors of the five rivers through the twentieth century, Section 2 examines their mystical and political dimensions, while Section 3 delineates Punjab as a trans-river land in the post-1947 world.

The ‘panj darya’ in folklore and song

This section examines the five rivers (panj darīyā) of Punjab through folklore, proverbs and some popular songs from the twentieth century. Gera Roy’s insight about rivers functioning as natural borders in pre-colonial Punjab is encapsulated in a wonderful Punjabi saying that compresses folklore, cultural identity and historical memory all in one:

Rāvī Rashkāṅ, Chenab Āshqāṅ, Sutlej Salīkāṅ, Sindh Sādiqāṅ, Jhelum Fasīqāṅ.

Ravi: the land of people of honor, Chenab: the land of lovers, Sutlej: the land of seekers of spiritual enlightenment, Sindh: the land of the true Masters, Jhelum: the land of transgressors (from the path of love).Footnote14

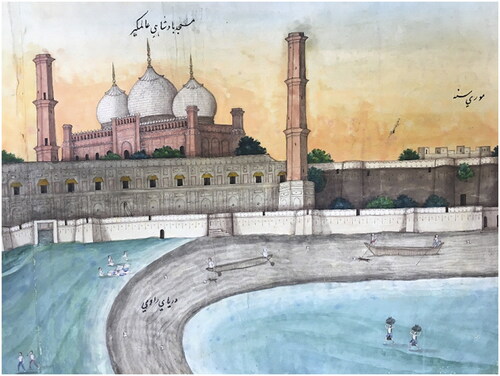

Ucchṛā Burj Lahore Dā, Nī Aisāṅ Goriye,

Uhde Heṭh Vage Rāvi Darīyā

The Tall Minaret of Lahore is such O’ beautiful/fair-skinned girl

The river Ravi flows beneath it.Footnote15

Figure 2. A section showing the ‘Ravi Darya’ or Ravi river flowing next to the Lahore city walls, against the minarets of the Badshahi/Alamgiri Mosque.

Source: Hand-painted scroll, ‘Panoramic Depiction of the Fort and Old City Walls of Lahore’, late eighteenth–early nineteenth century. © The British Library Board.Footnote51 Image courtesy: Radha Kapuria.

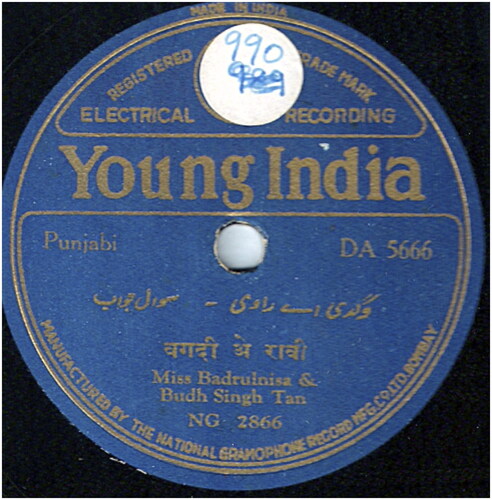

The use of the term ‘vag’ (akin to the Hindi word, ‘bah’, with the same meaning, ‘to flow’) is evident in several other folk and popular film songs that feature the Ravi river. One of the earliest pieces of recorded music featuring this sense of the ‘flow of the Ravi’ comes from a pre-Partition recording produced by Bombay’s ‘Young India’ record label, made no earlier than 1935. It was a duet sung by two Punjabi artistes, Miss Badrulnisa/Badrulnisa Begum and Budh Singh Tan, titled ‘Vagdi Aye Ravi’, available at the British Library’s sound archive. A brief excerpt from the song, with our translation, follows. In the familiar sawāl-jawāb (question-answer) tradition of Punjabi song and poetry, the first paragraph is in Badrulnisa’s voice, where the woman addresses her male lover, while the second verse is the man’s response, rendered in Budh Singh’s voice:

Vagdī e Rāvī, māhī ve

Vich pair uchhāle ḍholā

Phaṛ laye munḍeyā, māhī ve

Hun ulṭe chāle ḍholā

The Ravi flows, oh darling

And in it splashing his feet (is) my beloved

You have picked up now dear boy, oh darling

Many wayward ways, my beloved

Gall gavāīye, māhī ve

Ajj kal dīyāṅ kuṛīyan, ḍholā

Kamm na dhandhe, māhī ve

Sab gallī dunīyā, ḍholā

Singing their words, oh darling

Are the girls these days, my beloved

No work or business, oh darling

The whole world just talks (these days), my beloved.Footnote18

Figure 3. Disc Label for the Young India record, ‘Vagdi Aye Ravi’.

Source: CEAP190/9/43 Endangered Archives Programme (EAP190).

‘Vagdī e Rāvī’ is also the theme of Punjabi folk māhīyā love songs, and featured in the 1956 song by talented Pakistani singer Kausar Parveen, and a more famous later version rendered by vocalist Ustad Asad Amanat Ali Khan of the Patiala gharānā of rāgadārī (raga-based) music.Footnote19 Different versions of the same phrase, ‘Vagdī e Rāvī’, also occur in songs by Pakistani folk singers Ataullah Khan Esakhelvi, Arif Lohar and Bushra Siddiqui, and the Indian singer Satinder Sartaaj, whose 2011 song offers a personification of each river in an affective register, akin to speaking of one’s friends or family.Footnote20

The trope of the Punjabi term ‘vag’ or flow connects with the notion of ‘free-flowing cartographies’ proposed by Anjali Gera Roy.Footnote21 Emphasising that Punjab’s geography is based ‘on a history of flows, crossings, travels and mobilities rather than on moorings, fixity or closure’, Gera Roy uses this metaphor to describe the pre-colonial and colonial era mobilities of nomads, traders and seers within the region, playing out across its rivers and passes. This notion is particularly useful in our emphasis on the liquescence of rivers, which subverts the borders of both nation and region.

In a final example of the liquescent ‘vag’ metaphor, ‘Vagdi-e-Ravi’ is also the title of a song written by Khawaja Pervaiz (1930–2011) from the 1987 Pakistani film Faqeeria (dir. Wahid Dar), sung by the legendary singer Noor Jehan (1926–2000) and back-up female vocalists. Composed in a peppy rhythm and an uplifting melody by Wajahat Attray, the song, sung entirely by women, would be well placed in a ‘ladies saṅgīt’ setting of a contemporary Punjabi wedding. The lyrics, however, are sombre, likening the dangers of the Ravi’s whirling waters to wearing love’s heavy chains:

Vagdī e Rāvī, de vich

Uḍḍan pambhīrīyāṅ

Gall vich pyār diyāṅ

Pāīyāṅ ne zanjīrīyāṅ

Innāṅ Kaddī Nī Gall Choṅ Lainā

Lai gaīyāṅ te maiṅ nahī rehnā.

The Ravi flows, and within it

Rise spinning whirls.

In my neck I wear (as a necklace)

Love’s heavy shackles

Never remove these from my neck

If someone does, then I will cease to live.Footnote22

The celebration of love and sexuality through destructive metaphors is a typically Punjabi cultural trait, recalling Prakash Tandon’s description of the ubiquitous phrase, ‘mar jāvāṅ (may I die)’, in contexts of intimacy and desire as a culture-wide manifestation of the Freudian ‘death wish’.Footnote23 The song also deserves attention for its unique visual composition, set on the banks of a river surrounded by scenic hills. The space of the river—including the riverbank and the boats on it—is central to the song’s visualisation. All three converge to form a joyous all-female space, unfettered by the male gaze, with the female protagonist dancing with abandon—even in a spirit of exultation and enjoyment (). Indeed, the protagonist seems to derive joy from her state of being ‘chained’ in love. The Pakistani actor Mumtaz performs a fast-paced choreography to match the song, most notably swirling both arms in circular fashion to mimic the dangerous whirls or ‘pambhīrīyāṅ’ rising in the Ravi (see ).

Figures 4A, 4B and 4C. Video stills for the song ‘Vagdī e Rāvī De Vich Uḍḍan’, sung by Noor Jehan, from Faqeeria (1987). In the top two images, Mumtaz and other actors dance on boats, while in the bottom image, Mumtaz dances on the riverbank, her hand gestures imitating the whirls of the river.

Source: Famous Films Youtube channel, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC2trCrqHZqIFG64bsm9gklw.

The lyrics, choreography and visual composition of this song recall an older and more popular Noor Jehan melody, also written by Khawaja Pervaiz. Originally featured in the 1973 Pakistani film Dukh Sajnan Dey, the song, ‘Sānū neher vāle pull te bulā ke, te khaure māhī kitthe reh gayā (After calling me to the bridge on the canal, I wonder where my beloved is now lost)’, similarly features the female protagonist dancing near a gushing canal.Footnote24 The song’s main refrain features the female heroine reprimanding her beloved for lacking the courage to join her at the bridge on the canal. In contrast to the 1987 song from Faqeeria, here the heroine dances alone. Common to both songs, however, is the connection of flowing water bodies to the transgressive female voice, on the verge of subverting the bonds of community honour by choosing her own lover. The two songs, then, also capture the uniquely liminal aspect of rivers, and flowing water bodies in general—these are locations marking the heroine at a threshold of change, in a liminal situation between maidenhood and womanhood. To follow van Gennep, who first coined the term ‘liminality’, in both examples, the river becomes the site for a ‘rite of passage’, symbolising an initiation into the world of sexuality for the heroine, who expresses agency and autonomy in choosing both her lover and the circumstances for this transition.Footnote25

As with the connections drawn between water and womanhood in the two Noor Jehan songs or in the proverb ‘Ucchṛā Burj’, gender is typically at the heart of several wedding songs referring to water, including the following ṭappā sung at Pakistani Punjabi weddings:

Tere koloṅ ṭurnā sikhe panj darīyā de pānī,

Jā tū koī heer saleṭī jā koī phoolāṅ rānī.

The River learns its flow by your gait,

Either you seem beautiful lass, or an adorned princess.Footnote26

Mystical and political dimensions

Apart from folk poetry and song, rivers have provided ample material for Punjab’s tradition of mystical poetry, from Guru Nanak to Bulleh Shah, and going back to the Rig Vedic hymns from ancient India. The connection of Punjab’s rivers with spirituality was made in a somewhat different way by modern, twentieth-century Punjabi writers. Puran Singh (1881–1931), considered the first to introduce free verse poetry in modern Punjabi, wrote ‘Punjab de Darya’ (1923), which captures this vividly, while personifying each of the rivers as a friend. The poem plays close attention to the sensuality of the river and to the very sounds of the ‘flow’ of the mighty rivers: ‘Khāṛ Khāṛ’ and ‘Lehrān Dī Thāth’. Singh also refers to the sixth river, the ‘Attock’ (yet another tributary of the Indus, located in western Punjab in Pakistan), pointing to the longer folk memory of Punjab as a land of six or more rivers, not five:

Rāvī Sohnī Payī Vagdī

Mainūṅ Sutlej Pyārā Hai

Mainūṅ Beās Payī Khichdī

Mainūṅ Channā ‘Vājāṅ Mārdī

Mainūṅ Jhelum Pyār Dā

Aṭak Dī Lehrān Dī Thāth Mere Būhe Te Vajdī

Khāṛ Khāṛ challan vich mere sapneyān

Panjāb de Daryā

Pyār Agg Inhānooṅ Lagī Huyī

Pyārā Japu Sāhib Gāunde

Thanḍe te ṭhār de, Pyār de.

The Ravi, so beautifully it flows

The Sutlej is beloved to me

The Beas pulls me (towards itself)

The Chenab calls out to me

The Jhelum gives me love

The roar of Atak’s waves sounds at my doorstep

Khāṛ Khāṛ (they rush) through my dreams;

The rivers of Punjab.

All aflame with the fire of love

They sing the beloved Japu Sahib

Cool and refreshing, offering love.Footnote28

Mardānē dī rabāb vajī,

Parbatāṅ salām kītā

Būṭā būṭā vajad vicha nachiā,

Panjāba dī mitṭī dā zarrā zarrā kabiā pyār vicha

Usey ilāhī sur vicha dariā paey vagade

Eh naveṅ sajre barafānī darīyavāṅ dā desa hai.

Mardana’s rabāb sounded

And the mountains saluted in response

Every little bud danced, lost in a state of rapture

Every little particle of Punjab’s soil trembled, in love;

In that very heavenly note the rivers flow

This is the country of rivers freshly formed of icy glaciers.

Vich Panjāb Farogh Karende Panj Darīyā Manmoṇe

Panjāṅ Dā Panjāb Banāyā Nām Panjā De Soṇe

Jhelum, Sutlej, Rāvī, Beās, Chenāb, nī Saīyyo!

Within Punjab do thrive the charming five rivers

All five made Punjab, and the names of all five are beautiful—

Jhelum, Sutlej, Ravi, Beas, Chenab, oh beloved!Footnote29

Figure 5. Disc Label for the Young India record for the Punjabi song, ‘Sona Desan Vichon Des Punjab’.

Source: CEAP190/9/51 Endangered Archives Programme (EAP190).

In contrast to the way in which rivers figure in such nationalist visions of India, there is a very different use of Punjab’s rivers in the writings of Lal Singh Dil (1943–2007), Punjabi poet of the Naxalite (Marxist-Leninist) movement and revolutionary anti-caste activist. Dil’s poem, ‘Song to the Sutlej’, part of the collection Sutlej di Hawa (1971), written during the poet’s time in prison, captures an abiding love affair with the Sutlej and its breeze, marked by an emotion of great intimacy towards it:

Sutlej dīye vāye nīṅ

Prīt tere nāl sāḍī, vāye nīṅ

Phir assīn kol tere āye nīṅ

Dil pehchān sāḍā, uṭh ke

Sir assīn nāl ṇā liyāye nīṅ

Āye sattān sāgarāṅ nuṅ chīr ke

Pāṇī tereyāṅ de tarhāye nīṅ

Pyār terā chhohe jeṛhe dil nūṅ

Oh sūrajāṅ dī agg ban jāye nīṅ

Bīj oh baghāvatāṅ de bīj dā

Gīt oho azādīyāṅ de gye nīṅ

O the breeze of Sutlej,

We have an attachment of love with you, o, dear breeze

Again, we have come so close to you.

Rise and know our hearts,

We have brought our heads along, for you.

We have come, cutting across the seven seas,

Thirsty for your waters.

Were your love to touch any heart,

That heart would turn into the flames of the sun

It would sow the seeds of rebellions

And sing the songs of many freedoms.Footnote31

Maiṅ tainūṅ sāhāṅ vich, bāhāṅ vich takeyā

Kyūṅ jū Raj Bhavanān de gande sāh

Chhū nā sake terī pāk ātmā

Tūṅ inhāṅ beṇāṅ vichoṅ utthdī

Jinhāṅ deyāṅ dukhī Dillāṅ

Kadde Bukkaṛāṅ vich sāmbe

Lahore diyāṅ phāīyāṅ toṅ lāhey huye shahīd

I saw you in my breaths and my arms,

For the filthy breath of the houses of power

Could not dare touch your pure soul.

You rise from those banks, whose gloomy hearts

At one time cherished in their embrace

The martyrs removed from the gallows at Lahore.

Ethey har saver, rāt te dopahar, shām saughī hondī

Gīt ethey uthde

Dūr choteyāṅ de chalde, vag chār de jawāk, pāṇī langhde

Maiṅ tainūṅ udās takdā

Tere uṛde pallu, jazbeyāṅ de jazīreyāṅ val, mere bādvāṅ baṇ de

Maiṅ tainūṅ rukhāṅ vich takeyā, kaṇkāṅ dī udāsī vich

Kikkarāṅ dī mehak vich

Tūṅ dūr dūr takdī, Kaverī tak

Khohī jāndī thhāṅ, kaṇkāṅ dī patt,

Dhāṇāṅ de jalāye jānde hāse.

Here, every morning, night, noon, and evening is grief-soaked,

Songs arise here,

In the distance, children escorting the grazing cattle herds, cross the water.

I saw you look very sad,

Your flying pallus become my voyagers towards the islands of sentiments.

I saw you in the trees; in the sadness of wheat-sheaves;

In the fragrance of the acacia trees.

You look far into the distance, to where the Kaveri flows

Lands being snatched; the dishonoured wheat-sheaves;

The laughter around burning paddy fields.Footnote32

Jai Ho Sutlej Behen Tumhārī

Līlā Achraj Behen Tumhārī

Hūā Mudit Man Haṭā Khumārī

Jāūn Maiṅ Tum Par Balīhārī

Victory to you, oh Sister Sutlej

Your play is full of wonders

My heart is made happy, and my intoxication abates

For you, I would give my life.Footnote34

Kī puchh de ho hāl fakirāṅ dā;

Sāḍā nadīyoṅ vicchadeyāṅ nīrāṅ dā

Sāḍā hanjh dī joone āiyāṅ dā

Sāḍā dil jaleyāṅ dilgīrāṅ dā!

What is to be asked about the condition of us ascetics;

We are the waters separated from their rivers.

Emerged from a tear,

Our hearts are melancholy, distressed!Footnote35

A trans-river land: Rivers across the 1947 and other national borders

The eco-cartography of Punjab as a trans-river land was most visible during (and after) the crucial watershed of 1947, when rivers were employed by poets to query the bloodstained borders created at Partition. From the natural borders of the Punjabi landscape divided by rivers, after 1947, Punjab’s mighty rivers now found themselves divided across new manmade ones. To capture the trauma of Partition’s violence, Amrita Pritam addressed the eighteenth-century poet, Waris Shah, who wrote the most famous version of the love legend Heer. Instead of its familiar role as the lover’s river, the Chenab was now charged with absorbing the ‘rivers of blood’ flowing through Punjab in 1947:

Ajj bele lashāṅ bichhīāṅ te lahu dī bharī Channāb

Kisse panjāṅ pāṇīāṅ vichch dittī zehr ralā

Te unhāṅ panīāṅ dharat nūṅ dittā pāṇī lā

Iss zarkhez zamīn de lūṅ lūṅ phuṭṭīā zehr

Today, fields are lined with corpses, and blood fills the Chenab,

Someone has mixed poison in the five rivers’ flow.

Their deadly water is, now, irrigating our lands galore,

This fertile land is sprouting, venom from every pore.

Figure 6. Excerpt of a musical feature of Amrita Pritam’s Kaṇakāṅ de Gīt on the Delhi radio station in 1959.

Source: Akashvani XXIV, no. 15 (New Delhi: Publications Division (India), April 12, 1959).

Ho kankāṅ sāvīāṅ

Rondey neiṅ Mahiwāl, rondīāṅ neiṅ Sohṇīāṅ

Rondīāṅ Channavāṅ ajj rondīāṅ Rāvīāṅ

O green fields,

Crying are the Mahiwals and crying are the Sohnis today

As do the waters of the Chanab and the Ravi.

The charge assigned to Punjab’s rivers in these poems written in the immediacy of Partition contrasts with the element of longing and nostalgia they evoke in the following song originally sung by Pakistani singer Sarwar Gulshan and revived in 1982 by popular Indian singer Gurdas Maan. Sections of the song were recently revived in an MTV Coke Studio song performed by Mann and current Punjabi pop sensation Diljit Dosanjh:Footnote37

Rāvī toṅ Channāb Puchhdā, Kī Hāl Hai Sutlej Dā

The Ravi asks the Chenab, How is the Sutlej doing?

Kade kisse Rāvī koḷoṅ, kadde kisse Rāvī koḷoṅ, vakkh nā Channāb hove

Never from any Ravi, never from any Ravi may a Chenab be severed.Footnote38

This trans-river regional identity equally produces a trans-religious regional identity that serves to unite the many Punjabs, especially the two divided by the Indo-Pak border. It is no wonder then that it is the waters of the Ravi river that are chosen as the central witness to a contemporary cross-border love story, as depicted in the theme song of the Indian Punjabi film Lahoriye (2017, dir. Amberdeep Singh). Sung by Neha Bhasin and Amarinder Gill, with lyrics by Harmanjeet, ‘Pānī Rāvī Dā Chaṛh Ke Vekhdā Hai (The Waters of the Ravi Rise and Watch)’ is composed as a festive melody by Jatinder Shah, replete with the familiar background sound of clapping that accompanies wedding songs in Punjab. Though this is a love story, the Ravi (rather than the Chenab) is the more apt choice for the lyricist, given the setting of the film in a cross-border context, with a greater geographical relevance to the protagonists from villages along the Indo-Pak border.Footnote40 Thus, the Ravi’s waters again turn into spectator, recalling the trope of this river being a witness to shifting moral codes in the wake of modernity, as seen in Badrulnisa and Budh Singh’s early twentieth-century recording.

Finally, rivers have equally dominated the experience of migrant and diasporic Punjabis. Parineeta Dandekar has noted how Sikh soldiers fighting for the British in Hong Kong in the mid nineteenth century named small channels in Hong Kong after rivers of their homeland.Footnote41 More recently, the Dubai-based Pakistani singer Sajjad Ali (from Punjab’s Kasur-Patiala gharānā of music) released a single titled ‘Ravi’, an ode to the river of his homeland in Punjab, even though the video is shot at Dubai’s Marina walk:

Je aithoṅ kadī Rāvī laṅgh jāve, hayātī Panj-ābī baṇ jāve

Maiṅ beṛīyāṅṅ hazār toṛ lāṅ, maiṅ pāṇī ’ichoṅ sāh nichoṛ lāṅ.

Je Rāvī vich pāṇī koī naī, te apṇī kahānī koī naī

Je saṅg belīyā koī naī, te kisse nū sunānī koī naī

Ankhāṅ ’ch darīyā ghol ke, maiṅ zakhmāṅ dī thāṅ te roṛ lāṅ.

If the Ravi were to flow near here, my life would become like the Five Waters (Punjabi)

I would break (away from) a thousand chains, into the water I would squeeze my very breath.

If there is no water in the Ravi, then no story is mine (to tell)

No companion with me, and no one to tell these stories to

Dissolving the river within my eyes, I would heal these embedded wounds.Footnote42

Conclusion

This paper has offered a ‘hydropoetics’ of rivers in modern Punjabi cultural identity by seeking to delve into the very language of rivers in Punjab. By tracing this ‘poetic sensitivity toward rivers’, we hope to have highlighted the ‘cultural, social, and spiritual significance of riverscapes’ for Punjab.Footnote44 We asserted that the relatively shorter length of Punjab’s rivers, and the corresponding lack of a community of boat-people, accounts for an absence of a genre of river or boat songs in the lands of central Punjab.Footnote45 However, as we have contended, rivers as metaphors occupy a central place in the Punjabi imagination, given their constitutive etymological significance for the region. The rivers of Punjab have been a key part in the construction of Punjabi identity and self-awareness as a community. More pertinently, in Punjab’s songs and poetry, we find the river often transmuting, transforming itself into longing—as flow, but also as fire (as in Dil’s poems)—for the beloved (whether human, divine or political) and sorrow through tears or ‘hanjū’. All these examples reveal the mutability of the river in the Punjabi cultural and poetic context.

Rivers were additionally employed by writers and cultural producers to symbolise a healing force, and act as agents for peace-building in a divided region, as witnesses to both the love of folk heroes and heroines but also the hatred, violence and bitterness of Partition, and, finally, as participants in the quotidian identities of Punjabis. We have argued that from a Punjabi cultural perspective, it is the two nations—India and Pakistan—that are trans-river, rather than the rivers being transnational. In the process, the evidence here also helps foreground conceptions of regional identity that are alternatives to conventional land-centric models.

More crucially, the examples of the ‘panj darīyā’ discussed in this paper reveal how their multiple connotations overwhelm the common sacral narratives of rivers in other South Asian regions, revealing the ways in which region-centric significations of rivers are more important in Punjabi self-imaginings than pan-Indian Hindu-centric ones. The examples detailed here also point to the ways in which such a trans-river regional identity also produces, and intersects with, a trans-religious regional identity in Punjab, thereby revealing that rivers are particularly well suited to articulations of ‘Punjabiyat’.

Given their liquescence, however, rivers subvert borders and push us beyond the very regional bounds of what is today understood as mainland Punjab too. The notion of the ‘trans-river land’ also pushes us towards exploring, in future research, eco-cartographies of the ‘Greater Punjab’ region during pre-colonial times. This is particularly important since pre-colonial sacred geographies were overwritten by a British colonial cartographic imagination that clearly marked India into linguistically demarcated, apparently self-contained zones. By extension, these older geographies were then made synonymous with linguistically defined states in post-colonial histories, a synonymy to which our essay has also partly subscribed. An attempt to go beyond this synonymy was made by that giant of Punjabi literature, Bhai Vir Singh (1872–1957), who visualised this broader geographical region when he wrote so evocatively of the Icchabal spring in Kashmir (the origin of the Jhelum river). In ‘Chashma Ichhabal’, he personifies the spring as a restless, love-frenzied seeker impatient to reach the beloved:

Sāṅjha hūī parchhāvēṅ chhup gaye

Kyūṅ Ichhābal tūṅ jārī

Naiṅ sarod kar rahī uveṅ hī

Te ṭurno vī nahīṅ hārī….

It is now evening, the shadows too are all hiding

Why then, Ichchabal, do you still flow?

Your waters still twang (musically) like the sarod

They don’t tire of journeying.Footnote46

This paper has also revealed literary, poetic and musical iterations of the rivers through an affective register, with an engagement of the human senses. We noted the emphasis on the river’s ‘flow’ (‘vagdi-e-Ravi’) in multiple proverbs and songs, in poems by Bhai Vir Singh and Kalepani (see below); viewed through the charge of intimacy and desire in Lal Singh Dil’s writings, personification, but also sonic and spiritual presence in Puran Singh; as connected to sorrow, melancholy and the water of tears in Batalvi, Pritam and Pervaiz; as witnesses to and victims of a range of political conjunctures from the declaration of independence (‘Purna Swaraj’) on the banks of the Ravi to blood contaminating the rivers during the tragedy of the Partition (Pritam) and to rivers saddened by the depredations of capitalism (Dil). We also noted regionally-specific ascriptions for each of the rivers: Ravi as the ever-present symbol of flow, and as the one river connecting the two Punjabs in the aftermath of 1947, but, most of all, as the characteristic symbol of Punjabi identity itself (Sajjad Ali) and of the continuous ‘flow’ of tradition into the present (Badrulnisa and Budh Singh). The Sutlej emerged as the source of spiritual, but also social and political, healing (Dil and Nagarjun), while the Chenab stands out as the lover’s river, the site of tragedy (love legends) but also of lovers playfully teasing each other (‘Laṅgh Ājā Pattaṇ Channā Dā Yār’).Footnote48 Finally, the metaphorical river surfaced as a liminal location, especially in the powerful expressions around female sexuality in Pakistani Punjabi film songs by Noor Jehan during the 1970s and 1980s.

The river in Punjab has a malleable but crucial function in articulating everyday cultural and subregional ascriptions, but also understandings of spiritual seeking, love, longing, home and belonging. From the personal to the spiritual, to the cultural and political, this initial survey reveals how singing the river in Punjab offers an important grounding of a regional and ontological identity for composers, singers and listeners across time. In contemporary Punjab, several rivers face the risks of severe pollution, concretisation of flood-plains, and disputes over water-sharing and shortages. In this context, the poem ‘Vagde Pāṇī (Flowing Waters)’ by Diwan Singh Kalepani—sentenced to the jail on the Andaman Islands (Kalapani) for participating in the freedom struggle against British rule and later executed by the Japanese navy during World War II—is pertinent. Here, Kalepani stresses the need for the waters to consistently ‘flow’, flow itself becoming a symbol of life, energy and progress, a metaphor suitable for future research on the connections between ecology, poetry and music in South Asia:

Pāṇī Vagde Hī Rehṇ,

Kī Vagde Saundhe Ne

Khaṛaunde Busde Ne

Ki Pāṇī Vagde Hī Rehṇ.

May the waters keep flowing,

For while flowing they are beautiful

When stagnant they rot,

So, may the waters keep flowing.Footnote49

Acknowledgements

We thank the Leverhulme Trust for funding Radha Kapuria's research on Partition and music that led to this article. We thank Dr. Madan Gopal Singh for sowing the seeds for this paper through his substantial musical and intellectual influence, and to the filmmaker Daljit Ami for sharing valuable inputs, especially his recitations of Lal Singh Dil’s poems. We wish to acknowledge our gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers for their critical reading and detailed feedback, which helped us further clarify and amplify our arguments. We are also grateful to the Special Section co-editor, Dr. Priyanka Basu, for all her hard work and for such a productive exchange of ideas. This article came to its conclusion in a week that witnessed the loss of beloved Squeeky/Simcha, our feline friend who embodied such unbridled joy and unconditional loving in every moment, teaching us to challenge socially-embedded human versus animal binaries. It is dedicated to her indomitable spirit.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. Personal communication with Madan Gopal Singh, March 10, 2021. On the songs written for the Brahmaputra river and its importance in the Assamese cultural landscape, see Arupjyoti Saikia, The Unquiet River: A Biography of the Brahmaputra (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

2. See Farina Mir, ‘Genre and Devotion in Punjabi Popular Narratives: Rethinking Cultural and Religious Syncretism’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 48, no. 3 (July 2006): 727–58. We thank the anonymous reviewer of this essay for pointing this out.

3. To rank some of these rivers of South Asia in terms of their course length, the largest are the Brahmaputra (3,848 km) and the Indus (3,180 km), both rising in Tibet, followed by the Ganga (2,525 km), the Yamuna (1,736 km), the Godavari (1,465 km), the Sutlej (1,450 km), the Narmada (1,312 km), the Chenab (960 km), the Jhelum (725 km), the Ravi (720 km) and the Beas (470 km).

4. John Charles Ryan, ‘Hydropoetics: The Rewor(l)ding of Rivers’, ‘Special Issue: Voicing Rivers’, River Research and Applications 38, no. 3 (2021): 486–93, accessed December 1, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3844.

5. Sunil Amrith, Unruly Waters: How Rains, Rivers, Coasts and Seas Have Shaped Asia’s History (New York: Basic Books, 2018): 23.

6. Sugata Ray and Venugopal Madipatti, ed., Water Histories of South Asia: The Materiality of Liquescence (New Delhi: Routledge, 2019).

7. J.S. Grewal, ‘Historical Geography of Punjab’, Journal of Punjab Studies 11, no. 1 (2004): 2.

8. Patricia Bauer, ‘Indus Waters Treaty’, Encyclopedia Britannica, September 12, 2021, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/event/Indus-Waters-Treaty; see also Haroon Khalid, ‘Divided Rivers of Punjab and Their Legends’, Huffington Post, October 10, 2016, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/divided-rivers-of-punjab-_b_12179016.

9. Anjali Gera Roy, ‘One Land, Many Nations’, Working Paper No. 63, Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics, South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University (October 2011): 2.

10. David Gilmartin, Blood and Water: The Indus River Basin in Modern History (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015): 3, 4, 128. Farina Mir also noted such praise poems for British irrigation engineers in her earlier study on the colonial Punjabi qissā tradition of storytelling: Farina Mir, The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab (Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2010): 85–6.

11. Nasirullah Khan, ‘Songs of the Cholistan Desert (Southwest Punjab)’, in Cultural Expressions of South Punjab, ed. Sajida Haidar Vandal (Germany: UNESCO, 2015): 145–61.

12. We thank the anonymous reviewer for reminding us of this proverb.

13. See Sidhu Moosewala, ‘SYL’, YouTube video, 4:09, uploaded posthumously June 23, 2022, accessed July 16, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pcT44dbu7es.

14. Quoted in and based on the translation by Fayyaz Baqir, ‘Female Agency and Representation in Punjabi Folklore: Reflections on a Folk Song of Rachna Valley’, Journal of Sikh and Punjab Studies 24, nos. 1–2, (2017): 54. Given this is a saying from west Punjab in Pakistan, the Indus has replaced the Beas (which flows in the eastern Punjab plains).

15. A slightly different and longer version of the song is available to view in the transliteration by Suman Kashyap at ‘Folk Geet’, Apna, accessed December 1, 2021, https://apnaorg.com/poetry/romanenglish/loke/geet5.htm.

16. Folk singer Reshma’s rendition can be found on YouTube, accessed September 29, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=75WDiJKAT2I. See also, among others, the version sung by Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his troupe, in particular their 1983 performance for Oriental Star Agencies, Birmingham: Oriental Star Agencies, ‘Shahbaz Qalandar (Lal Meri Pat Rakhio)—Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan—OSA Official HD Video’, YouTube video, 18:22, April 16, 2016, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxjKw7HZQEI.

17. For the version of the mirāsans at Patiala, see Prasar Bharati Lok Sampada, ‘Heth Vage Daria | Wattna Malna I Vivaah I Patiala I Punjab’, YouTube video, 7:39, March 25, 2020, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1oM1ceWseYM.

18. The recording is available to listen here: British Library, ‘Young India Record Label Collection’, accessed December 1, 2021, https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Young-India-record-label-collection/025M-CEAP190X9X01-043ZV0. The English title of the Punjabi song is incorrectly noted as ‘Bagdi Aye Ravi’ instead of ‘Vagdi Aye Ravi’.

19. On the māhīyā, see Gibb Schreffler, ‘Western Punjabi Song Forms: Māhīā and ḍholā’, in ‘Music and Musicians of Punjab’, Journal of Punjab Studies 18, nos. 1–2 (2011): 75–96. Kausar Parveen’s original sung version from 1956 is available to view on YouTube, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0xSQ8iIkes; for Asad Amanat Ali Khan’s version, see Moonlight Moods, ‘Vagdi-e-Raavi by Asad Amanat Ali Khan’, YouTube video, 5:01, June 9, 2017, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmJTb-XWdmM.

20. For Ataullah Khan Esakhelvi’s use of the term in a folk song, see M. Asif, ‘Attaullah Khan—Wey Bol Sanwal, Wagdi Aye Ravi Wich, Attaullah Khan Old PTV Songs’, YouTube video, 5:00, April 16, 2013, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lwKEjk4r41E; Bushra Siddiqui and Arif Lohar’s song is available at Arif Lohar, ‘Wagdi Ae Raavi (Mahiya)’, YouTube video, 14:51, October 11, 2014, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7S13E3dEHI. See the video of Sartaaj’s performance at Moviebox Record Label, ‘Vagdi Si Raavi | Official Video | Satinder Sartaaj Live’, YouTube video, 2:15, August 27, 2012, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B7bkXrS7vtc; https://music.apple.com/gb/album/sartaaj-live/499335663.

21. See ‘Free-Flowing Cartographies’, in Imperialism and Sikh Migration: The Komagata Maru Incident, ed. Anjali Gera Roy (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018): chap. 1.

22. The video for the song is available to view at Famous Video, ‘Wagdi Aye Ravi Wich Udan—Noor Jehan—Pakistani Film Faqeeria’, YouTube video, 6:00, December 21, 2018, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pYxmLGmZ28.

23. Prakash Tandon, Punjabi Century 1857–1947 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968): 71.

24. Saleem Iqbal composed the music for this song.

25. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage (London: Routledge, 2004 [1960]): 65–67. We thank Marged Trumper for the suggestion to read van Gennep.

26. Faiza Hussain and Sarwet Rasul, ‘Sarcasm, Humour and Exaggeration in Pakistani Punjabi Wedding Songs: Implicit Gendered Identities’, Pakistan Journal of Women’s Studies: Alam-e-Niswan 23, no. 2 (2016): 35, 41, translation in original.

27. Kaur’s rendition is available at: Murad Khan, VintageSense, ‘Surinder Kaur Lang Aaja Patan Chana Da Yar Punjabi Folk Song’, DailyMotion video, 3:07, 2014, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2frv6t. A transliteration of the lyrics by Suman Kashyap is available at Apna, accessed December 1, 2021, https://apnaorg.com/poetry/romanenglish/loke/index.htm.

28. The poems originally featured in Puran Singh’s collection, Khulley Maidan (1923), are available in both Gurmukhi and Shahmukhi at Punjabi-Kavita, ‘Khulhe Maidan Puran Singh’, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.punjabi-kavita.com/KhulheMaidanPuranSingh.php#KhulheMaidan024, translation ours, adapted in part from Surjit Singh Dulai, ‘Critical Ecstasy: The Modern Poetry of Puran Singh’, in Sikh Art and Literature, ed. Kerry Brown (London: Routledge, 1999): 155–172, 167.

29. The recording of the song is available at: British Library, ‘Young India Record Label Collection’, accessed December 1, 2021, https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Young-India-record-label-collection/025M-CEAP190X9X01-051ZV0. The English title is incorrectly noted on the British Library catalogue as ‘Sona Deshanu Desh Punjab’ instead of ‘Sona Desan Vichon Des Punjab’.

30. Ipsita Chakravarty, ‘Saffron Shadows: Has the Covert Presence of Hindutva Groups Helped the BJP in Ladakh?’, Scroll.in, May 5, 2019, accessed July 15, 2022, https://scroll.in/article/922333/saffron-shadows-has-the-covert-presence-of-hindutva-groups-helped-the-bjp-in-ladakh. Further, the man who assassinated Mahatma Gandhi, Nathuram Godse, instructed his family to immerse his ashes in the Indus river only when the RSS dream of ‘Akhand Bharat’, or undivided India, was fulfilled; consequently, his ashes are yet to be immersed: Amrita Dutta, ‘Retracing Nathuram Godse’s Journey’, The Indian Express, January 31, 2015, accessed December 1, 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/retracing-nathuram-godses-journey-2/.

31. Translation ours, with some borrowings from Nirupama Dutt, trans., Poet of the Revolution: The Memoirs and Poems of Lal Singh Dil (New Delhi: Penguin Viking, 2012): 294. We thank Daljit Ami for his help with pronunciation and for locating the original in Punjabi.

32. Translation ours, with some borrowings from Dutt, Poet of the Revolution, 264–65.

33. Rajesh Sharma, ‘Lal Singh Dil and the Poetics of Disjunction: The Poet as a Political Cartographer’, Economic & Political Weekly 49, no. 6 (2014): 64–71; 66.

34. Quoted from the school textbook, Vasant Bhaag 2: Kaksha 7 ke Liye Hindi ki Paathyapustak (New Delhi: NCERT, 2007): 14, translation ours.

35. Our translation is based on the one at Apna, ‘Suman’, accessed December 1, 2021, https://apnaorg.com/poetry/suman/15.html.

36. The video for this song is available at TalatAfrozeToronto, ‘Khawaja Parvaiz Wagday Nay Akhiyaan Cho Nazir Ali Dilaan Day Sauday 1969.flv’, YouTube video, 3:03, May 21, 2021, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhC5d9cpDkY.

37. Prabhneet Kaur, ‘Gurdas Maan and Dosanjh Ask the Same Question, “Ki Banu Duniya Da”’, The Hindustan Times, August 21, 2015, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.hindustantimes.com/chandigarh/gurdas-maan-and-dosanjh-ask-the-same-question-ki-banu-duniya-da/story-8NBl3tc1C0PphsATgLCqyN.html.

38. Coke Studio India, ‘“Ki Banu Duniya Da”—Gurdas Maan, feat. Diljit Dosanjh and Jatinder Shah—Coke Studio @ MTV Season 4’, YouTube video, 8:02 (3:37–04:15 and 5:00–5:19), August 15, 2015, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pjQyBF2gwjQ; T-Series, ‘“Apna Punjab Hove” (Full Song) | Gurdas Maan | Yaar Mera Pyaar’, YouTube video, 4:18, November 23, 2011, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cHLSWmVnTE.

39. Ryan, ‘Hydropoetics’, 3.

40. The Chenab does not flow through the present-day state of Indian Punjab, only through Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir. Further, the Chenab is not well suited in this context, given the love story ends successfully, and this river is usually invoked in the context of Punjab’s tragic love legends.

41. Parineeta Dandekar, ‘We Are Rivers: South Asia’s Rivers in Song & Story’, International Rivers, February 13, 2018, accessed December 1, 2021, https://archive.internationalrivers.org/blogs/433/we-are-rivers-south-asia-s-rivers-in-song-story.

42. Sajjad Ali, ‘Sajjad Ali – Ravi (Official Video)’, YouTube video, 3:49, November 26, 2019, accessed December 1, 2021, https://youtu.be/rBk5EKHggKo.

43. Shah Meer Baloch, ‘“We Will Be Homeless”: Lahore Farmers Accuse “Mafia” of Land Grab for New City’, The Guardian, November 2, 2021, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/nov/02/we-will-be-homeless-lahore-farmers-accuse-mafia-of-land-grab-for-new-city. Ironically, one of the biggest investments in the project comes from Dubai, the city of Sajjad Ali’s residence: ‘Dubai Company to Invest in Ravi Riverfront Project’, Dawn, November 29, 2021, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1660801.

44. Ryan, ‘Hydropoetics’, 1.

45. The stray reference to the boatman or ‘mallāh’ in some Punjabi Sufi songs, like the following verse from the sixteenth-century poet, Shah Hussain, does not falsify this observation: see ‘Nadīyoṅ Pār Rānjhaṇ Dā Ṭhāṇā/Kītay Qol Zaroorī Jāṇā/Mintāṅ Karrāṅ Mallāh De Nāl (Ranjha’s dwelling is across the river, I must go, having given my word/I shall beseech the boatman)’, performed by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his troupe: see Oriental Star Agencies, ‘Man Atkeya Beparwah De Naal | Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan | complete full version | OSA Worldwide’, YouTube video, 14:34, January 3, 2019, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lmv_WI0aLQE.

46. Translation adapted from Rajinder Kaur Bali, ‘Bhai Vir Singh and the Call of the Valley’, The Tribune, Chandigarh, December 5, 2013, accessed December 1, 2021, https://www.tribuneindia.com/2013/20131205/edit.htm#6, published as part of the compendium, Matak Hulare (Amritsar: Khalsa Samachar, 1952), accessed September 29, 2022, http://www.panjabdigilib.org/webuser/searches/displayPage.jsp?ID=8855&page=1&CategoryID=1&Searched=.

47. See Frances M. Saw, A Missionary Cantata: The Rani’s Sacrifice, A Legend of Chamba, Retold in Verse with Songs Adapted to Indian Melodies (London: Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, 1912).

48. The Jhelum and Beas occur somewhat less frequently in popular and folkloric ideas about Punjab’s rivers than the other three.

49. Diwan Singh Kalepani, Vagde Pani (Lahore: Punjabi Piyare, 1938), English translation ours.

50. Open access image sourced from Wikipedia, accessed September 2, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Punjab_map_(topographic).png

51. Iwona Jurkiewicz-Gotch, ‘Conservation and Storage of the Panorama of Lahore’, Collection Care Blog, October 8, 2019, accessed December 1, 2021, https://blogs.bl.uk/collectioncare/2019/10/conservation-and-storage-of-the-panorama-of-lahore-.html.