Abstract

There has been no dearth of Mughal women in positions of immense power, but their histories have been limited by a shortage of credible, primary sources, and their gendered and colonial readings. This paper addresses the gap thus created, by examining the inscriptions of Serai Nur, a caravanserai constructed under the matronage of Empress Nur Jahan in Punjab. This case study leads an inquiry into the expressive possibilities of architectural matronage, and the potential for structures thus erected to be considered as alternative primary sources where women have been agents of their own representations. In contrast to positivist approaches traditionally employed to read foundational inscriptions, this paper contextualises epigraphy within its wider visual environment instead to recognise performative and phenomenological intents, and traces an interpretive path backwards from individual design decisions manifest in the built fabric to their maker’s creative ambition in order to better understand her mind and motivations.

1. Introduction

In varying degrees of recognition, conservation and dilapidation, Mughal history continues to be monumental in the contemporary cultural landscapes of subcontinental South Asia. However, the majority of academic interest in these structures is focussed on urban citadels and tombs erected by Mughal emperors, while civic structures, buildings in the hinterlands, and the architectural patronage of Mughal women remain areas rarely explored. Caravanserais, or rest stations along travel routes, fall into all three understudied categories of architecture. These structures have the potential to offer us important glimpses into the expressive capacities of Mughal women, and caravanserais matronised by women range from Zinat-un-Nissa’s 14 serais between Awadh and Bengal in the east to Jahan Ara’s Serai Jahanabad in Gor Khatri in the north-west and Rehmat-un-Nissa’s Serais Baijipura and Fardapur in the south-west, with many more in between along all the primary corridors of travel. Since architecture was the most expensive form of p/matronage among the arts, and caravanserais were the largest of Islamic typologies, Mughal women’s involvement with such construction evidences their enormous wealth and executive powers. Because caravanserais represent a charitable and commercial architectural typology dedicated to the well-being of travellers and merchants on the highways of the empire, their presence also suggests Mughal women’s active interest in governance and participation in travel and trade.

Details regarding such construction activities by Mughal matrons, however, are not easily accessible. With the exception of Gulbadan Begum’s biographical work, Jahan Ara’s Sufi treatises, and some poetry attributed to Nur Jahan and Zinat-un-Nissa, the majority of which exist in fragments and have not been completely translated and published, unmediated and reliable primary material from women is scarce. In compliance with contemporary codes of propriety, references to Mughal women in courtly chronicles too are sparse and oblique, and have been further obfuscated by modern historians with androcentric, colonial and, more recently, fundamentalist religio-political agendas.Footnote1

It is in this context that it is hypothesised that the body of architecture matronised by Mughal women has the potential to be an alternative corpora of primary information interpreted from creations where women have been agents of their own representation. It is argued that not only do structures matronised by women communicate directly with their users through the semi-official public records of their epigraphic content, but also expand in meaning when read qualitatively and with cognisance of their architectural environment. An attempt to demonstrate and assess this follows in the subsequent sections with the analysis of two foundational inscriptions of Serai Nur,Footnote2 a caravanserai constructed between Agra and Lahore by Empress Nur Jahan, consort to the Mughal emperor, Jahangir.

2. Reading Serai Nur

Mughal caravanserais were buildings designed to enable travel. They were located along all major highways of the empire for a caravan at the end of its daily journey, providing its people and animals with security and basic board and lodging facilities for the night. Archetypally, they were simple, utilitarian structures, near identical in their layouts, and often constructed and operated as religiously motivated and imperially encouraged acts of charity. Typically, as can be seen in the plan of Nur Serai (), these buildings were quadrangular courtyard structures, guarded by two facing gateways and an otherwise uninterrupted fortification wall with bastions at four corners. The courtyards within were circumscribed by uniformly sized cells that expanded only within the bastions and imperial chambers, of which the latter were usually accommodated within blind gateways dividing those arms of the quadrangle not equipped with actual portals. While travellers were meant to lodge in the cells, the courtyard was primarily intended for pack animals and vehicles of transport, and were equipped with wells. Almost invariably, the courtyard housed a small, three-bayed mosque, and rarely, such as in the case of Nur Serai, could also have possessed a hammam (a bath). Although the microcosms of caravanserais were responsible for reducing the immensity of thousands of kilometres of road networks into practicable daily sections, it is perhaps this same quotidian nature that resulted in them being encountered only remotely in Mughal chronicles.

Figure 1. Plan of Nur Serai, drawn on an earlier plan by the same author [1: Lahore Darwaza; 2: Delhi Darwaza; 3: Imperial chambers; 4: Gateway to the garden (conjectured); 5: Corner bastions; 6: Cells; 7: Wells; 8: Courtyard mosque; 9: Hammam; 10: Courtyard; Drawing not to scale; Un-rendered sections conjectural].

Source: Parshati Dutta, ‘Caravanserais and Khans: The Architecture and Culture of Land Transport in Mughal India’, (unpublished M. Arch Thesis, CEPT University, 2015).

![Figure 1. Plan of Nur Serai, drawn on an earlier plan by the same author [1: Lahore Darwaza; 2: Delhi Darwaza; 3: Imperial chambers; 4: Gateway to the garden (conjectured); 5: Corner bastions; 6: Cells; 7: Wells; 8: Courtyard mosque; 9: Hammam; 10: Courtyard; Drawing not to scale; Un-rendered sections conjectural].Source: Parshati Dutta, ‘Caravanserais and Khans: The Architecture and Culture of Land Transport in Mughal India’, (unpublished M. Arch Thesis, CEPT University, 2015).](/cms/asset/95cb3ed7-eba3-4f9f-a3fc-3ae292480e80/csas_a_2362055_f0001_c.jpg)

However, caravanserais were recorded extensively by foreign travellers such as Jourdain, Mundy, and Thevenot and Careri,Footnote3 and much appreciated, as evidenced by Roe’s declaration of the road between Agra and Lahore as ‘one of the great works and wonders of the world’.Footnote4 Despite the caravanserais’ significance as enablers of mobility and connectivity in the Mughal world, they have elicited little academic attention.Footnote5 Given this limited engagement, the extensive involvement of imperial Mughal women in the construction of this typology too has been overlooked,Footnote6 motivating the selection of a sample from within this under-researched typology for the purpose of this paper.Footnote7

2.1. Jahangir’s interest in the improvement of road networks

The empire that Jahangir inherited from Akbar included all of the northern Indian subcontinent. With the exception of minor conflicts along the borders with the Safavids and some Deccani royals, it appears to have been at the peak of prosperity and stability. The imagination of this vast expanse—from Chittagong in the east to Kandahar in the west—as a consolidated empire, and the pacification of its people through good administration, relied heavily on the efficiency of Mughal road networks, not only on the military and political fronts, but also on commercial and cultural grounds. Jahangir’s cognisance of this can be evidenced by the Twelve Decrees that he ordered to be observed across the realm soon after his accession, between 1014 AH (1605 CE) and 1016 AH (1607 CE),Footnote8 the first three of which were aimed directly at improving passage through the empire.Footnote9 The first decree forbade the collection of several forms of taxation that the emperor felt were being imposed by provincial governors for their own benefits, while the third prohibited the opening of merchants’ packs along the roads without their consent.Footnote10 The second decree dealt directly with the construction of caravanserais and stated:

On roads where there were thieves and highway bandits and where the roads were somewhat distant from habitation, the jagirdars (holders of land grants) of that region were to construct a caravanserai and mosque and dig a well to encourage habitation in the caravanserai. If such places were near royal demesnes, the superintendent of that place was to carry out these measures.Footnote11

Two rows of trees had been planted to form an avenue from Agra to the river at Attock, and from Agra to Bengal as well. Now it was ordered that a post be set up every kos [a unit of length between 3 and 4 kilometres in Jahangir’s time] from Agra to Lahore to show the distance and a well dug at every third post so that wayfarers could travel easily and comfortably and not suffer from thirst or the heat of the sun.Footnote12

2.2. Nur Jahan’s intervention

This caravanserai is the first epigraphically confirmed construction in a long list of structures ultimately matronised by Empress Nur Jahan, of which the tomb of Itimad al-Daulah is perhaps best known and recognised as a tomb foreshadowing the Taj. Radical, monumental and lavishly ornamented like them all, in its contemporary world though, Serai Nur too would have been widely appreciated, especially as its earliest records come from Emperor Jahangir himself. Jahangir documents halting there with his entourage thrice between 1030 AH (1621 CE) and 1032 AH (1622 CE), and describes the serai and its garden as ‘fine’ and ‘regal’.Footnote13 From his reportage of an elaborate entertainment organised for him by Nur Jahan to commemorate the serai’s completion, it appears that the empress too was present on site at least on one of these occasions.Footnote14

While it is well established that the zenana moved with the emperor as a standard section of the imperial caravan, the manner in which women inhabited caravanserais has been less clear. In light of Nur Jahan’s matronage of and presence at the Nur Serai though, certain atypical features of the structure can be regarded as interventions made by and for women. A detailed formal analysis of all individual components of the serai is beyond the scope of this paper, but the mosque and imperial chambers in particular can be highlighted briefly. The scale of fenestrations on the upper, more secure level of the imperial chambers that were likely originally enveloped with jaalis (latticed screens), and the intricate brickwork lattices screening the side bays of the courtyard mosque, are both features that are unusual, if not unique, in relation to other serais from the region and period. In both areas, this feature results in the creation of spatially and visually segregated spaces within the serai, while also enabling unidirectional viewing of the courtyard from therein, likely for the use of women. Within Findly’s identification of Nur Jahan’s matronage of gardens and serais at large as a process of incentivising women’s travel and encouraging their participation in a more sensual lifestyle,Footnote15 these minimal yet critical deviations from standard architectural practices reinforce the same intent of the matron at a building level, as they gender and charter for women some prime spaces of residence and prayer within a traditionally public and male-dominated typology.

The recreational purposes of the empress and other female users were likely served by a garden attached to Nur Serai abutting its courtyard to the north, which has now been engulfed completely by urban sprawl. The architectural integrity of most of the serai’s cells, its hammam and the Delhi Darwaza have also been compromised by dilapidation and modifications. Thus, for the few architectural historians who have expressed enthusiasm regarding the serai in recent times, their assessments of the structure appear to be based primarily on the aesthetic appeal of the serai’s Lahore Darwaza (), more specifically its dense and rich red sandstone relief.Footnote16 One of the foundational inscriptions of the serai can still be seen in situ on this gateway, and while the other inscription is missing from the Delhi Darwaza, fortunately for the purposes of this study, its copy was discovered with a local villager by Cunningham in the 1870s, duly recorded, translated and published.Footnote17 In these two texts, Nur Jahan’s involvement is implicit given her well-documented matronage of the serai, known proficiency in Persian poetry,Footnote18 and the absence of any other composers’ names.

2.3. Epigraphic content and approach

On the Lahore Darwaza, a Persian inscription states in the suspended Nastaliq script:

Ba-daur adl Jahangir Shah, Akbar Shah

kih asman-o-zamin misl-au nadarad yad

binai Nur Sara shud ba-khitah-Phalor

ba-hukam Nur Jahan Begam farishtah-nihad

barai sal binayash sukhan ware khush guft

ke shud za Nur Jahan Begam ain Sara abad 1028

chu, shud tamam khirad guft bahar tarikhash

ba-shud za Nur Jahan Begam ain Sara Abad 1030 This was translated by Cunningham to:

During the just rule of Jahangir Shah, son of Akbar Shah,

whose like neither heaven nor earth remembers,

The Nur Sarai was founded in the district of Phalor

By command of the angel-like Nur Jahan Begam.

The date of its foundation the poet happily discovered

‘This Sarai was founded by Nur Jahan Begam’ (1028)

The date of its completion wisdom found in the words

‘This Sarai was erected by Nur Jahan Begam’ (1030).Footnote19

According to Cunningham, the inscription on the Delhi Darwaza, also in Persian, was:

Shahe Jahan badaur Jahangir badshah

Shanhinshahe (sic) zamin-o-zaman saye Khuda

Mamur kard baske Jahan ra ba-adl-o-dad

ta-asman rasid bina bar sare bina

Nur-e-Jahan ke hamdam-o-humsaz khas aust

jarmud ain sarai wasi e sipahar sa

Chun ain binai kher ba rue zamin nihad

bada binai umrash jawed bar baka

tarikh ain chun gasht murattib ba-guft akal

abad shud za Nur Jahan Begam ain Sarai He translated this as:

During the reign of Jahangir Badshah, lord of the Universe,

king of kings of this world and his time, the shadow of God.

The fame of whose goodness and justice overspread the earth

Until it reached even the highest heavens above.

His wife and trusted companion, Nur Jahan,

commanded the erection of this Sarai, wide as the heavens.

When this fortunate building rose upon the face of the earth,

May its walls last for ever and ever!

The date of its foundation wisdom found in the words

‘This Sarai was founded by Nur Jahan Begam’. Footnote20

Cunningham’s translations have been used since by BegleyFootnote21 and Parihar,Footnote22 who appear to have shared largely positivist concerns regarding the inscriptions’ factual content alone, and have approached them as disembodied words in isolation. This paper therefore attempts an alternative reading of the inscription within the context of the gateways’ wider architectural environment, based on Antony Eastmond’s theory emphasising the need for viewing inscriptions rather than reading them, in order to better comprehend their non-verbal elements, critical to these texts in the same way that kinesic messages such as gesture, posture, facial expression, and movement are key in understanding spoken words.Footnote23 Thus, the inscriptions are understood not only literally, but also in terms of their situation, scale, lettering, visibility, choice of language and script, legibility, codification, organisation, iconographic supplements, intended audience, and their anticipated performance of viewing.

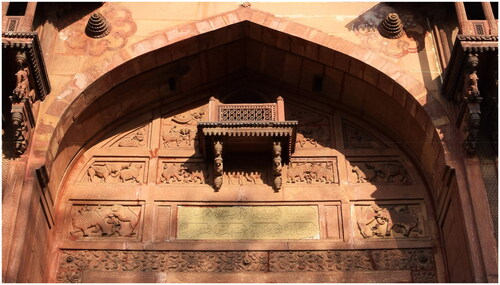

2.4. Visibility and visual field

On the Lahore Darwaza, where the inscription is yet extant, it can be seen to have been chiselled onto a stone tablet affixed centrally and immediately above the serai’s entrance. This location in itself is a departure from the common epigraphic habit of positioning inscriptions on the face of the pishtaq (a high entrance portal), either framing the arch or sitting immediately beneath the battlement for shorter texts (), and in both cases, farther from the observer and thus often incomprehensible to the naked eye, suggesting a greater concern for actual legibility in the case of Nur Serai. Additionally, while this location is already one of higher visibility, the plaque is rendered even more prominent by the choice of materials, as the tablet’s creamy colouring is in high contrast with the red and rough texture of the sandstone cladding the gateway otherwise. The sharply incised lettering of the text uses the value of contrast to an even greater advantage, as each letter and diacritic casts its own dark shadow against the pale panel, further enabling legibility. Finally, each couplet is broken and organised into four cartouches, one per hemistich, with all eight then being laid out onto a 2×4 grid, emphasising the composition’s rhyme and metre. Even as the density of text varies within the cartouches, the lettering being cramped with information towards the end of most hemistiches, their identical sizing and perfectly symmetrical balance echoes the ornamental rigour of its visual environment, suggesting that while content and comprehension of the text were certainly vital, the beauty of calligraphy and its contribution to that of the gateway overall was not considered negotiable.

Figures 3a and b. Epigraphic locations on the gateways of two other Mughal caravanserais from Punjab—Amanat Khan (left) with its running band of calligraphy framing the arch and Lashkar Khan (right) with smaller panels affixed closer to battlements.

Source: Author

The tablet is situated within the arched opening, above the actual portal and below a balconette (), in a captivating field of red sandstone relief divided into four horizontal bands among which the inscription appears on the third from the top (). The band below the tablet, designed as an intricate vegetal scroll of intertwining vines on which real and fantastical buds blossom and birds perch, extends in both directions to run around the portal and is likely the most sophisticated in terms of its sculptural quality. This accomplishment is perhaps explained by the fact that, as Chandra has pointed out, they were a part of a repertoire of motifs frequently used by Islamic monarchs as symbols of the paradise that they imagined their realms to be,Footnote24 and had already been deployed similarly in some earlier monuments in Sikandra. However, it is the three zoomorphic panels above the text that are unique, and unlike the vegetal scroll that remains limited to a decorative design in its use as a filling and framing device, they operate as ornaments with greater bearings on the reading of the inscription. Before considering this impact, it is important to emphasise that the claim of deliberation on the part of Nur Jahan in the choice of these zoomorphic panels is supported by their uniqueness, and Grabar’s ‘theory of intermediaries in art’, where the artisans’ creation of such departures from established patterns has been argued to be reasonable proof of a p(/m)atron’s conscious choice, if not explicitly made, at least cognisant of its import.Footnote25

Figure 4. Foundational inscription on the Lahore Darwaza within its visual environment.

Source: Author

Prior to the construction of Nur Serai, animals in Mughal architecture appear to have largely been restricted to the use of elephants, as colossal sculptures guarding the gates of Fatehpur Sikri and Agra, on inlays and as brackets in the imperial fort palaces of Agra and Lahore, and as carved pairs concealed in the panels of Akbar’s tomb and its adjacent Kanch Mahal in Sikandra. The later profusion of animals found in the tile mosaic panels installed on the walls of the Lahore Fort circa 1030 AH (1620 CE) under the order of Emperor Jahangir are generally attributed to his well-documented interest in nature,Footnote26 but in their reiteration of the twin animal motifs—horses caught in games of chawgan (a Persianate predecessor of polo), or elephants and camels engaged in combat—they may well have been in conversation with the Lahore Darwaza of Nur Serai, where they were contemporaneously deployed. Additionally, the zoomorphic panels in Nur Serai depict hunting scenes in the lowest tier, as well as some mythological entities such as Mughal ruq-gajasimha hybridsFootnote27 (a winged animal with a lion’s body and elephant’s head) pursuing rhinoceroses and bovines in the middle, and several winged angels playing musical instruments on top.

Overall, the relief is crisp albeit low, with the exception of certain areas such as the lions’ and their hunters’ heads, the bovines, and the weapons held by the riders of fighting elephants, which break and protrude from their frames. Here, the figures appear nearly disengaged from the ground, and add a dynamic dimension to the composition, heightening its dramatic effect. Further, while the composition is in its entirety harmoniously balanced, and reinforced by an added layer of symmetry in the mirroring of animals within the majority of the panels, the fact that each of these animals except the lionesses were carved to be pronouncedly male and engaged in fights, chases or hunts, ultimately creates a tense atmosphere and evokes the themes of power and dominance.

While such depictions of chawgan, hunts and fights have been construed as references to imperial amusements,Footnote28 it is unlikely that the serai’s matron had intended for them to be understood as such, based not only on visual analysis of their stances and sculpting, but also because being as engaged with statecraft as she was, Nur Jahan would have been well aware of the Ain-I Akbari’s explicit and repeated warning against such superficial associations. According to the Ain, the game of chawgan was not only devised as a means to improve the riding skills of the players and agility and obedience of their horses, but was also a bonding exercise, a lesson in promptitude with decisions, and ultimately, the test of a man’s concealed talents and value.Footnote29 Likewise, animal fights appear to have had an underlying intent of gathering large numbers of people across social classes with the promise of amusement to actually spread imperial propaganda instead,Footnote30 while hunts were pretexts for the emperor to acquire knowledge regarding the condition of his people, armies, lands, and the state of governance.Footnote31 Thus, like Akbar had used this array of majestic beasts as a political apparatus for the performance of kingship, by choosing them to frame her inscription, Nur Jahan too was likely drawing upon an established symbolism to reinforce her own sovereignty.

2.5. Legibility, audience and the performance of reading

Returning to the content of the texts, it is important to note Nur Jahan’s choice to use Persian not just as the primary, but as the only language for the inscriptions. The lack of any translations might indicate an expectation of literacy in Persian from contemporary audiences and partial exclusion of those without, and combined, an assertion of the dominance of the Persian language, and by extension, Persianate culture and politics in the Mughal court that the matron herself embodied on account of her natal house. It can also be suggestive of the fact that Nur Jahan may not have been familiar with alternative regional languages, and by choosing to not include any translations, retained total control of the information communicated.Footnote32 In either case, the text succeeds in conveying a wide range of biographical information about Nur Jahan in these texts, even as they are presented on the surface as foundational inscriptions for the serai. As a semi-official public document, this presentation not only provides credibility to the allusions of Nur Jahan’s ability and authority, but as one set in stone on a monumental gateway, magnifies its impact and gives the information more permanence than would have been achieved if conveyed on paper or any other material.

The information provided by the epigraphy itself is concise, beginning without invoking God or making any religious proclamation as was customary, and moving directly instead into the facts regarding the reign and the ruler, the matron, the structure, and the dates of construction. However, the text on the Delhi Darwaza is longer than that on the Lahore Darwaza by a couplet and uses this to eulogise Jahangir. Further, while the Lahore Darwaza inscription dedicates two couplets to the serai’s construction dates—foundation and completion—the other, likely having been constructed earlier, limits itself to foundation only, using the spare couplet to then pray for the serai’s perpetuity. A marked difference in attitude is thus achieved between the two inscriptions, where the Delhi Darwaza text appears intent on portraying Nur Jahan with a greater sense of humility. This comparatively more self-effacing tone would also have been enhanced by the Delhi Darwaza’s architectural appearance, as it appears to have been less momentous than the Lahore Darwaza, not only from the scale of its archaeological remains, but also in the fact that its construction concluded two years earlier and was of a quality that allowed for it to decay centuries sooner (, see in relation to ).Footnote33 The dissimilarities between the gateways are also experiential, as upon entering through the Lahore Darwaza a traveller would have been faced with an impressive expanse of the serai’s vast courtyard, whereas even though the space remained constant, its impact would have been lesser upon entrance through the Delhi Darwaza, as the sweep of visual field was interrupted by the masjid and hammam ( and ).

Figure 5. Delhi Darwaza of Nur Serai in its current state with courtyard and Lahore Darwaza visible beyond.

Source: Diya Handa

Figure 6. The courtyard of Nur Serai with Delhi Darwaza visible on the right and courtyard mosque on the left.

Source: Author

The disposition of the textual and architectural attributes of the gateways thus combine to create a distinct hierarchy of spaces, organised likely with awareness of their joint performative value, where an apparently factual foundational inscription uses its potential to condition the perspectives of its viewers. Thus, the Lahore Darwaza that Persian and Central Asian caravans would have first encountered appears to have been designed to be more impressive, whereas for caravans from the Mughal empire entering the serai through the Delhi Darwaza, a more reserved vocabulary was employed. Arguably, travellers from the Mughal mainland would already have been acquainted with Nur Jahan’s political clout, making grandiose proclamation redundant for this audience. Moreover, if the contemporary society did indeed harbour resentments towards Nur Jahan and her family as usurpers of power and harbingers of disorder in the empire like Shah Jahan’s historians later claimed,Footnote34 then, with its relative modesty, the Delhi Darwaza and its inscription may also have been articulated as an appeasement.

However, Nur Jahan still manages to take accountability for the construction of the serai five times over in the two texts, and the Persian hemistich for ‘This Sarai was erected/founded by Nur Jahan Begam’ was repeated, nearly unchanged, thrice over as a refrain. In these sections, the text also offered to those acquainted with the system of abjad (the numerical equation of letters) a second layer of information regarding the dates of foundation and completion of the serai as 1028 and 1030 AH, respectively, approximately analogous to 1618 and 1620 CE. The years denoted in the text are of the Hijri calendar, and not of the emperor’s regnal year as was often the practice, evidencing another choice likely motivated by a wish to pre-empt any difficulty in comprehension among travellers from the wider Islamic world who appear to be the serai’s primary audience.

The act of codification in itself can be understood on two levels. On the first, the information conveyed by the chronograms would have been made more potent by the fact that they would be accessible only to those initiated to the cipher, and on the second, by requiring greater concentration and longer engagement with the text in order to decode it, its relationship with the viewer would have been strengthened. Memorialisation may have been central to most inscriptions, but the Nur Serai inscriptions, versification, repetition and codification ensure that one specific hemistich—‘This Sarai was founded/erected by Nur Jahan Begam’—is nominated as the most memorable phrase, presumably because it was deemed the most crucial piece information by the matron for communication.

Otherwise, however, writing about one’s own virtues having been considered unseemly at the time, with the emperor himself holding back from providing details of his accomplishments,Footnote35 the information communicated by the inscriptions about Nur Jahan is contingent on the reader’s attention to minutiae and awareness of contemporary socio-political climates.

2.6. Representation and memorialisation

The dates in themselves offer a plethora of meaning, and the enumeration of both foundation and completion dates together, evidencing a construction period of only two years, appears to convey pride in the speed of building. A common feature in architectural enterprises of premodern Islamic women elsewhere has been found to be long, multi-phased periods of construction, symptomatic of irregular cash flows and mismanaged projects,Footnote36 but this was clearly not applicable to Nur Jahan, whose immense wealth and an efficient network stretching from the itinerant imperial camp to the serai’s site were both demonstrated by its pace of construction.

The dates also operate as markers of the matron’s steep political rise. While Nur Jahan had been awarded the honorific of Nur Mahal (light of the palace) upon her marriage with the emperor,Footnote37 in 1025 AH (1616 CE), three years prior to the foundation of the serai, her rank was raised further to Nur Jahan (light of the world).Footnote38 Given that Emperor Jahangir himself was styled Nur al-din Jahangir (both master of the world and light of religion) in a continuation of Akbar’s practice of mysticism in monarchy, it is the personification of celestial light that placed the couple on a shared plane above mere mortals, while with the parallels created between their names, their identities were fused. This, combined with the use of the title Padshah Begum (approximately equivalent to ‘empress’) in coinage and signatures beginning around the same time and demonstrating the emperor’s approval in Nur Jahan’s role as co-sovereign,Footnote39 would have made her the most powerful woman in the empire, and the second most powerful individual after the emperor. The financial implications and political reach of these new titles too appear to have been significant, as Nur Jahan began to matronise monumental architectural projects across the empire soon thereafter, beginning with Nur Serai, where she also employed the building’s epigraphic programme to advertise her pre-eminent position to the constant stream of travellers on this route.

The imperial proximity to divinity was also underpinned by the choice of certain phrases in the inscription that prompted heavenly associations. Thus, the serai was described as one ‘wide as heavens’ erected during the reign of Jahangir who was ‘the lord of the Universe, king of kings of this world and his time, the shadow of God’ according to the Delhi Darwaza inscription, while on the Lahore Darwaza, the emperor was pronounced one ‘whose like neither heaven nor earth remembers’ and the expression ‘angel-like’ was used for Nur Jahan, its impact heightened by the presence of many winged spirits on the gateway’s relief. Footnote40 Like God’s work was believed to be executed by angels on earth, the inscription may have been suggesting, so was Nur Jahan indispensable in the implementation of Jahangir’s will, as can be evidenced by the date of foundation of the serai, a Hijri year before his 1029 AH (1619 CE) proclamation to ease travel.Footnote41 Thus, not only does Nur Jahan appear to have been involved with the carrying out of imperial orders, but was possibly aware of them in advance, or even engaged in the process of their ideation. The aforementioned idea of co-sovereignty, and this expression of partnership in the exercise of empire-building, was accentuated further by the Delhi Darwaza inscription, where it identifies Nur Jahan not only as Jahangir’s hamdam or companion, but also his humsaz khas, a special collaborator in the process of creation.

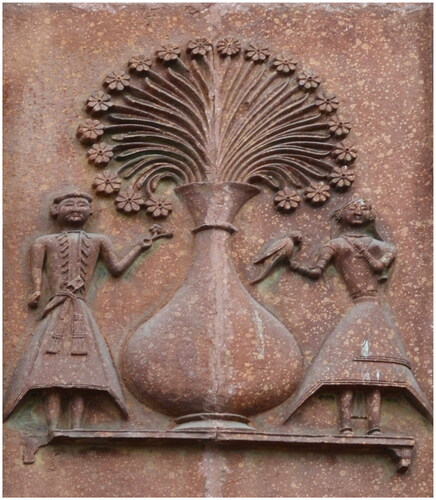

On the Lahore Darwaza this is supplemented, perhaps for the benefit of viewers unable to read Persian, by a sculpted red sandstone panel to their right (), where the same information appears to have been alluded to pictorially by two human figures. On this panel situated close to eye level, a man and woman stand on either side of a flowering vase. In his attire and Central Asian facial features, the man bears an imperial Mughal recall while holding out a sprig of flowers to the woman on his left, in the space traditionally reserved for the consort in art from MongolFootnote42 and Persianate societies. Likely suggesting equality, co-regencyFootnote43 and love, the woman is depicted in an identical dimension and stance as the male figure, and has been posed with one hand on her heart while a parrot perches on the other.Footnote44 However, it is only with a reading of the inscription reiterating four times the name of the matron above this panel, that the duo are elevated from being a generic rendering of a contemporary elite pair to their re-imagination as the imperial couple of Nur Jahan and Jahangir.

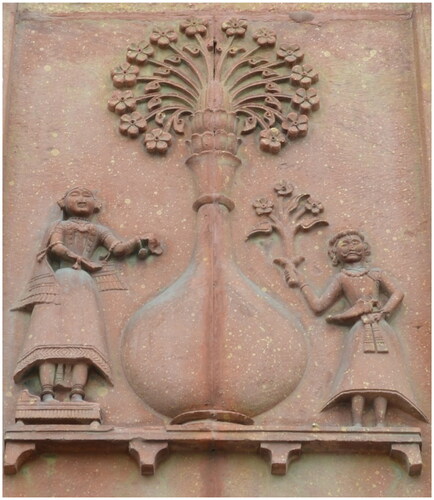

In a symmetrically placed panel on the other side of the entrance (), the female figure is again possibly representative of the empress, although this time significantly more regally dressed, a fact heightened in contrast with the sartorial choices made for the male figure. The scale of the female figure is also enlarged, and her stance on an elevated platform makes the power structure between the duo strikingly different from the couple on the first panel. The lower rank of the male figure is reinforced by his slightly bowed posture and in his act of offering a bouquet to the woman, which she appears intent on benevolently accepting from her upturned, open palms. The man is Hindu, going by the left-sided fastening of his angrakha (an upper garment), and probably Rajput from his moustache and tilak, the latter recalling Akbar’s practice of anointing Hindu Rajputs as Mughal courtiers by marking their foreheads.Footnote45 While his exact identity is difficult to ascertain, the figure appears to have been used to gender, and perhaps even racialise, the matron’s power as one that, with the exception of the emperor himself, was greater than men, even those holding court positions. As already noted by Cunningham, the workmanship of the panels is coarse,Footnote46 although this is easily explained by the fact that figural representation was not a forte of Mughal architecture and, even where they existed, remained peripheral to more central themes of geometry, calligraphy, vegetal, or zoomorphic relief. The Nur Serai figures are in fact the only ones of their kind, and in the manner of their usage, it is evident that their aesthetic attribute was of less significance than their underlying messaging.

The representation of Jahangir and Nur Jahan on the first panel and the description of their relationship in the inscription are also remarkable not only as a distinctly democratic account of a premodern marriage, but are also worthy of note as a citation of a marital relationship in epigraphy, as this was a remote occurrence in the premodern Islamic world, being in violation of expected codes of propriety. In addition to being a relationship too private to be acknowledged in such a public setting, it has also been conjectured that such mentions were rare because women rarely derived the power to build through their husbands, and usually only constructed as widows or single women. Thus, their identification of selves with respect to men were more routine as ‘mother of’, ‘sister of’, ‘daughter of’, and, at times, ‘widow of’ an individual.Footnote47 Hence, in Nur Jahan’s identification of herself as Jahangir’s spouse, not only is the liberal nature of Jahangir’s reign indicated, but also the matron’s leaning towards her spousal family, for reasons that could have been political as well as personal.

From the standpoint of furthering a political agenda, and given the elite standing of Nur Jahan’s natal family, especially her father’s position as the emperor’s wazir (approximately equivalent to a prime minister) and brother’s as wakil (a minister, but without any designated portfolio, often acting as an imperial agent), her identification as their daughter or sister too would have considerably evidenced her clout. But the fact that she refrained from mentioning them at all may hint at the onset of the breach between her and her natal family, particularly with her brother and Shah Jahan’s partisan, Asaf Khan, who are together believed to have been responsible for her eventual fall from power, exile and isolation immediately after Jahangir’s death.

However, Nur Jahan, Asaf Khan and Shah Jahan are known to have once presented a combined front of immense political influence that historians believe began to disintegrate around 1025–26 AH (1617 CE).Footnote48 While rifts between Nur Jahan and Asaf Khan may have been possible at this time, that Nur Jahan continued to support Shah Jahan as the next successor at least until 1028 AH (1619 CE) can be argued using the serai’s epigraphy. Of interest in this regard is the first couplet from the inscription on the eastern gateway where ‘During the reign of Jahangir Badshah, lord of the Universe’ was written in Persian as ‘Shahe Jahan Badaur Jahangir Badshah’. Here, the use of the descriptor ‘Shah-e-Jahan’ appears deliberate, given the well-known Mughal fondness for double entendres and established significance attached to names and titles. The consciousness of choice in this usage can be further evidenced by the fact that Khurram, the heir apparent, had only been awarded the title of Shah(-e-)Jahan in 1026 AH (1617 CE), two years before the serai’s foundation, after a victory in the Deccan and amidst much jubilation and festivity in which Nur Jahan had not only been present, but where she had showered the prince with valuable gifts.Footnote49 Including Shah Jahan’s name in the gateway facing the empire may have thus been a public expression of Nur Jahan’s support for his succession, which, in the aftermath of his prolific military career, would have also received popular sanction. This temporal manipulation by which the matron was likely immortalising herself as a part of the Mughal dynasty and its elite rulers can also be found in the Lahore Darwaza, where, by invoking the name of Akbar as the father of Jahangir, Nur Jahan appears to have wished to extend the longevity of her own authority across three successive reigns, farther both into the past and future than reality alone would have permitted.

3. Conclusion

As demonstrated, a critical and concurrent reading and viewing of architecture and epigraphy can breach the limits of formal concerns and foundational details, and open up instead a multitude of alternate dimensions that can, as in the case of Nur Serai, include the matron’s wealth and executive networks, investment in governance and charity, literary and artistic sensibility, dynastic allegiance and social conformity, political ambition and primacy. Here, compared to attitudes found in other typologies popularly matronised by Mughal women, where mosques and tombs routinely carried shades of hyperbolic religiosity and performative humility, the publicness and multivalence of the serai typology had perhaps been particularly conducive in the creation of a context that could anchor such a diverse range of ideas. The sheer volume of information also makes this transmission unlikely to be incidental, and encourages instead the appraisal of every material detail as a deliberate decision made to relay information considered significant by the matron. Overall, the manner in which architecture opens itself to exegesis is likely an expression of active female agency, in which can be identified a matron’s will to control and monumentalise her own representation. While the same may have been largely true for patrons as well, it can perhaps be conjectured that given the relatively fewer avenues of public expression and memorialisation available to women, the zeal to articulate their selves in structures and their engagement with architecture at large may have been greater and more conscious. Thus, to conclude, it is submitted that for matrons of architecture regarding whom limited credible, unmediated and primary sources exist otherwise, an interpretive path can potentially be traced backwards from a close examination of design decisions manifest in the built fabric to their maker’s creative ambition, in order to better understand their minds, motivations and, by extension, the societies that shaped them.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Richard Piran McClary, and my advisor, Professor Jason Edwards, for their guidance and encouragement with my wider doctoral research on Mughal architectural matronage, and to the University of York for the YGRS Overseas Research Scholarship. I would also like to thank the Tasavvur Collective for organising the ‘Writing Muslim Women in South Asia’ symposium, where an early draft of this paper was presented, and my reviewers and editors for their kind critique that has contributed greatly since then to bring it to this present form.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Notable exceptions to this include the works of Misra and Mukherjee, whose historic overviews of Mughal women are credible and balanced but limited in circulation. More widely recognised and recent works include those of Findly and Lal and, in the discipline of the History of Arts, the unpublished thesis of Chida-Razvi examining Nur Jahan’s engagement with Jahangir’s tomb as well as Bokhari’s overview of Jahan Ara’s repertoire of religious architecture are of significance: Rekha Misra, Women in Mughal India: 1526–1748 A.D. (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Oriental Publishers and Booksellers, 1967); Soma Mukherjee, Royal Mughal Ladies and Their Contributions (Delhi: Gyan Publishing House, 2001); Ellison Banks Findly, Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); Ruby Lal, Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World (India: Cambridge University Press, 2005); Ruby Lal, Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2018); Mehreen Mubeen Chida-Razvi, ‘The Imperial Mughal Tomb of Jahangir: History, Construction, and Production’ (unpublished PhD thesis, SOAS University of London, 2011); Afshan Bokhari, ‘Gendered Landscapes: Jahan Ara Begum’s (1614–1681) Patronage, Piety and Self-Representation in 17th C Mughal India’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Vienna, 2009). [AQ11]

2. Serai Nur is located at 31.0926, 75.5947.

3. John Jourdain, The Journal of John Jourdain: 1609–1617 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1905): 164; Peter Mundy, The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia: 1608–1667 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1914): 83–84; Jean de Thevenot and John Francis Gemelli Careri, Indian Travels of Thevenot and Careri (New Delhi: AES India, 1949): 57.

4. Thomas Roe, The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe in India: 1615–19 (London: Oxford University Press, 1926): 493.

5. Exceptions to this would include an overview section by Deloche, a taxonomical chapter by Dar, a documentation of sites on the Agra-Lahore road by Parihar, and a brief survey of four examples from the same region by Begley: Jean Deloche, Transport and Communication in India Prior to Steam Locomotion, Vol. I: Land Transport (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1993): 160–83; Saifur Rahman Dar, ‘Caravanserais along the Grand Trunk Road in Pakistan’, in The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce, ed. Vadime Elisseeff (New York: Berghahn, 2000): 158–84;

Subhash Parihar, Land Transport in Mughal India: Agra-Lahore Mughal Highway and Its Architectural Remains (New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2008): 99–301; Wayne E. Begley, ‘Four Mughal Caravanserais Built during the Reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan’, Muqarnas 1 (1983): 167–79.

6. The only listing of caravanserais matronised by Mughal women thus far has been undertaken by Blake, but only for Shahjahanabad: Stephen P. Blake, ‘Contributors to the Urban Landscape: Women Builders in Safavid Isfahan and Mughal Shahjahanabad’, in Women in the Medieval Islamic World, ed. Gavin R.G. Hambly (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998): 407–28.

7. While a discussion on Mughal women’s broader engagement with serai construction is beyond the scope of this paper, records of at least 29 rest stops by nine women from the period have been found over the course of this research along major corridors of travel, at market centres, and peripheral to cities near mosques, tombs and gardens of significance.

8. This formatting of dates is as Al Hijri (Common Era) and has been used consistently through the paper to recognise the Islamic calendar used by the Mughals.

9. Jahangir, The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India, trans. Wheeler M. Thackston (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999): 26.

10. Ibid., 26.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid., 310; The Jahangirnama also records that by 1034 AH (1625 CE), the construction of resthouses at every station along the way to Kashmir from Bahat Ghat and along the Pir Panjal route were already complete.

13. Ibid., 355, 372, 388.

14. Ibid., 355.

15. Findly, Nur Jahan, 245–46.

16. Catherine B. Asher, Architecture of Mughal India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008): 128; Bianca Maria Alfieri, Islamic Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2000): 234–35.

17. Alexander Cunningham, Report of a Tour in the Punjab in 1878–79 (New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1882): 64.

18. Lal, Empress, 52.

19. Cunningham, Report of a Tour, 64–65.

20. Ibid., 64.

21. Begley, Four Mughal Caravanserais, 168–79.

22. Parihar, Land Transport, 231–42.

23. Antony Eastmond, ‘Viewing Inscriptions’, in Viewing Inscriptions in the Late Antique and Medieval World, ed. Antony Eastmond (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015): 1.

24. Yashaswini Chandra, The Tale of the Horse: A History of India on Horseback (New Delhi: Picador India, 2021): 34.

25. Oleg Grabar, The Mediation of Ornament (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992): 16.

26. George Michell and Amit Pasricha, Mughal Architecture and Gardens (Martlesham: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2011): 272.

27. This particular winged creature, with the head of an elephant and the body of a lion, appears frequently in Jahangiri art, in carpets and miniatures, but, in its architectural use on the gateway, is likely a direct reference to the Delhi Gate of Agra Fort, constructed during Akbar’s reign, where at least 12 of them appear in panels of inlay.

28. George Michell, Mughal Style: The Art and Architecture of Islamic India (Mumbai: India Book House, 2007): 237.

29. Abul Fazl, Ain-I Akbari, trans. H. Blochmann (Lahore: Qausain, 1975): 309.

30. Fazl, Ain-I Akbari, 228.

31. Ibid., 292.

32. Such an intention can be understood in the context of the phenomenon where sub-imperial officials in provinces could have created the fiction of factual convergence between multilingual epigraphy, which, simply by virtue of their positioning, would have been assumed as translations by any reader who was not fluent in both languages. In her 1993 paper titled ‘Sub-Imperial Palaces: Power and Authority in Mughal India’, Asher discusses one such example found in Man Singh’s palace gateway in Rohtas, Bihar, where the Persian inscription is an extensive panegyric to Akbar with only the briefest reference to the actual patron, but its Sanskrit counterpart omits Akbar from the narrative altogether and aggrandises Man Singh’s authority with titles such as ‘the king of kings’.

33. The Delhi Darwaza inscription only bears the foundational date of 1028 AH (1619 CE), and was thus likely completed two years prior to the Lahore Darwaza, which also noted the date of completion of 1030 AH (1620–21 CE). Around 1295–96 AH (1878–79 CE), when Cunningham visited these monuments, the Delhi Darwaza is recorded to already have been a mass of ruin with no stone facing remaining. Henry Hardy Cole’s photographs of the serai, likely from the early 1870s, also focus exclusively on the Lahore Darwaza, suggesting that he too found nothing of value on the Delhi Darwaza.

34. Lal, Empress, 217.

35. A. Afzar Moin, The Millennial Sovereign: Sacred Kingship and Sainthood in Islam (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014): 181.

36. Ülkü U. Bates, ‘Women as Patrons of Architecture in Turkey’, in Women in the Muslim World, ed. Lois Beck and Nikki Keddie (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978): 257.

37. Lal, Empress, 101.

38. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 190.

39. Lal, Empress, 142–43.

40. This method of building divine associations may have been shared by Jahangir’s use of the motif of angels in Lahore Fort’s tiled wall, where a more explicit connection has been identified by Asher in the Solomonic imagery of angels leading jinns (invisible spirits in Arabic mythology) in chains, and Jahangir’s sole inscription in the fort where he is identified as ‘a Solomon in dignity’.

41. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 310.

42. Mehreen Chida-Razvi, ‘Power and Politics of Representation: Picturing Elite Women in Ilkhanid Painting’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 32, no. 4 (2021): 762–91; 773.

43. The idea of co-regency has been discussed at length by Nur Jahan’s biographers, Findly and Lal, and triangulated with textual and numismatic sources which evidence that Nur Jahan enjoyed imperial prerogatives such as having her presence announced by a drum after the emperor’s and having coins struck in her name, in unique instances from the Mughal world.

44. As Saleema Waraich points out in European Fantasies and Awadhi Aspirations: From a ‘Turkish’ Harem to a Lucknowi Zenana, for the case of a painting depicting a woman with a bird, the inclusion of a parrot in such a scheme would likely have carried a resonance of the popular tale of the Tutinama. However, a deliberate choice to recall this tale of a woman tempted to commit adultery every night that her merchant husband is travelling and prevented only by the tales of her parrot, on the gateway of a travel typology on a prominent trade route appears unlikely. In Women’s Wealth and Styles of Giving, Findly has discussed the Serai as an expression of Nur Jahan’s way to syncretise divergent visual heritages, particularly in the convergence of arabesque with naturalism, but also in the willingness to express the female form in sculpture. This argument can perhaps be extended to ponder if in the case that the figures were executed by Hindu sculptors, the parrot may have been a residue of an established tradition of depicting and carving apsaras (celestial nymphs in Indic mythology) with parrots, or driven by the parrot’s association with erotic love as the mount of Kama, but is ultimately outside the scope of this paper.

45. John F. Richards, The New Cambridge History of India: The Mughal Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1993): 21.

46. Cunningham, Report of a Tour, 62.

47. Bates, Women as Patrons, 248.

48. Findly, Nur Jahan, 161.

49. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 229.