Abstract

Attia Hosain’s Partition novel, Sunlight on a Broken Column (1961), offers possibilities for the physical structure of the home to be analysed through a spatial lens to decode architectural metaphors of the zenana (women’s space). This paper explores how the women characters negotiate with the often dichotomised private and public spheres of the home and outside, to show their rising confluence in a modernising nation. This paper grounds gendered space in the materiality of courtyards, walls, stairwells and rooftops to argue that the homosocial, homospatial bond that exists within the zenana courtyard is reinvented by Laila in the wake of the socio-political changes of the 1930s–50s, which allows for Laila’s imagined ‘world’ to become a reality. By studying the architectural sites of seclusion not as static but charged with agential capacity through their enclosed openness, this paper reads the courtyard as a transgressive space of resistive politics.

The zenana, or women’s secluded quarters at home, functions as a transgressive space in the writings of South Asian Muslim women in the twentieth century. The often polarising scholarship on the distinctions between the private and public worlds that women and men occupied, respectively, is taken up in this article to offer a new perspective from which these debates can be met, that of the spatial arrangement of the private world. I use the courtyard house in Attia Hosain’s post-Partition, post-Independence novel, Sunlight on a Broken Column (1961), as the architectural evidence of the dissolution of the two spheres mid century. By taking a spatial-material approach to the question of women’s agency, I argue that while the zenana can be a restrictive space for its inhabitants, it can also serve as a space of radical possibilities. Through the protagonist of the novel, Laila, I chart the trajectory of the zenana’s reclamation and reconstitution to serve its occupants, not the patriarchs who built it.

The zenana courtyard located in the physical and spiritual centre of the house operates as an intentionally hidden safe space, even though that does not guarantee their safety from the other members within that space. The roofless courtyard opens it up to internal and external forces of surveillance from family members surrounding the courtyard and from outsiders sensorily entering the courtyard through the open rooftop structure. This leads to women moving to the fringes of the courtyard, such as bedrooms, rooftops, corridors and staircases, to express their desires. The security afforded by the gendered seclusion of the courtyard is contingent on the behaviour of the women in that space. The illusive freedom afforded by the open structure of the closed courtyard () makes women retreat outside the margins of regimented openness towards a ‘radical openness’.Footnote1 The double marginalisation of the inhabitants as women and Muslims in twentieth century India is resisted by the self-double-marginalisation of zenana occupants into the recesses of the courtyard house’s inner outskirts that is strengthened by their homosocial, homospatial bond. In this article, I will rebuild the courtyard house as ‘radical architecture, an architecture of transgression’Footnote2 that Laila utilises as a ‘site of resistance’.Footnote3

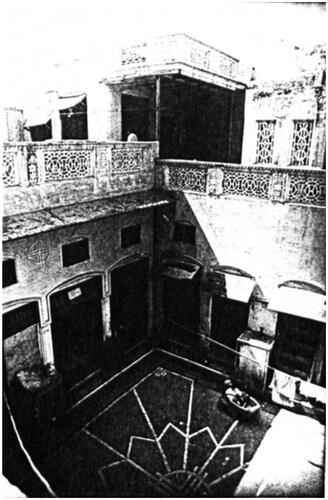

Figure 1. Photograph of Shafi Haveli in Old Delhi in 1986.

Source: Sunand Prasad, ‘The Havelis of North India: The Urban Courtyard House’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Royal College of Art, 1988), n.p., British Library EThOS, https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.425031.

Architectural historian A.G. Krishna Menon noted in an interview that a ‘house is never merely a maximum utilisation of space but a projection of the self that often one would like to be’.Footnote4 With the Indian nation modernising in the twentieth century, the zenana space of the courtyard was also changing as more Indians within the professional circles were moving into European-style bungalows, abandoning the traditional havelis that were large houses with multiple courtyards. And those families still residing within these structures were modernising from within. The courtyard as a phenomenological extension of the women living in that space was not inward-looking, as scholars have claimed.Footnote5 Shaista Ikramullah contested these claims in her autoethnographic account of life in the zenana by ‘lift[ing] the veil’ to showcase the ‘cross-section of society’ that could be found within the enclosed space of the South Asian Muslim home.Footnote6 Through social architecture, modernity was entering the zenana just as women and girls were ‘encountering modernity’.Footnote7 The hybrid structure of the courtyard, with its enclosed openness, serves as what Joelle Bahloul describes as the ‘intermediate place between the street and the home, a symbolic extension of each’Footnote8 through its social architectural interface, which I will take up in this article. This spatial fashioning is both traditional and modern, with tradition alluding to upholding the private space as exclusive and sacred, and modern reflecting the public space of the men’s world. The presence of the public within the private is not antithetical to prescriptions of modern living but a requisite of it. Just as ‘there is no outer without inner space’,Footnote9 the fluid boundaries of the courtyard house, with its most centrally located area facilitating a connection between the ‘home and the world’,Footnote10 the women in that space inhabit the juxtaposition of the private and the public. I show below how the lives of the women and their homes are intertwined in Hosain’s novel, and how their mutual relationships undergo changes with shifting conceptions of seclusion in the zenana courtyard.

The lives of Laila and Ashiana

Attia Hosain (1913–98) was born into a family of privilege, wealth and social status. As the daughter of a taluqdar (aristocrat) of Oudh, an erstwhile state in North India known to the British administration as the United Provinces, she was educated in La Martinière School for Girls in Lucknow, but also given lessons in Urdu and Arabic at home. Attia Hosain reflected that ‘although she and her sisters “were not in pardha in the sense that we were wearing burqas when we went out…we had a confined kind of a life”’.Footnote11 She was politically influenced by the Progressive Writers Association—‘I was at the first Progressive Writers’ Conference and could be called a “fellow traveller” at the time. I did not actively enter politics as I was (and may always have been?) tied and restricted in many ways by traditional bonds of duty to the family’.Footnote12 She graduated from the University of Lucknow in 1933 as the first woman from a feudal family to have done so. She wrote short stories which were published in the collection, Phoenix Fled, in 1953. During Partition, Hosain moved her family to England and worked in broadcasting and presented her women’s programme on the Eastern Service of the BBC.Footnote13

Attia Hosain’s only novel, Sunlight on a Broken Column (henceforth, Sunlight), written in the 1950s and published in 1961 by Chatto and Windus, London, is an Anglophone novel whose title is taken from T.S. Eliot’s poem, ‘The Hollow Men’ (1925). Hosain maintained that her novel was not autobiographical but what is now considered autofiction, or in Mobeen Hussain’s articulation, ‘autobiographically inspired realist fiction’Footnote14—‘Every first novel or any novel will have to be part of oneself and people one knows, but it is not the people and it is not actually the events but it is at the same time yes’.Footnote15 When asked about her motivations for writing the novel, Hosain stated, ‘People are forgetting all those things, they are forgetting that other world that I actually lived in, existed. There were people then who believed in the future’.Footnote16 Disillusioned by the events of 1947, Hosain writes Sunlight as a fictionalised memorialisation of women’s lives and the nation that ceased to exist, and the nations that were violently born.

Hosain begins Sunlight by introducing her readers to the central feminised character of the novel: Ashiana, the name of the ancestral house where Laila and her family members reside, which in Persian means shelter or home. The first line of the novel, ‘[t]he day my aunt Abida moved from the zenana into the guest-room off the corridor that led to the men’s wing of the house, within call of her father’s room, we knew Baba Jan had not much longer to live’,Footnote17 alludes to the impending dissolution of segregated spaces that began with the patriarch Baba Jan’s eventual passing, leaving the house open to influence, internal and external. Drawing on Hosain’s own family heritage, the novel follows a taluqdari (feudal) family of Ashraf (Shia Muslim elite) status, residing in Lucknow city. Laila is an orphan who is taken care of by her Aunt Abida, her Uncle Hamid, and servants in the house like Ustaniji, who is at the top of the hierarchy of servants, tasked with the religious education of the girls in the household, and Hakiman Bua, who is their cook. The novel is divided into four parts with the first three parts set in the past and retold by an adult Laila in post-Independence India, and the last part set in the present, in 1952.

Part 1 begins in 1932 with a 15-year-old Laila acclimatising to life at home without Baba Jan’s shadow, with Aunt Abida taking the domestic reins of the household, and Uncle Hamid looking after her as her guardian. Under the new arrangement, she is allowed to continue with her Western-style education by going to a missionary school but is required to follow Islamic codes of conduct by maintaining purdah. She lives with her cousin, 17-year-old Zahra, and her distant cousin, 18-year-old Asad, is a college revolutionary who follows the Congress agenda, and is their contact with the outside world as he brings news to them. This section ends with a family trip to their haveli in Hasanpur, their ancestral village, where the family members first perform the last rites for Baba Jan, and then get both Zahra and Aunt Abida married, a decision taken by the new head of the household, Uncle Hamid.

In Part 2, Laila’s time spent in Ashiana is ‘outwardly acquiescent’ under Uncle Hamid and Aunt Saira’s rule.Footnote18 However, it is through her friendship circle in college that she encounters dissenting political viewpoints. When Zahra and her husband visit Ashiana to attend a reception hosted by the taluqdars, it provides Laila with her ‘introduction into her social world’, which she is ‘frightened’ about.Footnote19 However, at the function, she meets Ameer, a college friend of Asad’s with whom she becomes romantically involved. Once they all leave, she is kept company by the gardener’s daughter and domestic helper, Nandi, who invites her into the adjacent world of the servants’ quarters surrounding the servants’ courtyard. This space of the house, not frequented by the family members, is where Nandi criticises the elitism of purdah. While upper-class (and -caste) women maintain their izzat/honour by residing in the protected sphere, Nandi has to go outside to work, where she is subjected to sexual harassment due to the lack of protection that purdah might afford her. While it is not true that purdah keeps women completely safe (as male family members are allowed to enter the zenana, and could harass women), Laila is confronted with the privileged position of comfort that her home’s aangan (central courtyard) affords her.

Part 3 opens with a new chapter in Laila’s adult life: she is now 19 years old, with relatively fewer purdah restrictions, when her Cambridge-educated cousins (Aunt Saira’s sons) Kemal and Saleem return to India. She joins them in their social gatherings at home and in clubs and continues to meet Ameer and their love intensifies. Although her uncle and aunt oppose their union due to Ameer’s poor background, Laila openly resists for the first time, and chooses Ameer because ‘[w]hen I think of you [Ameer], I have all the courage in the world, because about you there are no doubts’.Footnote20

Part 4 is Laila’s narrative memorialisation of her life before and after Partition. In 1952, she returns to Ashiana, ‘the home of my childhood and adolescence’.Footnote21 Readers learn that she left home 14 years ago to be with Ameer whom she marries, and although she left many years before the migration began, the house stands as a ‘living symbol’ of ‘ill-digested modernity’ because it is no longer a house to Laila but ‘a piece of property’.Footnote22 The ‘decay’ of Ashiana after it was abandoned by its family members, when her cousin Kemal sold it to the government and moved to Pakistan, represents to Laila the ‘ugly’Footnote23 modernity of postcolonial India where the nostalgic spaces of her childhood are turned into settlement camps for refugees or handed over to relocated families. Although the physical structure of the house remains the same, its purpose changes as multiple families now reside in the haveli, making the courtyard not an exclusive space for the women of a single family, but a communal courtyard for all to use. Modernisation of the house is marked by its utilitarian purpose, caused by the violence of Partition, which leaves it feeling less like a home and more like a residence.

As she relives and recalls her time in Ashiana wandering through the different rooms, the material spaces evoke emotions of longing for a stifling, yet cherished time spent in the haveli. Sunlight traces, through the Bildungsroman of Laila, the life cycle of a nation by utilising the metaphor of Ashiana. Laila’s adolescent years are spent in the courtyard wishing for freedom, but when freedom comes (as she makes her home with Ameer in the hills), it is fleeting (Ameer dies in World War II) and she is left again without a home. The novel ends with Laila and Asad (her childhood friend and cousin) reuniting, not necessarily for love but for comfort and stability, someone to fill the ‘empty house’Footnote24 in which she has been waiting. Her eventual settlement underscores the permanent rupture of home that Partition caused for many families, which can never be brought back, except in memories. All Laila and others can do is to keep a semblance of the ‘illusion’Footnote25 of the past alive by recreating those bonds in new spaces.

A zenana of their own: Crossing thresholds and determining mobility

During the colonial period, the havelis of feudal families (like Hosain’s) took on the task of modernising from within, a change that is explored in the ‘socially aware domestic fiction’Footnote26 of women writers of twentieth century India. As prominent writer Shashi Deshpande has claimed in an interview, the domestic arena is ‘where everything begins’;Footnote27 it becomes imperative to study the family unit in the space of the home as the site of inception of the agenda of colonial modernity. Antoinette Burton in Dwelling in the Archive points to the knowledge possessed by many of these writers that the ‘home could and should be the centre of social life’.Footnote28 Thus, despite the secluded zenana’s ‘introverted world, folded in upon itself’,Footnote29 it is not static in its folded form, but opens outward when needed. The physical barrier of closed doors and windows, folding the courtyard in on itself, is supplanted by the terraces and latticed windows that resist the complete fold. This tension between complete seclusion and mediated spatial and sensorial mobility is acutely felt in the younger generation of girls who tussle between the traditional wisdom imparted by their elders and the Western values promoted in Christian missionary schools and colonial social clubs. For girls, Indian feminism at the time was germinating out of the dual agendas of (re)inhabiting the house as nation through a ‘demarcation of boundaries that was both new and familiar—with the imaginative and material spaces of house and home at the heart of such reterritorializations’.Footnote30 In defining space as their own, by marking their own territorial boundaries, and creating this in-between space, the purdahnashin (those hidden behind a screen) situated themselves not only in space but in Indian ‘Modern Times’, not as archaic, but ‘residual (formed in the past but still active in cultural processes)’ women.Footnote31

As a ‘residual woman’, Laila in Sunlight communicates the crisis she faces between her personal past and present, the pre-Partition and post-Partition India and the premodern and colonial modern domestic gendered imaginaries. In the course of the novel, Laila’s world opens up, one window at a time. As a teenager, she is ‘walled in’ even as there are moments of light streaming in. She describes the portion of the house that she inhabits: while the drawing-room that unites the two wings of Ashiana carries ‘shadows’ and ‘strange music’, ‘[i]n the corridor beyond [opening onto the zenana] there was light. It broke into the patterns of the fretted stone that screened this last link between the walled zenana, self-contained with its lawns, courtyards and veranda’d rooms, and the outer portion of the house [into the men’s quarters]’.Footnote32 The familiarity of the space is oppressive and liberating at once for it houses comfort while serving as what Gillian Rose has called an ‘ideological prison’.Footnote33 Muslim feminist scholars debate the contentious claims of a harem and/or zenanaFootnote34 serving as a ‘protected space’ for women, as Leila Ahmed argues,Footnote35 or an oppressive spatial mechanism ‘of incarceration’ to keep women locked inside, as Fatima Mernissi claims through her own experience.Footnote36 In either form, the harem and the zenana share a homosocial organisational structure that facilitates bonds between its occupants. This dichotomy of protection/incarceration is merged in the lived experience of Laila who oscillates between wanting to step outside the confines of the zenana and yearning to be inside the homosocial space with her close family at various junctures of her life. The courtyard space functions doubly as ‘separate worlds and symbolic shelter’.Footnote37 Despite contrasting notions of the function of purdah by scholars, they all present evidence of life behind the purdah, challenging early Western ethnographic assumptions of stillness. Despite the restrictive nature of the zenana space that many women like Mernissi have felt imprisoned in, they offer a curated structured living of their own machinations.

These prisons are not silent; they circumscribe within their social architecture a pattern of life that is exclusive to the zenana. Laila illuminates the various uses of the courtyard depending on the status of the family member. During the summers, the men and women of the inner family circle bring out their cots and sleep in the open air in the courtyard. At all times, the courtyard bustles with activity: ‘Aunt Majida was bent over a basket cutting betel nuts, Aunt Abida was making pan. Hakiman Bua was sitting on the floor near Aunt Abida waiting for her orders to bring in the tray of food’.Footnote38 Cousins Zahra, Zainab and Laila escape, either to ‘a terrace in the oldest part of the house which was almost always deserted’ to ‘be on our own’,Footnote39 or to the ‘neighbouring orchard. It was surrounded by a high mud wall so that it was possible for purdah women to walk in it’.Footnote40 Adjacent to the main courtyard is the servants’ courtyard and veranda which has ‘a life of its own’ away from the prying eyes of the women of the household. Laila goes there to meet Nandi and receives gossip about the servants’ lives. The life-force of the zenana is sapped when Aunt Abida, Zahra and Nandi get married and leave the house. Without their warming presence, the escape routes within the house become foreboding and the place becomes still. Laila then finds a way out of the house, which becomes increasingly inhospitable, through her male cousins Kemal and Saleem. They act as chaperons as she enters the world of social gatherings and parties, where she meets Ameer. And yet, she longs for the reunion of her family in Ashiana ‘as if our yesterdays had returned’.Footnote41 As Bahloul argues, ‘domestic space serves as a metaphor for the human entity that inhabits it. Domestic space is the space of memory’.Footnote42 Ashiana is home for Laila when the bounds of the inner space are tethered to women. Without its residents, it’s a ‘property’ that only exists for her as ‘artefact memory’Footnote43—a house turned relic only serving as a container for her ‘yesterdays’.

The zenana offers possibilities for vertical expansion despite its horizontal confinement, which allows its occupants certain freedoms to express themselves. As they are not completely boxed in, they find channels to take up more space. Aunt Abida distinguishes a walled prison from a coffin when she insists that Zahra be present when the elders in the family arrange her marriage. She argues:

The walls of this house are high enough, but they do not enclose a cemetery. The girl cannot choose her own husband, she has neither the upbringing nor the opportunity…. But…she can be present while we make the choice, hear our arguments, know our reasons, so that later on she will not doubt our capabilities and question our decisions. This is the least I can do.Footnote44

Different women conceive of their spatial mobility in different ways, with the older generation holding on to prescribed values of duty and obedience, and the younger generation demanding freedom of choice. This determines their positions within the spatial framework of the zenana and constitutes the limits that enforce their own enclosures. The rift in the zenana is visible in Aunt Abida’s treatment of Laila after she elopes; she refuses to see her or reply to her letters. Her closest family member and a maternal figure, Aunt Abida cannot accept Laila’s indiscretion. To Aunt Abida, selfishness is sin and duty to the family is above all—the reason she herself marries a man whose family treats her poorly, because an unmarried woman is unacceptable in society. In their final meeting, Laila realises that reconciliation beyond a point is not possible under the dictates of the ‘Law of the Threshold’, theorised by Malashri Lal. The zenana threshold is set by patriarchal ideologies of women’s duty, purity and sanctity which are tied to the home. Lal delineates the three structures of the threshold: inside the threshold, on the threshold, and outside the threshold.Footnote45 As the demarcations between the three positions are fluid and porous, the various women drift in and out of various positionalities during different instances. For example, Aunt Abida, for the most part, stays inside the threshold, which is defined by the relegation of women to the private sphere. However, after Baba Jan’s death, she begins to assert herself outside the zenana by making more decisions for the household and allowing more freedom to her nieces, Zahra and Laila. She fluctuates between staying inside the threshold/zenana and being on the threshold, which is marked by ‘strenuous poise’ and a ‘delicate balance’ between the inside and outside.Footnote46 It is a ‘turbulently contested space, where influences from inner/outer, private/public spheres act’.Footnote47

The interference inside the walls of the zenana, characterised by Laila’s Western-style education and socialisation into the modern world, connotes the changing norms of the zenana. Exposed to different world-views and lifestyles, Laila begins questioning her own, which reconstitutes her view of being a woman in modern society. Unlike Aunt Abida who cannot cross the threshold of the inner courtyard beyond certain transgressions, Laila, during her growth into adulthood, goes from being raised inside the threshold under her parents’ and aunts’ guidance to the external influences of her school friends seeping into her conduct at home. For example, when a scandal breaks out in Laila’s college about a ‘Muslim girl, from a strict purdah family, [who] ran away with a Hindu boy from the neighbouring college for boys’ and was then abandoned by the boy under pressure and as a result, took her own life,Footnote48 Aunt Saira and her visitors, Mrs. Wadia and Begum Waheed, discuss the ‘dishonour’ in the zenana as Laila returns from college. These seemingly progressive women—Aunt Saira champions women’s education, Begum Waheed and Mrs. Wadia petition the Municipal Board to open ‘purdah parks’ and ladies’ clubs to ‘teach [ladies] new ways of being social’Footnote49—cannot accept interfaith relationships and are glad about her ‘punishment’ (death). For the first time in the novel, Laila speaks up by blurting out ‘she was not wicked’.Footnote50 This moment of Laila stepping onto the threshold and challenging the norms of zenana lifeways foreshadows her own eventual ‘wickedness’ when she leaves Ashiana for Ameer. As Tanvir Sachdev explains, ‘the threshold becomes a factor not only in the imposition of tradition but an outward modernity as well, articulated through new roles expected of women contingent with bourgeois aspirations in colonial times’,Footnote51 which members of Laila’s family display along with Begum Waheed and Mrs. Wadia.

Laila wrestles with the dichotomy between the inside and outside and adopts a spectator position, performing ‘selective transgression’.Footnote52 She is aware of the limitations of the zenana: when Uncle Hamid asks for her opinion on a student protest in college, she sardonically points out the illusion of freedom that she possesses:

[Uncle Hamid:] ‘What do you think about it?’

I hesitated, ‘I’m sorry, I consider the question irrelevant’.

‘Have you no freedom of thought?’ he asked with sarcasm.

‘I have no freedom of action’.Footnote53

The movement between various positions of the threshold reflects the unique strategies of women of Laila’s (and Hosain’s) generation who grew up in the 1930s and 1940s when identities came to be challenged while the nation was on the cusp of social transformation, eliciting similar peregrinations from its youth. As a result, Laila is an ‘onlooker who watches, listens, absorbs, and remains open to competing claims’Footnote55 at home with her empathy for her parents’ generation who did not have the same opportunities to transgress, and at school and college when she is presented with myriad world-views in her friendship circle that make her more open to transgressive articulations.Footnote56 It positions her as what T. Minh-ha Trinh has called ‘both-in-one insider/outsider’Footnote57 as she straddles the home and the world in a ‘middle-state’, in the in-between space of the courtyard which connects the world through the ‘isthmus’Footnote58 of architectural transgressions.

Laila’s worlds: The spectator becomes the agent

Laila articulates the disparate realities of her life through the symbolism of ‘worlds’—one that she is born into, and one that she escapes to. In her younger years, her created world is the world of books and imagination, as she devours romance novels and fantasy epics from her deceased father’s library and by borrowing from her school friends. She grows up escaping to the boundless expanses of her imagined world, relinquishing her ‘real’ world with its rules, customs and traditions. Even as she was a ‘spectator’Footnote59 of others’ action (in the case of Nita and Asad), she is the agent of her solitary existence. She remarks, ‘I felt I lived in two worlds; an observer in an outside world, and solitary in my own—except when I was with the friends I had made at College. Then the blurred, confusing double image came near being one’.Footnote60 Being with her friends and witnessing their resilience instils in Laila the confidence to transfer the agency that she feels capable of in her solitary world into the social world of her reality. She struggles to ameliorate the worlds of inside/outside. The inner world of her mind develops in the physical world of spatial interiors, characterised by hidden bedrooms, sequestered rooftops and narrow winding staircases. As she ventures out into public, social spaces, her agential capacity expands to accommodate an extended reality that is plausible to execute.

She displays a stubborn abhorrence for all that her family represents, which prematurely hampers her own development as an individual. Laila’s world:

was bounded by our books, and the voices that spoke to us through them were of great men, profound thinkers, philosophers and poets.

I used to forget that the world was in reality very different, and the voices that controlled it had once been those of Baba Jan, Aunt Abida, Ustaniji, and now belonged to Uncle Hamid, Aunt Saira. And their friends. Always I lived in two worlds, and I grew to resent the ‘real’ world.Footnote61

[Zahra:] I won’t be teased, Laila. One day I’ll get my revenge when you creep out from between the jacket-covers of your books into the world.

[Laila:] Which world, Zahra? The world of your past or your present?

[Zahra:] Wait and see. There is only one—the world one lives in.Footnote63

Ameer also notices Laila’s worlds, postulating that she was unaware of his presence in university as she ‘belonged to another world, guarded by a thousand taboos fiercer than the most fiery dragons’, to which Laila counters, ‘until one day I ventured out into another world’.Footnote65 Before meeting Ameer, Laila was ‘in no hurry to leave’ her ‘make-believe world’;Footnote66 after meeting him, she learns that while the metaphysical barriers of her reality could be surmounted in her dreams, she would have to make concrete decisions in order to realise that dream. After leaving her family home, Laila feels liberated, yet life beyond the home does not live up to her dreamt fantasy life. Initially, she was ‘happy to have a home of my very own, to live in it as I pleased without dictation, though it was small and simple, and without scores of servants as in Hasanpur and Ashiana’;Footnote67 however, her whirlwind romance with Ameer is followed by the reality of expectations not met. Ameer grows resentful of his job as a low-salaried schoolteacher, unable to provide for his family as he had hoped; he is embarrassed and felt ‘hurt if I [Laila] suggested I should use mine [money], or if I did so, trying to hide it from him’.Footnote68 It creates a chasm between them that Laila cannot fathom: ‘In the beginning I blamed my elders because it was their world and its values [the lifestyle of a taluqdari family] that had broken into ours. I was not ready to accept that vulnerability was self-created’.Footnote69 Her ‘home of her own’ is not the sanctum she had envisioned. When Ameer joins the Army in the Public Relations branch and loses his life in the Middle East, Laila moves herself and her newborn daughter to their ‘small cottage in the hills’ and contemplates the reasons for starting a new life with Ameer. Although she did it out of love, it had also stemmed from an impulse to break away from her elders’ world. Despite some happy years together, she could not shake the invisible influence of her family’s traditions, which manifested itself in the form of financial and social expectations to which Ameer was not immune.

She had left the womb of her house once for Ameer, but he could not fill the role that the protective screen of the zenana had provided for her. Laila gives birth to a baby girl Shahla who symbolises a ‘miracle’ untainted by the impositions of family identity. When Nandi comes to live with them in the hills, Laila finally finds the community that she had been yearning for, a zenana of their own in which to raise Shahla. In the last chapter of the novel, Laila is back in Ashiana, looking at herself in the mirror:

I looked more closely at the face that stared back at me from the dusty mirror. That was how she and Ameer would be for ever while I grew old.

She was so different from me, that girl whose yesterdays and todays looked always towards her tomorrow, while my tomorrows were always yesterdays.

I began to cry without volition and seeing myself crying in this room to which I would never return, knew that I was my own prisoner and could release myself.Footnote70

Home as haven/prison: The reconstitution of space

Laila recognises the dual function of the courtyard house as a haven and prison at a young age, but her position inside the threshold at the age of 15 at the start of the novel shields her from the dangers on her side of the line, which she becomes privy to as she grows older. The aangan (courtyard) blankets young Laila, wrapping her in its matrifocal circle. We learn that ‘life within the household ordained, enclosed, cushioning the mind and heart against the outside world, indirectly sensed and known, moved back to its patterned smoothness’.Footnote73 The protective cushioning of the courtyard as a safe haven falls apart as Laila begins to step outside the home. It then becomes oppressive.

The vertical openness of the zenana courtyard invites the anti-colonial political consciousness to enter the enclosed spaces inside the home through sensory touchpoints. While we have seen in the previous section how Laila’s ventures outside the home bring progressive ideas inside with her, the wave of socio-political activities seeps in even when the residents are inside. The aural exposure to the world outside, through the ‘cries of street vendors beyond the high, encircling walls, the rise and fall of chanted couplets’,Footnote74 no longer satiates Laila’s appetite for experiencing life on the other side. While her male cousins are outside, demonstrating in protests on the streets against the British Raj, she can only hear the ‘distant noise of shouting’ as it grows louder and comes closer. She runs from the ‘silent group [of women] in the veranda towards the stairs leading up to the roof’ to catch glimpses of the students who chant in unison, ‘Inquilab…Zindabad! Long Live Revolution!’Footnote75 From within the confines of the zenana, Laila can passively participate in the national movements precisely due to the spatial apparatus made available to her, namely the open rooftops from where she can peer outside. The roads are ‘alive’ but life inside the zenana is ‘quiet’ as they wait in anticipation for the return of her cousin Asad. Her school friend Nita Chatterji joins the protests, while she stews in her ‘inaction’.Footnote76 The restrictions placed on her mobility provide security for Laila as Asad returns wounded and Nita suffers a fatal head injury; however, her lack of choice in participating cements for Laila the physical prison from which she cannot escape. Laila is unsettled by her hesitation to join the forces, which Asad remarks on. When Laila asks him, ‘Why do you not taunt me about inaction as Nita does?’, he answers, ‘Because the urge for action must come from within you. It cannot be created by taunts’.Footnote77 He brings to the fore the ideological prison that Laila inhabits, escaping which will require more than a physical exit.

What motivates the reconfiguration of the zenana drastically is not Laila’s political activism, but romantic desire that is the catalyst for change. Each woman must confront a different set of stakes in desiring to cross the threshold; the consequences also differ based on their position in the family. This ‘urge for action’ comes later for Laila, not in joining the nationalist movement, but in asserting her will to be with Ameer. The first step she takes is to leave the physical confines of Ashiana, which catapults her out of the metaphysical prison as time goes on:

My life changed. It had been restricted by invisible barriers almost as effectively as the physically restricted lives of my aunts in the zenana. A window had opened here, a door there, a curtain had been drawn aside; but outside lay a world narrowed by one’s field of vision. After my grandfather’s death more windows had opened, a little wider perhaps, but the world still lay outside while I created my own round myself.

Now I was drawn out, made to join in, and not stand aside as spectator. Yet the private refuge remained in readiness for withdrawal.Footnote78

The narrative raises the possibility of going back inside the threshold, but in a reconstituted fashion. This time, it is Laila’s choice to seek the comfort that the zenana provides, but on her own terms. After the disillusionment of her separation from her family and childhood, the death of her husband and father of their two-year-old daughter Shahla, and the Partition of the country, she longs for the female society of the zenana of her yesterday when she visits Ashiana: ‘The fabric of her illusions had begun to wear thin, but it wrapped her in simulated warmth. Her eyes refused to see dust and decay; they created a twilight that did not pick out cobwebs’.Footnote79 The ‘sensation of “feeling” our roots’Footnote80 had engulfed her ever since leaving Ashiana the first time, and she thus created her own women’s space in her ‘small cottage’ in the hills. For the past 14 years, Nandi, their fierce domestic helper who had suffered due to her outspoken resistance to upper-class and -caste misogynistic treatment towards her as a putative sex object by men in Ashraf families, had stuck by Laila and worked for her new family as an ayah (nanny), taking care of Laila’s daughter like her own. She came ‘knowing she would be safe here’.Footnote81 For Nandi and Laila, building the zenana on their own terms affords a truly radical openness that was lacking in the zenana of Ashiana. Hosain offers a glimpse into such a dwelling where the openness is not illusory, but genuine as the women are able to map out its spatial points of entry and exit according to their wishes.

Laila creates a reinvented space in her new house that reflects the values of the community of the zenana but makes space for individuality of thought and action. Nandi is not only the ayah, but Laila’s friend, confidante and her connection to her old world, a tie she does not want to sever; this homosocial, homospatial bond is sought by Laila when raising her daughter in the new nation. When she visits her room in Ashiana, she is overcome by emotion as she looks at herself in the mirror and sees the young Laila of her childhood who felt restricted by her physical mobility in the house. Now, she realises that ‘I was my own prisoner and could release myself’Footnote82 as she leaves Ashiana a second time after her visit, to be with Asad. By creating her home with those who represent the life she left behind, and her daughter who symbolises rebirth, Laila breaks the dichotomy of the dyads proposed by Kumkum Sangari of ‘precolonial-premodern’ (here represented by the zenana courtyard) and ‘conservative modern’ (represented by the neocolonial bungalow)Footnote83 by ameliorating the two to create what I call a ‘primordial-modern’ spatial identity in postcolonial post-Partition India. The new home that Laila creates is primordial in upholding the fundamental ethos of the zenana female space as co-inhabiting and nurturing, while also being modern in its openness to the outside world by staying in a nuclear arrangement with her husband and child and aspiring for a career outside the four walls of the courtyard. Laila converges her past and present to forge a future that is capable of housing the radical conception of home of which Laila is the architect. She thus conceives of bell hooks’ notion of ‘radical openness’ by rebuilding and reimagining the courtyard house of her childhood as a structure that does not imprison, but rather offers shelter to its inhabitants. Her new home in the hills as ‘radical architecture’ is governed on the principle that women make the space and are its primary architects as they decide its openings and exits.

Her return to Ashiana at the end of the novel removes the smokescreen of nostalgic memories that dictated her younger preoccupations with seeing the house as a safe haven with umbilical ties to the security of the womb.Footnote84 Now, Ashiana resembles any other house on the street, and the reality of her confinement settles in. When inside the house, she basked in the sunlight that streamed in from the roofless courtyard, from the latticed windows and from the ‘broken columns’ of the windowpanes, but looking in from outside, as ‘she stood in the sunlight and looked into the cold shadows of the sightless house with its locked doors’,Footnote85 she feels on her skin the sunshine of her true freedom. The title of the novel alludes to the sunlight that, when streaming into a private room through a broken column, is refracted and altered. Laila’s curtailed mobility when growing up in Ashiana is similarly disguised by its architectural structure that promises access to the outside world through its illusion of openness (the window allows her to look outside, but not be outside). But a closer look reveals the invisible barrier of surveillance and policing that filters the freedom granted to its young female inhabitants. Sunlight streaming in through the broken columns of the windows of Ashiana differs from Laila’s experience of the sunlight on the open lawns of the house or the street adjoining the home that she fully owns; this realisation comes to Laila when she leaves the only home she has ever known, to create a home of her own with Ameer in the hills, and again, when she chooses to be with Asad at the end.

Conclusion

The spatial structure of the courtyard house that encloses a central roofless courtyard and rooms along its circumference offers dual interpretations of openness and closeness to its occupants and the readers. In this article, I have proposed that in the early twentieth century, with the changing currents of the nationalist movements and modernising efforts, the zenana of the previous century begins to crumble as women within the space assert their agency to enlarge the boundaries of the space. The rooflessness of the courtyard, which previously only afforded an illusory freedom through the expanse of the sky above, now brings real interference in the lives of Laila and the other women in Attia Hosain’s Sunlight on a Broken Column. Worlds meet in the interstices of her interactions between the inside and outside. Laila initially ascertained that the solution to her ‘zenana mentality’Footnote86 was to discard those aspects of the zenana that nurtured her. The zenana courtyard, like a womb, restricts her movement, but also provides nourishment through its homosocial environment. What Laila desires is to transform her position from an ‘insider-outsider’ to one who is ‘reterritorialised’ as an insider both in her home and in her world. Sunlight provides the women residents of the courtyard house the opportunity to ‘encounter modernity’, as Gopal argued, in a manner that suits them. Laila recreates the homosociality of the zenana outside the haveli, in a modern house that allows for more mobility and freedom of thought. This new Ashiana holds space to house her radicalism, giving her what she lacked under her Aunt Abida’s and Uncle Hamid’s guardianship—‘freedom of action’. By revisiting the polarisation of public and private spaces in Muslim women’s scholarship, I study the architectural blurring of those boundaries extant in the zenana to posit that spatial-agential capacities are realised by Muslim women who reconstitute the nature of their seclusion.

Acknowledgements

I would like to principally thank my PhD supervisors, Professor Michelle Keown and Professor Paul Crosthwaite, for offering valuable feedback that has allowed me to think beyond regimented disciplinary studies and widen my scope of engagement with questions of gender. The readers have meticulously combed through my earlier draft and helped clarify my authorial voice. South Asia journal editor Professor Shameem Black’s perceptive comments have allowed this paper, and this special issue, to take its present shape, for which I am grateful. And lastly, my academic co-conspirators of the Tasavvur Collective, Fatima Naveed and Zehra Kazmi, with whom I’ve had the opportunity to present a melange of writing in this special issue that speaks to the polyphony of thought and experience within Muslim women of South Asia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. bell hooks, ‘Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness’, in Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction, ed. Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner and Iain Borden (London: Routledge, 2000): 203–9; 203.

2. Elizabeth Grosz, ‘Woman, Chora, Dwelling’, in Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction, ed. Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner and Iain Borden (London: Routledge, 2000): 210–21; 216.

3. hooks, ‘Choosing the Margin’, 208.

4. Conversation between A.G. Krishna Menon and Geetanjali Singh Chanda, recorded in Geetanjali Singh Chanda, Indian Women in the House of Fiction (New Delhi: Zubaan, 2008): 42–43, emphasis added.

5. King characterised the courtyard house as ‘introverted’, Francis and Nath said it was ‘secluded from the outside world’, and Menon called the haveli the ‘palimpsest’ of the modern home that was ‘outward-looking’: s

ee Anthony King, The Bungalow: The Production of a Global Culture (London and Boston, MA: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984): 35; Wacziarg Francis and Aman Nath, Rajasthan: The Painted Walls of Shekhawati (New Delhi: Vikas, 1982): 21; Menon, quoted in Chanda, Indian Women, 39–43.

6. Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah, Behind the Veil: Ceremonies, Customs and Colour (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953): 3.

Feminist historians have upended early claims by Orientalist scholars of the ‘monolith’ of the zenana space: see Antoinette M. Burton, Dwelling in the Archive: Women Writing House, Home, and History in Late Colonial India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); Inderpal Grewal, Home and Harem: Nation, Gender, Empire and the Cultures of Travel (London: Duke University Press, 1996), as examples.

7. Priyamvada Gopal, The Literary Radicalism in India: Gender, Nation and the Transition to Independence(London: Routledge, 2005): 62.

8. Joëlle Bahloul, The Architecture of Memory: A Jewish-Muslim Household in Colonial Algeria, 1937–1962, trans. Catherine du Peloux Ménagé (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996): 42.

9. Inga Bryden, ‘“There Is No Outer without Inner Space”: Constructing the “Haveli” as Home’, Cultural Geographies 11, no. 1 (2004): 26–41; 1.

10. Indian bhadralok society’s home/world dichotomisation of the private and public spheres was increasingly merging in the twentieth century, as Chatterjee notes, with the onset of a ‘new patriarchy’. Walsh conceptualises this as the ‘domestic world becom[ing] the context for interior explications of national identity’. This phenomenon was articulated in the Bengali context by Rabindranath Tagore in his novel, Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World), and theorised by Homi Bhabha in his essay, ‘The World and the Home’. In it, Bhabha draws from the Freudian concept of the ‘Uncanny’ to argue that the domestic sphere turns ‘unhomely’ as the ‘home does not remain the domain of domestic life, nor does the world simply become its social or historical counterpart. The unhomely is the shock of recognition of the world-in-the-home, the home-in-the-world’: see Rabindranath Tagore, The Home and the World, trans. Surendranath Tagore (London: Penguin, 1985); Partha Chatterjee, ‘The Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question’, in Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History, ed. Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990): 233–53; 244;; Judith E. Walsh, Domesticity in Colonial India: What Women Learned When Men Gave Them Advice (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2004): 28; Homi K. Bhabha, ‘The World and the Home’, Social Text, nos. 31/32 (1992): 141–153; 141.

11. Attia Hosain, ‘Harappa Interview’, 1991, accessed May 13, 2022, http://old.harappa.com/attia/muslimleague.html.

12. Attia Hosain, Sunlight on a Broken Column, Intro. Anita Desai (New Delhi: Penguin, 2009): 4.

13. Ibid., 4–5.

14. Mobeen Hussain, ‘Sunlight on a Broken Column and The Heart Divided as Autobiographically Inspired Realist Texts’, in Sultana’s Sisters: Genre, Gender, and Genealogy in South Asian Muslim Women’s Fiction, ed. Haris Qadeer and P.K. Yasser Arafath (London: Routledge, 2022): 160–76; 161.

15. Hosain, ‘Harappa Interview’.

16. Ibid.

17. Hosain, Sunlight, 14.

18. Ibid., 123.

19. Ibid., 146–47.

20. Ibid., 265.

21. Ibid., 270.

22. Ibid., 270–79.

23. Ibid., 270.

24. Ibid., 319.

25. Ibid., 275.

26. Elizabeth Jackson, Muslim Indian Women Writing in English: Class Privilege, Gender Disadvantage, Minority Status (New York: Peter Lang, 2018): 7.

27. Interview with Geetha Gangadharan, ‘Denying the Otherness: Interview’, in The Fiction of Shashi Deshpande, ed. R.S. Pathak (New Delhi: Creative, 1988): 252–56; 252.

28. Burton, Dwelling in the Archive, 90.

29. Sabir Khan, ‘Memory Work: The Reciprocal Framing of Self and Place in Émigré Autobiographies’, in Memory and Architecture, ed. Eleni Bastéa (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004): 117–39; 126.

30. Burton, Dwelling in the Archive, 11.

31. Ibid., 99, emphasis added.

32. Hosain, Sunlight, 18.

33. Gillian Rose, ‘Women and Everyday Spaces’, in Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993): 36–39; 38.

34. The harem and the zenana, although different, have often been conflated in Western and Oriental discourses on Muslim women’s spatial ontologies. I have included the defence of the harem by Islamic feminist scholars here to highlight a similarity between the two that is their role as facilitators of kinship ties between women and girls.

35. Leila Ahmed, ‘Western Ethnocentrism and Perceptions of the Harem’, Feminist Studies 8, no. 8 (1982): 521–34; 532, https://doi.org/10.2307/3177710.

36. Fatima Mernissi, Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Childhood (New York: Basic Books, 1994): 121.

37. Shahida Lateef, Muslim Women in India: Political and Private Realities, 1890s to 1980s (New Delhi: Zed, 1990): 133.

38. Hosain, Sunlight, 145.

39. Ibid., 104.

40. Ibid., 105.

41. Ibid., 145.

42. Bahloul, Architecture of Memory, 10.

43. Ibid., 4.

44. Hosain, Sunlight, 21, emphasis added.

45. Malashri Lal, The Law of the Threshold: Women Writers in Indian English (New Delhi: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1995): 22.

46. Ibid., 17.

47. Tanvir Sachdev, ‘Voices from the Threshold in Attia Hosain’s Sunlight on a Broken Column’, Zeitschrift für Anglistik und Amerikanistik 66, no. 1 (2018): 65–77, https://doi.org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/10.1515/zaa-2018-0007.

48. Hosain, Sunlight, 132–33.

49. Ibid., 131.

50. Ibid., 133.

51. Sachdev, ‘Voices from the Threshold’, 71.

52. Anuradha Dingwaney Needham, ‘Multiple Forms of (National) Belonging: Attia Hosain’s Sunlight on a Broken Column’, Modern Fiction Studies 39, no. 1 (1993): 93–111; 103.

53. Hosain, Sunlight, 160, emphasis added.

54. Lal, Law of the Threshold, 19.

55. Needham, ‘Multiple Forms’, 102.

56. Lindsey Moore, ‘Before and Beyond the Nation: South Asian and Maghrebi Muslim Women’s Fiction’, in Imagining Muslims in South Asia and the Diaspora: Secularism, Religion, Representations, ed. Claire Chambers and Caroline Herbert (London: Routledge, 2015): 42–56; 48.

57. T. Minh-Ha Trinh, When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics (London: Routledge, 1991): 75.

58. Vrinda Nabar, ‘Fragmenting Nations and Lives: Sunlight on a Broken Column’, in Literature and Nation: Britain and India 1800–1990, ed. Richard Allen and Harish Trivedi (London: Routledge, 2000): 121–37; 137.

59. Hosain, Sunlight, 173.

60. Ibid., 124.

61. Ibid., 128.

62. Ibid., 141–42.

63. Ibid., 142.

64. Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, Real and Imagined Women: Gender, Culture and Postcolonialism (London: Routledge, 1993): 11.

65. Hosain, Sunlight, 191.

66. Ibid., 147.

67. Ibid., 314.

68. Ibid., 315.

69. Ibid.

70. Ibid., 319.

71. Ibid.

72. Ibid., 191.

73. Ibid., 59.

74. Ibid., 58.

75. Ibid., 161–62.

76. Ibid., 162.

77. Ibid., 165.

78. Ibid., 173.

79. Ibid., 275.

80. Ibid., 299.

81. Ibid., 291.

82. Ibid., 319.

83. Kumkum Sangari, Politics of the Possible: Essays on Gender, History, Narrative, Colonial English (New Delhi: Tulika Books, 1999): xxii.

84. Susheila Nasta, ‘Points of Departure: Early Visions of “Home” and “Abroad”’, in Home Truths: Fictions of the South Asian Diaspora in Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002): 15–55; 40.

85. Hosain, Sunlight, 272.

86. Khan, ‘Memory Work’, 121.