ABSTRACT

This article addresses the impact on occupational relations of mediated communication through a sign language interpreter from the perspective of hearing people who do not sign but who work alongside deaf signers in the workplace. Based on a phenomenological analysis of eight semi-structured interviews, findings address the influence of phonocentrism on working practice between deaf and hearing people. In particular, the implications of the inscription of identity and presence through an embodied language are discussed. The consequences of failure to acknowledge the interpreter as a contingent practice for all, not just the deaf person, are examined. The findings have implications for the recognition and promotion of deaf agency and talent in the ‘hearing’ work place and extend understandings of structural influences on workplace discriminations to include those of interpreted communication.

Deaf signers comprise a minority population within every country of the world (Murray, Citation2007). Signed languages are fully grammatical living languages that have no vocal element and are unrelated to the dominant spoken languages of the countries in which they are used, e.g. BSL is not a visual version of English (Sutton-Spence & Woll, Citation1999). Communication between deaf people who sign flows, not just because of shared language but because of a shared sense of identity and culture which extends transnationally; a concept that has been identified as DEAF-DEAF-SAMEFootnote1 (Friedner & Kusters, Citation2014). When deaf people from different nations meet, they are able to interact directly by drawing on their existing knowledge of a signed language to fluidly find a commonality of expression and understanding within a similar visual grammatical structure across different signed languages (Kusters, Spotti, Swanwick, & Tapio, Citation2017; Zeshan, Citation2017; Zeshan & Panda, Citation2018).

When deaf and hearing people (who do not sign) meet, communication is far more challenging. This difficulty is commonly ascribed to the deaf person who is readily regarded as disabled (unable to hear and speak well) and therefore unable to communicate in the way hearing people do (Lane, Citation1999). Regarded instead from a cultural-linguistic perspective, the issue is one of a disparity in understanding between languages and cultures as might be the case in spoken language transactions between different cultural groups. Deaf people creatively exercise agency in utilizing a wide range of ways to make themselves understood to hearing people, for example, iconic gesture, writing down words, pointing (Kusters et al., Citation2017). However, such strategies that are effective for simple transactional purposes (Kusters, Citation2017a, Citation2017b) are not when more in depth communication is required; for example when accessing public services or fulfilling professional roles.

Thus, for many deaf signers, interactions with the hearing, non-signing majority are often predicated on the use of interpreters and translators to navigate events in everyday life, such as consultations with a GP (Major, Citation2013) and employment interviews (Napier, McKee, & Goswell, Citation2018), as well as to execute professional roles in the workplace (Hauser, Finch, & Hauser, Citation2008). Rights of access to sign language interpreters are framed in many nations’ legal structures on grounds of disability, for example in the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Equality Act 2010 in the U.K., rather than in terms of language rights and cultural-linguistic status of deaf people (Haualand, Citation2009).

Although the provision of sign language interpreters is a positive form of access to communication, it could be perceived as problematic for two reasons: (1) the loss of agency for deaf signers in communicatively performing and projecting their identity (self) because an ‘other’ has to make choices about how they are represented (i.e. when they sign, someone else – the interpreter – literally speaks for them); and (2) deaf signers are perceived by hearing non-signers through an ‘other,’ the sign language interpreter, who is more than the arbiter of linguistic content. Interpreters are imbued with powers of representation and portrayal of the person. For example, tone of voice, lexical choices, register and the identity of their interpreter themselves (gender, culture, race etc.) all convey meaning whether explicitly or implicitly. Interpreting practices are not just inter-lingual but also involve the translation of who we are (Gal, Citation2015). Interpreted situations are thus of ontological and epistemological import because the intersubjective experience of knowing the other and the means by which the knowledge of the other is accessed and conveyed is not direct.

These circumstances led us to be concerned about the impact for the person who is deaf of being known in translation Footnote2 for a large part of their daily lives in interactions with the hearing majority. Our work addresses such impact in terms of personal agency, sense of self and role fulfillment. We perceive this question to be both a scholarly and applied problem. In terms of scholarly interest, focusing attention on the experience of being known in translation shifts attention from interpreting practice as linguistic communicative engagement to an examination of its ontological and epistemological connotations specifically in a context where deafness as disability and deafness as cultural-linguistic identity are contested. We address this through the lens of phonocentrism (see below). In terms of its applied interest, strategies utilized both to overcome any potential communication barriers across different languages and to promote intersubjective knowledge of the other, have relevance to improving workplace relations in all interpreted professional contexts as well as of direct import in the training of sign language interpreters.

This article concerns the exploration of one aspect of the phenomenon we have termed ‘the translated Deaf self’. As a working definition, to be refined through research, the phrase refers to the socio-cultural impact for deaf signers of multiple, regular, lifelong experiences of being encountered by others and inter-subjectively known in a translated form i.e. through sign language interpreters. Specifically, we draw on data from hearing non-signers who interact regularly with deaf signers in the workplace. Other aspects of the translated deaf self from different perspectives are addressed in parallel publications (Napier, Oram, Young, & Skinner, Citationin press; Young, Napier, & Oram, Citationin press). We build on the work of La Belle, Booth-Butterfield, and Rittenour (Citation2013), who examined hearing people’s attitudes towards communication with deaf people. They found that participants who perceived certain people in society to have less equal status, and were anxious about meeting other unfamiliar people, had more negative attitudes towards communicating with deaf people; and those who had more contact with deaf people, predominantly because they had enrolled in sign language classes, had more positive attitudes. However, their study did not consider hearing people’s attitudes towards communication with deaf people via a sign language interpreter.

Taking an interdisciplinary stance, drawing on Social Research, Deaf Studies, and Interpreting Studies, this study set out to:

explore hearing colleagues’ experience of professional and working relations with deaf colleagues

explore hearing people’s perceptions of the impact of sign language interpreters and the process of interpretation with respect to how they get to know deaf colleagues and build relationships.

First, we review some of the wider literature on being known in translation, sign language interpreters within occupational settings, and introduce phonocentrism as the theoretical lens through which we will consider the study’s findings.

Literature review

Using interpreters as a persistent not transient experience

The majority of (hearing) people rarely experience being known in translation through an interpreter. Either they are multilingual, able to use one or more languages as the context demands, or they use interpreters for a specific, contextually defined and usually time-bounded purpose, e.g. participation in a multilingual meeting or conference. Interpreters are not typically a fact of everyday life or an aspect of a lifelong experience of interaction with others. Furthermore in changing spoken language situations (such as through migration), hearing people have the capacity to transition to a degree of mastery of a new language to the point at which interpreters are not required. It is possible to learn another spoken language to varying degrees of functional or domain-specific fluency. Deaf signers’ experience is different.

Although deaf signers might have some degree of bilingualism (e.g. in BSL and spoken and/or written English) many may never be fluent users of a spoken language. The physiological elements of being deaf disrupt usual processes of acquiring a spoken language to a greater or lesser extent because of the ways in which hearing the spoken word is impeded, whether during initial processes of language acquisition as an infant or in learning spoken languages as second languages (Marschark, Citation2017; Meier, Citation2016). The requirement for sign language interpreters is, therefore, not a transient one.

Deaf people in the workplace

Deaf people in the workplace is one context where tensions surrounding the contested nature of cultural-linguistic identity, the ascribed meanings and status of sign language interpreters, and their consistent use as part of everyday life, are most readily evidenced.

In the past 25 years there has been a marked rise in deaf people, in the U.K. and in other developed nations, taking on white collar professional roles and middle and senior management posts in workplaces and organizations where hearing speaking people predominate (Schley et al., Citation2011; Schroedel & Geyer, Citation2000). In part this is a result of a rise in educational attainment associated with better access to quality education (Rydberg, Gellerstedt, & Danermark, Citation2011). Such roles require frequent communicative interaction and a high degree of literacy and consequently sign language interpreters in the workplace have become a more frequently recurring condition.

Limited previous research on communication between deaf signers and hearing people in the workplace has largely considered the problem through the lens of best interpreting practices (Hauser et al., Citation2008) including effectiveness in knowledge transmission and engagement (Bristoll, Citation2009) and deaf professionals’ preferences in interpreting practices (Earhart & Hauser, Citation2008; Haug et al., Citation2017). Only one study has specifically focused on how sign language interpreters can contribute to occupational relations between deaf (minority) and hearing (majority) people by exploring how interpreters need to consider themselves as part of a community of practice (Dickinson, Citation2014). A separate strain of research has focused on blended deaf and hearing teams in specialist deaf-related settings such as schools, health providers, and academic departments to uncover cross-cultural and cross-linguistic roots of occupational tensions and/or professional best practices (Baker-Shenk & Kyle, Citation1990; Young, Ackerman, & Kyle, Citation1998, Citation2000). In this work, epistemological concerns have predominately centered on the unequal language status between the signed and spoken/written word and the implications of this for unequal professional status, including whose knowledge claims have power and why (O'Brien & Emery, Citation2013; Sutton-Spence & West, Citation2011; Young & Ackerman, Citation2001).

Hearing people’s sense-making of direct or interpreted encounters with deaf colleagues is predominantly absent from the literature. There are two notable exceptions: (1) Young et al. (Citation1998) carried out a qualitative interview and focus group study of deaf/hearing relations in 3 specialist BSL-medium health and educational settings where deaf people primarily worked in para-professional roles alongside hearing qualified professionals. They traced the negative impact on hearing professionals’ self-confidence and role performance in circumstances where their linguistic competence in a signed language did not match their professional competence, but showed how the exact opposite was true in the case of their deaf colleagues. (2) Napier (Citation2011) held focus groups with sign language interpreters, deaf signers and hearing professionals who had experience working with sign language interpreters to examine their attitudes towards sign language interpreters and interpreting generally. Overall, each participant group agreed on the fundamental aspects of interpreting, in relation to the need for interpreters to be linguistically competent, professional, adaptable and considerate of the context and consumer needs. However, deaf people and interpreters prioritized their own individual needs to ensure successful communication whereas the hearing participants were concerned with the needs of all participants in the interaction, including the interpreters. Neither of these studies, however, explored the perceptions of hearing people about knowing their deaf colleagues through interpreters.

A phonocentric lens

Our initial thinking in embarking on this study was informed by the concept of phonocentrism. Originally coined by Derrida (Citation1976) it refers to the privileging of sound and the spoken word in relation to being. Through, quite literally, hearing oneself speak, hearing speaking peoples are, recognize, and simultaneously convey, their own presence in the world. Hearing is both interior and exterior confirmation of existence and presentation of self.

The system of ‘hearing (understanding) -oneself-speak’ through the phonic substance – which presents itself as the nonexterior, nonmundane, therefore nonempirical or noncontingent signifier – has necessarily dominated the history of the world … . (Derrida, Citation1976/Citation1979, p. 78)

Derrida’s work did not consider the alternative ontological orientation of visual peoples who use signed languages (Batterbury, Ladd, & Gulliver, Citation2007) and to whom the same argument might equally apply, be it differently. One may not hear oneself and through that know of and exert one’s existence, but instead it is language and the body that occlude because the body is language and language is the body (in-corp-orated; through the body spoken). This presence is rendered both physical and metaphysical through the corporeal self being simultaneously the origin, the reference and the expression of language and being. In Derrida’s terms, language is ‘traced’ (Spivak, Citation1976/Citation1979) on the body in the way in which signed languages operate in space and movement and it is traced (has its spoor) in the sense of first origin and architecture of the human body.

However, interpretation by its very nature disrupts the simultaneity of speech-language-the person that Derrida (Citation1976) identifies as the site of presence. This is because it introduces a third element, an additional person, losing the simultaneity of expression and being, and introducing an alternative epistemic pathway. Signed language interpretation renders the situation even more complex because not only is the relationship between language and the person disrupted but a concept of language as synonymous with speech is disrupted too. Communication is both indirect and bimodal. Through speaking for ourselves, or indeed signing for ourselves, individuals are made present (present-ed through that process). Through speaking or signing through another an individual is, by contrast, (re)presented (as different, abstracted and at one remove). In exploring the phenomenon of ‘the translated deaf self’ and its potential implications, these ideas centered around phonocentrism, signers and interpretation were central to our thinking and are reflected in our discussion of the findings to follow.

Method

Methodological approach

The study reported here is one of several concerned with seeking to explore, delineate and understand what we have termed ‘the translated deaf self’; a phrase we have used to refer to the socio-cultural impact for deaf signers of multiple, regular, lifelong experiences of being encountered by others and inter-subjectively known in a translated form, i.e. through sign language interpreters. Although this working definition of the phenomenon of ‘the translated deaf self’ was created at the start of the project, we entered the field with the open intention that it was only through the analysis of the lived experience of a range of relevant individuals in specified contexts that it would be possible to start to scope its parameters and work toward a more refined understanding of its meaning(s) and implications. In this sense we were ‘ … interested in the phenomenon being experienced and not so much in the particular individual who is experiencing the phenomenon’ (Giorgi, Citation2006, p. 318).

A phenomeonological approach within the interpretative/hermeneutic tradition underpinned our research design (van Manen, Citation1990). This tradition is interested in how people interpret and made sense of their experiences and treat the experiences of individuals and the meaning they make of them as valid in their own right regardless of any reference to objective reality. Nonetheless, after Merleau-Ponty (Citation1964) we adopt the position that the experiencer is not necessarily the best arbitrator of the meaning of their own experience. This is important in opening up the status of an individual’s account of their lived experience to the analysis of the influences and contexts that might have shaped the meaning they are making of it. These influences, sometimes referred to as fore-knowledge, are not confined to the intersubjective and contextual features of an individual’s biography and daily life but also encompass the socio-cultural discourse, in the Foucauldian tradition, to which an individual or group may be subject (Foucault, Citation1982). This position underpins our approach to data management and thematic analysis discussed below.

Recruitment and sample

In the U.K. context it is rare to find organizations where several deaf people work outside of those that are deaf-led specialist organizations, such as those focused on the deaf community itself. We required a setting where there was a well-established presence of multiple deaf signers within an otherwise non-deaf specialist organization and where there was a population of hearing people who had experience working alongside deaf colleagues over time, but did not necessarily use BSL themselves. All participants were drawn from a single large organization in the U.K. with multiple departments where several deaf signers worked in differing roles. This was a professional rather than technical or retail environment; deaf people made up approximately 5% of the workforce of around 220. The activity of the organization was not focused on deafness or disability. Further details of the setting are not being provided because of the potential to identify those deaf staff that the hearing participants mention in the data.

Participants were purposefully selected and personal invitations sent to 12 hearing people known to have regular contact with deaf colleagues in varying capacities within the work environment. Eight people responded positively. Although this may be regarded as a small sample from which to draw any firm inferences we argue that it is justified in this case. First because of the difficulty in identifying a suitable setting, as discussed above, this can be regarded as a rare sample. Second, the overall focus of the study was to explore a phenomenon rather than analyze specific individuals’ experiences. We make no claims for saturation as a criterion by which to judge whether the number of interviews was sufficient or valid. Rather, after Denzin (Citation2012) we argue that the number of participant interviews may be of less relevance than number of ‘instances’ of the phenomenon of interest contained within the interview. Each instance of a phenomenon is ‘an occurrence which evidences the operation of a set of cultural understandings currently available for use by cultural members’ (Denzin, Citation2012 in Baker & Edwards, Citation2013, p. 23). Our sample yielded enough such instances from which to begin to draw conclusions relevant to our phenomenon of interest without making claims that those definitively described that phenomenon in all of its aspects.

Participant characteristics

No participant had prior experience of working with a deaf person before joining this organization and none had deaf familial or social connections. For all participants, their work-based experiences with deaf colleagues were their first sustained experiences of interacting with deaf people. In the sense that they had nothing to compare with, they were naive informants drawing only on their direct knowledge in one environment. This group, therefore, might not be considered a typical general public sample. They are, however, a case study sample of hearing people’s attitudes that might grow from the direct experience of regular communication and interaction with deaf colleagues where none has existed previously. Further details of participant characteristics are given in and all names are pseudonyms.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Participants’ contact with deaf people ranged from occasional indirect contact to frequent weekly contact. For some, contact was task-centered and functional (e.g. organizing appointments, responding to practical questions), for others it consisted of complex, joint working including being on the same professional team as a deaf colleague. Participants’ experience of working contact with deaf colleagues ranged from one to five years. Sign language interpreters were frequent visitors to the organization and a range of interpreters were seen in many work-related contexts but there was no in-house interpreter employed. The deaf colleagues who participants encountered were, in all but two instances, their peers or played more senior roles in the organization.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews in spoken English; the average interview time was 45 minutes (minimum 30 minutes, maximum one hour). Participants were provided with the questions in advance so they could consider their responses. The interviews were all carried out by the same research team member who was a hearing signer [author Young] for sake of consistency.

Approach to analysis

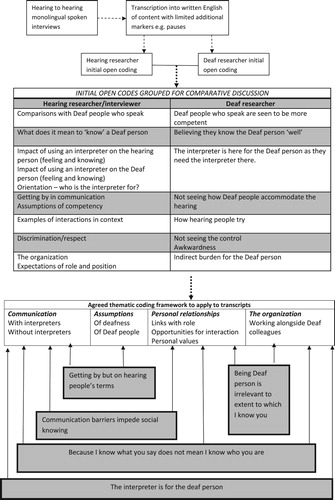

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a registered research transcription service and names and identifiable references removed at this point. Authors Young and Oram independently read the transcripts and each generated initial open coding categories. This process was intended to introduce an element of critical positionality at an early stage into the analysis. This is because author Oram is a researcher who is a deaf signer and therefore her identification of key conceptual issues will be influenced by her lifelong experience of living and working alongside hearing people as a deaf person whereas author Young has an opposite experience of being a member of the hearing majority who has nearly 30 years’ experience of working alongside deaf colleagues.

In line with the interpretative phenomenological approach to the study, Authors Young and Oram engaged in a series of reflexive discussions (in BSL) concerning the initial open codes. They shared their views on the influences of their identity and prior experience that they judged had led them to their initial interpretations and data coding. This self-reflective, interpretative, discursive process was in line with the so-called double hermeneutic at the heart of an interpretive phenomenological approach to thematic analysis (van Manen, Citation1990). It was used both as the means of refining the initial open coding framework and as part of the interpretative analysis of the data (Ho, Chiang, & Leung, Citation2017). For example, the code ‘deaf people who speak’ was identified by each of the researchers, but for the hearing person coding this theme was seen as primarily referring to participants’ preferences for ease of communication with a deaf colleague. For the deaf person coding, this theme embodied a judgement she saw in the participants’ words that somehow those deaf colleagues who spoke were ‘better’ in the sense of more able, regardless of their seniority in the organization. She reflected that she found this shocking but it tuned in to her personal experience of how society invests the spoken word with power. The hearing researcher reflected she did not feel surprised by this aspect of data because in her experience hearing people saw speaking as an achievement for deaf people because it showed the ‘disability’ had been ‘overcome’.

Ethics

The study was approved by the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee. Participants were required to give informed consent and were free to withdraw from the interview at any time and to withdraw their data up to the point of the formal data analysis.

Results

Results are presented in 5 themes which emerged from the data (). They encompass structurally defined expectations of the boundaries of knowledge about a colleague, the disruption of informal and social knowledge in human relations, the disjointed experience of understanding communication but not understanding the person, the role of the interpreter in constructions of agency and power between hearing and deaf people, and normative ‘hearing’ behaviors. Each section is headed by a heuristic, rather than a direct quote, to capture the essence of the subject matter.

Being a deaf person is irrelevant to judgments about the extent to which I know you

This theme highlights that participants did not necessarily attribute the quality of their overall relationships with deaf colleagues to any perceived communication barriers between deaf and hearing people or the fact their colleague was deaf. For four people, their judgements about how well they knew deaf colleagues were tempered by their expectations of how well they thought they should know other people in general, given their role and that of the other. For example, one participant occupying a junior administrative role explained that her expectation was to be on good terms with all colleagues, be that in a polite and socially superficial way, because low-level rapport oiled the wheels of whatever kind of task she was required to do for someone else. The only difference she identified in terms of how she worked with deaf colleagues was that it could take longer to achieve that level of informal rapport because it had to be built up through email or was dependent on when an interpreter might be around.

I've got to know them … I think it's difficult in the first instance to sort of develop that [rapport], but because of work-related sort of emails, I always try and put something friendly in it, so they will put something friendly back and it's built up. (Samantha)

Communication barriers impede social knowing

For this theme, the central issue was that even if the participants wanted to get to know their deaf colleagues outside of their role-based interactions, communication barriers made it more difficult than would be the case with hearing colleagues. However, this lack of access to knowing someone in a more rounded way did not just have social consequences, it had direct occupational effects too.

Five participants emphasized the importance of getting to know colleagues socially in role relations in the workplace. For them this was much harder to do with deaf colleagues than with hearing colleagues and that was due to communication, even if interpreters were present. For example, one participant explained that in his view an important element of working well as a team was getting to know your colleagues socially. He felt frustrated that he could not do this as easily as he could with hearing peers because the opportunities for informal chats were far fewer. He needed an interpreter to open up a discussion about what did you do during the weekend for example, or to learn about someone’s life outside of work, at which point it ceased to feel informal or spontaneous.

For others, not possessing the communication skills to have a social chat at work was seen as a problem because it could mean that they treated their deaf colleagues differently than their hearing ones, regardless of role considerations. One participant described at length the situation of the casual contact in the lift which exemplified this problem for her. Not to have the personal and social relationship she would wish for, even in passing, was to her totally unsatisfactory:

The times when I feel awkward is in the lifts, because I want to communicate to them … and you just say hello and they know you are just saying hello and they can acknowledge you, but it's very difficult to enter into any kind of conversation … If they can speak they’ll say something back to you, but that's when it's awkward because you just don't want to embarrass them and you don't want to behave any differently with them, than you might do anybody else … it's like the double whammy, double jeopardy in a sense … they are just like you and I really – why would you treat them any differently – but it is awkward. (Christine)

Another participant who had multiple daily interactions with deaf colleagues because of her job, but not in any depth, was similarly focussed on the importance of treating someone else as you would wish to be treated. If communication created impediments to achieving that goal she was not happy and felt she knew her deaf colleagues less well than others. She said she was ‘uncomfortable,’ not because it was detrimental to doing her job well, but because it offended her personal values of treating everyone the same. In principle she made no distinction between her relationships with deaf and hearing colleagues, in practice she recognized there were real restrictions she could not overcome.

Because I know what you say does not mean I know who you are

This theme highlights the fact that even if communication is accessible via an interpreter, this does not ensure satisfactory inter-subjective relations. For many participants there was a trade-off between content knowledge gained through fully interpreted usually formal communication, and knowledge of the person usually gained via poor communication in informal activity. This distinction between content and person knowledge was one that most had never previously experienced.

All participants acknowledged in different ways that interpreters were important in getting to know their deaf colleagues because this was the means to knowing what they ‘said’. However, participants made a distinction between this kind of knowledge based on the content of communication and knowing a person in the sense of their personality and character. This kind of knowledge of the other was harder to get through interpreted dialogue and in fact could be obscured by it.

For example, two participants stressed the importance of understanding the content and the intent of any conversation by simultaneously paying attention to both the interpreted message they were hearing and the deaf person who was signing. Even if the message was understood indirectly (via the interpreter’s voice), it was being conveyed directly and they felt there was much to understand from how someone was signing, even if as hearing person you could not actually understand them. This participant, for example, who worked directly and on complex projects with a deaf colleague, was clear that you cannot just listen through an interpreter in order to understand:

I think with BSL you’ve very much got to look at the behaviour and the gestures of the person. I mean, one of the particular people that I’ve been working with … it’s what the emotions are and what the passion is behind that as well, which you can’t get from an interpreter to the same extent as from the person that’s signing [the interpreter]. (Carmel)

And the way somebody expresses themselves has to be caught by their actions and then there's a delay and then you hear what that meant so there's a bit of a disconnect … maybe they are uncertain or maybe they are very certain and then later you have to wait for the message to come through and then understand what that … how that's been said. (Roderick)

This emphasis on knowing the person was also present in how two other participants talked about the paradox they experienced in comparing an interpreted and a non-interpreted interaction with deaf colleagues. On the one hand, through an interpreter they felt they knew far more of the details and nuances of what a deaf colleague was saying but at the cost of not really forging a relationship with the person who was deaf. On the other hand, when occasions arose that they worked directly with a deaf person on a task and there was no interpreter, they appreciated that communication was far more problematic and less expansive, but they felt they really got to know the person for the first time. One participant described a shared task that changed how he thought about a particular deaf colleague with whom he has had in the past far more detailed and complex interactions through an interpreter:

At one time anyway I’ve helped [name] with moving shelves up and down in the cupboards, and you know, just doing that through kind of gestures and you kind of get more of a personal connection with that than you would do with … I guess the interpreter seems a bit more impersonal, you know? (Martin)

Another participant who had the longest experience of work-based contact with deaf colleagues said she could tell now when there was not a good ‘connectedness’ between her deaf colleague and the interpreter. For her it was not so much that the conversation did not flow but that she was not hearing her colleague’s personality in the tone of the interpreter’s voice. Another speculated on how someone could know whether they were being well represented through the interpreter’s voice if they could not hear it? Another felt she was not really sure if an interpreter was able to catch fully and convey the personality of a deaf person they were voicing; for her it was something she had pondered before and had no real answer to.

For another, the problem lay in him wondering whether he was missing something about his colleague because of how she was being interpreted.

… again it’s that bit of a frustration that it’s through an interpreter, because you lose a bit of that personal connection. I have sometimes wondered quite how the member of staff feels because that’s not always expressed through the expressions, body language, et cetera, of the interpreter. So yes, I’ve kind of wondered in that respect of if I’m missing something. (Roderick)

The same point was made in reverse by a different participant who had noticed how her deaf colleagues could be ‘masked’ as a result of the interpreter being required. She commented:

I think that most people in the public don't get as far as thinking about the personality [of the deaf person], and that kind of focus is probably on the interpreter and what's that person doing and, oh, this person must have a problem … and they would obviously know they are deaf but I think for some people they associate deafness with some other deficit. (Fiona)

The interpreter is for the other

This theme focuses on the fact that the interpreters were clearly perceived as being ‘for’ the deaf person rather than all parties in a communicative exchange. It reflects an underlying assumption of the disability of the deaf person for whom reasonable adjustments are required rather than a framing of the work situation as one that is essentially inter-cultural and bilingual for hearing people too.

It is striking in all of these different reflections on the impact of an interpreter on the representation of the deaf person there was very little consideration of the same issues the other way round. To what extent is a hearing person unknowable or masked because they have to use an interpreter to communicate with a deaf colleague? Participants were prompted to consider this explicitly if they did not mention it naturally. Most had not given this any thought but found it interesting to think about further. One was able to give a specific example where, on reflection, he could see that there might be a problem for him too; it was an uneasy feeling and he had not previously considered if that was perhaps how his deaf colleagues might feel too.

I guess it feels a bit unempowering [sic], you know, because when I’m used to being able to sort of control the conversation and directly interact with someone, it does kind of … So it’s a bit disorientating in that it takes away your ability to express yourself quite as much as you would in other contexts. You do wonder if the … interpreter’s exactly saying how you mean something to come across. (Martin)

Getting by but on hearing people’s terms

This final theme emphasizes the dominant thinking of participants that they engaged in communication with their deaf colleagues according to hearing normative behaviors. Everyone who mentioned face to face encounters without an interpreter described their personal discomfort being greater than when communicating with an interpreter.

I'm not going to lie. Sometimes I feel stupid, like I should be able to hear what someone is trying to communicate to me and I think you do get hypersensitive … oh, why did I not get that?’ (Melissa)

Discussion

As one element of a broader research project seeking to explore a phenomenon we have termed ‘the translated deaf self’, this study has focused on the implications for deaf people of being known in translation through the eyes of the ontological other, i.e. hearing people. In addressing this aspect we have grounded our work in Derrida’s (Citation1976) critique of phonocentrism because we wanted to interrogate how hearing people made sense of a fundamental disruption to their usual ways of interacting and consequently what the implications might be for the deaf person who was being encountered in translation. In such encounters, from hearing people’s perspectives, the assumed natural connection between voice, language and the self is severed. It is severed both because the embodied voice that is heard (of the interpreter) does not emanate from the embodied person from whom the communication originated (the signing deaf person). It is also severed because language and speech are no longer synonymous and the relationship between the two becomes problematized in interactions between deaf and hearing people.

As Anglin-Jaffe (Citation2011) comments: ‘to be able to “hear oneself speak” is a moment of ontological significance, the lack of which is deeply challenging to fundamental ideas about language and identity’ (p. 31). In our work, on the ‘translated deaf self’ we have pushed this Derridian consideration further by asking instead questions about the ontological significance for deaf people of being heard to speak through another (rather than not hearing oneself speak), i.e. through a sign language interpreter. Hearing colleagues’ thoughts about their working relationships with deaf people, whether with or without an interpreter, is the medium through which we examine this issue.

From this theoretical perspective, it is striking how hearing participants placed great store by the desire to know the person who is deaf. The presence and/or absence of a sign language interpreter could be construed as either hindering or facilitating this desire, dependent on context and complexity of task. Expectations of what the knowledge of the person might consist (formally superficial or informally social) were further influenced by role expectations, personal values and context. However, regardless of these differences, the deaf self who was to be known is present in the data as an essentialist one, reached or masked by the presence of an interpreter in the eyes of participants. It is not a self primarily known through what a deaf colleague might say (sign) or do; the performative self who has agency (Butler, Citation2010). Instead, the selfhood of the deaf person is seen as set apart, something to be sought out beyond and despite the confusions and difficulties of communication.

Perhaps this orientation is an unconscious result of seeking to apply to deaf people who sign the approach of ‘see the person not the disability’ (EEA, Citation2015; SCOPE, Citation2015) or ‘look past not at disability’ (Helbig, Citation2014). However, from many deaf people’s perspectives such adages are irrelevant because the person who is deaf cannot be separated from the identity inscribed through their embodied language use (Kusters & De Meulder, Citation2013; Napier & Leeson, Citation2016; Young & Temple, Citation2014), thus ontologically reconnecting language and the body (but not voice) as the site of presence and the assertion of being. By hearing colleagues seeking to see past the technology of the interpreter, or the socially awkward confusions of direct communication, they are in fact indirectly reproducing that sense of distance that they are seeking to resist. They are structuring the deaf person as someone to be known separate from how they are known (through their embodied language). It is also a striving that our participants did not readily connect the other way round with the deaf person’s experience – that the hearing person may be unknown and unknowable because she speaks. This absence from our participants’ discussion is telling of an internalized hegemonic discourse in which it is rare for hearing people, in the context of deaf people, to problematize the dominance afforded by speech in terms of agency and power in the workplace, regardless of role or seniority.

The tendency of hearing people to see the necessity, ownership, and relevance of the interpreter ‘for’ the deaf person rather than for all (Napier et al., Citation2018), paradoxically renders the means of communicative access as a means of reinforcement of inequalities created through power and knowledge. However, the subjectivity (Foucault, Citation1982) of the hearing person also is contingent and (re)produced through the interpreter, yet this was barely recognized in our study. The lack of recognition of this mutual requirement for communication illustrates an implicit and occupationally situated power differential that locates need with the deaf and normalcy with the hearing. This is even more striking given that in most cases deaf colleagues in this study held equivalent or more senior posts than the majority of hearing people who were interviewed.

Furthermore, everyday attribution of the interpreter for deaf people to be able to communicate with others transforms interpreters into a signifier of disability because of their personalization to one kind of colleague (who is deaf). Recognition that all parties were working with an interpreter, rather than the interpreter being used by deaf people would require a strong orientation to deaf people’s cultural-linguistic identity because it would enable an equivalent recognition of all concerned as different language users. What perpetuates the possibility of the individualization of the interpreter to a deaf person is fundamentally a deeply embedded social discourse that does not recognize the equivalence of signed and spoken languages (Batterbury et al., Citation2007; Crasborn, Citation2010). Such unthinking ontological orientation to the dominance of the phonic in language is described by Derrida as ‘the most original and powerful ethnocentrism’ (Citation1976/Citation1979, p. 70).

However, not all encounters between deaf and hearing people are necessarily mediated ones through another’s voice. Our data also addressed a different kind of ontological disruption. Namely, from hearing people’s point of view, when the modality of language (spoken and heard) cannot be relied upon as sufficient to know and understand the other whose embodied presence is nonetheless being conveyed through language directed to them. Participants did indeed reflect on their own discomfort in such encounters and/or enjoyed moments when they felt they could communicate regardless, e.g. through gestures. What was not recognized was the extent to which deaf colleagues might be making deliberate multimodal communicative choices about how to modify their interactions with hearing people to give them the best possible opportunity to directly understand without the assistance of an interpreter. It is a form of relational communicative adaptation that has been the topic of a small amount of linguistics research. Drawing on pragmatics, Communication Accommodation Theory (e.g. Giles, Coupland, & Coupland, Citation1991; Sanders & Rodriguez, Citation2014) has addressed the functions of such adaptation and their relational gains, and applied sign linguists have examined direct communicative accommodations between deaf signers (Keating & Mirus, Citation2003), or via sign language interpreters (Napier, Citation2013). However, our study was concerned with the significance of the absence of recognition of these processes in terms of how deaf people are perceived and their working relations with hearing people.

This absence occurred despite participants having first-hand experience over time of two kinds of conditions which they could contrast: interactions with deaf colleagues with an interpreter and without an interpreter. They were able to recognize losses and gains in both, comforts and discomforts. One communicative condition was not necessarily superior to the other in terms of the satisfaction they experienced from the interaction. Nobody said, for example, that it was easier for them to work with a deaf person through an interpreter or easier without – it was just different. This sort of self-recognition, evidenced in how participants described their experiences, is important because it is the first step toward moving away from believing that the presence of an interpreter will automatically resolve communication or access issues between hearing and deaf people: ‘an illusion of inclusion’ (Russell & Winston, Citation2014); or that an interpreter is a sufficient adaptation to enable or ensure the equal participation of deaf and hearing people in the workplace (Foster & MacLeod, Citation2003). These are both common responses in occupational contexts that scholars have identified as not just unhelpful but active barriers to the progression of deaf people at work (De Meulder & Haualand, submitted). If the majority (hearing) believe that communication barriers are overcome then there will be little attention to the implicit relational barriers that nonetheless exist. Instead in our data we saw participants who could feel these barriers in their comments on the difficulties in socially knowing a deaf colleague for example, and its implications for effectively working together.

Practical implications

There are several practical, applied implications from our findings for workplaces where deaf and hearing people interact. From policy and training perspectives, reinforcing that interpreters’ role and function is to mediate and enable effective communication for all co-workers, rather than personalizing their presence to the deaf person, would help re-orientate workplace relationships. Deaf and hearing people should be regarded as equivalent but alternative language users. This shift is vital if a rights-based equalities discourse is to replace a disability adaptation discourse in everyday decision making, social relations and role relations within overall occupational structures. It would also be helpful for all colleagues, whether deaf or hearing, to understand that interpreters do not solve communication problems in any absolute sense. Open dialogue about the role of interpreters would support more effective working practices because it would decouple any workplace problems from the identity of a colleague as deaf or hearing, and instead focus attention on shared communication goals in shared working practices.

The element of getting to know a deaf person socially remains, however, an intractable problem in many workplaces because it is so dependent on informal interactions which often do not happen either because an interpreter is not around, or the quality of communication between deaf and hearing colleagues (whether signed or spoken) is not enough to engage in a level deeper than pleasantries (Dickinson, Citation2014). This matters because it is through incidental, informal dialogue about an organization as well as about people within it that all of us gain additional helpful clues about the most effective way to achieve a goal (social and cultural capital) and/or to enjoy the workplace and feel part of it. ‘Deaf people are the last to know’ is a common refrain derived from other studies (Trowler & Turner, Citation2002; Young et al., Citation1998, Citation2000). How this effect might be offset so a deaf worker is not disadvantaged by not being ‘in the know’ and therefore less likely to fit in or to compete in the workplace remains an important challenge.

The relational aspects of communication across languages also emerged as significant in our data with some helpful pointers to simple strategies that, while not solving communication problems, demonstrate a positive relational attitude which was of itself helpful in working relations. Examples include deliberately adding social information to work emails, the use of emoticons, the strength of maintaining eye contact with the person signing even if the message was coming from the voice of the interpreter, a conscious awareness to attempt small talk in informal spaces and a degree of shared humor implicit or explicit between deaf and hearing individuals. Such small, essentially pragmatic adjustments in conversation, are graspable, practical, and of relevance in spoken language as well as cross community dialogue.

Conclusion

According to Kusters and De Meulder (Citation2013, p. 431), people are ‘overpowered by societal structures that are not produced by them or for them, and … produce their own, different spaces, authoring their own ontologies and epistemologies,’ which leads to a form of deaf essentialism defined by ‘the deaf experience,’ which is directly bound up in the use of sign language as a part of identity (cf. Ladd, Citation2003). However as our data have illustrated, sign language is not just a means to the inscription of identity; it is constitutive of presence, just as the spoken word is for hearing people. Yet the necessity of interpretation in most aspects of deaf people’s lives in their interactions with hearing people disrupts the ability to recognize this equality. Furthermore the technology of the interpreter, when combined with a context of assumed phonocentric primacy, can work to reproduce an inequality of person, not just of language. Recognition of these processes is a first step to their remediation and an essential one given the greater numbers of deaf people now entering the workplace and in a wider range of roles than ever before.

Acknowledgements

We thank the interview participants for their frankness and trust. In particular, we acknowledge one of them who, between taking part in this study and the work being published, sadly passed away.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Alys Young http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8551-5078

Jemina Napier http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6283-5810

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We follow international conventions in capitalizing phrases that are transliterations of the signed phrase.

2. We use the term translation in the broadest conceptual sense, in relation to the process of translating between two languages and cultures in different modalities, whether that be through the process of written or signed text-to-text edited translation, or via spoken or signed live interpreting (Munday, Citation2013).

References

- Anglin-Jaffe, H. (2011). Sign, play and disruption: Derridean theory and sign language. Culture, Theory and Critique, 52(1), 29–44. doi: 10.1080/14735784.2011.621665

- Baker, S. E., & Edwards, R. (2013). How many qualitative interviews is enough? National Centre for Research Methods. Retrieved from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf

- Baker-Shenk, C., & Kyle, J. (1990). Research with deaf people: Issues and conflicts. Disability, Handicap and Society, 5(1), 65–75. doi: 10.1080/02674649066780051

- Batterbury, S., Ladd, P., & Gulliver, M. (2007). Sign language peoples as indigenous minorities: Implications for research and policy. Environment and Planning, 39(12), 2899–2915. doi: 10.1068/a388

- Bauman, D. (2008). Listening to phonocentrism with deaf eyes: Derrida’s mute philosophy of (sign) language. Essays in Philosophy, 9(1). Article 2. Retrieved from: http://commons.pacificu.edu/eip/vol9/iss1/2

- Bristoll, S. (2009). But we booked an interpreter! The glass ceiling and deaf people: Do interpreting practices contribute? In L. Leeson, S. Wurm, & M. Vermeerbergen (Eds.), Signed language interpreting: Preparation, practice and performance (pp. 117–140). Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Butler, J. (2010). Performative agency. Journal of Cultural Economy, 3(2), 147–161. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2010.494117

- Corker, M. (1997). Deaf and disabled or deafness disabled. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Crasborn, O. (2010). What does “informed consent” mean in the internet age? Publishing sign language corpora as open content. Sign Language Studies, 10(2), 276–290. doi: 10.1353/sls.0.0044

- De Meulder, M., & Haualand, H. (Submitted). The illusion of inclusion? Rethinking signed language interpreting as a social institution.

- Denzin, N. (2012). How many interviews? In S. E. Baker & R. Edwards (Eds.), How many qualitative interviews is enough? Expert voices and early career reflections on sampling and cases in qualitative research (pp. 23–24). NCRM. Retrieved from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/.

- Derrida, J. (1976/1979). Of grammatology ( G. Spivak, Trans.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Dickinson, J. (2014). Sign language interpreting in the workplace. Coleford: Douglas McLean.

- Earhart, A., & Hauser, A. (2008). The other side of the curtain. In P. Hauser, K. Finch, & A. Hauser (Eds.), Deaf professionals and designated interpreters: A new paradigm (pp. 143–164). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- EEA. (2015). The I am here project. Retrieved from http://eeagrants.org/News/2015/See-the-person-not-the-disability#story

- Foster, S., & MacLeod, J. (2003). Deaf people at work: Assessment of communication among deaf and hearing persons in work settings. International Journal of Audiology, 42, S128–S139. doi: 10.3109/14992020309074634

- Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. doi: 10.1086/448181

- Friedner, M., & Kusters, A. (2014). On the possibilities and limits of “DEAF DEAF SAME”: Tourism and empowerment camps in Adamorobe (Ghana), Bangalore and Mumbai (India). Disability Studies Quarterly, 34(3). Retrieved from http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/4246/3649 doi: 10.18061/dsq.v34i3.4246

- Gal, S. (2015). Politics of translation. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44, 225–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-013806

- Giles, H., Coupland, N., & Coupland, J. (1991). Accommodation theory: Communication, context and consequence. In H. Giles, N. Coupland, & J. Coupland (Eds.), Contexts of accommodation (pp. 1–68). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Giorgi, A. (2006). Concerning variations in the application of the phenomenological method. The Humanistic Psychologist, 34(4), 305–319. doi: 10.1207/s15473333thp3404_2

- Haualand, H. (2009). Sign language interpreting: A human rights issue. International Journal of Interpreter Education, 1, 95–110.

- Haug, T., Bontempo, K., Leeson, L., Napier, J., Nicodemus, B., Van den Bogaerde, B., & Vermeerbergen, M. (2017). Deaf leaders’ strategies for working with signed language interpreters: An examination across seven countries. Across Languages & Cultures, 18(1), 107–131. doi: 10.1556/084.2017.18.1.5

- Hauser, P., Finch, K., & Hauser, A. (Eds.). (2008). Deaf professionals and designated interpreters: A new paradigm. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Helbig, K. (2014, May 28). Look past, not at, disability. New Internationalist Magazine. Retrieved from https://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2014/05/28/disability-awkwardness/

- Ho, K. H. M., Chiang, V. C. L., & Leung, D. (2017). Hermeneutic phenomenological analysis: The ‘possibility’ beyond ‘actuality’ in thematic analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1757–1766. doi: 10.1111/jan.13255

- Keating, E., & Mirus, G. (2003). American sign language in virtual space: Interactions between deaf users of computer-mediated video communication and the impact of technology on language practices. Language in Society, 32, 693–714. doi: 10.1017/S0047404503325047

- Kusters, A. (2017a). Gesture-based customer interactions: Deaf and Hearing Mumbaikars’ Multilmodal and metrolingual practices. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(3), 283–302. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2017.1315811

- Kusters, A. (2017b). Deaf and hearing signers’ multimodal and translingual practices. Applied Linguistics Review. doi:10.1515/applirev-2017-0086.

- Kusters, A., & De Meulder, M. (2013). Understanding deafhood: In search of its meanings. American Annals of the Deaf, 158(5), 428–438. doi: 10.1353/aad.2013.0004

- Kusters, A., Spotti, M., Swanwick, R., & Tapio, E. (2017). Beyond languages, beyond modalities: Transforming the study of semiotic repertoires. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(3), 219–232. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2017.1321651

- La Belle, S., Booth-Butterfield, M., & Rittenour, C. E. (2013). Attitudes toward profoundly hearing impaired and deaf individuals: Links with intergroup anxiety, social dominance orientation, and contact. Western Journal of Communication, 77(4), 489–506. doi: 10.1080/10570314.2013.779017

- Ladd, P. (2003). Understanding deaf culture: In search of deafhood. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Lane, H. (1999). The mask of benevolence. Washington, DC: Dawn Sign Press.

- Major, G. (2013). Healthcare interpreting as relational practice (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Macquarie University.

- Marschark, M. (2017). Raising and educating a deaf child (3rd Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford.

- Meier, R. P. (2016). Sign language acquisition. Oxford Handbooks. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199935345-e-19

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). Phenomenology and the sciences of man. In J. Edie (Ed.), The Primacy of Perception (J. Wild, Trans., pp. 43–95). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press (French original, 1961).

- Munday, J. (2013). Introducing translation studies: Theories and applications (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Murray, J. (2007). Coequality and transnational studies: Understanding deaf lives. In H.-D. L. Baumann (Ed.), Open your eyes: Deaf studies talking. London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Napier, J. (2011). It's not what they say but the way they say it. A content analysis of interpreter and consumer perceptions of signed language interpreting in Australia. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 207, 59–87.

- Napier, J. (2013). “You get that vibe”: A pragmatic analysis of clarification and communicative accommodation in legal video remote interpreting. In L. Meurant, A. Sinte, A. M, V. Herreweghe, & M. Vermeerbergen (Eds.), Sign language research uses and practices: Crossing views on theoretical and applied sign language linguistics (pp. 85–110). Nijmegen: De Gruyter Mouton and Ishara Press.

- Napier, J., & Leeson, L. (2016). Sign language in action. London: Palgrave.

- Napier, J., McKee, R., & Goswell, D. (2018). Sign language interpreting: Theory and practice (3rd ed.). Sydney: Federation Press.

- Napier, J., Oram, R., Young, A., & Skinner, R. (in press). When I speak people look at me: British deaf signers' use of bimodal translanguaging strategies and the representation of identities. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts.

- O'Brien, D., & Emery, S. (2013). The role of the intellectual in minority group studies: Reflections on deaf studies in social and political contexts. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(1), 27–36. doi: 10.1177/1077800413508533

- Russell, D., & Winston, B. (2014). Tapping into the interpreting process: Using participant reports to inform the interpreting process in educational settings. International Journal of Translation & Interpreting Research, 6(1), 102–127. doi: 10.12807/ti.106201.2014.a06

- Rydberg, E., Gellerstedt, L. C., & Danermark, B. (2011). Deaf people's employment and workplaces: Similarities and differences in comparison with a reference population. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 13(4), 327–345. doi: 10.1080/15017419.2010.507375

- Sanders, G. T., & Rodriguez, S. R. (2014). Connecting visual communicators with an auditory world: Exploring communication accommodation processes in d/deaf-hearing interactions. Iowa Journal of Communication, 46(1), 33–51.

- Schley, S., Walter, G. W., Weathers, R. R., Hemmeter, J., Hennessey, J. C., & Burkhauser, R. V. (2011). Effects of postsecondary education on the economic status of persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 16(4), 524–536. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enq060

- Schroedel, J., & Geyer, P. (2000). Long-term career attainments of deaf and hard of hearing college raduates: Results from a 15-year follow-up survey. American Annals of the Deaf, 145, 303–314. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0099

- SCOPE. (2015). See the person not the disability campaign. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/119391089

- Spivak, G. C. (1976/1979). Translator’s preface. In J. Derrida (Ed.), Of Grammatology (pp. 8–75). Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Sutton-Spence, R., & West, D. (2011). Negotiating the legacy of hearingness. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(5), 422–432. doi: 10.1177/1077800411405428

- Sutton-Spence, R., & Woll, B. (1999). The linguistics of British sign language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Trowler, P., & Turner, G. H. (2002). Exploring the hermeneutic foundations of university life: Deaf academics in a hybrid ‘community of practice’. Higher Education, 43(2), 227–56. doi: 10.1023/A:1013738504981

- van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human sciences for an action sensitive pedagogy. Ontario: Althouse Press.

- Young, A., & Ackerman, J. (2001). Reflections on validity and epistemology in a study of deaf/hearing professional working relations. Qualitative Health Research, 11(2), 179–189. doi: 10.1177/104973230101100204

- Young, A., Ackerman, J., & Kyle, J. (2000). On creating a workable signing environment: Deaf and hearing perspectives. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 5(2), 186–195. doi: 10.1093/deafed/5.2.186

- Young, A., Ackerman, J., & Kyle, J. G. (1998). Looking on: Deaf people and the organisation of services. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Young, A., Napier, J., & Oram, R. (in press). The translated deaf self, ontological (in)security and deaf culture. The Translator.

- Young, A., & Temple, B. (2014). Approaches to social research: The case of deaf studies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Zeshan, U. (2017). Task-response times, facilitating and inhibiting factors in cross-signing. Applied Linguistics Review. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2017-0087

- Zeshan, U., & Panda, S. (2018). Sign-speaking: The structure of simultaneous bimodal utterances. Applied Linguistics Review, 9(1). doi: 10.1515/applirev-2016-1031