ABSTRACT

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as shelter-in-place orders were issued in the United States, most people were confined to their homes and adjusted to new domestic routines. This essay traces my routine of walking through different landscapes in Santa Cruz and reflects on being in-between languages and continents. I entangle personal reflections with theory in an attempt to portray the experience of being quarantined across borders in an unfamiliar country with a foreign language and culture. I explore how being in between languages, being nomadic, can serve to deconstruct identity. I find myself observing and contemplating ideas of home and travel, as well as the diversity of landscapes and forms of existence. This essay is a first-person narrative observing the thoughts and sensations that occur in an attempt to disconnect from the saturated screen experience of everyday life and connect with nature and contemplative interior states.

Screen thoughts

I received a message from a friend in my cohort yesterday asking what my new routines under quarantine are. I thought, ‘I just walk more.’ In an attempt to avoid the screen-filled experience into which my life has transformed since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, I get out of the house. I try to find reasons to be in the fresh air and walk alone through nature. On these walks, I leave even the smallest of my screens at home, escaping the vibrations, the red notification signals, and the emails piling up in my inbox. I want to escape the countless hours spent on Zoom in front of artificial backgrounds, surrounded by humans, I used to see in person, now trapped in tiny boxes on my screen. ‘Isn’t it wonderful how we can all be connected through the Internet?’ As Odell writes, connectivity is only a mundane transmission of information, what I crave for is to be open and sensitive to the environments and beings that surround me (Odell, Citation2019, p. 68).

In the precarious moment of the present – when the world has been turned upside down, when everything that had been considered a norm has been subverted, as we experience new forms of domesticity and a complete estrangement from anything public – the only thing that remains is the screen. According to the Global Internet Phenomena Report, internet traffic increased by almost 40% during the pandemic, with 80% of the internet traffic being used for social networks, video streaming and gaming (Sandvine, Citation2020, p. 5). Similar to life under a digital dictatorship or a Deleuzian society of control (Deleuze, Citation1992, p. 7), humans across the globe live today in separate shelters contained within private domesticities. Our basic means of communication have moved to the screens of our devices, windows to the worlds that we have temporarily left behind. The desire to consume can still be satisfied. Celebrities and influencers around the world are still trying to sell us products that will arrive in the mail, inside a box, not touched, in a last cheer of capitalism right before everything collapses to the ground ().

Entertainment, workouts, cooking – everything at this point in space/time is mediated through the screen. The screen of the computer, the screen of the smartphone, a broadband connection – they have become the sole purpose of existence. My digital gaze on the screen, replicas of friends on virtual call applications, and cultural products on streaming services become substitutes for human proximity in order to alleviate loneliness. I think of Jenny Odell urging me to do nothing and her so pressing question:

What does it mean to construct digital worlds while the actual world is crumbling before our eyes? (Odell, Citation2019, p. 15)

Unrooted

Yesterday, I took a walk in the forest and contemplated being surrounded by redwood trees. I noticed their long roots penetrating the earth and getting entangled with one another. I thought about my own roots in a different land, so far away from here. Where is home for me? I have moved so many times – attempts to create a narrative of my own. The farther away I run from my roots, the closer I feel to them. As I take on the mannerisms of a different country, I grow more invested in getting to know my own country’s history and culture, questioning where it all came from.

I am now living my life trapped inside a language that is not my own, using foreign sounds to frame familiar thoughts. As the days pass, the monotonous acts of everyday life start to make this place seem more and more familiar. It becomes so familiar that I forget how I am a stranger here – not really attached to the ethical or cultural norms, trying to imitate the movements and behaviors of those around me in order to pass and pretend, to feel as if I belong. Sometimes I have to look around carefully; I am not at home; I am inside the TV series and the movies set of American suburbia, in Santa Cruz, in California, in America. I am finding myself inside the images of the American Dream, I once consumed.

The woods are much wilder here. As I walk into the forest, I see a sign letting me know I might encounter wild lions: don’t run and don’t crouch. How did I manage to end up so far away from my motherland? How did my steps lead me through these woods? My friends and family in homeland, quarantined in their houses, are rediscovering familiar environments. Santa Cruz is so new, for me. I barely had time to get acquainted with this small town before I got stuck here. As I walk through the California redwood forests, listening to the birds sing, I think about how far away I am. My entire life, I have been privileged enough to move freely, to know that I can choose to chase knowledge on the other side of the planet but still have the ability to return to my country in the summers. It seems utterly surreal how this pandemic serves as a break from reality. The high levels of mobility of the past have now collapsed. I find myself stuck, trapped in a world that doesn’t belong to me.

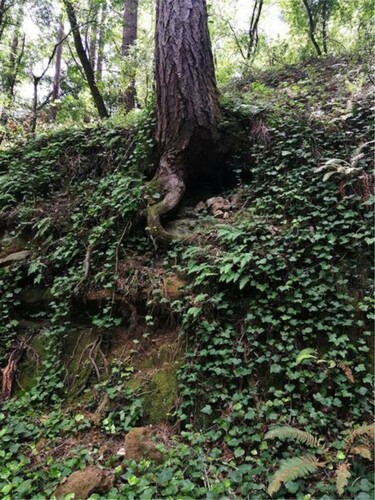

Poison ivy

As I walked, I stopped and stared at the poison ivy spreading like a virus over the rocks and the trees, not differentiating between the dead and the alive. Similar to the poison ivy, fear spreads like a virus as well-consuming governments, communities, the whole world. Above all, this is a fear of the Other. But at this point, the Other is not the Islamist or orientalized Other, the Other that stands in opposition to the West, the orient that Edward Said destabilizes in his book Orientalism (Said, Citation1979, p. xvii). The Other is not even the one whose pain haunts us in war images (Sontag, Citation2017, p. 71). Today, the Other is everyone outside of the sterilized environment of the home. The fear is a fear of the most normal and basic human interaction: fear of proximity and touch. I hear voices; there are some more people on the path. Maybe they are not wearing a mask, or maybe I am not wearing a mask, and meeting people without a mask in public is the most condemned sin today. I hear them speak English, and somehow my train of thought gets derailed. I speed up my pace to avoid another human encounter, another opportunity for contamination.

Between the ivy leaves, some flowers are starting to bloom. They are alone but beautiful, still managing to flourish despite the ivy, right next to it or between their leaves. As I walked, I saw two dead rats. I almost didn’t notice them and stepped on them. Did the poison ivy kill them? Or maybe it was the wild lions. Their corpses were starting to deform and degrade, becoming one with the earth. I stood in silence for a second. I could hear the birds, the sounds of the forest, and, far away, the cars on the highway, the sounds coming nearer and then moving away. The sounds are human but also natural. In the forest, in nature, I forget where I am. I forget who I am. I become young again, lost on an enchanted path, with only one goal – follow the path until I reach the end. The trail becomes narrower and more difficult as I climb up a hill. At the top, I arrive in a meadow. I realize it is a golf course – luscious green grass, sunny skies. I want to rest there, but I decide to return home instead.

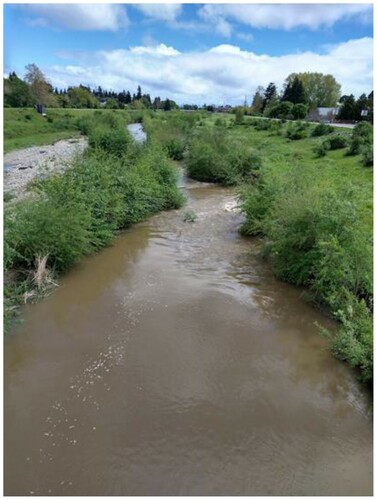

The river: shelter in place

On Wednesdays, I bike to the supermarket. As I bike by the river, I meet the homeless. I used to bike there before the pandemic, but, consumed by the speed of my everyday movements, I hadn’t had a minute to spare to think of their experience – an existence so different from mine. There is a woman I used to see at Trader Joe’s. She carries three plastic babies and treats them as real, holding them all in her arms at once. Today I saw a man with a cart outside of my house. Yesterday it was a woman with a car packed full of her belongings. According to a 2015 point-in-time count, there are 1,964 homeless individuals countywide, with 831 in the city of Santa Cruz. Santa Cruz County has the fourth-highest homeless per capita ratio in California (City of Santa Cruz Homelessness Coordinating Committee, Citation2017, p. 2) ().

As most of us shelter in place during the pandemic, in homes we rent or own, the homeless have still been roaming the streets, without masks, exposed to the virus. It was in this moment that I realized how little I really struggle, how privileged I am. Things could be so different; I am lucky to be able to stay at home, to have a home, a shelter for sheltering in place. But still, I can’t help myself. I can’t stop desiring to be with others, to touch someone else, to feel someone’s embrace. Lacan’s texts take on special resonance today:

For the unconscious demonstrates that desire is tied to prohibition and that the Oedipal crisis is determinant in sexual maturation itself. (Lacan, Citation2006, p. 723)

Sea/ocean

The other day, I took a walk on the beach. This land is so blessed and beautiful, it is uncanny. I can get lost in the forest one day and admire the waves of the Pacific Ocean the next. They say the ocean is the same everywhere, but back home, we have no ocean. We just have the sea. Sea smells salty and clean. The ocean smells infected, like a port; it makes me want to gag. I hear people say, ‘oh, how I love the smell of the ocean,’ but I despise it. I can’t even bear to go near it. I dig my toes deep into the warm sand but stay as far away as possible from the water in order to avoid the smell ().

Sea lions: thoughts on being nomadic

Before I came here, I had never seen a sea lion. The few encounters I had with them warmed my heart. I admire their in-betweenness, living between land and water. I think of my own existence between languages and borders. Too American for my Greek peers and too Greek for my American cohorts, I am positioned in the in-between of continents. It is fascinating to try to understand myself and how I construct my identity through language – through Greek and English – as I have moved from one language to another, from one place to the next. My notebooks and my writing are more fragmented than ever, words and thoughts flowing in two different alphabets – one for my past and one for my future, one for the everyday and one for sophisticated academic research, and both are at my disposal.

Despite the fact that I have twice as many resources, vocabularies, and grammar to express myself, I feel constantly misunderstood, displaced, and trapped by my own head. What sounds incredible in English can lose its point in Greek, and vice versa, but I seem to be thinking and feeling in both languages at once, living in constant translation between two worlds, between two histories, between two identities. Rosi Braidotti, a cultural studies scholar with a similar experience as mine working between different languages, describes the positionality of the polyglot as a place that allows great critical distance. She writes:

The polyglot surveys this situation with the greatest critical distance; a person who is in transit between the languages, neither here nor there, is capable of some healthy skepticism about steady identities and mother tongues. (Braidotti, Citation1994, p. 39)

A nomadic vision of the body defines it as multifunctional and complex, as a transformer of flows and energies, affects, desires, and imaginings. (Braidotti, Citation1994, p. 25)

At night, I dream of being touched. I dream of warm embraces and bodies lying next to mine. It is not the faces and voices on screens that I miss. I miss bodies, hugging, sweating, and lying next to one other. The only desire that I see fitting into our contemporary moment is the desire for intimacy and touch. I see how the collective fear circulates globally, like the idea of a virus. The idea of the Other becomes anyone who fails to follow the well-structured rules that will allow us, someday, to move back into the previous societal state that had so quickly been transformed into a faraway memory. All we can collectively do is suppress our desires for community, intimacy, and touch for now and bow to the public fear of a pandemic. I briefly stop on the wharf and look down into the water. The sea lions lie next to each other on the pier’s wooden frame, drying their skins under the sun. Their society knows no self-isolation. They can be together. I dream of such togetherness to reach our human communities once again.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Braidotti, R. (1994). Nomadic subjects. Columbia University Press.

- City of Santa Cruz Homelessness Coordinating Committee. (2017). Final report and recommendations. https://www.cityofsantacruz.com/government/about-us/city-annual-report

- Deleuze, G. (1992). Postscript on the societies of control. October, 59, 3–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/778828

- Lacan, J. (2006). Ecrits: The first complete edition in English (B. Fink, Trans.). W.W.Norton & Company. Original Year 1966.

- Odell, J. (2019). How to do nothing: Resisting the attention economy. Melville House.

- Said, E. W. (1979). Orientalism. Vintage Books.

- Sandvine. (2020). The global internet phenomena report COVID-19 spotlight. https://www.sandvine.com/covid-internet-spotlight-report

- Sontag, S. (2017). Regarding the pain of others. Picador Modern Classics.