ABSTRACT

Participatory interventions enable active user engagement, but research is needed to examine the longitudinal mechanisms through which engagement may generate outcomes. This study investigated the social processes following a web-based participatory media literacy intervention. In this program, young women were asked to create a digital counter message against the media content that promotes risk behavior. The effects of the message production were assessed at an immediate post-test and three- and six-month follow-ups. Message production increased collective efficacy at the immediate post-test, which then stimulated the sharing of self-generated messages and interpersonal conversation at the three-month follow-up. These sharing behaviors, in turn, led to critical media use and a negative attitude toward risk behavior at six months. Collective efficacy and sharing behavior sequentially mediated the effects of message production on outcomes. Theoretical and pragmatic implications are discussed.

The internet has been changing the communication landscape throughout the world. Traditional mass media-based communication is one-directional, disseminating messages produced by media professionals to lay members of the public. In internet-based communication, individuals are not just passive consumers of messages produced by media professionals. They can engage with, create, and share messages with others (Kharroub & Bas, Citation2016; Tufekci & Wilson, Citation2012).

When users engage in varying degrees, types, and depths of interaction with an educational program for a defined set of goals, the program is participatory (Couper et al., Citation2010). By providing users with opportunities to take an active rather than passive role, participatory programs seek to facilitate the behavior change process. User engagement is a central factor in determining the effectiveness of participatory programs (Donkin et al., Citation2011).

Research on outcomes of engagement has demonstrated a robust association between various forms of engagement and online and offline behaviors (see for metanalytic reviews Boulianne, Citation2015; Skoric et al., Citation2016). Current research, however, has two primary limitations. First, studies on the effects of user engagement have frequently relied on cross-sectional data, limiting their capacities for causal inference. Second, and more importantly, studies have focused only on the linkage between engagement and outcomes. Research is needed to investigate the theoretical mechanisms that can explain the pathways between engagement and outcomes.

Therefore, this study seeks to contribute to theory and research on user-generated messages by investigating the longitudinal social mechanisms through which engagement leads to outcomes. This paper begins with a review of the literature on user engagement and its effects. Drawing on available theoretical perspectives from diverse streams of research, it lays out a conceptual framework that can account for the processes of the effects. On this basis, the methods and results of a study testing the conceptual model are presented. This study concludes with a discussion of the theoretical implications of the findings for future research.

Participatory engagement

Active forms of engagement

Engagement in participatory educational programs can take various forms. In social media-based health educational programs, for instance, user engagement may be indicated by the number of views, likes, and votes. These engagement behaviors can be prompted by program components such as topical posts, news updates, and polls (Hales et al., Citation2014).

Research shows that online engagement is related to offline engagement. For example, studies have found that online political opinion expression is positively associated with offline political actions. In cross-sectional surveys, low-threshold forms of political expression (e.g. online discussion) were related to high-threshold types of political engagement (e.g. offline action; Rojas & Puig-i-Abril, Citation2009; Vaccari et al., Citation2015). Moreover, Gil de Zúñiga et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated a longitudinal association between online opinion expression (e.g. posting personal political experiences, posting political thoughts) and offline political participation (e.g. attending a town hall meeting, calling an elected public official).

Considering this, educational programs can encourage participatory engagement, such as user-generation of digital content consistent with the goal of the program. For instance, users can create messages and share them with others, instead of merely processing or responding to other-generated messages. Studies report that active engagement can be more efficacious than passive exposure in affecting health outcomes. For example, Chen et al. (Citation2015) examined a web-based participatory cancer survivorship program and found that writing posts to be shared with others improved participant outcomes (e.g. decreased depression, increased exercise), whereas reading posts written by others was unrelated to improved outcomes. Similarly, Han et al.'s (Citation2011) study about an online cancer support group found that individuals benefited more from posting supportive messages than from being exposed to the supportive messages written by others. Taken together, extant research suggests that participatory engagement through generating messages for others can play a crucial role in participatory educational programs, and that generating and sharing messages can be more impactful than exposure to messages produced by others (Chen et al., Citation2015; Gil de Zúñiga et al., Citation2014; Han et al., Citation2011).

Engagement and media literacy

Media literacy programs are educational efforts that commonly include participatory actions including message generation. Media literacy refers to users’ abilities to analyze and evaluate media messages for their embedded values and viewpoints and to produce counter messages that address harmful effects of the dominant media (Aufderheide, Citation1993). Specifically, media literacy programs aim to provide knowledge about the media and skills to counter its harmful effects through media analysis and media production modules (Aufderheide, Citation1993). The media analysis module is designed to develop an individual's critical abilities to evaluate media content. The media production module is designed to encourage individuals to create counter messages against dominant ideas perpetuated in the media. User-created counter messages are designed by participants with the goal of persuading others and the self against unhealthy messages in the media.

Participatory approaches are essential to media literacy because cultural expression and civic participation are central to creating a healthy, pluralistic society; developments in information and communication technologies allow new forms of expression and participation in everyday life (Livingstone, Citation2004). In digital counter message production, participants use digital resources such as digital photos and editing tools to design messages that are ready for dissemination via digital channels. Digital counter message generation in media literacy programs, therefore, provides an avenue for users to develop skills in content creation and to become contributing citizens of digital society.

According to action assembly theory (Greene, Citation1984), the generation of content for communication is a goal-directed behavior. In interpersonal settings, communication is always self-generated. However, advances in digital technology facilitate new and different forms of user-generated communication, which differs from interpersonal communication in two primary ways. First, messages created on digital media are readily recordable, observable, and reproducible. Second, user-created content on digital media is not bound to person-to-person delivery and can be disseminated widely. Therefore, research is needed to examine the effects of digital message generation on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors.

Message production

Accumulated theory and research suggest that counter message production can facilitate critical attitudes toward risk behavior. Studies have shown that message generation can have persuasive effects on the self (see for a review Maio & Thomas, Citation2007). Specifically, when people generated messages in support of a given position, their attitudes shifted to the direction of the position (e.g. Elms, Citation1966; Janis & King, Citation1954). Similarly, writing and posting messages rather than reading messages was associated with greater health benefits in digital health programs (Chen et al., Citation2015; Han et al., Citation2011). Active cognitive engagement has been central to the explanations for the effects of message generation during which people come up with arguments or stories that they think would be most compelling (Greenwald & Albert, Citation1968; Higgins et al., Citation1982; Maio & Thomas, Citation2007).

Counter message production can foster critical media use too. When users actively appraise the validity of claims and the reliability of the sources of media messages, they are critically using the media (Chen, Citation2013). Message production in media literacy education provides an opportunity to practice and rehearse this critical media use. In message production, participants are asked to combat the dominant media content by coming up with messages that can counter the positive media portrayal of the risk behavior. Developing counter messages, therefore, requires active processing of information and critical examination of issues and messages. Systematic processing leads to strong attitudes (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986), and people with strongly negative attitudes against a risk behavior may be skeptical of positive portrayals of the risk behavior in the media, scrutinize the messages and critically assess their persuasive intent.

These classic theoretical perspectives and principles were inherent in the counter message production part of media literacy education. Watts (Citation1967) found that writing an argument generated greater attitude change than reading an argument and writing led to a more persistent attitude than reading as assessed in six weeks. In this study, we examine the effects of digital message generation and seek to investigate its boundaries by evaluating message generation effects on critical media use and attitude toward risk behavior through a six-month follow-up.

H1. Those who produce a counter message will report (a) more critical media use and (b) less positive attitude toward risk behavior than those who do not produce a counter message.

Social processes of participatory engagement effects

Research on user-generated messages and user engagement has been growing in volume. However, few studies have investigated the mechanisms through which user-generation of messages produces effects. Generation of messages, in both interpersonal and digital media contexts, is a fundamentally social enterprise. Messages are generated with the author's future interactions with the audience in mind (Greene, Citation1984). Given this intrinsically social nature of message generation behavior, research focusing on the social processes with which message generation produces effects is especially important.

This study seeks to fill this gap in the research by predicting and testing the mechanisms connecting digital message generation to outcomes. Drawing on social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986) and on other prior research on social interaction processes (see below), we postulate that digital message generation will increase collective efficacy, which then motivates social engagement actions including sharing of the self-produced message and interpersonal conversation about the educational program. In turn, message sharing and interpersonal conversation impacts critical media use and risk behavior attitude.

Social cognitive theory predicts that enactive experience, organization of existing abilities to acquire new skills, is an important source of efficacy beliefs such as collective efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997, Citation2000). Collective efficacy refers to the belief that one's group has the abilities to carry out a given course of action (Bandura, Citation1986). Digital message production, in which media literacy education participants engage in creative expression for persuading the self and other, may provide the participants with enactive experiences. By writing and editing a digital message that they feel is most effective at countering dominant media content, users engage in persuasion of others as well as the self. Therefore, enactive experience may positively influence individuals’ beliefs in the potential of the collective (Bandura, Citation1997). That is, engagement in participatory actions may foster confidence in the group’s ability to carry out positive social change. Furthermore, Bandura (Citation1997) argues that enactive experience is a stronger source of efficacy than others, including vicarious experience in which individuals observe other's action. In sum, because counter message generation is the enactment of persuading others as well as self, this experience can provide the individual with a sense of collective efficacy. We hypothesize:

H2. Those who produce a counter message will indicate greater collective efficacy than those who do not.

Individuals with high collective efficacy, in turn, may be more willing to socially engage with others about issues than those with low collective efficacy. Previous studies have shown that collective efficacy is associated with a willingness to contribute to group goals and outcomes (Fernández-Ballesteros et al., Citation2002; Filho et al., Citation2015). In the social movement literature, the process of collectively interpreting shared problems and opportunities is thought to mediate the path between an individual's awareness of the problem and their willingness to act to address that problem for the collective good (Boudet & Bell, Citation2015).

When individuals have confidence in their group's capability for action, they may be more inclined to contribute to their common goal. Low collective efficacy among members of a community was correlated with the lack of collective action against detrimental neighboring industrial businesses (Yoon, Citation2011). Similarly, other studies have found that collective efficacy positively predicts discursive behavior among group members and the performance quality of the group (e.g. Wang & Lin, Citation2007). Velasquez and LaRose (Citation2015) found that collective efficacy was positively associated with participation in online collective actions (e.g. talk to others on behalf of group, invite others to the group, organize meetings, coordinate with others in the group, support others, find information to support the group). Extending these findings, engagement actions may include sharing messages and information within one's social networks. This study seeks to examine whether collective efficacy is a motivator of post-program social engagement actions such as message sharing and interpersonal conversation. We hypothesize:

H3a. Collective efficacy will predict greater message sharing.

H3b. Collective efficacy will predict greater interpersonal conversation.

Research has demonstrated that social engagement activities can bolster self-persuasion effects. Classic role-playing research found that self-generated messages were impactful in changing the attitude of the message generator (Janis & King, Citation1954). After individuals performed a role-play scenario advocating an issue position, their attitude became more consistent with the issue position (e.g. Elms, Citation1966; Watts, Citation1967). Similarly, engaging in interpersonal conversation about a political issue and about a previously encountered media message increased individuals’ political issue knowledge (Eveland, Citation2004; Eveland & Thomson, Citation2006). More recently, Thorson (Citation2014) found that individuals’ efforts to persuade others positively predicted their abilities to articulate arguments for their own political position.

Theoretical explanations for these phenomena come from action assembly theory (Greene, Citation1984) and the elaboration likelihood model (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). Sharing communication can strengthen the communicators’ beliefs and attitudes because talking about an issue requires cognitive exercise and rehearsal, according to action assembly theory (Greene, Citation1984). The elaboration likelihood model (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986) posits that active message processing leads to stronger attitudes, which then predict behavior change. Strengthened issue beliefs consistent with the advocated position may create attitude change consistent with those beliefs.

Previous research has examined the role of interpersonal communication in attitude change, but that research did not include a longitudinal assessment of the effects. Moreover, digital media and communication technologies facilitate the sharing of self-created messages within one's social networks. The effects of social sharing behavior, however, have rarely been examined. Our next hypotheses intend to test the long-term effects of old and new forms of sharing behavior on outcomes over a long-term.

H4a–b. Message sharing will (a) positively predict critical media use and (b) negatively predict risk behavior attitude.

H4c–d. Interpersonal conversation will (c) positively predict critical media use and (d) negatively predict risk behavior attitude.

In addition to the direct paths postulated above, indirect paths should be examined. Social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1997, Citation2000) suggests that enactive experience is a source of collective efficacy which is a cause of collective action. On this conceptual basis, we posit that the enactive experience of message generation fosters collective efficacy which motivates pro-collective actions of sharing self-created messages and sharing information via interpersonal communication.

H5a–b. Collective efficacy will mediate the effect of message generation on sharing behaviors (i.e. (a) message sharing, (b) interpersonal conversation).

Sharing behaviors may be goal-oriented communicative activities for the group and the collective. The communication mediation model holds that guided by beliefs, communicative activities promote behavioral responses consistent with the content of the communication (McLeod et al., Citation2009). Based on this theoretical perspective, we posit that motivated by collective efficacy, sharing communication facilitates behavioral decisions that are in alignment with the shared content.

H5c–d. Sharing behaviors (i.e. (c) message sharing, (d) interpersonal conversation) will mediate the effect of collective efficacy on critical media use.

H5e–f. Sharing behaviors (i.e. (e) message sharing, (f) interpersonal conversation) will mediate the effect of collective efficacy on risk behavior attitude.

Taken together, the theoretical perspectives discussed above suggest a process of sequential mediation in which message production first primes collective efficacy which in turn stimulates the sharing behaviors of message sharing and information sharing via interpersonal conversation. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H6a: Collective efficacy and sharing behavior (message sharing, interpersonal conversation) will sequentially mediate message production effects on critical media use.

H6b: Collective efficacy and sharing behavior (message sharing, interpersonal conversation) will sequentially mediate message production effects on risk behavior attitude.

Methods

Overview

Data for this study were collected as part of a larger project which determined the efficacy of a web-based media literacy education program (Cho et al., Citation2020; see also Cho et al., Citation2018). The goal of this study was to examine the longitudinal processes underlying user-generation of message effects on risk behavior attitude and critical media use. The Ohio State University's Behavioral and Social Sciences IRB approved this study (#2017B0322). The topic of the program was indoor tanning practices among young women, which increase the risk of melanoma, one of the most prevalent cancers in the United States (Siegel et al., Citation2020). Because research has linked exposure to positive media portrayals of the tanned look to a positive attitude toward indoor tanning behavior (e.g. Stapleton et al., Citation2016), the program sought to decrease pro-tanning attitudes and to increase critical media use. Details about the methods including design and sample are reported in a previous publication reporting outcome evaluation (Cho et al., Citation2020).

Design

Baseline assessment was administered a month prior to the program which was followed by an immediate post-test. Longitudinal processes were examined with three- and six-month follow-ups. The scheduling of the follow-up assessments factored in the seasonal nature of indoor tanning behavior. Studies have found that indoor tanning is more prevalent from January through March than any other months of the year, with a peak in March (Abar et al., Citation2010). Therefore, baseline assessment was conducted in September and interventions were delivered in October before the indoor tanning season began. Follow-up assessments were done in January just before the heavy indoor tanning season (three-month follow-up) and in April after the heavy tanning season (six-month follow-up).

The larger project employed a three-group design (N = 518). Participants were randomly assigned to a media literacy program condition with digital counter argument generation, a media literacy program condition with digital counter story generation, or an assessment-only control group. Because the outcome evaluation of the program (Cho et al., Citation2020) found no significant difference between argument and story generation effects on indoor tanning intention and behavior at the two follow-ups, this study combines the data obtained from the two message generation conditions. By analyzing the data from the two program conditions only, we examined whether message generation impacted the outcomes and the social mechanisms underlying the outcomes.

Participants

Participants (N = 331) were young women aged 18–24 (M = 20.16, SD = 1.32), among whom indoor tanning is the most prevalent (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2012). Participants were included in the study if they had either indoor tanned one or more times in the past 12 months or intended to indoor tan in the next 12 months (a score of 4 or higher on a scale ranging from 1 ‘very unlikely’ to ‘very likely’). The inclusion criteria were used to identify young women who were at risk of indoor tanning and to provide the educational program to the at-risk group. The same criteria were used in prior similar research (Hillhouse et al., Citation2008). Participants were recruited from a large public university in the United States. The majority of them (91.2%) were White. Retention at six months was 78% of the baseline.

The intervention

The media literacy program was comprised of media analysis and media production modules. The media analysis portion of the program was identical across the two program conditions. The program conditions differed only in the media production portion. In one condition, participants were asked to produce counter arguments; in the other condition, they were asked to produce counter stories.

The media analysis module presented how the media influence young women's perceptions and practices related to indoor tanning and advocated that young women should be true to their self and embrace their natural skin tone. The content was delivered with a young woman's voiceover, along with images, evidence, and anecdotes. Participants were asked to provide their takeaways from each section of the media analysis module.

Whereas the media analysis part was mostly didactic, the media production module was participatory as it was devoted to either counter argument or story generation by participants. Within each counter message generation condition, a sample counter argument or story was given before participants designed their own message. Both sample argument and story were contained in a one-page document combining full-color static images and text. After being shown the sample messages, participants were asked to create their own counter message and then upload it to the program portal. The user-generated messages were comprised of text and still images. To ensure anonymity, participants were asked not to include any personally identifying information in the message.

Measures

Most of the measures were given on a response scale ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’ unless noted otherwise.

Attitude toward risk behavior. Attitude toward the risk behavior of indoor tanning was measured at six months. It was measured with three pairs of bipolar adjectives including bad–good, negative–positive, and undesirable–desirable. These pairs were given on a seven-point response scale (M = 3.34, SD = 1.31, α = 0.78).

Critical media use was measured at the six-month follow-up. Using items adapted from Chen (Citation2013), participants were asked how often they have thought about: how tanned women in the media may have achieved the tanned look, what professionals may have done for the tanned women in the media to help them with the look; what creators of tanned women images in the media may want them to think; and what tanned women images in the media made them think. The response scale ranged from 1 ‘never’ to 5 ‘very often’ (M = 2.80, SD = 0.94, α = 0.89).

User-generation of digital messages. Participants were asked to design their own counter message and then upload it to the web platform (Cho et al., Citation2020). Overall, 70.11% of participants across the two message production conditions generated a counter message. In the argument condition, 66.18% of the participants generated a message. In the story condition, 74.07% generated it.

Collective efficacy was measured at the immediate post-test with these two items: ‘Young women can work together to address harmful media influences on them’ and ‘Young women can take collaborative actions against pro-tanning social norms’ (M = 6.30, SD = 0.79, α = 0.93).

Sharing of self-created message was measured at the three-month follow-up. Items assessed how much participants posted the counter message (part of whole) on their social media pages and talked about the self-created counter message with friends, siblings, and parents (M = 2.05, SD = 0.96, α = 0.87). The response scale ranged from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree.’

Interpersonal conversation was measured at the three-month follow-up. Items assessed the frequency with which participants talked about the educational program in the preceding months with friends, siblings, and parents (M = 1.85, SD = 0.71, α = 0.65). The response scale ranged from 1 ‘never’ to 5 ‘very often.’

Data analysis strategy

Analysis was conducted using statistical software R 3.5.0, package psych, and PROCESS macro (Hayes, Citation2017). Multivariate linear regression and mediation analyses were used to examine the hypotheses. A maximum likelihood method was used to estimate parameters and standard errors using all available information from partially missing cases, which were less than 10% of the total data. The bmatrix option in PROCESS macro was used to construct the serial-parallel mediation processes proposed in H6. The indirect effects were tested with 5,000 bootstrapping samples. In all models we fitted to test the hypotheses, we adjusted for the baseline behavior and intention. Details are below.

Results

Hypotheses 1

H1 stated those who produced a counter message would report more critical media use and less positive attitude toward risk behavior than those who did not produce a counter message. As indicated above, we included only the two treatment group participants in this study because the control group was not asked to produce a message. To test this hypothesis, each of the dependent variables was regressed onto the binary variable whether the participant produced a message or not. Along with baseline behavior and intention, the counter message type (i.e. argument, story) was controlled for. This was to rule out the possibility that the message type might have affected the willingness to produce a message. No significant association between message generation and critical media use at six months was observed: B = .089, p = .509. A significant negative association between message generation at treatment and attitude toward risk behavior at six months was found: B = −.463, p = .006. Those who produced a counter message as part of the program reported more negative attitude toward risk behavior at the six-month follow-up. H1 was supported for the outcome of risk behavior attitude. presents these results.

Table 1. Total effects of message generation.

Hypothesis 2

H2 expected those who produced counter messages would indicate greater collective efficacy than those who did not. As with the test of H1, we included the two treatment groups only because the control group was not asked to produce a message. We regressed collective efficacy onto message generation while controlling for message type and baseline behavior and intention. presents the results. A significant positive association between message generation during program and collective efficacy at the immediate post-test was found: B = .362, p = .002. H2 was supported.

Table 2. Regression analyses predicting social process variables.

Hypotheses 3

H3a expected collective efficacy would lead to sharing of self-created messages. A significant positive association between collective efficacy at immediate post and sharing of self-created message reported at the three-month follow-up was found (B = .163, p = .015), while controlling for all upstream variables including message type, message generation, and baseline behavior and intention. H3a was supported. H3b expected that collective efficacy would lead to interpersonal conversation. A significant positive association between collective efficacy at immediate post and interpersonal conversation reported at three-month follow-up was found (B = .244, p < .001), while controlling for all upstream variables including message type, message generation, and baseline behavior and intention. H3b was supported. The results of H3a–b are in .

Hypotheses 4

H4a–b stated message sharing would (a) positively predict critical media use and (b) negatively predict risk behavior attitude. H4c–d stated that interpersonal conversation will (c) positively predict critical media use and (d) negatively predict risk behavior attitude. Each of the dependent variables was regressed onto both message sharing and interpersonal conversation, controlling for all upstream variables including message type, message generation, baseline behavior and intention, and collective efficacy at the immediate post-test. The results are shown in .

Table 3. Regression analyses predicting outcome variables.

An almost significant positive association between sharing of self-created message at three months and critical media use at six months was found: B = .139, p = .051. A significant positive association between interpersonal conversation at three months and critical media use at six months was found: B = .277, p = .004. Message sharing and interpersonal conversation as reported at three months increased critical media used reported at six months (joint likelihood ratio test p < .001). H4a–b were mostly supported.

A significant negative association between message sharing (B = −.210, p = .016) and interpersonal conversation (B = −.235, p = .044) at three months and risk behavior attitude at six months was found. Message sharing and interpersonal conversation as reported at three months decreased positive attitude toward risk behavior at six months (joint likelihood ratio test p < .001). H4c–d were supported.

Hypotheses 5

H5a–b predicted collective efficacy would mediate the effect of message generation on message sharing and interpersonal conversation. For H5a, a mediation analysis was performed in which message generation was the independent variable, collective efficacy was the mediator, and sharing of self-created messages was the dependent variable. The same set of upstream variables (i.e. message type, message generation, and baseline behavior and intention) was controlled for. The bootstrapped mediation effect through collective efficacy was .051, with a 95% CI of (.006, .115). H5a was supported.

A mediation analysis was performed in which message generation was the independent variable, collective efficacy was the mediator, and interpersonal conversation was the dependent variable. The same set of upstream variables (i.e. message type, message generation, and baseline behavior and intention) was controlled for. The bootstrapped mediation effect through collective efficacy was .072, with a 95% CI of (.018, .138). H5b was supported.

H5c–d predicted sharing behaviors would mediate the effect of collective efficacy on critical media use. Mediation analyses were performed in which collective efficacy was the causal variable and message sharing and interpersonal conversation were the mediators, for the outcome variable of critical media use. The bootstrapped indirect effect of collective efficacy mediated by sharing of self-created message was .02 (95% CI = −.0007, .063), which was not significant. The bootstrapped indirect effect of collective efficacy mediated by interpersonal conversation was .07 (95% CI = .025, .123), which was significant. The bootstrapped indirect effect of collective efficacy jointly mediated by both mediators was .09 (95% CI = .042, .157), which was significant. H5c–d were partially supported.

H5e–f predicted sharing behaviors would mediate the effect of collective efficacy on risk behavior attitude. Mediation analyses were performed in which collective efficacy was the causal variable and message sharing and interpersonal conversation were the mediators, for the outcome variable of risk behavior attitude. The bootstrapped indirect effect of collective efficacy mediated by sharing of self-created message was −.04 (95% CI = −.094, −.006), which was significant. The bootstrapped indirect effect of collective efficacy mediated by interpersonal conversation was −.05 (95% CI = −.116, .001), which was not significant. The bootstrapped indirect effect of collective efficacy jointly mediated by both mediators was −.09 (95% CI = −.173, −.029), which was significant. H5e–f were partially supported. summarizes direct effects of the causal pathways in this model. presents the mediation effects in this model.

Table 4. Direct effects of causal pathways.

Table 5. Indirect effects of causal pathways.

Hypotheses 6

H6a predicted message production effects on critical media use will be sequentially mediated by collective efficacy and sharing behaviors (message sharing, interpersonal conversation). A serial-parallel mediation analysis was performed in which message production was the causal variable, collective efficacy was the first mediator, message sharing and interpersonal conversation were the second set of parallel mediators, for the outcome variable of critical media use. The bootstrapped indirect effect of message production mediated by collective efficacy and message sharing was .007 (95% CI = −.0003, .0242), which was not significant. The bootstrapped indirect effect of message production mediated by collective efficacy and interpersonal conversation was .022 (95% CI = .0032, .0513), which was significant. H6a was partially supported.

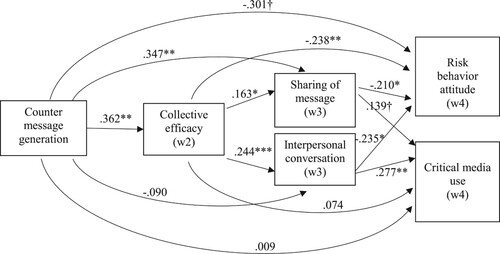

H6b predicted message production effects on risk behavior attitude will be sequentially mediated by collective efficacy and sharing behaviors (message sharing, interpersonal conversation). A serial-parallel mediation analysis was performed in which message production was the causal variable, collective efficacy was the first mediator, message sharing and interpersonal conversation were the second set of parallel mediators, for the outcome variable of risk behavior attitude. The bootstrapped indirect effect of message production mediated by collective efficacy and message sharing was −.011 (95% CI = −.0311, −.0001), which was significant. The bootstrapped indirect effect of message production mediated by collective efficacy and interpersonal conversation was −.018 (95% CI = −.0509, −.0002), which was significant. H6b was supported. presents sequential parallel mediation effects in this model. shows the regression model of social engagement processes of message generation effects on critical media use and risk behavior attitude.

Figure 1. Regression model of social engagement process of message generation effects on risk behavior attitude and critical media use. w2 = immediate post, w3 = 3-month post, w4 = 6-month post. †p < .1, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 6. Indirect effects of serial-parallel mediation processes.

Discussion

This study conceptualized and evaluated a model of social processes of participatory engagement effects. It examined the social mechanisms underlying the long-term impact of user-generation of a counter message as part of a media literacy education program. It used four-wave panel data to investigate the causal effects of the message generation on two types of outcomes including critical media use and risk behavior attitudes at six months post-intervention. In all hypothesis testing, rigorous statistical control of all upstream variables was employed.

The results provide a theoretical perspective on the social processes of participatory engagement effects. The social processes involve collective efficacy, sharing of self-created messages, and interpersonal conversation within one's social network. In the initial path, user-generation of the counter message activated collective efficacy, which social cognitive theory considers a key conduit for individual and social change.

Collective efficacy, in turn, promoted sharing behaviors. In this study, sharing behaviors included sharing of the user-generated message and sharing information gained from the educational program with members of one's social networks. These sharing behaviors merit attention. In prior research, social processes after program participation have often been operationalized as efforts to seek additional information, reduce uncertainty, or gain social support for the self (Jeong & Bae, Citation2018; So et al., Citation2019). This study suggests a pathway primed by a differential motivation. In this study, individuals equipped with collective efficacy reached out to others to share the information obtained from and the message generated through the participation in the educational program. This could be considered more other-oriented and altruistic actions than the previously examined behaviors.

These sharing behaviors also differ from the more traditional role-playing behavior examined in prior self-persuasion studies (see Maio & Thomas, Citation2007). In this previous research, message generation effects were limited to the self. The present study investigated the effects of message production on collective efficacy and on other-oriented behaviors including message sharing and interpersonal conversation. The results suggest that the user-generation of content produced second-order exposure for the extended audiences of the friends and family of the program participants. Motivated by collective efficacy, the participants shared the self-produced message and talked with others about the information obtained from the educational program.

Further theoretical insight is provided from the results of the sequential mediation analyses. The effect of message production on risk behavior attitude was serially mediated by collective efficacy and then the two other-oriented behaviors of message sharing and interpersonal conversation. Similarly, the effect of message production on critical media use was serially mediated by collective efficacy and then interpersonal conversation. Collective efficacy was a conduit linking the enactive experience of counter message production and the collective action of sharing behaviors. Collective efficacy also indirectly impacted outcomes via sharing behaviors. The sequential mediation processes evidenced in this study illustrate a social mechanism that counter message production can activate for others and self.

Implications

Previous theorizing on message production has focused on psychological processes (Pingree, Citation2007). This study complements extant theory as it developed and evaluated an initial model describing the social mechanisms of message production effects. In doing so, this study integrated theoretical perspectives and research findings in diverse traditions including those of action assembly theory, social cognitive theory, self-persuasion, and online behaviors. Drawing on action assembly theory, in particular, it was proposed that the generation of messages in digital or in-person settings is a social enterprise because it involves thoughts about other's reactions and subsequent interaction with others.

This study adds to theoretical and practical knowledge about collective efficacy. Abundant communication research has examined self-efficacy, and limited work has focused on collective efficacy (Cho et al., Citation2009). Although available research has found that collective efficacy is an important predictor of change-related attitudes and actions (e.g. Shefner-Rogers et al., Citation1998), few studies investigated how collective efficacy can be cultivated. This study shows that participatory engagement through message generation can be a way to foster collective efficacy. In turn, collective efficacy predicted socially minded communication behaviors including message sharing and information sharing through interpersonal conversation.

Findings suggest that message production could contribute to social change via other-oriented sharing behaviors. These sharing behaviors, primed by collective efficacy, are notable. As discussed above, in existing research, the actions after program participation were often self-focused (e.g. seeking information and social support for the self). Similarly, in prior message production research, the beneficiary of the production was frequently the self. The results of this study show that message production can create second-order exposure, benefiting others in one's social network. Future research should continue to investigate this second-order exposure as an effect of message production.

Of note, the social process model conceptualized and evaluated in this study was facilitated by digital technologies. The support for the model suggests a new potential of online engagement effects. User creation of counter messages, through sequential mediation by collective efficacy and sharing behaviors, could produce long-term effects on attitudes and actions. Future research could examine the scalability of this process.

Findings inform the theoretical basis and practical efforts for media literacy education. In the domain of media literacy education, little research has theorized the social processes that counter message production may activate and how the process may unfold over time. This study provides a longitudinal look at the social mechanisms of message generation. Future media literacy programs should include message production to foster collective efficacy beliefs so that participants can be motivated to be an agent of change as well as to alter their own behaviors. Future educational efforts should also encourage post-production message sharing and interpersonal conversation within social networks (e.g. Cho et al., Citation2004). This is especially important to combat the social norms that drive risky behaviors such as indoor tanning.

The results of this study are noteworthy as they were observed from a sample of at-risk population, who either had engaged in or intended to engage in the risk behavior at baseline. These at-risk young women voluntarily generated counter messages during the participatory media literacy education program. They not only generated a counter message against a dominant culture but also shared the message and information from the educational program, serving as an agent for social change. The mechanisms evaluated in this study with an at-risk group have the potential to be applicable to other populations.

Findings further suggest that the production of counter message contributes to the modification of attitudes. Prior research showed that online engagement and expression may reinforce, rather than alter, existing attitude. For example, Cho et al. (Citation2018) found that online political expression reinforced partisan thoughts and hardened prior political preferences. This study shows that counter message production as part of a planned program (e.g. media literacy education) can be an important means to facilitate attitudinal change among program participants.

Limitations

This study's limitations include its focus on one issue: indoor tanning practices increasing melanoma risk. Future research should apply the conceptual model of this study to other topics. The sample consisted of young women aged 18–25 because this is the group among whom the melanoma risk-increasing behavior is most prevalent (U.S. CDC, Citation2012).

As Chakravartty et al. (Citation2018) pointed out, the field of communication must examine communication phenomena among diverse populations. Future research should examine the theoretical processes identified in this study with samples that are more diverse in sex/gender, race, and ethnicity. This model could also be tested in online social movement contexts. Important progress has been made in this line of research (e.g. Mundt et al., Citation2018) and the present framework could be useful for mapping the social processes that drive collective action online and offline (see also Cho & Kuang, Citation2015).

Future research should improve the measurement of sharing behaviors. This assessment can include both offline and online sharing. The measurement should also reflect the new and different possibilities for diffusion and dissemination presented by diverse social media platforms. In addition, the implications of social media in the conceptualization, design, and evaluation of media literacy education should be considered (Cho et al., Citation2022).

Final comments

By examining effects of active rather than passive engagement, social rather than psychological processes, and longitudinal rather than cross-sectional mechanisms, this study contributes to theory and research on online user engagement and user-generation of counter messages. It shows that counter message generation, via collective efficacy and sharing behaviors, could facilitate long-term changes in users. Furthermore, the effects of collective efficacy and sharing behaviors observed in this study may signal the potential of user-generated counter messages to drive meaningful social change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abar, B. W., Turrisi, R., Hillhouse, J., Loken, E., Stapleton, J., & Gunn, H. (2010). Preventing skin cancer in college females: Heterogeneous effects over time. Health Psychology, 29(6), 574–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021236

- Aufderheide, P. (1993). Media literacy: A report of the national leadership conference on media literacy. Aspen Institute.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

- Bandura, A. (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(3), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00064

- Boudet, H. S., & Bell, S. E. (2015). Social movements and risk communication. In H. Cho, T. Reimer, & K. McComas (Eds.), The Sage handbook of risk communication (pp. 304–316). Sage.

- Boulianne, S. (2015). Social media use and participation: A meta-analysis of current research. Information, Communication, and Society, 18(5), 524-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542

- Chakravartty, P., Kuo, R., Grubbs, V., & McIlwain, C. (2018). #Communicationsowhite. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy003

- Chen, Y. C. (2013). The effectiveness of different approaches to media literacy in modifying adolescents’ responses to alcohol. Journal of Health Communication, 18(6), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.757387

- Chen, Z., Koh, P. W., Ritter, P. L., Lorig, K., Bantum, E. O., & Saria, S. (2015). Dissecting an online intervention for cancer survivors: Four exploratory analyses of internet engagement and its effects on health status and health behaviors. Health Education and Behavior, 42(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114550822

- Cho, H., Cannon, J., Lopez, R., & Li, W. (2022). Social media literacy: A conceptual framework. New Media & Society, 146144482110685.https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211068530

- Cho, H., & Kuang, K. (2015). The societal risk reduction motivation model. In H. Cho, T. O. Reimer, & K. A. McComas (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of risk communication (pp. 117–131). Sage.

- Cho, H., Oehlkers, P., Mandelbaum, J., Edlund, K., & Zurek, M. (2004). The Healthy Talk Campaign of Massachusetts: A communication-centered approach. Health Education, 104(5), 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280410560569

- Cho, H., So, J., & Lee, J. (2009). Personal, social, and cultural correlates of self-efficacy beliefs among South Korean college smokers. Health Communication, 24(4), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230902889381

- Cho, H., Song, C., & Adams, D. (2020). Efficacy and mediators of a web-based media literacy intervention for indoor tanning prevention. Journal of Health Communication, 25(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1712500

- Cho, H., Yu, B., Cannon, J., & Zhu, Y. (2018). Efficacy of a media literacy intervention for indoor tanning prevention. Journal of Health Communication, 23(7), 643–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2018.1500659

- Cho, J., Ahmed, S., Keum, H., Choi, Y. J., & Lee, J. H. (2018). Influencing myself: Self-reinforcement through online political expression. Communication Research, 45(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216644020

- Couper, M. P., Alexander, G. L., Zhang, N., Little, R. J. A., Maddy, N., Nowak, M. A., McClure, J. B., Calvi, J. J., Rolnick, S. R., Stopponi, M. A., & Johnson, C. D. (2010). Engagement and retention: Measuring breadth and depth of participant use of an online intervention. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(4), e52. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1430

- Donkin, L., Christensen, H., Naismith, S. L., Neal, B., Hickie, I. B., & Glozier, N. (2011). A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(3), e52. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1772

- Elms, A. C. (1966). Influence of fantasy ability on attitude change through role playing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023509

- Eveland, W. P. (2004). The effect of political discussion in producing informed citizens: The roles of information, motivation, and elaboration. Political Communication, 21(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600490443877

- Eveland, W. P., & Thomson, T. (2006). Is it talking, thinking, or both? A lagged dependent model of discussion effects on political knowledge. Journal of Communication, 56(3), 523–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00299.x

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Díez-Nicolás, J., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., & Bandura, A. (2002). Structural relation of perceived personal efficacy to perceived collective efficacy. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00081

- Filho, E., Tenenbaum, G., & Yang, Y. (2015). Cohesion, team mental models, and collective efficacy: Towards an integrated framework of team dynamics in sport. Journal of Sports Science, 33(6), 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.957714

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., Molyneux, L., & Zheng, P. (2014). Social media, political expression, and political participation: Panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 612–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12103

- Greene, J. O. (1984). A cognitive approach to human communication: An action assembly theory. Communication Monographs, 51(4), 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390203

- Greenwald, A. G., & Albert, R. D. (1968). Acceptance and recall of improvised arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(1), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021237

- Hales, S. B., Davidson, C., & Turner-McGrievy, G. M. (2014). Varying social media post types differentially impacts engagement in a behavioral weight loss intervention. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0274-z

- Han, J. Y., Shah, D. V., Kim, E., Namkoong, K., Lee, S.-Y. Y., Moon, T. J., Cleland, R., Bu, Q. L., McTavish, F. M., & Gustafson, D. H. (2011). Empathic exchanges in online cancer support groups: Distinguishing message expression and reception effects. Health Communication, 26(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2010.544283

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford.

- Higgins, E. T., Douglas, M. C., & Fondacaro, R. (1982). The “communication game”: Goal-directed encoding and cognitive consequences. Social Cognition, 1(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1982.1.1.21

- Hillhouse, J., Turrisi, R., Stapleton, J., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). A randomized controlled trial of an appearance focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Cancer, 113(11), 3257–3266. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23922

- Janis, I. L., & King, B. T. (1954). The influence of role-playing on opinion change. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49(2), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0056957

- Jeong, M., & Bae, R. E. (2018). The effect of campaign-generated interpersonal communication on campaign-targeted health outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health Communication, 33(8), 988–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1331184

- Kharroub, T., & Bas, O. (2016). Social media and protests: An examination of Twitter images of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1973–1992. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815571914

- Livingstone, S. (2004). Media literacy and the challenge of new information and communication technologies. Communication Review, 7(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714420490280152

- Maio, G. R., & Thomas, G. (2007). The epistemic-teleological model of deliberate self-persuasion. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 11(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868306294589

- McLeod, D. M., Kosicki, G. M., & McLeod, J. M. (2009). Political communication effects. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 228–251). Routledge.

- Mundt, M., Ross, K., & Burnett, C. M. (2018). Scaling social movements through social media: The case of Black Lives Matter. Social Media + Society, 4(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118807911

- Petty, R., & Cacioppo, J. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Springer.

- Pingree, R. J. (2007). How messages affect their senders: A more general model of message effects and implications for deliberation. Communication Theory, 17(4), 439–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00306.x

- Rojas, H., & Puig-i-Abril, E. (2009). Mobilizers mobilized: Information, expression, mobilization and participation in the digital age. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 14(4), 902–927. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01475.x

- Shefner-Rogers, C. L., Rao, N., Rogers, E. M., & Wayangankar, A. (1998). The empowerment of women dairy farmers in India. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 26(3), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909889809365510

- Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., & Jemal, A. (2020). Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(1), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21590

- Skoric, M. M., Zhu, Q., Goh, D., & Pang, N. L. S. (2016). Social media and citizen engagement: A meta-analytic review. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1817–1839. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815616221

- So, J., Kuang, K., & Cho, H. (2019). Information seeking upon exposure to risk messages: Predictors, outcomes, and mediating roles of health information seeking. Communication Research, 46(5), 663–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216679536

- Stapleton, J. L., Hillhouse, J., Coups, E. J., & Pagoto, S. (2016). Social media use and indoor tanning among a national sample of young adult non-Hispanic white women: A cross-sectional study. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology, 75(1), 218–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.043

- Thorson, E. (2014). Beyond opinion leaders: How attempts to persuade foster political awareness and campaign learning. Communication Research, 41(3), 353–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212443824

- Tufekci, Z., & Wilson, C. (2012). Social media and the decision to participate in political protest: Observations from Tahrir square. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01629.x

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2012). Use of indoor tanning devices by adults — United States, 2010. MMWR, 61(18), 323–326.

- Vaccari, C., Valeriani, A., Barbera, P., Bonneau, R., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. A. (2015). Political expression and action on social media: Exploring the relationship between lower- and higher-threshold political activities among Twitter users in Italy. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12108

- Velasquez, A., & LaRose, R. (2015). Youth collective activism through social media: The role of collective efficacy. New Media & Society, 17(6), 899–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813518391

- Wang, S. L., & Lin, S. S. J. (2007). The effects of group composition of self-efficacy and collective efficacy on computer-supported collaborative learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(5), 2256–2268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2006.03.005

- Watts, W. A. (1967). Relative persistence of opinion change induced by active compared to passive participation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021196

- Yoon, I. (2011). A case study of low collective efficacy and lack of collective community action. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 21(6), 625–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2011.583496