ABSTRACT

This study examines trolls affiliated with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that targeted conversations around former Houston Rockets’ General Manager Daryl Morey, who tweeted support for Hong Kong protests and apologized in October 2019. Researchers coded 5,800 tweets to inform a machine-learning approach examining a corpus of over 163,000 tweets. Findings suggested that a PRC disinformation campaign was organized as a faux third-party image repair effort that sought to force an apology, deprive Morey of support, discourage future image threats, and shape public understanding. This effort used provocation, bolstering, barnacle, redirection, and attack the accuser. While apologies are generally held to be restorative in image repair and statecraft literature, Morey’s apology was a turning point that rallied opposition to the PRC and support for democracy and Morey. Implications include insight into the prevalence, strategies, and efficacy of PRC trolls, as well as recommendations for social media practitioners.

The 2016 U.S. presidential election raised awareness about fake social media accounts (i.e. trolls), which leverage disinformation in a coordinated manner toward political action and social division (Zannettou et al., Citation2019). In 2019, U.S. news media raised concerns that trolls from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) were spreading disinformation about Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests. Online discourse about these protests peaked in response to a tweet from then-Houston Rockets’ General Manager Daryl Morey. On October 4, 2019, Morey tweeted ‘Fight for freedom: Stand with Hong Kong.’ The tweet, benign by American standards, created a crisis for the PRC and threatened its relationship with the National Basketball Association (NBA). The crisis unfolded on Twitter (now known as X) with Morey apologizingFootnote1 for the tweet, NBA stakeholders rebuking him with their own Twitter statements, and users constructing defenses for the PRC and Morey. The Wall Street Journal alleged PRC trolls strategically targeted this discourse (Cohen et al., Citation2019).

The discourse surrounding Morey’s Hong Kong tweet provides an opportunity to consider the interplay between authentic and inauthentic online voices and responses to organized attempts to mitigate perceived wrongdoing by a state actor (i.e. the PRC). Because citizens of the PRC are barred from Twitter and instead use Chinese state-controlled social media platforms, grassroots efforts to preserve or rebuild the reputation of the PRC are limited. This constraint increases the pressure to respond using inauthentic accounts operated by paid or otherwise induced operators acting on behalf of the state. Morey’s comment presented a reputational crisis that was exacerbated by situational factors. The Rockets General Manager was a front-office representative of China’s most popular sports team (Guo et al., Citation2023) and his comments illustrated Western obstruction to the PRC’s territorial sovereignty, which is its ‘topmost vital’ and ‘core’ state goal (Goldstein, Citation2020, p. 168).

Broadly, we frame the disinformation efforts of trolls as constituting a faux third-party image repair effort (Benoit, Citation2015b) as part of PRC statecraft, which entails strategies for promoting national interest in the international arena. We focus on the comparative prevalence, contributions, and strategies of troll and non-troll accounts within Twitter discourse surrounding Daryl Morey’s support for Hong Kong. Within this effort, we view the Morey affair as a longitudinal event, with his apology as a turning point, which facilitates the assessment of trolls’ augmentation of disinformation strategies when image repair goals are reached (e.g. an offender apologizes) and assessment of the efficacy of trolls via the communication of authentic accounts. Our efforts also recognize the specificities in Chinese cultural norms around reputation and crisis (Yu & Wen, Citation2003) and its indigenized image repair strategies (Hu & Pang, Citation2018). This recognition enriches traditional image repair research that overwhelmingly focuses on the efforts of non-government organizations and entities from Western cultures (Benoit, Citation2015a; Nekmat et al., Citation2014).

Below we detail the historical and political context surrounding Daryl Morey’s tweet and the resulting fallout, and offer an accounting of state-affiliated disinformation campaigns using Benoit’s image repair theory (IRT) as a framework. We then share qualitative and quantitative analyses of the social media conversations around Morey’s tweet and discuss the implications of these findings for practitioners and scholars.

Historical context

Basketball has been entwined in Chinese culture for over a century, and today basketball is China’s most popular sport (Huang, Citation2013). The career of Yao Ming, who played for the Houston Rockets (2002–2011), solidified basketball’s popularity and the Rockets as China’s favorite team (Guo et al., Citation2023). The PRC is integral to the NBA because it is home to the world’s third-largest consumer market and purchases $5 billion in NBA media and merchandise annually (Ostler, Citation2022).

In 2019, Daryl Morey, then-Houston Rockets’ General Manager, tweeted a graphic supporting Hong Kong, whose citizens were protesting China’s violations of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration. The declaration guaranteed 50 years of legislative autonomy and freedom of speech following the British rescinding control over the colony, which occurred in 1997. The PRC has since outlawed protests, jailed violators of speech codes, and engaged in heavy-handed policing in the territory, asserting that a single unified Chinese territory exists and is subject to the PRC government (i.e. the One China policy; Ruwitch, Citation2020). The reunification of all disputed territories (e.g. Hong Kong) under the PRC is central to its government’s strategic plan, as well as within cultural and political narratives about rectifying what the Chinese Communist Party describes as the century of humiliation (i.e. a 100-year period in which Western powers used military force to access and annex parts of China; Goldstein, Citation2020).

Morey’s Tweet consumed news cycles and social media conversations for several days. The PRC demanded Morey be fired, blacklisted the Houston Rockets from broadcasts, banned its merchandise, canceled sponsorships, and threatened to extend those sanctions to the NBA at large (Cha & Lim, Citation2019), resulting in $200 million in lost revenue (Wojnarowski & Lowe, Citation2020). Morey apologized on Twitter, noting he ‘ … was merely voicing one thought, based on one interpretation, of one complicated event … ’ and that he was learning about other perspectives. The NBA characterized Morey’s tweet as something that ‘deeply offended many of our friends and fans in China, which is regrettable’ on Twitter, but indicated in Mandarin on Weibo that the NBA was ‘extremely disappointed by the inappropriate remarks made by [Morey].’ LeBron James, the NBA’s most prominent player, added Morey was misinformed about Hong Kong, but could not articulate how (Youngmisuk, Citation2019). The subsequent social media discourse around Morey’s tweet reflects and shapes the understanding of sport, public policy, and the relevant stakeholders (e.g. Morey, PRC, and NBA) – warranting further exploration (Guo et al., Citation2023).

Review of literature

Chinese statecraft & sport

Akin to other authoritarian regimes, the PRC uses sport in multiple ways in its statecraft to project strength and unity or validate its policies. The Chinese elite sports system of Juguo tizhi directs vast resources toward identifying and training athletes, intending to validate itself via victories in international competitions (Wei et al., Citation2010). The PRC hosts international sporting events (e.g. the 2008 and 2022 Olympics) featuring feats of engineering and awe-inspiring spectacles that construct an image as a rising superpower (Berkowitz et al., Citation2007). China’s domestic sports media are imbued with state-approved rhetoric and collectivistic frameworks (Bie & Billings, Citation2015; Billings et al., Citation2009), which promote nationalism and equate support for the government with patriotism (Koch, Citation2013).

The PRC, however, uses sport within its statecraft in a novel way inaccessible to other authoritarian regimes. Its third-largest consumer market in the world attracts and creates asymmetrical relationships with Western companies (e.g. NBA). The PRC leverages the interdependence of economic exchange in a predatory fashion to achieve its political objectives, including influencing discourse, silencing criticism, and projecting a positive image. While it is sensitive to various issues (e.g. oppressive labor practices, destructive environmental impact, and human rights record), the PRC especially utilizes American entertainment to reinforce its territorial objectives – whether through denying the existence of autonomous states (e.g. Taiwan) or supporting the One China policy (Cha & Lim, Citation2019).

O’Connell (Citation2022) forwarded a three-step process by which the PRC uses foreign entities within its statecraft. First, an offense is committed by foreigners and leads to censorship or threats of censorship. Morey’s tweet was met with censorship of Houston Rockets’ games and merchandise because it constituted a reputational threat for the PRC – an insertion into its territorial sovereignty by a Westerner whom its people may find credible in front of Twitter’s 330 million active users (Cha & Lim, Citation2019; deLisle, Citation2020; Goldstein, Citation2020). Second, to mitigate damages, offenders reverse their positions, and others distance themselves from the offender with statements. Morey apologized and NBA stakeholders (e.g. James and Silver) depicted him as misinformed, inappropriate, and not representative of the league. Third, peripheral stakeholders gain an understanding of what subjects or positions are taboo and self-censor to avoid involvement in controversy. While self-censorship is difficult to identify, James’ inability to articulate why Morey was misinformed or the silence of politically active and social justice-oriented stakeholders (e.g. Steve Kerr) may indicate self-censorship. These steps are positioned as enhancing the PRC’s territorial agenda and reputation internationally.

While a useful starting point, O’Connell’s (Citation2022) process overemphasizes the acquiescence or silence of institutions and public figures as the conclusion of statecraft, with the public noting and self-censoring taboo topics. Yet, even he noted, ‘attempting to silence foreign critics on social media certainly fits within a framework of disinformation campaigns and, more broadly, within Chinese efforts to use cyberspace to alter perceptions of the Communist Party regime’ (pp. 1117–1118). To date, there is an absence of such investigations, despite evidence that the public does not merely replicate the perspectives of mass media, organizations, or influential figures (Nisbet, Citation2010). Public discourse informs understandings and attitudes toward discussed stakeholders and may constitute additional threats to the PRC’s strategic cultivation of its image. As such, we extend O’Connell’s process by considering subsequent social media discourse around Daryl Morey’s tweet and apology:

RQ1: How did Twitter users respond to Daryl Morey’s tweet and apology about Hong Kong?

Disinformation and social media trolls

State-affiliated social media disinformation became a public issue following the 2016 U.S. Presidential campaign and the indictment of 13 Russian nationals for election interference (US v. IRA LLC, Citation2018). Subsequent scholarship has focused on the St. Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency (IRA), a tool of the Russian government, that took on the persona of Americans via fake social media accounts and encouraged discontent, division, or disconnection with reality among the U.S. populace (Linvill & Warren, Citation2020; Zannettou et al., Citation2019). Trolls created or amplified narratives that promoted false information favorable to their state sponsors (e.g. alternative explanations for the crash of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17, which was shot down by Russian-controlled forces; Vesselkov et al., Citation2020). They also undermined vaccination, human-caused climate change, and the safety of genetically modified foods, and promoted distrust of the scientific community (Strudwicke & Grant, Citation2020; Walter et al., Citation2020). Diverse tactics were employed in these efforts: adopting novel identities, deleting old posts to obfuscate intentions, coordinating across platforms, posting emotionally triggering commentary to inspire political rage, and tailoring messaging to specific communities targeted for manipulation (Al-Rawi & Rahman, Citation2020; Ehrett et al., Citation2022; Freelon et al., Citation2020; Lukito, Citation2019).

The PRC, like Russia, directs efforts toward reinforcing hegemony at home, shaping global perceptions of its domestic policies (e.g. treatment of the Uyghur Muslims; Linvill & Warren, Citation2021), and undermining participation in democracies (Sganga, Citation2022). Common topics of PRC disinformation are the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement and Taiwan’s independence (Paul, Citation2020). Domestically, China utilizes state-owned media (Kurlantzick, Citation2022) and employs nearly two million social media users, known as the 50 Cent Party, to promote PRC-aligned positions and accomplishments (King et al., Citation2017). Global audiences are targeted with a host of subtle tactics, such as recruiting YouTube influencers to espouse favorable propaganda, creating pro-PRC astroturfing campaigns on state-backed multimedia platforms, and maintaining fake accounts on every major social media platform (Mozur et al., Citation2021; Myers et al., Citation2022). Ongoing PRC-aligned social media campaigns are attributed to an actor that Google-owned cybersecurity company, Mandiant, dubbed Dragonbridge (Kagubare, Citation2022).

A prominent tactic PRC campaigns use is the flooding of conversations with low-quality messages from large numbers of social media accounts (Linvill & Warren, Citation2021). This strategy hijacks hashtags and threads, dilutes genuine voices, boosts views aligning with PRC policies, and influences how algorithms give prominence to topics. Flooding often targets specific individuals with online harassment meant to intimidate opposition, at home and abroad. China is not the only nation to engage in this activity online (Pearce, Citation2015), but does so extensively, especially in targeting journalists and those concerned with human rights and territorial disputes (Zhang & Cave, Citation2022).

Image repair theory

IRT considers how individuals or collectives ‘save face’ or repair their images and mitigate the consequences of reputational threats after transgressions or crises (Benoit, Citation1995), including within sporting, intercultural, and political contexts (Benoit, Citation2015a). IRT is an apt framework for this manuscript as it extends to government-related image restoration (Peijuan et al., Citation2009; Zhang & Benoit, Citation2009), is consistent with the Chinese concept of mianzi kung-fu (i.e. facework, or the ways entities/people maintain their self-image; Yu & Wen, Citation2003), and encompasses third-party image repair efforts (Benoit, Citation2015b). Moreover, these image repair efforts occurred following backlash from public stakeholders (Drumheller & Kinsky, Citation2021).

IRT identifies five categories of image repair strategies (Benoit, Citation1995). Denial questions the veracity that an event or action occurred or denies one’s role in its occurrence; offenders using this strategy take no responsibility for a transgression. Evasion of responsibility relieves the burden of blame from an offender via claims of provocation by another, lack of information, an accident, or good intentions. This strategy minimizes the intent behind a crisis or transgression. Efforts to reduce the offensiveness of wrongdoing occur via stressing a positive record, minimizing the seriousness of the issue, comparing it to other acts, identifying positive consequences, or attacking accusers. This strategy prioritizes shaping public perception after a crisis or transgression. Corrective actions recognize a crisis or transgression and seek resolution with plans to resolve and prevent similar offenses. Mortification acknowledges one’s role in the crisis or transgression and apologizes for the offense.

Scholars have also documented image repair strategies utilized by culturally Chinese entities in response to a variety of crises, spanning pandemics (Zhang & Benoit, Citation2009), manufacturing mishaps (Hu & Pang, Citation2018; Peijuan et al., Citation2009), misbehavior of military members (Yu & Wen, Citation2003), and poor performances of athletes (Wen et al., Citation2009). Two cultural norms undergird IRT within Chinese contexts: save face and avoid risk. Yu and Wen (Citation2003) suggested that Chinese culture encourages and creates expectations to save face. ‘Consequently, instead of telling a shameful truth, Chinese people will attempt to cover it up’ (p. 54). The second norm positions communication during crises as risky, which ‘ … polarizes the Chinese to either avoid communication altogether or … to divert attention from the crisis’ (p. 54). These norms inform a reliance on denial, evading responsibility, and reducing offensiveness (Peijuan et al., Citation2009; Wen et al., Citation2009; Zhang & Benoit, Citation2009). In situations where denial is not plausible, contradictory patterns of bolstering and corrective action are offered (Peijuan et al., Citation2009; Zhang & Benoit, Citation2009). Hu and Pang (Citation2018) identified three indigenized strategies specific to Chinese entities within nine corporate crises: barnacle or closely following state talking points, third-party endorsement, which seeks input from experts to minimize crisis severity, and setting up new topics to redirect attention from a crisis.

While the majority of IRT research considers the image repair efforts of offenders/perpetrators (Benoit, Citation2015a), third parties may also engage in restoration efforts, including in ongoing crises (i.e. contemporary third-party image repair; Benoit, Citation2015b). Such efforts are common in sporting contexts as fans act as surrogates for their teams during crises, whether it be in response to violations of sporting rules (e.g. amateurism transgressions; Brown & Billings, Citation2013; Cranmer et al., Citation2023) or serious, illegal activities (e.g. Penn State’s sex abuse scandal; Brown, Brown, & Billings, Citation2015). These studies demonstrate that third parties engage in image repair online and utilize the traditional IRT message strategies, but also construct complex frameworks that may both blame and spare some entities of an organization (e.g. fans vilified Penn State and sought to restore Joe Paterno’s reputation; Brown et al., Citation2015). Third-party image repair offers advantages in image restoration: third parties may be viewed as less biased, can access messaging strategies not available to perpetrators, and the confluence of multiple sources and strategies enhances the efficacy of restoration (Benoit, Citation2015b). We argue that these advantages explain why state and non-state actors use inauthentic influence operations to create the illusion of organic third-party image repair efforts. As a faux third-party, state-directed accounts speak with an authenticity that publicly affiliated accounts may lack. That authenticity is an illusion but is difficult for casual social media users to identify.

The Morey affair presents a unique opportunity for the application of IRT. Morey’s tweet presented a crisis for the PRC, whose statecraft prioritizes territorial sovereignty and uses social media platforms in its cultivation of public perceptions. It would stand to reason that Twitter discourse about Daryl Morey and Hong Kong would be ideal for deploying trolls to give the illusion of an organic, third-party restoration effort on behalf of the PRC. PRC trolls, however, may be identifiable in their mirroring of Chinese patterns of image restoration. Moreover, Morey’s apology introduces an opportunity to consider how statecraft and image repair unfold longitudinally and whether trolls’ efforts sway public opinion. Disinformation campaigns have strategic priorities, which are the minimization of face threats through an offender’s position reversal and favorable shifts in discourse from authentic accounts. Shifts in non-troll discourse would be evidence of self-censorship and/or the persuasive effectiveness of a PRC disinformation campaign (Strudwicke & Grant, Citation2020; Zannettou et al., Citation2019), whereas shifts in the image repair strategies of trolls may reveal how the satiation of campaign goals alter the strategic cultivation of public perceptions (Vesselkov et al., Citation2020). Thus, we inquire:

RQ2: How does discourse around Daryl Morey’s tweet about Hong Kong differ as a Function of timing (pre/post apology) and troll status?

Methods

Sample and procedure

The sample consisted of 163,549 tweets posted between October 4th and 10th, 2019, the week of Morey’s original tweet. These included direct replies to Daryl Morey and tweets, retweets, and quote tweets which included @dmorey. Twitter data were pulled in mid-October 2019 using Saleforce’s Social Studio. The data contained the contents of tweets, the time of post, likes, retweets, followers of commenters, and the number of updates taken by each account.

Data analysis

To generate an understanding of the responses to Daryl Morey’s Hong Kong tweet (RQ1), a randomized subsample of 5,800 tweets was drawn. These tweets were read repeatedly to develop an intimate understanding of their contents. Afterward, data were examined through four types of coding over three coding cycles (Saldaña, Citation2015). Coding comprised a line-by-line analysis of tweets and the use of analytic memos to note impressions. Within the first cycle coding, initial coding separated comments based on similarities/differences and was open to all theoretical directions, whereas process coding identified functions taken within comments. The first cycle produced nine codes. In second-cycle coding, pattern coding refined and collapsed codes based on shared similarities and related actions into six categories of responses. Two independent coders were given a codebook consisting of these six categories and trained in its application with an independent set of 300 randomly drawn tweets. After demonstrating acceptable levels of agreement using Cohen’s Kappa (κ > .80), coders independently examined the 5800 tweets and assigned a code to each tweet. The coding scheme applied well to the data based on intercoder agreement (κ = .87). All disagreements were resolved through discussion and consultation with the codebook. Finally, researchers engaged in elaborative coding, which deductively applies existing typologies to data and identified IRT strategies within existing categories.

To answer RQ2, researchers leveraged the 5800 hand-coded tweets and applied natural language processing (i.e. artificial intelligence) to the corpus of 163,549 messages. Automated coding constituted a natural language classification task; hand-coded data were treated as mutually exclusive message classes to be predicted from the language of comments. A machine learning approach was utilized, with hand-coded tweets training a classification algorithm to be competent at the coding task. The model predicted the probability that the tweet represents each possible code, with the total probability summing to one.

The starting point for our classifier was Bertweet – a general-purpose deep-learning language model trained on roughly 850M English language tweets (Nguyen et al., Citation2020). The huggingface library (Wolf et al., Citation2019) was utilized to fine-tune the classifier, using the hand-coded sample. The model was trained on a random sample of approximately 4000 messages, which was stratified such that the overall shares of messages in each code level and in the periods of time before and after Morey’s apology were preserved. The remaining tweets were used to evaluate the model accuracy with the three metrics of code-level performance (Powers, Citation2020): Precision: the percentage of messages predicted to have a certain code that were that code, Recall: the percentage of messages of a certain code that were predicted to have that code, and F1: the harmonic mean (product over arithmetic mean) of precision and recall. The predicted probabilities were converted into predicted codes by taking the highest-probability code. Only four categories from RQ1 were utilized in subsequent analyses due to sufficient samples to perform the evaluation.

The natural language classifier predicted codes with an overall accuracy of 78% on the 1,000 messages in the evaluation set. The model demonstrated good performance for the categories promoting PRC image (Precision: 78%, Recall: 84%, and F1: .81), attacking Morey (Precision: 73%, Recall: 77%, and F1: .75), and promoting democracy & Morey (Precision: 86%, Recall: 85%, and F1: .86). The model performed poorly for remaining categories, classified as ‘other’ due to the small number of comments in those categories (Precision: 47%, Recall: 12%, and F1: .19). The three well-performing categories were used to address RQ2, with the remaining categories collapsed into a category of ‘other.’

Given Social Studio does not report the account creation date (i.e. an indicator of inauthentic activity [Strick, Citation2021]), the number of actions taken for each account – known as updates – was utilized as a proxy troll identifier. The distribution for updates across all accounts at the time of the first tweet revealed a positively skewed distribution with a noticeable elbow at 60 updates, which was utilized as the cutoff point for accounts labeled as likely trolls (35% of all accounts), and a natural rate of growth after.

Results

Responses to Daryl Morey

The first research question explored responses to Daryl Morey’s tweets about Hong Kong. The coding procedures produced six categories of responses. Two of these categories (promoting PRC image and attacking Daryl Morey) comprised 68.81% of the data and constituted image repair on behalf of the PRC – validating the IRT framework. The remaining categories featured comments promoting democracy and Morey, questioning NBA policy, discouraging politicization, and indiscernible/irrelevant statements. Each category is described below, and exemplars are featured in with identifiers (1–5,800).

Table 1. Responses to Daryl Morey’s tweet about Hong Kong.

The most common category comprised comments promoting PRC image (n = 2,195, 37.84%). The image repair strategies utilized within the discourse around Morey aligned with the cultural values of saving face and avoiding risks (Yu & Wen, Citation2003) and were consistent with previous research on Chinese entities (Hu & Pang, Citation2018; Peijuan et al., Citation2009; Wen et al., Citation2009; Zhang & Benoit, Citation2009), with the absence of denial as a notable exception. The image repair strategies within the data included the evasion of responsibility via provocation and reducing offensiveness through bolstering, barnacle, and redirection.

The reliance on provocation was widespread and justified the state-initiated crackdowns on protesters with accusations that Hong Kong protesters were violent terrorists. The acts attributed to protesters included committing arson, rioting, blocking traffic, stealing, beating vulnerable people (e.g. elders), and raping PRC citizens. Such acts were sometimes framed as antithetical to a well-functioning state and necessitating intervention. Efforts to bolster were observed less frequently but portrayed the PRC as unified, powerful, and destined to control Hong Kong. Two indigenized strategies were also identified. Barnacle, which mitigates crises through the reliance on government policy (Hu & Pang, Citation2018), was notable in comments emphasizing the One China policy and defending Chinese sovereignty. These comments place Hong Kong within the PRC’s purview and interference from outsiders as encroachment. Posts utilized redirection by shifting attention toward America’s own social problems or troubled history (e.g. gun violence, social injustice, or militarism). Some of these efforts praised 9/11 and Osama Bin Laden (mentioned 193 times), utilized racial epithets and racialized dialogue and encouraged the succession of states or the reclaiming of U.S. lands by indigenous peoples.

The second category (n = 1,796, 30.97%) consisted of comments attacking Daryl Morey, including through dehumanization, identity-based insults, or threats against him and his family. Although attacking accusers is a sub-strategy for reducing the offensiveness of a crisis, two considerations informed its treatment as a separate category: it constituted nearly a third of data and a minority of comments criticized Morey for apologizing (i.e. antithetical to repairing the PRC’s image). A majority of this category relied on personal insults and/or racial epithets, including Chinese slang that dehumanizes individuals and implies stupidity, laziness, bias, or ignorance – undermining Morey’s credibility. The specific phrase ‘White pig’ – which is Chinese internet slang for anti-Chinese Westerners – was used 48 times and infers bias. Other combinations of identity-based (e.g. White or American) and dehumanizing terms (e.g. dog, trash, or pig) were used frequently. Terms like dog carry innuendos of reliance on an owner’s commands and inability to think independently. Another common Chinese internet expression – NMSL, meaning ‘your mother is dead’ – was utilized 248 times, and threats of either sexual violence or murder were directed at Morey’s female relatives. These threats serve Chinese image repair efforts because they deprive Morey of support and encourage others to avoid making similar statements. A small contingency of attacks was also directed at Morey for apologizing for his initial tweet. Such comments reinforced hegemonic masculinity and referred to Morey as slang for female genitalia or suggested he lacked male genitalia.

A third category of promoting democracy and Morey (n = 1,412, 24.34%) included comments expressing appreciation for Morey’s initial post and the concepts of freedom and democracy. These comments offered praise for Morey’s tweet (e.g. referred to him as a patriot, courageous, real man, or gutsy) and reiterated variations of the phrase ‘stand with Hong Kong.’ A portion of this category also suggested that Morey’s apology was unnecessary. These instances, however, were distinct from the attacking category in that they were void of hostility, still praised Morey’s initial effort, and justified their position with the need to preserve the causes of freedom and democracy. Another secondary trend within this category was that some individuals noted culturally Chinese identities (e.g. from Taiwan, Hong Kong, or mainland China) in conjunction with support for Morey and his initial tweet. Assuming these commenters professed accurate identities, these responses illustrate notable exceptions to past assertions about the collective obligations of face construction in Chinese cultural contexts (Yu & Wen, Citation2003). Finally, a group of comments contrasted democracies with the PRC’s policies and human rights record, drawing parallels to Nazis. These comments equated Mao to Hitler, highlighted the PRC’s use of concentration camps, and used terms like ‘Chinazi,’ which was popularized during the Hong Kong protest movement.

The fourth category featured comments questioning NBA policy (n = 188, 3.24%). These comments raised perceived hypocrisy in how the NBA managed domestic situations associated with freedom of speech or social justice (e.g. moving the All-Star Game from Charlotte in 2015 in response to transgender bathroom legislation) with its stance on the PRC’s human rights record. The contradictions in NBA policy were rationalized as profit-driven and illustrative of China’s economic prowess and sway over American companies (Cha & Lim, Citation2019; O’Connell, Citation2022).

The final discernable category consisted of tweets discouraging politicization (n = 50, .86%). These tweets asserted that Morey inappropriately brought politics into the context of sports. Such connections were inferred based on Morey’s position as general manager of the Rockets, as he tweeted from his personal account and did not reference the NBA or its business with the PRC. This category illustrates that some consume sport as an escape from their everyday lives and their desire for sports and politics remain distinct. Others framed discussing politics as inconsistent with business or social norms, imbuing such statements with impoliteness and cultural ignorance. The remaining comments were indiscernible (e.g. untranslatable; n = 100, 1.72%) or irrelevant to Morey’s tweet or apology (n = 59, 1.02%).

Timing and troll status

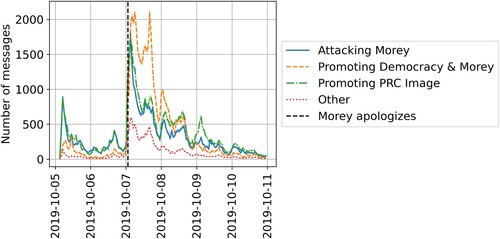

RQ2 considered how responses to Daryl Morey differed as a function of time and troll status. Using the natural language classifier, we binned hourly the predicted number of messages through time for all accounts by category. The number of messages in each category and hour was estimated by summing the predicted probabilities for the category for all messages in that hour. The results demonstrated an initial but limited peak of comments promoting the PRC image and attacking Morey immediately after Morey’s initial tweet, with a massive uptick in conversation following Morey’s apology. See .

Figure 1. Number of Messages in Each Category. Note: Predicted share of messages through time for all accounts by category, binned hourly. 95% confidence intervals are included but too narrow to see on this scale.

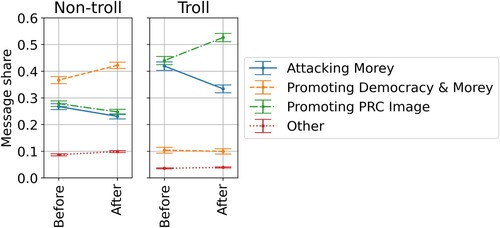

We determined the predicted share of messages by category before and after Daryl Morey’s apology. To account for the correlation of messages from a single source, the shares were estimated by first averaging the message share to the account level before and after the apology and then averaging over accounts. These efforts revealed that, after Morey’s apology, there was an uptick in comments promoting democracy & Morey (95% CI [0.183, 0.194]), but a decline in comments promoting PRC image (95% CI [−0.095, −0.084]) and attacking Morey (95% CI [−0.134, −0.123]). In summary, Morey’s apology resulted in a greater volume of comments and decreases in the proportion of image repair discourse. See .

Figure 2. Change in Message Category Share Before and After Apology. Note: Predicted share of messages by category before and after Morey’s apology. The shares are estimated by first averaging the message share to the account level before and after the apology and then averaging over accounts. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval in the estimated shares.

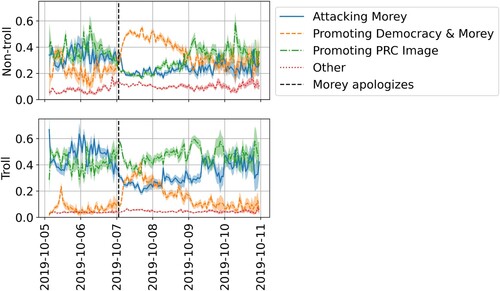

Next, we binned hourly the predicted message shares through time for trolls and non-trolls. The message share was estimated as the average of category probabilities for the messages in each hour and account type (troll vs. non-troll). We conducted an examination of message share estimated as the average of category probabilities for the messages over the corpus and account type (troll vs. non-troll). Findings revealed that trolls were more likely to attack Morey (95% CI [0.103, 0.108]) and engage in promoting the PRC image (95% CI [0.128, 0.133]). Apparent non-trolls were more likely to promote democracy and Morey (95% CI [−0.187, −0.183]). See .

Figure 3. Message Shares by Category Over Time by Troll Status. Note: Predicted message shares through time for trolls and non-trolls, binned hourly and by account type (troll vs. non-troll). Bands represent the 95% confidence interval in the estimated shares.

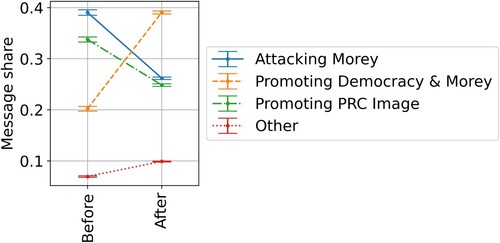

Finally, we determined the predicted share of messages for non-trolls and trolls that were active before and after Morey’s apology. The shares were estimated by first averaging the message share to the account level before and after the apology and then averaging over accounts. These efforts revealed that troll accounts enhanced their promotion of PRC image post-apology (95% CI [0.064, 0.108]) while decreasing attacks on Morey (95% CI [−0.107, −0.064]). Non-troll accounts, however, engaged in greater promoting of democracy and Morey (95% CI [0.038, 0.073]), while utilizing less promotion of PRC image and attacks on Morey (95% CI [−0.045, −0.017]). See .

Discussion

This manuscript offers evidence of a coordinated disinformation operation that sought to benefit the PRC’s image and promote its territorial interests within the discourse surrounding Daryl Morey’s tweet. The PRC’s influence is evident via the confluence of four considerations. First, an excessive number of probable trolls expressed concerns about territorial sovereignty and operated in a manner consistent with past PRC campaigns. Second, the image repair strategies identified were consistent with those implemented by culturally Chinese entities (Peijuan et al., Citation2009; Wen et al., Citation2009; Yu & Wen, Citation2003; Zhang & Benoit, Citation2009), including indigenized strategies (Hu & Pang, Citation2018). Third, troll comments were littered with Chinese internet slang (e.g. NMSL), common insults (e.g. white pigs), and syntax that suggests non-native English speakers. Fourth, linguistically similar Chinese groups (e.g. Hong Kong or Taiwan) would be unlikely to advocate against democracy in Hong Kong, as these efforts equate to the erasure of the autonomy and independence of their own states.

Despite claims about the efficacy of third-party image repair (Benoit, Citation2015b), the PRC faux third-party efforts were largely ineffective at persuading real users about its territorial claims or the justification of its actions. We assert, however, that these trolls may have prioritized depriving Morey of support, socializing observers to avoid criticizing the PRC, and flooding the conversation, making it unnavigable. The image repair efforts of trolls (e.g. attacking Morey, provocation, bolstering, barnacle, and redirection) were consistent with Chinese values and patterns of obfuscation that define image repair in this cultural context (Yu & Wen, Citation2003). Except for provocation, which was infused with disinformation, and barnacle, none of the employed strategies rationalized the actions that sparked protests nor the violations of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration. However, it is logical that the PRC disinformation campaign used an indirect approach and avoided denial and corrective action as documented in literature (Peijuan et al., Citation2009; Zhang & Benoit, Citation2009). The use of denial, corrective action, or mortification would undermine the PRC’s right to control Hong Kong and cede territorial sovereignty at the behest of Western desires – a red line for the PRC (Goldstein, Citation2020). Instead, much of its efforts repeated state-approved scripts (e.g. One China) or insulted Morey with cultural innuendos of bias or ignorance (e.g. white pig or dog) that could easily be overlooked by Western Twitter users.

The longitudinal approach of this study demonstrated the influence of Morey’s apology on genuine discourse and troll strategy. The apology was a turning point that invigorated an otherwise fading conversation. Theoretically, the apology and accompanying rebukes from NBA stakeholders should have fostered more favorable impressions of the PRC (Benoit, Citation2015b) and self-censorship toward challenging territorial claims to Hong Kong (O’Connell, Citation2022). Yet, the data suggested the opposite as authentic accounts rallied to support democracy and Morey. Perhaps this boomerang effect is attributable to the apology being interpreted as disingenuous or coerced. Garnering an apology, trolls shifted strategy, turning from attacking Morey to promoting the PRC image. Within days of the apology, however, trolls returned to attacking Morey, perhaps in response to the increased support from authentic accounts. These shifts indicate trolls have multiple goals and prioritize those goals based on situation factors and broader discourse.

Implications

This study has clear theoretical contributions and extends the scope and understanding of IRT. First, we establish IRT as a useful lens to examine modern disinformation efforts and statecraft – centering a communicative theory within the interdisciplinary ground. We contend that the benefits of third-party image repair (Benoit, Citation2015b) are likely the motivation for state actors who use social media trolls in faux third-party efforts, which is a novel explanation not readily found in disinformation or statecraft literature. Additionally, this extension revealed generalizable support for classical notions about the inefficiencies of evading responsibility and reducing offensiveness, as well as extended such insights to the untested indigenized strategies identified by Hu and Pang (Citation2018). Barnacle and redirection were also ineffective at cultivating favorable impressions of the PRC, at least among those on Twitter. Unlike past literature, which has relied on approaches with limited generalizability (e.g. fictional situations within experiments) or researchers’ subjective evaluations of efficacy (Benoit, Citation2015a; Ferguson et al., Citation2018), this study utilized near population data from a natural and unadulterated setting (at least by researchers). Still, nuance was added via contradictions to classical IRT theorizing, including evidence that traditionally ineffective image repair strategies still offered the benefit of garnering an apology from Morey and that said apology, which should have marked progress toward a restored image, rallied in opposition to the PRC.

Second, this study highlights the importance of cultural context within the image repair process. The extension of IRT to the PRC is noteworthy, as traditional image repair research is largely focused on Western entities (Benoit, Citation2015a; Nekmat et al., Citation2014). Data confirmed the cultural variability of image repair strategies, given indigenized strategies (e.g. barnacle and redirection) were prevalent (Hu & Pang, Citation2018) and trolls relied heavily on Chinese cultural norms and obfuscation (Yu & Wen, Citation2003). The selection of seemingly ineffective tactics and the boomerang of the apology also likely has cultural roots. The PRC is widely noted as an authoritarian regime without free speech (i.e. evident in its responses to public criticism or dissent) and has a historical record of collective punishments. Within such a milieu, responses to violations of social and political norms with image repair strategies that echo state-approved talking points and attacks that extend to kin should be expected. Likewise, the resistance to the PRC’s agenda and additional threats to its image (e.g. comparisons to Nazis) in the wake of Morey’s apology may be due to cultural and political considerations. It is reasonable to assume an authoritarian regime would coerce an apology; indeed, the PRC has responded to similar situations with threats and economic pressure to force apologies (Cha & Lim, Citation2019).

The applied implications of this manuscript rest in meeting the needs of four audiences of stakeholders: (a) social media researchers, (b) public relations and marketing practitioners, (c) political activists employing social media, and (d) organizations operating in the PRC. First, this manuscript forwards a method for researchers to better understand the impact of one form of disinformation campaign in public discourse. Specifically, we demonstrated the practicality of using account updates and machine learning to create profiles associated with troll activity. Social media researchers may use the combination of such techniques to identify and monitor potential trolls and could contextualize their influence in particular conversations for the public via flagging topics or threads as high in troll activity – when such activity is focused and consequential. This work can have important broader implications and may support arguments that social media companies have a vested interest in identifying bad actors operating on their platforms. To this point, troll identification was at the center of Twitter’s $44 Billion lawsuit against Elon Musk and Meta’s recent effort to remove nearly 8000 Facebook accounts associated with Dragonbridge (Agence France-Presse, Citation2023).

Second, many public relations and communication professions rely on the monitoring of social media conversations as part of their services. Social media discourse can feature a sizable presence of inauthentic voices that strategically alter conversation, including for image restoration. Simply, online conversations may not be representative of the perspectives or experiences of authentic users nor specific stakeholders of interest and must not be uncritically accepted at face value. Social media listening software is relied upon heavily by marketing, public relations, and strategic communication firms to engage in brand and image monitoring online, as well as by academic centers to train the next generation of practitioners. However, the assessments of discourse featured in this software (e.g. sentiment, mentions, or topic prevalence) lack the ability to denote the distinct motives, goals, and conversational approaches of stakeholder groups. Communication practitioners need to develop more advanced means of analysis to navigate modern digital landscapes (e.g. using big data, longitudinal approaches, or account characteristics), especially when examining politically or culturally relevant conversations. Context is vital, and that means we must be able to differentiate types of accounts and give analysts the information they need to interpret authentic public responses.

Third, political stakeholders and activists who hope to shape discourse and (in turn) policy may benefit from these insights. Although this study demonstrates that the actions of trolls may have rallied opposition, the PRC’s online influence and faux third-party image repair efforts contributed to a successful outcome (i.e. Morey apologized and the NBA publicly supported China’s authority over Hong Kong). While in this case, the PRC’s campaigns are inauthentic, similar flooding activity can be engaged in openly, authentically, and ethically and may be of use to political actors as a means of disruption. In the past, such ethical flooding has been similarly successful. For instance, in 2020, a coordinated effort to flood the hashtag #WhiteLivesMatter during protests over the murder of George Floyd rallied a global community of support and disrupted racist voices (Lee, Citation2020). With this in mind, we reframe flooding as merely a tool in discourse; one that can be used to fight disinformation as well as promote it.

Fourth, the broader story of Morey’s Hong Kong tweet has a range of potential lessons for sporting practitioners and organizations who operate in the PRC. Sports leagues desire to grow their markets and China offers the world’s largest untapped consumer market, but this access comes with strings. The PRC’s disinformation campaign in response to Morey was a form of public chastisement and communicated to the NBA and other foreign businesses what the PRC views as inappropriate conduct. It may be tempting to ignore trolls, but they still represent the positions and preferences of the PRC – a stakeholder that contributes billions in annual revenue to the NBA. Given the NBA’s quick capitulation and Morey’s chastened apology, China’s tactics of faux third-party image repair worked, even if they failed to alter the public sentiment in the manner desired by the PRC. Such capitulations also ensure that such bullying tactics continue and perhaps become more invasive (Cha & Lim, Citation2019). If the NBA wishes to resist the PRC’s influence, it may attempt to leverage its cultural appeal in China to put pressure on the PRC to accept dissent and freedom of expression. Censorship or bans on the NBA also deprive PRC citizens of a source of leisure-time entertainment and may inspire discontent. These efforts may be assisted by framing dissent in humanitarian as opposed to political terms to diffuse tensions. Basketball is a powerful cultural institution in China with incredible popularity.

Limitations and future directions

Case studies are limited in scope as data are context specific. Twitter, while the site of much of the Morey discourse, is not among the 10 largest social media platforms by active users. The PRC’s disinformation efforts (e.g. Dragonbridge) target an array of social media platforms and their approaches and efficacy may vary as a function of user demographics and platform affordances. The assignment of troll status was probabilistic and necessarily imperfect. Still, this study offers an empirically grounded approach to classifying accounts (i.e. troll and non-troll) that produced statistically significant differences in behaviors that were also consistent with theoretical understandings of trolls (Zannettou et al., Citation2019). This method for classifying troll accounts may not be ideal in other cases, however, as tactics differ among actors and situations. A confluence of account creation dates and updates with abnormal patterns in posts may be most productive in troll identification.

There remains much fertile ground for scholarly exploration. A constellation of concepts (e.g. disinformation, trolls, bots, and hooliganism) focused on coordinated and nefarious communication is gaining attention (Cook et al., Citation2023). Intersections between motives, tactics, channels, authenticity, and concerns for reputation require future consideration. Regarding state-sponsored disinformation campaigns, scholars should consider the approach of this manuscript in identifying trolls and considering discourse as unfolding over time and varying by stakeholder groups. By isolating likely authentic accounts, researchers gain inference into the effects trolls have on the public, which have been difficult to quantify to this point (Zannettou et al., Citation2019). Machine learning also proved a valuable tool for organizing data and revealing shifts in troll tactics. Provided the right case study, this approach could quantify shifts in specific disinformation campaigns or image restoration sub-strategies as crises unfold.

Authentic online experiences require greater awareness and understanding of disinformation efforts, including the sources, goals, strategies, and hallmarks of trolls. State and non-state actors alike have the capacity to disrupt discourse, cultivate perceptions, or undertake fraud by creating online voices from whole cloth. The affordances of social media (e.g. anonymity and ease of targeting topics) offer clear benefits for its use as an inexpensive tool of influence and image construction (Linvill & Warren, Citation2020). In the case of the PRC, such tactics have increased in both scope and regularity since the collection of this data (Myers et al., Citation2022; Sganga, Citation2022; Strick, Citation2021). Communication scholars are well positioned to continue to address this important issue that has increasingly defined the flow of information and social interaction in our society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2023.2300250)

Notes

1 After personal correspondence with Daryl Morey, the authors recognize that Mr. Morey objects to characterizing his second statement as an apology, as he intentionally sought to avoid apologizing under great pressure. He also wished to draw attention to The Wall Street Journal's retraction of a reference to his statement as an apology from a November 19 editorial entitled “On China, Women's Tennis Beats the NBA.” The authors, however, use the term apology in a manner consistent with broad understandings of apologia, image repair, and Scher and Darley's (1997) conceptualization of an apology as a communicative act that seeks to remedy a social disruption. Various additional considerations also informed our language, including (a) O'Connell's (2022) use of the term in his account of the case study and in the outlining of the sport-related statecraft process (i.e., the framework from which this study builds), (b) legacy media's coverage of the statement as an apology (New York Times, National Public Radio, CBS, NBC, BBC, and CNBC), (c) the social construction of the statement as an apology within the public discourse featured in this article, and (d) the statement's focus on acknowledging and mitigating offense that may have been incurred by Rocket fans and friends who reside in China.

References

- Al-Rawi, A., & Rahman, A. (2020). Manufacturing rage: The Russian Internet Research Agency’s political astroturfing on social media. First Monday, 25(9), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v25i9.10801

- Benoit, W. L. (1995). Accounts, excuses, and apologies: A theory of image restoration strategies. Marcombo.

- Benoit, W. L. (2015a). Accounts, excuses, and apologies: Image repair theory and research (2nd ed.). State University of New York Press.

- Benoit, W. L. (2015b). Third party image repair. In Accounts, excuses, and apologies: Image repair theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 97–122). State University of New York Press.

- Berkowitz, P., Gjermano, G., Gomez, L., & Schafer, G. (2007). Brand China: Using the 2008 Olympic Games to enhance China's image. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 3(2), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000059

- Bie, B., & Billings, A. C. (2015). “Too good to be true?”: US and Chinese media coverage of Chinese swimmer Ye Shiwen in the 2012 Olympic Games. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(7), 785–803. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690213495746

- Billings, A. C., MacArthur, P. J., Licen, S., & Wu, D. (2009). Superpowers on the Olympic basketball court: The United States versus China through four nationalistic lenses. International Journal of Sport Communication, 2(4), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2.4.380

- Brown, N. A., & Billings, A. C. (2013). Sports fans as crisis communicators on social media websites. Public Relations Review, 39(1), 74–81. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.09.012

- Brown, N. A., Brown, K. A., & Billings, A. C. (2015). May no act of ours bring shame” fan-enacted crisis communication surrounding the Penn State sex abuse scandal. Communication and Sport, 3(3), 288–311.

- Cha, V., & Lim, A. (2019). Flagrant foul: China’s predatory liberalism and the NBA. The Washington Quarterly, 42(4), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1694265

- Cohen, B., Wells, G., & McGinty, T. (2019, October 16). How one tweet turned pro-China trolls against the NBA. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-one-tweet-turned-pro-china-trolls-against-the-nba-11571238943?utm_source = newsletter&utm_medium = email&utm_campaign = newsletter_axioscodebook&stream = technology

- Cook, C. L., Karhulahti, V. M., Harrison, G., & Bowman, N. D. (2023). Trolligans: Conceptual links between trolling and hooliganism in sports and esports. Communication & Sport. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1080/21674795231153005

- Cranmer, G. A., Boatwright, B., Mikkilineni, S., & Fontana, J. (2023). Everyone hates the NCAA: The role of identity in the evaluations of amateurism transgressions: A case study of the chase young loan scandal. Communication & Sport, 11(3), 634–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795211009162

- deLisle, J. (2020). Foreign policy through other means: Hard power, soft power, and China’s turn to political warfare to influence the United States. Orbis, 64(2), 174–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2020.02.004

- Drumheller, K., & Kinsky, E. S. (2021). Rushing to respond: Image reparation and dialectical tension in crisis communication in academia. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 49(4), 406–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2021.1896021

- Ehrett, C., Linvill, D. L., Smith, H., Warren, P. L., Bellamy, L., Moawad, M., … Moody, M. (2022). Inauthentic newsfeeds and agenda setting in a coordinated inauthentic information operation. Social Science Computer Review, 40(6), 1595–1613. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211019951

- Ferguson, D. P., Wallace, J. D., & Chandler, R. C. (2018). Hierarchical consistency of strategies in image repair theory: PR practitioners’ perceptions of effective and preferred crisis communication strategies. Journal of Public Relations Research, 30(5-6), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2018.1545129

- France-Presse, A. (2023, August 29). Meta fights sprawling Chinese spamouflage operation. Voa News. https://www.voanews.com/a/meta-fights-sprawling-chinese-spamouflage-operation/7246057.html

- Freelon, D., Bossetta, M., Wells, C., Lukito, J., Xia, Y., & Adams, K. (2020). Black trolls matter: Racial and ideological asymmetries in social media disinformation. Social Science Computer Review, 40(3), 560–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320914853

- Goldstein, A. (2020). China’s grand strategy under Xi Jinping: Reassurance, reform, and resistance. International Security, 45(1), 164–201. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00383

- Guo, S., Billings, A. C., Brown, K. A., & Vincent, J. (2023). The Tweet heard round the world: Daryl Morey, the NBA, China, and attribution of responsibility. Communication & Sport, 11(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479520983254

- Hu, Y., & Pang, A. (2018). The indigenization of crisis response strategies in the context of China. Chinese Journal of Communication, 11(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2017.1305978105

- Huang, F. (2013). Glocalisation of sport: The NBA’s diffusion in China. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 30(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.760997

- Kagubare, I. (2022, October 26). Pro-Chinese disinformation group attempts to undermine US political system, influence voters: report. The Hill. https://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/3704593-pro-chinese-disinformation-group-attempts-to-undermine-us-political-system-influence-voters-report/

- King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2017). How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument. American Political Science Review, 111(3), 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000144

- Koch, N. (2013). Sport and soft authoritarian nation-building. Political Geography, 32(2013), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.11.006

- Kurlantzick, J. (2022, December 5). China wants your attention please. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/05/chinese-state-media-beijing-xi-influence-tools-disinformation/

- Lee, A. (2020, June 8). K-pop fans are taking over ‘White Lives Matter’ and other anti-Black hashtags with memes and fancams of their favorite stars. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/04/us/kpop-bts-blackpink-fans-black-lives-matter-trnd/index.html

- Linvill, D. L., & Warren, P. L. (2020). Troll factories: Manufacturing specialized disinformation on Twitter. Political Communication, 37(4), 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1718257

- Linvill, D. L., & Warren, P. L. (2021, December 21). Understanding the pro-China propaganda and disinformation tool set in Xinjiang. Lawfare. https://www.lawfareblog.com/understanding-pro-china-propaganda-and-disinformation-tool-set-xinjiang

- Lukito, J. (2019). Coordinating a multi-platform disinformation campaign: Internet Research Agency activity on three U.S. social media platforms, 2015 to 2017. Political Communication, 37(2), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1661889

- Mozur, P., Zhong, R., Krolik, A., & Aufrichtig, A. (2021, December 13). How Beijing influences the influencers. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/12/13/technology/china-propaganda-youtube-influencers.html

- Myers, S. L., Mozur, P., & Kao, J. (2022, February 18). Bots and fake accounts push China’s vision of winter Olympic wonderland. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/18/technology/china-olympics-propaganda.html

- Nekmat, E., Gower, K. K., & Ye, L. (2014). Status of image management research in public relations: A cross-discipline content analysis of studies published between 1991 and 2011. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 8(4), 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2014.907575

- Nguyen, D. Q., Vu, T., & Nguyen, A. T. (2020). BERTweet: A pre-trained language model for English Tweets. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.10200.

- Nisbet, M. C. (2010). Knowledge into action: Framing the debates over climate change and poverty. In P. D'Angelo & J. A. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis (pp. 59–99). Routledge.

- O’Connell, W. D. (2022). Silencing the crowd: China, the NBA, and leveraging market size to export censorship. Review of International Political Economy, 29(4), 1112–1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1905683

- Ostler, S. (2022, August 2). Benefits of NBA-China partnership? Well, there’s the money. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/sports/ostler/article/Benefits-of-NBA-China-partnership-Well-17346978.php#:~:text = The%20NBA%20makes%20roughly%20%245%20billion%20a%20year%20from%20China

- Paul, K. (2020, June 11). Twitter suspends Chinese operation pushing pro-Beijing coronavirus messages. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/china-twitter-disinformation-idCNL8N2DO5UP

- Pearce, K. E. (2015). Democratizing kompromat: The affordances of social media for state-sponsored harassment. Information, Communication & Society, 18(10), 1158–1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1021705

- Peijuan, C., Ting, L. P., & Pang, A. (2009). Managing a nation's image during crisis: A study of the Chinese government's image repair efforts in the “Made in China” controversy. Public Relations Review, 35(3), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.05.015

- Powers, D. M. (2020). Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.16061.

- Ruwitch, J. (2020, July 30). Hong Kong police take steps to enforce controversial national security law. NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/2020/07/30/897066273/hong-kong-police-take-steps-to-enforce-controversial-national-security-law

- Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Sganga, N. (2022, October 26). China-linked influence campaign targeting U.S. midterms, security firm says. CBSNews. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/dragonbridge-china-us-midterm-elections-influence-campaign-mandiant/

- Strick, B. (2021). Analysis of the pro-China propaganda network targeting international narratives. Centre for Information Resilience. https://www.info-res.org/post/revealed-coordinated-attempt-to-push-pro-china-anti-western-narratives-on-social-media

- Strudwicke, I. J., & Grant, W. J. (2020). #Junkscience: Investigating pseudoscience disinformation in the Russian Internet Research Agency tweets. Public Understanding of Science, 29(5), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520935071

- United States of America v. Internet Research Agency LLC. (2018). District of Columbia. https://www.justice.gov/file/1035477/download

- Vesselkov, A., Finley, B., & Vankka, J. (2020). Russian trolls speaking Russian: Regional Twitter operations and MH17. WebSci ‘20: Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference of Web Science, https://doi.org/10.1145/3394231.3397898

- Walter, D., Ophir, Y., & Jamieson, K. H. (2020). Russian Twitter accounts and the partisan polarization of vaccine discourse, 2015–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 110(5), 718–724. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305564

- Wei, F., Hong, F., & Zhouxiang, L. (2010). Chinese state sports policy: Pre-and post-Beijing 2008. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 27(14–15), 2380–2402. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2010.504583

- Wen, W. C., Yu, T. H., & Benoit, W. L. (2009). Our hero Wang can't be wrong! A case study of collectivistic image repair in Taiwan. Chinese Journal of Communication, 2(2), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750902826707

- Wojnarowski, A., & Lowe, Z. (2020, October 28). NBA revenue for 2019–20 season dropped 10% to $8.3 billion, sources say. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/30211678/nba-revenue-2019-20-season-dropped-10-83-billion-sources-say

- Wolf, T., Debut, L., Sanh, V., Chaumond, J., Delangue, C., Moi, A., Cistac, P., Rault, T., Louf, R., Funtowicz, M., & Davison, J. (2019). Huggingface’s transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.03771.

- Youngmisuk, O. (2019, October 14). Lebron James: Daryl Morey was “misinformed” before sending Tweet about China and Hong Kong. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/27847951/daryl-morey-was-misinformed-sending-tweet-china-hong-kong

- Yu, T., & Wen, W. (2003). Crisis communication in Chinese culture: A case study in Taiwan. Asian Journal of Communication, 13(2), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292980309364838

- Zannettou, S., Caulfield, T., DeCristofaro, E., Sirivianos, M., Stringhini, G., & Blackburn, J. (2019). Disinformation warfare: Understanding state-sponsored trolls on Twitter and their influence on the web. In L. Liu and R. White (Eds.), Companion proceedings of the 2019 world wide web conference (pp. 218–226). Association for Computing Machinery.

- Zhang, A., & Cave, D. (2022, June 3). Smart Asian women are the new targets of CCP global online repression. The Strategist. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/smart-asian-women-are-the-new-targets-of-ccp-global-online-repression/

- Zhang, E., & Benoit, W. L. (2009). Former Minister Zhang’s discourse on SARS: Government's image restoration or destruction? Public Relations Review, 35(3), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.04.004