Abstract

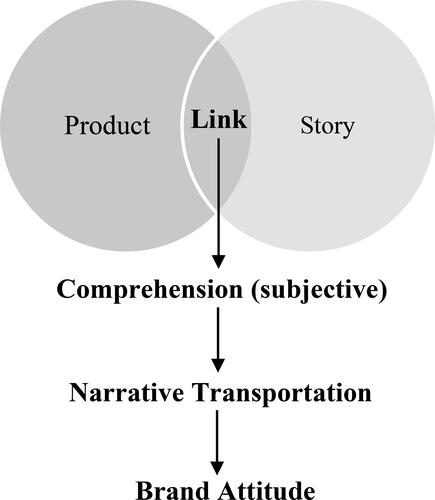

Story advertisements combine entertainment and persuasion. To persuade effectively these ads must meaningfully link the story with the product. A disconnect between story and product has a negative effect on persuasion. The link between product and story is essential because it helps viewers comprehend meaning, which is embedded in the story. In story ads subjective comprehension of meaning is necessary for an unhindered immersion in the story ad, which in turn drives persuasion. Thus, we extend the transportation-imagery model in a narrative ad context. We outline a taxonomy of types of product–story link and, based on it, create an index to make the link measurable and test the hypotheses. Study 1 empirically validates the index and Study 2 applies the index to test the model empirically. Study 3 employs an experimental design that manipulates strength of product–story link while keeping the ad’s story structure stable. We find evidence that the positive effect of product–story link on brand attitude is mediated by subjective comprehension and narrative transportation. This finding indicates the importance of linking the story with the product to obtain maximum impact and discourages the advertising practice of loose links. Further theoretical and managerial implications are discussed.

Advertisements that use a story to convey their message are more persuasive than ads that relay their message in a nonstory format, though under certain conditions stating only hard facts without embedding them in a story can be more persuasive (Adaval and Wyer 1998; Kim, Ratneshwar, and Thorson 2017; Krause and Rucker 2020). Still, the idea that relaying a persuasive message as a story serves as a panacea for more communication impact is often encountered, exemplified by the aura that surrounds the buzzword “storytelling” in some discourses. This does injustice to the intricacies and importance of designing persuasive stories around products conscientiously to achieve maximum impact.

Stories, also called narratives, are a persuasive (Braddock and Dillard Citation2016; van Laer et al. Citation2014) and powerful tool to capture the attention of consumers (Aaker Citation2018), which is especially relevant in a world where consumers can now more easily avoid advertising (e.g., Fransen et al. Citation2015; Jeon et al. Citation2019) and divide their attention among multiple tasks (Duff and Segijn Citation2019). Still, a mere focus on telling a story has generated story ads where integration of the product into the story seems like an afterthought. We have all seen story ads where the product is at best loosely connected to the ad story, maybe even actively asking ourselves how the product is related to the story, making the product offering an alien element in it (e.g., soft drink/gunfight scene: Dr Pepper; restaurant coupons/Tibetan culture: Groupon; fast food/gym: KFC). Also, research has hinted at the disappearance of the product in story ads (Stern Citation1994a) while there is evidence that making consumers focus on the process of product usage or consumption in story ads is advantageous (Escalas Citation2004a). Although the disappearance of the product in the story ad is not necessarily problematic in itself, a truly weak link between product and story constitutes an issue for the effectiveness of story ads, lowering engagement with the ad and its persuasive impact.

Engagement with stories is conceptualized as immersion in the story, an experience called narrative transportation, which is also the primary mechanism of persuasion in narratives according to the transportation-imagery model (Green and Brock Citation2000, Citation2002). Narrative transportation describes the experience of focusing all mental faculties on the narrative, thereby vicariously experiencing, for example, a movie, a book, or even a short video commercial, for a temporary period of time (Dessart Citation2018; Gerrig Citation1993; Green and Brock Citation2000; Kaufman and Libby Citation2012).

Comprehension of meaning is essential for narrative transportation in story ads, also called narrative ads, because it allows for unhindered immersion in the mentally constructed narrative world (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008; Escalas Citation2004a; Gerrig Citation1993). When processing narrative ads, comprehension of how the story (e.g., events, characters) relates to the product is necessary (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008; Escalas Citation2004b). Therefore, we argue that neglecting the link between product and story is detrimental in terms of persuasion. The reason is that a weak link between product and story makes it difficult for consumers to understand meaning conveyed by the story, which disrupts the narrative transportation experience. Thus, the derived process is as follows: The strength of the link between story and product affects comprehension of meaning, which influences narrative transportation, which in turn impacts persuasion. Therefore, narrative advertisements that insufficiently establish the link between story and product are less persuasive.

The investigation of product–story link contributes to literature that extends insights about the transportation-imagery model in a narrative ad context (e.g., An et al. Citation2020; Escalas Citation2004a) and builds on literature at the intersection of story ad, product, and comprehension of narratives (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008; Escalas Citation2004a; Escalas Citation2004b). Complementarily, recent scholarship has highlighted the need for research in extending the transportation-imagery model with regard to factors that affect narrative transportation in narrative ads (Zheng, Phelphs, and Pimentel Citation2019).

Product–story link extends the transportation-imagery model in a narrative advertising context, showing how this link impacts transportation, which we illustrate by (1) creating an index to measure the link between product and story through examination of previous literature and real-life examples of narrative video ads and validate the index in a study and (2) then illustrating in a survey and an experiment how product–story link impacts subjective comprehension, narrative transportation, and, finally, brand attitude. Consequently, this research sheds light on a message characteristic that impacts the persuasiveness of narrative ads and has implications in terms of narrative message design. Advertisers are advised to pay special attention to how the product is related to the story, taking a holistic perspective—and not a compartmentalized approach—to storytelling about products.

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

Narrative Transportation Theory and Advertising

Communication messages in a story format are a regular occurrence in our daily lives. Every time we narrate our experiences, we tell a story. When we watch a drama or read a novel, we are exposed to stories. A story, being commonly used synonymously with the term narrative in past literature, includes characters, exhibits a causal structure and thus follows a form of chronological pattern (Escalas and Stern Citation2003; Green and Brock Citation2000; Krause and Rucker 2020; van Laer et al. Citation2014).

The narrative communication format has also found its way into advertising practice, namely as narrative advertisements, which have been the continued subject of advertising research (e.g., Deighton, Romer, and McQueen Citation1989; Dessart Citation2018). Narrative ads were shown to have certain advantages, such as their persuasive potential often surpassing that of nonnarrative ads (Adaval and Wyer Citation1998; Kim, Ratneshwar, and Thorson Citation2017). However, under certain conditions, such as embedding strong facts in a story (Krause and Rucker 2020) or a high level of perceived manipulative intent (Wentzel, Tomczak, and Herrmann Citation2010), narratives lose their advantage.

One reason for the widely illustrated persuasive potential of narratives in various contexts and fields (Braddock and Dillard Citation2016; Shen, Sheer, and Li Citation2015; van Laer et al. Citation2014) is that narrative ads invoke less cognitive elaboration of arguments and fewer negative cognitive responses (Escalas Citation2007; Krause and Rucker 2020). These findings also reflect the notion that information processing of narratives requires relatively high amounts of cognitive resources (Chang Citation2009a). This narrative processing is linked to the persuasive mechanism induced by narrative texts, which is called narrative transportation (Escalas Citation2004b, 2004a, Citation2007; Green and Brock Citation2000).

In addition, transportation into narratives was illustrated to elicit strong affective responses (van Laer et al. Citation2014) and to be related to identification with characters (e.g., Shen et al. Citation2017), which also contributes to their persuasive impact. And while it is true that narrative texts can lead to narrative transportation, other types of advertisements can as well: short narrative video ads (Dessart Citation2018), mini-film advertisements (Karpinska-Krakowiak and Eisend Citation2020), narrative print ads (Escalas Citation2004a), narrative reviews (van Laer et al. Citation2018), and even mere images (Phillips and McQuarrie Citation2010).

Thus, according to the transportation-imagery model, stories persuade through narrative transportation (Green and Brock Citation2000, Citation2002). As individuals are transported into a narrative, they become influenced by this experience. Metaphorically speaking, transportation into narrative worlds is like a journey from which the individual, like a traveler, “returns to the world of origin, somewhat changed by the journey” (Gerrig Citation1993, p. 11).

A recent overview of literature on the application of the transportation-imagery model in the narrative ad context identified three types of factors that impact transportation, namely, message factors, individual factors, and environmental factors (Zheng, Phelphs, and Pimentel Citation2019). The investigation of product–story link in narrative ads is a message factor influencing transportation, which could be considered a factor on the storyteller side (van Laer et al. Citation2014). Such message factors are under control of the advertiser who is responsible for the ad. Therefore, message factors are very suitable for implementation because they can be actively designed by the communicator to increase the impact of the message, while active management of story receiver characteristics and environmental conditions is more restricted.

Products in Narrative Ads

The final goal of advertising is to persuade consumers to purchase a product offering. In nonnarrative ads the message is often designed straightforwardly, persuading consumers in an informational, rational way, typically explained by dual process models (e.g., elaboration likelihood model; Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). In contrast, narrative ads persuade through narrative transportation and not through cognitive analytic elaboration, which is outlined in transportation theory and encapsulated in the transportation-imagery model (Escalas Citation2007; Green and Brock Citation2000, Citation2002). Previous research has investigated a variety of factors related to transportation in narrative persuasive messages, for example, the propensity of narrative ads to go viral (Seo et al. Citation2018) and the valence and reflection in cautionary stories (Hamby and Brinberg Citation2016).

Research related to the product in narrative ads illustrated how consumers connect their self-concept to the brand via transportation (narrative processing), leading to persuasion (Escalas Citation2004b), and that instructing consumers to imagine themselves using a product in a narrative print ad increased transportation (Escalas Citation2004a). Such process-focus-centered instructions (Escalas Citation2004a) might have tied the product more intensely to whatever story the consumer was imagining. Generally, consumers need to understand how the product relates to the story (structure and content) for effective transportation, for example, so that story events and characters can be related to product purchase or usage (Escalas Citation2004b).

Given these insights on the product and meaning for consumers in narrative ads (Escalas Citation2004a, 2004b), we expand on the role of the product for the transportation experience in narrative ads while building on research about the comprehension of meaning in narratives from a mental model perspective (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008). Understanding of meaning in narratives is essential for transportation (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008; Gerrig Citation1993). Thus, meaning conveyed by the narrative must be accessible to the story receiver, especially with relation to the product; otherwise, incomprehension will negatively affect the transportation experience. Consequently, product–story link plays a vital role in making meaning comprehensible to the story receiver or, put differently, assuring that the transportation process is not disrupted by a product that represents an inconsistent element in the story (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008).

Product–Story Link Facilitates Comprehension and Narrative Transportation

Narrative ads like other persuasive narrative communication formats merge two aspects into one message: entertainment and persuasion (Slater and Rouner Citation2002). This merger results in a communication message that conveys its meaning in a story. Naturally, this link between product and story in an ad varies because narrative ads convey the persuasive meaning (e.g., value of the product) in different ways. This meaning is then decoded by consumers as they construct meaning from and interpret narratives to comprehend them (Bruner Citation1986). In narrative ads the story is the vehicle for the persuasive message the company wants to send. Consequently, product–story link is crucial because it facilitates comprehension of meaning embedded in the message.

So, when looking at the nature and comprehension of narrative ad messages, two features are relevant for narrative transportation: (1) a narrative ad merges story and persuasive elements in one message (Slater and Rouner Citation2002), in other words, there is no separation in perception between story and product, meaning product–story link is perceived as a characteristic of the narrative; and (2) story receivers try to interpret and understand the information provided in the narrative, which is crucial for transportation (Bartlett Citation1932; Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008; Gerrig Citation1993; Oatley Citation1999b).

The latter point is based on the situation model of narrative comprehension that states when receiving a narrative, individuals construct such a model to represent the story, which contains different elements, for example, people, settings, and objects (Graesser, Singer, and Trabasso Citation1994). It is important that the consumer is able to derive explanatory meaning from the elements in the narrative (Graesser, Singer, and Trabasso Citation1994), for example, answering the causal question of why a product appears in and how it relates to the story. The product–story link should give the answer to this question clearly, because story receivers engage in a “search after meaning” (Stein and Trabasso Citation1985, p. 36). Put differently, a smooth construction of the mental models (i.e., situation model) by the individual implies that inconsistencies in the narrative do not become too blatant (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008). Therefore, a weak link between product and story can constitute an inconsistency in the situation model, which leads to issues in comprehension and a loss of transportation.

Similar to readers who try to infer the intended meaning from a text to achieve comprehension (Bruner Citation1986; Stein and Trabasso Citation1985), consumers try to understand meaning in the story of an ad. As a result, in narrative ads the product–story link constitutes a crucial element of the situation model that establishes cohesiveness between product and story. Moreover, even if the story itself is compelling, a lack of linkage between story and product will reduce the cohesiveness of the narrative message. The reason is that even when coherence is established on a local story level, individuals still try to understand the narrative message as a whole (Graesser, Singer, and Trabasso Citation1994). Yet, to be transported, it is sufficient to achieve subjective comprehension and objective comprehension is not required; for example, it makes sense to the story receiver what the message tries to say, while it is not necessary for the receiver to actually identify the true meaning to immerse in the story.

When (subjective) meaning in a narrative is not well understood, it interferes with the transportation experience (Gerrig Citation1993). Consequently, if product–story link does not contribute to the cohesiveness of the narrative message, difficulties in comprehension follow and the individual will recede from immersion in the ad story. Thus, we postulate that the effect of product–story link on narrative transportation is mediated by subjective comprehension of the meaning of the ad message.

H1: Product–story link has (a) a positive impact on comprehension of meaning, which in turn has (b) a positive effect on narrative transportation, resulting in a mediation of the effect of product–story link on narrative transportation.

Persuasive Effects of Narrative Transportation

The mediation of persuasive effects by transportation in narrative communication messages is well documented (e.g., van Laer et al. Citation2014). Transportation was conceptualized as a state in which several psychological processes converge (Gerrig Citation1993). The main dimensions of transportation in a narrative text are of a cognitive, affective, and imaginative nature (Appel et al. Citation2015), and during transportation all mental faculties become focused on the events happening in the narrative (Green and Brock Citation2000). As the individual converges with the narrative, self-awareness is decreased, making the individual more susceptible to the beliefs embedded in the narrative message (Appel and Richter Citation2010; Kaufman and Libby Citation2012). Further, the persuasive impact of transportation in commercial contexts using narrative ads has been illustrated, like effects on brand attitude and brand evaluations (e.g., Dessart Citation2018; Escalas Citation2004a). In the process, the consumer forms self–brand connections through the transportation experience that positively affect brand attitude (Escalas Citation2004b). Consequently, we expect a mediating role of transportation between comprehension and brand attitude.

H2: Narrative transportation mediates the effect of comprehension on brand attitude.

We posit that the effect of product–story link on brand attitude is mediated by comprehension of meaning and narrative transportation, resulting in a serial mediation (see ).

Conceptual Basis for Empirical Measurement of Product–Story Link

To operationalize and empirically measure product–story link, the various types of integration of a product into a narrative ad must be compiled. First, a broad definition of product–story link based on previous literature serves as a basis for the taxonomy (Russell Citation1998). Therefore, product–story link is seen as the intensity of perceived reference between product and story in narrative ads. Second, the frame of this reference should relate to the narrative structure or content (i.e., causality and characters) to make this link salient and meaningful. For narrative ads, Escalas (2004b) notes the importance of how usage and consumption of the product are related to the story to create meaning. Third, a taxonomy of the types is to be established which is not necessarily mutually exclusive but needs to be collectively exhaustive. This taxonomy allows for a coverage of the content domain of the construct, a valid and versatile measurement, and accounts for the formative nature of the construct.

The taxonomy was established by screening a convenience sample of narrative ads (about 200) to identify different types of product–story link. After deriving several types from the screening, we conducted a literature review to determine whether these types can also be related to appeals or message strategies, beyond narrative ads. In the next sections, the different types of product–story link are discussed, which will serve as a basis to operationalize the items of the construct; summarizes the different types of product–story link.

Table 1. Types of product–story link.

Product Usage

Product demonstration or usage occasions are commonly used in advertising as message appeals and to inform consumers about products (Laskey, Day, and Crask Citation1989). In a narrative context, Escalas (2004a) showed that when consumers were instructed to imagine product usage in narrative ads it was beneficial for transportation. Also, when a consumer views characters in a narrative ad using the product, they might mentally simulate its usage. This happens while being immersed into the story where recipients are subject to vicarious experiencing (Kaufman and Libby Citation2012). Consequently, product usage can improve product–story link, for example, the story shows how the product is to be used.

Problem Resolution

Advertisements have employed problem-resolution appeals widely in the past (Marlowe, Selnow, and Blosser Citation1989). In this case, the product plays the role of a problem solver, which has also been investigated in movies (Yang and Roskos-Ewoldsen Citation2007). Naturally, this type of narrative product link aligns well with the narrative structure of classical ad dramas that build up to the resolution of a problem (Stern Citation1994b). Examples are narrative ads where the protagonists encounter an issue as the plot unfolds, which is then resolved by the product being advertised. Thus, the story sets the scene for the solution provided by the product, linking them closely.

Behavior

Advertisers want their products to be desired by consumers. Desirability in stories is expressed by the actions or attitudes of the characters toward the target product. The product attracts the characters, guides them, or influences their behaviors. In entertainment content, consumers tend to align their attitude toward a product with that of the story character (Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006). Specifically, characters in narrative ads have been identified as targets of sympathy and empathy (Escalas and Stern Citation2003). Therefore, we expect that whatever moves the character will also move the viewer. In this way meaning is generated because the viewer can understand the desirability of the product that the character in the story is feeling. As a result, when a product influences the behavior of the characters in the story, the link between them is intensified.

Narrative–Product Specificity

Unique selling proposition is a classic message strategy that aims to position a brand as unique (Laskey, Day, and Crask Citation1989). From a consumption perspective, a unique product is a product that satisfies a distinct combination of needs and differentiates it from other products. Such uniqueness makes the product (benefits, consumption) irreplaceable in the perception of the consumer. An advertising appeal linked to achieving this is scarcity, which builds upon the desire of consumers for uniqueness (Eisend Citation2008). A narrative ad that aims to communicate uniqueness illustrates a product’s irreplaceableness. Embedding this meaning in the narrative means that the story is so diligently constructed around the product that the viewer cannot imagine the same story with another product. As a result, the story becomes product specific. Therefore, high narrative–product specificity improves product–story cohesiveness and thus deepens the link.

Story Driver

The symbolic value of products is a determining aspect for consumers to make a purchase decision (Gardner and Levy Citation1955). For example, metaphors are a popular and effective way to convey the value of a product in advertising (e.g., Chang and Yen Citation2013). Also, Padgett and Allen (Citation1997) highlight how symbolic and functional meanings can be conveyed with a narrative approach to communicate brand image. The reason is that narrative communications lend themselves to such message goals because consumers construct meaning from the narrative (Bruner Citation1986). Subsequently, the product must serve a developmental function in the narrative; this can be an instrumental role, it could be a helper to unfold the narrative (Yang and Roskos-Ewoldsen Citation2007), or the product might be the key to understanding the narrative (e.g., narrative metaphor ads).

Thus, we delineate two forms that reflect the story driver type of product–story link: (1) the product is necessary for narrative development (similar to being a plot development enabler in Yang and Roskos-Ewoldsen Citation2007) and (2) the product is a functional element that transcends the narrative development itself; it makes the narrative work in terms of meaning reflecting a deeper comprehension aspect. This is well illustrated by narrative metaphor ads where the product plays no part in developing the story line but relays extra meaning. For example, the ad by ERGO (an insurance company) does so at the end; see for an overview of the link types. As the product is linked to the causal chain of the story, the link between product and story is enhanced.

Study 1: Index Construction and Validation

Study 1 uses a survey approach with real video commercials and a consumer sample to validate the index empirically. We follow standard procedures for constructing a formative measurement index.

Method

Stimuli

We selected 12 video commercials that were narrative, used only human characters, used different products, and were altogether likely to cover a wide spectrum of product–story links (see ).

Table 2. Stimuli ads, product–story link, and number of respondents (Study 1).

Sample and Procedure

Master’s students at the University of Vienna collected a consumer convenience sample for course credit by means of an online questionnaire. Upon accessing the questionnaire, respondents were randomly assigned to watch one of the ads. After seeing the ad, respondents answered the measurement items. Transportation and brand attitude were measured before asking about product link to avoid priming effects, which also follows guidelines to move from general to more specific questions in surveys (McFarland Citation1981).

The sample size was N = 663 after removing incomplete questionnaires, cases where data collection was not conducted according to guidelines, and cases where respondents did not pass a functional check to play the video format in their browser (n = 28). The sample had a mean age of 28 years (SD = 8.81); 55% were female. There were no significant differences between the respondents assigned to each commercial in terms of age, F (11, 651) = 0.53, p = 0.883, or gender composition, χ² (11) = 7.14, p = 0.788.

Measurements

We included the short form of the transportation scale (Appel et al. Citation2015; Green and Brock Citation2000; Hamby and Brinberg Citation2016), which was adapted for video commercials (sample item: “I was mentally involved in the story while watching the ad”). We included the measures brand attitude (Lee and Mason Citation1999), product category involvement (Mittal Citation1995), and brand familiarity (Kent and Allen Citation1994) for exploratory purposes. All scales exhibited good internal consistency, α ≥ 0.75. in the appendix gives a complete item list of all studies. Descriptive statistics of Study 1 are exhibited in Table OA1 in the Supplemental Online Appendix.

Product–Story Link Index Construction

The different types of product–story link can contribute independently to the construct. Consequently, the construct is of a formative nature, and we aimed to create an appropriate index. We created seven items for the different types and one additional global statement item for empirical index validation purposes (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer Citation2001; see ). Each type of product–story link was represented by one item except for story driver type. For this type, three items were developed, two reflecting the discussed two subforms and one which was of a more general nature and stressed the decisive role of the product (see ). The global statement item was based on Russell (Citation2002).

Table 3. Product–story link items.

As a first step, we regressed the seven items on the global statement item to identify any issues of multicollinearity in the proposed index. We deleted items from the index when the tolerance was ≤ 0.30. This cutoff level was used in formative index construction in literature to avoid extensive multicollinearity (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw Citation2006). Only one item, story driver (general), was below this threshold of multicollinearity (tolerance = 0.27) and was deleted. Methodologically speaking, this more generally worded item was included to determine whether a distinction in subforms of story driver was empirically meaningful. The empirical results suggest that it is meaningful to differentiate and keep the two items representing each a subform of the story driver type. We then correlated the global statement item with each of the remaining six items following suggested procedures when constructing a formative index (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer Citation2001). All bivariate correlations with the global statement item were significant and therefore all items were retained, p < 0.05.

We further validated the index with a principal component analysis (varimax rotation) evaluating the factor loadings and the total variance explained using the R package “psych” (Revelle Citation2019; R Core Team Citation2020). The assumptions of the analysis were met; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s overall measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) = 0.84; individual item MSA ≥ 0.75; Bartlett’s test: χ² (15) = 1552.7, p < 0.001. One component was extracted (eigenvalue = 3.30; eigenvalue criterion > 1), and the component explained 55% of the total variance. All items had factor loadings of > 0.7 except for one item (usage), loading = 0.31, which constitutes a steep drop in comparison to the other loadings. In addition, loadings < 0.45 are considered poor, and only loadings > 0.32 are commonly interpreted (CitationTabachnick and Fidell 2014). Therefore, usage was deleted from the index. As a result, five items constitute the index of product–story link (see ).

Discussion

Study 1 used a variety of real video commercials and an appropriately large consumer sample to construct and empirically validate the product–story link index. This was a necessary step to be able to measure overall product–story link while accounting for the variety of aspects that might contribute to it. Thus, the index provides a versatile measurement of integration of the product in the story that can be used in a variety of contexts (e.g., different media, narrative persuasive messages that integrate an object). Still, it has been developed with a focus on narrative video commercials, but this was intentional, given the ubiquitousness of video in the life of today’s consumers and the response of marketers to embrace video content (Oziemblo Citation2020; Khabab Citation2020).

Study 2: Test of Hypotheses (Survey)

Study 2 uses the index of product–story link developed in Study 1 to test the research model and associated hypotheses with a survey and a consumer sample.

Method

Design, Procedure, and Stimuli

Study 2 replicates the survey design and general procedure of Study 1 using the same stimuli to test the research model. Respondents were again randomly assigned to one of 12 ads.

Sample

As in the previous study, master’s students at the University of Vienna collected a consumer convenience sample with an online questionnaire. Due diligence was paid to ensure proper data collection. The eligible sample size was N = 686 (Mage = 32, SD = 14.28; 61% were female), after those respondents who did not pass the attention check were excluded (n = 22). Number of respondents per ad (n) was balanced, 54 ≤ n ≤ 59. There were no differences in age, F (11, 673) = 0.85, p = 0.589, or gender distribution across the ads, χ² (11) = 5.36, p = 0.913.

Measurements

In addition to the measures of Study 1, we also administered an adapted three-item measure of subjective meaning comprehension (MacInnis, Rao, and Weiss Citation2002). All scales had good internal reliability, α ≥ 0.78 (see Table OA1 in the Supplemental Online Appendix for descriptive statistics).

Results

Serial Mediation Model

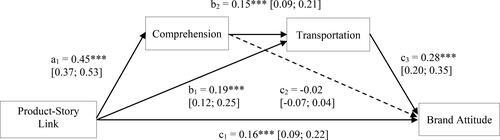

A serial mediation model including control variables was specified in R using the package “lavaan” (Rosseel Citation2012; R Core Team Citation2020). An overview of the results is given in . The effect of product–story link on comprehension is significant, supporting hypothesis 1(a) (a1=0.45, p < 0.001). Comprehension has a significant impact on transportation, providing evidence for hypothesis 1(b) (b2 = 0.15, p < 0.001). In turn, transportation strongly affects brand attitude, supporting hypothesis 2 (c3 = 0.28, p < 0.001). This sequence of indirect effects (a1*b2*c3; see ) from narrative product link to brand attitude is significant as well, β = 0.019, p < 0.001. This finding provides support for the mediating roles of comprehension and narrative transportation. Consequently, the results support hypotheses 1(a), 1(b), and 2.

Figure 2. Overview of serial mediation model estimates (Study 2: survey). Product–story link is represented as a metric variable. The control variables product category involvement and brand familiarity are not included in the figure for aesthetic reasons. See Table OA2 in the Supplemental Online Appendix for the individual regressions and all parameter estimates; ***p < 0.001.

Other paths had to be included to properly estimate the complete serial mediation model specification. The direct effect of product–story link is significant (c1, p < 0.001) as well as its impact on transportation (b1, p < 0.001). In contrast, comprehension has no significant direct effect on brand attitude (c2, p > 0.05).

Discussion

Study 2 tested the research model and illustrates that as product–story link increases, subjective comprehension is enhanced, leading to higher transportation, which in turn has a positive effect on brand attitude. The hypotheses have been supported, providing empirical evidence for the model and the associated mediation effects. The stimuli consisted of a variety of real narrative video commercials, showing the suitability of the index for real narrative advertisements. Therefore, the study shows that product–story link is a relevant factor in narrative ad message design that impacts narrative transportation and thus brand attitude. Still, this study is limited in the sense that we did not manipulate product–story link directly but observed the effects in a variety of narrative ads. This enhances generalizability of the results across different narrative ads, but experimental studies can provide additional evidence for internal validity of an effect. Consequently, we decided to actively manipulate product–story link in a video commercial to provide further empirical evidence of causality of the effect in Study 3. The goal in Study 3 was to manipulate product–story link using a real video commercial and illustrate the impact of product–story link.

Study 3: Test of Hypotheses (Experiment)

Study 3 uses an experimental design aiming to replicate the findings of Study 2, which provides a more stringent test of internal validity of the effect of product–story link.

Method

Design and Procedure

This between-subjects experiment assigned respondents randomly to one of two conditions, either high or low product–story link. The general procedure of stimulus exposure and measurement was the same as in Study 2.

Stimulus

We selected the KFC advertisement from the previous studies as a base for the stimuli because it was low in product–story link (Study 1 mean|KFC = 2.02, SD = 1.28). We created a low and a high product–story link condition. The manipulation should increase the product–story link index in the high condition. In conceptualizing the manipulation, we mainly targeted two types of product–story link. The plot setting (represented by the product link type “narrative specificity”) and the behavior of the characters (represented by the link type “behavior”) in the video ad lent themselves to a manipulation to increase product–story link by changing the product category.

We ensured that the story itself remained unchanged across conditions and was kept the same as in the original TV commercial. The editing process included changing the brand KFC to a fictional brand called Magnus, the removal of images of food products, the insertion of new text, and the addition of new audio for the text, which was created with a natural-sounding voice using text-to-speech software to ensure that the voice, talking speed, and intonation were the same across conditions.

The story of the ad plays in a gym, which is relevant for narrative specificity. The low product–story link condition presented Magnus as a restaurant chain (similar to the original ad where KFC was a fast-food chain), while in the condition of high product–story link it was a fitness-center chain. The setting in a gym displays a specific physical setting (i.e., thematic and product relevant surroundings) to link the product in the high condition (fitness chain) more closely to the story than in the low product link condition (food chain), which heightens narrative specificity.

The character in the ad successfully conducts a somersault, which implicitly suggests a certain level of training and fitness. Product–story link is enhanced by the relevance of the product for this behavior of the character in the high product link condition (gym use improves the ability to engage in such behavior), while in the low product link condition this is not the case (food being neutral for the behavior). Thus, the behavior type of product–story link was relevant as well. We reemphasized this implicit point in the few words that were changed to ensure the text fit the product category (“Get the best out of yourself! Discover the fitness centers of Magnus” versus “Get the best food! Discover the restaurants of Magnus”).

Sample

Respondents were provided by Clickworker, a commercial online panel platform. The usable sample size was N = 206 (n|Low =104, n|High = 102) after 14 respondents were excluded because they did not pass the attention check (Paas and Morren Citation2018). The mean age of the sample was 35 (SD = 11.72), and 48% were female. There were no differences in gender distribution between the conditions, χ² (1)=1.93, p = 0.165, but a significant difference in age was detected, t (192.02)= −2.29, p < 0.05, M|Low = 32.88 (SD = 10.18), M|High =36.59 (SD = 12.88). Thus, age was included as control variable in the model.

Measurements

The measures were the same as in Study 2, and all had good internal reliability, α ≥ 0.8 (see in the appendix for more descriptive statistics).

Results

Manipulation Check

The result of an independent-samples t test showed that the two conditions differ significantly in terms of product–story link, t (204) = −7.814, p < 0.001, M|Low = 2.88 (SD = 1.53), M|High = 4.49 (SD = 1.43).

Serial Mediation Model

We specified the same model as in Study 2 but with the categorical treatment of product–story link as independent variable. We used standard errors based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples to create the confidence intervals (CI). Results do not change to a relevant extent when using parametric statistical inference to create the intervals.

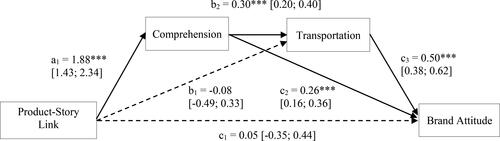

An overview of the results is depicted in . We observe a significant effect of product link on comprehension, a1=1.88 [1.43, 2.34], supporting hypothesis 1(a), which then impacts transportation, b2=0.30 [0.20, 0.40], supporting hypothesis 1(b), which in turn affects brand attitude, c3=0.50 [0.38, 0.62], supporting hypothesis 2. The sequence of indirect effects (a1*b2*c3; see ) is also significant, β = 0.28 [0.16, 0.43], providing evidence for serial mediation. Again, we find support for hypotheses 1(a), 1(b), and 2.

Figure 3. Overview of serial mediation model estimates (Study 3: experiment). Product–story link is represented by the experimental conditions (categorical; dummy-coded). The control variables product category involvement, brand familiarity, and age are not included in the figure for aesthetic reasons. See Table OA3 in the Supplemental Online Appendix for the individual regressions and all parameter estimates; ***p < 0.001.

Other paths were included in the model for completeness of the serial mediation model. The direct effect of product link on brand attitude is nonsignificant, c1 = 0.05 [−0.35, 0.44], as was its effect on transportation, b1 = −0.08 [−0.49, 0.33]. Comprehension has a significant direct effect on brand attitude, c2 = 0.26 [0.16, 0.36].

Discussion

Study 3 replicated the results of Study 2 while applying a more stringent approach to internal validity with an experimental design that manipulated the causal variable of interest, product–story link. The experiment shows by means of an edited video commercial that an increase in product–story link leads to higher levels of subjective comprehension, transportation, and finally brand attitude. Therefore, the effects of product–story link impact brand attitude via mediation. The results support the hypotheses, and only minor differences were observed between Study 2 and Study 3 in terms of the extent of mediation (partial or full mediation), but both studies provide empirical evidence for mediation.

General Discussion and Conclusion

We observed that story ads with a weak link to the product are part of industry practice; the examples in the studies showed that even established brands produce such ads (e.g., KFC). In addition, the literature has hinted at the disappearance of the product in narrative ads (Stern Citation1994a), which we see as an indicator of the prevalence of reducing the product’s role in narrative ads. Although this is not a problem of itself, a story detached from the product leading to a weak link constitutes one. Escalas (2004b) notes, “The structure of narratives provides the framework for causal inferencing about the meaning of brands” (p. 169). Although she is making a more general point about the function of narratives in consumers’ life, her statement also describes in a literal sense the link between product and story in a specific narrative message, for example, a narrative ad. If the product is not properly integrated in the narrative structure, the link becomes weak and can reduce subjective comprehension of meaning.

Thus, we extended the transportation-imagery model in a narrative advertising context by considering product–story link and hypothesizing its impact on transportation and marketing relevant outcomes, namely brand attitude, and the underlying process. Our studies support the hypotheses empirically and illustrate that neglecting product–story link has negative effects in terms of persuasion.

To briefly recap the empirical results, the studies showed that a stronger product–story link in a narrative video advertisement increases subjective comprehension, which facilitates transportation, which then impacts brand attitude. Study 1 validated the measurement index of product–story link empirically, while Study 2 and Study 3 tested the serial mediation model and hypotheses. The two studies supported the effect of product–story link on brand attitude mediated by subjective comprehension and transportation. The indirect effect (Product–story link → Comprehension → Transportation → Brand Attitude; path: a1*b2*c3; see and ) remained significant in both studies, an observational survey and an experiment, lending support to the robustness of the findings.

These findings add to the previous literature asserting the importance of a smooth interlinkage and comprehension of elements in mental models for narrative transportation (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008) and the effects of transportation on attitudes (e.g., Escalas Citation2004a). Specifically, our research extends on previous literature discussing the transportation-imagery model in a narrative ad context, specifically in the field of message factors that impact narrative transportation (e.g., Escalas Citation2004a; Zheng, Phelphs, and Pimentel Citation2019). This literature was complemented with narrative comprehension research (e.g., Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2008; Graesser, Singer, and Trabasso Citation1994) to derive a research model that illustrates a persuasive process in narrative ads related to the product.

Further, product–story link reflects an important challenge for story-based persuasive messages, namely, to integrate persuasive elements in a narrative (Slater and Rouner Citation2002). Although research has investigated the effectiveness of narrative and nonnarrative ad messages (e.g., Krause and Rucker 2020), research untangling the conundrum of integrating persuasive elements (especially related to product and brand) in narrative formats is comparatively rare (e.g., Karpinska-Krakowiak and Eisend Citation2020; Wentzel, Tomczak, and Herrmann Citation2010; Wu et al. Citation2020). Product–story link adds to the aforementioned literature and generally to research that has identified factors that affect the impact of narrative ads, like story character selection (Dessart Citation2018), instances where consumers might not have sufficient cognitive capacity to be transported (Chang Citation2009a), effectiveness of ad repetition and variation strategies (Chang Citation2009b), or how grotesque imagery enhances transportation for luxury brands (An et al. Citation2020).

In addition, despite the advantage of narratives to reduce critical thought, this advantage can occur only if transportation can be established (Escalas Citation2007). Product–story link facilitates a smooth transportation experience in advertising contexts where ad skepticism and persuasion coping mechanisms can easily be activated and reduce transportation and therefore attitude change (Escalas Citation2007; Friestad and Wright Citation1994; Wentzel, Tomczak, and Herrmann Citation2010).

Also, this study applied video as medium because it corresponds to the media zeitgeist, consumers’ exposure to video, and thus the reality of marketing (Khabab Citation2020; Oziemblo Citation2020). Yet narrative ad research mostly uses print as medium to illustrate transportation effects (e.g., An et al. Citation2020; Escalas Citation2004a). Thus, this research contributes to the literature illustrating transportation into narrative ads that use dynamic images (i.e., short video commercials; e.g., Dessart Citation2018). Gathering more evidence on factors affecting transportation in media beyond print is crucial because, as narrative static images as opposed to narrative text showed, this modality affected the relevance of transportation as mediator for attitudes (Lien and Chen Citation2013). Still, a meta-analysis of health communications found evidence for persuasive effects of video narratives but not for text narratives (Shen, Sheer, and Li Citation2015).

Considering the application of the index, the construct of product–story link captures an overall perception. Consequently, it can accommodate a variety of possible links between product and story, making the index versatile to assess various narrative ads. Still, the index seems particularly suited for video ads, which are rich in content and combine different types of product–story links.

The effect of product–story link on transportation was mediated by subjective comprehension and illustrates the importance of a holistic perspective when designing a story ad, including link with the product, which is in line with the holistic processing of stories by consumers (Adaval and Wyer Citation1998). Still, the measurement of comprehension we applied is not assessing the objective accurateness of meaning identification (i.e., objective comprehension) but comprehension of subjective meaning (i.e., self-report scale of subjective comprehension). Therefore, subjective comprehension empirically reflects that the respondent understood a meaning and this aided transportation in turn. This is in line with the notion that understanding stories is a subjective process of meaning construction (Bartlett Citation1932; Oatley Citation1999b; van Laer et al. Citation2014). As Bruner (Citation1986) poignantly notes about narratives, the “intention is to initiate and guide a search for meanings among a spectrum of possible meanings” (p. 25). Thus, subjective comprehension is sufficient for transportation, allowing for more than one meaning interpretation when accessing the narrative and being transported. Still, a product–story link that is too weak can render this search for meanings unsuccessful.

Managerial Implications

Product–story link can be used as a tool to improve transportation (engagement) into and thus better guide the optimal persuasive outcome of narrative advertisements. An immersive experience, like transportation provides, is nowadays highly important to keep viewers, who multitask, skip ads, and are flooded with information, engaged. As a result, message factors under the control of the communicator that improve engagement are useful in creating narrative ads that have persuasive impact.

In addition, the product–story link index was developed based on narrative video commercials, which is of practical importance, given the massive rise in the general consumption of video, tendencies to prefer consumption of content in a video format, and the associated increased creation of video content by marketers (Khabab Citation2020; Oziemblo Citation2020). Still, the self-report items in the index can be applied to a variety of contexts and media, making it a versatile and easily administrable instrument.

Further, the taxonomy of the index encompasses a variety of types of product–story link that have been combined from the literature and from observing advertising practice. Therefore, it illustrates several ways to integrate products in narratives ads, which ensures that the transportation experience the story elicits is not disturbed by inconsistencies related to the product. Thus, the index is also a brief and simplified taxonomy that can serve as a practical support on how to establish product–story link in narrative ads. Examples include integrating the product as the causal changemaker in the story, tailoring the story specifically to your product so that viewers cannot imagine another product in its place, or—an old classic—the product being the resolution to a problem. These suggestions for product link are not mutually exclusive; optimally, an integration covers several types because all of them contribute to a stronger product–story link. Thus, we gave an overview of link types that appear appropriate for linking story and product in various narrative ads. These link types seem to work in different narrative ads and can be used as a rough roadmap on how to achieve product–story linkage.

In addition, we illustrated in the experiment how different types of product–story link index can be applied when constructing advertisements. We achieved a successful increase in the link with a positive effect on brand attitude by simple means, including adapting the text and editing the existing video ad material. Marketing creatives who design ads from scratch are likely to be able to use the product–story link index with its various types to enhance the persuasive outcomes of their ads even more than what we illustrated in the experiment.

In spotlight of the findings, we can state that an intensification of product–story link is advantageous, and advertisers should pay attention to make this link understandable to the viewer. A disappearance of the product in narrative ads is not per se problematic as long as the perceived link to the story remains comprehensible for viewers.

Finally, an immersing story is the basis for a good narrative ad, but to unfold its full persuasive potential the product–story link needs to be strong. In the industry, budget and time constraints can pose limitations on developing an ad that might result in a weak product link and a lower potential to transport viewers. Even in this case, narrative product link could be strengthened with simple cues (e.g., verbal explanations) that optimize message design in terms of transportation and thus persuasive impact.

Limitations and Future Research

The results of this research need to be interpreted in context and with associated limitations. The studies utilized convenience consumer samples, and thus sampling limitations apply. The research focused on narrative advertisements, but the results can be extrapolated to some extent to the larger context of persuasive narrative messages. Although we included a variety of narrative ads to test the model, the ads remain a selection. Yet the ads covered substantial parts of the product link spectrum, which supports some generalizability of the results for narrative video commercials.

We observed that product–story link affects comprehension of subjective meaning. Further, as long as consumers find meaningful connections to brand narratives for themselves (Escalas Citation2004b), correct meaning identification (objective comprehension) is, at least by conceptualization, not an issue in narrative thought (Padgett and Allen Citation1997). Still, it might become an issue when narratives about products and brands become too diluted in meaning, given that narratives are open to multiple meaning interpretations by consumers (Padgett and Allen Citation1997). Notably, today’s consumer environment facilitates varying approaches of meaning construction from narratives (Feiereisen et al. Citation2020). Future studies could investigate how differences in understanding the objective and subjective meanings in narrative ads affects the dilution or fragmentation of a company’s brand image.

In addition, we would assume beyond our empirical evidence that a stronger product–story link narrows the potential variance of meaning attributions with regard to the message, facilitating objective meaning comprehension. Thus, a strong product–story link potentially reduces narrative meaning dilution in narrative communications with regard to the product.

Another aspect to consider with regard to comprehension in narrative ads is processing ease. For example, previous research discussed processing fluency of printed media and repetition and variation strategies in narrative advertising (Chang Citation2013; Chang Citation2009b). Still, we focused on a parsimonious measure of subjective comprehension, which is distinct from processing ease, and also the results of Study 3 provide complementary empirical evidence. Specifically, in Study 3 we applied an experimental manipulation of product–story link while the story line itself remained constant. The experiment suggests that even when the story line is held constant (content such as characters and visuals; meaning the difficulty of the narrative remained constant), the integration of the product in the story, differing only by a few words referencing the product category, impacted subjective comprehension (compare with significant manipulation check). Still, product–story link could be investigated in future studies with a focus on how it specifically affects processing ease.

A dimension we did not explore is modality (Green et al. Citation2008; van Laer et al. Citation2014). Product–story link is currently limited to viewers’ overall perceptions and was tested on video. Yet modal dimensions could be explored in future research, similar to approaches in product placement literature (e.g., Russell Citation1998, Citation2002). Other media forms like text might behave differently than video because text leaves more to the imagination (Lien and Chen Citation2013; Rossiter and Percy Citation1983). In addition, in narrative texts consumers can return to specific passages, which might nurture critical thoughts, because respondents can reexamine the text in detail (Braverman Citation2008), for example, passages relating to the product.

Studies that investigate the intersection of message and individual in terms of outcome- and process-focused thoughts seem fruitful (Escalas Citation2004a). A process focus might be induced by verbal instructions for consumers to imagine themselves using a product, for example, as done with narrative print ads asking consumers to “imagine themselves running in the shoes” (Escalas Citation2004a, p. 41). None of the ads in the studies used such verbal cues, but product–story link might be related to a thought focus, which is conducive to simulation and perspective taking as first person in the narrative (Green and Donahue Citation2009; Oatley Citation1999a).

Cases of narrative ads where product link takes a particularly aggressive form (as a qualitative difference) might exist and elicit negative effects; such ads were not part of the scope of this study. Such particular ads could create a backlash because it is perceived as manipulative intent, which is detrimental for persuasion in narratives (Wentzel, Tomczak, and Herrmann Citation2010).

Individual differences are of relevance for transportation (e.g., Zheng, Phelphs, and Pimentel Citation2019; Appel and Richter Citation2010), and differences between consumers in their sensibility to detect inconsistencies with regards to product–story link are likely. These are probably related to the cognitive needs of individuals and their ways of dealing with inconsistencies and ambiguities (Cacioppo and Petty Citation1982; Webster and Kruglanski Citation1994). We focused on the advertiser’s perspective, but studies could complement this by investigating individual differences in this context. This becomes a systematic difference when culture is considered.

Advertising needs to match the societal culture to maximize effectiveness (e.g., matching advertising appeal to cultural value; Zhang and Gelb Citation1996), and advertising research has been approached with various cultural theories, ranging from Hofstede’s cultural dimensions to Hall’s high- and low-context cultures (Lee Citation2019). The latter distinction between cultures is a fruitful venue to explore product–story link because the extent of “contexting—the process of filling in background data” (Hall and Hall Citation1994, p. 7) differs between these cultures.

In high-context cultures the emphasis is less on explicit verbal communication but rather on the background information in which the words are embedded, which affects the meaning of the words, while in low-context cultures the focus is on the explicit verbal communications and background information has to be provided in the message (Hall and Hall Citation1994). For example, low-context cultures might respond well to product–story link connection via explicit verbal cues (like we illustrated in the experiment for a low-context culture, the Germanic cluster; GLOBE Project Citation2004; Würtz Citation2006). In high-context cultures this might not even be necessary because the focus could be on additional cues provided, like visuals (Würtz Citation2006), which is especially relevant for video ads. Thus, high-context cultures, like those of Korea, China, and Japan, might be more flexible in constructing meaning when product–story link is weak and less explicit but rich context is present (e.g., visuals), attenuating negative effects on transportation. This avenue of research remains to be explored.

Supplemental Online Appendix

Download MS Word (25.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on previous versions of this article. We would also like to thank Hans Baumgartner (The Pennsylvania State University), Adamantios Diamantopoulos (University of Vienna), and Georgios Halkias (Technical University of Munich) for their thoughtful comments and constructive discussions regarding this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthias Glaser

Matthias Glaser (MSc, University of Vienna) is a doctoral candidate and research associate in the Department of Marketing and International Business, University of Vienna.

Heribert Reisinger

Heribert Reisinger (PhD, Vienna University of Economics and Business) is an associate professor in the Department of Marketing and International Business, University of Vienna.

References

- Aaker, David A. 2018. Creating Signature Stories. Strategic Messaging That Persuades, Energizes and Inspires. New York: Morgan James Publishing.

- Adaval, Rashmi, and Robert S. Wyer, Jr. 1998. “The Role of Narratives in Consumer Information Processing.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 7 (3):207–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp0703_01

- An, Donghwy, Chulsung Lee, Janghyun Kim, and Nara Youn. 2020. “Grotesque Imagery Enhances the Persuasiveness of Luxury Brand Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (6):783–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1548198

- Appel, Markus, Timo Gnambs, Tobias Richter, and Melanie C. Green. 2015. “The Transportation Scale–Short Form (TS–SF).” Media Psychology 18 (2):243–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.987400

- Appel, Markus, and Tobias Richter. 2010. “Transportation and Need for Affect in Narrative Persuasion: A Mediated Moderation Model.” Media Psychology 13 (2):101–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15213261003799847

- Balasubramanian, Siva K., James A. Karrh, and Hemant Patwardhan. 2006. “Audience Response to Product Placements.” Journal of Advertising 35 (3):115–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367350308

- Bartlett, Frederic C. 1932. Remembering. A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Braddock, Kurt, and James P. Dillard. 2016. “Meta-Analytic Evidence for the Persuasive Effect of Narratives on Beliefs, Attitudes, Intentions, and Behaviors.” Communication Monographs 83 (4):446–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555

- Braverman, Julia. 2008. “Testimonials versus Informational Persuasive Messages.” Communication Research 35 (5):666–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208321785

- Bruner, Jerome. 1986. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Busselle, Rick, and Helena Bilandzic. 2008. “Fictionality and Perceived Realism in Experiencing Stories. A Model of Narrative Comprehension and Engagement.” Communication Theory 18 (2):255–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00322.x

- Cacioppo, John T., and Richard E. Petty. 1982. “The Need for Cognition.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 42 (1):116–31. (doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.116

- Chang, Chingching. 2009a. “Being Hooked" by Editorial Content. The Implications for Processing Narrative Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 38 (1):21–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367380102

- Chang, Chingching. 2009b. “Repetition Variation Strategies for Narrative Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 38 (3):51–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367380304

- Chang, Chingching. 2013. “Imagery Fluency and Narrative Advertising Effects.” Journal of Advertising 42 (1):54–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2012.749087

- Chang, Chun-Tuan, and Ching-Ting Yen. 2013. “Missing Ingredients in Metaphor Advertising: The Right Formula of Metaphor Type, Product Type, and Need for Cognition.” Journal of Advertising 42 (1):80–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2012.749090

- Deighton, John, Daniel Romer, and Josh McQueen. 1989. “Using Drama to Persuade.” Journal of Consumer Research 16 (3):335–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209219

- Dessart, Laurence. 2018. “Do Ads That Tell a Story Always Perform Better? The Role of Character Identification and Character Type in Storytelling Ads.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 35 (2):289–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2017.12.009

- Diamantopoulos, Adamantios, and Judy A. Siguaw. 2006. “Formative versus Reflective Indicators in Organizational Measure Development: A Comparison and Empirical Illustration.” British Journal of Management 17 (4):263–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00500.x

- Diamantopoulos, Adamantios, and Heidi M. Winklhofer. 2001. “Index Construction with Formative Indicators: An Alternative to Scale Development.” Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2):269–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.269.18845

- Duff, Brittany R. L., and Claire M. Segijn. 2019. “Advertising in a Media Multitasking Era: Considerations and Future Directions.” Journal of Advertising 48 (1):27–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1585306

- Eisend, Martin. 2008. “Explaining the Impact of Scarcity Appeals in Advertising: The Mediating Role of Perceptions of Susceptibility.” Journal of Advertising 37 (3):33–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367370303

- Escalas, Jennifer E. 2004a. “Imagine Yourself in the Product. Mental Simulation, Narrative Transportation, and Persuasion.” Journal of Advertising 33 (2):37–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2004.10639163

- Escalas, Jennifer E. 2004b. “Narrative Processing: Building Consumer Connections to Brand.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 14 (1–2):168–80.

- Escalas, Jennifer E. 2007. “Self‐Referencing and Persuasion. Narrative Transportation versus Analytical Elaboration.” Journal of Consumer Research 33 (4):421–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/510216

- Escalas, Jennifer E., and Barbara B. Stern. 2003. “Sympathy and Empathy. Emotional Responses to Advertising Dramas.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (4):566–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/346251

- Feiereisen, Stephanie, Dina Rasolofoarison, Cristel A. Russell, and Hope J. Schau. 2020. “One Brand, Many Trajectories: Narrative Navigation in Transmedia.” Journal of Consumer Research doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa046

- Fransen, Marieke L., Peeter W. J. Verlegh, Amna Kirmani, and Edith G. Smit. 2015. “A Typology of Consumer Strategies for Resisting Advertising, and a Review of Mechanisms for Countering Them.” International Journal of Advertising 34 (1):6–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.995284

- Friestad, Marian, and Peter Wright. 1994. “The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (1):1–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209380

- Gardner, Burleig, and Sidney J. Levy. 1955. “The Product and the Brand.” Harvard Business Review 33 (March/April):33–9.

- Gerrig, Richard J. 1993. Experiencing Narrative Worlds. On the Psychological Activities of Reading. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- GLOBE Project. 2004. “Germanic Europe.” 9 February 2021. https://globeproject.com/results/clusters/germanic-europe?menu=cluster#cluster.

- Graesser, Arthur C., Murray Singer, and Tom Trabasso. 1994. “Constructing Inferences during Narrative Text Comprehension.” Psychological Review 101 (3):371–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.3.371

- Green, Melanie C., and Timothy C. Brock. 2000. “The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79 (5):701–21.

- Green, Melanie C., and Timothy C. Brock. 2002. “In the Mind’s Eye: Transportation-Imagery Model of Narrative Persuasion.” In Narrative Impact. Social and Cognitive Foundations, edited by Melanie C. Green, Jeffrey J. Strange, and Timothy C. Brock, 315–41. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Green, Melanie C., and John K. Donahue. 2009. “Simulated Worlds: Transportation into Narratives.” In Handbook of Imagination and Mental Simulation, edited by Keith D. Markman, 241–54. New York: Psychology Press.

- Green, Melanie C., Sheryl Kass, Jana Carrey, Benjamin Herzig, Ryan Feeney, and John Sabini. 2008. “Transportation across Media: Repeated Exposure to Print and Film.” Media Psychology 11 (4):512–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802492000

- Hall, Edward T., and Mildred R. Hall. 1994. Understanding Cultural Differences. 8th ed. Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press.

- Hamby, Anne, and David Brinberg. 2016. “Happily Ever after: How Ending Valence Influences Narrative Persuasion in Cautionary Stories.” Journal of Advertising 45 (4):498–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1262302

- Jeon, Yongwoog A., Hyunsang Son, Arnold D. Chung, and Minette E. Drumwright. 2019. “Temporal Certainty and Skippable in-Stream Commercials: Effects of Ad Length, Timer, and Skip-Ad Button on Irritation and Skipping Behavior.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 47:144–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2019.02.005

- Karpinska-Krakowiak, Malgorzata, and Martin Eisend. 2020. “Mini-Film Advertising and Digital Brand Engagement: The Moderating Effects of Drama and Lecture.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (3):387–409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1633841

- Kaufman, Geoff F., and Lisa K. Libby. 2012. “Changing Beliefs and Behavior through Experience-Taking.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 103 (1):1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027525

- Kent, Robert J., and Chris T. Allen. 1994. “Competitive Interference Effects in Consumer Memory for Advertising: The Role of Brand Familiarity.” Journal of Marketing 58 (3):97–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800307

- Khabab, Osama. 2020. “2020 Video Marketing Trends and Predictions.” February 11. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2020/07/03/2020-video-marketing-trends-and-predictions/?sh=123555e72bd9.

- Kim, Eunjin, S. Ratneshwar, and Esther Thorson. 2017. “Why Narrative Ads Work. An Integrated Process Explanation.” Journal of Advertising 46 (2):283–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1268984

- Krause, Rebecca J., and Derek D. Rucker. 2020. “Strategic Storytelling: When Narratives Help versus Hurt the Persuasive Power of Facts.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 46 (2):216–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219853845

- Laskey, Henry A., Ellen Day, and Melvin R. Crask. 1989. “Typology of Main Message Strategies for Television Commercials.” Journal of Advertising 18 (1):36–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1989.10673141

- Lee, Wei-Na. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Culture in Advertising: Resolving Persistent Issues and Responding to Changes.” Journal of Advertising 48 (1):115–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1579686

- Lee, Yih H., and Charlotte Mason. 1999. “Responses to Information Incongruency in Advertising: The Role of Expectancy, Relevancy, and Humor.” Journal of Consumer Research 26 (2):156–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209557

- Lien, Nai-Hwa, and Yi-Ling Chen. 2013. “Narrative Ads: The Effect of Argument Strength and Story Format.” Journal of Business Research 66 (4):516–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.016

- MacInnis, Deborah J., Ambar G. Rao, and Allen M. Weiss. 2002. “Assessing When Increased Media Weight of Real-World Advertisements Helps Sales.” Journal of Marketing Research 39 (4):391–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.39.4.391.19118

- Marlowe, Julia, Gary Selnow, and Lois Blosser. 1989. “A Content Analysis of Problem-Resolution Appeals in Television Commercials.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 23 (1):175–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1989.tb00242.x

- McFarland, Sam G. 1981. “Effects of Question Order on Survey Responses.” Public Opinion Quarterly 45 (2):208–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/268651

- McQuarrie, Edward F., and Barbara J. Phillips. 2005. “Indirect Persuasion in Advertising: How Consumers Process Metaphors Presented in Pictures and Words.” Journal of Advertising 34 (2): 7–20.

- Mittal, Banwari. 1995. “A Comparative Analysis of Four Scales of Consumer Involvement.” Psychology and Marketing 12 (7):663–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220120708

- Oatley, Keith. 1999a. “Meetings of Minds: Dialogue, Sympathy, and Identification, in Reading Fiction.” Poetics 26 (5–6):439–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(99)00011-X

- Oatley, Keith. 1999b. “Why Fiction May Be Twice as True as Fact: Fiction as Cognitive and Emotional Simulation.” Review of General Psychology 3 (2):101–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.3.2.101

- Oziemblo, Andrew. 2020. “The Evolution of Digital Marketing to Video Marketing.” February 11. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2020/01/07/the-evolution-of-digital-marketing-to-video-marketing/?sh=1bf943da5298.

- Paas, Leonard J., and Meike Morren. 2018. “Please Do Not Answer If You Are Reading This: Respondent Attention in Online Panels.” Marketing Letters 29 (1):13–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-018-9448-7

- Padgett, Dan, and Douglas Allen. 1997. “Communicating Experiences. A Narrative Approach to Creating Service Brand Image.” Journal of Advertising 26 (4):49–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1997.10673535

- Petty, Richard E., and John T. Cacioppo. 1986. Communication and Persuasion. Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York: Springer New York.

- Phillips, Barbara J., and Edward F. McQuarrie. 2010. “Narrative and Persuasion in Fashion Advertising.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (3):368–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/653087

- R Core Team. 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Revelle, William. 2019. Psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

- Rosseel, Yves. 2012. “Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of Statistical Software 48 (2):1–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Rossiter, John R., and Larry Percy. 1983. “Visual Communication in Advertising.” In Information Processing Research in Advertising, edited by Richard Jackson Harris and Richard J. Harris, 83–125. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Russell, Cristel A. 1998. “Toward a Framework of Product Placement: Theoretical Propositions.” Advances in Consumer Research 25:357–62.

- Russell, Cristel A. 2002. “Investigating the Effectiveness of Product Placements in Television Shows: The Role of Modality and Plot Connection Congruence on Brand Memory and Attitude.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (3):306–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/344432

- Seo, Yuri, Xiaozhu Li, Yung K. Choi, and Sukki Yoon. 2018. “Narrative Transportation and Paratextual Features of Social Media in Viral Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 47 (1):83–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1405752

- Shen, Lijiang, Suyeun Seung, Kristin K. Andersen, and Demetria McNeal. 2017. “The Psychological Mechanisms of Persuasive Impact from Narrative Communication.” Studies in Communication Sciences 17 (2):165–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.24434/j.scoms.2017.02.003

- Shen, Fuyuan, Vivian C. Sheer, and Ruobing Li. 2015. “Impact of Narratives on Persuasion in Health Communication: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Advertising 44 (2):105–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Slater, Michael D., and Donna Rouner. 2002. “Entertainment—Education and Elaboration Likelihood: Understanding the Processing of Narrative Persuasion.” Communication Theory 12 (2):173–91.

- Stein, Nancy L., and Tom Trabasso. 1985. “The Search after Meaning: Comprehension and Comprehension Monitoring.” In Applied Developmental Psychology, edited by F. J. Morrison, C. Lord and D. Keating, 33–58. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Stern, Barbara B. 1994b. “Classical and Vignette Television Advertising Dramas: Structural Models, Formal Analysis, and Consumer Effects.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (4):601–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209373

- Stern, Barbara. 1994a. “Authenticity and the Textual Persona: Postmodern Paradoxes in Advertising Narrative.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 11 (4):387–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(94)90014-0

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidell. 2014. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed., internat. ed., Harlow, Essex: Pearson.

- van Laer, Tom, Ko de Ruyter, Luca M. Visconti, and Martin Wetzels. 2014. “The Extended Transportation-Imagery Model. A Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents and Consequences of Consumers' Narrative Transportation.” Journal of Consumer Research 40 (5):797–817. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/673383

- van Laer, Tom, Jennifer Edson Escalas, Stephan Ludwig, and Ellis A. van den Hende. 2018. “What Happens in Vegas Stays on TripAdvisor? A Theory and Technique to Understand Narrativity in Consumer Reviews.” Journal of Consumer Research 36 (7):715. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy067

- Webster, Donna M., and Arie W. Kruglanski. 1994. “Individual Differences in Need for Cognitive Closure.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (6):1049–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1049

- Wentzel, Daniel, Torsten Tomczak, and Andreas Herrmann. 2010. “The Moderating Effect of Manipulative Intent and Cognitive Resources on the Evaluation of Narrative Ads.” Psychology and Marketing 27 (5):510–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20341

- Wu, Tung-Ju, Ting Xu, Lydia Q. Li, and Kuo-Shu Yuan. 2020. “Touching with Heart, Reasoning by Truth!” the Impact of Brand Cues on Mini-Film Advertising Effect.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (8):1322–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1755184

- Würtz, Elizabeth. 2006. “Intercultural Communication on Web Sites: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Web Sites from High-Context Cultures and Low-Context Cultures.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11 (1):274–99.

- Yang, Moonhee, and David R. Roskos-Ewoldsen. 2007. “The Effectiveness of Brand Placements in the Movies: Levels of Placements, Explicit and Implicit Memory, and Brand-Choice Behavior.” Journal of Communication 57 (3):469–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00353.x