Abstract

Despite the increasing market size and consumption power of older consumers, older people seldom appear in advertising, and research activity in this area suggests that advertising scholars have lost interest in the topic. This article proposes some explanations for this neglect of the topic despite its increasing importance and provides a review of knowledge about the representation, portrayal, and effects of older people in advertising. Based on this review, the article identifies several gaps in the literature and proposes an integrative model and agenda for future research. The agenda addresses the definition and operationalization of age and older people and discusses how their representation and portrayal must be evaluated against appropriate baseline figures; how stereotyping can be assessed and measured; how positive perceptions and evaluations of portrayals of older people, despite weak representation and stereotyping, can be explained; and how social and commercial effects can be investigated. The agenda discusses the potential responsibilities of advertisers and the implications of this research for practitioners and public policy.

Older persons represent a growing demographic group in society. In 2019, 9% of the world’s population was 65 years or older, and this figure is projected to rise to 16%, such that one out of six people will be 65 years or older globally by 2050 (United Nations Citation2019). These figures are considerably higher in developed countries. Japan has the highest proportion, at 28% of the population, followed by Italy at 23%. Finland, Portugal, and Greece round out the top five at just under 22%. As for the major economies in the world, 12% of China’s population is aged 65 or older, while the share is 16% in the United States (United Nations Population Division Citation2021). The importance of the so-called silver economy is also rising due to their increasing spending power. Together with the age group of 45 to 64 years old, seniors comprise the wealthiest age cohort in the world (Fengler Citation2021), and generous retirement schemes, lifelong savings, and investments account for their major contribution as consumers to the economy. Despite these figures, older people seldom appear in advertising, and this trend is ongoing (Prieler and Kohlbacher Citation2016) despite advertisers’ longtime indication that they believe older endorsers will become more important and appear more often in advertising (Kohlbacher, Prieler, and Hagiwara Citation2011, Citation2014; Szmigin and Carrigan Citation2000). Academics seem to have lost interest in this issue, and the inclusion of older people in advertising has become an underresearched topic (Prieler and Kohlbacher Citation2016). This gap becomes evident when comparing research on older people in advertising with research on other minority or disadvantaged groups and by looking at research activities over time. While research interest in minority or disadvantaged groups in advertising, such as women (Furnham and Lay Citation2019), sexual minorities (Eisend and Hermann Citation2019), and ethnic minorities (Rößner, Gvili, and Eisend Citation2021), has continued steadily or even grown, studies on the representations of older people in advertising have become fewer, as the following review shows. Most of the existing studies are from the 1980s and 1990s, and only a few studies have been published since—most of them not in advertising but in gerontology and aging journals.

Thus, research on the occurrence and portrayal of older people in advertising is outdated, and research on the effects of elderly endorsers is rare. The few, mostly older studies that exist provide inconclusive results and lack coherent explanations for the effects they describe. This article, therefore, sheds light on a neglected but important topic in advertising research: older people in advertising. It provides an overview of existing research, reveals relevant gaps, and develops an agenda through which future research may address such gaps. To that end, the article first explores why the topic has been ignored by practitioners and academics and provides counterarguments to proposed explanations. Second, the article offers a review of two relevant streams of literature: (a) the representations of older people and (b) the perceptions, evaluations, and effects of older people in advertising. Third, based on these reviews, the article suggests an integrative model and puts forward an agenda for future research on older people in advertising.

Why Older People in Advertising Are Neglected: Reasons and Rebuttals

This section details the three main reasons that advertising practice and research have not given sufficient attention to the topic of older endorsers. These reasons can be met with valid counterarguments.

First, innovators and early adopters of many products are typically younger in age (Rogers Citation2003). Therefore, advertising often targets younger people, even for products used by consumers of all age groups. This trend is especially true for technology products, as companies in that industry often exclusively target young consumers whom they believe will spread the word about their products. However, using age alone to identify the early adopter misses the fact that older consumers are increasingly at ease with technological innovation: for instance, the majority of Twitter and Facebook users are aged 40 years and older, and the adoption rates of social media by the over-65 population are continuously increasing (Nunan and Di Domenico Citation2019). Older consumers even adopt some innovations earlier than younger consumers (e.g., e-bikes; Wolf and Seebauer Citation2014). Furthermore, news of new products and technology travels worldwide quickly on social media, with or without the help of early adopters. With the increasing silver economy, more products and variations are being developed, particularly for the elderly, and younger consumers are not early adopters of these products.

Second, the advertising industry has a “hipster” image, and most people in the industry are young. A recent study shows that less than 10% of all advertising practitioners in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia are over the age of 45 (Brodmerkel and Barker Citation2021). Younger advertisers may consciously or unconsciously choose endorsers with whom they can identify, contributing to the high representation of young people in advertising (Carrigan and Szmigin Citation2000a). While many advertisers seem to be aware that older people should be more prominent in advertising and have indicated for a long time that they believe older endorsers will appear more often in advertising in the future (Kohlbacher, Prieler, and Hagiwara Citation2011, Citation2014; Szmigin and Carrigan Citation2000), the figures show that the use of older people has not increased over time. Researchers have explained this phenomenon with the fact that some advertisers still hold stereotypical prejudices against aging and older people (Carrigan and Szmigin Citation2000a). Ageism (i.e., prejudices about age, including negative attitudes and views and age discrimination; Butler Citation1969) is not just a phenomenon in the advertising industry but strongly reflects the fact that society values youths over those of an older age. From their mid- to late twenties and on, most people report a younger subjective age (i.e., how old they feel) compared to their chronological age (i.e., how old they actually are) (Kotter-Grühn, Kornadt, and Stephan Citation2015), indicating the wish to be around ten years younger. Therefore, even advertisers who want to use endorsers more similar to an older market may still use a model up to 10 years younger than the target group (Prieler and Kohlbacher Citation2016). A society’s values may change when more and more people in it get older. The public discussion about ageism further raises the awareness of the potential negative effects of overlooking the elderly and emphasizing the youth, which may eventually contribute to a higher appreciation of older people in society and in advertising.

Third, plenty of advertising research has provided evidence that the attractiveness or beauty of endorsers has positive effects on consumers and increases, among other things, their evaluations of the ad, their opinions on the brand, and their purchase intentions (e.g., Amos, Holmes, and Strutton Citation2008; Kahle and Homer Citation1985; Shavitt et al. Citation1994). Older people are, on average, rated lower in attractiveness than younger people, who are judged as equally attractive by younger and older people (e.g., Foos and Clark Citation2011; Mathes et al. Citation1985; Mazis et al. Citation1992). Thus it is not surprising that advertisers make extensive use of younger people that resemble the ideal of attractiveness and beauty. However, attractiveness is but one persuasion factor of endorsers in advertising. Research also finds that older people are considered more credible than younger ones (Bristol Citation1996; Milliman and Erffmeyer Citation1989). Everyday consumers, such as the older women appearing in Dove’s “Real Beauty” campaign, can increase perceived authenticity and, in turn, advertising effectiveness (Becker, Wiegand, and Reinartz Citation2019; Shoenberger, Kim, and Johnson Citation2020). With a growing silver economy leading to more products for the elderly and their adoption of those products, advertising might benefit from trading inauthentic young endorsers for authentic, age-appropriate people. Beyond intended commercial effects, advertising also has social effects, influencing a wide array of non-brand-related perceptions, attitudes, values, and behaviors (Eisend Citation2019). Any advertising that promotes stereotypes—including age-related stereotypes (i.e., generalized beliefs and judgments about aging, old age, and older people; Kruse and Schmitt Citation2006), which are universal and share cross-cultural patterns (Fiske Citation2017)—instead of being inclusive conflicts with diversity-related societal goals, which, in turn, can lead to negative reactions from consumers and reduced advertising effectiveness (Åkestam Citation2017). Because stereotypes can have negative effects for individuals, some countries have even introduced legislation regulating stereotyping in advertising (e.g., the United Kingdom’s bans against gender stereotypes; Ellson Citation2019). This action can increase the sensitivity of consumers and reduce their acceptance of advertising practices that promote unfavorable stereotypes.

While these three arguments provide explanations for the lack of older people in advertising and the scholarly neglect of the topic, current developments—such as societal discussion about stereotyping in advertising, changing values in society, the increasing importance of the silver economy, and some positive effects of using older endorsers in advertising—suggest that these explanations do not provide sufficient reason to accept the status quo.

Representation of Older People in Advertising

Many researchers have investigated how often and in what ways older people are portrayed in advertising. We retrieved 66 content analysis studies that report the proportion of older people in advertising and how they have been portrayed alongside several variables, such as role, product, or setting (see Table A in the Supplemental Online Appendix). The studies were identified by prior review studies (e.g., Zhang et al. Citation2006) and were retrieved through keyword searches in a number of databases and Internet search engines (e.g., EBSCO, Google Scholar, ProQuest).Footnote1 Furthermore, all references in the articles retrieved by the keyword search were scanned and found to be appropriate for the review. Content analysis studies that investigate older people in advertising but lack relevant figures on their representation and portrayal (Francher Citation1973; Harwood and Roy Citation1999) and qualitative content analyses that do not provide quantitative figures (e.g., Ylänne, Williams, and Wadleigh Citation2010; Yoon and Powell Citation2012) were not included.

The methodologies of these studies vary, and they also differ in, for instance, the kind of media they investigate and which characteristics they apply to describe how older people are portrayed in advertising. They also vary in terms of how they define “elderly” (e.g., people over 50, 60, or 65 years): While the gerontology literature tends to use 65+, the typical age of retirement, to define old age, some marketing papers define older people as those 50+, in line with commonly applied segmentation criteria or media target groups (see Prieler and Kohlbacher Citation2016). Nonetheless, the majority of studies confirm that older people in mainstream media advertising are underrepresented when compared to population figures. For instance, if the elderly are considered to be 65 years and older, they represent between 15% and 28% of the population in most developed countries, but most studies indicate that less than 10% of all ads—and often even less than 5%—portray them. If the number of people in ads instead of the number of ads is taken as a basis, these figures are even lower. The studies that do provide the percentage of elderly people in the general population of the country in which the content analysis was conducted for comparison consistently show that it is often two to three times higher than the percentage of elderly people in advertising. Some studies have looked at media and ads targeting exclusively older people, and even here a maximum of only 70% of ads depict the elderly; some studies even show considerably lower percentages (Carrigan and Szmigin Citation1999; Clarke, Bennett, and Liu Citation2014; Kvasnicka, Beymer, and Perloff Citation1982; Langmeyer Citation1993; Roberts and Zhou Citation1997; Smith Citation1976). The figures do not indicate any trends of increasing appearance of the elderly in advertising. Furthermore, most research was conducted in the previous century, with 24 papers published in the 1990s and only 10 papers in the past decade, most of them not appearing in advertising journals. These figures underline the suggestion that the topic is underresearched, given the contradiction described: While the percentage of older people in society is increasing steadily, research about older people in advertising has decreased.

As for the way older people are depicted in advertising, the findings show some variation but many commonalities across studies: older women are underrepresented compared to older men; the predominant race of older people is Caucasian; older people mostly take a secondary, minor, or background role; they are more often depicted with others than alone; the most common setting is at home or outdoors; common stereotypes are the golden ager or grandparents; the portrayals are mostly favorable; and the most common product categories are health, hygiene, and medical products, as well as food. In summary, the portrayals often reflect simplified or generalized beliefs and judgments about aging, old age, and older people (Kruse and Schmitt Citation2006). Several survey studies have confirmed that respondents perceive these portrayals as stereotypical (e.g., Kolbe and Burnett Citation1992; Smith, Moschis, and Moore Citation1982).

Perceptions, Evaluations, and Effects of Older People in Advertising

Aside from the set of studies that explore the portrayal of older people in advertising, few studies look at how older people in advertising are perceived and evaluated and what advertising effects they achieve. We found 27 studies through the search procedure described here and by scanning relevant review articles (Bradley and Longino Citation2001). They are separated into two categories: 12 survey studies on the perception and evaluation of older people, further divided into consumer studies and practitioner studies, and 15 experimental studies that manipulate endorser age and analyze its effects (see Table B and Table C in the Supplemental Online Appendix). The findings are mixed and partly inconclusive.

Both consumer and practitioner studies on the perceptions and evaluations of such portrayals find evidence for stereotyping—that is, respondents identified stereotypical depictions of the elderly in advertising, often reported that such images are inaccurate and simplified, and noted that older people are underrepresented in advertising (e.g., Festervand and Lumpkin Citation1985; Smith, Moschis, and Moore Citation1982). On the other hand, consumer studies also find favorability—that is, positive evaluations of advertisements with older people and the perception that older people are depicted favorably (e.g., Langmeyer Citation1984; Niu and Zhou Citation2019). Practitioner studies have further indicated that they believe the demand for and use of elderly in advertising will increase (Kohlbacher, Prieler, and Hagiwara Citation2011, Citation2014; Szmigin and Carrigan Citation2000).

All the existing experimental studies investigate commercial advertising effects while ignoring social effects. Some of them find a next younger effect (Bristol Citation1996; Chevalier and Lichtlé Citation2017), where senior consumers prefer mature and somewhat younger people in advertising because they are considered more credible than very young endorsers and more likable than older, same-age endorsers. Credibility—as well as competence or expertise—is a typical explanation for the positive effects of older people on all consumers (Milliman and Erffmeyer Citation1989). Several studies support a match-up effect, wherein a fit between endorser and product is most effective because of similarity; for instance, research shows that older people work better for advertising medical products than for technology products (Kwon, Saluja, and Adaval Citation2015; Nelson and Smith Citation1988; Rotfeld, Reid, and Wilcox Citation1982). Huber et al. (Citation2013) prove an endorser–product image transfer effect, where the perceived brand age is positively related to the age of the endorser, an effect which is stronger for high product–endorser fit and when mental images about the age of consumers are very salient. However, several studies also find no effects of older versus younger people on advertising effectiveness (Greco and Swayne Citation1992; Skurpin, Beldad, and Tempelman Citation2019). Overall, the findings are not conclusive and do not provide much infomation about the effects that older people have; rather, they suggest that these effects are more nuanced and require moderators that can explain the differences in results.

Agenda and Directions for Future Research

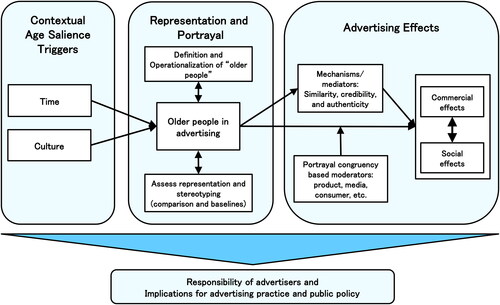

These reviews reveal several inconsistencies in the findings and interpretations of an underresearched but important topic, leaving researchers and practitioners with many questions and several research gaps regarding older people in advertising. These gaps include the definition and operationalization of age, the assessment and explanation of representation and stereotyping, the perceptions and evaluation of elderly portrayals, their commercial and social advertising effects, the advertisers’ responsibility, and the resulting implications for practitioners and public policy. provides an integrative model clarifying the agenda for future research on older people in advertising. The relevant topics of this agenda are elaborated in the next sections. They are summarized in along with the corresponding research gaps and research directions.

Table 1. Research gaps and agenda for future research on older people in advertising.

Definition and Operationalization of Older People and Assessing Representation

To address the context-dependent nature of age conceptualization and enable the comparability of findings across contexts, researchers first need a better operationalization of the term older people and, second, an appropriate and generalizable standard against which to compare the representation of older people in advertising.

The operationalization of what constitutes an older person varies. Several studies use 65 years as the age threshold for defining a person as “old,” which is a figure that reflects the current average retirement age in many developed countries and thus corresponds to an important change in the life cycle and related consumption patterns of consumers (Barnhart and Penaloza Citation2013; Prieler and Kohlbacher Citation2016). While this measure is a meaningful threshold from both a consumer and marketing perspective (Moschis Citation2021), retirement ages differ across countries and time in line with variation in life expectancy. For instance, in Greece and Israel, the average retirement age for men is 67; in Indonesia, it is 57 (Trading Economics Citation2021). The current research practice is oriented toward the standards in developed countries and thus is neither inclusive nor sustainable. Rather than a fixed age threshold to operationalize “older people,” a more flexible and context-dependent measure, such as the average or legal retirement age in a particular country at a particular time, could be a more appropriate way to identify important life cycle changes. Another flexible approach is age distribution. By taking those people who fall into, for instance, the 20th percentile according to age, older people could be operationalized across different contexts. Such a standardized operationalization, although allowing for different age thresholds in different contexts, facilitates generalizable findings and conclusions on older people in advertising that are comparable across contexts. Furthermore, older people are a heterogeneous group that varies in health, roles, activities, and interests. Younger members of this age group appear more often in advertising than older ones, and thus distinguishing between various age groups within the designation of older people can provide further relevant insights (Prieler Citation2020). While content analysis studies typically assess chronological age, coding perceived cognitive or subjective age may be more important for consumers’ responses to advertising with older people, which is discussed next.

To assess whether and to what degree older people in advertising are not well represented, a baseline condition needs to be defined that indicates the correct representation of older people (see Eisend Citation2019). Previous research has often referred to national statistics on the age distribution of the general population in a society to assess whether older people are appropriately represented in advertising. Such a comparison assumes that each group in society should be depicted in the same proportion as they occur in the population, which would be a strong normative assumption for advertisers and contradict the liberal economic activity of markets. The comparison figures are helpful, though, when comparing representations over time or across contexts and cultures. For instance, if the percentage of older people in a society increases over time, but the percentage of elderly in advertising decreases, the question of whether older people in advertising are well represented becomes more pressing, unless there are other plausible explanations for this trend. These comparison figures, however, function only when advertising is addressed to the society as a whole (e.g., in general interest media); it needs to be adapted when the advertising is in or for users of special interest media by using the age distribution of the target group of the media or advertisement as a comparison standard (e.g., Clarke, Bennett, and Liu Citation2014; Kvasnicka, Beymer, and Perloff Citation1982).

Portrayal and Stereotyping

Misrepresentation and stereotyping of older people’s portrayals in advertising has been described through many variables and attributes in prior content analysis studies. For instance, the variable “role” is coded in some studies as major versus minor (e.g., Idris and Sudbury-Riley Citation2016) and in other studies as spokesperson, testimonial, background, and so on (e.g., Atkins, Jenkins, and Perkins Citation1990). For the purpose of the comparison, identification, and quantification of stereotyping, researchers need to recode different variable categories into a standardized category. For instance, the variable “role” could be coded as primary role (including major, spokesperson, testimonial) versus secondary role (including minor, background). The portrayals can be compared along these standardized variable categories to identify and measure misrepresentation and stereotyping. For instance, the distribution of minor versus major roles can be compared between older and younger people in advertising by means of a simple 2 × 2 table and corresponding tests (e.g., chi-square). Stereotyping could be assumed when the distributions differ significantly (e.g., when the chi-square result is significant). The size of the effect inferred from the test (here, the odds ratio) then indicates and measures the degree of stereotyping (Eisend Citation2010; Knoll, Eisend, and Steinhagen Citation2011). However, stereotyping also needs to consider reasonable comparison standards and baselines (Eisend Citation2019).

Most previous research does not apply any tests but rather describes the stereotyping of older people in advertising rather intuitively. For instance, several studies indicate that older people tend to be depicted more often in home settings than in other settings and hence infer stereotyping (Baumann and de Laat Citation2012; Ho and Smith Citation1992). However, evidence of stereotyping requires comparison standards and baselines (Eisend Citation2019). The comparison can follow an ideal or real-world standard. An ideal standard assumes that younger and older people should be depicted alike. For instance, if younger people in advertising are depicted less often at home than older people, the discrepancy would indicate stereotyping, but if the portrayals at home are the same for older and younger people, stereotyping would not be indicated. The real-world baseline compares the portrayal of older people in advertising along certain variables, with the distribution of these variables mirroring those among older people in reality. For instance, many studies have shown that older men occur more often than older women in advertising (e.g., Baumann and de Laat Citation2012; Langmeyer Citation1984). Because the reality indicates that the proportion of older women in the general population is higher than that of men, this real-world comparison can be used to measure stereotyping. Real-world comparison figures are available for overt variables, such as occupations or gender, but not for other variables, such as role or character. Note that both comparison standards (ideal versus real) suggest different perspectives. The ideal presentation proposes that younger and older people should be depicted in similar ways and thus follows an idealistic view of equality—that is, how the world “should be.” This view is very normative for advertising practitioners: For instance, why should older people be shown as often with friends as younger people if in fact younger people spend more time with friends than with family? The reality baseline takes into account differences between younger and older endorsers in advertising as long as they reflect differences in reality, and thus follows a view of how the world “is.” Neither of these baselines suggests that advertising must reflect how the world is or should be; it is merely a measure to determine an objective fact (i.e., whether stereotyping is or is not present).

The assessment of age stereotyping along different variables in previous studies has also ignored the fact that advertising uses older people as endorsers in different ways. Advertising with older people can be directed toward older consumers or applied to products for older consumers, but it can also use the concept of age in humorous ways, such as by breaking age stereotypes to emphasize the youthfulness of a product (Zhang et al. Citation2006). Although all ads with older people can be stereotypical, the way age is contextualized in the advertisement (e.g., as humorous or not) can lead to different consumer responses toward the stereotyping. Hence, further research needs to mobilize a more holistic view by applying content analysis to the context of an ad and its medium.

Most studies have been conducted on advertising in traditional media, while the humorous contextualization of advertising with older people is more common online and on social media, which provides interesting future research opportunities (Boxman-Shabtai and Shifman Citation2015). Future research should therefore consider new media when applying a holistic view that considers the contextualization of age stereotyping. To better understand age portrayals in advertising and to develop further categories that better describe the portrayal of older people in advertising, qualitative studies are a helpful approach. However, few qualitative studies exist (e.g., Ylänne and Williams Citation2009; Yoon and Powell Citation2012), indicating the need for more qualitative research in this area.

Explaining Representation and Stereotyping

Prior research suggests that older people are not well represented in advertising and that they are depicted stereotypically. Because empirical figures from these content analysis studies vary across years and countries, culture and time are important explanatory variables discussed in the literature, as the meaning of age is embedded in different and changing contexts (Ward Citation1984; Zhang et al. Citation2006). Both variables can explain whether age representation and stereotyping have changed over the years and differ across cultural contexts. However, a theoretically sound explanation for such variations is lacking. Age is a category that is not permanently salient, but age salience (i.e., the perceived relevance of chronological age for the self and others; Kruse and Schmitt Citation2006) is triggered by certain events that can increase age identification (i.e., the importance of age to a person’s overall identity), make people aware of their age, and have them feel their age, whether younger or older (Giles et al. Citation2010). If the social context does not provide such triggers, old age is not important and is neglected by society and in particular by the “young” advertising industry (Prieler Citation2020). If older age becomes salient due to, for instance, important political decisions on age-related topics (e.g., changes in state-run pension schemes), the recruitment of older managers in the advertising industry, or an increase in the appearance of older celebrities (Prieler et al. Citation2010), age becomes a more visible topic, and the sensitivity toward older people increases, eventually reflected by better representation of older people in advertising. The social context also provides age-related expectations that serve as a standard or the norm, and if these expectations are based on simplified categories (e.g., older people should not work, should refrain from professional activities), they increase age stereotyping (Freund Citation1997). Increasing old age salience leads to the visibility of and sensitivity toward the topic, and thus expectations will be modified and become more complex and less simplistic. In turn, stereotyping decreases. A positive example of age salience triggers that benefit the representation of the elderly and reduce age stereotypes is provided by streaming services that produce more inclusive shows, including shows that represent older people with positive portrayals. These shows provide a more nuanced picture of aging and seem to reach a large audience, as evidenced by the successful Netflix show Grace and Frankie, the four lead actors of which are in their seventies and eighties (Mohammed Citation2021). However, high salience of young age can counteract the positive effects of old age salience and lead to a self-reinforcing mechanism: Social media content and discourses often make young age salient and reinforce negative discourses about old age, triggering an age identification that focuses on feeling young, which again leads to an orientation toward youth and the invisibility of older people in social media and related advertising (Makita et al. Citation2021).

Perceptions and Evaluations

Research on the perceptions and evaluations of portrayals of older people in advertising finds some evidence for perceived stereotyping, but it also highlights favorability—that is, a positive evaluation of portrayals, particularly by older consumers. This seeming contradiction can be explained by the low salience of age. “Being old” is not generally salient or considered a stigma in the lives of older people, as indicated by the high well-being of older people and generally positive attitudes toward retirement, but it becomes salient occasionally through certain triggers, such as when reaching certain age markers or when facing age-related diseases (Ward Citation1984). Older people further perceive themselves at a lower subjective age, often show resistance to aging, and do not fear consequences when violating age-related expectations (Freund Citation1997; Giles et al. Citation2010). While the low salience of age can explain the overall positive evaluations of portrayals of older people in advertising by older consumers, empirical evidence for this explanation is still lacking. The positive low-salience effect on perceptions and evaluations does not necessarily extend to the commercial and social effects of older people’s portrayals because of different empirical settings (survey versus experiments) and different outcome variables (e.g., evaluations of older people versus evaluations of brands).

Explaining Advertising Effects

Prior research consists of either content analyses on the portrayals of older people or experimental studies on the effects of older people in advertising. Both research streams have not been combined by, for instance, using both methods in a single study in which current portrayals of older people in advertising are captured and categorized through content analysis and their effects tested experimentally. Such an approach would be helpful in providing more realistic research findings and generalizable evidence on the effects of the current portrayals of older people in advertising.

The findings of studies investigating the effects of older people in advertising are mixed, as described previously. Different mechanisms (mediators) and conditions (moderators) can help to explain the variations in the findings. The three main mechanisms that act as mediators are similarity, credibility, and authenticity. Of these, the mechanism that dominates presumably depends on the consumer’s age. Similarity effects are most likely for consumers who feel similar to older endorsers—that is, those that have a similar age (Chevalier and Lichtlé Citation2012). Older people are considered more credible than younger people (Bristol Citation1996); therefore, from a relative age point of view, the credibility of older people should work better for younger consumers. Authenticity is a more general and holistic mechanism (Becker, Wiegand, and Reinartz Citation2019) that is related to both similarity and credibility: Authentic portrayals are considered credible, and older people can better relate to them, as they perceive a similarity between authentic older endorsers and themselves. An important question for future research is which of these three mechanisms leads to the strongest effects and is best able to outweigh the potentially negative effects of older people in advertising (e.g., due to reduced attractiveness). The effects of older celebrity endorsers can be integrated here as well. Age seems to play a lesser role for celebrities (Prieler et al. Citation2010; Yoon and Powell Citation2012), and celebrities benefit from credibility, while at the same time suffering less from lower attractiveness than average consumers. Furthermore, instead of chronological age, which most studies have tried to manipulate, studies on the effects of older people in advertising should consider the subjective/cognitive age (perceived age) of consumers as independent variables, as these age concepts are better effect predictors (Kuppelwieser and Klaus Citation2021).

Previous research has investigated mostly the age of consumers as moderators, dismissing the rich research stream that has already looked at the ad processing of older consumers, even if not in the context of advertisements with older people. Based on age-related differences in processing, elderly consumers prefer affective over rational ads and better remember them (Drolet, Williams, and Lau-Gesk Citation2007; Fung and Carstensen Citation2003; Williams and Drolet Citation2005); they also comprehend difficult ads less (Estrada, Moliner, and Sánchez-Garcia Citation2010), are more susceptible to misleading advertisements (Gaeth and Heath Citation1987), and show lower memory effects due to reduced cognitive speed (Johnson and Cobb-Walgren Citation1994; Stephens Citation1982). Using these insights can help to explain consumer age as a moderator and illustrate how elderly in advertising influence elderly consumers differently than younger consumers when, for instance, elderly endorsers are put in an emotional context (e.g., with family) compared to a rational context (e.g., at work).

The primary focus on age as moderator hides other important moderators, such as product fit, media context, or message characteristics. Whether and how any of these moderators increase or decrease the effects of older people in advertising depends on congruency (see Osgood and Tannenbaum Citation1955) between the portrayals on one hand and the products, messages, and consumer characteristics on the other (e.g., De Meulenaer et al. Citation2018; Orth and Holancova Citation2004). For instance, if older people in advertising are perceived as congruent with certain products, media contexts, or the values of consumers (e.g., young consumers who seek credible and expert advice), the effects are positive; the opposite is also true. From a practical point of view, the moderators that are exogenous and can be influenced by marketers or public policymakers, such as product fit, media fit, or advertising message characteristics, are most relevant.

Social Effects

There has been an exclusive focus in previous research on commercial advertising effects, ignoring social effects. Research on the effects of representation and stereotyping of older people in media suggests several mostly negative social effects, such as promoting negative images of aging or reduced self-concepts of older people, which can even affect their mental health (Donlon, Ashman, and Levy Citation2005; Haboush, Warren, and Benuto Citation2012; Tunaley, Walsh, and Nicolson Citation1999). The socialization effects of underrepresented and stereotyped elderly in media, leading to misperceptions and negative views about the elderly, are explained by both cultivation theory, with its focus on the long-term cultivation of views and values through media consumption (Gerbner et al. Citation1980), and social cognitive theory, with its emphasis on learning through observation, which also includes media consumption (Bandura Citation1994). The nonexistence of research on the social effects of older people in advertising indicates a need for more studies, not just for potential ethical reasons but also because social, non-brand-related effects and commercial, brand-related effects are interrelated (Åkestam Citation2017). On one hand, advertising that uses older people increases age salience and visibility, which can cultivate values and attitudes related to the treatment of older people in society (Gerbner et al. Citation1980). On the other hand, social effects such as negative feelings among older people that are caused by misrepresented older people in advertising (Tunaley, Walsh, and Nicolson Citation1999) can transfer onto the advertised brand. Future effect studies need to include both commercial and social advertising effect variables and investigate their relationship. While research on portrayals of older people in advertising focuses on negative social effects, positive social effects are also feasible (e.g., Åkestam Citation2017), such as the reduction of ageism in society and the increased self-esteem of older people due to more favorable age identities. The evidence of potentially negative social effects of representation and stereotyping of older people in advertising raises in turn the question of advertisers’ responsibility—that is, whether they should do anything to avoid negative social effects and, if so, what.

The Responsibility of Advertisers

Stereotyping as a method of social categorization is part of human information processing and is not necessarily negative, false, or misleading. Age stereotyping can lead to expectations that can provide a useful orientation in everyday life (e.g., that an older person can live a happy and healthy life). However, it can have negative effects on stereotyped people if the images being proliferated lead to oversimplification that restricts life opportunities and thus becomes a so-called stereotype threat (Davies et al. Citation2002). Content analysis studies show that although a high percentage of older people—between one-third and two-thirds of all ads—are shown as happy and content (Balazs Citation1995; Clarke, Bennett, and Liu Citation2014; Jiao and Chang Citation2020; Robinson Citation1998), up to 23% of ads with older people characterize them as sick, feeble, or confused (Ho and Smith Citation1992; Robinson Citation1998; Swayne and Greco Citation1987). Although older people are less healthy than younger ones, advertising can create negative stereotyping effects by overemphasizing certain characteristics of the elderly (e.g., unhealthy elderly in drug advertising). For instance, when media categorizes individuals in their sixties as feeble and weak, society might be inclined to deny these people access to important life activities (e.g., denying a driving license from a certain age on) or to identify them as people that belong at home and in the background. For example, Zhou and Chen (Citation1992) find that older characters are almost twice as often shown at home—67% versus 40%—compared to younger characters. Older people might thus not be trusted to take over tasks or play major roles in daily activities. If such negative stereotyping effects occur, it raises the question of whether advertisers can be held accountable.

Several researchers propose that advertisers have a social responsibility based on ethical guidelines (i.e., “advertisers should not cause harm”) and thus need to become active in reducing ageism, or else they propose that regulations should be introduced (e.g., Carrigan and Szmigin Citation2000a, Citation2000b). The question of advertisers’ responsibility is addressed by the mirror versus mold debate. If advertisers only mirror the values that already exist in society (Holbrook 1987)—that is, if ageism and negative stereotyping is a societal problem—advertising is not to be held accountable. However, if advertising molds negative stereotypes—that is, creates, shapes, and reinforces age stereotypes and ageism (Pollay Citation1986, Citation1987)—advertisers hold some general ethical responsibility. Even if many consumers might be able to identify and evaluate stereotypes competently, the influence of stereotypes can be subtle and lead to an unconscious bias. Furthermore, vulnerable consumer groups such as children are less likely to identify and evaluate stereotypes in advertising and thus need to be protected.

Research that uses longitudinal data is needed to provide empirical evidence for the role of advertising in age stereotyping and determine whether advertising causes negative age stereotypes in society or whether society’s age-related values lead advertisers to depict these values. The data can inform discussions about the implications for advertisers and help answer important questions. For instance, if advertisers simply mirror societal values, can we expect them to promote realistic portrayals of older people that might be desirable for a more just society but jeopardize sales among consumers who prefer to see younger endorsers? If advertisers indeed mold negative stereotypes, can they be held accountable? How can their activities be monitored and regulated? The question of responsibility is complex and needs to balance the various goals of society on one hand and the goals of businesses and the interests of different stakeholder groups on the other.

Whether and how advertisers are held accountable for social effects also depends on the economic freedom in a country. More capitalist economies, such as the United States, are less likely to introduce governmental regulations that restrict the economic freedom of companies (Gwartney et al. Citation2020). For instance, restrictions on advertising quantity are less common in the United States compared to the European Union, with current European Union directives limiting the advertising quantity of broadcast television stations to 12 minutes per hour (e.g., Zhang Citation2018). Similar differences in restrictions apply to stereotypical depictions in advertising with the aim of reducing negative social effects. For instance, the Advertising Standards Authority of the United Kingdom banned two TV commercials under new rules introduced in June 2019 to combat gender stereotyping in advertising (Andrews Citation2019; Ellson Citation2019). In 2008, European Parliament suggested a resolution that demands less stereotyping in advertising. France and Israel have begun to adopt legislation requiring a minimum body mass index for fashion models, targeting also the digital altering of models’ physical characteristics by requiring labels that indicate such changes (Danthinne, Giorgianni, and Rodgers Citation2020) to avoid the negative effects of idealized body images in the media and advertising.

Implications for Practice

Understanding the advertising effects of older people provides important information to advertising and marketing managers. Because of the potential negative social effects of ageism and age stereotyping, it is important to consider ways to optimize commercial advertising effects while avoiding negative social effects. While prior research gives some indications about age-appropriate portrayals, further empirical evidence is required. As described, advertisers are encouraged to consider social effects not only for ethical reasons but also because social and commercial advertising effects are interrelated. Research on older people in advertising further provides implications for policymakers and regulators, given that stereotyping in advertising has emerged as an important public policy issue. Age stereotyping and low representation of older people is a persistent issue in advertising and requires a more evidence-based political debate about appropriate regulations. Advertising regulations often result from a complex political process and pressure from interest groups, and their outcomes are not necessarily strongly supported by empirical evidence and academic research (Ringold Citation2016).

Conclusion

This article sheds light on a neglected but important topic in advertising research: older people in advertising. Based on a review of research about the representation, portrayal, and effects of older people in advertising, the article identifies several gaps in the literature and proposes an integrative model and agenda for future research. The agenda suggests a better definition and operationalization of age and older people and shows how their representation and portrayal must be evaluated against appropriate baseline figures. It recommends standardized categorizations of age stereotyping variables to assess and explain the degree of stereotyping of older people in advertising. The agenda proposes the concept of age salience to explain positive perceptions and evaluations of portrayals of older people, despite weak representation and stereotyping. The agenda further introduces mediators and congruency-based moderators to investigate the commercial effects and recommends more research on social effects of older people in advertising. Finally, the discussion about advertisers’ potential responsibilities requires further empirical evidence on whether advertisers mirror or mold ageism and negative stereotypes. It is hoped that the directions provided by the research agenda will contribute to a more evidence-based political response.

Supplemental Online Appendix

Download MS Word (88.6 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Martin Eisend

Martin Eisend (PhD, Free University Berlin) is a professor of marketing, European University Viadrina.

Notes

1 The following keyword combinations were used: “endorser” and “age” and “advertis*”; “older” and “people” and “advertis*”; “older” and “endorser” and “advertis*”; “elderly” and “advertis*,” all combined with “content analysis.”

References

- Åkestam, Nina. 2017. “Understanding Advertising Stereotypes: Social and Brand-Related Effects of Stereotyped versus Non-Stereotyped Portrayals in Advertising.” PhD thes., Stockholm School of Economics.

- Amos, Clinton, Gary Holmes, and David Strutton. 2008. “Exploring the Relationship between Celebrity Endorser Effects and Advertising Effectiveness. A Quantitative Synthesis of Effect Size.” International Journal of Advertising 27 (2):209–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2008.11073052

- Andrews, Kate. 2019. “The ASA's Puritanical Ban Spree Is a Flagrant Assault on Free Speech.” Accessed August 24, 2019. https://www.cityam.com/the-asas-puritanical-ban-spree-is-a-flagrant-assault-on-free-speech/.

- Atkins, T. Virginia, Martha C. Jenkins, and Mishelle H. Perkins. 1990. “Portrayal of Persons in Television Commercials Age 50 and Older.” Psychology. A Journal of Human Behavior 27 (4):30–7.

- Balazs, Anne L. 1995. “The Use and Image of Mature Adults in Health Care Advertising (1954-1989).” Health Marketing Quarterly 12 (3):13–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J026v12n03_03

- Bandura, Albert. 1994. “Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication.” In Media Effects, edited by Jennings Bryant and Dolf Zillmann, 61–90. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Barnhart, Michelle, and Lisa Penaloza. 2013. “Who Are You Calling Old? Negotiating Old Age Identity in the Elderly Consumption Ensemble.” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (6):1133–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/668536

- Baumann, Shyon, and Kim de Laat. 2012. “Socially Defunct: A Comparative Analysis of the Underrepresentation of Older Women in Advertising.” Poetics 40 (6):514–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2012.08.002

- Becker, Maren, Nico Wiegand, and Werner J. Reinartz. 2019. “Does It Pay to Be Real? Understanding Authenticity in TV Advertising.” Journal of Marketing 83 (1):24–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242918815880

- Boxman-Shabtai, Lillian, and Limor Shifman. 2015. “When Ethnic Humor Goes Digital.” New Media & Society 17 (4):520–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813506972

- Bradley, Don E., and Charles F. Longino. 2001. “How Older People Think about Images of Aging in Advertising and Media.” Generations 25 (3):17–21.

- Bristol, Terry. 1996. “Persuading Senior Adults: The Influence of Endorser Age on Brand Attitudes.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 18 (2):59–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1996.10505052

- Brodmerkel, Sven, and Richie Barker. 2021. “Making Sense of 'Ambiguous Ageism': A Multi-Level Perspective on Age Inequality in the Advertising Industry.” Creative Industries Journal, 1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2021.1911536

- Butler, R. N. 1969. “Age-Ism: Another Form of Bigotry.” The Gerontologist 9 (4):243–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.4_part_1.243

- Carrigan, Marylyn, and Isabelle Szmigin. 1999. “The Portrayal of Older Characters in Magazine Advertising.” Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science 5 (6/7/8):248–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004577

- Carrigan, Marylyn, and Isabelle Szmigin. 2000a. “Advertising in an Ageing Society.” Ageing and Society 20 (2):217–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X99007709

- Carrigan, Marylyn, and Isabelle Szmigin. 2000b. “The Ethical Advertising Covenant: Regulating Ageism in UK Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 19 (4):509–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2000.11104818

- Chevalier, Corinne, and Marie-Christine Lichtlé. 2012. “The Influence of the Perceived Age of the Model Shown in an Ad on the Effectiveness of Advertising.” Recherche et Applications en Marketing 27 (2):3–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/205157071202700201

- Chevalier, Corinne, and Marie-Christine Lichtlé. 2017. “Model's Age and Target's Age: Effects on Emotions towards and Beliefs about an Ad.” In Advances in Advertising Research: Bridging the Gap between Advertising Academia and Practice, edited by George Christodoulides, Anastasia Stathopoulou and Martin Eisend, 133–48. Wiesbaden: Springer-Gabler.

- Clarke, Laura Hurd, Erica V. Bennett, and Chris Liu. 2014. “Aging and Masculinity: Portrayals in Men's Magazines.” Journal of Aging Studies 31:26–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2014.08.002

- Danthinne, Elisa S., Francesca E. Giorgianni, and Rachel F. Rodgers. 2020. “Labels to Prevent the Detrimental Effects of Media on Body Image: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 53 (5):647–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23242

- Davies, Paul G., Steven J. Spencer, Diane M. Quinn, and Rebecca Gerhardstein. 2002. “Consuming Images: How Television Commercials That Elicit Stereotype Threat Can Restrain Women Academically and Professionally.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28 (12):1615–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702237644

- De Meulenaer, Sarah, Nathalie Dens, Patrick de Pelsmacker, and Martin Eisend. 2018. “How Consumers' Values Influence Responses to Male and Female Gender Role Stereotyping in Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 37 (6):893–913. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1354657

- Donlon, M. M., O. Ashman, and B. R. Levy. 2005. “Re-Vision of Older Television Characters: A Stereotype-Awareness Intervention.” Journal of Social Issues 61 (2):307–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00407.x

- Drolet, Aimee, Patti Williams, and Loraine Lau-Gesk. 2007. “Age-Related Differences in Responses to Affective vs. Rational Ads for Hedonic vs. Utilitarian Products.” Marketing Letters 18 (4):211–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-007-9016-z

- Eisend, Martin. 2010. “A Meta-Analysis of Gender Roles in Advertising.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 38 (4):418–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-009-0181-x

- Eisend, Martin. 2019. “Gender Roles.” Journal of Advertising 48 (1):72–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1566103

- Eisend, Martin, and Erik Hermann. 2019. “Consumer Responses to Homosexual Imagery in Advertising: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Advertising 48 (4):380–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1628676

- Ellson, Andrew. 2019. “Ad Banned Over Cheesy Joke About Hapless Dads.” The Times, August 14, 2019, 15.

- Estrada, M., M. A. Moliner, and J. Sánchez-Garcia. 2010. “Attitudes toward Advertisements of the Older Adults.” International Journal of Aging & Human Development 70 (3):231–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.70.3.d

- European Parliament. 2008. “Report on How Marketing and Advertising Affect Equality Between Women and Men.” Accessed November 20, 2008. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=REPORT&reference=A6-2008-0199&language=EN&mode=XML.

- Fengler, Wolfgang. 2021. “The Silver Economy Is Coming of Age: A Look at the Growing Spending Power of Seniors.” Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2021/01/14/the-silver-economy-is-coming-of-age-a-look-at-the-growing-spending-power-of-seniors/.

- Festervand, Troy A., and James R. Lumpkin. 1985. “Response of Elderly Consumers to Their Portrayal by Advertisers.” Current Issues and Research in Advertising 8 (1):203–26.

- Fiske, Susan. 2017. “Prejudices in Cultural Contexts: Shared Stereotypes (Gender, Age) versus Variable Stereotypes (Race, Ethnicity, Religion).” Perspectives on Psychological Science 12 (5):791–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617708204

- Foos, Paul W., and M. Cherie Clark. 2011. “Adult Age and Gender Differences in Perceptions of Facial Attractiveness: Beauty Is in the Eye of the Older Beholder.” The Journal of Genetic Psychology 172 (2):162–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2010.526154

- Francher, J. Scott. 1973. “"It's the Pepsi Generation". Accelerated Aging the Television Commercial.” International Journal of Aging & Human Development 4 (3):245–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/QJ15-7PD9-M14Y-U8YY

- Freund, Alexandra M. 1997. “Individuating Age Salience: A Psychological Perspective on the Salience of Age in the Life Course.” Human Development 40 (5):287–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000278732

- Fung, Helene H., and Laura L. Carstensen. 2003. “Sending Memorable Messages to the Old: Age Differences in Preferences and Memory for Advertisements.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85 (1):163–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.163

- Furnham, Adrian, and Alixe Lay. 2019. “The Universality of the Portrayal of Gender in Television Advertisements: A Review of the Studies This Century.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 8 (2):109–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000161

- Gaeth, Gary J., and Timothy B. Heath. 1987. “The Cognitive Processing of Misleading Advertising in Young and Old Adults: Assessment and Training.” Journal of Consumer Research 14 (1):43–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209091

- Gerbner, G., I. Gross, N. Signorielli, and M. Morgan. 1980. “Aging with Television: Images on Television Drama and Conceptions of Social Reality.” The Journal of Communication 30 (1):37–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01766.x

- Giles, Howard, Mary McIlrath, Antony Mulac, and Robert M. McCann. 2010. “Expressing Age Salience: Three Generations' Reported Events, Frequencies, and Valences.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2010 (206):73–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2010.049

- Greco, Alan J., and Linda E. Swayne. 1992. “Sales Response of Elderly Consumers to Point-of-Purchase Advertising.” Journal of Advertising Research 32 (5):43–53.

- Gwartney, James, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall, Ryan Murphy, Niclas Berggren, Fred McMahon, and Therese Nilson. 2020. Economic Freedom of the World. Annual Report. Vancouver: Fraser Institute.

- Haboush, A., C. S. Warren, and I. Benuto. 2012. “Beauty, Ethnicity, and Age: Does Internalization of Mainstream Media Ideals Influence Attitudes toward Older Adults?” Sex Roles 66 (9-10):668–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0102-6

- Harwood, Jake, and Abhik Roy. 1999. “The Portrayal of Older Adults in Indian and U.S. Magazine Advertisements.” Howard Journal of Communications 10 (4):269–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/106461799246753

- Ho, Foo Nin., and Mickey C. Smith. 1992. “Portrayal of the Elderly in over-the- Counter Drug Television Advertisements.” Journal of Pharmaceutical Marketing & Management 6 (4):21–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/J058v06n04_03

- Huber, Frank, Frederik Meyer, Johannes Vogel, Andrea Weihrauch, and Julia Hamprecht. 2013. “Endorser Age and Stereotypes: Consequences on Brand Age.” Journal of Business Research 66 (2):207–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.07.014

- Idris, Izian, and Lynn Sudbury-Riley. 2016. “The Representation of Older Adults in Malaysian Advertising.” The International Journal of Aging and Society 6 (3):1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.18848/2160-1909/CGP/v06i03/1-16

- Jiao, Wen, and Angela Wen-Yu Chang. 2020. “Unhealthy Aging? Featuring Older People in Television Food Commercials in China.” International Journal of Nursing Science 7:567–73.

- Johnson, Rose L., and Cathy J. Cobb-Walgren. 1994. “Aging and the Problem of Television Clutter.” Journal of Advertising Research 34 (4):54–62.

- Kahle, Lynn R., and Pamela M. Homer. 1985. “Physical Attractiveness of the Celebrity Endorser: A Social Adaptation Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Research 11 (4):954–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/209029

- Knoll, Silke, Martin Eisend, and Josefine Steinhagen. 2011. “Gender Roles in Advertising. Measuring and Comparing Gender Stereotyping on Public and Private TV Channels in Germany.” International Journal of Advertising 30 (5):867–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-30-5-867-888

- Kohlbacher, Florian, Michael Prieler, and Shigeru Hagiwara. 2011. “The Use of Older Models in Japanese TV Advertising: Practitioner Perspective vs. Consumer Opinions.” Keio Communication Review 33:25–42.

- Kohlbacher, Florian, Michael Prieler, and Shigeru Hagiwara. 2014. “Japan's Demographic Revolution? A Study of Advertising Practitioners' Views on Stereotypes.” Asia Pacific Business Review 20 (2):249–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2013.841451

- Kolbe, Richard H., and Melissa S. Burnett. 1992. “Perceptions of Elderly and Young Adult Respondents toward the Portrayal of the Elderly in Advertising: Implications to Advertising Managers.” Journal of Marketing Management 2 (1):76–85.

- Kotter-Grühn, Dana, Anna E. Kornadt, and Yannick Stephan. 2015. “Looking beyond Chronological Age: Current Knowledge and Future Directions in the Study of Subjective Age.” Gerontology 62 (1):86–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000438671

- Kruse, Adreas, and Eric Schmitt. 2006. “A Multidimensional Scale for the Measurement of Agreement with Age Stereotyes in Social Interaction.” Aging & Society 26:393–411.

- Kuppelwieser, Volker G., and Philipp Klaus. 2021. “Revisiting the Age Construct: Implications for Service Research.” Journal of Service Research 24 (3):372–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520975138

- Kvasnicka, Brian, Barbara Beymer, and Richard M. Perloff. 1982. “Portrayals of the Elderly in Magazine Advertisements.” Journalism Quarterly 59 (4):656–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908205900423

- Kwon, Mina, Geetanjali Saluja, and Rashmi Adaval. 2015. “Who Said What: The Effects of Cultural Mindsets on Perceptions of Endorser-Message Relatedness.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 25 (3):389–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.01.011

- Langmeyer, Lynn. 1984. “Senior Citizens and Television Advertisements: A Research Note.” Current Issues and Research in Advertising 7 (1):167–78.

- Langmeyer, Lynn. 1993. “Advertising Images of Mature Adults: An Update.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 15 (2):81–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1993.10505005

- Makita, Meiko, Amalia Mas-Bleda, Emma Stuart, and Mike Thelwall. 2021. “Ageing, Old Age and Older Adults: A Social Media Anaylsis of Dominant Topics and Discourses.” Ageing and Society 41 (2):247–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19001016

- Mathes, Eugene W., Susan M. Brennan, Patricia M. Haugen, and Holly B. Rice. 1985. “Ratings of Physical Attractiveness as a Function of Age.” The Journal of Social Psychology 125 (2):157–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1985.9922868

- Mazis, Michal B., Debra Jones Ringold, Elgin S. Perry, and Daniel W. Denman. 1992. “Perceived Age and Attractiveness of Models in Cigarette Advertisements.” Journal of Marketing 56 (1):22–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600104

- Milliman, Ronald E., and Robert C. Erffmeyer. 1989. “Improving Advertising Aimed at Seniors.” Journal of Advertising Research 29:31–6.

- Mohammed, Farahnaz. 2021. “How 'Grance and Frankie' Is Changing How Women View Ageing.” Girls' Globe. Accessed October 30, 2021. https://www.girlsglobe.org/2017/08/18/grace-frankie-changing-women-view-ageing/?doing_wp_cron=1635607018.2241809368133544921875.

- Moschis, George P. 2021. “The Life Course Paradigm and Consumer Behavior: Research Frontiers and Future Directions.” Psychology & Marketing 38 (11):2034–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21586

- Nelson, Susan Logan, and Ruth Belk Smith. 1988. “The Influence of Model Age or Older Consumers' Reactions to Print Advertising.” Current Issues and Research in Advertising 11 (1-2):189–212.

- Niu, Xiaochun, and Gang Zhou. 2019. “A Study on Images of the Elderly in Advertising.” The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology 1 (5):277–82.

- Nunan, Daniel, and Maria Laura Di Domenico. 2019. “Older Consumers, Digital Marketing, and Public Policy: A Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 38 (4):469–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0743915619858939

- Orth, Ulrich R., and Denisa Holancova. 2004. “Men's and Women's Responses to Sex Role Portrayals in Advertisements.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 21 (1):77–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.05.003

- Osgood, Charles E., and Percy H. Tannenbaum. 1955. “The Principle of Congruity in the Prediction of Attitude Change.” Psychological Review 62 (1):42–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048153

- Pollay, Richard W. 1986. “The Distorted Mirror: Reflections on the Unintended Consequences of Advertising.” Journal of Marketing 50 (2):18–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1251597

- Pollay, Richard W. 1987. “On the Value of Reflections on the Values in “the Distorted Mirror”.” Journal of Marketing 51 (3):104–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1251651

- Prieler, Michael. 2020. “Gender Representations of Older People in the Media: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go from Here?” Asian Women 36 (2):73–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2020.6.36.2.73

- Prieler, Michael, and Florian Kohlbacher. 2016. Advertising in the Aging Society. Understanding Representations, Practitioners, and Consumers in Japan. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Prieler, Michael, Florian Kohlbacher, Shigeru Hagiwara, and Akie Arima. 2010. “Older Celebrity versus Non-Celebrity Television Advertising: A Japanese Perspective.” Keio Communication Review 32:5–23.

- Ringold, Debra Jones. 2016. “Assumptions about Consumers, Producers, and Regulators: What They Tell Us about Ourselves.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 1 (3):341–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/686983

- Roberts, Scott D., and Nan Zhou. 1997. “The 50 and Older Characters in the Advertisements of Modern Maturity: Growing Older, Getting Better?” The Journal of Applied Gerontology 16 (2):208–20.

- Robinson, Thomas E. 1998. Portraying Older People in Advertising. Magazine, Television, and Newspapers. New York: Garland Publishing.

- Rogers, Everett M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

- Rößner, Anna, Yaniv Gvili, and Martin Eisend. 2021. “Explaining Consumer Responses to Ethnic and Religious Minorities in Advertising: The Case of Israel and Germany.” Journal of Advertising 50 (4):391–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1939201

- Rotfeld, Herbert J., Leonard N. Reid, and Gary B. Wilcox. 1982. “Effect of Age of Models in Print Ads on Evaluation of Product and Sponsor.” Journalism Quarterly 59 (3):374–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908205900303

- Shavitt, Sharon, Suzanne Swan, Tina M. Lowrey, and Michaela Wänke. 1994. “The Interaction of Endorser Attractiveness and Involvement Depends on the Goal That Guides Message Processing.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 3 (2):137–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(08)80002-2

- Shoenberger, Heather, Eunjin (Anna) Kim, and Erika K. Johnson. 2020. “#BeingReal about Instagram Ad Models: The Effects of Perceived Authenticity.” Journal of Advertising Research 60 (2):197–207.

- Skurpin, Karina, Ardion Beldad, and Mark Tempelman. 2019. “The Impact of Advertising Appeals on Consumers' Perception of an Advertisement for a Technical Product and the Moderating Roles of Endorser Type and Endorser Age.” In Academy of Marketing Science Annual Conference, Vancouver, Canada, 189–99.

- Smith, Mickey C. 1976. “Portrayal of the Elderly in Prescription Drug advertising. A pilot study.” The Gerontologist 16 (4):329–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/16.4.329

- Smith, Ruth B., George P. Moschis, and Roy L. Moore. 1982. “Some Advertising Effects on the Elderly Consumer.” In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Southern Marketing Association, Dallas, TX, 149–52.

- Stephens, Nancy. 1982. “The Effectiveness of Time-Compressed Television Advertisements with Older Adults.” Journal of Advertising 11 (4):48–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1982.10672821

- Swayne, Linda E., and Alan J. Greco. 1987. “The Portrayal of Older Americans in Television Commercials.” Journal of Advertising 16 (1):47–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1987.10673060

- Szmigin, Isabelle, and Marylyn Carrigan. 2000. “Does Advertising in the UK Need Older Models?” Journal of Product & Brand Management 9 (2):128–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420010322170

- Trading Economics. 2021. “Retirement Age Men.” Accessed June 30, 2021. https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/retirement-age-men.

- Tunaley, J. R., S. Walsh, and P. Nicolson. 1999. “‘I'm Not Bad for My Age?': The Meaning of Body Size and Eating in the Lives of Older Women.” Ageing and Society 19 (6):741–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X99007515

- United Nations. 2019. World Population Ageing 2019. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations Population Division. 2021. “World Population Prospects 2019.” Accessed July 6, 2021. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/.

- Ward, Russell A. 1984. “The Marginality and Salience of Being Old: When Is Age Relevant?” The Gerontologist 24 (3):227–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/24.3.227

- Williams, Patti, and Aimee Drolet. 2005. “Age-Related Differences in Responses to Emotional Advertisements.” Journal of Consumer Research 32 (3):343–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/497545

- Wolf, Angelika, and Sebastian Seebauer. 2014. “Technology Adoption of Electric Bicycles: A Survey among Early Adopters.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 69 (November):196–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2014.08.007

- Ylänne, Virpi, and Angie Williams. 2009. “Positioning Age: Focus Group Discussions about Older People in TV Advertising.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2009 (200):171–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/IJSL.2009.050

- Ylänne, Virpi, Angie Williams, and Paul Mark Wadleigh. 2010. “Ageing Well? Older People's Health and Well-Being as Portrayed in UK Magazine Advertisements.” International Journal of Ageing and Later Life 4 (2):33–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.094233

- Yoon, Hyunsun, and Helen Powell. 2012. “Older Consumers and Celebrity Advertising.” Ageing and Society 32 (8):1319–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1100095X

- Zhang, Jiekai. 2018. “Regulating Advertising Quantity: Is This Policy Efficient?” NET Institute Working Paper No. 16-06.

- Zhang, Yan Bing, Jake Harwood, Angie Williams, Virpi Ylänne-McEwen, Paul Mark Wadleigh, and Caja Thimm. 2006. “The Portrayal of Older Adults in Advertising: A Cross-National Review.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 25 (3):264–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X06289479

- Zhou, Nan, and Mervin V. T. Chen. 1992. “Marginal Life after 49: A Preliminary Study of the Portrayal of Older People in Canadian Consumer Magazine Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 11 (4):343–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1992.11104510