Abstract

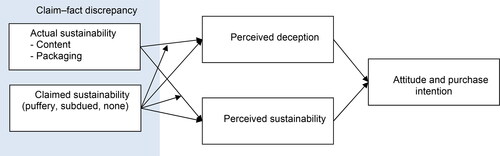

Firms often emphasize “green” benefits for products that are only partially more sustainable than alternatives (e.g., a more sustainable packaging with similar product ingredients). The current article posits that such strategies can lead to a perceived claim–fact discrepancy and examines to what extent this makes consumers feel deceived and detracts from attitudes and purchase intentions, even though consumers can intrinsically value the (partial) sustainability improvements. In addition, given that marketing communication often relies on puffery such as exaggerated language and (visual) hyperbole, the article also investigates the effect of the use of puffery versus more subdued claims. Findings from two experiments unveil that when the actual sustainability of packaged products is (partially) discrepant with an overt sustainability claim, this leads to higher perceived deception. The use of puffery has both pros and cons, such that it adds to perceived sustainability but also to perceived deception, and it moderates the effects of actual sustainability. Furthermore, the results provide initial support for the idea that sustainability improvements in only peripheral attributes (packaging) are perceived as more deceptive than sustainability improvements in only central attributes (product contents).

Producers of consumer packaged goods face ever-increasing pressures to reduce the environmental impact of their products. One way in which firms respond to such pressures is through the design and introduction of new and modified products that are “greener” than their conventional counterparts. To draw consumer attention to such product innovations, firms are likely to use sustainability claims in their advertising campaigns.

Environmental gains of these product innovations often refer only to specific attributes or components, for instance, the product’s packaging. In other words, these products contain at least one (more) sustainable attribute, but this does not mean that the entirety of the offering is equally environmentally friendly (Gershoff and Frels Citation2015). While this in itself is not problematic, firms often commit the first “sin of greenwashing” by using advertising claims that suggest such products as a whole are green, emphasizing a selection of attributes, while ignoring the performance on other attributes (TerraChoice Citation2010). For example, producers of bottled water (a product widely criticized for its large environmental impact) may opt to use bio-based bottles and push the environmentally improved packaged product as “sustainable” even though no adjustments are made to the environmental impact of the water itself.

Greenwashing is highly prevalent: A review of 1,000 green products revealed that at least 95% committed greenwashing in some form (TerraChoice Citation2010). Due to this, consumers can become skeptical and reluctant to purchase environmentally improved products primarily due to the way that such products are advertised by firms, even though consumer might intrinsically value such sustainability attributes (Goh and Balaji Citation2016). Such a response would devalue the actual (partial) environmental improvements made, because consumers penalize firms for the perceived deceptiveness in their ads. This can leave firms in a challenging position where they want to communicate the sustainability benefits of their products as a competitive advantage but, at the same time, also need to take care that consumers do not see this communication as deceptive. This dilemma is especially relevant to credence attributes (i.e., attributes that consumers are unable to verify; Ford, Smith, and Swasy Citation1990), such as sustainability. Thus, firms need to decide if, and how, to communicate (partially) improved sustainability.

The current article centers its contribution around claim–fact discrepancies between (1) the actual environmental performance of packaged products and (2) general sustainability claims made by firms. It examines effects on perceived deception and perceived sustainability, and subsequently on attitudes (toward the product and the firm) and purchase intentions. We consider the actual environmental performance of the packaged product in conjunction with the use of puffery in sustainability claims. This allows us to shed light on what type of sustainability improvements can best be communicated in the marketplace (i.e., for “fully” or “partially” sustainable products) and with what kind of claim (i.e., with or without the use of puffery). We consider the distinction between the sustainability of the packaging versus that of the product contents to examine effects of different kinds of partial sustainability (i.e., when either packaging or product content is sustainable both together are not).

Regarding the claim–fact discrepancy, we investigate the extent to which using a general environmental claim for a packaged product that is only partially sustainable is perceived as deceptive by consumers (compared to packaged products that are wholly sustainable). We also consider to what extent consumer inferences of deception counteract the (positive) effects of improved environmental performance on consumers’ purchase intentions and overall attitudes toward packaged products. In addition, building on theories of attribute centrality (Gershoff and Frels Citation2015; Sloman, Love, and Ahn Citation1998), we consider that consumers might be more likely to feel deceived when firms claim general sustainability of packaged products for which only a peripheral component (packaging) is sustainable while a central component (product contents) is not, compared to the other way around.

Another main objective of this article is to investigate the role of claim puffery. In advertisements, specific benefits are often emphasized, not uncommonly in a somewhat exaggerated, overstated fashion (Goldberg and Hartwick Citation1990). Puffery is highly prevalent in general advertising practice and can be an effective tool to increase sales (Kopalle et al. Citation2017; Kopalle and Lehmann Citation2015) in part because it highlights the comparative advantage of the “puffed up” benefit (Chakraborty and Harbaugh Citation2014). Yet scarcely any research has been conducted regarding the effects of advertising puffery when it comes to promoting ethical attributes such as environmental sustainability. Prior research suggests that consumers are critical when evaluating products with ethical attributes and that skepticism plays an important role in consumer response to claims about such attributes (Skarmeas and Leonidou Citation2013). Given that greenwashing is very prevalent (TerraChoice Citation2010) and consumer skepticism is on the rise (Goh and Balaji Citation2016), it also seems plausible to expect that puffery in advertising may easily backfire when it pertains to credence attributes such as sustainability. Consumers will probably be less willing to give firms the benefit of the doubt (and may be more critical) when it comes to trusting environmental claims compared to claims that are not as morally loaded or that can be verified more easily. Perhaps as a way of addressing this, some firms have begun to forgo puffery for a more down-to-earth approach (or they avoid explicit environmental claims altogether). For example, in a newspaper ad on recyclable packaging, Coca-Cola stated that they are “aware that more work needs to be done,” thus deliberately framing their actions as a work in progress. This may be less likely to induce feelings of deception; at the same time, it could attenuate the effect on perceived sustainability.

Summarizing, in the context of general sustainability claims, this article investigates to what extent different degrees of partial (product contents versus packaging) sustainability lead to perceived deception. Moreover, we examine whether puffery in advertising claims leads to increased perceived deception, in comparison to the situation where the claim is subdued or absent. The claim–fact discrepancy arising from the difference between actual sustainability of packaging and product contents and what is suggested by the (puffed up or moderate) sustainability claim, is expected to also influence perceived sustainability. We expect that both these perceptions in turn affect attitudes toward the product (and the firm) and purchase intentions. To our knowledge, this approach combining various forms of partial versus full sustainability and its possible interplay with different advertisement styles has not been studied before in the literature and presents a more comprehensive view on sustainability (marketing) than what has typically been examined.

Theoretical Background

Deception and Claim–Fact Discrepancies

Because greenwashing has become highly prevalent, consumers have become skeptical about sustainability claims (Aji and Sutikno Citation2015; Goh and Balaji Citation2016). Furthermore, consumers generally cannot verify the effects of the claim themselves; hence, when they receive (independent) information that the firm’s claim is not (or not entirely) truthful, consumers are likely to feel deceived. Perceived deception results from the (perceived) discrepancy between the impression that the firm generates about the packaged product and its actual performance (Darke and Ritchie Citation2007; Foreh and Grier Citation2003; Wagner, Lutz, and Weitz Citation2009), which we refer to as claim–fact discrepancy (Gardner Citation1975).

With regard to this discrepancy, Darke and Ritchie (Citation2007) state, “Consumers do not need to know exactly how they were misled by an advertising claim; they merely need to perceive a discrepancy between the impression that the advertisement generated and the performance of the product to know they have been fooled” (p. 115). In previous research, claim–fact discrepancies have been found to contribute to constructs similar to deception, such as consumer perceptions of corporate hypocrisy (Wagner, Lutz, and Weitz Citation2009), skepticism (Foreh and Grier Citation2003), and low advertising credibility (Atkinson and Rosenthal Citation2014; Jain and Posavac Citation2001). Discrepancies also increase the likelihood that consumers infer ulterior motives because they are more likely to engage in cognitive processing to reconcile the discrepant information (Ellen, Webb, and Mohr Citation2006; Meyers-Levy and Tybout Citation1989; Foreh and Grier Citation2003; Kelley Citation1973).

We consider that when firms make sustainability claims that are not, or are only partially, supported by the packaged product’s actual environmental performance, the firm generates a claim–fact discrepancy, which leads to consumer inferences of deception. This perceived deception is expected to be largest when neither packaging nor product contents are actually sustainable (full discrepancy) and smaller when the packaged product is at least partially sustainable (partial discrepancy). Alternatively, when both packaging and product contents are sustainable (i.e., consistent with the claim), perceived deception should be lowest. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H1: In the presence of a sustainability claim for a packaged product, perceived deception is lowest when both packaging and product are highly sustainable, higher when either of these are less sustainable, and highest when both packaging and product are low in sustainability.

Packaging versus Product Contents Sustainability and Conceptual Centrality

Actual sustainability of a packaged product is a function of both its contents and its packaging. Drawing upon the concept of attribute centrality, we expect that products with sustainable packaging but less sustainable contents may have a different effect on consumer perceptions compared to products with sustainable contents but less sustainable packaging. Prior research in the domain of attribute centrality (Hadjichristidis et al. Citation2004; Sloman, Love, and Ahn Citation1998) defined (conceptual) centrality of attributes in terms of how defining these attributes are for objects, which is assessed by considering how transformable (or mutable) they are, while retaining the same concept of that object (Sloman, Love, and Ahn Citation1998). Central attributes are least mutable and contribute most to a concept’s coherence; they are integral to the mental representation of an object (Sloman, Love, and Ahn Citation1998). Central attributes are also more diagnostic to categorizing the object than are peripheral attributes (Gershoff and Frels Citation2015), because if a highly central attribute were transformed, it would require a different categorization of the object as a whole. Peripheral attributes, in contrast, can be altered more easily without changing the concept or categorization of the object.

The criteria that have been proposed to indicate the degree of centrality (Sloman, Love, and Ahn Citation1998) can be applied to the product–packaging distinction. The conceptual centrality criterion considers, for example, how easy it would be to consider a product without its packaging. Such a concept can be construed quite easily, for example, by considering a soda beverage in a drinking glass or even as being spilled; thus, packaging type is not crucially defining for the beverage product. Conversely, it would be impossible to consider a beverage which does not contain liquid ingredients but which is gaseous or solid in nature. Thus, packaging is more likely to be conceptually peripheral, whereas “internal” attributes related to product contents and ingredients are central.

Recent research has demonstrated that the centrality of green attributes affects consumer response (Gershoff and Frels Citation2015): Products that have similar environmental benefits are perceived as more sustainable when the benefits stem from a central rather than a peripheral attribute. In line with this, we consider that for partial discrepancies, packaging and product contents may have different effects because their centrality differs. As alterations of peripheral attributes are less likely to transform mental representations of the packaged product, such innovations may be perceived as more superficial. This could signal that a company could have done a more thorough innovation but has forgone it in favor of a less transformative innovation. Therefore, consumers should feel more deceived when packaging is sustainable while the product content itself is not, than when the opposite occurs:

H2: Partial discrepancies wherein a peripheral attribute (packaging) is sustainable but a central attribute (product contents) is not induce greater perceived deception than do partial discrepancies wherein a central attribute is sustainable but a peripheral attribute is not.

Centrality pertains to what defines an object. Importantly, we propose that making only packaging sustainable is perceived as more deceptive because packaging is more peripheral in the mental representation of packaged products, and not just because packaging sustainability could be perceived as having a lesser environmental impact than product contents’ sustainability.

Attitudes and Purchase Intentions

Perceived deception is likely to lower consumer attitudes toward the product and the firm, as well as purchase intentions. Prior research has shown that perceived greenwashing negatively affects brand association and decreases purchase intentions (Akturan Citation2018; Zhang et al. Citation2018). We thus expect that the deception that consumers perceive when firms make sustainability claims that are not fulfilled or are only partially fulfilled will negatively affect their attitudes and purchase intentions. Lower actual sustainability could decrease attitudes and purchase intentions due to lower perceived sustainability as well. However, compared to fully unsustainable products, for partially sustainable packaged products, there may still also be a positive contribution toward attitudes and purchase intentions resulting from perceived sustainability, even when the claim is not fulfilled. We hypothesize:

H3(a): In the presence of a sustainability claim, lower actual sustainability will decrease attitudes and purchase intentions due to increased perceived deception.

H3(b): In the presence of a sustainability claim, lower actual sustainability will decrease attitudes and purchase intentions due to decreased perceived sustainability.

The Role of Claim Puffery in Advertisements

We now turn to the effects of puffery. Thus far, we have considered sustainability claims in broad, general terms. Realistically, however, firms might use various types of claims. In particular, advertisements and promotional activities often involve forms of puffery, defined as sales claims that involve exaggerations, superlatives, or hyperbole which can potentially be deceptive but which generally stay within what is legally permitted (Richards Citation1990). Thus, puffery stretches the truth somewhat and thereby generates expectations (e.g., through ads or promotional stimuli) that can reasonably be expected to exceed actual product performance (McQuarrie and Mick Citation1996; Toncar and Fetscherin Citation2012).

Puffery may contain both verbal and visual elements. Verbal components often refer to the aforementioned use of exaggeration and superlatives (Callister and Stern Citation2007). Visuals can contribute to puffery, for example, through emphasizing specific color palettes, lighting, and the inclusion of objects that signal boldness in advertisements (Toncar and Fetscherin Citation2012). Visual hype and hyperbole may also be used (McQuarrie and Mick Citation1996; Toncar and Fetscherin Citation2012). For example, 7 Up used a (controversial) advertisement depicting a 7 Up soda can hanging from the branch of a tree, a form of visual hyperbole. The ad further used a predominantly green color palette throughout, visually highlighting the can, and the headline “Now 100% natural.”

Positive and Negative Effects of Puffery

Negative effects of puffery occur because puffery involves distortions of truth that overstate the offering (McQuarrie and Mick Citation1996; Obermiller, Spangenberg, and MacLachlan Citation2005; Richards Citation1990; Callister and Stern Citation2007; Darke and Ritchie Citation2007). For example, more extreme ad claims, such as “the very best product,” tend to be seen as less credible and to negatively impact product evaluations compared to less extreme ad claims, such as “better than most products” (Goldberg and Hartwick Citation1990). Similarly, research regarding environmental advertisement shows that consumers tend to experience higher levels of discomfort from ads with particularly strong claims compared to less pronounced claims, and consider these ads less believable. This suggests that claim puffery increases perceptions of deception (Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2014).

In addition to this main effect, we expect that claim puffery influences the effect of full (both contents and packaging) versus partial (only contents or packaging) actual sustainability on perceived deception. As mentioned, research on advertising shows that if an advertisement does not match actual performance, consumers can become skeptical and may feel deceived (Friestad and Wright Citation1994; Wagner, Lutz, and Weitz Citation2009), ultimately leading to consumer dissatisfaction (Kopalle and Lehmann Citation2015; Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2014). Puffery sets high expectations, and when a product is only partially sustainable, this leads to a high perceived claim–fact discrepancy. Thus, we expect that when puffery is used in communicating sustainability, a lack of actual sustainability is especially likely to backfire through increased perceived deception. Conversely, providing subdued claims or making no sustainability claim whatsoever does not set these high expectations. In such cases, the claim–fact discrepancy is low or absent, and partial actual sustainability will be less likely to lead to feelings of deception. Thus:

H4(a): Claim puffery increases perceptions of deception.

H4(b): Claim puffery moderates the effect of actual sustainability on attitudes and purchase intentions through perceived deception: with claim puffery, the effect of actual sustainability is larger than when the claim is subdued or absent.

Although this discussion has focused on the cons of puffery, research also attests that puffery can lead to various firm-beneficial effects, such as increased perceived sustainability. Indeed, it has been argued that puffery would not be used if it did not work in some way (Haan and Berkey Citation2002; Toncar and Fetscherin Citation2012). Various explanations have been offered for the potential positive effects of puffery. Sometimes consumers believe puffery to a relatively large extent and consequently make inferences (e.g., quality judgments) based on these implied facts (Haan and Berkey Citation2002; Kamins and Marks Citation1987; Lee Citation2014). Yet initial credibility does not seem a prerequisite for puffery to exert effects on consumer beliefs, as these beliefs have been shown to change after exposure to a claim even when this claim was perceived as relatively incredible (Cowley Citation2006). This may occur because the positive message conveyed by a claim continues to have a strong effect on consumers, while the discounting cue (i.e., the firm has a self-interest) is forgotten more easily (cf. the sleeper effect; Kumkale and Albarracín Citation2004; Pratkanis et al. Citation1988). As a consequence, the targeted effects of the ad linger, while the disclaimer due to exaggeration is forgotten (Cowley Citation2006). In our case, this suggests a positive effect of claim puffery on perceptions of sustainability.

In addition, we also expect that puffery will influence the effect of actual sustainability on perceived sustainability, which subsequently will affect attitudes and purchase intentions. Because consumers tend to form sustainability inferences based on the claim (Toncar and Fetscherin Citation2012), and are less likely to adjust these even when they reject the advertisement (Cowley Citation2006), we expect that perceived sustainability is relatively high for claims that use puffery, and full versus partial actual sustainability will have a more limited effect in this case. Puffery will lead consumers to store associated beliefs in memory, which will continue to have an effect, independent of information about actual sustainability. In contrast, when the claim is moderate, we expect that perceived sustainability will depend more strongly on actual sustainability. For moderate claims, associated beliefs in memory should be less strongly formed and more easily influenced by information about actual sustainability. We thus predict:

H5(a): Claim puffery increases perceptions of sustainability.

H5(b): Claim puffery moderates the effect of actual sustainability on attitudes and purchase intentions through perceived sustainability; with claim puffery the effect of actual sustainability is lower than when the claim is subdued or absent.

Research Overview

provides our conceptual model. We present two experiments using scenarios with packaged beverage products to test the hypotheses. Experiment 1 tests hypotheses 1 through 3. It creates claim–fact discrepancies by providing a general sustainability claim (kept constant) by a firm, paired with independent, third-party assessments of the actual separate environmental impacts of packaging and product contents. Packaging’s and product contents’ actual sustainability vary across three levels (low, medium, high). Experiment 2 provides additional tests for hypotheses 1 through 3, and also tests hypotheses 4 and 5 by manipulating the claim–fact discrepancy by varying both packaging’s and product contents’ actual sustainability, as well as the firm’s general sustainability claim through advertisements containing either puffery, a subdued claim, or no claim. In this experiment, actual sustainability varies across three conditions: both packaging and contents high; only packaging high (and contents low); only contents high (and packaging low). In each experiment, we test the mediating effects of both perceived sustainability and perceived deception on consumer attitudes and purchase intentions.

Experiment 1: Claim–Fact Discrepancy

Participants and Design

A total of 609 Dutch consumers (Mage = 41.64, SDage = 13.75, rangeage = 18 to 65; 50% male) were recruited from an online panel through e-mail invitations. They received a small financial compensation for participating. Education levels varied as follows: 19.4% had a low education level (primary education or a lower secondary/vocational education), 45.5% had a medium education level (vocational degree or advanced secondary education), and 35.2% had a high education level (bachelor’s degree or higher). Participants had a moderately high level of environmental concern (M = 5.00 on a scale from 1 to 7; see Appendix B for items). Gender, age, education, and environmental concern did not significantly differ across conditions.

The experiment consisted of a 3 (packaging sustainability: high, medium, low) × 3 (product contents sustainability: high, medium, low) between-subjects design. Thus, the experiment contained one claim-consistent condition (both packaging and contents sustainability high), one condition that was fully discrepant (both packaging and contents sustainability low) and seven conditions that were to various extents partially discrepant with the claim (e.g., packaging high, contents low).

Stimuli and Procedure

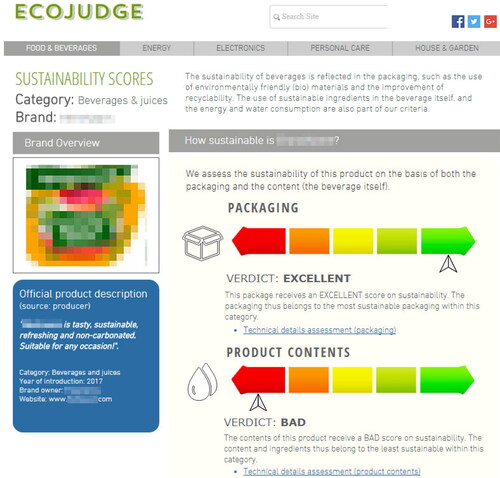

Participants were instructed to evaluate an upcoming beverage product from a major company in the packaged beverages industry. Company and brand name were blurred out to avoid possible effects of brand recognition and preference. Participants were told that this was done in the interest of the study’s purpose. They first read a short text stating that the company wanted to introduce a new sustainable noncarbonated beverage product, which had been rated on its environmental impacts. The environmental assessment was stated to be carried out by a (fictitious) independent organization called Ecojudge, which rates the sustainability of various products and publishes these results online. Ecojudge was stated to be well-known abroad, but relatively unfamiliar in the country of the study, to account for participants not recognizing the fictitious name. Ecojudge was furthermore introduced as a nonprofit organization that was renowned for its reliable ratings. Participants were informed that the producing firm claimed the beverage product to be sustainable.

Next, participants saw an image of a web page with Ecojudge’s ratings of the environmental friendliness of the packaging and product (Appendix A). The web page’s design was based on real-world initiatives that rank brand/product sustainability, such as Rank a Brand (www.rankabrand.org), the Greenwashing Index (www.greenwashingindex.com), and GoodGuide (www.goodguide.com). Package and beverage sustainability were displayed graphically with ratings of “Bad,” “Average,” or “Excellent,” depending on condition.

After viewing the web page, participants filled in questions measuring purchase intentions (measured on a slider scale ranging from 1 to 100), attitudes (using 7-point semantic differential scale items), and the proposed mediators perceived sustainability and perceived deception (using 7-point Likert scale items). For perceived deception, we combined items related to general feelings of deception and more specifically greenwashing. Finally, background characteristics were asked, including demographics and environmental concern. Appendix B provides the items and reliability of the scales.

Results

Perceived Deception and Perceived Sustainability

To test our first hypothesis, we examined effects of packaging and content sustainability on perceived deception and perceived sustainability using separate analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Results showed significant main effects of packaging sustainability on perceived deception (F (2, 609) = 11.46, p < .001, ηp2 = .04) and sustainability (F (2, 609) = 39.92, p < .001, ηp2 = .12). Product contents sustainability also showed significant main effects on both perceived deception (F (2, 609) = 40.37, p < .001, ηp2 = .12) and sustainability (F (2, 609) = 44.29, p < .001, ηp2 = .13). There were no significant interaction effects. The pattern of means for both packaging and product contents sustainability () was in line with expectations, such that a higher level of packaging/product contents sustainability led to lower perceived deception and higher perceived sustainability. Paired comparisons showed significant effects among all conditions, both for packaging and product content sustainability, except for the difference between medium and high packaging sustainability for perceived deception (p = .09). Overall, the results were in line with hypothesis 1: In the presence of a sustainability claim, perceived deception increased when the level of actual packaging or product sustainability decreased (i.e., the claim–fact discrepancy increased). These effects were more pronounced for product contents sustainability, suggesting a possible effect of attribute centrality, which we test next.

Table 1. Experiment 1: Means and standard deviations per condition.

Centrality Effects

To test for asymmetry in the effects of packaging and product contents sustainability on perceived deception (hypothesis 2), a contrast was specified in the ANOVA for perceived deception, taking the difference between (1) the three conditions where product contents sustainability exceeded packaging sustainability versus (2) the three conditions where packaging was more sustainable than product contents. Results showed a significant difference (Mcontents > packaging = 3.93 versus Mpackaging > contents = 4.25; F (1, 406) = 7.25, p = .007). Thus, when product contents sustainability exceeded packaging sustainability, deceptiveness was lower. As a check, the same contrast was tested for perceived sustainability, which revealed no significant difference (Mcontents > packaging = 3.93 versus Mpackaging > contents = 3.84; p = .60), ruling out that this centrality effect on deception was caused by a difference in perceived environmental impacts of packaging and product contents. Overall, results were supportive of hypothesis 2: partial discrepancies wherein a peripheral attribute (packaging) was sustainable but where a central attribute (product contents) was not led to higher perceived deception than vice versa.

Purchase Intentions and Attitudes

Two ANOVAs were conducted to examine the effects of packaging and product contents sustainability levels on purchase intentions and attitude toward the packaged product. Effects on attitude toward the firm were also investigated. As results for these effects were similar to attitude toward the packaged product, we only report results of the latter. Results showed significant main effects of packaging sustainability on purchase intentions (F (2, 609) = 6.031, p = .003, ηp2 = .02) and attitude toward the packaged product (F (2, 609) = 13.34, p < .001, ηp2 = .04). Post hoc tests (least significant difference [LSD]) showed that only the difference between low and high packaging sustainability reached significance for purchase intentions (p = .001), while the differences between low and medium, and between low and high, were significant for attitudes (p = .001 and p < .001, respectively). Similarly, there were significant main effects of product contents sustainability on purchase intentions (F (2, 609) = 28.25, p < .001, ηp2 = .09) and attitude toward the packaged product (F (2, 609) = 72.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .19). For both intentions and attitudes, we found significant differences between all levels (low, medium, and high; all p < .001). There were no significant interaction effects. provides means and standard deviations.

Indirect Effects on Purchase Intentions and Attitudes

To test whether the effects of packaging and product contents sustainability on attitudes and purchase intentions were mediated (in parallel) by perceived deception and perceived sustainability (hypothesis 3 and ), we used the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes and Preacher Citation2014). For both analyses on attitudes and on purchase intentions, two mediation analyses were conducted to get bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect main effects of both packaging and product contents sustainability. The first analysis included indicator-coded dummies for packaging sustainability as the independent variable and product contents sustainability dummies as covariates. The second analysis swapped these variables, such that dummies for product contents sustainability were the independents and dummies for packaging sustainability were the covariates. Low levels of sustainability were the reference categories. Significance was based on 10,000 bootstrap samples and 95% CIs. Results showed identical patterns for attitudes and purchase intentions. For brevity we report results for purchase intentions only.

Results from the first analysis showed significant indirect effects of the packaging sustainability dummies on purchase intentions via perceived sustainability (low versus medium: b = 2.85, SE = 0.81, CI 95 [1.38, 4.59]; low versus high: b = 5.46, SE = 1.14, CI 95 [3.32, 7.81]) and via perceived deception (low versus medium: b = 2.85, SE = 0.73, CI 95 [0.56, 3.40]; low versus high: b = 2.91, SE = 0.87, CI 95 [1.39, 4.82]). The contrast between the medium and high packaging sustainability levels was significant for perceived sustainability (medium versus high: b = 2.60, SE = 0.73, CI 95 [1.26, 4.14]), although not significant for perceived deception (medium versus high: b = 1.06, SE = 0.63, CI 95 [−0.08, 2.42]). There was no significant remaining direct effect (p = .83), indicating full mediation.

The results from the second analysis with product contents sustainability showed similarly significant effects through perceived sustainability (low versus medium: b = 3.63, SE = 0.87, CI 95 [1.03, 5.37]; low versus high: b = 5.68, SE = 1.19, CI 95 [3.44, 8.10]) and perceived deception (low versus medium: b = 3.63, SE = 0.87, CI 95 [2.06, 5.48]; low versus high: b = 5.45, SE = 1.11, CI 95 [3.40, 7.81]). The contrast between the medium and high product contents sustainability levels was significant for perceived sustainability (medium versus high: b = 2.04, SE = 0.71, CI 95 [0.80, 3.59]) as well as perceived deception (medium versus high: b = 1.81, SE = 0.67, CI 95 [0.61, 3.23]). The omnibus test also showed a significant direct effect (p = .01), indicating partial mediation.

In summary, results showed that mediation occurred in line with expectations (hypothesis 3). The discrepancy between actual and claimed sustainability affected both attitudes and purchase intentions through the two mediators. When the discrepancy decreased, this led to higher attitudes and purchase intentions, both due to lower perceived deception and higher perceived sustainability.

Discussion

Experiment 1 indicates that when discrepancies between the firm’s claimed sustainability and its actual sustainability arise, consumers feel deceived. Specifically, the higher the discrepancy, moving from fully discrepant to partially discrepant (i.e., partially sustainable) to fully sustainable, the higher the perceived deception.

Moreover, the outcomes support the hypothesis of asymmetry due to conceptual centrality, such that the perceived deception from partially sustainable product-packaging combinations is higher when only a peripheral attribute (packaging) is sustainable than when only a central attribute (contents) is sustainable, in line with hypothesis 2. This occurs even though both contents and packaging sustainability affect the overall perceived sustainability equally. Mediation analyses furthermore show that effects of the claim–fact discrepancy on attitudes and purchase intentions are mediated through both perceived deception and perceived sustainability. In conclusion, the results of this experiment support all tested hypotheses (hypotheses 1 through 3). In the next experiment, we expand upon these results by examining the effects of claim–fact discrepancies due to differences not only in actual sustainability but also in claimed sustainability (i.e., puffery).

Experiment 2: Claim Puffery

Experiment 2 seeks to further deepen the insights gained in Experiment 1 in a controlled lab setting. It also tests effects of the claim–fact discrepancy as a function of different claims (puffery, subdued, claim absent) in addition to the (partial) actual sustainability of the product-packaging combination.

Participants and Design

A total of 409 eligible responses were collected from a Dutch university student sample (Mage = 20.75, SDage = 2.10; 75% female; moderately high environmental concern, M = 5.37), excluding 13 participants who failed an attention check. The experiment consisted of a 3 (claim: puffery, subdued, claim absent) × 3 (actual sustainability rating: packaging and product contents [both] sustainable, packaging sustainable [packaging only], product contents sustainable [contents only]) between-subjects design. The latter factor essentially combined the two factors of Experiment 1, with sustainability for packaging and contents set at high and/or low. Experiment 2 thus compared between two types of partial discrepancies and one wholly sustainable (claim-consistent) condition.

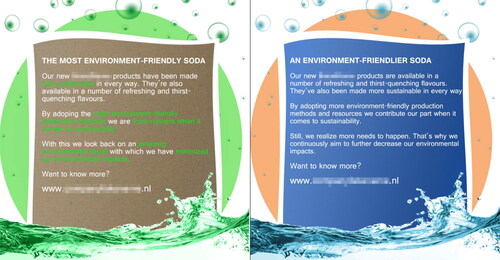

Stimuli and Procedure

The stimuli and procedure were similar to those in the first experiment. However, where in the first experiment it was merely stated that the company claimed the product was sustainable, participants now were assigned to one of three claim conditions. Participants in the claim-absent condition were not shown an ad. Participants in the other two conditions were shown either a puffery ad or a subdued ad. The manipulation of actual sustainability was operationalized through providing sustainability ratings, similar to Experiment 1. Thus, the degree of claim–fact discrepancy was determined by both the actual sustainability ratings and claim manipulation (in Experiment 1, the latter was kept constant). Instructions also stated that for the beverage category, on average, 50% of environmental impacts are caused by packaging and the other 50% by the product’s contents. This was added to rule out perceived environmental impact as an alternative explanation for the effects of centrality.

Ads (see Appendix C) were created based on a review of real-world campaigns and prior operationalizations (Darke and Ritchie Citation2007; Kopalle et al. Citation2017). Puffery and subdued ads were operationalized through both verbal and visual elements. This was done to provide a general view of ad puffery/modesty (rather than specific forms of puffery/modesty) and to ensure that the manipulation was sufficiently strong. Verbal elements (1) contained superlative adjectives in the puffery condition (e.g., “fully sustainable”) versus comparative adjectives in the subdued condition (e.g., “more sustainable”); (2) differed in order, such that they first mentioned sustainability information in the puffery condition, versus first flavor information in the subdued condition; and (3) contained a statement that the firm was “looking back on an amazing environmental result” for the puffery condition, versus a statement that “the firm realizes more work is to be done and that it is continually working on environmentally friendlier options” for the subdued condition (based on recent ads by Coca-Cola and Bar-le-Duc). Visual elements included (1) a green, “craft-paper” background color for the puffery condition versus a plain blue background for the subdued condition and (2) a bold green font to emphasize environmental claims for the puffery condition versus a regular white font for the subdued condition. We expected these visual elements in the puffery condition to strongly cue an environmental schema (Magnier and Schoormans Citation2015; Orth and Malkewitz Citation2008; Pancer, McShane, and Noseworthy Citation2017; Steenis et al. Citation2017).

The ad puffery was pretested among a sample of students (N = 56, Mage = 23.3; 79% female) following a two-group within-subjects design. To our knowledge no validated scale to measure puffery exists. Therefore, we used six 7-point semantic differential scale items (Humble/Exaggerated, Moderate/Ostentatious, Low-key/Puffery, Sincere/Pretentious, Cautious/Bold, Reserved/Excessive) intended to capture the degree to which the ads generated (exaggerated) expectations about the offering’s performance, based on similar items in prior research (e.g., Callister and Stern Citation2007) and in line with the definition of puffery. The scale was reliable, with Cronbach’s αs of .91 and .93 for the puffery and subdued ads, respectively. Repeated-measures ANOVAs showed that, indeed, the puffery ad scored higher on the scale than the subdued ad (Mpuffery = 5.21 versus Msubdued = 3.41; F (1, 55) = 108.78, p < .001, ηp2 = .66) . In addition, the ads should (on average) not significantly differ in the extent to which they emphasize either the packaging or product contents (7-point Likert scale items: “This ad gives me the impression that the packaging [product contents] are sustainable,” with anchors Fully agree/Fully disagree). As expected, participants, on average, considered the ads to equally emphasize packaging and product contents sustainability (Mpackaging = 4.80 versus Mproduct = 5.04; F (1, 55) = 1.97, p = .17).

Measures

In the conditions in which an ad was presented, participants gave their impression of the attractiveness of the ad (four 7-point Likert scale items: whether the ad was attractive, understandable, appealing, clear; α = .69). This allowed us to check that the two versions (puffery and subdued) did not differ in overall attractiveness. Measures for the main constructs were identical to Experiment 1 (see Appendix B for details). In addition, perceived puffery was included as a manipulation check, using the same items as in the pretest (not included in the claim-absent condition). Clearness of the actual sustainability ratings (two 7-point Likert scale items: “This rating is understandable,” “This rating is clear”; r = .41) was measured to check that these were understandable for participants.

Results

Attractiveness of the Ads and Clearness of the Claims

Both ads were seen as moderately attractive (M = 4.42), and attractiveness did not differ significantly between the puffery and subdued versions (F (1, 273) = 0.86, p = .365, ηp2 = .00). The sustainability ratings were generally seen as clear (M = 5.97), although there was a slight difference between the actual sustainability conditions (F (2, 406) = 3.02, p = .050, ηp2 = .02): The both-sustainable condition was seen as clearer (M = 6.10) than the packaging-sustainable-only condition (M = 5.83).

Manipulation Check for Puffery

To check whether puffery was successfully manipulated, a t test was carried out. It showed a significant effect of ad claim manipulations on perceived puffery (t (271) = 7.04, p < .001). The claim with puffery was, on average, perceived as more puffery than the subdued claim (Mpuffery = 4.99 versus Msubdued = 4.17).

Effects on Perceived Deception and Sustainability

ANOVAs were conducted to test the effects of claim puffery and actual sustainability on perceived deception and sustainability. Results showed medium to large significant effects of actual sustainability for both perceived deception (F (2, 400) = 72.24, p < .001, ηp2 = .27) and perceived sustainability (F (2, 400) = 131.05, p < .001, ηp2 = .40). The both-sustainable condition led to lower perceived deception as well as higher perceived sustainability compared to either partially sustainable condition, in line with hypothesis 1 (see for means). The two partially sustainable conditions did not significantly differ from each other. For perceived sustainability, this is in line with what was aimed for in the instructions. For perceived deception, the lack of significant differences between these conditions (Mpackaging-only = 4.76 versus Mcontents-only = 4.68, p = .55) suggested that there was no centrality effect. Thus, the centrality effect that we hypothesized (hypothesis 2) and found in Experiment 1 was not replicated in this experiment.

Table 2. Experiment 2: Means and standard deviations per condition.

Results also showed small to medium significant effects of claim type on both perceived deception (F (2, 400) = 7.95, p < .001, ηp2 = .04) and perceived sustainability (F (2, 400) = 17.50, p < .001, ηp2 = .08). Pairwise comparisons indicated that perceived deception was not significantly different under puffery and subdued claim. It was significantly lower when no claim was used, in line with hypothesis 4(a). For perceived sustainability, puffery and subdued claim were also not significantly different from each other. Perceived sustainability was significantly lower than either of these when no claim was used, in line with hypothesis 5(a). Interaction effects between claim type and actual sustainability were not significant.

Effects on Purchase Intentions and Attitudes

To test for the proposed moderated mediation—per hypotheses 4(b)/5(b)—we first investigated the effects of the mediators (perceived deception and sustainability) on purchase intentions and attitudes. Linear regression analyses with the two mediators as predictors showed significant negative effects of perceived deception on attitude toward the packaged product (b = −0.32, p < .001) and purchase intentions (b = −5.46, p < .001). Conversely, perceived sustainability had significant positive effects on attitude toward the product (b = 0.47, p < .001) and purchase intentions (b = 2.68, p < .01).

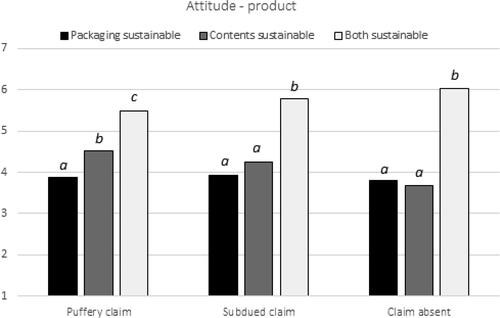

Two-way ANOVAs were conducted to test the effects of claim puffery and actual sustainability on purchase intentions and attitudes toward the packaged product. (Attitude toward the firm was also investigated; as in the first experiment, its results were generally similar to attitude toward the packaged product, hence we report only results of the latter unless results provide different insights.) Overall statistics showed medium to large significant main effects of actual sustainability on purchase intentions (F (2, 400) = 41.93, p < .001, ηp2 = .17) and attitude (F (2, 400) = 113.23, p < .001, ηp2 = .36). The both-sustainable condition led to significantly more positive outcomes than the packaging-only or contents-only condition (see ), and the pattern of means was similar for both dependent constructs. For claim puffery, the main effect on purchase intentions did not reach significance (F (2, 400) = 2.69, p = .069, ηp2 = .01), and the interaction effect between puffery and actual sustainability was not significant (F (2, 400) = 0.69, p = .598, ηp2 = .01).

While claim puffery did not have a significant main effect on attitude (F (2, 400) = 0.66, p = .518, ηp2 = .00), results showed a significant interaction effect between actual sustainability and claim type on attitude toward the packaged product (F (2, 400) = 4.52, p = .001, ηp2 = .04), supporting the idea that the effect of actual sustainability is moderated by claim puffery. To explore this effect further, we considered the simple effects of actual sustainability within each claim condition. Results () showed that in all claim conditions, as expected, attitudes were higher when both packaging and contents were sustainable than when either was not. Moreover, within the puffery condition, attitudes were higher when only the contents were sustainable than when only the packaging was sustainable (Mpackaging-only = 3.88, Mcontents-only = 4.51, p < .01), while in the other two claim conditions this difference was not significant (subdued: Mpackaging-only = 3.92, Mcontents-only = 4.25, p = .15; claim absent: Mpackaging-only = 3.81 versus Mcontents-only = 3.67; p = .56).

Figure 2. Interaction graph for attitudes. Superscripts a through c denote statistically significant differences between actual sustainability means per claim at the α = .05 level. Means that share the same superscript are not significantly different from one another.

We tested the differences in the effects of full versus partial actual sustainability on attitude toward the product across claim type conditions. Contrasts showed that the difference between the contents-only and both-sustainable conditions was significantly smaller in the puffery condition (Mdiff. = −.96) than in the subdued (Mdiff. = −1.52) and claim-absent (Mdiff. = −2.35) conditions (ps < .05). The difference in the subdued claim condition was in turn also significantly smaller than in the claim-absent condition (p < .05). For packaging-only versus both-sustainable conditions, the differences were of equal size under either puffery (Mdiff. = −1.59) or subdued claim (Mdiff. = −1.85) condition (p = .44) but were still significantly smaller than the difference in the claim-absent (Mdiff. = −2.21) condition (ps < .05). Taken together, the results for attitudes showed that the differences between the partially sustainable conditions and the fully sustainable condition were smaller under puffery, compared to absent claims.

Indirect Effects on Purchase Intentions and Attitudes

shows the estimates and bootstrap CIs (obtained via the SPSS PROCESS macro, Hayes and Preacher Citation2014; 10,000 bootstrap samples) for the indirect simple effects of actual sustainability at each claim level and pairwise comparisons between these indirect simple effects. At each claim level, the indirect effects of partial sustainability (either contents-only or packaging-only) in comparison to the both-sustainable condition, via perceived deception, were negative and statistically significant for both purchase intentions and attitude, providing support for hypothesis 3(a). The parallel, negative indirect effects via perceived sustainability were only statistically significant for attitude. There was no support for an indirect effect of one kind of partial actual sustainability versus the other. Overall, this provides only partial support for hypothesis 3(b).

Table 3. Experiment 2: Indirect effects of actual sustainability rating on attitudes and purchase intentions.

There was also evidence of indirect effects of claim type on attitudes and purchase intentions, as shown in . Indirect effects through perceived deception were indicated for both attitudes and purchase intentions. The presence of either puffery or a subdued claim decreased attitudes and purchase intentions due to higher perceived deception, compared to when no claim was present. Indirect effects of claim type through perceived sustainability were also significant for attitudes, but not for purchase intentions. The presence of either puffery or a subdued claim increased attitudes due to higher perceived sustainability, compared to when no claim was present.

Table 4. Indirect effects of claim type on attitudes and purchase intentions.

Regarding the moderation of the indirect effects via perceived deception, pairwise comparisons (see ) revealed that the indirect effects of packaging-only (versus both) sustainability on attitude and purchase intentions were more negative when the claim was puffery than when there was no claim. However, indirect effects of packaging-only (versus both) sustainability in the presence of a subdued claim did not significantly differ from those with puffery or no claim at all. Pairwise comparisons did not reveal moderation of the indirect effects of contents-only sustainability, though at α = .10 the indirect effects in the claim-absent condition did differ (i.e., were less negative) from those in the subdued claim and puffery conditions. Overall, we thus found support for hypothesis 4(b): for moderation of the effects of packaging-only versus both-sustainable (at α = .05) and more tentative for the effects of contents-only versus both-sustainable (at α = .10). We found these effects both for attitudes and purchase intentions.

Considering the indirect effects via perceived sustainability, pairwise comparisons revealed no moderation of the indirect effects of partial sustainability on purchase intentions, which is in line with the fact that these indirect effects were not significant. For attitudes, there was a difference in indirect effects of contents-only sustainability between the puffery and the claim-absent conditions. The indirect effects were less negative when puffery was used. Indirect effects of contents-only sustainability in the presence of a subdued claim did not significantly differ from those with puffery or no claim at all. Pairwise comparisons did not reveal moderation of the indirect effects of packaging-only sustainability on the two attitudes, though at α = .10 the indirect effects in the puffery condition did differ (i.e., were less negative) from those in the claim-absent conditions. Overall, we thus found partial support for hypothesis 5(b) when it comes to attitudes, but not when it comes to purchase intentions. We found moderation of the effects of product-only versus both-sustainable (at α = .05) and more tentative for the effects of packaging-only versus both-sustainable (at α = .10). In these cases the difference in the indirect effect via perceived sustainability between the full and the partial sustainability conditions was smaller when advertisement puffery was used.

Direct Effects

With respect to the direct effects (i.e., the parts of the effects of sustainability that are not mediated by perceived deception or sustainability), results showed significant direct effects of actual sustainability on purchase intentions and attitudes. Moreover, we found that the interaction effect between actual sustainability and claim type on attitude toward the product was significant (F (4, 409) = 4.66, p = .001), whereas the effect of this interaction for purchase intentions was not (F (4, 409) = 0.70, p = .59). Simple effects of actual sustainability were relatively strong when the claim was absent, and weaker for the subdued claim and puffery. We found two slight differences here in the pattern of results between attitudes toward the product and attitude toward the firm. For attitude toward the firm, the main effect of actual sustainability was not significant (F (2, 409) = 0.20, p =.82), while it was significant for attitude toward the product (F (2, 409) = 15.01, p < .001). Furthermore, although the interaction effect between claim type and actual sustainability was significant for both attitudes and patterns were the same, for attitude toward the firm, the effect of actual sustainability was only significant in the claim-absent condition. The general conclusion that perceived sustainability and perceived deception are partial mediators, and that the interaction between claim and actual sustainability remains significant after taking these into account, holds for both attitudes.

Discussion Experiment 2

Experiment 2 tested all hypotheses (1 through 5) and finds support for all but hypothesis 2, with partial support for hypotheses 3(b), 4(b), and 5(b). The experiment shows that, in line with Experiment 1, partial discrepancies between actual and claimed sustainability lead to lower attitudes and lower purchase intentions compared to fully sustainable product-packaging combinations. The type of claims that firms make about sustainability matter as well for the effect of partial discrepancy. Specifically, using puffery in sustainability claims generally increases the difference between the fully and partially sustainable conditions in terms of perceived deception. This means that partially sustainable packaged products are perceived as comparatively more deceptive when puffery is used, relative to when a firm does not make any sustainability claim. At the same time, the effect of puffery is not wholly negative, as it decreases the difference between the fully and partially sustainable conditions in terms of perceived sustainability. In other words, partially sustainable packaged products are perceived as being comparatively favorable on perceived sustainability when puffery is used.

Results also indicate evidence for perceived deception as a mediator for effects of claim–fact discrepancies on purchase intentions and attitudes (toward the product and toward the firm). Perceived sustainability, however, is only a mediator for attitudes and not for intentions, even though perceived sustainability affects purchase intentions positively. The remaining direct effect of actual sustainability on purchase intentions furthermore suggests that consumers may form other associations that positively influence their purchase intentions.

Contrary to Experiment 1, the current study does not confirm the centrality effect on perceived deception. A possible reason for the absence of a centrality effect on deception in the current study is the explicit mentioning in the instructions that both packaging and contents contribute equally to sustainability.

General Discussion

Theoretical Implications

The current research offers several contributions to the literature. First, we conceptualize the claim–fact discrepancy as a fundamental concept in the sustainability communication literature. This claim–fact discrepancy results from both “what is” (i.e., actual sustainability) and “what is communicated” (i.e., claimed sustainability). Our work further expands upon this claim–fact discrepancy by investigating what happens at varying degrees of discrepancy due to advertisement styles (i.e., puffery versus moderate versus no sustainability claim). We show that consumers are more likely to infer deceptive firm intentions when firms provide environmental claims for packaged products for which only one aspect—either packaging or product contents—is truly sustainable, compared to when both are sustainable. That is, the firm implies “full” sustainability but the actual offering is only partially sustainable. For such products, consumers make both positive and negative inferences such that they positively value the reduced environmental impact, yet at the same time negatively value the deceitful actions of the firm. Thus, even though the inclusion of a green attribute can itself exert a positive effect, feelings of deception cause consumers to penalize both the packaged product and firm because of how the offering is positioned. This negative impact dampens the positive impacts of sustainable attributes.

Following recent work in the marketing domain (Gershoff and Frels Citation2015), findings suggest that the impacts of actual environmental performance depend on the centrality of the attributes that are (or are not) sustainable. Making a peripheral attribute sustainable, and leaving a central attribute decisively less sustainable, tends to be perceived as a greater transgression than the opposite. This centrality effect was found in the first experiment but was not directly supported by the second experiment, although the pattern there does suggest that those combinations where only the peripheral attribute was made sustainable were evaluated more critically than those with a sustainable central attribute. While prior research has chiefly considered claim–fact discrepancies from a corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Wagner, Lutz, and Weitz Citation2009) and a marketing-communications perspective (Darke and Ritchie Citation2007), the current work implies that the nature of these discrepancies is more complex, because attributes can inherently differ in their centrality, even when perceived environmental impacts are similar.

The current work investigates the influence of claim puffery as a moderator for the effects of the claim–fact discrepancy. Previous research has shown that the presence and specificity of advertisements (general advertisement versus green advertisement or no advertisement) affects consumer response in the presence of objective sustainability performance ratings, such that consumer reactions become more negative when the ad becomes more specific (Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2014; Parguel, Benoît-Moreau, and Larceneux Citation2011). Our findings complement this prior research by showing that claim puffery also affects consumer response by moderating the effects of actual sustainability. When claims are more puffery, differences in actual sustainability matter less for consumers’ perceptions of sustainability, and they tend to form relatively positive impressions of sustainability based on the claim. Yet consumers also feel more deceived when puffery is confronted with partial (rather than full) sustainability of a packaged product.

Practical Implications

Firms that promote products with environmental attributes can best do so when the product’s environmental performance matches that claim. Specifically, when offerings are wholly sustainable, consumers respond most positively to general sustainability claims. Various sustainability-oriented firms make explicit sustainability claims and seek to match these claims with products that include sustainability in all (or as many as possible) product attributes. For example, in a recent campaign Arla, a European dairy producer, promoted its more environment-friendly packaging for its organic dairy products and explicitly stated, “Organic dairy deserves a more sustainable package.” On the other hand, promoting products which possess sustainability attributes but which also possess other less (or decisively not) sustainable attributes can lead to a backlash, because consumers may think that the firm is attempting to deceive them even though they do value the increased environment friendliness in itself. This may be particularly troublesome for products which have some degree of improved environment friendliness in one component but for which further improvements in other components could still be made.

The current article provides two main takeaways for marketing practice. First, when a product is only partially sustainable, firms should be realistic and cautious in setting expectations about that offering’s environmental performance. While consumers are conditioned to accept potential claim–fact discrepancies (to some extent) due to general advertising culture, the current work shows that, for an ethically loaded attribute such as environmental performance, perceived deception does exert a more negative effect on purchase intentions as the discrepancy increases. Second, using claims is a risk–reward trade-off, as it increases perceived deception yet also increases perceived sustainability. If consumers in a particular market are especially sensitive to (perceptions of) deception, puffery is likely to backfire. Conversely, if concerns of deception in the market or product in question play a smaller role in consumer purchases, the rewards of using puffery might outweigh the risk. The importance of sustainability benefits in the overall product purchase is another relevant consideration, such that taking higher risks (i.e., using puffery) is potentially more worthwhile for products in which sustainability benefits weigh heavily in choice.

Limitations and Future Research

The current research provided participants with ratings of the “true” environmental impacts of packaging and product contents. While similar real-world initiatives exist, assessing the environmental impacts of such products is often complex, and this information may not be readily available—especially not in a format that consumers can easily understand. In practice, consumers may rely on lay theories rather than detailed information to consider whether the producer is attempting to greenwash. In addition, although prior research has used similar paradigms (Kopalle et al. Citation2017; Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2014; Parguel, Benoît-Moreau, and Larceneux Citation2011), the presentation of explicit sustainability scores in combination with the firm’s claim also highlights the discrepancy in a way that is not necessarily common in real-world purchase contexts.

The experiments were also limited to the beverages category with a specific focus on packaging versus product contents. Future research could consider various other product categories. Some categories may be more closely associated with environmental damage than others, and consumers may be more skeptical toward inconsistent product offerings for categories associated with a high environmental burden (e.g., washing detergents, chemical household cleaners). Future research could also consider using a larger set of more central/peripheral attributes that can be made more sustainable to provide further evidence for the centrality hypothesis. With regard to the (mixed) centrality findings, we should note that Experiment 2 contained an explicit reference stating that the environmental impacts of packaging/product contents are equal (based on the distribution found in Experiment 1). Potentially, this explicit mention may have cued consumers to consider its believability, which could have affected the results with regard to the centrality distinction.

With respect to ad puffery, we operationalized it using multiple concurrent elements aligned with the concept of puffery (i.e., verbal elements such as superlatives, as well as graphical elements such as colors and visual emphasis). The reasons for this were to provide a general view of ad puffery and to improve the realism of the stimuli. A limitation of this approach is that it does not allow for the disentanglement of the separate effects of each manipulated element. Although we did not seek to investigate the relationships among each of these specific elements, future research might consider an investigation of specific means to convey puffery. This could be supported by the development of a validated scale to measure (various forms of) puffery, as to our knowledge no validated scales exist.

Conclusion

The current research investigated the joint effect of actual sustainability and claimed sustainability of packaged products on consumer responses. We theorized that for ethical attributes (such as sustainability attributes) perceived deception due to discrepancies between performance and claim might play an especially large role due to the credence nature of these attributes, as claims cannot easily be verified by consumers. We contribute to the existing literature by combining both variations in actual packaged product sustainability (varying a central and peripheral attribute) and variation between puffery, a subdued claim, and no claim. We conclude that even though consumers may value products with sustainability attributes, their response also depends on how these products are advertised.

Our results show that puffery about sustainability tends to increase sustainability perceptions yet also increase feelings of deception. Specifically, positive sentiments seem (at least partially) to be counteracted when there are (large) discrepancies between the advertisement claim and actual environmental performance. This implies that consumers may have difficulty reconciling puffery and low(er) actual environmental performance. The positive impact of puffery on product perceptions, in our case on sustainability perceptions, can explain the prevalence and (ostensible) success of puffery in practice, even for ethically loaded attributes, which are subject to a high degree of consumer skepticism. Yet practitioners should be aware that puffery increases perceived deception when consumers are aware that sustainability is only partly present, and they should be cautious about using puffery in that situation.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nigel D. Steenis

Nigel D. Steenis (PhD, Wageningen University) was a doctoral candidate at the time of this research, Marketing and Consumer Behavior Group, Wageningen University, and was also affiliated with Top Institute Food and Nutrition, Wageningen, the Netherlands.

Erica van Herpen

Erica van Herpen (PhD, Tilburg University) is an associate professor, Marketing and Consumer Behavior Group, Wageningen University.

Ivo A. van der Lans

Ivo A. van der Lans (PhD, Leiden University) is an assistant professor, Marketing and Consumer Behavior Group, Wageningen University.

Hans C. M. van Trijp

Hans C. M. van Trijp (PhD, Wageningen University) is a professor, Marketing and Consumer Behavior Group, Wageningen University, and is also affiliated with Top Institute Food and Nutrition, Wageningen, the Netherlands.

References

- Akturan, Ulun. 2018. “How Does Greenwashing Affect Green Branding Equity and Purchase Intention? An Empirical Research.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 36 (7):809–24. doi:10.1108/MIP-12-2017-0339

- Aji, Hendy M., and Bayu Sutikno. 2015. “The Extended Consequence of Greenwashing: Perceived Consumer Skepticism.” International Journal of Business and Information 10 (4):433.

- Atkinson, Lucy, and Sonny Rosenthal. 2014. “Signaling the Green Sell: The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer Trust.” Journal of Advertising 43 (1):33–45. doi:10.1080/00913367.2013.834803

- Callister, Mark A., and Lesa A. Stern. 2007. “The Role of Visual Hyperbole in Advertising Effectiveness.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 29 (2):1–14. doi:10.1080/10641734.2007.10505212

- Chakraborty, Archishman, and Rick Harbaugh. 2014. “Persuasive Puffery.” Marketing Science 33 (3):382–400. doi:10.1287/mksc.2013.0826

- Chang, Chingching. 2011. “Feeling Ambivalent about Going Green.” Journal of Advertising 40 (4):19–32. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367400402

- Chen, Yu-Shan, and Ching-Hsun Chang. 2013. “Greenwash and Green Trust: The Mediation Effects of Green Consumer Confusion and Green Perceived Risk.” Journal of Business Ethics 114 (3):489–500. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

- Cowley, Elizabeth. 2006. “Processing Exaggerated Advertising Claims.” Journal of Business Research 59 (6):728–34. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.12.004

- Crites, Stephen L., Jr., Leandre R. Fabrigar, and Richard E. Petty. 1994. “Measuring the Affective and Cognitive Properties of Attitudes: Conceptual and Methodological Issues.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20 (6):619–34. doi:10.1177/0146167294206001

- Darke, Peter R., and Robin J. B. Ritchie. 2007. “The Defensive Consumer: Advertising Deception, Defensive Processing, and Distrust.” Journal of Marketing Research 44 (1):114–27. doi:10.1509/jmkr.44.1.114

- De Vries, Gerdien, Bart W. Terwel, Naomi Ellemers, and Dancker D. L. Daamen. 2015. “Sustainability or Profitability? How Communicated Motives for Environmental Policy Affect Public Perceptions of Corporate Greenwashing.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22 (3):142–54. doi:10.1002/csr.1327

- Dodds, William B., Kent B. Monroe, and Dhruv Grewal. 1991. “Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers' Product Evaluations.” Journal of Marketing Research 28 (3):307–19. doi:10.2307/3172866

- Ellen, Pam S., Deborah J. Webb, and Lois A. Mohr. 2006. “Building Corporate Associations: Consumer Attributions for Corporate Social Responsible Programs.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34 (2):147–57. doi:10.1177/0092070305284976

- Ford, Gary T., Darlene B. Smith, and John L. Swasy. 1990. “Consumer Skepticism of Advertising Claims: Testing Hypotheses from Economics of Information.” Journal of Consumer Research 16 (4):433–41. doi:10.1086/209228

- Foreh, Mark R., and Sonya Grier. 2003. “When Is Honesty the Best Policy? The Effects of Stated Company Intent on Consumer Skepticism.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 13 (3):349–56. doi:10.1207/S15327663JCP1303_15

- Friestad, Marian, and Peter Wright. 1994. “The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (1):1–31. doi:10.1086/209380

- Gardner, David M. 1975. “Deception in Advertising: A Conceptual Approach.” Journal of Marketing 39 (1):40–6. doi:10.2307/1250801

- Gershoff, Andrew D., and Judy K. Frels. 2015. “What Makes It Green? The Role of Centrality of Green Attributes in Evaluations of the Greenness of Products.” Journal of Marketing 79 (1):97–110. doi:10.1509/jm.13.0303

- Goldberg, Marvin E., and Jon Hartwick. 1990. “The Effects of Advertiser Reputation and Extremity of Advertising Claim on Advertising Effectiveness.” Journal of Consumer Research 17 (2):172–9. doi:10.1086/208547

- Goh, See K., and M. S. Balaji. 2016. “Linking Green Skepticism to Green Purchase Behavior.” Journal of Cleaner Production 131:629–38. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.122

- Haan, Perry, and Cal Berkey. 2002. “A Study of the Believability of the Forms of Puffery.” Journal of Marketing Communications 8 (4):243–56. doi:10.1080/13527260210162282

- Hadjichristidis, Constantinos, Steven A. Sloman, Rosemary Stevenson, and David Over. 2004. “Attribute Centrality and Property Induction.” Cognitive Science 28 (1):45–74. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2801_2

- Hawcroft, Lucy J., and Taciano L. Milfont. 2010. “The Use (and Abuse) of the New Environmental Paradigm Scale over the Last 30 Years: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2):143–58. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.003

- Haws, Kelly L., Karen P. Winterich, and Rebecca W. Naylor. 2014. “Seeing the World through GREEN-Tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 24 (3):336–54. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2013.11.002

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Kristopher J. Preacher. 2014. “Statistical Mediation Analysis with a Multicategorical Independent Variable.” British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 67 (3):451–70. doi:10.1111/bmsp.12028

- Jain, Shailendra P., and Steven S. Posavac. 2001. “Prepurchase Attribute Verifiability, Source Credibility, and Persuasion.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 11 (3):169–80. doi:10.1207/S15327663JCP1103_03

- Kamins, Michael A., and Lawrence J. Marks. 1987. “Advertising Puffery: The Impact of Using Two-Sided Claims on Product Attitude and Purchase Intention.” Journal of Advertising 16 (4):6–15. doi:10.1080/00913367.1987.10673090

- Kelley, Harold H. 1973. “The Processes of Causal Attribution.” American Psychologist 28 (2):107–28. doi:10.1037/h0034225

- Kopalle, Praveen K., and Donald R. Lehmann. 2015. “The Truth Hurts: How Customers May Lose from Honest Advertising.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 32 (3):251–62. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2014.12.003

- Kopalle, Praveen K., Robert J. Fisher, Bharat L. Sud, and Kersi D. Antia. 2017. “The Effects on Advertised Quality Emphasis and Objective Quality on Sales.” Journal of Marketing 81 (2):114–26. doi:10.1509/jm.15.0353

- Kumkale, G. Tarcan, and Dolores Albarracín. 2004. “The Sleeper Effect in Persuasion: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Psychological Bulletin 130 (1):143–72. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.143

- Lee, Sang Y. 2014. “When Do Consumers Believe Puffery Claims? The Moderating Role of Brand Familiarity and Repetition.” Journal of Promotion Management 20 (2):219–39. doi:10.1080/10496491.2014.885481

- Magnier, Lise, and Jan Schoormans. 2015. “Consumer Reactions to Sustainable Packaging: The Interplay of Visual Appearance, Verbal Claim and Environmental Concern.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 44:53–62. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.09.005

- McQuarrie, Edward F., and David G. Mick. 1996. “Figures of Rhetoric in Advertising Language.” Journal of Consumer Research 22 (4):424–38. doi:10.1086/209459

- Meyers-Levy, Joan, and Alice M. Tybout. 1989. “Schema Congruity as a Basis for Product Evaluation.” Journal of Consumer Research 16 (1):39–54. doi:10.1086/209192

- Nyilasy, Gergely, Harsha Gangadharbatla, and Angela Paladino. 2014. “Perceived Greenwashing: The Interactive Effects of Green Advertising and Corporate Environmental Performance on Consumer Reactions.” Journal of Business Ethics 125 (4):693–707. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1944-3

- Obermiller, Carl, Eric R. Spangenberg, and Douglas L. MacLachlan. 2005. “Ad Skepticism: The Consequences of Disbelief.” Journal of Advertising 34 (3):7–17. doi:10.1080/00913367.2005.10639199

- Orth, Ulrich R., and Keven Malkewitz. 2008. “Holistic Package Design and Consumer Brand Impressions.” Journal of Marketing 72 (3):64–81. doi:10.1509/JMKG.72.3.064

- Pancer, Ethan, Lindsay McShane, and Theodore J. Noseworthy. 2017. “Isolated Environmental Cues and Product Efficacy Penalties: The Color Green and Eco-Labels.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (1):159–77. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2764-4

- Parguel, Béatrice, Florence Benoît-Moreau, and Fabrice Larceneux. 2011. “How Sustainability Ratings Might Deter 'Greenwashing': A Close Look at Ethical Corporate Communication.” Journal of Business Ethics 102 (1):15–28. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-0901-2

- Pratkanis, A. R., A. G. Greenwald, M. R. Leippe, and M. H. Baumgardner. 1988. “In Search of Reliable Persuasion Effects: III. The Sleeper Effect Is Dead: Long Live the Sleeper Effect.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54 (2):203–18.

- Richards, Jef I. 1990. “A "New and Improved" View of Puffery.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 9 (1):73–84. doi:10.1177/074391569000900106

- Skarmeas, Dionysis, and Constantinos N. Leonidou. 2013. “When Consumers Doubt, Watch out! The Role of CSR Skepticism.” Journal of Business Research 66 (10):1831–8. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.004

- Sloman, Steven A., Bradley C. Love, and Woo-Kyoung Ahn. 1998. “Attribute Centrality and Conceptual Coherence.” Cognitive Science 22 (2):189–228. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2202_2

- Steenis, Nigel D., Erica van Herpen, Ivo A. van der Lans, Tom N. Ligthart, and Hans C. M. van Trijp. 2017. “Consumer Response to Packaging Design: The Role of Packaging Materials and Visuals in Sustainability Perceptions and Product Evaluations.” Journal of Cleaner Production 162:286–98. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.036