Abstract

Many brand collaboration platforms—such as sponsorship, celebrity endorsement, influencer marketing, product placement, cobranding, and human branding—build strong relationships between brands and contribute to the brand equity of two or more brands. Brand equity, since inception, has been concerned with the value of a brand, how this value is built and measured, and how the marketplace responds to it. Based on previous work and in response to current marketing practices, the authors suggest that the concept of shared brand equity, where collaborative efforts result in connectivity between brands, is needed to better explain and guide advertising and marketing communications research and practice. Drawing on developments in cognitive psychology, we explain how shared brand equity is developed and how it persists, the role it plays in semantic/associative neighborhoods, and how it explains research findings. We offer a set of research propositions, as well as concrete examples of the usefulness of the theoretical approach.

The blazing Olympic torch, paraded through London yesterday for only the third time in the history of the games, is an unmistakable symbol of the world’s oldest sporting competition. But over the course of the past century, the Olympics have become subtly associated with another globally recognized icon: the red-and-white branding of the Coca-Cola Company. (The Independent, April 7, 2008)

As brands have devoted more of their communications budgets to collaborative platforms such as sponsorship, brand placement, endorsement, social media influencers (Donthu et al. Citation2022), and cobranding (Pinello, Picone, and Destri Citation2022), they have become more intertwined with other brands, just as the Coca-Cola brand is intertwined with the Olympic brand. Calls in advertising emphasize the need to “leverage secondary associations to build brand equity” by linking to people, places, and things (Keller Citation2020, p. 448). Observations in marketing reveal that branding now occurs in a hyperconnected world where traditional brand equity measures may not be relevant or sufficient (Swaminathan et al. Citation2020). These themes speak to the need for a construct that captures the brand equity shared between two or more brands.

Aaker (Citation1991) defines brand equity as “a set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and symbol, that add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or service to a firm and/or to that firm’s customers” (p. 15). Berry (Citation2000) describes brand equity as “the differential effect of brand awareness and meaning combined on customer response to the marketing of the brand” (p. 130). Brand equity has subsequently been defined and redefined (see ). In keeping with Aaker’s original definition, brand equity is viewed as an additive/subtractive phenomenon where the focal brand “aggregates” (Srivastava and Shocker Citation1991) or “adds value” (Farquhar Citation1989) through all it does.

Table 1. Selected definitions and measurement categories of brand equity.

Accumulated brand equity can then be accounted and is often measured as compared to an unbranded product. The second half of summarizes measures of brand equity. Ailawadi, Lehmann, and Neslin (Citation2003) identify three categories of brand equity measurement: customer mindset, product-market outcomes, and financial market outcomes. These categories are widely accepted in brand management research (see Mizik Citation2014), and measurement in each category captures the differential brand effect that accrues to brands with high equity. What was not envisioned when brand equity was originally defined and refined, primarily in the 1990s, was the evolving nature of marketing communications. Brand collaboration platforms go beyond the original bounds of brand equity to develop powerful connections between brands that must be accounted for if a clear strategic picture of the brand’s potential direction is to be plotted.

As we move toward an interrelatedness of stakeholders in business (Hillebrand, Driessen, and Koll Citation2015), our constructs must also match our interrelatedness. We argue that a construct, shared brand equity, has arisen through contemporary advertising and marketing practice. We define the construct here:

Shared brand equity is the extent to which semantic/associative knowledge between brands is linked, is widely represented in a linguistic community, and affects community member brand responses (e.g., expectations, predictions, decisions).

Theoretically, shared brand equity is a construct representing the network of associations in memory between two (or more) brands. Although a new construct, it can be observed in consistent patterns across brand collaboration platforms. Identification and recognition of shared brand equity challenges established siloed theorizing about a single brand’s equity when established through brand collaboration platforms. To extend thinking about brand equity to shared brand equity, we must understand how linkages are formed among the associative networks of brands and how these linkages influence responses to brands. We develop our thinking on the shared brand equity that influences the fates of brands with the following goals in mind:

Introduce a provoking theory (Sandberg and Alvesson Citation2021) of shared brand equity based on research in cognitive psychology, which responds to a call for improving brand awareness research in advertising (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022).

Demonstrate how shared brand equity, across a range of brand collaboration platforms, explains the influence of central constructs (e.g., individual brand equity, congruence) and addresses mixed findings in the literature.

Guide future research on shared brand equity from a memory perspective, with a process model, research propositions, and measurement alternatives.

Suggest, for managers, approaches to assessing the shared semantic/associative knowledge that is critical for marketing decisions.

It is acknowledged that the memory-based construct of shared brand equity will not address the full compendium of questions on the management of brands in partnerships. Thus, the work here could be labeled as “provoking theory” where the “purpose is to show alternative . . . disruptive ways of seeing phenomena” (Sandberg and Alvesson Citation2021, p. 504). Thus, in keeping with Sandberg and Alvesson, we suggest that not only could things be different than seen but they are already other than currently represented.

Definitions of the main brand collaboration platforms that build shared brand equity and estimates of financial investments in them are shown in , as is worldwide spending on advertising for comparison. The largest brand collaboration platform, in terms of worldwide investment, is sponsorship. Sponsorship spending estimates, as deals brokered for collaboration with a property rights holder, are outside traditional advertising measurements, but collateral spending surrounding partnerships is estimated to result in double the amount spent on sponsorship deals (Cornwell Citation2020). The activities of other collaborations, such as celebrity endorsements and influencer marketing, are largely captured in advertising estimates. The emphasis in is on a well-known set of brand collaboration platforms that are active, intentional, brand-to-brand relationship-building strategies. However, the concept applies broadly, for example, to an organization, between a human brand chief executive officer and a product brand; across categories, between a place brand and a product brand; or between a created avatar and a brand.

Table 2. Brand collaboration platform definitions and spending estimates.

Why the Construct of Shared Brand Equity Is Needed

To open discussion of the role of shared brand equity in brand collaborations, we must address two important characteristics of shared equity relationships that contrast with traditional advertising. First, unlike traditional, informational, or image-based advertising regarding a single brand, brand collaborations bring together brands and intentionally create links among them, thus building interdependence. Shared brand equity can reduce the control that either partner has in strategic brand decisions. For example, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, vodka brands, once touting their Russian heritage, have sought distance from the place brand of Russia; some even changed the product’s brand name—for example, Stolichnaya to Stoli (Lascelles Citation2022). The strategic decision on the part of some vodka brands to develop links with the place brand of Russia resulted in disruptive changes for brands in the category. The place brand of Russia did not simply subtract from the value of the Stolichnaya vodka but forced a crisis and immediate rebranding.

Second, brand advertising campaigns have an end point. While advertised brands persist and likely take forward many characteristics from past advertising, the advertising campaign no longer has a life of its own (save for historical records and YouTube videos). Once advertising ends, associations formed through advertising may be reactivated by the brand but are unlikely to be reactivated by the advertising because it is no longer encountered. In contrast, when brand collaborations end, both partners typically persist, as do aspects of their relationship. Shared brand equity can impact the performance that either partner realizes from strategic brand decisions. For example, in sponsorship of sports, research has shown that years (McAlister et al. Citation2012) or even decades (Edeling, Hattula, and Bornemann Citation2017) after a partnership has ended, previous sponsors are recalled when cued with the event. Interinfluence stemming from previous sponsoring partners impacts recall performance of the new sponsor for years. The residual shared brand equity from the original partnership can be viewed as an asset of the departing sponsor but is a detriment to the arriving sponsor in developing brand equity through partnering with the sport/event brand.

Given the differences between traditional advertising and brand collaboration approaches, alternative theorizing is needed to understand how brands brought together in a communications platform become different due to partnering. The current work is by no means the first to argue that other brands influence a focal brand’s potential. In 1998, Henderson, Iacobucci, and Calder argued that understanding brand networks is useful to brand managers and could be achieved with elicited associations, but that this understanding is rarely developed or used. In 2001, Lederer and Hill argued that it is insufficient to manage a brand as a stand-alone entity when clearly a brand’s connectivity to the brands of other companies influences customer brand perceptions. These arguments—that other brands matter—are even more important today given the expansion of brand collaborations and budgets devoted to them. What we have not had over the past two decades is a theoretical construct, namely, shared brand equity, and a framework that addresses its development.

Linked Knowledge: The Theoretical Underpinning of Shared Equity

With the conceptual arguments for shared brand equity introduced and grounded in the brand collaboration context, we briefly review the underpinnings of our theorizing. We begin with a discussion of three established recall paradigms of interest in examining shared brand equity. We then provide an updated perspective on associative networks through the discussion of four memory characteristics fundamental to recall for partners and their linkages. We then use this understanding of paradigms and memory characteristics to develop our process model and propositions.

Recall Paradigms of Interest

There are three major recall paradigms in the study of memory (i.e., cued recall, paired associate learning, and primed free association), and all are cue dependent. Humphreys and Chalmers (Citation2016) provide substantial support for the importance of cues in memory. The evidence reviewed by these authors includes a study by Smith and Moynan (Citation2008), which shows that participants who experienced a highly salient and provocative event (e.g., studying a list of swear words) could fail to remember the event unless an appropriate cue was provided. One way to appreciate the cue-dependent nature of memory is to imagine a college reunion. The usual experience is that many memories of relatively trivial events, not thought about in years, come flooding back in response to the cues provided by the situation. A corollary of a cue-dependent memory is that there will be many ways to cue a well-learned concept that has occurred in many different situations and is associated with many different concepts, as is the case in collaborative branding. We briefly review these major paradigms.

Cued Recall with an Extralist Associate Cue

In this paradigm in psychology (see Humphreys, Bain, and Pike Citation1989), participants study a list of unrelated words and are then cued with a word which is meaningfully or associatively related to a studied word but which was not on their list of studied words, thus termed an “extralist” cue. This corresponds closely to the situation where people are asked to recall a brand placed in media programming. This is an instance of deliberate recall, but the individuals probably cannot use a contextual cue that specifies where they learned the association between the program and the brand unless they viewed the program recently. They can, however, use other cues to home in on the brand in that program. One possibility is that they use the concept of a brand as a cue in addition to the program cue (Humphreys et al. Citation2010). For example, they might think that brands placed in programming are usually product brands, but this might make it harder to recall an organization, such as the U.S. Army, as a brand.

Paired Associate Learning

The second paradigm is where a related pair of words has been studied, and one member of the pair is provided as a cue (see Goss and Nodine Citation2014). This corresponds to the situation where someone who has just watched an influencer on YouTube is asked to recall a brand mentioned by the influencer. Here, it is likely that the event context is used as a cue, but it is not known whether the concept of a brand is also used. Indeed, there may well be a mixture of different cues used or different individual strategies used to support memory in learning paired associates (see Martinez and O’Rourke Citation2020).

Primed Free Association

The third paradigm is similar to cued recall with an extralist cue in that there is a study opportunity, but when the cue is presented in a study, the participant is instructed to produce the first word that comes to mind. In the instructions for the test, there is no mention of the preceding study opportunity. This is the type of task utilized to learn the brands most associated with the Tokyo Olympics, where study participants were given blank space and asked to write the brands that came to mind (Meyers Citation2021). This corresponds in daily life to encountering the brand or the event on its own and spontaneously being reminded of the pairing. In this task, there is presumably no cue other than the brand or event involved.

All three of these research paradigms are utilized in the study of brand collaborations. Free association is, however, the method of interest to examine shared brand equity and will be discussed subsequently. Free association can capture the strength of a relationship between two brands in memory; strength is, however, also a nuanced phenomenon (see Nelson, Dyrdal, and Goodmon Citation2005). Now we turn to measures in memory that underpin how shared brand equity might be understood and the four memory characteristics stemming from research.

Associative Networks Background

Advances in understanding human memory have been supported by the development of associative databases. Nelson, McEvoy, and Schreiber (Citation2004) used data collected from U.S. respondents to produce the University of South Florida Free Association Norms (USF-FAN) database. It has 5,019 stimulus words and has been cited thousands of times. The associative networks of words (nouns 76%, adjectives 13%, verbs 7%) were determined using a free-association task where individuals were shown a word and asked to produce the first word that came to mind that was meaningfully or associatively related. Responses were discarded when only one person gave a particular response, and the results were aggregated over approximately 150 participants. The associative strength between the cue and the target is then defined as the percentage of participants who produce the target given the cue.

The Small World of Words (SWOW-EN) database (De Deyne et al. Citation2019), now the largest database of word associations, has more than 12,000 cue words. Unlike the USF-FAN database, the SWOW-EN database allows participants to provide multiple responses to each cue. This work is ongoing and has been expanded to include languages other than English.

Development of these and other free-association databases has led to extensive research on memory. Nelson et al. (Citation2013) reviewed studies conducted utilizing word-association databases. In this review, they highlighted the importance of four memory characteristics derived from free-association findings: forward strength, backward strength, relative cue-to-distractor strength, and neighborhood density. These four characteristic measures account for a substantial proportion of the variance in the recall paradigms discussed and are briefly reviewed here.

Forward and Backward Strength

In memory, forward strength is defined as the probability that the cue elicits the target in free-association norms, and backward strength is defined as the probability that the target elicits the cue in those norms (Nelson et al. Citation2013). They are defined relative to a particular memory retrieval task. For example, if chair is used as a cue to recall table, the probability that chair elicits table in free association is the forward strength, and the probability that table elicits chair is the backward strength. If, however, table is being used to cue the retrieval of chair, the probability that table elicits chair in free association is the forward strength, and the probability that chair elicits table is the backward strength. Forward strength has a large positive effect on the probability of recall, and backward strength has a small positive effect.

As an example, brands in sponsoring often seek to build awareness of the brand as a sponsor. Financial services provider Visa is a long-term sponsor of the Olympics, and the words Visa and Olympics have been repeatedly paired in communications. Nonetheless, in recall tasks, Visa could still be expected to perform better in a forward strength test with Visa as the cue (e.g., “What events does Visa sponsor?”) than in a backward strength test with the Olympics as the cue (e.g., “What brands sponsor the Olympics?”).

Relative Cue-to-Distractor Strength

Relative cue-to-distractor strength is defined as the number of associates of the cue that do not elicit the target and are not elicited by the target divided by the total number of associates of the cue (Nelson et al. Citation2013). These distractors represent concepts or meanings that are unrelated to the target. Relative cue-to-distractor strength has a slightly negative effect on recall. Keeping with the example of Visa sponsoring the Olympics, Visa is also a long-term sponsor of the National Football League (NFL) and FIFA World Cup soccer. These sports brands are associates of the cue Visa that may distract from recall of the Olympics as a sponsored partner.

Neighborhood Density

Targets with more connectivity among their associates have been shown to be more likely recognized and recalled (Nelson et al. Citation1998). This phenomenon, termed neighborhood density, is defined as the number of links between a target’s associates (nonzero associative strengths) divided by the total number of possible links. It has a small positive effect on recall. It is related to relative cue-to-distractor strength, which, as noted, refers to the relationship between the cue and associates linked to the target and associates not linked to the target. In contrast, neighborhood density is purely a property of the target and its network. One can think of it as the coherency of the target concept. That is, it reflects the extent to which the different meanings or nuances of meaning of the target cohere or do not cohere.

Theoretically, the role neighborhood density plays is particularly important to marketing communications. In explaining how marketing and advertising work, the spreading activation theory (Collins and Loftus Citation1975) is often referenced. According to this theory, when the target is studied, activation travels in a stepwise fashion from the target out to associates and among them and then, following the network connections, returns back to the target. An alternative account of how recall works is the activation-at-a-distance theory, and evidence supports it (Nelson et al. Citation2013). Activation-at-a-distance theory argues that the target activates its representation and the associates in its network at the same time. In this theoretical account, the target is strengthened regardless of whether activation returns to the target.

As an example, Gatorade sports drink is a coherent target with a dense neighborhood of associations in sports developed through hundreds of sponsorships over several decades. When U.S. adults were given “blank space to write the brands that came to mind when they think of the Tokyo Olympics,” Gatorade came to mind for 2% of respondents (Meyers Citation2021). Gatorade was neither an event sponsor nor a U.S. team partner for the Tokyo Olympics. “Neighborhood density theoretically measures primed target strength, on the assumption that targets with higher neighborhood densities are primed to higher activation levels within the semantic network” (Nelson et al. Citation2013, p. 799; emphasis in original). Importantly, top Tokyo Olympic sponsors, including Airbnb, Alibaba Group, Allianz, Atos, Bridgestone, Intel, Omega, Panasonic, P&G, and Samsung, did not make the list of participants’ responses, but Visa and Toyota did come to mind. Neighborhood density and the activation-at-a-distance theory provide an understanding of these outcomes.

Shared Brand Equity Development in Brand Collaboration

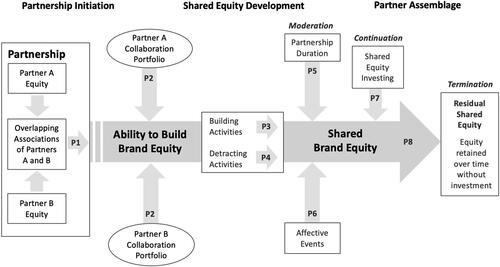

With a summary of recall paradigms and an understanding of the fundamental memory characteristics in mind, we now return to a discussion of shared brand equity. The process of developing shared brand equity in brand collaboration is depicted in as having three stages: partnership initiation, shared equity development, and partner assemblage. Briefly, two (or more) partners come into an agreement, bringing their current brand relationships, depicted as their respective portfolios, to the new partnership. The central box in considers how shared equity is developed via brand collaboration. Moderators of shared equity such as partnership length and positive and negative events are shown to influence shared equity outcomes as well as the potential of how shared brand equity might develop into the future (e.g., with a further contract or via termination of the relationship). guides the organization of this discussion and the presentation of theoretical assumptions and propositions.

Partnership Initiation

For an account of shared equity, one must take into consideration the equity brought to the relationship by each partner. Each partner enters a relationship with a network of associates and associations built up over time that are the essence of traditional discussions of brand equity. These links among associates support recall of the target in a memory task, and this connectivity (Nelson et al. Citation2013) contributes to neighborhood density. The starting point in brings together the potential partners. The extent to which a brand is already established in the linguistic community will determine the structure of associations on which shared brand equity may be built (presuming that there are not already established links between partners, to be addressed subsequently). In basic psychological research, better connected words have a greater ability to acquire new links, a phenomenon referred to as “the rich get richer” (Mak and Twitchell Citation2020).

Research on the importance of awareness in consumer decision making parallels findings in psychology. For example, a replication study of established findings on the role of awareness shows that people “choosing from a set of brands with marked awareness differentials showed an overwhelming preference for the high awareness brand despite quality and price differentials” (Macdonald and Sharp Citation2000, p. 5). Negative or positive starting-state brand associations are brand associations regardless of valence. It is self-evident that the starting equity of each partner should influence the potential of the pair and is thus a theoretical assumption.

Overlapping Associations

Across brand collaboration strategies, the role of congruence between partners has been and continues to be researched. Congruence, the relatedness or compatibility between partners, is a central construct in sponsorship (see Cornwell and Kwon Citation2020), celebrity endorsement (e.g., Lee, Chang, and Zhang Citation2022), influencer advertising (e.g., Kim and Kim Citation2021), product placement (see Russell Citation2019), cobranding (e.g., Nguyen, Romaniuk, et al. Citation2018), and human branding (e.g., Mogaji et al. Citation2022). When athletic shoemaker Adidas sponsors the Boston Marathon, there is a functional match (i.e., people use this product for this activity) between the brand and the event. Basically, any source of overlapping associations will influence shared equity. Each partner may independently hold an associate such as “winner” or “finish line” that the other partner holds. As well, there may be indirect facilitating links, or mediators that join the cue and target naturally (Nelson et al. Citation2013), such as ADIDAS-running-MARATHON. The value of congruence between partners stemming from overlapping associations has been positive in past research and profound in sponsoring. But as sponsoring has expanded, congruence has also been suggested as a source of confusion (see Cornwell Citation2020, p. 209). Past relationships by any member of a new collaboration may bring with it other brand associations, even direct competitor brands that may detract from the new relationship.

Proposition 1.

Starting state overlapping associations held by partners contribute to the ability to build shared equity but will detract from the focal collaboration if shared associations include noncollaboration brands.

Collaboration Portfolios

Because brand collaborations build strong associations and brand-to-brand links, the extent of a brand’s experience in collaborations is relevant. Collaboration portfolios of Partner A and Partner B are featured in . For example, in cobranding, a firm’s financial outcomes are affected by their own and their partners’ alliance experiences, and each brand’s collaboration experience is therefore included as a variable of interest in studying the effectiveness of cobranding (Cao and Yan Citation2017). A person, as brand, holds an endorsement portfolio (Kelting and Rice Citation2013), and the nature of the person’s brand portfolio influences each member brand’s communications potential. Similarly, brands in sponsoring hold a portfolio of properties, and properties have a roster of supporters.

Research on brand portfolio coherence (where subbrands share a common underlying logic of features) suggests that coherence improves consumer response to brands (Nguyen, Zhang, et al. Citation2018). Applying this finding to shared brand equity, coherent connectivity of partners’ collaboration portfolios should set the potential for a new relationship. Current relationships within collaboration portfolios would be expected to have the most profound influence on the development of shared brand equity, but the role of past relationships cannot be excluded. This corresponds to the introduced activation-at-a-distance theorizing, where the target in a recall task activates the representation of the target and all the associates that comprise its network in parallel (Nelson et al. Citation2013), which supports recall.

Proposition 2.

The extent to which the partners’ collaboration portfolios have coherent connectivity within their respective portfolios contributes to their ability to develop shared brand equity.

Shared Equity Development

Naturally, investments in advertising and communications can support the development of shared brand equity and will be discussed. Although the relationship between spending and communication success cannot be viewed as a given, the more theoretically interesting question is how to invest. We first consider investments in individual and shared activities and discuss their roles in building shared brand equity. We also discuss the detracting roles of similarity and active interference in building shared brand equity.

Building Activities

New learning capitalizes on old learning (e.g., Mak and Twitchell Citation2020; Tehan Citation2010). In short, associations held by each partner, such as those developed in advertising, become potential shared brand associates that are the basis of shared brand equity. Based on both memory and advertising research, it is highly likely that repetition, frequency of exposure (Schmidt and Eisend Citation2015), variation in communications (Janiszewski, Noel, and Sawyer Citation2003), and spacing (i.e., the interval between one ad and the next; Janiszewski, Noel, and Sawyer Citation2003) strengthen each partner and potential associations between partner networks. Importantly, individual activities that build associations for one partner (without association to the other partner) hold the potential to increase recall through neighborhood density.

From associative accounts of word learning, we know that new linkages are built between words and concepts by experience in context. As an innovative example, Sloutsky et al. (Citation2017) studied young children and adults and examined how syntagmatic associations (i.e., links between words that co-occur in close temporal proximity: “furry cat”) and paradigmatic associations (i.e., links between words that belong to the same grammatical class: “cat and dog”) are formed. The researchers agree that some learning occurs when a child points to an object, and the adult names that object. They argue, however, that this cannot account for the bulk of word learning, as it does not account for the learning of abstract words, such as love, or of entities that cannot be seen, such as air. Instead, they argue that most word learning must come from the context in which words occur. Overall, semantic memory is viewed as a fluid and flexible system that is sensitive to context, situational demands, as well as perceptual and sensory information coming from the environment (Kumar Citation2021)

Importantly, in brand collaborations, individuals establish associative strength from implicit learning in contexts that surround brands. This implicit learning could take place when activities surrounding a partnership bring a product brand and a branded activity together (Simmons and Becker-Olsen Citation2006) or when brands engage in thematically tied advertising where partner brands are represented in an ad (Kelly et al. Citation2012). Joint activities, where the brands are communicated together, hold the potential to build forward and backward strength as well as neighborhood density, and the aforementioned coherent connectivity. That said, starting brand equity may result in lopsided outcomes in brand collaborations. Cobranding research finds that brand evaluations for well-known brands and less-known brands depend on when cobranding information is presented (Cunha, Forehand, and Angle Citation2015). Similarly, well-known celebrities can overshadow brand partners and reduce recall for the product (Erfgen, Zenker, and Sattler Citation2015). In sponsorship, high-equity brands are perceived as more congruent sponsors than low-equity brands in the same brand category (Roy and Cornwell Citation2003). These findings are likely due to the extensive associative networks large brands have that hold many points of connection for partner event brands. In another example of size dominance, research on human brands in the context of fashion houses and designers finds that there is a dilution of an individual designer’s professional brand resulting from entangled associations between the designer and the house (Parmentier and Fischer Citation2021).

Proposition 3.

Contributions of individual and joint activities to shared brand equity depend on starting partner equity, and thus neighborhood density, with small equity brands less able to build shared brand equity through activities than large equity brands.

Detracting Activities

In building shared brand equity, it is also important to understand what may be detracting (see ). Advertising repetition has been shown to be most successful when there is little or no advertising for similar products in the context (Burke and Srull Citation1988). Similar competing brands are confused in memory tasks.

In sponsorship, support for this conjecture comes from demonstrations that after studying a paragraph announcing a sponsorship arrangement between a well-known brand and a fictitious event, people sometimes substitute a direct competitor for the actual sponsor (Humphreys et al. Citation2010). Weeks, Humphreys, and Cornwell (Citation2018) expanded on these findings by taking into consideration the difference between item and relational information (Einstein and Hunt Citation1980; Humphreys Citation1976). Item information is information that differentiates between items (e.g., brands), while relational information is information that links two or more items. They reasoned that provision of relational information for a congruent relationship would increase the probability of recalling the event, given the competitor as a cue because this relational information would often apply to a competitor as well as to the sponsor. In Experiment 2 of their work, following exposure to press releases, participants were told to use the brand to recall the event. Unbeknownst to the participants, some of the cues were competitors of the named sponsor. Under these circumstances, having provided relational information about the sponsor-event partnership increased recall of the event, given the competitor as a cue. However, having provided item information differentiating the sponsor and its competitor protected against these errors.

Brands that are competitors have many similarities, causing confusion errors in recognition and allowing a competitor to substitute for the focal brand. Further, brand collaborations can develop bindings that may cause confusion across categories. For example, following a five-year cobranding relationship between equipment manufacturer Peloton and athletic apparel Lululemon Athletica, the two partners became embroiled in lawsuits. The legal actions began when Peloton launched a line of their own fitness apparel. Lululemon argued that selling Peloton products through the same retail outlets as were used to sell the cobranded Lululemon products may be misleading (Ping Citation2021). Here Lululemon as a strong associate of Peloton (because of cobranding) might come to mind and be thought of as the fitness apparel provider. This is in keeping with research that shows forward and backward associative strength can indicate the extent to which similarity causes confusion or false memories (Arndt Citation2015).

Across collaboration platforms, similarity and interference can be seen as detracting from shared brand equity. In cobranding, research finds that advertising using brands from two categories has a negative effect on brand memorability and that the advertisement’s category context, when congruent, supports brand recall (Nguyen, Romaniuk, et al. Citation2018). In human branding endorsement portfolios, brands with a high or low match with the celebrity are more accurately recalled than brands having a moderate match with the celebrity (Kelting and Rice Citation2013). The researchers argue that the associative strength of high- and low-matching brands influences recall through extremity of the link. Coherence of high-match brands and the inconsistency of low-match brands drive attention and thus recall. In brand placement, active interference from a nonpartner brand has also been identified. In the context of an advertiser-funded program, where programming is built around a brand, program liking positively impacts viewer attitude toward the main competitor of the brand funding the program (Verhellen et al. Citation2016). The researchers found the strong fit between the program and the funder guarded somewhat against this confusion. The role of interference from multiple brands in product placement has been argued as important for future research (Russell Citation2019).

In sponsoring, active interference often comes from nonpartner brands. Ambush marketing is a form of associative marketing where a nonsponsoring brand seeks to capitalize on awareness and attention by associating with an event or activity (Chadwick and Burton Citation2011). Ambushing tends to have adverse effects on recall and recognition (Kelly, Cornwell, and Singh Citation2019), but counterintuitively, some associations that would seem interfering can support memory. Cornwell et al. (Citation2012) had participants read simulated press releases announcing a known brand sponsoring a fictitious event. In half the press releases, a competitor was also mentioned as having lost in a competition to be the sponsor. The surprising finding from this study was that the mention of the competitor in the press release increased the recall of the sponsor. The explanation put forward by the authors was that one might think at encoding or retrieval, “Ah, this one is [a competitor or] an ambusher,” and this might support memory of the true sponsor.

To summarize, much, if not most, forgetting is due to associative interference. The traditional idea is when a single cue is associated with two or more targets, referred to as cue overload (Watkins and Watkins Citation1976), memory errors are likely. Work conducted in various paradigms finds that interference does not overwrite remembered information but can limit access to it (see Cohn and Moscovitch Citation2007; Dyne et al. Citation1990; Verde Citation2010); thus, cues utilized to retrieve established information must be clarifying.

Proposition 4.

Similarity to and active interference from partner or nonpartner brands reduces shared brand equity when cue overload results in confusion but supports shared equity when nonpartner brands cue context, novelty, or clarifying information at encoding or retrieval.

Moderation

Several moderating variables may influence the strength or direction of shared equity development. Many moderators could be imagined. We will consider examples of moderators argued to play supporting and detracting roles in shared brand equity development.

Length of Partnership

Just like in long-running, consistent advertising campaigns (e.g., Braun-LaTour and LaTour Citation2004), long-term relationships in collaborative branding support memory (e.g., Walraven, Bijmolt, and Koning Citation2014). Straightforwardly, the longer the partnership, the greater the strength of the forward and backward associations, assuming almost any reasonable attempt to link the two brands. Moreover, long-term common usage in the linguistic community will result in representations with a high degree of consensus in meaning. When a partnership ends, the persistence of shared equity will be directly related to the duration of the partnership (see McAlister et al. Citation2012).

Proposition 5.

The longer the partnership, the more forward and backward cueing is strengthened, and the more consensus of meaning is established in the linguistic community; thus, the greater the developed shared equity and the greater the extent and duration of residual equity if the relationship is terminated.

Affect in Shared Brand Equity

Affect has been conceived of as an “umbrella for a set of more specific mental processes including emotions, moods, and (possibly) attitudes” (Bagozzi, Gopinath, and Nyer Citation1999, p. 184). Past theorizing regarding consumer-based brand equity finds favorability of brand associations is important in building positive consumer-based brand equity (Keller Citation1993, p. 5). On the other hand, negative affect produces unfavorable brand associations and is detrimental to attitudes (Chaudhuri and Holbrook Citation2001). Limited research in sponsorship suggests that repeated visual images with negative (e.g., skiing accident) or positive (e.g., winners’ circle) valence in sports do influence the attitudinal response to sponsors in keeping with the valence of the images (Cornwell, Lipp, and Purkis Citation2016). From research in psychology, we know that affect supports recognition because affective events are more richly experienced in memory (Ochsner Citation2000). We also know that emotions can support memory for information that is thought to be central to an event through attentiveness and impair memory for peripheral information (Levine and Edelstein Citation2009). Further, both positive and negative emotional stimuli have the potential to influence memory for details (Chipchase and Chapman Citation2013).

In psychology, early work by Schachter and Singer (Citation1962) argued that the compendium of physiological, semantic, and perceptual experience comes together as an emotional state. With repetition, details of these experiences drop out or become attenuated, with what remains being an emotional category of something we know, such as fear, excitement, or joy (see Barrett, Lindquist, and Gendron Citation2007; Lindquist, Satpute, and Gendron Citation2015). This role of emotion in the context of shared equity could be illustrated with celebrity endorser Naomi Osaka and the emotion of admiration. When the tennis player withdrew from the French Open event in 2021, citing her own mental health and well-being (Gregory Citation2021), individuals watching the event or reading about her actions may have had varied experiences of admiration. As brand partners articulated admiration and understanding of her actions, the potential for an associative link was built. Admiration, as an associate of the player Osaka and of her brand partners, helps support memory for each partner and their relationship.

There are, however, challenges in incorporating affect into a measurement model of shared brand equity. Negative events increase the potential to cement in memory the forward and backward strength between two brands because they draw attention to the relationship and likely come with repeated reinforcing exposures to the brand pairing. Negative valence of an event may detract from the positive influence of the event in the near term, but over time it may simply become associative as the gist of a relationship is retained but not the valence.

In short, at least three aspects of affect must be considered important in shared equity. First, affect, in the main, supports memory through attentiveness. Second, repeated affective experiences and messaging can result in emotional categories (e.g., admiration) that might serve as linking concepts in recall and recognition. Finally, affective links influence attitudes in keeping with their valence, but both positive and negative affective events influence memory positively over time.

Proposition 6.

Positive events increase shared equity in terms of attitude and memory, whereas negative events reduce shared equity in terms of attitude in the short term but support shared equity over time through increased forward and backward associative strength irrespective of valence.

Partner Assemblage

Shared Equity Investing

Advertising research has, for the most part, been concerned with short-term to medium-term response to largely one-way communications. Shared brand equity is important over an extended time horizon. Influencer marketing in social media may be measured in weeks, but advertising campaigns featuring celebrity endorsers or utilizing brand placement are typically two or three years in length. Contrast this to six- or 10-year team sponsorships or 30-year stadium sponsorships. In the main, advertising research is understandably oriented to relatively short-term measures of effectiveness, but long-term perspectives are informative. For example, Hansen, Kupfer, and Hennig-Thurau (Citation2018) studied social media firestorms and found significant long-term effects for brands. Their research built a two-year database that discovered data points where the term “shitstorm” was combined with a brand name. Their findings showed that 40% of brands face long-term negative consequences from the firestorm (p. 566).

With the need for long-term measurement in mind, we need to look to research in other areas to inform expectations of long-term relationships. Bahrick (Citation1984) studied retention of Spanish learned in school as long as 50 years ago. Testing showed that large portions of originally acquired information are available (even without practice or use) after 50 years. Bahrick argued that the transition of information into a “permastore” state occurs during the extended period of original training. This finding hints at an important process for shared brand equity: The transition from memories of individual episodes to a network of long-term associations in semantic memory. There is considerable interest in the process by which episodic memories become semantic memories (Kumar Citation2021). Brands that extend their relationships build equity over time and may specifically increase their backward strength from the program, person, or event to the brand as they crowd out less-involved brands in the context.

Proposition 7.

Continuation of a partnership with varied investments into the future enhances shared equity and, in particular, backward associative strength from various touchpoints in the collaboration.

Residual Shared Equity

Advertising associations acquired by a brand are known to have carryover effects that extend beyond the active advertising period (Lodish et al. Citation1995). In discussing the celebrity capital life cycle, Carrillat and Ilicic (Citation2019) suggest that brands with strong relationships in the past might stage a resurgence plan. The authors offer the example of child star Neil Patrick Harris and his leading role in the 1990s TV series Doogie Howser, M.D., which were years later utilized in a series of ads for the personal care brand Old Spice. The comical advertising referenced the actor’s fictional role as a child medical doctor in the Old Spice ads. In terms of shared brand equity, the original partners, Harris and the Doogie Howser, M.D. program, were paired with a third brand, Old Spice, to activate and utilize residual shared brand equity.

In sponsorship, the persistence of shared brand equity has also been demonstrated. McAlister et al. (Citation2012) utilized a classic paradigm from psychology to study how a sponsorship relationship that has ended, even when the sponsored property has gone on to form a relationship with a new sponsor, persists in memory. The researchers argued that an old sponsor would be spontaneously recovered from memory (see Brown Citation1976; Wheeler Citation1995) because contexts that shift over time are utilized in making recall and recognition decisions (Dennis and Humphreys Citation2001). The new sponsor may lose its retrieval advantage over the old sponsor when the context of the new sponsorship is less available as a cue.

McAlister et al. (Citation2012) studied four sponsoring contexts where a former sponsorship relationship had ended and a new relationship had begun. For each sponsorship, two independent samples six months apart were asked to recall (not recognize) the current major sponsor and subsequently to recall the previous major sponsor. Importantly for each sponsorship relationship, the data were collected around the time of the event, and the prior sponsor held a long-term relationship. Summing across the four events, at the time of the event the new sponsor was correctly recalled as the current sponsor 35% of the time, whereas the prior sponsor was incorrectly recalled approximately 17% of the time. In contrast, after a six-month delay and away from the time that the new sponsor and its associations were being activated by the event, 20% of the new replacement sponsors were recalled, whereas 42% of the replaced old sponsors were recalled. In some instances, the new sponsor had replaced the prior sponsor for more than a decade, but the prior sponsor was still remembered.

Similar supporting evidence of the persistence of sponsorship-based associations comes from Edeling, Hattula, and Bornemann (Citation2017) and their study of 33 German soccer sponsorship relationships. These authors find that the duration of an original sponsorship relationship influences correct recall decades later. This is consistent with the theorizing of Nelson et al. (Citation2013) in that the quality of the initial encoding was likely supported by a long-term relationship. Their hypothesized relationship between recall of a past sponsor and the number of subsequent sponsorships with “other congruent objects” reduced recall for the focal past sponsor. While this is interpreted as interference-based forgetting and an overwriting of stored information, the results are also consistent with the logic of a crowded neighborhood and a failure of access (Tulving and Pearlstone Citation1966). This logic then suggests that information regarding the focal sponsor is there, available, and not overwritten but less accessible due to subsequent sponsor relationships.

Proposition 8.

The strength and duration of residual shared equity, without continued investment, depends on the length of the original relationship, the extent of joint marketing communications, and the nature of subsequent relationships held by the partners.

Measurement

Measurement in Brand Collaboration

For any construct, measurement is essential. Measuring the effects of brand collaborations in specific areas has a long tradition and is an active stream of research. Research finds that tourists increase their search behavior and intent to visit a location when exposed to joint brand advertising rather than single brand advertising. (Can et al. Citation2020). In terms of memory, cobranded advertising has been shown to have a negative effect on brand memorability due to interference (Nguyen, Romaniuk, et al. Citation2018). Using secondary data, Yang, Shi, and Goldfarb (Citation2009) estimated the value of brand alliances between athlete brands and sports team brands in basketball and found that the highest value for the collaboration comes between top players and medium brand equity teams. These examples highlight the interest in measuring the outcomes of shared brand equity, but not the construct of shared brand equity.

Measuring Shared Brand Equity

Studies of semantic memory in cognitive science utilize three models: (1) associative-network models using various semantic network databases, including free-association norms that orient to the association between words; (2) feature-based models where databases develop feature norms based on binary features (e.g., birds have wings; cars do not); and (3) distributional semantic models built by extracting regularities from a corpus of natural language and inferring associations between words and concepts (Kumar Citation2021). The first of these approaches, based on elicited human free associations, and the last, based on inferred associations from the corpus of text, are discussed as useful in the study of shared brand equity. Feature-based models are not discussed further due to the lack of a systematic way to measure features (see Kumar Citation2021).

Solicited Free-Association Norms

Use of associative strength as a measure of shared brand equity would require adjustments to the procedures previously utilized in psychology. Unlike in psychology, where words are normed for associates with broad human knowledge networks in mind, participants in advertising and marketing would need to be oriented toward the context of interest (e.g., sports, arts, entertainment). Orienting instructions might be supplied or, if data were collected in a relevant context, contextual cues might provide adequate orienting. Then the simple task asks approximately 150 participants to respond to each cue with the first word that comes to mind. The conditional probability of a response given a cue is the forward associative strength (FAS) that binds the cue and response. Similarly, backward associative strength (BAS) can be assessed following the assessment of FAS. For example, Arndt (Citation2015, p. 1099) uses the word task to exemplify associative strength: The most frequent response is job (FAS = .370); the second, third, and fourth associates are chore (FAS = .145), duty (FAS = .055), and force (FAS = .032). The FASs sum to less than 1, and idiosyncratic responses and failures to respond account for the remainder. The BAS is, for example, the ability of duty as a cue to produce task (BAS = .027)

If one wanted to know how effective Brand A would be as a cue for Brand B (and vice versa), one would start with collecting the associates of Brands A and B. Then one would have to collect the associates of all their associates, though the total number of associates is unlikely to be large (e.g., less than 30 as seen in word norms) because every participant produces only a single associate to each cue, and there is likely to be substantial agreement in the associates produced across participants. What is produced for the free-association test will depend on the context, which will include the other items tested. Collecting data directly from humans experiencing brands in context offers free association, norming the advantage of grounding the approach in actual human perceptions (Harnad Citation1990). We will return to this topic when discussing inferred associations from text.

How can a shared brand equity measure inform research and practice? As an example, consider the “vampire effect” (Erfgen, Zenker, and Sattler Citation2015), where a celebrity endorser overshadows the brand partner because “a well-known celebrity might activate certain associations in consumers’ memories, whereas an unknown endorser cannot, because he or she invokes no cognitive schema” (p. 156). A celebrity endorser is typically employed to elevate awareness of a brand and to associate the characteristics of the celebrity brand with the product brand. This process could be monitored by considering their shared brand equity over time. If forward associative strength from the endorser brand to the product brand develops over time, but backward associative strength from the product brand to the endorser brand does not rise, it suggests that activation of the celebrity brand primes recall of the product brand, but activation of the product brand does not prime recall of the celebrity. Characteristics (e.g., associations such as “cool”) of the celebrity brand may not be developing as shared associations of the product brand.

Inferred Associations from Text

Another measurement approach that may be useful in studying shared brand equity is text analysis. Text corpora (e.g., books, newspapers, online articles) are thought to be a good proxy for the language people experience in their lives (Kumar Citation2021). Developments in computational semantic networks—extracted from text corpora—have been used to investigate both the structure of semantic memory and retrieval processes (Kumar, Steyvers, and Balota Citation2022). The use of secondary data from downloadable text sources holds appeal in the study of shared brand equity due to their variety and availability (e.g., news, advertisements, scrapped social media posts). Text sources, even though written by humans, have the disadvantage of being distant from perceptual experiences. This shortcoming in grounding symbols to human experience (Harnad Citation1990) is being addressed in part with multimodal distributional semantic networks. For example, Bruni, Tran, and Baroni (Citation2014) have developed computer vision techniques that can produce “visual words” to identify patterns in images, thus allowing the distributional representation of a word in a text corpus to be matched with co-occurrence of images associated with words (p. 1). This development is particularly relevant to the measurement of shared brand equity.

Discussion and Future Directions

Research, as well as industry practice, needs a strong theoretical understanding of shared brand equity in terms of development, effects, and long-term persistence. Stemming from work in marketing on brand equity, work in psychology on memory, and work developing free-association norms, the current work builds a theory of shared brand equity and makes it concrete through application to the contexts of brand collaboration. Contributions toward the four goals declared at the onset—namely, introduction to shared brand equity theory, demonstration of its explanatory capacity, provision of a process model and propositions, and suggestions for managers—are summarized in the following sections.

Theory Contribution

In their call for advertising research on awareness as a construct, Bergkvist and Taylor (Citation2022) review publications in the Journal of Advertising, International Journal of Advertising, and Journal of Advertising Research for articles that include the terms awareness, recall, or recognition. Of the 337 articles having included one of the three search terms, only 136 include some measure of brand awareness. These 136 publications represent 5.2% of the total articles retrieved (p. 7). Given the underlying importance of awareness to advertising and marketing communications, the authors argue that there needs to be a reinvestment in this space.

The introduction of this provoking theory of shared brand equity, which accounts for findings from a range of brand collaboration platforms, calls into question long-standing assumptions about how brands build equity, and lays the groundwork for future research, is long overdue. In 2003, Nelson, McEvoy, and Pointer published an article titled “Spreading Activation or Spooky Action at a Distance.” In this work, they admitted to their own surprise that the resonance to preexisting links (a concept central to spreading activation theory) was not necessary to improve recall. They at first believed the findings must be a fluke. Referring to their earlier work (Nelson et al. Citation1998), the authors “found it difficult to believe that associative links could affect memory for the target in the absence of links coming back to it” (Nelson, McEvoy, and Pointer Citation2003, 49). Their subsequent work solidified this finding (Nelson et al. Citation2013). As a field, we have been slow to integrate new findings from psychology into our understanding of how advertising and marketing communications work. The construct of shared brand equity is consequential in understanding recall results in brand collaboration platforms. Theorizing regarding shared brand equity can account for past findings, in part through theoretical contributions such as activation-at-a-distance theory (Nelson et al. Citation2013), and the propositions introduced can guide future research.

Managerial Value

Understanding the starting points, development, and long-term outcomes of shared brand equity is important for brand managers engaging in brand collaboration platforms. From the developed process model, clearly starting brand equity is critical in developing shared brand equity, and the advantages and disadvantages of being a large or small brand are largely understood. Strategies are perhaps not informed, however, regarding the challenge of lopsided associative strength. Fortunately, brands could monitor the development of backward associative strength on a regular basis through free-association norms.

One of the least recognized aspects of shared brand equity is best illustrated with the evidence that terminated sponsorship relationships still influence recall for new and old sponsors years later (Edeling, Hattula, and Bornemann Citation2017; McAlister et al. Citation2012). Any brand beginning a partnership should assess the shared brand equity developed through past relationships that will influence their communications into the future. Similarly, brand managers may be unaware of the long-term impact of negative events or social media firestorms caused by a past or current partner, but keywords arising in free associations or from text analysis could gauge any continued unwanted associations.

The theoretical construct of shared brand equity is needed in research and practice to better model the phenomenon of influential associative links developed via popular marketing communication platforms. To ignore shared brand equity is to avoid eye contact with phenomena that influence research designs, marketing activities, and human behavior. To fully account for shared brand equity is a monumental task. The memory-based provoking theory provided here is a starting point.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to Professor Michael S. Humphreys, a theoretical memory researcher who valued learning from and working in applied fields. Thank you to Noelle Nelson for comments on an early draft of this work, Jenny Burt for comments on the penultimate version, and to the Journal of Advertising review team for their thoughtful comments on this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

T. Bettina Cornwell

T. Bettina Cornwell (PhD, University of Texas) is a professor, Lundquist College of Business, University of Oregon.

Michael S. Humphreys

Michael S. Humphreys (PhD, Sandford University) is a professor, School of Psychology, University of Queensland.

Youngbum Kwon

Youngbum Kwon (PhD, University of Michigan) is an assistant professor, College of Human Ecology, Pusan National University.

References

- Aaker, D. A. 1991. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Ailawadi, K. L., D. R. Lehmann, and S. A. Neslin. 2003. “Revenue Premium as an Outcome Measure of Brand Equity.” Journal of Marketing 67 (4):1–17. doi:10.1509/jmkg.67.4.1.18688

- Anderson, J. R., and G. H. Bower. 2014. Human Associative Memory. New York: Psychology Press.

- Arndt, J. 2015. “The Influence of Forward and Backward Associative Strength on False Memories for Encoding Context.” Memory (Hove, England) 23 (7):1093–111. doi:10.1080/09658211.2014.959527

- Bagozzi, R. P., M. Gopinath, and P. U. Nyer. 1999. “The Role of Emotions in Marketing.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 27 (2):184–206. doi:10.1177/0092070399272005

- Bahrick, H. P. 1984. “Semantic Memory Content in Permastore: Fifty Years of Memory for Spanish Learned in School.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 113 (1):1–29. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.113.1.1

- Balasubramanian, S. K. 1994. “Beyond Advertising and Publicity: Hybrid Messages and Public Policy Issues.” Journal of Advertising 23 (4):29–46. doi:10.1080/00913367.1943.10673457

- Barrett, L. F., K. A. Lindquist, and M. Gendron. 2007. “Language as Context for the Perception of Emotion.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11 (8):327–32. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.003

- Bergkvist, L., and C. R. Taylor. 2022. “Reviving and Improving Brand Awareness as a Construct in Advertising Research.” Journal of Advertising 51 (3):294–307. DOI: 10.1080/00913367.2022.2039886

- Bergkvist, L., and K. Q. Zhou. 2016. “Celebrity Endorsements: A Literature Review and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Advertising 35 (4):642–63. doi:10.1080/02650487.2015.1137537

- Berry, L. L. 2000. “Cultivating Service Brand Equity.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28 (1):128–37. doi:10.1177/0092070300281012

- Besharat, A., and R. Langan. 2014. “Towards the Formation of Consensus in the Domain of Co-Branding: Current Findings and Future Priorities.” Journal of Brand Management 21 (2):112–32. doi:10.1057/bm.2013.25

- Braun-LaTour, K. A., and M. S. LaTour. 2004. “Assessing the Long-Term Impact of a Consistent Advertising Campaign on Consumer Memory.” Journal of Advertising 33 (2):49–61. doi:10.1080/00913367.2004.10639160

- Bright, A. K., and A. Feeney. 2014. “The Engine of Thought Is a Hybrid: Roles of Associative and Structured Knowledge in Reasoning.” Journal of Experimental Psychology. General 143 (6):2082–102. doi:10.1037/a0037653

- Brown, A. S. 1976. “Spontaneous Recovery in Human Learning.” Psychological Bulletin 83 (2):321–38. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.83.2.321

- Bruni, E., N. K. Tran, and M. Baroni. 2014. “Multimodal Distributional Semantics.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 49:1–47. doi:10.1613/jair.4135

- Burke, R. R., and T. K. Srull. 1988. “Competitive Interference and Consumer Memory for Advertising.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (1):55–68. doi:10.1086/209145

- Can, A. S., Y. Ekinci, G. Viglia, and D. Buhalis. 2020. “Stronger Together? Tourists’ Behavioral Responses to Joint Brand Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 49 (5):525–39. doi:10.1080/00913367.2020.1809574

- Cao, Z., and R. Yan. 2017. “Does Brand Partnership Create a Happy Marriage? The Role of Brand Value on Brand Alliance Outcomes of Partners.” Industrial Marketing Management 67:148–57. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.09.013

- Carrillat, F. A., and J. Ilicic. 2019. “The Celebrity Capital Life Cycle: A Framework for Future Research Directions on Celebrity Endorsement.” Journal of Advertising 48 (1):61–71. doi:10.1080/00913367.2019.1579689

- Chadwick, S., and N. Burton. 2011. “The Evolving Sophistication of Ambush Marketing: A Typology of Strategies.” Thunderbird International Business Review 53 (6):709–19. doi:10.1002/tie.20447

- Chaudhuri, A., and M. B. Holbrook. 2001. “The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty.” Journal of Marketing 65 (2):81–93. doi:10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

- Chipchase, S. Y., and P. Chapman. 2013. “Trade-Offs in Visual Attention and the Enhancement of Memory Specificity for Positive and Negative Emotional Stimuli.” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (2006) 66 (2):277–98. doi:10.1080/17470218.2012.707664

- Cohn, M., and M. Moscovitch. 2007. “Dissociating Measures of Associative Memory: Evidence and Theoretical Implications.” Journal of Memory and Language 57 (3):437–54. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2007.06.006

- Collins, A. M., and E. F. Loftus. 1975. “A Spreading-Activation Theory of Semantic Processing.” Psychological Review 82 (6):407–28. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.82.6.407

- Cornejo, C. 2004. “Who Says What the Words Say? The Problem of Linguistic Meaning in Psychology.” Theory & Psychology 14 (1):5–28. doi:10.1177/0959354304040196

- Cornwell, T. B. 2020. Sponsorship in Marketing: Effective Partnerships in Sports, Arts and Events. London: Routledge.

- Cornwell, T. B., M. S. Humphreys, E. A. Quinn, and A. R. McAlister. 2012. “Memory of Sponsorship-Linked Marketing Communications: The Effect of Competitor Mentions.” Sage Open 2 (4):215824401246813. doi:10.1177/2158244012468139

- Cornwell, T. B., and H. Katz. 2021. Influencer: The Science behind Swaying Others. New York: Routledge.

- Cornwell, T. B., and Y. Kwon. 2020. “Sponsorship-Linked Marketing: Research Surpluses and Shortages.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 48 (4):607–29. doi:10.1007/s11747-019-00654-w

- Cornwell, T. B., O. V. Lipp, and H. Purkis. 2016. “Examination of Affective Responses to Images in Sponsorship-Linked Marketing.” Journal of Global Sport Management 1 (3-4):110–28. doi:10.1080/24704067.2016.1240947

- Cunha, M., Jr., M. R. Forehand, and J. W. Angle. 2015. “Riding Coattails: When Co-Branding Helps versus Hurts Less-Known Brands.” Journal of Consumer Research 41 (5):1284–300. doi:10.1086/679119

- De Deyne, S., D. J. Navarro, A. Perfors, M. Brysbaert, and G. Storms. 2019. “The “Small World of Words” English Word Association Norms for over 12,000 Cue Words.” Behavior Research Methods 51 (3):987–1006. doi:10.3758/s13428-018-1115-7

- De Veirman, M., V. Cauberghe, and L. Hudders. 2017. “Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude.” International Journal of Advertising 36 (5):798–828. doi:10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035

- Dennis, S., and M. S. Humphreys. 2001. “A Context Noise Model of Episodic Word Recognition.” Psychological Review 108 (2):452–78. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.452

- Donthu, N., W. M. Lim, S. Kumar, and D. Pattnaik. 2022. “The Journal of Advertising’s Production and Dissemination of Advertising Knowledge: A 50th Anniversary Commemorative Review.” Journal of Advertising 51 (2):153–87. DOI: 10.1080/00913367.2021.2006100

- Dyne, A. M., M. S. Humphreys, J. D. Bain, and R. Pike. 1990. “Associative Interference Effects in Recognition and Recall.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 16 (5):813–24. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.16.5.813

- Edeling, A., S. Hattula, and T. Bornemann. 2017. “Over, out, but Present: Recalling Former Sponsorships.” European Journal of Marketing 51 (7/8):1286–307. doi:10.1108/EJM-05-2015-0263

- Einstein, G. O., and R. R. Hunt. 1980. “Levels of Processing and Organization: Additive Effects of Individual-Item and Relational Processing.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory 6 (5):588–98. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.6.5.588

- Erfgen, C., S. Zenker, and H. Sattler. 2015. “The Vampire Effect: When Do Celebrity Endorsers Harm Brand Recall?” International Journal of Research in Marketing 32 (2):155–63. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2014.12.002

- Farquhar, P. H. 1989. “Managing Brand Equity.” Marketing Research 1 (3):24–33.

- Goss, A. E., and C. F. Nodine. 2014. Paired-Associates Learning: The Role of Meaningfulness, Similarity, and Familiarization. New York: Academic Press.

- Gregory, S. 2021. “Brands Continue to Back Naomi Osaka, Showing an evolution in How Sponsors Treat Athletes.” Time.com, June 7. https://time.com/6071645/naomi-osaka-french-open-sponsors-brands/.

- Gumperz, J. J. 1962. “Types of Linguistic Communities.” Anthropological Linguistics 4 (1):28–40.

- Hansen, N., A. K. Kupfer, and T. Hennig-Thurau. 2018. “Brand Crises in the Digital Age: The Short-and Long-Term Effects of Social Media Firestorms on Consumers and Brands.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 35 (4):557–74. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2018.08.001

- Harnad, S. 1990. “The Symbol Grounding Problem.” Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 42 (1-3):335–46. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(90)90087-6

- Henderson, G. R., D. Iacobucci, and B. J. Calder. 1998. “Brand Diagnostics: Mapping Branding Effects Using Consumer Associative Networks.” European Journal of Operational Research 111 (2):306–27. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(98)00151-9

- Hillebrand, B., P. H. Driessen, and O. Koll. 2015. “Stakeholder Marketing: Theoretical Foundations and Required Capabilities.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43 (4):411–28. doi:10.1007/s11747-015-0424-y

- Humphreys, M. S. 1976. “Relational Information and the Context Effect in Recognition Memory.” Memory & Cognition 4 (2):221–32. doi:10.3758/BF03213167

- Humphreys, M. S., J. D. Bain, and R. Pike. 1989. “Different Ways to Cue a Coherent Memory System: A Theory for Episodic, Semantic, and Procedural Tasks.” Psychological Review 96 (2):208–33. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.208

- Humphreys, M. S., and K. A. Chalmers. 2016. Thinking about Human Memory. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Humphreys, M. S., T. B. Cornwell, A. R. McAlister, S. J. Kelly, E. A. Quinn, and K. L. Murray. 2010. “Sponsorship, Ambushing, and Counter-Strategy: Effects upon Memory for Sponsor and Event.” Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied 16 (1):96–108. doi:10.1037/a0018031

- IEG Sponsorship Report. 2017. “IEG’s Guide to Sponsorship.” https://www.sponsorship.com/ieg/files/59/59ada496-cd2c-4ac2-9382-060d86fcbdc4.pdf.

- IEG Sponsorship Report. 2018. “Signs Point to Healthy Sponsorship Spending in 2018.” January 16. https://www.sponsorship.com/About/Press-Room/Signs-Point-To-Healthy-Sponsorship-Spending-In-201.aspx.

- Influencer Marketing Hub. 2022. “The State of Influencer Marketing 2022: Benchmark Report.” March 2. https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/.

- Janiszewski, C., H. Noel, and A. G. Sawyer. 2003. “A Meta-Analysis of the Spacing Effect in Verbal Learning: Implications for Research on Advertising Repetition and Consumer Memory.” Journal of Consumer Research 30 (1):138–49. doi:10.1086/374692

- Keller, K. L. 1993. “Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity.” Journal of Marketing 57 (1):1–22. doi:10.1177/002224299305700101

- Keller, K. L. 2020. “Leveraging Secondary Associations to Build Brand Equity: Theoretical Perspectives and Practical Applications.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (4):448–65. doi:10.1080/02650487.2019.1710973

- Kelly, S. J., T. B. Cornwell, and K. Singh. 2019. “The Gladiatorial Sponsorship Arena: How Ambushing Impacts Memory.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 37 (4):417–32. doi:10.1108/MIP-07-2018-0271

- Kelly, S. J., T. B. Cornwell, L. V. Coote, and A. R. McAlister. 2012. “Event-Related Advertising and the Special Case of Sponsorship-Linked Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 31 (1):15–37. doi:10.2501/IJA-31-1-15-37

- Kelting, K., and D. H. Rice. 2013. “Should We Hire David Beckham to Endorse Our Brand? Contextual Interference and Consumer Memory for Brands in a Celebrity’s Endorsement Portfolio.” Psychology & Marketing 30 (7):602–13. doi:10.1002/mar.20631

- Kerr, G., and J. Richards. 2021. “Redefining Advertising in Research and Practice.” International Journal of Advertising 40 (2):175–98. doi:10.1080/02650487.2020.1769407

- Kim, D. Y., and H. Y. Kim. 2021. “Influencer Advertising on Social Media: The Multiple Inference Model on Influencer-Product Congruence and Sponsorship Disclosure.” Journal of Business Research 130:405–15. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.020

- Kotler, P. 2000. Marketing Management: The Millennium Edition. Vol. 10. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Kumar, A. A. 2021. “Semantic Memory: A Review of Methods, Models, and Current Challenges.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 28 (1):40–80. doi:10.3758/s13423-020-01792-x

- Kumar, A. A., M. Steyvers, and D. A. Balota. 2022. “A Critical Review of Network-Based and Distributional Approaches to Semantic Memory Structure and Processes.” Topics in Cognitive Science 14 (1):54–77. doi:10.1111/tops.12548

- Lascelles, A. 2022. “What’s the Alternative to Russian Vodka?.” ft.com, April 21. https://www.ft.com/content/7a035276-9b2f-40ea-8836-32af636bf3cf.

- Lederer, C., and S. Hill. 2001. “See Your Brands through Your Customers’ Eyes.” Harvard Business Review 79 (6):125–33.

- Lee, J. S., H. Chang, and L. Zhang. 2022. “An Integrated Model of Congruence and Credibility in Celebrity Endorsement.” International Journal of Advertising 41 (7):1358–81. DOI: 10.1080/02650487.2021.2020563

- Levine, L. J., and R. S. Edelstein. 2009. “Emotion and Memory Narrowing: A Review and Goal-Relevance Approach.” Cognition & Emotion 23 (5):833–75. doi:10.1080/02699930902738863

- Lindquist, K. A., A. B. Satpute, and M. Gendron. 2015. “Does Language Do More than Communicate Emotion?” Current Directions in Psychological Science 24 (2):99–108. doi:10.1177/0963721414553440

- Lodish, L. M., M. M. Abraham, J. Livelsberger, B. Lubetkin, B. Richardson, and M. E. Stevens. 1995. “A Summary of Fifty-Five in-Market Experimental Estimates of the Long-Term Effect of TV Advertising.” Marketing Science 14 (3_supplement):G133–40. doi:10.1287/mksc.14.3.G133

- Macdonald, E. K., and B. M. Sharp. 2000. “Brand Awareness Effects on Consumer Decision Making for a Common, Repeat Purchase Product: A Replication.” Journal of Business Research 48 (1):5–15. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(98)00070-8

- Mak, M. H., and H. Twitchell. 2020. “Evidence for Preferential Attachment: Words That Are More Well Connected in Semantic Networks Are Better at Acquiring New Links in Paired-Associate Learning.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 27 (5):1059–69. doi:10.3758/s13423-020-01773-0

- Martinez, D., and P. O’Rourke. 2020. “Differential Involvement of Working Memory Capacity and Fluid Intelligence in Verbal Associative Learning as a Possible Function of Strategy Use.” The American Journal of Psychology 133 (4):427–51. doi:10.5406/amerjpsyc.133.4.0427

- McAlister, A. R., S. J. Kelly, M. S. Humphreys, and T. B. Cornwell. 2012. “Change in a Sponsorship Alliance and the Communication Implications of Spontaneous Recovery.” Journal of Advertising 41 (1):5–16. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367410101

- McCracken, G. 1989. “Who Is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundations of the Endorsement Process.” Journal of Consumer Research 16 (3):310–21. doi:10.1086/209217

- Meenaghan, J. A. 1983. “Commercial Sponsorship.” European Journal of Marketing 17 (7):5–73. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000004825

- Meyers, A. 2021. “Nike, Coca-Cola Are the Brands Most Associated with the Olympics.” Morning Consult, August 13. https://morningconsult.com/2021/08/13/olympic-brands-association-poll/.

- Mizik, N. 2014. “Assessing the Total Financial Performance Impact of Brand Equity with Limited Time-Series Data.” Journal of Marketing Research 51 (6):691–706. doi:10.1509/jmr.13.0431

- Mogaji, E., F. A. Badejo, S. Charles, and J. Millisits. 2022. “To Build My Career or Build My Brand? Exploring the Prospects, Challenges and Opportunities for Sportswomen as Human Brand.” European Sport Management Quarterly 22 (3):379–97. doi:10.1080/16184742.2020.1791209