Abstract

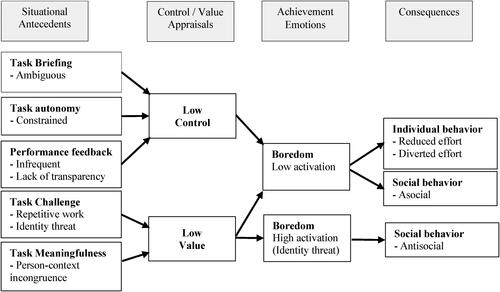

Despite its high incidence in the workplace, boredom is yet to be examined in the context of the creative studio. This concern is particularly pertinent because creative personality types are reported to be more boredom prone than others and because, in general, boredom is negatively associated with motivation, a key determinant of creativity and workplace performance. Using control-value theory (CVT) and based on interviews with more than 30 creatives, this article reveals situational antecedents, with their associated control and value appraisals, which lead to creatives becoming bored. Poor briefing, lack of autonomy, and insufficient feedback lead to low control appraisals, while repetition and task-identity incongruence result in low value appraisals. The article examines the consequences of boredom both in terms of individual (reduced or diverted effort) and social (asocial or antisocial) behavior. It also recommends strategies for suppressing the emergence of boredom in the studio.

We speak of all sorts of terrible things that happen to people, but we rarely speak about one of the most terrible of all; that is, being bored. (Fromm Citation1997, p. 118)

Despite being a common emotion in the workplace, boredom—an aversive state of wanting but being unable to engage in satisfying activity—is poorly understood and worthy of further research (Raffaelli, Mills, and Christoff Citation2018). In advertising literature, emotions have been studied in relation to advertising appeals (Poels and Dewitte Citation2019), advertising outcome variables (e.g., Eisend Citation2017), and relational bonds between clients and their advertising agencies (e.g., Chu et al. Citation2019). Boredom itself has been studied in connection with advertising repetition (e.g., Schmidt and Eisend Citation2015). However, as a workplace phenomenon in the creative industries, boredom has been largely ignored. This fact is surprising given its negative impact on motivation (Mael and Jex Citation2015). Motivation determines the intensity, direction, and duration of work-related behavior and is important because it has a positive impact on creativity (Amabile and Pratt Citation2016).

Based on interviews with more than 30 creatives, the aim of this research is to explore the antecedents and impact of boredom in the creative studio and identify strategies to alleviate it. While there is a limited number of studies investigating the impact of boredom on creativity, a search of the literature suggests this is the first study of boredom in a real-world creative context. Previous studies recruited participants from the general population (Mann and Cadman Citation2014) or from students (Gasper and Middlewood Citation2014). Given that boredom proneness varies by personality type, and creativity is associated with specific personality variables (Hunter et al. Citation2016), conducting research with creatives themselves may reveal new insights. Furthermore, these predominantly laboratory-based studies induce boredom in participants and then switch them to a new task before measuring creativity. The relief experienced by switching to a new task will likely have a positive impact on motivation and performance; these previous studies are not measuring the experience and impact of boredom during a tedious task. The only study (Haager, Kuhbander, and Pekrun Citation2018) to explore creativity in the context of task-induced boredom also recruits participants from the student population. Regarding research setting, research into boredom in a natural work environment will complement laboratory-based experiments. While the latter offer a high degree of control, the setting is artificial. Research in a work setting means participants are engaged in activities as normal in a real-world context (Fine and Elsbach Citation2000). An additional advantage is the longevity of the boredom experience. Participants in a laboratory experiment will be aware that their boredom will be transient. Workplace boredom, on the other hand, has the potential to be long term with no anticipated relief.

The study is justified because, despite its potential to diminish motivation and creativity, boredom has escaped attention in the context of workplaces where creativity is an integral part of people’s jobs. This study employs control-value theory (CVT) (Pekrun Citation2006) as its theoretical framework. CVT proposes that an individual’s motivation and behavior are influenced by positive or negative emotions that result from an assessment of personal control over, and perceived value of, activities and outcomes.

There follows a review of literature on the dimensions, causes, and consequences of boredom and a description of CVT. The research method is outlined, and it is followed by study findings. The article concludes with a discussion of the findings and practitioner implications.

Literature

Boredom

Although definitions of workplace boredom vary, there is agreement on several fundamentals. State, as opposed to chronic, boredom is situation specific and transient (Fisher Citation1993). It is an unpleasant and dissatisfying experience and considered an affective state of low arousal (Eastwood et al. Citation2012), although in some instances sufferers of boredom experience high arousal such as frustration (Merrifield and Danckert Citation2014). There are cognitive components too, such as lack of interest in an activity and mind wandering (Smallwood and Schooler Citation2015).

There are several potential causes of boredom including routine, constraint, and excessive or insufficient challenge (Cummings, Gao, and Thornburg Citation2016; Niemiec and Ryan Citation2009). Consequences of boredom include a lack of engagement, reduced task performance, and a greater propensity to make mistakes (Camacho-Morles et al. Citation2021).

Control-Value Theory

CVT (Pekrun Citation2006) provides an appropriate framework with which to explore boredom. What distinguishes CVT from its close relative self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan and Deci Citation2000) is its focus on emotions, their antecedents, and their impact on competency-based and achievement-related activities and outcomes. SDT has been used extensively to study the relationship between motivation and creativity (see Liu et al. Citation2016). However, unlike CVT, which acknowledges the interplay between emotions and motivation, SDT is seldom used to study the impact of emotions on motivation and performance (see Sutter-Brandenberger, Hagenauer, and Hascher Citation2018). Given that CVT is the dominant framework for studying emotions in achievement settings, with empirical evidence to support the directional link between environmental antecedents, cognitive appraisals, emotions, and performance (Buhr, Daniels, and Goegan Citation2019), it is more likely than other theories of motivation to increase understanding of the impact of boredom, a negative emotion, on creative performance.

CVT argues that, on the basis of cognitive appraisals of an activity and/or its outcome, individuals experience emotions that are positive or negative, activating or deactivating. Emotions influence motivation, which impacts performance. There are two types of appraisals: control and value.

Control comprises expectancies and attributions. Expectancy is the extent to which the individual can exert influence over an activity, while attribution is the retrospective appraisal of the causes of an outcome (Pekrun Citation2006). Besides control, individuals appraise the intrinsic and extrinsic value of an activity or outcome. Intrinsic value derives from activities that are inherently satisfying, while extrinsic value describes outcomes that have instrumental usefulness (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). Positive emotions should maximize, and negative emotions reduce, motivation and performance (Tze, Daniels, and Klassen Citation2016). Based on these theories, three research questions are presented:

RQ1: What control and value appraisals lead to task-related boredom in the real-world context of a creative workplace?

RQ2: What are the consequences of task-related boredom in the real-world context of a creative workplace?

RQ3: How can leaders of creative studios suppress or mitigate boredom?

Method

Data Collection and Analysis

Given the purpose of the research was exploratory, the author adopted a qualitative approach. Using member lists from U.K. trade organizations, the author identified and contacted 75 agencies with 20 or more employees. Agencies of this size were more likely to work with an extensive client list and have a diverse set of experiences. A total of 16 agencies agreed to participate. Although precise terminology varied, each was a full-service/integrated communications agency. There were 32 individual participants, with two creatives from each agency. Interviewing stopped after 32 interviews because the researcher judged data saturation had been reached and that further interviews would be unlikely to reveal additional insights. The stopping criterion was four consecutive interviews with no new ideas or themes (see Francis et al. Citation2010). In terms of participant industry experience, the minimum was 10 years and the maximum was 34 years. Agency size ranged from 25 to 65 employees. Contextual information for the participants is contained in . Interviews were conducted June to September 2020 using Microsoft Teams.

Table 1. Contextual information for research participants.

Interviews were one-on-one and semistructured. The interview protocol covered the incidence and identification of boredom, antecedents, consequences, and mitigation strategies. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Average interview duration was 58 minutes.

Data analysis, using NVivo 12, started with the author attaching descriptive codes to units of text in each transcript. In the interests of internal reliability, an experienced researcher-colleague also coded six transcripts. Evaluation of intercoder agreement, using Perreault and Leigh’s (Citation1989) measure for two judges, produced a coefficient of 0.84, which was deemed acceptable and confirmation of reliability (see Rust and Cooil Citation1994). Once coding was complete, first-order codes were abstracted to the categorical themes of control and value. For example, being “spoon-fed” solutions by the client was abstracted to [lack of] control. Meaningless work was abstracted to [lack of] intrinsic value. Having nothing significant to show for time spent on a task was abstracted to [lack of] extrinsic value. Experiences of monotony, tedium, and, of course, boredom were abstracted to boredom. Consequences of boredom were categorized as individual behaviors related to effort and social behaviors related to interactions with colleagues.

Regarding validity, the researcher conducted pilot interviews with two senior industry practitioners to check clarity and relevance. Study participants were invited to review their respective transcripts. Four accepted the offer and confirmed their transcripts were accurate reflections of what they had said. Once analyzed, the author shared data from the whole sample with all participants, asking if the summary reflected their experiences. Ten participants responded. Nothing in their responses necessitated a reinterpretation. Finally, the author shared the findings, in a workshop, with industry practitioners. Of the 28 that attended, 11 had participated in the study. The remaining 17 attendees shared similar characteristics (role, seniority, and agency profile) with the participants. The event confirmed that data analysis and interpretation were credible and transferable beyond the sample, and no new theoretical insight was generated.

Findings

The findings are structured according to control and value appraisals and their respective antecedents and consequences. Strategies to mitigate the emergence of boredom are addressed. displays antecedents, control-value appraisals, emotions, and consequences identified in the research.

Control Appraisals

Three situational factors had an impact on control appraisals: quality of task briefing, level of task autonomy, and the quality of performance feedback. When appraised unfavorably, they induced boredom and reduced motivation to invest cognitive resources in a task.

Task Briefing

Poor quality task briefing by clients leads creatives to conclude there is insufficient control to produce an effective outcome:

We frequently find that clients can’t articulate what they want. You can’t solve a problem when you don’t know what it is you are meant to be solving. You end up with totally bored and disengaged creatives. (Emma, creative director)

The brief is like a fishing net. There are more holes than material. We have to decode and clarify what they are asking for, but the client gets resentful and says, “You’re supposed to be helping me.” It’s frustrating and has a negative impact on enthusiasm and energy levels. (Joe, graphic designer)

Participants highlighted the mitigating effects of a good client relationship. It gives them confidence to query and clarify the brief. Improvements in the quality of the brief enhance the perceived level of control and increase engagement.

Task Autonomy

Lack of task autonomy was a second cause of low control appraisal. Creatives are constrained by an overly prescriptive brief, leading to the loss of a sense of agency:

Sometimes the decisions are made for you. You’re spoon-fed everything. If you’re not given the freedom to be creative, you get bored. The enthusiasm goes, and your heart’s not in it. You’re no longer proud of it, because you no longer own it. (Andy, creative director)

It’s a sad place to be when they say, “Just do it.” You end up disillusioned and then bored by the whole experience. (Nick, graphic designer)

Performance Feedback

Poor quality performance feedback from the client was the third antecedent of perceived lack of control. There were two elements: infrequent feedback and lack of transparency. Infrequent feedback means there is a lack of understanding of what represents a successful outcome:

How can you do well if you aren’t told the impact of what you are doing? You end up working blind, hoping it’s working . . . but you quickly lose interest. It’s demotivating. (Leo, creative director)

You’re far more likely to put effort into impressing the client if you feel like your work is appreciated. When they say nothing, you think, “Why bother?” (Vicky, graphic designer)

To mitigate the lack of feedback, some made an effort within the agency to recognize achievements: “Whatever the achievement, celebrate it, even the dull stuff, the non-award-winning stuff. You show people there’s value in it. If they get respect, they put more effort in” (Harry, art director).

Value Appraisals

Task Challenge

The extent to which a task was challenging or meaningful influenced value perceptions. There were two elements to task challenge: repetition and identity threat. Repetitive work leads to boredom and reduced motivation:

Change and challenge keep us going. Everyone wants to work on an exciting pitch. People get bored with stuff that’s been around for a while. (Nancy, creative director)

When creatives are asked to dedicate their lives to one client and one brief, year after year, they just regurgitate the same stuff, and it gets very boring. (Scott, art director)

The issue of underchallenging work is related to work identity or the meanings that individuals attach to themselves (Gergen Citation1991). Several participants identified two personality types, variously called “climbers and campers” or “hunters and farmers.” The climbers/hunters have a strong sense of identity and a clear idea of the type of work that nurtures their identity. They see no value in repetitive and underchallenging work and consider it an identity threat: “The climbers know what they want in life. They love creating big ideas. The mundane is for someone else. Give them the wrong job and you can see their boredom, their physical agitation” (Steve, creative director). When climbers appraise an identity-implicating task to be of low value, their emotional and behavioral responses are negative (compare Bataille and Vough Citation2022). Matt, an art director, agreed: “When I look at my team, we have hunters and farmers. The hunters are fantastic at coming up with initial concepts, big ideas. But as soon as you ask them to work on something that’s been done before, they’re bored.”

Task Meaningfulness

In addition to cognitive challenge, value is assessed by task meaningfulness, or the relevance of the task context. Person-context incongruence leads to a low value appraisal:

I did some work for an adoption agency. I had a real desire to produce a great outcome. On the other hand, when it’s something I can’t connect with, like we had a client in the defense sector, I soon get bored. (Gillian, graphic designer)

One of our clients is in the financial services sector. I worked on a thirty-two-page brochure on mergers and acquisitions. It meant nothing to me. There’s no satisfaction in the work. It was so incredibly tedious. (David, graphic designer)

Regarding the interaction between control and value appraisals, the findings suggest that even when levels of control are high, boredom will still occur if the value appraisal is low:

There are some projects where we already know the coordinates. We’ve worked on it for the last five years. We know the brand, what works, and what the client likes. There’s no challenge. We become stale, bored, and the result is monotone. (Mike, creative director)

With regard to managing boredom from low value appraisals, Tom, a creative director, reminds the team of the importance of even mundane work: “Every job is a gift. However mundane, it pays our wages, so we can’t be complacent.” Christine, a creative director, who associated boredom with the danger of appearing complacent, stressed the need to look for incremental improvements in repetitive work: “We need to be thinking, ‘It’s good, but how can we make it better?’” Vanessa, also a creative director, prefers to highlight the significance of the work for the client:

Instead of saying, “The client needs a PowerPoint presentation,” provide some context so they understand the impact their work will have. Tell them the client will be standing in front of three hundred of the most influential financiers in the U.K.

Consequences

This study identified both low- and high-activation boredom (Eastwood et al. Citation2012). Low-activation boredom has a negative impact on intensity and duration of effort, leading to substandard performance (Harju and Hakanen Citation2016). As Andy, a creative director, put it, “Copy, paste, bang, done. It’s about minimum effort. There’s no motivation to do more.” A second consequence is the diversion of attention to a simultaneous, irrelevant activity, leading to reduced creativity or error:

If I listen to music, I can let it wash over me. But if I’m listening, for example, to an audio book, my brain has to imagine the characters and the environment. I’m using the creative part of my brain, which should be focused on my work, to paint a picture of the story in my head. (Jill, art director)

They think to themselves, “This is fine. I’ve done this so many times before; I’ll learn French while I’m doing this.” Well, it’s not fine. They’re not giving it one hundred percent attention. We end up with lots of silly mistakes. (Tom, creative director)

When I’m bored, I do the job, but when I get to the end I have little recollection of having done it. I’ve been thinking about other stuff, like what I’m going to have for dinner. That’s when error creeps in. (Emma, creative director)

They don their headphones at nine a.m. and take them off at five p.m. There’s no point them being in the studio. The studio feeds off banter and noise. It stimulates the creative mind and creates a dynamic in the studio. People who disconnect do nothing to build a vibrant and creative environment. (Steve, creative director)

Ask them to do the wrong job and their boredom and frustration becomes very evident. It cascades down to the juniors in the team. It’s pervasive and you can feel productivity across the team begin to slide. (Mike, creative director)

If you take one of the firestarters, one of the highly creative designers, and put them on a mundane task, it will be painful for you, for them, and for the whole studio. They will kick, scream, and pull their hair out. (Sarah, creative director)

Discussion

Given boredom’s ubiquity, it is surprising it has been ignored in the context of the creative industries. Perhaps this is because boredom usually results in low-activation behavior, which is harder to discern than, for example, anxiety or stress. However, given its counterproductive consequences, it deserves attention.

This study contributes to the literature on affect and creativity. Previous studies acknowledge that positive affect increases cognitive flexibility and, by implication, negative affect has the opposite result (compare Amabile and Pratt Citation2016). However, studies that specifically focus on boredom’s impact on creativity are sparse. Those that do so use samples from the general population or students, rather than from those whose job it is to be creative every day. Furthermore, with few exceptions (see Haager, Kuhbander, and Pekrun Citation2018), existing studies explore consequences as a result of lab-induced boredom rather than real-world, task-related boredom.

This study shows how unfavorable appraisals of control and value lead to boredom. Of the situational antecedents of boredom revealed in this study, constraint, repetition, and lack of meaning feature in previous studies (compare Daschmann, Goetz, and Stupnisky Citation2014). Poor-quality task briefing and performance feedback from the client, which prompted low control appraisals, and identity threat, which prompted low value appraisal, have not previously been associated with boredom. Given the impact of the client’s brief and feedback on agency output, it is not surprising that when these are of poor quality, control appraisals will be low and interest in a task will diminish. Regarding identity threat, climbers or hunters position themselves at the top of the agency’s creative hierarchy and attach no value to mundane work. It bores them and imperils their status (see Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003).

Regarding the consequences of boredom, a reduction in task-related attention, with negative consequences for output quality, has been identified in other settings (e.g., Pekrun et al. Citation2010). However, the negative impact of individual boredom on the wider team is, to the best of the author’s knowledge, new. Regarding asocial behavior, which is a lack of engagement in citizenship behavior, there is no suggestion of malice. Individuals seek diversion from monotony by immersing themselves in another world; in doing so, however, they shirk their responsibility to nurture organizational culture. More pernicious is boredom that emanates from the allocation of an identity-threatening task, leading to antisocial behavior.

Some studies suggest boredom can positively influence creative performance (Gasper and Middlewood Citation2014; Mann and Cadman Citation2014). The explanation for these conflicting findings may lie in the research setting and the longevity of the boredom experience. Participants in laboratory-based experiments are aware their artificially induced boredom will be short-lived. In contrast, in a workplace setting, a creative’s job may have become routine, with no intrinsic or instrumental value. There is no anticipated relief from what has most likely become chronic boredom. This difference in findings highlights the knowledge contribution that can emerge from a field study as opposed to a laboratory experiment.

Research sample and setting may explain the present study’s finding of an association between boredom and identity threat. First, self-perceived expertise will probably be stronger among agency creatives than, for example, students. Second, an artificial laboratory-based experiment is unlikely to trigger concerns about identity threat. The significance of research setting (laboratory versus naturalistic) is supported by previous studies that highlight the influence it can have on boredom intensity (e.g., De Wijk et al. Citation2019). Ulimately, given the inevitable strengths and weaknesses of individual research methods, the advancement of our understanding of boredom benefits from a range of approaches.

Managerial Implications

Several options are available to mitigate boredom. Job rotation can refresh cognitive engagement leading to performance improvements when an individual resumes the original task. That said, boredom proneness varies. Some personality types prefer predictability to novelty and may experience anxiety when moved out of their comfort zone.

Job rotation may be impractical in small agencies. In this case, reframing an old problem to change the range of possible solutions and increase task engagement may be more relevant. By challenging the perception that problem boundaries and solutions are predetermined, there is scope to recast the problem and explore new solutions.

Highlighting the prosocial contribution of a task can increase value perceptions. Furthermore, peer appreciation leads to positive affect, enhancing an individual’s motivation. Employees are more likely to find meaning in their work when they are reminded of the value of the outcome to the agency, client, or end user (compare Gauri et al. Citation2021).

Although clients might argue that the emotions of the creative team are not their concern, they should be cognizant of the impact their actions have on agency output. A high-quality brief, creative autonomy, and regular and transparent feedback will enhance a creative’s sense of control over a job. These are areas where agencies can help clients. For example, offering to cocraft the brief with clients who are increasingly time poor will produce a better-quality document. Alternatively, furnishing the client with a briefing template will help clients understand what a good brief looks like (Vafeas Citation2021).

The power of relational goodwill to counteract boredom and maintain engagement, even during mundane tasks, is striking. It underlines the importance of nurturing the client–agency relationship for mutual benefit. Literature on leader–member exchanges supports the view that member (i.e., agency) performance is positively related to liking the leader (i.e., the client) and is manifested through extra effort (compare Dulebohn, Wu, and Liao Citation2017).

Limitations and Future Research

Participants were senior creatives with a minimum 10 years in the industry. Future studies could seek the views of those newer to the profession to explore the extent to which boredom is influenced by longevity in the industry or other demographic characteristics. Future research could explore differences in the antecedents and consequences of transitory versus prolonged boredom. Routine exposure to tasks that are perceived to be of low value could lead to chronic boredom. Excessive boredom has implications for performance, staff turnover, and well-being.

Future studies could also explore the predictors and impact of a wider variety of emotions. This could include negative emotions, such as frustration and anger, but also positive emotions, such as contentment and pride. There is scope for research into the interactive effects of situational antecedents. Findings in this study suggest value appraisals override those of control. But is there a tipping point where this effect no longer holds? Laboratory-based experiments have sometimes shown that, after a period of engagement in a boring task, participants display heightened creativity in new tasks. To what extent does this hold in practice? Finally, after a period of intense creativity, is boredom an opportunity to recharge cognitive resources? Research could also investigate the extent to which this feeling is prevalent.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mario Vafeas

Mario Vafeas (PhD, University of the West of England) is a professor of marketing, Bristol Business School, University of the West of England.

References

- Amabile, Teresa M. 1997. “Motivating Creativity in Organizations: On Doing What You Love and Loving What You Do.” California Management Review 40 (1):39–58.

- Amabile, Teresa M., and Michael G. Pratt. 2016. “The Dynamic Componential Model of Creativity and Innovation in Organizations: Making Progress, Making Meaning.” Research in Organizational Behavior 36:157–83.

- Bataille, Christine, and Heather Vough. 2022. “More Than the Sum of My Parts: An Intrapersonal Network Approach to Identity Work in Response to Identity Opportunities and Threats.” Academy of Management Review 47 (1):93–115.

- Buhr, Erin, Lia Daniels, and Lauren Goegan. 2019. “Cognitive Appraisals Mediate Relationships Between Two Basic Psychological Needs and Emotions in a Massive Open Online Course.” Computers in Human Behavior 96:85–94.

- Camacho-Morles, Jésus, Gavin Slemp, Reinhard Pekrun, Kristina Loederer, Hanchao Hou, and Lindsay Oades. 2021. “Activity Achievements and Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Psychology Review 33:1051–95.

- Chen, Yaru, and Trish Reay. 2021. “Responding to Imposed Job Redesign: The Evolving Dynamics of Work and Identity in Restructuring Professional Identity.” Human Relations 74 (10):1541–71.

- Chu, Shu-Chuan, Yang Cao, Jing Yang, and Juan Mundel. 2019. “Understanding Advertising Client-Agency Relationships in China: A Multimethod Approach to Investigate Guanxi Dimensions in Agency Performance.” Journal of Advertising 48 (5):473–94.

- Cummings, Mary, Fei Gao, and Kris Thornburg. 2016. “Boredom in the Workplace: A New Look at an Old Problem.” Human Factors 58 (2):279–300.

- Daniels, Lia. 2020. “Objective Score versus Subjective Satisfaction: Impact on Emotions following Immediate Score Reporting.” Journal of Experimental Education 88 (4):578–94.

- Daschmann, Elena C., Thomas Goetz, and Robert H. Stupnisky. 2014. “Exploring the Antecedents of Boredom: Do Teachers Know Why Students Are Bored?” Teaching and Teacher Education 39:22–30.

- De Wijk, Rene A., Daisuke Kaneko, Garmt B. Dijksterhuis, Manouk van Zoggel, Irene Schiona, Michel Visalli, and Elizabeth Zandstra. 2019. “Food Perception and Emotion Measured over Time in-Lab and in-Home.” Food Quality and Preference 75:170–8.

- Dulebohn, James, Dongyuan Wu, and Chenwei Liao. 2017. “Does Liking Explain Variance above and beyond LMX?” Human Resource Management Review 27 (1):149–66.

- Eastwood, John D., Alexandra Frischen, Mark J. Fenske, and Daniel Smilek. 2012. “The Unengaged Mind: Defining Boredom in Terms of Attention.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 7 (5):482–95. doi:10.1177/1745691612456044

- Eisend, Martin. 2017. “Meta-Analysis in Advertising Research.” Journal of Advertising 46 (1):21–35.

- Fine, Gary, and Kimberly Elsbach. 2000. “Ethnography and Experiment in Social Psychology Theory Building.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 36 (1):51–76.

- Fisher, Cynthia. 1993. “Boredom at Work: A Neglected Concept.” Human Relations 46:395–417.

- Francis, Jill, Marie Johnston, Clare Robertson, Liz Glidewell, Vikki Entwistle, Martin Eccles, and Jeremy Grimshaw. 2010. “What Is an Adequate Sample Size? Operationalising Data Saturation for Theory-Based Interview Studies.” Psychology & Health 25 (10):1229–45. doi:10.1080/08870440903194015

- Fromm, Erich. 1997. Love, Sexuality, and Matriarchy: About Gender. New York: Fromm International Publishing.

- Gasper, Karen, and Brianna L. Middlewood. 2014. “Approaching Novel Thoughts: Understanding Why Elation and Boredom Promote Associative Thought More than Distress and Relaxation.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 52:50–7.

- Gauri, Varun, Julian Jamison, Nina Mazar, and Owen Ozier. 2021. “Motivating Bureaucrats through Social Recognition.” Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 163:117–31.

- Gergen, Kenneth J. 1991. The Saturated Self: Dilemmas of Identity in Contemporary Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Haager, Julia S., Christof Kuhbander, and Reinhard Pekrun. 2018. “To Be Bored or Not to Be Bored: How Task-Related Boredom Influences Creative Performance.” Journal of Creative Behaviour 52 (4):297–304.

- Harju, Lotta, and Jari Hakanen. 2016. “An Employee Who Was Not There: A Study of Job Boredom in White Collar Work.” Personnel Review 5 (2):374–91.

- Hunter, Jennifer A., Eleanor H. Abraham, Andrew G. Hunter, Lauren C. Goldberg, and John D. Eastwood. 2016. “Personality and Boredom Proneness in the Prediction of Creativity and Curiosity.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 22:48–57.

- Liu, Dong, Kaifeng Jiang, Christina Shalley, Sejin Keem, and Jing Zhou. 2016. “Motivational Mechanisms of Employee Creativity: A Meta-Analytical Examination and Theoretical Extension of the Creativity Literature.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 137:236–63.

- Mael, Fred, and Steve Jex. 2015. “Workplace Boredom: An Integrative Model of Traditional and Contemporary Approaches.” Group and Organization Management 42 (2):131–59.

- Mann, Sandi, and Rebekah Cadman. 2014. “Does Being Bored Make Us More Creative?” Creativity Research Journal 26 (2):165–73.

- Merrifield, Colleen, and James Danckert. 2014. “Characterising the Psychophysiological Signature of Boredom.” Experimental Brain Research 232 (2):481–91. doi:10.1007/s00221-013-3755-2

- Niemiec, Christopher P., and Richard M. Ryan. 2009. “Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the Classroom: Applying Self-Determination Theory to Educational Practice.” Theory and Research in Education 7 (2):133–44.

- Pekrun, Reinhard. 2006. “The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice.” Educational Psychology Review 18:315–41.

- Pekrun, Reinhard, Thomas Goetz, Lia M. Daniels, Robert H. Stupnisky, and Raymond P. Perry. 2010. “Boredom in Achievement Settings: Exploring Control-Value Antecedents and Performance Outcomes of a Neglected Emotion.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (3):531–49.

- Perreault, William, and Laurence Leigh. 1989. “Reliability of Nominal Data on Qualitative Judgements.” Journal of Marketing Research 26 (2):135–48.

- Poels, Karolien, and Siegfried Dewitte. 2019. “The Role of Emotions in Advertising: A Call to Action.” Journal of Advertising 48 (1):81–90.

- Raffaelli, Quentin, Caitlin Mills, and Kaitlin Christoff. 2018. “The Knowns and Unknowns of Boredom: A Review of the Literature.” Experimental Brain Research 136:2451–62.

- Rust, Roland T., and Bruce Cooil. 1994. “Reliability Measures for Qualitative Data: Theory and Implications.” Journal of Marketing Research 31 (1):1–14.

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” The American Psychologist 55 (1):68–78. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

- Schmidt, Susanne, and Martin Eisend. 2015. “Advertising Repetition: A Meta-Analysis on Effective Frequency in Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 44 (4):415–28.

- Smallwood, Jonathan, and Jonathan W. Schooler. 2015. “The Science of Mind Wandering: Navigating the Stream of Consciousness.” Annual Review of Psychology 56 (1):487–518.

- Sutter-Brandenberger, Claudia, Gerda Hagenauer, and Tina Hascher. 2018. “Students’ Self-Determined Motivation and Negative Emotions.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 55:166–75.

- Sveningsson, Stefan, and Mats Alvesson. 2003. “Managing Managerial Identities: Organizational Fragmentation, Discourse, and Identity Struggle.” Human Relations 56:1163–93.

- Tam, Katy, Wijnand van Tilburg, Christian Chan, Eric Igou, and Hakwan Lau. 2021. “Attention Drifting in and out: The Boredom Feedback Model.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 25 (3):251–72. doi:10.1177/10888683211010297

- Tze, Virginia, Lia Daniels, and Robert Klassen. 2016. “Evaluating the Relationship between Boredom and Academic Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Psychology Review 28:119–44.

- Vafeas, Mario. 2021. “Client-Agency Briefing: Using Paradox Theory to Overcome Challenges Associated with Client Resource Deployment.” Journal of Advertising 50 (3):299–308.

- Van Tilburg, Wijnand A. P., and Eric R. Igou. 2012. “On Boredom: Lack of Challenge and Meaning as Distinct Boredom Experiences.” Motivation and Emotion 36 (2):181–94.

- Wigfield, Allan, and Jacquelynne S. Eccles. 2000. “Expectancy-Value Theory of Achievement Motivation.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (1):68–81. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1015