Abstract

Companies increasingly employ environmental compensation claims in their advertisements. This practice, however, has been criticized as being a form of greenwashing. In two studies, we examined associations between the exposure to abstract and concrete compensation claims, consumers’ perceived greenwashing, environmental boycotting and buycotting intentions, and brand evaluation as well as purchase intentions. Further, we investigated the moderating role of consumers’ environmental knowledge. In Study 1, findings from a two-wave panel survey (NW2 = 511) indicated that exposure to abstract compensation claims was positively related to perceived greenwashing, whereas exposure to concrete compensation claims was not. Environmental knowledge did not influence perceptions of greenwashing in either claim. Using experimental data, Study 2 (N = 423) showed that concrete compensation claims can also lead to perceived greenwashing but to a lesser extent than abstract ones. Furthermore, environmental knowledge helped consumers detect greenwashing in both claims. In both studies, perceived greenwashing positively predicted consumers’ intention to join environmental boycotts but not buycotts. In addition, Study 2 showed that perceived greenwashing was negatively associated with purchase intentions. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

In recent years, especially companies that sell inherently environmentally harmful products or services have been using green advertising to promote green corporate images or portray products and services as environmentally friendly (e.g., Leonidou et al. Citation2011). These companies increasingly use a new, promising green advertising strategy by employing environmental compensation claims (e.g., Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010). Compensation claims suggest that the harmful environmental impact of the advertised product or service can be neutralized with an environmentally friendly measure. For instance, airlines advertise that they engage in environmental projects such as planting trees, recycling, or supporting sustainability research with the goal to offset consumers’ carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that originated from their flights (e.g., Air New Zealand Citation2019). On the one hand, they advertise abstract compensation claims that promote their services by offering compensation measures that are temporally distant and therefore not observable or verifiable by consumers such as tree planting. On the other hand, they make use of concrete compensation claims that promote their services by offering immediate and observable compensation measures, such as recycling measures on board of airplanes (Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023).

While these claims may be “a tool for speeding up climate action,” there is a risk that they are at the same time a “meaningless promotional tool” because of their possibly misleading character (Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010, 51). Due to the high complexity of environmental compensation processes, these claims “are potentially open to exploitation” (Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010, 50). For compensation advertising claims, no “uniform, accepted standard” exists which leads to different scientific approaches to define and measure environmental compensations and their effectiveness due to its complexity (Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010, 52). While some companies make sure that the offered compensation measures are communicated transparently regarding their effectivity and feasibility, some others omit important information that is necessary to evaluate their overall environmental impact (Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993).

To date, little is known about consumers’ perceptions of these claims, as research that investigates whether individuals can critically elaborate on both types of the newly conceptualized compensation claims is limited (but see Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023). Consumers could perceive environmental compensation claims as misleading or unsubstantiated and thus may perceive greenwashing in these ads—that is, consumers’ perception of companies’ involvement in an “act of disseminating disinformation to consumers regarding the environmental practices of a company or the environmental benefits of a product or service” (Baum Citation2012, 423). However, based on the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986), especially individuals that are low in environmental knowledge might have difficulty critically questioning the real impact of promoted compensation measures and therefore fail to detect greenwashing.

Thus, this article aims to contribute to a better understanding of consumers’ ability to perceive greenwashing in compensation claims and the associations between perceptions of greenwashing, brand evaluation, and purchase intention. In addition, this study examines two forms of political consumerism: first, consumers’ intentions to join environmental boycotts—defined as deliberately refraining from purchasing to harm a company or punish it with lost sales; second, consumers’ intentions to join environmental buycotts—understood as increasing purchase behavior to reward a company with an increase in sales (e.g., Copeland and Boulianne Citation2022; Hoffmann et al. Citation2018). Thereby, this study sheds light on circumstances that motivate consumers to use their voice to “communicate their views to decision-makers” (Copeland and Boulianne Citation2022, 3).

The current work contributes to the field of green advertising research on two important fronts. First, we contribute to the literature on the effects of greenwashing (e.g., Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018) by, for the first time, employing a multimethod design to test individuals’ reactions to abstract and concrete compensation claims as well as the moderating role of environmental knowledge in evaluating these claims (e.g., Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023; Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015). Thereby, we go beyond prior single experimental and cross-sectional studies (e.g., Chen and Chang Citation2013). By employing a panel study design in Study 1, we gain insights into individuals’ perceptions of content received in their everyday information environment, which can be an important complement to more controlled but also more artificial experimental settings (Taris Citation2011). Further, by using an experiment in Study 2, we validate our findings from Study 1 and add causal evidence.

Second, so far, advertising research has been focused on individuals’ personal consumption choices such as consumers’ purchase intentions or their engagement in word of mouth (e.g., Chen, Lin, and Chang Citation2014). However, little attention has been paid to consequences of perceived greenwashing within the public sphere that could influence society as a whole by affecting public policy or public decision making. Thus, for the first time, we looked beyond typical brand outcomes and investigated consequences of perceived greenwashing for boycotting and buycotting intentions.

Environmental Compensation Claims

Due to its uncertainty in implementation, experts highlight the risk of abuse of environmental compensation (e.g., Persson Citation2013). As a result of this uncertainty, the communication of environmental compensation measures is characterized by ambiguity. Specifically, calculations of environmental compensation often lack transparency: Information about how much environmental harm the promoted product or service causes and how much of this harm is compensated is often missing (Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010). It is likely that important information that consumers would need to assess the “truthfulness or reasonableness” of a compensation claim is omitted (Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993, 31). Thus, a compensation claim can be categorized as a so-called omission greenwashing claim, that is, a claim that stresses the environmental friendliness of a service or product while withholding environmentally unfriendly aspects (e.g., Kangun, Carlson, and Grove Citation1991).

Compensation claims—conceptualized as subtypes of omission claims—extend the existing typology of green(washing) claims suggested by Kangun, Carlson, and Grove (Citation1991). Conceptually, they can be distinguished from vague claims that are described as overly ambiguous and refrain from giving a clear reason or measure why the advertised company, product, or service is environmentally friendly. Further, they can be distinguished from false claims presenting incorrect information or outright lies (e.g., Kangun, Carlson, and Grove Citation1991). In fact, compensation claims neither refrain from giving a reason why the company, product, or service is environmentally friendly nor present an outright lie. However, they do omit important information that is essential for consumers to assess the true benefits of the environmental offer (e.g., Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023).

Use of Compensation Claims

Previous content analyses of green advertising have shown that companies offering industry goods with an environmentally harmful image especially rely on green advertising to counteract or divert accusations of harming the environment (e.g., Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993; Leonidou et al. Citation2011). Recently, compensation claims seem to be a promising advertising strategy for these companies. For instance, airlines use compensation claims on a regular basis. Although the majority of airlines’ compensation claims were found to be trustworthy, 44% of them were considered misleading by lacking information, “credibility and transparency,” and “disclosure, clarity, and scientific accuracy” (Guix, Ollé, and Font Citation2022, 2).

The growing popularity of compensation messages in CO2-heavy sectors possibly can be explained by the fact that these companies increasingly face public criticism due to their offers of inherently environmentally unfriendly products or services (e.g., The Guardian Citation2020). As a reaction, airlines (e.g., HiFly Citation2019), energy and petrochemicals companies (e.g., Shell Citation2021), multinational coffee (e.g., Nespresso Citation2020), fast food (e.g., McDonalds Citation2019), fast fashion (e.g., H&M Group Citation2021), and tourism companies promote compensatory measures (e.g., Dhanda Citation2014). However, instead of substantially contributing to climate protection, they are often used for “marketing purposes only” (Dhanda Citation2014, 1179). Nevertheless, despite green advertising, it seems that due to public debates and social movements like “Fridays for Future” the environmental harm of environmentally controversial industries becomes increasingly salient for consumers (Special Eurobarometer Citation2020).

Abstract and Concrete Compensation Claims

Drawing on advertising practice, we can distinguish between abstract compensation claims and concrete compensation claims (Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023). When looking at prior research, the terms abstract and concrete are used by some scholars to denote message concreteness, that is, “the degree of detail and specificity about objects, actions, outcomes, and situational context” within messages (Mackenzie Citation1986, 178). However, we use these terms to describe the tangibleness of the offered compensation measures in compensation ads.

When companies use abstract compensation claims, they offer future environmental compensation for the environmental impact of the products or services. This compensation measure is performed not immediately but at a later point in time when consumers are unable to directly observe and verify the act of environmental counterbalance. Abstract compensation claims are evident in the case of various airlines that claim to support tree planting, environmental projects, or research to neutralize the environmental harm they cause with their services (e.g., Air New Zealand Citation2019). Other companies offering energy, petrochemicals, and coffee also promote future compensation measures, such as projects for climate protection or planting fruit trees (e.g., H&M Group Citation2021; Shell Citation2021; Nespresso Citation2020).

In contrast, concrete compensation claims include immediate compensation of the environmental impact that the offered product or service is causing. Further, the compensation measure can be directly experienced and “seen” by consumers while using a product or service. One of the most prominent examples for concrete compensation claims is airline advertising suggesting that airlines take environmental action by reducing, recycling, or upcycling plastic on their airplanes (e.g., HiFly Citation2019). Thus, they suggest an observable and verifiable environmental trade-off for the flight that is clearly visible to consumers. Similarly, advertising of multinational fast food or fast fashion companies promotes new packaging materials or straws that are made from cardboard instead of plastic (e.g., H&M Group Citation2021; McDonalds Citation2019), all of it directly observable for consumers.

Perceptions of Environmental Compensation Claims

Previous studies have shown that consumers were able to detect false claims as greenwashing but have difficulties detecting vague claims or executional claims including nature imagery to enhance a company’s green image (e.g., Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015; Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). Until now, despite one single study by Neureiter and Matthes (Citation2023), there is no further evidence regarding perceptions of greenwashing in compensation claims. By conducting a single forced-exposure experiment, authors showed that consumers without environmental knowledge were able to perceive greenwashing in abstract compensation claims but had difficulties recognizing greenwashing in concrete compensation claims. However, they focused on consumers’ emotions as well as brand-relevant variables as consequences of perceived greenwashing and neglected other variables that might be relevant not only for companies but also for society as a whole. Thus, the present study contributes not only to robust and valid findings in the context of perceptions of greenwashing and compensation claims but also gives new insights into associations between greenwashing perceptions and political consumerism. Further, results from previous studies investigating false and vague claims as well as executional greenwashing cannot be generalized to compensation claims, because, for the latter, consumers’ information processing could be different due to compensatory balancing heuristics. In more detail, consumers’ compensatory green beliefs, that are beliefs that environmental harmful behavior can be neutralized by pro-environmental behavior, could be triggered by compensation claims (e.g., MacCutcheon, Holmgren, and Haga Citation2020). This could lead to “inaccurate estimates of the environmental impact” of green products or services increasing consumers’ acceptance of these claims without scrutinizing them in detail (MacCutcheon, Holmgren, and Haga Citation2020, 1).

Within the context of compensation claims, prior studies have focused on investigating voluntary compensation offers, also known as voluntary carbon offsetting (VCO). For instance, studies have suggested that public perceptions of VCO programs are characterized by confusion as well as low credibility and transparency possibly leading to perceptions of greenwashing (e.g., Babakhani, Ritchie, and Dolnicar Citation2017). Further, Zhang and colleagues (Citation2019a) showed that high source credibility of VCO messages had a positive effect on consumers’ purchase intentions of VCO. However, due to the conceptual differentiation between VCO and compensation claims—which are not a consumer’s voluntary decision to additionally purchase but are already included in the ad offer—perceptions of greenwashing of compensation claims and their consequences need to be investigated separately.

Theoretical Framework

As an overall framework to investigate how compensation claims are perceived by consumers, we draw on the ELM (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). According to the ELM, individuals can process messages via a peripheral route which is marked by low levels of processing effort and a high sensitivity to cues. When motivations or abilities to process information are high, they switch to the central route of information processing. In this mode, attitudes are formed by attention to and critical scrutiny of “the issue-relevant arguments contained in a message” (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986, 128).

Previous research has shown that for consumers to detect greenwashing it is necessary that they process green claims via the central route, including heightened attention and critical evaluation (e.g., Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). The likability of taking the central route increases with motivation or ability to process the information in the ads (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986).

Perceptions of Schema Incongruency in Compensation Claims

Schema Incongruity Processing Theory (Mandler Citation1982) states that consumers are likely to use ad schema based on their prior knowledge and experience to evaluate new ads (e.g., Goodstein Citation1993). Further, ads that are incongruent with consumers’ expectations may lead to a more analytical processing of information than ads that are congruent with consumers’ advertising expectations (Fiske and Taylor Citation1991). Thus, a perceived mismatch of the product category and the ad may result in consumers’ irritation and subsequently in motivation to classify advertising in existing schema for quicker information processing the next time. This motivation could lead to higher attention toward these ads and more extensive information processing (e.g., Homer and Kahle Citation1986) via the central route of the ELM (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986).

This theoretical premise is supported by a sizable body of research. For instance, Goodstein (Citation1993) showed that incongruent ads led to longer viewing times and more thoughts about these ads. The author concluded that the motivation to process an ad is influenced by the fit of the ad with the product category in consumers’ minds. In addition, other studies have shown that incongruent ads result in more questions and consumer confusion but also more correct recall of the ads’ arguments (e.g., Homer and Kahle Citation1986).

In the context of green compensation claims, environmentally controversial companies that promote a green image by offering pro-environmental measures may be perceived by consumers as “unexpected,” “out of context,” and as a misfit with existing mental structures in their minds (Homer and Kahle Citation1986, 52). As a result, the perceived mismatch may lead to higher attention toward the ad and more extensive information processing due to accommodation processes of incongruent information (Homer and Kahle Citation1986). Because cognitive effort is an integral factor in detecting greenwashing, consumers are likely to react with skepticism to these contradictions and thus perceive greenwashing (Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). Hence, we derive our first hypothesis:

H1: The exposure to green advertising including (a) abstract compensation claims and (b) concrete compensation claims positively affects perceptions of greenwashing.

Information Processing of Concrete and Abstract Compensation Claims

However, drawing on the Construal Level Theory (CLT; Trope and Liberman Citation2010), perceptions of abstract and concrete compensation claims may differ regarding the strength of the argument made in the claims and thus also regarding perceived greenwashing. Generally, according to the CLT, individuals make use of concrete construals to portray near events and abstract construals to refer to distant events (Trope and Liberman Citation2010). Further, individuals’ perceptions of abstract representations of events go along with perceptions that these events are more distant and thus less tangible. As a consequence, argument strength of abstract claims in comparison to concrete claims is decreased due to consumers’ perceptions of intangibility and psychological distance.

Because the ELM states that the success of persuasion messages processed via the central route depends on argument strength, abstract claims might be less acceptable to consumers. In line with this, previous research has shown that persuasion effects decreased when spatial distance was perceived as large (e.g., Latané et al. Citation1995).

Applied to the context of green advertising, this suggests that persuasion effects might be stronger for concrete compensation claims, including environmental compensation measures with low psychological distance and thus high argument strength, than for abstract compensation claims referring to future environmental compensation measures with high psychological distance and thus low argument strength. In fact, Zhao and colleagues (Citation2015) showed that messages dealing with distant events happening in the future (perceived as abstract) are less persuasive than messages revolving around immediate events that are happening now or in the very near future (perceived as concrete). Moreover, Zhang and colleagues (Citation2019b) found that messages about the local (concrete) impact of VCO are perceived as more credible and thus are more persuasive than messages about the global (abstract) impact of VCO. Following this logic, we assume that concrete compensation claims are more persuasive and distract consumers more from perceptions of greenwashing than abstract compensation claims. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2: The exposure to abstract compensation claims positively affects perceptions of greenwashing to a greater extent than exposure to concrete compensation claims.

The Moderating Role of Environmental Knowledge

According to the ELM, individuals high in knowledge are better able to critically process information of messages than individuals low in environmental knowledge. In the context of green advertising, individuals’ environmental knowledge—knowledge about natural processes, how human behaviors affect them, and which behaviors are effective in mitigating environmental damage (Frick, Kaiser, and Wilson Citation2004)—might be an important resource to evaluate compensation claims and allow for a more critical processing thereof.

So far, research on green advertising has found that environmental knowledge helps individuals to discern between valid and invalid green claims: Those high in environmental knowledge are better equipped to identify false green claims as well as concrete compensation claims as greenwashing (e.g., Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023; Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018) and are less affected by executional greenwashing (Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015). In the context of VCO in the travel sector, Denton and colleagues (Citation2020) showed that consumers’ environmental knowledge about carbon offsetting was negatively associated with consumers’ attitudes toward companies’ VCO programs and intentions to participate in such programs.

Thus, we expect that those high in environmental knowledge will have increased perceptions of greenwashing as opposed to those low in environmental knowledge when seeing compensation claims. Based on the ELM, this effect is due to increased scrutiny of the exact arguments in the message, which do not substantiate a positive environmental impact or camouflage important information that would be necessary to correctly evaluate the true benefit of the compensation offer. Hence, we hypothesize:

H3: The positive effect of exposure to (a) abstract compensation claims and (b) concrete compensation claims on perceived greenwashing is strengthened by environmental knowledge.

Consumers’ Behavioral Intentions As a Response to Perceived Greenwashing

When encountering deceptive green claims, consumers may feel that advertisers want to coerce them to consumption while not fully informing them (e.g., Delmas and Burbano Citation2011). Based on the Theory of Psychological Reactance (Brehm Citation1966), as a consequence, feelings of psychological reactance could arise, because consumers may feel that their freedom of consumption choice is threatened by companies’ misleading claims. Consequently, consumers might want to restore their freedom by showing reactance, which can motivate behavioral intentions than run counter to those intended by advertising.

Psychological reactance triggered by perceptions of greenwashing could influence consumers to take action and send a collective signal against greenwashing practices. In fact, due to environmental reasons, consumers tend to increasingly engage in behavior that is driven by environmental, social, and ethical considerations, such as political consumerism. Political consumerism describes consumers’ behavior of purposefully refraining from certain purchases (i.e., boycotts) or deliberately purchasing certain products or services for political reasons (i.e., buycotts; e.g., Copeland and Boulianne Citation2022). Such decisions by consumers can have serious consequences for marketers. For instance, according to earlier studies, the companies that are subject to a boycott may suffer financial losses (e.g., Pruitt and Friedman Citation1986) due to prolonged restraint on the side of consumers.

Consumers who join environmental boycotts not only signal the company that it has “engaged in conduct that is strikingly wrong” (Klein, Smith, and John Citation2004, 96) but also fight for an environmentally friendly way of consumption by refraining from consuming goods from companies engaging in environmentally harmful behavior or greenwashing. Thus, we hypothesize:

H4: Perceptions of greenwashing positively affect intentions of environmental boycotting.

While boycotts are characterized by a high-cost situation for consumers due to consumption restrictions, buycotts can be seen as a low-cost situation in which consumers can support companies that are environmentally friendly (e.g., Hutter and Hoffmann Citation2013). It is assumed that the concepts of buycotts differ from boycotts with regard to consumers’ evaluation of them (Hoffmann et al. Citation2018). Previous research has shown that some environmentally concerned consumers are not willing to join environmental boycotts due to individual restrictions in their consumption behavior. Instead, they tend to prefer engaging in buycotts, expecting a win-win situation (e.g., Hutter and Hoffmann Citation2013).

Derived from previous research, perceived greenwashing could influence intentions to buycott in two different ways. On the one hand, we assume that perceptions of greenwashing are associated with lower intentions to join environmental buycotts. Due to high exposure to greenwashing attempts, consumers may not be motivated to support any supposedly green company because of defensive stereotyping (Darke and Ritchie Citation2007). On the other hand, there is also a possibility that consumers are motivated by greenwashing perceptions to support other substantial green companies where they can be sure that their messages are not misleading. Due to this conflicting evidence, we pose a research question:

RQ1: How do perceptions of greenwashing affect changes in intentions of environmental buycotting?

Study 1

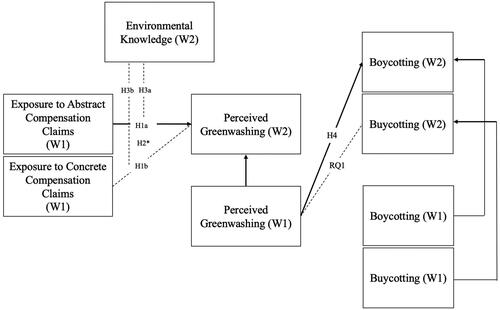

Study 1 was conducted to gain insights into the effects of compensation claims in the context of individuals’ day-to-day media consumption. The conceptual model of Study 1 is shown in .

Figure 1. Conceptual model of Study 1. Black colored paths visualize a significant positive association between variables. Dashed paths indicate a nonsignificant relation between variables. *H2 stands for the comparison between abstract and concrete compensation claims in terms of perceived greenwashing showing that abstract compensation claims are associated more strongly with perceived greenwashing.

Method

Since panel studies are methodologically superior to cross-sectional studies (e.g., Kearney Citation2017; Taris Citation2011), we used a two-wave panel study to test our hypotheses. Based on previous work (e.g., Lazarsfeld and Fiske Citation1938), we measured the same variables at two points of time (wave 1 [W1] and wave 2 [W2]). In so doing, we were able to address the temporal order of cause (independent variables measured at W1) and effect (dependent variables measured at W2), which is one criterium for causality (e.g., Taris Citation2011).

The study received ethical approval of the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna, Austria (approval ID: 20200724_018). The data came from a larger two-wave panel study on unrelated topics in Austria. The sample was recruited based on nationally representative quotas for age (range: 18 to 69, MW1 = 45.95, SDW1 = 14.32) and gender (53.0% female). Participants came from diverse educational backgrounds: 34.3% had lower education (i.e., compulsory schooling), 44.4% had intermediate education (i.e., high school degrees), and 21.3% indicated high education (i.e., university degree). The first wave (W1) was conducted between August 10 and August 21, 2020 (N = 993). We followed the recommendation of Leiner (Citation2019) and excluded participants who took less than 10 minutes to complete the 25-minute survey (n = 81). The resulting NW1 = 912 participants were invited to take part in the second wave (W2), which was conducted between October 19 and October 27, 2020. NW2 = 511 participants completed both waves. For differences between dropouts and participants who finished both waves, see Table A1 in Supplemental Online Appendix A under the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/b6yun/).

Table 1. Results of Study 1.

Measures

Unless indicated differently, predictors were measured in W1, while dependent variables were measured in W1 and W2. Unless otherwise indicated, we measured all items on 7-point scales.

To measure perceived exposure to abstract compensation claims (MW1 = 3.90, SDW1 = 1.56, αW1 = .87), individuals were asked (on a scale from Very rarely to Very often) if they had seen advertising messages within the past two months online, on social media, on TV, or in print that promoted environmental measures which, for example, “are taking place, but which consumers cannot see directly.” Exposure to concrete compensation claims (MW1 = 3.41, SDW1 = 1.49, αW1 = .89) was assessed asking participants if they had seen advertising messages that, for example, “call for environmental measures that can be directly experienced by consumers.” A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed the two-dimensionality of the two constructs (see Figure A1 in Supplemental Online Appendix A).

Perceived greenwashing (MW1 = 4.58, SDW1 = 1.58, αW1 = .80; MW2 = 4.69, SDW2 = 1.52, αW2 = .79) was assessed with two items adapted from Chen and Chang (Citation2013), asking individuals about how often they had seen certain messages online, on social media, on TV, or in print that, for example, “portray products or services as being more useful to the environment than they are.”

Boycotting (MW1 = 5.24, SDW1 = 1.68, αW1 = .94; MW2 = 5.05, SDW2 = 1.73, αW2 = .94) and buycotting intentions (MW1 = 4.86, SDW1 = 1.61, αW1 = .93; MW2 = 4.83, SDW2 = 1.59, αW2 = .94) were measured using three-item scales for each concept taken from Hoffmann and colleagues (Citation2018; e.g., “I could imagine taking part in a consumption boycott of a company that destroys the environment”; “I could imagine following a public appeal to support a company by buying their products if they actively take a stand for environmentalism”).

Environmental knowledge (range: 0 to 5, MW2 = 3.51, SDW2 = 1.27) was measured in W2 as the sum of correct answers to knowledge questions about environmental consumption and climate-related phenomena derived from Geiger and colleagues (Citation2019). Because we asked general knowledge questions, we considered environmental knowledge as a stable concept which should remain mostly unchanged within the timeframe of two months.

In addition, we controlled for age, gender (1 = female), education (1 = intermediate education and high education; with reference as lower education), and environmental concern. We measured individuals’ level of environmental concern (MW2 = 4.42, SDW2 = 1.38, αW2 = .79) using a three-item index (Schuhwerk and Lefkoff-Hagius Citation1995) at W2 (e.g., “I am willing to make great sacrifices to protect the environment”). Because we had no theoretical grounds on which to assume that environmental concern would change between two waves, we considered environmental concern as a stable concept. For all item wordings, see Table A2 in Supplemental Online Appendix A. For descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations, see Table A3 in Supplemental Online Appendix A.

Table 2. Results of Study 2 (Hypotheses 1, 3, 4, and 5).

Table 3. Results of Study 2 (Hypothesis 2).

Data Analysis

We tested our hypotheses using autoregressive panel models, that is, regressing the dependent variable in W2 on the independent variable in W1 while controlling for the dependent variable in W1. In panel models, the cause is measured in W1, preceding the effect in W2, which is an important criterion for causality. In addition, by controlling for the dependent variable in Wave 1 while predicting Wave 2, autoregressive models address individuals’ stability in attitudes and behaviors.

To retain the information from individuals that completed W1 only, we employed the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method (Enders Citation2001). To account for nonnormality, a robust maximum likelihood estimator was used. All paths were estimated using the lavaan package (Rosseel Citation2012) in R. For model requirements, see Figures A2 through A5 in Supplemental Online Appendix A. The data set of Study 1 is available under OSF.

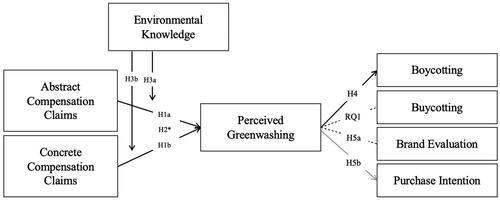

Figure 2. Conceptual model of Study 2. Black colored paths depict a significant positive association between variables. Gray paths indicate a significant negative association between variables. Dashed paths visualize a nonsignificant relation between variables. *H2 stands for the comparison between abstract and concrete compensation claims regarding perceived greenwashing indicating that abstract compensation claims lead to stronger perceptions of greenwashing.

Results

Results revealed that while exposure to abstract compensation claims in W1 predicted perceived greenwashing in W2 (b = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p = .010), exposure to concrete compensation claims in W1 was not related to perceived greenwashing in W2 (b = −0.05, SE = 0.04, p = .304). Thus, while hypothesis 1(a) was confirmed, hypothesis 1(b) was not supported.

Furthermore, we did a nested model comparison between model 2 in which the coefficients of the claims were constrained to be equal and the original model 1 without constraints. Results indicated that hypothesis 2 was supported: Model 1 theorizing different effects fit the data significantly better than model 2 (Δχ2(1) = 5.27, p = .022).

Regarding hypothesis 3, results indicated neither a significant moderating influence of environmental knowledge on the relationship between exposure to abstract compensation claims at W1 and perceived greenwashing at W2 (b = −0.02, SE = 0.04, p = .558), nor exposure to concrete compensation claims at W1 and perceived greenwashing at W2 (b = 0.02, SE = 0.04, p = .641). Thus, hypothesis 3 is not confirmed by our results. In addition, results showed a significant simple effect of environmental knowledge on perceived greenwashing at W2 (b = 0.17, SE = 0.04, p < .001) conditional on the average exposure to abstract and concrete compensation claims at W1.

Further, hypothesis 4 was supported: Perceived greenwashing measured at W1 predicted intentions of environmental boycotting at W2 (b = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = .036). In terms of intentions of environmental buycotting at W2 (research question 1), the analysis revealed a nonsignificant effect of perceived greenwashing at W1 (b = 0.01, SE = 0.04, p = .830) and a positive significant effect of exposure to concrete compensation claims at W1 (b = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p = .022). In addition, results showed a positive effect of environmental knowledge on boycotting intentions (b = 0.18, SE = 0.05, p < .001). For detailed results of Study 1, see .

In addition, we analyzed our path model in a reversed way with the available data (boycotting and buycotting behaviors at W1 and perceived greenwashing at W2). Results indicated that neither boycotting intentions at W1 (b = 0.05, SE = 0.05, p = .299) nor buycotting intentions at W1 (b = −0.02, SE = 0.05, p = .714) were associated with perceptions of greenwashing at W2. This points to the fact that reversed causality might not be an issue in our path model.

Finally, we redid our analysis following a cross-sectional logic where we treated perceived greenwashing (W2) as a predictor of boycotting and buycotting intentions (W2). The results were robust (see Table A4 in Supplemental Online Appendix A), yet a mediation analysis showed a nonsignificant result (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = .067). However, to analyze a mediation model with longitudinal data, at least three observations are necessary (Collins, Graham, and Flaherty Citation1998).

Discussion

In Study 1, we found that abstract compensation claims, but not concrete compensation claims, positively predicted greenwashing perceptions. A possible explanation for this finding might be that for concrete compensation claims psychological distance appears to be smaller than for abstract compensation claims (Trope and Liberman Citation2010). Hence, concrete compensation claims may seem closer, more approachable, and therefore also more realizable for consumers than abstract ones. This finding is in line with the ELM, showing that increased argument strength due to the realizability of environmental measures makes concrete claims more likely to be persuasive. Thus, consumers’ suspicion of greenwashing might be lower for concrete compensation claims. This result is in line with prior studies indicating that persuasion effects are stronger for concrete, tangible (green) messages than for abstract, intangible ones (e.g., Zhao et al. Citation2015; Zhang et al. Citation2019b).

Furthermore, findings showed that environmental knowledge per se heightened consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing when consumers’ exposure to abstract and concrete compensation claims was average. However, the associations of both abstract and concrete compensation claims with perceived greenwashing occurred independently of environmental knowledge. This is neither consistent with the ELM nor with previous research indicating that environmental knowledge increases consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing (e.g., Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015). This might be explained by our measurement: We measured exposure to abstract and concrete compensation claims in a broad way, referring to ads by all kinds of products and services. It could be that broad environmental knowledge helps detect greenwashing for some product or service categories but not for others, depending on how environmentally harmful a product or service category is. For product categories that are not as clearly environmentally harmful, in-depth environmental knowledge about the specific product or service category might be needed.

Further, findings showed that perceived greenwashing positively predicted intentions to boycott environmentally unfriendly companies. Although in Study 1 we could not test for causality, the findings represent tentative evidence that perceptions of greenwashing promote a proactive demand to “act against selfish interest for the good of others” (Klein, Smith, and John Citation2004, 93). Consequently, consumers might accept the individual cost of refraining from otherwise desirable goods to signal their disapproval. In addition, environmental knowledge was found to positively predict intentions to environmentally boycott. This is in line with previous research showing that consumers who are environmentally knowledgeable are more motivated to get environmentally active (e.g., Michalos et al. Citation2009).

From previous research, we know that consumers evaluate boycotts differently than buycotts (Hoffmann et al. Citation2018). Findings confirmed this assumption by showing that, unlike boycotting intentions, buycotting intentions were positively predicted by concrete compensation claims but not by perceived greenwashing. It seems that individuals perceived concrete compensation claims as benefiting the environment, which is associated with the need to support companies that promote such measures through buycotts.

Limitations

Several limitations of Study 1 need to be acknowledged. First, Study 1 does not give insight into the precise nature of environmental compensation ads consumers have seen. Because we asked participants only about the frequency of exposure to abstract and concrete compensation claims, we missed information on the explicit content of the ads (i.e., nature of compensation measures) as well as context (i.e., advertising companies). Thus, findings must be interpreted with caution as consumers’ ad perceptions could differ between industries and compensation measures.

Second, it is important to note that our measures in Study 1 were perceptual. Although self-reported data collected in panel studies are associated with actual exposure to media content (Goldman and Warren Citation2020, 7), we still relied on the retrospective memory recall of participants when asking about their exposure to compensation claims. Thus, it is important to bear in mind the possible memory bias in these responses.

Third, regarding our measures of exposure to compensation claims, Study 1 lacked the option Never. However, we captured individuals’ overall trends in perceived exposure, which still gives us the possibility to test the hypothesized relationships.

Finally, while panel data offer advantages over cross-sectional data in their possibility to account for temporal order and individuals’ stability in perceptions and behaviors, they are limited in proving causality (Kearney Citation2017). Although we ruled out the possibility of reverse causality in the relationship between perceived greenwashing and boycotting and buycotting intentions by testing a cross-lagged model, to fully exclude the possibility of spurious relationships an experimental study is needed.

Study 2

Study 2 is designed to validate the findings of Study 1 by using an experimental design. In Study 2, we did not rely on participants’ self-reports and thereby counteracted memory biases, as we made sure that participants were exposed to abstract and concrete compensation claims in a controlled setting. In addition, by showing participants our stimuli, we knew exactly which environmental compensation ads they had seen (i.e., what products or services, wording of the claims). Finally, by following the experimental logic, we could draw causal conclusions.

In addition, Study 2 aims to shed light on advertising effectiveness. Besides boycotting and buycotting intentions, perceptions of greenwashing might have an influence on consumers’ brand evaluation and purchase intentions of the advertised products or services. Drawing on the Theory of Psychological Reactance (Brehm Citation1966), perceptions of greenwashing could backfire on evaluations of companies and brands. In fact, previous research has shown that perceptions of greenwashing lead to decreased trust in companies (Chen and Chang Citation2013) and negative ad evaluation and brand evaluation (e.g., Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). Hence, psychological reactance is likely to lead to a boomerang effect, negatively affecting consumers’ cognitive evaluations of the brand (Miller Citation1976, 232) and their intentions to purchase from the respective brands (e.g., Chen, Lin, and Chang Citation2014). Thus, we derive an additional hypothesis:

H5: Perceived greenwashing is negatively associated with (a) brand evaluation and (b) purchase intentions.

For the conceptual model of Study 2, see .

Method

Prior to conducting the experiment, the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna, Austria, ethically approved our study (ID: 20220723_033). With the help of a professional polling company, we recruited a representative quota-based sample of Austrians based on age, gender, and education. Between August 26 and September 6, 2022, we employed a 3 × 1 between-subjects multimessage design (greenwashing claim: concrete compensation versus abstract compensation versus control condition). Shortly after data collection began (but prior to data analysis), we preregistered Study 2 under the OSF. Accordingly, we excluded participants who took less than 2.89 minutes (i.e., one-third of the median of duration time) for the 10-minute experiment (n = 124). In addition, in our preregistration, we indicated that participants would be excluded if they failed three out of three attention checks. For data quality reasons, we decided to be stricter and excluded participants who failed more than one of three attention checks (n = 12). However, we additionally ran our model as it was described in the preregistration (N = 433), and findings remained robust. Finally, we excluded one participant with a diverse gender due to statistical variance problems.

Our final sample consisted of N = 423 participants, Mage = 45.28, SDage = 14.27, range: 18 to 69; 50.8% female; 50.6% low education (i.e., no education completed or lower secondary education); 30.7% intermediate education (i.e., high school graduate); 18.7% high education (i.e., college degree).

Stimulus Material

As compensation claims are predominantly used by companies selling environmentally inherently harmful services, such as airlines (e.g., Guix, Ollé, and Font Citation2022), we used airline ads as stimuli for this study. We employed a multimessage design showing participants Twitter ads from three lesser-known airlines (HiFly, s7airlines, SprintAir) in each condition (abstract compensation versus concrete compensation versus control) in random order. We used Twitter as a platform, because at the point of data collection Twitter had high advertising revenue (Statista Citation2022). The stimulus material was taken from a prior experimental study on greenwashing (Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023) to allow for replication and ensure comparability across studies.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the conditions. In the abstract compensation condition (n = 144), they saw three ads including claims about future compensation measures that were not directly observable or verifiable by consumers, such as investing money in environmental research, undertaking environmental projects, or planting trees. In the concrete compensation condition (n = 140), participants saw three airline ads claiming that the airlines engage in immediate compensation measures that could be directly experienced by consumers, for instance, recycling and upcycling, or reducing plastic on airplanes. In the control condition (n = 139), participants viewed three ads with claims that addressed holidays, relaxation, and comfort. While the claims varied across the conditions, we kept the design of the ads as well as the length of the text constant (see Figure A6 in Supplemental Online Appendix A).

Manipulation and Randomization Check

For a manipulation check, we asked participants if they perceived the claims as abstract or concrete. We used the six items that we used in Study 1 to measure exposure to abstract and concrete compensation claims. A CFA revealed two dimensions: abstract compensation claims (three items; M = 3.90, SD = 1.81, α = .82) and concrete compensation claims (three items; M = 3.04, SD = 1.65, α = .84; see Figure A7 in Supplemental Online Appendix A). Further, we checked if participants perceived the content of the ads correctly by asking them with which topics the ads they had seen had dealt. Analyses showed satisfactory results for both checks (see Table A5 in Supplemental Online Appendix A); thus, the manipulation was deemed successful. In addition, we did a randomization check (see Table A6 in Supplemental Online Appendix A). Because the randomization check for education showed significant differences between the conditions, we statistically controlled for education in our analysis.

Measures

Unless otherwise indicated, all items were measured on 7-point scales.

As mentioned, each participant saw three ads. After exposure to each ad, each participant responded to three perceived greenwashing items derived from Chen and Chang (Citation2013). Two of these items were also used in Study 1, and one item was added for Study 2 to extend the existing scale. Thus, for each participant, we had nine items assessing perceived greenwashing (M = 4.22, SD = 1.35, α = .88).

For boycotting and buycotting intentions, we used the same three items for each construct as in Study 1 based on Hoffmann and colleagues (Citation2018) and adjusted it to airlines (M = 4.55, SD = 2.05, α = .97; M = 4.35, SD = 1.81, α = .95). As outlined in the preregistration, we measured boycotting and buycotting intentions also with an alternative measure where we adjusted the items to each of the three airline brands separately. Findings indicated a positive effect of perceived greenwashing on both boycotting and buycotting intentions (b = 0.36, SE = 0.08, p < .001; b = 0.28, SE = 0.08, p < .001). However, our initial measure is more suited in validating findings of Study, 1 as the measurement we used in Study 1 did not address brands separately.

Because participants saw ads from three brands, we assessed brand evaluation for three brands separately with three items inspired by Stevenson and colleagues (Citation2000) on a semantic differential scale. We asked participants to rate the three airlines regarding attractiveness, likability, and interest. Thus, each participant responded to nine items. Afterward, we built an overall index across brands (M = 3.59, SD = 1.30, α = .95).

We measured purchase intentions derived from Schmuck, Matthes, Naderer, and Beaufort (Citation2018) with one item per airline asking participants to indicate if they would book a flight with the respective airline in the future. Overall, each participant responded to three items, one item for each of the three brands. Afterward, we built an overall index across brands (M = 3.17, SD = 1.48, α = .92).

We measured environmental knowledge (range: 0 to 5, M = 3.41, SD = 1.22) as the sum of correct answers to the same five single-choice items used in Study 1 based on Geiger and colleagues (Citation2019).

Finally, we measured our controls—age, gender, education, and environmental concern (M = 4.31, SD = 1.43, α = .84)—with the same items as in Study 1. In addition, we assessed flying frequency as a control variable asking participants on a 5-point scale ranging from Less than once a year to More often than once a month how often they fly with airlines on average (COVID-19 lockdown times excluded; M = 1.58, SD = 0.83). For descriptives and Pearson correlations of Study 2, see Table A7 in Supplemental Online Appendix A.

Data Analysis

We ran a moderated mediation analysis in R using the lavaan package (Rosseel Citation2012). We specified all paths between our variables in one model, which was estimated using bootstrapping technique with 5,000 samples. To test hypotheses 1, 3, 4, and 5, we used the control condition as a reference group and the concrete compensation condition as well as the abstract compensation condition as our independent variables (both dummy-coded). To test hypothesis 2, we used the abstract compensation condition as a reference group and the concrete compensation condition and the control condition as our independent variables (both dummy-coded). In both models, we inserted perceived greenwashing as a mediator and environmental knowledge as a moderator. As controls, we added age, gender (1 = female), education (1 = intermediate education and low education; with reference as higher education), environmental concern, and flying frequency.

The data set of Study 2 is available under the OSF.

Results

Results showed that abstract compensation claims (b = 0.98, SE = 0.15, p < .001) as well as concrete compensation claims (b = 0.52, SE = 0.15, p = .001) positively influenced perceived greenwashing. Thus, hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b) were supported.

Further, by using the abstract compensation condition as a reference group, analyses indicated that abstract compensation claims led to more perceived greenwashing than concrete compensation claims (b = −0.46, SE = 0.15, p = .002). Hence, hypothesis 2 was confirmed.

In addition to a simple effect of environmental knowledge on perceived greenwashing that is conditional on the control condition (predictors were dummy coded; b = −0.24, SE = 0.10, p = .020), we found interaction effects of environmental knowledge with abstract compensation claims (b = 0.41, SE = 0.13, p = .001) and concrete compensation claims (b = 0.43, SE = 0.13, p = .001) on perceived greenwashing (see Figure A8 in Supplemental Online Appendix A). In addition, a Johnson–Neyman analysis suggested that, on average, already low environmental knowledge (≥ 1.62 correct answers out of 5) empowers individuals to perceive greenwashing in abstract compensation claims. However, in concrete compensation claims, only very high environmental knowledge—that exceeds our measured environmental knowledge—contributes to perceived greenwashing (≥ 5.08 correct answers out of 5). Therefore, hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b) are supported. For Johnson–Neyman plots, see Figure A9 and Figure A10 in Supplemental Online Appendix A.

Moreover, results showed that perceived greenwashing positively predicted intentions of environmentally boycotting (b = 0.26, SE = 0.08, p = .001), confirming hypothesis 4, but not of environmentally buycotting (b = 0.004, SE = 0.07, p = .954).

Regarding hypothesis 5(a), we found that perceived greenwashing was not related to brand evaluation (b = −0.12, SE = 0.06, p = .056). In addition, we found a positive effect of concrete compensation claims on brand evaluation (b = 0.51, SE = 0.16, p = .001). However, regarding hypothesis 5(b), results clearly confirmed our assumption: Perceived greenwashing was negatively associated with purchase intentions (b = −0.20, SE = 0.063, p = .001). Again, we found a positive effect of concrete compensation claims on purchase intentions (b = 0.69, SE = 0.17, p < .001). For detailed results of Study 2, see and .

In addition, as a post hoc analysis, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. Results indicated that for the brand HiFly, the effect of the abstract compensation claim on perceived greenwashing was weaker as compared to the other brands (see Supplemental Online Appendix B under the OSF: , , ). Nevertheless, the overall pattern of effects was consistent across the different brands: The order did not change for any of the brands, and a brand pattern was visible.

Discussion

Study 2 demonstrated that abstract and concrete compensation claims by airlines both increased consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing. This result may be explained by the fact that consumers consider airlines as inherently environmentally unfriendly, and thus schema incongruency is perceived immediately. Indeed, in the past few years, the awareness among consumers that airlines are polluting the environment has grown due to environmental discourses such as “flight shame” and increased media attention to the phenomenon (e.g., The Guardian Citation2020). Thus, it seems that green airline advertising per se is incongruent with consumers’ expectations (Goodstein Citation1993), leading to consumers’ irritation, higher attention toward the ad, information processing via the central route of the ELM, and thus perceptions of greenwashing (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986).

Although both compensation claims of airlines led to perceived greenwashing, concrete claims did so to a lesser extent than abstract ones. In line with the Theory of Psychological Distance (Trope and Liberman Citation2010), consumers might perceive concrete compensation measures as less psychologically distant than abstract measures. This seems to heighten the ads’ persuasive effectiveness, possibly suppressing perceptions of greenwashing. This finding is in line with related prior research showing that information about the concrete impact of environmental measures is more persuasive than information about the abstract impact of environmental measures (e.g., Zhang et al. Citation2019b).

Further, consumers’ environmental knowledge helped perceiving greenwashing in both green airline claims. While for abstract compensation claims little environmental knowledge was needed to detect greenwashing, for concrete compensation claims high environmental knowledge was required. We thus conclude that consumers have more difficulties perceiving concrete compensation claims as greenwashing than abstract ones, at least in obvious environmentally unfriendly companies such as airlines.

Moreover, concrete compensation claims of airlines were associated with a more positive airline evaluation and increased purchase intentions. However, if greenwashing was perceived, the tide was turning: Intentions to environmentally boycott airlines and decreased purchase intentions occurred as a consequence. Interestingly, in contrast to prior research (e.g., Neureiter and Matthes Citation2023; Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018), brand evaluation was not affected by perceptions of greenwashing. This might be due to a habituation effect, because many airlines today use supposedly green advertising, often in a misleading way. So, consumers may almost expect greenwashing in supposedly green airline advertising. Although they may not evaluate the brand more negatively, they may refrain from supporting it and decide to purchase elsewhere. Finally, perceived greenwashing was not associated with buycotting intentions. It could be that intentions to buycott are induced by pleasant emotions connected to companies rather than unpleasant ones that are likely to be evoked by perceptions of greenwashing. Thus, perceived greenwashing might be irrelevant for buycotting intentions (e.g., Hoffmann et al. Citation2018).

Limitations

Study 2 has limitations in terms of generalizability, because we concentrated on airlines only. Thus, the results may not be applicable to other products or services that are not as obviously environmentally harmful as airlines are. Future comparative research is needed to account for effects of green ads on perceived greenwashing that vary in the environmental harm of advertised products or services.

General Discussion

This is the first study to combine panel data with experimental data to investigate consumers’ exposure to compensation claims and perceptions of greenwashing. Traditionally, effects of green advertising and perceived greenwashing on consumers’ perceptions are examined with cross-sectional or experimental methods only (e.g., Chen and Chang Citation2013; Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018), lacking multimethod approaches. However, companies’ usage of environmental compensation claims is a rather new phenomenon where advertising practice is currently developing strongly. To capture this trend, we first conducted a panel study that allowed conclusions about the perceived exposure of consumers to environmental compensation claims in their everyday lives. Second, to address limitations of Study 1 and to draw causal conclusions, we conducted an experiment.

By corroborating findings of Study 1 with data from Study 2, we contributed to existing research in several ways. First, this study extends existing research by empirically testing two underresearched subtypes of omission claims (e.g., Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993). We offered causal evidence that environmental compensation claims could be perceived by consumers as greenwashing; however, this depends on the claim type: abstract or concrete. Study 1 and Study 2 demonstrated that abstract compensation claims were perceived more easily as greenwashing than concrete ones. This shows that abstract and concrete compensation claims are two idiosyncratic concepts that consumers most likely process differently based on perceptions of psychological distance (Trope and Liberman Citation2010). Thereby we contribute to a more differentiated conceptualization of greenwashed advertising by extending the typology of Kangun, Carlson, and Grove (Citation1991) with two more recently occurring subtypes of omission claims.

Moreover, this is the first study, to our knowledge, that examined the association between perceived greenwashing and consumers’ environmental boycotting and buycotting intentions. According to findings of Study 1 and Study 2, it seems that perceived greenwashing motivated consumers to express their dissatisfaction and speak out publicly against companies that did not perform in line with their environmental values (e.g., Copeland and Boulianne Citation2022). This form of political consumerism could influence public policy and market practices, potentially leading to a more environmentally responsible society. Further, both studies showed that buycotting intentions are unconnected to perceptions of greenwashing. This could be due to negative underlying emotions toward companies accompanied by perceived greenwashing that trigger intentions to punish companies but not to support them. In addition, Study 2 indicated that perceptions of greenwashing were negatively associated with purchase intentions pointing to negative consequences for companies using greenwashed ads.

However, there are also two divergent findings between Study 1 and Study 2 that might be explained by differences in the research context and in the methodological design. First, while in Study 1 we found that concrete compensation claims were not associated with perceptions of greenwashing, in Study 2 they increased perceptions of greenwashing. In Study 1, we investigated participants’ perceptions of compensation claims from companies offering various products or services. Given this diversity, individuals were confronted with a higher level of ambiguity around whether a concrete compensation claim offers an effective way to improve the environmental impact or whether it constitutes greenwashing. In contrast, in Study 2, we showed participants compensation claims from airlines and thus from companies that offer obviously inherently environmentally unfriendly services. It could be that participants’ information processing was more extensive for the ads embedded in Study 2 than the ads captured in Study 1 due to increased perceptions of incongruency between the supposedly green ads and the advertising companies. Moreover, methodologically, in Study 1, we relied on participants’ retrospective memory recall, which is prone to distortion, when asking about their exposure to compensation claims. In contrast, in Study 2, we directly exposed participants to compensation ads. Thus, participants were not likely to be distracted by a complex media environment as they would normally have been in their daily lives. Besides, we also showed them prototypes of concrete and abstract compensation claims. Under these circumstances, it could have been easier for consumers to perceive greenwashing.

Second, while in Study 1 we found no significant interaction effect of environmental knowledge and compensation claims, in Study 2 environmental knowledge heightened perceived greenwashing in both compensation claims. It is possible that participants with broad environmental knowledge—as we measured it in both studies—were aware of the environmental harmfulness of airlines in Study 2. However, in Study 1 environmental knowledge was possibly too broad to point participants to less obvious incongruencies in ads of companies that are not that obviously environmentally harmful. In addition, while in Study 1 participants had to think back to the ads they had seen in past months, in Study 2 participants could directly apply their environmental knowledge to scrutinize the ads that we showed them. Finally, in Study 1 participants might only have gotten a very brief impression of the ads and even though they remembered them, they might not have had the chance to process the ads in depth to perceive greenwashing. Yet in Study 2 they had as much time as they wanted to process the ads thoroughly in light of their environmental knowledge.

To rule out differences that might occurred because of the sample, we conducted additional analyses comparing the samples (see Table A8 and Figure A11 in Supplemental Online Appendix A under the OSF). Results showed that in Study 1 participants were more highly educated than were participants in Study 2 (see Figure A12 in Supplemental Online Appendix A). However, despite this, participants were not better able to perceive greenwashing in Study 1 than participants were in Study 2. Thus, we conclude that differences in the samples do not explain our divergent findings.

To sum it up, it seems that whether environmental knowledge helps consumers recognize greenwashing in compensation claims depends on two factors. First, the environmental harmfulness of the promoted products or services in the ads might play a role. Second, whether consumers can directly apply their environmental knowledge at the moment of exposure to compensation claims (i.e., if there is enough time) might be of importance. If both factors apply, it seems that environmental knowledge can help consumers to detect greenwashing in compensation claims. However, further research is needed to confirm this.

Limitations and Future Research

Further limitations need to be mentioned. Our studies were both carried out in Austria, an European country, where consumers are generally characterized by high environmental awareness (Special Eurobarometer Citation2021). For other countries, the results could look different. Hence, a cross-national study is needed.

Moreover, we used self-reported measures of boycotting and buycotting intentions as well as purchase intentions instead of actual behavioral measures. While self-reported measures of consumer responses are common in advertising research, future research should measure actual boycotting, buycotting, and purchase behaviors to prevent social desirability biases.

Finally, we have not directly measured the processes underlying the observed effects. Future studies should take into account other possible explanations why compensation claims could heighten consumers’ attention and information processing such as consumers’ perceived novelty of compensation claims or their interest in them.

Practical Implications

There are important implications for advertising practice. Generally, to prevent consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing in advertising, green claims should not refer to minor environmentally friendly measures that are marginal in relation to the actual environmental damage of the product or service. Moreover, they should include a detailed description of how the advertised company, product, or service benefits the environment (i.e., specification with numbers).

To make an argument for the significance of the promoted environmental measures for protecting the environment, compensation claims should include information on how the offered environmental measures will be performed and the amount of carbon emissions they are compensating in relation to the carbon emissions produced by purchasing the advertised product or service (e.g., Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010, 54). In other words, it must be clear for consumers on what grounds the compensation calculation is based on and how much the compensation measure makes the company, product, or service “greener.” That means that complex background information has to be communicated in an understandable way. For instance, ads should include quality parameters of the environmental compensation measures and transparent compensation calculations to help consumers to make an educated consumption decision.

Further, it seems that environmental knowledge does not help consumers recognize greenwashing in all contexts. Thus, there is a definite need for company-independent tools that help consumers to form a comprehensive picture of the real benefits of environmental compensation measures for various products and services. For instance, Quick Response (QR) codes including information about environmental compensation measures, or standardized and verified ecolabels that show consumers how big the benefit of the environmental compensation measures actually is, could prevent consumers from falling for greenwashing.

Conclusion

By using a multimethod approach, we showed that consumers are equipped to perceive greenwashing in environmental compensation claims, especially when the advertising company is obviously inherently environmentally unfriendly. While they seem to have a clear understanding that abstract compensation claims are greenwashing, concrete compensation claims are not so easily detected. However, for companies where the environmental harm is obvious, such as airlines, environmental knowledge helps consumers to perceive greenwashing in both claims. As a consequence, consumers’ intentions to join environmental boycotts can increase and purchase intentions can decrease. To conclude, companies—especially inherently environmentally harmful ones—should pay greater attention to substantiating their green claims to avoid consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing and the negative consequences that can follow.

Supplemental Online Appendix B

Download MS Word (123.2 KB)Supplemental Online Appendix A

Download MS Word (9.4 MB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ariadne Neureiter

Ariadne Neureiter (MA, MSc, University of Vienna) is a doctoral candidate, Advertising and Media Psychology Research Group, Department of Communication, University of Vienna.

Marlis Stubenvoll

Marlis Stubenvoll (PhD, University of Vienna) is a postdoctoral researcher, Department of Media and Communications, University of Klagenfurt.

Jörg Matthes

Jörg Matthes (PhD, University of Zurich) is deputy head of department, Department of Communication, University of Vienna.

References

- Air New Zealand. 2019. Air New Zealand’s carbon offset programme. www.airnewzealand.co.nz/sustainability-customer-carbon-offset

- Babakhani, Nazila, Brent W. Ritchie, and Sara Dolnicar. 2017. “Improving Carbon Offsetting Appeals in Online Airplane Ticket Purchasing: Testing New Messages, and Using New Test Methods.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25 (7): 955–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1257013

- Baum, Lauren. 2012. “It’s Not Easy Being Green … Or Is It? A Content Analysis of Environmental Claims in Magazine Advertisements from the United States and United Kingdom.” Environmental Communication 6 (4): 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2012.724022

- Brehm, Jack W. 1966. A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Carlson, Les, Stephen J. Grove, and Norman Kangun. 1993. “A Content Analysis of Environmental Advertising Claims: A Matrix Method Approach.” Journal of Advertising 22 (3): 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1993.10673409

- Chen, Yu-Shan, and Ching H. Chang. 2013. “Greenwash and Green Trust: The Mediation Effects of Green Consumer Confusion and Green Perceived Risk.” Journal of Business Ethics 114 (3): 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

- Chen, Yu-Shan, Chang-Liang Lin, and Ching-Hsun Chang. 2014. “The Influence of Greenwash on Green Word-of-Mouth (Green WOM): The Mediation Effects of Green Perceived Quality and Green Satisfaction.” Quality & Quantity 48 (5): 2411–2415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-013-9898-1

- Collins, Linda M., John J. Graham, and Brian P. Flaherty. 1998. “An Alternative Framework for Defining Mediation.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 33 (2): 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3302_5

- Copeland, Lauren, and Shelley Boulianne. 2022. “Political Consumerism. A Meta-Analysis.” International Political Science Review 43 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120905048

- Darke, Peter R., and Robin J. B. Ritchie. 2007. “The Defensive Consumer: Advertising Deception, Defensive Processing, and Distrust.” Journal of Marketing Research 44 (1): 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.1.114

- Delmas, Magali A., and Vanessa C. Burbano. 2011. “The Drivers of Greenwashing.” California Management Review 54 (1): 64–87. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

- Denton, Gregory, Oscar Hengxuan Chi, and Dogan Gursoy. 2020. “An Examination of the Gap between Carbon Offsetting Attitudes and Behaviors: Role of Knowledge, Credibility and Trust.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 90:102608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102608

- Dhanda, K. Kanwalroop. 2014. “The Role of Carbon Offsets in Achieving Carbon Neutrality. An Exploratory Study of Hotels and Resorts.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 26 (8): 1179–1199. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2013-0115

- Enders, Craig K. 2001. “The Performance of the Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimator in Multiple Regression Models with Missing Data.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 61 (5): 713–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164401615001

- Fiske, Susan T., and Shelley E. Taylor. 1991. Social Cognition. 2nd ed. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

- Frick, Jaqueline, Florian G. Kaiser, and Mark Wilson. 2004. “Environmental Knowledge and Conservation Behavior: Exploring Prevalence and Structure in a Representative Sample.” Personality and Individual Differences 37 (8): 1597–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.02.015

- Geiger, Sonja Maria, Mattis Geiger, and Oliver Wilhelm. 2019. “Environment-Specific vs. General Knowledge and Their Role in Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Frontiers in Psychology 10:718. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00718

- Goldman, Seth K., and Stephen M. Warren. 2020. “Debating How to Measure Media Exposure in Surveys.” In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Persuasion, edited by Elizabeth Suhay, Bernard Grofman, and Alexander H. Trechsel, 998–1015. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190860806.013.28

- Goodstein, Ronald C. 1993. “Category-Based Applications and Extensions in Advertising: Motivating More Extensive Ad Processing.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (1): 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1086/209335

- Guix, Mireia, Claudia Ollé, and Xavier Font. 2022. “Trustworthy or Misleading Communication of Voluntary Carbon Offsets in the Aviation Industry.” Tourism Management 88:104430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104430

- H&M Group. 2021. 2020 in Numbers. https://hmgroup.com/sustainability/sustainability-reporting/#responsible-farming

- HiFly. 2019. New Campaign to End Plastic Pollution. http://www.hifly.aero/media-center/new-campaign-to-end-plastic-pollution/

- Hoffmann, Stefan, Ingo Balderjahn, Barbara Seegebarth, Robert Mai, and Mathias Peyer. 2018. “Under Which Conditions Are Consumers Ready to Boycott or Buycott? The Roles of Hedonism and Simplicity.” Ecological Economics 147: 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.01.004

- Homer, Pamela M., and Lynn R. Kahle. 1986. “A Social Adaptation Explanation of the Effects of Surrealism on Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 15 (2): 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1986.10673005

- Hutter, Katharina, and Stefan Hoffmann. 2013. “Carrotmob and anti-Consumption. Same Motives, But Different Willingness to Make Sacrifices?” Journal of Macromarketing 33 (3): 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146712470457

- Kangun, Norman, Les Carlson, and Stephen J. Grove. 1991. “Environmental Advertising Claims – a Preliminary Investigation.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 10 (2): 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569101000203

- Kearney, Michael W. 2017. “Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, edited by M. Allen, 1–6. Thousand Oaks: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411.n117

- Klein, Jill G., Craig N. Smith, and Andrew John. 2004. “Why We Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation.” Journal of Marketing 68 (3): 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.3.92.34770

- Latané, Bibb, James H. Liu, Andrzej Nowak, Michael Bonevento, and Long Zheng. 1995. “Distance Matters: Physical Space and Social Impact.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21 (8): 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295218002

- Lazarsfeld, Paul, and Marjorie Fiske. 1938. “The “Panel” as a New Tool for Measuring Opinion.” Public Opinion Quarterly 2 (4): 596–612. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2745105. https://doi.org/10.1086/265234

- Leiner, Dominik J. 2019. “Too Fast, Too Straight, Too Weird: Non-Reactive Indicators for Meaningless Data in Internet Surveys.” Survey Research Methods 13 (3): 229–248. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2019.v13i3.7403

- Leonidou, Leonidas C., Constantinos Leonidou, Dayananda Palihawadana, and Magnus Hultman. 2011. “Evaluating the Green Advertising Practices of International Firms: A Trend Analysis.” International Marketing Review 28 (1): 6–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331111107080

- Mandler, Georg. 1982. “The Structure of Value: Accounting for Taste.” In Affect and Cognition, edited by Margaret S. Clark and Susan T. Fiske, 3–36. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- McDonalds. 2019. New Packaging Across Europe. https://twitter.com/McDonaldsCorp/status/1194876380720308224

- MacCutcheon, Douglas, Mattias Holmgren, and Andreas Haga. 2020. “Assuming the Best: Individual Differences in Compensatory “Green” Beliefs Predict Susceptibility to the Negative Footprint Illusion.” Sustainability 12 (8): 3414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083414

- Mackenzie, Scott B. 1986. “The Role of Attention in Mediating the Effect of Advertising on Attribute Importance.” Journal of Consumer Research 13 (2): 174–195. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2489225. https://doi.org/10.1086/209059