Abstract

Objectives: A combination tablet of ibuprofen 800 mg and famotidine 26.6 mg given three times daily is effective for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis and decreases the risk of developing upper gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers. This analysis evaluated the gastroprotective efficacy and safety of the single-tablet combination of ibuprofen/famotidine compared with ibuprofen alone on the basis of age and the presence of one or more risk factors for development of upper GI ulcer. Methods: Pooled data from the 24-week, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 trials were used. Endoscopies were performed in patients aged 40–80 years. The proportion of patients who developed ≥1 upper GI ulcer during treatment with ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen alone stratified on the basis of age (<60 or ≥60 years) was evaluated. Further, analyses were performed on additional risk factors for ulcer development. Results: Gastroprotective efficacy of the combination was not affected by age. Pooled results demonstrated statistically significantly fewer upper GI (10.0 vs 19.5%, p < 0.0001), gastric (8.9 vs 16.8%, p = 0.0004), and duodenal ulcers (1.1 vs 5.4%, p < 0.0001) in patients <60 years treated with ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen alone compared with 12.9 vs 26.6% (p = 0.0002), 11.9 vs 23.4% (p = 0.0011), and 1.0 vs 4.5% (p = 0.0096), respectively, in patients ≥60 years. The ibuprofen/famotidine combination provided nearly 51 and 59% reduction in the risk of developing a GI ulcer in patients <60 years and ≥60 of age, respectively. Efficacy was maintained in the presence of additional risk factors, as well. Conclusions: These results indicate that the fixed-combination of ibuprofen/famotidine provides gastroprotection in those of older age, with or without additional risk factors for the development of upper GI ulcers, as compared with ibuprofen alone. US National Institutes of Health registry, http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00450658 and NCT00450216.

Introduction

Many older persons (≥60 years of age) develop chronic illnesses that may be associated with persistent pain [Citation1-4]. The inadequate treatment of persistent pain in older persons is associated with numerous adverse outcomes such as functional impairment, accidental falls (with or without injury), slow rehabilitation, decreased socialization, greater health care costs, and greater resource utilization. From 2010–2050, the US population of persons aged ≥65 years is projected to double [Citation5]. In the US, it is estimated that ∼100 million people have chronic pain [Citation6]. In comparison, current estimates of Americans affected with other common diseases are 29.1 million and 14 million for diabetes mellitus and cancer, respectively [Citation7,8]. However, some treatments for chronic pain may give rise to other risks in those of older age.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a commonly prescribed class for the treatment of pain within this age group, yet chronic use of NSAIDs is known to pose potential cardiovascular and gastrointestinal (GI) risk and may result in non-adherence to NSAID therapy [Citation1,4,9,10]. Older age is a major risk factor for these adverse experiences [Citation1,11,12], and in particular age ≥60 years [Citation1,4,9]. Previous studies have shown that a large proportion of elderly patients experienced GI nuisance adverse events associated with NSAIDs [Citation1,11-13]. Pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials demonstrated an age-dependent linear increase in endoscopically diagnosed ulcers in NSAID-treated patients compared with placebo-treated patients [Citation14]. These data are supported by several other studies that have demonstrated an increased risk of upper GI bleeding or perforation increases with increasing age [Citation12,15-17]. To circumvent potential GI events, use of gastroprotective agents in conjunction with NSAIDs has been widely recommended by a number of committees and associations [Citation18-25]. Important risk factors for GI complications include age >65 years, high-dose NSAID therapy, history of uncomplicated ulcer, and concurrent use of low-dose aspirin (LDA), or other anticoagulants (OAC) [Citation18].

A combination tablet that includes ibuprofen 800 mg and famotidine 26.6 mg for administration three-times daily (TID) has been approved by the US FDA for the relief of signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis and to decrease the risk of developing upper GI ulcers [Citation26]. The results of two 24-week double-blind trials (REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 [Registration Endoscopic Studies to Determine Ulcer Formation of HZT-501 Compared with Ibuprofen: Efficacy and Safety Studies]) demonstrated that the combination of single-tablet ibuprofen/famotidine reduced the risk of upper GI ulcers as compared with ibuprofen alone (frequencies of upper GI ulcers in REDUCE-1: 14.7 vs 29.1%, p = 0.0002 and REDUCE-2: 13.8 vs 22.6%, p = 0.030) [Citation27]. In prespecified pooled analysis of these trials, significantly fewer gastric (12.5 vs 20.7%) and duodenal ulcers (1.1 vs 5.1%) were observed with the combination of ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen alone (p <0.001 and p <0.05, respectively). In the current analysis, we sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the single-tablet combination of ibuprofen/famotidine compared with ibuprofen alone on the basis of age (<60 and ≥60 years) and the presence of ≥1 risk factor for the development of an upper GI ulcer (i.e. age 60 years, LDA use, other OAC use, or history of upper GI ulcer). The hypothesis was that famotidine would be equally efficacious in patients aged <60 years and in patients aged ≥60 years as well as in patients with and without 1 or more risk factors.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study design and primary efficacy and safety results of the Phase III, multicenter, REDUCE-1 (NCT00450658) and REDUCE-2 (NCT00450216) clinical studies conducted in the US from March 2008 to September 2008 and March 2007 to August 2008, respectively, have been reported previously [Citation27-29]. The REDUCE trials consisted of a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study designed to evaluate the efficacy, as measured by endoscopically diagnosed upper GI ulcers, and safety of the combination ibuprofen/famotidine tablet versus ibuprofen alone. Patients who completed the 24-week treatment period without developing an endoscopically diagnosed upper GI ulcer were eligible to enroll in an extension study [Citation29] or continue to be monitored for safety for an additional 4 weeks, for a total of 28 weeks of safety monitoring. The identical-appearing tablets of ibuprofen 800 mg/famotidine 26.6 mg tablet or ibuprofen 800 mg were self-administered orally, on a double-blind basis, TID, for up to 24 consecutive weeks. The protocols were approved by the applicable Institutional Review Boards and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided informed written consent before participating in any study procedure.

Patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with either the combination tablet or ibuprofen alone. Randomization in the REDUCE trials was stratified based on two risk factors for ulcer development: first, the concomitant use of LDA and/or OAC medication; and second, a history of an upper GI ulcer. Randomization has been described previously [Citation27].

Endoscopic examinations were performed during screening (baseline) and at weeks 8, 16, and 24, with a 4-day window prior to the clinic visit day. Patients were terminated early from the study if they developed an endoscopically diagnosed upper GI ulcer of unequivocal depth at least 3 mm in diameter. Patients who terminated the study early for other reasons underwent an endoscopic examination at a termination visit that was conducted as soon as possible after administration of the final dose of study medication.

Patients aged 40–80 years expected to require daily NSAID therapy for at least the next 6 months for chronic pain and/or inflammation attributable to osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic lower back pain, chronic regional pain syndrome, and chronic soft tissue pain were enrolled in the REDUCE trials. Complete exclusion criteria have been published [Citation27]. Briefly, patients with a history of complicated GI ulcer/bleeding/perforation/malignancy, acute renal failure, interstitial nephritis, myocardial infarction, unstable cardiac arrhythmias, stroke, or abnormal laboratory results were excluded. Patients were prohibited from taking any NSAID other than the study medication, with the exception of LDA, and any gastric acid sequestering agents for >3 days during any 2-week period of the treatment period.

Study outcomes and analysis

The primary objective was to evaluate the efficacy of ibuprofen/famotidine in reducing the proportion of patients who developed ≥1 endoscopically diagnosed upper GI ulcer during the 24-week treatment period, as compared with ibuprofen, in patients at risk for NSAID-induced ulcers [Citation27]. Secondary objectives included analysis of patients who developed gastric or duodenal ulcers during the 24-week treatment period. For these analyses, each objective was stratified on the basis of age (<60 and ≥60 years). A sensitivity analysis was performed based on the presence or absence of ≥1 risk factor for upper GI ulcer (age ≥60, history of ulcer, or use of LDA/OAC versus <60 with no risk factors).

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) were collected from all patients beginning at the time of administration of the first dose of study drug and continued through completion of the 4-week follow-up period. TEAEs of special interest for this analysis included events within the GI system, vascular system, investigations, blood and lymphatic systems, cardiac system, and metabolism and nutrition disorders systems organ classes. Detailed safety analyses have been reported previously [Citation29].

Enrollment of patients in the REDUCE trials was based on pilot data available in the published literature [Citation30] and the anticipated response rate to the ibuprofen/famotidine combination tablet. Details of the sample size have been published previously [Citation27]. Randomization was performed using a computer-generated randomization schedule from a central location, utilizing an interactive voice response system with blinded medication kit number allocation in a 2:1 ratio. All patients and study staff remained blinded to treatment until after the last patient visit. Subjects with a finding of gastric, duodenal, or both (upper GI) ulcer were compared between the 2 groups; and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of treatment differences were calculated. Relative risks were determined for each efficacy objective. p-values were calculated from a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by randomization strata.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were no appreciable differences between the REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 populations with respect to age, gender, or race (). In REDUCE-1, 534 patients were under 60 years of age and 278 were aged ≥60 years. In REDUCE-2, 391 patients were under 60 years of age and 179 were ≥60 years of age. A total of 1022 patients who received ibuprofen/famotidine were included in the safety population compared with 511 patients who received ibuprofen. In these pooled analyses the primary efficacy population was comprised of 627 patients who received the ibuprofen/famotidine combination tablet younger than 60 years of age and 303 patients ≥60 years of age. A total of 452 patients received ibuprofen, 298 of whom were younger than 60 years of age and 154 of whom were ≥60 years of age. Of the 627 patients <60 years of age who received ibuprofen/famotidine, 60 (9.6%) had history of LDA use and 36 (5.7%) had history of GI ulcer. Of the 303 patients ≥60 years of age who received ibuprofen/famotidine, 89 (29.4%) and 24 (7.9%) had history of LDA use and GI ulcer, respectively. Of the 298 patients <60 years of age who received ibuprofen, 27 (9.1%) and 14 (4.7%) had history of LDA use and GI ulcer, respectively. Of the 154 patients ≥60 years of age who received ibuprofen, 31 (20.1%) and 12 (7.8%) had history of LDA use and GI ulcer, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (primary population, n = 1382).

Efficacy

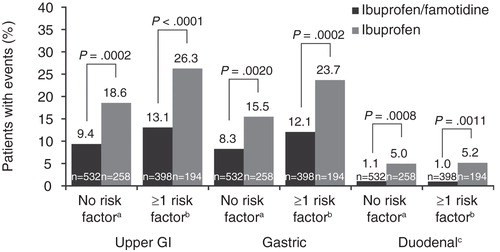

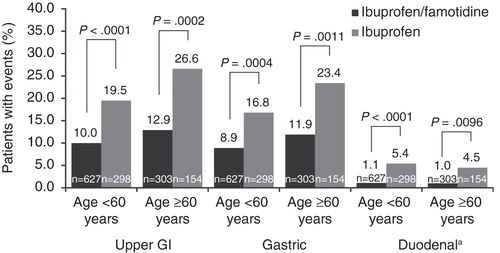

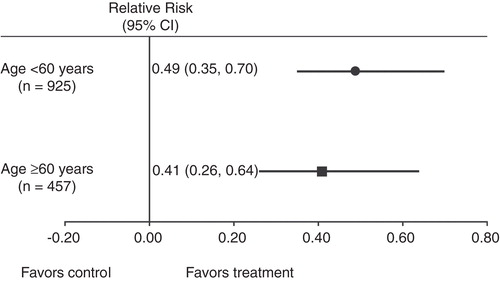

Among patients <60 years of age, the incidence of upper GI, gastric, and duodenal ulcers were significantly reduced compared with ibuprofen in each clinical study and confirmed by pooled results (p <0.001, p = 0.004, and p <0.001, respectively) (). Among those aged ≥60 years, pooled results demonstrated significantly reduced incidence of upper GI, gastric, and duodenal ulcers in the ibuprofen/famotidine group versus ibuprofen (p = 0.0002, p = 0.0011, p = 0.0096, respectively). Ten patients in the ibuprofen group (8 in the <60 and 2 in the ≥60 years of age group) had both a duodenal and gastric ulcer. Based on the pooled analyses, the relative risk of GI ulcer among patients <60 years of age (n = 925) was 0.494 (95% CI: 0.35, 0.70) in favor of ibuprofen/famotidine (). Likewise, the relative risk of GI ulcer among patients ≥60 years of age (n = 457) was 0.410 (95% CI: 0.26, 0.64) in favor of ibuprofen/famotidine. An analysis of the ratios of these relative risks indicated that there were no significant differences between those treated with ibuprofen/famotidine who were <60 or ≥60 years of age (these relative risks = 1.21, CI:0.68–2.13).

Figure 1. Incident rate of upper gastrointestinal ulcer development by age (primary population, n = 1382).

Figure 2. Relative risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer development in the overall pooled primary population (ibuprofen/famotidine + ibuprofen cohorts; n = 1382). The risk ratio was defined as the risk for ibuprofen/famotidine divided by the risk for ibuprofen.

Two other patient populations were compared for sensitivity analysis of the primary objective: first, those without any risk factor for upper GI ulcer (age <60 years, no concomitant LDA/OAC therapy, or no history of ulcer [ibuprofen/famotidine n = 532; ibuprofen n = 258]); and second, those with ≥1 risk factor for upper GI ulcer (age ≥60 years, concomitant LDA/OAC therapy, or history of ulcer [ibuprofen/famotidine n = 398; ibuprofen n = 194]) (). Among the 532 patients in the no-risk-factor subset who were administered ibuprofen/famotidine, 9.4, 8.3 and 1.1% developed upper GI, gastric, and duodenal ulcers, respectively. This translates to nearly a 50% decrease in the incidence of upper GI ulcers, a 46% reduction in gastric ulcers, and a nearly 5-fold reduction in duodenal ulcers compared with ibuprofen therapy alone. The number of upper GI events was reduced by >50% for patients with ≥1 risk factor who were treated with ibuprofen/famotidine compared with ibuprofen alone. Likewise, there was a 46% reduction in the number of gastric events for ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen and an 80% reduction in the number of duodenal events for ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen among patients with ≥1 risk factor.

Safety

Most TEAEs of special interest occurred within the GI disorders among both patients in both age groups (). Dyspepsia was reported by 8.1 and 7.9% of ibuprofen-treated patients younger than 60 years of age and ≥60 years of age, respectively. In comparison, dyspepsia was reported by 5.1 and 3.9% of ibuprofen/famotidine-treated patients in the same respective age groups, although results were not significantly different (p >0.05). Significantly fewer patients ≥60 years of age treated with ibuprofen/famotidine reported stomach discomfort compared with those treated with ibuprofen alone (p = 0.0203). However, results were not significantly different for those younger than 60 years of age (p = 0.0844). There were no differences in either age group with respect to epigastric discomfort due to the small number of total events (n = 3). Vascular disorders were the next most frequently occurring system organ class with TEAEs of special interest, the most common of which were increased blood pressure, increased eosinophil count, and irregular heartbeat. Only increased blood pressure occurred in more than 1% of patients in any treatment group (1.2% of patients ≥60 years of age treated with ibuprofen/famotidine), and results were not significantly different from the ibuprofen group (0.6%) (p = 0.4932). The overall incidence of cardiac-related TEAEs was low and not significantly different with respect to therapy or age group (p = 0.0674 and p = 0.7954 for ibuprofen/famotidine vs ibuprofen in patients aged <60 years and patients ≥60 years, respectively).

Table 2. Incidence of treatment emergent adverse events of special interest (safety population, n = 1533).

Discussion

These pooled results from REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 demonstrated a significantly lower incidence in upper GI, gastric, and duodenal ulcer in both age groups, indicating that the age did not affect the gastroprotective efficacy of the combination despite well-documented increasing risk with age () (all p < 0.05). The ibuprofen/famotidine combination tablet provided nearly 51 and 59% reduction in the risk of developing a GI ulcer in patients younger than 60 years and ≥60 of age, respectively (). Sensitivity analyses demonstrated that treatment with ibuprofen/famotidine resulted in significant decreases in the incidence of upper GI, gastric ulcers alone, and duodenal ulcers alone in patients younger than 60 years of age with no LDA/OAC use and no history of ulcer (all p < 0.05). Moreover, the combination of ibuprofen/famotidine significantly decreased the incidence of nuisance GI side effects (stomach and epigastric discomfort) in patients aged ≥60 years (all p < 0.05).

These results support the known benefits of adding gastric protection, including appropriate doses of famotidine, to high-dose NSAID therapy [Citation31]. These results are similar to previous studies that have documented the gastroprotective effects of high-dose H2-receptor antagonist therapy in this setting [Citation24,27-30,32]. For older patients requiring long-term ibuprofen therapy, early intervention with gastroprotective agents may offer the greatest benefit with respect to reducing the risk for ulcer development [Citation18]. Additionally, these results support findings from a previous analysis of the REDUCE trials which assessed the efficacy and safety of ibuprofen/famotidine in reducing the risk of upper GI ulcers in OA patients [Citation31]. In that study, 713 patients from the REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 trials were evaluated. Upper GI risk was significantly reduced by 55% (95% CI: 39.1–79.7%) in those aged ≥60 years and 65% in those using LDA with the ibuprofen/famotidine combination compared with ibuprofen alone. The study also found a significant reduction in gastric and duodenal ulcers in all groups. These results, in aggregate, have led to conclusions by Taha that the promise of H2-receptor antagonist therapy as an NSAID gastroprotective has now been fulfilled [Citation33].

Strengths of these analyses include the randomized design, the large sample size, the breadth of data available at study entry, and the availability of carefully selected end points. The two primary outcomes in the REDUCE trials were selected to address the endpoint of upper GI ulcers (gastric and/or duodenal) [Citation27]. However, there are potential limitations to these data. These results could be biased based on covariates that were not controlled for (i.e. gender, race). However, the groups did not differ substantially at baseline in major demographic variables. Generally, prevention studies can be affected by compliance differences in the study groups. Previous reports on these studies, however, indicate that adherence and exposure to the study treatments was good (∼80%) [Citation29], but compliance was not assessed for other therapies allowed in the study (LDA/OAC therapies). Moreover, results may not be generalizable to the entire population due to the exclusion/enrolment criteria of the study, such as excluding those with prior diseases that might increase the risk for upper GI ulcers. Finally, the clinical trials primarily enrolled patients < 65 years of age without a prior history of GI ulcer and the trials did not extend beyond 6 months.

Conclusions

This analysis of the pooled REDUCE-1 and REDUCE-2 study data provides further evidence supporting the use of the fixed-combination of ibuprofen/famotidine in older patients requiring long-term ibuprofen therapy, and that upper GI ulcer risk reduction was similar between older and younger patients and those with and without risk factors.

Declaration of interests

Tonya Goodman of Arbor Communications, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, provided medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript, funding for which was provided by Horizon. The design, study conduct, and financial support for these studies were provided by Horizon Pharma, Inc. Horizon participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the manuscript. AE Bello has been a consultant/advisor for Horizon Pharma USA, Inc. and has been on the speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Questcor, and UCB. JD Kent is an employee and stock shareholder of Horizon Pharma USA, Inc. RJ Holt is a consultant/advisor for Horizon Pharma USA, Inc. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Notes

References

- Lanas A, Ferrandez A. Inappropriate prevention of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal events among long-term users in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2007;24:121–31

- American Geriatric Society. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1331–46

- Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: Results of an internet-based survey. J Pain 2010;11:1230–9

- Lanas A, Boers M, Nuevo J. Gastrointestinal events in at-risk patients starting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for rheumatic diseases: the EVIDENCE study of European routine practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;74:675–81

- Vincent GK, Velkoff A. The next four decades: The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. United States Census report. Published May 2010. Available from https://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf. Last accessed on 30 April 2015

- Institute of Medicine Report from the Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America, A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education and Research. The National Academies Press. 2011. Available from http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13172&page=1. [Last accessed on 30 April 2015]

- American Diabetes Association. Available from http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Last accessed on 30 April 2015

- American Cancer Society, Prevalence of Cancer. Last revised May 20, 2014. Available from http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancerbasics/cancer-prevalence. Last accessed on 7 May 2015

- Goldstein JL, Hochberg MC, Fort JG, Zhang Y, Hwang C, Sostek M. Clinical trial: the incidence of NSAID-associated endoscopic gastric ulcers in patients treated with PN 400 (naproxen plus esomeprazole magnesium) vs. enteric-coated naproxen alone. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:401–13

- Lanas A, Polo-Tomas M, Roncales P, Gonzalez MA, Zapardiel J. Prescription of and adherence to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastroprotective agents in at-risk gastrointestinal patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:707–14

- Singh G. Recent considerations in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Am J Med 1998;105:31S–8S

- Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, Davies HW, Struthers BJ, Bittman RM, Geis GS. Misoprostal reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:241–9

- Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, Rothschild J, Debellis K, Seger AC, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003;289:1107–16

- Boers M, Tangelder MJD, van Ingen H, Fort JG, Goldstein JL. The rate of NSAID-induced endoscopic ulcers increases linearly but not exponentially with age: A pooled analysis of 12 randomised trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:417–18

- van Soest EM, Valkhoff VE, Mazzaglia G, Schade R, Molokhia M, Goldstein JL, et al. Suboptimal gastroprotective coverage of NSAID use and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers: An observational study using three European databases. Gut 2011;60:1650–9

- Seager JM, Hawkey CJ. ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Indigestion and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Br Med J 2001;323:1236

- Hernández-Diaz S, Rodriguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: An overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2093–9

- American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on osteoarthritis guidelines. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1905–15

- Wilcox CM, Allison J, Benzuly K, Borum M, Cryer B, Grosser T, et al. Consensus development conference on the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, including cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme inhibitors and aspirin. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1082–9

- Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, Antman EM, Chan FK, Furberg CD, et al. AACF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplateley therapy and NSAID use. Circulation 2008;118:1894–909

- Chan FK, Abraham NS, Scheiman JM, Laine L; First International Working Party on Gastrointestinal and Cardiovascular Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Anti-platelet Agents. Management of patients on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a clinical practice recommendation from the First International Working Party on Gastrointestinal and Cardiovascular Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Anti-platelet Agents. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2908–18

- Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:728–38

- Risser A, Donovan D, Heintzman J, Page T. NSAID prescribing precautions. Am Fam Phys 2009;80:1371–8

- Rostom A, Moayyedi P, Hunt R. Canadian consensus guidelines on long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy and the need for gastroprotection: benefits versus risks. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:481–96

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:465–74

- Duexis (package insert). Deerfield, IL: Horizon Pharma, Inc; 2012

- Schiff M, Peura D. HZT-501 (DUEXIS®); ibuprofen 800 mg/famotidine 26.6 mg) gastrointestinal protection in the treatment of the signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;6:25–35

- Laine L, Kivitz AJ, Bello AE, Grahn AY, Schiff MH, Taha AS. Double-blind randomized trials of single-tablet ibuprofen/high-dose famotidine vs. ibuprofen alone for reduction of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:379–86

- Bello A, Grahn AY, Ball J, Kent JD, Holt RJ. One-year safety of ibuprofen/famotidine fixed combination versus ibuprofen alone: Pooled analyses of two 24-week randomized double-blind trials and a follow-on extension. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:407–20

- Taha AS, Hudson N, Hawkey CJ, Swannell AJ, Trye PN, Cottrell J, et al. Famotidine for the prevention of gastric and duodenal ulcers caused by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1435–9

- Kent JD, Holt RJ, Jong D, Tidmarsh GF, Grahn AY, Ball J, Peura DA. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of intragastric pH and implications for famotidine dosing in the prophylaxis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced gastropathy - A proof of concept analysis. J Drug Assess 2014;3:20–7

- Bello AE, Kent JD, Grahn AY, Rice P, Holt RJ. Risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcers in patients with osteoarthritis receiving single-tablet ibuprofen/famotidine versus ibuprofen alone: pooled efficacy and safety analyses of two randomized, double-blind, comparison trials. Postgrad Med 2014;126:82–91

- Taha AS. The ibuprofen-famotidine combined pill – A promised fulfilled. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:421–2