?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study examines differential stability in attitudes toward homosexuality using panel data representative of the American adult population. While attitudes toward homosexuality have shifted considerably on the aggregate-level over the past few decades, this study shows that such attitudes are remarkably stable on the individual-level. Employing conditional change models, this study also provides a test of the aging-stability hypothesis with regard to attitudes toward homosexuality. That hypothesis is confirmed, as attitude stability is found to gradually increase with age. However, no other socio-demographic variables are found to have a consistent relationship with stability. The finding of an age-graded increase in stability suggests that attitudes toward homosexuality are formed predominantly early in life and that susceptibility to attitude change declines across the adult lifespan. This finding also supports a generational replacement explanation of recent changes in American public opinion on homosexuality as aging-stability translates into cohort effects on the aggregate-level.

Introduction

Change and continuity in attitudes toward homosexuality (ATH) have received considerable scientific attention in recent years (e.g., Andersen & Fetner, Citation2008; Daniels, Citation2019; Pampel, Citation2016; Schwadel & Garneau, Citation2014; Twenge, Sherman, & Wells, Citation2016). However, this research has predominantly relied on cross-sectional data, and the few studies that have employed panel data have been mainly concerned with the direction of change (see Armenia & Troia, Citation2017; Hooghe & Meeusen, Citation2012; Lee & Mutz, Citation2019; Smith, Citation2016). Consequently, we still know very little about how stable ATH are on the individual-level and the factors that condition stability. In order to address this blind spot in the literature, this paper examines the individual-level stability of two different indicators of ATH in the nationally representative General Social Survey Panel Studies (2006–2014).

Two principal research questions are addressed in this paper. First, how stable are ATH on the individual-level? In line with previous work in the political socialization literature, individual-level attitude stability is conceptualized here as differential stability (e.g., Alwin, Cohen, & Newcomb, Citation1991; Sears & Funk, Citation1999; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008). Differential stability refers to the degree to which the relative differences between individuals remain stable over time (Caspi & Roberts, Citation2001). As such, differential stability is statistically independent of mean-level change. Hence, while American public opinion on homosexuality has become markedly more liberal over the past few decades (Daniels, Citation2019; Pampel, Citation2016), this does not necessarily mean that ATH are characterized by low levels of differential stability. In fact, considering the dispositional nature of antigay bias (Eaves & Hatemi, Citation2008; Keiller, Citation2010; Nagoshi et al., Citation2008; Verweij et al., Citation2008) and the symbolic importance of homosexuality as a social issue in American politics, the expectation is that ATH are more stable than most other socio-political attitudes.

Second, do ATH vary in stability across the human lifespan? With respect to this question, a central assumption in the political socialization literature is that attitude stability increases with age (e.g., Grasso, Farrall, Gray, Hay, & Jennings, Citation2017; Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2005;Osborne et al., Citation2011), what has been referred to as the aging-stability hypothesis (Glenn, Citation1980). While the aging-stability hypothesis has been supported with regard to various partisan attitudes and racial attitudes in previous longitudinal studies (e.g., Alwin et al., Citation1991; Sears & Funk, Citation1999; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008), this hypothesis has never been tested by the means of panel data with regard to ATH. Yet, on the basis of age-period-cohort analysis, it has been suggested that “views about homosexuality [are] a rare exception to the age-stability hypothesis” (Andersen & Fetner, Citation2008, p. 324; also see Danigelis, Hardy, & Cutler, Citation2007; Schwadel & Garneau, Citation2014; Twenge et al., Citation2016). However, age differences in attitude stability can only indirectly be observed in cross-sectional data. Moreover, age-period-cohort analysis is subject to an identification problem that impedes clear-cut inference regarding change and continuity (Bell & Jones, Citation2013; Ekstam, Citation2021; Glenn, Citation2005). As such, the individual-level stability of ATH remains a largely unanswered question in the literature.

How stable are attitudes toward homosexuality?

Temporal stability on the individual-level varies greatly across attitudinal domains. Whereas some attitudes incline to change from day to day in a willy-nilly fashion, others remain essentially fixed even over long stretches of time (Alwin et al., Citation1991; Converse & Markus, Citation1979; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008). Although attitude stability can arise from environmental consistency (Lyons, Citation2017), the stability of an attitude is thought to be primarily dependent on its degree of crystallization: the extent to which the attitude is cognitively well-ordered and psychologically important to an individual (Henry & Sears, Citation2009; Jennings, Citation1990). Highly crystallized attitudes are associated with clear, univocal, and easily accessible cues in memory. These attitudes are therefore likely to be strongly held by the individual and to remain stable over time even in an inconsistent environment. Weakly crystallized attitudes, by contrast, are characterized by weak and ambiguous memory cues and are consequently likely to be unstable over time regardless of whether they are challenged or not (Converse, Citation1974; Krosnick & Schuman, Citation1988).

Attitudes that in theory are likely to reach high levels of crystallization are those regarding symbolic objects with a high political salience, as such attitudes typically are acquired early in life and consequently have a long time to accumulate affective mass (Glenn, Citation1980; Sears, Citation1983). Conversely, attitudes on topics that are rarely addressed or that are very complex are likely to reach lower levels of crystallization. For example, attitudes toward political parties tend to be considerably more stable than attitudes toward most domestic policy issues, presumably because of the more affective nature of party identification (Alwin et al., Citation1991; Sears & Funk, Citation1999; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008). Policy-related attitudes might nevertheless also reach high levels of crystallization insofar they regard topics that attract strong information flows since individuals in this case are likely to often engage with their attitudes and consequently attach more importance and emotion to them (Visser & Krosnick, Citation1998). In line with this reasoning, Sears and Valentino (Citation1997) found that attitudes on issues that were of central importance during a presidential election campaign increased in stability over the duration of a contemporary panel, whereas no such increase in stability was observed for attitudes on issues that were less salient during the campaign.

The extent to which an attitude is stable is in theory also dependent on whether or not it is rooted in some type of disposition (Sears & Funk, Citation1999). Stability is in particular likely to be high for attitudes that are strongly influenced by personality or that have a substantial genetic component to them. For example, racial attitudes and other group-centric attitudes tend to be among the more stable attitudes, probably due to being partly dispositional in nature (Converse & Markus, Citation1979; Kinder & Sanders, Citation1996; Sears, Citation1983). However, an attitude might also be stable because it is supported by an overarching belief-system or identity, such as a religion or a political ideology (Visser & Krosnick, Citation1998). In this latter case, the given attitude might be stable “by proxy” even if the attitude itself is not very crystallized (Westholm & Niemi, Citation1992). Accordingly, attitudes regarding political issues that are not easily placed along an ideological spectrum and that lack clear religious or moral connotations tend to be comparatively unstable even over short periods of time (Converse & Markus, Citation1979; Westholm & Niemi, Citation1992).

Very little is known about how stable ATH are on the individual-level in the American context since longitudinal studies on the subject are effectively missing.Footnote1 However, ATH meet most of the criteria for a crystallized and therefore stable attitude dimension in the contemporary American context. First, homosexuality has been a highly salient and symbolic political issue in the United States for several decades now. While public opinion on homosexuality has become increasingly liberal in recent time, questions such as same-sex marriages and same-sex adoptions remain highly polarizing political topics (Daniels, Citation2019; Sherkat, Powell-Williams, Maddox, & De Vries, Citation2011). Second, ATH are strongly related to personality dispositions such as Openness to Experience (Cullen, Wright, & Alessandri, Citation2002), Right-Wing Authoritarianism (Keiller, Citation2010; Nagoshi et al., Citation2008), and Social Dominance Orientation (Poteat, Espelage, & Green, Citation2007), dispositions that typically are highly stable during adulthood (Ludeke & Krueger, Citation2013; Roberts & DelVecchio, Citation2000). Some evidence further suggests that ATH are heavily influenced by genetics (Eaves & Hatemi, Citation2008; Verweij et al., Citation2008). Third, negative views on homosexuality are often rooted in religious convictions and may also tap into deeply held beliefs about sexuality and gender (Janssen & Scheepers, Citation2018). Conversely, nondiscriminatory attitudes may be based on a liberal worldview and general principles of tolerance. Either way, ATH are for most people likely part of an overarching belief-system that motivates stability. In sum, the expectation is that ATH are highly stable on the individual-level.

Do attitudes toward homosexuality vary in stability across the lifespan?

A central notion in the political socialization literature is that stability of most socio-political attitudes increases over an individual’s life course due to psychological maturation, what is often referred to as the aging-stability hypothesis (Glenn, Citation1980). Already the authors of The American Voter noted that attitude stability seems to increase with age (Campbell, Converse, Miller, & Stokes, Citation1960), and numerous studies have corroborated the aging-stability hypothesis ever since (e.g., Converse & Markus, Citation1979; Sears & Funk, Citation1999; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008).

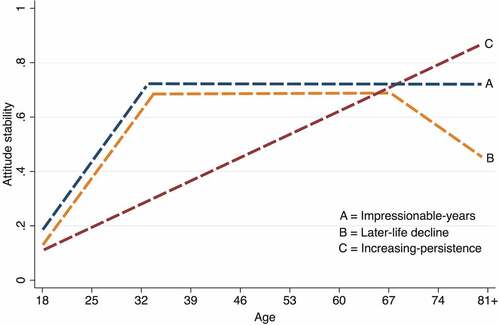

Three different versions of the aging-stability hypothesis exist in the literature, however. One version that enjoys strong empirical support across a wide range of different attitudes is based on the impressionable-years theory (e.g., Alwin et al., Citation1991; Alwin & Krosnick, Citation1991; Hatemi et al., Citation2009; Jennings & Stoker, Citation2004; Krosnick & Alwin, Citation1989; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008). According to this theory, the transition from adolescence to mature adulthood (roughly from age 18 to 30) constitutes a formative period in life when the individual is especially susceptible to environmental cues (Sears, Citation1975, Citation1983, Citation1993; Sears & Levy, Citation2003). This period of malleability is thought to reflect the trial-and-error process of (re)forming a social and political identity that the individual typically undertakes as a young adult, a process during which political orientations acquired earlier are likely to be reevaluated and possibly replaced by new ones (Sears, Citation1983). However, the political orientations that ultimately become crystallized toward the end of this “re-socialization” process will, according to this theory, persist throughout the remainder of life and structure further attitude formation along the way (Sears & Levy, Citation2003). Thus, what can be referred to as the impressionable-years model predicts that attitude stability increases rapidly during early adulthood to then level off and remain high during middle and late adulthood (see A in ).

A second developmental trajectory is proposed by what has been referred to as the later-life decline model (Henry & Sears, Citation2009).Footnote2 This model predicts an increase in attitude stability during early adulthood, for all the reasons just outlined, but also a decrease in stability during late adulthood (see B in ). This pattern of development has been found for racial attitudes (Sears, Citation1981) and symbolic racism (Henry & Sears, Citation2009). In experimental settings, older adults have also been found to be more easily persuaded than middle-aged adults to change their opinions on various topics (Tyler & Schuller, Citation1991; Visser & Krosnick, Citation1998). One possible psychological basis for this might be the deterioration of inhibitory abilities and other cognitive functions that normally occurs with old age (Henry & Sears, Citation2009; see also Gonsalkorale, Sherman, & Klauer, Citation2009; Krendl & Kensinger, Citation2016). However, this decrease in stability may also reflect that late adulthood, similarly to early adulthood, is a life-stage associated with a multitude of role transitions, most notably due to retirement, which may alter the individual’s worldview and thereby prompt attitude change (Visser & Krosnick, Citation1998).

A third, more straightforward developmental trajectory is proposed by the so-called increasing-persistence model (Alwin, Citation1994), which predicts that stability increases across the lifespan in an essentially linear fashion (see C in ). While the increasing-persistence model enjoys weaker empirical support than the previous two models, a lifelong gradual increase in stability has in some studies been found for American party identification and political ideology (Alwin & Krosnick, Citation1991; Converse, Citation1976; Miller & Shanks, Citation1996; Sears & Funk, Citation1999). Theoretically, this development could reflect that attitudes become increasingly emotionally charged and ego-related to the individual the longer he or she holds them, eventually becoming more of identity-supporting “truths” than testable hypotheses (Klaczynski & Robinson, Citation2000).Footnote3 This process is likely to occur simultaneously with increasing self-selection into environments that are congruent with established attitudes, which will further increase crystallization (Sears, Citation1983). However, a gradual increase in attitude stability with age could also occur because personality traits typically become gradually more stable during adulthood (Roberts & DelVecchio, Citation2000).

Since age differences in stability of ATH never before have been examined by the means of panel data, the only existing evidence on the development trajectory of such attitudes comes from age-period-cohort (APC) studies based on repeated cross-sectional data (Andersen & Fetner, Citation2008; Danigelis et al., Citation2007; Pampel, Citation2016; Schwadel & Garneau, Citation2014; Sherkat et al., Citation2011; Twenge et al., Citation2016). While this body of research has produced conflicting findings, some of these studies have suggested that ATH constitute an exception to the aging-stability hypothesis (Andersen & Fetner, Citation2008; Danigelis et al., Citation2007; also see Schwadel & Garneau, Citation2014; Twenge et al., Citation2016). However, individual-level stability can only be indirectly assessed in cross-sectional data and APC analysis is moreover subject to an identification problem that impedes clear-cut inference.Footnote4 Furthermore, as I have shown elsewhere (Ekstam, Citation2021), prior APC studies of ATH have been flawed on a methodological level.

On a theoretical level, it is furthermore not clear why ATH would deviate from the general pattern of aging-stability. A more likely possibility is that ATH follow a similar trajectory as does symbolic racism, with an increase in stability during early adulthood and a decrease in stability during late adulthood (Henry & Sears, Citation2009), assuming that these kinds of attitudes share psychological roots (see Allport, Citation1954; Duckitt & Sibley, Citation2007). However, Henry and Sears (Citation2009) propose that symbolic racism decreases in crystallization during late adulthood because older adults may have difficulties comprehending the complicated and political language of modern racism. While the issue of homosexuality and related questions are not necessarily straightforward for everyone, such questions are nevertheless arguably less complicated and multifaceted than are questions about racial inequality nowadays. ATH might for this reason remain stable even in old age, in line with the impressionable-years model or the increasing-persistence model.

Method

Data

Data used in this paper are drawn from the General Social Survey (GSS) Panel Studies. Starting in 2006, the GSS introduced a rotating panel design for a subset of respondents (n = 2,000) within the main cross-sectional sample. These respondents were subsequently reinterviewed in 2008 (n = 1,536) and again in 2010 (n = 1276) as part of the conventional GSSs those years. This design was repeated with a new subset of respondents (n = 2,023) within the fresh cross-sectional sample of the GSS 2008, with reinterviews held in 2010 (n = 1,581) and again in 2012 (n = 1,295), and with yet a new subset of respondents (n = 2044) within the fresh cross-sectional sample of the GSS 2010, with reinterviews held in 2012 (n = 1,551) and again in 2014 (n = 1,304).Footnote5 Altogether, this gives three different four-year, three-wave panel surveys that use the same sampling procedure and questionnaire. For the main analyses in this paper, data are pooled from all three surveys in order to increase observations across the range of age and to increase statistical power.Footnote6 However, due to few observations among very old respondents, the pooled sample is restricted to respondents aged between 18 and 80 at T1.Footnote7 This gives a pooled T1–T2 sample of 4,482 observations and a pooled T1–T3 sample of 3,765 respondents.

While the relatively short time span of the GSS panels obviously only allows for estimation of lifespan variation in stability based on extrapolations of age differences in stability over the short run (four years), the data are nationally representative and of high quality. To my knowledge, more long-term panel data on ATH do not currently exist in the American context.Footnote8

Attitudinal measures

ATH are in this paper measured by two items, both of which are included in each survey and each wave of the GSS panels.Footnote9 The first item asks whether same-sex couples should have the right to marry, scored on a five-step Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Rescaled 0–1, with 1 denoting a nondiscriminatory attitude, this item has a mean of .46 (SD = .39) in the pooled T1 sample, .48 (SD = .38) in the pooled T2 sample, and .53 (SD = .38) in the pooled T3 sample. The second item asks whether sexual relations between two adults of the same sex are wrong or not, with four possible response options: 1 (always wrong), 2 (almost always wrong), 3 (only sometimes wrong), and 4 (not wrong at all). Rescaled 0–1, with 1 denoting a nondiscriminatory attitude, this item has a mean of .45 (SD = .47) in the pooled T1 sample, .47 (SD = .47) in the pooled T2 sample, and .49 (SD = .48) in the pooled T3 sample.

These two items are both likely to tap prejudiced beliefs and cognitive bias toward gays and lesbians, as well as negative affect, contempt, and perhaps even fear of homosexuality. However, the first item is clearly more political than the second item and may therefore also activate notions of tolerance amongst the respondents. For example, it is possible to believe that same-sex sexual practices are morally objectionable but to nevertheless concede the right to marry to same-sex couples on the basis of general principles of tolerance. The item regarding same-sex marriages furthermore has a clearer connection to religious concerns than the more general item has. For these reasons, I will analytically treat these two items as separate indicators of ATH rather than combining them into an index. I will refer to the first item as the same-sex marriages item and to the second item as the acceptance of homosexuality item.Footnote10

Additionally, in order to obtain reference points against which the temporal stability of the ATH items can be evaluated, items tapping political ideology, racial attitudes, gender attitudes as well as attitudes toward immigration and narcotics are also subject to longitudinal analysis. Question wording, response options, and descriptive statistics for these items are presented in in the Appendix.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Differential stability and mean-level change across attitudes.

Table 3. Regression results of conditional change models (T1–T3 data).

Table 4. Regression results of conditional change models with quadratic age terms.

Analytic approach

Conditional change models with interaction terms between the lagged dependent variable and independent variables are employed for the main analyses in this paper. In its simplest form, a conditional change model works by regressing a dependent variable Y measured at time point t on the same variable Y measured at time point t-1 as well as other covariates measured at either t or t-1 (Finkel, Citation1995; for empirical applications, see, e.g.,, Hooghe & Meeusen, Citation2012; Smith, Citation2016).Footnote11 In this specification, the parameter estimate for the lagged dependent variable Yt-1 can be interpreted as a coefficient for the test-retest relationship for the item that constitutes the dependent variable or, more simply put, as a “stability effect” of Yt-1 on Yt (Finkel, Citation1995, p. 7). The inclusion of the lagged dependent variable also serves the purpose of accounting for the negative correlation between initial scores and subsequent change (i.e., regression to the mean) that normally exists in panel data (Aickin, Citation2009).

Moreover, by including an interaction term between the lagged dependent variable and another covariate, the parameter estimate for the interaction term can be interpreted as the stability effect conditioned on the values of the given covariate. Accordingly, in order to test if the stability of ATH is conditioned by age, models are fitted in which the response to a given ATH item at Tt is predicted by an interaction between the response to the same item at Tt-1 and a continuous age variable (for a similar approach, see Henry & Sears, Citation2009). Since two of the lifespan development models predict a curvilinear relationship between age and attitude stability, extended models also include a quadratic age term and an interaction between it and the lagged dependent variable. Including a set of dummy variables controlling for panel sample membership, this model can thus be written as:

+

+

(

+

(

x

+

+

(

x

+

+

where is the intercept,

represents the set of dummy variables controlling for panel sample membership, and

is the error term. In this specification, a statistically significant positive interaction effect between

and

indicates that stability (the test-retest relationship) increases with age. Correspondingly, a statistically significant negative interaction effect between

and

indicates that the increase in stability levels off or, if the effect is strong enough, decreases at high values of age.

Since attitude stability due to crystallization is best evaluated over the long run (Sears & Funk, Citation1999), the analyses of how age conditions stability will focus on the pooled T1–T3 data.Footnote12 All analyses are weighted using the panel sample weights that are supplied with the GSS Panel Studies.Footnote13 Conditional change models are fitted using ordinary least square estimation and by the means of Stata 15.

Independent variables

In the conditional change models, the independent variable of most interest is the respondent’s age, measured at Tt-1. However, covariates for education, sex, religious affiliation, and political ideology, each of which are interacted with the lagged dependent variable (as well as with age), are also included in extended models in order to account for compositional differences across the span of age (cohort).Footnote14 Each of these variables are measured at Tt.Footnote15 Education is a five-step continuous variable (rescaled 0–1) running from less than high school degree to graduate degree. Sex is a dummy variable with male as the reference category. Religious affiliation is a categorical variable that differentiates between nonaffiliated, Protestant, Catholic, and other affiliation, with nonaffiliated set as the reference category. Political ideology is a continuous variable measured by a seven-step party identification item (rescaled 0–1), running from strong Democrat to strong Republican, with independent as the middle option.Footnote16 Descriptive statistics for all independent variables are presented in .

Results

Test-retest reliability, as indexed by the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, was first computed for all attitudinal items in the pooled data without consideration of age in order to examine how differential stability varies across attitudinal domains. As can be seen in , test-retest reliability varies between .44 and .83 across items in the T1–T2 data and between .43 and .80 across items in the T1–T3 data. Except for two items, test-retest reliability is lower in the four-year data than in the two-year data, which is suggestive of a negative relationship between attitude stability and panel length.Footnote17

Regardless of panel length, the by far highest stability is exhibited by the party identification item (rT1–T2 = .83, rT1–T3 = .80). Apparently, Americans do not wobble much when it comes to partisanship.Footnote18 However, in comparison to the rest of the items, stability is also notably high for the two ATH items. In the T1–T3 data, the acceptance of homosexuality item and the same-sex marriages item have a test-retest reliability of .72 and .70, respectively, and both items have a reliability of .72 in the T1–T2 data. For comparison, the liberal-conservative self-placement item has a test-retest reliability of .59 in the T1–T3 data and .61 in the T1–T2 data, despite directly tapping the respondent’s political ideology, and the items on racial issues, preferential hiring of women, and immigration exhibit an even lower level of stability.Footnote19 The two ATH items are even more stable than the item on abortion and the item on marijuana, despite the fact that the latter two items both have a dichotomous (agree or disagree) response scale (see in the Appendix).Footnote20

Taken together, ATH stand out as remarkably stable on the individual-level, even in comparison to attitudes regarding other salient political issues and attitudes that theoretically also fit the “predisposition” description. The high level of individual-level stability of ATH appears particularly noteworthy in light of the markedly low aggregate-level stability in those attitudes during the surveyed time period. Over the duration of the panels, the pooled sample became about .03 scale-points or 7% more accepting of homosexuality, and about .07 scale-points or 15% more supportive of same-sex marriages.Footnote21 That is, the sample shifted considerably in a liberal direction but the relative ordering of respondents with regard to their attitudes remained largely stable. This suggests that ATH constitutes a highly crystallized attitude dimension in the contemporary American context.

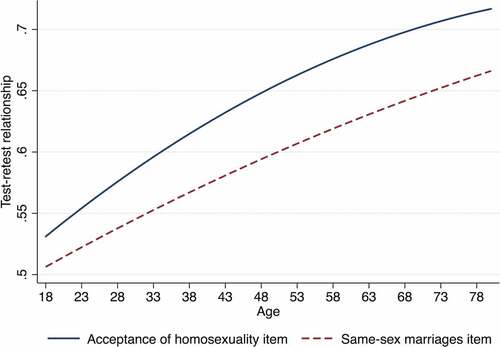

Turning to the question of whether or not attitudes vary in stability across the lifespan, the ATH items were specified as the dependent variable in conditional change models in which age was interacted with the lagged dependent variable. Results of these models using the pooled T1–T3 data are presented in . In the reduced models, the parameter estimate for the lagged dependent variable is .576 (p < .001) when the acceptance of homosexuality item constitutes the dependent variable, and .550 (p < .001) when the same-sex marriages item constitutes the dependent variable. In other words, the test-retest relationship for the respective items is considerable even among the youngest respondents in the sample.Footnote22 However, as indicated by the statistically significant positive interaction between age and the lagged dependent variable in both models (b = .003, p < .05), the test-retest relationship for the respective items nevertheless increases as a function of age.Footnote23 According to these models, the test-retest relationship for a respondent aged 80 years at T1 is .82 (.576 + .003 80) for the acceptance of homosexuality item, and .79 (.550 + .003

80) for the same-sex marriages item.

Adding the complete set of covariates to these models improves model fit but reduces the parameter estimates for the interaction term between age and the lagged dependent variable slightly for both items. However, the interaction term remains positive (b > .002) and is statistically significant on at least the 90% confidence level for both items even when compositional differences across cohorts in education level, ideology, sex, and religious affiliation are accounted for.Footnote24 According to these models, the test-retest relationship for the acceptance of homosexuality item increases with about 35% between age 18 and 80, and, over the same age span, the test-retest relationship for the same-sex marriages item increases with about 29%. While these are only extrapolated estimates based on short-term panel data, they nevertheless suggest that ATH become considerably more stable across the adult lifespan. This supports the aging-stability hypothesis.

Looking at the interaction effects for the covariates other than age, education has a positive effect on stability but the effect is comparatively weak and statistically significant only when the same-sex marriages item constitutes the dependent variable (b = .089, p < .1). This result is unexpected in light of previous findings of considerable educational differences in stability for other types of political attitudes (Visser & Krosnick, Citation1998; Westholm & Niemi, Citation1992). Somewhat surprising is also that neither sex nor ideology has a statistically significant relationship with stability, despite both variables being powerful predictors of ATH in terms of mean-level, and that a statistically significant difference between religious groups exists only when the acceptance of homosexuality item constitutes the dependent variable.Footnote25,Footnote26 Thus, there seems to be only one variable that has a strong and consistent relationship with stability in ATH, and that is age.

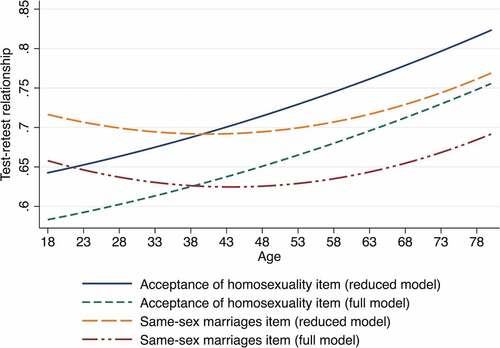

Finally, does the increase in stability of ATH continue throughout the life cycle, as predicted by the increasing-persistence model, or does the increase in stability level off after early adulthood, as predicted by the impressionable-years model? Alternatively, does attitudinal development follow a hump-shaped trajectory, with a decrease in stability during late adulthood, as the later-life decline model predicts? In order to answer these questions, the previously fitted conditional change models are refitted with a squared age term (which also is interacted with the lagged dependent variable and the socio-demographic control variables), thus allowing the test-retest relationship for the respective ATH items to vary as a quadratic function of age.

As can be seen from and the marginal effects presented in , the relationship between age and stability is approximately linear regardless of which ATH item that constitutes the dependent variable. While the interaction effect between age-square and the lagged dependent variable is negative in all models, the effect is neither strong nor statistically significant. In the pooled T1–T2 data, an approximately linear relationship between age and stability is also estimated when the acceptance of homosexuality item constitutes the dependent variable, but the relationship is slightly u-shaped when the same-sex marriages item constitutes the dependent variable (see in the Appendix). Taken together, these results nevertheless support the increasing-persistence model, even if a decline in stability after age 80 years cannot be ruled out.Footnote27

Figure 2. Stability of attitudes toward homosexuality across the lifespan (T1–T3 data).

Discussion and conclusion

This is the first study to my knowledge that has examined the individual-level stability of ATH and how stability in such attitudes develops across the lifespan by the means of panel data. Drawing upon data representative of the American adult population, this study provides two main findings of substantial interest to the field on change and continuity in ATH.

First, ATH are found to be exceptionally stable on the individual-level in comparison to other types of political attitudes that in previous research have been found to exhibit high levels of stability, such as racial attitudes. In fact, ATH are according to some measures even more stable than political ideology. Second, I provide novel evidence that ATH increase in stability with age. Between age 18 and 80, ATH increase in stability in an essentially linear fashion. Controlling for compositional differences across age groups, this increase is estimated to be between 29 and 35%. This suggests that ATH are primarily formed early in life and that such attitudes become increasingly crystallized with age, which is contrarily to what has been suggested elsewhere (Andersen & Fetner, Citation2008; Danigelis et al., Citation2007).

While speculative, one psychological basis for the gradual increase in stability with age could be that individuals become increasingly entrenched and emotionally invested in their attitudes and consequently less open to change over time. However, an age-graded increase in self-selection out of environments that are incongruent with already established attitudes is also likely to play a role here. For example, an individual who has a positive view on homosexuality is unlikely to establish and nurture a friendship with someone who holds very negative attitudes on the subject, and this kind of selection process is likely to increase as attitude crystallization increases, which will further reinforce crystallization. Another possible explanation is that ATH become gradually more stable with age because the personality dispositions underlying such attitudes become gradually more stable with age (Roberts & DelVecchio, Citation2000). Yet another possibility is that the causal relationship between ATH and personality dispositions strengthens with age. These possible explanations are not empirically examined in this paper, but they represent important venues for future research.

The finding that ATH increase in stability with age has implications for our understanding of how such attitudes change on the aggregate-level as well. Namely, it suggests that change-inducing idiosyncratic events will leave attitudinal differences across birth cohorts (cohort effects) in their wake, as cohorts being young at the time will be influenced the most. This, in turn, suggests that the liberalization of American public opinion over the past three decades to some non-trivial extent has been driven by generational replacement (inter-cohort change). While this might not seem like a particularly controversial suggestion, age-period-cohort analyses on the subject are actually inconclusive. Whereas some studies maintain generational replacement has been crucial for overall change (e.g., Keleher & Smith, Citation2012; Pampel, Citation2016; Sherkat et al., Citation2011), other studies conclude that the impact of generational replacement has been negligible (e.g., Schwadel & Garneau, Citation2014; Twenge et al., Citation2016). The findings presented in this paper do not settle that discussion, but they support the claims of the former group of studies.

One limitation of this paper should be acknowledged, however. Namely, the analyses conducted here have all relied on short-term multi-cohort panel data. As such, the lifespan developmental trajectories estimated in this paper are based on extrapolations of age differences in stability over short periods of time (four years) rather than on actual lifespan data. This presents a problem of interpretation. Namely, what appear as age differences in stability may instead be cohort differences in stability. For example, it is possible that older birth cohorts have more stable attitudes than younger cohorts because the former grew up and formed their attitudes during times when homosexuality as a social and political issue was comparatively less complex and polarized. While this possibility cannot be ruled out by any statistical means, cohort effects are nevertheless unlikely to drive results in light of the overall development toward increasing societal acceptance of homosexuality over the past few decades and the fact that anti-LGBTQ attitudes are more prevalent among older cohorts. In other words, recent zeitgeist changes are likely to have undermined the beliefs of older cohorts more than the beliefs of more recent cohorts. With this in consideration, attitude stability should, net of age effects, be lower among older cohorts than among younger cohorts today, meaning that age effects, if anything, might be underestimated in this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Outside of the American context, Hooghe and Meeusen (Citation2012) found an indicator of homophobia to be highly stable among young adults (aged 18–21) in a Belgian three-year panel.

2. The later-life decline model has also been referred to as the midlife-stability model (Alwin, Citation1994) or as the life-stages model (Visser & Krosnick, Citation1998).

3. A gradual increase in stability across the lifespan is also compatible with a Bayesian perspective on learning, in which the marginal impact of each new experience declines as a function of the accumulation of experiences (see Achen, Citation1992; Bartels & Jackman, Citation2014).

4. Age-period-cohort analysis is subject to an identification problem since age, period, and cohort are confounded with one another in repeated cross-sectional data (period—cohort = age). This renders estimation of effects associated with the three variables impossible unless a constraint on at least one of them is imposed, but it is the constraint that determines the best-fitting solution out of the infinite set of possible solutions of linear age, period, cohort effects that exist due to the fact that the three variables are not mathematically independent of one another. Because of this, APC models are highly sensitive to model specification and different constraints can produce different results (Bell & Jones, Citation2013; Ekstam, Citation2021; Glenn, Citation2005).

5. Consult the General Social Surveys 2006–2014 Panel Codebook (Smith & Schapiro, Citation2017) for information about sampling procedure and interviewing technique used in the GSS panel studies.

6. If surveys are analyzed separately, observations are less than 10 for several age-year units across the range of age.

7. In the raw data, age has a range from 18 to 89. Restricting the age range to 18–80 results in a 2.8% (110 observations) decrease in sample size for the pooled T1–T3 data.

8. Outside of the American context, the British Household Panel Studies, which includes an item on homosexuality biannually between 2000 and 2008, represent an interesting data source for future research.

9. The GSS includes additionally three items that concerns homosexuality. These are all binary (agree or disagree), asking the respondent whether or not a male homosexual: (1) should be allowed to make public speeches in the respondent’s local community, (2) should be allowed to teach at colleges or universities, and (3) should have the pro-gay book he has written removed from the respondent’s public library. However, these items have an overwhelming preponderance of nondiscriminatory responses in the data, skewness that can artificially suppress test-retest reliability (Dunlap, Chen, & Greer, Citation1994). For this reason, these items are not used.

10. The correlation between the same-sex marriages item and the acceptance of homosexuality item is .69 in the pooled T1 sample, .70 in the pooled T2 sample, and .70 in the pooled T3 sample.

11. The choice between specifying a covariate as Xt or Xt-1 in a conditional change model depends on whether the causal lag of the given covariate to influence the dependent variable is assumed be shorter than the time elapsed between waves of measurement. However, this choice is of little importance with respect to variables that are highly stable over time (Finkel, Citation1995, pp. 12–13).

12. Models are also fitted to the T1–T1 data and results from these models are continually reported in the text.

13. Weighting is done using the wtpannr12 weight for the pooled T1–T2 sample and the wtpannr123 weight for the pooled T1–T3 sample.

14. While education, sex, religious affiliation, and political ideology are approximately time-invariant on the individual-level, they nevertheless covary with age (cohort) in the data. For example, age has a statistically significant hump-shaped relationship with education in the pooled T1 sample, and individuals with high levels of education tend to have more stable attitudes than individuals with low levels of education (Visser & Krosnick, Citation1998; Westholm & Niemi, Citation1992). Similarly, having a religious affiliation is more common among older panel participants and it is conceivable that some religious beliefs exert a stabilizing influence on one’s views on homosexuality.

15. Measuring education, sex, religious affiliation, and political ideology at Tt-1 does not substantially change the results.

16. The party identification item is preferred over the liberal-conservative self-placement item as a measure of political ideology because it exhibits a considerably higher temporal stability in the data.

17. A negative relationship between stability and panel length is also reported by Sears and Funk (Citation1999) and by Roberts and DelVecchio (Citation2000).

18. The extraordinary level of stability of party identification reported here is in line with the results of previous studies (e.g., Alwin et al., Citation1991; Jennings & Markus, Citation1984; Stoker & Jennings, Citation2008).

19. The test-retest reliability coefficients for the items on racial issues change only slightly if samples are restricted to respondents registered as white.

20. Ceteris paribus, test-retest reliability is likely to be higher for an item with a dichotomous (agree or disagree) response scale than for an item with a Likert response scale, as movement across the former scale entails greater change.

21. The aggregate-level shift in the pooled panel sample corresponds fairly well to the shift seen across cross-sectional samples during the time period at issue (Daniels, Citation2019; Pampel, Citation2016).

22. For example, the estimated test-retest relationship for a respondent aged 18 at T1 is .63 (.576 + .003 18) for the acceptance of homosexuality item, and .61 (.550 + .003

18) for the same-sex marriages item.

23. If panels are analyzed separately, a statistically significant positive interaction effect between age and the lagged dependent is estimated for both ATH items in the 2008–2010–2012 panel and in the 2010–2012–2014 but for neither item in the 2006–2008–2010 panel.

24. In the pooled T1–T2 data, a statistically significant positive interaction effect between age and the lagged dependent variable is estimated for the acceptance of homosexuality item (b = .003, p < .05) but the interaction is not statistically significant for the same-sex marriages item. See in the Appendix for the complete regression results of models using the pooled T1–T2 data.

25. Females have more stable attitudes than men in the pooled T1–T2 data when the acceptance of homosexuality item constitutes the dependent variable (see Table A2 in the Appendix).

26. If the ideology variable is “folded” (0 = independent; 1 = independent near democrat/republican; 2 = not strong democrat/republican; 3 = strong democrat/republican), the interaction term between it and the lagged dependent variable is positive for both ATH items (suggesting that stability is positively associated with partisan strength) but these interaction effects are not statistically significant.

27. If the age range is uncapped (18–89), the test-retest relationship has more of a hump-shaped trajectory across the range of age. However, the interaction effect between age-squared and the lagged dependent variable remains outside of conventional levels of statistical significance even in this case.

References

- Achen, C. H. (1992). Social psychology, demographic variables, and linear regression: Breaking the iron triangle in voting research. Political Behavior, 14(3), 195–211. doi:10.1007/BF00991978

- Aickin, M. (2009). Dealing with change: Using the conditional change model for clinical research. The Permanente Journal, 13(2), 80–84. doi:10.7812/tpp/08-070

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. New York, NY: Addison-Wesley.

- Alwin, D. F. (1994). Aging, personality, and social change: The stability of individual differences over the adult life span. In D. L. Featherman, R. M. Lerner, & M. Perlmutter (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (1 ed., pp. 135–185). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Alwin, D. F., Cohen, R. L., & Newcomb, T. M. (1991). Political attitudes over the life span: The Bennington women after fifty years. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Alwin, D. F., & Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 169–195. doi:10.1086/229744

- Andersen, R., & Fetner, T. (2008). Cohort differences in tolerance of homosexuality attitudinal change in Canada and the United States, 1981–2000. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(2), 311–330. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn017

- Armenia, A., & Troia, B. (2017). Evolving opinions: Evidence on marriage equality attitudes from panel data. Social Science Quarterly, 98(1), 185–195. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12312

- Bartels, L. M., & Jackman, S. (2014). A generational model of political learning. Electoral Studies, 33, 7–18. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.06.004

- Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2013). The impossibility of separating age, period and cohort effects. Social Science & Medicine, 93, 163–165. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.029

- Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

- Caspi, A., & Roberts, B. W. (2001). Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry, 12(2), 49–66. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1202_01

- Converse, P. E. (1974). Nonattitudes and American public opinion: Comment: The status of nonattitudes. The American Political Science Review, 68(2), 650–660. doi:10.1017/S0003055400117435

- Converse, P. E. (1976). The dynamics of party support: Cohort-analyzing party identification. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Converse, P. E., & Markus, G. B. (1979). Plus ca change: The new CPS Election Study Panel. American Political Science Review, 73(1), 32–49. doi:10.2307/1954729

- Cullen, J. M., Wright, L. W., Jr, & Alessandri, M. (2002). The personality variable openness to experience as it relates to homophobia. Journal of Homosexuality, 42(4), 119–134. doi:10.1300/J082v42n04_08

- Daniels, R. S. (2019). The evolution of attitudes on same-sex marriage in the United States, 1988–2014. Social Science Quarterly, 100(5), 1651–1663. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12673

- Danigelis, N. L., Hardy, M., & Cutler, S. J. (2007). Population aging, intracohort aging, and sociopolitical attitudes. American Sociological Review, 72(5), 812–830. doi:10.1177/000312240707200508

- Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2007). Right wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice. European Journal of Personality, 21(2), 113–130. doi:10.1002/per.614

- Dunlap, W. P., Chen, R., & Greer, T. (1994). Skew reduces test-retest reliability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(2), 310–313. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.310

- Eaves, L. J., & Hatemi, P. K. (2008). Transmission of attitudes toward abortion and gay rights: Effects of genes, social learning and mate selection. Behavior Genetics, 38(3), 247–256. doi:10.1007/s10519-008-9205-4

- Ekstam, D. (2021). The liberation of American attitudes to homosexuality and the impact of age, period, and cohort effects. Social Forces, Soaa131, 100(2), 905–929. doi:10.1093/sf/soaa131

- Finkel, S. E. (1995). Causal analysis with panel data: Quantitative applications in the social sciences (1 ed.). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Glenn, N. D. (1980). Values, attitudes, and beliefs. In J. Kagan & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Constancy and change in human development (pp. 596–640). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Glenn, N. D. (2005). Cohort analysis: Quantitative applications in the social sciences (2 ed.). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Gonsalkorale, K., Sherman, J. W., & Klauer, K. C. (2009). Aging and prejudice: Diminished regulation of automatic race bias among older adults. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(2), 410–414. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.11.004

- Grasso, M. T., Farrall, S., Gray, E., Hay, C., & Jennings, W. (2017). Thatcher’s children, Blair’s babies, political socialization and trickle-down value change: An age, period and cohort analysis. British Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 17–36. doi:10.1017/S0007123416000375

- Hatemi, P. K., Funk, C. L., Medland, S. E., Maes, H. M., Silberg, J. L., Martin, N. G., & Eaves, L. J. (2009). Genetic and environmental transmission of political attitudes over a life time. Journal of Politics, 71(3), 1141–1156. doi:10.1017/S0022381609090938

- Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2009). The crystallization of contemporary racial prejudice across the lifespan. Political Psychology, 30(4), 569–590. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00715.x

- Hooghe, M., & Meeusen, C. (2012). Homophobia and the transition to adulthood: A three year panel study among Belgian late adolescents and young adults, 2008–2011. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(9), 1197–1207. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9786-3

- Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Janssen, D. J., & Scheepers, P. (2018). How religiosity shapes rejection of homosexuality across the globe. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(14), 1974–2001. doi:10.1080/00918369.2018.1522809

- Jennings, M. K. (1990). The crystallization of orientations. In J. W. van Deth & M. K. Jennings (Eds.), Continuities in political action (pp. 313–346). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.

- Jennings, M. K., & Markus, G. B. (1984). Partisan orientations over the long haul: Results from the three-wave Political Socialization Panel Study. The American Political Science Review, 78(4), 1000–1018. doi:10.2307/1955804

- Jennings, M. K., & Stoker, L. (2004). Social trust and civic engagement across time and generations. Acta Politica, 39(4), 342–379. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500077

- Keiller, S. W. (2010). Abstract reasoning as a predictor of attitudes toward gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(7), 914–927. doi:10.1080/00918369.2010.493442

- Keleher, A., & Smith, E. R. (2012). Growing support for gay and lesbian equality since 1990. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(9), 1307–1326. doi:10.1080/00918369.2012.720540

- Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Klaczynski, P. A., & Robinson, B. (2000). Personal theories, intellectual ability, and epistemological beliefs: Adult age differences in everyday reasoning biases. Psychology and Aging, 15(3), 400–416. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.15.3.400

- Krendl, A. C., & Kensinger, E. A. (2016). Does older adults’ cognitive function disrupt the malleability of their attitudes toward outgroup members?: An FMRI investigation. PLOS One, 11(4), e0152698. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152698

- Krosnick, J. A., & Alwin, D. F. (1989). Aging and susceptibility to attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(3), 416–425. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.416

- Krosnick, J. A., & Schuman, H. (1988). Attitude intensity, importance, and certainty and susceptibility to response effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 940–952. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.940

- Lee, H. Y., & Mutz, D. C. (2019). Changing attitudes toward same-sex marriage: A three-wave panel study. Political Behavior, 41(3), 701–722. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9463-7

- Ludeke, S. G., & Krueger, R. F. (2013). Authoritarianism as a personality trait: Evidence from a longitudinal behavior genetic study. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 480–484. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.015

- Lyons, J. (2017). Family and partisan socialization in red and blue America. Political Psychology, 38(2), 297–312. doi:10.1111/pops.12336

- Miller, W. E., & Shanks, J. M. (1996). The new American voter. Cambridge, CA: Harvard University Press.

- Nagoshi, J. L., Adams, K. A., Terrell, H. K., Hill, E. D., Brzuzy, S., & Nagoshi, C. T. (2008). Gender differences in correlates of homophobia and transphobia. Sex Roles, 59(7–8), 521–531. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9458-7

- NORC. (2018). General social survey three-wave panels Retrieved12 February 2021. https://gss.norc.org/get-the-data/stata

- Osborne, D., Sears, D. O., & Valentino, N. A. (2011). The end of the solidly Democratic south: The impressionable-years hypothesis. Political Psychology, 32(1), 81–108. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00796.x

- Pampel, F. C. (2016). Cohort changes in the social distribution of tolerant sexual attitudes. Social Forces, 95(2), 753–777. doi:10.1093/sf/sow069

- Poteat, V. P., Espelage, D. L., & Green, H. D., Jr. (2007). The socialization of dominance: Peer group contextual effects on homophobic and dominance attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1040–1050. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1040

- Roberts, B. W., & DelVecchio, W. F. (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126(1), 3–25. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3

- Schwadel, P., & Garneau, C. R. H. (2014). An age–period–cohort analysis of political tolerance in the United States. The Sociological Quarterly, 55(2), 421–452. doi:10.1111/tsq.12058

- Sears, D. O. (1975). Political socialization. In F. I. Greenstein & N. W. Polsby (Eds.), Handbook of political science (pp. 93–153). Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Sears, D. O. (1981). Life stage effects on attitude change, especially among the elderly. In S. B. Kiesler, J. N. Morgan, & V. K. Oppenheimer (Eds.), Aging: Social change (pp. 183–204). London, England: Academic Press.

- Sears, D. O. (1983). The persistence of early political predispositions. In L. Wheeler & P. Shaver (Eds.), Review of personality and social psychology (pp. 79–116). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Sears, D. O. (1993). Symbolic politics: A socio-psychological theory. In S. Iyengar & W. J. McGuire (Eds.), Explorations in political psychology (pp. 113–49). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Sears, D. O., & Funk, C. L. (1999). Evidence of the long-term persistence of adults’ political predispositions. The Journal of Politics, 61(1), 1–28. doi:10.2307/2647773

- Sears, D. O., & Levy, S. (2003). Childhood and adult political development. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (1 ed., pp. 60–109). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Sears, D. O., & Valentino, N. A. (1997). Politics matters: Political events as catalysts for preadult socialization. American Political Science Review, 91(1), 45–65. doi:10.2307/2952258

- Sherkat, D. E., Powell-Williams, M., Maddox, G., & De Vries, K. M. (2011). Religion, politics, and support for same-sex marriage in the United States, 1988–2008. Social Science Research, 40(1), 167–180. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.08.009

- Smith, J. F. N. (2016). Same-sex marriage attitudes during the transition to early adulthood: A panel study of young Australians, 2008 to 2013. Journal of Family Issues, 37(15), 2163–2188. doi:10.1177/0192513X14560644

- Smith, W. S., & Schapiro, B. (2017). General social surveys 2006–2014 panel codebook. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, NORC.

- Stoker, L., & Jennings, M. K. (2008). Of time and the development of partisan polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 619–635. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00333.x

- Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A., & Wells, B. E. (2016). Changes in American adults’ reported same-sex sexual experiences and attitudes, 1973–2014. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(7), 1713–1730. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0769-4

- Tyler, T. R., & Schuller, R. A. (1991). Aging and attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(5), 689–697. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.5.689

- Verweij, K. J. H., Shekar, S. N., Zietsch, B. P., Eaves, L. J., Bailey, J. M., Boomsma, D. I., & Martin, N. G. (2008). Genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in attitudes toward homosexuality: An Australian twin study. Behavior Genetics, 38(3), 257–265. doi:10.1007/s10519-008-9200-9

- Visser, P. S., & Krosnick, J. A. (1998). Development of attitude strength over the life cycle: Surge and decline. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(6), 1389–1410. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1389

- Westholm, A., & Niemi, R. G. (1992). Political institutions and political socialization: A cross-national study. Comparative Politics, 25(1), 25–41. doi:10.2307/422095

Appendix

Table A1. Additional attitudinal measures.

Figure A1. Stability of attitudes toward homosexuality across the lifespan (T1–T2 data).

Table A2. Regression results of conditional change models (T1–T2 data).