ABSTRACT

Recent research has found that older lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ+) people have a negative attitude toward long term care services. To build upon this, we conducted a systematic review analyzing current research into the LGBTQ+ communities’ perspectives and experiences of care/nursing homes. Additionally, we sought to explore the attitudes of care/nursing home staff toward providing care for LGBTQ+ residents. To conduct this study, we used the databases Embase, Medline and Web of Science, which identified 19 articles for review. From this, we were able to draw several conclusions, including that LGBTQ+ participants were concerned that they would have to conceal their identity and experience abuse. Most staff had a positive attitude toward LGBTQ+ residents, but there were exceptions to this. Despite their positive attitude, staff often lacked awareness of LGBTQ+ issues. The results of this review suggest that care/nursing homes are not welcoming environments for sexual and gender minorities, and that staff require more training to support this community. We end with innovative suggestions to tackle these issues, such as designing coproduced services with the support of LGBTQ+ communities.

Across the UK, 1% of people aged over sixty-five identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (Office for National Statistics, Citation2021) and although there is a lack of data on transgender people, it is estimated that there are approximately 200,000–500,000 transgender people in the UK (Government Equalities Office, Citation2018).

Previous research has shown that some care/nursing home residents and staff can find conversations about sexuality uncomfortable, and that older people are often viewed as post sexual (Simpson, Brown Wilson, Brown, Dickinson, & Horne, Citation2017). The lack of conversations regarding sexuality may be especially damaging to residents who identify as a sexual minority, because this can result in the assumption that they are heterosexual. Hetero- and cisnormative language and attitudes have been reported in other care contexts and can put LGBTQ+ people in the uncomfortable position of having to either disclose their gender/sexuality, or stay silent, which may feel like lying or hiding (Logie et al., Citation2019; Ross & Setchell, Citation2019).

A report by the Care Quality Commission (CQC), found that in England, commissioners of care services do not sufficiently engage with the LGBTQ+ community. As a result of this, care services are not tailored to meet the needs of the group. This lack of consideration was shown to have an even greater impact on LGBTQ+ people living in care/nursing homes, resulting in feelings of isolation and exclusion (CQC, Citation2016).

LGBTQ+ individuals are likely to have differing health and care needs compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts. For example, older LGBTQ+ adults face higher levels of chronic disease such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS (National Institute of Medicine, Citation2011). Transgender individuals may have health issues relating to their hormone therapy (National Institute of Medicine, Citation2011). This group is also less likely to have support from children (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Barkan, Muraco, & Hoy-Ellis, Citation2013), which may make them more reliant on care/nursing homes, and more vulnerable to abuse. Many have faced discrimination from healthcare services in the past, which is more prevalent if they are also a person of color (Bradford, Reisner, Honnold, & Xavier, Citation2013; Jennings, Barcelos, McWilliams, & Malecki, Citation2019; Kattari, Walls, Whitfield, & Langenderfer-Magruder, Citation2015). These experiences may create a wariness toward care services.

A review by Caceres, Travers, Primiano, Luscombe, and Dorsen (Citation2020) investigated staff and LGBTQ+ individuals’ perspectives on American long-term services and support, including care homes and home care. It highlighted that LGBTQ+ individuals are concerned about discrimination in these settings. Additionally, they identified that staff have negative attitudes toward same-sex relationships among older people, and lack training on LGBTQ+ issues. This review builds upon this by examining these issues at an international level. Other countries may have different approaches to care and have different ethnic groups that need to be catered for.

As members of this community continue to grow and age, it is important that provisions are made for older LGBTQ+ people. The purpose of this review is to increase understanding of the perspectives and experiences of older LGBTQ+ people in care/nursing homes. The challenges faced by LGBTQ+ people are likely to have made their sexuality and/or gender an important aspect of their identity, so it is important to explore the experiences of these groups of people in this specific context. Additionally, this review explores attitudes of care/nursing home staff as this will affect the residents’ experiences. Our research question is therefore: what are the attitudes and experiences of older LGBTQ+ people in care/nursing homes, and those of care/nursing home staff? Following analysis of the articles, strategies are recommended to improve care for LGBTQ+ residents.

Method

Search strategy

This study is a systematic review, aiming to analyze available research with the intention of drawing conclusions and identifying areas of improvement for LGBTQ+ residents in care/nursing homes. This type of study was chosen because whilst there has been a significant amount of primary research into this field, there have been no studies reviewing recent data from an international perspective. In recent years, there has been a focus on improving social care, and it is important that LGBTQ+ voices and experiences are included in these efforts.

To do this systematic review, a database search using Embase, Medline and Web of Science was conducted. These databases were used because they have a focus on biomedical science and healthcare so would be appropriate for this study. By using three different databases, we were able to identify a large number of suitable articles to review. The following search terms were used: “Sexual and Gender Minorities” OR “Homosexuality or Homosexuality, Female or Homosexuality, Male or Bisexuality or Transgender person or Transsexualism” OR (LGBTQ+ or lesbian or transgender or queer or bisexual or pansexual or gay) AND “Homes for Aged OR Nursing Homes OR Care Homes or Residential Facilities OR Long Term- Care” AND “Older or Elderly.” These searches were used for several reasons. A range of phrases were used to describe LGBTQ+ identities to ensure all members of this diverse community were included. Members of the LGBTQ+ community identify with different labels, so it was important that the database search reflected this. For example, in the UK the term “transgender” is widely used but in the past “transsexual” was more commonly used, and there may still be people who identify more with the latter. We included the phrase “queer” because this has been reclaimed over the last few decades and used by some as an umbrella term for members of the LGBTQ+ community. However, it is important to acknowledge that for others it remains an offensive and highly emotive term. A number of different phrases were used as synonyms for “care/ nursing homes.” This is because the study has an international focus, and different phrases are used across the world to describe these settings.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Following the database search, a primary screening was conducted in which the titles and abstracts of articles were checked against our inclusion criteria. The articles had to be written in English and be primary research. This meant systematic reviews and care studies were excluded. Interventional studies were included to identify strategies for improvement. During the database search, the search was limited to papers published since 2010. However, in the initial screen it was decided that only papers published in the last 5 years were to be included. This is because during this period several countries have seen policy changes, such as the legalization of same sex marriage, reflecting a change in society’s attitudes toward the LGBTQ+ community (Kazyak & Stange, Citation2018; Murphy et al., Citation2016). In the review by Caceres et al. (Citation2020), older papers were analyzed, and they identified that staff had negative attitudes toward LGBTQ+ residents. As public awareness and acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community has increased, only more recent articles were included to determine if the attitudes of staff toward LGBTQ+ residents have improved. The project was specifically interested in LGBTQ+ perspectives on either nursing or care homes, so facilities such as hospitals, hospices and day centers were excluded. Another criterion was that the articles must have investigated care/nursing homes in a high-income country, based on the World Bank classification. This was to enable comparison between countries which are likely to have similar services to support older people. Only articles featuring LGBTQ+ adults aged at least fifty or care/nursing home staff were included. The LGBTQ+ individuals had to be this age, because younger adults are less likely to have considered their long-term future, and staff were included because they influence the residents’ experiences.

Data extraction and analysis

Following the database search, a primary screen was conducted, in which the articles were selected based on the inclusion criteria. To ensure the validity of this process, the primary screen was repeated by the second author, who checked every third paper. This meant a total of two reviewers were involved in the primary screening process. A secondary screen was then carried out, in which the full papers were read. Once the articles had been identified, they were appraised using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Following this, data extraction was conducted to obtain participant demographics and results. Common themes across the studies were identified and refined with the second author.

Results

Study selection

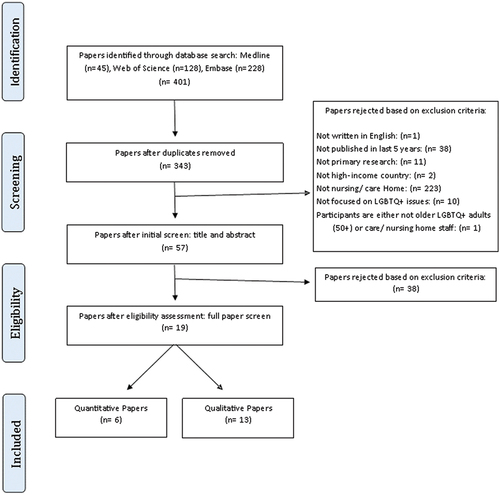

As shown in , the database search retrieved 401 articles. Following the removal of duplicates, an initial screen was carried out, in which the titles and abstract of the articles were rejected based on the exclusion criteria. 57 articles were then read in full, which identified 13 qualitative and 6 quantitative/mixed methods papers.

Study characteristics

This review includes thirteen qualitative, three quantitative and three mixed method papers. The qualitative papers used several approaches, including semi structed interviews, focus groups and participant observation to collect data. The quantitative and mixed method papers used surveys to access a larger sample, which mainly used a 5/6 point Likert Scale response to record participants’ data (Ahrendt, Sprankle, Kuka, & McPherson, Citation2017; Sharek, McCann, Sheerin, Glacken, & Higgins, Citation2015; Villar et al., Citation2019b; Willis, Raithby, Maegusuku-Hewett, & Miles, Citation2017). From the identified papers, nine were based on responses from care/nursing home staff, seven had exclusively LGBTQ+ respondents and three had the perspectives of staff and LGBTQ+ people. A range of staff was recruited for these studies, including managers, professionals, and care staff. As shown in , the following characteristics were highlighted for each study: race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and religion. These were identified to understand how representative the data is of the wider population and LGBTQ+ community. For example, only three papers featured transgender participants (Kortes-Miller, Boule, Wilson, & Stinchcombe, Citation2018; Putney, Keary, Hebert, Krinsky, & Halmo, Citation2018; Sharek et al., Citation2015), and most respondents were white.

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Critical appraisal and potential bias

To analyze and identify potential bias articles used in the review, MMAT () developed by Pluye, Gagnon, Griffiths, and Johnson-Lafleur (Citation2009) and Pace et al., Citation2012), was used. A common source of potential bias in the thirteen qualitative papers included in this study was the data collection and interpretation methods. Whilst most papers recorded the interviews, which eliminates the potential for misinterpretation by the researcher, two articles used notetaking to collect data (Leyerzapf, Visse, De Beer, & Abma, Citation2018; Sussman et al., Citation2018). The issue with this is that it relies on memory and the researcher may have missed details, making verification of the data by a second individual more difficult. To derive findings from the data, themes were identified, which is subjective as this relies on the interpretation by the researcher. To mitigate the inherent bias of this type of research, some studies used multiple people at different stages to verify these themes (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018; Putney et al., Citation2018; Villar, Serrat, Faba, & Celdran, Citation2015). However, other studies lacked information on how thematic analysis was conducted (Hafford-Letchfield, Simpson, Willis, & Almack, Citation2018; Willis et al., Citation2018; Willis, Maegusuku-Hewett, Raithby, & Miles, Citation2016). All the qualitative studies included supportive quotes. The quantitative and mixed method studies utilized surveys (Ahrendt et al., Citation2017; Sharek et al., Citation2015; Simpson, Almack, & Walthery, Citation2018; Villar et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Willis et al., Citation2017), which enabled a larger sample size compared to the qualitative studies. However, most respondents were white/Caucasian which is not representative of the care staff population. For example, ethnic minority groups made up 5% of the study conducted by Simpson et al., despite making up one fifth of care staff (Simpson et al., Citation2018).

Table 2. Critical analysis of studies using MMAT CT* = Can’t tell.

Findings

Across the articles, three themes were identified (): 1. Fears and concerns, 2. Staff values and knowledge and 3. Ideas for improvement. In , quotes supporting the themes are identified, and where possible the demographics of the quoted participant have been included. However, not all the articles included these details.

Table 3. Themes and supporting evidence.

Fears and concerns

In general, LGBTQ+ individuals felt care/nursing homes were heterosexual environments, so would not promote “coming out,” with the alternative to coming out being concealing those aspects of one’s identity (Benoit, Kordrostami, & Foreman, Citation2021; Kortes- Miller et al., Citation2018; Leyerzapf et al., Citation2018; Marhankova, Citation2019; Putney et al., Citation2018; Sharek et al., Citation2015; Waling et al., Citation2019; Westwood, Citation2016; Willis et al., Citation2016). Many LGBTQ+ participants were concerned about discrimination and abuse, which was a greater worry for those who were in more than one marginalized social position, such as being a First Nations person (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018). There were also fears of social isolation (Marhankova, Citation2019; Waling et al., Citation2019; Westwood, Citation2016; Willis et al., Citation2016).

Staff values and knowledge

Across the studies, care/nursing staff were generally supportive of older LGBTQ+ people (Simpson et al., Citation2018; Villar et al., Citation2015). There were notable exceptions to this however, as some staff suggested their colleagues may limit their physical contact with LGBTQ+ residents and made jokes directed at their sexuality (Villar et al., Citation2015). Whilst several staff expressed that “anyone who is gay or lesbian, we would treat the same as anybody else” (care home manager) (Hafford-Letchfield et al., Citation2018), many felt they did not have LGBTQ+ residents in their home (Simpson et al., Citation2018; Villar et al., Citation2019a; Willis et al., Citation2018). There were suggestions that religious beliefs sometimes motivated negative attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people (Ahrendt, Citation2017; Neville, Citation2015; Simpson, Citation2018). Additionally, staff felt they lacked knowledge and training on LGBTQ+ issues (Neville et al., Citation2015; Willis et al., Citation2016).

Ideas for improvement

LGBTQ+ individuals recommended changes such as use of inclusive language and introduction of LGBTQ+ friendly activities to improve the experiences of residents (Putney et al., Citation2018). Additionally, some participants expressed support for LGBTQ+ exclusive care/nursing homes, although others did not (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018; Marhankova, Citation2019; Willis et al., Citation2016).

Discussion

Fears and concerns

The participants’ fear that care/nursing homes were heterosexual spaces was echoed by the fact that there were staff in the studies who denied having LGBTQ+ residents (Simpson et al., Citation2018; Villar et al., Citation2019a; Willis et al., Citation2018). Residents were sometimes assumed to be heterosexual, forcing LGBTQ+ individuals to make the difficult decision of “coming out” or going “back into the closet” (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018). Concerns that “coming out” would make them vulnerable to abuse are understandable, given that these individuals came of age in an era where homosexuality was illegal (Clements & Field, Citation2014; Eskridge, Citation2004). Many LGBTQ+ individuals had experienced poor treatment in the hands of healthcare providers, so it is unsurprising that they were worried about entering into a care/nursing home, where they anticipated further discrimination from the staff and residents there (Bradford et al., Citation2013; Jennings et al., Citation2019; Kattari et al., Citation2015).

Across the studies, the LGBTQ+ respondents voiced concerns over receiving poor care and being mistreated (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018; Waling et al., Citation2019; Willis et al., Citation2016). One individual described that as a First Nations two-spirit person, they may face even more discrimination (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018). This example illustrates how care must be culturally sensitive to support individuals who are from ethnic minority backgrounds. It is vital that older LGBTQ+ people are not treated as a homogenous group, but as a diverse community with differing needs.

There is a lack of research into the experiences of transgender people in care/nursing homes; only three of the articles in this review featured transgender participants (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018; Putney et al., Citation2018; Sharek et al., Citation2015). However, the transgender individuals that were included expressed concern over entering a care/nursing home, sharing “horror stories about trans people in care facilities having to […] revert to their birth gender,” to avoid abuse (Kortes-Miller et al., Citation2018, p. 216). Another individual shared they were “unsure how I will continue to cross-dress when my freedom and mobility is decreased” (Shark et al., Citation2015, p. 236). This demonstrates that care homes are perceived to uphold rigid gender binaries. For the wellbeing of older transgender people, it is important that their gender identity is protected and that provisions are made to support any additional health needs they have. To understand the challenges this group face in residential settings, it is vital that more transgender individuals are included in future research.

The reality is that LGBTQ+ people in a care/nursing homes do experience discrimination from other residents, as described by respondents who suffered verbal abuse and social exclusion (Leyerzapf et al., Citation2018). The occurrence of this behavior is unacceptable and demonstrates that steps need to be taken to protect LGBTQ+ residents and educate other residents on these issues. Additionally, LGBTQ+ participants fear social isolation when entering a care home as they expect to be the only LGBTQ+ individual there (Waling et al., Citation2019). Older LGBTQ+ people may not have experienced life events that are expected in a heteronormative society, such as having children. This means they have less in common with their fellow residents, and face uncomfortable questions, such as “Don’t you have any grandchildren?” (LGBT male, 70) (Marhankova, Citation2019, p. 15). There were concerns that entering a residential facility may isolate them from their existing social networks (Westwood, Citation2016). The older LGBTQ+ generation are less likely to have support from children and more likely to have a “chosen family,” formed of close supportive friends, rather than disapproving family members (Hull & Ortyl, Citation2019). It is vital that these links are maintained, for example by welcoming friends and partners of LGBTQ+ residents and facilitating transport to LGBTQ+ events.

Staff values and knowledge

There were mixed responses from staff working in care/nursing homes about LGBQT+ residents, but generally they were supportive of LGBTQ+ people (Ahrendt et al., Citation2017; Simpson et al., Citation2018; Villar et al., Citation2019b; Willis et al., Citation2017). This contrasts with the findings by Caceres et al. who reported negative attitudes of staff toward same sex relationships. There are several reasons for this, including our inclusion of more recent papers from an international context. More recent research may have identified a positive attitude among staff because society in general is becoming more accepting of the LGBTQ+ community. Additionally, different countries may have differing attitudes and policies in place to support the LGBTQ+ community. Another reason for the different conclusions drawn by the two reviews is that there may be a different focus on the results of the studies. For example, in a study featured in both reviews, staff members of two care facilities responded to a vignette featuring a same sex, or opposite sex couple. The results of this study could be negatively interpreted because the staff working in the religiously affiliated facility were significantly less approving than the secular one. However, overall, there was no significant difference in staff approval between the different sexual interactions, which we have interpreted as a positive. This is because it demonstrates that generally care staff are supportive of same sex relationships (Ahrendt et al., Citation2017).

A common sentiment among staff was the concept of treating all residents “the same” (care home manager) (Hafford-Letchfield et al., Citation2018, p. 321). Whilst this is well intentioned, treating all residents the same in a heteronormative environment can lead to the erasure of residents’ LGBTQ+ identity. This attitude can result in staff making assumptions about a resident’s sexuality. Additionally, it can lead to the provision of activities and media that are aimed at heterosexual people, denying the interests of LGBTQ+ people. This attitude may stem from a lack of awareness and understanding of LGBTQ+ issues and the extent to which experiences of discrimination and erasure can shape an LGBTQ+ person’s perspective, since many staff report that they lack knowledge in this area (Neville et al., Citation2015; Willis et al., Citation2016, Citation2017). Several staff members stated that they did not have LGBTQ+ residents in their care/nursing home (Simpson et al., Citation2018; Villar et al., Citation2019a; Willis et al., Citation2018). Although this may be the case, it is likely that the lack of conversations regarding sexuality and gender have not enabled residents to disclose their identity.

Some staff expressed negative views toward the LGBQT+ community. When care staff were asked how residents’ sexuality would affect care provided by their colleagues, 9.4% felt they would limit contact and 7.6% suggested jokes directed at the resident would be made (Villar et al., Citation2015). Additionally, in the same study 7.5% of staff said they would encourage the resident to conceal their sexuality (Villar et al., Citation2015). It is unacceptable that older LGBTQ+ individuals who have experienced decades of institutional discrimination and abuse by healthcare providers, and other organizations, continue to experience this toward the end of their lives (Bradford et al., Citation2013; Jennings et al., Citation2019; Kattari et al., Citation2015; Serpe et al., Citation2017).

Some staff members disapproved of same sex relationships due to their religious or cultural beliefs but insisted this would not affect the care they provide (Hafford-Letchfield et al., Citation2018; Neville et al., Citation2015). However, these negative attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals may lead to unconscious bias, resulting in poorer care.

Ideas for improvement

To improve the experiences of LGBTQ+ older people in care/nursing homes, new strategies must be introduced. A resident who transferred from a nursing home without LGBTQ+ initiatives to one that had these in place described how she “went from feeling like a body to a whole person” (LGBTQ+ female resident) (Sussman et al., Citation2018, p. 126).

Arguably, the most important step in promoting inclusivity is to consider needs of minority groups when planning and developing care services. To appropriately meet the needs of the LGBTQ+ community, it is vital that during the commissioning process, in which services are designed and reviewed, there is active involvement of LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as members of other minority groups. Adopting a co-production approach, in which both service users and healthcare professionals collaborate to plan services, had positive results in mental health, with patients reporting better health outcomes when using coproduced services (Pocobello et al., Citation2020). As part of a shared approach to designing social care services, a toolkit could be developed in partnership with LGBTQ+ individuals. This could identify the needs of this community and set standards for care/ nursing homes to be measured against (Women and Equalities Committee, Citation2019).

A key step in creating a more inclusive environment in care/nursing homes is to increase staff training on LGBTQ+ issues (Leyerzapf et al., Citation2018). Across several studies, participants expressed concern over how they would be treated, and staff acknowledged that they lacked knowledge in this field (Kortes- Millar et al., Citation2018; Neville et al., Citation2015; Willis et al., Citation2016, Citation2017). Coproduction could also be used to aid staff training, using the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community to educate staff. This approach has been successfully trialed in the training of student nurses in the mental health field (Horgan et al., Citation2018). The use of LGBTQ+ community advisors demonstrated that the involvement of the LGBTQ+ community in staff training had positive outcomes (Hafford-Letchfield et al., Citation2018; Willis et al., Citation2018). This could be further expanded by producing a training resource to be used nationally, developed collaboratively with LGBTQ+ individuals. Putney et al. identified that it could be beneficial to use more inclusive language, such as the term “partner’,” rather than the gendered equivalent. This demonstrates how a more considerate use of language could be implemented to avoid assumptions being made about a resident’s sexuality (Putney et al., Citation2018, p. 898).

Whilst increased training would help improve understanding, it is important to acknowledge that some staff may still hold prejudices toward LGBTQ+ residents, which could result in discrimination and abuse. We also recognize that, as the results show, prejudice can sometimes come from other residents rather than staff members. This represents a serious challenge, since staff do not, and indeed should not, have full control or oversight of residents’ behaviors and private interactions. To compound the issue, care/nursing home residents are more likely than the general population to have cognitive impairments that impair their ability to understand the harm they are causing and enact changes to their own behaviors. In spite of these additional difficulties in enacting behavior change in this context, it is still vital that care/nursing homes have a well-publicized anonymous complaints system whereby both residents and staff feel empowered to raise any concerns.

Several individuals suggested that the introduction of LGBTQ+ friendly activities in care/nursing homes would be beneficial (Putney et al., Citation2018). In homes that had already organized activities aimed at LGBTQ+ individuals, there had been a largely positive response, with LGBTQ+ residents feeling comfortable to express themselves (Leyerzapf et al., Citation2018). However, it must be noted that a minority of LGBTQ+ participants found these unenjoyable, as they placed too much emphasis on their sexuality (Leyerzapf et al., Citation2018). This demonstrates that whilst it is important to provide a safe space for LGBTQ+ people, it is necessary to develop activities which encourage unity between LGBTQ+ and heterosexual, cisgender residents to avoid the formation of further divisions. To ensure these activities are a positive experience, it would be beneficial to develop the activities in collaboration with both the LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ residents.

In response to the suggestion of exclusively LGBTQ+ housing, there was a mixed response. Generally, lesbians were in favor of female/lesbian only accommodation, rather than including male LGBTQ+ individuals. This is because these women had built their lives around female partners and friendships (Willis et al., Citation2016). This challenges the assumption that all LGBTQ+ individuals have shared experiences so would benefit from shared accommodation, when in reality LGBTQ+ men and women have different experiences. These experiences are not only shaped by their sexuality, but also their gender identity, ethnicity, religion, and socio-economic status, so it is important that services are tailored to suit a resident’s needs.

It is perhaps an open question whether housing just for LGBTQ+ people, or for specific subgroups (e.g. lesbians) would benefit those communities in the long run. While they appear prima facie to provide solutions to the issues described in this paper of fears of discrimination as older people enter and experience care/nursing homes, they may serve to exacerbate the problem in other areas. For example, the existence of LGBTQ+ care/nursing homes may lead to an expectation or assumption that residents in other care/nursing homes are heterosexual or cisgender. We have seen from the papers in this review that this assumption already exists and that it harms people, so we should be wary of steps that may make this problem worse for LGBTQ+ people who find themselves in non-LGBTQ+ homes for whatever reason (for example, due to lack of availability in their area, or a desire not to segregate themselves). It could also be argued that the provision of LGBTQ+ care/nursing homes fails to address the real problems of homo- and transphobia that underlie LGBTQ+ people’s bad experiences and expectations about their residential care, and that the solution should be to improve conditions in all care/nursing homes rather than create dedicated spaces and leave these problems unchecked in wider society.

Instead of exclusively LGBTQ+ homes, a middle ground might be the development of overtly LGBTQ+-friendly care/nursing homes, so that care/nursing homes accepting those of all genders and sexualities (i.e. that are not exclusive) affirm and advertise their status as a way of allaying some of the fears that LGBTQ+ residents and potential residents may have. An accreditation scheme could be developed, perhaps with ratings to allow potential residents to make choices about where they go on the basis of how well the care/nursing home is deemed to be performing with regarding to inclusivity and the combating of homo- and trans-phobic attitudes, language, and practices. The “Pride in Care” quality standard, operated by UK-based charity Opening Doors, is an example of such a scheme (Opening Doors, Citation2022).

The themes identified and discussed in this review have demonstrated that there are real issues at play for LGBTQ+ people in care/nursing homes, and that while actively inclusive policies and practices, including staff training and reporting systems, can go some of the way toward ameliorating these, there are still serious challenges in implementing these in this context. A shift toward more exclusive spaces may be part of the solution, but also has significant disadvantages that will need to be negotiated carefully and with the representation and guidance of different LGBTQ+ groups.

Limitations

Generally, the studies lacked inclusion of transgender participants. This is an issue because transgender people face high levels of discrimination and are often excluded from discussions on LGBTQ+ issues, despite having played a vital role in the current and historic fight for equality (Osorio, Citation2017). Additionally, there was a lack of ethnic diversity, with an over-representation of white participants, which is problematic as people of color face additional issues.

The method of this study had a few limitations. For example, only two reviewers were involved in the primary screen due to limited resources. Additionally, only three databases were used for the search. To ensure that all possible articles were included, it may have been beneficial to include a fourth database. Finally, no truncated terms or wildcards were used in the database search. It may have been beneficial to include these to maximize the number of results.

Conclusion

This review has contributed to research in this field by identifying the challenges LGBQT+ individuals face when entering care/ nursing homes, such as fears of discrimination and exclusion. Additionally, we identified staff attitudes toward caring for this community. We have included innovative suggestions on how to improve the experience of LGBTQ+ individuals in care homes. These include having a more collaborative approach to commissioning services to ensure that the needs of minorities groups are met. This use of coproduction has had positive outcomes in the mental health sector and should be replicated in residential care. Additionally, it is vital that staff receive further training on LGBTQ+ issues, using resources designed by members of this community.

Author contributions

LS conceived the project, designed the study, undertook the review of the articles, and drafted the manuscript. SJ was involved in the secondary screening process and assisted with drafting and editing of the manuscript.

Statement of ethical approval

All data used are in the public domain, so no ethical approval was required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahrendt, A., Sprankle, E., Kuka, A., & McPherson, K. (2017). Staff member reactions to same-gender, resident-to-resident sexual behavior within long-term care facilities. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(11), 1502–1518. doi:10.1080/00918369.2016.1247533

- Benoit, I. D., Kordrostami, E., & Foreman, J. (2021). Senior sexual and gender minorities’ perception of healthcare services: A phenomenological approach. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 14(4), 1002–1010. doi:10.1080/20479700.2020.1724437

- Bradford, J., Reisner, S. L., Honnold, J. H., & Xavier, J. (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia transgender health initiative study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1820–1829. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796

- Caceres, B. A., Travers, J., Primiano, J. E., Luscombe, R. E., & Dorsen, C. (2020). Provider and LGBT individuals’ perspectives on LGBT issues in long-term care: A systematic review. Gerontologist, 60(3), e169–e183. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz012

- Care Quality Commision. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender people, a different ending: Addressing inequality in end of life care. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: CQC. Retrieved from https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20160505%20CQC_EOLC_LGBT_FINAL_2.pdf

- Clements, B., & Field, C. D. (2014). Public opinion toward homosexuality and gay rights in Great Britain. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(2), 523–547. doi:10.1093/poq/nfu018

- Eskridge, W. N. (2004). United States: Lawrence v. Texas and the imperative of comparative constitutionalism. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 2(3), 555–560. doi:10.1093/icon/2.3.555

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H.-J., Barkan, S. E., Muraco, A., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1802–1809. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110

- Government Equalities Office (GEO). (2018). Trans people in the UK. London, UK: Government Equalities Office.

- Hafford-Letchfield, T., Simpson, P., Willis, P. B., & Almack, K. (2018). Developing inclusive residential care for older lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) people: An evaluation of the care home challenge action research project. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(2), e312–e320. doi:10.1111/hsc.12521

- Horgan, A., Manning, F., Bocking, J., Happell, B., Lahti, M., Doody, R., … Biering, P. (2018). ‘To be treated as a human’: Using co‐production to explore experts by experience involvement in mental health nursing education – The COMMUNE project. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(4), 1282–1291. doi:10.1111/inm.12435

- Hull, K. E., & Ortyl, T. A. (2019). Conventional and cutting-edge: Definitions of family in LGBT communities. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 16(1), 31–43. doi:10.1007/s13178-018-0324-2

- Jennings, L., Barcelos, C., McWilliams, C., & Malecki, K. (2019). Inequalities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health and health care access and utilization in Wisconsin. Preventive Medicine Reports, 14, 100864. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100864

- Kattari, S. K., Walls, N. E., Whitfield, D. L., & Langenderfer-Magruder, L. (2015). Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender people in the United States. International Journal of Transgenderism, 16(2), 68–79. doi:10.1080/15532739.2015.1064336

- Kazyak, E., & Stange, M. (2018). Backlash or a positive response?: Public opinion of LGB issues after Obergefell v. Hodges. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(14), 2028–2052. doi:10.1080/00918369.2017.1423216

- Kortes-Miller, K., Boule, J., Wilson, K., & Stinchcombe, A. (2018). Dying in long-term care: Perspectives from sexual and gender minority older adults about their fears and hopes for end of life. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 14(2–3), 209–224. doi:10.1080/15524256.2018.1487364

- Leyerzapf, H., Visse, M., De Beer, A., & Abma, T. A. (2018). Gay-friendly elderly care: Creating space for sexual diversity in residential care by challenging the hetero norm. Ageing & Society, 38(2), 352–377. doi:10.1017/S0144686X16001045

- Logie, C. H., Lys, C. L., Dias, L., Schott, N., Zouboules, M. R., MacNeill, N., & Mackay, K. (2019). ”Automatic assumption of your gender, sexuality and sexual practices is also discrimination”: Exploring sexual healthcare experiences and recommendations among sexually and gender diverse persons in Arctic Canada. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1204–1213. doi:10.1111/hsc.12757

- Marhankova, J. H. (2019). Places of (in)visibility. LGB aging and the (im)possibilities of coming out to others. Journal of Aging Studies, 48, 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2018.11.002

- Murphy, Y. (2016). The marriage equality referendum 2015. Irish Political Studies, 31(2), 315–330. doi:10.1080/07907184.2016.1158162

- National Institute of Medicine. (2011). Later adulthood. [EPub]. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64800/#ch6.s1

- Neville, S. J., Adams, J., Bellamy, G., Boyd, M., & George, N. (2015). Perceptions towards lesbian, gay and bisexual people in residential care facilities: A qualitative study. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 10(1), 73–81. doi:10.1111/opn.12058

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2021). Sexual orientation, UK: 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/sexuality/bulletins/sexualidentityuk/2019

- Opening Doors. (2022). Pride in care. Retrieved from https://www.openingdoorslondon.org.uk/pride-in-care-quality-standard

- Osorio, R. (2017). Embodying truth: Sylvia Rivera’s elivery of parrhesia at the 1973 Christopher street liberation day rally. Rhetoric Review, 36(2), 151–163. doi:10.1080/07350198.2017.1282224

- Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(1), 47–53. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

- Pluye, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., & Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2009). A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(4), 529–546. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009

- Pocobello, R., El Sehity, T., Negrogno, L., Minervini, C., Guida, M., & Venerito, C. (2020). Comparison of a co-produced mental health service to traditional services: A co-produced mixed-methods cross-sectional study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(3), 460–475. doi:10.1111/inm.12681

- Putney, J. M., Keary, S., Hebert, N., Krinsky, L., & Halmo, R. (2018). ””Fear runs deep:” The anticipated needs of LGBT older adults in long-term care.” Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(8), 887–907. doi:10.1080/01634372.2018.1508109

- Ross, M. H., & Setchell, J. (2019). People who identify as LGBTIQ+ can experience assumptions, discomfort, some discrimination, and a lack of knowledge while attending physiotherapy: A survey. Journal of Physiotherapy, 65(2), 99–105. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2019.02.002

- Serpe, C. R., & Nadal, K. L. (2017). Perceptions of police: Experiences in the trans* community. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 29(3), 280–299. doi:10.1080/10538720.2017.1319777

- Sharek, D. B., McCann, E., Sheerin, F., Glacken, M., & Higgins, A. (2015). Older LGBT people’s experiences and concerns with healthcare professionals and services in Ireland. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 10(3), 230–240. doi:10.1111/opn.12078

- Simpson, P., Brown Wilson, C., Brown, L. J. E., Dickinson, T., & Horne, M. (2017). The challenges and opportunities in researching intimacy and sexuality in care homes accommodating older people: A feasibility study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(1), 127–137. doi:10.1111/jan.13080

- Simpson, P., Almack, K., & Walthery, P. (2018). ‘We treat them all the same’: The attitudes, knowledge and practices of staff concerning old/er lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans residents in care homes. Ageing & Society, 38(5), 869–899. doi:10.1017/S0144686X1600132X

- Sussman, T., Brotman, S., MacIntosh, H., Chamberland, L., MacDonnell, J., Daley, A., … Churchill, M. (2018). Supporting lesbian, gay, bisexual, & transgender inclusivity in long-term care homes: A Canadian perspective. Canadian Journal on Aging-Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 37(2), 121–132. doi:10.1017/S0714980818000077

- Villar, F., Serrat, R., Faba, J., & Celdran, M. (2015). Staff reactions toward lesbian, lay, or bisexual (LGB) people living in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) who actively disclose their sexual orientation. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(8), 1126–1143. doi:10.1080/00918369.2015.1021637

- Villar, F., Serrat, R., Celdran, M., Faba, J., Genover, M., & Martinez, T. (2019a). Staff perceptions of barriers that lesbian, gay and bisexual residents face in long-term care settings. Sexualities, 25(1–2), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719876808

- Villar, F., Serrat, R., Celdran, M., Faba, J., & Martinez, M. T. (2019b). Disclosing a LGB sexual identity when living in an elderly long-term care facility: Common and best practices. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(7), 970–988. doi:10.1080/00918369.2018.1486062

- Waling, A., Lyons, A., Alba, B., Minichiello, V., Barrett, C., Hughes, M., … Edmonds, S. (2019). Experiences and perceptions of residential and home care services among older lesbian women and gay men in Australia. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1251–1259. doi:10.1111/hsc.12760

- Westwood, S. (2016). ‘We see it as being heterosexualised, being put into a care home’: Gender, sexuality and housing/care preferences among older LGB individuals in the UK. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(6), E155–E163. doi:10.1111/hsc.12265

- Willis, P., Maegusuku-Hewett, T., Raithby, M., & Miles, P. (2016). Swimming upstream: The provision of inclusive care to older lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) adults in residential and nursing environments in Wales. Ageing & Society, 36(2), 282–306. doi:10.1017/S0144686X14001147

- Willis, P., Raithby, M., Maegusuku-Hewett, T., & Miles, P. (2017). ‘Everyday advocates’ for inclusive care? Perspectives on enhancing the provision of long-term care services for older lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in Wales. British Journal of Social Work, 47(2), 409–426.

- Willis, P., Almack, K., Hafford-Letchfield, T., Simpson, P., Billings, B., & Mall, N. (2018). Turning the co-production corner: Methodological reflections from an action research project to promote LGBT inclusion in care homes for older people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 695. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040695

- Women and Equalities Committee. (2019) Health and social care and LGBT communities. House of Commons. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmwomeq/94/94.pdf.