ABSTRACT

This article explores the contribution agent-based modeling (ABM) can make to the study of LGBTQ workplace inequalities and, conversely, how ABM can adapt to theoretical traditions integral to LGBTQ studies. It introduces an example LGBTQ workplace model, developed as part of the CILIA-LGBTQI+ project, to illustrate how ABM complements existing methods, can address methodological binarism and bridge macro and micro accounts within LGBTQ studies of the workplace. The model is intended as an important starting point in developing the role of ABM in LGBTQ research and for bridging qualitative- and quantitative-derived insights. Likewise, the article discusses some approaches for negotiating theoretical and methodological tensions identified when integrating queer and intersectional insight with ABM.

Introduction

This article provides an original contribution to knowledge by demonstrating how agent-based modeling (ABM)—a computational modeling methodology—can advance the intersectional study of LGBTQ lives. Building on previous work describing the fruitful application of both intersectionality and complexity theory (McGibbon & McPherson, Citation2011), it considers how ABM can facilitate an abductive approach to theory development whilst complimenting existing methods used within LGBTQ studies. As such, the article also proposes ABM as a rapprochement to methodological binarism within the field, exploring how it can be applied without losing sight of what is theoretically and methodologically integral to LGBTQ studies, namely intersectional and queer perspectives. Indeed, the article argues that a double-queer(y)ing needs to take place: one that further challenges methodological binarism in LGBTQ studies and one which simultaneously adapts the normative practices of ABM to acknowledge diversity and difference using insight from LGBTQ lives.

The article illustrates this important contribution through a discussion of ABM in relation to LGBTQ workplace research concerning inequalities. It begins by outlining methodological binarism within LGBTQ studies of the workplace and moves on to introduce ABM as a suitable abductive approach from complexity science. The article then draws upon an example ABM of LGBTQFootnote1 workplace inequalities and career progression, developed as part of a wider project exploring intersectional lifecourse inequalities of LGBTQI+ citizens in four European countries (CILIA-LGBTQI+), and discusses the ramifications of applying ABM to studies of LGBTQ in the workplace and LGBTQ research more broadly.

LGBTQ workplace studies and methodological binarism

In this paper we focus on two themes that stand out across recent scholarship focused on LGBTQ lives and discuss their use in workplace studies: (i) the cumulative insights afforded by intersectionality theory; and (ii) an apparent binary divide in methodological approaches (Kelemen & Rumens, Citation2016) and use of social categories more generally.

Since the early 2000s, many European countries began to expand equality legislation and localized policies to address workplace discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer (LGBTQ) people, including our own, the UK. However, these interventions have varied in their success, with studies documenting continued LGBTQ discrimination within UK labor markets (Bachmann & Gooch, Citation2018), differentiated career progression and earnings (Aksoy, Carpenter, & Frank, Citation2018), and lower levels of job satisfaction (Bayrakdar & King, Citation2021) than their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts. These studies also show that the experiences of workplaces differ significantly within LGBTQ communities. Bisexual and trans individuals have had limited recognition in policy initiatives aimed to improve LGBTQ employment experiences (Kőllen, Citation2013).

With its roots in black feminist scholarship (see, Combahee River Collective, Citation1997; Crenshaw, Citation1989), intersectionality has also been used in LGBTQ studies to call attention to diversity and avoid homogenization (Evans and Lépinard, Citation2020). It emphasizes the importance of not reifying gender identity or sexual orientation at the expense of other oppressive systems including race, social class and dis/ability.

Perhaps most crucially, intersectionality also rejects the idea of additive processes of discrimination (King, Citation2016), indicating instead the need for a more situated, nuanced approach that recognizes both structural inequality and agentic inter-actions shaping lived experience. While LGBTQ people who experience racialised, gendered, and hetero-cis-sexual workplaces face different challenges, a recent policy analysis of four European countries (Castro Varela and Bayramoğlu, Citation2020) highlights an absence of engagement with intersectionality within such policy domains. In this article, we draw on intersectional ideas that consider the experiences of LGBTQ individuals who are uniquely positioned in interlocking systems of exclusion and discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, and social class.

Whilst emphasizing such complexity, LGBTQ studies have tended to bifurcate and pivot around a quantitative and qualitative binary divide (Browne & Nash, Citation2010; Kelemen & Rumens, Citation2016). Research exploring labor market outcomes of LGBTQ individuals have advanced largely as two separate streams. On the one hand there is a rich, and ever-growing, literature using qualitative methods to explore LGBTFootnote2 labor market experiences through in-depth interviews with employees from different age groups and sectors. These studies document not only the negative treatment of LGBT individuals at their workplaces, but also some of the behavioral strategies adopted in attempt to negate its impact (Gray, Citation2013; Msibi, Citation2015). They also explore nuances in the social and professional interactions of LGBT individuals with their employers, colleagues, and support networks (Rumens, Citation2011). Conversely, a separate stream of studies explores the differentials in labor market outcomes by exploiting available quantitative data sources. These studies investigate the penalties (and in some cases rewards) in recruitment, career progression and earnings (Aksoy et al., Citation2018) and non-pecuniary outcomes such as job satisfaction (Bayrakdar & King, Citation2021)—albeit leaving much explanation (causal mechanisms) to speculation.

As such, this quantitative stream has only marginally engaged with intersectional variance in LGBTQ workplace experiences—instead favoring small numbers of discrete social categories for identifying statistically significant social differences. The priority is eloquent simplification of available data for producing testable hypotheses. Too many social categories, or non-discrete overlapping groups contingent on time and place, require too large a sample size to reach any significant or reliable conclusions (O’Connor, Bright, & Bruner, Citation2019). Thus, detail is often rejected as “random noise” obscuring statistical relationships (Chattoe-Brown, Citation2013). Whereas the qualitative stream, rooted in feminist and queer theoretical frames, champions subjective accounts and contextual detail—embracing these as the very substance of social research. Social categories need not be fixed or quantifiable but rather explored critically in relation to how they are constructed, performed and experienced within the heteronormative confines of workplace and labor market settings (Browne, Citation2010).

These two methodological streams appear to have developed separately and without much dialogue between one another—potentially to the detriment of each. The inclination to reduce complex social phenomena to neat quantifiable categories can come at the cost of insight and relevance (Chattoe-Brown, Citation2013). For example, a simple statistical model may fit a dataset, yet reveal little to nothing useful about society, or erase marginal cases as anomalies (Browne, Citation2007). Likewise, the qualitative inclination toward detail and subjective narratives can neglect much of the evidential criteria for making generalizations. Exclusively qualitative-derived claims of intersectionality theory risk being viewed by policymakers as overly analytic or trivial (O’Connor et al., Citation2019, p. 24) and, as such, contributes to the observed lack of investment in intersectionally-aware policy solutions (Castro Varela & Bayramoğlu, Citation2020).

Complexity and agent-based modeling

Responding to the call for pluralism is a growing movement within social and policy research advocating use of a wider set of methodological approaches—grouped together for their shared underpinnings in complexity science. This is accompanied by an emphasis on the study of social phenomena as complex adaptive systems (Byrne & Callaghan, Citation2014; McGibbon & McPherson, Citation2011). These are complex in so far as such systems are challenging to predict and comprise features such as interactions between heterogenous actors (agents), feedback between components, and non-linear path-dependent processes (Boehnertet al., Citation2018); and adaptive in that a system and its actors have capacity to change, or even learn, over time (Boehnert et al., Citation2018). Like intersectionality theory, complexity approaches explore social phenomena as more than a simple aggregation of composite parts, with emergent regularities irreducible from the interactions and self-organization between these parts.

The influence of complexity science’s methodological and theoretical frameworks has been felt across many domains of natural and social science, from health care and epidemiology to computational sociology, economics, and artificial intelligence (Gilbert & Troitzsch, Citation2005; McGibbon & McPherson, Citation2011). More recently, its uses for advancing LGBTQ health research have also been explored (Moore et al., Citation2021). However, its influence has been sporadic (Barbrook-Johnson, Castellani, Hills, Penn, & Gilbert, Citation2021). For some social science disciplines an emphasis on nuance, interactions, non-linearity and irreducibility is a dramatic and painful shift which involves challenging long-standing theory and methods. For others, these tendencies are already well-embedded and often already exist, simply going by different names (Anzola, Barbrook-Johnson, & Cano, Citation2017).

Agent-based modeling (ABM) is one such complexity approach. As a computational modeling methodology, ABM involves developing computer models to simulate and explore social and policy processes, such as those theorized to culminate in career inequalities. It has become increasingly popular over the last forty years (Barbrook-Johnson, Badham, & Gilbert, Citation2017; Gilbert & Troitzsch, Citation2005) with many examples in academic research, and a growing number in applied policy analysis (Gilbert, Ahrweiler, Barbrook-Johnson, Narasimhan, & Wilkinson, Citation2018). In keeping with its computational approach, ABM consists of three core components: inputs, processes, and outputs.

Inputs usually consist of existing data, such as relevant demographics and distributions. In the absence of such data, hypothetical parameters might be used instead and then calibrated, alongside testing an agent-based model’s “sensitivity” to changes in these parameters. Theory can be an equally important input, as can participatory input from stakeholders. Accordingly, the model itself forms the processes through which these inputs are then run. They are operationalizations of the very social processes, or theories, that the researcher(s) is interested in exploring—built by writing computer code to explicitly model (i) an environment, (ii) agents and (iii) interactions. Firstly, the virtual environment will usually represent some form of social space, whether geographical or a more abstract conceptual space, such as friendship networks or a job market. Secondly, this environment is inhabited by agents—autonomous decision-making entities representing people, such as LGBTQ citizens, groups, or organizations such as workplaces—who, thirdly, interact with each other and with their environment.

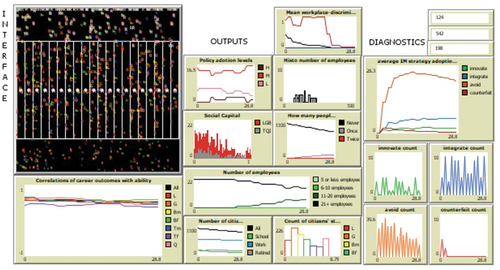

By simulating multiple agents interacting (according to theories) over time, behaviors unfold, and agents influence one another and their environment. A researcher can then explore any emergent properties or interesting phenomena happening within the model that were not directly written into it. These emergent patterns and behaviors can be recorded as model outputs; displayed in real-time on a model’s interface (see ) or exported into separate statistical analysis software for detailed exploration of multiple model runs and comparison between different parameters (see, “Model Results” section below). Typically, models are developed with different scenarios to be “run” and compared. These may represent different hypothetical futures, different policy interventions, or different theoretical assumptions. Rather than making point-predictions about the future, which is always a fruitless task in complex social systems (Gilbert et al., Citation2018), the purpose is to explore the influence of different mechanisms in the model and make broad comparisons between forecasts and scenarios. For models specifically designed with theoretical explication in mind, these comparisons are particularly useful for helping a researcher better understand the social processes, and refine the theories, underpinning the model itself (Poile & Safayeni, Citation2012).

Many authors have documented the value ABM offers to the social sciences, including Squazzoni (Citation2007), Chattoe-Brown (Citation2013), and Gilbert (Citation2020). However, there is often a divide between those who use ABM and those who do not. Johnson (Citation2015) situates it as one of the best methods to use when agent heterogeneity and interaction are core components of one’s theory—such as when heterogeneous agents influence one another directly (e.g. employer-employee or colleague interactions) or indirectly (e.g. competing for jobs), and when there is feedback between these interactions. There are typically three modes of use within the social sciences: (i) exploring theoretical questions and assumptions; (ii) performing some form of policy or intervention analysis (exploring “what-if” type questions); or (iii) as part of a participatory research process with stakeholders, where the model supports engagement by being developed or critiqued by stakeholders (Gilbert, Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2015).

Thought experiments and abductive reasoning

As such, rather than inductive or deductive, ABM has been described as a “third way” of doing social science—the generative approach (Epstein, Citation1999). Candidate causal explanations for a phenomenon are generated by implementing causal processes in a model and exploring their implications. In so doing, one can enhance traditional approaches by exploring the merits, inconsistencies, gaps, and deficiencies of a theory (Macal, Citation2009, p. 145), inform future data collection, or even produce a tool for teaching complex concepts to stakeholders (Barbrook-Johnson et al., Citation2017).

Perhaps most distinctively, phenomena of interest such as emergent inequalities are studied indirectly. A model is first built, analyzed, and then related back to reality. This is in quite stark contrast with traditional modeling approaches where data on a phenomenon is first collected and then summarized (or simplified as it were) into a model. As such, ABM can also be considered a method for abductive reasoning (see Elsenbroich, Kutz, & Sattler, Citation2006). Probable conclusions are reached based on what we know (or think we know) by simulating a proposed sequence of interactions. This is not so different to classic “thought experiments” within philosophy (Di Paolo, Noble, & Bullock, Citation2005) where one systematically follows a set of designated assumptions (consequents or antecedents) to their logical conclusions—learning more about these assumptions, and refining them, in the process. As computational thought experiments, ABMs simply facilitate simulation of more complex processes.

Bridging macro and micro accounts

It is this “third way” of doing social science that we suggest offers a rapprochement to methodological binarism apparent within LGBTQ workplace studies. ABM provides a particularly novel means of combining quantitative and qualitative insights. Moreover, it achieves this in an arguably more meaningfully way than some other “mixed methods” approaches, where all too often multiple methods are simply reported alongside one another in the same project (Chattoe-Brown, Citation2013).

Likewise, ABM addresses causation without limiting researchers to overly neat linear, statistically significant, or mathematically tractable, ways of thinking about cause and effect. By facilitating the modeling of non-linear and bi-directional processes, a researcher can explicitly link micro and macro accounts within one’s theories. To illustrate the argument being developed in this article further, a typical structural narrative may describe how a workplace environment impacts the conditions, and in-turn behaviors, of LGBTQ employees. If an LGBTQ employee regularly experiences discrimination at work, this may impact their career outcomes as well as influence certain behaviors, such as finding a new employer. Additionally, other macro structural factors, such as labor markets and workplace policies, may limit or enhance their behavioral opportunities. However, these accounts only tell half the story. A researcher may also be interested in how the agency of LGBTQ employees in response to discrimination can feedback, collectively, on their workplace environment or labor markets. By positioning individual agents as the primary unit of analysis, ABMs explore exactly these types of bi-directional processes. Researchers can explore the logical, and perhaps not so predictable, conclusions of what happens when one combines these structural and agentic accounts within the same model.

Having outlined some of the most apparent uses of ABM, it is also appropriate to explore how these align with current developments in LGBTQ workplace studies and ways in which LGBTQ research can shape developments in ABM methodology.

An intersectionality-consistent method?

ABMs are ideal for representing heterogeneity (Johnson, Citation2015; Gilbert et al., Citation2018). Researchers can distribute multiple characteristics among large numbers of agents and simulate these over long periods of time. We can thus explore populations, subpopulations and intersections usually considered too small for statistical significance and ignored (or glossed over) by other studies (Chattoe-Brown, Citation2013). In turn, this also enables researchers to approach social categories, like gender, sexuality, ethnicity and social class, in much more sophisticated ways than quantitative approaches do. Specifically, one can begin to explore complexity in how discrimination and inequality impact individuals at the intersections of these social categories across the lifecourse.

Taylor (Citation2007) demonstrates ways in which class and sexuality can intersect in the lives of working-class lesbian women, whilst Pedulla (Citation2014) proposes how intersections of race and sexuality may moderate each other’s effect on earnings in unique and perhaps unexpected ways. This is a level of complexity embraced by intersectional and queer perspectives, and yet challenging to traditional statistical analyses. However, ABM can embrace these non-linear relationships and complex interactions. There is a strong theoretical consistency between intersectionality theory and complex adaptive systems approaches (McGibbon & McPherson, Citation2011).

Likewise, ABMs can explicitly draw attention to the impact of such complex approaches to social categories. Chattoe-Brown (Citation2013, p. 7.1) suggests:

As with debates between qualitative and quantitative researchers, those who draw attention to detail need to [be able to] show not just that there is detail but that it has effects (in terms of quantitative outcomes for example.) It is not clear this can be done without simulation.

Here, ABM can directly help to explore, demonstrate, and defend the importance of certain details of a theory that might otherwise be left out of a model. O’Connor et al. (Citation2019), for example, use their model to demonstrate how intersectional inequality between social groups can arise in the cultural emergence of bargaining norms even when all social categories have identical preferences and abilities. In so doing, they directly contribute to calls for intersectional considerations within the wider methodological literature.

Nonetheless, with the exception of O’Connor et al. (Citation2019), there has been little attempt to forge a bridge between intersectionality theory and ABMs representations of specific social systems, such as labor markets—let alone LGBTQ experiences within these systems. This may appear slightly peculiar for a method revered in its capacity to represent heterogeneity (Johnson, Citation2015;Gilbert et al., Citation2018). However, as our reflections on designing an LGBTQ workplace model suggests (see below), this may be due to a preoccupation with simplicity among traditional modelers and limitations in modeling critical and post-structural accounts of social categories. For the field of LGBTQ studies, specifically, we need to consider ABM’s compatibility with “queer” perspectives.

A “queer(able)” method?

Whilst arguably consistent with intersectional perspectives, the extent to which ABM is amenable to “queering” rests upon what we mean by “queer” and what we consider the minimal requirements for a “queer methodology.” Perhaps most superficially, queering can describe the application of a method to non-normative subjects, visibilising sexual/gendered lives and practices often simplified out of larger population models (Browne, Citation2010). ABM is suited to this kind of research since LGBTQ agents can be represented in name, demographic and behavioral data generated directly from sexual and gender minority subjects, alongside structural conditions in which they interact.

Yet this misses the critical and subversive capacity of a queer lens (Giffney, Citation2004, p. 73) to challenge normative identities and deconstruct normative research. LGBTQ studies have long conceded that categories such as homosexual, heterosexual and other identities are historically- and culturally-specific social productions with numerous theorists having focused specifically on exposing their fluid, performative and contingent qualities (Jackson & Scott, Citation2010). Moreover, Browne (Citation2007) describes how research on LGBTQ populations can often (re)create rather than objectively measure such social categories. Queer identities and lives can be further marginalized or subsumed within normative lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans (etc.) categories. For LGBTQ researchers, this is a process she describes as akin to selling one’s “queer (academic) soul” (Browne, Citation2007, p. 3.3). Likewise, such research can incorporate its own plethora of homo-normalizations that privilege some lesbian and gay voices and norms above others (Browne, Citation2010), such as the rarely contested racialized, gendered, and classed discourses of “the pink pound” and “the educated gay” (Badgett, Citation2003).

ABM, however, can operationalise social categories as fluid and contingent upon other dynamics within a model. Existing studies have already utilized ABM to explore the historic and cultural emergence of normative identity categories (see, Lustick, Citation2000; Rousseau & van der Veen, Citation2005). Nonetheless, this degree of complexity in representing social categories requires making trade-offs elsewhere if a model is to remain analyzable (Gilbert & Troitzsch, Citation2005). For example, models directly exploring the emergence of such categories tend to be far more abstract and simpler in their representation of the social settings in which they occur. Such a trade-off may not be as appropriate when exploring processes of discrimination within specific settings, such as workplaces—it is the emergence of inequality, rather than the social categories, in which we are primarily interested. This does not mean to say that a queer lens cannot be applied to add levels of complexity to social categories used within a model. Deconstruction could be substituted for analytically meaningful complexification of social categories.

Thus far the article has introduced ABM as a complexity method and possible rapprochement to methodological binarism within areas of LGBTQ research, such as workplace studies, and as means for integrating, and generating new, theoretical insights. Consideration has also been given to its compatibility with intersectional and queer perspectives that are important in LGBTQ research. The following section of the article discusses a specific exploratory ABM of LGBTQ workplace inequalities in order to illustrate the efficacy of such an application.

CILIA-LGBTQ: An example agent-based model

This section of the article begins by summarizing an example model,Footnote3 developed as part of the CILIA-LGBTQI+ project, and the relevance of the output/results it generates. The proceeding discussion then reflects on how such a model can contribute to future developments in LGBTQ research, as well as on some of the conceptual/methodological challenges encountered when developing the model to meaningfully incorporate intersectional and queer insights.

The model explores the emergence and dynamics of workplace inequalities among LGBTQ employees. It includes the impact of several mediating factors: social capital; different types of policy intervention aimed at workplace equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI); and LGBTQ people’s behavioral strategies in response to discrimination. The model was inspired by Takács and Squazzoni’s (Citation2015) ABM of labor market inequalities for helping design a simple idealized job market. We identified only one existing ABM exploring consequences of sexual orientation in the workplace. Bonaventura and Biondo (Citation2016) used ABM to simulate the effects of sexual orientation disclosure on unemployment rates, job satisfaction and job segregation in the US, finding the presence of more “out” workers to increase job satisfaction of the overall workforce. However, whilst useful, their model does not measure career inequalities per se and only explores simple binary attributes of homosexual/heterosexual and disclosure/non-disclosure. Likewise, rates of sexual orientation disclosure in their model are operationalized as a set parameter, rather than an emergent property of workplace dynamics itself.

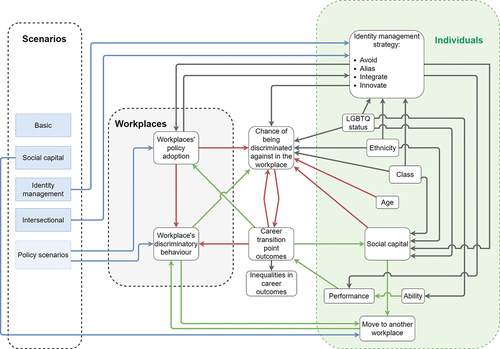

The CILIA-LGBTQ model is built in NetLogo (Wilensky, Citation1999), a free and open-source software environment developed for building ABMs, with an active and large research user community. There are two distinct types of agent represented in the model, each with its own sets of attributes and behaviours: LGBTQ citizens and workplaces. outlines the logic of the model, illustrating the bidirectional interactions between citizen and workplace agents.

Figure 2. Overview of CILIA-LGBTQ model logic. Boxes represent agent characteristics or model outcomes, and arrows the direction of influence between them. Blue arrows indicate where scenarios change model dynamics, green indicate a positive influence, red a negative influence, and grey non-linear or co-dependent influences. The diagram shows feedback between individual agents' attributes and workplaces' attributes - and how they combine to affect i) career transitions of individuals, and ii) discriminatory cultures within the workplace.

The LGBTQ citizens each have an age (in years), a class (working, middle), ethnicity (white, non-white) and an LGBTQ status (L, G, Bm, Bf, Tm, Tf or Q) which informs initial distributions for other relevant attributes, such as social capital (score between 0–1), ability (score between 0–1), and ultimately their career outcomes (score between 0–1). In later model scenarios (see below) LGBTQ status, class and ethnicity also impact the necessary conditions and consequences for some agent behaviors. Meanwhile, the workplaces each have an underlying discriminatory culture (score between 0–1), and adoption of protective policies (e.g. HR policies dealing with discrimination, values can be high, medium, or low). Realistic distributions for these citizen and workplace values are setup using data for England from the UK Longitudinal Household Survey Wave 3 (ISER, Citation2020) and Workplace Employment Relations Study 2011 wave (NIESR, Citation2015).

At the centre of the model, LGBTQ citizens' primary behaviour is to age and transition through their careers, represented in three key life stages: (i) a school-to-work transition; (ii) a mid-career transition; and (iii) a transition-into-retirement. They are also given the opportunity to move workplaces if their current workplace is particularly discriminatory. When an agent reaches a transition stage, their transition scores are influenced by any previous transitions (or ability, in the case of a school-to-work transition). These scores then receive penalties in accordance with their LGBTQ status, ethnicity and class, as well as the discrimination and policy adoption of their workplaces. The value of their final score determines whether their current career outcomes exceed, match, or fall short of their ability.

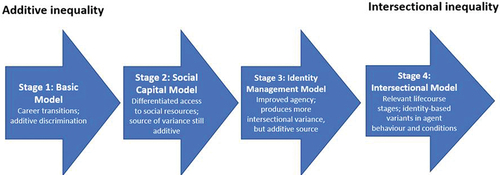

Workplaces’ discriminatory cultures and any protective policy adoption can also change over time through influence from their workforce (i.e. if a workplace has relatively high numbers of visible LGBTQ employees, it can become less discriminatory and/or more protective, relative to others). From here different types of policy-based interventions can be implemented and explored according to their impact on model dynamics. However, the scenarios of interest for this article are exclusively theory-based and outlined in below:

Table 1. Model scenarios overview.

As outlines, whilst not part of the “basic” model (scenario 1), social capital and identity management strategies are also included in later scenarios. The “social capital” model (scenario 2) introduces social capital as an unevenly distributed value (score between 0–1) among citizens, used when seeking less discriminatory, or more protective, workplaces. Meanwhile, the “identity management” model (scenario 3) further expands the utility of social capital by introducing the option of four identity management strategies for the LGBTQ citizens. Each is contingent on the citizen’s own attributes, as well as their workplace. For example, if they work within a particularly discriminatory workplace and have little social capital, they may choose to (i) avoid disclosure of their identity at work or even (ii) create a cisgender/heterosexual alias for themselves. Likewise, with high enough social capital and/or low enough risk of discrimination, they may choose to (iii) integrate their sexual/gender identity into their workplace environment via disclosure, or even (iv) innovate a professional identity around their sexual/gender identity. The adopted strategy subsequently influences the individual citizen’s future experiences of discrimination, performance at work and access to social capital, as well as indirectly influencing that of their LGBTQ colleagues by influencing the discriminatory culture and policy adoption of their workplace.

These four strategies, the conditions under which they are adopted and their consequences, are informed by lifecourse interviews with LGBTQ respondentsFootnote4 from the wider CILIA-LGBTQI+ project and existing conceptual models of LGBTQ identity management (see Button, Citation2004; Gray, Citation2013; Msibi, Citation2015). The final “intersectional” model (scenario 4) proceeds to adjust the conditions and consequences of these strategies according to the specific sexual/gender identity, ethnicity and social class of the citizen. These variants were informed exclusively using qualitative accounts from the aforementioned lifecourse interviews.Footnote5

Model results

Having set the ABM up in this way, the primary output measure is the correlation coefficient between LGBTQ citizens’ ability and career outcome (i.e. one measure of discrimination) broken down by gender identity and sexual orientation within the umbrella LGBTQ. Also presented are the mean, minimum and maximum underlying discriminatory culture of workplaces over time. The following results are kept brief for the purpose of illustrating types of dynamics that models, such as this one, can generate and their relevance for intersectional analyses. A more in-depth discussion or analysis of causal explanations underlying these results is outside the scope of this article but this is not to say that causal relationships are completely ignored. We do not discuss underlying mechanisms at length as the paper's main aim is to illustrate the utility of using ABM in LGBTQ workplace studies that incorporate insight from intersectional and queer theories.

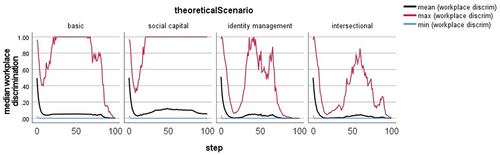

As illustrates each theoretical scenario has a significant impact on discriminatory workplace cultures. Whilst the minimum (min.) value stays consistent across all four scenarios, mean values are highest when social capital is distributed among citizens (panel 2). Moreover, this is when the most discriminatory workplaces (max.) maintain consistently high discriminatory attitudes. Once identity management dynamics (panel 3) are introduced to the model, we see both a reduction in the discrimination of the most discriminatory workplaces, as well as slight reductions in the mean. Once we introduce intersectional variation to the conditions and consequences of identity management strategies (panel 4), discrimination reduces further and forms a lower peak.

Figure 3. Workplace discrimination | 3,000 citizens | 320 model runs | The plot shows the average mean, min and max discriminatory attitudes of workplaces over 100 timesteps (x-axis). Each panel plots these results for different theoretical scenarios (from left-to-right: basic, social capital, identity management and intersectional).

These results suggest: (i) social capital (as implemented in the model) reinforces inequality among LGBTQ citizens, allowing those with it to prosper at the cost of those without, and allows the most discriminatory workplaces to remain unchanged, as LGBTQ citizens with enough social capital leave them; and (ii) collectively, identity management practices of individual agents (as implemented in the model) may have marginal impact on the average workplace, but can significantly moderate the most discriminatory workplace cultures over time. It only takes the presence of one or two LGBTQ citizens disclosing their gender/sexual identity (innovate or integrate) to reduce extremely high discriminatory cultures within a workplace, resulting in positive feedback as more colleagues are then willing to disclose. Workplaces with already low discriminatory cultures have less to benefit from additional disclosures.

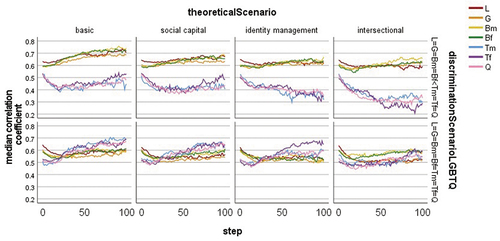

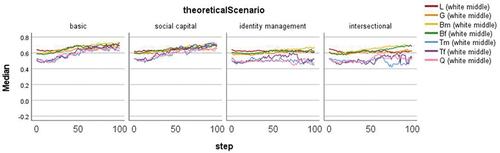

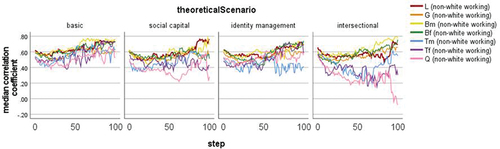

However, our model demonstrates how this reduction in workplace discrimination over time may not necessarily correspond with greater career outcome equality for LGBTQ citizens, as exemplified in (below). The correlation between LGBTQ agents’ ability and career outcomes only marginally improve for those under the basic and social capital scenarios, whilst remaining fairly consistent over time under the identity management and intersectional scenarios. However, there are important intersectional differences. For TQ citizens, in particular, this trajectory is dependent on initial levels of discrimination faced by each LGBTQ identity category. The bottom panel of (below) displays results for model runs where LGBTQ citizens all experience the same levels of discrimination whereas, in the top panel, TQ citizens are exposed to higher levels of discrimination than cisgender LGB citizens. When exposed to the same levels of discrimination, TQ citizens’ career outcomes gradually correlate more with their ability over time under all scenarios (though to varying extents). However, when exposed to higher levels of discrimination than their LGB counterparts, the correlation for TQ citizens remains fairly stable over time under basic and social capital scenarios. Moreover, this correlation significantly reduces over time under identity management and intersectional scenarios, resulting in increased inequality between TQ and LGB status citizens.

Figure 4. LGBTQ Inequality | 3,000 citizens | 320 model runs | The plot shows the average correlation coefficient between ability and career outcome for each LGBTQ status over 100 timesteps (x axis). Each vertical panel plots results for different theoretical scenarios (from left-to-right: basic, social capital, identity management and intersectional) whilst horizontal panels compare initial levels of discrimination faced by each LGBTQ status (bottom = equal, top = T and Q exposed to higher levels).

These results suggest: (i) slight differences in initial distributions for discrimination at the beginning of a simulation, such as those arising from cisheteronormative culture and institutions beyond the workplace, set agents on significantly different trajectories once accounting for how people manage their identity under such conditions; and (ii) qualitative differences (as observed from lifecourse interviews) regarding conditions and consequences of identity management for each specific LGBTQ identity can further amplify those trajectories. Nonetheless, these results still only reflect dynamics of a singular social category (LGBTQ status).

If we disaggregate further by exploring the intersections of ethnicity and social class within and between LGBTQ citizens, then trajectories for each respective scenario are quite different. For example, as (above) and (below) illustrate, white middle-class TQ citizens’ career outcome and ability correlate significantly more over time than that of nonwhite working-class TQ citizens’ () under basic and social capital scenarios. Likewise, correlations for white, middle-class citizens (regardless of LGBTQ status) remain higher than 0.4 under all theoretical scenarios and either increase or remain consistent over time. Nonwhite working-class TQ citizens, however, do not tend to experience significant increases over time and, under the intersectional scenario, can experience significant decreases—with nonwhite, working-class Q citizens even reaching a negative correlation where high ability (albeit weakly) predicts lower career outcomes. Furthermore, under the intersectional scenario, inequalities emerge between white, middle-class LG and B citizens (, panel 4) that do not emerge between nonwhite working-class LG and B citizens (, panel 4).

Figure 5. White, middle class LGBTQ inequality | 3,000 citizens | 320 model runs | The plot shows the average correlation coefficient between ability and career outcome for each LGBTQ status of white, middle class citizens over 100 timesteps (x axis). Each panel plots results for different theoretical scenarios (from left-to-right: basic, social capital, identity management and intersectional).

Figure 6. nonwhite, working class LGBTQ inequality | 3,000 citizens | 320 model runs | The plot shows the average correlation coefficient between ability and career outcome for each LGBTQ status of nonwhite, working class citizens over 100 timesteps (x axis). Each panel plots results for different theoretical scenarios (from left-to-right: basic, social capital, identity management and intersectional).

These results suggest: (i) intersections of ethnicity and social class are relevant in understanding emergent LGBTQ inequalities under all theoretical scenarios, particularly as we start accounting for increased agency (i.e. identity management and intersectional scenarios); and (ii) comparing trajectories between LGBTQ citizens by ethnicity and social class ( and ) can reveal significantly different dynamics to that of aggregate LGBTQ categories ().

Discussion

Though condensed, the results discussed in the above section of this article illustrate the utility of ABM to observe non-linear relationships as well as plausible underlying causal mechanisms. For example, we observe positive feedback between sexual/gender identity disclosure and changes in discriminatory attitudes of workplaces over time—including the contexts in which such dynamics were most prominent. Here, disclosure appears to have a much larger cumulative effect on the most discriminatory workplaces, with diminishing returns among already inclusive workplaces. We also observe the direct impact of different theoretical scenarios (as implemented) on emergent inequalities, and why they have the impact that they do, by tracing their causal mechanisms. Likewise, any “unusual” results running counter to empirically observed phenomena can be used to scrutinize and refine the theories that have been implemented (Poile & Safayeni, Citation2012). A theory may need complete reassessing, or only adjustments made to one or two minor assumptions, to produce more intuitive or empirically sound results. As such, this abductive approach (Elsenbroich et al., Citation2006) facilitates an iterative process between validation and theory development.

Furthermore, the CILIA-LGBTQ ABM suggests a quantitative impact of qualitatively derived details (Chattoe-Brown, Citation2013) extracted from the project’s lifecourse interviews. The minor intersectional variations in how we theorize identity management practices to operate by LGBTQ status, ethnicity and social class do appear to affect our measure of career outcome (in)equality when disaggregated and compared alongside one another. The results also highlight the relevance of initial levels of discrimination experienced by each intersection. Variations in identity management practices have a larger impact on career outcome trajectories the larger the initial levels of discrimination each intersection is subjected to (i.e. structural sources of LGBTQ, racial and class inequality beyond the workplace). Here, the ABM supports existing research about the relevance of intersectional identities in moderating the effectiveness of workplace policies (Colgan, Citation1989). It also has propensity to enhance traditional methods by illustrating possible contexts in which these dynamics are most relevant (Macal, Citation2009) and, as such, should be useful for informing future empirical studies and data collection (Barbrook-Johnson et al., Citation2017).

The remainder of this discussion section of the article considers the ramifications of the CILIA-LGBTQ ABM, and insights gained from operationalizing it, for exploration of LGBTQ workplace inequalities and LGBTQ studies more broadly. These include: negotiating data limitations, integrating intersectionality with model purpose, increasing complexity of the model incrementally, and negotiating normative assumptions with “queer moments.”

An often-overlooked value of ABM is simultaneously a common criticism afforded to them—they are regularly data-hungry. The process of building an ABM makes very clear what data is available, how usable it is, and where there are gaps, such as the lack of existing measures for workplace discrimination as well as the shortage of data for each intersection-ed LGBTQ category. In the process, generating novel demands for data and informing future data collection efforts (Barbrook-Johnson et al., Citation2017). Building the CILIA-LGBTQ ABM has demonstrated that, in the UK at least, there is not enough publicly available data on people who identify as trans or queer in relation to labor market characteristics. To accommodate this, extra assumptions had to be made about them, such as levels of access to social capital, compared to other groups where data was sufficient. Furthermore, though initially included within the model, a complete absence of relevant data on intersex populations meant tentatively removing intersex agents from the model altogether. This is problematic, but points to important issues. Although limited by shortage of data, the CILIA-LGBTQ model generates new demand, and recommendations, for policy-relevant workplace data collection (qualitative and quantitative) of under-researched populations, such as trans, queer and intersex.

Nonetheless, such an application is not without implications. The mandate for inclusivity, representation, and intersectionality within LGBTQ studies has potential to be in direct opposition with a core axiom of modeling (of all types)—that all else being equal, a simpler, more abstract model is better than a more complicated one (Gilbert, Citation2020). This is akin to the concept of Occam’s razor (i.e. choose an explanation with the fewest assumptions). However, it also reflects a pragmatism and desire for elegance in modeling, in which simpler models are understood as easier to understand and analyze, are less computationally demanding, and more elegant (Gilbert, Citation2020). Simplicity is seen to represent clarity and neatness of thought. Sun et al. (Citation2016) draw a useful distinction here between model complexity, describing the behaviors of a model, and model complicatedness, pertaining to level of detail in a model's construction.

This poses a challenge for developing models that adopt an intercategorical approach where the subject is multigroup and the analysis systemically comparative (McCall, Citation2009). The categorical space becomes increasingly complex with the addition of each analytic category. The CILIA-LGBTQ model’s use of seven sexual/gender categories (L/G/Bm/Bf/Tm/Tf/Q) alongside two social class (working/middle) and ethnicity (white/nonwhite) categories amounts to 28 unique intersections to explore. Inclusion of just one more social category (even simplified to a binary, such as abled/disabled) would increase these intersections to 56. Combined with the four theoretical scenarios (see, ), there are already 224 sets of results and underlying causal mechanisms to interpret before even considering their sensitivity within the parameter space of any uncertain values.

However, the maxim of simplicity does not go entirely unchallenged within ABM research communities. There are ongoing debates between those who support a “KISS” (“keep it simple stupid”) approach to modeling and those who support “KIDS” (“keep it descriptive stupid”) or “EROS” (“enhancing realism of simulation”) approaches (see Jager, Citation2017)—i.e. more detailed or complicated models. This debate is relatively nuanced and lengthy (see Edmonds & Moss, Citation2006), but tends to reaffirm a model’s purpose as the decisive factor. For example, Sun et al. (Citation2016, abstract) contend that models should be constructed ”as simple as possible but as complicated as necessary” in accordance with predefined research questions. Yet, despite scope for pragmatism, there remains widespread and often unquestioned drive for simpler models which can inadvertently discourage intersectional applications of ABM.

Meanwhile, owing to a strong qualitative tradition and rich focus on context, LGBTQ studies have embraced intersectional detail. This means, when building an ABM for LGBTQ research, we may wish to include all sorts of additional parameters for people and/or contexts. Using our model again, we might consider further increasing complexity by adding different types of workplace (i.e. sector, location) important to labor market dynamics and experiences of discrimination. However, with so many possibilities, a line needs to be drawn somewhere irrespective of one’s take on the KISS-KIDS-EROS debate. There is little value in a model that is just as complex as the real world (Gilbert & Troitzsch, Citation2005), and a tension in reconciling between competing forces to make a model simple and data-driven whilst also inclusive and intersectional. Making design decisions about what to include/exclude from a model is an art, not a science and, as ever, should be driven by a model’s purpose. If a researcher is to complicate a model by including multiple social categories, then intersectionality should be an explicit component of the research purpose, rather than simply added for the sake of detail and realism.

Another issue sidestepped until now is whether, when modeling LGBTQ people in any setting, we should also model the wider cisgender and heterosexual population alongside them (as in Bonaventura & Biondo, Citation2016). Their inclusion makes perfect sense when considering how the behaviors and situations we model are likely impacted by them. However, with the LGBTQ population estimated at only ~3% of the total English population (Van Kampen, Fornasiero, Lee, & Husk, Citation1999), proportional inclusion of cishetero agents (in excess of the 3,000 LGBTQ agents) means an exponential rise in both complexity of the model and weight of computation required to run it. Excluding the cishetero population thus becomes an appealing simplification, and indeed, one the CILIA-LGBTQ model makes. Workplaces in the model, with their varying discriminatory cultures, serve as substitutes for an otherwise much larger number of cishetero colleagues. In practice, decisions need to be made about how important direct interactions between LGBTQ and cishetero agents are for any particular model. If such interactions are genuinely core to a research question and model purpose, they will likely need including. Otherwise, considering cost to simplicity and increased computational weight, their omission is recommended.

Alongside questions of inclusion, diversity in the actual behavioral rules of agents also need consideration. Representing multiple intersecting identities with varied attribute distributions (e.g. social capital) is one thing, but more meaningful representation is only reached by considering diversity in behavioral rules, and their consequences, for different categories of agent. For example, in addition to lower social capital, BAME trans citizens may not respond to workplace discrimination, draw upon social capital, or manage their identity in the exact same way as white LGB colleagues. Nonetheless, applying such a rich definition of diversity also comes at a cost to simplicity. Decisions about depth (rather than just breadth) of representation required from a model also need resolving. Do we want to prioritize (a) a diversity in type of agent with little diversity in behavioral rules, or (b) a diversity in behavioral rules with more restricted diversity in agent type? To have both arguably stretches the reconciliation between simplicity and representation so far as to break it.

However, one way in which this reconciliation can be maintained is by adopting a stepwise or modular approach (Sun et al., Citation2016. As mentioned, ABMs allow detailed exploration of the workings behind a mechanism or theory. A researcher can implement it, push and pull at it, change parameters and settings, change its contexts, and explore how it reacts (Gilbert, Citation2020). Accordingly, additional components can be added or removed to extend, or simplify, a theory whilst the researcher abductively compares outcomes of these different implementations. This is what the CILIA-LGBTQ model achieves by comparing between incrementally complex, as opposed to entirely separate, theoretical scenarios (see ).

Figure 7. Incremental complexity from “simple” additive model of LGBTQ workplace inequality to complex intersectional model of inequality and agency.

The model was developed iteratively in four distinct stages and according to complexity of the theoretical scenarios to be explored—each progressively more meaningful in their application of intersectionality. For example, whilst the second and third stages (scenarios 2–3) increase intersectional variance in career outcomes (see and ) by building on a “basic” additive model, the mechanism behind this variance remains only the cumulative impact of initial discrimination and social capital distributions. As such, any emergent variation among agents can also be interpreted as an amalgamation of coded interactions within the model. This does not capture the central tenets of an intersectional analysis, which rejects overly simplified additive models of (in)equality (King, Citation2016). It assumes that identity management and utility of social capital is qualitatively the same for all LGBTQ citizens and regardless of intersecting identities. This assumption mirrors earlier criticisms of homo-normalizations in LGBTQ research (Badgett, Citation2003; Browne, Citation2010) and is inconsistent with qualitative findings from the wider project—justifying a fourth iteration of the model (scenario 4). Ensuring that emergent behaviors of simpler iterations were sufficiently understood before incrementing complexity with each new iteration, enabled us to systematically manage the complexity of the final intersectional model. This approach was key to exploring plausible macro-level impacts of the qualitative details important to LGBTQ studies of the workplace.

Finally, returning to Browne’s (Citation2007) concession about quantifying social categories being akin to selling one’s queer academic soul, the CILIA-LGBTQ ABM arguably does precisely this. Relying on discrete sexual/gender categories (L/G/Bm/Bf/Tm/Tf/Q) (re)creates them and ignores many of the fluid and contingent identities apparent from the wider CILIA-LGBTQI+ project and existing scholarship (Jackson & Scott, Citation2010). Summarizing an array of marginal identities as “Q” was useful for statistical significance and feeding existing quantitative data into the model, but nonetheless homogenized and fundamentally de-queered them. Similarly, a complete deconstruction of categorical information dismisses any means of simplification needed for operationalizing complex social theories and processes into a computational model. Thus, a wholly deconstructive queer approach may be considered outside the scope of ABM.

However, queer(y)ing also encompasses a much broader interrogation of cis/heteronormative assumptions (Giffney, Citation2005). Browne’s (Citation2010) interrogation of queer quantification for the 2011 UK census demonstrates how anti-normative and disruptive moments can also feature in the formation of quantitative categories. Rather than stable and permanent, she contends that data and categories “can be redefined, reused and reassert diverse views that take account of diverse social realities” (Citation2010, p. 248). Though not entirely disruptive once recuperated and solidified into the final product, these “queer moments” (as Browne coins them) are nonetheless valuable for contesting and making visible normative assumptions at various stages of the research process. This is an area where ABM research has scope for integrating queer insight. ABM’s particularly iterative nature, alongside need for precision when translating conceptual models and theory to code, regularly illuminates specificity gaps. Such gaps force modelers to make what is often termed “reasonable assumptions” in order to fill them (Poile & Safayeni, Citation2012). These can be simple technical assumptions required to satisfy constraints of the computational language (e.g. what arithmetic operator to use) or, more significantly, theoretical assumptions required to supplement any underspecified aspect of a theory. Ideally these are made explicit and justified within a model specification but, in practice, often go unacknowledged (Railsback & Grimm, Citation2012). Moreover, the very concept of “reasonable assumption” suggests deferring to normative categories. “Queer moments” are thus valuable within ABM design to disrupt what might otherwise appear a reasonable assumption to a modeler.

Crucially, unlike quantitative approaches where normative categories become fixed in research design at an early stage, the outcomes of small changes to an ABM’s assumptions can be explored directly with relative ease. Researchers can reconfigure a model again and again, reset parameters, as well as reformulate assumptions and rules of interaction between agents. As with the theoretical scenarios discussed above, ABMs provide researchers the opportunity to test alternative theoretical assumptions and categories. Thus, ABM’s propensity for reformulation and scenario testing, in tandem with space provided for “queer moments,” can facilitate direct exploration, comparison and documenting of the system-level implications of any normative vs. queer assumptions (so long as these assumptions are identified in the first place). We recommend deferring to ”real” queer lives where possible throughout the modeling process, whether through participatory modeling, exploring lifecourse interviews with LGBTQ subjects, or ensuring sufficient diversity within our project teams and modelling community.

Conclusion

Using an example model of LGBTQ workplace inequality, this article has explored the contribution ABM can make to the study of LGBTQ lives, and conversely, how the theory and traditions of LGBTQ studies can be meaningfully represented within an ABM. The example model demonstrates how methodological binarism (Browne & Nash, Citation2010; Kelemen & Rumens, Citation2016) within LGBTQ studies of the workplace can be addressed by combining qualitative and quantitative data for an abductive exploration of emergent inequalties. It also exemplifies how such models can contribute to calls for intersectionally-aware policy making (Castro Varela & Bayramoğlu, Citation2020) by demonstrating non-trivial, quantitative impact of smaller, qualitatively derived intersectional details in one’s theory (Chattoe-Brown, Citation2013; O’Connor et al., Citation2019).

However, whilst reaffirming the theoretical consistency between intersectionality theory and complex adaptive system approaches (McGibbon & McPherson, Citation2011), this article has also highlighted some tensions when synthesizing queer and intersectional perspectives with ABM. Namely, limitations in dealing with the anti-categorical (McCall, Citation2009) and managing the exponential complexity of an inter-categorical approach. Suggestions for negotiating these tensions, such as (i) integrating intersectionality with model purpose, (ii) incrementing complexity through a stepwise design, and (iii) directly comparing queer vs. normative assumptions, have also been addressed.

The future value of ABM within LGBTQ research is almost certainly in complementing existing methods and theory, not replacing them (Barbrook-Johnson et al., Citation2017; Macal, Citation2009). Skepticism and wariness of “modelling” or “quantification” should be welcomed and challenged, as with any approach that requires making normative assumptions (Poile & Safayeni, Citation2012). Conscious effort in challenging these assumptions when designing a model—applying “queer moments” (Browne, Citation2010)—can not only draw research in unanticipated directions, but also visually illustrate the very real impact such assumptions have on theory we develop and data we collect (Chattoe-Brown, Citation2013). Recent calls for more detailed/complex models (Jager, Citation2017) reflect a growing, yet still rather sporadic (Barbrook-Johnson et al., Citation2021), interest in ABM from a wider range of disciplines. As such, uptake of ABM within LGBTQ studies should accompany a more pragmatic stance toward established modeling axioms, such as simplicity, as methodological conventions adapt to facilitate the field’s existing traditions of inclusivity, representation, and intersectionality.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.9 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2106464

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The model was originally built to represent LGBTQ and “I” agents. However, due to no existing data on intersex labor market experiences, “I” was omitted from the model.

2. We note here the concerning dearth of studies addressing trans, queer, and particularly intersex (TQI+) experiences in the labor market.

3. As this ABM is presented for exemplary purposes only, rather than for empirical purposes, the summary is kept brief and, as such, is not comprehensive. A more detailed description of the model, along with pseudo-code and links to the ABM itself, is presented in the CILIA-LGBTQ specification sheet, accessible from CoMSES Computational Model Library.

4. The lifecourse interviews, with (N = 48) LGBTQI+ respondents across England, were all conducted between June 2019 and March 2020 as part of the wider CILIA-LGBTQI+ project. They covered respondents’ lives, identities, past experiences, experiences of discrimination and inequalities, as well as thoughts about the future.

5. For a more comprehensive summary of the dynamics represented in each scenario and how they were operationalized, see the CILIA-LGBTQ model specification accessible from CoMSES Computational Model Library.

References

- Aksoy, C. G., Carpenter, C. S., & Frank, J. (2018). Sexual orientation and earnings: New evidence from the United Kingdom. ILR Review, 71(1), 242–272. doi:10.1177/0019793916687759

- Anzola, D., Barbrook-Johnson, P., & Cano, J. I. (2017). Self-organisation and social science. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 23(1), 221–257. doi:10.1007/s10588-016-9224-2

- Bachmann, C. L., & Gooch, B. (2018) LGBT in Britain: Work report, Stonewall, Retrieved from https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/lgbt_in_britain_work_report.pdf

- Badgett, M. V. L. (2003). Money, myth and change: The economic lives of lesbian and gay men. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Barbrook-Johnson, P., Badham, J., & Gilbert, N. (2017). Uses of agent-based modeling for health communication: The tell me case study. Health Communication, 32(8), 939–944. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1196414

- Barbrook-Johnson, P., Castellani, B., Hills, D., Penn, A., & Gilbert, N. (2021). Policy evaluation for a complex world: Practical methods and reflections from the UK centre for the evaluation of complexity across the Nexus. Evaluation, 27(1), 4–17. doi:10.1177/1356389020976491

- Bayrakdar, S., & King, A. (2021). Job satisfaction and sexual orientation in Britain. Work, Employment and Society. doi:10.1177/0950017020980997

- Boehnert, J., Penn, A. S., Barbrook-Johnson, P., Bicket, M., & Hills, D. (2018) The visual representation of complexity: Definitions, examples & learning points (poster), Loughborough University. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/36771

- Bonaventura, L., & Biondo, A. E. (2016). Disclosure of sexual orientation in the USA and its consequences in the workplace. International Journal of Social Economics, 43(11), 1115–1123. doi:10.1108/IJSE-01-2015-0014

- Browne, K. (2007). Selling my queer soul or queerying quantitative research? Sociological Research Online, 13(1), 11.

- Browne, K. (2010). Queer quantification or queer(y)ing quantification: Creating lesbian, gay, bisexual or heterosexual citizens through governmental social research. In K. Browne & K. Browne (Eds.), Queer methods and methodologies: Intersecting Queer theories and social science research (pp. 231–249). Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Browne, K., & Nash, C. (2010). Queer methods and methodologies. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Button, S. B. (2004). Identity management strategies utilized by lesbian and gay employees: A quantitative investigation. Group and Organization Management, 29(4), 470–494. doi:10.1177/1059601103257417

- Byrne, D., & Callaghan, G. (2014). Complexity theory and the social sciences: The state of the art. London, UK: Routledge.

- Chattoe-Brown, E. (2013). Why sociology should use agent based modelling. Sociological Research Online, 18(3), 3. doi:10.5153/sro.3055

- Colgan, F. (2016). LGBT company network groups in the UK: Tackling opportunities and complexities in the workplace. In T. Koellen (Ed.), Sexual orientation and transgender issues in organizations: global perspectives on LGBT workforce diversity (pp. 525–538). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Combahee River Collective. 1997. A Black feminist statement. In Nicholson, L (Ed.), The Second Wave: A reader in feminist theory (pp. 63–70). London, UK: Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), Article 8.

- Di Paolo, E. A., Noble, J., & Bullock, S. (2000) Simulation models as opaque thought experiments, in M. A. Bedau, J. S. McCaskill, N. Packard, & S. Rasmussen (eds), Seventh International Conference on Artificial Life, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 497–506.

- Edmonds, B., & Moss, S. (2005). From KISS to KIDS – An ‘Anti-simplistic’ modelling approach. In P. Davidsson, P. Davidsson, & P. Davidsson, (Eds.) Multi-agent and multi-agent-based simulation. MABS 2004, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3415 (pp. 130–144). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Elsenbroich, C., Kutz, O., & Sattler, U. (2006). A case for abductive reasoning over ontologies, OWL: Experiences and Directions. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Athens, Georgia. Article 17.

- Epstein, J. (1999). Agent-based computational models and generative social science. Complexity, 4(5), 41–60. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0526(199905/06)4:5<41::AID-CPLX9>3.0.CO;2-F

- Evans, E. and Lépinard, E. (2020). Intersectionality in Feminist and Queer Movevments: Confronting Privileges. London, UK: Routledge.

- Giffney, N. (2004). Denormatizing queer theory: More than (simply) lesbian and gay studies. Feminist Theory, 5(1), 73–78. doi:10.1177/1464700104040814

- Gilbert, N. (2020). Agent-based models (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Gilbert, N., Ahrweiler, P., Barbrook-Johnson, P., Narasimhan, K., & Wilkinson, H. (2018). Computational modelling of public policy: Reflections on practice. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 21(1), 1–14. doi:10.18564/jasss.3669

- Gilbert, N., & Troitzsch, K. G. (2005). Simulation for the social scientist. London, UK: Open University Press.

- Gray, E. M. (2013). Coming out as a lesbian, gay or bisexual teacher: Negotiating private and professional worlds. Sex Education, 13(6), 702–714. doi:10.1080/14681811.2013.807789

- ISER (2020) Understanding Society: Waves 1-10, 2009-2019 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009 [data collection], 13th Edition, UK Data Service. SN: 6614, 10.5255/UKDA-SN-6614-14.

- Jackson, S., & Scott, S. (2010). Theorising sexuality. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Jager, W. (2017). Enhancing the Realism of Simulation (EROS): On implementing and developing psychological theory in social simulation. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 20(3), 14. doi:10.18564/jasss.3522

- Johnson, P. (2015). Agent-based models as “Interested Amateurs.” Land, 4(2), 281–299. doi:10.3390/land4020281

- Kelemen, M., & Rumens, N. (2012). Pragmatism and heterodoxy in organization research: Going beyond the quantitative/qualitative divide. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 20(1), 5–12. doi:10.1108/19348831211215704

- King, A. (2016). Older lesbian, gay and bisexual adults: Identities, intersections and institutions. London, UK: Routledge.

- Köllen T. (2013). Bisexuality and diversity management—Addressing the B in LGBT as a relevant ‘sexual orientation’ in the workplace. Journal of Bisexuality, 13(1), 122–137. doi:10.1080/15299716.2013.755728

- Lustick, I. S. (2000). Agent-based modelling of collective identity: Testing constructivist theory. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 3(1), 1.

- Macal, C. M. (2016). Everything you need to know about agent-based modelling and simulation. Journal of Simulation, 10(2), 144–156. doi:10.1057/jos.2016.7

- McCall, L. (2009). The complexity of intersectionality. In E. Grabham, E. Grabham, E. Grabham, & E. Grabham (Eds.), Intersectionality and beyond: Law, power and the politics of location (pp. 49–76). Abingdon, UK: Routledge-Cavendish.

- McGibbon, E., & McPherson, C. (2011). Applying Intersectionality & complexity theory to address the social determinates of women’s health. Women’s Health and Urban Life, 10(1), 58–86.

- Moore, T. R., Foster, E. N., Mair, C., Burke, J. G, & Coulter, R. W. S. (2021). Leveraging complex systems science to advance sexual and gender minority youth health research and equity. LGBT Health, 8(6), 379–385. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0297

- Msibi, T. (2019). Passing through professionalism: South African Black male teachers and same-sex desire. Sex Education, 19(4), 389–405. doi:10.1080/14681811.2019.1612346

- NIESR (2015) Workplace employment relations survey, 2011 [Data Collection], 6th Edition, Colchester, UK: UK Data Service. 6th Edition, Doi: 10.5255/UKDA-SN-7226-7.

- O’Connor, C., Bright, L. K., & Bruner, J. P. (2019). The emergence of intersectional disadvantage. Social Epistemology, 33(1), 23–41. doi:10.1080/02691728.2018.1555870

- Pedulla, D. S. (2014). The positive consequences of negative stereotypes: Race, sexual orientation and the job application process. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(1), 75–94. doi:10.1177/0190272513506229

- Poile, C., & Safayeni, F. (2016). Using computational modeling for building theory: A Double-Edged Sword. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 19(3), 8. doi:10.18564/jasss.3137

- Railsback, S. F., & Grimm, V. (2012). Agent-based and individual-based modeling. Oxfordshire, UK: Princeton University Press.

- Rousseau, D. A., & van der Veen, M. (2005). The emergence of a shared identity: An agent-based computer simulation of idea diffusion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(5), 686–712. doi:10.1177/0022002705279336

- Rumens, N. (2011). Queer company: The role and meaning of friendship in gay men’s work lives. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Squazzoni, F. (2010). The impact of agent-based models in the social sciences after 15 years of incursions. History of Economic Ideas, 18(2), 197–233.

- Sun, Z., Lorscheid, I., Millington, J. D., Lauf, S., Magliocca, N. R., Groeneveld, J., Balbi, S., Nolzen, H., Müller, B., Schulze, J., & Buchmann, C. M. (2016). Simple or complicated agent-based models? A complicated issue. Environmental Modelling & Software, 86, 56–67. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2016.09.006

- Takács, K., & Squazzoni, F. (2015). High standards enhance inequality in idealized labor markets. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 18(4), 2. doi:10.18564/jasss.2940

- Taylor, Y. (2007). Working-class lesbian life: Classed outsiders. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Kampen, S., Fornasiero, M., Lee, W., & Husk, K. (2017). Producing modelled estimates of the size of the lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) population of England: Final report. London, UK: Public Health England.

- Varela, C. M, and Bayramoglu, Y. (2020). UnRecht und Diskriminierung im Bereich LSBTIQ+: Zentrale Ergebnisse einer Dokumentenanalyse in vier Europaischen Landern CILIA-LGBTQI+ Working Policy Paper, DIAL. Retrieved from academia.edu/43640909/UnRecht_und_Diskriminierung_im_Bereich_LSBTIQ

- Wilensky, U. (1999). NetLogo (and NetLogo User Manual). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University: Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling.