ABSTRACT

The British Government appointed a departmental committee to review anti-homosexuality laws in 1954 following a marked increase in the number of arrests for homosexuality after World War II. The committee invited the British Medical Association (BMA) and other institutions to provide scientific and medical evidence relating to homosexuality. In 1954, the BMA established the Committee on Homosexuality and Prostitution to present its view on how the law impacted upon homosexuals and society. This paper analyses the BMA’s attitudes to homosexuality by examining its submission to the Departmental Committee. Whilst the BMA supported implicitly the decriminalization of certain homosexual acts, it remained strongly opposed to homosexuality from a moral perspective and insisted that it was an illness. It is concluded that the BMA’s submission was driven primarily by a desire to control the “unnatural deviant” behavior of homosexuals and to protect society from that behavior rather than to protect homosexuals.

Male homosexuality was illegal in the United Kingdom prior to the passing of the Sexual Offences Act 1967 which ended an era where “gross indecency” between men could result in a penal sentence of up to life imprisonment (Offences Against the Person Act, Citation1861). The Sexual Offences Act, § 69 (Citation1956) clause 32) explicitly criminalized attempts to procure homosexual relations between men, whether in public or in private. In contrast, female homosexuality has never been criminalized under British legislation. Some have attributed this discrepancy between the sexes to the societal view that female homosexuality was uncommon and thus “presented no social problems” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 29, p. 9) and that “until relatively recent times woman was regarded as only the chattel of men. Moreover, homosexual practices among women seem never to have been regarded as constituting a social danger. The reasons for this may be that they were rare … ” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 37, p. 11). Consequently, the historical problems faced by male and female homosexuals differ significantly and ought to be studied separately (Carr & Spandler, Citation2019). This paper focuses on the attitudes toward male homosexuality and relevant legal reform.

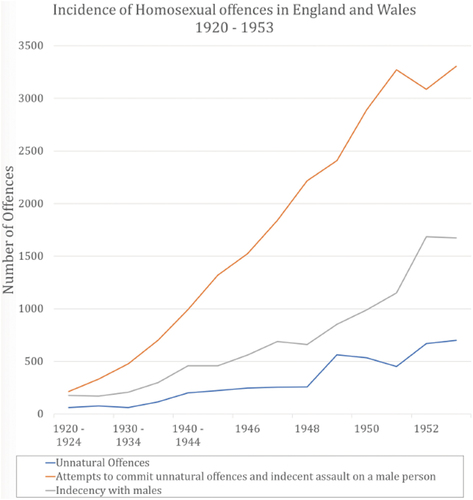

Political and social discourse regarding homosexuality increased following World War II predominantly due to a marked rise in incarceration rates for male homosexual offences (; The Home Office, Citation1953). Compared with a general rise in indictable offenses of 243%, police records show a 759% increase in homosexual offenses between 1930 and 1953. Of particular note was a 1,129% increase in incarceration rates for sodomy, the homosexual offense carrying the greatest punishment (The Home Office, Citation1953). It appears that the increase in arrests may have been partially due to homosexual men becoming less discrete as a result of societal tolerance having increased during the war (Dickinson, Citation2016, pp. 39–44), but this was met after the war by greater, hostile police scrutiny of these offenses (CHP, Citation1955e, para 45, p.13; Weeks, Citation2016, pp. 155–166), as well as a greater public and media intolerance (Dickinson, Citation2016, pp. 51–57).

Figure 1. The incidence of homosexual Offences in England and Wales 1920–1953.

Despite the rise in homosexual offenses, the 1954 Conservative Government was reluctant to examine the law on homosexuality. Instead, it wished to focus on solicitation as incarceration rates for prostitution had also increased significantly since World War II (Secretary to the Cabinet, Citation1954). However, the Government felt that it would face criticism if prostitution was examined in isolation from homosexuality since both were deemed to be deviant sexual practices (Secretary to the Cabinet, Citation1954). Consequently, the Home Secretary persuaded a reluctant Cabinet to appoint a departmental committee to produce a report that examined the laws on both homosexuality and prostitution. The Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offenses and Prostitution (DCHOP commonly called the Wolfenden committee after its chairman) sought contributions from a number of bodies including the British Medical Association (BMA).

The BMA is the main trade union for medical professionals in the United Kingdom. It was established in 1832 with five objectives revolving around the maintenance of scientific and social morality (Little, Citation1932). By the 1950s virtually the entire medical profession (68,000 medical professionals) were members of the BMA, making it extremely influential in guiding medical practice (CHP, Citation1955e, para 1, p. 1). The BMA also formed committees to advise the British Government on legislation that concerned medical professionals or their patient, including late in 1954 a Committee on Homosexuality and Prostitution (CHP) composed of twelve medical practitioners with a specialist knowledge and interest in homosexuality to consider the issues (). The make up of this committee is interesting in that it reflects the then current social view of homosexuality. Thus, historically, homosexuality had been categorized as a mental illness since the late 19th century (Terry, Citation1999, Ch. 2), following on from its classification by scientists as a class and sex based system from the end of the previous century (Terry, Citation1999, Ch. 1), and it was not until 1992 that the World Health Organization removed it from its International Classification of Diseases (Smith et al., Citation2004), the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) having done so in 1974 (Mayes & Horwitz, Citation2005). This change in American medical attitudes came about largely due to research into male homosexuality that had been published by the Kinsey Institute (Kinsey et al., Citation1948), and by Beach and his colleagues (Ford & Beach, Citation1951) and latterly by Evelyn Hooker (Citation1958), and by the political activism of the 1960s and 70s led largely by the homophile activist Frank Kameny (Minton, Citation2002, pp. 252–262). Moreover, under British Law, extending throughout its colonies current and past (including the USA), homosexual acts had been a criminal offense since Henry VIII’s Act to ban buggery (The Buggery Act, Citation1533), punishable by death, and replaced by the Offences Against the Person Act (Citation1861), in which the death penalty was abolished for acts of sodomy—instead being made punishable by a minimum of 10 years imprisonment. In 1885 section 11 of the Criminal Law Act made any male homosexual act illegal—whether or not a witness was present—meaning that even acts committed in private could be prosecuted. Often a letter expressing terms of affection between two men was all that was required to bring a prosecution. The legislation was so ambiguously worded that it became known as the “Blackmailer’s Charter.” This clause was repealed and reenacted by section 13 of the Sexual Offences Act (Citation1956). Unsurprisingly then six of the twelve members of the committee were practicing in medical services associated with the criminal justice system and another two in psychiatric medicine, the remainder being an endocrinologist, an expert in venereal diseases and a general practitioner plus a secretary. Only one woman was present. It is not known whether any of the members were themselves gay although unlikely that this would be known to their fellow committee members since it was tacitly assumed that there were no gay members of the medical profession. Thus, reference is made to the unfortunate corrupting influence of other profession’s gay members on impressionable young men: “The existence of practising homosexuals in the Church, Parliament, Civil Service, Forces, Press, radio, stage and other institutions constitute a special problem” (CHP, Citation1955e, Para 28, p. 9). Moreover, the committee did not take any evidence from gay members of the public, drawing exclusively on the experience of its members plus some limited published material. In this regard the committee differed from the Wolfenden committee, which took personal evidence from three homosexual men, one of them a consultant physician (National achives, Citation1955), evidence that allegedly influenced the committee’s conclusions (Mort, Citation2010, pp. 175–185).

Table 1. The British Medical Association’s Committee for homosexuality and prostitution—committee members [Source: (CHP, Citation1955e)].

The DCHOP sought evidence from the BMA that considered “the law and practice relating to homosexual offenses and the treatment of persons convicted of such offenses by the courts” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 6, p. 3). Whilst the committee considered evidence from various sources, it failed to examine evidence from continental Europe because “In those Continental countries which are usually quoted there has never been a legal bar to homosexual practices between adults and they are accepted as a normality of conduct. To legalise homosexual practices in this country … would amount to a revolution in an aspect of public policy, and it is possible that it would be followed, perhaps only temporarily, by an increase in homosexual activity” (CHP, Citation1955d, para 112, p.6; CHP, Paper, Citation1955). The memorandum of evidence produced by the BMA for the DCHOP report was its first and only statement related to homosexuality prior to the Sexual Offences Act 1967. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1972 that the BMA felt it necessary to attempt a factual and non-moralizing approach, which nonetheless stuck to the pathologizing model (Kenyon, Citation1972). and supported the legalization of private homosexual acts between adult men over 21 years of age (DCHOP, Citation1957). Despite this recommendation, it was not until 1967 that the law was changed. The Sexual Offences Act 1967 closely followed the recommendations of the Wolfenden Report and legalized homosexual acts between two men over 21 years of age in private in England and Wales, with some notable exceptions (Sexual Offences Act, § 60, Citation1967).

Methods

This paper resulted from archival research in the BMA and national archives. The evidence from the BMA archives reveals a changing set of attitudes through the various draft reports produced between 19th July, 1955 and the 17th October 1955 (CHP, Citation1955a, Citation1955b, Citation1955c, Citation1955d), and as reflected in discussions recorded in the Minutes of the committee’s meetings on the 6Th December 1954 and on 3rd February, 3rd March, 31st March, 10th June, 19th July, the 15th and 29th September, 17th October 1955 (CHP Minutes, Citation1954, Citation1955a, Citation1955b, Citation1955c, Citation1955d, Citation1955e, Citation1955f), and the presentation of the final report to the Council of the BMA on the 4th November 1955 (CHP, Citation1955e). The earliest meetings of the CHP were taken up with the production of a series of positional papers on various aspects of homosexuality and the discussion of whether they agreed with the tone of these papers, which they did by and large (CHP Minutes, Citation1954, Citation1955a, Citation1955b, Citation1955c, Citation1955d, Citation1955e, Citation1955f), although there was some dissenting discussion about the moral position taken by EE Claxton in his paper on the Moral Issue (Claxton, Citation1955a, Citation1955b; CHP Minutes, Citation1955f, pp. 2–3). These papers then formed the basis for the draft reports that followed from the 19th July meeting onwards (CHP, Citation1955a, Citation1955b, Citation1955c, Citation1955d, Citation1955e). It should be noted () that three members of the committee, messrs Gleister (0), Summers (3) and Carroll (3), attended few meetings and that only the chair and secretary attended all of them. It is not possible from the minutes to discern the reasons why the report changed when it did or who was influential in the committee.

It should also be made clear that whilst the submission was made to the Departmental Committee on behalf of the BMA the opening preface of the report stated that “On such a wide and controversial subject as homosexuality, however, it cannot be expected that all the members of the profession will be in full agreement on every point, and the council of the association has not attempted to obtain the approval of the whole profession on this Memorandum of Evidence.” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 1, p. 1)

Results

The tone of the BMA’s submission is captured in the introduction to the report, which started by stating (CHP, Citation1955e, para 9, pp. 3–4) “The proper use of sex, the primary purpose of which is creative, is related to the individual’s responsibility to himself and the nation, and the committee believes that the weakening of the sense of personal responsibility with regard to social and national welfare in a significant proportion of the population is one of the causes of the apparent increase in homosexual practices and in prostitution. While many people would regard gross homosexual acts as more serious than promiscuous heterosexual intercourse in that they are ‘unnatural,’ it must be emphasised that it is illogical to condemn the one and condone the other. Both homosexual and heterosexual indulgence have important consequences, such as psychological trauma and venereal disease, but with the latter there is, of course, the additional risk of bastardy.” The only reference to venereal disease is found in this quotation, which is surprising given that by the mid-1950s venereologists were acknowledging the increasing proportion of STD infections found amongst gay men (Evans, Citation2001). The committee then went on to endorse comments along a similar line from the evidence submitted by the Church of England Moral Welfare Council. Thus, there was ambiguity in the committee’s view on homosexuality; on the one hand it was condemned as being unnatural and devoid of biological purpose, whilst on the other the homosexual was given a voice, being allowed to compare himself to a heterosexual fornicator. This ambiguity permeated the whole report including its conclusions which stated: “A public opinion against homosexual practices is a greater safeguard than attempting to suppress them by law. Intensive and sympathetic study of the problem is required to clarify the law and remedy the social ills. Abhorrence of behaviour should not outweigh sympathy and understanding, but should be a stimulus to discover the remedy for the social ills” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 2 p. 38), and in body of the text “In the committees view prison is not usually the most suitable place for dealing with the offender, and many … .could be helped more effectively by medical treatment and moral encouragement outside the prison.” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 71, p. 20), and later in its conclusions: “If the law was relaxed with the result that the commission of homosexual practices between consenting adults in private is no longer an offence. (a) The age of consent should not be less than 21 years. (b) The law should provide adequate protection against seduction by adults of boys and youths under the age of 21 years.” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 36, p. 41). Thus, the BMA did not openly advocate the relaxation of the law but strongly implied its support for such a relaxation, providing further evidence of its ambiguous approach. In this regard, the BMA is following the example set by the American medical profession in the 1940s and 50s which was by and large morally affronted by the practice and regarded its practitioners as being diseased, but nonetheless suggested that treatment was the better option than imprisonment for most consenting adults (Terry, Citation1999, chs.8 and 10).

The key areas identified for consideration by the CHP were the causes of homosexuality, how it may be treated and whether law reform would be advisable, and we follow this format in the consideration of its report here.

Causes of homosexuality

The BMA firmly believed that homosexuals were an inhomogeneous group that could be separated into “essential” or “acquired” categories (CHP, Citation1955e, para 15, p. 5). The descriptions of these groups changed in each draft of the BMA’s report from “primary and secondary” (CHP, Citation1955a, p. 14) to “type A and type B” (CHP, Citation1955d, para 19, p. 11) to “essential and acquired” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 15, p. 5). “Essential” homosexuals either had a “genetic predisposition” to homosexuality or experienced “environmental causes in infancy” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 15, p. 5). As such, homosexuality was seen as an innate characteristic in these men and the BMA posited that they would be incapable of heterosexual interactions and not amenable to treatment for their homosexuality (CHP, Citation1955e para 16, p. 6). In contrast, the “acquired” homosexual developed his sexuality due to environmental influences in later life. The BMA stated that these men “are in many cases amenable to treatment and their homosexual tendencies are regarded as possibly reversible” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 16, p. 6). This classification paralleled the distinction made between “inverts” and “perverts” at the beginning the 20th century (Marshall, Citation1981). The BMA claimed that it was possible, although difficult (CHP, Citation1955e, para 17, p. 6), to diagnose to which group any homosexual belonged, and also asserted that the “acquired” group of homosexuals was significantly larger than the “essential” group despite admitting that there was “no assessment of the incidence of active homosexuality” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 39, p. 12) in the United Kingdom.

Genetics

Historical research concerning whether homosexuality was genetically determined often featured twin studies, such as the one summarized in (CHP, Citation1955a, para 66, p. 33). Since environmental influences are presumed similar in uninovular and binovular twins, these studies gave substantial weight to the theory that homosexuality had a genetically determined component (Slater, Citation1955). The BMA concluded initially that “The close similarity of uninovular twin pairs indicates that certain genes lay down a potentiality which will lead to homosexuality in the person who possess them” (CHP, Citation1955a, para 67, p. 34). Nevertheless, the committee then stated that it was “unable to reach a unanimous verdict” on whether there “is a distinct possibility of [a] genetic basis for homosexuality” (CHP, Citation1955a, para 75, p. 38), a conclusion changed in the final report to: “The committee summarises evidence tending to support a genetic basis” (CHP, Citation1955e, p. 39). This conclusion was reached notwithstanding a statement attributed to Professor Penrose commenting on the balance between genetic and environmental factors as causal for homosexuality (CHP, Citation1955d, para 64, pp. 31–32) “He therefore believes that in the great majority of cases of homosexuality the condition is not abnormal but an example of a natural, and probably inevitable, type of biological variation.” This modern view, which was questioned specifically by S. L. Simpson at the meeting on the 10th June 1955 (CHP Minutes, Citation1955e), did not permeate the general tone of the report, which persisted in labeling homosexual behavior as abnormal.

Table 2. Results from a twin study suggesting that homosexuality has a genetic basis. Figures rounded to the nearest percent. Adapted from, CHP (Citation1955e, p. 16).

Endocrine imbalance

The committee also cited research undertaken by Dr S Leonard Simpson on behalf of its members claiming that many homosexuals presented “feminine features” including deficient body hair and higher pitched voices (CHP, Citation1955d, para 72, p. 34). The BMA did not conclude that these features are necessarily due to an endocrinal disbalance (CHP, Citation1955e, para 62, p. 18), a conclusion that was supported by research which found no significant difference in androgen or estrogen urinary concentrations between homosexuals and heterosexuals (CHP, Citation1955d, para 70, p. 33). The BMA nonetheless supported the collection of larger datasets with the view that “The positive evidence is thought to be sufficiently suggestive as to justify further exploration” (CHP, Citation1955d, para 72, p.35; although this sentence was crossed through by hand in the final report:, Citation1955e, para 62, p. 16) and did not appear in the published version of the report (BMA, Citation1955). The BMA’s rather tentative support for an endocrine basis for homosexuality was opposed by other medical associations, including the Medico-Psychological Association, which concluded that “There is no convincing evidence that there is an endocrine imbalance in the majority of practicing homosexuals” (The Royal Medico-Psychological Association, Citation1955). The BMA countered the lack of evidence for endocrine involvement by criticizing the experimental protocol used and suggested that positive results might be obtained if blood rather than urine samples were tested (CHP, Citation1955e, para 59, p. 17).

Environmental factors

The BMA believed that the primary cause of “acquired” homosexuality was environmental, the key factors being: seduction, intimidation, imitation, segregation of the sexes, defective homes and culture (CHP, Citation1955e, para 20, pp. 7–8). It expressed the view that boys from “good homes” who were taught the “proper and responsible use of sex” would not indulge in sex “without responsibility” (CHP, Citation1955a, para 28(ii), p.15; (CHP, Citation1955e), para 20(ii), p. 7). Imitation was particularly important to the BMA since it opined that most homosexuals “acquired” their habits due to exposure, a conclusion gleaned from the fact that a homosexual often associated with other homosexuals. Consequently, homosexuality was viewed by many in the medical profession as “infectious” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 29, p. 9). This matter was contentious with doctors falling either side of the debate on whether homosexuality would overwhelm society if left unchecked (Learoyd, Citation1954; Soddy, Citation1954). There was also a strong element running through the report of offenses caused by homosexuals to “normal” people such as “ … the behaviour and appearance of homosexuals congregating blatantly in public houses, streets and restaurants, are an outrage to public decency. Effeminate men wearing makeup and using scent are objectionable to everyone” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 26, p. 9). These attitudes caused public protection and the discretion shown by homosexuals to become central issues in the BMA’s consideration of homosexuality.

The BMA concurred with the belief that sexual drive passed through “autoerotic and homosexual phases” in childhood before reaching “heterosexual maturity” (CHP, Citation1955d, para 19, p. 10). As such, some homosexuals were thought to continue “schoolboy conduct” into adult life due to genetic and environmental factors that impacted their ability to reach sexual maturity (CHP, Citation1955a, para 23, p.13; The Royal Medico-Psychological Association, Citation1955, p. 4). One such factor was a homosexual’s “exaggerated emotional attachment” to a “dominant” or “overprotective” mother. Psychoanalysts reported that this left the homosexual unable to reach “heterosexual adjustment” as to him it was “tantamount to incest” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 66, p. 19). However, the committee felt that the extent to which such factors were fundamental to the production of essential homosexuals was difficult to assess. It set great store on the submission from a senior prison officer who was also a psychiatrist who claimed that he found an innate sense of inferiority in all types of homosexual that he had encountered. Moreover, he claimed that “if homosexuals can be brought into communion … … with a fixed body of normal people such as one meets in the Christian community a very great step in overcoming their sense of inadequacy and inferiority will be taken.” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 67, p. 19).

Medical treatment for homosexuality

Unsurprisingly, the BMA CHP committee in 1955 subscribed to the notion that homosexuality was a disease and promoted the use of a combination of sexual treatments. By the 1950s, medical treatment for homosexuals was prevalent in large National Health Service (NHS) hospitals and peaked in the 1960s and 70s despite homosexuality being decriminalized in 1967 (King et al., Citation2004; Smith et al., Citation2004). However, the BMA accepted that treatment of many if not most homosexuals was unlikely to cure them. More likely, treatment would assist in “enabling the individual to overcome his disability, even if it cannot alter his sexual orientation.” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 105, p. 29), an important objective of the treatment being to “adjust himself to his condition … to reach a stage where he is able to exercise sustained restraint from overt acts which would bring him into conflict with the law” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 104, p. 29), in other words, treatments designed to make homosexuals conform to societal norms.

Psychological treatment and character reformation by conversion therapy

The BMA believed that if the “factors in the environment which are producing stress” were relieved by psychological treatment a homosexual would have “improved insight” (CHP, Citation1955a, para 163, p. 71). Psychoanalysts advocated long-term therapy for the resolution of unconscious childhood conflicts responsible for homosexuality (Bieber et al., Citation1962). Hypnotherapy was the most commonly delivered if unsuccessful psychological treatment for homosexuality at the end of the 19th century (Weeks, Citation2016, p. 31). The BMA expressed the view that psychological therapy was particularly suitable for “neurotic patients” and those who sought treatment before arrest (CHP, Citation1955e, para 119, p. 31).

Christianity and medicine were intertwined in the 1950s and, as such, the BMA included several pieces of evidence submitted by clergymen in the appendix to its report (CHP, Citation1955e, para 128, p. 33). The BMA supported the Christian Church’s recommendation that a homosexual must become a “God-centred personality” in order to overcome his sexual desires and included a section on “Religious approaches in treatment” in its report (CHP, Citation1955e, para 128, p. 33). Despite this, there appears to have been no coordinated scheme for the delivery of therapy to homosexuals prior to its decriminalization in 1967. Subsequently, however, multiple Christian organizations including True Freedom Trust, Courage UK and Exodus International were established that supported the use of conversion therapy and celibacy for homosexuals, a course of action which has recently been deemed irresponsible and unacceptable by the NHS (Memorandum,Citation2017).

Physico-psychological treatments

Electro-convulsion Therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric treatment that involves the delivery of electricity to a patient’s brain to induce seizures (Eppig & Libon, Citation2011). ECT sessions typically occurred twice weekly and were delivered by junior doctors in a hospital clinic (Pippard & Ellam, Citation1980). It was commonly used in the 1950s but less so in the 1960s and 70s.

The objective of aversion therapy, a form of behavior therapy, was to induce disinterest in the same sex by administering unpleasant sensations whilst the patient viewed erotic homosexual images. These sensations would cease when the homosexual viewed erotic photographs of the opposite sex (Smith et al., Citation2004). Several aversive stimuli were used by doctors in this treatment but apomorphine administration often combined with electric shock treatment (EST) via electrodes connected to the patients via wrists, calves or feet (abreaction) were the most common. Graphic descriptions of how these degrading treatments were administered during the 1950s and 60s are given in Dickinson (Citation2016, pp. 65–70). Patients who took apomorphine were routinely admitted to hospital due to the side-effect of dehydration, resulting in at least one fatality (D’Silva, Citation1996). Despite aversion therapy being the most common treatment provided to homosexuals (Smith et al., Citation2004), it was referenced only in passing in the BMA’s report: “Although methods of physical treatment used in connection with psychiatric treatment, such as E.C.T or abreaction, are indicated in some cases, they are of value in accompanying mental illness rather than for the homosexual condition itself” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 122, p. 320).

Chemical castration

Chemical castration involved the administration of estrogens to reduce the gonadal production of testosterone in order to lower a homosexual’s libido (Wibowo & Wassersug, Citation2013). Whilst some men underwent this procedure voluntarily, others did so under a court order (His Honour Judge J. Fraser Harrison, Citation1952). In the first draft of its report, the BMA stated that hormone treatment was useful in 10% of outpatients as a semi-permanent treatment, especially for young offenders (CHP, Citation1955a, para 164, p. 71). However, this recommendation was retracted in later drafts since the committee found that chemical castration did not always result in “the cessation of offence by the individual” as the homosexual’s romantic affections were undiminished (CHP, Citation1955e, para 122, p. 32). Criticism from the wider medical profession over the unknown effects of chemical castration and the possibility that it may “accentuate passive tendencies which are innate in homosexuals” may also have impacted the BMA’s view (‘Burrows, Citation1946; Castration of Sex Offenders, Citation1955). The poor success rates reported from a well-known Danish castration scheme may also have been influential in the BMA’s reversal in opinion. Danish law permitted the institutional treatment of homosexuals, resulting in six hundred Danish men being castrated physically between 1930 and 1956 (Weeks, Citation2016, p. 31). However, the scheme was found to be unsuccessful, 90% of homosexuals reoffending following treatment (‘Castration of Sex Offenders, Citation1955). The BMA did not recommend physical castration as a treatment for homosexuality (CHP, Citation1955e, para 123, p. 32).

Treatment efficacy

Despite detailing treatments in its report, the BMA accepted that there was “no panacea in the cure of homosexuality” (CHP, Citation1955a, para 145, p. 65). Whilst it stated that “not all homosexual persons need, or are amenable to, medical treatment” it maintained that “a larger proportion can benefit, to a greater or less degree” (CHP, Citation1955a, para 146, p. 65). In the final draft of its report, the BMA also admitted that some treatments for homosexuality were unethical and potentially dangerous. The CHP did not specify which therapies it was referring to: “It must be admitted with regret that some of the advice given to homosexuals in the name of treatment is often useless, simply defeatist, or grossly unethical. Some of it may be even dangerous as when with insufficient investigation into aetiology a confirmed homosexual is advised to marry, without thought for the future partner.” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 105, p. 29). It concluded that further research into treatment for homosexuality was necessary and that “a balanced view of the subject has not yet been generally obtained” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 129, p. 33). Despite this, treatment for homosexuals in custody was mandatory under the Criminal Justice Act (Soddy, Citation1951).

Sentencing and imprisonment of homosexuals

In the BMA’s view, a law against homosexuality must be “deterrent,” “reformatory,” and for the protection of the general public. The BMA praised the Offences Against the Person Act (Citation1861) for instilling in the public mind that homosexual practices were “reprehensible and harmful” and for creating “public opinion against [homosexuals]” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 92, p. 25). Despite this, the BMA challenged whether imprisonment was effective in all cases, eventually suggesting that some homosexual acts should be decriminalized.

Inconsistencies in sentencing

A major flaw in the Law Against the Person Act 1861 identified by the BMA was a lack of guidance on how homosexual offenses should be sentenced, as demonstrated by evidence presented to it in , which itself conflates pedophilia with homosexuality. The BMA identified in an early draft (CHP, Citation1955a, para 85, p. 41) that the current law left homosexuals vulnerable to the “personal view of the particular judge” but later condoned this situation as inevitable due to the “variety” in public opinion on homosexuality (CHP, Citation1955b, p. 1). The committee recommended an amendment to the law to increase its specificity, thus limiting the extent to which personal interpretation could impact the defendant. The BMA particularly stressed that legal distinctions should be provided between first-time and persistent offenders as well as between “essential” and “acquired” homosexuals (CHP, Citation1955d, para 79, p. 37). In the BMA’s view, the nondiscriminatory character of the law rendered “essential” homosexuals vulnerable to blackmail, often producing “a degree of nervous tension and strain” for which “medical and psychiatric advice” was sought (CHP, Citation1955e, para 91(a), p. 24). Thus, a relaxation of the law in favor of the “essential” homosexual was reasoned to alleviate the anxieties of men who otherwise wished to live as law abiding citizens.

Table 3. Anecdotal evidence detailing homosexual offenses with inconsistent penal sentence length. Adapted from evidence provided by Dr Stanley-Jones to the CHP (Citation1955b, p. 37).

In order to remedy the inconsistencies in sentencing, the BMA proposed a progress-based sentencing systems whereby no sentence length would be decided upon conviction. Instead, the homosexual would be released when he became successful in suppressing his urges and “his response when released would be desirable” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 78, p. 21). The BMA acknowledged that this method of sentencing would be novel in British Law, however, the committee expressed the view that the detention of an “incorrigible homosexual offender” was necessary whilst he was a “danger to the public” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 79, p. 21).

Imprisonment

The BMAs views on whether imprisonment was appropriate changed throughout the drafting of its report. The committee originally stated that imprisonment failed to “protect the general public” and constituted a “waste of public money” with “no beneficial effect” on the homosexual. In two draft sections (CHP, Citation1955c, paras.104, 105, p. 3) the committee stated “The law contains many illogicalities. … Among men the act of masturbation when practised alone in private constitutes no offense, If, on the other hand, two males practise on themselves the same act, but together, even in private, it becomes a serious offence.” and “The law takes up the position that every homosexual act is per se an offence. … Friendship between two individuals of the same sex is generally a noble relationship. A love affair between two men which gives rise to physical expression may be considered immoral but is not a crime. judgment on a criminal act must take into account the nature of the act and where and how it was committed.” Thus, by implication the committee suggested that some criminal acts were not really criminal. Consequently, the BMA stated that “it is arguable that a homosexual practice should be regarded as a crime only when there is a criminal element apart from the mere fact of homosexuality” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 91d, p. 24). This statement was qualified by support for the continued imprisonment of homosexuals who “seduce” or “corrupt” others (CHP, Citation1955e, para 94, p. 25). However, the committee maintained that prison was not usually “the most suitable place for dealing with [a homosexual]” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 71, p. 20). This belief was not extended to “incorrigible homosexuals” however, whose persistent offending made them a “danger to the public” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 79, p. 21). The BMA initially recommended the institutionalization of habitual offenders and presented Broadmoor (a high security psychiatric hospital) as an exemplar institution (CHP, Citation1955a, p. 48). References were also made to incorrigible homosexuals being “psychopaths,” although no evidence to support this assertion was provided (CHP, Citation1955e, para 79, p. 22).

The BMA’s major issue with the nondiscriminatory imprisonment of all homosexuals appears to be the opportunities prison provided for continued offending. It feared that non-homosexual prisoners would be “infected,” causing the CHP to initially suggest that homosexuals should be segregated into “special wings.” These wings would be monitored by a team comprised of “a prison officer, a prison doctor, a psychiatrist, a religious worker and a social worker” dedicated and sympathetic to the rehabilitation of homosexuals (CHP, Citation1955a, para 96, p. 45). The BMA also recommended the housing of first-time offenders in separate institutions to which non-prosecuted homosexuals could also voluntarily commit themselves on the advice of their doctor (CHP, Citation1955a, para 99, p. 47). However, the BMA’s policy of segregation was revised in later drafts on the basis that it would be neither “practical or desirable” and would “place an unnecessary stigma on homosexuals” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 73, p. 20). Concerns were also raised over the allocation of large sums of money toward a small group of prisoners, many of whom would be unresponsive to treatment (CHP, Citation1955d, para84, p. 39). Thus, the BMA’s final report recommended the continued integration of homosexuals within the prison but maintained that a team dedicated to their rehabilitation should be provided (CHP, Citation1955e, para 76 & 77, p. 21). An exception was made for first time offenders, whom the BMA suggested should be ordered to attend regional treatment centers which would allow the homosexual to be monitored within the community (CHP, Citation1955e, para 75, p. 21).

The committee “agreed unanimously” that the age of consent should be twenty-one. It believed that those younger than twenty-one were “not likely to have the quality of responsibility” to consent to homosexual practices. It also raised concerns that homosexuality “may persist in adult life” if men were permitted to perform homosexual acts in their youth (CHP, Citation1955e, para 94, p. 25).

Discussion

The BMA’s report lacked scientific evidence throughout to support its conclusions on the causes of homosexuality. This is particularly evident in its inclusion of endocrine factors despite there being no supporting evidence for this theory. Committee minutes concerning the categorization of homosexuals into “acquired” and “innate” groups detailed how the names, definitions and number of groups were changed without consideration of supporting scientific studies (CHP Minutes, Citation1955e). Additionally, the committee dismissed research stating that 37% of American adult men have had homosexual experiences between the beginning of adolescence and old age and 10% of American men were exclusively homosexual for at least three years of their adult lives (Kinsey et al., Citation1948). It concluded that “the committee believes that if a similar study were made here the incidence would be found be much lower” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 40, p. 12), despite there being “no assessment of the incidence of active homosexuality in this country” (CHP, Citation1955e, para 39, p. 12). On what grounds the committee held this belief is not made clear, especially since the Kinsey data had been evaluated and found to be statistically sound (Cochran et al., Citation1954). The BMA’s omission of reasoning when contradicting evidence from elsewhere suggests that the committee’s members prioritized personal views and experience over scientific evidence. By modern standards, the apparent lack of objectivity displayed by the committee implies poor scientific practice. However, evidence from a doctor denouncing the notion that science should be “detached” and “emotionless” (Learoyd, Citation1954) suggests that this was common practice in the 1950s. Members of the committee may have felt justified in contesting or validating evidence through the lens of their social or moral views.

The idea that homosexuality arose from sexual immaturity is interesting since the BMA appeared to base this view largely on information gained from the study of single-sex boarding schools. The segregation of these boys from the opposite sex in their adolescence resulted in the boys learning about sex and sexuality from other males. The BMA identified that whilst some of the boys performed sexual acts in front of or with other males, the majority of them did not progress to become homosexuals in adult life. Thus, the BMA, and many other medical professionals, concluded that homosexuality was an adolescent stage of sexual development with heterosexuality being reached upon maturity (CHP, Citation1955e, para 20(i) p.7; Allen, Citation1969). The validity of this conclusion is clearly flawed since it was based on one small societal group with no effort being made to identify a similar sexual development process in adolescents from other social backgrounds. This flaw reflects the strong class barriers present in medicine in the 1950s, medical professionals being largely middle- and upper-class men. Here, doctors appear to have presented evidence from their own childhoods as medical fact, reinforcing the argument that the committee held the unsubstantiated personal experiences of its members in the same regard as scientifically conducted studies.

The notion that homosexuality was contagious was common during the 1900s and became central in the debate on homosexual law reform. The BMA’s conclusion that homosexuality was contagious because one homosexual was often involved with several others was illogical, since the same could be said of people with any common interests or characteristics. However, this attitude may explain the BMA’s certainty that homosexuals could be categorized into “acquired” and “essential” groups. Evidently, the medical profession was unwilling to accept that homosexuality could be a harmless natural variation of sexual expression, as had been put to them by Professor Penfold, but instead preferred to highlight the opinion of the senior prison officer with his strong Christian message.

Despite treatment for homosexuality being relatively widespread in the 1900s, the BMA provided doctors with no clinical guidelines prior to its report for the DCHOP in 1955. Other British medical bodies also lacked guidance on homosexual treatment and information was primarily exchanged between doctors via short letters in the British Medical Journal. Consequently, homosexual treatment was largely experimental and performed on a trial-and-error basis (Dickinson, Citation2016, p. 79). This unethical practice reflects the medical profession’s disregard for the welfare of the individual homosexual patient. Whilst the BMA did denounce the delivery of “dangerous” therapies, its opposition was short, weak and followed several paragraphs detailing recommendations for psychological and psychiatric treatment. The increased use of aversion therapy and chemical castration following 1955, highlights the BMA’s failure to discourage doctors from these practices.

Whilst the BMA admitted that it was not possible to cure all homosexuals, it maintained that treatment was beneficial in most cases. This view was not supported by the evidence available at the time. Most strikingly, one psychoanalyst reported that, despite only 18% of his patients being exclusively homosexual prior to treatment, just 27% reported being exclusively heterosexual after treatment (Haldeman, Citation1991). Statistics for the efficacy of homosexual treatment in the 1950s are problematic since patients were often referred for treatment by the courts in order to avoid prison sentences. Consequently, patients were likely to over-report their progression to reduce treatment time and the risk of subsequent imprisonment (Dickinson, Citation2016, pp. 75–76). The fact that success rates remained low despite this likely over-reporting highlights the ineffectiveness of treatment. The BMA included no references to the success rates of the treatments it detailed, an essential piece of information that would be expected in a medical report. This omission implies a sense of indifference from the BMA as to the welfare of homosexual patients and the prioritization of treatment regardless of its efficacy. The extent of the ineffectiveness of conversion therapy, which the BMA supported until it was declared to be a suspect therapy (BMA meeting, Citation2010; Memorandum, Citation2017), has been exemplified in modern studies free from the complications of criminalization. Shidlo and Schroeder (Citation2002) found that 3% of men felt that conversion therapy had caused their sexual orientation to change whilst 9% reported a complete loss of libido (Shidlo & Schroeder, Citation2002).

The BMA’s inclusion of religious character reformation as a treatment for homosexuality was reflective of the social context of its report. Christian values were at the heart of public discourse on morality in the 1950s and as a result, Christianity had a significant impact on legislation. It is therefore unsurprising that in the 1950s religious officials were viewed as expert advisors from whom individuals sought guidance. However, the endorsement of religious conversion therapy by a medical group is not acceptable by modern standards and demonstrates that science and religion were not distinct entities in the 1950s.

Whether imprisonment was an appropriate punishment for homosexuality was evidently the most contentious issue for the BMA. The BMA’s report contained many statements pertaining to its moral condemnation of homosexuality and particularly emphasized that it did not “condone homosexual practices of any kind” despite its tentative support for decriminalization (CHP, Citation1955a, para 121, p. 54). The BMA’s report contained many of these contradictory statements, which appear to arise due to inconsistency between its moral and objective arguments. In sections addressing the ethical issues of homosexuality, the BMA strongly opposed its acceptance in society since it would “condone a lower standard of morality” (CHP, Citation1955d, para 103, p. 46). However, in sections focusing on the objective benefits and disadvantages of imprisonment, the BMA fell implicitly in favor of legalization for consenting adults in private. The BMA’s concern with public morality reflects its style of ethical practice in the 1950s, and implies that patient welfare was considered to be of lower importance to the BMA at this time.

The BMA displayed a clear lack of tolerance toward homosexuality, particularly in its suggestion of a progress based sentencing system. This was proposed in spite of the BMA admitting that few homosexuals were likely to be responsive to treatment. Progress based sentencing would thus essentially condemn the many who were unable to change their sexual behavior to a life sentence. The BMA’s recommendation for the permanent detention of habitual offenders in psychiatric units further stigmatized non-conforming homosexuals. It also contradicted the BMA’s supposed wish to alleviate the anxieties of otherwise law abiding “essential” homosexuals. Whilst the BMA in its final report did reference its desire to not place “unnecessary stigma” on homosexuals through intra-prison segregation (CHP, Citation1955e, para 73, p. 20), this attitude can be more attributable to other factors. The suggestion that significant public funds should be spent on an ostracized group would have likely caused outrage from the British public. Thus, it seems likely that the BMA reversed its opinion on whether homosexuals should be segregated within prisons to avoid public criticism. The evidence outlined above provides weight to the argument that the BMA only wished to support the social integration of those homosexuals who actively attempted to alter their sexual orientation in line with the BMA’s standard of morality.

The BMA’s lack of tolerance toward homosexuality can be attributed to its fear of public “infection,” as evidenced by its condemnation of homosexuals who “seduce” or “corrupt” others (CHP, Citation1955e, para 94, p. 25). Thus, the BMA appeared to be less concerned with alleviating the fear of arrest for homosexuals than with the maintenance of public morality. The legalization of homosexual acts in private between men over twenty-one years old, as supported implicitly by the BMA, also did little to combat the inconsistencies in the sentencing of those homosexual offenses that remained illegal after 1967. For example, in 1989 it was found that, compared with men who had consenting sex with girls under sixteen, men who commit the consensual offense of “indecency between males” with partners over sixteen were five times more likely to be prosecuted and three times less likely to be let off with a caution (Tatchell, Citation1992). This constituted a failure to address the issue of homophobia then extant within the police and judicial systems (Mort, Citation2010, pp. 152–164). Whilst the BMA identified that ambiguous legal wording was problematic, it offered no solutions to prevent the homophobic personal attitudes of certain judges and police officers from affecting the treatment of a homosexual defendant. Whilst the BMA rightly identified that homosexual sentences were wildly inconsistent, the data used to support its findings was exclusively related to pedophilia rather than sex between consenting men. Although the BMA’s conflation of pedophilia and homosexuality in this instance is concerning, it is also reflective of a common fear surrounding homosexuality in the 1900s. The Offences Against the Person Act (Citation1861) made no reference to an age of sexual consent for males. Thus, boys were only poorly protected from pedophilia. Consequently, some feared that if the law on homosexuality was reformed it would leave boys vulnerable to male molestation. The BMA supported this belief and highlighted its fear that the young would be corrupted if homosexuals were unregulated. It is likely that this fear was the rationale behind the BMA’s proposal for an older age of consent for homosexuality compared to heterosexual relations.

The outcome of the Wolfenden report

Twenty other medical representatives, associations and scientific institutes were invited to present evidence to the DCHOP with the same brief as the BMA (see Appendix). The majority of the organizations concurred with the BMA’s support for the decriminalization of the consensual, private homosexual practices between adults (Lewis, Citation2016). Analysis of the various reports demonstrated that the BMA’s evidence was largely consistent with the other scientific and medical associations, although some notable differences were apparent. The majority of the medical bodies consulted also used pathological language such as “mental deformity and “personality disorder” to describe homosexuals. On the matter of causation, there was general concurrence with the BMA that homosexuality was more frequently due to nurture than nature. The British Psychological Society and the Institute of Biology were notable exceptions as both organizations concluded that homosexuality was a naturally occurring sexual anomaly and pointed to evidence of homosexuality existing in situations without cultural prohibitions and amongst animals (British Psychological Society, Citation1955; Institute of Biology, Citation1955). Treatment recommendations varied significantly between organizations although this may have been due to the historic lack of research in the area recognized by the BMA. Most notably, however, the BMA was in the minority in its dismissal of chemical castration as a treatment for homosexuality. The majority of the medical and scientific submissions to the DCHOP supported the delivery of estrogens to reduce libido in homosexuals (Lewis, Citation2016). The endorsement was reflected in the Wolfenden Report which recommended chemical castration for homosexuals, implying that the DCHOP was unconvinced by the BMAs opposition, and aversion therapy continued to be delivered despite the lukewarm discouragement of it by the BMA. No association recommended equality between the age of consent for homosexual and heterosexual sex, but proposed ages ranged from 17 to 21 (Lewis, Citation2016). Cross-analysis of the BMA’s report with reports produced by other medical representatives, associations and scientific institutes indicated that the BMA’s attitudes to homosexuality were largely consistent with medico-scientific thought at that time.

Following the presentation of the BMA’s views to Parliament as part of the Wolfenden Report, the Sexual Offences Act, § 60 (Citation1967) was passed eventually. This act legalized consensual homosexual relations in private between men over twenty-one years of age, but only in England and Wales, Scotland having an effectively more permissive interpretation of the law on homosexual acts, which were decriminalized in 1980 (Davidson & Davis, Citation2012, Ch. 3). Public places were defined as anywhere where more than two people are present or that could be accessed by the general public with or without payment. This included hotel rooms, unlocked rooms in private houses, and rooms without curtains (Sexual Offences Act, § 60, Citation1967). Solicitation and procurement between consenting homosexuals remained illegal after the 1967 Act, as did the aiding and abetting of homosexual relations. The maximum penalties for these offenses was two years imprisonment if both men were over twenty-one or five years if one of the partners was aged between sixteen and twenty-one years of age (Tatchell, Citation1992, pp. 84–100). The Sexual Offences Act, § 60 (Citation1967) thus failed to decriminalize homosexual courting. Consequently, all communication leading up to a homosexual act occurring remained illegal whether it occurred in private or public. The scale of continued legal discrimination after 1967 is evident when analyzing homosexual convictions, 3,000 of which occurred as recently as 1989 (Tatchell, Citation1992). The large number of convictions for indecency shown in reflects the restrictive nature of the term “private” in the law. The only place legally deemed to be “private” was a locked room in one’s own home in which only the two men were present (Tatchell, Citation2017). Homosexuals who committed sodomy in hotel rooms were liable for prosecution (Tatchell, Citation2017) and gay clubs and bars were frequently raided by police for allowing physical contact between men (Davenport-Hines, Citation2001, p.291; Weeks, Citation2016, p. 188). These restrictions were supported by the BMA and justified as measures necessary to prevent the corruption of other men. The BMA did not submit any evidence additional to that presented to the DCHOP with respect to the 1967 law.

Table 4. Convictions for homosexuality related offenses in 1989. Adapted from, Tatchell (Citation1992, p. 89).

Concluding discussion

This is the first detailed analysis of the BMA’s submission to the Wolfenden committee. We find that the BMA implicitly supported the partial decriminalization of homosexuality. It reasoned that homosexuality was innate in some individuals but appeared to believe that environmental factors were more influential in determining sexuality than genetics for most homosexuals. The BMA recognized that not all homosexuals were amenable to treatment and that some medical practices were unethical. However, it believed that treatment should continue to be available for homosexuals who desired it. Sentencing inconsistencies were condemned by the BMA for the fear they instilled in otherwise law-abiding citizens. Ultimately, the BMA felt that that imprisonment was an ineffective punishment for homosexuality since it did little to change a homosexual’s behavior or to protect the public. Whilst the BMA maintained throughout its report that it supported implicitly the decriminalization of certain homosexual acts, it remained strongly opposed to homosexuality from a moral perspective and insisted that it was an illness.

The BMA’s attitudes toward homosexuality are reflective of the general social and media consensus in the early to mid-1900s, and of the medical profession’s paternalistic practice then, and should be evaluated as such. The BMA’s memorandum of evidence on homosexuality wildly exceeded its brief and considered areas not appropriate for a medical report. It may have done this because of the rising tide of popular criticism of establishment immorality that had recently seized the nation (Davenport-Hines, Citation2001). Whatever the motives, this approach leads us to believe that the members of the BMA viewed themselves as superior in knowledge and experience to their patients. This assertion is further supported by the frequency with which the BMA dismissed evidence on moralistic grounds, reducing the scientific integrity and objectivity of its report. As such, the BMA’s decisions appear to have been made for the benefit of the public rather than because they were in the best interests of the homosexual. This reflects the BMA’s founding principle of guiding the morality of the nation, as mentioned in the introduction {Little, Citation1932).

The BMA’s implicit support for decriminalization appears to contradict its moral condemnation of homosexuality, calling into question its motive for supporting legal reformation. The most convincing argument is that the BMA wished to increase the accessibility of treatment to homosexuals. By decriminalizing private homosexual acts, homosexuals could seek treatment without fear of arrest. This argument follows the BMA’s emphasis that although it supported decriminalization and believed that treatment should remain available to those who sought it, it was explicitly opposed to homosexuality itself. Additionally, by increasing the uptake of sexual treatments and decreasing the incidence of homosexual behaviors, the BMA would fulfil its aim of protecting the public, a factor it deemed essential when considering legal reform. Thus, the BMA’s support for the decriminalization of homosexuality appeared to be pragmatic and primarily based on control rather than tolerance.

Whilst the evaluation of the attitudes of the BMA is important in understanding how medical research has historically been conducted and interpreted, it is also important to acknowledge the extent to which the BMA could influence legal reform in the context of homosexuality. The BMA was one of several medico-scientific organizations that contributed to the Wolfenden Report. Although its memorandum of evidence was one of the more substantial submitted, the BMA’s views cannot be interpreted as the sole cause of reform. Nevertheless, the Wolfenden Report echoed the vast majority of the BMA’s views, although it did refuse to classify homosexuality as a mental illness, despite nonetheless urging continued research into the causes and potential cures for it! Ultimately it found that homosexual relations between consenting men over twenty-one years old should be legal. The then Conservative government’s reluctance to review homosexuality laws combined with the police force’s opposition to decriminalization suggests that the medical profession as a whole was ultimately significantly persuasive in the reformation of homosexuality laws in the United Kingdom. The weight that the BMA’s evidence added to the campaign for legal reform has been identified in many popular articles referencing the progress of homosexual liberation (BBC, Citation2002; Stonewall, Citation2016). However, is it reasonable to commend the BMA’s contribution to furthering the rights of homosexual men and the LGBTQ+ community more widely? Due to the arguments outlined above, we do not believe that the BMA held progressive attitudes or accepted homosexuality as a natural variant of sexual expression. Instead, we feel that whilst the BMA did further the rights of male homosexuals through its findings, this effect was incidental rather than intended. Fortunately, the current position of the BMA is more enlightened, witness its rejection of conversion therapies (BMA meeting, Citation2010) and its support for gay and lesbian employees (The experience of lesbian, gay and bisexual doctors in the NHS, Citation2016).

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, C. (1969). A textbook of psychosexual disorders (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- BBC. (2002). Timeline: Gay fight for equal rights. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/2551523.stm

- Bieber, I., Dain, H. J., Dince, P. R., Drellich, M. G., Grand, H. G., Gundlach, R. R., … Bieber, T. B. (1962). Homosexuality: A psychoanalytic study of male homosexuals. Basic Books.

- BMA. (1955). Homosexuality and prostitution: BMA memorandum of evidence for departmental committee. The British Medical Journal, 2(Suppl 2656), 165–170. (Supplement to the journal December 17th) https://www.jstor.org/stable/20333902

- BMA meeting. (2010). Conversion therapy for homosexuals should not be funded by the NHS. BMJ, 341, 3553. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3553

- British Psychological Society. (1955). Memorandum submitted by the British Psychological Society. The National Archives, HO, 345/9, 1955.

- The Buggery Act. (1533). An acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8 c. 6) British Library 506.d.33. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-buggery-act-1533

- Burrows, H. (1946). Castration for homosexuality. British Medical Journal, 1(4448), 551. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.4448.551-a

- Carr, S., & Spandler, H. (2019). Hidden from history? A brief modern history of psychiatric “treatment” of lesbian and bisexual women in England. The Lancet Psychiatry, 16(4), 289–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30059-8

- Castration of Sex Offenders. (1955). Castration of Sex Offenders. British Medical Journal, 1(4918), 897–898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.4918.897

- CHP. (1955a). Memorandum of evidence for Departmental committee - first draft. 15 September 1955. The British Medical Association. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P 14 1955-56.

- CHP (1955b). Memorandum of evidence for departmental committee -‐- revised draft of section V: The medical profession and the law on homosexuality.1. The disposal of offenders. 29 September 1955. The British Medical Association. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P17 1955-56.

- CHP. (1955c). Memorandum of evidence for departmental committee -‐- revised draft of section VI: Medical profession and the law on homosexuality. The control of offences. 29 September 1955. The British Medical Association. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P18 1955-56.

- CHP (1955d). Memorandum of Evidence for Departmental Committee on Homosexuality and Prostitution -‐- revised draft report. 17 October, 1955 The British Medical Association. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P20 1955-56.

- CHP. (1955e). Memorandum of Evidence for Departmental Committee on Homosexuality and Prostitution - Final report to be submitted to the council of the BMA on the 4th November 1955. The British Medical Association. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P24 1955-56.

- CHP Minutes. (1954). Minutes of meeting held on the 6th December 1954. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P7 1954-55.

- CHP Minutes. (1955a). Minutes of meeting held on the 3rd February 1955. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P17 1954-55.

- CHP Minutes. (1955b). Minutes of meeting held on the 3rd March 1955. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P19 1954-55.

- CHP Minutes. (1955c). Minutes of meeting held on the 31st March 1955. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P27 1954-55.

- CHP Minutes. (1955d). Minutes of meeting held on the 5th May 1955. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P33 1954-55.

- CHP Minutes. (1955e). Minutes of meeting held on the 10th June 1955. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P43 1954-55.

- CHP Minutes. (1955f). Minutes of meeting held on the 19th July 1955. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P12 1955-56.

- CHP, Paper. (1955) The law relating to homosexuality in other countries. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P37 1954-55.

- Claxton, E. E. (1955a) The moral issue. The BMA archive, B/107 H&P39 1954-55.

- Claxton, E. E. (1955b). Minutes of Homosexuality and Prostitution Committee 10th June 1955. The British Medical Association. The BMA Archive, B/107 HP43 1954-55.

- Cochran, W. G., Mosteller, F., & Tukey, J. W. (1954) Statistical problems of the Kinsey report on sexual behavior in the human male. American Statistical Association, 2.

- Davenport-Hines, R. (2001). An English affair: Sex, class and power in the age of profumo (3rd ed.) Harper-Collin.

- Davidson, R., & Davis, G. (2012). Sexual states. Edinburgh University Press.

- DCHOP. (1957). Report of the committee on homosexual offences and prostitution. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Parliamentary Archives, HL/PO/JO/10/11/579/1527.

- Dickinson, T. (2016). Curing queers: Mental nurses and their patients. Manchester University Press.

- D’Silva, B. (1996). When gay meant mad. The Independent.

- Eppig, J., & Libon, D. J. (2011). Electro-convulsive therapy. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology (pp. 935–936). Springer. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-0-387-79948-3_1763

- Evans, D. (2001). Sexually transmitted disease policy in the English National Health Service, 1948-2000. In R. Davidson & L. A. Hall (Eds.), Sex, sin and suffering: Venereal disease and European society since 1870 (pp. 246). Routledge.

- The experience of lesbian, gay and bisexual doctors in the NHS. (2016). Report published jointly by the BMA and GLADD. https://www.nwpgmd.nhs.uk/resources/experience-lesbian-gay-and-bisexual-doctors-nhs-report

- Ford, C. S., & Beach, F. A. (1951). Patterns of sexual behavior. Harper & Brothers.

- Haldeman, D. C. (1991). Sexual orientation conversion therapy for gay men and lesbians: A scientific examination. In J. C. Gonsiorek & J. D. Weinrich (Eds.), Homosexuality: Research implications for public policy 1st. (pp. 149–160). Sage Publications, Inc. http://www.drdoughaldeman.com/doc/ScientificExamination.pdf

- His Honour Judge J. Fraser Harrison. (1952, March 31). Charges, pleas and sentences passed on Alan Turing and Arnold Murray. Court Documents. http://www.turing.org.uk/sources/sentence.html

- The Home Office. (1953). Criminal statistics annual report, England and Wales, memorandum of evidence as submitted to the Wolfendon committee appendix B, 49–50. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P25.

- Hooker, E. (1958). Male homosexuality in the Rorschach. Journal of Projective Techniques, 22(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853126.1958.10380822

- Institute of Biology. (1955). Memorandum submitted by the Institute of Biology. The National Archives, HO, 345/8, 1955–1956.

- Kenyon, F. E. (1972). Homosexuality. BMA.

- King, M., Smith, G., & Bartlett, A. (2004). Treatments of homosexuality in Britain since the 1950s—an oral history: The experience of professionals. BMJ, 328(7437), 429. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7437.429.37984.496725.EE

- Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behaviour in the human male. (USA: Wiley periodicals). American Journal of Public Health, 93(6), 894–898. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.6.894 2003

- Learoyd, C. G. (1954). Letter to the BMA dated 3rd December 1954 concerning an article in the Lancet by Dr. K. Soddy (1954) and a response to it by the author. The BMA Archive, B/107 H&P14 1954-55.

- Lewis, B. (2016). Wolfenden’s witnesses: Homosexuality in Postwar Britain. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 103–201. https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9781137321497

- Little, E. M. (1932). History of the British Medical Association 1832-1932 (1st ed.). British Medical Association.

- Marshall, J. (1981). Pansies, perverts and machomen: Changing conceptions of male homosexuality. In K. Plummer (Ed.), The making of the modern homosexual. Hutchinson.

- Mayes, R., & Horwitz, A. V. (2005). DSM-III and the revolution in the classification of mental illness. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 41(3), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/JHBS.20103

- Memorandum. (2017) Memorandum of understanding on conversion therapy in the UK version 2. https://www.psychotherapy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/UKCP-Memorandum-of-Understanding-on-Conversion-Therapy-in-the-UK.pdf

- Minton, H. L. (2002). Departing from deviance: A history of homosexual rights and emancipatory science in America, The University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo3625597.html

- Mort, F. (2010) Capital affairs: London and the making of the permissive society. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300118797/capital-affairs

- National achives. (1955). HO 345 14, CHP TRANS 32; two witnesses called by chairman.

- Offences Against the Person Act. (1861). http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1861/100/pdfs/ukpga_18610100_en.pdf

- Pippard, J., & Ellam, L. 1980. Electroconvulsion treatment in Great Britain The National Archives, Kew, MH166/1501. The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- The Royal Medico-Psychological Association. (1955). Memorandum of evidence to the departmental committee on homosexual offences and prostitution. Submitted as evidence for the meeting on the 10th June 1955 The BMA Archive, B/107, H&P42.

- Secretary to the Cabinet. (1954). Conclusions of a meeting of the Cabinet. Her Britannic Majesty’s Government. National Archives CAB/128/27 p.98, 98. http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-128-27-cc-54-11-11.pdf

- Sexual Offences Act, § 60. (1967). http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1967/60/pdfs/ukpga_19670060_en.pdf

- Sexual Offences Act, § 69. (1956). http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1956/69/pdfs/ukpga_19560069_en.pdf

- Shidlo, A., & Schroeder, M. (2002). Changing sexual orientation: A consumers’ report. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33(3), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1300/j236v05n03_09

- Slater, E. (1955). Letter to the BMA concerning the genetic basis of homosexuality. The BMA Archive Item 6 on p.2 of the Agenda for the meeting of the CHP on the 5th May 1955, B/107 H&P28 1954-55, BMA.

- Smith, G., Bartlett, A., & King, M. (2004). Treatments of homosexuality in Britain since the 1950s—an oral history: The experience of patients. British Medical Journal, 328(7437), 427. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.427.37984.442419.EE

- Soddy, K. (1951). Penalties for sexual offences. Letter in the British Medical Journal, 2(4734), 795. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.4734.795-a

- Soddy, K. (1954). Homosexuality. The Lancet, 264(6837), 541–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(54

- Stonewall. (2016). Key dates for lesbian, gay, bi and trans equality. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/about-us/key-dates-lesbian-gay-bi-and-trans-equality

- Tatchell, P. (1992). Europe in pink: Lesbian & gay equality in the new Europe. Global Media Publishing Limited. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/4558541

- Tatchell, P. (2017). Arrests didn’t end when gay sex was ‘decriminalised’ - they rocketed. iNews. https://inews.co.uk/opinion/arrests-didnt-end-gay-sex-decriminalised-1967-rocketed-522631

- Terry, J. (1999). American obsession: Science, medicine and homosexuality in modern society. The University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo3626344.html

- Weeks, J. (2016). Coming Out: The emergence of LGBT identities in Britain from the nineteenth century to the present (3rd edition). Quartet Books Limited.

- Wibowo, E., & Wassersug, R. J. (2013). The effect of estrogen on the sexual interest of castrated males: Implications to prostate cancer patients on androgen-deprivation therapy. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 87(3), 224–238. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1040842813000322?via%3Di

APPENDIX

Other Medical and Scientific Bodies that contributed to the DCHOP

Doctors

a) HO 345/7: Statement by Mr. Reynold H. Boyd, F.R.C.S., 52, Harley Street, W1.

b) HO 345/9: Memorandum on Venereal Disease and the Homosexual submitted by Dr. F. J. G. Jefferiss, V. D. Department, St Mary’s Hospital, London, W2.

c) HO 345/7: Evidence submitted by the Royal College of Physicians.

d) R. Sessions Hodge, “The Treatment of the Sexual Offender with Discussions of a Method of Treatment by Gland Extracts,” Seances de Travail de la Section de Biologie, 306–7.

Mental Health Specialists

a) HO 345/7: Memorandum from Paddington Green Children’s Hospital Psychology Department on Homosexuality and the Law, March 1955.

b) HO 345/8: Memorandum of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association, June 1955.

c) HO 345/7: Memorandum on Homosexuality submitted by Dr. Clifford Allen, Harley Street, London, SW1.

d) HO 345/8: Memorandum submitted by Dr. Eustace Chesser, 92 Harley Street, W1.

e) HO 345/8: Memorandum of Evidence from the Tavistock Clinic, July 1955.

f) HO 345/8: Supplementary Memorandum from the Tavistock Clinic, March 1956.

g) HO 345/8: Memorandum from the Institute of Psychiatry (University of London), Maudsley Hospital, Denmark Hill, SE5. 13th May 1955.

h) HO 345/8: Memorandum of the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, March 1955.

i) HO 345/9: Memorandum submitted by the British Psychological Society.

j) HO 345/8: Memorandum of a Joint Group appointed by the National Council of Social Service and the National Association for Mental Health.

k) HO 345/7: Evidence submitted by Dr. Winifred Rushforth, Hon. Medical Director of the Davidson Clinic, Edinburgh.

l) HO 345/9: Memorandum by a Joint Committee representing the Institute for the Study and Treatment of Delinquency and the Portman Clinic (I. S. T. D.) London, W1.

m) HO 345/9: Memorandum from Drs. Curran and Whitby.

Scientists

a) HO 345/8: Memorandum submitted by the Institute of Biology.

b) HO 345/8: Memorandum submitted by Professor C. D. Darlington, Sir Ronald Fisher and Dr. Julian Huxley.

c) HO 345/9: Notes of a meeting with Dr. Alfred Kinsey at 53 Drayton Gardens, SW10, 29th October 1955.

Summary of the views of other medical bodies

Twenty other medical representative, associations and scientific institutes were invited to present evidence to the DCHOP with the same brief as the BMA. Similarities and differences between the findings of these bodies may reflect whether the BMA’s evidence was indicative of the opinions of the wider medical profession. In terms of causation, most submissions concurred with the BMA that homosexuality was more frequently due to nurture than nature. Many bodies consulted used language associated with illness including “mental deformity,” “immaturity” and “personality disorder” when describing homosexuals. Kinsey emphasized the importance of the first orgasmic experience as being predictive of a man’s future sexuality. As such, he agreed with the BMA that institutionalized males were more likely to become homosexual due to their almost exclusive exposure to men during sexual development. The most notable exceptions to the nurture rather than nature theory were the British Psychological Society and the Institute of Biology both of which argued that homosexuality was a naturally occurring sexual anomaly. Both cited Ancient Greece and mammals as examples of how homosexuality can exist in situations with no cultural prohibitions. Contradictions to the BMA’s theory that homosexuality was a stage of sexual development in adolescents were presented by several other associations who argued that sexual orientation was fixed during early childhood. Opinions on whether homosexuals should undergo extensive psychological treatment or be segregated into medical institutions were extremely mixed between the medical submissions. Most notably, however, the BMA was in the minority in its dismissal of chemical castration as a means to treat homosexuals. The majority of medical submissions to the DCHOP supported the delivery of estrogens to homosexuals in order to reduce their libido. Consequently, chemical castration for homosexuals was recommended in the Wolfenden Report, an inclusion which may be partially due to governmental pressure to gain support for the overturning of a ban on the use of estrogen in English and Welsh prisons. Overall, the evidence submitted by the BMA was fairly reflective of the views of the wider medical profession. In the majority of cases where opinions differed between the medical associations, the BMA correctly identified that more research was required in this area. The BMA concurred with the majority of medical associations in its support for the decriminalization of consensual, private homosexual practices between adults. The suggested age of consent proposed for homosexual acts varied from 17 to 21 and no association recommended that the age of consent should be the same as for heterosexual sex. Kinsey particularly emphasized that other countries which had enacted similar laws did not experience a negative change in the behavior of the population. The support for decriminalization from a variety of scientific and medical associations is likely to have been persuasive in the formation of the Wolfenden Report and its recommendation that homosexuality should be decriminalized.

Source: Lewis (Citation2016). Wolfenden’s Witnesses: Homosexuality In Postwar Britain (London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan UK).