ABSTRACT

Mental healthcare for LGBTQIA+ populations in rural areas remains unequal, despite societal progress toward inclusivity. This review examines the specific obstacles faced in rural areas, such as limited services, workforce deficiencies, and travel burdens for treatment, which exacerbate existing mental health inequities. By following the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology, an exploration of SCOPUS, EBSCO Host (All), and Ovid databases yielded 2373 articles. After careful screening, 21 articles from five countries were selected, primarily using qualitative interviews and quantitative online surveys. Analysis through the Lévesque framework reveals the complex challenges faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals in rural mental healthcare. Discrepancies in approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability, and appropriateness were identified. Geographical isolation, discrimination, and a lack of LGBTQIA+-attuned professionals further compound these issues. Societal stigma, discrimination, and economic constraints hinder individuals from accessing and engaging in mental health services. This study highlights the need for purposeful interventions to improve rural mental health access for sexual and gender minorities.

Introduction

Societal change and increased acceptance of sexual and gender diversity over the course of the last two decades has done little to improve the healthcare experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQA+) people. The disparities in health based on sexual orientation and gender identity are well documented and researched (Institute of Medicine US Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Citation2011; Przedworski et al., Citation2015). Members of the LGBTIQA+ community consistently experience poorer health outcomes, both in terms of physical and mental health when compared to heterosexual and cisgender people (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2018; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2012, Citation2014; Institute of Medicine US Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Citation2011; Perales, Citation2019). The LGBT community has higher rates of mental health problems such as anxiety and depression, substance abuse and suicide, with the prevalence of colon, liver, breast, ovarian and cervical cancer being higher in lesbian and bisexual women then their cisgender peers (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2024; Ceres et al., Citation2018). Gay and bisexual men are at increased risk of viral hepatitis, anal and colon cancer, and other sexually transmitted infections (Australian Bureau of Statistic, Citation2024; Ceres et al., Citation2018; Stenger et al., Citation2017; Wheldon et al., Citation2022). Additionally, people with intersex variations experience high rates of mental health concerns due to stigma, discrimination and poor experiences of the healthcare system (Amos et al., Citation2023). Amos et al. (Citation2023) contends that the intersections between LGBTQ identities and intersex variations continue to be a poorly understood, yet significant concept, despite a high proportion of people with intersex variations identifying as LGBTQ. This inequity in health outcomes highlights the need to ensure equitable access to healthcare (Romanelli & Hudson, Citation2017). The disparities in health based on sexual orientation and gender identity are well documented and researched (Institute of Medicine US Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Citation2011; Przedworski et al., Citation2015), although there is limited research regarding the health disparities of people with diverse sex characteristics (Amos et al., Citation2023; Rosenwohl-Mack et al., Citation2020; Zeeman & Aranda, Citation2020). Research indicates that people with diverse sexualities, genders and sex characteristics, often experience a multitude of challenges when engaging with health systems including multilevel discrimination, inappropriate care, lack of understanding of sexual or gender diversity on the part of the healthcare provider, and culturally unsafe care (Romanelli & Hudson, Citation2017; Smith & Turell, Citation2017). People with diverse sexualities, genders and sex characteristics experience these challenges in unique ways, with the experience of everyone being different based on their sexuality, gender and sex characteristics.

LGBTIQA+ people living outside of metropolitan, or larger regional centers face further challenges in their attempts to access healthcare, often faced with a lack of specialist, and in some cases generalist, services, health workforce shortages, and travel related burdens which shape both health and healthcare access (Blodgett et al., Citation2017; Heng et al., Citation2019; Holt et al., Citation2020). Although the volume of research involving rural and remote health continues to increase, the intersection of rurality and diversity in sexual orientation and gender identity is not yet well understood and the precise nature and implications of this intersection remain uncertain (Easpaig et al., Citation2022).

This lack of understanding in relation to the precise nature and implications of the intersection of rurality and diverse sexuality, gender identity and sex characteristics potentially stems from lower representations of people with diverse sexualities, gender identities and sex characteristics in research studies investigating rural and remote health. Research findings specific to the LGBTIQA+ community are often not specifically identified, or explored by researchers, impeding the accumulation of knowledge specific to the experiences LGBTIQA+ people in relation to rural and remote health. Due to the often conservative nature of rural and remote communities, it is also possible that individuals who self-identify as being LGBTIQA+, may not be willing to identify as such even in research studies due to the stigma which has historically been attached to other then heteronormative identities (Rosenkrantz et al., Citation2017; Warren et al., Citation2015). Whilst there are no definitive statistics which reliably report the number of LGBTIQA+ individuals living in regional and rural areas, Wilson et al. (Citation2020) estimates the total sexual minority population, aged over 18 years in Australia, is 3.56% of the total population. Using the estimate provided by Wilson et al. (Citation2020) it is reasonable to hypothesize that, on average, just over three per cent of the population in a rural or remote area belong to a sexual minority group. This is a significant population who are routinely experiencing less then optimal healthcare in an era where the Sustainability Development Goals progress an agenda for good health and well-being for all by 2030 as one of the 17 United Nations Sustainability Goals.

The most comprehensive report on research involving sexual minority groups and healthcare in a rural and remote context is the systematic review by Rosenkrantz et al. (Citation2017), which focused on US samples between January 1998 and February 2016. This review identified mental health issues as a concern among rural LGBTIQA+ communities, along with findings on sexual risk-taking behaviors and substance misuse. Recent investigations by Easpaig et al. (Citation2022), Grant & Nash, (Citation2019), Heng et al. (Citation2019), and Owens et al. (Citation2020) underscore the pressing need to advance our understanding of the health and healthcare experiences of rural and remote LGBTIQA+ communities, with a particular emphasis on mental healthcare access. This is crucial for addressing the existing health outcome disparities faced by LGBTIQA+ individuals residing beyond metropolitan and larger regional centers.

In alignment with this imperative, our scoping review aims to contribute to ongoing efforts by addressing accessibility disparities for LGBTIQA+ communities in rural and remote areas, specifically focusing on mental healthcare. While Rosenkrantz et al. (Citation2017) laid a foundational understanding, particularly regarding mental health, our review synthesizes relevant evidence generated over the last 20 years. By providing an updated perspective, we extend the temporal scope by seven years beyond prior reviews in this domain. Importantly, no previous review has specifically focused on the intersection of rural and remote contexts with the mental healthcare experiences of the LGBTIQA+ community.

Lévesque conceptual framework

Revisiting the concept of access

This review uses the conceptual framework proposed by Lévesque et al. (Citation2013) to conceptualize access at the interface of health systems and populations to present the experiences of sexual minorities in accessing mental healthcare in rural and remote communities. Within this context, access is defined as the opportunity to reach and obtain appropriate healthcare services when there is a perceived need for care (Goddard & Smith, Citation2001; Gulliford et al., Citation2002; Oliver & Mossialos, Citation2004). Access is perceived as the outcome of the interplay between the characteristics of individuals, households, social and physical environments, alongside the features of health systems, organizations, and providers (Penchansky & Thomas, Citation1981). Factors influencing access may encompass supply-side aspects of health systems and organizations, demand-side characteristics of populations, and process factors detailing how access is realized (Daniels, Citation1982; Musgrove, Citation1986).

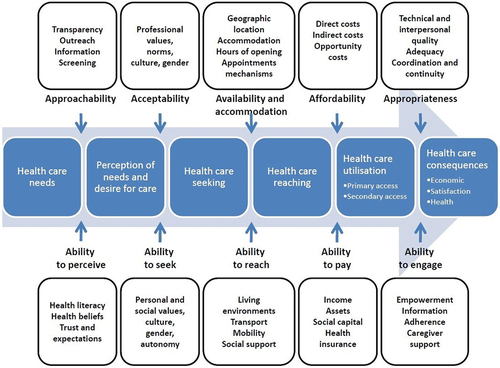

Accordingly, Lévesque et al. (Citation2013) conceptualizes access as the capability to identify healthcare needs, seek healthcare services, reach healthcare resources, obtain or utilize healthcare services, and receive services tailored to the needs for care (refer to ). This concept of access differs from the notion of accessibility, which describes the nature of services providing this opportunity. The framework positions utilization as realized access (Aday & Andersen, Citation1974). In our perspective, access empowers individuals to take steps facilitating contact and obtaining healthcare. Therefore, variations in access are envisioned in terms of disparities in the perception of care needs, healthcare seeking behavior, reaching, and obtaining services (or delays in obtaining), as well as the type and intensity of services received. These distinct steps in the patient’s journey represent critical transitions where barriers to access may become evident.

Figure 1. Lévesque framework (Levesque et al., Citation2013).

Five dimensions of access capturing supply-side and demand-side determinants

The Lévesque et al. (Citation2013) five key dimensions and corollary abilities are: Approachability and Ability to perceive; Acceptability and the Ability to seek; Availability and Accommodation and Ability to reach; Affordability and ability to pay; Appropriateness and Ability to engage (). A major strength of this framework, adding applicability to this review, is that it considers not only the health system perspective but also importantly the population’s/patient’s perspective (Cu et al., Citation2021).

Access to healthcare has been recognized as a major global issue (Cu et al., Citation2021). However, to assess a community’s access to healthcare comprehensively, a comprehensive framework, such as the Lévesque framework, is required to identify challenges. Due to the framework’s process-focused nature, it allows breaking down the process of accessing healthcare into steps (from identifying needs to healthcare consequences) and considering, at each step, the influence of the health service and community of interest. This makes the Lévesque framework suitable for a comprehensive analysis of not only how a community accesses healthcare but also the impact of healthcare services themselves and the community’s (or patient’s) impact on that access (Lévesque et al., Citation2013).

Our scoping review, through the utilization of the Lévesque Conceptual Framework, aims to contribute not only to the understanding of mental healthcare accessibility but also to enhance the growing body of research that recognizes the utility of the framework in assessing healthcare access across diverse populations and contexts. A recent scoping review found only 31 studies that have used this framework as either a priori (to develop data collection tools) or posteriori (to organize and analyze data) (Cu et al., Citation2021). Of these studies, only 20 have applied this framework to organize and analyze data collected and only 8 studies applied both dimensions and abilities across all the domains and abilities, highlighting a paucity of studies that have applied this framework comprehensively.

Review question

What is the extent and nature of the existing literature on mental healthcare accessibility for sexual and gender minority populations in rural settings?

Methodology

This review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for conducting scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2021). The protocol for this scoping review was prospectively registered and can be reviewed in full at https://osf.io/nrvjx

Participants, concept and context

This review focused on studies involving sexually and gender diverse individuals residing outside metropolitan or larger regional centers, particularly those seeking mental healthcare services. Articles that generalized findings to all healthcare services were excluded where data relating to mental healthcare was not retrievable. The primary concept of interest revolved around the accessibility of mental healthcare services.

The review’s context encompassed research conducted in regional or rural settings. While all articles related to participants and the concept were considered, data specifically addressing rural and regional participants had to be available.

Types of sources

This scoping review encompassed both experimental and quasi-experimental study designs, such as randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, as well as before-and-after and interrupted time-series studies. Additionally, analytical observational research, comprising prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, and analytical cross-sectional studies, was considered for inclusion. Descriptive case series and cross-sectional studies were also incorporated, but individual case reports were excluded.

Notably, systematic reviews, text, and opinion papers were outside the scope of this review. Articles were further excluded if they were not in English, lacked empirical data, or failed to contribute relevant findings to address the research question.

Search strategy

To gather preliminary information on the topic, an initial limited search of SCOPUS and CINAHL was undertaken. The text words used in the titles and abstracts from relevant articles were used to refine the search strategy. MeSH terms and keywords were included to enhance search strategies, with the search limited to the previous 20 years (2003–2023). Limiting the search to the preceding 20 years allowed for the inclusion of earlier articles related to LGBTQIA+ people’s access to healthcare, whilst considering societal change and the potential for improved access to healthcare as a result of increased societal acceptance of LGBTIQA+ people. The terms used for each database are included in Supplementary File One. In January 2024, we performed an extensive secondary search of SCOPUS, OVID and EBSCOHost (ALL) to capture any research published after the initial search was completed, with no new articles which met the inclusion criteria being identified. In addition, the reference lists of all identified sources were manually searched for other potential studies.

Source of evidence selection

The review process employed a two-tiered screening approach to identify pertinent evidence for inclusion. Following the JBI Scoping Review protocol, the initial screening involved evaluating titles and abstracts against the predefined inclusion criteria. All authors used the JBI-SUMARI online tool (Munn, Citation2016) to facilitate this stage. Any uncertainties about an article’s suitability were flagged as conflicts, and (SM) resolved these through discussions. The criteria were refined iteratively until a consensus was reached.

Moving to the second screening level, the selected articles were retrieved in full. Once again, utilizing the JBI-SUMARI online tool, all authors collectively determined the inclusion or exclusion of articles based on the pre-established selection criteria. Conflicts were managed following the same approach as in the initial screening process, ensuring a consistent and thorough assessment throughout the review.

Data extraction and analysis

To extract and synthesize data, our approach involved two main steps. Firstly, we compiled a characteristics table from each article, capturing essential details such as author(s), country, year, focal population, study design, aims/objectives, outcomes and funding source. After this information was collated, we focused on extracting data related to the Lévesque Framework, which encompasses five dimensions of accessibility: 1) Approachability; 2) Acceptability; 3) Availability and accommodation; 4) Affordability; 5) Appropriateness. These dimensions interact with five corresponding abilities: 1) Ability to perceive; 2) Ability to seek; 3) Ability to reach; 4) Ability to pay; and 5) Ability to engage.

In the Lévesque data extraction phase, the primary author gathered this information, and a second author verified it by reviewing the created table against the articles. Once this verification stage was completed, each Lévesque dimension was synthesized to generate detailed information about the topic, aligning with each element of the framework. This synthesized information underwent discussion with the wider group of authors and collaborative review to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness. This process aimed to provide a nuanced understanding of the accessibility dimensions and corresponding abilities within the context of mental healthcare services for sexually and gender diverse individuals in non-metropolitan settings.

Results

Search results

The initial literature review identified 2373 articles with 1971 remaining after removing duplicates and the records marked as ineligible by automation tools. Following the first screen there were 91 articles, of which 89 full-text articles were found to be relevant and retrieved for final screening. No other articles were identified through citation searching that had not already been included in the initial search. There were 21 articles considered to have met inclusion criteria with common reasons for exclusion outlined in the PRISMA diagram ().

Characteristics of included studies

The 21 studies originated in five countries: the United States (Easpaig et al., Citation2022), Australia (Perales, Citation2019), Canada (Przedworski et al., Citation2015), Thailand (Institute of Medicine US Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Citation2011) and Brazil (Institute of Medicine US Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Citation2011). The predominant methodology utilized in the included studies was qualitative interviews or focus groups (Holt et al., Citation2020) followed by online quantitative surveys (Romanelli & Hudson, Citation2017), Observational or correlational research (Institute of Medicine US Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Citation2011) and Mixed methods (Institute of Medicine US Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Citation2011). Details of each study is in the characteristics table (supplementary file two).

A synthesis of the Lévesque framework accessibility dimensions collated from the literature and themed presented in supplementary file three (a and b). These have been broken into two parts for ease of reading. Each division related to either side of the framework.

Stigma associated with identifying as a member of the LGBTIQA+ community was consistently identified as a factor associated with navigating access to mental healthcare services in rural areas in Australia (Bowman et al., Citation2020; Cronin et al., Citation2021; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Saxby et al., Citation2020), the United States of America (Gandy et al., Citation2021; Knutson et al., Citation2018; Loo et al., Citation2021; Price-Feeney et al., Citation2019), Canada (Henriquez & Ahmad, Citation2021; Logie et al., Citation2019) and Thailand (Moallef et al., Citation2022). One Australian study (Bowman et al., Citation2020) suggested that the stigma associated with both identifying as LGBTIQA+ and having mental health concerns, resulted in a limited knowledge of access to healthcare services, along with a limited knowledge of the health landscape. This potential lack of awareness of the available healthcare services, resulting from stigma, potentially leads to an exacerbation of a person’s mental health condition, as well as restricting access to preventative health care related to other health issues such as sexual health.

The fear of needing to disclose sexual or gender diversity to healthcare professionals when seeking healthcare was evident in several studies (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Henriquez & Ahmad, Citation2021; Knutson et al., Citation2018), with the need for respectful, gender-affirming care being a consideration (Loo et al., Citation2021; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Moallef et al., Citation2022). Bullying (Price-Feeney et al., Citation2019) and a fear of discrimination (Knutson et al., Citation2018) were identified as factors in accessing mental health services in rural areas. In one Australian study (Saxby et al., Citation2020), participants reported relocating from rural areas to areas where there was less stigma associated with identify as a person who is sexually or gender diverse. A study conducted in the United States (Gandy et al., Citation2021), recognized the significance of societal beliefs in rural areas, as a key factor resulting in stigma associated with access mental health services. Experiencing stigma related to diverse sexuality and gender impacts across several of the elements of the Levesque Framework including approachability, acceptability and appropriateness, as well as ability to perceive.

The need to provide gender affirming care and the need for health care professionals to be aware and understanding of sexual and gender diversity in several studies (Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Reisner et al., Citation2022; Willging et al., Citation2006b). In an Australian study (Miller et al., Citation2022), the provision of care which was holistic and acknowledged the recipient of care as a “whole” was considered, with a study from the United States of America (Moallef et al., Citation2022) identifying the need for care to be both supportive and inclusive. The need to feel comfortable enough to access care was evident in an Australia context (Lyons et al., Citation2015), with this aspect closely linked to the approachability element in the Levesque Framework. Access to gender affirming care closely aligns with the elements of approachability, acceptability, appropriateness, ability to seek, and ability to engage elements of the Levesque Framework, reinforcing the pervasive nature of the challenges sexual and gender diverse people face in accessing healthcare generally, without the additional challenges posed when mental health is added into the equation.

The element of availability in the Levesque Framework was apparent across several studies (Gandy et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2018), with the tyranny of distance identified as a key theme (Gandy et al., Citation2021), alongside the distribution of healthcare services (Miller et al., Citation2022), difficulties in accessing care services (Moallef et al., Citation2022), and in some instances an inability to access appropriately qualified healthcare professions (Roberts et al., Citation2018), due to the inherent challenges in attracting, and then retaining specialist mental health professionals in regional and rural areas. The Levesque Framework elements such as ability to reach, ability to pay and the ability to engage are aligned with the findings of these studies.

A lack of awareness of services available to LGBTIQA+ people in rural areas is an identified area of concern in several studies (Vargas et al., Citation2022; Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010; Willging et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). Access to preventative care services is also highlight as a concern (Barefoot et al., Citation2017; Penchansky & Thomas, Citation1981), with sexually and gender diverse people identified as being less likely to receive both regular, preventative care, or screening for preventable conditions. Ability to engage is a key aspect of the Levesque Framework in this context, especially when considering that many women’s health care providers may not have adequate training to provide appropriate care and screening services for lesbian and bi-sexual women. This also translates to men’s health, with the potential for gay and bi-sexual men to not be screened for preventable conditions based on an assumption by the healthcare provider that recipient of care is heterosexual, and the screening is therefore not required.

The discussion which follows integrates the themes from each of the studies in this scoping review and applies the Levesque Framework elements.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to highlight the disparities and challenges faced by sexual and gender minority populations in rural settings regarding mental healthcare accessibility. Despite positive shifts in societal attitudes toward sexual and gender diversity, the health outcomes for LGBTIQA+ individuals continue to lag, particularly in rural areas. This discussion section will delve into the key findings of our scoping review, employing the Lévesque Conceptual Framework to analyze and synthesize the existing literature on mental healthcare accessibility for the LGBTIQA+ community in rural settings.

“Approachability” and “Ability to Perceive”

In examining the accessibility of mental health services for the LGBTQIA+ community, the critical dimensions of the Lévesque framework, “Approachability” and “Ability to Perceive,” converge significantly. This overlap delineates a complex landscape of challenges impeding these individuals’ access to the necessary care, especially those in rural areas.

The lack of awareness and perceived need for mental health services emerges as a prevalent issue throughout the literature. Numerous studies underscore a general lack of knowledge about available mental health services, particularly outside metropolitan areas (Barefoot et al., Citation2017; Bowman et al., Citation2020; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Loo et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Reisner et al., Citation2022; Vargas et al., Citation2022; Willging et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). This deficiency impacts the “Approachability” dimension, as it directly affects the ability to engage with healthcare services (Barefoot et al., Citation2017; Bowman et al., Citation2020; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Loo et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Reisner et al., Citation2022; Vargas et al., Citation2022; Willging et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). Simultaneously, it intersects with the “Ability to Perceive” dimension, as it hinders the recognition of mental health needs (Barefoot et al., Citation2017; Reisner et al., Citation2022; Willging et al., Citation2006b).

Discrimination and stigma likewise emerge as shared barriers across both dimensions. Fear of disclosing sexual orientation or gender identity, potential discrimination from healthcare providers, or societal condemnation often dissuade LGBTQIA+ individuals from seeking mental health services (Barefoot et al., Citation2017; Cronin et al., Citation2021; Henriquez & Ahmad, Citation2021; Knutson et al., Citation2018; Logie et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Price-Feeney et al., Citation2019; Saxby et al., Citation2020; Vargas et al., Citation2022; Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010; Willging et al., Citation2006a). The combined effects of society’s stigmatization of mental health and gender and sexual diversity tends to exacerbate the challenges LGBTQIA+ people experience in accessing health services, and mental health services in particular.

Moreover, geographical barriers and limited identity recognition also hinder both “Approachability” and “Ability to Perceive” (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Vargas et al., Citation2022; Willging et al., Citation2006b). These difficulties not only affect awareness of available services but also the ability to recognize mental health needs, particularly for LGBTQIA+ individuals in rural areas.

To mitigate these converging challenges, increasing awareness, reducing discrimination and stigma, and overcoming geographical barriers are paramount. Moreover, enhancing mental health literacy within the LGBTQIA+ community and promoting a more inclusive approach to mental health education, particularly regarding affirmative care, can significantly improve the ability to perceive specialized mental health service needs (Loo et al., Citation2021; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Price-Feeney et al., Citation2019; Reisner et al., Citation2022; Saxby et al., Citation2020; Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010; Willging et al., Citation2006a).

“Acceptability” and “Ability to Seek”

The relationship between “Acceptability” and “Ability to Seek” in the context of LGBTQIA+ individuals’ access to mental healthcare services is a complex one, influenced by a confluence of distinct but interrelated factors. Acceptability, as conceptualized within the Lévesque framework, pivots on certain critical elements, including societal beliefs, provider competence and sensitivity, cultural and social factors, socioeconomic factors, and alignment of values and guidelines. Similarly, the “Ability to Seek” encapsulates perceptions and experiences of individuals as they attempt to access healthcare services (Lévesque et al., Citation2013).

Societal beliefs and discrimination form the bedrock upon which both “Acceptability” and “Ability to Seek” are constructed. A raft of research has shown that societal beliefs and discrimination erect substantial barriers for LGBTQIA+ individuals, effectively deterring them from seeking mental healthcare services due to fear, stigma, and discrimination (Barefoot et al., Citation2017; Bowman et al., Citation2020; Cronin et al., Citation2021; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Henriquez & Ahmad, Citation2021; Knutson et al., Citation2018; Logie et al., Citation2019; Vargas et al., Citation2022). This stigma and discrimination also directly impact the ability of LGBTQIA+ individuals to seek care, as some individuals may feel the need to conceal or not disclose their gender or sexuality due to fear of discrimination (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Moallef et al., Citation2022). The often-conservative nature of rural communities tends to increase the likelihood that a LGBTQIA+ individual will conceal, or not disclose their identity as a protective measure to avoid discrimination and stigma.

Provider competence and professional values are another key determinant of both acceptability and ability to seek care. The competence and sensitivity of healthcare providers can play a crucial role in making healthcare services acceptable for LGBTQIA+ individuals, while a lack of cultural competence can be a significant deterrent (Logie et al., Citation2019; Price-Feeney et al., Citation2019; Reisner et al., Citation2022). In terms of the ability to seek care, provider biases, negative attitudes, insensitivity, and a lack of understanding can deter LGBTQIA+ individuals from seeking care (Henriquez & Ahmad, Citation2021; Logie et al., Citation2019; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Willging et al., Citation2006a).

Cultural and social factors, too, wield influence over “Acceptability” and “Ability to Seek.” Cultural attitudes within families (Heng et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2022) and communities (Gandy et al., Citation2021; Knutson et al., Citation2018; Saxby et al., Citation2020) can create significant challenges for LGBTQIA+ individuals. Family rejection (Vargas et al., Citation2022), religious norms (Willging et al., Citation2006b), and societal stigma (Moallef et al., Citation2022) can all directly influence the autonomy and intention of LGBTQIA+ individuals to seek care (Gandy et al., Citation2021; Vargas et al., Citation2022; Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010).

Socioeconomic disparities also have a considerable impact on both acceptability and the ability to seek care. In the context of acceptability, these disparities can influence the use of healthcare services by LGBTQIA+ individuals (Saxby et al., Citation2020), while for the ability to seek care, these disparities can create barriers, particularly for those with a lower income and poor access to services (Saxby et al., Citation2020).

Lastly, the alignment of healthcare values and guidelines with the needs of LGBTQIA+ individuals is vital for both acceptability and the ability to seek care (Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010). When healthcare services align with their values and needs, LGBTQIA+ individuals may be more inclined to seek care (Logie et al., Citation2019; Loo et al., Citation2021; Price-Feeney et al., Citation2019; Vargas et al., Citation2022).

“Availability and Accommodation” and “Ability to Reach”

“Availability and Accommodation” encapsulates the healthcare system’s ability to provide requisite services, including gender-affirming care, LGBTQIA+ specific mental health services, and the physical logistics surrounding geographical location, opening times, and appointment mechanisms (Lévesque et al., Citation2013). On the flip side, “Ability to Reach” signifies the individual’s capacity to engage with these services, influenced by factors such as geographical isolation, personal mobility limitations, and the availability of transportation and social support (Lévesque et al., Citation2013).

These dimensions intersect, spotlighting the complexity of the healthcare system where services may be available but not necessarily accessible. The barriers to accessibility manifest in issues such as geographical isolation, limited access to well-trained mental health professionals, transportation difficulties, and the stigma associated with LGBTQIA+ identities. For instance, geographical isolation is a significant hurdle, both physically (Moallef et al., Citation2022; Price-Feeney et al., Citation2019; Willging et al., Citation2006a) and temporally (Gandy et al., Citation2021; Knutson et al., Citation2018; Loo et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2022; Reisner et al., Citation2022). This isolation is further exacerbated in the digital sphere with rural areas facing challenges in accessing online services due to limited internet connectivity (Bowman et al., Citation2020).

The scarcity of mental health services, particularly in rural areas, further complicates access (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Heng et al., Citation2019; Logie et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Saxby et al., Citation2020; Willging et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). This shortage often necessitates individuals traveling beyond their locality, state, or province to access services. Transportation restrictions, both in terms of cost and accessibility, present additional barriers in reaching healthcare services (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Logie et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2022; Reisner et al., Citation2022; Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010; Willging et al., Citation2006a).

Furthermore, the lack of healthcare professionals trained to address the specific needs of the LGBTQIA+ community further limits the availability and accessibility of services. For instance, the lack of gender-affirming care and mental health services for Latinx transgender youth and the absence of providers with experience working with LGBTQ+ youth is a significant issue (Vargas et al., Citation2022). This deficiency is marked by a lack of standardized medical education focusing on LGBTQ patients and a scarcity of LGBTQ content in nursing programs (Henriquez & Ahmad, Citation2021).

Finally, stigma, specifically structural stigma for individuals in same-sex relationships, affects the ability to reach services, with some individuals more likely to relocate from high-stigma regions to lower-stigma areas for more accessible services (Saxby et al., Citation2020).

“Affordability” and “Ability to Pay”

The Lévesque framework’s “Affordability” and “Ability to Pay” dimensions intersect significantly. These dimensions collaborate to shape a multifaceted array of challenges affecting these individuals’ ability to access the required care, particularly in rural areas.

Numerous studies have identified individual economic factors and the cost of service as crucial elements impacting access to mental health services (Gandy et al., Citation2021; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Saxby et al., Citation2020; Willging et al., Citation2006a). Factors relating to individual financial stability such as income, employment, and health insurance play a significant role (Moallef et al., Citation2022; Willging et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). Concurrently, the cost of services themselves also pose an economic challenge (Cronin et al., Citation2021; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Jenkins et al., Citation2022; Reisner et al., Citation2022). The cost burden of accessing services can be exacerbated for individuals living outside of metropolitan centers due to the tyranny of distance and the need to travel, often long distances, to access services.

Technology plays a significant role in providing health services, especially in rural areas (Bowman et al., Citation2020). However, issues with technology or its accessibility affect not only the “Affordability” aspect but also the “Ability to Pay” for mental health services.

Geographical barriers contribute significantly to access disparities, with the cost of traveling long distances to healthcare facilities in rural areas being a crucial issue (Logie et al., Citation2019; Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010; Willging et al., Citation2006a). Moreover, the local shortage of healthcare providers might compel LGBTQIA+ individuals to travel further to access appropriate care (Barefoot et al., Citation2017).

The challenges converge in the context of transitioning costs and gender-affirming care. For these, there is a pressing need for greater awareness, cost reduction (Miller et al., Citation2022), and services addressing the emotional, social, and legal costs faced by the LGBTQIA+ population (Vargas et al., Citation2022).

“Appropriateness” and “Ability to Engage”

The concepts of “Appropriateness” and “Ability to Engage” play a pivotal role in understanding the intricacies surrounding the provision of mental healthcare services for individuals identifying as LGBTQIA+. The term “Appropriateness,” as outlined within the Lévesque framework, hinges on several factors including technical and interpersonal qualities, the adequacy of services, and their coordination and continuity (Lévesque et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, the “Ability to Engage” is shaped by empowerment, access to information, adherence to treatment plans, and caregiver support, all of which significantly influence individual experiences when accessing mental healthcare services.

The interconnection between these two elements becomes apparent when assessing the provision of mental healthcare services for LGBTQIA+ individuals, where the appropriateness of services and the individuals’ ability to engage intertwine. Inadequately trained healthcare professionals, for instance, have a substantial impact on the “Appropriateness” of mental healthcare services and subsequently, the “Ability to engage” (Barefoot et al., Citation2017; Cronin et al., Citation2021; Gandy et al., Citation2021; Vargas et al., Citation2022). The importance of healthcare professionals understanding the unique health risks and experiences related to sexuality and gender diversity of LGBTIQ+ individuals has been identified as a crucial aspect of their training (Miller et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, the “Ability to Engage” is substantially affected by the presence of health navigators who can act as patient advocates and mediators between patients and healthcare professionals. This highlights the importance of effective communication and client advocacy in facilitating engagement with services (Loo et al., Citation2021).

Clinician qualities and/or behaviors (such as empathy and understanding, inclusivity, and non-judgment) are critical to demonstrate the “Appropriateness” of services and facilitate the LGBTIQ+ person’s “Ability to Engage” in mental healthcare services. The role of non-judgmental and inclusive health professionals is paramount in the provision of appropriate services (Logie et al., Citation2019; Loo et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2022; Vargas et al., Citation2022).

The fit between the healthcare services and the specific needs of the LGBTIQ+ communities is another critical factor impacting the perceived “Appropriateness” of services and their “Ability to Engage” (Loo et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2022; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Saxby et al., Citation2020; Walinsky & Whitcomb, Citation2010). The misalignment between services and client needs can result in inadequate service provision and negative experiences for LGTIQ+ individuals, consequently affecting their ability to engage with these services (Willging et al., Citation2006a).

Discrimination, stigma, and bias are yet another significant hurdle faced by LGBTIQ+ individuals when accessing healthcare services. In addition to affecting the perceived “Appropriateness” of services, these factors also impede their “Ability to Engage” (Henriquez & Ahmad, Citation2021; Knutson et al., Citation2018; Logie et al., Citation2019; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Moallef et al., Citation2022; Saxby et al., Citation2020).

In rural areas, the provision of sensitive services to the needs of sexual minorities may be challenging, affecting the “Appropriateness” of services and the “Ability to Engage” (Reisner et al., Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2018). Rural LGBTIQ+ individuals often resort to nonprofessional resources, such as religious communities and groups, to meet their mental health needs due to the perceived “Inappropriateness” of available services, which subsequently impacts their “Ability to Engage” with mental healthcare services (Willging et al., Citation2006b).

Limitations

Despite the LGBTIQA+ acronym being widely used and considered by many to be “inclusive,” the use of this acronym fails to capture the full diversity and range of identities and practices of the communities discussed in this review. Sexual and gender diverse communities are not homogenous, but rather should be seen as heterogenous, with nuanced and individualized experiences of health and healthcare systems. Applying a homogenous framework to sexual and gender diverse communities can lead to assumptions which are problematic for heterogenous communities, such as people who are intersex, which are coalesced into a homogenous group with very different experiences (Carpenter, Citation2020). Many of the articles consider the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and to a lesser extent, transgender people, with little, if any consideration of intersex and asexual people and their experience of accessing mental healthcare services. This apparent lack of inclusivity highlights the need for researchers to recognize the heterogeneity of sexual and gender minority populations and the requirement for in-depth consideration of the experiences of this population. A more in-depth consideration of the experience of transgender, and in particular intersex and asexual people can only be achieved through a more relevant and sophisticated strategy.

The homogeneity of current approaches to considering gender and sexual minority populations using the LGBTIQA+ acronym will be further compounded by the fluidity of sexual orientation and gender identity being reported by young people in the Writing Themselves In 4: National Report (Hill et al., Citation2021). Hill, Lyons (Hill et al., Citation2021) reports, as expected, that LGBTIQA+ young people are as diverse as any other section of the population, holding numerous intersecting identities and social positions including ethnicity, age, ableness, migration status, and socio-economic status. In considering the experience of gender and sexual minority populations it is necessary to consider intersectionality and how this applies in the context of individual identities. The use of the Lévesque Framework in this review goes some way to beginning to integrate intersectionality into how LGBTIQA+ communities experience access to mental health services. The findings in this review should be interpreted to indicate the range of issues and experiences encountered collectively.

The search was restricted to studies published in English since 2000, potentially eliminating earlier studies which may have been relevant to the topic. The inclusion/exclusion criteria imposed a requirement to exclude any studies where it was not possible to distinguish between the results pertaining to LGBTIQA+ communities and non-LGBTIQA+ communities. The evidence in this review is limited to a consideration of access to mental health services due to the specific challenges that many LGBTIQA+ populations experience in accessing mental health services, in part due to the stigma associated with both mental health conditions and identifying as a member of the LGBTIQA+ population which is further exacerbated in a rural setting. Finally, the evidence incorporates a diverse range of health systems and health service contexts, therefore the universal concerns about de-contextualization in systematic reviews remain relevant here, with the findings interpreted in this light.

Conclusion

The findings of this review reinforce the diverse challenges faced by sexual and gender minority populations residing in non-metropolitan areas, finding that the experiences of sexual and gender minorities in one country are not dissimilar in comparison with other developed countries. This review, using the framework developed by Lévesque and colleagues, for the first time in relation to mental healthcare access for sexual and gender minorities, provides further evidence of the inter-relationships in health systems. From the concept of healthcare needs, through seeking healthcare, to ultimately considering the healthcare consequences which result from the experience of mental healthcare services, this review provides further evidence and extends upon what is understood about the experience of mental healthcare for sexual and gender minorities. These findings indicate directions for future research, including advancing evidence to guide policy and practice for the provision of mental health services for sexually and gender diverse people living in rural areas; investment in strategies to attract and retain healthcare professions with expertise in the care of sexual and gender diverse people generally, and mental health specifically. Identifying tailored models of care, which are both accessible and accepting of the diverse sexual and gender minority population living in rural areas, taking account of the barriers that the population face, is essential to harnessing the existing capabilities of the rural mental health workforce.

Ethics approval statement

This declaration affirms our commitment to maintaining the highest standards of ethical conduct in academic research and ensures the credibility and objectivity of the information presented in our scoping review.

Authors’ contribution

We have conducted this research with the primary aim of contributing valuable insights to the field of mental health accessibility for sexual and gender minority populations in rural settings, guided by the principles of transparency, integrity, and impartiality.

Supplementary_Files_edited clean.docx

Download MS Word (53 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2024.2373798

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aday, L. A., & Andersen, R. (1974). A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research, 9(3), 208.

- Amos, N., Hart, B., Hill, A. O., Melendez-Torres, G. J., McNair, R., Carman, M., Lyons, A., & Bourne, A. (2023). Health intervention experiences and associated mental health outcomes in a sample of LGBTQ people with intersex variations in Australia. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 25(7), 833–846.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2024, February 27). Mental health findings for LGBTQ+ Australians. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/mental-health-findings-lgbtq-australians

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/61521da0-9892-44a5-85af-857b3eef25c1/aihw-aus-221-chapter-5-5.pdf.aspx

- Barefoot, K. N., Warren, J. C., & Smalley, K. B. (2017). Women’s health care: The experiences and behaviors of rural and urban lesbians in the USA. Rural and Remote Health, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH3875

- Blodgett, N., Coughlan, R., & Khullar, N. (2017). Overcoming the barriers in transgender healthcare in rural Ontario: Discourses of personal agency, resilience, and empowerment. International Social Science Journal, 67(225–226), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12162

- Bowman, S., Easpaig, B. N. G., & Fox, R. (2020). Virtually caring: A qualitative study of internet-based mental health services for LGBT young adults in rural Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 20(1), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5448

- Carpenter, M. (2020). Intersex human rights, sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics and the Yogyakarta principles plus 10. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(4), 516–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1781262

- Ceres, M., Quinn, G. P., Loscalzo, M., & Rice, D. (2018). Cancer screening considerations and cancer screening uptake for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 34(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.001

- Cronin, T. J., Pepping, C. A., Halford, W. K., & Lyons, A. (2021). Mental health help-seeking and barriers to service access among lesbian, gay, and bisexual Australians. Australian Psychologist, 56(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2021.1890981

- Cu, A., Meister, S., Lefebvre, B., & Ridde, V. (2021). Assessing healthcare access using the Levesque’s conceptual framework–a scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01416-3

- Daniels, N. (1982). Equity of access to health care: Some conceptual and ethical issues. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly Health and Society, 60(1), 51–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349700

- Easpaig, B. N. G., Reynish, T. D., Hoang, H., Bridgman, H., Corvinus-Jones, S. L., & Auckland, S. (2022). A systematic review of the health and health care of rural sexual and gender minorities in the UK, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Rural and Remote Health, 22(3), 1–16.

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H.-J., & Barkan, S. E. (2012). Disability among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Disparities in prevalence and risk. American Journal of Public Health, 102(1), e16–e21. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300379

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Simoni, J. M., Kim, H.-J., Lehavot, K., Walters, K. L., Yang, J., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., & Muraco, A. (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000030

- Gandy, M. E., Kidd, K. M., Weiss, J., Leitch, J., & Hersom, X. (2021). Trans* forming access and care in rural areas: A community-engaged approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312700

- Goddard, M., & Smith, P. (2001). Equity of access to health care services: Theory and evidence from the UK. Social Science & Medicine, 53(9), 1149–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00415-9

- Grant, R., & Nash, M. (2019). Young bisexual women’s sexual health care experiences in Australian rural general practice. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 27(3), 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12505

- Gulliford, M., Figueroa-Munoz, J., Morgan, M., Hughes, D., Gibson, B., Beech, R., & Hudson, M. (2002). What does ‘access to health care’ mean? Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(3), 186–188. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581902760082517

- Heng, A., Heal, C., Banks, J., & Preston, R. (2019). Clinician and client perspectives regarding transgender health: A North Queensland focus. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(4), 434–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1650408

- Henriquez, N. R., & Ahmad, N. (2021). “The message is you don’t exist”: Exploring lived experiences of rural lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ) people utilizing health care services. SAGE Open Nursing, 7, 23779608211051174. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608211051174

- Hill, A., Lyons, A., Jones, J., McGowan, I., Carman, M., Power, J., & Parsons, M. (2021). Writing Themselves in 4: The health and wellbeing of LGBTQA+ young people in Australia. New South Wales Summary Report.

- Holt, N. R., Hope, D. A., Mocarski, R., Meyer, H., King, R., & Woodruff, N. (2020). The provider perspective on behavioral health care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals in the central great plains: A qualitative study of approaches and needs. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(1), 136. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000406

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. National Academies Press (US).

- Jenkins, W. D., Walters, S., Phillips, G., II, Green, K., Fenner, E., Bolinski, R., Spenner, A., & Luckey, G. (2022). Stigma, mental health, and health care use among rural sexual and gender minority individuals. Health Education and Behavior, 51(3), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/10901981221120393

- Knutson, D., Martyr, M. A., Mitchell, T. A., Arthur, T., & Koch, J. M. (2018). Recommendations from transgender healthcare consumers in rural areas. Transgender Health, 3(1), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2017.0052

- Lévesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- Logie, C. H., Lys, C. L., Dias, L., Schott, N., Zouboules, M. R., MacNeill, N., & Mackay, K. (2019). “Automatic assumption of your gender, sexuality and sexual practices is also discrimination”: Exploring sexual healthcare experiences and recommendations among sexually and gender diverse persons in Arctic Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1204–1213. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12757

- Loo, S., Almazan, A. N., Vedilago, V., Stott, B., Reisner, S. L., Keuroghlian, A. S., & Federici, S. (2021). Understanding community member and health care professional perspectives on gender-affirming care—A qualitative study. PLOS ONE, 16(8), e0255568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255568

- Lyons, A., Hosking, W., & Rozbroj, T. (2015). Rural‐urban differences in mental health, resilience, stigma, and social support among young Australian gay men. The Journal of Rural Health, 31(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12089

- Miller, H., Welland, L., McCook, S., & Giunta, K. (2022). Wellbeing beyond binaries: A qualitative study of wellbeing in bisexual+ youth. Journal of Bisexuality, 22(3), 385–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2022.2044960

- Moallef, S., Salway, T., Phanuphak, N., Kivioja, K., Pongruengphant, S., & Hayashi, K. (2022). The relationship between sexual and gender stigma and difficulty accessing primary and mental healthcare services among LGBTQI+ populations in Thailand: Findings from a national survey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(6), 3244–3261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00740-7

- Munn, Z. (2016). Software to support the systematic review process: The Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI-SUMARI). JBI Evidence Synthesis, 14(10), 1. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-002421

- Musgrove, P. (1986). Measurement of equity in health. World Health Statistics Quarterly 1986, 39(4), 325–335.

- Oliver, A., & Mossialos, E. (2004). Equity of access to health care: Outlining the foundations for action. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58(8), 655. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.017731

- Owens, C., Hubach, R. D., Williams, D., Lester, J., Reece, M., & Dodge, B. (2020). Exploring the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) health care experiences among men who have sex with men (MSM) who live in rural areas of the Midwest. AIDS Education and Prevention, 32(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2020.32.1.51

- Penchansky, R., & Thomas, J. W. (1981). The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care, 19(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001

- Perales, F. (2019). The health and wellbeing of Australian lesbian, gay and bisexual people: A systematic assessment using a longitudinal national sample. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 43(3), 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12855

- Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 19(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277

- Price-Feeney, M., Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2019). Health indicators of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other sexual minority (LGB+) youth living in rural communities. The Journal of Pediatrics, 205, 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.059

- Przedworski, J. M., Dovidio, J. F., Hardeman, R. R., Phelan, S. M., Burke, S. E., Ruben, M. A., Perry, S. P., Burgess, D. J., Nelson, D. B., Yeazel, M. W., Knudsen, J. M., & van Ryn, M. (2015). A comparison of the mental health and well-being of sexual minority and heterosexual first-year medical students: A report from medical student changes. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 90(5), 652. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000658

- Reisner, S. L., Benyishay, M., Stott, B., Vedilago, V., Almazan, A., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2022). Gender-Affirming mental health care access and utilization among rural transgender and gender diverse adults in five Northeastern U.S. States. Transgender Health, 7(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0010

- Roberts, R., Black, G., & Hart, T. (2018). Same-sex-attracted adolescents in rural Australia: Stressors, depression and suicidality, and barriers to seeking mental health support. Rural and Remote Health, 18(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH4364

- Romanelli, M., & Hudson, K. D. (2017). Individual and systemic barriers to health care: Perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(6), 714. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000306

- Rosenkrantz, D. E., Black, W. W., Abreu, R. L., Aleshire, M. E., & Fallin-Bennett, K. (2017). Health and health care of rural sexual and gender minorities: A systematic review. Stigma and Health, 2(3), 229. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000055

- Rosenwohl-Mack, A., Tamar-Mattis, S., Baratz, A. B., Dalke, K. B., Ittelson, A., Zieselman, K., & Flatt, J. D. (2020). A national study on the physical and mental health of intersex adults in the U.S. PLoS One, 15(10), e0240088. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240088

- Saxby, K., de New, S. C., & Petrie, D. (2020). Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in healthcare use: Evidence from Australian Census-linked-administrative data. Social Science & Medicine, 255, 113027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113027

- Smith, S. K., & Turell, S. C. (2017). Perceptions of healthcare experiences: Relational and communicative competencies to improve care for LGBT people. Journal of Social Issues, 73(3), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12235

- Stenger, M. R., Stefan, B., Shauna, S., Dan, W., Barton Jerusha, E., & Thomas, P. (2017). As through a glass, darkly: The future of sexually transmissible infections among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Sexual Health, 14, 18–27.

- Vargas, N., Clark, J. L., Estrada, I. A., De La Torre, C., Yosha, N., Magaña Alvarez, M., Parker, R. G., & Garcia, J. (2022). Critical consciousness for connectivity: Decoding social isolation experienced by Latinx and LGBTQ+ youth using a multi-stakeholder approach to health equity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11080. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711080

- Walinsky, D., & Whitcomb, D. (2010). Using the ACA competencies for counseling with transgender clients to increase rural transgender well-being. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 4(3–4), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2010.524840

- Warren, J. C., Smalley, K. B., & Barefoot, K. N. (2015). Recruiting rural and urban LGBT populations online: Differences in participant characteristics between email and Craigslist approaches. Health and Technology, 5(2), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-015-0112-4

- Wheldon, C. W., Polter, E., Rosser, B. S., Bates, A. J., Haggart, R., Wright, M., Mitteldorf, D., Ross, M. W., Konety, B. R., Kohli, N., & Tatum, A. K. (2022). Prevalence and risk factors for sexually transmitted infections in gay and bisexual prostate cancer survivors: Results from the Restore-2 study. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 832508.

- Willging, C. E., Salvador, M., & Kano, M. (2006a). Brief reports: Unequal treatment: Mental health care for sexual and gender minority groups in a rural state. Psychiatric Services, 57(6), 867–870. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.867

- Willging, C. E., Salvador, M., & Kano, M. (2006b). Pragmatic help seeking: How sexual and gender minority groups access mental health care in a rural state. Psychiatric Services, 57(6), 871–874. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.871

- Wilson, T., Temple, J., Lyons, A., & Shalley, F. (2020). What is the size of Australia’s sexual minority population? BMC Research Notes, 13(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05383-w

- Zeeman, L., & Aranda, K. (2020). A systematic review of the health and healthcare inequalities for people with intersex variance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186533