ABSTRACT

In general (i.e. in heteronormative and cisgendered samples), authenticity appears protective against threats to well-being. Authenticity may also, in part, protect well-being against the minority stressors experienced by sexually minoritized (LGB; lesbian, gay, and bisexual) individuals. In this scoping review, we examined the relation between authenticity and well-being in LGB samples experiencing minority stress. We hypothesized that (i) LGB minority stress relates to decreased authenticity (i.e. inauthenticity), (ii) authenticity relates to increased well-being, and (iii) authenticity influences the relation between LGB minority stress and well-being. We identified 17 studies (N = 4,653) from systematic searches across Medline, ProQuest, PsycINFO, and Scopus using terms related to sexual identity, minority stress, authenticity, and well-being. In almost all studies, proximal (but not distal) stress was associated with inauthenticity, and inauthenticity with decreased well-being. In all but one study, the association between proximal stress and well-being was associated with inauthenticity. Although these results are consistent with our hypotheses, the included studies were limited in scope and heterogenous in their methods, instruments, and samples, restricting conclusions regarding mediation or moderation. The results require replication, well-powered direct comparisons between LGB and non-LGB samples, and consideration of the varied ways authenticity can be conceptualized and measured.

KEYWORDS:

LGB (lesbian, gay, and bisexual) individuals report lower psychological well-being more often and intensely than non-LGB individuals (Centre for American Progress, Citation2021; Statistics Canada, Citation2021; Stonewall, Citation2018). One well-evidenced explanation for this is the prejudice uniquely experienced such individuals, termed minority stress (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003). However, according to an emerging perspective, minority stress experience may decrease well-being by motivating LGB (compared to non-LGB) individuals to behave inconsistently with their true self (i.e., inauthenticity; Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Sedikides et al., Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2008). In this scoping review, we first asked (i) whether minority stress is negatively related to authenticity in LGB samples. Well-being is robustly related to authenticity in undergraduate or general samples, and so we asked (ii) whether authenticity is positively related to well-being in LGB samples. Finally, we asked (iii) whether inauthenticity relates to the association between minority stress and (poor) well-being.

Authenticity

Historically, authenticity has been considered trait-like, dependent on how connected/disconnected one is to their “self” (Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Wood et al., Citation2008). In keeping with this perspective, the most frequently used measure of authenticity in general samples assesses whether individuals would consider themselves to be accepting of external influence, alienated from their true self, and/or able to live authentically over their lifetimes (Wood et al., Citation2008). Similarly, the most frequently used measure of authenticity in LGB samples (the Authenticity sub-scale of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Positive Identity Measure; LGB-PIM; Riggle et al., Citation2014) focuses on trait authenticity as it relates to one’s sexual identity. There is no research on differences in the reported authenticity of LGB individuals when measured via the Wood Authenticity Scale or the Authenticity sub-scale of the LGB-PIM.

Contemporary conceptualizations of authenticity focus on contexts in which individuals can be authentic rather than on authenticity as a trait (Cooper et al., Citation2018; Sedikides et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). According to the State Authenticity as Fit to the Environment (SAFE; Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018) model, individuals evaluate whether their authentic self fits the environment. The SAFE model recognizes that, due to stress, socially disadvantaged and minoritised identity groups likely more often experience environmental misfit (perceptions that the self does not “fit” the environment) than general samples (Aday & Schmader, Citation2019).

LGB minority stress and authenticity

Minority stress can be either distal or proximal (Meyer, Citation2003). Distal stressors (e.g., discrimination, stigma, violence, microaggressions) are interpersonal stressors perpetrated by others, whereas proximal stressors (e.g., internalized homophobia, expectation of LGB identity-based rejection, concealment) involve intrapersonal stress perpetrated against oneself. These two types of stressors are causally related: proximal stressors often emerge, at least in part, as a product of distal stress (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009), when external negative perceptions are internalized and integrated into one’s self-concept (Jerald et al., Citation2017).

All LGB individuals are vulnerable to minority stress, although some sexual identities comparatively less so; lesbian and gay identities are theorized to gain some protection from adherence to the heterosexual/homosexual binary (Callis, Citation2014; Roseneil, Citation2002). The heterosexual/homosexual binary generally enforces “binegativity” (stressors uniquely faced by bisexual-identifying individuals; Dyar et al., Citation2014; Yost & Thomas, Citation2012). Examples include perpetuation of the misconception that fluid sexualities are not real identities and that bisexuality is an impermanent, half-way point between heterosexuality and homosexuality (Hayfield et al., Citation2014; Katz-Wise & Hyde, Citation2012; Yost & Thomas, Citation2012). Research on stress experiences associated with plurisexualities (comprising attraction to any/all genders) other than bisexuality is limited, though pansexual, asexual, and queer identifying individuals likely experience heightened vulnerability to minority stress for similar reasons (Feinstein et al., Citation2021; Mitchell et al., Citation2015; Morandini et al., Citation2022).

There is a conceptual crossover between the proximal stressor of concealment and state presentations of an inauthentic, false self. Both comprise a censored self-presentation and can the risk of distal minority stress experiences (Brennan, Citation2021; Huang & Chan, Citation2022). However, it is necessary to distinguish between the two and empirically explore both as independent, though related, constructs. Concealment/disclosure refers to an individual’s level of openness about their LGB identity, whereas state inauthenticity is the global judgment (inclusive of but beyond their LGB identity) that one cannot truthfully present all facets of their self in an environment. An LGB individuals’ state (in)authentic presentation is likely to inform decisions to conceal/disclose their identity but may not hinge on such. For example, authenticity may be maintained while concealing if the environment fits other elements of the individual’s personality, and likewise disclosure may not guarantee authenticity if the environment is ill-fitting of the individual in other areas (Riggle et al., Citation2017). Behaviors like code-switching (monitoring/changing one’s language based on their environment; Asakura, Citation2017) or compartmentalization (separating one’s sexual identity from the rest of the self; Jaspal, Citation2021) may also be enacted within or between concealment and inauthenticity.

These findings suggest that minority stress experiences may signal that the environment is not receptive to or does not fit with one’s presentation of self as an LGB individual. The SAFE model of state authenticity posits that this signaling likely encourages inauthentic presentations of an adjusted, censored self that does fit the environment (Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018). Put otherwise, minority stress might be linked to purposefully behaving inauthentically: adopting a socially advantageous gender/sexuality identity if one feels their authentic gender/sexuality identity should not, or cannot, be embraced in the given environment (Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Sedikides et al., Citation2019; Wood et al., Citation2008). This inauthenticity, although potentially adaptive in limiting exposure to distal stress, may be conducive to further proximal stress, should one become alienated from or resentful of their true identity. In all, both authenticity and inauthenticity among LGB individuals likely have implications for well-being similar, if not more severe, to those reported by general samples, as we discuss next.

Well-being and (in)authenticity

Contemporary approaches to conceptualizing well-being focus on pleasure and the pursuit of positive emotional states/avoidance of negative states (i.e., hedonic well-being) or fulfillment and the pursuit of purpose (i.e., eudaimonic well-being). Both types of well-being are multifaceted: hedonic well-being is typically conceptualized as a subjective current happiness (i.e., satisfaction with life; Diener et al., Citation1985), as well as more frequent and intense experiences of positive affect relative to negative affect. In this review, we define positive affect to include adaptive psychological adjustment, and negative affect to include psychological maladjustments such as depression and psychological distress. Eudaimonic well-being, on the other hand, is typically conceptualized as the more existential appraisal of psychological well-being and functioning (i.e., perception of purpose and life meaningfulness; Ryff, Citation1989).

In non-LGB (e.g., undergraduate and community convenience) samples, authenticity is consistently associated with eudaimonic well-being. Individuals who experience higher authenticity report greater self-efficacy, perceived wellness, competence, autonomy, and optimism for the future (Sedikides & Schlegel, Citation2024; Sutton, Citation2020). Conversely, inauthenticity is associated with poor eudaimonic well-being, including vulnerability to psychopathology (Sedikides & Schlegel, Citation2024).

Authenticity is also related to hedonic well-being. Individuals high in trait authenticity report more positive affect, less negative affect, and greater subjective well-being (Kifer et al., Citation2013; Thomaes et al., Citation2017; see Sedikides & Schlegel, Citation2024). In the context of ecological momentary assessment, authenticity conduces to more positive affect in response to social interactions with close others (Venaglia & Lemay, Citation2017). Finally, authenticity is causally related to both eudaimonic and hedonic well-being, as suggested by studies that experimentally manipulate authenticity (Kelley et al., Citation2022, Study 4). Taken together, authenticity is linked to both eudaimonic and hedonic well-being across contexts.

The associations between authenticity and well-being are particularly relevant to LGB individuals, who experience lower hedonic well-being via depression, psychological distress, and lower life satisfaction compared to non-LGB individuals (Centre for American Progress, Citation2021; Statistics Canada, Citation2021; Stonewall, Citation2018). LGB individuals also report lower eudaimonic well-being (social connectedness and self-esteem) compared to non-LGB individuals (Checa et al., Citation2022; Greene & Britton, Citation2012). Hatzenbuehler’s (Citation2009) psychological mediation framework suggests that this decreased well-being is due, in part, to minority stress experience (Baams et al., Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2022; Chodzen et al., Citation2019) and the inhibitive influence these stressors have on affective and psychological processes. We contend that authenticity is a yet underrecognized psychological process, inhibited by minority stress experience; this inhibition contributes to lower well-being.

The current review

Based on our literature review, we offer three hypotheses: (i) LGB minority stress is related to decreased authenticity (i.e., inauthenticity); (ii) LGB authenticity is related to increased well-being; (iii) LGB authenticity influences the relation between minority stress and well-being. We aimed to conduct a systematic analysis of the literature, but this was unfeasible due to lack of research and replication, non-peer-reviewed findings, and heterogeneity of both variable operationalization and methodology. Therefore, we proceeded with a scoping review. Such reviews are beneficial in heterogenous fields of research with an abundance of unpublished findings that render systematic comparisons difficult, if not impossible (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

Method

Design

We conducted our scoping review using Covidence data extraction software (Covidence Systematic Review Software, Citation2022). We asked how authenticity relates to LGB individuals’ experience of minority stressors and well-being. Relying on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis framework (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., Citation2018), we implemented a six-step approach (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005): (i) research question identification; (ii) inclusion and exclusion criteria identification; (iii) study selection; (iv) data charting; (v) data summarizing; (vi) data reporting.

Search strategy

Two coauthors (ER and KS) independently conducted a full-text literature search in December 2022 using the following key terms: LGB* OR “sexuality diverse” OR “sexual orientation” OR lesbian OR gay OR bisexual OR queer OR questioning OR asexual OR demisexual OR pansexual OR WSW OR MSM AND “minority stress” AND authentic* OR inauthentic* AND well*being OR “mental health” OR “psychological distress” OR affect. Three coauthors (ER, KS, and ML) independently screened articles by title and abstract. This search was updated in May 2024.

Our search included all articles published up to 2024 across four databases: PsycINFO, Medline, Scopus, and ProQuest. We chose these databases for their breadth of coverage of quantitative and qualitative psychological research. We manually checked the references and citations of relevant papers with both Connected Papers and Research Rabbit to find any other relevant works. We also included unpublished literature. We implemented the following inclusion criteria for study selection: (i) primary research; (ii) LGB sample; (iii) analysis of relations among (in)authenticity, minority stress, and well-being; (iv) English language.

Results

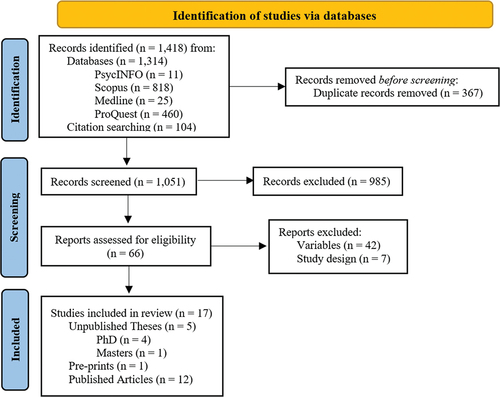

Database searches yielded 1,314 sources, with an additional 104 identified by reference list searching (N = 1,418). We removed 367 duplicates, leaving 1,051 studies to screen. Upon screening titles, abstracts, and full texts, we excluded 1,038 studies for the following reasons: (i) not a LGB sample; (ii) did not measure authenticity; (iii) did not measure well-being; (iv) did not analyze primary data; (v) not in English language. We excluded studies focused solely on gender minorities but included studies focused on solely sexual minorities and studies sampling both gender and sexual minorities. We provide more detailed reasons for exclusion in Supplementary Material. The final sample consisted of 17 studies: 11 peer-reviewed journal articles, four unpublished PhD theses, one unpublished Master’s thesis, one pre-print. The PRISMA-ScR (Moher et al., Citation2009) flow diagram maps the screening and selection process (). Two coauthors (ER, ML) conducted data extraction (). These data comprised title, author, year, country, focus population, number and description of participants, measures, and analyses.

Table 1. Data extraction from included studies (n = 17).

Is LGB minority stress related to authenticity?

Eleven studies addressed this question. Of these, two were qualitative. Some LGB individuals from the USA reported feeling pressure to present inauthentically (to misrepresent or hide their identities) in order to maintain economic choice in employment, housing, and medical services (Levitt et al., Citation2016). LGBTQ+ youth in the USA also reported that experiences of intolerance and hostility prevented them from living authentically (Rand & Paceley, Citation2022).

Nine quantitative studies addressed this question. Proximal stressors () were examined in all eight studies that assessed minority stress. Despite variation in stressors assessed, measures used, design, and sample characteristics, proximal stressors were consistently associated with inauthenticity. Across five studies, internalized homophobia was related to inauthenticity. These studies tested bisexual and pansexual individuals in Hong Kong (internalized homophobia here referred to as sexual identity negation; Chan & Leung, Citation2023), gay men in the USA (Birichi, Citation2015), LGBTQ individuals in Canada (Collict, Citation2020), LGBTQ individuals in the USA (Fredrick et al., Citation2020), and LGB individuals in Italy (Petrocchi et al., Citation2020). Also, across five studies, concealment/disclosure was related to inauthenticity. These studies tested gay men in the USA (Birichi, Citation2015), bisexual men and women in the USA (Brownfield & Brown, Citation2022), LGBTQ individuals in the USA (Brennan, Citation2021; Riggle et al., Citation2017), as well as LGB individuals in Hong Kong (Huang & Chan, Citation2022). Expectations of LGB identity-based rejection were unrelated to (in)authenticity (Birichi, Citation2015).

Table 2. LGB minority stressors discussed in this review.

Distal stressors () were examined in three of the eight cross-sectional studies assessing minority stress but were generally unassociated with authenticity. These null effects were reported in studies examining discrimination (Birichi, Citation2015), violence, and microaggressions (Collict, Citation2020). In a cross-sectional study of LGBTQ individuals in Canada, public stigma was associated with inauthenticity (Fredrick et al., Citation2020). However, the measure used (Perceived Stigma Scale; Mickelson, Citation2001) primarily reflects the internalized perception of stigma and likely captures proximal stressors (e.g., internalized homophobia).

In summary, these results provide partial support for our first hypothesis, insofar as proximal, but not distal, stressors are associated with (in)authenticity. We note that eight of these nine studies assessed LGB-specific authenticity with the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Positive Identity Measure (Riggle et al., Citation2014). The remaining study (Birichi, Citation2015) assessed authenticity with a general scale (e.g., the Wood Authenticity Scale; Wood et al., Citation2008).

Is authenticity related to increased well-being among LGB individuals?

Fourteen of seventeen studies addressed this question. Of these, two were qualitative. Living authentically was raised by LGB focus group participants as a theme impacting their psychological well-being. Participants discussed the “freedom” and “comfortability” of “being whoever you wanted to be and doing what you wanted to do” (Anderson, Citation2018, p. 9). Communicating authentically emerged as an element of growth-fostering in social interactions between gay men, wherein “self-disclosing” and “just being present” were thought to increase personal growth and resilience (Williams, Citation2023).

Of the remaining 12 quantitative studies, eight tested associations between authenticity and hedonic well-being. Authenticity was consistently, positively associated with hedonic well-being. Positive associations between authenticity and hedonic well-being were observed for trait positive affect (Birichi, Citation2015), satisfaction with life (Birichi, Citation2015; Fletcher & Everly, Citation2021; Huang & Chan, Citation2022), general hedonic well-being (e.g., fewer feelings of crying; Brennan, Citation2021), and overall quality of life (which also included eudaimonic well-being; Fredrick et al., Citation2020). Authenticity was also associated with less negative affect (Birichi, Citation2015), as well as depression and stress (but not anxiety) symptoms (Chan & Leung, Citation2023; Collict, Citation2020; Riggle et al., Citation2017).

Across seven studies, authenticity was consistently, positively associated with eudaimonic well-being. These positive associations were observed for overall psychological well-being (Brennan, Citation2021; Brownfield & Brown, Citation2022; Fredrick et al., Citation2020; Huang & Chan, Citation2022; Petrocchi et al., Citation2020; Riggle et al., Citation2017) and domains of eudaimonic well-being: autonomy (Collict, Citation2020; Rostosky et al., Citation2018), environmental mastery (Collict, Citation2020; Rostosky et al., Citation2018), personal growth/self-actualization (Collict, Citation2020; Rostosky et al., Citation2018), supportive social relationships (Birichi, Citation2015; Collict, Citation2020; Rostosky et al., Citation2018), purpose in life (Birichi, Citation2015; Collict, Citation2020; Rostosky et al., Citation2018), self-acceptance (Collict, Citation2020; Rostosky et al., Citation2018). The results are consistent with our second hypothesis that the positive association between authenticity and well-being observed in general samples is also found in LGB individuals. These associations were evident in studies using not only (and mostly) population-specific measures of authenticity (Riggle et al., Citation2014), but also general authenticity scales (Wood et al., Citation2008).

Does authenticity impact the LGB minority stress—Well-being association?

Twelve studies addressed this question. We obtained mixed evidence that authenticity influences the (negative) relation between the experience of proximal minority stressors and well-being. In the studies assessing internalized homophobia, (in)authenticity mediated the association between this minority stressor and hedonic well-being (e.g., satisfaction with life, positive affect, negative affect; Birichi, Citation2015; Chan & Leung, Citation2023) as well as eudaimonic well-being (e.g., autonomy, environmental mastery, self-acceptance; Birichi, Citation2015; Collict, Citation2020; Fredrick et al., Citation2020). Mediation of the authenticity—well-being link was observed both for domain-general (Birichi, Citation2015; Chan & Leung, Citation2023; Fredrick et al., Citation2020) and domain-specific measures (e.g., autonomy, environmental mastery, self-acceptance; Collict, Citation2020). In all four studies, authenticity weakened the link between internalized homophobia and well-being. Authenticity also emerged as the most significant predictor of well-being, alongside positive perceptions of self and social safeness, whereas internalized homophobia (here, called internalized sexual stigma) was not significant in the final regression model (Petrocchi et al., Citation2020). It is unclear whether internalized homophobia was a significant predictor at an earlier stage in the model, becoming non-significant due to the presence of other variables, though these findings demonstrate the same pattern as above: the relation between authenticity and well-being seemingly withstands internalized homophobia.

Although expectations of rejection were associated with lower hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, this effect was not mediated by (in)authenticity (Birichi, Citation2015). Further, in moderated mediation analysis, anticipated binegativity on well-being was not buffered by authenticity among bisexual individuals (Vanmattson, Citation2023).

Concealment (and its inverse, disclosure) was consistently associated with lower (and, correspondingly, greater) hedonic (Birichi, Citation2015; Brennan, Citation2021) as well as eudaimonic (Birichi, Citation2015; Brownfield & Brown, Citation2022; Huang & Chan, Citation2022; Riggle et al., Citation2017) well-being. One study used hierarchical regressions to examine whether concealment or authenticity predicts both psychological well-being and depressive symptoms (Riggle et al., Citation2017). Concealment emerged as a negative predictor of psychological well-being and a positive predictor of depressive symptoms, with both effects remaining significant once authenticity was entered into the model. (In)authenticity fully or partially mediated the association between concealment and overall hedonic well-being (Birichi, Citation2015). Mediation was also reported for overall (Birichi, Citation2015—partial mediation; Brownfield & Brown, Citation2022—fully mediated) eudaimonic well-being. Another study examined whether authenticity moderated the association between concealment and hedonic well-being (i.e., psychological distress): this association was stronger in participants with lower (compared to higher) authenticity (Brennan, Citation2021). All but one of the eight studies involved a cross-sectional design. The longitudinal study reported that concealment predicted poorer hedonic and eudaimonic well-being 1 year later (Huang & Chan, Citation2022). However, this association was not mediated by authenticity.

We obtained limited evidence that (in)authenticity consistently played a role in the associations between distal minority stress and well-being. Mediation was only observed for the association between public stigma and overall well-being (Fredrick et al., Citation2020), but there was no direct effect for public stigma and well-being. Although victimhood of crime was weakly associated with poorer autonomy, and microaggressions were weakly associated with poorer eudaimonic well-being (i.e., environmental mastery, positive social relationships, and self-acceptance), these stressors were unassociated with (in)authenticity (see above), and authenticity did not mediate any associations (Collict, Citation2020). Discrimination was only linked to the negative affect facet of hedonic well-being and was not mediated by authenticity (Birichi, Citation2015).

In moderated mediation analysis, binegativity on well-being was not buffered by authenticity among bisexual individuals (Vanmattson, Citation2023). However, at the 1-month follow-up of a study of bisexual and pansexual individuals, high authenticity predicted decreased suicidal ideation when facing high frequency of antibisexual discrimination and low authenticity predicted increased suicidal ideation (Katz et al., Citation2023). After 2 months, low authenticity remained predictive of increased suicidal ideation, but high authenticity was no longer predictive decreased suicidal ideation. Average authenticity was non-predictive at both time points.

These results provide mixed support for our third hypothesis, namely that LGB authenticity influences the relation between minority stress and well-being. However, significant mediation appears to be limited to proximal minority stressors in studies using measures of distal stressors with a substantial internalized component (Mickelson, Citation2001) or in bisexual populations. All but two studies (Huang & Chan, Citation2022; Katz et al., Citation2023) were cross-sectional, precluding appropriate testing of mediation (Maxwell & Cole, Citation2007). Although mediation was nonspecific to hedonic or eudaimonic well-being, the studies reviewed typically did not distinguish between facets within these domains.

Discussion

Authenticity fosters eudaimonic and hedonic well-being for those with socially advantaged identities (Aday et al., Citation2024; Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018). The reverse may be true for those with disadvantaged social identities. The proximal and distal stressors that accompany these social identities may reduce authenticity and well-being. In the current scoping review, we evaluated support for these hypotheses in the context of LGB individuals. Although only 17 studies were eligible for inclusion, their findings are broadly consistent with our hypotheses: (i) LGB proximal stress is associated with decreased authenticity (i.e., inauthenticity); (ii) authenticity is related to higher hedonic and eudaimonic well-being for LGB individuals; (iii) authenticity influences the association between proximal minority stress and well-being.

General findings

Our findings indicate that the associations among proximal minority stress, authenticity, and well-being apply more to domain-general than domain-specific well-being. Although some studies only relied on domain-general hedonic or eudaimonic well-being, their results were consistent with other studies relying on domain-specific well-being (Collict, Citation2020). Moreover, regardless of type of proximal stressor, authenticity mediated the association between exposure to proximal minority stress and well-being.

These domain-general mediation effects were observed in the four studies that assessed internalized homophobia as well as hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (Birichi, Citation2015; Chan & Leung, Citation2023; Collict, Citation2020; Fredrick et al., Citation2020). The effects are consistent with literature showing that internalized homophobia predicts inauthenticity, and inauthenticity predicts decreased well-being (Gibbs & Goldbach, Citation2015; Li & Samp, Citation2019). For gay men and plurisexuals, authenticity mediated the relation between concealment and well-being (Birichi, Citation2015; Brownfield & Brown, Citation2022; Feinstein et al., Citation2021; Riggle et al., Citation2017). Further, authenticity mediated the relation between disclosure and well-being (Brownfield & Brown, Citation2022), consistent with findings that disclosure is associated with authenticity (Feinstein et al., Citation2020).

For lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals, authenticity moderated the relation between concealment and well-being (Brennan, Citation2021). A longitudinal study, however, reported that concealment is unassociated with authenticity in general lesbian, gay, and bisexual samples across time (Huang & Chan, Citation2022). Expectation of identity-based rejection was associated with lowered well-being but was unrelated to authenticity for LGB samples (Birichi, Citation2015; Vanmattson, Citation2023).

We did not find evidence that authenticity mediates the relation between distal stressors and well-being for lesbian or gay individuals (Birichi, Citation2015; Collict, Citation2020; Fredrick et al., Citation2020). However, authenticity mediated the relation between suicidal ideation and anti-bisexual discrimination (Katz et al., Citation2023). This pattern highlights the differing experiences of groups within the LGB community and suggests that bisexual individuals face unique challenges (Hayfield et al., Citation2014; Katz-Wise & Hyde, Citation2012; Yost & Thomas, Citation2012), possibly increasing the utility of authenticity as a resilience factor.

Broadly, our review highlighted that LGB individuals’ authenticity is largely unrelated to distal stressors but negatively related to proximal stressors. Other aspects of distal stress experience, such as social alienation or low sense of belonging, may serve as links to negative well-being outcomes (Garcia et al., Citation2020). Further, the differential relations of distal versus proximal stress with authenticity may be partly explained by the fact that self-directed positive affect is associated with higher authenticity/increases authenticity (Cooper et al., Citation2018; Fleeson & Wilt, Citation2010; Lenton et al., Citation2013). Proximal stress, the internalization of prejudice, consists of self-directed negative affect and, as such, is related to low authenticity. Distal stress, however, is not necessarily related to self-directed negative affect, given that some individuals may be more resistant to this kind of stress. Therefore, these individuals may not be as vulnerable to presenting inauthentically following distal stress experience. Yet, research indicates that distal stress is conducive to proximal stress (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009; Meyer, Citation2003), possibly culminating ultimately in inauthenticity. Authenticity might begin to decrease when distal stress is internalized into proximal stress.

Interpretation of results involving mediation is challenging. Only two of 17 studies used longitudinal designs. Without longitudinal studies or experimental manipulations, it is hard to determine whether the observed effects of proximal stress mediation are due to proximal stress influencing authenticity, which buffers against well-being, or whether authenticity prevents the development of proximal stressors; or indeed, whether reduced well-being, particularly eudaimonic, leads to lower authenticity (Smallenbroek et al., Citation2017), thereby contributing to the development of proximal minority stressors. The use of cross-sectional designs, lack of experimental evidence, or statistical methods that can support causal inferences (Directed Acyclic Graphs [DAGs]; Moffa et al., Citation2017), renders each of these models a plausible alternative to those we discussed. The issue is further complicated by the heterogeneity in the measures of minority stress and well-being and conceptualizations of authenticity in the included studies. We consider these issues below.

Recommendations and future directions

Measuring authenticity

Eleven of the seventeen included studies assessed authenticity using an LGB-identify-specific measure, the Authenticity subscale within the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Positive Identity Measure (Riggle et al., Citation2014). Although we acknowledge the validity of this and other similar LGB-specific measures, especially given the centrality of gender and sexual identity for LGB individuals, using this scale to capture general authenticity through an LGB lens may be unnecessarily reductive. Many of the items within this subscale seem to capture comfort in one’s LGB identity (e.g., “I have a sense of inner peace about my LGBT identity,” “I am comfortable with my LGBT identity”). Even items that more clearly assess the subjective sense or behaving authentically appear to capture the concealment/disclosure dichotomy of outness (e.g., “I am honest with myself about my gender and/or sexual orientation,” “I feel I can be honest and share my LGBT identity with others”). Initial validation efforts resulted in relatively modest correlations between the scale and more general measures of authenticity (Riggle et al., Citation2014), suggesting a limited crossover between the constructs captured in the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Positive Identity Measure and the Authenticity Scale (Wood et al., Citation2008). Collectively, these items function well as an authenticity-adjacent subscale within a scale designed to assess LGB positive identity but do not align well with general measures of authenticity.

Given that the standardized non-LGB specific measures of authenticity are relatively short but would greatly aid between-group comparison and generalization, we recommend their inclusion alongside identity-specific scales in future studies. At minimum, inclusion of these measures will allow for more rigorous testing of theory-driven hypotheses about minority stress, authenticity, and well-being. For example, need for autonomy (defined by self-determination theory as a sense of choice and ownership in one’s behavior; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) is predictive of identity-specific authenticity for LGB individuals (Clements, Citation2023), but may be related only to the general authenticity of non-LGB individuals.

Distinguishing between forms of authenticity

Twelve of the reviewed studies (those using the Wood and LGB-PIM measures; Riggle et al., Citation2014; Wood et al., Citation2008) assessed trait as opposed to state authenticity (Sedikides et al., Citation2019). Our conclusions corroborate with those from general samples linking trait authenticity to positive affect (Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Sedikides & Schlegel, Citation2024), as proximal stress was associated with lower authenticity (Birichi, Citation2015; Brownfield & Brown, Citation2022; Collict, Citation2020; Fletcher & Everly, Citation2021; Petrocchi et al., Citation2020; Riggle et al., Citation2017). For LGB individuals, trait authenticity may not be sufficient to maintain an authentic presentation or to protect well-being, as environmental factors (e.g., distal minority stressors) make it intrinsically difficult or even unsafe to present oneself authentically. We recommend that future research examines state authenticity and explores how contextual/environmental characteristics may influence LGB presentations of authenticity. We also recommend that future research compares the frequency of variation in (in)authenticity between LGB and non-LGB individuals to quantify the impact of minority stressor experience on (in)authentic presentation.

Comparing LGB with non-LGB individuals

None of the studies included non-LGB individuals. That is, it is unclear if authenticity is more important for LGB individuals compared to non-LGB individuals (or relative to other minoritized individuals). Direct comparisons between LGB and non-LGB individuals are necessary from both theoretical and empirical standpoints (Schmader & Sedikides, Citation2018). Developing more precise estimates of why, in which contexts, and for whom authenticity is important will facilitate testing theoretical models that focus on minoritized groups. This approach would also allow for the identification of when authenticity is feasible and likely to occur.

The experiences of gender minority individuals

We found some evidence of associations among minority stress, authenticity, and well-being for sexual minority individuals. These relationships also exist for gender minority individuals (Clements, Citation2023; Osmetti & Allen, Citation2023; Tebbe et al., Citation2022) though nuanced by the impacts of unique stressors (e.g., the non-concealable nature of gender identity; Bates et al., Citation2020; D’haese et al., Citation2016). We ran an additional exploratory systematic search focusing on gender minority stress and found sufficient literature to support a dedicated review (see Supplementary Information for further detail). Such a review will aid understanding of diversities within the broader gender and sexuality diverse community.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations that can be addressed by follow-up scoping or meta-analytic reviews. We examined only English-language research, presenting cross-cultural evidence. Samples were also restricted in age, mostly demonstrative of a midlife demographic. Our inclusion of unpublished literature may raise the question of the quality of included studies. Although this issue is not typically forbidding in scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005), we engaged in critical appraisal as needed.

Conclusion

Research is in the early stages of testing the role of authenticity in minority stress and well-being among LGB samples. Authenticity appeared to protect well-being against proximal minority stressors, but there was not enough evidence to draw a preliminary conclusion on whether authenticity protects against distal minority stressors.

Ethical approval

This study was defined as negligible risk by the Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee, and so no ethical approval was necessary.

LGB_Auth_Scoping_SupplementaryInfo (1) clean.docx

Download MS Word (20.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2024.2378738.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aday, A., Guo, Y., Mehta, S., Chen, S., Hall, W., Götz, F. M., Sedikides, C., & Schmader, T. (2024). The SAFE model: State authenticity as a function of three types of fit. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672231223597. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231223597

- Aday, A., & Schmader, T. (2019). Seeking authenticity in diverse contexts: How identities and environments constrain “free” choice. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(6), e12450. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12450

- Anderson, J. (2018). Creating LGBT+ identities and well-being: A qualitative study. Manchester Metropolitan University’s Research Repository. https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/621667/

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Asakura, K. (2017). Paving pathways through the pain: A grounded theory of resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27(3), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12291

- Baams, L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038994

- Bates, T., Thomas, C. S., & Timming, A. R. (2020). Employment discrimination against gender diverse individuals in Western Australia. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 40(3), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-04-2020-0073

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Ranieri, W. F. (1988). Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(4), 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4<499:AID-JCLP2270440404>3.0.CO;2-6

- Birichi, D. K. (2015). Minority stress and well-being in adult gay men: The mediating role of authenticity [ Ph.D., University of Miami]. ProQuest. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1718489329/abstract/DEDDD264253C491FPQ/1

- Bonomi, A. E., Patrick, D. L., Bushnell, D. M., & Martin, M. (2000). Validation of the United States’ version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) instrument. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00123-7

- Brennan, J. M. (2021). Hiding the authentic self: Concealment of gender and sexual identity and its consequences for authenticity and psychological well-being [ Ph.D., University of Montana]. ProQuest. https://www.proquest.com/openview/66d0dc6f353fcfad9fa83352e195ad6a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Brewster, M. E., & Moradi, B. (2010). Perceived experiences of anti-bisexual prejudice: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021116

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books.

- Brownfield, J. M., & Brown, C. (2022). The relations among outness, authenticity, and well-being for bisexual adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000390

- Callis, A. S. (2014). Bisexual, pansexual, queer: Non-binary identities and the sexual borderlands. Sexualities, 17(1–2), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460713511094

- Centre for American Progress. (2021). Protecting and advancing health care for transgender adult communities. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/protecting-advancing-health-care-transgender-adult-communities/

- Chan, R. C. H., & Leung, J. S. Y. (2023). Monosexism as an additional dimension of minority stress affecting mental health among bisexual and pansexual individuals in Hong Kong: The role of gender and sexual identity integration. Journal of Sex Research, 60(5), 704–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2119546

- Checa, I., DiMarco, D., & Bohórquez, M. R. (2022). Measurement invariance of the satisfaction with life scale by sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(6), 2891–2897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02240-0

- Chen, D., Ying, J., Zhou, X., Wu, H., Shen, Y., & You, J. (2022). Sexual minority stigma and nonsuicidal self-injury among sexual minorities: The mediating roles of sexual orientation concealment, self-criticism, and depression. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 19(4), 1690–1701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00745-4

- Chodzen, G., Hidalgo, M. A., Chen, D., & Garofalo, R. (2019). Minority stress factors associated with depression and anxiety among transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 467–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.006

- Clements, Z. (2023). The role of authenticity in the link between self-determination, gender minority stress, psychological well-being and distress in transgender, nonbinary, and gender expansive individuals. University of Kentucky Libraries. https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2023.252

- Collict, D. T. (2020). Minority stress, positive sexual minority identity and Eudaimonic well-being experiences among sexual and gender-diverse communities [ M.A., University of Toronto]. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/101048?mode=full

- Cooper, A. B., Sherman, R. A., Rauthmann, J. F., Serfass, D. G., & Brown, N. A. (2018). Feeling good and authentic: Experienced authenticity in daily life is predicted by positive feelings and situation characteristics, not trait-state consistency. Journal of Research in Personality, 77, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.09.005

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. (2022). Computer software. Veritas Health Innovation.

- D’haese, L., Dewaele, A., & Van Houtte, M. (2016). The relationship between childhood gender nonconformity and experiencing diverse types of homophobic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(9), 1634–1660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515569063

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dyar, C., Feinstein, B. A., & London, B. (2014). Dimensions of sexual identity and minority stress among bisexual women: The role of partner gender. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000063

- Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 180, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

- Feinstein, B. A., Hurtado, M., Jr., Dyar, C., & Davila, J. (2021). Disclosure, minority stress, and mental health among bisexual, pansexual, and queer (Bi+) adults: The roles of primary sexual identity and multiple sexual identity label use. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000532

- Feinstein, B. A., Xavier Hall, C. D., Dyar, C., & Davila, J. (2020). Motivations for sexual identity concealment and their associations with mental health among bisexual, pansexual, queer, and fluid (bi+) individuals. Journal of Bisexuality, 20(3), 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2020.1743402

- Fleeson, W., & Wilt, J. (2010). The relevance of big five trait content in behavior to subjective authenticity: Do high levels of within-person behavioral variability undermine or enable authenticity achievement? Journal of Personality, 78(4), 1353–1382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00653.x

- Fletcher, L., & Everly, B. A. (2021). Perceived lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) supportive practices and the life satisfaction of LGBT employees: The roles of disclosure, authenticity at work, and identity centrality. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 94(3), 485–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12336

- Fredrick, E. G., LaDuke, S. L., & Williams, S. L. (2020). Sexual minority quality of life: The indirect effect of public stigma through self-compassion, authenticity, and internalized stigma. Stigma and Health, 5(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000176

- Garcia, J., Vargas, N., Clark, J. L., Magaña Álvarez, M., Nelons, D. A., & Parker, R. G. (2020). Social isolation and connectedness as determinants of well-being: Global evidence mapping focused on LGBTQ youth. Global Public Health, 15(4), 497–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1682028

- Gibbs, J. J., & Goldbach, J. (2015). Religious conflict, sexual identity, and suicidal behaviors among LGBT young adults. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(4), 472–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004476

- Greene, D. C., & Britton, P. J. (2012). Stage of sexual minority identity formation: The impact of shame, internalized homophobia, ambivalence over emotional expression, and personal mastery. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 16(3), 188–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2012.671126

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441

- Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Halliwell, E. (2014). Bisexual women’s understandings of social marginalisation: ‘The heterosexuals don’t understand us but nor do the lesbians. Feminism & Psychology, 24(3), 352–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514539651

- Herek, G. M., Cogan, J. C., Gillis, J. R., & Glunt, E. K. (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay & Lesbian Medical Association, 2(1), 17–25.

- Huang, Y., & Chan, R. (2022). Effects of sexual orientation concealment on well-being among sexual minorities: How and when does concealment hurt? Journal of Counselling Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000623

- Jackson, S. D., & Mohr, J. J. (2016). Conceptualizing the closet: Differentiating stigma concealment and nondisclosure processes. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(1), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/SGD0000147

- Jaspal, R. (2021). Identity threat and coping among British South Asian gay men during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sexuality & Culture, 25(4), 1428–1446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09817-w

- Jerald, M. C., Cole, E. R., Ward, L. M., & Avery, L. R. (2017). Controlling images: How awareness of group stereotypes affects Black women’s well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(5), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000233

- Kalb, N. (2017). Coping motives as a mediator in the relationship between LGBQ-specific stressors and alcohol consumption and consequences among LGBQ emerging adults [ M.A., University of Toronto]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1884216945/abstract/C59B25DEC16849B7PQ/1

- Katz, B. W., Chang, C. J., Dorrell, K. D., Selby, E. A., & Feinstein, B. A. (2023). Aspects of positive identity buffer the longitudinal associations between discrimination and suicidal ideation among bi+ young adults. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 91(5), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000788

- Katz-Wise, S. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2012). Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 142–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.637247

- Kelley, N. J., Davis, W. E., Dang, J., Liu, L., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Nostalgia confers psychological wellbeing by increasing authenticity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102, 104379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104379

- Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 38, pp. 283–357). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38006-9

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

- Kifer, Y., Heller, D., Perunovic, W. Q. E., & Galinsky, A. D. (2013). The good life of the powerful: The experience of power and authenticity enhances subjective well-being. Psychological Science, 24(3), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612450891

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Larson, D., & Chastain, R. (1990). Self-concealment: Conceptualization, measurement, and health implications. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 9(4), 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.4.439

- Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L., Sedikides, C., & Power, K. (2013). I feel good, therefore I am real: Testing the causal influence of mood on state authenticity. Cognition & Emotion, 27(7), 1202–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.778818

- Levitt, H. M., Horne, S. G., Herbitter, C., Ippolito, M., Reeves, T., Baggett, L. R., Maxwell, D., Dunnavant, B., & Geiss, M. (2016). Resilience in the face of sexual minority stress: “Choices” between authenticity and self-determination. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 28(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2016.1126212

- Li, Y., & Samp, J. A. (2019). Internalized homophobia, language use, and relationship quality in same-sex romantic relationships. Communication Reports, 32(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2018.1545859

- Lingiardi, V., Baiocco, R., & Nardelli, N. (2012). Measure of internalized sexual stigma for lesbians and gay men: A new scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(8), 1191–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.712850

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Mak, W. W. S., & Cheung, R. Y. M. (2010). Self-stigma among concealable minorities in Hong Kong: Conceptualization and unified measurement. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(2), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01030.x

- Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23

- Meidlinger, P. C., & Hope, D. A. (2014). Differentiating disclosure and concealment in measurement of outness for sexual minorities: The Nebraska outness scale. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000080

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Mickelson, K. D. (2001). Perceived stigma, social support, and depression. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 1046–1056. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278011

- Mitchell, R. C., Davis, K. S., & Galupo, M. P. (2015). Comparing perceived experiences of prejudice among self-identified plurisexual individuals. Psychology and Sexuality, 6(3), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.940372

- Moffa, G., Catone, G., Kuipers, J., Kuipers, E., Freeman, D., Marwaha, S., Lennox, B. R., Broome, M. R., & Bebbington, P. (2017). Using directed acyclic graphs in epidemiological research in psychosis: An analysis of the role of bullying in psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(6), 1273–1279. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx013

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group*. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Mohr, J., & Fassinger, R. (2000). Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33(2), 66–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2000.12068999

- Morandini, J., Strudwick, J., Menzies, R., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2022). Differences between Australian bisexual and pansexual women: An assessment of minority stressors and psychological outcomes. Psychology and Sexuality, 14(1), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2022.2100717

- Nadal, K. L. (2019). Measuring LGBTQ microaggressions: The sexual orientation microaggressions scale (SOMS) and the gender identity microaggressions scale (GIMS). Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1404–1414. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1542206

- Osmetti, L. A., & Allen, K. R. (2023). Predictors of psychological well-being in transgender and gender diverse Australians: Outness, authenticity, and harassment. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00914-z

- Paul, R., Smith, N. G., Mohr, J. J., & Ross, L. E. (2014). Measuring dimensions of bisexual identity: Initial development of the bisexual identity inventory. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000069

- Petrocchi, N., Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Carone, N., Laghi, F., & Baiocco, R. (2020). I embrace my LGB identity: Self-reassurance, social safeness, and the distinctive relevance of authenticity to well-being in Italian lesbians, gay men, and bisexual people. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-018-0373-6

- Pinel, E. C. (1999). Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 76(1), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.114

- Puckett, J. A., Newcomb, M. E., Ryan, D. T., Swann, G., Garofalo, R., & Mustanski, B. (2017). Internalized homophobia and perceived stigma: A validation study of stigma measures in a sample of young men who have sex with men. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 14(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-016-0258-5

- Quinn, D. M., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2009). Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 97(4), 634–651. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015815

- Rand, J. J., & Paceley, M. S. (2022). Exploring the lived experiences of rural LGBTQ + youth: Navigating identity and authenticity within school and community contexts. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 34(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2021.1911902

- Riazi, A., Bradley, C., Barendse, S., & Ishii, H. (2006). Development of the well-being questionnaire short-form in Japanese: The W-BQ12. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-40

- Riggle, E. D. B., Mohr, J. J., Rostosky, S. S., Fingerhut, A. W., & Balsam, K. F. (2014). A multifactor lesbian, gay, and bisexual positive identity measure (LGB-PIM). Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000057

- Riggle, E. D. B., Rostosky, S. S., Black, W. W., & Rosenkrantz, D. E. (2017). Outness, concealment, and authenticity: Associations with LGB individuals’ psychological distress and well-being. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000202

- Roseneil, S. (2002). The heterosexual/homosexual binary (D. Richardson & S. Seidman, Eds.). Sage. http://www.uk.sagepub.com/refbooks/Book209825#tabview=title

- Rostosky, S. S., Cardom, R., Cardom, R. D., Hammer, J. H., Hammer, J. H., & Riggle, E. D. B. (2018). LGB positive identity and psychological well-being. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(4), 482–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000298

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Salvati, M., Pistella, J., & Baiocco, R. (2018). Gender roles and internalized sexual stigma in gay and lesbian persons: A quadratic relation. International Journal of Sexual Health, 30(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2017.1404542

- Schmader, T., & Sedikides, C. (2018). State authenticity as fit to environment: The implications of social identity for fit, authenticity, and self-segregation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(3), 228–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317734080

- Sedikides, C., Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L., & Thomaes, S. (2019). Sketching the contours of state authenticity. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000156

- Sedikides, C., & Schlegel, R. J. (2024). Distilling the concept of authenticity. Nature Reviews Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00323-y

- Sedikides, C., Slabu, L., Lenton, A., & Thomaes, S. (2017). State authenticity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 521–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417713296

- Smallenbroek, O., Zelenski, J. M., & Whelan, D. C. (2017). Authenticity as a eudaimonic construct: The relationships among authenticity, values, and valence. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1187198

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Statistics Canada. (2021). A statistical portrait of Canada’s diverse LGBTQ2+ communities. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2021062-eng.htm

- Stonewall. (2018). LGBT health in Britain. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/lgbt-britain-health

- Sutton, A. (2020). Living the good life: A meta-analysis of authenticity, well-being and engagement. Personality & Individual Differences, 153, 109645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109645

- Szymanski, D. M. (2006). Does internalized heterosexism moderate the link between heterosexist events and lesbians’ psychological distress? Sex Roles, 54(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9340-4

- Tebbe, E. A., Bell, H. L., Cassidy, K., Lindner, S., Wilson, E., & Budge, S. (2022). “It’s loving yourself for you”: Happiness in trans and nonbinary adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000613

- Thomaes, S., Sedikides, C., Van den Bos, N., Hutteman, R., & Reijntjes, A. (2017). Happy to be “me?” authenticity, psychological need satisfaction, and subjective well‐being in adolescence. Child Development, 88(4), 1045–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12867

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, D., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- van den Bosch, R., & Taris, T. W. (2014). Authenticity at work: Development and validation of an individual authenticity measure at work. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9413-3

- Vanmattson, S. B. (2023). Relations between binegativity, proximal stressors, and mental health outcomes: The moderating role of authenticity. University of Missouri - Kansas City. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2718624093?parentSessionId=%2BdER9TDK6u8zazRrBvXZAStbgv9V5iQ5uhcSFtATW0s%3D&accountid=26503&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses

- Venaglia, R. B., & Lemay, E. P., Jr. (2017). Hedonic benefits of close and distant interaction partners: The mediating roles of social approval and authenticity. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(9), 1255–1267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217711917

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Williams, K. G. (2023). Becoming an authentic self: A grounded theory of growth-fostering friendships between gay men [ Ph.D., Saybrook University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2808514620/abstract/7B743B260744E2APQ/1

- Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the Authenticity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.385

- Yost, M. R., & Thomas, G. D. (2012). Gender and binegativity: Men’s and women’s attitudes toward male and female bisexuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(3), 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9767-8