ABSTRACT

The study aimed to describe the preparedness of active members of the Philippine Neurological Association (PNA) in providing medical care to LGBTQ+ patients. We electronically sent out a 21-item self-administered online survey adapted from the 2019 American Academy of Neurology LGBTQ+ Survey Task Force to 511 active members of PNA that included questions about demographic information, knowledge, attitude, and clinical practices. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze variables. Text responses were transcribed and summarized. Seventy-nine (15.5%) of 511 PNA members participated. Most participants were aware of local (53%) and national (56%) barriers that preclude patients in the LGBTQ+ sector from accessing quality health care. The majority (90%) of participants agreed that LGBTQ+ patients experience disproportionate levels of physical and psychological problems. Forty-two percent (42%) of respondents believed that sexual and gender issues have no bearing on neurological management, although a majority (53%) reported individualizing their management considering these issues. The majority were cognizant of the challenges that LGBTQ+ patients face in the health care system. However, awareness has not translated into modifications in neurological management. The openness of the participants to educational opportunities concerning health care related to LGBTQ+ can be leveraged to address this gap.

KEYWORDS:

It is estimated that 9% of adults identify as part of the LGBT+ community (Ipsos, Citation2023). Coupled with the increasing number of people identifying as LGBTQ+, there is a steadily increasing acceptance of homosexuality as a function of geography, economic development, political, and religious attitudes, as reported in a recent study (Pew Research Center, Citation2020). However, health disparities continue to prevail among patients belonging the sexual and gender minorities, including a two-fold increase in the all-time mortality rate and significantly lower scores on health-related quality of life measures compared with the heterosexual patients (Cochran et al., Citation2016; Marti-Pastor et al., Citation2018; Nowaskie et al., Citation2018).

A similar situation is experienced by the LGBTQ+ community in the Philippines. Despite great improvements in gender equality—with respect to gender parity, the Philippines ranks second in East Asia and the Pacific and 16th globally (World Economic Forum, Citation2023)—disparities widely remain in terms of mental health, access to mental health services (UNDP, USAID, Citation2014), legislation, and politics (Abesamis & Alibudbud, Citation2024; UNDP, USAID, Citation2014). Accessibility remains a problem due to underinvestment, shortage of capable health care professionals (HCP), and struggling community-based mental health establishments (Lally et al., Citation2019). Moreover, LGBTQ+ Filipinos still face discrimination from outside and even within the LGBTQ+ community. This is seen across various settings including in the workplace, where they are refused employment or promotion unless they conform to their birth-assigned sex; in schools, where they experience bullying; and even by own family members to the point of being disowned (UNDP, USAID, Citation2014). This discriminatory attitude may have stemmed from the stigmatization of flexible gender identities present in precolonial Philippines (Abesamis, Citation2022) and the predominant influence of the Catholic Church in ensuring that familial and social values are aligned with traditional male or female gender roles (Amaroto, Citation2016; Yarcia et al., Citation2019). These barriers lead to self-medication and taking alternative routes to health care instead of availing the elusive formal health care services in the country (Abesamis, Citation2022). Various recommendations have been made by various groups and individuals in both the public and private sectors to alleviate these disparities and barriers. These include communicating with the Department of Health to demand inclusivity in its programs and services (UNDP, USAID, Citation2014,) striving to bridge the gap in the different existing rights discourses, promoting local antidiscrimination ordinances and social programs, enhancing the capabilities of local policy implementers (e.g. police and barangay personnel), and tapping Filipino academicians and intellectuals to advocate for the LGBTQ+ community in public fora and policy discourses (Abesamis & Alibudbud, Citation2024).

In spite of an increasing recognition of how the lack of capable HCP can contribute to these disparities, HCP still do not receive adequate training in LGBTQ+ health (Obedin-Maliver et al., Citation2011). To gain a better understanding of the situation, a handful of local studies have assessed the knowledge and attitudes of Filipino HCP toward LGBTQ+ patients (Alibudbud, Citation2024; Oducado, Citation2023; Rubio & Echem, Citation2022). However, these studies were conducted on a small scale (i.e., respondents were from only one locale or one institution) and might not reflect sociocultural diversity across the country. Moreover, LGBTQ+ health issues relevant to medical specialists are also becoming more apparent such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disorders, rates of smoking and other substance use disorders, and risks associated with hormonal medications. Thus, it is deemed important for the benefit of both the patient and the HCP to be capable in handling LGBTQ+ health issues (Rosendale & Andrew Josephson, Citation2015). One landmark study in 2019 assessed the attitudes and knowledge of members of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) in caring for LGBTQ+ patients. Even though the study reported that most members recognized barriers to care experienced by patients, only a minority considered these to be relevant to the provision of high-quality neurologic care (Rosendale et al., Citation2019). Studies dealing with LGBTQ+ health issues in medical education, residency, fellowship, and subspecialty practice are scarce and almost come from Western countries (Hayes et al., Citation2015; Streed et al., Citation2019; Zelin et al., Citation2019). Therefore, there is a need to conduct studies in the Asian population of both patients and health care providers to assess whether any cultural differences exist.

In the current study, we aimed to determine the preparedness of Filipino neurologists in terms of their knowledge, attitudes, confidence, and sensitivity in treating patients of the LGBTQ+ community. The findings can serve as an impetus for further in-depth studies on LGBTQ+ patients and can be used as a basis for policy-making and changes in the current practice of neurology in the Philippines with regard to this vulnerable population. Specific objectives include the following: (a) to describe the demographic profile of participating Filipino neurologists and to estimate the proportion of neurologists who identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community; (b) to determine the awareness of local and national barriers that inhibit LGBTQ+ patients from using available health services in the Philippines; and (c) to determine the knowledge of Filipino neurologists regarding physical and mental health issues and the health risk factors of LGBTQ+ patients.

Methods

Study participants

An online survey was sent out electronically for self-administration to 511 active members of the PNA.

Informed consent was electronically obtained from the PNA members upon their voluntary participation.

Study design and procedure

We employed a cross-sectional research design to collect data through a survey questionnaire (Supplemental Appendix SA1) adapted from a prior study (Rosendale et al., Citation2019), with permission obtained from the corresponding author. Our study was approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Review Ethics Board (UPMREB-026-21) and endorsed by the Philippine Neurological Association (PNA) prior to data collection. The PNA is the country’s duly recognized national organization of board-certified diplomates in Adult and Pediatric Neurology (n = 511). Our study adhered to the ethical guidelines set by the Declaration of Helsinki 2008, World Health Organization (WHO) Operational Guidelines, and the 2017 National Ethics Guidelines for Research (Philippines, Citationn.d.). The minimum sample size was computed to be 416, given a level of significance set at 0.05 with 80% power and a 20% attrition rate.

The online survey ran for 3 months on Google Form consisting of three parts. Part 1 asked for participants’ demographic data: (a) age group of patients (pediatric or adult); (b) neurology subspecialization; (c) age; (d) years of practice; (e) area of practice in the Philippines; and (f) type of hospital affiliation (public, private, or both). Part 2 contained 21 items involving knowledge, attitude, and clinical practices concerning patients of the LGBTQ+ community. The questions asked about whether the provider was comfortable in explaining the difference between sexual orientation and gender identity and completing sexual history; was aware of the more prevalent risk factors for stroke and the disproportionate risk for physical and mental health problems; felt competent or prepared in examining and managing LGBTQ+ patients; had received adequate clinical training or experience working with LGBTQ+; agreed that it is important to collect information about sexual orientation and gender identity and has a bearing on management; and would tailor their neurologic care based on their sexual orientation or gender identity. The responses were answerable using a 5-point Likert scale: strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1. Lastly, Part 3 consisted of multiple-choice questions about sex, gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation classification and issues of the participants. Some questions requested to provide details using a text-entry response, including a question about whether the participant had gained knowledge in taking the survey and whether there was anything else the participant would like to share with the PNA regarding LGBTQ+ health.

Analysis

We performed a descriptive statistical analysis on the data as follows: (a) chi-squared test for association between categorical variables; (b) rank sum test for continuous variables; and (c) Pearson correlation for association between responses. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Text-entry responses and comments were transcribed, edited for spelling and grammar, and summarized.

Results

Respondent demographics

A responder rate of 15.5% (79/511) was obtained. The majority handled adult patients (62% [49/79]), the second largest group handles a mix of adult and pediatric patients (22.8% [18/79]), and a relatively significant proportion saw exclusively pediatric patients (15.2% [12/79]). The top neurological diseases seen in respondent’s practice were (a) seizures and/or epilepsy (92.4% [73/79]), (b) headache (89.9% [71/79]), and (c) cerebrovascular disease (84.8%]67/79]). Areas of practice were mostly urban areas (59.5% [47/79]), with only 13.9% (11/79) concentrated in rural areas. Some respondents had a combined urban and rural area of practice (26.6% [21/79]). Private-based practice and a mixture of public and private settings were comparable at 50.6% (40/79) and 44.3% (35/79), respectively, with only a small percentage solely practicing in government-run hospitals (5.1% [4/79]). In terms of duration of years of practice, most respondents had either less than 5 years of experience (24.1% [18/79]) or 10–20 years of clinical experience (40.5% [32/79])

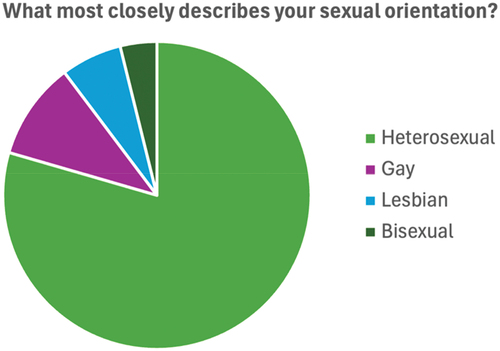

There were more female (73.1% [57/78]) than male (26.9% [21/78]) participants and no respondents reported having intersex patients (n = 78/79). As can be seen in , the majority of respondents identified as heterosexual (79.5% [62/78]), while 16 respondents identified as a sexual minority: (a) gay (10.3% [8/78]), (b) lesbian (6.4% [5/78]), and (c) bisexual (3.8[3/78]). However, with regard to whether they were out or open about their sexual orientation at work, 27 responses were collected: 44% (12/27) said yes, 25.9% (7/27) said they were out to a select group of people, 25.9% (7/27) declined to answer, and 1 (3.7%) said no. Top reasons given for not being at work were: (a) nobody’s business (66.7% [8/12]), (b) fear of discrimination (16.7% [2/12]), (c) concern over future career options (16.7% [2/12]), and (d) religious beliefs (16.7% [2/12]).

In terms of gender identity, 77 responded, with the majority identifying as a woman and a man. One participant identified as a transgender man. Three respondents identified as cisgender woman or cisgender man. One answered “other,” stating, “I don’t see the difference between a woman and cisgender woman but basically, my gender identity is either one—born female, feels like a woman.” When asked if those who identified as transgender, genderqueer, nonbinary or other were out about their gender identity at work, 17 responded with either yes 58.8% (10/17) or declined to respond 41.2% (7/17). Only 5 answered the question about reasons for not being out about gender identity at work. They responded with nobody’s business (40% [2/5]), and not applicable (60% [3/5]).

Awareness of deterrents to health care

Most of the participants agree to being aware of the local and national barriers facing LGBTQ+ patients to availing of health care services: (a) 56.4% (44/78) and 53.8% (42/78) for local and national barriers inhibiting transgender people, respectively, and (b) 50.6% (40/79) and 47.4% (37/78) for local and national barriers inhibiting LGBQ people, respectively. The majority of the respondents said they agreed that gender identity (69.2% [54/78]) and sexual orientation (70.9% [56/79]) are social determinants of health. More than half of the participants said they agreed that transgender (89.9% [71/79]) and LGBQ (75.9% [60/79]) individuals experience disproportionate levels of physical and mental health problems compared to cisgender individuals; 70.5% [55/78]) also agreed that tobacco and substance abuse are prevalent in the LGBTQ+ community.

Trends in practice

Around half of the participants (59.0% [46/78]) were comfortable in explaining the difference between sexual orientation and gender identity, while 26.9% (21/78) were neutral about it. More than half (87.1% [68/78]) considered it important for clerical and ancillary staff to be trained in terminology and concepts related to gender identify and sexual orientation. Although roughly half (65.4% [51/78]) also reported believing that it is important to collect information about sexual orientation and gender identity in electronic medical records, a quarter of the respondents (25.6% [20/78]) said they were neutral on this question.

Most of the respondents (74.3% [58/78]) reported being as comfortable conducting a physical examination on LGBTQ+ patients as on straight patients, while (19.2% [15/78]) reported being neutral. The majority (74.3% [58/78]) said they felt competent to examine and assess transgender patients in the therapeutic setting and were also as competent in seeing transgender patients as cisgender patients (77.9% [60/77]). In terms of obtaining sexual history, participants said they were comfortable asking for such information from LGBQ (71.8% [56/78]) and transgender patients (68.8% [53/77]), while 17.9% (14/78) and 20.5% (16/78) said they were neutral, respectively. Half reported being prepared to talk to LGBQ (54.8% [45/77]) and transgender (55.1% [43/78]) patients about issues related to their sexual orientation and gender identity, while 19.2% said they were not prepared. However, only less than a quarter of respondents answered that they had received adequate clinical training and supervision to work with transgender patients (21.8% [17/78]). Only comfort in doing a physical exam (r = 0.98, p = 0.0012) and competence in assessing a patient in the therapeutic setting (r = 0.97, p = 0.0072) were significantly correlated with responses regarding sexual and gender minority patients.

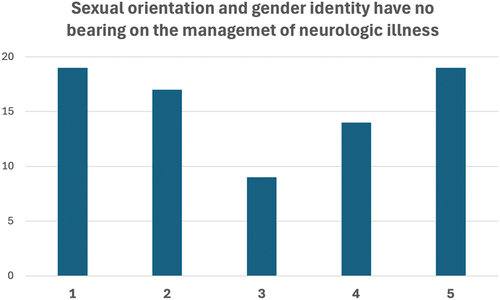

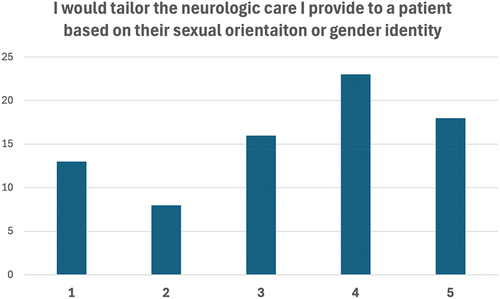

Less than half (42.3% [33/78]) of respondents agreed that sexual orientation and gender identity have no bearing on the management of neurologic illness, while a similar percentage (46.1% [36/78]) said they believed that these factors affected the management of sexual and gender minorities (see ). Conversely, more than half (52.6% [41/78]) said they would tailor the neurologic care they provide based on the patient’s sexual orientation and gender identity, while a minority said they would not tailor fit the provision of care (26.9% [21/78]) (see ). There was no noted significant correlation between responses to “sexual orientation and gender identity have no bearing on the management of neurological diseases” and questions on the ability to conduct a physical examination, being comfortable in obtaining sexual history, asking about issues related to sexual preference and gender identity, and feeling competent in the therapeutic setting.

Figure 2. Bar graph representation of 5-point Likert item responses to the statement: “Sexual orientation and gender identify have no bearing on management of neurologic diseases.” Numbers on the x-axis represent strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1; numbers on the y-axis represent number of responses.

Figure 3. Bar graph representation of 5-point Likert item responses to the statement: “I would tailor the neurologic care I provide to a patient based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.” Numbers on the x-axis represent strongly agree= 5,agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1; numbers on the y-axis represent number of responses.

Participant understanding and learning

The majority of respondents (55.3% [42/76]) agreed that they gained knowledge by taking the survey, while 44.7% (34/76) disagreed. In particular, most participants learned definitions of terms—the need to be aware of such terms, the confusion arising from using them, and the importance of using appropriate terms. Some respondents also mentioned their realization of the need to have more training on handling LGBTQ+ patients. Almost all (80.5% [62/77]) were interested in receiving further training on providing culturally appropriate care to the LGBTQ+ community. The majority said they preferred the following educational formats: webinar and online modules as well as case presentation, course didactics, and “Ask the Experts” at the PNA annual meeting. Presented in were additional comments the participants would like to share with the PNA regarding LGBTQ+ health.

Table 1. Respondent comments regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer plus health when asked the question: “Is there anything else you would like to share with the PNA regarding LGBTQ+1 health?”

Discussion

The existing health-related research geared primarily for the improvement of health care issues of LGBTQ+ patients are modest, especially in the Asia-Pacific region. To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first studies to look into the preparedness of physicians to tackle issues in the management of patients who identify as LGBTQ+ in the Philippines on a broader national level and the first to explore among neurologists. Key findings of this study include that most clinicians are (a) aware of the barriers and disparities that deter LGBTQ+ patients from availing of health care services, (b) were comfortable with conducting history and physical examination of LGBTQ+ patients, (c) felt competent in providing care for LGTBQ+ patients, (d) agreed that sexual preference and gender preference are determinants of health, and (e) agreed that there is room for improvement in terms of training in providing care for LGBTQ+ patients. However, amidst the awareness and acknowledgment that LGBTQ+ patients have special health care needs that must be addressed, most respondents said they believed that sexual preference and gender expression had no bearing on the management of neurological diseases.

The results of this online survey of Filipino neurologists concerning their attitudes about and knowledge of the care of LGBTQ+ patients highlight certain significant perspectives. First, the overall low responder rate can be interpreted as an indirect gauge of how open the target participants are toward the topic. Starting a conversation on sexuality and gender and their intersection with the provision of quality health care may be a barrier for Filipino physicians having a background of possible sociocultural and religious beliefs that are deeply rooted in precolonial Philippine society and that stigmatize flexible gender identities (Abesamis, Citation2022). Rigid traditional heteronormative roles are upheld by the dominant religious group in the country (Amaroto, Citation2016; Yarcia et al., Citation2019). Moreover, this lack of openness of some physicians in discussing the topics of gender identity and orientation with the patient may be due to the preconceived notion that patients will not disclose this kind of information. Still other HCPs deem that this discussion is not needed unless it is related to medical treatment, as they value treating all patients equally (Haider et al., Citation2017). Consequently, the low responder rate in questions involving personal sexual orientation and gender identity is an area of interest, especially since the reasons for clinician members of LGBTQ+ to not be out is that they believe such information is not necessary to divulge and that it may be a concern for future career options. Although it was reiterated that the survey was anonymous, apprehension toward answering the questions may still be a confounding factor. In relation to the openness to discuss sex and gender, ensuring confidentiality, and availability of a private space, inquiries documented the same as other demographic questions. Respondents identified nonverbal self-report of responses as a preferred approach to facilitating discussion and collecting information (Haider et al., Citation2017), which neurologists and other HCPs can adapt in their practice.

Second, responder demographics may offer insight as to possible opportunities to address certain knowledge gaps in LGBTQ+ health. Most of the respondents were neurologists with 10–20 years of clinical experience, which may be correlated with having more encounters and experience with LGBTQ+ patients. The reason for the weaker response from more junior and senior neurologists may be further explored. Studies have shown that different stages of medical training may have particular issues regarding LGBTQ+ concerns. Medical students agree that there is a lack of LGBTQ+ care in their curriculum and inclusion of such topics will help in their decisions toward residency and confidence in tackling issues of LGBTQ+ health (Roth et al., Citation2020; Sitkin & Pachankis, Citation2016; Wahlen et al., Citation2020). Residents have generally lower levels of comfort in conducting sexual history and some physical examination maneuvers on LGBTQ+ patients and agree on the positive effects of inclusion of LGBTQ+ health training in medical programs (Hayes et al., Citation2015; Streed et al., Citation2019; Ufomata et al., Citation2018). Active health care providers, specifically primary care providers (PCP), oncologists, dermatologists, and obstetricians have published data that reflect findings similar to ours that most are confident in dealing with LGBTQ+ patients in terms of assessment and treatment but also agree that more training geared toward sexual and gender minority medicine is needed in their fields (Aleshire et al., Citation2018; Boos et al., Citation2019; Knight et al., Citation2014; Sutter et al., Citation2020; Tamargo et al., Citation2017).

Relatedly, the discrepancy in perceived comfort and competence of physicians and the actual knowledge base regarding LGBTQ+ issues and health care is reiterated in our study. This sentiment is echoed in other studies assessing the attitudes and knowledge of physicians toward LGBTQ+ patients (Rosendale et al., Citation2019; Rubio & Echem, Citation2022). In our survey, most Filipino neurologists agree that sexual orientation and gender identity are important information to elicit from patients since sexual orientation and gender identity can be determinants of health; however, the majority did not agree that such information has a bearing on neurological management despite the fact that most members said they would tailor management on a case-to-case basis. This may reflect a possible intrapersonal difference in understanding “no bearing on neurological management,” whether, for example, a patient is heterosexual or homosexual (with the intent to see patients as equals no matter the sexual orientation) vis-à-vis the possible nuances in conducting physical exams, LGBTQ+-specific sexual history taking, destabilizing rapport, and treatment considerations. This may be an unintentional source of increasing the disparity in neurologic care for LGBTQ+ patients. Several risk factors that are more prevalent in the LGBTQ+ community make LGBTQ+ patients more susceptible to certain neurologic diseases—namely higher rates of smoking, drug abuse, and obesity that increase risk for cerebrovascular diseases and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as drug toxicities and withdrawal; exogenous hormones for gender reaffirming use for transgender patients making them prone to thromboembolic events and breakthrough seizures for persons with epilepsy; increased incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in men who have sex with men (MSM) in connection to neurologic conditions secondary to their immunocompromised state such as CNS infections, lymphoma, leukoencephalopathy, dementia, and paresthesia; and higher rates of anxiety and depression that further places LGBTQ+ patients at a disadvantage in terms of access to health, increased societal stigma, and higher rates of suicide (Chatterjee et al., Citation2020). Increased rates of substance use among LGBTQ+ are most likely due to the stress (Gonzales et al., Citation2016) that they uniquely experience as someone belonging a stigmatized minority, putting LGBTQ+ patients at additional risk for developing mental health problems, which are another cause of increased rates of substance use (Jabson et al., Citation2014). Other factors may include social norms and spaces that promote normalcy of smoking (Holloway et al., Citation2012) and targeted marketing to LGBTQ+ community (Balsam et al., Citation2012). There may be a benefit to shifting the paradigm of viewing sexual and gender issues as mostly a sociocultural dilemma to a more holistic biopsychosocial framework wherein a patient’s disease is perceived through a lens of a conglomerate effect of their personal and sociopolitical background.

Lastly, though the turnout was low, those who participated agreed on a need for further training on LGBTQ+ health care, which is echoed by a recent study among HCPs in the one of the provinces in the Philippines (Rubio & Echem, Citation2022). The willingness to learn and even include the topic at future annual conventions is a validation of the likelihood of pursuing achievable programs and activities to address this possible knowledge gap in the practice of neurology in the Philippines. Even in the time of the COVID pandemic, topics like safe sex behavioral practice in conjunction with additional precautions against COVID, continuing hormonal therapy with proper monitored self-administration, and delaying gender-affirming surgeries are overlooked and may be addressed with a wider audience due to the propensity of the webinar/online format of information dissemination (Chatterjee et al., Citation2020). Larger evidence-based studies are needed to look into the possible practice-changing effects of addressing treatment gaps in LGBTQ+ health care.

Limitations

Our study has limitations that can be addressed in future investigations. First is the nongeneralizable nature of the study due to the low response rate and skewed responder bias toward adult neurologists who mostly practice in an urban private-based setting. A comparison of the demographics (e.g., age, sex, gender identity, years of practice, place of practice, religion) of the respondents and nonrespondents can be analyzed to offer insight regarding the representativeness of the sample. Second, volunteer bias is also a concern—that is, those who responded to the survey are those who are more open and more comfortable discussing LGBTQ+ health and thus may have responded more positively. Measures to ensure wider coverage and increased response rates should be made in order to minimize volunteer bias, which could include presurvey communication, longer duration of data collection and sending gentle reminders, and more options or avenues to conduct data collection that will ensure anonymity of the responder. Third involves the possible confusion in terms used, despite the provision of definitions at the start of the survey. Fourth is the lack of validation of the questionnaire used and the question of applicability in non-Western countries. Lastly, the weak investigative nature of the descriptive and quantitative analysis of the data needs to be addressed in additional prospective studies.

Conclusion

This is the first study to look into the attitudes and knowledge of non-Western neurologists, particularly members of the Philippine Neurologists Association, toward LGBTQ+ patients. We achieved our specific objectives in identifying the demographic profile, awareness, and knowledge of Filipino neurologists in terms of assessing preparedness in caring for LGBTQ+ patients. Most participants were female adult neurologists involved in urban private practice and only 20% identified as part of the LGBTQ+ community. The majority reported having adequate awareness of the unique set of barriers to the ability of LGBTQ+ patients to access quality health care and feeling comfortable and competent in handling their cases. However, a discrepancy in terms of reconciling the necessity to personalize neurologic care to cater to LGBTQ+ patients is still apparent. Although the turnout of participants was low, this study showed that among the participating Filipino neurologists, there was still much to improve in terms of LGBTQ+ health training. This discrepancy in awareness and willingness to provide quality care in the context of inadequate knowledge and training in LGBTQ+ health may be addressed by the openness of the members to undergo competency education concerning this topic in future online-based learning opportunities.

Authorship contribution statement

JRCB: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, interpretation of data, writing of original draft and review, and editing. MWLM: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, interpretation of data, writing of original draft and review, and editing. AIE: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, interpretation of data, writing of original draft and review, and editing. CFDL: Conceptualization, formal analysis, interpretation of data, writing of original draft and review, and editing. PMDP: Conceptualization, formal analysis, interpretation of data, writing of original draft and review, and editing.

Consent for participation and publication

Informed consent was electronically obtained from the participants upon their voluntary participation. A copy of the consent document is available for review from this journal on request.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (156.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Holly Hinson (Oregon Health and Science University) for allowing us to use the survey instrument in her original study, which helped us to design our own survey instrument adapted to our local setting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2024.2378742.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abesamis, L. E. A. (2022). Intersectionality and the invisibility of transgender health in the Philippines. Global Health Research and Policy, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-022-00269-9

- Abesamis, L. E. A., & Alibudbud, R. (2024). From the bathroom to a national discussion of LGBTQ + rights: A case of discrimination in the Philippines. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2023.2251775

- Aleshire, M. E., Ashford, K., Fallin-Bennett, A., & Hatcher, J. (2018). Primary care providers’ attitudes related to LGBTQ people: A narrative literature review. Health Promotion Practice, 20(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839918778835

- Alibudbud, R. (2024). Enhancing nursing education to address LGBTQ+ healthcare needs: Perspectives from the Philippines. SAGE Open Nursing, 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608241251632

- Amaroto, B. (2016). View of structural-systemic-cultural violence against LGBTQs in the Philippines. Retrieved June 12, 2024, from https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/HRPS/article/view/163851/118633

- Balsam, K. F., Beadnell, B., Riggs, K. R. (2012). Understanding sexual orientation health disparities in smoking: A population-based analysis. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01186.x

- Boos, M. D., Yeung, H., & Inwards‐Breland, D. (2019). Dermatologic care of sexual and gender minority/LGBTQIA youth, part I: An update for the dermatologist on providing inclusive care. Pediatric Dermatology, 36(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.13896

- Chatterjee, S., Biswas, P., Guria, R. T. (2020). LGBTQ care at the Time of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(6), 1757–1758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.001

- Cochran, S. D., Björkenstam, C., & Mays, V. M. (2016). Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 Years, 2001–2011. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), 918–920. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303052

- Gonzales, G., Przedworski, J., & Henning-Smith, C. (2016). Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the United States: Results from the national health interview survey. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(9), 1344–1351. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3432

- Haider, A. H., Schneider, E. B., Kodadek, L. M., Adler, R. R., Ranjit, A., Torain, M., Shields, R. Y., Snyder, C., Schuur, J. D., Vail, L., German, D., Peterson, S., & Lau, B. D. (2017). Emergency department query for patient-centered approaches to sexual orientation and gender identity the Equality study. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(6), 819–828. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0906

- Hayes, V., Blondeau, W., & Bing-you, R. G. (2015). Assessment of medical student and resident/fellow knowledge, comfort, and training with sexual history taking in LGBTQ patients. Family Medicine, 47(5), 383–387. https://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol47Issue5/Hayes383

- Holloway, I. W., Traube, D. E., Rice, E., Schrager, S. M., Palinkas, L. A., Richardson, J., & Kipke, M. D. (2012). Community and individual factors associated with cigarette smoking among young men who have sex with men. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(2), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00774.x

- Ipsos. (2023). A 30-country ipsos global advisor survey LGBT+ PRIDE 2023.

- Jabson, J. M., Farmer, G. W., & Bowen, D. J. (2014). Stress mediates the relationship between sexual orientation and behavioral risk disparities. BMC Public Health, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-401

- Knight, R. E., Shoveller, J. A., Carson, A. M., & Contreras-Whitney, J. G. (2014). Examining clinicians’ experiences providing sexual health services for LGBTQ youth: Considering social and structural determinants of health in clinical practice. Health Education Research, 29(4), 662–670. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt116

- Lally, J., Tully, J., & Samaniego, R. (2019). Mental health services in the Philippines. British Journal of Psychiatry International, 16(3), 62–64. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2018.34

- Marti-Pastor, M., Perez, G., German, D., Pont, A., Garin, O., Alonso, J., Gotsens, M., & Ferrer, M. (2018). Health-related quality of life inequalities by sexual orientation: Results from the barcelona health interview survey. PLOS ONE, 13(1), e0191334. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191334

- Nowaskie, D. Z., Sowinski, J. S., & Nowaskie, D. Z. (2018). Primary care providers’ attitudes, practices, and knowledge in treating LGBTQ communities. Journal of Homosexuality, 1927–1947. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1519304

- Obedin-Maliver, J., Goldsmith, E. S., Stewart, L., White, W., Tran, E., Brenman, S., Wells, M., Fetterman, D. M., Garcia, G., & Lunn, M. R. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender–related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA, 306(9). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1255

- Oducado, R. M. F. (2023). Knowledge and attitude towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender healthcare concerns: A cross-sectional survey among undergraduate nursing students in a Philippine state university. Belitung Nursing Journal, 9(5), 498–504. https://doi.org/10.33546/bnj.2887

- Pew Research Center. (2020). The global divide on homosexuality persists. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/06/PG_2020.06.25_Global-Views-Homosexuality_FINAL.pdf

- Philippines. (n.d.). Philippine health research ethics board. Ad hoc committee for updating the national ethical guidelines, philippine council for health research and development. National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-Related Research, 2017.

- Rosendale, N., & Andrew Josephson, S. (2015). The importance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health in neurology. JAMA Neurology, 72(8), 855–856. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0226

- Rosendale, N., Ostendorf, T., Evans, D. A., Weathers, A., Sico, J. J., Randall, J., & Hinson, H. E. (2019). American academy of neurology members’ preparedness to treat sexual and gender minorities. Neurology, 93(4), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007829

- Roth, L. T., Friedman, S., Gordon, R., & Catallozzi, M. (2020). Rainbows and “ready for residency”: Integrating LGBTQ health into medical education. MedEdPORTAL, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11013

- Rubio, R. R. M., & Echem, R. (2022). Correlates of attitudes of Filipino healthcare providers toward the LGBT patients. Internation Journal of Nursing and Health Sciences, 5(6), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.35654/ijnhs.v5i6.644

- Sitkin, N. A., & Pachankis, J. E. (2016). Specialty choice among sexual and gender minorities in medicine: The role of specialty prestige. Perceived, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0058

- Streed, C. G. J., Hedian, H. F., Bertram, A., & Sisson, S. D. (2019). Assessment of internal medicine resident preparedness to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(6), 893–898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04855-5

- Sutter, M. E., Bowman‐Curci, M. L., Duarte Arevalo, L. F., Sutton, S. K., Quinn, G. P., & Schabath, M. B. (2020). A survey of oncology advanced practice providers ’ knowledge and attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities with cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15–16), 2953–2966. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15302

- Tamargo, C. L., Quinn, G. P., & Schabath, M. B. (2017). Cancer and the LGBTQ population: Quantitative and qualitative results from an oncology providers ’ survey on knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 6(10), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm6100093

- Ufomata, E., Eckstrand, K. L., Hasley, P., Jeong, K., Rubio, D., & Spagnoletti, C. (2018). Comprehensive internal medicine residency curriculum on primary care of patients who identify as LGBT. LGBT Health, 5(6), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0173

- UNDP, USAID. (2014). Being LGBT in Asia: The Philippines country report. Bangkok.

- Wahlen, R., Bize, R., Wang, J., Merglen, A., & Ambresin, A.-E. (2020). Medical students’ knowledge of and attitudes towards LGBT people and their health care needs: Impact of a lecture on LGBT health zweigenthal VEM. ed. PLOS ONE, 15(7), e0234743. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234743

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Global gender gap report 2023.

- Yarcia, L. E., De Vela, T. C., & Tan, M. L. (2019). Queer identity and gender-related rights in post-colonial Philippines. Australian Journal of Asian Law, 20(1), 265–275. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3488543

- Zelin, N. S., Encandela, J., Van, D. T., Fenick, A. M., Qin, L., & Talwalkar, J. S. (2019). Pediatric residents’ beliefs and behaviors about health care for sexual and gender minority youth. Clinical Pediatrics, 58(13), 1415–1422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819851264