?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

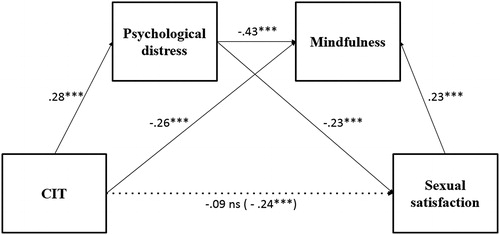

Mindful attention and awareness may promote sexual satisfaction. However, experiencing cumulative childhood interpersonal trauma (CCT; sexual abuse, neglect, etc.) is associated with distress, which might interfere with dispositional mindfulness and lead to lower sexual satisfaction. Although the concept of mindfulness emerged as an interesting variable to understand sexual difficulties, little empirical data are available on this topic. This study tested an integrative mediation model of the relation between CCT, psychological distress, dispositional mindfulness, and sexual satisfaction within a clinical sample of 410 adult patients consulting in sex therapy. Patients completed questionnaires assessing CCT, psychological distress, dispositional mindfulness, and sexual satisfaction. Results showed that the majority of patients reported experiences of childhood interpersonal trauma. Path analyses highlighted three distinct significant paths from CCT to sexual satisfaction. First, dispositional mindfulness mediated the relationship between CCT and sexual satisfaction. Second, psychological distress also mediated the relationship between CCT and sexual satisfaction. Third, the effect of CCT on sexual satisfaction was sequentially mediated through greater levels of psychological distress and lower levels of dispositional mindfulness. The model explained 19% of the variance in sexual satisfaction. Findings suggest that dispositional mindfulness and psychological distress are key processes explaining sexual satisfaction in CCT survivors.

A substantial body of scholarly literature reveals that childhood interpersonal trauma (i.e., sexual abuse, psychological abuse, physical abuse, neglect, exposure to interparental violence, and bullying) and especially cumulative childhood trauma (CCT; the accumulation of childhood interpersonal trauma) are associated with a wide range of negative outcomes. Yet, less is known about its effects on sexual satisfaction and the possible mechanisms explaining the link between CCT and sexual satisfaction. Sexual satisfaction is a crucial component of personal and overall couple well being, often motivating individuals to seek sex therapy (Sánchez-Fuentes, Santos-Iglesias, & Sierra, Citation2014). Therefore, comprehensive models of sexual satisfaction are essential and models aiming to understand sexual satisfaction may benefit from considering CCT.

Childhood interpersonal trauma and sexual satisfaction

Early developmental adversities have been found be related to the shaping of sexual attitudes and behaviors in adulthood (Bigras, Daspe, Godbout, Briere, & Sabourin, Citation2017). CCT may be particularly detrimental to the sexual realm, and even more to sexual satisfaction (Bigras, Godbout, Hébert, & Sabourin, Citation2017), which may be defined as the subjective evaluation of one’s sexuality or, more precisely, a sexual life perceived as positive, satisfying, good, enjoyable or pleasant, and valuable (Lawrence & Byers, Citation1995). Indeed, survivors of CCT may experience negative inner experiences (e.g., psychological distress) and a lack of awareness in the present moment (Briere, Hodges, & Godbout, Citation2010), potentially leading to poorer sexual satisfaction. As such, CCT survivors may be less in tune with their bodily sensations, less receptive to sexual experiences, or may come to perceive sexuality as negative. Moreover, childhood interpersonal trauma is essentially relational (i.e., aversive experiences that occurred within relationships) and may therefore lead to intimacy issues, making it difficult to experience sexual comfort or satisfaction. In fact, sexuality implies a context of vulnerability, which may exacerbate trauma-related negative outcomes (Godbout, Runtz, MacIntosh, & Briere, Citation2013).

Empirical data support these positions, although most studies have examined the effects of childhood sexual abuse on adult sexual outcomes (Bigras, Godbout, & Briere, Citation2015; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., Citation2016) without considering the effects of CCT. For example, childhood sexual abuse was found to be related to lower sexual satisfaction in adulthood, through its impacts on higher fears of abandonment and higher avoidance of intimacy (Vaillancourt-Morel, Godbout, Sabourin, Péloquin, & Wright, Citation2014). Survivors were also found to be more likely to consider their bodies as a source of pain rather than a source of sexual pleasure (Vaillancourt-Morel et al., Citation2014). Yet, recent studies indicate that other forms of childhood victimization, and especially CCT, are also associated with diminished sexual satisfaction (Bigras, Godbout, Hébert, & Sabourin, Citation2017; Bigras et al., Citation2017). This observation is concordant with the trauma literature suggesting that CCT is related to long-lasting deleterious outcomes to a greater extent than the experience of a single form of abuse (Briere et al., Citation2010; Briere & Scott, Citation2014). Moreover, adults consulting for sexual difficulties tend to report particularly high levels of exposure to childhood interpersonal trauma and CCT (Berthelot, Godbout, Hébert, Goulet, & Bergeron, Citation2014; Bigras, Godbout, Hébert, & Sabourin, Citation2017). They also report sexuality as being less satisfying, less valuable, or less pleasant, which might, in part, stem from their endured traumas. Previous studies highlighted that lower affect regulation (i.e., inability to regulate or tolerate one’s negative emotional states), higher sexual anxiety, and symptom complexity partly explained the link between CCT and sexual satisfaction (Bigras et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). Studies also documented a link between childhood interpersonal trauma and psychological distress in adulthood, as well as the potential negative influence of distress on sexual satisfaction (Bigras et al., Citation2017; Sánchez-Fuentes, Santos-Iglesias, & Sierra, Citation2014). Yet, the role of psychological distress remains understudied among adult survivors of CCT consulting for sexual difficulties.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress appears to be a key variable to be taken into account in a model examining the link uniting CCT and sexual satisfaction. First, childhood interpersonal trauma victims are at greater risk of developing psychological distress (Dugal, Bigras, Godbout, & Bélanger, Citation2016; Kalmakis & Chandler, Citation2014). More specifically, several studies have shown that CCT is significantly associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, irritability, and suicidality (Briere, Godbout, & Dias, Citation2015; Cohen, Menon, Shorey, Le, & Temple, Citation2017; Delker, Smith, Rosenthal, Bernstein, & Freyd, Citation2018). Second, psychological distress is considered to be part of the etiology of sexual difficulties and sexual satisfaction (Althof et al., Citation2005; Dèttore, Pucciarelli, & Santarnecchi, Citation2013). Bigras et al. (Citation2017) specifically found higher levels of psychological distress to act as a mediator of the link between CCT and lower sexual satisfaction. Last, psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, irritability, cognitive impairments) may encourage the use of avoidance strategies to escape from suffering or unpleasant psychological states, which may in turn diminish attentiveness and awareness of what is taking place in the present moment (Bolduc, Bigras, Daspe, Hébert, & Godbout, Citation2018; Briere, Citation2015; Godbout, Bigras, & Dion, Citation2016; Masuda & Tully, Citation2012).

Mindfulness

As such, mindfulness is also at the center of the model proposed in this study to examine the link uniting CCT and sexual satisfaction. Mindfulness involves, by definition, a state of attentiveness and awareness of what is taking place in the present moment as it unfolds (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003) and is conceptualized and studied both as “state mindfulness” and “dispositional mindfulness.” State mindfulness reflects a momentary condition typically targeted by mindfulness-based interventions (e.g., mindfulness-based stress reduction; Kabat-Zinn, Citation1990), while dispositional mindfulness refers to an inherent human capacity or trait (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, Citation2007; Kabat-Zinn, Citation1990), which is the focus of this study.

In fact, a lower dispositional mindfulness may be particularly detrimental to sexual functioning. Namely, individuals who are distracted, less present, less aware, or unmindful might report lower sexual satisfaction because (1) they may show less awareness of sexual stimuli or less capacity to identify and experience pleasant states as they unfold, therefore potentially experiencing less sexual satisfaction; and (2) their lack of self-regulation of attention might preclude psychological distance from anxious thoughts and decrease their contact with moment-to-moment experiences, hence tempering arousal reactions toward sexual stimuli (Brotto & Basson, Citation2014; Brotto & Goldmeier, Citation2015).

Empirical data support those assumptions. For example, among a sample of women, cognitive distraction during sexual activity was found to be significantly associated to lower sexual satisfaction (Dove & Wiederman, Citation2000). Previous studies also identified significant links between low sexual desire and activity, sexual dissatisfaction as well as low dispositional mindfulness (Dosch, Rochat, Ghisletta, Favez, & Van der Linden, Citation2016). Déziel, Godbout, and Hébert (Citation2017) found that mindfulness acted as a mediator in the link between increased anxiety and lower sexual desire in a sample of men consulting in sex therapy. A greater disposition to mindfulness has also been related to one’s ability to fully experience the sexual act (Cash & Whittingham, Citation2010; Slonim, Kienhuis, Di Benedetto, & Reece, Citation2015), and research has found mindfulness-based interventions to have a positive effect on sexuality, especially on sexual desire (Brotto, Chivers, Millman, & Albert, Citation2016; Brotto & Basson, Citation2014).

In turn, CCT and psychological distress may lead to lower dispositional mindfulness. More precisely, CCT survivors are likely to show trauma-related responses, including psychological distress, which could impede their disposition to mindfulness (Godbout et al., Citation2016). Therefore, CCT may lead to more psychological distress and, in turn, to lower levels of dispositional mindfulness, which might be related to lower sexual satisfaction. On the one hand, CCT and related symptoms (i.e., flashbacks, intrusive thoughts, painful thoughts) tend to narrow victims’ behavioral repertoire or to increase psychological rigidity or distress, hampering their disposition to be mindful or present (Bolduc et al., Citation2018; Follette & Pistorello, Citation2007) and potentially leading to diminished sexual satisfaction. On the other hand, a substantial body of empirical data linked lower dispositional mindfulness to psychological distress (Deng, Li, & Tang, Citation2014; Mayer, Polak, & Remmerswaal, Citation2019). In fact, the results of a recent systematic review concluded that lower dispositional mindfulness is associated to higher levels of psychological distress (i.e., depression and anxiety) among nonclinical samples (Tomlinson, Yousaf, Vittersø, & Jones, Citation2018). This association could be explained by the negative cognitive patterns underlying psychological distress, such as rumination, which tends to hamper dispositional mindfulness (Desrosiers, Vine, Klemanski, & Nolen-Hoeksema, Citation2013; Frewen, Evans, Maraj, Dozois, & Partridge, Citation2008). To our knowledge, studies have mainly focused on psychological distress in terms of depression or anxiety (Tomlinson et al., Citation2018), but limited research has examined psychological distress as an overall concept including multiple dimensions (i.e., depression, anxiety, irritability, and cognitive disturbances; Ilfeld, Citation1976) or within clinical samples. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no study has tested the role of psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness in the link uniting CCT and sexual satisfaction.

Theoretical framework

The Pain Paradox theory (Briere, Citation2015) is a useful theoretical framework to understand the postulated links between CCT, psychological distress, dispositional mindfulness, and sexual satisfaction. The Pain Paradox refers to the tendency to engage into distress-sustaining behaviors and miss out on important aspects of life that are associated with well-being, while one is in fact trying to avoid painful or upsetting internal states. As such, in accord with the Pain Paradox, the model postulated in the present study suggests that CCT is related to increased psychological distress (i.e., upsetting internal states) in adulthood. In turn, this psychological distress may lead to low dispositional mindfulness, as a mean to escape, withdraw, or suppress awareness from painful inner states (Briere, Citation2002). Yet, such avoidance or low mindfulness, paradoxically used to escape from psychological distress in the short term, may prolong or exacerbate psychological distress and lead to other difficulties or less life satisfaction, potentially including sexual satisfaction. For example, this theory suggests that not only the avoided material cannot be experienced, processed, and psychologically metabolized, but also, by narrowing their attention and deadening their awareness, survivors may miss out on important aspects of life, which might especially be linked with lower satisfaction in the sexual realm. In fact, the numbing of experience or low dispositional mindfulness may diminish survivors’ availability and receptiveness to pleasant stimuli, including sexual stimuli, therefore leading to a sex life perceived as empty, bad, unpleasant, negative, unsatisfying, or worthless. Consequently, psychological distress might be related to lower dispositional mindfulness, which paradoxically maintains or exacerbates distress, and may bring less sexual satisfaction. With that in mind, psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness need to be taken into account in the link between CCT and low sexual satisfaction.

The current study

The main purpose of this study was to examine the mediating roles of psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness in the relationship between CCT and sexual satisfaction in a clinical sample of patients consulting in sex therapy. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that CCT would be associated with lower sexual satisfaction, sequentially through higher psychological distress and lower dispositional mindfulness. More specifically, CCT would be associated with greater levels of psychological distress, which would be associated with lower levels of dispositional mindfulness associated to lower sexual satisfaction. Given the high prevalence rates of child maltreatment among sex therapy patients and because they consult for sexual difficulties, reliance on this population to test the hypothesized model is particularly relevant.

Method

Participants

A total of 410 patients consulting graduate interns in sex therapy for different motives (e.g., sexual dysfunction, sexual dissatisfaction) participated in this study. The sample consisted of 227 women (55.4%), 182 men (44.1%), and 1 person identifying as nonbinary (excluded from gender invariance analysis), with a mean age of 37.80 years (SD = 12.96, ranged from 17 to 77). A majority (87.5%, n = 350) were Canadian citizens, with French as their primary language (86.7%, n = 351). The majority of participants were either students (18.2%, n = 63) or employed (59.7%, n = 207), with a personal annual income below CAN$39,999 (68.3%, n = 268) and college level education (59.8%, n = 245). Regarding their marital status, 38% (n = 156) were single, 27.8% (n = 114) were in a common-law relationship (i.e., living together), 16.8% (n = 69) were in a relationship with a regular partner, and 15.9% were married (n = 65). Concerning sexual orientation, the majority of participants (83.6%, n = 341) reported being heterosexual.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through their interns in clinical sexology in several clinical settings offering sex therapy (i.e., university clinic, hospital/medical settings, community centers, and private practices) in a large metropolitan city from 2015 to 2018, during their first sex therapy sessions (i.e. ,evaluation phase, before treatment). The university’s ethics committee approved the current study. Sex therapy interns explained the study and interested patients were invited to sign the consent form before completing self-report questionnaires online or in paper format. An alphanumeric code was randomly assigned to each participant in order to ensure anonymity.

Measures

Childhood cumulative trauma

CCT was assessed using a French version of the Childhood Cumulative Trauma Questionnaire (CCTQ; Godbout, Bigras, & Sabourin, Citation2017), a self-report 24-item questionnaire assessing eight types of childhood interpersonal trauma experienced before 18 (i.e., physical, psychological, and sexual abuse, physical and psychological neglect, witnessing physical and psychological interparental violence, and bullying). More precisely, childhood sexual abuse was measured with a gate question examining if the individual had experienced any unwanted sexual act before 18 or any sexual act with an adult at least 5 years older or in a position of authority before 16 years of age. This question was followed by an inquiry of the type of sexual acts that were perpetrated (e.g., with or without contact, penetration) as well as the relationship with the perpetrator (e.g., parental figure, family member, stranger). For the other forms of childhood interpersonal trauma, participants indicated the frequency with which they experienced each form of trauma in a typical year before the age of 18, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (almost every day). Each form of trauma was dichotomized into absence (0) or presence (1) and compiled to produce a total CCT score ranging from 0 to 8. A higher score indicated more exposure to several forms of trauma. The internal consistency of the measure was high in previous studies (Bigras et al., Citation2017; Bolduc et al., Citation2018) as well as in the current study ( = .90).

Psychological distress

The French version (Boyer, Préville, Légaré, & Valois, Citation1993) of the Psychiatric Symptom Index (PSI) (Ilfeld, Citation1976) was used to assess psychological distress. The PSI is a 14-item questionnaire assessing psychological distress based on four dimensions (i.e., depression, anxiety, cognitive disturbance, and anger), on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (very frequently). An example of an item is: “I got scared or worried about something.” Participants indicated the frequency with which they had experienced each statement in the last 7 days. This questionnaire is widely used and has shown adequate levels of internal consistency in previous studies (Bolduc et al., Citation2018; Godbout, Dutton, Lussier, & Sabourin, Citation2009) as well as in the current study ( = .92).

Mindfulness

Participants’ disposition toward mindfulness in daily life was assessed using the French version of the Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, Citation2003; translated by Jermann et al., Citation2009). The MAAS is a 15-item questionnaire rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never); higher scores indicate higher levels of dispositional mindfulness. Participants indicated how frequently they experienced several items such as “I tend to walk quickly to get where I’m going without paying attention to what I experience along the way.” Brown and Ryan (Citation2003) indicated good internal consistency among different populations. In the current study, the internal consistency was high ( = .89).

Sexual satisfaction

The French version of the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX; Lawrence & Byers, Citation1995) measured global satisfaction in regard to sexual relationships. The GMSEX is a 5-item questionnaire on a 7-point bipolar scale on which participants rate their sexuality: not good at all – very good, very unpleasant – very enjoyable, very negative – very positive, very unsatisfying – very satisfying, worthless – very precious. Higher total scores indicate greater sexual satisfaction. The measure's internal consistency was high in previous studies (Bigras et al., Citation2017) and in the current sample ( = .92).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and correlation analyzes were conducted using SPSS version 21 to examine sample characteristics and the relationships between the variables. Then, path analyses using Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2012) were conducted to estimate the hypothesized mediation model. First, the direct path between CCT and sexual satisfaction was estimated. Second, the mediation model was tested with CCT as the independent variable, dispositional mindfulness along with psychological distress as mediators, and sexual satisfaction as the outcome variable. The paths models tested were saturated models (0 df), and thus had perfect fit. For all significance tests, α was set at .05. Path analysis enabled simultaneous testing of the direct and indirect effects of multiple variables. A correlational design was used, in which CCT was a fixed historical marker (i.e., occurred in childhood and preceded adulthood experiences), and the mediators were postulated based on theoretical ground. Because some study variables were naturally nonnormally distributed (kurtosis varied between −.98 to .32 and skewness, between −.49 to .57), the maximum-likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and chi-square test statistics that are robust to nonnormality were used (MLR; Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2012). Missing data were minimal (<1%) and treated using full information maximum likelihood. To test mediation hypotheses, indirect effects were examined using Mplus model indirect (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2012) and 95% bootstrap (based on 20,000 random draws) confidence intervals (CI). This bias-corrected method is based on a distribution for the product of coefficients and generates standardized confidence limits for the value of the indirect effect coefficients; when zero is not in the confidence interval, the indirect effect is considered significant (MacKinnon & Fairchild, Citation2009).

The gender invariance was tested using a multiple group analysis. The mediation model with all paths constrained to be equal across groups was estimated and then compared with the configural model (i.e., all paths allowed to be freely estimated). A chi-square test difference was used to see if the difference between the constrained and saturated models is significant. A nonsignificant indicates evidence of invariance across men and women. Adding equality constraint on the parameters releases degrees of freedom, providing interpretable model fit indices. In that case, a nonsignificant

a ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (

/df) between 1 and 5, a comparative fit index (CFI) of .95 or higher, and the root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below .06 are indicators of a good fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Kline, Citation2011). However, the RMSEA tends to be more elevated and falsely indicates a poor fitting in small df models (Kenny, Kaniskan, & McCoach, Citation2015).

Results

Means and standard deviations of psychological distress, dispositional mindfulness, and sexual satisfaction are reported in . The majority of patients reported at least one experienced childhood interpersonal trauma, while 2% reported experiencing all 8 types assessed (see ). Analyses of variance (ANOVA) with polynomial contrasts indicated that there was a significant linear relationship between the accumulation of trauma experienced and increased psychological distress ((1, 400) = 35.47, p < 0.001, η2 = 8%), decreased dispositional mindfulness (F(1,400) = 70.04, p < .001, η2 = 14.7%), and decreased sexual satisfaction (F(1,397) = 24.82, p < .001, η2 = 5.7%). The prevalence of each form of childhood interpersonal trauma experienced is reported in . Correlation analyses (see ) supported the hypothesized relationships between the study variables. CCT was associated with higher psychological distress, as well as lower dispositional mindfulness and lower sexual satisfaction. Psychological distress was associated with lower sexual satisfaction, whereas dispositional mindfulness was related to higher levels of sexual satisfaction. Finally, psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness were negatively associated with one another.

Table 1. Descriptive data (mean and standard deviation) by number of childhood traumas.

Table 2. Prevalence of childhood interpersonal traumas according to gender.

Table 3. Correlations among study variables.

Integrative model

Results of the path analysis are illustrated in . The direct link between CCT and sexual satisfaction was first tested, with results showing a negative relationship ( = −0.238, p < .001) explaining 6% of the variance in sexual satisfaction. Then, integrating the mediating variables in the model led to a direct link between CCT and sexual satisfaction that was no longer significant; CCT was related to sexual satisfaction through greater levels of psychological distress and lower levels of dispositional mindfulness. More precisely, three significant mediation effects of the link from CCT to sexual satisfaction were observed. First, the product coefficient for the path from CCT to sexual satisfaction going sequentially through psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness was significant (b = −0.102, bootstrap 95% CI [−0.179, −0.047]), supporting the hypothesized sequential mediation. Results also supported the indirect effects for the effect of CCT on dispositional mindfulness through psychological distress (b = −0.084, bootstrap 95% CI [−0.133, −0.040]). Second, the product coefficient for the path from CCT to sexual satisfaction via psychological distress was significant (b = −0.241, bootstrap 95% CI [−0.410, −0.114]). Third, results also indicated a significant indirect effect of CCT on sexual satisfaction through dispositional mindfulness (b = −0.223, bootstrap 95% CI [−0.397, −0.097]). Overall, the final model explained 8% of psychological distress, 31% of dispositional mindfulness, and 19% of the variance in sexual satisfaction.

Gender invariances

A multi-group model was assessed in women and men, to ensure that the model was a good representation of the data in both groups. To examine gender invariance, the mediation model in which all paths were constrained to be equal across men and women was estimated. Results revealed a good adjustment fit: (6) = 11.795, p = .0667;

/df = 1.966; CFI = 0.975; RMSEA = .069, 90% IC (.000, .127), suggesting a good representation of women’s and men’s data. This constrained model was then compared with the saturated configural model (i.e., the same model in which all paths are allowed to be freely estimated). Results indicated that adding equality constraints did not lead to a significantly different change in the chi-square values,

(6) = −11.80, p = .07, suggesting that the mediation model is invariant in men and women seeking sex therapy.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness in the association between CCT and sexual satisfaction, among sex therapy patients. Overall findings suggest that mindfulness might be a key process explaining the link between CCT and lower sexual satisfaction. More precisely, three distinct significant indirect effects were found. First, the accumulation of CCT was related to lower sexual satisfaction through greater levels of psychological distress. Second, the relation between CCT and sexual satisfaction was also mediated through poorer dispositional mindfulness. Third, the hypothesized sequential mediation was found in which CCT was linked to greater levels of psychological distress, which were then related to poorer levels of dispositional mindfulness, in turn linked with lower sexual satisfaction. The results also confirmed the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationship between CCT and dispositional mindfulness. Previous studies found that survivors of CCT are at greater risk of experiencing psychological distress and lower sexual satisfaction (Bigras et al., Citation2017; Dugal et al., Citation2016), but this study is among the first to show empirical support for the hypothesis that CCT is related to sexual satisfaction through psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness. In an effort to better assess the implications of our results, we tested whether our model showed gender specificities and results showed gender invariance.

The current findings are consistent with previous research, which found that survivors of CCT tend to experience poorer sexual satisfaction (Bigras et al., Citation2017) due to negative inner experiences such as psychological distress (Delgado-Parra, Rojas-Flores, & Rubio-Aurioles, Citation2017; Sánchez-Fuentes, Santos-Iglesias, & Sierra, Citation2014), which in turn tend to compromise awareness of the present moment as it unfolds (Briere et al., Citation2010), but showed those links within an integrative model for the first time. The mediating role of dispositional mindfulness and psychological distress in the relationship between CCT and sexual satisfaction may be understood in the lens of the Pain Paradox Theory (Briere, Citation2015). Effectively, results show a potential vicious cycle where trauma-related distress is linked to lower dispositional mindfulness, which maintains or exacerbates distress and suffering, lowering sexual satisfaction. The results of Boughner, Thornley, Kharlas, and Frewen (Citation2016) also parallel the current findings and match the Pain Paradox theoretical framework as they yielded that lower dispositional mindfulness (i.e., describing, acting with awareness, and nonjudging traits) was a mechanism underlying the development of trauma-related distress among trauma survivors. In this study, CCT was found to be related to psychological suffering (i.e., psychological distress), which was sequentially linked with lower dispositional mindfulness – potentially suggesting an avoidance tendency to escape from painful inner states – and then to lower sexual satisfaction. Consequently, a lower disposition to be mindful is experienced, which paradoxically may maintain or exacerbate distress and bring more suffering (e.g., leading to lack of sexual satisfaction). As such, psychological distress and related poorer dispositional mindfulness in the aftermath of CCT may interfere with one’s ability to pay attention to, welcome pleasant internal (e.g., sexual sensations) or external (e.g., seeing the partner’s body) sexual cues and experience sexual satisfaction.

Based on this theory and our results, it is possible that psychological distress not only interferes with sexual satisfaction but that the context of sexuality itself evocates psychological distress in survivors of childhood interpersonal trauma (Stephenson, Hughan, & Meston, Citation2012), again diminishing their disposition toward mindfulness in the context of sexuality. As an alternative explanation, the current results may also reflect an underlying cyclic pattern in which psychological distress and dispositional mindfulness are related to one another. This vicious cycle may be experienced during sexual acts and disrupt sexual satisfaction, as the presence of distress or suffering could make it difficult to be in a mindful state and fully enjoy sexuality. Nevertheless, longitudinal data would be needed to test this recursive model hypothesis. The indirect effects yielded in the study highlight the complexity of the correlates and etiology of sexual satisfaction. As such, the current study offers an integrative empirically-based conceptual model, combining important individual and historical factors to explain sexual satisfaction. Results highlighted three mediation effects that allow a better understanding of the links between CCT and sexual satisfaction that could ultimately guide sex therapy interventions.

Our results imply that CCT could be detrimental to sexuality, due to its substantiated relation with increased psychological distress and decreased dispositional mindfulness. Not only diminishing psychological distress might contribute to sexual satisfaction but survivors who are able to more directly experience distress through higher mindfulness (i.e., mindful therapeutic exposure or other ways of experiencing and “sitting with” traumatic material) might be more likely to experience sexual satisfaction. In this sense, the practice of mindfulness could be recommended to survivors of CCT in order to improve couples’ sexual relationships, including paying attention to here-and-now sensations and reducing tendencies to evaluate or judge one’s own or one’s partner’s performance during sexual activities (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, Citation2006). Also, dispositional mindfulness may have a positive impact on both partners’ sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction, as higher levels of dispositional mindfulness may help to re-route one’s focus away from negative, critical, or anxiety-provoking cognitions and onto sensations that are happening during sexual activities with their partner, as they unfold from moment to moment, therefore promoting satisfying sexual experiences among partners (Briere, Citation2015; Brotto, Chivers, Millman, & Albert, Citation2016; Déziel et al., Citation2017). Partners presenting higher levels of dispositional mindfulness could be more aware of their internal (e.g., arousing sensations, thoughts, emotions) and external cues (e.g., erotic cues such as seeing the partner’s naked body), which may diminish the impact of interfering and/or irrelevant thoughts that may occur during sexual activities (Déziel et al., Citation2017; Dosch et al., Citation2016). Findings from Newcombe and Weaver (Citation2016) provided empirical support for those ideas, showing that lower dispositional mindfulness in women was associated with greater cognitive distraction (i.e., cognitions related to one’s own physical appearance and performance during sexual activities), leading to lower sexual satisfaction.

In that perspective, mindfulness training could increase awareness and distance from trauma-related negative encoded memories or internal discourse, which in turn would tend to increase sexual satisfaction. The integration of mindfulness interventions in clinical sexology builds on the original Masters and Johnson’s treatments for sexual dysfunctions where these authors referred to anxiety and to a state of anxious self-observing (i.e., ‘spectatoring’) that tend to interrupt sexual desire (Masters & Johnson, Citation1966, Citation1970). They developed Sensate Focus, a founding technique in sex therapy, which consists in stabilizing attention on the present moments' erotic experiences, rather than on expectations about sexual responsiveness. Partners are asked to focus on their own feelings and sensations and a nonjudgmental attitude is encouraged. As such, these instructions parallel what is currently referred to as a mindfulness-based intervention (Weiner & Avery-Clark, Citation2014). Yet, cultivating mindfulness also differs from Sensate Focus as mindfulness also refers to a disposition that can be trained on a daily basis that infuses all spheres of life and that does not require the participation of a partner (Brotto & Heiman, Citation2007). As such, interventions aiming to increase mindfulness might be beneficial to improve the sex lives of patients with sexual difficulties. Findings of empirical studies support the use of mindfulness-based interventions for sexual difficulties (Brotto & Basson, Citation2014). Results reveal that regular mindfulness practice can lead to increased dispositional mindfulness (Quaglia, Braun, Freeman, McDaniel, & Brown, Citation2016), indicating that mindfulness-based interventions and practice have the potential to deliver stable changes.

Finally, results show a high prevalence of childhood interpersonal trauma in our clinical sample of patients consulting for sex therapy. For example, in the current sample, the rates of childhood sexual abuse (25% in men and 53% in women) was found to be nearly thrice as high as those observed in community samples (i.e., 7.9% in men and 19.2% in women; Pereda, Guilera, Forns & Gómez-Benito, Citation2009). Similarly, rates of physical (49% in men and 49% in women) and psychological (60% in men and 65% in women) violence perpetrated by the parents during childhood appeared relatively high as compared with results from nonclinical studies (physical violence: 30% in men and 24% in women; psychological violence: 48% in men and 42% in women (Godbout et al. Citation2009). These results highlight the importance to assess and address experienced trauma in patients consulting for sexual difficulties and that trauma-informed interventions might be useful to target etiologic, aggravating, and maintenance factors associated to low sexual satisfaction.

Limitations and further studies

Interpretation of the present findings should take into account certain limitations. First, this study used a cross-sectional design and results should be replicated using a longitudinal method before causal relations can be inferred. The specific order of causation between the variables was hypothesized based on clinical and theoretical grounds and should be confirmed through multiple-wave longitudinal designs. Longitudinal data could also help to study the reciprocal dynamic between psychological distress and avoidance/lower mindfulness as depicted in the Pain Paradox theory (Briere et al., Citation2010). In addition, the use of self-reported questionnaires and retrospective measures of childhood interpersonal trauma may have introduced biases. Given the breadth of experiences associated with dispositional mindfulness, psychological distress, and sexual satisfaction, no single measure is likely to reflect the full range of each patient’s experience and further studies are needed to deepen our understanding of the link between CCT, psychological distress, dispositional mindfulness, and sexual satisfaction. Moreover, this study aimed to explore sexual satisfaction in patients consulting for sexual difficulties, but further research could explore the generalization of the current findings to other clinical populations and to the general population. Because CCT, psychological distress, and dispositional mindfulness only account for part of the variance of sexual satisfaction (19%), other variables must be taken into account (e.g., emotion regulation, dissociation). Finally, further studies are needed to confirm the potential beneficial role of mindfulness-based treatments to treat sexual difficulties among CCT survivors.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé.

References

- Althof, S. E., Leiblum, S. R., Chevret‐Measson, M., Hartmann, U., Levine, S. B., McCabe, M., … Wylie, K. (2005). Psychology: Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 2(6), 793–800. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00145.x

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504

- Berthelot, N., Godbout, N., Hébert, M., Goulet, M., & Bergeron, S. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of childhood sexual abuse in adults consulting for sexual problems. Journal of Marital and Sex Therapy, 40(5), 434–443. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2013.772548

- Bigras, N., Daspe, M. È., Godbout, N., Briere, J., & Sabourin, S. (2017). Cumulative childhood trauma and adult sexual satisfaction: Mediation by affect dysregulation and sexual anxiety in men and women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 43(4), 377–396. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2016.1176609

- Bigras, N., Godbout, N., & Briere, J. (2015). Child sexual abuse, sexual anxiety, and sexual satisfaction: The role of self-capacities. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24(5), 464–483. doi:10.1080/10538712.2015.1042184

- Bigras, N., Godbout, N., Hébert, M., & Sabourin, S. (2017). Cumulative adverse childhood experiences and sexual satisfaction in sex therapy patients: What role for symptom complexity? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(3), 444–454. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.013

- Bolduc, R., Bigras, N., Daspe, M.-È., Hébert, M., & Godbout, N. (2018). Childhood cumulative trauma and depressive symptoms in adulthood: The role of mindfulness and dissociation. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1594–1603. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-0906-3

- Boughner, E., Thornley, E., Kharlas, D., & Frewen, P. (2016). Mindfulness-related traits partially mediate the association between lifetime and childhood trauma exposure and PTSD and dissociative symptoms in a community sample assessed online. Mindfulness, 7(3), 672–679. doi:10.1007/s12671-016-0502-3

- Boyer, R., Préville, M., Légaré, G., & Valois, P. (1993). La détresse psychologique dans la population du Québec non institutionnalisée: Résultats normatifs de l'enquête Santé Québec. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 38(5), 339–343. doi:10.1177/070674379303800510

- Briere, J. (2002). Treating adult survivors of severe childhood abuse and neglect: Further development of an integrative model. In J. E. B. Myers, L. Berliner, J. Briere, C. T. Hendrix, T. Reid, & C. Jenny (Eds.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Briere, J. (2015). Pain and suffering: A synthesis of Buddhist and Western approaches to trauma. In V. M. Follette, J. Briere, D. Rozelle, J. Hopper, & D. I. Rome (Eds.), Mindfulness-oriented interventions for trauma: Integrating contemplative practices (pp. 11–30). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Briere, J., Godbout, N., & Dias, C. (2015). Cumulative trauma, hyperarousal, and suicidality in the general population: A path analysis. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 16(2), 153–169. doi:10.1080/15299732.2014.970265

- Briere, J., Hodges, M., & Godbout, N. (2010). Traumatic stress, affect dysregulation, and dysfunctional avoidance: A structural equation model. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 767–774. doi:10.1002/jts.20578

- Briere, J. N., & Scott, C. (2014). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment (DSM-5 update). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Brotto, L. A., & Basson, R. (2014). Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57(1), 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.001

- Brotto, L. A., Chivers, M. L., Millman, R. D., & Albert, A. (2016). Mindfulness-based sex therapy improves genital-subjective arousal concordance in women with sexual desire/arousal difficulties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 1907–1921. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0689-8

- Brotto, L. A., & Goldmeier, D. (2015). Mindfulness interventions for treating sexual dysfunctions: The gentle science of finding focus in a multitask world. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(8), 1687–1689. doi:10.1111/jsm.12941

- Brotto, L. A., & Heiman, J. R. (2007). Mindfulness in sex therapy: Applications for women with sexual difficulties following gynecologic cancer. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 22(1), 3–11. doi:10.1080/14681990601153298

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

- Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. doi:10.1080/10478400701598298

- Cash, M., & Whittingham, K. (2010). What facets of mindfulness contribute to psychological well-being and depressive, anxious, and stress-related symptomatology? Mindfulness, 1(3), 177–182. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0023-4

- Cohen, J. R., Menon, S. V., Shorey, R. C., Le, V. D., & Temple, J. R. (2017). The distal consequences of physical and emotional neglect in emerging adults: A person-centered, multi-wave, longitudinal study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 63, 151–161. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.030

- Delgado-Parra, V., Rojas-Flores, A., & Rubio-Aurioles, E. (2017). Self-reported depression: Its impact on sexual satisfaction and sexual function, an internet based survey. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(1), S118. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.11.275

- Delker, B. C., Smith, C. P., Rosenthal, M. N., Bernstein, R. E., & Freyd, J. J. (2018). When home is where the harm is: Family betrayal and posttraumatic outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 27(7), 720–743. doi:10.1080/10926771.2017.1382639

- Deng, Y.-Q., Li, S., & Tang, Y.-Y. (2014). The relationship between wandering mind, depression and mindfulness. Mindfulness, 5(2), 124–128. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0157-7

- Desrosiers, A., Vine, V., Klemanski, D. H., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). Mindfulness and emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: Common and distinct mechanisms of action. Depression and Anxiety, 30(7), 654–661. doi:10.1002/da.22124

- Dèttore, D., Pucciarelli, M., & Santarnecchi, E. (2013). Anxiety and female sexual functioning: An empirical study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(3), 216–240. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2011.606879

- Déziel, J., Godbout, N., & Hébert, M. (2017). Anxiety, dispositional mindfulness, and sexual desire in men consulting in clinical sexology: A mediational model. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(5), 513–520. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405308

- Dosch, A., Rochat, L., Ghisletta, P., Favez, N., & Van der Linden, M. (2016). Psychological factors involved in sexual desire, sexual activity, and sexual satisfaction: A multi-factorial perspective. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 2029–2045. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0467-z

- Dove, N. L., & Wiederman, M. W. (2000). Cognitive distraction and women’s sexual functioning. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278650

- Dugal, C., Bigras, N., Godbout, N., & Bélanger, C. (2016). Childhood interpersonal trauma and its repercussions in adulthood: An analysis of psychological and interpersonal sequelae. In G. El-Baalbaki & C. Fortin (Eds.), A multidimensional approach to post-traumatic stress disorder: From theory to practice. Rijeka: InTechOpen. doi:10.5772/64476

- Follette, V. M., & Pistorello, J. (2007). Finding life beyond trauma: Using acceptance and commitment therapy to heal from post-traumatic stress and trauma-related problems. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Frewen, P. A., Evans, E. M., Maraj, N., Dozois, D. J. A., & Partridge, K. (2008). Letting go: Mindfulness and negative automatic thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(6), 758–774. doi:10.1007/s10608-007-9142-1

- Godbout, N., Bigras, N., & Dion, J. (2016). Présence attentive et traumas interpersonnels subis durant l’enfance [mindfulness and child maltreatment]. In S. Grégoire, L. Lachance, & L. Richer (Eds.), La présence attentive (mindfulness): État des connaissances théoriques, empiriques et pratiques (pp. 229–246). Quebec, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec (PUQ).

- Godbout, N., Dutton, D., Lussier, Y., & Sabourin, S. (2009). Early experiences of violence as predictors of intimate partner violence and marital adjustment, using attachment theory as a conceptual framework. Personal Relationships, 16(3), 365–384. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01228.x

- Godbout, N., Runtz, M., MacIntosh, H., & Briere, J. (2013). Childhood trauma and couple relationships. Integrating Science & Practice, 3(2), 14–17.

- Godbout, N., Bigras, N., & Sabourin, S. (2017). Childhood Cumulative Trauma Questionnaire. Unpublished. Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada.

- Hu, L. -T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- Ilfeld, F. W. (1976). Further validation of a psychiatric symptom index in a normal population. Psychological Reports, 39(3_suppl), 1215–1228. doi:10.2466/pr0.1976.39.3f.1215

- Jermann, F., Billieux, J., Larøi, F., d'Argembeau, A., Bondolfi, G., Zermatten, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2009). Mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS): Psychometric properties of the French translation and exploration of its relations with emotion regulation strategies. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 506–514. doi:10.1037/a0017032

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte.

- Kalmakis, K. A., & Chandler, G. E. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: Towards a clear conceptual meaning. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(7), 1489–1501. doi:10.1111/jan.12329

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods and Research, 44(3), 486–507. doi:10.1177/0049124114543236

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Lawrence, K. A., & Byers, E. S. (1995). Sexual satisfaction in long‐term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 2(4), 267–285. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x

- MacKinnon, D. P., & Fairchild, A. J. (2009). Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 16–20. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x

- Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human sexual response. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

- Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1970). Human sexual inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

- Masuda, A., & Tully, E. C. (2012). The role of mindfulness and psychological flexibility in somatization, depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress in a nonclinical college sample. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 17(1), 66–71. doi:10.1177/2156587211423400

- Mayer, B., Polak, M. G., & Remmerswaal, D. (2019). Mindfulness, interpretation bias, and levels of anxiety and depression: Two mediation studies. Mindfulness, 10(1), 55–65. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-0946-8

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Newcombe, B. C., & Weaver, A. D. (2016). Mindfulness, cognitive distraction, and sexual well-being in women. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 25(2), 99–108. doi:10.3138/cjhs.252-A3

- Pereda, N., Guilera, G., Forns, M., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2009). The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007

- Quaglia, J. T., Braun, S. E., Freeman, S. P., McDaniel, M. A., & Brown, K. W. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for effects of mindfulness training on dimensions of self-reported dispositional mindfulness. Psychological Assessment, 28(7), 803–818. doi:10.1037/pas0000268

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M. D. M., Santos-Iglesias, P., & Sierra, J. C. (2014). A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 14(1), 67–75. doi:10.1016/S1697-2600(14)70038-9

- Slonim, J., Kienhuis, M., Di Benedetto, M., & Reece, J. (2015). The relationships among self-care, dispositional mindfulness, and psychological distress in medical students. Medical Education Online, 20(1), 27924. doi:10.3402/meo.v20.27924

- Stephenson, K. R., Hughan, C. P., & Meston, C. M. (2012). Childhood sexual abuse moderates the association between sexual functioning and sexual distress in women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(2), 180–189. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.015

- Tomlinson, E. R., Yousaf, O., Vittersø, A. D., & Jones, L. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 9(1), 23–43. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0762-6

- Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Godbout, N., Sabourin, S., Briere, J., Lussier, Y., & Runtz, M. (2016). Adult sexual outcomes of child sexual abuse vary according to relationship status. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42(2), 341–356. doi:10.1111/jmft.12154

- Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Godbout, N., Sabourin, S., Péloquin, K., & Wright, J. (2014). Les séquelles conjugales d’une agression sexuelle vécue à l’enfance ou à l’adolescence. Carnet de Notes Sur Les Maltraitances Infantiles, 3(1), 21–41. Retrieved from https://www.cairn.info/revue-carnet-de-notes-sur-les-maltraitances-infantiles-2014-1-page-21.htm.

- Weiner, L., & Avery-Clark, C. (2014). Sensate focus: Clarifying the Masters and Johnson's model. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(3), 307–319. doi:10.1080/14681994.2014.892920