Abstract

In the present study we investigated the temporal associations between emotional intimacy, daily hassles, and sexual desire of individuals in long-term relationships, and examined the direct and moderating effects of attachment orientation. We investigated these variables by reanalyzing an existing data set. Experience sampling methodology was used to collect data 10 times per day, across seven days. Attachment orientation was assessed with the Experiences in Close Relationships questionnaire. Age, gender, and relationship duration were added as predictors. Data of 134 participants (Nfemale = 87) were analyzed. Only one of the partners of a couple participated. Men overall reported higher sexual desire than women. Longer relationship duration was associated with lower sexual desire, but age was not associated with sexual desire. Increased level of intimacy predicted sexual desire across measurements with an average time interval of 90 min, but this effect was no longer significant when assessment points were 180 min apart. Daily hassles did not predict sexual desire at subsequent assessments. Avoidant and anxious attachment were not associated with sexual desire level. No interaction effects of gender, stress, intimacy and attachment orientation on sexual desire were found. Speculative explanations are offered for the absence of stress effects.

Introduction

Attachment theory provides an important framework for understanding the dynamics of partner interactions in romantic relationships across the lifespan. Because the attachment system primarily serves an emotion-regulation purpose, attachment theory can help explaining how individuals cope with stressful or threatening situations within the context of their sexual relationship. Stress and intimacy are both relevant variables in light of attachment theory. Stress is the main trigger to activate attachment strategies, which evokes proximity seeking behavior that is oriented toward attaining security. Feelings of intimacy are a likely result of this sense of security. Hence, in the context of relationships, attachment behavior is directed toward (re)gaining intimacy with the partner as to appease the attachment system and further promote exploratory behavior. On the other hand, intimacy might also act as a buffer to prevent attachment system activation when facing relational or sexual challenges (Little, McNulty, & Russell, Citation2010; Wagner, Mattson, Davila, Johnson, & Cameron, Citation2020). Although sex research has focused increasingly on the interactions between individual and interpersonal variables, including attachment orientation (Muise, Citation2013; Pistole, Roberts, & Chapman, Citation2010; Rubin & Campbell, Citation2012; Stephenson & Meston, Citation2010; van Lankveld, Jacobs, Thewissen, Dewitte, & Verboon, Citation2018; Yoo, Bartle-Haring, Day, & Gangamma, Citation2014), the role of daily-hassles related stress and intimacy in sexual functioning has scarcely been investigated from an attachment perspective.

Attachment and sexual functioning

Attachment theory is not only an influential theoretical framework for understanding relational functioning, but also for sexual outcomes. The attachment-based emotion regulation system helps the individual to respond to sexual situations. Based on adult attachment theory (Belsky, Citation1997; Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, Citation1991; Birnbaum, Citation2010; Dewitte, Citation2012; Feeney & Noller, Citation2004; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007), securely attached individuals are assumed to approach both solitary and partnered sexual activity with self-confidence and trust. They can engage in sexual activity for the mere joy of it, and sexual interaction does not serve attachment needs. Insecurely attached persons, however, react in a more defensive way to sexual stimuli and opportunities for sexual encounters. Anxiously attached individuals have a strong desire to feel loved and protected and may use sex for securing proximity with their partner. Because their sexual behavior is driven by their unsatisfied attachment needs, they feel worried and anxious during sexual contact, turning the latter into a stressful experience (Dewitte, Citation2012). Their attachment system is easily activated, because they have a low threshold for perceiving potential threat, especially in situations that signal relational conflict and threaten intimacy. In those situations, they tend to rely on hyperactivating strategies that include negative interpretations of the ongoing interaction, hypervigilance, and a strong need to feel that their partner is available and willing to calm their emotional turmoil. Avoidantly attached individuals, in contrast, predominantly attempt to cope with threat alone. They feel overwhelmed when they become too close to others, including their romantic partners. They tend to use deactivating strategies, such as keeping emotional distance, for the purpose of preserving their sense of control over the interaction and feeling autonomous, which may result in emotional distancing from their partner (Dewitte, Citation2012; Mikulincer, Shaver, Bar-On, & Ein-Dor, Citation2010; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007).

Although it has been assumed that the link between attachment and sex works the same in men and women (Mizrahi, Reis, Maniaci, & Birnbaum, Citation2019), gender differences have been found. In a study among couples seeking couple therapy (Brassard, Peloquin, Dupuy, Wright, & Shaver, Citation2012), anxious attachment in male participants predicted sexual dissatisfaction in their female partners, while avoidant attachment in female participants predicted sexual dissatisfaction in their male partners. Similar effects were found in a study of DeHaas (Citation2015). In a longitudinal study on sexual desire among newly wed couples Mizrahi and colleagues (Citation2019) found that over a period of eight months, anxiously attached men reported diminishing sexual desire, whereas sexual desire in low-anxious men did not change. High avoidant attachment, however, predicted decreases in dyadic sexual desire in both genders.

The involvement of intimacy and stress in the attachment model of sexual functioning

From an attachment perspective, elevated stress levels and intimacy between partners are crucial factors in, respectively, triggering and appeasing the individual’s emotion-regulation system (Dewitte, Citation2012). Stress can be induced by various stressors, emerging from both internal and external sources, and can be transient or chronic. The evidence on the impact of various types of perceived stress on sexual functioning is mixed. Daily hassles, comprised of various negatively evaluated daily activities, including small negative events that are not under the control of the individual, such as being stuck in traffic, and receiving bills, constitute an important external source of stress (Wright, Aslinger, Bellamy, Edershile, & Woods, Citation2019). The empirical findings on the association between daily hassles-related stress and sexual functioning were thus far contradictory. In a cross-sectional study in Iran, a negative association between event-related stress, including daily hassles, within the last month and sexual desire was found (Abedi, Afrazeh, Javadifar, & Saki, Citation2015), whereas no association was found between daily hassles-related stress and sexual desire in another cross-sectional study (Hamilton & Julian, Citation2014). Unexpectedly, daily hassles were found to be positively related to sexual desire in a study of Morokoff and Gillilland (Citation1993). Other types of stress have shown negative associations with sexual function, including a negative link between social stress, related to work and career pressure, and sexual desire (Avery-Clark, Citation1986; Bodenmann, Ledermann, Blattner, & Galluzzo, Citation2006), and between internal stress, including relational tensions, and various aspects of sexual functioning (Bodenmann, Ledermann, et al., Citation2006) and sexual desire and sexual activity (Dewitte & Mayer, Citation2018). It is currently unknown on which time scale transient daily hassles impact sexual desire. As daily hassles-related stress increases and decreases during the day, its effects on sexual desire can be expected to be transient. Therefore, as the time between the experience of a stressor and the measurement of sexual desire increases, the effects of daily hassles on desire will diminish.

Intimacy buffers the effects of stress and insecure attachment on sexual functioning

Emotional intimacy between partners is another important relational factor in the attachment model of sexual functioning, and serves both as a determinant and as an outcome of attachment (Dewitte, Citation2012). An influential definition of intimacy is that of Sternberg, defining it as the experience of strong feelings of closeness, connectedness and bonding (Sternberg, Citation1986). Intimacy has been theorized to buffer daily hassles-related stress, and thereby contribute to relationship quality, partners’ wellbeing, and adjustment (Levine, Citation1991; Prager, Citation1997; Yoo et al., Citation2014). With regard to sexual desire, a circular process has been assumed, with intimacy serving both as a trigger for sexual desire, and as a reward created by the experience of sexual arousal and - in particular - of orgasm (Basson, Citation2000, Citation2001).

To the best of our knowledge, only bivariate associations of intimacy and stress with sexual functioning have thus far been empirically investigated (Birnbaum, Cohen, & Wertheimer, Citation2007; Bodenmann, Pihet, & Kayser, Citation2006; Stephenson & Meston, Citation2010). In longitudinal studies emotional intimacy was found to play a crucial role in long-term relationships in maintaining sexual desire and partnered sexual activity. Intimacy was found to increase the odds for the occurrence of partnered sexual activity in both men and women in a longitudinal daily diary study (Dewitte, van Lankveld, Vandenberghe, & Loeys, Citation2015). In a study using experience-sampling methodology (ESM) in women and men in committed relationships, the association between emotional intimacy and partnered sexual activity was found to be fully mediated by sexual desire (van Lankveld et al., Citation2018). In emerging adult couples, gender differences were found regarding the associations of sexual desire and emotional intimacy with relationship quality and physical intimacy enjoyment (Shrier & Blood, Citation2016). In cross-sectional research sexual desire was also found to have significant associations with intimacy (Prekatsounaki, Janssen, & Enzlin, Citation2019; Stephenson & Meston, Citation2010). Similar to stress, intimacy fluctuates during the day, and its effects on sexual desire can therefore be expected to be transient. We therefore predict that the effects of intimacy will decrease with a greater time difference between the measurement moments of intimacy and sexual desire. In the beforementioned studies sexual desire was also found to be more strongly related to stress in non-anxiously than in anxiously attached individuals. These findings, therefore, suggest a moderating effect of intimacy and attachment orientation on the associations between daily hassles and intimacy with sexual desire. Consequently, in individuals with stronger avoidant attachment, intimacy will have a stronger moderating effect on the association of daily hassles and sexual desire than in participants with weaker avoidant attachment. In these participants higher intimacy will buffer the effect of daily hassles-related stress on sexual desire.

The present study

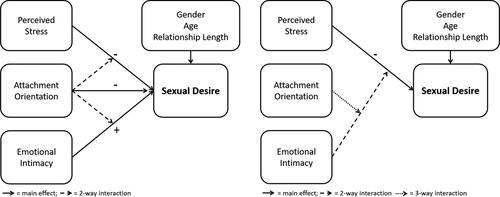

In the present study we investigated the temporal associations between emotional intimacy, daily hassles-related stress and sexual desire of individuals in long-term relationships. Additionally, we explored the potential role of attachment orientation in relation to sexual desire, both directly, and as a moderating factor of the link between stress, intimacy and sexual desire (see ). The link between stress, intimacy and sexual desire has not yet been examined in a multivariate and longitudinal study design. In a previous paper on this dataset, we focused on the associations of intimacy with sexual desire and partnered sexual activity [blinded for review]. Although the data for the present purpose were collected together with the data that were central in the previous paper, a separate analysis of the data was warranted to fill the gap in the literature with regard to the longitudinal study of these variables. We employed ESM methodology, assessing the constructs of interest at randomized, multiple times during the day, and across multiple days. ESM yields data with high ecological validity and can provide realistic representations of human experiences and behavior that are reported under natural conditions in daily life (Hektner, Schmidt, & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2007; Mehl & Conner, Citation2012; Myin-Germeys et al., Citation2009). The brief time elapsed between an event and the participant’s report on it, helps reducing memory bias compared with retrospective self-reports on experiences across longer spans of time (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, Citation2003).

Figure 1. Multifactorial model of sexual desire: hypothesized main and interaction effects of daily hassles-related stress, intimacy, and attachment orientation

Daily hassles-related stress was operationalized as stress related to daily activities, including household chores and routine tasks. In previous experience-sampling research using the same operationalization, daily hassles were found to predict salivary cortisal excretion, indexing overactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in response to stress (Jacobs et al., Citation2007). Other ESM research has also supported the assessment of daily hassles-related stress using the same operationalization as we use in the current study (Collip et al., Citation2013; Vaessen, van Nierop, Reininghaus, & Myin-Germeys, Citation2015).

Because relationship duration is a predictor of the level of sexual desire in romantic relationships (Klusmann, Citation2002; Liu, Citation2003; Murray & Milhausen, Citation2012), although more so in women than in men (Murray & Milhausen, Citation2012), gender and relationship duration were included as predictors in all analyses. As relationship duration may be confounded by age, the latter was also included as a predictor.

Sexual desire was predicted to vary as a function of level of emotional intimacy, daily hassles-related stress, and level of anxious and avoidant attachment. The following hypotheses were tested:

Daily hassles-related stress is negatively associated with level of sexual desire. Higher stress will be followed by lower desire.

Emotional intimacy is associated with level of sexual desire. Higher intimacy will be followed by higher desire.

The strength of the association of intimacy and stress with sexual desire will diminish with increasing latency between the measurements of stress and desire.

High level of avoidant attachment is associated with low sexual desire.

The associations between stress level and sexual desire are moderated by emotional intimacy. Stress is more strongly associated with sexual desire at lower levels of emotional intimacy; this association is weaker at higher intimacy levels.

The associations between stress level and sexual desire are moderated by the interaction of avoidant attachment and emotional intimacy.

Methods

Sample

Participants were recruited by master students of the [blinded for review], securing wide geographical distribution in [blinded for review]. Participant inclusion criteria were: (a) having a romantic heterosexual relationship of at least six months duration, (b) at least 18 years of age, and (c) [blinded for review] language mastery and having completed at least 8 years of education (to ensure comprehension of the questionnaires). Due to the characteristics of the student population of the [blinded for review], the sample was heterogeneous with regard to age, working status, ethnic background, and income level. The sample was also heterogeneous with regard to level of education, although it was skewed toward higher education level.

Data of 134 participants (Nfemale = 87) were available for analysis. Demographic characteristics are shown in . Male participants’ mean age was 46.4 years (SD = 11.4). They reported an average of 13.5 years (SD = 3.1) of education. Female participants’ mean age was 39.2 years (SD = 10.7), and they reported a mean of 13.6 years (SD = 2.4) of education. Average relationship duration was 14.6 years (SD = 11.0) ranging from 1 to 47 years. Eighty-nine percent of female participants and 96% of male participants self-identified as Caucasian. Except for one couple, only one of the partners of a couple participated.Footnote1

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Experience sampling method (ESM)

During seven consecutive days, participants completed a brief questionnaire ten times per day. They wore a wristwatch that delivered auditory prompts (‘beeps’) to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire was to be completed immediately after hearing the beep. Participants were asked to complete a few example questionnaires to ascertain their full comprehension of the instructions. The beeps were delivered between 7:30 AM and 10:30 PM. They were quasi-randomly distributed around fixed time points separated by 90 min each, with a maximum deviation of 20 min (de Vries, Citation1992). Participants reported the exact time when finishing each questionnaire. The recorded time was compared to the programmed time of the beep. When more than 15 min had elapsed after the beep signal, a report was considered less reliable. These data were not further used in the analyses. To produce a valid data set, at least one-third of the reports were required (Delespaul, Citation1995). In addition to the ten questionnaires, participants were instructed to complete an early morning and a late evening diary each day. These reports were given contingent on, respectively, the moment of waking up and going to sleep. The late evening diary informed about the period since the last beep signal in the evening. The early morning diary informed about the period since the last diary before going to sleep, thus also including the entire night.

Procedure

Upon showing their interest, participants received written information about the study and ESM. An informed consent form was read and signed, and an online questionnaire was completed, after which an interview was scheduled, that was conducted face-to-face or by telephone. The interview took place on the last day before the start of data collection. After receiving extensive explanation of the study procedures, participants were asked if they had any remaining questions. During this session, participants practiced with completion of the ESM questionnaire. They then also received the wristwatch and seven ESM diary booklets. Data were kept anonymous. Questionnaire booklets were only marked with a research code and were sent by postal mail using pre-stamped envelopes to a fellow researcher, with whom the respondent was not acquainted. This person entered the diary data into the database. Participants did not receive any compensation. Ethical approval of the Institutional Review Board of the Open University of the Netherlands was obtained.

Sexual desire

Sexual desire was measured at the beep level as the mean score of three items, using 7-point Likert scales (1 = not at all, 7 = very strongly). Item wordings were: At this moment … “I would like to have sex,” “I feel sexually excited” and “I am open to sexual initiative.” The selected wordings reflect the current consensus in the field of sex research with regard to sexual desire as comprised of both proactive and reactive elements and of sexual arousal, particularly in women (Basson, Citation2002). The three items were highly inter-correlated (rs = 0.76, 0.81, 0.85). The reliability, McDonald’s ω (McDonald, Citation1999), of the sexual desire factor at the beep level and, after aggregation, at the person was determined with a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis using MPLUS (Mplus version 7.3). The intraclass correlations of the three items ranged between 0.41 and 0.43. A one-factor model fitted the data very well: CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.02; SRMR = 0.00 (within) and 0.013 (between). After data aggregation at the person level, the estimated reliability was 0.86. At the beep level, the estimated reliability was 0.72.

Intimacy

Intimacy was measured at the beep level with five items using 7-point Likert scales (1 = not at all, 7 = very strongly). Item wordings were based on Sternberg’s description of state intimacy: “Towards my partner I now feel … ‘Intimacy’, ‘Connectedness’, ‘Love’, ‘Tenderness’, and ‘Warmth’.” Participants also recorded their response to these items in the absence of their partner. Intimacy was defined as the mean score of these five items, denoting feelings of intimacy toward the partner. The items were answered using seven-point rating scales with category labels: 1 = “not,” 4 = “moderately strong,” 7 = “very strong.” The reliability, McDonald’s ω (McDonald, Citation1999), of the intimacy factor at the person (i.e. aggregated over all assessments within a person) and at the beep level was determined with a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis using MPLUS (Mplus version 7.3, see [blinded for review], for statistical details). The intraclass correlations for the five items were high, ranging between .59 and .65 (McGraw & Wong, Citation1996). A one-factor model fitted the data well: CFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.038 (within) and 0.045 (between). At the person level, the estimated reliability was 0.91. At the beep level, the estimated reliability was 0.90.

Daily hassles-related stress

Daily hassles-related stress was operationalized as stress related to daily activities. Stress level was assessed at the beep level and was measured with two items. First, respondents were asked to describe the activity they were involved it at the moment (“What am I doing?….”). The subsequent item wordings were: “I would rather do something else,” and “It takes effort to do this.” Responses were given on 7-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (“Not”) to 7 (“Very much”). The scores on both items were summed up to calculate the stress scores. Higher scores represented higher levels of stress. The reliability of the daily hassles scale could not be assessed, as it consisted of only two items. At the beep level of measurement, the two items were found to correlate significantly with a large effect size, r = .61.

Anxious and avoidant attachment orientation

Whereas sexual desire, daily hassles stress, and emotional intimacy were considered as fluctuating and highly context-dependent experiences that can best be measured at the beep level of the individual participant, anxious and avoidant attachment orientation were considered to reflect more stable factors at the level of the person. They were therefore measured before the start of the ESM measurements, using the Dutch translation and adaptation of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) Questionnaire (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, Citation1998) of Conradi and colleagues (Conradi, Gerlsma, van Duijn, & de Jonge, Citation2006). It comprises 36 items. Responses were given on 7-point scales ranging from 1 (“totally disagree”) to 7 (“totally agree”). The items represented attachment-related feelings and behaviors toward romantic partners. The ECR is used to assess adult attachment orientation on the dimensions of anxious attachment and avoidant attachment. In [blinded for review purposes] populations internal consistencies were high with Cronbach’s α ranging from .85 to .93 for both scales (Conradi et al., Citation2006). Subscale scores were calculated as the mean of the item scores for anxious and avoidant attachment. An example item in the anxious attachment subscale is (“I worry a fair amount about losing my partner”). An example of an item in the avoidant attachment subscale is (“I try to avoid getting too close to my partner”). High scores represent strong anxious or avoidant attachment orientations. The ECR was found to discriminate well between various attachment orientations (Alonso-Arbiol, Balluerka, Shaver, & Gillath, Citation2008).

Data analysis

Correlations between the core variables were calculated. Before hypothesis testing all data were person-centered. The person means of intimacy and daily stress were saved as new variables to be used as predictors in the analyses. Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested using data at the assessment (“beep”) level, which represents the lowest data level comprising the richest information. Level of sexual desire was entered as criterion variable in all analyses. Sexual desire at t − 1 was entered as predictor in the first step in all analyses to correct for autoregressive effects. Prediction of sexual desire at assessment (t) by stress and intimacy levels at previous assessments (respectively, at t − 1 and t − 2), was tested in a multilevel linear regression analysis in R (R Core Team, Citation2016) using the package lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Citation2015). Hypotheses 4 was tested with attachment measured at baseline as predictor. To test hypothesis 5, that intimacy moderated the effect of stress on sexual desire, we added the interaction term between intimacy and stress to the model. To test hypothesis 6 the interaction terms of intimacy and stress with attachment orientation were entered in the model. Age, relationship duration, anxious and avoidant attachment, the person means of intimacy and daily hassles, and gender were included as person-level predictors in the model. We assumed random intercepts and random effects of intimacy and stress across participants in the models.

Statistical power for a cross-level interaction effect was calculated using the R Shiny web application (Lafit et al., Citation2020). Based on the analyses (effect size of d = 0.06, with 134 participants with (on average) 47 observations per participant) the power for detecting this 2-way interaction was 90%.

Results

Preliminary analyses

None of the participants enrolled in the study fully dropped out. A comparison of those who followed through and those dropped out was therefore not possible. Full compliance would have resulted in 70 valid data records per participant. The median was 56 questionnaires (80%) completed. This is commonly found in ESM studies in general population samples (Jacobs et al., Citation2005). No pattern was found for missing time of assessment. The number of missing observations increased somewhat as participation in the study progressed.

Associations between intimacy, stress, attachment orientation, and sexual desire

Mean scores at the lowest level of assessment (“beep level”) of the variables of interest are shown in . The overall level of sexual desire, after aggregation at the person level, differed between men and women (t = 3.68, p = .0004). Men generally reported higher sexual desire than women. Correlations between the core variables were calculated before person-centering all data, see .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics averaged at the beep level of assessment in the full sample (N = 134).

Table 3. Cross-sectional correlations between the primary variables in the model, before person-centering.

To investigate the temporal associations between intimacy, stress, attachment orientation and sexual desire, we tested two multilevel models, the first with predictors measured at T − 1, the second with predictors measured at T − 2. In each model sexual desire at T − 1 was used as covariate to correct for autoregressive effects. Results of these analysis are shown in and . The overall level of sexual desire again differed between men and women (p = .0004), and was also predicted by relationship duration (p = .006), with longer duration predicting lower level of desire. The person means of intimacy significantly predicted sexual desire level (p = .006), with higher perceived intimacy predicting higher sexual desire. Also the person means of daily hassles-related stress were a significant predictor (p = .008), with higher stress predicting higher sexual desire. Anxious and avoidant attachment did not predict level of sexual desire. A one-point increase in intimacy at the previous time point (T − 1) was associated with a subsequent 0.035 point increase in sexual desire at time point T (p = .020). Daily hassles stress at the previous beep did not predict sexual desire. The two- and three-way interactions, including the interactions with participant gender were not significant.

Table 4. Full model with lagged 1 predictors, with lagged-1 sexual desire to model the auto-correlation.

Table 5. Full model with lagged 2 predictors, with lagged 2 sexual desires to model the auto-correlation.

The analyses of the models with intimacy and stress at T − 2 as predictors showed that with increasing time lags the magnitude of the predictor effect of intimacy became non-significant (). The effects of the other variables in the model did not change.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, using the experience sampling method to collect high-frequency diary data, level of intimacy was found to predict level of sexual desire at the subsequent measurement point about 90 min later. Intimacy did no longer significantly predict sexual desire when assessment points were approximately 180 min apart. Daily hassles did not predict sexual desire. Level of anxious and avoidant attachment, assessed only once at baseline, did not predict sexual desire. The additional prediction from the theoretical model, that participants’ attachment orientation would interact with intimacy to moderate the association between stress and sexual desire was also not supported: the three-way interaction effects that included attachment orientation were not significant. Although a main effect of gender was found on sexual desire, showing that men reported higher levels of sexual desire, no interactions of gender with the key variables in our study were found.

The finding that intimacy predicts sexual desire when both are measured within a limited interval confirms other cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Dewitte et al., Citation2015; Prekatsounaki et al., Citation2019; Shrier & Blood, Citation2016) and was already discussed in a previous paper of our group written on the present data set [blinded for review]. It supports predictions from the attachment model of sexuality (Dewitte, Citation2012) and the circular model of sexual desire (Basson, Citation2000).

In the present study daily hassles did not prospectively predict sexual desire, whereas they were shown to positively predict sexual desire in both women and men when aggregated at the person level. These findings differ from previously reported associations of stress and sexual desire, based on longitudinal (Raisanen, Chadwick, Michalak, & van Anders, Citation2018), as well as cross-sectional data (Abedi et al., Citation2015). Raisanen and colleagues (Citation2018) found that stress negatively predicted partnered sexual desire in women, but positively predicted sexual desire in men. Abedi and colleagues (Citation2015) only investigated women and found a negative association between stress level and sexual desire. The observed differences may partly be explained by different operationalizations of daily hassles related stress. In Raisanen et al. (Citation2018) study, stress was measured as monthly assessed cortisol response without specifying its origin. In the Abedi et al. (Citation2015) study, stress was self-reported as stressful events in the past month. Stress in our study was also self-reported, but in a longitudinal study design, enabling the testing of associations of stress and sexual desire across time. However, although other types of daily stress covary with sexual desire in cross-sectional designs, the current findings based on longitudinal data do not support the notion of daily hassles as a causal determinant of sexual desire. Other stressors, including internal stress from relational discord (Bodenmann, Ledermann, et al., Citation2006; Dewitte & Mayer, Citation2018), social stress, related to work and career pressure (Avery-Clark, Citation1986; Bodenmann, Ledermann, et al., Citation2006), or event-related stress may, nevertheless, be relevant activating factors of the attachment-based emotion regulation mechanism. Further longitudinal research on these types of stress may clarify the link between stress and sexual desire.

In the present study, the hypothesized moderating effect of emotional intimacy on the association between stress and sexual desire (Dewitte, Citation2012; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007) was not found despite high statistical power (90%) (Lafit et al., Citation2020). A possible explanation could be that the emotion-regulation mechanism, by which stress activates intimacy needs, may be activated more frequently in distressed or dysfunctional couples than in the present healthy community sample (Brandão et al., Citation2019; Dubé, Corsini-Munt, Muise, & Rosen, Citation2019; Rick, Falconier, & Wittenborn, Citation2017).

Both anxious and avoidant attachment did not predict sexual desire in our sample. Based on the literature (Little et al., Citation2010; Overall & Lemay, Citation2015) it is surprising that stronger feelings of intimacy are not buffering sexual desire in insecurely attached individuals. In the attachment theory and previous research (Birnbaum & Reis, Citation2012; Favez & Tissot, Citation2017) a link of avoidant attachment with low sexual desire is reported. The failure to find this link with anxious attachment might reflect the ambivalent stance of anxiously attached individuals when it comes to sexuality. On the one hand, anxious individuals crave sex as a means to increase intimacy and connection with the partner. On the other hand, their sexual desire is mainly driven by feelings of insecurity, resulting in worries and negative emotions, which may lower sexual desire. Individuals with high anxious attachment were found to experience stronger sexual desire when the potential partner exhibited more responsivity to their needs (Birnbaum & Reis, Citation2012). The fact that intimacy did not moderate the association with avoidant attachment might reflect a defensive strategy to deactivate intimacy-related concerns, implying that feelings of intimacy will have less impact on avoidant individuals responses to sex. It is, however, plausible that this association is specific in healthy individuals as opposed to clinical populations. Although the predicted relation between intimacy, one of the core components of the attachment model, with sexual desire was confirmed, the hypothesized higher-level interaction effects of attachment orientation and intimacy on the association of stress with sexual desire were not found. Many speculative explanations can be proposed for this null finding. A methodology-based explanation pertains to the different ways in which the constituent elements were assessed. While stress, intimacy, and sexual desire were measured repeatedly with a high number of assessments of each participant, anxious and avoidant attachment were measured only once, which reduces the statistical power for this cross-level interaction. Moreover, intimacy, stress, and sexual desire were measured using the ESM methodology, whereas assessment of attachment orientation was based on a single questionnaire. A single measurement can provide only a snapshot of attachment responding and is not able to capture daily variation in attachment feelings and behavior. Measuring on the spot may be different from providing generalized responses over a longer period of time. Attachment emotions and behavior may vary across time (Verhees, Ceulemans, IJzendoorn, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, & Bosmans, Citation2019) and these variations might prove to have higher predictive power regarding intimacy.

The present study findings should be interpreted cautiously due to a number of limitations of the study. A first limitation of this study was that only one partner per couple was included, prohibiting the investigation of dynamic interaction patterns to which data of both partners of the couples contributed. Another limitation was the composition of the sample. As discontinuity may exist between healthy and dysfunctional individuals with regard to the associations between attachment-related variables and relational and sexual outcomes, this may have precluded findings the predicted relationships. We recommend that in future research in new samples data of both partners are included, allowing for analyses of both actor and partner effects, using actor-partner interdependence model analysis (Cook & Kenny, Citation2005), as well as both healthy and sexually and/or relationally dysfunctional individuals and couples. A third limitation was that our ESM-questionnaire did not ask for the object of sexual desire; whether the participant wanted sex with her or his own partner, with someone else, or wanted to masturbate. The desire to be sexual with one’s partner may be impacted by daily hassles and intimacy in a different way, compared with the desire for solitary sexual activity (see for an example: Raisanen et al., Citation2018). Another limitation pertains to the potential impact of children on the core concepts in this study. Unfortunately, we did not collect these data, but future studies should take this effect into account. A final but minor limitation involves the inclusion of both partners of one couple in our data set (see footnote in the Methods section).

In conclusion, the present study used an intensive longitudinal observations design, allowing for fine-grained analysis of participants’ reports of their momentary feelings, thoughts and observations, to test a theoretical model of sexual desire, including daily hassles-related stress, intimacy, and attachment orientation. An effect was found of emotional intimacy of participants on their level of sexual desire, but we failed to find the hypothesized effect of daily hassles on sexual desire. Both avoidant and anxious attachment did not predict sexual desire. Both attachment orientations also did not moderate the associations between stress, intimacy, and sexual desire. The results replicated findings from earlier research, testing predictions of the stress-regulation model of adult attachment with regard to sexual desire. However, previously untested predictions from the model, including the moderation by emotional intimacy of the association of daily hassles-related stress and sexual desire, and the moderation of the association between stress and sexual desire by the interaction of anxious attachment and intimacy, were not supported. Future research may serve to further test the implications of stress regulation and attachment for sexual functioning.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Although removing one partner of this couple would have been preferable, we were not able to do so due to the procedure that was used to secure participant anonymity. However, because different schedules were sent to partners prompting them to complete questionnaires, the influence of including both partners might have been limited.

References

- Abedi, P., Afrazeh, M., Javadifar, N., & Saki, A. (2015). The relation between stress and sexual function and satisfaction in reproductive-age women in Iran: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41, 384–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2014.915906

- Alonso-Arbiol, I., Balluerka, N., Shaver, P. R., & Gillath, O. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Spanish and American versions of the ECR Adult Attachment Questionnaire: A comparative study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 24, 9–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.24.1.9

- Avery-Clark, C. (1986). Sexual dysfunction and disorder patterns of working and nonworking wives. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 12, 93–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00926238608415398

- Basson, R. (2000). The female sexual response: A different model. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26, 51–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278641

- Basson, R. (2001). Using a different model for female sexual response to address women’s problematic low sexual desire. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 27, 395–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713846827

- Basson, R. (2002). Women’s sexual desire-disordered or misunderstood? Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 28(Suppl 1), 17–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230252851168

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4 Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Belsky, J. (1997). Attachment, mating, and parenting : An evolutionary interpretation. Human Nature, 8, 361–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02913039

- Belsky, J., Steinberg, L., & Draper, P. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: And evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62, 647–670. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1131166

- Birnbaum, G. E. (2010). Bound to interact: The divergent goals and complex interplay of attachment and sex within romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 245–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360902

- Birnbaum, G. E., & Reis, H. T. (2012). When does responsiveness pique sexual interest? Attachment and sexual desire in initial acquaintanceships. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 946–958. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212441028

- Birnbaum, G. E., Cohen, O., & Wertheimer, V. (2007). Is it all about intimacy? Age, menopausal status, and women’s sexuality. Personal Relationships, 14, 167–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00147.x

- Bodenmann, G., Ledermann, T., Blattner, D., & Galluzzo, C. (2006). Associations among everyday stress, critical life events, and sexual problems. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 494–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000228504.15569.b6

- Bodenmann, G., Pihet, S., & Kayser, K. (2006). The relationship between dyadic coping and marital quality: A 2-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 485–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.485

- Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030

- Brandão, T., Matias, M., Ferreira, T., Vieira, J., Schulz, M. S., & Matos, P. M. (2019). Attachment, emotion regulation, and well‐being in couples: Intrapersonal and interpersonal associations. Journal of Personality, 88, 748-761. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12523

- Brassard, A., Peloquin, K., Dupuy, E., Wright, J., & Shaver, P. R. (2012). Romantic attachment insecurity predicts sexual dissatisfaction in couples seeking marital therapy. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 38, 245–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.606881

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationship (pp. 46–76). New York: Guilford Press.

- Collip, D., Wigman, J. T., Myin-Germeys, I., Jacobs, N., Derom, C., Thiery, E., … van Os, J. (2013). From epidemiology to daily life: Linking daily life stress reactivity to persistence of psychotic experiences in a longitudinal general population study. PloS One, 8, e62688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062688

- Conradi, H. J., Gerlsma, C., van Duijn, M., & de Jonge, P. (2006). Internal and external validity of the experiences in close relationships questionnaire in an American and two Dutch samples. European Journal of Psychiatry, 20, 258–269.

- Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 101–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000405

- de Vries, M. W. (1992). The experience of psychopathology: Investigating mental disorders in their natural settings. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- DeHaas, E. C. (2015). Sexual satisfaction in newlywed couples: The role of attachment and sexual motivations. EBSCOhost psyh database. (75), ProQuest Information & Learning, US. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2015-99020-387&site=ehost-live

- Delespaul, P. A. E. G. (1995). Assessing schizophrenia in daily life: The experience sampling method. Maastricht, The Netherlands: Universitaire Pers Maastricht.

- Dewitte, M. (2012). Different perspectives on the sex-attachment link: Towards an emotion-motivational account. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 105–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.576351

- Dewitte, M., & Mayer, A. (2018). Exploring the link between daily relationship quality, sexual desire, and sexual activity in couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1675–1686. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1175-x

- Dewitte, M., van Lankveld, J., Vandenberghe, S., & Loeys, T. (2015). Sex in its daily relational context. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 2436–2450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.13050

- Dubé, J. P., Corsini-Munt, S., Muise, A., & Rosen, N. O. (2019). Emotion regulation in couples affected by female sexual interest/arousal disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48, 2491–2506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01465-4

- Favez, N., & Tissot, H. (2017). Attachment tendencies and sexual activities: The mediating role of representations of sex. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34, 732–752. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407516658361

- Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (2004). Attachment and sexuality in close relationships. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 183–201). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Hamilton, L. D., & Julian, A. M. (2014). The relationship between daily hassles and sexual function in men and women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40, 379–395. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2013.864364

- Hektner, J. M., Schmidt, J. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2007). Experience sampling method: Measuring the quality of everyday life. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Jacobs, N., Myin-Germeys, I., Derom, C., Delespaul, P., van Os, J., & Nicolson, N. A. (2007). A momentary assessment study of the relationship between affective and adrenocortical stress responses in daily life. Biological Psychology, 74, 60–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.07.002

- Jacobs, N., Nicolson, N. A., Derom, C., Delespaul, P., van Os, J., & Myin-Germeys, I. (2005). Electronic monitoring of salivary cortisol sampling compliance in daily life. Life Sciences, 76, 2431–2443. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.045

- Klusmann, D. (2002). Sexual motivation and the duration of partnership. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 275–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015205020769

- Lafit, G., Adolf, J., Dejonckheere, E., Myin-Germeys, I., Viechtbauer, W., & Ceulemans, E. (2020). Selection of the number of participants in intensive longitudinal studies: A user-friendly shiny app and tutorial to perform power analysis. Retrieved from https://psyarxiv.com/dq6ky/

- Levine, S. B. (1991). Psychological intimacy. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 17, 259–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239108404350

- Little, K. C., McNulty, J. K., & Russell, V. M. (2010). Sex buffers intimates against the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 484–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209352494

- Liu, C. (2003). Does quality of marital sex decline with duration? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 55–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021893329377

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1, 30–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

- Mehl, M. R., & Conner, T. S. (2012). Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York/London: Guilford.

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., Bar-On, N., & Ein-Dor, T. (2010). The pushes and pulls of close relationships: Attachment insecurities and relational ambivalence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 450–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017366

- Mizrahi, M., Reis, H. T., Maniaci, M. R., & Birnbaum, G. E. (2019). When insecurity dampens desire: Attachment anxiety in men amplifies the decline in sexual desire during the early years of romantic relationships. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 1223–1236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2567

- Morokoff, P. J., & Gillilland, R. (1993). Stress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 30, 43–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499309551677

- Muise, A. (2013). Where is the sex in relationship research? Relationship Research News, 12, 5–8.

- Murray, S. H., & Milhausen, R. R. (2012). Sexual desire and relationship duration in young men and women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 38, 28–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.569637

- Myin-Germeys, I., Oorschot, M., Collip, D., Lataster, J., Delespaul, P., & van Os, J. (2009). Experience sampling research in psychopathology: Opening the black box of daily life. Psychological Medicine, 39, 1533–1547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708004947

- Overall, N. C., & Lemay, E. P., Jr.(2015). Attachment and dyadic regulation processes. In J. A. Simpson, W. S. Rholes, J. A. Simpson, & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and research: New directions and emerging themes (pp. 145–169). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Pistole, M. C., Roberts, A., & Chapman, M. L. (2010). Attachment, relationship maintenance, and stress in long distance and geographically close romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 535–552. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510363427

- Prager, K. (1997). The psychology of intimacy. New York: Guilford.

- Prekatsounaki, S., Janssen, E., & Enzlin, P. (2019). In search of desire: The role of intimacy, celebrated otherness, and object-of-desire affirmation in sexual desire in women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45, 414-423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2018.1549633

- Raisanen, J. C., Chadwick, S. B., Michalak, N., & van Anders, S. M. (2018). Average associations between sexual desire, testosterone, and stress in women and men over time. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1613–1631. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1231-6

- Rick, J. L., Falconier, M. K., & Wittenborn, A. K. (2017). Emotion regulation dimensions and relationship satisfaction in clinical couples. Personal Relationships, 24, 790–803. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12213

- R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/

- Rubin, H., & Campbell, L. (2012). Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction: A dyadic diary analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 224–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611416520

- Shrier, L. A., & Blood, E. A. (2016). Momentary desire for sexual intercourse and momentary emotional intimacy associated with perceived relationship quality and physical intimacy in heterosexual emerging adult couples. Journal of Sex Research, 53, 968–978. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1092104

- Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2010). When are sexual difficulties distressing for women? The selective protective value of intimate relationships. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 3683–3694. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01958.x

- Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93, 119–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.119

- Vaessen, T., van Nierop, M., Reininghaus, U., & Myin-Germeys, I. (2015). Stress assessment using experience sampling: Convergent validity and clinical relevance. Stress Self-assessment & Questionnaires – Choice, application, limits, 21–35. Retrieved from http//hayka-kultura.org/larsen.html

- van Lankveld, J., Jacobs, N., Thewissen, V., Dewitte, M., & Verboon, P. (2018). The associations of intimacy and sexuality in daily life: Temporal dynamics and gender effects within romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35, 557–576. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517743076

- Verhees, M. W. F. T., Ceulemans, E., IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J., & Bosmans, G. (2019). State attachment variability across distressing situations in middle childhood. Social Development, 29, 196-216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12394

- Wagner, S. A., Mattson, R. E., Davila, J., Johnson, M. D., & Cameron, N. M. (2020). Touch me just enough: The intersection of adult attachment, intimate touch, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37, 1945–1967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520910791

- Wright, A. G., Aslinger, E. N., Bellamy, B., Edershile, E. A., & Woods, W. C. (2019). Daily stress and hassles. In K. Harkness & E. Hayden (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of stress and mental health (p. 27). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Yoo, H., Bartle-Haring, S., Day, R. D., & Gangamma, R. (2014). Couple communication, emotional and sexual intimacy, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40, 275–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2012.751072