Abstract

A systematic review and thematic synthesis were conducted on the motivations, purposes, and influence of pornography use among women who are in committed relationships. Pornography use was identified as having both positive and negative outcomes for women’s sexual and relationship lives. Women watched pornography for diverse reasons: to feel sexually empowered, to enhance sexual arousal, and for masturbation purposes. Shared use of pornography with partners provided variety in sexual activities, could aid communication about sexual issues and helped improve intimacy. Pornography use can help some women feel sexually empowered, relaxed and better able to enjoy their sexual lives.

Introduction

Whilst much research has focused on men’s experiences with pornography, relatively little attention has been given to women’s experiences (Ashton, McDonald, & Kirkman, Citation2018; McCutcheon & Bishop, Citation2015). When women’s pornography use is studied, researchers usually focus on sexual risks and sexual difficulties (McCutcheon & Bishop, Citation2015), or on women’s reactions/perceptions to their male partner’s pornography use (Bergner & Bridges, Citation2002; Bridges, Bergner, & Hesson-McInnis, Citation2003; Cavaglion & Rashty, Citation2010; Johnson, Ezzell, Bridges, & Sun, Citation2019). Researchers seldom study women’s sexual pleasure linked with pornography use (Ashton, McDonald, & Kirkman, Citation2019).

Pornography research to date

Below, we provide a background review of the quantitative research to date followed by consideration of qualitative studies on women’s experiences of pornography use.

Quantitative research

In a survey of Swedish students between 17 and 21 years old, Häggström-Nordin, Hanson, and Tydén (Citation2005) found that women, 45% of whom had a steady partner, were less likely than men to take the initiative in watching pornography and also less likely to report feeling aroused by watching pornography. Hald and Malamuth (Citation2008) used the Pornography Consumption Effect Scale in a representative Danish sample aged between 18 and 30 years and found that more men (97.8%) than women (79.5%) reported having ever watched pornography. Men also reported spending more time on average per week viewing pornography than women did. Women who accessed pornography regularly reported more positive effects of pornography consumption on their sex life, life in general and attitudes toward sex, compared with those who did not access it regularly. Curiosity, sexual arousal and the need to obtain sexual information were cited as the most common reasons for watching pornography by girls aged between 11 and 17 years old in a cross-sectional study conducted in the Czech Republic (Ševčíková & Daneback, Citation2014). No differences were found across different ages regarding participants’ stated reasons for watching pornography.

In a computer-assisted telephone survey involving a representative Australian sample of 16 to 69 year-old men and women, fewer women than men reported watching pornography (Rissel et al., Citation2017). For women under 20 or over 60 years old, self-reported factors that increased the likelihood of ever having viewed pornography were: identifying as lesbian or bisexual, having post high school education, having one or more sexual partners in the past year, masturbating in the past year, having had vaginal intercourse before the age of 16, having had heterosexual anal intercourse, drinking above the national guidelines for alcohol consumption and reporting elevated psychological distress. Among women over 30, ever having watched pornography was significantly associated with masturbating in the past year and ever having anal intercourse. Having a religion or faith was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of ever having looked at pornography. Rissel et al. (Citation2017) also assessed the factors predicting pornography use during the previous 12 months for women over 30. Women were less likely to have used pornography if they were living in a rural area, if they had a religion or faith, or if they were living with a partner. Women over 30 were more likely to have had viewed pornography if they identified as lesbian or bisexual, if they had post high school education, if they did not live with a regular partner, if they had one or more sexual partners in the past year, if they had masturbated during the past year, if they had vaginal intercourse before the age of 16 and, finally, if they had ever had anal intercourse. No differences were found in the factors predicting solo and partnered viewing.

The quantitative research to date in this area has some significant limitations. In most of the studies no definition of pornography was provided to the participants, so it was not possible for the researchers to know what the participants had in their minds when completing questions. Participants are usually provided with only limited options of possible responses, which may not be compatible with their (possibly complex) opinions and reactions. Also, there are social desirability factors that may encourage specific answers (Fisher & Katz, Citation2000; Krumpal, Citation2013); for example, women tend to report lower, and men higher, pornography use than their actual use (Carroll, Busby, Willoughby, & Brown, Citation2017).

Qualitative research

Qualitative research indicates that sexually explicit material is experienced and understood in different ways by women and men (Attwood, Citation2005). In one in-depth interview U.S. study, for example, young women (mean age 21 years) stated that they were more likely to view pornography when in a relationship, while young men (mean age 23 years) were more likely to view pornography while not in a relationship (Smith, Citation2013). Distinctions between watching solo and with partners, as well as watching secretly while in a relationship, were not explored.

There has been some limited qualitative research that has focused on women’s reactions to pornography use and how it might be associated with their sexual pleasure. Ashton et al. (Citation2019) conducted interviews with young heterosexual Australian women (18 − 30 years old). Women reported that pornography had both an enhancing and a diminishing influence on sexual pleasure. Pornography was described as enhancing their sexual pleasure when viewing with sexual partners, when learning about sexual preferences, and by providing reassurance about body appearance. At the same time, pornography was reported by the same women as diminishing sexual pleasure by misrepresenting bodies, sexual acts and expressions of pleasure, by causing concerns about the actors’ wellbeing and finally, by disrupting intimacy.

Similar results were reported by Davis, Temple-Smith, Carrotte, Hellard, and Lim (Citation2019) who identified themes in the responses of Australian women (15 − 29 years old) about the way pornography had influenced their lives. Two themes were reported: exploration and harm. Exploration covered safety, independence, normalization of sexuality and diversity in body type. Harm covered conditioning, comparison and dependency of viewing pornography. Even though women’s opinions about pornography are varied, and although pornography remains primarily men’s area of interest according to societal views, research reveals that some women do enjoy watching pornography (Ciclitira, Citation2004).

Participants in a focus group study involving U.S. young women (14 − 17 years old), tended to report that they found pornographic sites to be repulsive and they expressed concern that they were offensive to women (Cameron et al., Citation2005). The majority said they did not watch pornography intentionally and, if they did, it did not affect their personal views about their sexuality.

Some qualitative research has focused on reported motivations and reasons for pornography use. Parvez (Citation2006) conducted in-depth interviews with 30 self-identified heterosexual U.S. women (18 − 40 years); they reported that they enjoyed watching heterosexual pornography both by themselves and/or with their partners and reasons for use were to get sexually aroused, to masturbate, because of curiosity about sexual practices, because they wanted to improve their sexual practices in their relationships and as a means of rebellion against being considered “such a good girl” (Parvez, Citation2006, p. 616). Even though the context of pornography watching was mentioned, no different functions were reported for solo use versus partnered pornography use.

In an interview and focus group study of young Swedish women (14 to 20 years old), participants said that they used pornography as a way to socially interact with peers (as a way to test each other’s reactions to the actors’ and actresses’ behaviors and appearances), as a way to become sexually aroused and as a source of education (Löfgren-Mårtenson & Månsson, Citation2010). Similarly, Hare, Gahagan, Jackson, and Steenbeek (Citation2014) conducted semi-structured interviews with young Canadian women (19 to 29 years old). Participants reported watching pornography for diverse reasons, including entertainment, curiosity, as a self-arousal activity and to masturbate, as an arousing activity with partners, as a means to learn how to perform certain sexual acts, to learn more information about a type of sexual act they were not very familiar with, as an inspiration for sexual acts in offline sexual activities, as a way to check if a sexual interest/desire is “normal”, as a means to get sexual health information and as a way to fulfill fantasies.

In a systematic review of qualitative research regarding women’s experiences of pornography, Ashton et al. (Citation2018) concluded that women mainly used pornography to become aroused and to obtain information about sex. Women came across pornography in a social setting, in their relationships or by accident. Women carried internalized social messages about pornography (for example, that society deemed pornography unacceptable for women and that women are supposed to be less sexual than men), ethical values and personal experiences; all these played a role in the way they made sense of pornography. McCutcheon and Bishop (Citation2015) conducted interviews with Canadian women (18- 32 years) who identified as bisexual, heterosexual or lesbian. Across different sexual orientations, women reported that they watched gay pornography as a way of exploration, because they preferred same-sex pornography and because there was no objectification of women in this type of material (McCutcheon & Bishop, Citation2015).

Some women choose to watch pornography as a leisure activity (Benjamin & Tlusten, Citation2010) and they report that closeness to their partners is not affected (Popović, Citation2011). In the Popović (Citation2011) study, however, there was no information on whether women watched pornography alone or with their partners.

Reports from (Ramlagun, Citation2012) and from Rothman, Kaczmarsky, Burke, Jansen, and Baughman (Citation2015) indicate that some young women use pornography as an educational tool in order to obtain information about how to have sex. Smith (Citation2013) conducted semi-structured interviews with U.S. women (18 to 32 years) who reported that they used pornography as a source of sexual information and education. In other studies, young women understood that what is depicted in pornography is not real but nevertheless they used pornography as an educational tool (Döring, Citation2009; Mattebo, Larsson, Tydén, Olsson, & Haggström-Nordin, Citation2012; Rothman et al., Citation2015; Wang & Davidson, Citation2006).

The need for an up to date systematic review

There have been many studies on perceptions and reactions to pornography among young women and men (Löfgren-Mårtenson & Månsson, Citation2010; Mattebo et al., Citation2012; Secvlikova, Simon, Daneback, & Kvapilik, Citation2015). There has been less research on how adult women (18 years old and above) watch and experience pornography (Ashton et al., Citation2019; Ashton, McDonald, & Kirkman, Citation2020; McKeown, Parry, & Light, Citation2018). There have also been few systematic reviews (SRs) regarding the use of pornography in general, fewer on women and fewer still on women in committed relationships.

A Google Scholar search on pornography use and SRs (search words: pornography systematic review) conducted on October 15, 2019, in which the first 10 pages of results were checked, brought up 12 SRs on the use of pornography. Results after the first 10 pages were either irrelevant, not about women or not SRs; thus, they were not checked. Of the 12 SRs, three were specifically about men (Infante, Citation2018; Mellor & Duff, Citation2019; Sniewski, Farvid, & Carter, Citation2018), eight were about women and men (Alexandraki, Stavropoulos, Anderson, Latifi, & Gomez, Citation2018; De Alarcon, De La Iglesia, Casado, & Montejo, Citation2019; Duffy, Dawson, & Das Nair, Citation2016; Grubbs, Perry, Wilt, & Reid, Citation2019; Grubbs, Wright, Braden, Wilt, & Kraus, Citation2019; Harkness, Mullan, & Blaszczynski, Citation2015; Peter & Valkenburg, Citation2016; Short, Black, Smith, Wetterneck, & Wells, Citation2012) and only one of them was specifically about women (Ashton et al., Citation2018). Ashton et al. (Citation2018) reviewed qualitative research from 1999 to 2015, focused on understanding women’s experiences with pornography, no matter what their relationship status. Another Google Scholar search about sexually explicit material and systematic reviews (search words: sexually explicit material and systematic review) conducted on October 30, 2019, did not identify any additional SRs beyond those listed above.

Although research aiming to understand women’s perceptions of pornography has increased recently (Ashton et al., Citation2018), many unanswered questions remain. For example, why do women decide to watch pornography and what functions does pornography serve for them? Another important question is whether women feel more or less comfortable with their bodies and with their own sexual pleasure as a result of viewing pornography (McKeown et al., Citation2018). If women feel more comfortable with their bodies, are they better able to tell their partners what they want in order to share greater pleasure with them? One more interesting question to explore is whether women’s experiences of pornography differ when they watch by themselves or with their partners (Maddox, Rhoades, & Markman, Citation2011).

Systematic review objectives

The aims of this SR were to explore the associations between pornography and motivations women provide for watching pornography, what functions they feel pornography serves for them and how they believe pornography influences them. It was expected that, for women in committed relationships, pornography use would have different ramifications than it would have for single women. Other objectives were to explore if and how pornography plays a role in women’s sexual and relationship lives, either positive or negative, while in committed relationships, bearing in mind that there are many different genres and styles of pornography and that it is likely these appeal differently to different women (Maas et al., Citation2019). Lastly, it was also investigated whether, for women in committed relationships, pornography had any apparent influence on their own sexual satisfaction in their relationships and on their ability to communicate with their partners about sexual likes/dislikes.

The over-arching research question for this SR was: What are the reported motivations for, functions of and possible influenceFootnote1 of pornography for women when they are in committed relationships?

This question was broad enough to capture findings about women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, relationship satisfaction and sexual arousal, as well as other potential aspects of pornography use. The aim was to capture all contexts of pornography use, whether women watched pornography by themselves and/or with their partners while being in a committed relationship. In addition, “relationships” were not defined, as the aim was to capture any kind of relationships, heterosexual and same sex, as long as they involved consenting adults. A systematic review and a thematic synthesis were conducted to investigate the questions above.

Method

A mixed-methods SR was deemed appropriate as both qualitative and quantitative research could potentially provide answers relevant to the research question. A thematic synthesis was conducted as it allows for the combination of findings from research that uses different methods (Soilemezi & Linceviciute, Citation2018; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Thematic synthesis is a method that involves the systematic coding of qualitative data and the generation of descriptive and analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008).

Definitions

For this SR the term pornography was defined in a way that is commonly used by pornography researchers: “pornography or sexually explicit material (SEM) is any kind of material intended to create or enhance sexual feelings or thoughts in the recipient and at the same time containing explicit exposure and/or descriptions of genitals and sexual acts” (Hald & Malamuth, Citation2008, p. 616). Throughout this SR the terms pornography and sexually explicit material are used interchangeably. Regarding the ‘use’ of pornography the words: use, watch, consume, view, engage, expose to and access are also used interchangeably.

Types of studies included

Any peer-reviewed published articles, utilizing any type of qualitative and/or quantitative methodology that offered original data about the use of pornography.

Unpublished PhD theses.

Studies had to include participants who were in committed relationships. In addition, all published articles had to be in English language journals and have been published prior to July 2020. There was no specific start date in order to maximize potential inclusions.

Types of studies excluded

Review articles (although these were used to identify relevant studies).

Studies where the use of pornography by participants was not the main focus of the research but pornography was used as a tool for research; for example, psychophysiological studies using pornography to measure physiological arousal.

Studies about pornography production.

In addition, articles and PhD theses not in English and books, book chapters and any other type of unpublished material were excluded, as they are usually not peer reviewed.

Types of participants recruited in the included studies

Studies which involved individuals who identified as women, were consumers of pornography and were currently in committed relationships, were included. Committed relationships were either mentioned as such in the included papers or were at least six months long. Initially, the intention was to include only studies where the participants were in relationships of at least six months’ duration, but this criterion was revised at the end of the SR searches as many articles did not report the actual relationship duration of their participants. Thus, it was decided before final decisions about paper inclusions were made that the six-month duration criterion would not be retained, and studies were included if it was clearly stated that relationships were committed. There were no restrictions regarding women’s sexual orientation.

Search strategy

Database searches were carried out on four databases: PsychINFO, Web of Science, Medline and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. These were chosen because they incorporate psychology, social sciences, life sciences and related disciplines. Additionally, the reference lists of included articles were checked as a way to identify any relevant studies not obtained elsewhere.

Some gray literature was explored as well with the specific goal to identify unpublished PhD dissertations. Including unpublished dissertations helped reduce publication bias as usually negative results are not published (Aromataris & Pearson, Citation2014; Butler, Hall, & Copnell, Citation2016). To obtain gray literature ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global were searched.

The search terms used for the searches were chosen based on similar previous research carried out in this field. A librarian with expertise in psychology research and in conducting SRs was also consulted. Search strategies with explanations are presented below and in . All searches were conducted on February 18, 2020.

Table 1. Search strategy for databases.

PsychINFO via EBSCO was searched in advanced mode, narrowed by English. The key terms were searched under the default field, which looks for abstracts, authors, subject headings, titles and keywords. After the search was run, results were narrowed to academic journals and dissertations.

Medline via EBSCO was searched in advanced mode, narrowed by English. The key terms were searched under the default field, which searches abstracts, authors, subject headings, titles and keywords. After the search was run, results were narrowed by academic journals.

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global was searched in advanced search, narrowed by doctoral dissertations and English language. The key terms were searched under abstracts (AB) as the default field revealed too many results (19,136 articles when searching under default field).

Web of Science was searched in basic mode. Key terms were searched under the default field ‘Topic’ which looks for titles, abstracts and author keywords. As this database has slightly different rules for truncation, the search strategy was slightly modified: specifically, wom?n* was changed to wom?n, and wi?e* was changed to wife* OR wive*.

Selection of studies

All results from all the searches were exported to the reference manager software EndNote. Duplicates were removed via EndNote automated removal as well as via further manual removal and the number of duplicates was recorded. Following this, an Excel spreadsheet was created containing the following specific information from all the articles:

A reference number, unique to each article, assigned by the first author

Authors’ names

Year of publication

Title of the article

Journal where the paper was published

Journal volume, issue and page range of the article

DOI number of the paper

Abstract of the paper

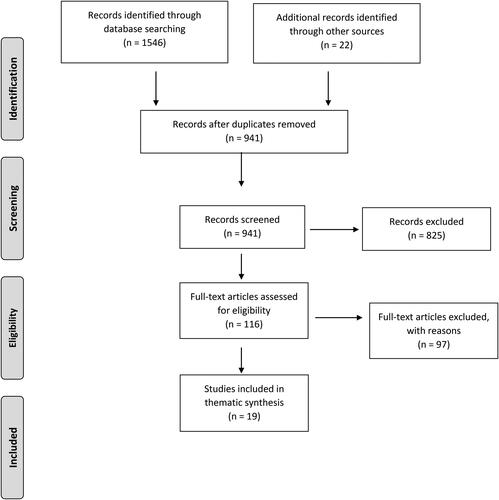

All articles that were identified from the searches were title-and abstract-screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The reference lists of existing SRs were searched and authors in the field were contacted but this process did not bring up any papers that were subsequently included. The first author screened the articles by title and abstract and made decisions about inclusions and exclusions. Papers for which a decision could not be made by the title and abstract screening were read in full. Following this, a list of eligible papers was constructed by the first author. Then, the first author and a second rater, another PhD researcher in the sexual health area, independently read in full all the eligible papers. Following this, the two raters liaised until they reached agreement about which articles were to be included/excluded. Articles that did not fit the inclusion criteria were excluded from further analysis. Following this, the final list of included papers was produced. The selection process is presented in a PRISMA flowchart (Moher, Liberati, Tezlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, 2009) (see ).

Quality assessment

The included articles were then read in full and were assessed by the first author using a quality assessment tool. Quality assessment of studies is considered essential in order to determine whether the studies have been conducted and reported in a reliable way and whether the reported results are relevant to the SR question (Boland, Cherry, & Dickson, Citation2017; Butler et al., Citation2016), to demonstrate the influence of each paper’s quality on the results, and to reduce possible researcher bias (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006; Dixon-Woods, Shaw, Agarwal, & Smith, Citation2004; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). There is some debate whether or not poor quality research should be excluded from SRs (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006). As the purpose of this SR was to provide an overview of the existing research rather than influence policy or construct a theory, all the papers were included, no matter what their quality ratings were (Aromataris & Pearson, Citation2014; Butler et al., Citation2016).

A standardized tool, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT, version 18) (Hong et al., Citation2018) was used to assess the included studies for methodological strengths and limitations. This tool was chosen because it was designed for mixed-methods systematic reviews, allows the use of one tool for concomitantly appraising the most common types of empirical studies, and shows good evidence of validity and reliability (Hong et al., Citation2018). In addition, it has been already widely used in other mixed-methods systematic reviews (Lawn et al., Citation2020; Stretton, Cochrane, & Narayan, Citation2018; Tyler, Wright, & Waring, Citation2019). The quality assessment of the included papers was based on the report of the results in published papers rather than on the actual research conducted. After completing two screening questions regarding the research questions and the data collected, each of the included papers was rated according to the appropriate category of criteria as “yes”, “no” or “can’t tell” (Hong et al., Citation2018). Calculation of an overall score on the MMAT is discouraged as it is not informative (Hong et al., Citation2018). Instead, it is recommended that the ratings of each of the criteria for every included study are presented in a table.

The second rater also assessed three of the included articles in order to minimize potential for errors and reduce researcher bias (Soilemezi & Linceviciute, Citation2018). Inter-rater reliability between the two raters according to Cohen’s kappa (McHugh, Citation2012) was almost perfect (90%).

Thematic synthesis

Synthesizing research can combine data from different contexts, generate new models, identify gaps in research, help develop primary studies and help structure health interventions (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, Citation2012). There is no universally accepted method to use for synthesizing qualitative and quantitative data (Boland et al., Citation2017).

Thematic synthesis (TS) was deemed appropriate for four reasons: (1) because it allows for the combination of findings from research that uses different methods (Soilemezi & Linceviciute, Citation2018; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008), (2) because it uses specific step by step methods for the analysis of primary data, (3) because it allows the researcher to stay close to the original qualitative data, synthesizing them and in this way producing new themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008), and (4) because it is suitable for SRs that present people’s views, perspectives and experiences (Boland et al., Citation2017; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Usually TS is used to synthesize qualitative data but there are also mixed methods SRs that have used TS (Baxter, Blank, Guillaume, Squires, & Payne, Citation2011; Bray, Noyes, Edwards, & Harris, Citation2014; Fletcher et al., Citation2016; Joseph-Williams, Elwyn, & Edwards, Citation2014; Schloemer & Schröder-Bäck, Citation2018; Wang & Yeh, Citation2012).

In order to conduct the TS, all the included papers were gathered but, following TS guidelines, only the results or findings sections were coded (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Initially line by line coding of the primary and the secondary data was undertaken, so that each line had at least one code assigned to it (Nicholson, Murphy, Larkin, Normand, & Guerin, Citation2016; Ryan et al., Citation2018; Smith, Kolokotroni, & Turner-Moore, Citation2020; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). For qualitative studies, primary data are the participants’ quotes and secondary data are the authors’ interpretations (Smith et al., Citation2020; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008; Toye et al., Citation2014). For quantitative studies, the results or findings sections were considered as primary and secondary data. Coding was undertaken using the results sections of the included papers, looking for anything that appeared relevant to the SR’s research question. With the quantitative papers, usually a self-completed survey or a questionnaire was used; thus, the results were based on the women’s reports. Regarding the qualitative papers, the data were based on what the women themselves had reported. Sections where either men’s use of pornography was discussed and/or where women’s use of pornography was discussed but they were not in committed relationships were not coded. With every new paper that was coded, new codes were added to the “bank” of codes. During this process not only were new codes added, but also there was a constant “back and forth” review of the included papers, checking if the new codes appeared in the papers that had already been analyzed.

This process created 18 sub-themes. In the second step, all these initial sub-themes were examined for similarities and differences. These were organized into a total of three descriptive themes, each including some of the sub-themes, reflecting the original content of the data and organized into meaningful categories (Nicholson et al., Citation2016; Ryan et al., Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2020; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008).

Thus far, the analysis was close to the original studies and all the themes came directly from the initial papers. There was no attempt to address the main question of this SR or go beyond the original data. The third step was about doing that. This is the attempt to answer the SR question by using the descriptive themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The descriptive themes which resulted from the inductive analysis of the included papers were used to push the analysis to “go further” than the content of the included papers in order to create higher-level themes (Nicholson et al., Citation2016; Ryan et al., Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2020; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) and offer a new interpretation that went beyond the primary studies (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008; Tong et al., Citation2012). In other words, the findings from the included papers were combined to answer the SR question: what are the reported motivations for, functions of and possible influence of pornography for women when they are in committed relationships?

Through this process, four analytical themes were identified.

The NVivo 12 software was used throughout the analysis process in order to facilitate coding and organizing the results. NVivo is a qualitative data analysis software designed to help with organizing and analyzing qualitative data (NVivo, Citation2021). Data analysis was primarily conducted by the first author and each step of the analysis was discussed in meetings with the coauthors.

Results

The initial search identified 1546 articles. After deleting duplicates, screening of titles and abstracts and full text reading of the ambiguous ones, 17 articles and two PhD theses were included in this mixed methods SRFootnote2. One of the included papers was based on one of the PhD theses, using the same data set. Both the thesis and the journal paper were included as they investigated different hypotheses. Of the studies, four were qualitative and 15 were quantitative. Two of the studies were conducted in Australia, one in Israel, 13 in the USA, two in Canada and one was an online survey, with country of residence for participants not specified but they were most likely from Canada and the USA. All four qualitative studies used interviews. All the quantitative studies used surveys – online, telephone, or in-person. The studies were published between 2007 and May 2020.

Additional details about the characteristics of the included articles are shown in .

Table 2. Characteristics of included papers.

Quality assessment

The results of the quality assessment conducted with the MMAT (Hong et al., Citation2018) are presented in . All 19 included papers had a “yes” response to the two initial screening questions: “Are there clear research questions?” and “Do the collected data allow to address the research questions?”. In addition, the design and the ratings of the studies reported in the included papers (qualitative, quantitative descriptive, or quantitative non-randomizedFootnote3) is provided in .

Table 3. Quality evaluation of included studies using the mixed methods appraisal tool by Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018).

Almost all of the included papers were scored a “yes” for the majority of the quality assessment questions and a “can’t tell” rating to the question “is the risk of nonresponse bias low” for 10 of the quantitative descriptive papers and a “can’t tell” to the question “are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis” for one quantitative non-randomized paper. These data indicate that the quality of the included studies was relatively high. The aims of the studies, the methods used, and the type of analysis were clearly reported in all the included articles. The age range of the women participants varied from 18 to 80. In the three studies which provided longitudinal data from women, participants were as old as 80 years old (Perry, Citation2017; Perry & Davis, Citation2017; Perry & Schleifer, Citation2018).

A definition of pornography or sexually explicit material (SEM) was provided in 11 of the papers, whereas in eight no definition was provided (Brown et al., Citation2017; Daspe, Vaillancourt-Morel, Lussier, Sabourin, & Ferron, Citation2018; Dellner, 2008; Perry, Citation2020; Perry & Schleifer, Citation2018; Poulsen, Busby, & Galovan, Citation2013; Willoughby, Carroll, Busby, & Brown, Citation2016; Willoughby & Leonhardt, Citation2020).

Relationship length was relevant to this SR as papers were included only if women were in committed relationships. There was no definition in any of the included papers of how long a relationship should be in order to be regarded “committed”. Relationship length was not reported in several of the papers (Ashton et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Carroll et al., Citation2017; Leonhardt & Willoughby, Citation2019; McKeown et al., Citation2018; Perry, Citation2017, Citation2020; Perry & Davis, Citation2017; Perry & Schleifer, Citation2018; Poulsen et al., Citation2013). Only one paper specifically stated that participants had to have been in a committed relationship for six months or longer to take part (Dellner, 2008).

In addition, the constructs that were being measured were only defined in one of the articles (Leonhardt & Willoughby, Citation2019). Usually a specific scale was used to measure a construct, (for example, sexual satisfaction or relationship satisfaction), but the precise definitions of the constructs these measures assessed were not provided.

Thematic synthesis

As mentioned in the method section, the 18 sub-themes were organized into a total of three descriptive themes, each including some of the sub-themes:

Theme One: How pornography can bring changes to relationships: Sexual Satisfaction, Relationship Satisfaction, Sexual Desire, Intimacy, Dyadic Satisfaction, Marital Quality, Sexual Quality, Pleasure Changes Over Time.

Theme Two: Pornography usage: Porn Use Frequency, Content of Sexual Media, Shared Use, Reasons for Porn Use, Porn Use & Demographic Variables.

Theme Three: Negative outcomes from using pornography: Porn Use & Separation, Porn Disrupting Pleasure, Pornography Acceptance – Porn as Infidelity, Lack of Control, Unrealistic Expectations.

Then, as was described above, these descriptive themes that came from the included papers were combined to answer the SR question and four analytical themes were created.

Porn use enhances – plays a positive role in women's sexual and relationship lives while in committed relationships.

Porn use disrupts – plays a negative role in women’s sexual and relationship lives while in committed relationships.

Shared Use.

Reasons for Porn Use.

The articles linked to these themes and sub-themes are presented in . The analytical themes are presented below along with some illustrative quotes.

Table 4. Sources of Themes .

Porn use enhances – plays a positive role in women's sexual and relationship lives Footnote4 while in committed relationships. This theme is about how pornography use plays a positive role in women’s sexual and relationship lives, whether they watch it with or without their partners. This theme was derived only from quantitative papers, as it was not evident in any of the qualitative studies, and consists of these sub-themes: Sexual Satisfaction, Relationship Satisfaction, Sexual Desire, Marital Quality, Sexual Quality.

Sexual satisfaction was the most frequently mentioned sub-theme in the papers. A validated sexual satisfaction questionnaireFootnote5 was usually used (Bridges, 2007; Bridges & Morokoff, Citation2011; Brown et al., Citation2017; Daspe et al., Citation2018; Dellner, 2008; Leonhardt & Willoughby, Citation2019; Willoughby & Leonhardt, Citation2020). Studies reported that the woman’s own pornography use, either by herself and/or with her partner (it did not matter if the partner knew about women’s pornography use or not), was significantly associated with higher reported levels of sexual satisfaction (Bridges, 2007; Bridges & Morokoff, Citation2011; Willoughby & Leonhardt, Citation2020).

Relationship satisfaction was the second most mentioned sub-theme in all of the quantitative papers; again, this was measured by validated questionnaires (Bridges, 2007; Bridges & Morokoff, Citation2011; Daspe et al., Citation2018; Dellner, 2008; Poulsen et al., Citation2013; Resch & Alderson, Citation2014). Studies reported that the woman’s personal pornography use, either on her own or with the partner or both, was positively associated with relationship satisfaction:

Specifically, the woman's own use of sexually explicit material was positively related to sexual and relationship satisfaction (Bridges, 2007, p. 65).

Sexual desire was also mentioned only in the quantitative papers (Bridges, 2007; Willoughby & Leonhardt, Citation2020). It was found that the consumption of pornography by women was associated with higher sexual desire:

Women’s pornography use was associated with significantly higher female sexual desire (Willoughby & Leonhardt, Citation2020, p. 83).

Marital quality was mentioned in one of the papers which reported on quantitative longitudinal data (Perry, Citation2017). For those women in relationships who reported watching pornography more than once a month at the time of the first survey, their marital quality had increased by the time of the second survey:

Viewing pornography would not be negatively associated with marital quality for women, but could in fact be positively associated with marital quality (Perry, Citation2017, p. 556).

Consumption of pornography was reported to play a positive role in women’s sexual quality as assessed by a two-item scale in a quantitative paper; sexual quality was not defined (Poulsen et al., Citation2013).

Porn use disrupts – plays a negative role in women’s sexual and relationship lives while in committed relationships. This theme is about how pornography use plays a negative role in women’s sexual and relationship lives, whether they watch it with or without their partners. This theme was derived from both qualitative and quantitative research and it includes these sub-themes: Sexual Satisfaction, Porn Use and Separation, Porn Disrupting Pleasure in Relationships, Intimacy, Pornography Acceptance/Porn as Infidelity, Lack of Control, Unrealistic Expectations.

Sexual satisfaction was the most common sub-theme assessed, but only in quantitative papers (Bridges, 2007; Bridges & Morokoff, Citation2011; Brown et al., Citation2017; Daspe et al., Citation2018; Dellner, 2008; Leonhardt & Willoughby, Citation2019; Willoughby & Leonhardt, Citation2020). These reported that women’s solo pornography use (it was not specifically mentioned whether partners knew about use or not), was negatively associated with their own sexual satisfaction:

Significant findings partially supported the second hypothesis that husbands’ and wives’ solo pornography use would negatively associate with sexual satisfaction. Wives’ pornography use was also negatively associated with their sexual satisfaction (Brown et al., Citation2017, p. 580).

Separating or breaking up with a committed partner was mentioned to be positively associated with pornography use by women in some of the quantitative articles (Perry, Citation2020; Perry & Davis, Citation2017; Perry & Schleifer, Citation2018):

The positive association between pornography use and repeatedly breaking up appeared to be stronger for women (Perry, Citation2020, p. 1210),

Among women, however, there is a negative association between discontinuing pornography use and divorce. Of those women who continue to watch porn during both survey waves, 18% are predicted to be divorced at Time 2, compared to only 6% of those who stopped viewing porn in between the two surveys. Overall, these figures suggest that women who watch pornography get divorced at higher rates than men (who watch pornography) (Perry & Schleifer, Citation2018, p. 290).

Pleasure was also reported as being disrupted in qualitative papers, because of the use of pornography by women, whether they were watching it by themselves or with their partners or both (Ashton et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). It was also noted in qualitative papers that women’s pleasure was never really emphasized in pornography and that was something that affected the way women communicated to partners about their sexual needs:

Chloe spoke of pornography as depicting men ‘always getting it right’; as a result, ‘there is never those conversations in porn’ about women’s pleasure. This had influenced her not to communicate her needs or desires to her sexual partners on the assumption that they would ‘take offence’ (Ashton et al., Citation2019, p. 422),

Pornography that was detrimental to the relationship, whether consumed by the women or their partners, was described by women as reducing their pleasure (Ashton et al., Citation2019, p. 424).

Another component of women’s sexual and relationship lives that appeared to be negatively associated with the consumption of pornography and was mentioned in quantitative papers was intimacy in committed relationships (Bridges, 2007). In one of the quantitative papers it was demonstrated that:

the more sexually explicit material a woman reported using herself, the lower she rated her level of intimacy in her romantic relationship (Bridges, 2007, p. 76).

Interestingly, it was mentioned in quantitative papers that women who were in committed relationships and were using pornography still thought that this was some form of infidelity, no matter whether their partner knew or not (Brown et al., Citation2017; Carroll et al., Citation2017):

Nearly one-third of engaged and married women report that they view pornography as a form of ‘marital infidelity’ (Carroll et al., Citation2017, p. 153).

Furthermore, pornography use by women was positively associated with perceived lack of control: in one quantitative paper, difficulty of controlling a strong urge and trouble stopping or decreasing pornography use was reported (Daspe et al., Citation2018).

Finally, as described in one qualitative paper, women reported that pornography use gave them unrealistic expectations regarding their sexual and relationship lives:

Samantha was disappointed following expectations engendered by pornography. Penetrative sex with her partner was not ‘amazing’, she did not ‘orgasm very quickly’ or find it ‘highly pleasurable’, and she and her partner did not reach orgasm simultaneously (Ashton et al., Citation2019, p. 421).

Real-life sexual experiences were not the same as depicted in pornography. Whether the type of pornography accessed played a role in women’s expectations was not discussed in any of the articles.

Shared use

This theme is about all aspects of shared use of pornography and how shared use works as a stimulus to communicate about sexual issues and to improve intimacy. There is some overlap with the previous two themes but this one is specifically about anything mentioned in regard to shared pornography use. This theme was identified only in qualitative research.

Many papers mentioned that women enjoyed watching pornography with their partners as it gave them ideas for new sexual activities that could lead to more sexual variety and sexual pleasure:

They and their sexual partners could use pornography to learn about and practice new sexual activities and to enhance shared pleasure (Ashton et al., Citation2019, p. 418),

Some people see pornography as only for men. NO! It’s for both men and women. In fact, pornography is primarily a masculine initiative since the man is the one who provides it. In my case, it was like that, however if there is intimacy there is an opportunity to enjoy it together. If you view pornography as something for both to enjoy, then there is something appealing in it that stimulates arousal (Benjamin & Tlusten, Citation2010, p. 614).

At the same time, however, it was also mentioned that sharing pornography use with a partner did not benefit women’s sexual life, as it could mean pressure for women to perform specific sexual acts they did not necessarily want to:

Although Chloe said she did not ‘necessarily have any problem with people, well, the people I have sex with watching porn’, she spoke of partners giving her ‘a one-size-fits-all kind of feeling’ and of their tendency to perform ‘scary’ acts, such as choking or anal penetration, that they had seen in pornography. At times she had felt ‘pressured’ to ‘go along with it’ and, because ‘there is almost never any negotiation in porn’, she felt that her pleasure was not considered and her relationships did not benefit (Ashton et al., Citation2020).

Shared pornography use by women and their partners was also mentioned as a tool to communicate about sexual issues and negotiate about sexual likes and dislikes:

Molly explained, I find it easier to negotiate sex in relationships if there’s someone else’s sex happening. I’d be like, that’d be too far for me by the way…it takes it away from my partner and puts it into something that’s separate from us so no one feels like they’re ruining it for the other person or something like that. Similarly, Sophia shared, ‘it’s just a lot easier to look at someone outside your relationship and say ‘see that person’s doing something I don’t think is attractive,’ instead of saying ‘you’re doing something.’ It’s a tool (McKeown et al., Citation2018, p. 348).

Finally, it was mentioned that shared pornography use improved intimacy in relationships:

We inferred from women’s accounts that a pleasurable experience of shared pornography viewing was more likely to occur in a relationship presented as respectful and communicative; viewing together was constructed as a contribution to intimacy. The women who described viewing with their male sexual partners narrated themselves as agents in the relationship: they experienced sexual intimacy as healthy, could critically assess what they saw in pornography, and could be selective about the role it played in partnered pleasure (Ashton et al., Citation2019, p. 419).

Reasons for porn use

This theme focuses on the reasons provided by women for watching pornography and appeared in both qualitative and quantitative research.

Several reasons were provided as to why women in committed relationships watched pornography, either by themselves or with their partners or both. Some women mentioned that they chose to watch pornography when their partners did not want to engage in sexual activity:

Female users stated that they used sexually explicit materials because their male partners did not want to be intimate as often as they did (Bridges & Morokoff, Citation2011, p. 573).

Other reasons that women reported for pornography use were to enhance masturbation and fantasizing (Bridges, 2007; Bridges & Morokoff, Citation2011) and to assist them in exploring their sexual selves while they were in committed relationships:

For example, many women spoke about how their consumption helped them to foster a sense of sexual independence because it was rooted in personal choice. Sara shared, ‘It’s something I want to do.’ Sophia also noted, ‘It’s just me time I guess.’ And Sophia spoke about how her consumption helped her feel empowered. She explained, it does make me feel empowered in the sense that I can access these things, I’m comfortable with them. I’m comfortable with my body. I’m doing it freely so the sexually explicit material that I consume now and have consumed for years has been independent. It’s been driven by my own preferences and choices and so I think that is nice particularly since I’ve been in relationships a lot of my 20s. So, having control over an aspect of your sexuality that is only for you and only yours (McKeown et al., Citation2018, p. 347),

Women also talked about how they consumed pornography in order to explore their own sexual interests and to gain a better understanding of their sexual selves:

As Nora shared, ‘it allows me to explore my own interests beyond a relationship, independently.’ She continued, ‘sexuality is something that’s core to everyone’s identity…That’s a large reason why I access those materials. It’s part of that expression and development of understanding myself.’ And ‘I want to have a safe space to explore my own interests without any judgment or my partner picking up on it and thinking that is what I want to pursue without me communicating it’ (McKeown et al., Citation2018, p. 347).

In summary, it appears that there are many different reasons for which women in committed relationships report using pornography.

Discussion

The aims of this SR were to explore what motivates women to watch pornography, what purposes/functions pornography serves for women and how women believe pornography influences their sexual and relationship lives. This is the first mixed methods SR on this topic. The focus in the review was on women in committed relationships as it was expected that pornography use would have different ramifications for them than for single women. This SR had a different focus than another recent qualitative SR that reviewed research involving women of any relationship status (single, in casual relationships, and in committed relationships) (Ashton et al., Citation2018); and it reviewed both qualitative and quantitative research.

Four analytical themes were identified in total, which were consistent with Ashton et al. (Citation2018) SR, but also extend our understanding about women’s pornography use. Two of the themes are overarching: Porn use Enhances (plays a positive role in) women's sexual and relationship lives, and Porn use Disrupts (plays a negative role in) women’s sexual and relationship lives. These reflect the fact that pornography use can have both positive and negative roles in women’s sexual and relationship lives.

The fact that women’s pornography use is complex is also apparent in the other two themes. The theme Reasons for Porn Use illustrates that there are many different reasons that women in committed relationships mention for using pornography e.g., to enhance masturbation and fantasizing, to explore their sexuality but also when there was incongruence between their own and their partners’ sexual needs. In the theme Shared Use, watching pornography with a committed partner had both positive and negative outcomes for women’s sexual and relationship lives; it could bring novelty to the relationship but could also mean pressure for women to perform specific sexual acts they might not have wanted to engage in.

Definitional issues in pornography research

In the included articles in this review, the terms pornography and sexually explicit material were used but they were not consistently defined and in only some of the included articles were definitions provided. Pornography research is fragmented when it comes to definitions (Ashton et al., Citation2018; Kohut et al., Citation2020; McKee, Byron, Litsou, & Ingham, Citation2020). Often, researchers use different terms for pornography, such as sexually explicit material, erotica, adult films, etc. (Ashton et al., Citation2018; Kohut et al., Citation2020). This problem becomes more evident if one looks at research carried out within different disciplines (McKee et al., Citation2020). McKee et al. (Citation2020) showed that researchers in disciplines such as history, cultural studies and literacy studies prefer to use different definitions for pornography than do researchers from psychology. This makes it challenging for researchers in the pornography area, as searching and finding all the relevant research is not straightforward (Kohut et al., Citation2020). Future research would benefit if pornography was more clearly and consistently defined.

Cultural issues in pornography research

The cultural context within which pornography is experienced by participants, and also the context in which research is conducted, play important roles in how research is reported in published articles (Ashton et al., Citation2018). The reviewed research was conducted in only four countries: Australia, USA, Canada and Israel. Three of these countries can be described as having a “Western” lifestyle and a “relaxed” approach when it comes to pornography use, in comparison to non-Western countries. Israel is an exception as it can be considered a mixture of Western and Eastern cultures. Some researchers described the cultural context of their research and made culture-specific observations (Benjamin & Tlusten, Citation2010), others mentioned the culture and the fact that they opted for a consistent cultural background (Ashton et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Leonhardt & Willoughby, Citation2019), and many did not mention the influence of the cultural context at all (Bridges, 2007; Bridges & Morokoff, Citation2011; Brown et al., Citation2017; Carroll et al., Citation2017; Daspe et al., Citation2018; Dellner, 2008; McKeown et al., Citation2018; Perry, Citation2017, Citation2020; Perry & Davis, Citation2017; Perry & Schleifer, Citation2018; Poulsen et al., Citation2013; Resch & Alderson, Citation2014; Willoughby et al., Citation2016; Willoughby & Leonhardt, Citation2020). The cultural contexts and, by extension, the cultural norms about pornography use women in committed relationships might have to deal with were not the focus of the analysis in any of the included papers. Cultural contexts and norms should be more fully addressed in future research on pornography use because pornography laws/policies vary markedly across different countries, as do levels of gender equality/inequality. As the included papers for this SR come from the four countries mentioned, the themes presented would have been shaped by the cultural contexts of these four countries.

Limitations and strengths of the SR

Due to the rapid changes in availability of sexually explicit material via smartphones (Spišák, Citation2016), new relevant articles published between July 2020 and the publication date of this SR will inevitably be missing from this SR. Also, as with every SR, it is possible that relevant articles have been missed because they did not appear in the searches, although guidance from a librarian and extensive database searches were utilized.

As mentioned in the Results section, relationship length was a problematic issue for this review; one of the inclusion criteria was that women had to be in committed relationships. However, in the included papers, relationship type and relationship length were not always clearly reported. Sometimes relationship length or type were not mentioned at all and sometimes the results were presented in such a way that there was no distinction between participants in committed and uncommitted relationships. Thus, there were a few papers that were initially considered borderline inclusions but in the end were not included in this SR because the authors did not clearly state which of the results referred to women in committed relationships and which referred to women not in committed relationships; for example, Borgogna, Lathan, and Mitchell (Citation2018); Cates (2015); Dwulit and Rzymski (Citation2019). For this SR that focused on women in committed relationships, papers were included when relationship length or relationship type were clearly stated - for example, married participants - or when the authors of the papers mentioned that participants reported that relationships were committed. It would be useful for future research to enquire about, and report, clearer information on relationship length and type, although defining whether a relationship is committed or not is a complex issue. It can depend on what the members of the relationship believe as well as the age of the people involved in the relationship – younger people are highly likely to interpret time involved in a relationship (and the term ‘commitment’) differently from older people. It would also be of interest to assess changing behaviors and attitudes as relationships develop over time.

Another issue worthy of mention is that some papers were not included in this SR because of other issues in how the results were presented; in particular, when it was hard to tell whether specific findings applied to men or women (e.g., Carmenate (Citation2018); Kohut, Fisher, and Campbell (Citation2017); Minarcik, Wetterneck, and Short (Citation2016); Staley and Prause (Citation2013)). In other cases, the authors may have been unable to analyze quantitative data for men and women separately due to small sample sizes. Because this SR focused only on data pertaining to women, articles that reported data for men and women collectively had to be excluded.

Regarding thematic synthesis, it was considered a useful method for this SR, in order to combine and synthesize all the existing research to date and produce analytical themes. However, some scholars have argued that by interpreting an interpretation, qualitative synthesis loses the essence of the original studies (Boland et al., Citation2017; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008; Toye et al., Citation2014).

The included papers did not address sexual wellbeing, a concept that has recently been gaining more attention from sex researchers (Finley, Citation2018; Kaestle & Evans, Citation2018; Kilimnik & Meston, Citation2018; Štulhofer, Bergeron, & Jurin, Citation2016; Štulhofer, Jurin, Graham, Enzlin, & Traeen, Citation2019). Sexual wellbeing refers to an individual’s subjective appraisal of their sexuality, the presence of pleasurable and satisfying experiences and the absence of sexual problems (Foster & Byers, Citation2013, p. 149; Laumann et al., Citation2006, p. 146). This is not necessarily a shortcoming of the included papers, but it rather shows that pornography research has as yet not focused on the broader topic of sexual wellbeing. Thus, further research on sexual wellbeing in relation to pornography exposure would be useful.

Furthermore, whether the partners of the women who were watching pornography knew about their use or not was not assessed or discussed in the included papers. Future pornography research should include this to enable assessment of whether (and how) this affects women’s reactions and their sexual and relationship lives.

This SR had some strengths. According to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first SR about pornography use by women who are in committed relationships that has been conducted; it helps shed new light on pornography use by women and to help to correct the historical gender imbalance. Also, it is the first relevant SR that incorporated both qualitative and quantitative research. Despite the few methodological issues with definitions of pornography and with how the types of relationships were defined, we endeavored to be as inclusive as possible in order to review all the relevant research. For example, we included PhD theses as a way to minimize publication bias, because PhD theses reporting negative findings are usually not published (Aromataris & Pearson, Citation2014). We also used a standardized quality assessment tool (Hong et al., Citation2018) and, as recommended (Higgins & Green, Citation2008), a second rater independently assessed the quality of a sub-sample of the included papers. Perhaps the key strength of this SR, however, has been to identify areas for further exploration in this important emerging field.

Implications of findings

The findings from this SR have implications for clinical practice. From a sexual health perspective, it is important to know whether women who watch pornography believe it increases (or decreases) their sexual satisfaction. Clinicians can use such knowledge to provide permission to women to watch pornography without feeling guilty or “abnormal”. According to the Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestion, Intensive Therapy (PLISSIT) model (Annon, Citation1976), people often need to be told by some sort of authority, such as a sexual health clinician, that their sexual thoughts and behavior are “normal”. When people engage in behavior they believe is immoral, such as watching pornography, they may interpret it as pathological and feel distressed about it (Droubay, Shafer, & Butters, Citation2020). Clinicians can provide limited information (Annon, Citation1976) to women about their sexual concerns, dispel sexual myths that clients might hold (Crooks & Baur, Citation2011; Lehmiller, Citation2014) and make them feel sexually empowered, relaxed and better able to enjoy their sex lives.

As suggested by Maddox et al. (Citation2011), pornography might also be used in clinical settings to help women who have sexual difficulties, such as sexual desire and sexual arousal disorders, to improve their sexual satisfaction and sexual intimacy (Crooks & Baur, Citation2011; Lehmiller, Citation2014). Couples facing sexual intimacy problems could also watch pornography as means to communicate about sexual likes and dislikes and to relax and enjoy sexual intimacy. Communication about sexual likes and dislikes is very important to all domains of sexual function (desire, arousal, erection, lubrication, orgasm) as well as overall sexual function (Mallory, Stanton, & Handy, Citation2019).

Understanding pornography consumption is also important because it might influence policy regarding pornography. According to some authors, women are expected to adopt a subservient “pleasing role” in their heterosexual intimate relationships, prioritizing male sexual pleasure (Ashton et al., Citation2019). Although it is expected that men watch pornography and talk openly about it, it is still considered unacceptable for women to do so (Ashton et al., Citation2018; Löfgren-Mårtenson & Månsson, Citation2010). It is important to understand more about the extent to which women still feel influenced by societal gendered norms around pornography (Ashton et al., Citation2018; Spišák, Citation2017), as this could help guide policy6 makers and others to work toward developing education and service provision policies that could minimize gender inequalities. It has been argued that national policies on pornography have an uneven impact on women as the burden has historically been placed on them regarding controlling their reproductive capacity to the relative detriment of their own pleasure (Fine & McClelland, Citation2006). Fine and McClelland (Citation2006) argued that women need to be provided with the opportunities to develop intellectually, emotionally, economically and culturally and to be able to see themselves as sexual beings capable of pleasure while simultaneously being aware of social, medical and reproductive risk. For these reasons, it is important to know whether watching pornography helps to challenge women’s traditional models of sexuality (Morrison & Tallack, Citation2005), encouraging gender equality policies and norms.

Understanding pornography use better can also inform relationships and sexual education (RSE) for children in schools. Multiple studies have reported that young people are regularly watching pornographic material at young ages; it would therefore be useful for educators to ensure that young people understand what they are watching is fantasy and not “real-life” sex (Smith, Citation2013). At the same time, however, young people need to be able to make informed decisions about their bodies and their sexual health (Fine & McClelland, Citation2006). It would be useful for parents and educators to consider whether they would want pornography to be their children’s main source of sexual education and, if not, what might be the alternatives. It is also necessary to address gender roles when discussing pornography in educational settings (Smith, Citation2013). Healthy sexuality requires education about how to achieve pleasure but at the same time requires education about sexual health risks and protection against coercion and violence (Fine & McClelland, Citation2006). Knowing women’s sexual likes and dislikes can help inform RSE programs, to focus more on sexual pleasure and how to achieve it, on sexual communication and on sexual consent issues rather than on risks and dangers of sex. Recently, there have been some calls for pornography literacy education; for example, Dawson, Nic Gabhainn, and MacNeela (Citation2020) conducted a study using participatory group activities with 18 to 29-year-olds in Ireland and reported that their participants thought that sex education should provide information on how to reduce shame when engaging with pornography and also improve their critical thinking skills regarding body image comparisons; sexual and gender-based violence; fetishizing of gay and transgender communities; and lastly, setting unrealistic standards for sex (Dawson et al., Citation2020). Comprehensive RSE can help women feel empowered and make safer sexual health choices.

Conclusions

We reviewed the existing research, both qualitative and quantitative, on women’s pornography use while in committed relationships. The findings to date suggest that for this group pornography use is associated, both positively and negatively, with their own and their partner’s sexual and relationship lives. Researchers can use these findings as a starting point to conduct further research in the area, to further investigate what makes women choose to watch pornography and whether women believe pornography has a role to play in their sexual and relationship lives.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Megan Maas for her helpful feedback on the protocol of this SR, as well as Mrs Dilan Kılıç Onar for acting as the second rater.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Throughout this paper the words impact and influence will be used interchangeably to indicate an association but not to assume causality.

2 For the sake of brevity, all included research will be called papers or studies, interchangeably from now on.

3 Non-randomized studies (NRS) are defined here as any quantitative study estimating the effectiveness of an intervention (harm or benefit) that does not use randomization to allocate units to comparison groups. This includes studies where allocation occurs in the course of usual treatment decisions or by individuals’ choices, i.e. studies usually called observational Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2008). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley, John & Sons.

4 The phrase sexual and relationship lives was chosen in order to incorporate all the terms used by the researchers in the included studies. Most of these terms appear as sub-themes in the analysis such as: Sexual Satisfaction, Relationship Satisfaction, Sexual Desire, Intimacy, Dyadic Satisfaction, Marital Quality, Sexual Quality.

5 The psychometric tools used are mentioned in Table 2 - Characteristics of included papers.

6 The word policy is used here to cover refer to a different range of options sexual education provided by teachers, by parents or by clinicians, and not just official high-level policy.

References

- Alexandraki, K., Stavropoulos, V., Anderson, E., Latifi, M., & Gomez, R. (2018). Adolescent pornography use: A systematic literature review of research trends 2000-2017. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 14(1), 47–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.2174/2211556007666180606073617

- Annon, J. S. (1976). The PLISSIT model: A proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 2(1), 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01614576.1976.11074483

- Aromataris, E., & Pearson, A. (2014). The systematic review: An overview. Synthesizing research evidence to inform nursing practice. American Journal of Nursing, 114(3), 53–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000444496.24228.2c

- Ashton, S., McDonald, K., & Kirkman, M. (2018). Women's experiences of pornography: A systematic review of research using qualitative methods. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 334–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1364337

- Ashton, S., McDonald, K., & Kirkman, M. (2019). Pornography and women's sexual pleasure: Accounts from young women in Australia. Feminism & Psychology, 29(3), 409–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353519833410

- Ashton, S., McDonald, K., & Kirkman, M. (2020). Pornography and sexual relationships: Discursive challenges for young women. Feminism & Psychology, 30 (4), 489-507,. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353520918164

- Attwood, F. (2005). What do people do with porn? Qualitative research into the consumption, use, and experience of pornography and other sexually explicit media. Sexuality & Culture, 9(2), 65–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-005-1008-7

- Baxter, S., Blank, L., Guillaume, L., Squires, H., & Payne, N. (2011). Views of contraceptive service delivery to young people in the UK: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 37(2), 71–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc.2010.0014

- Benjamin, O., & Tlusten, D. (2010). Intimacy and/or degradation: Heterosexual images of togetherness and women's embracement of pornography. Sexualities, 13(5), 599–623. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460710376492

- Bergner, R. M., & Bridges, A. J. (2002). The significance of heavy pornography involvement for romantic partners: Research and clinical implications. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 28(3), 193–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/009262302760328235

- Boland, A., Cherry, G. M., & Dickson, R. E. (2017). Doing a systematic review: A students's guide (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Los Angeles.

- Borgogna, N. C., Lathan, E. C., & Mitchell, A. (2018). Is women’s problematic pornography viewing related to body image or relationship satisfaction? Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 345–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2018.1532360

- Bray, N., Noyes, J., Edwards, R. T., & Harris, N. (2014). Wheelchair interventions, services and provision for disabled children: A mixed-method systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 309–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-309

- Bridges, A. J. (2007). Romantic couples and partner use of sexually explicit material: The mediating role of cognitions for dyadic and sexual satisfaction (Doctoral dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. University of Rhode Island, Ann Arbor. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/304817825?accountid=13963; http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/ProQuest+Dissertations+%26+Theses+Global&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&rft.genre=dissertations+%26+theses&rft.jtitle=&rft.atitle=&rft.au=Bridges%2C+Ana+Julia&rft.aulast=Bridges&rft.aufirst=Ana&rft.date=2007-01-01&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.isbn=978-0-549-41823-8&rft.btitle=&rft.title=Romantic+couples+and+partner+use+of+sexually+explicit+material%3A+The+mediating+role+of+cognitions+for+dyadic+and+sexual+satisfaction&rft.issn=&rft_id=info:doi/

- Bridges, A. J., Bergner, R. M., & Hesson-McInnis, M. (2003). Romantic partners' use of pornography: Its significance for women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 29(1), 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713847097

- Bridges, A. J., & Morokoff, P. J. (2011). Sexual media use and relational satisfaction in heterosexual couples. Personal Relationships, 18(4), 562–585. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01328.x

- Brown, C., Carroll, J., Yorgason, J., Busby, D., Willoughby, B., & Larson, J. (2017). A common-fate analysis of pornography acceptance, use, and sexual satisfaction among heterosexual married couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(2), 575–584. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0732-4

- Butler, A., Hall, H., & Copnell, B. (2016). A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 13(3), 241–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12134

- Cameron, K., Salazar, L., Bernhardt, J., Burgess-Whitman, N., Wingood, G., & DiClemente, R. (2005). Adolescents' experience with sex on the web: Results from online focus groups. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 535–540. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.10.006

- Carmenate, V. (2018). Relation between pornography use and acceptance and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual individuals in committed relationships. ProQuest Information & Learning. psyh. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2018-21182-299&site=ehost-live

- Carroll, J. S., Busby, D. M., Willoughby, B. J., & Brown, C. C. (2017). The porn gap: Differences in men's and women's pornography patterns in couple relationships. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 16(2), 146–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2016.1238796

- Cates, S. A. (2015). To each her own: Examining predictors and effects of pornography exposure among women (Doctoral dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Palo Alto University, Ann Arbor. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1748604154?accountid=13963;http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/ProQuest+Dissertations+%26+Theses+Global&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&rft.genre=dissertations+%26+theses&rft.jtitle=&rft.atitle=&rft.au=Cates%2C+Sarah+A.&rft.aulast=Cates&rft.aufirst=Sarah&rft.date=2015-01-01&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.isbn=978-1-339-27940-4&rft.btitle=&rft.title=To+each+her+own%3A+Examining+predictors+and+effects+of+pornography+exposure+among+women&rft.issn=&rft_id=info:doi/

- Cavaglion, G., & Rashty, E. (2010). Narratives of suffering among Italian female partners of cybersex and cyber-porn dependents. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17(4), 270–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2010.513639

- Ciclitira, K. (2004). Pornography, women and feminism: Between pleasure and politics. Sexualities, 7(3), 281–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460704040143

- Crooks, R., & Baur, K. (2011). Our sexuality. Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, Belmont, CA.

- Daspe, M.-È., Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Lussier, Y., Sabourin, S., & Ferron, A. (2018). When pornography use feels out of control: The moderation effect of relationship and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(4), 343–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405301

- Davis, A. C., Temple-Smith, M. J., Carrotte, E. R., Hellard, M. E., & Lim, M. S. C. (2019). A descriptive analysis of young women's pornography use: A tale of exploration and harm. Sexual Health, 17(1), 69–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/SH19131

- Dawson, K., Nic Gabhainn, S., & MacNeela, P. (2020). Toward a model of porn literacy: Core concepts, rationales, and approaches. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(1) - 1-15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1556238

- De Alarcon, R., De La Iglesia, J., Casado, N., & Montejo, A. (2019). Online porn addiction: What we know and what we don't—A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(1), 91–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8010091

- Dellner, D. K. (2008). Pornography use, relationship functioning and sexual satisfaction: The mediating role of differentiation in committed relationships (Doctoral dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Alliant International University, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/304822259?accountid=13963;http://resolver.ebscohost.com/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/ProQuest+Dissertations+%26+Theses+Global&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&rft.genre=dissertations+%26+theses&rft.jtitle=&rft.atitle=&rft.au=Dellner%2C+Danielle+Kristina&rft.aulast=Dellner&rft.aufirst=Danielle&rft.date=2008-01-01&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.isbn=978-0-549-88602-0&rft.btitle=&rft.title=Pornography+use%2C+relationship+functioning+and+sexual+satisfaction%3A+The+mediating+role+of+differentiation+in+committed+relationships&rft.issn=&rft_id=info:doi/

- Dixon-Woods, M., Bonas, S., Booth, A., Jones, D. R., Miller, T., Sutton, A. J., … Young, B. (2006). How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 27–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058867

- Dixon-Woods, M., Shaw, R. L., Agarwal, S., & Smith, J. A. (2004). The problem of appraising qualitative research. BMJ Quality & Safety, 13(3), 113–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.008714

- Döring, N. (2009). The Internet’s impact on sexuality: A critical review of 15years of research. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1089–1101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.04.003