Abstract

The needs of romantic partners of people transitioning gender remain neglected within academia and gender services. Following a systematic search, nine studies relating to female partners’ experiences were subjected to a thematic metasynthesis. Four themes were generated and entitled Changes in sexual relationship; New roles and responsibilities; Identity and belonging; and Transformation and loss Results are considered in relation to the dominance of the gender-affirmation discourse. Limitations of the review and reviewed studies are highlighted. Clinical implications for couples and partners of people transitioning gender are offered.

Introduction

The rates of people seeking medical interventions to transition gender has increased significantly over recent decades in the Global North, especially so for people wanting to transition from female-to-male and for those wishing to transition toward non-binary bodies (Aitken et al., Citation2015; de Graaf, Carmichael, Steensma, & Zucker, Citation2018; Handler et al., Citation2019; Wiepjes et al., Citation2018). Medical interventions supporting transition include hormone use and surgery (WPATH, Citation2012). However, many people elect to forgo medical intervention and instead socially transition whereby they might alter their name and pronouns, and act and dress according to socially constructed gender norms for their preferred identity (e.g., Nieder, Eyssel, & Köhler, Citation2020; Nolan, Kuhner, & Dy, Citation2019). Many countries are influenced by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH, Citation2012) guidelines that call for affirmation of a person’s preferred gender identity and a period of time in which the person is required to socially transition and take cross-sex hormones for at least a year prior to some types of surgical interventions such as phalloplasty.

Whilst there is consensus that distress among people wanting to alter gender is high (Galupo, Pulice-Farrow, & Lindley, Citation2020; Harrison, Jacobs, & Parke, 2020), there continues to be conflicting findings about the impact of transitioning at the group level. Notably, there have been inconsistent findings regarding benefits to psychological wellbeing (e.g. Colton, Fitzgerald, Pardo, & Babcock, Citation2011; Costa & Colizzi, Citation2016; Gorin-Lazard et al., Citation2013; Karpel & Cordier, Citation2013; van de Grift et al., 2018), with some suggesting that risk of suicide remains high or increases following transition (Biggs, Citation2019; Dhejne et al., Citation2011). At an individual level, there are various accounts of improved wellbeing and body-satisfaction (Elisheva, Citation2021; Finch, Citation2019; Wynn & Pemberton, Citation2021). However, there has also been growing recognition that a minority of people elect to ‘detransition’ for reasons such as no-longer identifying with a given gender, greater acceptance of sexuality, or making sense of any distress with recourse to other factors such as internalized sexism or abuse (Dhejne, Oberg, Arver, & Landen, Citation2014; Entwhistle, Citation2021; Expósito-Campos, Citation2021; Richards & Doyle, Citation2019).

Debates concerning the effectiveness and ethics of transition interrelate with contested philosophies about how ‘gender’, ‘gender identity’, and ‘sex’ should be understood; different understandings of these constructs call for different approaches to support people who want to transition (e.g. Pilgrim, Citation2021; Summersell, Citation2018; Wren, Citation2014). In recent years, the dominant position within gender services in Western societies has been one of gender-affirmation, whereby it is assumed that a person can be born with a gender-identity incongruent with their sex assigned at birth (APA, Citation2015). This position can be contrasted with theories that regard gender as performative rather than innate, with gendered subjectivities being understood as the result of socialization and performance of socially constructed gendered norms (Butler, Citation2006; Keener, Mehta, & Smirles, Citation2017) or hyper-identification with a particular gendered way of being (Stock, Citation2021). Whilst such perspectives do not necessarily preclude gender-affirmative practises, because performance of gender will be aided by altering physical appearance to match the gendered-scripts associated with one’s preferred gender-identity (e.g. Ashley, Citation2019), these different positions differ with regards to impacts regarding troubling or reinforcing gender-binaries. For example, understanding gender as socially constructed invites reflection upon the ways social structures and discourses police gender, marginalizing those who do not conform to gendered expectations and supporting the hierarchy of oppression that devalues female and non-heterosexual ways of being (Butler, Citation2006; Moore, Morgan, Russell, & Welham, Citation2022; Schippers, Citation2007). Overt recognition of power and socially constructed discourses can enable resistance to the hierarchy of oppression in ways that can be supported through transitioning (e.g. Nagoshi, Brzuzy, & Terrell, Citation2012). Conversely, if gender is understood as innate, then altering one’s name, appearance and behavior in order to ‘pass’ as the ‘opposite’ sex risks reinforcing gender-binaries (e.g. Reilly-Cooper, Citation2016).

Romantic relationships

Given gender is performed in relation to others, and gender intersects with constructions of sexuality (Ellis, Citation2012), romantic relationships are likely to also alter as one partner transitions. To date there has been a lack of research into romantic relationships of transgender individuals and the experiences of their partners (Moradi et al., Citation2016). Historically, people identifying as transgender in previously heterosexual marriages were required to divorce their partner prior to gender affirmative surgery, whilst the dominant assumption that sexuality is stable has resulted in many researchers presuming relationships would end following a partner transitioning (Meyerowitz, Citation2002). Yet, whilst many relationships do end during or after transition, research suggests that around half persist (Brown, Citation2009; Meier, Sharp, Michonski, Babcock, & Fitzgerald, Citation2013). In the limited research that exists, couples reported challenges such as discrimination and stigma, lack of trust, viewing their partner differently, difficulties in sexual intimacy and questioning their sexual orientations (Gamarel, Reisner, Laurence, Nemoto, & Operario, Citation2014; Gamarel et al., Citation2019; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018). Previous reviews suggest these specific challenges are arguably related to the impact of societal norms and expectations on the relationship in the context of shifting gender roles and uncertainty regarding sexual orientation (Marshall et al., Citation2020), although many couples appear able to reconstruct previously established sexual norms and sexual preferences within a relationship (Thurston & Allan, Citation2018).

Rationale/aims

To our knowledge, no previous reviews have focused solely on unique experiences of partners of people who have transitioned gender, with previous reviews in this area being concerned with experiences of both partners within couples. Our initial review question sought to examine the experiences of partners of people who have, or are transitioning gender, however reviewed studies reported on almost exclusively female participants (see below). We therefore revised our original question to: ‘What are the experiences of female partners of people who have transitioned or are transitioning gender?’

Method

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted to capture published research literature regarding the experiences of romantic partners of people who had transitioned or were transitioning gender. The focus was restricted to peer reviewed qualitative studies due to the interpretive orientation of the metasynthesis and because qualitative research is more aligned with our aims of capturing experiences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). No other exclusion criteria were applied. Searches were conducted between July 2020 and September 2020 using four electronic databases (Medline, PsychInfo, Scopus, and Web of Science) and the search terms displayed in .

Table 1. Search terms used in literature search.

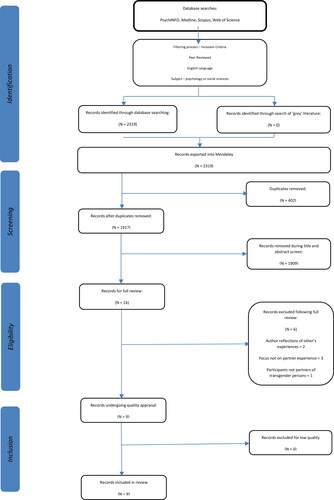

In total, 2319 returns were identified through database searches and exported into Mendeley (reference management software). Following application of filters and removal of duplicates, 1917 papers remained. These were reduced to nine studies after rigorous screening against inclusion criteria. Neither forward citation nor ‘grey literature’ searches resulted in additional papers. provides a flow-chart of the search process. All studies were deemed of sufficient quality to retain following appraisal using the qualitative CASP (2018) tool.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Thematic synthesis

The process of Thematic Synthesis followed Thomas and Harden (Citation2008) stepwise approach of:

Coding text

Developing descriptive themes

Generating analytical themes

Each article included in the review was coded line by line, with new codes developed as necessary, supporting translation of concepts between articles. This supported the generation of nine descriptive themes, providing an aggregative summary of relevant findings from original articles. The aim of Thematic Synthesis is to move beyond the primary studies to generate analytic themes offering new explanations (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). These were generated by considering the descriptive themes identified to answer current review questions, and led to the creation of four analytical themes, onto which descriptive themes could be mapped. We adopted a contextual constructivist position for the metasynthesis, an epistemological position that recognizes reality is subjectively shaped by one’s own perspective and cultural context (Madill, Jordan, & Shirley, Citation2000).

Findings

Overview of included articles

The nine papers included reported data from a total of 103 partners (n = 82) or ex-partners (n = 21) of people who had transitioned. Joslin-Roher and Wheeler (Citation2009) did not report participants’ sex and Platt and Bolland (Citation2018) only provided partial report. Of the studies that did report participants’ sex the majority were female (n = 86) with relatively few male participants (n = 6). In respect of gender identity, it is notable that some participants identified with more than one gender identity category; the majority identified as women/female (n = 93) with other gender identities including men/male (n = 3), trans-women (n = 3), gender fluid/bigender (n = 2), trans demi-girl (n = 1), trans-man (n = 1), femme (n = 1), gender queer (n = 1), and femme dyke (n = 1). That most participants were women or female is consistent with previous research which has noted similar over-representation within the literature (Chase, Citation2011; Chester, Lyons, & Hopner, Citation2017; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018), and is unsurprising given five studies intentionally recruited female participants (Alegria, Citation2010, Citation2013; Brown, Citation2009, Citation2010; Theron & Collier, Citation2013). The majority of participants were ‘white’ (n = 83, 81%), with race/ethnicity not reported for six participants (6%). Although 20% of participants had ceased their relationships with partners, reviewed studies did not contain information regarding the reasons for relationships ending. Two studies did not report duration of participant relationships (Platt & Bolland, Citation2018; Theron & Collier, Citation2013) and it was not possible to distinguish between the length of relationship of those separated or those still partnered in Joslin-Roher and Wheeler’s (Citation2009) study. For those still partnered, the mean duration of relationships was 21 years (range 0.5 − 45 years). For the one study reporting on partners who had separated, relationships had lasted a mean of five years (Chester et al., Citation2017).

Sexual orientation of participants was reported in all but one study (Alegria, Citation2010), with some papers reporting sexuality both pre- and post-disclosure/transition (Brown, Citation2009, Citation2010; Chester et al., Citation2017; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018) and others reporting sexuality but not delineating within the demographics whether this had changed during their partner’s transition (Alegria, Citation2013; Chase, Citation2011; Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009; Theron & Collier, Citation2013). Sexualities of participants before their partners’ disclosure/transition included: lesbian (n = 19), queer (n = 11), bisexual (n = 3), pansexual (n = 4), heterosexual (n = 4), gay (n = 3) and femme lesbian (n = 1). Sexualities after their partners disclosure/transition included: lesbian (n = 6), queer (n = 22), bisexual (n = 2), open (n = 2), pansexual (n = 5), heterosexual (n = 1), femme lesbian (n = 1), gay (n = 2), and one person identified as a lesbian dating a transman.

The gender-identities of transitioning/transitioned partners were more varied, with around half being identified as transmale (n = 53, 52%), 44% as transfemale (n = 45), 2% as gender-fluid (assigned male at birth) (n = 2), 1% as masculine/gender-neutral (assigned gender neutral at birth) (n = 1) and two person as gender-queer (assisgned female at birth) (2%). Most studies were conducted in northern America (USA = 5; Canada = 1), with New Zealand and South Africa being the sites for the remaining two papers. All nine studies used interviews for data collection with one study also utilizing a questionnaire (Alegria, Citation2010). Methods of analysis included deductive analysis (Alegria, Citation2010, Citation2013), constant comparative method (Alegria, Citation2010, Citation2013), thematic analysis (Theron & Collier, Citation2013), grounded theory (Brown, Citation2009; Citation2010), interpretative phenomenological analysis (Chester et al., Citation2017; Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018), and a psychoanalytic case study design (Chase, Citation2011). The reviewed studies had different aims, specifically: to examine the experiences of sexual minority women partnered with transmen (Brown, Citation2009; Citation2010; Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009; Theron & Collier, Citation2013), to examine the experiences of partners of people who have or are going through a gender transition (Chase, Citation2011; Chester et al., Citation2017; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018), to examine the impact of a partner’s gender transition on identities and relationships (Chester et al., Citation2017), to examine participants’ experiences of sex and sexuality following a partner’s disclosure of gender transition (Alegria, Citation2013; Theron & Collier, Citation2013), and to examine relationship challenges and maintenance activities of couples where one person identifies as transgender (Alegria, Citation2010).

Thematic synthesis

The final superordinate and subordinate themes are described below. After each quote we have added available information concerning participant sex and gender-identity, followed by information about the gender a participant’s partner had transitioned toward. illustrates which papers contributed to each theme.

Table 2. Original paper contributions to synthesis themes.

Changes in sexual relationship

Participants in several studies reported various changes in their sexual relationship following a partner ‘coming out’ or transitioning. Experiences related to changes in their partners’ body satisfaction (subtheme 3.3.1.) and sex role dynamics (subtheme 3.3.2).

3.3.1: Body satisfaction and sexual intimacy

Participants in four studies described how their partner transitioning had impacted upon sexual intimacy within the relationship, which was often related to their partner’s body-satisfaction (Brown, Citation2010; Chester et al., Citation2017; Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018). Some participants identified that their partners had experienced heightened body discomfort in the period leading up to medical transition, which affected sexual intimacy and was often attributed to the transitioning partner’s body becoming ‘off limits’ during sex:

"We went through a period where intimacy was kind of hard because of the major dysphoria. But we’re working through that and figuring out what’s comfortable for him, what works for me … that kind of thing…" Cisgender natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Platt & Bolland, Citation2018, p. 1260)

"I think sexually, he had a lot of shame around his body, and sexuality was something that got pushed aside…[I didn’t feel] desired anymore…. Even though I knew it was about him—it still made me feel crappy about myself." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, separated (Brown, Citation2010, p. 567)

Some participants reported greater sexual satisfaction as their partner became more comfortable with their body as medical transition progressed:

"Post-surgery we’ve found that we’re both…really satisfied with the results and really happy about his body … Heightened sense of self-confidence and self-worth. has been a contributing factor in our sex life." Female identifying, transmale partner (Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009, p. 41)

And now he’s feeling better about his body, he’ll initiate sex. Like I just never knew where he was coming from—if it was okay, or if it was not okay and how he was feeling—it was a real point of tension between us…so it became better that way. Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Brown, Citation2010, p. 567)

Not all participants reported greater sexual satisfaction as their partner transitioned, with some reporting little change or others identifying that they no longer felt attracted to their partner.

"Actually, [sex] hasn’t changed at all" Cisgendered natal female, transmale partner, partnered (Brown, Citation2010, p. 569)

"I’ve only ever fallen in love with men, and then after [ex-partner] starting taking oestrogen, it sort of confirmed to me that I’m definitely heterosexual. I couldn’t see myself having a relationship with a woman." Cisgendered natal female, transfemale partner, seperated (Chester et al., Citation2017, p. 1413).

3.3.2: Changes in sexual roles and dynamics

Participants reflected how the motivation for, or function of sex had altered as their partners transitioned, with partners who had typically been more submissive during sex prior to transition sometimes becoming more dominant, and vice versa. These changes were sometimes linked with couples adopting sexual roles more aligned with gender-binary norms, with partners transitioning to female becoming more submissive, and transmales becoming more dominant and aggressive during sex:

“… for Amanda and her partner sex was also about allowing her partner to express their femininity. Her partner took on a more submissive role and requested that Amanda take on a dominant, more masculine role by penetrating her.” Cisgender natal female, transfemale partner, separated (Chester et al., Citation2017, p. 1412)

"The sexual elements of the relationships changed a lot. Ah the power play of like being a male therefore being dominating, therefore being the top [sic.]. And I didn’t like that at all. It wasn’t something that sat right with me." Cisgender natal female, transmale partner, separated (Chester et al., Citation2017, p. 1412)

Participants discussed a sense of marked loss associated with the changing roles being played out and regret for sexual activities they could no longer take part in:

"I truly miss… the way we had sex. Sex is good just sometimes his way of fucking me is like a man and it’s hard to be turned on. He no longer likes penetration and me touching his chest… I want to explore and do more, but I can’t with him" Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Brown, Citation2010, p. 568)

Although many participants had difficulties with the changes, some participants discussed how the shifting dynamics were positive and led to increased enjoyment and satisfaction in their sexual relationship.

"It was like [being] a kid in a candy store, it truly, truly, truly was, and it’s really kind of shifted out of this space of being bottom, bottom, bottom… to really exploring dominance, and so it’s been liberating and powerful." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Brown, Citation2010, p. 568)

New roles and responsibilities

All studies reported that participants had taken on new roles and responsibilities as their partner transitioned gender. These included advocating for their partner and affirming their partner’s gender identity (subtheme 3.4.1). Participants also spoke of supporting their partner’s emotional needs, sometimes at the expense of their own (subtheme 3.4.2).

Affirming and advocating

Participants discussed taking on roles affirming their partner’s gender identity, becoming involved in advocacy and activism, as well as adopting a vigilant and protective role in the relationship (Alegria, Citation2010, Citation2013; Brown, Citation2009, Citation2010; Chase, Citation2011; Chester et al., Citation2017; Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018; Theron & Collier, Citation2013). Participants spoke about how they took on the role of protecting their partner from possible misgendering within family and community settings:

"At first, it was a little difficult and he [Family member] would continue to, although I asked him, he would continue to say, ‘he’. And I just one day turned to him and said, ‘You respect [my partner] and [my partner] is ‘she’ or you just don’t come to dinners and stuff anymore’. And ever since then he’s been great. I couldn’t have been more direct to him" Cisgendered natal-female, transfemale partner, partnered (Platt & Bolland, Citation2018, p. 1262).

"Before we go out, I need to consider who’s gonna be there, how they’re orientated. […] The moment we enter some places, I have to identify who’s gonna be the most comfortable person to be around, who’s gonna know that we’re dealing with a “he” not a “she” and just put it out there nicely, so that everybody else catches on because just that one person is gonna use the incorrect pronoun and that’s gonna throw us off completely." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Theron & Collier, Citation2013, p. 8)

Some participants were comfortable assuring their partner they would affirm their preferred gender-identity and support them through transition:

"I kind of heard the rumblings and always said… “You can do it and I’ll be here for you. It’ll be alright.” … “Of course, I’ve been telling you for months. Of course, go ahead, let’s do this. Come on, it’s fine, it’ll be fine.” [I am] 100% supportive." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Chase, Citation2011, p. 442)

Others discussed how they became involved in activism for trans-rights alongside their partners, for example through involvement in trans groups, starting support groups, or educating others:

"I slowly changed to being an activist. We can improve society. Through my association with the [organisation name], I’ve been giving talks with [partner] to classes, and to basically anywhere we’re needed." Cisgendered natal-female, transfemale partner, partnered (Alegria, Citation2010, p. 915)

"[…] we can’t hide it anymore, you know, especially in our black communities, I feel like I’m playing a big role because it hasn’t been out and here I am, as comfortable as I am, I talk about it anyway, you can ask me anything and I’ll tell you. They ask me about sex. I tell them. Because I don’t think there’s anything to hide. It’s more helping them to realize that if they’re gonna have kids that are gonna be trans, they need to understand that it is possible. It happens." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Theron & Collier, Citation2013, p. 8)

Emotional caretaking

Participants discussed how throughout the transition process their position in the relationship became focused on supporting the needs and emotions of the transitioning partner, sometimes placing strain upon the relationship:

"It’s a daily thing. It’s always there. It’s huge. I wish it wasn’t. I feel like the past two and a half years of my life [during transition] I’ve missed a lot. I feel like my focus went from the rest of my life to [Partner] really quickly, and it has stayed there." Cisgendered natal- female, transfemale partner, partnered (Alegria, Citation2010, p. 913)

"… she was so preoccupied with her own emotions that she couldn’t think about anyone – what she was doing to other people … quite a long period of it she didn’t really care for and that was, I mean, if you have a relations]hip with people who don’t care for you that’s obviously going to end up in tears and not very nice." Cisgendered natal-male, transfemale partner, partnered (Chester et al., Citation2017, p. 1411)

Some participants recognized their own emotional needs were unaddressed and subordinated by the focus of support often being on the partner, with some reflecting they felt it necessary to push to ensure their needs were also recognized:

"The times that I need breathing room the most are sometimes the times that he needs support the most. … Sometimes … I just need to go do something with my friends and he’s kind of like, stay with me, I need you" Female identifying, transmale partner (Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009, p. 41).

"Well, I think for me the biggest, the most important part in this process has been to make sure that, like, I really assess my own needs too. And I think that we as partners, especially if you’re already partnered with the person when they start their transition or when they come out, you sort of put a lot of pressure on yourself to just be the support and be the pillar that’s going to, you know, help you through this and, we kind of just disregard ourselves throughout a lot of it." Cisgendered natal-male, transfemale partner, partnered (Platt & Bolland, Citation2018, p. 1259)

Identity and marginalization

In all studies, participants reflected upon their position in LGBTQ communities, as well as their sexuality and what this meant as their partner transitioned. Participants spoke of a sense of becoming ‘invisible’ within LGBTQ communities when being defined within in a now same-sex relationship rather than a mixed-sex one:

"I still identify as lesbian, but— to myself I identify as lesbian. To the world, I’ve become identified by the way I look, as heterosexual, or bisexual at best but that doesn’t represent me, and I can’t out him, so … I’m in a strange and uncomfortable place…" Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Brown, Citation2009, p. 67)

"At Pride events it gets weird and I feel awkward because we look like a really straight couple. I don’t want to hold hands because we have the hetero-privilege in that context. We joke that we’re not straight enough for the straight folks and we’re not queer enough for the queer folk." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Platt & Bolland, Citation2018, p. 1263)

Participants reflected upon whether they should or could retain or change their sexual identity whilst maintaining a relationship with their transitioning partner:

"How do I be a lesbian in the world married to a man? Like losing that public identity." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Chase, Citation2011, p. 445)

"So that was the other reason that I fought probably, within myself to keep that lesbian identity because I didn’t want, like these people that … I had felt sort of slighted from to be right, like all along I wasn’t really a lesbian or something." Female identifying, transmale partner (Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009, p. 39)

Participants discussed how their partners were represented and affirmed in LGBT communities by the ‘T’, but were themselves unsure about how they fitted in as a partner of a trans person:

"You can’t claim it anymore and therefore you kind of don’t exist. Your partner does, though, because they’re trans. You become invisibilized. You’re the non-person. But your transgender partner is still recognised. They’re still the T." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Theron & Collier, Citation2013, p. 9).

"We have our straight friends in the neighbourhood and in church, and I don’t feel I really belong there. The people at the diversity centre – I’m not really one of them. I’m an ally there. I’m not one of them. So I kind of walk between two worlds and I just kind of walk that thin line now. I feel like I’m neither one." Cisgendered natal-female, transfemale partner, partnered (Alegria, Citation2010, p. 913)

In four of the studies, participants discussed responses they had encountered from LGBTQ communities, which varied, with some being supportive and others being querulous and intolerant (Brown, Citation2009; Chester et al., Citation2017; Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009; Theron & Collier, Citation2013).

"The lesbian community feels very much betrayed by me. […] finally I’ve got somebody that I love as a human being […] but the community where I operate now is questioning, definitely […] you’ve betrayed us. You’ve been the voice of lesbians all along […] who’s gonna be talking for us – for our rights and all those things" Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Theron & Collier, Citation2013, p. 4).

"… if you’re a lesbian and you sleep with a man, then you are has-bian, you know [laughs]. Like, and everyone looks at you and frowns upon you…" Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, separated (Chester et al., Citation2017, p. 1413)

"I think that’s been … the biggest thing … not knowing who’s rejecting and just trying not to assume that just because you’re gay or you’re bi that you’re gonna be okay with it" Female identifying, transmale partner (Joslin-Roher & Wheeler, Citation2009, p. 43).

None of the papers discussed positioning within the LGBTQ communities for participants who were transitioning to outwardly homosexual relationships.

Loss and transformation

This theme encompasses how some participants encountered a sense of loss as their partner transitioned, whilst others felt able to celebrate the transformation alongside their partner. In five studies, participants discussed a sense of loss for their pre-transition partner (Alegria, Citation2010; Chase, Citation2011; Chester et al., Citation2017; Platt & Bolland, Citation2018; Theron & Collier, Citation2013). Partners discussed the wide variety of changes including physical and personality changes their partners went through:

"It’s like little tiny insidious losses that you don’t notice until all of a sudden you have 50 of them and one day you wake up and the weight of the world is on you because you no longer recognize the person you’re with anymore." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Chase, Citation2011, p. 440)

"…the first time he had any testosterone, he just had a little bit and suddenly he smelled different and I couldn’t kiss him and I was totally freaked out ‘cause it was like ‘who are you? You smell different. You’re not my person!’ And that was really, really upsetting for him but it was really upsetting for me…he got so hairy and he, his body totally changed shape." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, separated (Chester et al., Citation2017, p. 1411)

Participants discussed difficulties in grieving for someone they felt they had lost whilst they were still with them:

"The constant presentation of [partner] was hard, and I missed my husband. I needed my husband back some of the time.” Cisgendered natal-female, transfemale partner, partnered (Alegria, Citation2010, p. 913)

"…That’s never going to happen again, that kind of like girly-girly kind of stuff, that’s never going to happen again, those types of girly things that like are just not ever going to come back. It’s a little sad because I liked that. But it’s hard to complain when he’s still, you know, a fabulous guy!" Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Chase, Citation2011, p. 440)

Other participants discussed a sense of feeling a closer connection with their partners and a greater satisfaction in their relationship:

"Since she’s been her true self, she smiles a lot more. She isn’t as grumpy, and that makes the whole day easier to handle" Cisgendered natal-female, transfemale partner, partnered (Alegria, Citation2010, p. 914)

Joslin-Roher and Wheeler (Citation2009, p. 42) reported:

"[Participants]identified that witnessing their partners’ joy at transition increased satisfaction. Additionally, some subjects described increased satisfaction in the relationship as they were able to get through difficult times and work through various issues related to the transition."

Additionally, participants discussed ways in which they had learned from or been inspired by their partners’ transition and how this had affected their own self-knowledge:

"It’s finding the right person. […] It’s definitely opened my eyes to helping me understand myself better and what I’m attracted to and to not be putting myself in a box like I used to." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Platt & Bolland, Citation2018, p. 1261)

"I came to the realisation that what had attracted me to my previous partners had not been first their gender or whatever, it had been the self. I had either been attracted to a personality trait or one thing or the other and then came down to how we had sex, but sex usually comes after the attraction." Cisgendered natal-female, transmale partner, partnered (Theron & Collier, Citation2013, p. 4).

Discussion

The results of this metasynthesis highlight some of the challenges women navigate as their partner transitions gender. Many relationships are described as thriving through transition: women can celebrate their partners’ transition, benefiting from increased intimacy or taking pride in being able to advocate for their partner and support their gender-affirmation. However, others experienced grief for lost aspects of their partner and relationship, marginalization within LGBTQ communities, and a sense that their needs ought to be deprioritised in order to support the transition and affirmation of their partner. Some women felt less attraction to their partners following their transition or experienced the changes in sexual roles aversive. This section is used to consider key findings in relation to extant literature. We conclude by considering review limitations and clinical implications.

Similarly, to that of Marshall et al. (Citation2020) the current review highlights the challenges partners face within their relationships, particularly in terms of navigating sexual relationships and partner’s own sexual identity. With respect to changes to a sexual relationship, our findings complement those of Thurston and Allen (Citation2018), who also noted that transition affected sexual intimacy through renegotiating of sexual norms, shifts in sexual desires and frequency of sex, and rediscovering of sexual experiences. Whilst results from the current review further emphasize that sexuality and sexual expression is fluid, and argue against imposition of the labels of restrictive sexuality on couples for whom one or more partners have transitioned (e.g. Schleifer, Citation2006), some participants in reviewed studies articulated a loss of sexual attraction to their partners. Although little consideration was afforded to the differences associated with the gender to which a partner was transitioning, women whose partners transitioned to male bodies expressed dislike of the ways their partners performed more heternormative-male sex acts, and may, illustrate the potential for transitioning as reinforcing gender-binary scripts and heteronormativity. Dominant, culturally-constituted, gendered-discourses construct males as sexually dominant and females as sexually more submissive; as people to whom sex is ‘done to’ and whose sexual satisfaction is more commonly effaced (Allen, Citation2003; Gavey, Citation2005; Moran, Citation2017). That scripts for same-sex or non-heterosexual sex are less pervasive within heterosexist societies (Ellis, Citation2012) potentially permits greater space for renegotiation of sex roles when a woman’s partner transitions toward a female or non-binary identity, than when a partner transitions to male and may feel pressure to conform to heteronormative gender roles to affirm preferred identity. Marshall et al. (Citation2020) review also highlights the challenges of navigating binary and heteronormative societal norms within participants relationships.

Although five studies exclusively recruited female participants, few males were recruited within other papers. Whilst many males do remain in relationships with a transitioned partner, differences in the ways females and males are socialized may contribute to men being more likely to separate (Lewins, Citation2002). Indeed, women in western cultures have been socialized and expected to be more passive, prioritize the needs of men, and build and maintain family relationships (Erchull, Liss, Axelson, Staebell, & Askari, Citation2010; Rogers, Nielson, & Santos, Citation2021; Stock, Citation2021). Holloway (1984) seminal text on the construction of gendered sexual identities described how women are socialized in relation to the have/hold discourse, which gives primacy to monogamy and devalues women’s sexuality. Conversely, the male sex drive discourse, described as dominant in Western male sexual socialization, places a greater emphasis on sexual prowess and purportedly biologically-driven urges to pursue multiple sexual partners (ibid.). Thus, whilst women may be more likely to encounter expectations to remain with transitioning partners, men may be more likely to experience increased stigma and threats if they continue a relationship. Given male socialization occurs within a heteronormative matrix (e.g., Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005) it could be speculated that threats might be magnified if a man’s partner transitions away from a female identity.

Just as the dominance of gendered sexuality scripts will impact upon how partners make sense of their identities and interactions with a transitioning partner, so too will dominant discourses related to transitioning and trans identities. Many women spoke about how the focus of attention being on the person who is transitioning gender, with participants speaking about deprioritising their own needs or having these disregarded. The gender-affirmative movement has done much to empower people to act on their rights to alter their body and gender-identities, and to raise awareness of the distress many people can experience in relation to gender (Spencer et al., Citation2021). However, the dominance of this position within societal subcultures might create a context that disempowers partners of people transitioning gender to privilege their own needs within relationships. The dominance of the gender-affirmative position might provide a context for some women to celebrate their partner’s transformation to their ‘true selves’ and support women in taking pride in their identities as advocates for their partner and trans rights. For others, the dominance of gender-affirmative narrative may make it harder for people to assert their needs, and especially so for women because of the gendered have/hold expectations.

A number of women described their sense of alienation from the LGBTQ communities they had previously found supportive as a consequence of shifting from a same-sex to a mixed-sex relationship. Here too, the dominance of gender-affirmative narratives within some LGBTQ communities will shape women’s experiences. For many women who will have endured significant challenges in resisting heteronormative assumptions to identify as a lesbian (e.g Slater & Mencher, Citation1991), the felt expectations of privileging their partners’ needs may make it harder to speak out about the threats to their own identity and any pressure to accept intimate interactions with a male partner. However, there is no single ‘LGBTQ community’ and trans identities are not valued within some networks, with some participants encountering accusations of ‘betrayal’ for continuing a relationship with a trans-male partner.

Clinical implications for couples therapy

The needs of partners of people transitioning gender are under-researched and predominantly unacknowledged within gender services, which are predominantly guided by the gender-affirmative position within western nations. Whilst such an orientation supports the rights of people to socially, legally and medically transition, the dominance of the gender-affirmative position and gendered discourses that devalue women’s sexuality can result in women finding it hard to assert their needs. Whilst the potential for transitioning to trouble gender-binaries is well recognized (e.g Ashley, Citation2019; Spencer et al., Citation2021), present and previous results suggest that transitioning can reify gender-binaries in ways that police and replicate gender hierarchies and the continued oppression of women and people who do not conform to gender stereotypes (Dewey & Gesbeck, Citation2017; Johnson, Citation2016; Langer & Martin, Citation2004). Women who identify as lesbian may in some cases experience a sense of coercion into enacting heteronormative scripts they had worked to resist whilst growing up in heterosexist societies, whilst often losing important sources of support from LGBTQ communities.

It is important that services create spaces for partners of people transitioning to have their experiences heard and validated. Consideration should be given to the ways the dominance of the trans-affirmative narrative can silence partners of the person transitioning and space should be created within couples therapy to explore how their needs can be supported within the relationship. It is important for professionals involved in couples work to both recognize the fluidity of sexuality and avoid promoting the idea that the partner of someone transitioning gender should continue to be in a sexual relationship with a partner whose body is no longer aligned with a person’s sexual preferences. The results further point to the importance of exploring how gender-identity and transitioning is understood. We argue that it is relevant for professionals to facilitate awareness of the different ways genders can be performed, and reflection on how couples would like transitioning to trouble or replicate binary ways of being. The effects of marginalization from diverse LGBTQ communities warrant further consideration, and consideration should be given to how partners might be able to maintain links with such groups or access support from alternate support networks.

Limitations and future research

Various limitations affect the validity and generalizability of our conclusions. Although we had set out to explore the experiences of partners irrespective of gender, the vast majority of participants in reviewed studies were women and we have attempted to frame our interpretation of results accordingly. Reviewed papers often did not report whether experiences were different for participants if partners had transitioned to female, male or non-bianry identities. The troubling of categorical understandings of gender and sexuality by queer theorists has been valuable, but there seems a danger of neglecting the importance of gendered scripts in making sense of individual experience within societies in which oppression and socialization is prevalent (Ellis, Citation2012; Johnson, Citation2015). Future research should consider the importance of capturing the ways intersectional oppression impacts upon experiences of partners, including consideration of other aspects of privilege and discrimination such as ‘race’, religion, ‘mental health’, dis/ability and class. Focusing on particular sub-groups might support interpretation of findings in relation to particular scripts (e.g. das Nair & Butler, Citation2012; Moore et al., Citation2022 Schippers, Citation2007); for example, the experiences of women partners may vary depending on their own sexuality or gender-identities (c.f. Gunn, Hoskin, & Blair, Citation2021), which were homogenized in our analysis. Similarly, experiences are likely to vary if couples had children; a factor that was not considered in reviewed papers.

Reviewed studies often did not provide information such as the duration of relationships, parental status, or reasons why people had separated from partners. Future research should focus on participants’ sense making of factors that supported relationship stabilization, maintenance or ending. Our interpretation of findings suggests that women’s relationship to the gender-affirmative position and how they make sense of gender-identity will play an important part in shaping personal experiences when a partner transitions gender. Future studies might explicitly seek to relate experiences to such attitudes and understandings. Although our use of thematic Synthesis enabled us to move beyond the interpretations of researchers in the primary studies through coding of participant quotations and researchers’ analyses (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009), our review could not fully center the experiences of the women participants in the original studies because we did not have access to full interview transcripts.

Finally, most research was conducted within North America and cultural scripts will impact upon how gender, sex, relationships and sexuality are understood and experienced. The results of this review should thus not be generalized to people from non-Western cultures and further research is needed outside of Northern America.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Aitken, M., Steensma, T. D., Blanchard, R., VanderLaan, D. P., Wood, H., Fuentes, A., & Zucker, K. J. (2015). Evidence for an altered sex ratio in clinic-referred adolescents with gender dysphoria. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 756–763. doi:10.1111/jsm.12817

- *Alegria, A. (2010). Relationship challenges and relationship maintenance activities following disclosure of transsexualism. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17, 909–916. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01624.x

- *Alegria, A. (2013). Relational and sexual fluidity in females partnered with male-to-female transsexual persons. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20, 142–149. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01863.x

- Allen, L. (2003). Girls want sex, boys want love: Resisting dominant discourses of (hetero)sexuality. Sexualities, 6(2), 215–236. doi:10.1177/1363460703006002004

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. doi:10.1037/a0039906

- Ashley, F. (2019). Thinking an ethics of gender exploration: Against delaying transition for transgender and gender creative youth. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 223–236. doi:10.1177/1359104519836462

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research, London: Sage.

- Biggs, M. (2019). Britain’s experiment with puberty blockers. In M. Moore & H. Brunskell-Evans (Eds.), Inventing transgender children and young people. Cambridge: Scholars Publishing.

- *Brown, N. R. (2009). ‘I’m in transition too’: Sexual identity renegotiation in sexual-minority women’s relationships with transsexual men. International Journal of Sexual Health, 21(1), 61–77. doi:10.1080/193117610902720766

- *Brown, N. R. (2010). The sexual relationships of sexual-minority women partnered with trans men: A qualitative study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 561–572. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9511-9

- Butler, J. (2006). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (1998). 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Retrieved from www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm.

- *Chase, L. M. (2011). Wives’ tales: The experience of trans partners. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 23(4), 429–451. doi:10.1080/10538720.2011.611109

- *Chester, K., Lyons, A., & Hopner, V. (2017). ‘Part of me already knew’: The experiences of partners of people going through a gender transition process. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 19(12), 1404–1417. doi:10.1080/13691058.2017.1317109

- Colton, S. L., Fitzgerald, K. M., Pardo, S. T., & Babcock, J. (2011). The effects of hormonal gender affirmation treatment on mental health in female-to-male transsexuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 15(3), 281–299, doi:10.1080/19359705.2011.581195

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. doi:10.1177/0891243205278639

- Costa, R., & Colizzi, M. (2016). The effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on gender dysphoria individuals’ mental health: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1953–1966. doi:10.2147/NDT.S95310

- das Nair, R. & Butler, C. (2012). Intersectionality, sexuality and psychological therapies. Working with lesbian, gay and bisexual diversity. Oxford: BPS Blackwell, pp. 31–58.

- de Graaf, N. M., Carmichael, P., Steensma, T. D., & Zucker, K. J. (2018). Evidence for a change in the sex ratio of children referred for gender dysphoria: Data from the Gender Identity Development Service in London (2000–2017). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(10):1381–1383. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.08.002

- Dewey, J. M., & Gesbeck, M. M. (2017). (Dys) functional diagnosing: Mental health diagnosis, medicalization, and the making of transgender patients. Humanity & Society, 41(1), 37–72. Do: 10.1177/0160597615694651

- Dhejne, C., Lichtenstein, P., Boman, M., Johansson, A. L. V., Långström, N., & Landén, M. (2011). Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: Cohort study in Sweden. PLoS One 6(2): e16885. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016885

- Dhejne, C., Oberg, K., Arver, S., & Landen, M. (2014). An analysis of all applications for sex reassignment surgery in Sweden, 1960-2010: Prevalence, incidence, and regrets. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1535–1545. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0300-8

- Ellis, S. J. (2012). Gender. In R. das Nair & C. Butler (Eds.), Intersectionality, sexuality and psychological therapies. Oxford: BPS Blackwell, p. 31–58.

- Elisheva, S. (2021, November 1). How I changed my body’s biology: What it means to gender transition. Retrieved from https://unorthoboxed.com/2021/11/01/how-i-changed-my-bodys-biology-what-it-means-to-gender-transition/

- Entwhistle, K. (2021). Debate: Reality check - Detransitioner’s testimonies require us to rethink gender dysphoria. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 26(1), 15–16. doi:10.1111/camh.123

- Erchull, M. J., Liss, M., Axelson, S. J., Staebell, S. E., & Askari, S. F. (2010). Well… she wants it more: Perceptions of social norms about desires for marriage and children and anticipated chore participation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 253–260.

- Expósito-Campos, P. (2021). A typology of gender detransition and its implications for healthcare providers. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(3), 270–280. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2020.1869126

- Finch, S. D. (2019, March 6). I was my own body terrorist and my transition saved my life. Retrieved from https://thebodyisnotanapology.com/magazine/i-was-my-own-body-terrorist-and-my-transition-saved-my-life/

- Galupo, M. P., Pulice-Farrow, L., & Lindley, L. (2020). “Every time I get gendered male, I feel a pain in my chest”: Understanding the social context for gender dysphoria. Stigma and Health, 5(2), 199–208. doi:10.1037/sah0000189

- Gamarel, K. E., Reisner, S. L., Laurence, J-P., Nemoto, T., & Operario, D. (2014). Gender minority stress, mental health, and relationship quality: A dyadic investigation of transgender women and their cisgender male partners. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(4), 437–447. doi:10.1037/a0037171

- Gamarel, K. E., Sevelius, J. M., Reisner, S. L., Coats, C. S., Nemoto, T., & Operario, D. (2019). Commitment, interpersonal stigma, and mental health in romantic relationships between transgender women and cisgender male partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(7), 2180–2201. doi:10.1177/0265407518785768

- Gavey, N (2005). Just sex? The cultural scaffolding of rape. London: Routledge.

- Gorin-Lazard, A., Baumstarck, K., Boyer, L., Maquigneau, A., Penochet, J-C., Albarel, F., Morange, I., Bonierbale, M., Lançon, C., & Auguier, P. E. (2013). Hormonal therapy is associated with better self-esteem, mood and quality of life in transsexuals. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(11), 996–1000 doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000046

- Gunn, A., Hoskin, R. A., & Blair, K. L. (2021). The new lesbian aesthetic? Exploring gender style among femme, butch and androgynous sexual minority women. Women’s Studies International Forum, 88, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102504

- Handler, T. J., Hojilla, C., Varghese, R., Wellenstein, W., Satre, D. D., & Zaritsky, E. (2019). Trends in referrals to a pediatric transgender clinic. Paediatrics, 144(5), e20191368. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1368

- Harrison, N., Jacobs, L., & Parke, A. (2020). Understanding the lived experiences of transitioning adults with gender dysphoria in the United Kingdom: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Jounral of LGBT issues in Counselling, 14(1), 38–55. doi:10.1080/15538605.2020.1711292

- Holloway, W. (1984). Gender difference and the production of subjectivity. In J. Henrques (Ed.), Changing the subject: Psychology, social regulation and subjectivity. London: Routledge, p. 227–263.

- Johnson, A. H. (2016). Transnormativity: A new concept and its validation through documentary film about transgender men. Sociological Inquiry, 86(4), 465–491. doi:10.1111/soin.12127

- Johnson, K. (2015). Sexuality. A psychosocial manifesto. Cambridge: Polity.

- *Joslin-Roher, E., & Wheeler, D. P. (2009). Partners in transition: The transition experience of lesbian, bisexual, and queer identified partners of transgender men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 21(1), 30–48. doi:10.1080/10538720802494743

- Karpel, L., & Cordier, B. (2013). Postoperative regrets after sex reassignment surgery: A case report. Sexologies, 22(2), 55–58. doi:10.1016/j.sexol.2012.08.014

- Keener, E., Mehta, C. M., & Smirles, K. E. (2017). Contextualizing Bem: The developmental social psychology of masculinity and femininity. In M. Kohlman, D. Balsink Krieg, & M. Kohlman (Eds.), Discourses on gender and sexual inequality: The legacy of Sandra L. Bem, Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, p. 1–17.

- Langer, S. J., & Martin, J. I. (2004). How dresses can make you mentally ill: Examining gender identity disorder in children. Child and Adolescent Social Work, 21(1), 5–22.

- Lewins, F. (2002). Explaining stable partnerships among FTMs and MTFs: A significant difference? Journal of Sociology, 38(1), 76–88. doi:10.1177/144078302128756507

- Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objective and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemiologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 1–20.

- Marshall, E., Glazebrook, C., Robbins-Cherry, S., Nicholson, S., Thorne, N., & Arcelus, J. (2020). The quality and satisfaction of romantic relationships in transgender people: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(4), 373–390. Doi: 10.1080/2689.2020.1765446

- Meier, S. C., Sharp, C., Michonski, J., Babcock, J. C., & Fitzgerald, K. (2013). Romantic relationships of female-to-male trans men: A descriptive study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 14(2), 75–85. doi:10.1080/15532739.2013.791651

- Meyerowitz J. (2002). How sex changed: A history of transsexuality in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D.G. (2009). PRISMA group: preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(7), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moore, I., Morgan, G., Russell, G., & Welham, A. (2022). The intersection of autism and gender in the negotiation of identity: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Feminism & Psychology. doi:10.1177/09593535221074806

- Moradi, B., Tebbe, E., Brewster, M. E., Budge, S. L., Lenzen, A., Ege, E., … Flores, M. J. (2016). A content analysis of literature on trans people and issues: 2002–2012. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(7), 960–995. doi:10.1177/0011000015609044

- Moran, C. (2017). Re-positioning female heterosexuality within postfeminist and neoliberal culture. Sexualities, 20(1–2), 121–139. doi:10.1177/1363460716649335

- Nagoshi, J. L., Brzuzy, S., & Terrell, H. K. (2012). Deconstructing the complex perceptions of gender roles, gender identity, and sexual orientation among transgender individuals. Feminism & Psychology, 22(4), 405–422. doi:10.1177/0959353512461929

- Nieder, T. O., Eyssel, J., & Köhler, A. (2020). Being trans without medical transition: Exploring characteristics of trans individuals from Germany not seeking gender-affirmative medical interventions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 2661–2672. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-01559-z

- Nolan, I. T., Kuhner, C. J., & Dy, G. W. (2019). Demographic and temporal trends in transgender identities and gender confirming surgery. Translational Andrology and Urology, 8(3), 184–190. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.04.09

- Pilgrim, D. (2021). Transgender debates and healthcare: A critical realist account. Health. doi:10.1177/13634593211046840

- *Platt, L. F., & Bolland, K. S. (2018). Trans* partner relationships: A qualitative exploration. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13(2), 163–185. doi:10.1080/1550428X.2016.1195713

- Reilly-Cooper, R. (2016, June 28). Gender is not a spectrum. Aeon essays. Retrieved from https://aeon.co/essays/the-idea-that-gender-is-a-spectrum-is-a-new-gender-prison

- Richards, C., & Doyle, J. (2019). Detransition rates in a large national gender identity clinic in the UK. Counselling Psychology Review, 34(1), 60–66.

- Rogers, A. A., Nielson, M. G., & Santos, C. E. (2021). Manning up while growing up: A developmental-contextual perspective on masculine gender-role socialization in adolescence. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 22(2), 354–364. doi:10.1037/men0000296

- Schippers, M. (2007). Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity and gender hegemony. Theory and Society, 36(1), 85–102 doi:10.1007/s11186-007-9022-4

- Schleifer, D. (2006). Make me feel mighty real: Gay female-to-male transgenderists negotiating sex, gender, and sexuality. Sexualities, 9(1), 57–75. doi:10.1177/1363460706058397

- Slater, S., & Mencher, J. (1991). The lesbian family life cycle: A contextual approach. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61(3), 372–382. doi:10.1037/h0079262

- Spencer, K. G., Berg, D. R., Bradford, N. J., Vencill, J. A., Tellawi, G., Rider, G. N. (2021). The gender-affirmative life span approach: A developmental model for clinical work with transgender and gender-diverse children, adolescents and adults. Psychotherapy (Chic), 58(1), 37–49. doi:10.1037/pst0000363

- Summersell, J. (2018). The transgender controversy: Second response to pilgrim. Journal of Critical Realism, 17(5), 529–545, doi:10.1080/14767430.2018.1555347

- Stock, K. (2021). Material girls: Why reality matters for feminism. UK: Fleet.

- Theron, L., & Collier, K. L. (2013). Experiences of masculine identifying trans persons. Culture Health and Sexuality, 15(0), 62–75. doi:10.108/13691058.2013.788214

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45), 10–45. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- *Thurston, M. D., & Allan, S. (2018). Sexuality and sexual experiences during gender transition: A thematic synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.008

- van de Grift, T. C., Elaut, E., Cerwenka, S. C., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Kruekels, B. P. C. (2018). Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming surgery: A follow-up study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 138–148. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1326190

- Wiepjes, C. M., Nota, N. M., de Blok, C. J. M., Klaver, M., de Vries, A. L. C., Wensing-Kruger, A., … Heijer, M. (2018). The Amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria study (1972-2015): Trends in prevalence, treatment, and regrets.The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(4), 582–590. Doi: 10.1016/j/jsxm/2018/016

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people [7th Version]. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc

- Wren, B. (2014). Thinking postmodern and practising in the enlightenment: Managing uncertainty in the treatment of children and adolescents. Feminism & Psychology, 24(2), 271–292: doi:10.1177/0959353514526223

- Wynn, A., & Pemberton, A. (2021, November 23). Changing gender saved my life says Greater Manchester prison officer. Retrieved from https://www.manchesterworld.uk/news/changing-gender-saved-my-life-says-greater-manchester-prison-officer-3467888