Abstract

Despite some efforts to enhance clitoral knowledge to increase women’s sexual pleasure, a gendered orgasm gap persists. We aimed to provide contemporary data on people’s knowledge about the clitoris and investigate its association with the experience of sexual pleasure. Heterosexual participants (n = 573; 64.2% women) took a quiz on clitoral knowledge and answered sexuality-related questions. Participants answered only 50% of the nine quiz items correctly. Clitoral knowledge predicted sexual pleasure and orgasm in women, mediated via reduced endorsement of gendered sexual scripts. Our results highlight the importance of clitoral knowledge and its interplay with societal barriers for the experience of pleasure.

Introduction

The clitoris is central to female sexual pleasure and orgasm (e.g., Armstrong, England, & Fogarty, Citation2012; Herbenick, Fu, Arter, Sanders, & Dodge, Citation2018). So, it comes with no surprise that sexual practices involving the clitoris—such as cunnilingus and manual stimulation—have been shown to reliably increase sexual pleasure and orgasm in women. In contrast, from an anatomical perspective penile vaginal intercourse (PVI) is a reliable route to orgasm for men, but not for women (for a review see Conley & Klein, Citation2022; Laan et al., Citation2021).

Recently, efforts have increased to enhance women’s clitoral knowledge, hoping that sexual pleasure and orgasm experience will follow. For instance, clitoral focus of sex toys and easier access to them, feminist sex-shops, queer feminist porn, feminist literature, plattforms such as OMGyes, podcasts and cliteracy campaigns have publicly stressed the importance of clitoral stimulation for women’s sexual pleasure and orgasm (Guitelman, Mahar, Mintz, & Dodd, Citation2019; Hensel et al., Citation2022). Despite these efforts to integrate clitoral knowledge into women’s sex lives, a discrepancy of orgasm frequency between genders persists, showing that women experience 20–49,9% fewer orgasms than men in heterosexual encounters (see Mahar et. al, 2020 for a review). Additionally, looking beyond the orgasm itself to the broader experience of sexual pleasure, women also report enjoying sexual encounters less than their male counterparts (Herbenick et al., Citation2010; Ogletree & Ginsburg, Citation2000)Footnote1.

Does a clitoral knowledge deficit persist?

Past and recent research has shown that biological explanations may not provide sufficient reason for the systematic differences in orgasm and sexual pleasure experiences between heterosexual women and men (Armstrong et al., Citation2012; Blair, Cappell, & Pukall, Citation2018; Klein & Conley, Citation2021; see Mahar, Mintz, & Akers, Citation2020 for a review). Women and men may not differ in their biological “capacity” to orgasm; when masturbating women and men reach orgasms in a similar time frame (Kinsey, Citation1953). Women are also capable of experiencing multiple orgasms in a short period of time without a refractory period (Gérard et al., Citation2020; Hite, Citation1979; Kinsey, Citation1953; Masters & Johnson, Citation1966). Moreover, women’s ability to orgasm is increased when comparing women who have sex with women to women who have sex with men (86% vs. 65%, Frederick, St. John, Garcia, & Lloyd, Citation2018). These differences in orgasm rates may be explained by the fact that women who have sex with women are more likely to integrate sexual practices that include a direct stimulation of the clitoris into their sexual encounters (Frederick et al., Citation2018).

One potential barrier for overcoming the gendered orgasm gap might therefore consist in a lack of anatomical or more specifically—clitoral knowledge and its application in heterosexual encounters. Supporting this assumption empirical evidence from bibliotherapy interventions and online sex education show that clitoral knowledge is a source to enhance sexual pleasure in women (Guitelman et al., Citation2019; Hensel et al., Citation2022).

But what role does a lack of clitoral knowledge (still) play in the maintenance of gender inequality in orgasm rates? More than a decade ago, Wade and her colleagues (2005) investigated the link between clitoral knowledge and orgasm experience in women. In their study clitoral knowledge, the sources of their knowledge and its relationship to various sexual outcome variables were assessed among college students. Results indicated that women and men showed similar error rates when having to spot the clitoris on a vulva diagram (29% vs. 25%). The fact that almost one third of women could not locate the clitoris was explained by the relatively low number of women (52.4%) reporting self-exploration as an important source of their knowledge. Findings further showed that women’s clitoral knowledge enhanced orgasm rates during masturbation, but not during partnered sex. Women never orgasming during partnered sex had orgasms during masturbation at the same rate as women who often orgasmed during partnered sex. Hence, clitoral knowledge seems to have an influence on orgasms in masturbation, but not for orgasm experiences during heterosexual partnered sex. The authors concluded that there seem to be cultural forces hindering the translation of positive knowledge effects visible in the context of solo sex to the context of heterosexual partnered sex. We continue this argument, focusing on gendered sexual scripts as part of a heteronormative system which hinders a self-determined and pleasure-oriented sexuality for women, especially in heterosexual encounters.

Gendered sexual scripts

Gendered sexual scripts might be an important sociocultural barrier to knowledge, as those scripts prioritize male sexual pleasure. More precisely, those culturally shared scripts ascribe high sexual desire, orgasm, dominance, and initiative to men, whereas women are expected to show passivity, low desire, and less interest in orgasms (Bowleg et al., Citation2015; Klein, Imhoff, Reininger, & Briken, Citation2019; Rubin et al., Citation2019; Sakaluk, Todd, Milhausen, & Lachowsky, Citation2014; Wiederman, Citation2005; Willis, Jozkowski, Lo, & Sanders, Citation2018). Moreover, specific gendered scripts about orgasms claim the male orgasm to be less complicated than the female one (Butler, Citation2011; Opperman, Braun, Clarke, & Rogers, Citation2014) and ascribe men a biological stronger need for orgasm than women (Bell & McClelland, Citation2018; Conley, Moors, Matsick, Ziegler, & Valentine, Citation2011; Sakaluk et al., Citation2014). Recent evidence supports the persistence of gendered sexual scripts that subordinate women’s sexual pleasure to men’s: Participants, if forced to decide, would rather give an orgasm to a man than to a woman (Klein & Conley, Citation2021).

Importantly, gendered sexual scripts can serve as a safeguard in unknown sexual situations (Klein et al., Citation2019). If these gendered sexual scripts are internalized, they might get “activated” during heterosex and make clitoral knowledge and its application irrelevant and consequently undermine women’s orgasm experiences. This might explain why women’s clitoral knowledge does not translate into orgasm in partnered sex.

The above-mentioned confusion of socially constructed gendered sexual scripts with alleged “biological facts” maintain a misconception about the capacity and desire for sexual pleasure in women compared to men—hence sustaining fertile soil for the pleasure gap to persist. Scholars who have started to challenge those misconceptions by critically reflecting the orgasm gap in literature or university courses and providing clitoral knowledge to female university students found that these women improved from pre- to post-test in variables such as orgasm experience and achieving sexual pleasure (Guitelman et al., Citation2019; Warshowsky, Mahar et al., Citation2020). Given the negative impact of internalized gendered sexual scripts on female sexual pleasure (Kiefer & Sanchez, Citation2007; Rubin et al., Citation2019; Sanchez, Kiefer, & Ybarra, Citation2006; Sanchez, Fetterolf, & Rudman, Citation2012) and the promising results for women’s sexuality of systematically challenging these scripts (Guitelman et al., Citation2019; Warshowsky, Mahar et al., Citation2020), we aimed to investigate gendered sexual scripts as a potential socio-cultural barrier regarding the application of clitoral knowledge in heterosexual settings. If women have more knowledge about the clitoris, female orgasm, and sexual pleasure, they may be less likely to endorse gendered sexual scripts and hence be more likely to act on their clitoral knowledge—not only in solo sex but also in partnered sex.

The present research

Expanding the previous literature, the study aims were twofold. First, we aimed to examine whether clitoral knowledge has become more prevalent considering the - supposedly - changing social climate that seems to put more emphasize on female sexual pleasure. Since the study by Wade, Kremer, and Brown (Citation2005) is to date the only one examining the relationship between clitoral knowledge and orgasm, we aimed to reanalyze this association over fifteen years after the original study. In line with Wade’s (Citation2005) study we predicted that clitoral knowledge will be positively associated with orgasm in the context of solitary masturbation but not with orgasm while having sex with their partner. Second, we aimed to examine the role of gendered sexual scripts as a potential socio-cultural barrier, hindering clitoral knowledge to be applied in heterosexual encounters. While this association has been theoretically discussed, it has not been empirically tested so far. To fill this gap, we specifically tested the hypothesis that gendered sexual scripts might be a mediator in the relationship between clitoral knowledge and orgasm/sexual pleasure for women.

Moreover, in contrast to the Wade study (2005) that included a student population, we aimed to investigate clitoral knowledge in a more diverse socio-demographic sample. This allows to explore whether clitoral knowledge is higher in populations with potential access to new feminist inputs (e.g., college students) or can be counted as widespread knowledge. Because orgasm can be an important aspect of sexual pleasure but does not necessary cover all aspects, we additionally considered sexual pleasure as a variable in our analysis (Goldey, Posh, Bell, & van Anders, Citation2016; Opperman et al., Citation2014; Pascoal, Narciso, & Pereira, Citation2014).

In our study we focused on the sexual experiences of heterosexual cis gender women and men for two reasons. First, research on the orgasm gap provides evidence that the biggest gap in orgasm experiences exists between heterosexual women and men (Frederick et al., Citation2018). Second, the academic literature on sexual scripts is mainly concentrated on cisgender women and men, since traditional sexual scripts follow a heteronormative pattern (Sanchez et al., Citation2012; Wiederman, Citation2005). Our main analysis focused solely on women, because only for women not for men, we hypothesize that higher clitoral knowledge will lead to more orgasm or pleasure experience via reduced gendered sexual scripts. Gaining a holistic picture, we included men on an exploratory level in our analysis.

Methods

Participants

To detect a small-sized effect, an a priori power analysis, for a mediation analyses (Baltes-Götz, Citation2020), revealed that 311 participants will be needed to achieve 80% test power at α =.05.

In total, 681 individuals completed the survey. Because this study focused on heterosexual and cis-identified participants only, we excluded 105 people who did not identify as heterosexual and three additional participants who identified as gender diverse. The final sample included 573 individuals (368 women, 64,22%). Participants mean age was 28.50 years (SD = 8.00; range 18-68 years). Regarding their education background 8.6% reported having a secondary school diploma, 25.1% a high school diploma, and 66.3% a university or college degree. Most participants were in a relationship at the time of data collection (73.8%), and 26.2% were single.

Procedure

Participants were recruited via a snowball procedure. Research assistants shared the survey link over listservs, on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), and recruited participants directly. Additionally, recipients of the survey link were asked to share it with their networks. After providing informed consent, participants were asked to fill out an online survey. The survey consisted of two parts: a 9-nine-item quiz on clitoral knowledge and items addressing participants’ sex lives, which were presented in randomized order. After completing the survey, participants were debriefed and provided with detailed information about the research question as well as with the correct quiz answers. Data are available at https://osf.io/a3d6g/

Measures

Independent variable

Clitoral knowledge

To develop an engaging, participant friendly quiz in a first step the authors created and evaluated the quiz items. To help establish content validity, all quiz items were evaluated by sexual health professionals who were invited to evaluate the rationally derived quiz item pool. The professional evaluators included clinical psychologists and researchers with expertise in sexuality health. Recommendations regarding relevance, clarity, brevity, and singularity of quiz items were given. Based on evaluators’ feedback the quiz was integrated before proceeding with the data collection.

The final quiz consisted of nine questions that measured clitoral knowledge. These items reflect misconception of the clitoral anatomy and its role for orgasm experiences e.g. The clitoris erects when it receives increased blood flow (e.g., during sexual arousal). The response format of the quiz was adapted from the clitoral knowledge measure used by Wade et al. (Citation2005). In six cases, the answer format consisted of three options: true, false and honestly, I would have to guess. Three questions of the quiz (e.g., Which sexual practice is the most reliable source for women’s orgasm?) included content-based answers (e.g., oral sex; penile-vaginal intercourse; anal sex) and the option Honestly, I would have to guess. One point was given for correct answers and zero points for incorrect answers or the answer Honestly, I would have to guess. These quiz items were then combined into a quiz score, with higher numbers indicating greater clitoral knowledge.

Dependent variables

Sexual pleasure

Sexual pleasure was assessed using seven items from the Amsterdam Pleasure Index, which has shown acceptable to excellent psychometric qualities (Werner, van Lunsen, Gaasterland, Bloemendaal, & Laan, Citation2022). This short version has been used in previous research and showed good internal consistency (Klein, Laan, Brunner, & Briken, Citation2022). The measurement mostly focuses on shared sexual experiences with a partner, and participants reported their perceptions of how much pleasure they get from sexual acts (e.g., I enjoy it when my body reacts to sexual stimuli.). Using a 5-point scale, items were rated from totally disagree to totally agree. These items were combined into a pleasure scale, with higher scores indicating greater pleasure (α = .81).

Orgasm rate in partnered sexual activity

Participants were presented with the following question: In general, how often do the following behaviors occur during your sexual encounter? and the following answer option Having an orgasm. Orgasm rate during sex with another person was then assessed on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never to always (Frederick et al., Citation2018).

Orgasm rate in masturbation

Orgasm rate during masturbation was measured on a 5-point Likert scale with the following item: Now think about your experiences with orgasm in the last month. How often did you have an orgasm when masturbating? The response format ranged again from never to always. Participants could also choose the option I don’t have this type of sex.

Orgasm related gendered sexual scripts

To measure gendered sexual scripts related to sex and orgasm, participants answered four items which we adapted from Rubin et al., Citation2019. Participants answered the items (e.g., It is more important for men compared to women to have an orgasm) on a 6-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. These four items were combined into a gendered sexual scripts scale, with higher numbers indicating greater agreement with gendered cultural scripts about orgasms (α = .67).

Statistical analysis

T-tests for independent samples were calculated to assess gender differences in quiz scores. In addition, to examine differences between women and men on individual quiz items, chi-square tests (χ2-tests) were conducted. Furthermore, as in previous studies (see Mahar et al., Citation2020), orgasm rates were presented in % to allow for comparability to other studies. Analogous to Frederick et al. (Citation2018), responses were divided into three categories for this purpose (never_rarely, half of the time, usually_always) and significant differences between women and men were calculated for each category using χ2-tests.

The respective associations between clitoral knowledge, gendered sexual scripts, and sexual pleasure and orgasm were calculated via mediation analyses with the PROCESS macro as suggested by Hayes (Citation2018) for women and men, respectively. To calculate the inferential statistics, bootstrapping with 10 000 samples was applied. A mediation effect was described as present if the indirect effect was significant, regardless of whether there was a total effect. For this reason, mediation analyses that included bivariate regressions between variables were calculated directly. This procedure is based on the recommendations of Zhao, Lynch, and Chen (Citation2010) and Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, and Petty (Citation2011), who advocate interpreting indirect effects alone. The size of the indirect effect was determined according to Cohen (Citation1988).

Results

The bivariate correlations of all variables can be traced in for women and men respectively.

Table 1. Bivariate correlations of all variables for women (left of diagonal) and men (right of diagonal).

Clitoral knowledge

On average participants answered 4.56 (SD = 1.84) out of the 9 items correctly, corresponding to a successful response rate of approximately 50%. Furthermore, women (M = 4.77, SD = 1.84) answered significantly more items correctly than men (M = 4.18, SD = 1.77), t(571) = 3.76, p <.001, d = 0.33, 95% CI [0.28, 0.91]. The proportion of correct answers per quiz item for both genders is shown in .

Table 2. Proportion of correct answers in the clitoral knowledge quiz for women and men.

Considering demographic factors, we did not find any significant relationships between age and clitoral knowledge, neither for women, r(366) = −.06, p = .260, nor for men, r(203) = .10, p = .149. However, for women a one-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of education on clitoral knowledge, F(2, 365) = 5.43, p = .005. Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc analysis indicated that participants with secondary school diplomas had significantly lower clitoral knowledge (M = 3.55, SD = 1.60) compared to participants with high-school diplomas (M = 4.76, SD = 1.74, p = .016) and participants with university degrees (M = 4.88, SD = 1.87, p = .003). For men, the education level showed no significant effect on clitoral knowledge, F(2, 202) = 0.06, p = .944.

Sexual outcome variables

We identified gender differences in orgasm rates. There was a significant difference between gender and orgasm rate χ2(1) = 74.01, p<.001, φ = 0.36, indicating that women were significantly less likely to usually or always experience orgasm during partnered sex in comparison to men (56.5% vs. 91.2%). We did not identify significant differences between women and men usually or always orgasming during masturbation χ2(1) = 1.07, p = .30 (91.7% vs. 94%, n.s.). Gender differences in the dependent variables are presented in . Women in our sample reported significantly less sexual pleasure compared to men. Finally, women and men did not significantly differ in their endorsement of gendered sexual scripts.

Table 3. T-tests results comparing women and men.

Mediation analyses

The following analyses were conducted with the subsample of 368 women.

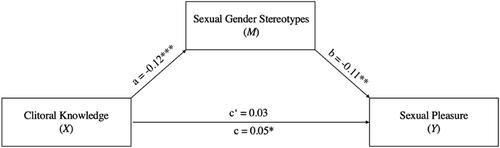

Sexual pleasure

The total effect of clitoral knowledge on sexual pleasure was significant, B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, t(366) = 2.20, p = .029, 95% CI [0.00, 0.09]. Clitoral knowledge was negatively related to gendered sexual scripts, B = −0.12, SE = 0.03, t(366) = −4.29, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.18, −0.07]. Gendered sexual scripts were, in turn, negatively related to sexual pleasure, B = −0.11, SE = 0.04, t(366) = −2.94, p = .003, 95% CI [-0.19, −0.04]. When the mediator was entered into the model, the total effect of clitoral knowledge on sexual pleasure was reduced to a non-significant direct effect, showing a mediation, B = 0.03, SE = 0.02, t(366) = 1.46, p = .146, 95% CI [-0.01, 0.07]. The positive effect of clitoral knowledge on sexual pleasure was mediated via reduced gendered sexual scripts endorsement, B = .01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.03], ccs= 0.04, 95% CI for ccs[0.01, 0.07]. The results are shown in

Figure 1. The mediating effect of gendered sexual scripts in the relationship between clitoral knowledge and sexual pleasure for women.

Note. All presented effects are unstandardized. c’ is the direct effect of clitoral knowledge on sexual pleasure. c is the total effect of clitoral knowledge on sexual pleasure. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

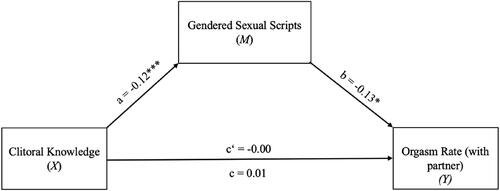

Orgasm rate in partnered sexual activity

Neither the total effect of clitoral knowledge on the orgasm rate in partnered sex, B = 0.01, SE = 0.03, t(366) = 0.42, p = .677, 95% CI [-0.04, 0.07], nor the direct effect, B = −0.00, SE = 0.03, t(366) = −0.09, p = .926, 95% CI [-0.06, 0.06], were significant. However, an indirect effect via gendered sexual scripts was found. Clitoral knowledge was significantly negatively related to gendered sexual scripts, B = −0.12, SE = 0.03, t(366) = −4.29, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.18, −0.07]. Furthermore, the endorsement of gendered sexual scripts was negatively associated with the orgasm rate in partnered sexual activity, B = −0.13, SE = 0.05, t(366) = −2.37, p = .018, 95% CI [-0.23, −0.02]. The effect of clitoral knowledge on the orgasm rate in partnered sex was mediated via reduced endorsement of gendered sexual scripts, B = .02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.03], ccs= 0.03, 95% CI for ccs[0.00, 0.06] (see ).

Figure 2. The mediating effect of gendered sexual scripts in the relationship between clitoral knowledge and orgasm rate in partnered sexual activity for women.

Note. All presented effects are unstandardized. c’ is the direct effect of clitoral knowledge on orgasm rate (with partner). c is the total effect of clitoral knowledge on orgasm rate (with partner). * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

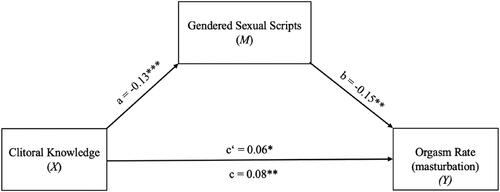

Orgasm rate in masturbation

The total effect of clitoral knowledge on the orgasm rate in masturbation was significant, B = 0.08, SE = 0.03, t(347) = 3.07, p = .002, 95% CI [0.03, 0.13]. Again, clitoral knowledge showed a negative relation to gendered sexual scripts, B = −0.13, SE = 0.03, t(347) = −4.50, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.19, −0.07]. In turn, gendered sexual scripts were negatively associated with orgasm masturbation rate, B = −0.15, SE = 0.05, t(347) = −3.21, p = .002, 95% CI [-0.24, −0.06]. When entering the mediator into the model the total effect of clitoral knowledge on masturbation orgasm rate reduced but remained significant, B = 0.06, SE = 0.03, t(347) = 2.32, p = .021, 95% CI [0.01, 0.11]. The indirect mediation effect was significant, B = .02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.04], ccs= 0.04, 95% CI for ccs[0.01, 0.07] (see ).

Figure 3. The mediating effect of gendered sexual scripts in the relationship between clitoral knowledge and orgasm rate in masturbation for women.

Note. All presented effects are unstandardized. c’ is the direct effect of clitoral knowledge on orgasm rate (masturbation). c is the total effect of clitoral knowledge on orgasm rate (masturbation).* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Exploratory analysis: male sample

Looking at the male participants, concerning sexual pleasure and orgasm rate in masturbation, none of the path coefficients in the mediation models reached significance. However, for orgasm rate in partnered sexual activity we found marginally significant relationships between endorsement of gendered sexual scripts and orgasm rate, B = 0.11, SE = 0.06, t(203) = 1.75 p = .082, 95% CI [-0.01, 0.24] as well as between clitoral knowledge and orgasm rate both through the direct, B = −0.06, SE = 0.03, t(203) = −1.77, p = .078, 95% CI [-0.12, 0.01] as well as the indirect path, B = −0.06, SE = 0.03, t(203) = −1.78, p = .076, 95% CI [-0.12, 0.01]. However, there was no mediating effect, as the relationship between clitoral knowledge and gendered sexual scripts remained insignificant, B = 0.01, SE = 0.04, t(203) = 0.16, p = .874, 95% CI [-0.07, 0.08].

Discussion

This present study aimed to provide contemporary data on people’s knowledge about the clitoris and its effect on female sexual pleasure and orgasm, as well as analyzing the role of gendered sexual scripts as a possible barrier of knowledge application.

Clitoral knowledge

Our results show that large knowledge gaps concerning the clitoris persist for both women and men. On average, participants answered only 50% (4.5 out of 9) of the quiz items correctly, whereas the correct response rate in Wades study was around 60%. Since we did not use the same questions as Wade et. al (2005) and data was collected in a different cultural context, comparability is limited. Nevertheless, our results indicate that there seems to be no increase in clitoral knowledge over time. We did not find any relationship between age and clitoral knowledge. However, for women a higher school degree was related to more knowledge, pointing to the relevance of education rather than life-experience for this specific knowledge domain. This result is not surprising considering that from a historical perspective, multiple sources have created barriers to knowledge about women’s sexual pleasure and associated pleasure organs (Ogletree & Ginsburg, Citation2000; Tuana, Citation2004). For instance, it wasn’t until 1998 that detailed information about the anatomy and physiology of the female clitoral complex came to light (O’Connell, Hutson, Anderson, & Plenter, Citation1998). In the same vein, textbooks predominantly do not mention the clitoris (Ogletree & Ginsburg, Citation2000) and school sex education widely lacks pleasure-oriented approaches (Ampatzidis, Georgakopoulou, & Kapsi, Citation2021; Koepsel, Citation2016). These social-cultural forces that restrict women’s sexual pleasure by obscuring knowledge seem to have an impact on peoples’ sexuality and knowledge up to the present day.

The role of gendered sexual scripts

As predicted for women, more clitoral knowledge was associated with endorsing less gendered sexual scripts, which in turn showed a positive association with higher pleasure and orgasms experience. Looking closer at the statistical paths, we found a difference between partnered sex and masturbation. Whereas clitoral knowledge showed no direct association with orgasm in partnered sex, it showed a direct effect on orgasm in masturbation practice. Hence, clitoral knowledge seems to help experience orgasm in solo sex but taken alone is not sufficient to facilitate orgasm in partnered heterosex. Wade et al. (Citation2005) found a similar pattern and argued that the translation of clitoral knowledge in a heterosexual setting might be hindered by sociocultural barriers, which undermine sexual autonomy for women. Consequently, women might not feel entitled to ask for the (clitoral) stimulation they might need to experience sexual pleasure (Satinsky & Jozkowski, Citation2015). The results of the present study support the assumption of gendered sexual scripts as a sociocultural barrier mediating whether women experience orgasms or not. Furthermore, our results align with earlier research showing a negative impact of gendered sexual scripts on women’s sexual pleasure and orgasm experience (Kiefer & Sanchez, Citation2007; Rubin et al., Citation2019; Sanchez et al., Citation2006; Sanchez et al., Citation2012). Gendered sexual scripts might act as sociocultural barriers hindering sexual pleasure and orgasm in two ways. First, internalized gendered sexual scripts might hinder women to apply their clitoral knowledge in a heterosexual encounter (Wade et al., Citation2005; Sanchez et al., Citation2012). Second, considering missing solid clitoral knowledge, these gendered sexual scripts might be taken for actual sexual knowledge, thus legitimating gender roles in traditional sexual scripts that prioritize men’s pleasure over women’s (Mahar et al., Citation2020; Sanchez et al., Citation2012; Wiederman, Citation2005). For a detailed overview on potential interventions that portray women and men contrary to their stereotypical gender roles in order to reduce internalized gendered sexual scripts see Sanchez and her colleagues (2012).

The exploratory results of the male sub-sample should be handled with caution due to marginally significant results. However, results tentatively indicate that greater clitoral knowledge is negatively related to men’s orgasm experience in partnered sex. This could be because men who are interested in female pleasure-related knowledge also prioritize their partner’s orgasm.

Practical implications

Our findings have significant implications for counseling and sex education. First, we introduced the clitoral knowledge quiz as a valuable instrument that can be used in both clinical and psychoeducational practice (e.g., clients with sexual problems). The quiz is suitable to identify a knowledge deficit as well as to provide sexuality-related knowledge in a playful way. Second, our results point to the need of a broader implementation of biological (especially clitoris related) and pleasure-based sexual knowledge for all genders in sex education. Sex education has been shown to increase women’s anatomical knowledge, self-efficacy to experience sexual pleasure, and positive attitudes toward their bodies (Edwards, Citation2016; Guitelman et al., Citation2019) as well as enhance heterosexual men’s sexuality-related knowledge (Warshowsky, Mahar et al., Citation2020). Other sources like educational videos on YouTube (Döring, Citation2017), e-learning platforms like OMGyes (www.OMGyes.com), or science podcasts (e.g., Morse, Citation2005), and even graphic novels (e.g., Strömquist, Citation2017) could be useful additions in enhancing clitoral knowledge which also have the potential to reach people who do not receive sex education in schools and/or are not part of the education system. To prevent an orgasm or pleasure imperative, practical approaches to enhance pleasure should be served as a buffet of options individuals are invited to choose or equally restrain from (Fahs, Citation2014; Wood, Hirst, Wilson, & Burns O’Connell, Citation2018).

Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations to the present study. Due to its cross-sectional design the study does not allow for causal inferences regarding the direction of effect of the variables knowledge, gendered sexual scripts, sexual pleasure, and orgasm rates. Especially applying mediation analysis to cross-sectional data needs critical reflection and theoretical arguments to support the temporal ordering of variables (Fairchild & McDaniel, Citation2017). Our ordering was based on the ideas expressed by Wade et al. (Citation2005) of socio-cultural barriers standing between knowledge and its application. It entails the idea that clitoral knowledge is necessary to alter sexual gendered scripts. Future research could shed more light on causal associations through longitudinal studies (e.g., Warshowsky, Della Mosley, Mahar, & Mintz, Citation2020), and possibly establish more comprehensive effect models regarding additional sociocultural barriers such as body image or the cultural overvaluation of penetrative sex (see Guitelman et al., Citation2019) in the context of clitoral knowledge.

A further limitation is the heteronormative focus of our study. Given that studies have primarily found higher rates of orgasm among lesbian (vs. heterosexual) women (Frederick et al., Citation2018), it would be interesting to examine clitoral knowledge levels and endorsement of gendered sexual scripts among more diverse study populations to provide further insight into the interplay between clitoral and sexual pleasure. Additionally, it would be interesting to specifically examine dyadic effects of knowledge and gendered sexual scripts using a larger sample of couples. In this context the exploratory mediation analysis of men—even though not showing any significant results - might serve as a starting point for dyadic future investigation: What role does men’s endorsement of gendered sexual scripts and clitoral knowledge have on their female partners sexual pleasure and orgasm? How does higher clitoral knowledge and less endorsement of traditional scripts affect heterosexual men’s own orgasm experience?

In addition, the relationship of mass media consumption (e.g., series) and pornography on sexual knowledge and gendered sexual scripts would be an interesting venue for future research. Content analyses have shown that mainstream pornography reproduces significantly more traditional sexual scripts and portrays women more often as sex objects compared to feminist pornography (Fritz & Paul, Citation2017). Feminist pornography, on the other hand, contains more acts that depict sexual agency and sexual pleasure for women (Fritz & Paul, Citation2017). Regarding the different sexual scripts of different pornography genres, it would be particularly interesting to investigate whether consumers of sex-positive, feminist, or queer content differ from consumers of mainstream pornography in terms of their clitoral knowledge and gendered sexual script endorsement. Initial evidence is provided by findings that have shown a positive effect of feminist non-pornographic content on sexual self-efficacy (Edwards, Citation2016; Guitelman et al., Citation2019).

Lastly, it would be insightful to explore further influential factors of clitoral knowledge. Our study showed that a higher educational background was related to more knowledge among women, but not men. However, there are many other conceivable factors like political orientation, feminist values or religious views that may play a role in accessing and gaining this knowledge.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that clitoral knowledge is still limited among women and men which in turn influences women’s sexual pleasure. The orgasm gap and strategies to close it have been discussed in the academic literature and as part of the women’s movement since the 1960s (Döring & Mohseni, Citation2022). The current empirical evidence, which indicates that the orgasm gap persists, calls into question the success of past efforts to achieve orgasm equality (Döring & Mohseni, Citation2022). To address these personal (e.g.: women and men gaining more knowledge about the clitoris) and societal factors (e.g.: overcoming societal gender roles) with interventions is not completely new, as they partially have been debated for more than three decades (e.g.: Ehrenreich, Hess, & Jacobs, Citation1987), questioning their feasibility. That said, there is a need to critically assess the opportunities and limitations of the above-mentioned practical implications for pleasure equality. What hinders outdated sex education to change? What part does the deprioritization of sexual pleasure on a societal level play? Why are gendered sexual scripts so enduring? Although we are unable to answer these complex questions, the study results point to the influence of sociocultural barriers on the application of knowledge, thus contributing to a better understanding of possible mechanisms of action.

Declarations of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

Data are available at https://osf.io/a3d6g/

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Findings on the orgasm gap show systematic differences in sexual pleasure and orgasm experience, with the mechanisms of these discrepancies operating primarily in heterosexual contexts. Therefore, this study focuses on heterosexually identifying cis women and cis men - henceforth referred to as women and men.

References

- Ampatzidis, G., Georgakopoulou, D., & Kapsi, G. (2021). Clitoris, the unknown: What do postgraduate students of educational sciences know about reproductive physiology and anatomy?. Journal of Biological Education, 55(3), 254–263. doi:10.1080/00219266.2019.1679658

- Armstrong, E. A., England, P., & Fogarty, A. C. K. (2012). Accounting for women’s orgasm and sexual enjoyment in college hookups and relationships. American Sociological Review, 77(3), 435–462. doi:10.1177/2F0003122412445802

- Baltes-Götz, B. (2020). Mediator- und Moderatoranalyse mit SPSS und PROCESS. [Mediator and moderator analysis with SPSS and PROCESS]. Universität Trier. https://www.uni-trier.de/fileadmin/urt/doku/medmodreg/medmodreg.pdf

- Bell, S. N., & McClelland, S. I. (2018). When, if, and how: Young women contend with orgasmic absence. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(6), 679–691. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1384443

- Blair, K. L., Cappell, J., & Pukall, C. F. (2018). Not all orgasms were created equal: Differences in frequency and satisfaction of orgasm experiences by sexual activity in same-sex versus mixed-sex relationships. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(6), 719–733. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1303437

- Bowleg, L., Burkholder, G. J., Noar, S. M., Teti, M., Malebranche, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2015). Sexual scripts and sexual risk behaviors among black heterosexual men: Development of the sexual scripts scale. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(3), 639–654. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0193-y

- Butler, S. E. (2011). Teaching communication in sex education: Facilitating communication skills knowledge and ease of use. (Dissertation, Philosophy). Chicago: DePaul University.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Conley, T. D., & Klein, V. (2022). Women get worse sex: A confound in the explanation of gender differences in sexuality. Perspectives on psychological science, 17(4), 960–978. doi:10.1177/17456916211041598

- Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., Ziegler, A., & Valentine, B. A. (2011). Women, men, and the bedroom: Methodological and conceptual insights that narrow, reframe, and eliminate gender differences in sexuality. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(5), 296–300. doi:10.1177/2F0963721411418467

- Döring, N. (2017). Online-Sexualaufklärung auf YouTube: Bestandsaufnahme und Handlungsempfehlungen für die Sexualpädagogik. Zeitschrift für Sexualforschung, 30(04), 349–367. doi:10.1055/s-0043-121973

- Döring, N., & Mohseni, M. R. (2022). Der Gender Orgasm Gap. Ein kritischer Forschungsüberblick zu Geschlechterdifferenzen in der Orgasmus-Häufigkeit beim Heterosex. [The gendered orgasm gap. A critical research reviews of gender differences in orgasm frequency in heterosex.] Zeitschrift für Sexualforschung, 35(02), 73–87. doi:10.1055/a-1832-4771

- Edwards, N. (2016). Women’s reflections on formal sex education and the advantage of gaining informal sexual knowledge through a feminist lens. Sex Education, 16(3), 266–278. doi:10.1080/14681811.2015.1088433

- Ehrenreich B., Hess E., & Jacobs G. (1987). Re-making love: The feminization of sex. New York: New Anchor Press/Doubleday.

- Fahs, B. (2014). ‘Freedom to’ and ‘freedom from’: A new vision for sex-positive politics. Sexualities, 17(3), 267–290. doi:10.1177/1363460713516334

- Fairchild, A. J., & McDaniel, H. L. (2017). Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: Mediation analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105(6), 1259–1271. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.152546

- Frederick, D. A., St. John, H. K., Garcia, J. R., & Lloyd, E. A. (2018). Differences in orgasm frequency among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual men and women in a U.S. national sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 273–288. doi:10.1007/s10508-017-0939-z

- Fritz, N., & Paul, B. (2017). From orgasms to spanking: A content analysis of the agentic and objectifying sexual scripts in feminist, for women, and mainstream pornography. Sex Roles, 77(9-10), 639–652. doi:10.1007/s11199-017-0759-6

- Géerard, M., Berry, M., Shtarkshall, R. A., Amsel, R., & Binik, Y. M. (2020). Female multiple orgasm: An exploratory internet-based survey. The Journal of Sex Research, 58(2), 206–221. doi:10.1080/00224499.2020.1743224

- Guitelman, J., Mahar, E. A., Mintz, L. B., & Dodd, H. E. (2019). Effectiveness of a bibliotherapy intervention for young adult women’s sexual functioning. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 36, 198–218. doi:10.1080/14681994.2019.1660761

- Goldey, K. L., Posh, A. R., Bell, S. N., & van Anders, S. M. (2016). Defining pleasure: A focus group study of solitary and partnered sexual pleasure in queer and heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 2137–2154. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0704-8

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hensel, D. J., Von Hippel, C. D., Sandidge, R., Lapage, C. C., Zelin, N. S., & Perkins, R. H. (2022). “OMG, Yes!”: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an online intervention for female sexual pleasure. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(3), 269–282. doi:10.1080/00224499.2021.1912277

- Herbenick, D., Fu, T.-C., Arter, J., Sanders, S. A., & Dodge, B. (2018). Women’s experiences with genital touching, sexual pleasure, and orgasm: Results from a US probability sample of women ages 18 to 94. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 201–212. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1346530

- Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Schick, V., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). An event-level analysis of the sexual characteristics and composition among adults ages 18 to 59: Results from a national probability sample in the United States. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(5), 346–361. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02020.x

- Hite, S. (1979). The Hite report. Journal of School Health, 49(5), 251–254. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.1979.tb03845.x

- Kiefer, A. K., & Sanchez, D. T. (2007). Scripting sexual passivity: A gender role perspective. Personal Relationships, 14(2), 269–290. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00154.x

- Kinsey, A. C. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Klein, V., & Conley, T.D. (2021). The role of gendered entitlement in understanding inequality in the bedroom. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(6), 1047–1057. doi:10.1177/2F19485506211053564

- Klein, V., Imhoff, R., Reininger, K. M., & Briken, P. (2019). Perceptions of sexual script deviation in women and men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 631–644. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1280-x

- Klein, V., Laan, E., Brunner, F., & Briken, P. (2022). Sexual pleasure matters (especially for women)—Data from the German sexuality and health survey (GeSiD). Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1–9.

- Koepsel, E. R. (2016). The power in pleasure: Practical implementation of pleasure in sex education classrooms. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 11(3), 205–265. doi:10.1080/15546128.2016.1209451

- Laan, E. T., Klein, V., Werner, M. A., van Lunsen, R. H., & Janssen, E. (2021). In pursuit of pleasure: A biopsychosocial perspective on sexual pleasure and gender. International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(4), 516–536.

- Mahar, E. A., Mintz, L. B., & Akers, B. M. (2020). Orgasm equality: Scientific findings and societal implications. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12(1), 24–32. doi:10.1007/s11930-020-00237-9

- Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human sexual response. Little: Brown.

- Mintz, L. (2017). Becoming cliterate: Why orgasm equality matters-and how to get it. New York: HarperOne.

- Morse, E. (2005). Sex with Emily [Audio podcast]. https://sexwithemily.com/listen/

- O’Connell, H. E., Hutson, J. M., Anderson, C. R., & Plenter, R. J. (1998). Anatomical relationship between urethra and clitoris. The Journal of urology, 159(6), 1892–1897. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63188-4

- Ogletree, S. M., & Ginsburg, H. J. (2000). Kept under the hood: Neglect of the clitoris in common vernacular. Sex Roles, 43(11), 917–926. doi:10.1023/A:1011093123517

- Opperman, E., Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Rogers, C. (2014). “It feels so good it almost hurts”: Young adults’ experiences of orgasm and sexual pleasure. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(5), 503–515. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.753982

- Pascoal, P. M., Narciso, I., & Pereira, N. M. (2014). What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 22–30. doi:10.1080/00224499.2013.815149

- Rubin, J. D., Conley, T. D., Klein, V., Liu, J., Lehane, C. M., & Dammeyer, J. (2019). A cross-national examination of sexual desire: The roles of ‘gendered cultural scripts’ and ‘sexual pleasure’in predicting heterosexual women’s desire for sex. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109502. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.07.012

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

- Sakaluk, J. K., Todd, L. M., Milhausen, R., & Lachowsky, N. J. (2014). Dominant heterosexual sexual scripts in emerging adulthood: Conceptualization and measurement. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(5), 516–531. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.745473

- Sanchez, D. T., Fetterolf, J. C., & Rudman, L. A. (2012). Eroticizing inequality in the United States: The consequences and determinants of traditional gender role adherence in Intimate relationships. The Journal of Sex Research, 49(2-3), 168–183. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.653699

- Sanchez, D. T., Kiefer, A. K., & Ybarra, O. (2006). Sexual submissiveness in women: Costs for sexual autonomy and arousal. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(4), 512–524. 10.1177/2F0146167205282154

- Satinsky, S., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2015). Female sexual subjectivity and verbal consent to receiving oral sex. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 41(4), 413–426.

- Strömquist, L. (2017). Fruit of knowledge. London: Little, Brown Book Group.

- Tuana, N. (2004). Coming to understand: Orgasm and the epistemology of ignorance. Hypatia, 19(1), 194–232. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2004.tb01275.x

- Wade, L. D., Kremer, E. C., & Brown, J. (2005). The incidental orgasm: The presence of clitoral knowledge and the absence of orgasm for women. Women & Health, 42(1), 117–138. doi:10.1300/J013v42n01_07

- Warshowsky, H., Della Mosley, V., Mahar, E. A., & Mintz, L. (2020). Effectiveness of undergraduate human sexuality courses in enhancing women’s sexual functioning. Sex Education, 20(1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/14681811.2019.1598858

- Warshowsky, H., Mahar, E. A., & Mintz, L. (2020). Cliteracy for him: Effectiveness of bibliotherapy for heterosexual men’s sexual functioning. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/14681994.2020.1739638

- Werner, M. A., van Lunsen, R. H. W., Gaasterland, C., Bloemendaal, L. B. A., & Laan, E. (2022). The Amsterdam sexual pleasure index (ASPI) Vol. 0.1: Psychometric properties of the first version of a new multidimensional self-report questionnaire of sexual pleasure and its propensities. Manuscript under revision.

- Wiederman, M. W. (2005). The gendered nature of sexual scripts. The Family Journal, 13(4), 496–502. doi:10.1177/2F1066480705278729

- Willis, M., Jozkowski, K. N., Lo, W.-J., & Sanders, S. A. (2018). Are women’s orgasms hindered by phallocentric imperatives? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 1565–1576. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1149-z

- Wood, R., Hirst, J., Wilson, L., & Burns O’Connell, G. (2018). The pleasure imperative? Reflecting on sexual pleasure’s inclusion in sex education and sexual health settings. Sex Education, 19(1), 1–14. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1468318

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. doi:10.1086/651257