Abstract

Research on childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has consistently demonstrated the long-term effects of such abuse, not only on survivors’ development, but also on the nature and quality of their adult relationships, particularly romantic ones. In this study we examined the moderating role of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and sexual-related posttraumatic stress symptoms (sexual-related PTSS) between CSA and relationship satisfaction. Survey data from 529 individuals who reported being currently in a romantic relationship were analyzed. In the first set of analyses, results demonstrated that participants with CSA reported significantly lower relationship satisfaction and significantly greater severity of PTSD and sexual-related PTSS than participants without CSA. Sexual-related PTSS but not PTSD moderated the association between CSA and participants’ relationship satisfaction, with the model of sexual-related PTSS explaining 20.8% of the variance in relationship satisfaction and the model of PTSD explaining 11.3% of this variance. In the second set of analyses conducted among survivors of CSA only, higher sexual-related PTSS severity was linked with ongoing abuse and with abuse by a non-family member. This study points to the potential contribution made by sexual-related PTSS to relationship satisfaction among survivors of CSA.

Research has shown that individuals who have experienced childhood sexual abuse (CSA) may face challenges in developing and maintaining healthy intimate relationships (Barker, Volk, Hazel, & Reinhardt, Citation2022; Godbout, Briere, Sabourin, & Lussier, Citation2014; Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, & Livingston, Citation2005), with previous research showing that it is associated with various negative romantic relationship outcomes such as lower marital satisfaction and relationship quality (Zamir, Citation2021), more volatile conflict resolution style (Knapp, Knapp, Brown, & Larson, Citation2017), low marital adjustment (Godbout, Sabourin, & Lussier, Citation2009), and decreased satisfaction (Nielsen, Wind, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, & Martinsen, Citation2018). The current study adds to this large body of work by aiming to better understand the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction. Drawing on the conclusions of numerous studies in the field of military veterans (Campbell & Renshaw, Citation2018; Lambert, Engh, Hasbun, & Holzer, Citation2012; Taft, Watkins, Stafford, Street, & Monson, Citation2011) and sexual assault victims (DiMauro, Renshaw, & Blais, Citation2018; DiMauro & Renshaw, Citation2019), which show a negative correlation between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and relationship satisfaction, in the present study we sought to examine how PTSD, one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders among survivors of CSA (Pérez-Fuentes et al., Citation2013), moderates the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction. In addition, based on more recent work showing that trauma symptoms appear during sexual activity in survivors of CSA (sexual-related PTSS; Gewirtz-Meydan & Lassri, Citation2023), we examined the moderating role of sexual-related PTSS as well. The overall goal of the present study was to better understand the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction, using two trauma measures—PTSD and sexual-related PTSS—as moderators.

Child sexual abuse and relationship satisfaction

Childhood sexual abuse is defined as physical contact between a child and another person significantly older, or someone in a position of power or control over the child, during which the child is used for the sexual stimulation of the adult or other people (American Psychological Association, Citation2013). Estimates of CSA prevalence worldwide range from 8–31% for girls and 3–17% for boys (Barth, Bermetz, Heim, Trelle, & Tonia, Citation2013). Pereda et al., in their meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of child sexual abuse, found the rate to be 7.9% of men and 19.7% of women (Pereda, Guilera, Forns, & Gómez-Benito, Citation2009). In Israel, one out of four adults reports having been sexually abused as a child (Schein et al., Citation2000). In the Jewish population, no gender differences have been found in child sexual abuse rates (17.6% for boys and 17.7% for girls), whereas among the Arab population, these rates have been found to be significantly higher among boys (28.4%) than among girls (18.7%) (Lev-Wiesel, Eisikovits, First, Gottfried, & Mehlhausen, Citation2018). In a recent national study conducted among Israeli children, 18.7% of children ages 12–17 reported being sexually abused (Lev-Wiesel et al., Citation2018).

Apart from the well-documented association between CSA and the development of various psychological problems in adulthood, there are also extensive and enduring social consequences linked to CSA (Davis & Petretic-Jackson, Citation2000; DiLillo, Citation2001; Godbout et al., Citation2014), with one of the most detrimental consequences of CSA is its association with low levels of satisfaction individuals experience in their adult romantic relationships (Nielsen et al., Citation2018; Zamir, Citation2021).

One of the main explanations that has been given for the association between CSA and decreased relationship satisfaction is the fact that CSA is by nature a relational trauma, in which one’s basic trust in other people, and the attachment to other, is violated (Barker et al., Citation2022). The early relational imprints of sexual abuse are carried on into adult romantic relationships, a setting in which survivors fear intimacy (Davis, Petretic-Jackson, & Ting, Citation2001; Vaillancourt-Morel, Rellini, Godbout, Sabourin, & Bergeron, Citation2019). Thus, despite their need for intimacy and connection, CSA survivors may approach romantic relationships with a tendency to feel scared of, or overwhelmed by closeness, exhibit poor communication, and rely on autonomy and avoidance (i.e., attachment deactivation strategies) in an attempt to cope with negative affect related to relational distress and dissatisfaction (Barker et al., Citation2022; Knapp et al., Citation2017; Lassri, Fonagy, Luyten, & Shahar, Citation2018; Nielsen et al., Citation2018).

Although the cumulative evidence established in recent years has indeed confirmed the consistent negative association between CSA and relationship satisfaction (Nielsen et al., Citation2018), there is still a critical need to investigate potential moderators explaining this association. It is commonly agreed upon that high marital relationship satisfaction is highly beneficial to well-being, health, and longevity (Proulx, Helms, & Buehler, Citation2007; Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, Citation2014). Thus, it is important to identify moderating factors that might translate into interventions with CSA survivors, on both the individual and couple level.

The moderating role of PTSD

Research suggests that a large proportion (nearly 45%) of CSA survivors develop PTSD (Elklit & Christiansen, Citation2010). Other studies also support the high probability of developing PTSD following CSA, suggesting survivors of CSA have a 5 to 8 times higher risk of developing PTSD compared to individuals with no history of CSA (Cutajar et al., Citation2010; Molnar, Buka, & Kessler, Citation2001; Walker, Carey, Mohr, Stein, & Seedat, Citation2004). According to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Publishing, Citation2013), PTSD symptoms consist of four main criteria: intrusion (e.g., flashbacks, nightmares), avoidance (e.g., avoidance of trauma-related thoughts or feelings and reminders), changes in mood and cognition (e.g., overly negative thoughts and assumptions about oneself or the world, negative affect), and hyperarousal symptoms (e.g., irritability and aggression, difficulty sleeping). The DSM-5 outlines a specific set of diagnostic criteria for PTSD that includes various combinations of symptoms, and individuals who meet these criteria can receive a diagnosis.

An extensive amount of research has shown that PTSD clusters is negatively correlated with relationship satisfaction (Lambert et al., Citation2012; Taft et al., Citation2011). Specifically, studies indicated the relative variance in relationship functioning to specific PTSD symptom components. According to Campbell and Renshaw (Citation2018), the avoidance cluster is consistently associated with relationship functioning, with emotional numbing demonstrating the strongest association. Hyperarousal symptoms have mixed results, with some studies revealing a significant negative association with relationship functioning, and others suggesting null or negative associations. Reexperiencing symptoms are not significantly associated with relationship functioning when accounting for other PTSD clusters.

While previous studies have examined the relationship between PTSD symptom clusters and relationship satisfaction, they have not fully explored the potential impact of trauma and PTSD symptom clusters on the sexual relationships of couples. Given that the trauma is embedded within the intimate relationship (Bigras, Vaillancourt-Morel, Nolin, & Bergeron, Citation2021), it is likely to have a unique contribution that is different from the impact of trauma on non-sexual relationships. This phenomenon has been identified as posttraumatic sexuality, or sexual-related posttraumatic symptoms (sexual-related PTSS; Gewirtz-Meydan & Lassri, Citation2023). Therefore, while the existing research has provided valuable insights, there is still much to be learned about the complex interplay between PTSD and sexual relationships.

The moderating role of sexual-related PTSS

Sexual-related PTSS is defined as the manifestation of trauma symptoms within sexual activity (Gewirtz-Meydan & Lassri, Citation2023). Sexual-related PTSS include symptoms that are based on PTSD clusters, such as dissociation during sex, intrusiveness during sex, and hypervigilance during sex, but also components that are based on complex PTSD symptoms (ICD-11; World Health Organization, Citation2018), such as shame and guilt during sex, interpersonal distress during sex and the need to please the partner during sex. Complex PTSD is a diagnosis that includes not only the three symptom clusters of PTSD but also disturbances in self-organization, which are characterized by affective dysregulation, a negative self-concept, and enduring disturbances in relationships (ICD-11; World Health Organization, Citation2018). Sex-related shame and guilt, pleasing the other in regard to sex, and interpersonal distress during sex, can be understood as complex trauma symptoms as they reflect interpersonal difficulty and distress and internalized shame and guilt.

Sexual-related PTSS exemplifies how traumatic experiences are embedded within the sexual patterns of the survivor. For example, for CSA survivors who suffer from intrusive symptoms, various aspects of sexual contact, such as touch, nudity, flirting, oral or genital stimulation, and/or any kind of penetration, might be triggering (Maltz, Citation1988; O’Driscoll & Flanagan, Citation2016; Staples, Rellini, & Roberts, Citation2012). Thus, during sexual interactions survivors might suffer from flashbacks and other reexperiences of the trauma (Buehler, Citation2008; Kristensen & Lau, Citation2011) which can also include dissociation (Bird, Seehuus, Clifton, & Rellini, Citation2014; Classen, Butler, & Spiegel, Citation2001; Hansen, Brown, Tsatkin, Zelgowski, & Nightingale, Citation2012), all of which may interfere with the sexual response cycle and intensify distress and dysfunction. It is also highly likely that avoidance symptoms would be manifested, namely as avoidance of sexual activity or stimuli. In addition to avoiding sex as a whole, survivors might also avoid different/particular sexual acts or feelings, and such avoidance could be specific to sexual interactions with others or it could be more generalized to sexuality (e.g., feelings, thoughts). Avoidance symptoms can also be demonstrated in preferring impersonal sex or excessive masturbation or porn use (Schwartz & Galperin, Citation2002). Alterations in cognition and mood would likely consist of survivors’ negative beliefs about sex (e.g., “sex is harmful and disgusting,” or “I need to trade sex for love”), about themselves (e.g., “I am unworthy of sexual pleasure,” or alternatively “I am only good for sex”), and about others (e.g., “he/she will always sexually hurt me”), as well as various negative emotional reactions toward sex, such as guilt and shame (Kilimnik & Meston, Citation2021), anxiety, fear, and disgust (Meston, Rellini, & Heiman, Citation2006), all of which have been documented among CSA survivors. Finally, hypervigilance, which refers to physiological processes related to hyperarousal, might be implicated in sexual difficulties among CSA survivors. Hypervigilance, as part of hyperarousal, might limit an individual’s ability to focus on pleasant sensations and could exacerbate unpleasant sensations, such as sexual pain (Payne, Binik, Amsel, & Khalifé, Citation2005). In addition, activation of the sympathetic nervous system subsequent to sexual stimulation might also, in turn, reduce sexual desire and arousal (Lorenz, Harte, Hamilton, & Meston, Citation2012; Rellini & Meston, Citation2006). Hypervigilance may also be associated with excessive hypersexual behaviors that serve as a coping mechanism to reduce the stress build-up from hypervigilance (Mark F Schwartz, Galperin, & Masters, Citation1995).

Although both PTSD and sexual-related PTSS are features of trauma in one’s life (either generally or in the sexual domain), previous research has found that sexual-related PTSS has a unique and unshared contribution (i.e., unshared with PTSD) to survivors’ mental health and sexual well-being (Gewirtz-Meydan & Lassri, Citation2023). Based on such findings, and on numerous studies reporting that relationship quality is strongly associated with the sexual domain in romantic relationships (Byers, Citation2005; Quinn-Nilas, Citation2020), we examined both PTSD and sexual-related PTSS as potential moderators in the current study.

The present study

Childhood sexual abuse has long been known to be a risk factor for relationship problems and especially for low relationship quality (Zamir, Citation2021) and decreased relationship satisfaction (Nielsen et al., Citation2018). In the current study we sought to further examine this association by examining PTSD and sexual-related PTSS as possible moderators. Drawing upon findings from numerous studies in the field of military veterans that have shown a negative correlation between PTSD and relationship satisfaction (Lambert et al., Citation2012), in the present study we sought to examine how PTSD moderates the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction. The moderating role of sexual-related PTSS was also examined in a more exploratory manner, based on the established association between sexual problems and decreased relationship satisfaction (Byers, Citation2005; Quinn-Nilas, Citation2020), and the fact that trauma symptoms that appear in the sexual domain can be associated with lower levels of relationship satisfaction. We hypothesized that pursuant to earlier findings, PTSD and sexual-related PTSS would moderate survivors’ relationship satisfaction. Relationship satisfaction, PTSD, and sexual-related PTSS as a function of abuse characteristics were examined only among participants who were identified as CSA survivors (via the cutoff score).

Method

Participants and procedure

We conducted an online survey of a convenience sample of men and women. Participants were recruited mainly via social media (using Facebook and Instagram) and also used SONA systems in the [masked] university. The study recruited participants through advertisements that described the study as focusing on early traumas and their potential impact on current romantic and sexual relationships. The survey was accessible through Qualtrics, a secure web-based survey data collection system. The survey took 25 min to complete, on average, and was open from November 2020 to August 1, 2021. The survey was anonymous, and no data were collected that linked participants to recruitment sources. The institutional review board (IRB) of [masked] university approved all procedures and instruments. Clicking on the link to the survey guided potential respondents to a page that provided information about the purpose of the study, the nature of the questions, and a consent form (i.e., the survey was voluntary; respondents could skip any questions or quit at any time; responses would be anonymous). The first page also offered researcher contact information. In this study, no incentives were offered, except for course credit for students who filled out the survey through SONA systems (20% of the study participants were recruited through SONA).

A total of 1,030 individuals participated in the study. Of them, 529 reported currently being in a relationship. More than half (64%) were identified as CSA survivors according to the cutoff score of the CTQ-SA (see measures; Bernstein et al., Citation2003). Sample of socio-demographic characteristics and characteristics of the abuse are presented in .

Table 1. The study’s sample characteristics.

Measures

Background variables included a brief demographic questionnaire that assessed sex, gender, age, education, religion, religiosity, relational status, and sexual orientation.

Childhood sexual abuse was measured using the sexual abuse subscale of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SA; Bernstein et al., Citation2003). Overall, the CTQ is a 28-item scale developed to assess childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect. For the current study, we used the CTQ-SA subscale which consists five items. Responses to questions beginning “When you were growing up…” were reported on a 5-point Likert type scale, with higher numbers indicating greater perceived CSA severity. In the current study, participants were classified as having a history of CSA if their score on the CTQ-SA (Bernstein et al., Citation2003) was higher than the cutoff of 6 as suggested by (Tietjen et al., Citation2010). Cronbach’s alpha for the CTQ-SA subscale in the current study was good (α = .87).

Childhood sexual abuse characteristics were assessed after the CTQ measure was applied, but only among individuals who indicated (in a yes/no answer) that they were sexually abused as children. This set of questions included questions about (1) age at time of abuse, (2) number of events (single, recurring), (3) duration of abuse (less than one year, more than one year), (3) identity of perpetrator (family member; yes/no), adult (adult, peer), and stranger (stranger, acquaintance).

Relationship satisfaction was assessed using the Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; (Hendrick, Citation1988). The RAS is a 7-item measure of global relationship satisfaction. Responses are given on a 5-point Likert scale. Items are calculated by averaging scores ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater relationship satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha in our study was .0.85.

PTSD symptoms were measured via the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013). The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure that evaluates the degree to which individuals have been bothered in the past month by DSM–5 PTSD symptoms related to their most distressing event from the past. Items are rated from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) and are summed for a total severity score (ranging from 0–80). Cronbach’s alpha for the PCL-5 total score in the current study was excellent (α = 0.96).

Sexual-related PTSS was assessed using the Posttraumatic Sexuality scale (PT-SEX; Gewirtz-Meydan & Lassri, Citation2023). The PT-SEX, a 25-item measure, was developed to assess traumatic reactions experienced during sexual activity. The PT-SEX evaluates dissociation during sex (7 items; “During sex, my mind wanders and I can’t focus on the sexual activity); intrusiveness during sex (5 items; “I am reminded of the perpetrator or the traumatic experience”); sex-related shame and guilt (5 items; “I don’t feel ok for wanting to have sex”); pleasing the other in regard to sex (4 items; “I feel the need to fulfill my partner’s sexual fantasies even when I am not interested in doing so”); interpersonal distress during sex (2 items; “I feel like I am angry at my partner during sex); and hypervigilance (2 items; “During sex, I need my partner to always tell me what is going to happen next”). The items within the factors are averaged, with higher scores indicating higher levels of traumatic sexuality. Participants were presented with the list of manifestations and items and were asked to indicate to what extent they experienced a specific reaction during sexual activity in the past six months on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). In the current study we found the internal consistency to be excellent (α = .93).

Data analysis

The analyses were conducted on 529 participants who were in a relationship. We allowed missing data on all other variables. Overall, 1.63% of the data were missing. To appraise the type of missing data, we conducted the Jamshidian and Jalal’s non-parametric Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test. It comprises the following steps: imputed data are split into k groups according to the k missing data patterns in the original data; Hawkins’ test for equality of covariances across the k groups is performed as if nonsignificant, the data is MCAR. If significant, the Anderson-Darling non-parametric test for equality of covariances across the k groups is performed, and if not significant, Missing At Random (MAR) is assumed. In the current study, MAR is assumed, Hawkins’ median χ2(4) = 1126.76, pmedian = 1.20−242, Anderson-Rubin T = 0.63, pmedian = 0.46. Accordingly, analyses were based on Multiple Imputation (Rubin, Citation2009). In addition, prior to examining the hypotheses, we employed Shapiro-Wilk normality tests to examine deviation from normal distribution, and median absolute deviation (MAD) tests to examine the presence of outliers in all main study measures (using the Routliers R package)—PTSD, sexual-related PTSS, relationship satisfaction, and CSA. We also examined the presence of influential points when appraising the relationship between PTSD, sexual-related PTSS, relationship satisfaction, and CSA (using the influencePlot function of the car R package), as well as linear model assumptions (using the global test of the gvlma R package). These preliminary tests indicated that all main measures were significantly skewed, Ws > 0.57, p < 2.2−16, with dozens of univariate outliers, out of which 5 were influential points (outliers with high leverage scores that could potentially bias the regression-based analyses). In addition, non-constant residuals were found (Skewness = 72.70, p < .0001, Kurtosis = 17.83, p < .0001). In keeping with these results, robust analytical procedures were selected to examine the hypotheses. Specifically, in Part I, we examined whether CSA (none, present) was linked with participants’ relationship satisfaction (H1), PTSD, and sexual-related PTSS (H2), by conducting a series of Yuen’s robust independent samples t-tests followed by an explanatory measure of effect size (using the WRS2 R package). This analysis is robust against the presence of outliers and non-normal distribution. Next, we examined whether PTSD and/or sexual-related PTSS moderated the association between CSA (none, present) and relationship satisfaction (H3). To do so, we conducted a series of hierarchical robust regressions. In the first step of the analyses, we introduced gender, education, and age as covariates, because research has highlighted their importance to either PTSD and/or relationship satisfaction. In the second step of the analyses, we added the measures of PTSD (or sexual-related PTSS), CSA (0 = none, 1 = present), and their interaction. Using the hierarchical steps, we were able to appraise the contribution of the covariates to the explained variance of relationship satisfaction, and the amount of explained variance that our model of interest added above and beyond their contribution. To facilitate the interpretation of results, PTSD or sexual-related PTSS were centered around their sample mean. The analyses were performed by robustbase R package and the lmrob function. It uses the MM-estimator (with Koller and Stahel 2014 setting; see Maechler et al., Citation2022), which is robust against the influence of influential points, and Croux, Dhaene and Hoorelbeke’s (Citation2004) robust standard errors that protect against non-constant residuals. Significant interactions were probed by simple slopes (using the interactions R package). In Part II, we conducted follow-up analyses only among participants with CSA. Specifically, we studied whether the age at which the abuse occurred, number of events (single, recurring), duration (less than one year; more than one year), and identity of perpetrator—(family member; yes/no), adult (adult, peer), and stranger (stranger, acquaintance)—were linked with the severity of PTSD and sexual-related PTSS and participants’ relationship satisfaction. To do so, a series of robust regressions (using the lmrob function) was used. Because of the limited sample size, in these analyses we did not control for any covariate.

Results

Means and standard deviations (SD) of all variables are presented in .

Table 2. Mean and SD of all study variables.

Part I

CSA would be negatively associated with participants’ relationship satisfaction (H1)

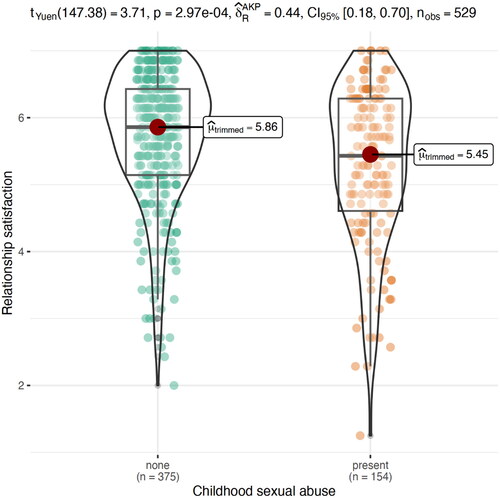

In keeping with predictions, Yuen’s robust independent samples t-test indicated that participants with CSA reported significantly lower relationship satisfaction (Mtrimmed = 5.86, SD = 0.98) than did participants without CSA (Mtrimmed = 5.45, SD = 1.17), t(147.38) = 3.71, p = 2.97−4, δ = 0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) for δ 0.23, 0.65 (see ).

Figure 1. Differences between participants with and without CSA in relationship satisfaction. Participants with CSA reported significantly lower relationship satisfaction than participants without CSA.

CSA would be positively associated with participants’ PTSD and sexual-related PTSS (H2)

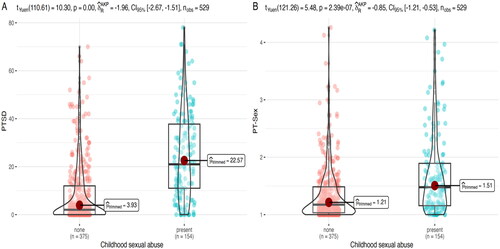

In keeping with predictions, Yuen’s robust independent samples t-tests revealed that participants with CSA reported significantly greater severity of PTSD and sexual-related PTSS (Mtrimmed = 24.86, SD = 18.50, and Mtrimmed = 1.60, SD = 0.72, respectively) than did participants without CSA (Mtrimmed = 4.75, SD = 14.20 and Mtrimmed = 1.21, SD = 0.51, respectively), t(159.42) = 12.74, p > 0001, δ = −1.77, 95% CI for δ −2.18, −1.40 for PTSD, and t(154.79) = 7.21, p = 2.28−11, δ = −1.08, 95% CI for δ −1.47, −0.82 for sexual-related PTSS (see ).

Figure 2. Differences between participants with and without CSA in PTSD (A) and sexual-related PTSS (B). Participants with CSA reported significantly higher severity of PTSD and sexual-related PTSS than participants without CSA.

Sexual-related PTSS and PTSD would moderate the association between CSA and participants’ relationship satisfaction (H3)

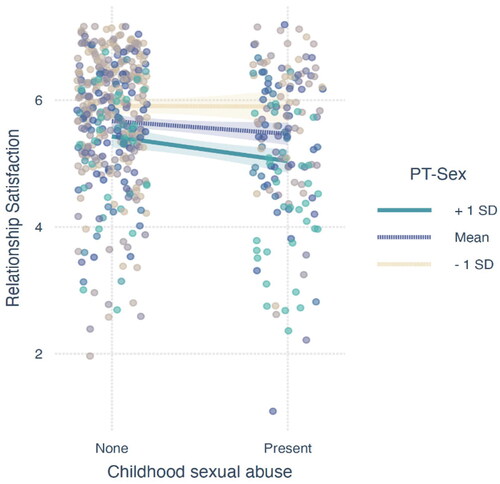

Robust regression coefficients are presented in (PTSD) and (sexual-related PTSS). The analyses indicated that PTSD and sexual-related PTSS were significantly associated with participants’ relationship satisfaction such that the higher the PTSD and sexual-related PTSS severity, the lower participants’ relationship satisfaction. In addition, we found that sexual-related PTSS but not PTSD significantly moderated the association between CSA and participants’ relationship satisfaction. Simple slopes tests revealed that relationship satisfaction was high among those with low severity of sexual-related PTSS (one standard deviation below the sample mean) regardless of the presence or absence of CSA, b = −0.01, SE = 0.14, t = −0.08, p = 0.93. Conversely, among those with high severity of sexual-related PTSS (one standard deviation above the sample mean), those with CSA had significantly lower relationship satisfaction as compared with those without CSA, b = −0.39, SE = 0.12, t = −3.14, p = 0.002 (see ). These results remained significant after controlling for gender, age, and level of education. Regarding the covariates, the analyses indicated that the older the participants, the lower their relationship satisfaction. Overall, the model of sexual-related PTSS explained 20.8% of the variance in relationship satisfaction, and the model of PTSD explained 11.3% of the variance.

Figure 3. Sexual-related PTSS significantly moderated the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction. Simple slopes test indicated that relationship satisfaction was high among those with low severity of sexual-related PTSS regardless of the presence or absence of CSA. Conversely, among those with high severity of sexual-related PTSS, those with CSA had significantly lower relationship satisfaction as compared with those without CSA.

Table 3. Robust regression coefficients for predicting relationship satisfaction by covariates, PTSD, CSA, and their interaction.

Table 4. Robust regression coefficients for predicting relationship satisfaction by covariates, sexual-related PTSS, CSA, and their interaction.

Part II

PTSD, sexual-related PTSS, and relationship satisfaction as a function of abuse characteristics

Robust regression coefficients are presented in . The analyses indicated that survivors’ PTSD symptom severity was not significantly associated with any of the abuse characteristics. Conversely, higher sexual-related PTSS severity was linked with ongoing abuse (as compared with a single incident) and with abuse by a non-family member (as compared with a family member); lower relationship satisfaction was linked with abuse by a peer (as compared to abuse by an adult). Other effects were not significant.

Table 5. Robust regression coefficients for predicting PTSD, sexual-related PTSS, and relationship satisfaction by abuse characteristics.

Discussion

In the current study we examined the moderating role of PTSD and sexual-related PTSS in the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction. As for the study’s outcomes, CSA survivors reported significantly lower relationship satisfaction than did participants without CSA. This finding is not surprising given that research on CSA has consistently demonstrated the long-term effects of these experiences on the nature and quality of survivors’ adult relationships, particularly romantic ones (Barker et al., Citation2022; Testa et al., Citation2005; Zamir, Citation2022). However, although CSA has been found to be associated with low relationship satisfaction, studies have suggested that this association may not always be direct, and sometimes weak (Barker et al., Citation2022); therefore, studies have examined pathways from CSA to relationship satisfaction via different mechanisms such as sexual shame (Barker et al., Citation2022), attachment orientation (Barker et al., Citation2022; Liang, Williams, & Siegel, Citation2006), low self-compassion (Lassri & Gewirtz-Meydan, Citation2021), and self-criticism (Lassri et al., Citation2018; Lassri & Gewirtz-Meydan, Citation2021).

In the current study we examined the moderating role of both PTSD and sexual-related PTSS in the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction. The inclusion of both PTSD and sexual-related PTSS in the study is based on previous research linking sexual well-being to relationship satisfaction among survivors of CSA. While PTSD is commonly associated with CSA (Rowan & Foy, Citation1993), sexual-related PTSS may also play a crucial role in the relationship between CSA and relationship satisfaction, as previous studies linked sexual well-being and relationship satisfaction among survivors (Baumann, Bigras, Paradis, & Godbout, Citation2020). Thus, examining both factors is essential for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the impact of CSA on sexual and relationship outcomes. In the current study, participants with CSA reported significantly greater severity of PTSD and sexual-related PTSS than did participants without CSA. This finding also aligns with findings from previous studies indicating that CSA is a risk factor for PTSD (Boumpa et al., Citation2015; Cohen, Deblinger, Mannarino, & Steer, Citation2004; Rowan & Foy, Citation1993). As sexual-related PTSS is a manifestation of PTSD and complex PTSD within the sexual realm, it makes sense that survivors of CSA also reported significantly higher scores in this area (Gewirtz-Meydan & Lassri, Citation2023).

Our moderation hypothesis was partially confirmed. Although both PTSD and sexual-related PTSS were negatively correlated with participants’ relationship satisfaction, only sexual-related PTSS moderated the association between CSA and participants’ relationship satisfaction. This finding was somewhat surprising as we expected PTSD to moderate this association given that the association between PTSD and low relationship satisfaction has been well-established (Campbell & Renshaw, Citation2018; Lambert et al., Citation2012; Taft et al., Citation2011). However, as hypothesized, sexual-related PTSS did moderate the association between CSA and relationship satisfaction. This finding has several potential explanations. This finding can be explained by the significant affect sexual-related PTSS may have on an individual’s sexual functioning and overall sexual well-being (Gewirtz-Meydan & Godbout, Citation2023). Sexual well-being has been found to be strongly associated with relationship satisfaction, even after controlling for various different variables (Byers, Citation2005; Quinn-Nilas, Citation2020; Zhao, Mcnulty, Turner, Lindsey, & Meltzer, Citation2022). However, while PTSD can also affect the individual’s overall well-being and mental health, it may not always be directly associated with sexual functioning and relationship satisfaction (Barker et al., Citation2022; Campbell & Renshaw, Citation2018). Therefore, it is possible that sexual-related PTSS may be a stronger predictor of relationship satisfaction compared to non-sexual PTSS (as measured by the PCL), as sexual well-being is a key component of relationship satisfaction, and sexual-related PTSS directly addresses the distress, functioning and enjoyment around sexuality. It is also possible that the higher explanation of variance by the posttraumatic sexuality measure, compared to the PCL, in the relationship between CSA and relationship satisfaction may be due to the inclusion of complex PTSD symptoms, beyond just trauma-specific symptoms, in the former measure.

In the second set of analyses, we examined the association between the severity of PTSD and sexual-related PTSS, and the characteristics of the abuse (among survivors only). We found that the severity of sexual-related PTSS was linked with ongoing abuse (as compared with a single incident). This finding is consistent with Finkelhor and Browne’s (Finkelhor & Browne, Citation1985) model in which the severity of the CSA (e.g., duration, frequency, coercion) may increase the level of traumatic sexualization; it is also consistent with findings indicating that a longer duration of the abuse (repeated) is associated with increased risk for both sexual difficulties (Pulverman, Kilimnik, & Meston, Citation2018) and PTSD (Batchelder et al., Citation2021; Rodriguez, Kemp, Vande, Ryan, & Foy, Citation1997).

We also found that abuse by a non-family member (as compared with a family member) was associated with severity sexual-related PTSS. This finding was somewhat unexpected as sexual abuse committed by an adult who is close to the child is expected to lead to greater attachment injury and trust issues (Hooghe, Citation2017; Isobel, Goodyear, & Foster, Citation2019). However, this finding should be viewed with caution, as children who experience sexual abuse by a stranger may also develop attachment injuries, trust issues, and feelings of betrayal which are directed toward family members or others in their social networks from childhood who did not recognize the abuse or were unwilling to help (Finkelhor, Citation1987; Karakurt & Silver, Citation2014).

Limitations and future research directions

The findings of this study should be interpreted with caution given its limitations. Firstly, it was conducted mainly among women and relied on a large non-clinical convenience sample, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other populations. This is reflected in the low severity of PTSD symptoms within our sample. In addition, while we implemented measures in Qualtrics to filter and detect poor-quality responses (e.g., prevent multiple submissions), we did not include an awareness question or other specific quality checks to validate the data. One key point to consider is that Israel has cultural norms that may impact the study’s findings, including a conservative attitude toward sexual expression in public and a traditional emphasis on family and procreation. Additionally, there may be taboos surrounding the discussion of sexual difficulties or trauma. These factors could affect the willingness of participants to disclose sensitive information about sexual-related PTSS. It should be noted that 26% of the sample in this study was Muslim, which may further complicate the interpretation of findings due to potential cultural differences in attitudes toward sexuality and sexual trauma. Therefore, the generalizability of the study’s findings beyond the Israeli context should be approached with caution. The limited generalizability of the posttraumatic sexuality measure used, as it was developed with a mostly female Jewish Israeli sample and has only been administered to similar samples to date. This may limit the broader applicability of the findings and highlight the need for additional studies with more diverse samples. Second, the study’s cross-sectional design precludes causal conclusions, and further studies are needed to provide information on various other relational factors (e.g., relationship adjustment, conflicts, and communication) in the aftermath of CSA across the lifespan. Moreover, the use of retrospective self-reports may introduce typical biases, including underreporting, over-reporting, and recall issues. This limitation is especially relevant for items that address subjects such as CSA, trauma, and sexuality, which are often considered intimate, shameful, or taboo topics. Research that has been conducted over the last decade has shown that survivors of CSA are often subjected to other types of maltreatment (e.g., physical and emotional victimization and neglect), a phenomenon known as “poly-victimization” (Finkelhor, Turner, Hamby, & Ormrod, Citation2011). In the present study we sought to examine CSA in isolation; yet other forms of victimization may have contributed to survivors’ difficulties in the sexual domain. In the future, researchers should explore sexual difficulties in light of poly-victimization and include additional methods of data collection, such as clinical interviews. Additionally, future research should include other validated measures of trauma symptoms (e.g., dissociation). Finally, dyadic data are needed to examine how sexual-related PTSS and PTSD among survivors of CSA moderate the relationship satisfaction of the partner.

Clinical implications

This study points to the potential contribution made by sexual-related PTSS to relationship satisfaction among survivors of CSA. When CSA survivors experience sexual-related PTSS, it can be particularly challenging, in comparison to other forms of PTSS. When the survivors are being triggered by an external trigger (e.g., smell or sound from the street), this may be easier for both survivors and their partners to accept, as they do not feel responsible for the emergence of these symptoms. However, in sexual-related PTSS, it is often the sex itself which is triggering (Maltz, Citation2002). In this case, survivors may feel as if they have failed or disappointed their partner (Gewirtz-Meydan & Ofir-Lavee, Citation2020)—feelings which reinforce self-blame and shame. The partner may also feel frustrated and guilty for initiating sex (contributing to an activation of the posttraumatic symptoms and the reexperiencing of the trauma) (Chauncey, Citation1994). In other words, the activation of sexual-related PTSS is more likely to be associated with both survivors’ and partners’ self-blame. In addition to self-blame, blame-shifting can also occur (e.g., for not being sensitive or careful enough, for not giving warnings, for not clearly expressing one’s needs), all of which can be associated with more relational distress and dissatisfaction. Another possible challenge is that many survivors and their partners are made aware of PTSD symptoms but not of sexual-related PTSS. Thus, couples often do not understand why the trauma is activated during sex or how to manage and process this situation.

In the case of treating survivors of child sexual abuse (CSA), clinicians should be aware of the association between sexual-related PTSS and relationship satisfaction. It is important to note that PTSD and sexual-related PTSS may require different therapeutic approaches, despite the fact that they are both features of the trauma. Some clinicians may assume that sexual-related PTSS will resolve on its own if the trauma or PTSD are treated, but this is not necessarily the case. Thus, further examination of the efficacy of clinical interventions in reducing these symptoms is necessary.

It is also essential that clinicians treating trauma survivors acquire appropriate knowledge on sexual-related PTSS. Although the following idea was not examined in the current study, it is possible that PTSD and sexual-related PTSS require different therapeutic approaches, despite the fact that they are both features of the trauma. Some clinicians may hold the assumption that sexual-related PTSS will resolve on its own if the trauma or the PTSD are treated, but this is not necessarily the case (O’Driscoll & Flanagan, Citation2016). Given the little that is known about how to target sexual-related PTSS following CSA, there is a need for further examination of the efficacy of clinical intervention in reducing these symptoms (Gewirtz-Meydan, Citation2022). It is also important that clinicians treating trauma survivors acquire appropriate knowledge on sexual-related PTSS. In the case of trauma therapy, sexual-related PTSS should be addressed. In the case of couple therapy, such interventions should be modified to include discussions about sexual-related PTSS and the increase of relational capacities to manage and emotionally process sexual-related PTSS (Gewirtz-Meydan, Citation2022).

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ateret Gewirtz-Meydan is affiliated with the Crimes against Children Research Center (CCRC), the Interdisciplinary Research Center on Intimate Relationship Problems and Sexual Abuse (CRIPCAS), and Haruv Institute.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Publishing (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-V). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9781585629992

- American Psychological Association. (2013). Guidelines for psychological evaluations in child protection matters. doi:10.1037/a0029891

- Barker, G. G., Volk, F., Hazel, J. S., & Reinhardt, R. A. (2022). Past is present: Pathways between childhood sexual abuse and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 48(2), 604–620. doi:10.1111/jmft.12522

- Barth, J., Bermetz, L., Heim, E., Trelle, S., & Tonia, T. (2013). The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health, 58(3), 469–483. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0426-1

- Batchelder, A. W., Safren, S. A., Coleman, J. N., Boroughs, M. S., Thiim, A., Ironson, G. H., Shipherd, J. C., & O’Cleirigh, C. (2021). Indirect effects from childhood sexual abuse severity to PTSD: The role of avoidance coping. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), NP5476–NP5495. doi:10.1177/0886260518801030

- Baumann, M., Bigras, N., Paradis, A., & Godbout, N. (2020). It’s good to have you: The moderator role of relationship satisfaction in the link between child sexual abuse and sexual difficulties. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 47(1), 1–15. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2020.1797965

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Bigras, N., Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P., Nolin, M. C., & Bergeron, S. (2021). Associations between childhood sexual abuse and sexual well-being in adulthood: A systematic literature review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 30(3), 332–352. doi:10.1080/10538712.2020.1825148

- Bird, E. R., Seehuus, M., Clifton, J., & Rellini, A. H. (2014). Dissociation during sex and sexual arousal in women with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(5), 953–964. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0191-0

- Boumpa, V., Papatoukaki, A., Kourti, A., Mintzia, S., Panagouli, E., Flora, B., Psaltopoulou, T., Spiliopoulou, C., Tsolia, M., Sergentanis, T. N., & Tsitsika, A. (2015). Sexual abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1, 3. doi:10.1007/s00787-022-02015-5

- Buehler, S. (2008). Childhood sexual abuse: Effects on female sexual function and its treatment. Current Sexual Health Reports, 5, 154–158. doi:10.1007/s11930-008-0027-4

- Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 113–118. doi:10.1080/00224490509552264

- Campbell, S. B., & Renshaw, K. D. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder and relationship functioning: A comprehensive review and organizational framework. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 152–162. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.08.003

- Chauncey, S. (1994). Emotional concerns and treatment of male partners of female sexual abuse survivors. Social Work, 39(6), 669–676. doi:10.1093/sw/39.6.66

- Classen, C., Butler, L. D., & Spiegel, D. (2001). A treatment manual for present-focused and trauma-focused group therapies for sexual abuse survivors at risk for HIV infection.

- Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., & Steer, R. A. (2004). A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse–related PTSD symptoms. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 393–402. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000111364.94169.f9

- Croux, C., Dhaene, G., & Hoorelbeke, D. (2004). Robust standard errors for robust estimators. CES-Discussion paper series (DP S), 1–20.

- Cutajar, M. C., Mullen, P. E., Ogloff, J. R. P., Thomas, S. D., Wells, D. L., & Spataro, J. (2010). Psychopathology in a large cohort of sexually abused children followed up to 43 years. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(11), 813–822. doi:10.1016/J.CHIABU.2010.04.004

- Davis, J. L., & Petretic-Jackson, P. A. (2000). The impact of child sexual abuse on adult interpersonal functioning: A review and synthesis of the empirical literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(3), 291–328. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(99)00010-5

- Davis, J. L., Petretic-Jackson, P. A., & Ting, L. (2001). Intimacy dysfunction and trauma symptomatology: Long-term correlates of different types of child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1(14), 63–79. doi:10.1023/A:1007835531614

- DiLillo, D. (2001). Interpersonal functioning among women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse: Empirical findings and methodological issues. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(4), 553–576. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00072-0

- DiMauro, J., & Renshaw, K. D. (2019). PTSD and relationship satisfaction in female survivors of sexual assault. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(5), 534–541. doi:10.1037/tra0000391

- DiMauro, J., Renshaw, K. D., & Blais, R. K. (2018). Sexual vs. non-sexual trauma, sexual satisfaction and function, and mental health in female veterans. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 19(4), 403–416. doi:10.1080/15299732.2018.1451975

- Elklit, A., & Christiansen, D. M. (2010). ASD and PTSD in rape victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(8), 1470–1488. doi:10.1177/0886260509354587

- Finkelhor, D. (1987). The trauma of child sexual abuse: Two models. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2(4), 348–366. doi:10.1177/088626058700200402

- Finkelhor, D., & Browne, A. (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55(4), 530–541. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Hamby, S. L., & Ormrod, R. K. (2011). Poly-victimization: Children’s exposure of multiple types of violence, crime, and abuse. OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin - NCJ235504.

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A., & Ofir-Lavee, S. (2020). Addressing sexual dysfunction after childhood sexual abuse: a clinical approach from an attachment perspective. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(1), 43–59.

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A. (2022). Treating sexual dysfunctions among survivors of child sexual abuse: An overview of empirical research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(3), 840–853. doi:10.1177/1524838020979842

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A., & Lassri, D. (2023). Sex in the shadow of child sexual abuse: The development and psychometric evaluation of the post-traumatic sexuality (PT-SEX) scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(5-6), 4714–4741. doi:10.1177/08862605221118969

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A., & Godbout, N. (2023). Between pleasure, guilt, and dissociation: How trauma unfolds in the sexuality of childhood sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 141, 106195.

- Godbout, N., Sabourin, S., & Lussier, Y. (2009). Child sexual abuse and adult romantic adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(4), 693–705. doi:10.1515/IJAMH.2000.12.2-3.103

- Godbout, N., Briere, J., Sabourin, S., & Lussier, Y. (2014). Child sexual abuse and subsequent relational and personal functioning: The role of parental support. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 317–325. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.001

- Hansen, N. B., Brown, L. J., Tsatkin, E., Zelgowski, B., & Nightingale, V. (2012). Dissociative experiences during sexual behavior among a sample of adults living with HIV infection and a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 13(3), 345–360. doi:10.1080/15299732.2011.641710

- Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, 50(1), 93–98. doi:10.2307/352430

- Hooghe, D. D. (2017). Seeing the unseen: Early attachment trauma and the impact on child’s development. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behaviour, 05(1), 4–7. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000326

- Isobel, S., Goodyear, M., & Foster, K. (2019). Psychological trauma in the context of familial relationships: A concept analysis. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 20(4), 549–559. doi:10.1177/1524838017726424

- Karakurt, G., & Silver, K. E. (2014). Therapy for childhood sexual abuse survivors using attachment and family systems theory orientations. American Journal of Family Therapy, 42(1), 79–91. doi:10.1080/01926187.2013.772872

- Kilimnik, C. D., & Meston, C. M. (2021). Sexual shame in the sexual excitation and inhibition propensities of men with and without nonconsensual sexual experiences. Journal of Sex Research, 58(2), 261–272. doi:10.1080/00224499.2020.1718585

- Knapp, A. E., Knapp, D. J., Brown, C. C., & Larson, J. H. (2017). Conflict resolution styles as mediators of female child sexual abuse experience and heterosexual couple relationship satisfaction and stability in adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(1), 58–77. doi:10.1080/10538712.2016.1262931

- Kristensen, E., & Lau, M. (2011). Sexual function in women with a history of intrafamilial childhood sexual abuse. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26(3), 229–241. doi:10.1080/14681994.2011.622264

- Lambert, J. E., Engh, R., Hasbun, A., & Holzer, J. (2012). Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the relationship quality and psychological distress of intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(5), 729–737. doi:10.1037/a0029341

- Lassri, D., Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., & Shahar, G. (2018). Undetected scars? Self-criticism, attachment, and romantic relationships among otherwise well-functioning childhood sexual abuse survivors. Psychological Trauma-Theory Research Practice and Policy, 10(1), 121–129. doi:10.1037/tra0000271

- Lassri, D., & Gewirtz-Meydan, A. (2021). Self-compassion moderates the mediating effect of self-criticism in the link between childhood maltreatment and psychopathology. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(23–24), 1–24. doi:10.1177/08862605211062994

- Lev-Wiesel, R., Eisikovits, Z., First, M., Gottfried, R., & Mehlhausen, D. (2018). Prevalence of child maltreatment in Israel: A national epidemiological study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 11(2), 141–150. doi:10.1007/s40653-016-0118-8

- Liang, B., Williams, L. M., & Siegel, J. A. (2006). Relational outcomes of childhood sexual trauma in female survivors – A longitudinal study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(1), 42–57. doi:10.1177/0886260505281603

- Lorenz, T. A., Harte, C. B., Hamilton, L. D., & Meston, C. M. (2012). Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between sympathetic nervous system activation and women’s physiological sexual arousal. Psychophysiology, 49(1), 111–117. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01285.x

- Maechler, M., Rousseeuw, P., Croux, C., Todorov, V., Ruckstuhl, A., Salibian-Barrera, M., Verbeke, T., Koller, M., Conceicao, E. L., & di Palma, M. . (2022). Basic Robust Statistics. Package ‘robustbase’.

- Maltz, W. (1988). Identifying and treating the sexual repercussions of incest: A couples therapy approach. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 14(2), 142–170. doi:10.1080/00926238808403914

- Maltz, W. (2002). Treating the sexual intimacy concerns of sexual abuse survivors. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 17(4), 321–327. doi:10.1080/1468199021000017173

- Meston, C. M., Rellini, A. H., & Heiman, J. R. (2006). Women’s history of sexual abuse, their sexuality, and sexual self-schemas. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 229–236. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.229

- Molnar, B. E., Buka, S. L., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: Results from the national comorbidity survey. American Journal of Public Health, 91(5), 753–760. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.5.753

- Nielsen, B. F. R., Wind, G., Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T., & Martinsen, B. (2018). A scoping review of challenges in adult intimate relationships after childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(6), 718–728. doi:10.1080/10538712.2018.1491915

- O’Driscoll, C., & Flanagan, E. (2016). Sexual problems and post-traumatic stress disorder following sexual trauma: A meta-analytic review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(3), 351–367. doi:10.1111/papt.12077

- Payne, K. A., Binik, Y. M., Amsel, R., & Khalifé, S. (2005). When sex hurts, anxiety and fear orient attention towards pain. European Journal of Pain, 9, 427–436. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.10.003

- Pereda, N., Guilera, G., Forns, M., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2009). The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse: A continuation of Finkelhor (1994). Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(6), 331–342. doi:10.1016/J.CHIABU.2008.07.007

- Pérez-Fuentes, G., Olfson, M., Villegas, L., Morcillo, C., Wang, S., & Blanco, C. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of child sexual abuse: A national study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54, 16–27. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.05.010

- Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., & Buehler, C. (2007). Marital quality and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 576–593. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00393.x

- Pulverman, C. S., Kilimnik, C. D., & Meston, C. M. (2018). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on women’s sexual health: A comprehensive review. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 6(2), 188–200. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.12.002

- Quinn-Nilas, C. (2020). Relationship and sexual satisfaction: A developmental perspective on bidirectionality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(2), 624–646. doi:10.1177/0265407519876018

- Rellini, A. H., & Meston, C. M. (2006). Psychophysiological sexual arousal in women with a history of child sexual abuse. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 32(1), 5–22. doi:10.1080/00926230500229145

- Robles, T. F., Slatcher, R. B., Trombello, J. M., & McGinn, M. M. (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140–187. doi:10.1037/a0031859

- Rodriguez, N., Kemp, H. Vande, Ryan, S. W., & Foy, D. W. (1997). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse: A comparison study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(1), 53–59. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.53

- Rowan, A. B., & Foy, D. W. (1993). Post-traumatic stress disorder in child sexual abuse survivors: A literature review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(1), 3–20. doi:10.1002/jts.2490060103

- Rubin, D. (2009). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Schein, M., Biderman, A., Baras, M., Bennett, L., Bisharat, B., Borkan, J., Fogelman, Y., Gordon, L., Steinmetz, D., & Kitai, E. (2000). The prevalence of a history of child sexual abuse among adults visiting family practitioners in Israel. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(5), 667–675. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00128-9

- Schwartz, M. F., & Galperin, L. (2002). Hyposexuality and hypersexuality secondary to childhood trauma and dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation ISSN, 3(4), 107–120. doi:10.1300/J229v03n04

- Schwartz, M. F., Galperin, L. D., & Masters, W. H. (1995). Post-traumatic stress, sexual trauma and dissociative disorder: Issues related to intimacy and sexuality. National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Photocopy/153416NCJRS.pdf

- Staples, J., Rellini, A. H., & Roberts, S. P. (2012). Avoiding experiences: Sexual dysfunction in women with a history of sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(2), 341–350. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9773-x

- Taft, C. T., Watkins, L. E., Stafford, J., Street, A. E., & Monson, C. M. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 22–33. doi:10.1037/a0022196

- Testa, M., VanZile-Tamsen, C., & Livingston, J. A. (2005). Childhood sexual abuse, relationship satisfaction, and sexual risk taking in a community sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1116–1124. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1116

- Tietjen, G. E., Brandes, J. L., Peterlin, B. L., Eloff, A., Dafer, R. M., Stein, M. R., Drexler, E., Martin, V. T., Hutchinson, S., Aurora, S. K., Recober, A., Herial, N. A., Utley, C., White, L., & Khuder, S. A. (2010). Childhood maltreatment and migraine (part I). Prevalence and adult revictimization: A multicenter headache clinic survey. Headache, 50(1), 20–31. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01556.x

- Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P., Rellini, A. H., Godbout, N., Sabourin, S., & Bergeron, S. (2019). Intimacy mediates the relation between maltreatment in childhood and sexual and relationship satisfaction in adulthood: A dyadic longitudinal analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(3), 803–814. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1309-1

- Walker, J. L., Carey, P. D., Mohr, N., Stein, D. J., & Seedat, S. (2004). Gender differences in the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and in the development of pediatric PTSD. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 7(2), 111–121. doi:10.1007/s00737-003-0039-z

- Weathers, F., Litz, B., Keane, T., Palmieri, T., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. (2013). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).

- World Health Organization. (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/

- Zamir, O. (2022). Childhood maltreatment and relationship quality: A review of type of abuse and mediating and protective factors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1344–1357. doi:10.1177/1524838021998319

- Zhao, C., Mcnulty, J. K., Turner, J. A., Lindsey, H. L., & Meltzer, A. L. (2022). Evidence of a bidirectional association between daily sexual and relationship satisfaction that is moderated by daily stress. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 3791–3806. doi:10.1007/s10508-022-02399-0