Abstract

Approximately 1 in 3 women experience low sexual desire. Despite this being a common concern, many women never seek professional help for their difficulties and will instead turn to online resources for information. We sought to address this need for digitally-accessible, evidence-based information on low sexual desire by creating a social media Knowledge Translation (KT) campaign called #DebunkingDesire. Our team led a 10 month social media campaign where our primary outcomes for the campaign were impressions, reach, and engagement. We generated over 300,000 social media impressions; appeared on 11 different podcasts that were listened to/downloaded 154,700 times; hosted and participated in eight online events; and attracted website users from 110 different countries. Over the course of the campaign we compiled lessons learned on what worked for disseminating our key messages and the importance of creating community for this population. These findings point to the utility of using social media as part of KT campaigns in sexual health, and to the importance of collaborating with patient partners and considering social media ads and podcasts to meet reach goals.

Introduction

In recent years, those who experience a distressing lack of interest in sexual activity that causes interference in life and relationship satisfaction have been the focus of significant clinical and research interest. A literature search of “low sexual desire” and related terms from the past 20 years alone produced over 750 results. Low sexual desire is a common experience, and in one large-scale population-based study, 34.2% of women who had a sexual partner within the past year endorsed low desire (Mitchell et al., Citation2013). As more women report experiencing low sexual desire, research on effective treatments has increased, but somewhat unfortunately, and perhaps paradoxically, such research findings rarely reach the women and individuals these treatments are designed to help (Kingsberg, Citation2014). In recent years, there has been a significant effort from pharmaceutical companies to identify effective and safe pharmaceutical options for treating low sexual desire. Two medications—Addyi (flibanserin) and Vyleesi (bremelanotide)—have been approved by Health Canada and the FDA (Fisher & Pyke, Citation2017; Kingsberg et al., Citation2019). Interestingly, despite their regulatory approval, re-analyses of the original clinical trials data has raised concern about their efficacy with marginal improvements seen with both treatments above placebo and both being associated with significant unwanted side effects (Jaspers et al., Citation2016; Spielmans, Citation2021).

On the other hand, there is considerable evidence of efficacy for psychological approaches, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based approaches, for improving self-reported sexual desire (Brotto, Citation2017; Brotto et al., Citation2021b; Frühauf, Gerger, Schmidt, Munder, & Barth, Citation2013; Gunst et al., Citation2019; Paterson, Handy, & Brotto, Citation2017). In addition to its potent effect on improving sexual desire, mindfulness-based approaches also increase positive affect and relationship satisfaction (Brotto et al., Citation2021b) and reduce sex-related distress (Paterson et al., Citation2017). These effects have been shown to be retained a year after mindfulness treatment has concluded (Brotto et al., Citation2021b). Despite demonstrated efficacy, women experiencing low sexual desire face significant barriers to accessing these effective treatments (Mitchell, Mercer, Wellings, & Johnson, Citation2009) such as cost, discomfort and embarrassment, and lack of expertise by providers (Belcher et al., Citation2023; Kingsberg, Citation2014). When they do attempt to access these treatments, only half report ever consulting with their doctor and many instead turn to online sources of information (Hobbs et al., Citation2019).

Online resources, while readily accessible, are not necessarily evidence-based. Indeed, many people looking for health information online experience difficulty assessing which sources are trustworthy (Tonsaker, Bartlett, & Trpkov, Citation2014) given that algorithms prioritize popular and often paid sites, not necessarily scientific ones. As an example of the influential impact of online campaigns, a well-funded video campaign to promote the use of sexual pharmaceuticals (Block & Canner, Citation2016) was effective in ultimately leading to the FDA’s approval of one of those medications (Edwards, Citation2010). Given how effective this campaign was for promoting reach of a medication that had significant side effects, we postulated that social media should similarly be leveraged to share knowledge of scientifically-supported, psychosocial approaches to treating low sexual desire.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) define Knowledge Translation (KT) as “a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the health care system” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Citation2020). The well-known 17-year delay from knowledge-to-action provides a compelling reason for implementing KT approaches in Canadian health research (Morris, Wooding, & Grant, Citation2011). The aim of KT is to narrow this gap and improve health outcomes, both within and outside of direct patient care settings (Straus, Tetroe, Graham, & Leung, Citation2015). As many women who experience distressing low sexual desire often report feeling frustrated, guilty, anxious, and sad by their lack of desire (Frost & Donovan, Citation2021), we believed that a KT campaign would effectively share critical information and destigmatize the experience of low sexual desire to a large population who may benefit from this evidence.

The primary goal of this KT campaign was to drive reach of information, particularly highlighting misinformation surrounding low sexual desire in women, to individuals living in Canada. We sought to accomplish this goal by developing a social media knowledge dissemination strategy and toolkit and wrapping that around a campaign called #DebunkingDesire. Knowledge dissemination is defined by CIHR as “identifying the appropriate audience and tailoring the message and medium to the audience” (2020). Our primary focus was on reach of knowledge shared, and we used social media metrics to quantify this outcome. Reach of knowledge shared has been the focus of many systematic reviews of KT over the past decade (Chapman et al., Citation2020).

Collaboration with Patient Partners in Knowledge Translation

A Patient Partner was recruited to be part of the #DebunkingDesire multidisciplinary team to share their lived experience within the campaign key messages. Patient Partnership is defined as the “involvement of patients, their families or representatives, in working actively with health professionals at various levels across the healthcare system (direct care, organizational design and governance, and policy making) to improve health and healthcare services” (Pomey et al., Citation2015).

Partnerships between patients and healthcare providers have been created to improve a patient’s own healthcare plan or to serve on advisory committees for improvement of the quality of care within different healthcare programs or initiatives (Shippee et al., Citation2015). The Strategy For Patient Oriented Research (SPOR) defines the key role that patient partners play in the research process, and there is evidence that incorporating patients into health research results in better quality science (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Citation2021; Richards, Schroter, Price, & Godlee, Citation2018). Patient partnerships can involve one or more patients (Armstrong, Herbert, Aveling, Dixon‐Woods, & Martin, Citation2013) and, case dependent, the patients might receive training and a patient coach or liaison.

The purpose of involving patient partners is to integrate first-hand experience (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2005) to shape all stages of the research process (Hussain-Gambles et al., Citation2004). Specifically, the lived and living experiences of patients (Kendell, Urquhart, Petrella, MacDonald, & McCallum, Citation2014) can directly enhance patient enrollment in research, credibility and generalizability of the results, and comprehensive knowledge translation activities (Shippee et al., Citation2015).

We used the recommendations by Pomey et al. (Citation2015) to select our patient partner, including selecting a partner with: 1) experiential knowledge of the topic, 2) stable health, 3) critical thinking and objectivity, 4) communication skills and openness to speaking in public, 5) willingness to advance the campaign, and 6) availability for the duration of the campaign. Following best practices (Jones et al., Citation2007; Shippee et al., Citation2015), we established from the outset that the relationship among all team members, including the patient partner, was founded upon mutual respect and reciprocity, with all team members contributing equally toward our goals and all being valued equally regardless of professional training.

We chose social media as our primary method of knowledge dissemination due to the finding that women may never seek professional help for their sexual concerns (Mitchell et al., Citation2013), and the fact that social media is a low-barrier strategy to communicate health information (Moorehead et al., Citation2013). Social media can be defined as online platforms that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content (Kaplan & Haenlein, Citation2010). Health researchers are increasingly employing social media to facilitate the dissemination of research findings and as a method of engaging end knowledge users (Dol et al., Citation2019). This recognizes the importance of centering the knowledge user in the design of all dissemination tools (Brownson, Eyler, Harris, Moore, & Tabak, Citation2018). We used the lessons learned from a previous similar KT campaign designed to drive reach about information pertaining to a genital pain condition called Provoked Vestibulodynia (Brotto, Nelson, Barry, & Maher, Citation2021a) given that this campaign overlapped in target audience with the present one. We used the research team’s Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube accounts as the primary vehicles for dissemination.

Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder

The DSM-5 diagnosis of Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder (SIAD) is made when a female endorses at least three of six criteria for 6 months (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). The six criteria are as follows: lack of interest (or no interest) in sexual activity; reduced or absent erotic thoughts or fantasies; reduced level of initiating sex and/or responding to a partner’s sexual advances; reduced pleasure during sexual activity; lack of responsive sexual desire (or desire that emerges after one becomes sexually aroused); and reduced genital and nongenital sensations (i.e., arousal). The polythetic criteria of SIAD means that two women with different symptom expressions may both meet eligibility for a diagnosis (Brotto, Graham, Paterson, Yule, & Zucker, Citation2015). Throughout this social media campaign, we used both SIAD and low sexual desire in our posts in order to ensure the broadest relevance to our audience (who may or may not have had a formal diagnosis of SIAD).

Methods

Knowledge Translation Framework

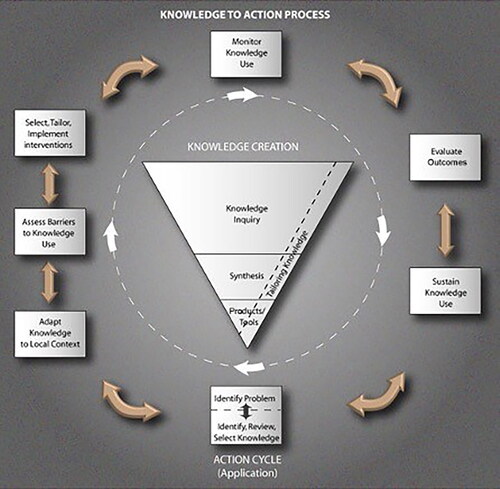

The campaign was informed by the Knowledge-to-Action process (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Citation2015) which guides the creation of knowledge through to the practical application of knowledge as a dynamic and iterative process (Straus et al., Citation2015). Specifically, our campaign fell within the “Knowledge Creation” section of the Knowledge-to-Action process, which is comprised of three tiers: 1) knowledge inquiry, 2) knowledge synthesis, and 3) knowledge tools/products (). Knowledge is tailored at each subsequent tier of this framework. Our campaign leveraged recent empirical findings concerning women’s sexual desire and its causes (Basson et al., Citation2019) to create an infographic video, website, true-or-false quiz, and a social media toolkit for use as knowledge products ().

Figure 1. Knowledge to action process by Straus et al. (Citation2015).

Table 1. Knowledge to Action processes in relation to #DebunkingDesire.

We used the Knowledge Translation Planning Template created by Barwick (Citation2019) to design the individual components of the campaign, which guided our team to identify 1) Project Partners (defined as those who may benefit from a campaign); 2) Partner Engagement (defined as the timeline when Project Partners become engaged); 3) Partner Roles (defined as the aspects a partner(s) will bring to the campaign); 4) KT expertise (defined as the level of KT expertise the project requires); 5) Knowledge Users (defined as the individual or group(s) who may benefit from the evidence presented, and thus will be targeted); 6) Main Messages (defined as the distilled key items of information to be disseminated); 7) KT Goals (defined as the specific goals for each intended audience); 8) KT Strategies (which are further defined by sub-categories of either generating awareness/interest/buy-in share knowledge/inform decision-making, inform research, or facilitate policy change); 9) KT Process (defined as the timeline of KT activities); 10) KT Evaluation (i.e., asking for markers to indicate when KT goals have been achieved); 11) Resources (defined as the sources of information or support utilized to meet KT goals), 12) Budget items; and 13) Procedures (which encourages expansion on procedures and methods for the KT campaign).

Patient Partner in Debunking Desire

Our entire campaign was carried out in partnership with a patient partner, inspired by the Canadian government’s SPOR program (Collier, Citation2011). This means that a patient partner was identified at the start of the KT process and was fully engaged throughout all phases of the grant writing, campaign, analyses, and dissemination, and included in manuscript writing.

Our patient partner was a participant in past research conducted by the KT campaign Team Lead and a volunteer in the patient advisory group that created our infographic video. From a pool of potential patient partners, she was selected given that in addition to lived experience, she expressed a genuine desire to support a wide dissemination of the information she experienced as beneficial pertaining to her own sexual desire concerns. Her professional pursuits as a relationship coach and yoga teacher in Canada and Europe aligned with the campaign’s target group, both nationally and internationally. Finally, her experience as an entrepreneur, her knowledge of social media marketing, her own social media network, and strong public speaking skills were assets to the campaign.

The patient partner attended all team meetings, advised on campaign activities, contributed to the creation of materials, and was treated as an equal member of the team. Examples of her contribution included creating a list of myths regarding sexual desire often endorsed by those experiencing low desire; answering a list of questions for an International Women’s Day blog post; and making suggestions to language to increase its cultural sensitivity (e.g., replacing the word “disorder” throughout campaign materials). Additionally, she contributed to the final report, posted or forwarded the #DebunkingDesire content on her own social media accounts, and spoke at three events where she shared her experience as a patient partner in a KT campaign.

Campaign team

The core #DebunkingDesire team consisted of the Team Lead, a clinician-scientist whose research informed the campaign key messages (LAB); a KT Manager experienced in women’s health research (NP); a Social Media Strategist with expertise disseminating sexual health information on various social media platforms (RK); a patient partner with lived experience of SIAD (DF); a Social Media Assistant with experience creating content for and managing social media accounts (BML); a Communications Assistant with experience analyzing and interpreting social media metrics (MN); and two Research Trainees who carried out comprehensive literature reviews that might inform key messages (FJ, JO). This core team collaborated throughout the entire duration of the campaign and met regularly to design and carry out campaign activities.

Throughout the campaign we also contracted three influencers with varying audience sizes to share original content about the campaign and to amplify our content. Influencers can be defined as people who have established credibility with large social media audiences and therefore have a significant influence on their followers’ decisions (Ki & Kim, Citation2019). These influencers were contracted to promote specific events or awareness days relevant to the campaign.

Our partnerships with social media influencers were then able to amplify our content to new audiences. Influencers were chosen based on alignment between their followers and our target audience, the primary location of their audiences, and any preexisting relationships with our team members. Careful research into their accounts provided us with an insight into their social media conduct and engagement, and helped to ensure there was an alignment of values (e.g., influencers who were sex positive and inclusive), which is critical with sensitive topics like sexuality. This increased the reach of our content to more social media users with whom our content might have resonated with.

Campaign main messages

The main messages (aims) of the campaign were to communicate to our target group that: 1) low sexual desire is a common experience among women, and 2) there are psychological treatments, including cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness, that have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of low desire. Our main KT goals were to drive the reach of our campaign messages and information, and to promote knowledge of sexual desire difficulties. The primary target audience was women experiencing low sexual desire. Our secondary audience was much broader, and included healthcare practitioners, policy makers, partners, researchers, the media, and the general public.

Timeline

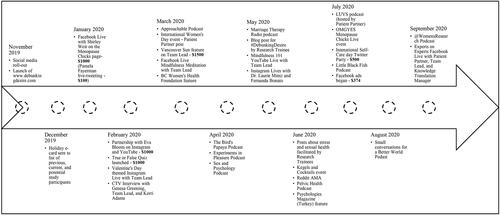

The entire project was 18 months (). The #DebunkingDesire infographic video took 6 months to create. We then obtained a KT grant to support the next phase of the campaign over 12 months. The first two months entailed a series of meetings to design the campaign and involved regular team meetings to discuss dissemination strategies and create a social media toolkit. The campaign officially launched in November 2019 and closed on World Sexual Health Day, September 4, 2020. The next four months were devoted to collation and analysis of metrics, followed by creation of a lay-friendly report of the entire campaign (www.debunkingdesire.com).

Infographic video

Prior to the creation of the social media campaign, the #DebunkingDesire infographic video was created in consultation with a patient advisory group and UBC Studios, a university-situated media production studio that supports academic media and broadcasting needs. The patient advisory group was formed by inviting past research participants who had experienced low sexual desire to participate in a focus group to describe their experience of living with low sexual desire and what they believed would be most helpful for others experiencing low sexual desire to know. Several storyboarding sessions took place to develop and refine a script for the video, with accompanying visual elements honed to be relatable to and representative of our target audience. The final 1.5 min video showed a woman silently struggling with low sexual desire until she discovered that her low sexual desire might be linked to stress, and finds that practicing mindfulness techniques can help reduce this stress. lists sexual desire publications that informed the storyboarding process and what information to include. The video encouraged viewers to consult with their healthcare provider if they were concerned about their sexual desire, and then provided further sexual health resources that viewers could access.

The video was named after our campaign, #DebunkingDesire, to reflect the many myths in popular culture that exist surrounding women’s sexual health and the video’s intention to debunk these myths with scientific information. The content of the video, as well as the visual elements such as the characters and color scheme, became the basis for the content created throughout the social media campaign.

Social accounts

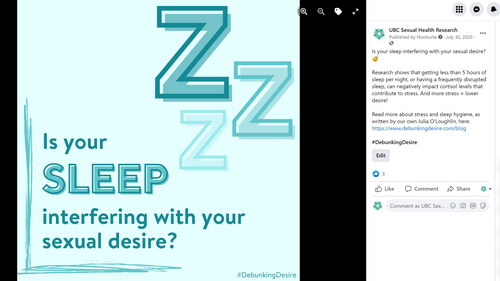

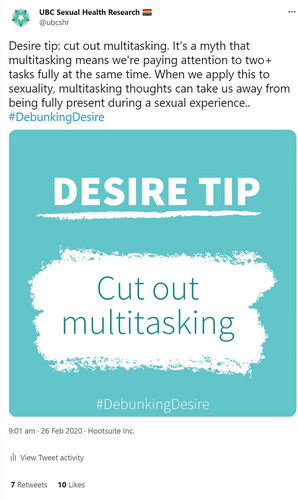

As per our campaign’s primary objective to drive and assess the reach of our social media content and infographic video, we tracked several metrics for the following accounts: (1) YouTube: Our #DebunkingDesire video was hosted through our YouTube channel, UBC Sexual Health Research, and additional videos on campaign-related content were uploaded to YouTube throughout the campaign; (2) Instagram: We used our existing Instagram account, @UBCSHR, to promote the campaign and host Instagram Live events (); (3) Facebook: We used our existing Facebook page, @UBCSHR, to promote campaign content and host Facebook Live events (); (4) Twitter: We used our existing Twitter page, @UBCSHR, to promote campaign content and to host a Twitter Party, which is an organized event that encourages users to all post about a certain topic (); (5) Website: We created a website, debunkingdesire.com, to host all content created over the duration of the campaign, our Social Media Toolkit that we created for collaborators to ensure consistency and accuracy in posting content, as well as a 5-question true-or-false quiz. This quiz was created in partnership with Traction Creative Communications, a digital design company. The goal of the quiz was to create engagement with our audience and debunk some common myths about women’s sexual desire. The quiz questions were: 1) Feeling stressed should not interfere with my sexual desire; 2) It is normal for sexual desire to fluctuate over time; 3) Feeling low sexual desire means that I’m not attracted to or don’t love my partner anymore; 4) There are ways that sexual desire can be improved without taking medications; 5) There is a “normal” amount of sex that someone should be having.

Figure 3. Example Instagram post.

Figure 4. Example Facebook post.

Figure 5. Example Twitter post.

The campaign social media assistant managed the creation and dissemination of all campaign content and engagement with users. On Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, a regular posting schedule of Monday-Wednesday-Friday mornings was maintained throughout the duration of the campaign. Other social media platforms, namely Reddit and YouTube, were used sporadically to host or repost live events.

We contracted three influencers during the campaign to promote and create new content. These influencers promoted their content on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube and were paid based on pre-negotiated prices for their posts/videos. Notably, some of these influencers promoted campaign content outside the scope of their contracts as they found the campaign’s key messages to be compelling for their audiences.

Impact and evaluation

We measured the impact of our campaign by metrics of reach, impressions, and engagement. Reach is defined as the total number of unique users who receive your content in their social media feed (e.g., Facebook timeline), while impressions are defined as the total number of times your content is displayed to a user, regardless of whether they have already seen that content. We also measured user engagement as a metric of knowledge use, defined as any way that a user interacts with our content (e.g. likes, shares, comments, clicks etc.) (Chen, Citation2021).

Budget

The campaign was funded by Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research in the amount of $15,000. The creation of the infographic video with UBC Studios was funded by an operating grant for KT ($10,000) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, both of which were awarded to LAB. Team members’ contributions to the campaign were largely in-kind. The social media strategist and patient partner were each compensated $1000.

Results

DebunkingDesire.com

Our 10-month campaign generated an international reach, with traffic to DebunkingDesire.com originating from 110 countries. Our greatest reach came from Turkey (2963 users [37.55%]), Canada (1803 users [22.85%]), and the United States (1650 users [20.91%]), with a small percentage coming from Romania (124 users [1.57%]). While our efforts were focused on reaching Canadian women, our partnerships with influencers and collaborations with a patient partner and social media strategist with international audiences likely contributed to the reach beyond Canada’s borders.

A total of 7869 users visited the site, resulting in 20,038 pageviews. A total of 2874 (30.9%) of these sessions were the result of social referrals (users directed to the site from social media), with Facebook (1017), YouTube (880), and Instagram stories (433) serving as the largest sources of social referrals. Our interactive quiz—housed at debunkingdesire.com—was viewed by 3119 users and completed by 2060 respondents (66% completion rate). The majority of respondents answered the five questions correctly, with 97% answering question 1 correctly; 83% answering question 2 correctly; 94% answering question 3 correctly; 92% answering question 4 correctly; and 97% answering question 5 correctly.

In the 2 years since the campaign concluded, the debunkingdesire.com website has remained active and continues to be used as a resource for information on low sexual desire. Over 5600 users from 136 countries have visited the website since targeted promotion ended, with 2100 new users from 124 countries visiting the site in the past 6 months alone. These users visited our pages 16,500 times and the page that hosted the interactive quiz was the second-most viewed page, behind the website’s main landing page.

Social Media Metrics

#DebunkingDesire posts shared through the @UBCSHR Instagram account generated 49,106 impressions (number of times our content was delivered to a user’s feed), 2314 likes, 173 URL clicks, 201 bookmarks (posts saved by a user to view at a later time), 213 DMs (posts shared via direct message or to Instagram stories), and 54 follows (users who followed our account after viewing a #DebunkingDesire post). Posts on Facebook reached 34,947 users and generated 38,356 impressions and 2245 engagements (interactions with a post, such as likes, shares, or comments). Tweets generated a further 185,353 impressions, 5220 engagements, 61 hashtag clicks (number of times users clicked on a hashtag used in a post caption to view similar posts), 457 URL clicks, 39 follows, and 2382 media engagements. The #DebunkingDesire video was viewed 3469 with an average view duration of 0:54 out of the total 1:30 duration (55.2%). Out of these views, 355 (9.7%) used Turkish subtitles, 195 (5.6%) used English subtitles, 41 (1.2%) used Canadian French subtitles, 10 (0.3%) used German subtitles, and 6 (0.2%) used Romanian subtitles.

Facebook Advertisements

On days that our paid Facebook advertisements ran we recorded 2334 views on our YouTube video and 1107 users on our website. Additionally, during this period, 544 users visited the page on DebunkingDesire.com that housed our interactive quiz. In total, these ads generated 2743 URL clicks (CAD$0.14 per link click) and reached 59,632 users.

Influencer Partnerships

Posts shared by our three paid influencers generated an additional 11,858 impressions, 696 engagements, 73 URL clicks, 136 likes, and 30 retweets on Twitter, and 23,678 impressions, 937 likes, 119 bookmarks, and 46 shares on Instagram. A YouTube video produced by one of our paid influencers generated 2102 views. Additionally, our team’s patient partner and social media strategist contributed to the campaign with posts on their personal Instagram pages, generating a combined total 4394 likes, 386 shares, and 783 bookmarks.

Podcasts

Although collaborations with podcasts were not a part of our original campaign strategy, they proved to be a successful method of reaching users. Throughout the campaign we worked with 11 podcasts. Of these podcasts, eight reached out directly to the team lead to initiate the collaboration; two were researched and contacted by our team; and one was initiated by an institutional partner on the campaign. Episodes were posted to streaming platforms (e.g., Spotify, Apple Music, etc.) and, in some cases, YouTube. Episodes on streaming platforms were downloaded (when a user saves a podcast episode to their device that can be played later offline) or played (when a user plays an episode through the podcast platform) 94,741 times; the two episodes posted to YouTube were viewed 16,287 times.

Patient Partner Perspective on Best Practices

As part of our analysis of reach, we analyzed our metrics from the perspective of the contributions of our patient partner and several best practices emerged. First, it was important to choose a patient partner who is knowledgeable about and believes in the information to be disseminated; has the required availability to be involved in the campaign; and is invested in the success of the campaign. Second, it is recommended to have a contract in place that clearly outlines the expectations and terms of the collaboration, including the compensation, if applicable. Ideally, a patient partner liaison would be identified to be the contact person, thus easing the communication between the patient partner and the rest of the team. Third, it is essential to make the patient partner feel valued as a team member by engaging them from the beginning of the campaign, encouraging them to come up with ideas and taking their opinions into consideration. Lastly, being aware of the partner’s boundaries about how much they are comfortable sharing from their own experience, as well as allowing them to remove themselves from the team, helped the patient partner feel respected and at ease, especially when the topics are sensitive as is the case with sexuality.

Discussion

The purpose of the KT project was to use social media as the primary method of disseminating information about women’s sexual desire, first to women experiencing low desire, then to the general public, with the goal of driving reach. Critical to the success of our campaign was the diverse team composition, including a clinician-scientist, a patient partner with lived experience, research trainees, KT specialists, and communications assistants, as well as support from several influencers throughout the campaign. Our campaign was guided by the Knowledge-to-Action framework (CIHR, Citation2015) and used the Knowledge Translation Planning template by Barwick to inform its strategy (Barwick, Citation2019; Straus et al., Citation2015).

Across all social media platforms managed by the team or partnered influencers, the campaign generated over 300,000 measured impressions with an average engagement rate (number of engagements divided by impressions) of between 4–6%. According to a recent report by RivalIQ that analyzed 5 million social media posts (Rival IQ, Citation2023), the median engagement rate across Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram is below 1%. The #DebunkingDesire YouTube video housed on our website was viewed 3500 times with an average view duration of 55.2% of the video. When compared to other videos of similar length, this view duration was considered average according to YouTube’s analytics platform. We determined these metrics to be indicators of successful audience reach, and an achievement of the primary campaign goal. Our metrics of engagement were measured through user interactions with our content, with particular focus on the interactions on our website and completions of our true-or-false quiz, both of which disseminated scientific findings about sexual desire (Basson et al., Citation2019; Brotto et al., Citation2021b). Although our team’s social media assistant actively monitored all accounts, we did not face issues with negative comments or spam through this campaign. While moderation was not a concern for our campaign, it may be a concern for other similar campaigns due to the nature of the content covered.

Over 7900 users from 110 countries visited our website and generated 20,000 pageviews. One of the most frequented pages on the website was our true-or-false quiz, which 2060 users completed.

After our primary audience of women with SIAD, our secondary target audience was the general public, and given how broad this is, we did not collect demographic information on who interacted with our content. Furthermore, we did not extract any user information from the social media platforms given evidence that such information is only inferred based on a user’s social media activity and is not always accurate (Hinds & Joinson, Citation2018).

Based on our primary campaign goal to increase reach of information to our target audiences, three factors emerged as markers of success in our campaign: collaborations with a patient partner and with influencers; paying for social media ads to promote our YouTube video; and pursuing podcasts as a method of dissemination.

The role of Patient Partnership

Throughout the campaign, we regularly engaged with both a patient partner and influencers. We intentionally planned our campaign to be patient partner-driven, as it was deemed important to include an authentic lived-experience throughout. Given that her lived-experience of seeking treatment could resonate with the campaign audience, this perspective was vital in crafting key messages. This is consistent with findings indicating that patient engagement in the dissemination of research outcomes in women’s health increases understanding of created materials for others in the community (Poleshuck et al., Citation2015). Of particular importance to our campaign was the nature of our relationship with our patient partner. Tokenism, which centers the symbolic inclusion of a patient partner without meaningful engagement, has and continues to be an issue in patient-oriented research (Ocloo & Matthews, Citation2016). We strove for a genuine, collaborative partnership that enabled our partner to weigh in on every aspect of our campaign, which resulted in her perspective being honored and acted on throughout the campaign.

The role of social media advertisements

Paying for social media advertisements directly benefited the reach of our campaign. We paid CDN $374 to post a single Facebook ad targeted toward adult women in Canada, which directed users to our informational YouTube video. In the 25 days this ad was active, the views on our video more than doubled from ∼1500 to ∼3500 and we reached over 59,600 Facebook users. We also saw a significant increase in website traffic during this time, which meant that users who clicked on the ad to watch our YouTube video also clicked the link to our website included in the video’s description. Our experience suggests that when there is a specific directive in mind, Facebook ads can be useful.

The role of podcasts

We received several requests for our team lead to appear on podcasts throughout the campaign. Although podcasts were not part of the initial campaign strategy, we viewed them as opportunities to directly enhance reach. We also contacted two large Canadian influencers with podcasts whose top demographics were women. This strategy proved to be very successful in boosting campaign reach as our episodes (which featured our team lead) were played/downloaded 154,700 times over multiple platforms. We also found this to be a cost-effective strategy, as all our podcast appearances were free. Podcasts are predicated on a mutually-beneficial relationship, wherein hosts are afforded a knowledgeable guest to interview, and guests are afforded exposure from the podcast’s audience. While we do not have data on how long users listened to each podcast episode, previous consumer market research has found that 93% of regular podcast listeners will listen to all or most of a podcast episode (Edison, 2019). Furthermore, the popularity of science-based podcasts has been increasing exponentially over the past 10 years, showing a demand for factual and informative content delivered by experts (Mackenzie, Citation2018). Podcast appearances therefore provide the opportunity to maximize KT goals as listeners tend to be devoted to their full content.

The benefit of including a secondary target audience

Although we designed our campaign with women as its end knowledge user, it is likely that other audiences may have received the information we shared, including: women’s partners, health care providers, and the general public. Since many women who experience low sexual desire report having never sought help from a healthcare provider for their concerns (Hobbs et al., Citation2019), this secondary reach to health care providers was a potentially unintended positive consequence. This is particularly important since many women who experience low desire also experience strain on their mental health and relationships (Frost & Donovan, Citation2021) and might thus reach out first to a primary care provider for help. In the future, we might design a social media campaign with health care providers as the primary audience, and therefore cater the messaging appropriately to equip them with information regarding management and treatment strategies.

Campaign comparison

To our knowledge, #DebunkingDesire was the first publicly-accessible, evidence-based website about sexual desire co-created with patients. Due to the novelty of this campaign, it is difficult to directly compare #DebunkingDesire to other campaigns. Our target audiences, content areas, and strategies vary greatly, which presents challenges in comparing outcomes in a meaningful way. For example, a previous KT social media campaign, #ItsNotInYourHead (Brotto et al., Citation2021a), aimed to promote reach for information about the common vulvar pain condition known as Provoked Vestibulodynia (Brotto et al., Citation2021a). The overall impressions of #ItsNotInYourHead were upwards of 20 million. However, this can be attributed to the campaign’s use of an influencer agency, which contracted posts to a number of influencers. This method, while effective, had limitations: the #ItsNotInYourHead team were not able to control the quality or type of posts created by these influencers, the team had no personal contact or relation with influencers, and the influencer agency cost a significant portion of their budget. The #DebunkingDesire team’s decision to not use an influencer agency was for the purpose of having increased autonomy over content disseminated and to use our budget in more diverse and creative ways.

Furthermore, the number of impressions listed for #DebunkingDesire is a very conservative estimate. Several of our influencers posted in-kind promotions of our campaign outside the scope of their contracts due to their interest and belief in the campaign messages. Many of these contributions were not accounted for when we collected metrics. We also did not collect metrics from posts made by podcast hosts who featured our team members in their episodes due to not wanting to burden the hosts with this arduous task when they had already featured our content for free.

Lessons learned

While our KT campaign goals were to generate reach of campaign’s key messages, we did not include a community-building strategy to promote the longevity of our key messages. During the campaign, our website acted as a main hub of information and activities. However, due to the limited timeframe of the campaign, the website is no longer as regularly updated with new information after the campaign closed, and risks stagnation without diligent upkeep. We used our existing social media accounts to share campaign content, which were also used to share lab activities outside the scope of the campaign. While we will continue to share information on sexual desire to our social media followers, users who found and followed us exclusively for educational content on low sexual desire may be left without a regular source of information on that topic. Future campaigns should strive to create a dedicated community for those interested in sexual desire to engage regularly.

A caveat to our free - but successful - podcast appearances was an inconsistency among collected metrics. Podcasts had access to varying metrics based on the hosting platform and format of the podcast, which made collecting and interpreting findings a challenge. Furthermore, we did not think it was appropriate to request detailed metrics on promotional posts podcast hosts made through their own social networks due to the arduous nature of metrics reporting and their offer to support our campaign without compensation. Future campaigns should establish this request from the outset with podcast producers.

Finally, a few weeks into the campaign we amended our website to have our #DebunkingDesire YouTube video popup rather than as a static box for users to click on (known as a lightbox). We believed this would draw attention to the video and lead to more views; however, when we analyzed metrics from our website and compared them to views on our video, we saw that the metrics did not align. Therefore, those who were visiting our website largely did not elect to watch the popup video.

Limitations

The campaign had some limitations. First, the scope of available metrics was limited. Despite our team members readily sharing our content throughout the campaign, we were not able to capture important metrics like impressions due to our members not having a Business account with Instagram/Facebook. Moreover, we were not able to gather metrics for posts outside our own and influencer accounts. This includes posts that might have been shared in another language, or posts that our social media accounts were not tagged in and therefore we were not aware of. As a result, our reported metrics are likely an underestimate of actual campaign reach. In addition, our chosen metrics were not able to measure behavior change of those who consumed our content. We do not know how many viewers discussed their sexual concerns with their healthcare provider, or sought other forms of treatment, after viewing our content. Therefore, it is unclear the lasting potential impacts our campaign may have had on the sexual health of those who consumed our content.

Of note, we were primarily focused on reach of our campaign messages, but what may be critical is enhancing knowledge about sexual desire and sexual health more broadly, as this is what may drive treatment seeking behavior. Although we did include a true-or-false quiz in our campaign, this was not used as a means of evaluating the impact of the campaign on increasing the audience knowledge. Additionally, the results of the quiz may have been subject to selection bias as those who already followed our social media accounts prior to completing the quiz would likely be more informed on sexual health information. Future KT campaigns should seek means of assessing knowledge acquired.

Social media is also not without its limitations. Our campaign had the strong support of two social media- and communications-savvy assistants with experience in targeted outreach to key stakeholders. The campaign also benefited from a team lead with a public profile in treatment of sexual health concerns. The expertise of the team likely had a direct positive effect on our ability to garner significant reach efficiently. Further, the individual influences of each team member, the campaign social media account, and each of the influencers engaged with can have a direct bearing on reach. Unfortunately, as followers is an evolving metric, this was not included as a predictor of our campaign’s reach.

Conclusion

#DebunkingDesire was a social media campaign that used an array of digital platforms and methods to drive reach aimed at sharing scientific information on the common concern of low sexual desire in women. Our efforts over the 10-month campaign generated hundreds of thousands of impressions and views on social platforms, and continued to generate reach over a year after concluding active dissemination. Social media is a powerful tool that can give researchers and healthcare professionals direct access to specific populations. To promote greater sexual well-being, we encourage the uptake of social media KT in future projects within women’s sexual health.

| Abbreviations | ||

| CBT | = | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| KT | = | Knowledge Translation |

| SPOR | = | Strategy For Patient Oriented Research |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Armstrong, N., Herbert, G., Aveling, E.L., Dixon‐Woods, M., & Martin, G. (2013). Optimizing patient involvement in quality improvement. Health Expectations, 16(3), e36–e47. doi:10.1111/hex.12039

- Barwick, M. (2019). Knowledge Translation Planning Template. ON: The Hospital for Sick Children. https://ktpathways.ca/system/files/resources/2019-05/Barwick%20KT%20Planning_Template.pdf

- Basson, R., O’Loughlin, J.I., Weinberg, J., Young, A.H., Bodnar, T., & Brotto, L.A. (2019). Dehydroepiandrosterone and cortisol as markers of HPA axis dysregulation in women with low sexual desire. Psychoneuroendicrinology, 104, 259–268. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.03.001

- Belcher, R.B., Sim, S., Meykler, M., Owen-Watson, J., Hassan, N., Rubin, R.S., & Malik, R.D. (2023). A qualitative analysis of female Reddit users’ experiences with low libido: How do women perceive their changes in sexual desire? The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 20(3):287–297. doi:10.1093/jsxmed/qdac045

- Block, J. & Canner, L. (2016) The ‘Grassroots Campaign’ for ‘Female Viagra’ Was Actually Funded by Its Manufacturer. The Cut. https://www.thecut.com/2016/09/how-addyi-the-female-viagra-won-fda-approval.html

- Brotto, L.A. (2017). Evidence-based treatments for low sexual desire in women. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology, 45:11–17. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2017.02.001

- Brotto, L.A., Graham, C.A., Paterson, L.Q., Yule, M.A., & Zucker, K.J. (2015) Women’s endorsement of different models of sexual functioning supports polythetic criteria of Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder in DSM-5. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 1978–1981. doi:10.1111/jsm.12965

- Brotto, L.A., Nelson, M., Barry, L., & Maher, C. (2021a). #ItsNotInYourHead: A Social Media Campaign to Disseminate Information on Provoked Vestibulodynia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(1), 57–68. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01731-w

- Brotto, L.A., Zdaniuk, B., Chivers, M.L., Jabs, F., Grabovac, A., Lalumière, M.L., Weinberg, J., Schonert-Reichl, K., & Basson, R. (2021b). A randomized trial comparing group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with group supportive sex education and therapy for the treatment of female sexual interest/arousal disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(7), 626–639. doi:10.1037/ccp0000661

- Brownson, R.C., Eyler, A.A., Harris, J.K., Moore, J.B., & Tabak, R.G. (2018). Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 24(2), 102–111. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2020) Knowledge translation: Definition. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html#ktap

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2021). Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2015). More About Knowledge Translation at CIHR – Long Descriptions. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/46642.html

- Chapman, E., Haby, M.M., Setsuko Toma, T., Carla de Bortoli, M., Illanes, E., Jose Oliveros, M., & Maia Barreto, J.O. (2020). Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: An overview of systematic reviews. Implementation Science, 15, 14. doi:10.1186/s13012-020-0974-3

- Chen, J. (2021). The most important social media metrics to track. Sprout Social. https://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-metrics/

- Collier, R. (2011). Federal government unveils patient-oriented research strategy. Canadian Medical Association journal, 183(13), E993– E994. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3978

- Dol, J., Tutelman, P.R., Chambers, C.T., Barwick, M., Drake, E.K., Parker, J.A., Parker, R., Benchimol, E.I., George, R.B., & Witteman, H.O. (2019). Health Researchers’ Use of Social Media: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e13687. doi:10.2196/13687

- Edison Research. (2019). The Podcast Consumer 2019. http://www.edisonresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Edison-Research-Podcast-Consumer-2019.pdf

- Edwards, J. (2010) “Infomercial Disorder.” CBS News. http://industry.bnet.com/pharma/10008549/discovery-channels-documentary-on-female-sexual-disorder-is-really-an-infomercial-for-boerhingers-new-sex-pill-for-women/

- Fisher, W.A., & Pyke, R.E. (2017). Flibanserin efficacy and safety in premenopausal women with generalized acquired hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Sexual medicine reviews, 5(4), 445–460. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.05.003

- Frost, R. & Donovan, C. (2021). A qualitative exploration of the distress experienced by long-term heterosexual couples when women have low sexual desire. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 36(1), 22–45. doi:10.1080/14681994.2018.1549360

- Frühauf, S., Gerger, H., Schmidt, H.M., Munder, T., & Barth, J. (2013). Efficacy of Psychological Interventions for Sexual Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 915–933. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-0062-0

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O., & Peacock, R. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 61(2), 417–430. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001

- Gunst, A., Ventus, D., Arver, S., Dhejne, C., Görts-Öberg, K., Zamore-Söderström, E., & Jern, P. (2019). A randomized, waiting-list-controlled study shows that brief, mindfulness-based psychological interventions are effective for treatment of women’s low sexual desire. Journal of Sex Research, 56(7), 913–929. doi:10.1080/00224499.2018.1539463

- Hinds, J., & Joinson, A.N. (2018). What demographic attributes do our digital footprints reveal? A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 13(11), e0207112. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207112

- Hobbs, L.J., Mitchell, K.R., Graham, C.A., Trifonova, V., Bailey, J., Murray, E., Prah, P., & Mercer, C.H. (2019). Help-seeking for sexual difficulties and the potential role of interactive digital interventions: findings from the third british national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(7), 937–946. doi:10.1080/00224499.2019.1586820

- Hussain-Gambles, M., Leese, B., Atkin, K., Brown, J., Mason, S., & Tovey, P. (2004). Involving South Asian patients in clinical trials. Health technology assessment, 8(42), 1–109. doi:10.3310/hta8420

- Jaspers, L., Feys, F., Bramer, W.M., Franco, O.H., Leusink, P., & Laan, E.T. (2016). Efficacy and safety of flibanserin for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine, 176(4), 453–462. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8565

- Jones, J.M., Nyhof-Young, J., Moric, J., Friedman, A., Wells, W., & Catton, P. (2007). Identifying motivations and barriers to patient participation in clinical trials. Journal of Cancer Education, 21(4), 237–242. doi:10.1080/08858190701347838

- Kaplan, A.M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Kendell, C., Urquhart, R., Petrella, J., MacDonald, S., & McCallum, M. (2014). Evaluation of an advisory committee as a model for patient engagement. Patient Experience Journal, 1(2), 62–70. doi:10.35680/2372-0247.1032

- Ki, C-W. C., & Kim, Y-K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing, 36(10), 905–922. doi:10.1002/mar.21244

- Kingsberg, S.A. (2014). Attitudinal Survey of Women Living with Low Sexual Desire. Journal of Women’s Health, 23(10), 817–823. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4743

- Kingsberg, S.A., Clayton, A.H., Portman, D., Williams, L.A., Krop, J., Jordan, R., Lucas, J., & Simon, J.A. (2019). Bremelanotide for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Two randomized phase 3 trials. Obstetrics and gynecology, 134(5), 899–908. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003500

- Mackenzie, L.E. (2018). Science podcasts: Analysis of global production and output from 2004 to 2018. Royal Society Open Science, 6(1), 180932. doi:10.1098/rsos.180932

- Mitchell, K.R., Mercer, C.H., Ploubidis, G.B., Jones, K.G., Datta, J., Field, N., Copas, A.J., Tanton, C., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., Macdowall, W., Phelps, A., Johnson, A.M., & Wellings, K. (2013). Sexual function in Britain: Findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet, 382, 1817–1829. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1

- Mitchell, K.R., Mercer, C.H., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A.M. (2009). Prevalence of Low Sexual Desire among Women in Britain: Associated Factors. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(9), 2434–2444. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01368.x

- Moorehead, S.A., Hazlett, D.E., Harrison, L., Carroll, J., Irwin, A., & Hoving, C. (2013). A New Dimension of Health Care: Systematic Review of the Uses, Benefits, and Limitations of Social Media for Health Communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(4), e85. doi:10.2196/jmir.1933

- Morris, Z.S., Wooding, S., & Grant, J. (2011). The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), 510–520. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180

- Ocloo, J. & Matthews, R. (2016). From tokenism to empowerment: Progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(8), 626–632. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004839

- Paterson, L.Q.P., Handy, A.B., & Brotto, L.A. (2017). A pilot study of 8-session mindfulness-based cognitive therapy adapted for women’s sexual interest/arousal disorder. Journal of Sex Research, 54(7), 850–861. doi:10.1080/00224499.2016.1208800

- Poleshuck, E., Wittink, M., Crean, H., Gellasch, T., Sandler, M., Bell, E., Juskiewicz, I., & Cerulli, C. (2015). Using patient engagement in the design and rationale of a trial for women with depression in obstetrics and gynecology practices. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 43, 83–92. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2015.04.010

- Pomey, M.P., Hihat, H., Khalifa, M., Lebel, P., Néron, A., & Dumez, V. (2015). Patient partnership in quality improvement of healthcare services: Patients’ inputs and challenges faced. Patient Experience Journal, 2(1), 29–42. doi:10.35680/2372-0247.1064

- Richards, T., Schroter, S., Price, A., & Godlee, F. (2018). Better together: Patient partnership in medical journals. BMJ, 362, k3798. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3798

- Rival IQ. (2023). 2023 Social Media Industry Benchmark Report. https://get.rivaliq.com/hubfs/eBooks/2023-social-media-benchmark-report.pdf

- Shippee, N.D., Domecq Garces, J.P., Prutsky Lopez, G.J., Wang, Z., Elraiyah, T.A., Nabhan, M., Brito, J.P., Boehmer, K., Hasan, R., Firwana, B., Erwin, P.J., Montori, V.M., & Murad, M.H. (2015). Patient and service user engagement in research: A systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expectations, 18(5), 1151–1166. doi:10.1111/hex.12090

- Spielmans, G.I. (2021). Re-Analyzing Phase III Bremelanotide Trials for “Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder” in Women. The Journal of Sex Research, 58:9, 1085–1105. doi:10.1080/00224499.2021.1885601

- Straus, S.E., Tetroe, J., Graham, I.D., & Leung, E. (2015) Knowledge to Action: What It Is and What It Isn’t [PowerPoint slides]. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/kt_in_health_care_chapter_2.1_e.pdf

- Tonsaker, T., Bartlett, G., & Trpkov, C. (2014). Health Information on the Internet: Gold mine or minefield? Canadian Family Physician, 60(5), 407–408.