Abstract

The current study investigated the correlates of post-coital dysphoria (PCD) in men and women. Moreover, the study explored the PCD prevalence in the sexual contexts of a relationship, casual sex, and masturbation. An online survey was completed by 156 participants, 51 males and 105 females. All participants were over 18 and have had sex in and out of relationships, as well as having engaged in masturbation. Results showed that PCD was prevalent in each of the three sexual contexts, for both males and females. Furthermore, some previously identified correlates were replicated and found to be statistically significant predictors of PCD. A previously unexplored variable that was also found to significantly predict PCD were negative attitudes toward masturbation. The current research established that PCD occurs in multiple sexual contexts – something previously unknown. Prevalence rates of PCD after sex within a relationship, casual sex, and masturbation, for males were 21.6, 49 and 72.5, respectively. For females, prevalence rates were 11.4, 77.1 and 51.4%, respectively. Additionally, it identified which factors predict the experience of PCD for each of the different sexual contexts for each gender. This has potentially huge implications in formulating a focus for the treatment of PCD, dependent upon the gender and sexual context it is experienced in.

Introduction

Postcoital Dysphoria (PCD), also referred to as postcoital psychological symptoms (PPS) (Burri & Spector, Citation2011) or “post-sex blues”, is characterized by the experience of negative emotions such as tearfulness, sadness, depression, anxiety, agitation or aggression following otherwise satisfactory sexual intercourse (Burri & Spector, Citation2011). Currently, it is an under-researched area within psychology with only a few studies having PCD at the forefront of their investigations (Sadock, Sadock, & Kaplan, Citation2008). PCD is now believed to affect both males and females and have a biosocial psychological basis (Waldinger, Citation2016). As a result, the present study will focus on exploring the conditions in which PCD occur.

One possible theory that may underpin PCD is Bowlby’s (Citation1988) theory of attachment. This suggests that one’s experiences early in life play a very important role in developing stable views of oneself and of others in romantic relationships. This is categorized by their attachment orientation. What is more, attachment may play a role in determining how likely one is to engage in casual or committed sex (Segovia, Maxwell, DiLorenzo, & MacDonald, Citation2019) as the motivations for engaging in sex are different in relation to one’s attachment orientation (Birnbaum, Citation2010; Davis, Shaver, & Vernon, Citation2004). In addition, both attachment avoidant and attachment anxious are associated with greater levels of negative emotions during sexual encounters and more aversive sexual emotions and cognitions (Birnbaum, Citation2007; Birnbaum, Reis, Mikulincer, Gillath, & Orpaz, Citation2006; Davis et al., Citation2006). However, despite the similarity in experience, they occur in two different contexts. Those that are attachment anxious will experience these negative experiences in all encounters, but particularly in uncommitted encounters. Whereas, those that are attachment avoidant are more likely to experience these negative emotions in committed and intimate encounters (Segovia et al., Citation2019). With this being said, it has been consistently found that higher levels of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, were associated with experiences of PCD. Furthermore, they are also are more likely to experience lower overall sexual functioning (e.g. less arousal) and lower sexual satisfaction (in women) (Burri, Schweitzer, & O’Brien, Citation2014; Schweitzer, O’Brien, & Burri, Citation2015). This fits with the phenomena of PCD quite significantly as previous studies have consistently found that lower sexual functioning is associated with PCD experiences (Burri et al., Citation2014; Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). Consequently, it could be the experience of PCD that has reduced the sexual satisfaction reported in the aforementioned studies. As these findings were only found in studies involving females, it is important to now expand this to males in order to establish whether the same pattern of attachment orientation results in the same likelihood of negative sexual experiences, potentially escalating to PCD.

Attachment orientation has also been linked to an individual’s differentiation of self. Differentiation of self is conceptualized by one’s ability to distinguish feeling processes from intellectual processes (Paleg-Popko, Citation2002) and is established through 4 different dimensions: emotional reactivity, the ability to take an I-position, fusion with others, and emotional cutoff (Kerr & Bowen, Citation1988). Those that are more differentiated often have greater autonomy in relationships without experiencing fear and have more intimacy in relationships without being overwhelmed (Bowen & New York, Citation1978; Kerr & Bowen, Citation1988). There have been significant associations between differentiation of self and adult attachment, with the 4 domains of differentiation predicting 40 and 60% of the variability in attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance respectively (Skowron & Dendy, Citation2004). Furthermore, previous literature has found that greater levels of emotional reactivity and greater difficulty maintaining the “I” position were significantly associated with experiencing PCD (Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). As a result, those that are insecurely attached are more likely to struggle in maintaining their differentiation of self and therefore are possibly more vulnerable to experiencing PCD.

In continuation, it has been consistently found in the previous literature on PCD that psychological distress was significantly correlated with experiencing PCD in the past 4 wk and that it even predicted PCD experience in the past 4 wk (Bird, Schweitzer, & Strassberg, Citation2011). This suggests that higher levels of psychological distress could leave you more susceptible to experiencing PCD, but this is only a short-term predictor (i.e. only predicts PCD in the past 4 wk and not persistent PCD). Psychological distress could be further exaggerated dependent upon a person’s attachment orientation, particularly in the context of sexual relationships. It is established in the literature that both attachment anxious and attachment avoidant individuals are more susceptible to negative emotions in sexual encounters (Birnbaum, Citation2007). This could cause more anxiety for future encounters, thus increasing the level of psychological distress experienced.

In the PCD literature to date, there has been an underlying focus of consensual sex within a relationship, with participants commenting on factors such as relationship length and relationship satisfaction (Bird et al., Citation2011; Burri & Spector, Citation2011; Maczkowiac & Schweitzer, Citation2019). Although this is the most obvious circumstance that satisfactory sex occurs, it is certainly not the only. In modern times, casual sex is a common occurrence and not just a trend amongst smaller groups (Grello, Welsh, & Harper, Citation2006). In American nationally representative studies, it has been found that 70–85% of sexually experienced adolescents reported engaging in sexual intercourse with a casual partner within the last year (Grello, Welsh, Harper, & Dickson, Citation2003). The motives, whether autonomous (personal reasons e.g. sexual pleasure) or non-autonomous (external forces e.g. desire for relational intimacy), behind engaging in casual sex can affect whether the consequences are positive or negative (Owen, Quirk, & Fincham, Citation2014; Townsend, Jonason, & Wasserman, Citation2019). However, research has previously struggled to use a consistent definition of what casual sex is, with definitions ranging from “sex outside a committed relationship” (Regan & Dryer, Citation1999) to “hooking up” (Bogle, Citation2008). Wentland and Reissing (Citation2011) went further and categorized casual relationships into 4 types: “one-night stand”, “booty call”, “fuck buddy” and “friends with benefits” with them increasing in the level of intimacy experienced respectively. Irrespective of the terminology, all labels used to describe casual sex share the characteristic that the people involved do not describe the relationship as romantic, nor label the partner as a boyfriend or girlfriend (Regan & Dryer, Citation1999; Simpson & Gangestad, Citation1991). For the purpose of this study, the definition of casual relationship used will clearly encompass all 4 of these subtypes under the umbrella term “casual sex” so that there is no confusion or misinterpretation by participants (during the study) or readers of this paper.

An area previously unexplored in relation to PCD is masturbation. It has also yet to be determined the role that masturbation has on one’s capacity for healthy sexual relationships in later life (Hogarth & Ingham, Citation2009). Masturbation has no reproductive goal and so, to some people it can be viewed as unnatural (Lidster & Horsburgh, Citation1994). However, the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior indicate that, 92% of men and 77% of women, aged 20–24-year-old, have masturbated (Herbenick et al., Citation2010). Despite this seemingly high number, it remains enshrouded by feelings of guilt (Gagnon, Simon, & Berger, Citation1970; Halpern et al., Citation2000; Sharma & Sharma, Citation1998). In previous literature, participants have described how masturbation left them feeling “ashamed and disgusted in [themselves]”, as well as masturbation being “pathetic since you aren’t actually having sex” (Kaestle & Allen, Citation2011). It has been reported that this guilt can be so strong that it displaces the aggressive energy attached to it on to ego activities, which can then be acted out in distorted behavior (Hammerman, Citation2012). Therefore, it is possible that these distorted behaviors could be the same or similar to the symptomology of PCD. Furthermore, evidence suggests that a higher frequency of masturbation is associated with psychological issues such as depression (Cyranowski et al., Citation2004) and a higher dissatisfaction with relationships and less love for partners (Brody & Costa, Citation2009; Brody, Citation2010). Moreover, Bogaert and Sadava (Citation2002) found that secure attachments were negatively associated with masturbation; i.e. securely attached individuals had a lower masturbation frequency. If this is the case, then it is plausible that the phenomenon of PCD could occur after masturbation. Particularly so, if one also reported higher levels of psychological distress (depression and anxiety scores in the current study) or if they were insecurely attached (attachment avoidant and/or attachment anxious). If this were found to be true, it could alter the very definition of PCD.

There has only been a small number of studies exploring the prevalence and correlates of PCD in men (MacZkowiack & Schweitzer, Citation2019) and so it is crucial that more research investigates this. This study will therefore include both males and females in order to assess the replicability of findings amongst both sexes. In addition, as PCD after casual sex and after masturbation have never been investigated explicitly, they too will be explored independently. Previous research has identified that psychological distress, differentiation of self levels and personal sexual functioning issues to be predictors of PCD (Burri et al., Citation2014; Maczkowiac & Schweitzer, Citation2019; Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). Thus, these were all included in the current model. Moreover, this study is somewhat exploratory in nature and so also included attitudes toward masturbation and adult attachment type (anxious/avoidant) in the model. It is important to note that although males and females are reported together in order to go through the results of each sexual contexts, they are not quantitatively or statistically comparable to one another.

Aims and hypotheses

The current study has 4 aims. Firstly, the study aims to replicate previous findings of the overall prevalence rates of PCD amongst males and females independently. The second aim is to replicate previous findings of the correlates of PCD, which includes depression, anxiety, differentiation of self, and sexual functioning. Novel to the current study, the third aim is to explore other potential correlates, including adult attachment type (attachment avoidant or attachment anxious) and attitudes toward masturbation, to PCD. Finally, this study aims to investigate whether PCD occurs in a specific, or a range, of contexts. In particular, the study will focus on the following sexual contexts: relationships, casual sex, and masturbation.

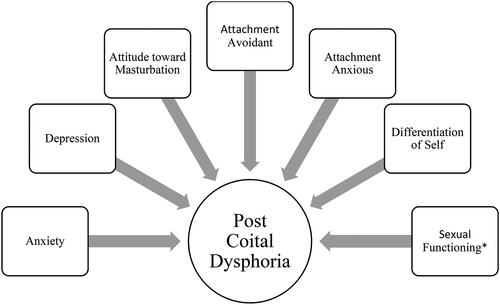

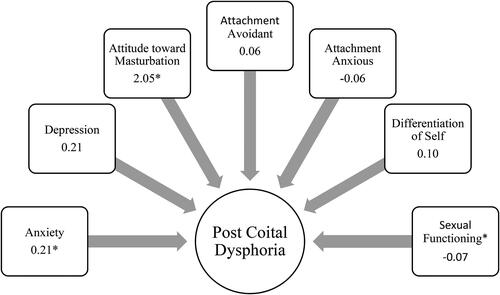

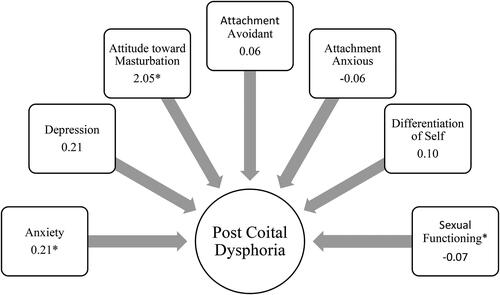

Firstly, it is predicted that PCD will occur in each of the three sexual contexts being explored. Thus, based upon the findings of previous research, it is hypothesized that PCD will be significantly associated with higher scores in areas of psychological distress included in this study (anxiety and depression independently), higher differentiation of self scores, and poorer sexual functioning. Finally, the current study hypothesizes that PCD will be significantly associated with negative attitudes toward masturbation and higher levels of insecure attachments ().

Figure 1. Path diagram displaying the model to be investigated in this study for both sexes independently. *Sexual functioning for males will be measured using the Male Sexual Functioning Index, and for females it will be measured using the Female Sexual Functioning Index.

Method

This study was granted ethical approval by the Nottingham Trent University Ethics Committee.

Design

This was a cross-sectional design using an online survey (via Qualtrics) to gather data. The outcome measure was post-sex experiences, which measures PCD. In specific, the prevalence of PCD, and the occurrence of this phenomenon within the contexts of a relationship, casual sex, and masturbation were also explored. There were six predictor variables for this including: anxiety, depression, attitudes toward masturbation, adult attachment type, differentiation of self, and sexual functioning. Data collection occurred over approximately 2 months from December 2019 to the end of February 2020. A convenience sample was collected through advertising the study through the Sona Research Scheme within Nottingham Trent University. In this case, participants received 2 research credits. It was also advertised on the social media site Facebook. The study used a multiple regression, using the enter method, to establish which variables significantly predict PCD when the others are controlled for. In addition, a multiple regression analysis would indicate which variables work simultaneously together to predict PCD.

Previous research has reported significant differences in the prevalence of sexual difficulties between women in same-sex relationships and women in opposite-sex relationships (Matthews, Hughes, & Tartaro, Citation2006). On the other hand, investigations have found similar prevalence rates of sexual difficulties for both heterosexual and homosexual men. For example, for erectile difficulties there was a prevalence of 4.8 and 5.1% in homosexual men and heterosexual men respectively (Peixoto & Nobre, Citation2015). Due to this discrepancy, it was decided that all sexual orientations were to be included in the analysis.

Participants

This study recruited participants, both male and female, that were aged 18 years and above and who have been or are sexually active. As the study utilizes a repeated measures design (i.e. each participant will complete the survey for each sexual context), participants must have engaged in sexual activity in the contexts of a relationship and casual sex, as well as engage in masturbation. Overall, 248 participants were recruited. As a result of incompletion of the whole survey 92 participants were removed resulting in 156 participants being suitable for analysis. An overview of the sample demographics can be seen in . The mean age of participants was 21.96 and the majority were heterosexual.

Table 1. Demographics and background information of overall sample (n = 156).

Materials

Post-sex experiences scale

This measure is made up of 3 subscales for males, and 4 subscales for females (MacZkowiack & Schweitzer, Citation2019). The male subscales are negative emotional experience, positive emotional experience, and positive connection with partner. An example of a question from the negative emotional experience subscale for males is “Following consensual sexual activity, I generally feel a sense of regret”. The Cronbach Alpha scores are 0.89, 0.88, and 0.79, respectively. The female subscales are negative emotional experience, positive emotional experience, emotional sensitivity, and positive connection to partner. The Cronbach Alpha scores for these are 0.93, 0.91, 0.81, and 0.89, respectively. Responses are measured on a 6-point Likert Scale where 1 represents “Not at all true of me” and 6 represents “Very true of me”. The method for calculating the “Post Sex Experiences Scale” overall score was formulated. This was done by reversing the negative subscales for both males and females (Negative Emotional Experience; Negative Emotional Experience and Emotional Sensitivity, respectively for males and females). The subscales were then totaled and averaged resulting in an overall scale score between 1 and 6. This meant that lower scores indicated a more negative experience post sex and thus, indicating a higher level of PCD experienced. The cut-off point for determining the prevalence of PCD were reflected by all responses relating to “a few times” to “almost always or always”, in accordance with previous literature (Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). This study concentrated on just the prevalence of PCD, rather than the extent of PCD experienced. As such, the prevalence of PCD was confirmed when all items within the scale are answered with “a few times” to “almost always or always”.

Negative attitudes toward masturbation

This is a 30-item measure developed from previous subjects’ responses to questions regarding sex guilt, sex experience, negative attitudes toward masturbation, and masturbation guilt (Abramson & Mosher, Citation1975; Abramson, Citation1973). An example questions is, “When I masturbate, I am disgusted with myself”. Questions were responded to using a 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree). It was found to have split-half reliability coefficient, which was further corrected using the Spearman-Brown prophecy formula, of 0.75 (Abramson & Mosher, Citation1975). The current study found the scale to have a Cronbach Alpha of 0.71.

Anxiety sensitivity index

This 16-item measure is used to assess an individual’s sensitivity to anxiety (Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, Citation1986). Item responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “very little” to “very much”. This provided an overall scale score ranging from 0 to 64, with a higher score being indicative of a greater level of anxiety. The curators of the test (Reiss et al., 1986) found a test-retest reliability score of 0.75 when using the Pearson product-moment correlation. The current study found a Cronbach’s Alpha score of 0.87 showing high reliability.

Kessler psychological distress scale (K10)

The K10 is a 10-item measurement to assess non- specific psychological distress (Kessler et al., Citation2002). It employs a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “all of the time” to “none of the time”. The overall score ranges from 10 to 50 with a higher score portraying a greater level of depression. The instrument measures a range of depressive symptoms such as depressed mood, motor agitation, fatigue, worthless guilt, and anxiety. For example, “During the last 30 days, about how often did you feel hopeless?” The K10 has been found to have a really high level of internal consistency reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.93 (Kessler et al., Citation2002) and 0.90 in the present study.

Experiences in close relationships scale

This is a 36-item measure that judges adult attachment, in particular attachment avoidant and attachment anxiety, by assessing how individual’s experience relationships in general (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, Citation1998). It is measured using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Disagree strongly) to 7 (Agree strongly). An example of one of the scale’s questions is, “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner”. There are two subscales for attachment avoidant and attachment anxiety. From this scale, it is possible to calculate a score for each of the subscales or an overall scale score per participant. For the purpose of this study, scores on each subscale were calculated independently for each participant. Higher scores on each subscale indicated a higher level of that attachment type. It has previously been found to have Cronbach’s alpha scores of 0.94 for the Avoidance domain, and 0.91 for the Anxiety domain in an undergraduate sample (Brennan et al., Citation1998). The present study found a Cronbach’s Alpha score of 0.80 for the overall scale.

Differentiation of self index (DSI)

The DSI is a measurement used to establish an individual’s ability to balance emotional and intellectual functioning alongside intimacy and autonomy in relationships (Skowron & Friedlander, Citation1998). It has 4 different domains: emotional reactivity, taking an “I” position, emotional cut off, and fusion with others. The questions, for example “People have remarked that I am overly emotional”, are measured using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 6 (very true). The Cronbach’s alpha scores calculated suggest a high level of internal consistency and reliability for the measure as a whole with alpha = 0.88. However, the present study found a slightly lower reliability score of 0.74. For the purpose of the current study, the overall scale score was used. This was calculated by totaling the score for each of the 4 domains and then averaging this. From this, the higher the score suggested a greater differentiation of self.

Female sexual functioning index (FSFI)

This is a 19-item measure developed to measure female sexual functioning with regard to: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain (Rosen et al., Citation2000). Lower scores indicated less sexual functioning. The test-retest reliability coefficients were high for each separate domain of the measure with scores ranging from r = 0.79–0.86. It also had a high level of internal consistency with alpha values of 0.82 and above. It has been noted to have good construct validity as well.

Male sexual functioning index (MSFI)

This is a 16-item measure developed to measure male sexual functioning in: desire, arousal, erection, orgasm and satisfaction (Kalmbach, Ciesla, Janata, & Kingsberg, Citation2012). The only differences to the FSFI for females, is the measures on erection and the exclusion of measures of lubrication and pain for females. This is because they typically only apply to each gender exclusively, for example, males are not required to self-lubricate in the same way that females are. Therefore, the FSFI and MSFI both measure sexual functioning but are adapted to be contextually correct for each gender. It has a good internal consistency rating with alphas ranging from 0.66 to 0.85, and with the current study finding a score of 0.94.

Procedure

The online survey software Qualtrics XM (2020) was used to create and conduct the survey. The survey was made available and distributed online through the NTU Sona system and social media sites such as Facebook. Participants first had to read an information page and provide informed consent by clicking a tick box, which was presented at the start of the survey. Participants were then asked to complete the whole survey. Once this was done, participants were presented with a debrief screen. This included useful information for support services and how to contact researchers should they wish to withdraw their data up until a specified date.

Results

Distributions of the raw data were examined in order to identify any violations of the statistical assumptions. Outliers were detected through observing the normal probability plot of standardized residuals against the standardized predicted scores for the raw data. From this, no outliers were identified in any of the cases. Furthermore, through observation of the pattern of the residual scores, it was clear that a linear relationship existed between the predictor variables and the data regarding PCD. As a result, linear multiple regressions were employed.

Prevalence and correlates of PCD

displays the prevalence of PCD symptoms in the sample per condition. PCD symptoms were reflected by the figures relating to “a few times” to “almost always or always”, in accordance with previous literature (Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). For both sexes, PCD was reported the least in the context of sex within a relationship. Males and Females differed in the sexual context in which they experienced the highest rates of PCD. For males, it was after masturbation (72.5%), whereas for females, it was after casual sex (77.1%). On average across sexual conditions, the prevalence rates of PCD symptoms for Males and Females were fairly similar at 35.3 and 31.2% respectively. These findings are similar to previous findings of lifetime PCD prevalence in 41% in males (MacZkowiack & Schweitzer, Citation2019) and 32.9% of females (Bird et al., Citation2011).

Table 2. Prevalence of post coital dysphoria (PCD) (n = 156).

Pearson correlations were assessed to identify which variables correlated with the predictor variables (PCD in each of the three contexts for males and females separately). The results are presented in .

Table 3. Pearson correlations to show any correlation between all variables.

For the purpose of the analysis, males and females were analyzed separately with their own multiple regression models for each of the conditions: relationship, casual sex, and masturbation. The same variables were used in all of the regression models with the only difference being the sexual functioning scale; MSFI was used for males and the FSFI was used for females. The means and standard deviations for each variable across the conditions can be seen in for males and for females.

Table 4. Means and standard deviations for each variable for males for all regression models across conditions.

Table 5. Means and standard deviations for each variable included in the regression models for females across all conditions.

Relationships

Male

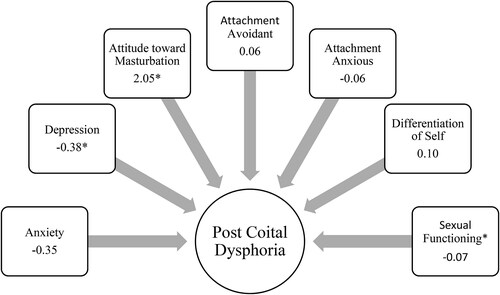

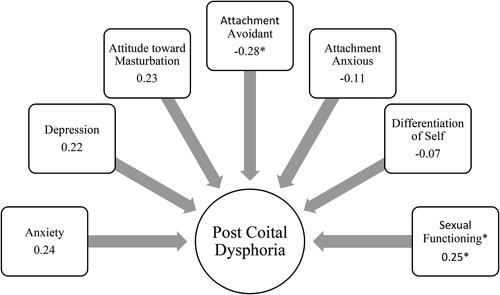

A multiple regression was carried out to investigate whether the variables anxiety, depression, masturbation, attachment avoidant, attachment anxious, differentiation of self and sexual functioning could significantly predict post coital-dysphoria in men in the context of a relationship. Multicollinearity was assessed via correlations between predictors using the tolerance and VIF values for each predictor. This indicated that there was no problematic multicollinearity. The results of the regression indicated that the model explained 24.2% of the variance in PCD scores in males in the context of a relationship. The model was a significant predictor of male PCD in relationships, F (7, 43) = 2.28, p = 0.007. As indicates, there were three predictor variables, depression, attachment avoidant and sexual functioning that displayed a significant association with male PCD in relationships. Both depression and attachment avoidant levels increased, the post sex experience score decreased. This is indicative of a higher level of PCD. On the other hand, as sexual functioning increased, so did the post sex experience. This shows a lower level of PCD ().

Figure 2. Path diagram to show the significant predictors of PCD experience of males in relationships with their beta scores. *Significant beta scores.

Table 6. Summary of the multiple regression analysis for male PCD in relationships (n = 51)

Females

A multiple regression was carried out to investigate whether the variables anxiety, depression, masturbation, attachment avoidant, attachment anxious, differentiation of self and sexual functioning could significantly predict post-coital dysphoria in women in the context of a relationship. Multicollinearity was assessed via correlations between predictors, using the tolerance and VIF values for each predictor. This indicated that there was no problematic multicollinearity. The results of the regression indicated that the model explained 18.1% of the variance in PCD scores in females in the context of a relationship. The model was a significant predictor of female PCD in relationships, F (7, 97) = 4.28, p = 0.000. As indicates, there were two predictor variables, depression and sexual functioning, that displayed a significant positive association with male PCD in relationships ().

Figure 3. Path diagram to indicate the significant predictors of PCD in females within relationships. Beta values displayed. *Significant beta scores.

Table 7. Summary of the multiple regression analysis for female PCD (in relationships) (n = 105).

Table 8. Summary of multiple regression analysis for male PCD experience after casual sex (n = 51).

Casual sex

Males

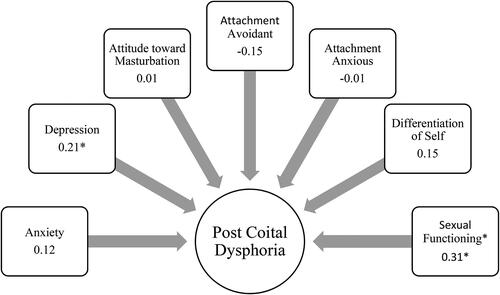

A multiple regression was carried out to investigate whether the variables anxiety, depression, masturbation, attachment avoidant, attachment anxious, differentiation of self and sexual functioning could significantly predict post-coital dysphoria in men in the context of casual sex. Multicollinearity was assessed via correlations between predictors, using the tolerance and VIF values for each predictor. This indicated that there was no problematic multicollinearity. The results of the regression indicated that the model explained 4.5% of the variance in PCD scores in females in the context of casual sex. The model was not a significant predictor of female PCD in instances of casual sex, F (7, 43) = 1.34, p = 0.26. In this instance, there were no significant predictor variables for PCD.

Although the regression model was not significant in predicting potential PCD experienced by males within the context of casual sex, there were some significant correlations. First of all, as the level of anxiety reported by the males increased, the post sex experience decreased meaning that there was a higher level of PCD experienced; r = −0.28, p < 0.05. In addition, the more negative the attitude toward masturbation, the less positive the post sex experience and hence a greater level of PCD was experienced; r = 0.34, p < 0.05 (, ).

Figure 4. Path diagram to indicate the significant predictors of PCD in males after casual sex. Beta values displayed. *Significant beta scores.

Females

A multiple regression was carried out to investigate whether the variables anxiety, depression, masturbation, attachment avoidant, attachment anxious, differentiation of self and sexual functioning could significantly predict post-coital dysphoria in women in the context of casual sex. Multicollinearity was assessed via correlations between predictors, using the tolerance and VIF values for each predictor. This indicated that there was no problematic multicollinearity. The results of the regression indicated that the model explained 5% of the variance in PCD scores in females in the context of casual sex. The model was not a significant predictor of female PCD in relationships, F (7, 97) = 1.78, p = 0.10. There were no predictor variables.

What is more, there were no significant correlations found between the predictor variables and the level of PCD experienced. Although, the highest correlation, albeit insignificant, was attitudes toward masturbation, with more negative attitudes correlating with higher PCD levels (r = 0.20). This can be seen in ().

Figure 5. Path diagram to indicate the significant predictors of PCD in females after casual sex. Beta values displayed. *Significant beta scores.

Table 9. Summary of multiple regression performed for Female PCD for casual sex (n = 105).

Masturbation

Males

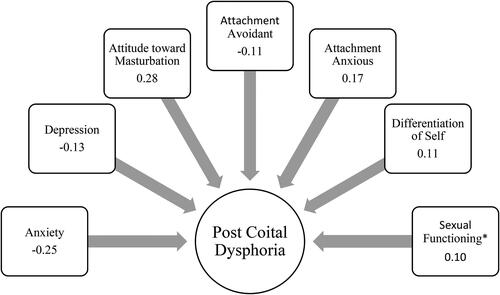

A multiple regression was carried out to investigate whether the variables anxiety, depression, masturbation, attachment avoidant, attachment anxious, differentiation of self and sexual functioning could significantly predict post-coital dysphoria in men in the context of masturbation. Multicollinearity was assessed via correlations between predictors, using the tolerance and VIF values for each predictor. This indicated that there was no problematic multicollinearity. The results of the regression indicated that the model explained 15.6% of the variance in PCD scores in males in the context of masturbation. The model was a significant predictor of male PCD in masturbation, F (7, 43) = 2.32, p = 0.042. As indicates, there were two predictor variables, attachment avoidant and sexual functioning, that displayed a significant association with male PCD during masturbation. Attachment avoidance had a negative association with post-sex experience, indicating higher levels of PCD. Whereas sexual functioning had a positive relationship with post-sex experience, meaning as functioning improved so did one’s post-sex experience. This suggests a lower level of PCD experienced ().

Figure 6. Path diagram showing the significant predictors within the model for PCD experienced by males after masturbation. Beta values displayed. *Significant beta scores.

Table 10. Summary of the multiple regression analysis for male PCD experienced in the context of masturbation (n = 51)

Females

A multiple regression was carried out to investigate whether the variables anxiety, depression, masturbation, attachment avoidant, attachment anxious, differentiation of self and sexual functioning could significantly predict post-coital dysphoria in women in the context of masturbation. Multicollinearity was assessed via correlations between predictors, using the tolerance and VIF values for each predictor. This indicated that there was no problematic multicollinearity. The results of the regression indicated that the model explained 7.9% of the variance in PCD scores in females in the context of masturbation. The model was a significant predictor of female PCD in masturbation, F (7, 97) = 2.28, p = 0.03. As indicates, there were two predictor variables, anxiety and attitude toward masturbation, which displayed a significant and positive association with female PCD during masturbation ().

Figure 7. Path diagram to show which factors significantly predicted PCD in females after masturbation. Beta scores included. *Indicates significant beta score.

Table 11. Summary of the multiple regression analysis for female PCD experiences for masturbation (n = 105).

Discussion

In current literature, the PCD phenomenon is still gaining momentum as an area of research. The current study is, to the best of my knowledge, the first to investigate whether this phenomenon can occur in different sexual context such as casual sex and masturbation. The aims of the current study were four-fold. First, to replicate findings of the prevalence of PCD amongst males and females independently. Second, to replicate previous findings of known correlates to PCD. Similarly, the third aim was to explore potentially new correlates of PCD. Finally, the study aimed to investigate if the PCD phenomenon occurs in the sexual contexts of casual sex and masturbation.

The first aim was to replicate previous findings of the prevalence rates of PCD for males and females. The study found prevalence rates of 35.3 and 31.2% for males and females respectively. This is extremely comparable with Bird et al. (Citation2011) findings of a prevalence of 32.9% for females. The current study’s prevalence findings are also somewhat comparable with other researchers’ findings of 46.2% for life time prevalence rates (Schweitzer et al., Citation2015) and 41.0% in males (MacZkowiack & Schweitzer, Citation2019). These prevalence rates are higher, however it is important to note that the current study had a low sample size in comparison to the others. Therefore, it’s possible that if the sample size was increased, so may the prevalence rates. In addition, PCD prevalence was identified in all of the sexual contexts explored. In males, the highest prevalence was found in the context of masturbation at 72.5%. This was followed by 49.0% for casual sex, and 21.6% for within a relationship. Females had similar figures, but they were for different conditions. The highest prevalence of PCD in females was for casual sex at 77.1%. Next, was masturbation at 51.4%, and then 11.4% for PCD experienced within relationships. So, for both sexes, PCD was experienced the least in the context of a relationship.

Relationship

In the context of a relationship, it was found that both males and females had significant regression models that predicted PCD. Both sexes shared the significant predictor variables of depression and sexual functioning. However, in addition to those, males had an extra significant predictor of being more attachment avoidant.

Casual sex

In the circumstance of casual sex, neither sexes (males nor females) had a significant regression model to predict PCD. There were also no significant predictive variables from either regression model for each sex. Despite this, there were some significant correlations found for males, which can be seen in . Both anxiety and negative attitudes toward masturbation had a positive correlation with male PCD after casual sex. Similarly, although insignificant in statistical power, the highest correlation for female PCD after casual sex was with negative attitudes toward masturbation. This was a positive association meaning that the more negative the attitude toward masturbation, the higher the likelihood of experiencing PCD ().

Masturbation

Finally, predicting PCD in the context of masturbation was explored. In this instance, significant regression models were found independently for both males and females. Interestingly, both sexes had completely different significant predictors within the model. For males, the variables within the model that significantly predicted PCD were higher attachment avoidance and lesser sexual functioning. For females, the significant predictors were anxiety and attitudes toward masturbation.

With regard to the second aim of the study, to replicate findings of the currently known correlates of PCD, it was more complicated. Previous studies exploring PCD correlates (Burri et al., Citation2014; Maczkowiac & Schweitzer, 2018; Schweitzer et al., Citation2015) either focussed on sex within a relationship, or, didn’t specify a sexual context in the same way the current study did. In order to focus on assessing this aim, I will relate it to the sexual context of relationships. The current study replicated previous findings of psychological distress, in the current form of depression, being significantly associated with PCD for both males and females. Despite this, psychological distress (in the form of depression and anxiety separately) was only found in the context of relationships for both sexes. It was not present in each of the sexual contexts explored. Moreover, for masturbation anxiety was found to predict female PCD. Another previously established correlate of PCD was poor sexual functioning (Burri & Spector, Citation2011; Burri et al., Citation2014; Maczkowiac & Schweitzer, 2018; Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). This too was found to be a significant predictor of PCD within a relationship, for both males and females. Similarly, it was replicated for males in the context of masturbation. However, in no instance did the current study replicate the previously found correlations of PCD with overall differentiation of self (Burri et al., Citation2014).

The third aim of the study was to uncover potentially new correlates of PCD. Although previous research has found small associations between attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety with PCD (Schweitzer et al., Citation2015), it was small and only found once. The current study is only the second, to the best of my knowledge, to explore attachment in relation to PCD. The study was somewhat successful in this. For males, higher levels of attachment avoidance were a significant predictor of PCD (i.e. males that are deemed to be more avoidant in attachment style are more likely to experience PCD) both in a relationship and for masturbation. There were no associations found between attachment and PCD for females. The second novel variable explored in the current study are the attitudes toward masturbation. The only instance that this was found to be a significant predictor of PCD was in relation to females after masturbation. Despite this, it was a significant correlation with male PCD in casual sex, and the largest (although non-significant) correlation for females in the same context.

The fourth, and final, aim of the study was to investigate if PCD occurred in other sexual contexts, rather than just sex within a relationship. This was confirmed as prevalence rates were found in each of the three sexual contexts explored, for both males and females as can be seen in . There were also significant regression models found for both males and females for two out of the three sexual contexts.

Previously, literature has highlighted that “psychological distress” is a significant predictor for experiencing PCD (Burri & Spector, Citation2011; Burri et al., Citation2014; Maczkowiac & Schweitzer, Citation2019; Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it is no surprise that depression and anxiety independently arose as significant predictors in some of the regression models as they are both considered elements of “psychological distress”. Another known predictor of PCD that has already been established in the literature is poor sexual functioning (Burri & Spector, Citation2011; Burri et al., Citation2014; Maczkowiac & Schweitzer, Citation2019; Schweitzer et al., Citation2015). As expected, poor sexual functioning arose in the current study as a predictor of PCD in most cases. Both “psychological distress” (depression and anxiety) and poor sexual functioning are not surprising as predictors of PCD. Furthermore, previous links have been established between psychological distress and sexual functioning in that they have a negative relationship with one another. For example, as one’s psychological distress increases, their sexual functioning decreases (Bird et al., Citation2011). This would explain why they were often coupled together when identified as significant predictors in the current study; i.e. for PCD within a relationship and for male PCD for masturbation.

Per contra, Burri et al. (Citation2014) found that higher levels of emotional reactivity, as part of the differentiation of self model, significantly predicted PCD. Nonetheless, the current study did not find any significant associations between one’s overall differentiation of self levels and PCD. This is perhaps because the current study used an overall scale score rather than exploring each of the subscales independently. In this instance, it is possible that the subscales within the DSI moderated each other preventing any association to be identified.

Previously, Schweitzer et al. (Citation2015) found statistically significant, albeit small to moderate, correlations between attachment (anxiety and avoidant) and PCD; with higher levels of attachment avoidance and, to a smaller extent attachment anxiety, increasing the likelihood of PCD. However, they also found that attachment did not predict PCD over a lifetime. Be that as it may, the current study found that for males, attachment avoidance was a significant predictor of PCD in two instances: relationships and masturbation. This finding makes sense in the context of a relationship as one who is higher in attachment avoidance would be more likely to fear intimacy. Consequently, after engaging in sexual intercourse, a very intimate act, their attachment style may produce a conflict in their affect causing them to regret or become “agitated”. This could manifest into the symptoms of PCD. On the other hand, it is unclear why higher levels of attachment avoidance would predict PCD after masturbation. As this fear of intimacy is no longer relevant as it is a solo act rather than an act with another individual. However, as Bogaert and Sadava (Citation2002) suggested, those that are higher in attachment avoidance, often have a low interest in gaining intimate contact with a partner and therefore may have a preference for autosexuality. If this were true, it would increase their masturbation frequency which could leave them more susceptible to experiencing PCD in this instance. Although, higher attachment avoidance was only a significant predictor of PCD for males. This may be explained by the higher number of men reporting to be attachment avoidant in comparison to females (Scharfe, Citation2016).

An interesting finding of the study was that the highest prevalence rates of PCD for females was within the context of casual sex. Surprisingly, this condition was also the only one for females that did not reap a significant regression model, nor any significant predictors. It is unclear why this occurred and definitely leaves room for further research to explore. Especially considering that for males, it was the context with the second highest prevalence rate, and they too did not have a significant regression model nor any significant predictors. Subsequently, it would be interesting for future research to focus on the exploration of PCD in sexual contexts that are not within a relationship as casual and sex and masturbation had the highest PCD prevalence for both sexes.

One implication of these findings is the importance of attitudes toward masturbation found in almost every scenario explored. Not only were negative attitudes a significant predictor for PCD within the regression model for females in the context of masturbation; it was also significantly correlated with PCD experiences in every instance (), except for females within a relationship and for casual sex (correlation present but non-significant in power). It’s plausible that attitudes toward masturbation, or even masturbatory behavior could act as a mediating factor for experiencing PCD in all circumstances. If one’s attitudes toward masturbation can become more positive, and masturbation acts be further normalized within society, it could reduce the likelihood of experiencing PCD. This is a plausible suggestion as it is already understood that masturbation is often a “go-to” in improving sexual functioning in those with difficulties (McMullen & Rosen, Citation1979).

Moreover, despite the overlap between some of the regression models in terms of which variables were significant predictors, there were also differences amongst the regression models for these regarding the different sexual contexts. In understanding what the unique significant predictors are for PCD in different sexual contexts, it will provide a focus for treatments and/or therapies in that they can be more targeted, depending on the sexual context, in relation to what the likely underlying cause of the PCD is.

A limitation to the current study was the high drop-out rate of participants as they progressed through the survey. This is most likely due to the nature of the survey with questions referring to sensitive topics, e.g. psychological distress, as well as personal and “taboo” topics such as sex and masturbation (Tiefer, Citation2007), which are not openly discussed in day to day life. The consequently large number of participants excluded further reduced the statistical power of the analyses. For a multiple regression to have optimally valid results in this case we would require 150 male participants and a further 150 female participants. In both cases this criterion was not met. Yet, significant results were found for both males and females from the multiple regressions that were run. This is positive as it suggests there is a good link between what was explored, which with more participants would only become stronger in statistical significance.

A further limitation is in relation to the “Post Sex Experiences Scale” used to determine the levels of PCD experienced. This is a newly developed scale that has not yet been used in other published research. This means it is quite exploratory in relation to how well it can measure PCD levels. Furthermore, the scale is made up of a number of subscales. For males there are the 3 subscales. This is the same for females, with the addition of a 4th subscale. This means that the males and females can’t be statistical or quantitatively compared (using the overall scale score) which limits the exploration of whether PCD is more gendered. In order to improve validity of the scale it needs to be further refined to establish which questions are the most appropriate. Moreover, it will need to be utilized more widely and perhaps become a more universal measurement of PCD in both males and females.

The main focus of future research should concern the refinement of the Post Sex Experiences Scale MacZkowiack & Schweitzer Citation2019) which is used to measure PCD. This is perhaps only the first or second study, to the best of my knowledge, to utilize this scale. Consequently, the scale overall is fairly untested on sample populations, thus needs much more use to stabilize its validity. Furthermore, as it currently is, the scale has difference subscales for males and females with females having the additional subscale, “emotional sensitivity”. This prevents males and females from being directly comparable with one another. Going forward, the scale should be developed so that males and females have the same subscales to allow for this comparison between sexes. This would enable researchers to establish whether gender has an effect on the likelihood of experiencing PCD. PCD research is still gaining momentum within the field. By refining this current scale, it will be used more often within research with the aim of becoming the universal measure of PCD.

In addition to refining the Post Sex Experience Scale (MacZkowiack & Schweitzer Citation2019), future research should aim to replicate the current study on a larger scale. As mentioned, the current study had a relatively small sample size, with optimum numbers for an effective multiple regression analysis not being met. Despite this, numerous statistically significant results were found. Perhaps in meeting the desired criteria for sample sizes in relation to the number of variables, it will increase the statistical power of the results. Moreover, it may allow the identification of other significant results that the current study didn’t quite reach. For example, attitudes toward masturbation was significantly correlated to PCD in all but one instance, yet, within the regression models, it was only a significant predictor of PCD for females after masturbation. Furthermore, the current study is the first to investigate PCD in different sexual contexts. Statistically significant regression models were found for both males and females after masturbation and PCD prevalence was found for all conditions for both genders. Replication of the study would determine if this is reliable finding.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study has uncovered that PCD occurs in different sexual contexts including casual sex and masturbation, and not just the previously explored context of relationships. Of particular importance is the potential role of one’s attitudes toward masturbation are in the likelihood of experiencing PCD. Significant positive correlations were found in all but one circumstance, with more negative attitudes toward masturbation increasing the likelihood of PCD. This was hypothesized as masturbation can elicit strong feelings of guilt which aligns with the experience of PCD. As a consequence, it’s suggested that the very definition of PCD to be more inclusive and rather it being a phenomena post “satisfactory sex” it could be altered instead to an occurrence post “satisfactory sexual activity”. Furthermore, in extending the contexts with which PCD could be explicitly explored, it will allow for more universal measurement through defining what the sexual contexts are. In addition, the universality of the measurement of PCD needs to further be established through continued use of the Post Sex Experiences scale (MacZkowiack & Schweitzer, Citation2019) in all future research. Also, the current study successfully found significant results despite the limitations in the sample size. Through the extension of the study on a larger scale it may allow for identification of significant results in areas that the current study failed to do—i.e. in the context of casual sex.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramson, P. R. (1973). The relationship of the frequency of masturbation to several aspects of personality and behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 9(2), 132–142

- Abramson, P. R., & Mosher, D. L. (1975). Development of a measure of negative attitudes toward masturbation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43(4), 485–490 doi:10.1037/h0076830

- Bird, B. S., Schweitzer, R. D., & Strassberg, D. S. (2011). The prevalence and correlates of postcoital dysphoria in women. International Journal of Sexual Health, 23(1), 14–25. doi:10.1080/19317611.2010.509689

- Birnbaum, G. E. (2007). Attachment orientations, sexual functioning, and relationship satisfaction in a community sample of women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(1), 21–35. doi:10.1177/0265407507072576

- Birnbaum, G. E. (2010). Bound to interact: The divergent goals and complex interplay of attachment and sex within romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 245–252. doi:10.1177/0265407509360902

- Birnbaum, G. E., Reis, H. T., Mikulincer, M., Gillath, O., & Orpaz, A. (2006). When sex is more than just sex: Attachment orientations, sexual experience, and relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 929–943. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.929

- Bogaert, A. F., & Sadava, S. (2002). Adult attachment and sexual behaviour. Personal Relationships, 9, 191–294. doi:10.1111/1475-6811.00012

- Bogle, K. A. (2008). Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York: New York University Press.

- Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. New York: Aronson.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge.

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Brody, S., & Costa, R. M. (2009). Satisfaction (sexual, life, relationship, and mental health) is associated directly with penile-vaginal intercourse but inversely with other sexual behaviour frequencies. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(7), 1947–1954. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01303.x

- Brody, S. (2010). The relative health benefits of different sexual activities. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(4), 1336–1361. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01677.x

- Burri, A. V., & Spector, T. D. (2011). An epidemiological survey of post-coital psychological symptoms in a UK population sample of female twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 14(3), 240–248. doi:10.1375/twin.14.3.240

- Burri, A., Schweitzer, R., & O’Brien, J. (2014). Correlates of female sexual functioning: Adult attachment and differentiation of self. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(9), 2188–2195. doi:10.1111/jsm.12561

- Cyranowski, J. M., Bromberger, J., Youk, A., Matthews, K., Kravitz, H. M., & Powell, L. H. (2004). Lifetime depression history and sexual function in women at midlife. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 33(6), 539–548. doi:10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044738.84813.3b

- Davis, D., Shaver, P. R., & Vernon, M. L. (2004). Attachment style and subjective motivations for sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(8), 1076–1090. doi:10.1177/0146167204264794

- Davis, D., Shaver, P. R., Widaman, K. E., Vernon, M. L., Beitz, K., & Follete, W. C. (2006). “I can’t get no satisfaction”: Insecure attachment, inhibited sexual communication, and dissatisfaction. Personal Relationships, 13, 465–483. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00130.x

- Gagnon, J., Simon, W., & Berger, A. (1970). Beyond anxiety and fantasy: The coital experiences of college youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 203–222.

- Grello, C. M., Welsh, D. P., & Harper, M. S. (2006). No strings attached: The nature of casual sex in college students. The Journal of Sex Research, 43(3), 255–267. doi:10.1080/00224490609552324

- Grello, C. M., Welsh, D. P., Harper, M. S., & Dickson, J. W. (2003). Dating and sexual relationship trajectories and adolescent functioning. Adolescent and Family Health, 3, 103–112.

- Halpern, C., Joyner, K., Udry, J., & Suchindran, C. (2000). Smart teens don’t have sex (or kiss much either). Journal of Adolescent Health, 26(3), 213–225. doi:10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00061-0

- Hammerman, S. (2012). Masturbation and Character. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 9, 287–311.

- Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Schick, V., Sanders, S., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. (2010). Sexual behavior in the United States: Results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14-94. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 255–265. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x

- Hogarth, H., & Ingham, R. (2009). Masturbation amoung young women and associations with sexual health: An exploratory study. Journal of Sex Research, 6, 558–567. doi:10.1080/00224490902878993

- Kaestle, C., & Allen, K. (2011). The role of masturbation in healthy sexual development: Perceptions of young adults. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 40(5), 983–994.

- Kalmbach, D. A., Ciesla, J. A., Janata, J. W., & Kingsberg, S. A. (2012). Specificity of anhedonic depression and anxious arousal with sexual problems among sexually healthy young adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(2), 505–513 doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02533.x

- Kerr, M., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation. New York: Norton.

- Kessler, R., Andrews, G., Colpe, L., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D., Normand, S., … Zaslavsky, A. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. doi:10.1017/s0033291702006074

- Lidster, C. A., & Horsburgh, M. E. (1994). Mastubration - Beyond myth and taboo. Nursing Forum, 29(3), 18–27. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6198.1994.tb00162.x

- MacZkowiack, J., & Schweitzer, R. (2019). Postcoital dysphoria: Prevalence and correlates among males. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 45(2), 128–140.

- Matthews, A. K., Hughes, T. L., & Tartaro, J. (2006). Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunction in a community sample of lesbian and heterosexual women. In A. M. Omoto & H. S. Kurtzman (Eds.), Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people (pp. 185–205). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- McMullen, S., & Rosen, R. C. (1979). Self-administered masturbation training in the treatment of primary orgasmic dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(5), 912–918. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.47.5.912

- Owen, J. J., Quirk, K., & Fincham, F. D. (2014). Toward a more complete understanding of reactions to hooking up among college women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 40, 396–409. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2012.751074

- Paleg-Popko, O. (2002). Bowen theory: A study of differentiation of self, social anxiety, and physiological symptoms. Contemporary Family Therapy, 24(2), 355–369.

- Peixoto, M. M., & Nobre, P. (2015). Prevalence of sexual problems and associated distress among gay and heterosexual men. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(2), 211–225.

- Regan, P. C., & Dryer, C. S. (1999). Lust? Love? Status? Young adults’ motives for engaging in casual sex. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 11, 1–24.

- Reiss, S., Peterson, R., Gursky, D., & McNally, R. (1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(1), 1–8. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9

- Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., …, D’Agostino, R., Jr. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(2), 191–208.

- Sadock, B. J., Sadock, V. A., & Kaplan, H. I. (2008). Kaplan and Sadock’s concise textbook of clinical psychiatry (3rd edition). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams.

- Scharfe, E. (2016). Sex differences in attachment. In T. K. Schackelford, & V. Weekes-Shackelford, Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 1–5). Canada: Springer International Publishing.

- Schweitzer, R. D., O’Brien, J., & Burri, A. (2015). Postcoital dysphoria: Prevalence and psychological correlates. Sexual Medicine, 3(4), 235–243.

- Segovia, A. N., Maxwell, J. A., DiLorenzo, M. G., & MacDonald, G. (2019). No strings attached? How attachment orientation relates to the varieties of casual sexual relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109455. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.061

- Sharma, V., & Sharma, A. (1998). The guilt and pleasure of masturbation: A study of college girls in Gujarat, India. Sexual and Marital Therapy, 13(1), 63–70. doi:10.1080/02674659808406544

- Simpson, J. A., & Gangestad, S. W. (1991). Individual differences in sociosexuality: Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(6), 870–883. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.870

- Skowron, E. A., & Friedlander, M. L. (1998). The Differentiation of Self Inventory: Development and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(3), 235–246 doi:10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.235

- Skowron, E. A., & Dendy, A. K. (2004). Attachment in adulthood: Relational correlates of effortful control. Contemporary Family Therapy, 26(3), 337–357. doi:10.1023/B:COFT.0000037919.63750.9d

- Tiefer, L. (2007). Masturbation: Beyond caution, complacency and contradiction. Sexual and Marital Therapy, 13(1), 9–14. doi:10.1080/02674659808406539

- Townsend, J. M., Jonason, P. K., & Wasserman, T. H. (2019). Associations between motives for casual sex, depression, self-esteem, and sexual victimisation. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 49(4), 1189–1197.

- Waldinger, M. D. (2016). Post orgasmic illness syndrome (POIS). Translational Andrology and Urology, 5(4), 602–606. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.07.01

- Wentland, J. J., & Reissing, E. D. (2011). Taking casual sex not too casually: Exploring definitions of casual sexual relationships. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 20(3), 75–91.