ABSTRACT

Looting of archaeological sites and thefts from cultural institutions in the Middle East is driven by an international demand for artifacts. Despite the efforts of Ministries of Culture, Departments of Antiquities, cultural heritage NGOs, and local communities, landscapes are destroyed, sites are pillaged, and museums are ransacked across the region. Like other countries, Jordan has a demand driven looting problem rooted in the legal and illegal trade in cultural material from the Middle East (Kersel 2019b). Tourists, locals, and museums desire Jordanian artifacts, often without questioning their market appearance. In addition to the standard set of approaches to physically and legally protecting their cultural heritage, Jordan recently turned to diplomatic measures to curb the illegal movement of looted and stolen materials. In order to support their request for a bilateral cultural property agreement with the United States, Jordan is using data from drones, databases, and archaeologists to prove that looting is an ongoing concern and the purloined artifacts are destined for the US. Deploying a case study based on data from drones, in the following we demonstrate the power of archaeological research in national policy formation and international diplomacy.

Caring about Culture: American Cultural Diplomacy

On January 31, 2019, the US Department of State published official notification in the Federal Register of the receipt of a request from the Government of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to the Government of the United States of America to enter into a bilateral agreement to protect against the import of illegally exported Jordanian cultural materials (see US Federal Register Citation2019). Often the destination for stolen and looted archaeological objects, the US is a sought after party in diplomatic negotiations aimed at protecting the material remnants of the past. Any country who is a state party to the Citation1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transport of Ownership of Cultural Property (Citation1970 UNESCO Convention) and who can prove that their cultural landscapes and artifacts are at risk due to demand in the United States may request a bilateral agreement under the US implementing legislation, the Citation1983 Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CCPIA).

Most states parties to the 1970 UNESCO Convention recognize fully the export regulations of foreign nations with regard to cultural heritage. Gerstenblith (Citation2007b, 176 N. 28) explains that while in 1972 the US Senate voted unanimously to accept the Citation1970 UNESCO Convention in its entirety, “the implementing legislation was delayed for eleven years due largely to the objections of the art market community and of Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan.” Held up and severely curtailed, in 1983, the US eventually enacted the CCPIA implementing two substantive sections, article 7(b) and article 9, of the 1970 UNESCO Convention. Article 7b focuses on stolen but documented material in inventories of museums, religious, or secular public institutions in another state party. Article 9 focuses on ethnological materials and archaeological materials unlawfully excavated from archaeological sites, unknown until illegally uncovered. In anticipation of these unknowns, the CCPIA offers import restrictions for categories of material that might be the target of theft and plunder (Luke and Kersel Citation2013, 65). A basic tenet of the CCPIA is the notion that by stemming the movement of archaeological and ethnological materials between nations who are states parties to the 1970 UNESCO Convention, there will be fewer incidents of theft from storerooms and museums, and less pillaging of sites and destruction of landscapes. In addition to protecting the cultural heritage of a nation, these agreements can and do strengthen political relationships (see Luke and Kersel Citation2013). They can also promote cultural exchange in the forms of both knowledge through people-to-people relationships and the movement of archaeological objects: i.e., objects acting as ambassadors through museum exhibition (see Luke and Kersel Citation2013, 71–73). Luke (Citation2012, 113) suggests that the CCPIA “represents the most important visible component of American foreign policy when it comes to the Department of State engaging directly with cultural heritage preservation efforts abroad.”

To make a cultural property request under the CCPIA, the requesting nation, who must be a state party to the 1970 Convention, should address four determinations (19 U.S.C. § 2602) in a dossier submitted to the Cultural Heritage Center of the US Department of State (https://eca.state.gov/cultural-heritage-center/)(see Gerstenblith Citation2007a; Luke and Kersel Citation2013). The requesting country has to provide evidence of the following. First, they must establish that their cultural heritage is at risk from looting and theft. Second, they must offer proof of measures they are taking to prevent looting and to protect archaeological sites and objects. Third, they must demonstrate that an agreement with the US is one part of a multilateral effort to secure cultural property. And fourth, the imposition of import restrictions will further public interest in the international exchange of cultural materials (e.g., museum loans, knowledge through the exchange of students and experts) (see Gerstenblith Citation2007a; Luke and Kersel Citation2013). Once the dossier is compiled, a presidentially appointed Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) comprised of three members from the general public, three experts on the international sale of cultural property (dealers or collectors), two museum professionals, and three representatives from archaeology, anthropology, ethnology, or related fields reviews the report and associated documentation. The materials considered may include a public comment section, which gives interested individuals and organizations the opportunity to submit a letter and to speak before the committee in support of or against the import restrictions. After consideration of the dossier and public comments, the CPAC votes and makes a recommendation to the President or their delegated decision maker at the US Department of State. Agreements last for five years but can be renewed indefinitely (see Gerstenblith Citation2007a; Luke and Kersel Citation2013). As of January 2020 there are twenty such agreements. Emergency import restrictions for illegally exported cultural materials from Iraq and Syria were also applied, respectively, pursuant to UN Sec. Council Resolutions 1483 and 2199 and special legislation enacted by the US Congress in 2004 for Iraq and in 2016 for Syria (https://eca.state.gov/cultural-heritage-center/cultural-property-advisory-committee/current-import-restrictions). Offering proof in support of the four determinations can be a daunting task that imposes an additional burden on nations already vexed by looting and the illegal movement of their cultural materials (Gerstenblith Citation2007a, 50). This is where the data from archaeologists can and do play significant roles, particularly with regard to demonstrating that looting endangers sites.

Remote sensing technologies, site databases, and archaeological investigations provide some of the data necessary to support a request. At first glance connecting big data with diplomacy seems a stretch, because research data is typically conceptualized as what archaeologists produce as an element of their empirical examinations into past lifeways. Diplomacy, here in the form of a cultural property agreement between Jordan and the US, is supported by information gathered from several scales of big data imagery collection, recorded via satellite, full-scale aircraft, and drones. These data provide evidence of landscape change over time at a range of resolutions, all of which offer ample confirmation of looting and the need for a bilateral agreement. Despite the confidential nature of the dossier, the public summary (Cultural Heritage Center of the U.S. Department of State Citation2019) of the Jordanian request mentions specifically the invaluable drone work of the Landscapes of the Dead project in providing aerial data to satisfy some of the first requirements of a cultural property agreement (https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/jordan_public_summary.pdf). Data from drones is making a difference in diplomatic policy formation.

Evidence in Support of a Jordanian Bilateral Request

Establishing that the sites and objects are at risk from looting and theft involves extensive documentation, ground-truthing, and site monitoring. Aerial imagery (Lauricella et al. Citation2017) gathered from archival spy photographs (Hammer and Ur Citation2019,) drones (Kersel and Hill Citation2019), and satellites (Casana Citation2015; Casana and Panahipour Citation2014; Contreras and Brodie Citation2010a, Citation2010b; Morehart and Millhauser Citation2016; Parcak et al. Citation2016) provide a historical timeline of change over time of archaeological landscapes. These data offer comprehensive proof of the looting of archaeological sites, which when combined with evidence gathered from oral histories and ethnographic interviews (conducted after receiving the appropriate institutional review approval) on the movement of looted artifacts, and market analyses of the trade in archaeological materials can provide the necessary background for countries wishing to pursue bilateral agreements with the US.

The efforts of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities, national cultural heritage NGOs, and local communities notwithstanding, ongoing landscape destruction due to the looting of archaeological sites in the search for salable artifacts is well-documented across Jordan (see al-al-Bqāʿīn, Corbett, and Khamis Citation2015; Bisheh Citation2001; Brodie Citation1998; Brodie and Contreras Citation2012; Contreras and Brodie Citation2010a, Citation2010b; Kersel Citation2019b; Kersel and Chesson Citation2013; McCreery Citation1996; Papadopoulos, Kontorli-Papadopoulou, and Politis Citation2001; Politis Citation2002; Rose and Burke Citation2004). Historically, a variety of methods have been used to record site looting in Jordan, including a national database (MEGA-Jordan), archaeological site survey and ground-truthing, oral histories, satellite and aerial imagery. The dossier could draw from any or all of those data to support the Jordanian request for a cultural property Memorandum of Understanding.

Data from Databases and Diggers: Jordan Antiquities Database and Information System (JADIS) and MEGA-Jordan

While there are a number of online archaeological databases (see the Corona Atlas of the Middle East (Casana and Cothren Citation2013), the Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East - APAAME (Bewley et al. Citation2010), the Digital Archaeological Atlas of the Holy Land - DAAHL (Savage and Levy Citation2014), and the Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa - EAMENA (Bewley et al. Citation2016), Jordan is a pioneer among Middle Eastern countries in creating and maintaining a purpose-built, state-of-the-art geographic information system (GIS) and database for inventorying and managing archaeological sites on a national level (Drzewiecki and Arinat Citation2017). Launched by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities (DoA) in 1990, the objectives of the Jordan Antiquities Database and Information System (JADIS) include an inventory of known archaeological sites (through published and unpublished reports) and maps of grid coordinates, which allow for vigorous data searches and the facilitation of the exchange of information between the DoA and other governmental agencies and ministries in order to protect the cultural heritage of the Kingdom (Palumbo Citation1992). During the 1990s, with financial and logistical assistance from the American Center for Oriental Research (ACOR) and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Cultural Resources Management Project of the Jordanian DoA was established with a set of priorities, which includes a system to record the nation’s archaeological sites (JADIS). Not designed to answer specific research questions, the database serves as a rapid response tool for monitoring sites threatened by development, looting, and other negative landscape interactions, available to all who want access (Palumbo Citation1992). The fundamental premise is to reduce the risk of construction projects inadvertently impacting archaeological sites, thus diminishing the need for salvage projects (Palumbo Citation1992, 187). Data from JADIS allow for the production of “risk maps” which contain information on archaeological sites in areas with proposed construction and infrastructure work. An unintended, but positive, consequence of this national database is as a research tool for scholars interested in assessing site distribution patterning. Using JADIS, the DoA is able to assess lacunae in the archaeological record; identifying sites and regions in need of future investigation.

JADIS, in use until 2002, was replaced in 2010 by the Middle Eastern Geodatabase for Antiquities – Jordan (MEGA-Jordan), a collaboration between the Jordanian DoA, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the World Monuments Fund. Adopting and augmenting many of the goals of JADIS, in both Arabic and English the web-based MEGA-Jordan system standardizes and centralizes data throughout the Kingdom. MEGA-Jordan tracks reported threats, disturbances, and legal violations involving the illegal excavation of sites and removal of artifacts. As an element of the final reporting requirements for a season of fieldwork, archaeological excavation and survey permit holders (foreign and local) are required to report site disturbances and instances of looting in MEGA-Jordan. Creating a polygon around the site or encompassing the survey area users mark looting. Reports also include UTM coordinates for the looting, a description, and accompanying images. MEGA-Jordan uses these data to generate an up-to-date list of episodes, which assists in targeted site protection efforts and local policy formation on maintaining landscapes. Utilizing information from MEGA-Jordan, the Jordanian DoA is in part fulfilling Determination # 2 of the MoU request by establishing their efforts to assess, monitor, and safeguard the cultural heritage of the Kingdom.

As a component in support of the request for a MoU with the US, Jordan has to prove that their cultural heritage is at risk from looting and theft (Determination # 1). Currently the MEGA-Jordan database lists 425 sites, ranging from the Palaeolithic to the Islamic periods that have been subject to looting, theft, or illegal digging. Thus data (gathered from archaeologists) from MEGA-Jordan deliver comprehensive and compelling statistics about endangered sites and landscapes for consideration by the CPAC. In an assessment of the efficacy of online databases from the Middle East, Drzewiecki and Arinat (Citation2017, 76) suggest “databases have proved an irreplaceable tool for the Jordanian Department of Antiquities, allowing them to record and keep track of the condition of cultural heritage sites.” These data are essential in providing a compendium of records of Jordan’s efforts to record, monitor, and subsequently protect their past when a threat is identified. In addition to data from databases, aerial images add to the mounting evidence in support of the Jordan bilateral request.

Data from Aerial Imagery

The value of remote sensing in identifying and analyzing looting is well established in Afghanistan (Franklin and Hammer Citation2018; Lauricella et al. Citation2017), Egypt (Parcak Citation2015), Iraq (Hanson Citation2012; Hritz Citation2008; Stone Citation2008), Mexico (Morehart and Millhauser Citation2016), Peru (Contreras Citation2010; Lasaponara et al. Citation2014), Syria (Casana and Panahipour Citation2014; Cunliffe Citation2014; Tapete, Cigna, and Donoghue Citation2016) and in Yemen (Banks et al. Citation2017). The breadth of data on the spatial and temporal patterns in these publications suggest that looting is not confined to areas of unrest and conflict, supporting the notion that looting is a demand driven enterprise, resulting in a much wider phenomenon occurrence (Tapete and Cigna Citation2019). Drawing from these studies and evidence from MEGA-Jordan, research into looting in Jordan has burgeoned in the last decade. Building upon a deep-rooted tradition of aerial photography in Jordan (see the work of the Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East [APAAME] directed by David Kennedy and Robert Bewley and the associated Endangered Archaeology of the Middle East and North Africa [EAMENA] Project), several research projects continue to document the ongoing looting of sites in Jordan using both aerial and satellite imagery remote sensing technologies (Bewley et al. Citation2016; Contreras and Brodie Citation2010a, Citation2010b; Kersel and Hill Citation2019). This abundance of aerial data in Jordan led Contreras and Brodie (Citation2010b, 103) to conclude “[t]he archaeology of Jordan has perhaps been photographed from the air more than that of any other country … ”

Established in 1978, APAAME is using historic and contemporary photographic images to discover, record, monitor, and investigate settlement patterns in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, with a particular focus on Jordan (http://www.apaame.org/). The annual program of helicopter flights, carried out in cooperation with the Royal Jordanian Air Force, allows project directors Kennedy and Bewley, to photograph archaeological sites across the Kingdom. Many of these yearly images include documentation of looting and site destruction, which offer the opportunity for ongoing evaluation of change over time. Enhancing their photographic analyses with satellite imagery, APAAME recently started a new phase of landscape chronicling by collaborating with the EAMENA Project (http://eamena.arch.ox.ac.uk/). The EAMENA Project relies heavily on the analysis of freely available imagery provided via platforms such as Google Earth© and Bing Maps© (Zerbini and Fradley Citation2018, 15). Using these data, researchers from EAMENA interpret both satellite imagery and historical aerial photography, like those from APAAME, to study landscape transformation and to record the current state of archaeological sites (Bewley et al. Citation2016).

Data from satellites, full-scale aircraft, and Unpiloted Aerial Vehicles (UAVs, or drones) provide complementary benefits to researchers and policy makers interested in documenting damage to archaeological sites and landscapes. Satellite imagery affords the broadest coverage, but at great expense and (relatively) low resolution. While satellite imagery has been used extensively to document looting, it is often only able to pick out evidence for looting on the largest scale. Aerial imagery from full-scale aircraft can provide higher resolution imagery compared to satellite imagery and in a more consistent time frame, but is similarly expensive and logistically challenging. UAVs have the most limited aerial coverage (due to limited battery life, flight restrictions, and sensor size), but the tradeoffs are cheap, reproducible surveys at extremely high ground resolution. The low cost and ease of recording of site-level data with drones means that researchers can potentially record high resolution data as often as necessary, whenever needed. This ability to replicate surveys with greater frequency means drones have the potential to record much higher temporal resolution than would be possible with monitoring from satellites or full-scale aircraft.

UAVs are now commonly used to document archaeological excavations (Colomina and Molina Citation2014; Olson et al. Citation2013; Rinaudo et al. Citation2012; Roosevelt et al. Citation2015) and landscapes (Campana Citation2017; Harrower Citation2018; Stek Citation2016; Verhoeven Citation2009), as well as for site prospection using thermal and near infrared sensors (Casana et al. Citation2014; Casana et al. Citation2017). But UAVs can also provide powerful change over time data that can be valuable in assessing, monitoring, and quantifying looting (Kersel and Hill Citation2019). Although still rare in archaeology, this sort of change detection has been used in other fields to identify landscape alterations (Casella et al. Citation2016; Turner, Harley, and Drummond Citation2016). The exceedingly high-resolution imagery used for distinguishing transformations at ground and temporal resolutions would be difficult or impossible to match with satellites or full-scale aircraft. Recognizing the merits of UAVs and the limitations of satellite imagery (see Tapete and Cigna Citation2019), in collaboration with the Jordanian DoA, the Landscapes of the Dead Research Project (LOD) is using data generated from UAVs to study the scale and pace of natural and cultural landscape modification at the Early Bronze Age (3600–2000 B.C.E.) mortuary sites of Bab adh-Dhra’ and Fifa ( and ).

Data from the Landscapes of the Dead (LOD)

In a letter to the CPAC, the body charged with making the recommendation on whether or not to enter into a bilateral agreement with a particular nation, Kersel (Citation2019a) addressed the various determinations using results from the integrated approach of the LOD. Directed by the authors, the LOD project is a mixture of pedestrian survey, spatial data from UAV surveys, and oral histories with the multiple populations who encounter the site and its artifacts (see Kersel and Hill Citation2019). This wide-ranging approach allows for the examination of landscape change over time, while at the same time assessing the impact of the Jordanian DoA protection initiatives anti-looting campaigns, national laws, and local community outreach programs, and the impact of Petra National Trust (PNT) educational programming (Kersel Citation2016).

There is ample scholarship on the desire for archaeological artifacts related to the people and places of the bible (for a few examples see Kaell Citation2012; Kersel Citation2014; Shenhav-Keller Citation1993; Wharton Citation2006). This ongoing demand has resulted in the pillaging of archaeological sites from across the region, including five sites from the Early Bronze Age (3600–2000 B.C.E.) along the east side of the Dead Sea that some have identified as the “Cities of the Plain” mentioned in Genesis 13:12. One of the sites, Bab adh-Dhra’ (), a town with an associated cemetery, is considered by some to be biblical Sodom (Rast Citation1987); “everyone wants a pot from the city of sin” (Tourist 23), as one interviewee stated when asked about their demand for a pot from Early Bronze Age Jordan. Bab adh-Dhra’ () has been the focus of looting and subsequent site protection strategies as early as the 1920s (Rast and Schaub Citation1974). A standard mortuary toolkit (see Kersel and Chesson Citation2013), including several ceramic vessels, accompanies people buried at the Dead Sea sites during the EBA (see for a 3D model of a looted cist tomb from Fifa). Through a complex network of looters, intermediaries, and dealers, much sought-after ceramic vessels looted in Jordan make their way into the legal market for antiquities in Israel available for purchase and export (see Kersel Citation2014).

Figure 3. Still from a 3D model of a looted stone-lined tomb at the site of Fifa. A 3D version of this figure is available in the online version of the article here: https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1713282.

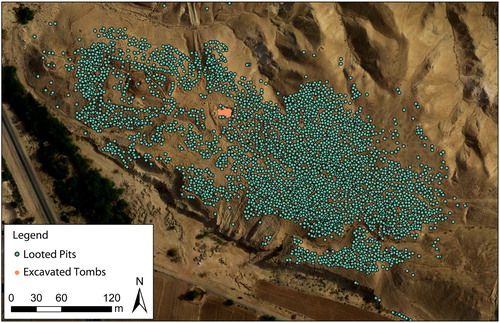

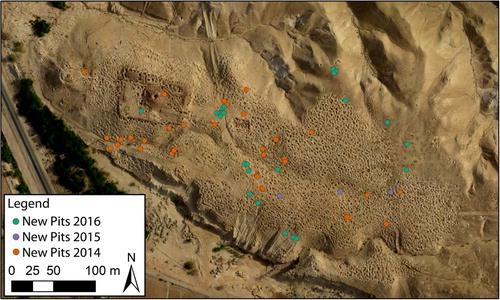

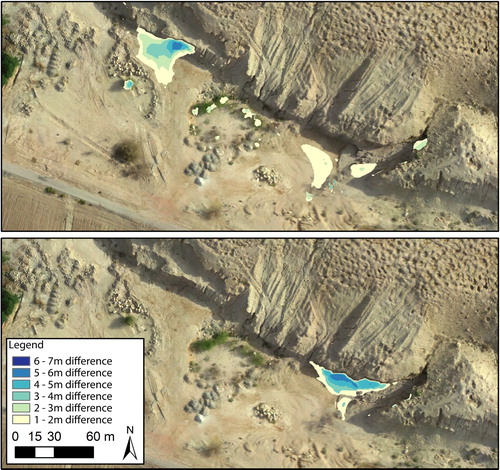

Four seasons of aerial survey at the site of Fifa, an EBA IA cemetery site identified as one of the so called “Cities of the Plain,” have provided several take-home messages about looting in the region. These results reinforce similar statistical findings of Contreras and Brodie (Citation2010b) from their Google Earth© analyses of Bab adh-Dhra’, but at significantly higher spatial and temporal resolution. Looting at Fifa had never been properly documented, so as an initial element of the LOD project, a base map of the site, constructed from the drone data (see ), was used to quantify all of the existing holes. Additionally, UAV-generated data allow for the production of accurately georeferenced orthophotographs and Digital Elevations Models (DEMs) that are compared from one year to the next. High-resolution orthophotographs allow for a careful documentation of images illustrating the 3723 looters’ pits present at the site (see and ). New looting was detected in the drone images by visual inspection (for instance new pits could often be identified by fresh (moist) dirt) and via changes in elevation due to the digging of new looting pits and the related creation of new back dirt piles. This change over time elevation detection was accomplished by subtracting one annual DEM raster from another, resulting in a difference map that showed new pits as a large “negative” change and the associated backdirt from a new pit as a large “positive” change in elevation.

During the UAV surveys, some looting could be identified in near real time by comparing new imagery to old imagery, allowing for the immediate ground-truthing of patterns and anomalies noticed in the aerial images. In one instance a strange red dot was noted in an image processed in the evening after a day of UAV flyovers. Returning to the site the following morning using the UAV image as a guide a discarded watermelon rind was recorded at the site of new looting. Looters targeting a cist tomb had a watermelon snack during their escapades. In the span of twenty-four hours an anomaly was recorded from the drone, the UAV-generated data were processed, and the site ground-truthed, adding to the panoply of available site information. Looting patterns and other incongruities identified during post-survey processing of the drone data and analysis in GIS are all assessed through a pedestrian survey in subsequent seasons (see Kersel and Hill Citation2019). Significant and unexpected damage to the site in the form of gravel quarrying was identified by a combination of the high resolution, accurate change over time DEM data () followed by direct inspection on the ground (). This type of damage is not the focus of the survey and could easily have been missed by only looking at aerial or satellite photographs. Quarrying is an added factor in the destruction of intact cist tombs at the site. In these instances, researchers could walk around the landscape with aerial images in hand to check on and confirm identified changes, an acknowledged advantage of working in the stable political environment in Jordan.

Figure 4. Negative elevation change on the southern edge Fifa between 2014–2015 (top) and 2015–2016 (bottom) due to gravel quarrying.

Figure 5. Photograph looking at the southern edge of Fifa, where parallel vertical grooves indicate quarrying activity via backhoe.

Using publicly available and easy-to-use satellite imagery via Google Earth© and a robust statistical methodology to create an estimate of the archaeological damage caused by looting at the Early Bronze Age site of Bab adh-Dhra’, Contreras and Brodie (Citation2010b) produced some amazing estimates for the cumulative economic outcomes of all looting activity at that site. In order to quantify looting at Bab adh-Dhra’ (see ) Contreras and Brodie (Citation2010b) required the following information:

a = the total area looted (sq m); c = the number of burial chambers per sq m; and p = the mean number of pots per burial chamber. With those data it was possible to calculate: c X a X p = total number of chambers damaged by looting and c X a X p = total number of pots looted, which resulted in an estimate of 1190 looted burial chambers at Bab adh-Dhra’ (Contreras and Brodie Citation2010b, 107–108).

The LOD project provides more nuanced data about the continuing destruction of the site of Fifa. Recording sixty-one new holes between 2013 and 2016 demonstrates that despite all appearances to the contrary there are intact tombs left to loot at the site and looting is a continuing concern (). Most satellite-based methods are limited by the resolution of the imagery. “Since image resolution was generally not adequate to allow counting of individual pits and thus direct estimates of pit number and density, we instead approximated total looted area, bounding the visibly disturbed areas;” Contreras and Brodie (Citation2010b, 106), using imagery from Google Earth© are unable to identify individual looting episodes. Instead, Contreras and Brodie (Citation2010a, Citation2010b) estimate the number of looted burial chambers by drawing polygons over areas of sites that appeared to be damaged by looting pits. Drawing polygons at Fifa for the years 2013–2016 would show no new looting damage, because the total looted area did not change over this time span. All new looting pits were contained within the previously looted area (see for dots marking the spots of new looting in the already pitted area). Instead, the combination of high-resolution imagery and 3D data allowed us to detect individual new pits from year to year. Additional impediments to satellite image analysis include a lag in refresh rates of Google Earth©. Images from the Dead Sea area have not been updated since 2012. Given that Fifa is some 5 kms (less than 3 miles) from the border with Israel all satellite imagery may also be subject to the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (Section 1064, Public Law 104-201) to the 1997 US National Defense Authorization Act which limits “the availability of high-resolution satellite imagery over Israel and Palestine” (Zerbini and Fradley Citation2018, 14). Demonstrably, using UAVs to track the annual rate of looting rather than simply estimating the total cumulative damage is a better indicator of the ongoing problem and with some training in UAV flying, something that the Jordanian DoA could take on as a relatively low-cost but fine-grained element of site monitoring.

Typically, researchers employing satellite-based assessments of looting recognize and acknowledge the limitations of the images under investigation (Tapete and Cigna Citation2019). But in tandem with data from databases, archaeologists, and drones, satellite imagery studies provide evidence in support of the Jordanian request for a cultural property Memorandum of Understanding with the United States. The suite of data documenting looting offer ample evidence in support of Determination # 1, that the cultural heritage of the requesting nation is at risk from looting and theft. Remote sensing data at multiple scales and national site databases provide Jordan with the data necessary to detail the pillage of archaeological sites, an essential step in the bilateral agreement process.

Big Data and Diplomatic Success

On April 1, 2019, during the public session of the Jordanian bilateral agreement request Kersel, representing the Landscapes of the Dead research project, the Archaeological Institute of America, and the Society for American Archaeology, provided expert testimony before the CPAC as they considered the Jordanian request. In her letter and in her public statement Kersel stated, “I believe that a bilateral agreement between the US and Jordan will raise the profile of cultural heritage protection in the consciousness of the Jordanian Parliament, which in turn may result in an allocation of greater resources to the Department of Antiquities” (Kersel Citation2019a). The Jordanian DoA, armed with data from MEGA-Jordan and the LOD, might use increased governmental resources for additional archaeological site protection and monitoring, which would result in fewer incidents of looting.

Without a doubt, data from databases, drones, and diggers were persuasive elements in deciding that Jordanian cultural heritage is in jeopardy and that US import restrictions will help to deter the serious situation of pillage. After reviewing the dossier, interviewing experts during the public session, and meeting with representatives from the Jordanian government, the CPAC deliberated on the evidence presented. On Monday December 16, 2019, the Government of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the Government of the United States of America signed the MoU. In her remarks, Assistant US Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs Marie Royce, stated “[T]he broader goals of the agreement include reducing the incentive to pillage archaeological and cultural sites, aiding in preserving Jordan’s heritage and paving the way for artefact loans, exhibitions and virtual cultural exchanges between the two countries” (Keziah Citation2019). This cultural property agreement between Jordan and the US is the embodiment of cultural diplomacy writ large as both countries agree that the cultural heritage of Jordan is at risk from buyers in the United States.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Andrew Dufton and Parker VanValkenburgh for putting together the SAA session on Big Data. We are delighted to present the big data work we have been doing in Jordan, which would not be possible without the support of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, Meredith S. Chesson, Mohammad Zahran, Jameelah Ishtawy, Mohammad Najjar, and the communities of the Ghor es-Safi region. Funds for this project came from DePaul University and Rick Witschonke. Our thanks to the session respondent Mark McCoy, Patty Gerstenblith, Yorke Rowan, and anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments and suggestions. This paper is dedicated to Andrea Zerbini, a diligent advocate for the use of remote sensing in cultural heritage protection in the MENA region.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on Contributors

Morag M. Kersel (Ph.D. 2006, University of Cambridge) is Associate Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Museum Studies Minor at DePaul University. Her interests include the prehistory of the Levant, cultural heritage policy and law, and the trade in antiquities.

Austin Chad Hill (Ph.D. 2011, University of Connecticut) is an archaeologist specializing in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based remote sensing. Chad uses aerial photography and 3D photogrammetry, employing visible and multispectral imaging, to identify archaeological sites, document excavations, and visualize landscapes.

ORCID

Morag M. Kersel http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9254-0957

Austin (Chad) Hill http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8397-8105

References

- al-Bqāʿīn, F., G. J. Corbett, and E. Khamis. 2015. “An Umayyad Era Mosque and Desert Waystation from Wadi Shīreh, Southern Jordan.” Journal of Islamic Archaeology 2 (1): 93–126. doi: 10.1558/jia.v2i1.26940

- Banks, R., M. Fradley, J. Schiettecatte, and A. Zerbini. 2017. “An Integrated Approach to Surveying the Archaeological Landscapes of Yemen.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 47: 9–24.

- Bewley, B., D. Kennedy, F. Radcliffe, K. Henderson, and S. Smith. 2010. “Aerial Archaeology in Jordan 2010: A Brief up-Date.” The Newsletter of the Aerial Archaeology Research Group 41: 13–24.

- Bewley, R., A. I. Wilson, D. Kennedy, D. Mattingly, R. Banks, M. Bishop, J. Bradbury, et al. 2016. “Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa: Introducing the EAMENA Project.” In CAA2015. Keep the Revolution Going: Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, edited by S. Campana, R. Scopigno, G. Carpentiero, and M. Cirillo, 919–932. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology.

- Bisheh, G. 2001. “One Damn Illicit Excavation After Another: The Destruction of the Archaeological Heritage in Jordan.” In Trade in Illicit Antiquities: The Destruction of the World’s Archaeological Heritage, edited by N. J. Brodie, J. Doole, and A. C. Renfrew, 115–118. Cambridge, UK: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

- Brodie, N. J. 1998. “Pity the Poor Middlemen.” Culture Without Context 3 (Autumn): 4–6.

- Brodie, N. J., and D. Contreras. 2012. “The Economics of the Looted Archaeological Site of Bâb edh-Dhrâ’: a View from Google Earth.” In All The Kings Horses: Looting, Antiquities Trafficking and the Integrity of the Archaeological Record, edited by P. K. Lazrus and A. Barker, 9–24. Washington DC: Society for American Archaeology.

- Campana, S. 2017. “Drones in Archaeology. State-of-the-art and Future Perspectives.” Archaeological Prospection 24 (4): 275–296. doi: 10.1002/arp.1569

- Casana, J. 2015. “Satellite Imagery-Based Analysis of Archaeological Looting in Syria.” Near Eastern Archaeology 78 (3): 142–152. doi: 10.5615/neareastarch.78.3.0142

- Casana, J., and J. Cothren. 2013. “The CORONA Atlas Project: Orthorectification of CORONA Satellite Imagery and Regional-Scale Archaeological Exploration in the Near East.” In Mapping Archaeological Landscapes from Space, edited by D. Comer and M. J. Harrower, 33–43. London: Springer.

- Casana, J., J. Kantner, A. Wiewel, and J. Cothren. 2014. “Archaeological Aerial Thermography: a Case Study at the Chaco-era Blue J Community, New Mexico.” Journal of Archaeological Science 45: 207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2014.02.015

- Casana, J., and M. Panahipour. 2014. “Notes on a Disappearing Past: Satellite-Based Monitoring of Looting and Damage to Archaeological Sites in Syria.” Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 2 (2): 128–151. doi: 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.2.2.0128

- Casana, J., A. Wiewel, A. Cool, and A. C. Hill. 2017. “Archaeological Aerial Thermography in Theory and Practice.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 5 (4): 310–327. doi: 10.1017/aap.2017.23

- Casella, E., A. Rovere, A. Pedroncini, C. Stark, M. Casella, M. Ferrari, and M. Firpo. 2016. “Drones as Tools for Monitoring Beach Topography Changes in the Ligurian Sea (NW Mediterranean).” Geo-Marine Letter 36 (2): 151–163. doi: 10.1007/s00367-016-0435-9

- Colomina, I., and P. Molina. 2014. “Unmanned Aerial Systems for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing: a Review.” ISPRS Journal of Remote Sensing 92: 79–97. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2014.02.013

- Contreras, D. 2010. “Huaqueros and Remote Sensing Imagery: Assessing Looting Damage in the Virú.” Antiquity 84 (324): 544–555. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X0006676X

- Contreras, D., and N. J. Brodie. 2010a. “Shining Light on Looting: Using Google Earth to Quantify Damage and Raise Public Awareness.” SAA Archaeological Record 10: 30–33.

- Contreras, D., and N. J. Brodie. 2010b. “The Utility of Publicly Available Satellite Imagery for Investigating Looting of Archaeological Sites in Jordan.” Journal of Field Archaeology 35 (1): 101–114. doi: 10.1179/009346910X12707320296838

- Cunliffe, E. 2014. “Archaeological Site Damage in the Cycle of war and Peace: A Syrian Case Study.” Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 2 (3): 229–247. doi: 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.2.3.0229

- Cultural Heritage Center of the U.S. Department of State. 2019. Public Summary. Request by the Government of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to the Government of The United States of America for Imposing Import Restrictions to Protect its Cultural Patrimony under Article 9 of the UNESCO Convention (1970). January 31, 2019. https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/jordan_public_summary.pdf.

- Drzewiecki, M., and M. Arinat. 2017. “The Impact of Online Archaeological Databases on Research and Heritage Protection in Jordan.” Levant 49 (1): 64–77. doi: 10.1080/00758914.2017.1308117

- Franklin, K., and E. Hammer. 2018. “Untangling Palimpsest Landscapes in Conflict Zones: A “Remote Survey” in Spin Boldak, Southeast Afghanistan.” Journal of Field Archaeology 43 (1): 58–73. doi: 10.1080/00934690.2017.1414522

- Gerstenblith, P. 2007a. “The Acquisition and Presentation of Classical Antiquities: The Legal Perspective.” In The Acquisition and Exhibition of Classical Antiquities. Professional, Legal, and Ethical Perspectives, edited by R. F. Rhodes, 47–60. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Gerstenblith, P. 2007b. “Controlling the International Market in Antiquities: Reducing the Harm, Preserving the Past.” Chicago Journal of International Law 8 (1): 69–195.

- Hammer, E., and J. Ur. 2019. “Near Eastern Landscapes and Declassified U2 Aerial Imagery.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 7 (2): 107–126. doi: 10.1017/aap.2018.38

- Hanson, K. 2012. Considerations of Cultural Heritage: Threats to Mesopotamian Archaeological Sites. Unpublished Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

- Harrower, M. J. 2018. “Spatial Archaeology, Hydrology and the Historical Dynamics of Water in Ancient Southern Arabia (Yemen and Oman).” In Water and Power in Past Societies, edited by E. Holt, 159–176. Albany, NY: University of Buffalo.

- Hritz, C. 2008. “‘‘Remote Sensing of Cultural Heritage in Iraq: A Case Study of Isin.’” TAARII Newsletter 3: 1–8.

- Kaell, H. 2012. “Of Gifts and Grandchildren: American Holy Land Souvenirs.” Journal of Material Culture 17 (2): 133–151. doi: 10.1177/1359183512443166

- Kersel, M. M. 2014. “The Lure of the Artefact? The Effects of Acquiring Eastern Mediterranean Material Culture.” In The Cambridge Prehistory of the Bronze and Iron Age Mediterranean, edited by A. B. Knapp and P. van Dommelen, 367–378. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kersel, M. M. 2016. “Go Do Good! Responsibility and the Future of Cultural Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 21st Century.” In The Future of the Past: From Amphipolis to Mosul, New Approaches to Cultural Heritage Preservation in the Eastern Mediterranean, edited by K. Chalikias, M. Beeler, A. Pearce, and S. Renette, 5–10. AIA Heritage, Conservation, and Archaeology Series. Boston: Archaeological Institute of America.

- Kersel, M. M. 2019a. Public Comment on the Cultural Property Agreement Request by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to the United States, March 25, 2019. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=DOS-2019-0004-0018

- Kersel, M. M. 2019b. “Itinerant Objects. The Legal Lives of Levantine Artifacts.” In The Social Archaeology of the Levant, edited by A. Yasur-Landau, E. H. Cline, and Y. M. Rowan, 594–612. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kersel, M. M., and M. S. Chesson. 2013. “Looting Matters. Early Bronze age Cemeteries of Jordan's Southeast Dead Sea Plain in the Past and Present.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial, edited by S. Tarlow and L. Nilsson Stutz, 677–694. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kersel, M. M., and A. C. Hill. 2019. “The (W)Hole Picture: Responses to a Looted Landscape.” International Journal of Cultural Property 26 (3): 305–329. doi: 10.1017/S0940739119000195

- Keziah, P. 2019. “Jordan US ink Agreement to Curb Artefact Smuggling.” The Jordan Times Tuesday December 17, 2019. https://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-us-ink-agreement-curb-artefact-smuggling

- Lasaponara, R., G. Leucci, N. Masini, and R. Persico. 2014. “Investigating Archaeological Looting using Satellite Images and GEORADAR: the Experience in Lambayeque in North Peru.” Journal of Archaeological Science 42: 216–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.10.032

- Lauricella, A., J. Cannon, S. Branting, and E. Hammer. 2017. “Semi-automated Detection of Looting in Afghanistan using Multispectral Imagery and Principal Component Analysis.” Antiquity 91 (359): 1344–1355. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2017.90

- Luke, C. 2012. “The Science Behind United States Smart Power in Honduras: Archaeological Heritage Diplomacy.” Diplomacy & Statecraft 23 (1): 110–139. doi: 10.1080/09592296.2012.651965

- Luke, C., and M. M. Kersel. 2013. U.S. Cultural Diplomacy and Archaeology. Soft Power, Hard Heritage. London: Routledge.

- McCreery, D. W. 1996. “A Salvage Operation at Ba ¯b adh-Dhra.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan (ADAJ) 40: 51–62.

- Morehart, C., and J. Millhauser. 2016. “Monitoring Cultural Landscapes from Space: Evaluating Archaeological Sites in the Basin of Mexico using Very High Resolution Satellite Imagery.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 10: 363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.11.005

- Najjar, M. 2001. “As-Safi and Fifa – Al-Karak District.” Munjazat of the Department of Antiquities 38.

- Olson, B., R. Placchetti, J. Quartermaine, and A. Killebrew. 2013. “The Tel Akko Total Archaeology Project (Akko, Israel): Assessing the Suitability of Multi-Scale 3D Field Recording in Archaeology.” Journal of Field Archaeology 38 (3): 244–262. doi: 10.1179/0093469013Z.00000000056

- Palumbo, G. 1992. “JADIS (Jordan Antiquities Database and Information System): An Example of National Archaeological Inventory and GIS Applications.” In Computing the Past. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (Proceedings 1992), edited by J. Andresen, T. Madsen, and I. Scollar, 183–188. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Papadopoulos, T. J., L. Kontorli-Papadopoulou, and K. D. Politis. 2001. “‘Rescue Excavations at An-Naq’ and Tulaylat Qasr Musa al-Hamid 2000.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan (ADAJ) 45: 189–193.

- Parcak, S. 2015. “Archaeological Looting in Egypt: A Geospatial View (Case Studies from Saqqara, Lisht, and el Hibeh).” Near Eastern Archaeology 78 (3): 196–203. doi: 10.5615/neareastarch.78.3.0196

- Parcak, S., D. Gathings, C. Childs, G. Mumford, and E. Cline. 2016. “Satellite Evidence of Archaeological Site Looting in Egypt: 2002–2013.” Antiquity 90 (349): 188–205. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2016.1

- Politis, K. 2002. “Dealing with the Dealers and Tomb Robbers: The Realities of the Archaeology of the Ghor es-Safi in Jordan.” In Illicit Antiquities: The Theft of Culture and the Extinction of Archaeology, edited by N. J. Brodie and K. Walker Tubb, 257–267. London: Routledge.

- Rast, W. 1987. “Bab Edh-Dhraʿ and the Origin of the Sodom Saga.” In Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation: Essays in Memory of D. Glenn Rose, edited by L. Perdue, L. Toombs, and G. Johnson, 185–201. Atlanta, GA: Knox.

- Rast, W., and R. T. Schaub. 1974. “Survey of the Southeastern Plain of the Dead Sea, 1973.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan (ADAJ 19: 5–53.

- Rast, W., and R. T. Schaub. 1990. “Final Report on the Excavations at Fifa.” In National Endowment for the Humanities. Washington, DC.

- Rinaudo, F., F. Chiabrando, A. Lingua, and A. Span. 2012. “Archaeological Site Monitoring: UAV Photogrammetry can be an Answer.” International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences XXXIX-B5: 583–588. doi: 10.5194/isprsarchives-XXXIX-B5-583-2012

- Roosevelt, C., P. Cobb, E. Moss, B. Olson, and S. Ünlüsoy. 2015. “Excavation is Destruction Digitization: Advances in Archaeological Practice.” Journal of Field Archaeology 40 (3): 325–346. doi: 10.1179/2042458215Y.0000000004

- Rose, Jerome, and Dolores Burke. 2004. “Making Money From Buried Treasure.” Culture Without Context 14: 4–8.

- Savage, S., and T. E. Levy. 2014. “DAAHL – The Digital Archaeological Atlas of the Holy Land: A Model for Mediterranean and World Archaeology.” Near Eastern Archaeology 73 (3): 243–247. doi: 10.5615/neareastarch.77.3.0243

- Shenhav-Keller, S. 1993. “The Israeli Souvenir: Its Text and Context.” Annals of Tourism Research 20 (1): 182–196. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(93)90117-L

- Stek, T. 2016. “Drones Over Mediterranean Landscapes. The Potential of Small UAV’s (Drones) for Site Detection and Heritage Management in Archaeological Survey Projects: A Case Study from Le Pianelle in the Tappino Valley, Molise (Italy).” Journal of Cultural Heritage 22: 1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.culher.2016.06.006

- Stone, E. 2008. “Patterns of Looting in Southern Iraq.” Antiquity 82 (315): 125–138. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00096496

- Tapete, D., and F. Cigna. 2019. “Detection of Archaeological Looting from Space: Methods, Achievements and Challenges.” Remote Sensing 11 (2389), https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11202389.

- Tapete, D., F. Cigna, and D. N. Donoghue. 2016. “Looting Marks’ in Space-Borne SAR Imagery: Measuring Rates of Archaeological Looting in Apamea (Syria) with TerraSAR-X Staring Spotlight.” Remote Sensing of Environment 178 (1): 42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2016.02.055

- Turner, I., M. D. Harley, and C. D. Drummond. 2016. “UAVS for Coastal Surveying.” Coastal Engineering 114: 19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.coastaleng.2016.03.011

- UNESCO. 1970. UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transport of Ownership of Cultural Property. Paris.

- United States Congress. 1983. Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act. 19 U.S.C. § 2602.

- United States Federal Register. 2019. “Notice of Receipt of Request From the Government of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Under Article 9 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.” Federal Register, January 31, 2019. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/01/31/2019-00517/notice-of-receipt-of-request-from-the-government-of-the-hashemite-kingdom-of-jordan-under-article-9

- Verhoeven, G. J. J. 2009. “Providing an Archaeological Bird's-eye View—an Overall Picture of Ground-Based Means to Execute low-Altitude Aerial Photography (LAAP) in Archaeology.” Archaeological Prospection 16 (4): 233–249. doi: 10.1002/arp.354

- Wharton, A. J. 2006. Selling Jerusalem: Relics, Replicas, Themeparks. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Zerbini, A., and M. Fradley. 2018. “Higher Resolution Satellite Imagery of Israel and Palestine: Reassessing the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment.” Journal of Space Policy 44-45: 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2018.03.002.