ABSTRACT

Archaeological spatial databases have the potential to enable deep insights into human history. These compilations of data are at the interface of data management and data visualization. Yet issues of data governance such as the nature, management, quality, ownership, security, and accessibility of archaeological spatial databases are under examined in archaeology, a situation that can affect data intensive methods and “big” data approaches. Data governance including laws and policies associated with data have bearing on archaeological practices which, in turn, can impact map visualizations and subsequent decision-making. With the growth of the geospatial web and Web 2.0 technologies, there are increasing opportunities for archaeologists and the general public to collect and engage with digital archaeological data. In Canada, greater numbers of specialists from different sectors (research and education, government, private companies) now accumulate, store, and process digital archaeological data. We draw from the OCAP® (ownership, control, access, possession) principles to shed light on data governance in archaeology, with a focus on archaeological spatial databases in Canadian archaeology. In this context, we draw attention to the rights of Indigenous peoples, the legal and policy issues associated with archaeological spatial databases, and a need for greater engagement with Indigenous data governance principles.

Introduction

Data governance is broadly defined as the “system of decision rights and responsibilities that describe who can take what actions with what data, when, under what circumstances, and using what methods” (Smith, Cruse, and Michener Citation2011, 2). The data governance framework includes knowledge making and strategies for data management, preservation and curation, accessibility, quality issues, as well as legal and policy concerns over data ownership and data security. These practices impact data discovery and thus processes and actions affecting the data are highlighted as specialists and the general public engage in the collection, sharing, and re-use of digital geospatial data. Open Data initiatives, for example, seek to make data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, based on the FAIR principles (Wilkinson et al. Citation2016). While fruitful, these data-centric efforts have obscured the impacts of colonialism on the practice of science, and have overlooked the interests and rights of Indigenous peoples when it comes to data ownership, data sharing, and knowledge creation. To begin to address this oversight, the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (Citation2019) has developed the CARE (collective benefit, authority, responsibility, ethics) principles to re-center people in data governance, shifting focus to Indigenous-led data management and research. These developments come in the wake of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Citation2007), a supranational legal document that defines the rights of Indigenous peoples to self-determination as well as individual and collective rights in the ownership of their cultural heritage, including archaeological cultural heritage.

Ownership of the past and the digitization of archaeology are underlying themes that are shaping how archaeologists practice their craft. A gap exists between scholars who focus on digitization, including data structures and technical implementation data principles, and those who examine the social implications of accumulating and classifying large volumes of data and efforts to standardize archaeology. Social scholars of science and archaeologists have examined the colonial roots of data practices particularly in “settler” contexts such as Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand (McBryde Citation1986; Watkins Citation2000; McNiven and Russell Citation2005; Trigger Citation2006). Until very recently, non-Indigenous scholars often considered Indigenous peoples objects of study, and archaeological practices typically prevented descendant communities from ownership of their past, and from knowledge making about their ancestors (Atalay Citation2006; Pokotylo and Mason Citation2010). Often financed by museums and other government agencies, archaeologists recovered and documented material culture through excavations and typically shared archaeological data on a case-by-case basis. This situation resulted in some archaeologists withholding field records and recovered artifacts indefinitely. The archaeologist, therefore, assumed ownership and possession of recovered material culture, and by extension, authority on a past society and geographic area.

Accumulation and compilation of large amounts of archaeological data, their classification and interpretation continue in national contexts. Growing numbers of Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars now challenge practices that disadvantage Indigenous peoples and distance them from management of their cultural heritage (L. T. Smith Citation1999; Atalay Citation2010; Nicholas et al. Citation2010; Andreson and Christen Citation2013). This situation underscores the rights of Indigenous peoples and the interests of descendant communities in creating knowledge about their ancestors. These developments, however, have not fully engaged with scholarship on the digitization of archaeology, a situation that obscures power and knowledge making in a rapidly changing technological environment.

Digitization of archaeology and the increasing importance of the Web, particularly communication tools such as Web 2.0 technologies, are facilitating collaboration, exchange and sharing of digital archaeological data between scholars and policy makers, government agencies, and private companies, as well as more broadly with the general public (Kansa Citation2011). Some archaeologists have posed “grand challenges” that firmly situate digital archaeological data and “cross-disciplinary collaboration” at the core of scientific research, and by extension, the future of the discipline (Kintigh et al. Citation2014). They seek to integrate archaeological data through and within “cyberinfrastructures” (Snow et al. Citation2006). Greater availability of high resolution remotely-sensed terrestrial imagery and Light Detection and Ranging (lidar) combined with the reusability of existing archaeological data has renewed urgent concerns over privacy of the location of archaeological sites, and by extension, the potential for looting and unregulated destruction of these sites (Bampton and Mosher Citation2001; Sitara and Vouligea Citation2014). These developments are highlighting concerns over data governance in archaeology, including the ownership of data and control over what happens with data, issues of data quality, authority and accessibility, which in turn, present challenges and opportunities for archaeologists in the geospatial web (Harris Citation2012).

In this context, critical scholarship highlights power relations in the making of digital spatial data (Schuurman Citation2005), the conceptualization of maps as objective and authoritative (Harley Citation1989; McCann Citation2008), volunteered geographic information (Haklay, Singleton, and Parker Citation2008), as well as the structures, institutions, and software technologies that privilege political interests of particular social groups (Obermeyer Citation1995; Gajjala and Bierzescu Citation2011). This shift in focus amplifies data governance issues such as ownership, control, accessibility, and spatial data quality issues, particularly in the accumulation of large amounts of volunteered geographic information or crowd-sourced data (Goodchild Citation2009; Onsrud Citation2010), and legal and policy issues concerning spatial databases (Rhind Citation1996). These developments have not yet gained much traction within the archaeological community.

Recent efforts in archaeological heritage management, especially when it comes to digital spatial databases, focus on the creation of “sustainable infrastructure” to enable effective compilation, maintenance, and distribution of archaeological data (McKeague et al. Citation2019). National-level initiatives such as the United Kingdom-based “Archaeology Data Service” (ADS) (Richards Citation2002), the United States-based “the Digital Archaeological Record” (tDAR) (McManamon, Kintigh, and Brin Citation2010), the “Digital Index of North American Archaeology” (DINAA) (Wells et al. Citation2014), and the Canadian Archeological Inventory Survey Tool (CAIST) (Dent Citation2019) are highlighting issues in the management and preservation of digital archaeological data. This scholarship draws attention to interoperability and data standards such as metadata i.e., information that enable users to find relevant data (Richards Citation2009) and to open licensing (Wright and Richards Citation2018) that can facilitate integration across diverse, heterogeneous data sources. Greater attention is now given to Open Science and documentation of data processing (Marwick et al. Citation2017) as well as quality issues in archaeological databases throughout the research process, the impact of uncertainty on interpretation and prediction (Van Leusen, Millard, and Ducke Citation2009), and the potential for data re-use. While informative, these efforts typically do not make explicit the legal and policy environment in which archaeologists create, use, make “open” or re-use spatial databases and their contents.

Multi-national research infrastructure networks such as the European Advanced Research Infrastructure for Archaeological Dataset Networking in Europe (ARIADNE) (Niccolucci and Richards Citation2013) potentially raise uncertainties regarding rights in spatial media because legal rights can differ between countries as well as in terms of the scope and subsistence of rights in particular works or compilations of data (Scassa Citation2017). However, as Scassa (Citation2017, 159) notes, under the European Union Database Directive (Citation1996), a compilation of data has “database rights” that entitle the owner considerable protection to prevent extraction and/or re-use of the whole database or part of its contents. Under this legal model, a database is “a collection of independent works, data or other materials arranged in a systematic or methodical way and individually accessible by electronic or other means.” These legal rights certainly do not apply in countries that are not subject to European Union laws and policies, suggesting that archaeologists must examine data governance issues in spatial databases within the social and political context in which a database and its content is created, maintained, and used. Better understanding of the legal and policy issues associated with data can clarify who can do what with compiled geospatial data.

In Canada, the First Nations Information Governance Centre (Citation2007, Citation2014) has developed the OCAP® principles on how First Nations information is to be collected, protected, used, and shared. The OCAP® principles can enable Nation-to-Nation conversation and partnerships on equal terms. These efforts signal a shift in the way that research is carried out with First Nations in terms of who owns, controls and has access to information, including cultural knowledge collected in First Nations communities. The principles acknowledge the history of colonial relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, as well as colonial practices and policies that brought harm to, and continue to disadvantage, Indigenous communities. In this sense, OCAP® principles lay the groundwork for First Nations to maintain individual and community ownership of information and to protect information from misuse, where Crown law has failed Indigenous peoples in Canada. Indigenous people can now drive research projects from their inception to completion, manage information that is collected and processed, and make decisions on who can access which data. The OCAP® principles are applicable in research and in the management of archaeological cultural heritage.

In this paper, we consider data governance issues in archaeological spatial databases from the perspective of the rights of Indigenous peoples. We examine the practice of Canadian archaeology in the wake of federal commitments to the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (Citation2015) (henceforth, TRC), efforts that acknowledge the history of colonialism and document the impact of colonial practices that harmed Indigenous peoples in Canada. In the Canadian context, Indigenous refers to peoples and communities that are First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. First Nations typically refers to Indigenous peoples in Canada recognized under the Indian Act (Citation1985) and the federal government recognizes 634 First Nations. Within this framework, we shed light on challenges and opportunities for archaeologists to engage more fully with legal and policy issues associated with archaeological spatial databases in a rapidly changing technological environment. We begin with a brief overview of the making of an archaeological spatial database, including issues of access, control, and ownership of archaeological data, followed by a discussion on database management and data practices in Canadian archaeology. We then discuss Indigenous data governance of archaeological spatial databases in the age of big data. While our examination focuses on the Canadian context, the themes we discuss are applicable in archaeology more broadly.

Making of an Archaeological Spatial Database

Digital spatial databases are at the interface of geographic visualization and the storage and management of archaeological site location information (i.e., coordinate data) (Gupta and Devillers Citation2017). The availability of archaeological spatial databases make possible data-intensive methods and “big” data approaches in archaeology. However, these efforts sometimes underestimate the influence of legal and policy issues on the quality, authority, and ownership of archaeological spatial databases, which in turn obscures power-, space- and knowledge-making in archaeology.

Archaeological data are broadly conceptualized as movable artifacts and immovable features and archaeological site information and, collectively, they are central to understanding past societies. Location information on and associated descriptions of archaeological sites are typically compiled and organized into an archaeological spatial database. In “settler” contexts such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, paternalistic colonial-era legislation has obscured the rights of Indigenous people and heritage laws have typically denied Indigenous rights to their cultural heritage, privileging state ownership of archaeology (Pokotylo and Mason Citation2010). In recent years, cultural heritage collected through excavations ranging from human remains to artifacts and archaeological sites has come under intellectual property law, a situation that reflects power and authority in archaeology (Nicholas et al. Citation2010).

From the 1960s onwards, rapid economic change coincided with the development of commercial archaeology and growing concerns over the destruction of cultural heritage. Throughout the 1970s, the increasing availability of personal computing technologies facilitated the use of databases in archaeology (Scollar Citation1999). In subsequent decades, the implementation of specialized GIS software and techniques within government, academia, and private businesses encouraged archaeologists to employ spatial databases to manage, visualize, and analyze archaeological data (Allen, Green, and Zubrow Citation1990; Tamplin Citation1999).

Archaeological spatial databases are central in the management and processing of digital archaeological data as part of archaeological impact assessment processes, as well as to facilitate permit regulation and granting. These compilations of data are typically managed by sub-national (state/province, territory) governmental agencies and archaeological spatial databases are presented as authoritative instruments in the management of cultural heritage. While archaeologists and heritage professionals are typically aware that these instruments are missing information and require regular updating and maintenance, general members of the public do not have this specialist knowledge. A layperson generally accepts the authority and comprehensiveness of these government-managed tools. This has serious implications in cases where members of the public make decisions based on incomplete information provided through Web-based platforms, an issue we will return to in a later section.

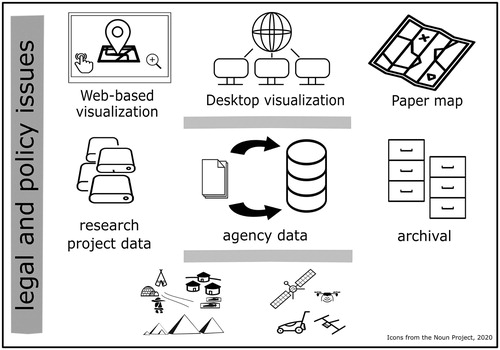

Data from a range of sources can populate an archaeological spatial database. For example, paper site reports could be digitized and compiled into a digital collection, which can be combined with another set of data that are “born-digital” (). In Canada, commercial archaeologists working for private firms now collect the bulk of archaeological data, typically as part of archaeological and environmental impact assessments prior to large-scale construction projects. By regulation, commercial firms submit their prepared reports to a government agency, which in turn, compiles relevant site information into an inventory. These government compilations of data are the basis for heritage planning and policy recommendation. In this sense, the governance of the archaeological spatial database itself is a symbol of the authority of archaeology (L. Smith Citation2000, 311).

Figure 1. Compilation of data and their management in archaeological spatial databases is associated with legal and policy issues. Researchers, the commercial sector, and government agencies all collect archaeological data. Government agencies that compile data into archaeological spatial databases assume ownership of these instruments. Laypersons often believe that information from agencies are authoritative, complete and of high quality, and an unknowingly base decisions on these instruments. Greater attention to the rights of Indigenous peoples, and legal and policy issues associated with archaeological spatial databases is necessary for archaeology in the 21st century.

However, the legal relationship between the archaeologist who has collected field data and the government compiler of data is uncertain. Is the archaeologist who collected data the author and original copyright holder of those data? What is the legal status of data once they are in the hands of the government compiler? Who has the authority to process, transform, and distribute these data? These questions relate directly to data quality issues not discussed here but that require greater scholarly attention in archaeology. The following sub-section focuses on access and ownership of archaeological data and offers insights into how archaeologists might begin to address these issues.

Ownership, Access, and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Government data in Canada is subject to Crown copyright, which means that the federal government has “control over works prepared or published under the direction or control of the crown unless there exists an agreement to the contrary” (Power Citation2014, 2). Under Crown copyright, the government maintains control over its works (including geospatial data), and may choose to make the data available freely and without restrictions on its use. Alternatively, the government may license data with restrictions or conditions on certain kinds of use (Judge and Scassa Citation2010, 367). This model is in contrast to the United States, where the federal government releases its works into public domain and they are free for use by anyone. Individual states in the US can and do assert copyright on works that are created within their jurisdiction. Differences in legal understandings of ownership and control of government data between jurisdictions therefore have significant implications for archaeologists who collaborate across legal boundaries and for Indigenous communities whose cultural heritage spans sub-national and national jurisdictions. The legal and policy situation becomes more complex and uncertain when digital compilations of geospatial data are considered.

Copyright principles distinguish between what may be protected and what may not be protected. In the Canadian context, the dichotomy is between original expression (protected) and fact (not protected) (Scassa Citation2017). When applied to traditional paper maps, this fact-expression distinction is clear. Graphic representations are original expressions and thus are protected and “owned” under copyright law. Geographical facts are not protected and public policy in copyright law prevents “anyone from obtaining a monopoly over the ability to represent those facts in a map” (Scassa Citation2017, 159). However, even though facts are not under copyright, there might be copyright in a compilation of facts when its selection or arrangement presents “originality.” The threshold for “originality” in selection or arrangement of a compilation varies between Europe, Canada, and the United States. In the Canadian interpretation, originality requires “judgement and skill,” whereas in the American interpretation, the standard is a “spark or modicum of creativity” (Saunders, Scassa, and Lauriault Citation2012, 281). In Europe, a compilation has “database rights” (e.g., sui generis).

With digital spatial media, the distinction between fact and expression is more challenging because of the ease with which digital media are “shared, manipulated, combined and represented” (Scassa Citation2017, 162). This situation is further highlighting the concept of “data” and complexities in distinguishing them from facts (Scassa Citation2018, 7). For example, visual digital representations backed by databases and software that draw upon data from several sources and intellectual property owners are complicating traditional conceptualizations of expression, and by extension, what is owned and what is not. A user who creates a map on a third-party base layer service (e.g., Google Maps), for example, does not have rights to that underlying base layer (Saunders, Scassa, and Lauriault Citation2012). This scenario reflects legal complexities and uncertainties in ownership of spatial media transformed through digital workflows and practice.

Crown copyright over works are typically asserted with the motivation to better control the accuracy, integrity, and quality of information that might be used by general members of the public (Judge and Scassa Citation2010). GeoConnections, a best practices guide for licensing for government geographic data developed by Natural Resources Canada, however, asks that a licensee must acknowledge the government as a source of data, and accept a disclaimer for “any responsibility for flawed or faulty data” (Judge and Scassa Citation2010, 367). This situation becomes particularly challenging for the creation of “downstream” (derived) value-added products and their quality, and any further compilations of government data for innovative purposes. These efforts highlight uncertainties in copyright law associated with government geospatial data. While informative, they offer few insights into how Indigenous people might gain control over their information.

Developed in 1998, the OCAP® principles directly address the rights of First Nations to own, control, access, and possess data collected in their communities. The principles reflect the deep interest and commitment of First Nations in using information to benefit their communities, and they underscore First Nations’ rights to take possession of their own data. Given the colonial history of Crown relations with First Nations, it is not surprising that Canadian federal institutions hold significant amounts of information pertaining to First Nations (FNIGC Citation2014, 27). Regulation of the use and disclosure of First Nations information is through Canadian law and this can pose legal barriers to the implementation of OCAP® principles. For example, under the Access to Information Act, Canadian federal institutions can disclose information that have been collected by other government organizations, and/or information that First Nations have provided the Canadian federal government (FNIGC Citation2014, 29).

Anonymized digitized records or those stripped of personal identifiers can be released to any requesting parties. Moreover, when they are no longer in use, Library and Archives curates government records from different departments and institutions. Under the Library and Archives of Canada Act, these records, including personal identifying information (20 years after death of person), can be released to the public, and this can have serious implications for First Nations communities (FNIGC Citation2014, 30). Thus, where Canadian federal institutions have possession of First Nations’ information, First Nations have limited say on the use, management, and disclosure of that information.

Similar issues over ownership, control, and access exist at the sub-national level, where provincial and territorial agencies accumulate, manage, and store information on First Nations’ health and education records. While the federal Access to Information Act does not apply to information held at a sub-national level, individuals can request the release of information under province- or territory-legislated freedom of information laws. Time-limited license agreements between the government institution and the requesting party typically regulate the sharing of data. The requesting party must destroy the records upon expiration of the license agreement. As with information held by the federal government, First Nations communities have minimal voice in the use of the information, and in the disclosure of such information. Therefore, there is considerable scope for engagement with Canadian federal and sub-national institutions in the implementation of the OCAP® principles when it comes to archaeology and digital heritage.

The Canadian Archaeological Association (henceforth, CAA), whose members include professional, avocational and student archaeologists, academics, and individuals from the general public, has endorsed and adopted both the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the TRC Calls to Action and has sought to implement these principles in archaeology. Specifically, the professional organization’s members agree to “acknowledge that Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop their archaeological heritage” (CAA Citation2019). They further agree to “invite Indigenous people to participate on every archaeological project and to make every reasonable effort to hire and train Indigenous people to conduct not only archaeological fieldwork, but also labwork analysis and interpretation of archaeological data and writing to reports” (CAA Citation2019). This shift in perspective on the rights of Indigenous peoples to their heritage creates opportunities for greater and more meaningful engagement on matters of archaeology and cultural heritage management. While the CAA’s statement does not specifically discuss digital heritage, it draws attention to the need to work closely with Indigenous people on all aspects of archaeological study.

In their recent examination of the dissemination of open geospatial data under Canada’s Open Government license (OGL-C) through OCAP® principles, Hackett and Olson (Citation2019, 2) note the need for careful consideration when it comes to integration of First Nations data into open government initiatives. Hackett and Olson (Citation2019, 3) explain that the OGL-C removes restrictions on the reuse of published government information (data, information, websites and publications), allowing users to “copy, modify, publish, translate, adapt, distribute or otherwise use the information in any medium, mode or format for any lawful purpose” including the manufacture and distribution of derivative products. Users in turn acknowledge the source of the information through an attribution statement required by the Information Provider(s) and where possible provide a link to the source. Hackett and Olson (Citation2019, 12) remark that when a First Nation releases its data under the OGL-C license, the community will “lose control over how their data is used, analyzed and stored.” However, they argue that OCAP® principles can support First Nations in creating “different levels of access” that maintain cultural protocols and ethics, which in turn can enable First Nations in participating on their own terms in open geospatial data initiatives.

Most importantly, the authors suggest that two key factors impact the participation of First Nations in open government data initiatives; namely, the “digital divide” in terms of a “lack of digital infrastructure,” and a “lack of geospatial capacity” (Citation2019, 14–15). Many First Nations are in remote locations where broadband service is limited and internet connectivity is sporadic (Citation2019, 15), a situation that limits participation online and constrains the kinds of geospatial data they can download or upload. Furthermore, Hackett and Olson (Citation2019, 15) observe that First Nations communities do not necessarily have funding for hardware and software and often do not have “support for geospatial capacity development,” a situation that presents a barrier for First Nations in fully engaging with governance of their own geospatial data. These barriers, the authors suggest, can be overcome. They see Canadian federal commitments to reconciliation and open government as a way to “support Indigenous data sovereignty” (Hackett and Olson Citation2019, 25). While fruitful, these efforts overlook existing data practices and underestimate the challenges of working with sub-national agencies that hold and control access to Indigenous information. Provincial and territorial agencies often have varied resources, data management expectations, and aims. In the next section, we shed light on database management and data practices in Canadian archaeology.

Database Management and Data Practices in Canadian Archaeology

Archaeological database management and data practices are best understood within their social and political context. Provinces and territories administer Canadian heritage legislation, including archaeology (Warrick Citation2017), and there is no federal level legislation even though Canada is a signatory to United Nations conventions on heritage preservation (Burley Citation1994). Most, but not all, of collecting archaeological data takes place as part of impact assessment for large-scale construction projects and resource extraction (Williamson Citation2018), activities that are often sponsored by Canadian federal, provincial, and territorial governments. Management of archaeological information, therefore, has developed in the context of provincial and territorial governance and this factor continues to influence how archaeologists prepare data for reporting purposes and consultation (Dent Citation2012). Moreover, sub-national data governance impacts patterns of access to archaeological data repositories (databases and artifact collections) and how they are utilized, an issue we will discuss in greater detail later. Each province and territory maintains an archaeological site inventory but each is employed in different ways and toward different aims.

Recent findings and “Calls to Action” by the TRC (2015) explicitly recommend compliance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples when it comes to impact from construction on Indigenous lands and territories, and on Indigenous cultural heritage. These developments foresee future transitions to First Nations-led heritage management, including archaeological heritage. Awareness of the rapid and wide-scale destruction of Indigenous cultural heritage and landscapes at the hands of large-scale land development has spurred scholarly interest in implementing these conventions. These efforts range from re-centering Indigenous-led knowledge-making about their ancestors (Nicholas Citation2014), the protection of Indigenous burial grounds (IPinCH Citation2019), the promotion of intellectual interests in archaeology more broadly (Colwell-Chanthaphonh Citation2009), to the return of material culture and human remains held in publically-funded institutions to descendent communities (Nash and Colwell-Chanthaphonh Citation2010, 99). While fruitful, this scholarship overlooks the impact of digitization, obscuring archaeological spatial databases as instruments of ownership in archaeology. In this section, we focus on the management of archaeological spatial databases and data practices as a reflection of state-ownership of archaeology.

Since the late 1970s, the commercial sector, i.e., private businesses in cultural resource management, has increasingly carried out the majority of archaeological recovery and now employs the bulk of archaeologists, including recent graduates from Canadian universities (Williamson Citation2018). This situation means that different archaeologists under employment in a range of private companies regularly document thousands of archaeological sites, a situation that affects the quality of those data, the subsequent decision-making, and the potential re-use of archaeological data. Private firms typically submit documentation on archaeological sites, such as site inventory forms and unpublished reports to provincial and territorial agencies, which in turn invest in some database management system to store archaeological site records and regulate permit granting.

Archaeological database management strategies vary in scope, coverage, tools, and technologies, purpose and restrictions to access. Canadian archaeologists in academia typically share research data on a case-by-case basis and often manage digital archaeological data on a project basis. Project-based archaeological data are likely managed on a combination of personal computers, portable external data storage devices and, where available, allocated data storage in the scholar’s institution. Archaeologists are increasingly interested in sharing research documentation and workflows (Marwick Citation2018) as well as research data on Web-platforms such as GitHub (Strupler and Wilkinson Citation2017), efforts that are sustained with dedicated institutional resources.

Limited information exists on how individual cultural resource management firms manage archaeological data and it is rare for any one firm to share its database on the Web. Once archaeological site data—along with aerial photographs, geophysical readings, and topographic surveys—are collected, regardless of whether by researchers or by commercial archaeologists, an archaeologist might prepare derived data products such as digital elevation models and files that store the location, shape and attributes of archaeological features. Most commonly, data analysts and data managers take charge of digital archaeological data for processing and report preparation. Data are processed and analysed within a computational environment, and the results are synthesized into a document that receives some form of peer review either as a technical report or as a scholarly publication (Linden and Webley Citation2012). At some point in their life, digital archaeological data are in the hands of experts who do not have direct knowledge of their acquisition, nor do these experts have access to the original collectors and their “contextual knowledge.” These archaeological data are then typically submitted to government agencies in compliance with environmental and heritage regulations.

In this context, provincial and territorial agencies maintain authoritative archaeological spatial databases. Government agencies employ a range of strategies to enable compilation, processing, and sharing of digital archaeological databases. In New Brunswick for example, the province manages the Archaeological Site Spatial Database (henceforth, ASSD), a GIS-based instrument comprised of records of archaeological sites that archaeologists have identified since the 1960s. Archaeological records in the ASSD come from different sources. Some records were originally in analog format and subsequently digitized, and compiled into a database management system. These digital records are combined with recently collected archaeological site data and together they are integrated into the ASSD. The spatial database is not available on the Web, and access to the database and its contents is by request only. Moreover, Archaeological Services, the provincial agency that manages these instruments and regulates archaeological permits, has developed predictive models as decision-support tools based on its spatial database. Archaeological Service has integrated predictive models into its archaeological planning and permitting process, and it is now mandatory to purchase these tools to carry out archaeological investigation in New Brunswick.

The Provincial Archaeology Office in Newfoundland and Labrador is responsible for a central repository of all archaeological records in that province. A data manager organizes and processes information from archaeological site record forms. These data are compiled in a relational database management system that is integrated with GIS software, a situation that is typical of government offices where several members of staff have access to archaeological records, but only one or two members have expertise using specialized geospatial software. When the Office receives a request for data, the data manager retrieves relevant records for sharing. Most often, academic archaeologists, students, and consulting archaeologists submit requests for archaeological data. The Office has memorandums of understanding with Indigenous governments to share relevant site data. The archaeological spatial database is also shared with other provincial agencies. When shared, only GIS files come with associated metadata, and few archaeologists expect quality information accompanying requested archaeological data (S. Hull, pers. comm. 2019).

The Archaeology Branch in British Columbia maintains the Provincial Archaeological Site Inventory Database and oversees the distribution of archaeological site records through controlled access on its online platform, Remote Access to Archaeological Data Application (henceforth, RAAD). Archaeological site data are available with restricted access to archaeological researchers, First Nation governments, companies engaged in “land altering development and resource extraction”, land title conveyance professionals, local, provincial and federal governments, private property owners and professional archaeologists (Ministry of Forest, Lands and Natural Resource Operations Citation2019a). In addition to archaeological site data, authorized groups can request permit reports, archaeological overview assessments, and spatial data layers created by the Branch to facilitate “archaeological resource management” (Ministry of Forest, Lands and Natural Resource Operations Citation2012).

Similarly, staff at the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport manages the Ontario Archaeological Sites Database, and with PastPort, its Web-based interface, users are able to retrieve archaeological site records, as well as information on permits and reports. Designed for licensed archaeologists to submit, view, and track requests, the portal facilitates access to archaeological reports, as well as to renew licences. Like RAAD, Ontario’s platform does not allow downloading the database or all of its contents, a situation that potentially constrains addressing the large-scale geographic questions that some archaeologists are interested in (McCoy Citation2017). Most critically, province- and territory-managed spatial databases, while fruitful, offer limited information on the quality of data that they compile and distribute.

When an archaeologist requests access to a provincial or territorial spatial database, they are required to submit a signed license agreement. Licensing agreements vary between jurisdictions; however, there are similarities in such agreements. The Government of the Northwest Territories, for example, explicitly states in its license agreement that the government agency is the “owner of the property rights in a digital spatial database known as the ‘NWT Archaeological Sites Data Base,’” and that its ownership is protected under the Copyright Act of Canada (Government of the Northwest Territories Citation2019, 3). Furthermore, an archaeologist who acquires archaeological data must have written consent to “display, duplicate or reproduce” the data in any form. In situations where displaying sensitive location information is critical to the licensee, staff will work with licensees to develop appropriate visualization techniques that obscure precise locations (J. Buysee, pers. comm. 2019). The subset of data provided to a licensee is free of charge, and the agency offers “no guarantees, representations or warranties” on the database or a subset, including on its “effectiveness, completeness, accuracy, or fitness for any particular purpose” (Government of the Northwest Territories Citation2019, 5).

In the case of RAAD, an authorized user can retrieve GIS files with information on specific archaeological sites, including their locations and approximate boundaries. Detailed information on sites is also available in spreadsheet format as Comma Separated Value files, alongside related documents such as site maps, drawings, photographs, and artifact catalogues. The data sharing agreement suggests the currency and completeness that RAAD offers. The database is updated on a weekly basis and comprises only archaeological sites that have been “formally recorded and submitted to the Archaeology Branch” (Ministry of Forest, Lands and Natural Resource Operations Citation2019b). Up until early 2019, a commercial archaeologist under permit, archaeological researchers or members of the public could submit site information to RAAD. Better understanding of the collection of data and their verification is needed because RAAD is an authoritative instrument in heritage management and in archaeological impact assessment processes, as well as being available to the general public. In the next section, we discuss these issues in terms of real world implications and suggest that engagement with Indigenous data governance can begin to address some of these concerns. We begin with a case in the province of British Columbia.

Indigenous Data Governance in Archaeology

Quality of data requires completeness, and completeness in the global legal environment requires that you know the legal status of the data that you draw from others and have strong confidence that you have legal authority to use the data in your specific context.

(H. J. Onsrud Citation2010, 189)

The province keeps an inventory of First Nations graves and spiritual sites in RAAD as described in the previous section. There are more than 54,000 documented archaeological sites in the province, but this information is not shown on land title documents. This situation means that when a private owner buys an undeveloped lot, they may not be aware that they are purchasing an archaeological site until they start to develop the property. In this case, the mounds were unrecorded and therefore they were not in the archaeological spatial database even though this authoritative instrument is central to the province’s archaeological impact assessment process. This highlights the power that the provincial agency wields through its archaeological spatial database, an authority that underscores the role of the agency in the governance of archaeological cultural heritage.

Moreover, if the location and extent of the site were in the database, a buyer would not necessarily know because the two provincial agencies that are entrusted with these data, the Land Title and Survey Authority and the Archaeology Branch, do not share information with one another. It is up to the buyer to check with the Archaeology Branch or to pay a commercial archaeology firm to learn the status of an undeveloped lot. The Suttons’ situation therefore raises several issues, including compensation for owners when a lot is designated a heritage place and ongoing land claims between federal governments and First Nations. Perhaps most fundamentally, the relationship between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians bears the greatest impact from this difficult situation. What happens when a publically funded authoritative instrument fails to address public needs? How can Indigenous communities gain ownership of their heritage?

Indigenous people have the right to own, control, access, and possess information on their archaeological heritage. Canadian federal and sub-national agencies assume stewardship of Indigenous heritage, including archaeological heritage. At present, most First Nations in Canada have limited access to information on the locations and descriptions of archaeological sites. Sub-national (provincial and territorial) agencies typically compile these data and manage them in archaeological spatial databases. Sub-national agencies assume property rights to these compilations, regulating access to them and their contents, and define how data are used, who can use them, and how long they are used. Agencies therefore assume ownership of archaeological spatial databases and the right to ‘make open’ and/or distribute the database and its contents.

Crown copyright law is typically asserted to better control the accuracy, integrity, and quality of information, and especially so when information has the potential to reach the public. Yet at the same time, to gain access to such compilations, an interested party must enter a contractual agreement with the agency and must agree to a disclaimer on flaws and omissions in government information. For example, what would happen if the Suttons had checked the province’s authoritative database and had found nothing to suggest there was an archaeological site on the property before they purchased it? Could they have known that archaeology was unrecorded at the property because of limited or no previous survey in that area? There is tension between perceived comprehensiveness or “good quality” of information that comes from a government agency and the actual scope and limitations of information that a layperson has received. However, the general public does not necessarily understand this tension.

Government data are a key source of information for archaeologists. These data are potentially useful for examining large-scale geographic patterns and for investigating other data-intensive questions. In this context, archaeologists may welcome Open Government initiatives that seek to make data open and available for re-use. Growing interest amongst Indigenous communities in controlling their information coincides with Canadian government interests in Open Government (Government of Canada Citation2014) initiatives that range from digitization efforts to Open Data, and Open Government licenses for the reuse of government data. These data can include information that a First Nation has provided various Canadian government agencies, and/or information that government agencies have collected through partnerships with First Nations.

In some contexts, First Nations communities that enter into contractual agreements with agencies must consent to share information on archaeology recovered in their territories as a precondition to access provincially held archaeological information (A. Hawkins, pers comm., 2019). Invariably, any information that the First Nation provides the Canadian agency is compiled into the agency’s existing database, which is protected under copyright law. On the one hand, as stewards, Canadian government agencies continue to accumulate and compile archaeological information to enable preservation of cultural heritage for Indigenous communities. Yet, at the same time, these very efforts also prevent First Nations from managing and having possession of their heritage. This situation reflects the asymmetrical power relationship between Canadian governments and First Nations, and highlights practices that continue to distance Indigenous communities from ownership of their heritage.

In a rapidly changing digital environment, these issues are more pressing as greater numbers of people with varying skills, abilities, and interests now have access to greater amounts of geo-referenced archaeological information, and can make decisions based on these data. For example, just as a private citizen who can get information on burial mounds on a property, an oil and gas company can get information on archaeology in an area, and based on this information, the company may plan an ideal location to build a pump station that avoids known archaeological sites. In each case, First Nations communities do not have a say in which information and how much information interested parties receive.

Indigenous data governance in archaeology begins to address some of these concerns. Data governance initiatives like CARE (Global Indigenous Data Alliance Citation2019, 1) seek to recenter Indigenous people’s ability to assert their rights to self-determination and their claims to ownership of data, including those collected by “governments and institutions.” While control of information is central in CARE principles, they do not explicitly call for ownership of Indigenous data. Rather, the principles assert the “authority to control” and to “be active leaders in the stewardship of, and access to Indigenous data” (Global Indigenous Data Alliance Citation2019, 2). On this particular point, CARE differs from OCAP® principles in that the latter emphasize data possession and ownership. The right to own is key to wielding control over data—it is the First Nation’s ability to provide access or to restrict access in part or in full. In taking physical possession of data, the First Nation community also takes the responsibility to manage its information in the short-term and for long-term purposes.

First Nations communities can develop data governance for archaeological heritage based on the OCAP® principles. This situation may alarm archaeologists who want work on Indigenous information, and fear that relevant data will now be out of reach, which in turn can constrain certain types of research questions. Yet there is good evidence that Indigenous-owned data opens possibilities for partnerships and creates intellectual space for new forms of archaeological research and mutual areas of interest in data governance issues.

For example, a key issue that First Nations face in implementing and developing their own strategies for managing archaeology and digital heritage is limited research infrastructures and limited resources and skills to develop and maintain such research infrastructures. While there are no quick solutions, this presents an opportunity for archaeologists to form meaningful partnerships with First Nations toward building capacity in digital methods, tools and technologies. These efforts resonate with Wright and Richards’ (Citation2018) work on developing online research infrastructures with partners in European countries that have different levels of resources and skills.

Moreover, Wright and Richards (Citation2018) remark that research infrastructure development requires early identification of who may hold archaeological data in the long-term, and dissemination strategies for these data. These important themes overlap with the concerns of Indigenous people when it comes to their data. Digital data are fragile and they are not persistent. As the authors suggest (Citation2018, S60), the key to making data sustainable lies in “creating more resilient stakeholder communities,” by which they mean working collaboratively with partners to address issues like data quality and developing good digital practice. This kind of collaborative effort shifts focus to developing research infrastructures appropriate for archaeology that can support different kinds of access, privacy, and use.

Anderson, McElgunn, and Richland (Citation2017) developed Traditional Knowledge (TK) licenses that allow communities to better define the kinds of use that are culturally appropriate for their copyrighted works. TK licenses require that the Indigenous community is already a copyright holder, and with these tools, communities can better control how their information is used. Anderson, McElgunn, and Richland (Citation2017, 188) created TK labels as a way for Indigenous communities to add descriptive text on suggested use of specific works that are out of their reach (e.g., in public domain). The Reciprocal Research Network (RRN), a digital infrastructure to support collaborative museum research, reflects similar efforts to work with Indigenous communities as “co-developers” (Rowley Citation2013). This scholarship broadens the range and scope of data governance of digital heritage through engagement with Indigenous communities.

Areas of mutual interest that archaeologists and agencies share include the practices, strategies, and expectations for handling sensitive location information. Coordination between a range of researchers and agencies can help in identifying best practices and create a foundation for the development of more formal protocols in data security. Greater understanding on these important data governance issues can encourage the archaeological community to engage more fully in keeping information secure. Indigenous communities would be equally interested in participating on equal terms in these forms of digital archaeological research.

Conclusions

Archaeologists are interested in the ownership, access, and quality of archaeological data. However, scholars have given limited attention to legal and policy issues associated with archaeological spatial databases. Archaeological spatial databases are at the interface of data management and data visualization. The availability of archaeological spatial databases enables data-intensive methods and “big” data approaches in archaeology. We examined data governance issues such as the ownership, accessibility, and legal issues associated with archaeological spatial databases from the perspective of Indigenous peoples and their rights to own their heritage.

Archaeological spatial databases have become central in the management and processing of digital archaeological data, and facilitate state-ownership of archaeology in the Canadian context. Sub-national agencies often compile archaeological data and these compilations are authoritative instruments in the management of cultural heritage. We suggest that while specialists have an awareness of the range, scope, and limitations of such instruments, general members of the public typically do not know that the databases are missing information and that they require regular updating and maintenance. This is a potential problem because laypersons accept the authority and presumed completeness of these government-managed tools, and are likely to make decisions based on incomplete information provided through Web-based platforms.

In this context, we discussed data governance issues such as the ownership, access and control of archaeological spatial databases. Through examples, we discussed different strategies in the management of archaeological databases, and showed how different agencies control access to archaeological data under copyright laws. We examined these issues in light of Indigenous rights and interests in managing their own heritage. We suggested that legal issues associated with archaeological spatial databases can complicate Indigenous ownership of these tools and that Crown laws typically fall short in protecting the interests of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Government data in Canada fall under Crown copyright. Differences in legal understandings of ownership and control of government data between jurisdictions have significant implications for archaeologists who collaborate across legal boundaries and for Indigenous communities whose cultural heritage spans across these jurisdictions. The legal and policy situation becomes more complex and uncertain when digital compilations of geospatial data are considered. These complexities have implications for Indigenous communities who may want to control the disclosure of information or those who may want to gain control of their information, including archaeological heritage.

Significant amounts of information about First Nations are held as government data and Crown law regulates the use of these data, which means that they can be disclosed in full without any consultation with First Nations. This situation can result in harm to First Nations communities. Developed by the First Nations Governance Centre, the OCAP® principles seek to address longstanding power asymmetries between First Nations and Canadian governments. The principles lay the groundwork for First Nations to maintain individual and community ownership of information, and to protect this information from misuse. Through the principles, Indigenous people have a greater voice in who owns, controls, and has access to information, particularly cultural knowledge collected in First Nations communities.

Canadian federal and sub-national agencies assume stewardship of Indigenous heritage, and at present, most First Nations in Canada have limited access to information on the locations and descriptions of archaeological sites. Sub-national agencies assume property rights to archaeological spatial databases, regulating access to them and their contents, and define how data are used, who can use them, and how long they are used. These practices distance Indigenous peoples from ownership of their heritage.

Growing interest amongst Indigenous communities in controlling their information coincides with Canadian government interests in Open Government initiatives that range from digitization efforts to Open Data, and Open Government licenses (Government of Canada Citation2014). These data can include information that a First Nation has provided various Canadian government agencies, and/or information that government agencies have collected through partnerships with First Nations. A commitment to OCAP® principles can enable First Nations in asserting their rights to their archaeological heritage and in addressing colonial practices in archaeology.

Archaeologists who want to work with and on Indigenous information may become alarmed that with greater Indigenous data governance, there will be limited access to relevant data. Yet, Indigenous ownership of their data can open possibilities for partnerships and can create intellectual space for new forms of archaeological research and mutual areas of interest in data governance issues. Greater attention to community-driven intellectual efforts can enhance the bonds of trust between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, a situation that can meaningfully address colonial practices in archaeology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Parker Van Valkenburgh and Andrew Dufton for the invitation to the SAA session, and Dr. Mark McCoy for his thoughtful comments. Gupta did this research as a McCain Postdoctoral Fellow in Innovation at the University of New Brunswick. Gupta thanks agency managers, S. McKeane (Nova Scotia), S. LeBlanc and S. Perry (Nunavut), E. Mundy (Prince Edward Island), G. MacKay and J. Buysse (Northwest Territories) and S. Hull (Newfoundland and Labrador) for their knowledge and insights into archaeological data practices. We thank the journal editor and three anonymous reviewers for constructive comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on Contributors

Neha Gupta (Ph.D. 2012, McGill University) is Assistant Professor in Anthropology at The University of British Columbia, Okanagan.

Susan Blair (Ph.D. 2004, University of Toronto) is Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of New Brunswick.

Ramona Nicholas (M.A. 2018, University of New Brunswick) is Kcihcihtuwihut at the Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre, and a Ph.D. student with specialities in archaeology at the University of New Brunswick.

ORCID

Neha Gupta http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7086-9719

References

- Access to Information Act. R.S.C.1985a., c. A-1, s. 13. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/a-1/, Accessed December 2019.

- Allen, K. M. S., S. W. Green, and E. B. W. Zubrow. 1990. Interpreting Space: GIS and Archaeology. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Andreson, J., and K. Christen. 2013. “Chuck a Copyright on It: Dilemmas of Digital Return and the Possibilities for Traditional Knowledge Licenses and Labels.” Museum Anthropology Review 7 (1-2): 105–126.

- Anderson, J., H. McElgunn, and J. Richland. 2017. “Labeling Knowledge: The Semiotics of Immaterial Cultural Property and the Production of new Indigenous Publics.” In Engaging Native American Publics: Linguistic Anthropology in a Collaborative key, edited by P. V. Kroskrity and B. A. Meek, 184–204. New York: Routledge.

- Atalay, S. 2006. “Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice.” American Indian Quarterly 30 (3-4): 280–310.

- Atalay, S. 2010. “Raise Your Head and Be Proud Ojibwekwe.” In Being and Becoming Indigenous Archaeologists, edited by G. P. Nicholas, 45–54. New York: Routledge. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unb/detail.action?docID=677820.

- Bampton, M., and R. Mosher. 2001. “A GIS Driven Regional Database of Archaeological Resources for Research and CRM in Casco Bay, Maine.” BAR INTERNATIONAL SERIES 931: 139–142.

- Burley, D. V. 1994. “A Never Ending Story: Historical Developments in Canadian Archaeology and the Quest for Federal Heritage Legislation.” Journal of Canadian Archaeology 18: 77–98.

- Canadian Archaeological Association (CAA). 2019. “Statement on UNDRIP and TRC Calls to Action.” https://canadianarchaeology.com/caa/about/ethics/statement-undrip-and-trc-calls-action, accessed October 2019.

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C. 2009. “Reconciling American Archaeology & Native America.” Daedalus 138 (2): 94–104.

- Database Directive (EC) 1996/9 of 11 March. 1996. On the Legal Protection of Databases [1996] OJ L77/20 (Database Directive) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A31996L0009, Accessed October 2019.

- Dent, J. 2012. Past Tents: Temporal Themes and Patterns of Provincial Archaeological Governance in British Columbia and Ontario. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 717. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/717.

- Dent, J. 2019. “Conceptual Boxes and Political Borders: Considering Provincial and Territorial Archaeological Site Inventories.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 43 (1): 1–23.

- First Nations Centre. 2007. OCAP: Ownership, Control, Access and Possession. Sanctioned by the First Nations Information Governance Committee, Assembly of First Nations. Ottawa: National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. 2014. Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP™): The Path to First Nations Information Governance. Ottawa: The First Nations Information Governance Centre. May 2014, https://fnigc.ca/ocap, Accessed October 2019.

- Gajjala, R., and A. Bierzescu. 2011. “Digital Imperialism Through Online Social/Financial Networks.” Economic and Political Weekly 46 (13): 95–102.

- Global Indigenous Data Alliance. 2019. “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. The CARE Principles Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group.” https://www.gida-global.org/care, Accessed October 2019.

- Goodchild, M. F. 2009. “NeoGeography and the Nature of Geographic Expertise.” Journal of Location Based Services 3 (2): 82–96.

- Government of Canada. 2014. “Directive on Open Government,” https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=28108, Accessed October 2019.

- Government of the Northwest Territories. 2019. “Access to Request for the NWT Archaeological Sites Data Base.” Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre Archaeology Program. https://www.pwnhc.ca/docs/CPP-PSC-ASDB-BDSA-2017-03.pdf accessed March 2019.

- Gupta, N., and R. Devillers. 2017. “Geographic Visualization in Archaeology.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24 (3): 852–885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-016-9298-7.

- Hackett, J., R. Olson, and the Firelight Group. 2019. Dissemination of Open Geospatial Data under the Open Government License-Canada through OCAP® Principles. Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure Information Product 57e. The Minister of Natural Resources, Canada. https://doi.org/10.4095/314977, accessed November 2019.

- Haklay, M., A. Singleton, and C. Parker. 2008. “WebMapping 2.0: The Neogeography of the Geoweb.” Geography Compass 2: 2011–2039.

- Harley, J. B. 1989. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 26 (2): 1–20.

- Harris, T. 2012. “Interfacing Archaeology and the World of Citizen Sensors: Exploring the Impact of Neogeography and Volunteered Geographic Information on an Authenticated Archaeology.” World Archaeology 44 (4): 580–591. DOI: 10.1080/00438243.2012.736273.

- Heritage Conservation Act. RSBC 1996, c 187. http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96187_01, Accessed October 2019.

- Hunter, G. J., and K. Beard. 1992. “Understanding Error in Spatial Databases.” Australian Surveyor 37 (2): 108–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050326.1992.10438784.

- Indian Act. R.S.C., 1985, c. I-5., https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/ Accessed October 2019.

- IPinCH (Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage: Theory, Practice, Policy, Ethics). 2019. Declaration on the Safeguarding of Indigenous Ancestral Burial Grounds as Sacred Sites and Cultural Landscapes. https://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/resources/declarations/ancestral-burial-grounds/, accessed February 2019.

- Judge, E. F., and T. Scassa. 2010. “Intellectual Property and the Licensing of Canadian Government Geospatial Data: An Examination of GeoConnections’ Recommendations for Best Practices and Template Licences.” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien 54: 366–374. DOI:10.1111/j.1541-0064.2010.00308.x.

- Kansa, E. C. 2011. “Introduction: New Directions For the Digital Past.” In Archaeology 2.0: New Approaches to Communication and Collaboration, edited by E. C. Kansa, S. W. Kansa, and E. Watrall, 1–25. Los Angeles, CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

- Kintigh, K. W., J. H. Altschul, M. C. Beaudry, R. D. Drennan, A. P. Kinzig, T. A. Kohler, W. F. Limp, et al. 2014. “Grand Challenges for Archaeology.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (3): 879–880. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1324000111.

- Library and Archives of Canada Act. SC 2004, c 11, http://canlii.ca/t/52f15 retrieved on 2019-11-18.

- Linden, M. V., L. Webley, et al. 2012. “Introduction: Development-led Archaeology in Northwest Europe: Frameworks, Practices and Outcomes.” In Development-led Archaeology in Northwest Europe Proceedings of a Round Table at the University of Leicester 19th–21st November 2009, edited by L. Webley, M. V. Linden, C. Haselgrove, and R. Bradley, 1–8. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Marwick, B., J. d’Alpoim Guedes, C. M. Barton, L. A. Bates, M. Baxter, A. Bevan, E. A. Bollwerk, et al. 2017. “Open Science in Archaeology.” The SAA Archaeological Record 17 (4): 8–14.

- Marwick, B. 2018. “Using R and Related Tools for Reproducible Research in Archaeology.” In The Practice of Reproducible Research: Case Studies and Lessons from the Data-Intensive Sciences, edited by J. Kitzes, D. Turek, and F. Deniz. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. https://www.practicereproducibleresearch.org/case-studies/benmarwick.html, accessed December 2019.

- McBryde, I. 1986. Who Owns the Past?: Papers from the Annual Symposium of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- McCann, E. J. 2008. “Expertise, Truth, and Urban Policy Mobilities: Global Circuits of Knowledge in the Development of Vancouver, Canada’s ‘Four Pillar’ Drug Strategy.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (4): 885–904. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38456.

- McCoy, M. D. 2017. “Geospatial Big Data and Archaeology: Prospects and Problems Too Great to Ignore.” Journal of Archaeological Science 84: 74–94.

- McCue, D. 2019. “Discovery of Ancient Burial Mounds Traps Landowners in Bureaucratic ‘Bottomless pit of Hell’,” CBC News, March 30, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/national-burial-mounds-property-dispute-chilliwack-bc-1.4979118.

- McKeague, P., R. van‘t Veer, I. Huvila, A. Moreau, P. Verhagen, L. Bernard, A. Cooper, C. Green, and N. van Manen. 2019. “Mapping Our Heritage: Towards a Sustainable Future for Digital Spatial Information and Technologies in European Archaeological Heritage Management.” Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology 2 (1): 89–104. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/jcaa.23.

- McManamon, F., K. Kintigh, and A. Brin. 2010. “Digital Antiquity and the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR): Broadening Access and Ensuring Long-Term Preservation for Digital Archaeological Data.” 23 (2). (tDAR id: 376847) DOI: 10.6067/XCV8KS6QT2.

- McNiven, I. J., and L. Russell. 2005. Appropriated Pasts: Indigenous Peoples and the Colonial Culture of Archaeology. 1st ed. Lanham USA: AltaMira Press.

- Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. 2012. Access to Provincial Archaeological Information. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/natural-resource-use/archaeology/guidance-policy-tools/policy#access, Accessed November 2019.

- Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. 2019a. Request Archaeological Information. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/natural-resource-use/archaeology/data-site-records, Accessed November 2019.

- Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. 2019b. Remote Access to Archaeological Data (RAAD). https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/natural-resource-use/archaeology/data-site-records/raad, Accessed November 2019.

- Nash, S. E., and C. Colwell-Chanthaphonh. 2010. “NAGPRA After two Decades.” Museum Anthropology 33: 99–104. DOI:10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01089.x.

- Niccolucci, F., and J. D. Richards. 2013. “ARIADNE: Advanced Research Infrastructures for Archaeological Dataset Networking in Europe.” International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 7: 70–88. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2013.0082.

- Nicholas, G., C. Bell, R. J. Coombe, J. Welch, B. Noble, J. Anderson, K. Bannister, and J. Watkins. 2010. “Intellectual Property Issues in Heritage Management Part 2: Legal Dimensions, Ethical Considerations, and Collaborative Research Practices.” Journal of Heritage Management 3: 117–147. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2463899.

- Nicholas, Ge. 2014. “Reconciling Inequalities in Archaeological Practice and Heritage Research.” In Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects, edited by S. Atalay, 133–158. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, Inc.

- Obermeyer, N. J. 1995. “The Hidden GIS Technocracy.” Cartography and Geographic Information Systems 22 (1): 78133–15883. DOI: 10.1559/152304095782540609.

- Onsrud, H. J. 2010. “Liability for Spatial Data Quality.” In Spatial Data Quality: From Process to Decisions, edited by R. Devillers and H. Goodchild, 187–196. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Pokotylo, D., and A. R. Mason. 2010. “Archaeological Heritage Resource Protection in Canada.” In Cultural Heritage Management: A Global Perspective, edited by P. M. Messenger and G. P. Smith, 48–69. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- Power, C. 2014. “A Comparative Study of Copyright Licensing Practices for Large-Scale Geospatial Datasets.” Conference Paper for Spatial Knowledge and Information - Canada, 2014. http://rose.geog.mcgill.ca/ski/system/files/fm/2014/power.pdf, Accessed November 2019.

- Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985b., c. P-21, a. 3 “personal information” (m). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/ENG/ACTS/P-21/index.html, Accessed December 2019.

- Rhind, D. W. 1996. “Economic, Legal, and Public Policy Issues Influencing the Creation, Accessibility, and use of GIS Databases.” Transactions in GIS 1: 3–12.

- Richards, J. D. 2002. “Digital Preservation and Access.” European Journal of Archaeology 5 (3): 343–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/146195702761692347.

- Richards, J. D. 2009. “From Anarchy to Good Practice: The Evolution of Standards in Archaeological Computing.” Archeologia e Calcolatori XX: 27–35.

- Rowley, S. 2013. “The Reciprocal Research Network: The Development Process.” Museum Anthropology Review 7 (1-2): 22–43. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/mar/article/view/2172.

- Saunders, A., T. Scassa, and T. P. Lauriault. 2012. “Legal Issues in Maps Built on Third Party Base Layers.” Geomatica W 66: 279–290. https://doi.org/10.5623/cig2012-054.

- Scassa, T. 2017. “Legal Rights and Spatial Media.” In Understanding Spatial Media, edited by R. Kitchin, T. Lauriault, and M. Wilson, 158–166. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526425850.n15.

- Scassa, T. 2018. Data Ownership. CIGI Papers No. 187. Waterloo, ON: Centre for International Governance Innovation. https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/Paper%20no.187_1.pdf.

- Schuurman, N. 2005. “Social Perspectives on Semantic Interoperability: Constraints on Geographical Knowledge From a Data Perspective.” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 40 (4): 47–61.

- Scollar, I. 1999. “25 Years of Computer Applications in Archaeology.” In Archaeology in the Age of the Internet. CAA97. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology. Proceedings of the 25th Anniversary Conference, University of Birmingham, April 1997, edited by L. Dingwall, S. Exon, V. Gaffney, S. Laflin, and M. van Leusen, 5–10. BAR International Series 750. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Sitara, M., and E. Vouligea. 2014. “Open Access to Archeological Data and the Greek Law.” In E-Democracy, Security, Privacy and Trust in a Digital World, edited by A. Sideridis, Z. Kardasiadou, C. Yialouris, and V. Zorkadis, 170–179. e-Democracy 2013. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 441. Cham: Springer.

- Smith, L. 2000. “‘Doing Archaeology’: Cultural Heritage Management and its Role in Identifying the Link between Archaeological Practice and Theory.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 6 (4): 309–316. DOI: 10.1080/13527250020017735.

- Smith, L. T. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Smith, M., T. Cruse, and W. K. Michener. 2011. Data Governance Workshop Final Report. Arlington, VA. https://wiki.creativecommons.org/images/8/86/Data_Governance_Workshop_Final_Report_December_2011.pdf, Accessed December 2019.

- Snow, D. R., M. Gahegan, C. L. Giles, K. G. Hirth, G. R. Milner, P. Mitra, J. Z. Wang, et al. 2006. “Cybertools and Archaeology.” Science 311 (5763): 958–959.

- Strupler, N., and T. C. Wilkinson. 2017. “Reproducibility in the Field: Transparency, Version Control and Collaboration on the Project Panormos Survey.” Open Archaeology 3 (1), https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2017-0019.

- Tamplin, M. J. 1999. “Archaeological Computing in Canada—the First (and Last) 25 Years.” In Archaeology in the Age of the Internet. CAA97. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology. Proceedings of the 25th Anniversary Conference, University of Birmingham, April 1997, edited by L. Dingwall, S. Exon, V. Gaffney, S. Laflin, and M. van Leusen, 53–58. BAR International Series 750. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Trigger, B. G. 2006. A History of Archaeological Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission. 2015. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Retrieved from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-8-2015-eng.pdf.

- United Nations. 2007. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf, Accessed December 2019.

- Van Leusen, M., A. R. Millard, and B. Ducke. 2009. “Dealing with Uncertainties in Archaeological Prediction.” In Archaeological Prediction and Risk Management. Alternatives to Current Practice, edited by H. Kamermans, M. van Leusen, and P. Verhagen, 123–160. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Warrick, G. 2017. “Control of Indigenous Archaeological Heritage in Ontario, Canada.” Archaeologies 13 (1): 88–109. DOI: 10.1007/s11759-017-9310-1.

- Watkins, J. 2000. Indigenous Archaeology: American Indian Values and Scientific Practice. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press.

- Wells, J., E. C. Kansa, S. W. Kansa, S. Yerka, D. Anderson, T. Bissett, K. Myers, and R. DeMuth. 2014. “Web-Based Discovery and Integration of Archaeological Historic Properties Inventory Data: The Digital Index of North American Archaeology (DINAA).” Literary and Linguistic Computing 29 (3): 349–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu028.

- Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, I. J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, et al. 2016. “The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship.” Scientific Data 3: 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18.

- Williamson, R. F. 2018. “Archaeological Heritage Management: The Last and Next Half Century.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 42 (1): 13–19.

- Wright, H., and J. D. Richards. 2018. “Reflections on Collaborative Archaeology and Large-Scale Online Research Infrastructures.” Journal of Field Archaeology 43 (1): S60–S67. DOI: 10.1080/00934690.2018.1511960.