ABSTRACT

The Late Upper Palaeolithic Hamburgian tradition reflects the earliest known human presence in northern Europe after the Last Glacial Maximum. We report here on the open-air site of Jels 3 (Denmark) and its associated stone tool assemblage, which can be unambiguously attributed to this period. Along with only a handful of other sites, Jels 3 represents the northernmost limits of human expansion in Europe at this time. We conduct a technological analysis of the lithic material from Jels 3 and other relevant sites to shed new light on the behavioral processes that likely underwrote this expansion. Given that sites dating to this initial dispersal remain few, are restricted to certain geographic regions, and represent an overall lack of a well-developed settlement hierarchy, we suggest that this dispersal process is most commensurable with the earlier stages of a leap-frogging colonization targeting specific landscape elements and that it was quite possibly very short-lived.

Introduction

By the end of the Last Ice Age, the glacial ice masses of the Northern Hemisphere had retreated significantly and left open landscapes untouched by humans. As part of a wider ecological succession, human groups again began venturing into these regions, including southern Scandinavia, where ice-scoured young moraine landscapes were made accessible for humans then occupying more central regions of the continent (Riede Citation2014a). This particular pioneer dispersal is associated with a Late Upper Palaeolithic Hamburgian culture (ca. 14,700–14,000 cal b.p.). Named after the remarkable, but also not unproblematic, old excavations of Alfred Rust (Citation1937) in the areas just north of Hamburg (Germany), this culture represents an off-shoot of the Late Magdalenian as defined by its lithic (Weber Citation2012) and organic (Wild Citation2020) technology and is—based on projectile point typology—commonly divided into earlier “classic” and later “Havelte” phases.

The exact pattern and process of this pioneer migration remains a matter of contention. Different scenarios for this initial dispersal have been proposed, chiefly the leap-frog and wave-of-advance models (Brinch Petersen Citation2009; Mugaj Citation2018). Wave-of-advance models propose a gradual and spatially homogeneous expansion of human presence over time from a common center of origin. In contrast, leap-frog models suggest an (archaeologically) instantaneous advance where people move relatively far over a short time to establish satellite settlements, leaving swaths of empty space in between (Anthony Citation1990; Anderson and Gillam Citation2000). The archaeological signatures of these divergent dispersals differ: a leap-frog dispersal should yield smaller, ephemeral settlements that are technologically and behaviorally homogenous and clustered in space and time. In contrast, the wave-of-advance model would result in sites that are more heterogeneous in terms of size, composition, and behavior and more evenly distributed both spatially and temporally. While wave-of-advance models have been applied with some success to the re-peopling of northern Europe after the Last Ice Age at the continental scale (Fort, Pujol, and Cavalli-Sforza Citation2004), the archaeological evidence for the Magdalenian in general (Maier Citation2015) and for the Hamburgian in particular—empty spaces, condensed dating sequences, and substantial evidence for long-distance movement—is more readily commensurable with leaping frogs (Brinch Petersen Citation2009; Riede Citation2014b; Pedersen, Maier, and Riede Citation2019).

Crucial to understanding this dispersal process and how Hamburgian groups expanded and mapped onto these peripheral landscapes is the concept of landscape learning (Rockman and Steele Citation2003 and papers therein; Meltzer Citation2004; Rockman Citation2009, Citation2010, Citation2012), which we here include in our model. Landscape learning entails the acquisition of necessary knowledge about the distribution of natural resources in a region where such previous (landscape) knowledge is lacking. Rockman (Citation2003, Citation2009, Citation2012) explains this process as related to different time-dependent learning barriers, which scale in difficulty from 1) locational knowledge which describes more easily obtainable information such as the location of permanent resources (e.g. lithic outcrops) to 2) limitational knowledge, describing harder to learn aspects such as the boundaries of seasonally fluctuating resources (e.g. distributions of plants and animals). The information gathered then needs to be tied together into 3) social knowledge through collective memorization and cognitive mapping of the environment, the patterns of its resources, and related signals using storytelling. The final product of this process is landscape knowledge. Lack of landscape knowledge has been shown to have significant social and economic consequences, even leading to demographic collapse and extinction events, making knowing an environment well crucial to a population’s ability to exploit natural resources and to remain viable (Meltzer Citation2003; Rockman Citation2010). Although difficult to capture, signatures indicating whether pioneering groups learned a landscape or not can arguably be inferred archaeologically (). By the same token, new discoveries in the field, as well as careful analyses of existing assemblages, allow the testing of competing dispersal scenarios.

Table 1. Matrix showing the archaeological signatures (i.e. what is expected to be seen in the archaeological record) of the leap-frog and wave-of-advance models, as well as whether the landscape was successfully learned or not compared with the archaeological record of the Hamburgian occupation of southern Scandinavia (adapted from Kelly and Todd Citation1988; Beaton Citation1991; Housley et al. Citation1997; Davies Citation2001; Hazelwood and Steele Citation2003).

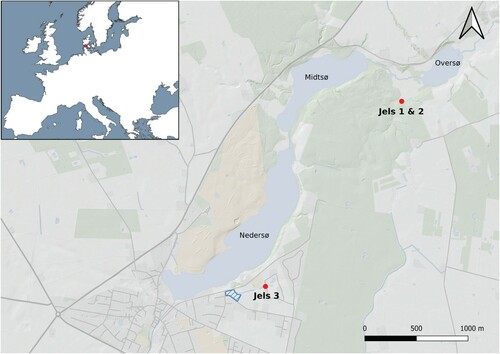

Finds of the Hamburgian are rare, especially in peripheral areas such as present-day southern Scandinavia. We here report on the discovery, excavation, and analysis of the Jels 3 assemblage (HBV 1316 Nedersøparken) and the subsequent archaeological survey of adjacent areas near the Jels lake complex in southern Denmark (Poulsen Citation2013; ). We describe the Jels 3 assemblage and present a detailed analysis of the lithic technology, with specific focus on the morphology of the projectile points and blades, and compare Jels 3 to other sites in the vicinity and further afield in order to assess their role in the pioneer migration process. Our analyses stress the similarities between late Hamburgian sites all along this culture’s northern periphery, which we interpret to indicate close ties between the individual locales and a low level of site differentiation. Together, these elements not only suggest close chronological proximity but also complete households moving camp, rather than task-differentiated mobility within a well-developed settlements system. By placing these observations in a wider comparative framework, Jels 3 provides a rare micro-regional picture of an early entry by humans into the recently deglaciated areas of Late Pleistocene southern Scandinavia. Together with the remaining evidence from the Hamburgian, Jels 3 provides compelling evidence for leap-frogging colonization into ecologically immature and little-known landscapes—a dispersal that may have failed in establishing a continuing exploitation of these landscapes and ultimately resulted in an extirpation or a biological and/or cultural extinction event (Riede Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2009, Citation2014b).

Figure 1. Map of the Jels lake complex. Marked on the map are the two previously excavated sites in the northern part of the lake complex and the newest site in the southern part. The area of the 2011 field survey is marked in blue. Map made using QGIS (QGIS Development Team Citation2019). Map data: naturalearthdata.com and kortforsyningen.dk.

The Hamburgian Culture and the Re-Peopling of Northern Europe

Following the initial discoveries of Hamburgian sites north of Hamburg in the first part of the 20th century a.d., sites and single finds have been found elsewhere in Germany, Poland, the Netherlands, Denmark, possibly Sweden, and perhaps as far as the British Isles to the west (Ballin et al. Citation2018) and Lithuania to the east (Šatavičius Citation2002; but see Ivanovaité and Riede Citation2018 for a critical review of this material). With a material culture that retains clear ancestral Magdalenian elements, the Hamburgian represents the pioneer human re-peopling of northern Europe during the closing phase of the Last Ice Age. The exact routes taken by Hamburgian groups into these higher latitudes are debated, but recent research suggests a dispersal trajectory ultimately from the southwest (Weber Citation2012). The Hamburgian can be dated to the Greenland Interstadial (GI) 1e warming (Grimm and Weber Citation2008; Weber and Grimm Citation2009) and the corresponding Bølling/Meiendorf chronozone (sensu Krüger and Damrath Citation2020), although some dates extend into the subsequent Older Dryas/GI-1d and Allerød/GI-1c. Thereafter, the signature material culture of the Hamburgian disappears from the archaeological record. From rare faunal remains and the seemingly typical location of sites high in the landscape, the subsistence economy of the Hamburgian is thought of as specialized reindeer hunting supplemented with horse and small game (Grønnow Citation1985; Bokelmann Citation1991; Bratlund Citation1994; Weber Citation2013). Limited organic evidence from Poland also indicates that small game, as well as aquatic and plant resources, were utilized (Kabacinski and Sobkowiak-Tabaka Citation2009), although the degree to which this limited evidence can be extrapolated across the culture’s entire geographic and chronological range remains unclear.

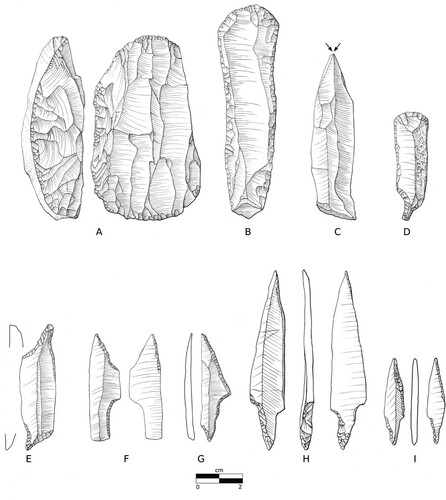

In the context of the Late Upper and Final Palaeolithic of northern Europe, Hamburgian technology and tool forms are highly characteristic. Diagnostic tools for the Hamburgian technocomplex are first and foremost the projectile points: classic asymmetric single-shouldered points belonging to the early Hamburgian and the very particular Havelte type representing the slightly later eponymous Havelte Group. Other diagnostics are the characteristic curve-beaked Zinken, burins (often, but by no means exclusively, dihedral) and end-scrapers, often with lateral retouch. Virtually all formal tools are produced from blades struck from single-faced opposed-platform blade cores. The frequency of double-ended combination tools is notably high (). A division of the Hamburgian into several subdivisions has previously been attempted based on subtle changes in tool forms and frequencies (Tromnau Citation1975), but only two chronological phases or facies are recognized today, namely the earlier and more southeastern classic Hamburgian and the slightly later and more northwestern Havelte phases. With the caveat of generally very poor organic preservation, it appears to be the deliberate shaping of the two projectile point variants, rather than any other aspect of the lithic (Weber Citation2008, Citation2012) or organic (Wild Citation2020) repertoire or subsistence economy, that distinguishes the classic and Havelte phases.

Figure 2. The lithic tool-set of the Hamburgian: A) single faced dual platform blade core, B) blade-end scraper with lateral retouch, C) symmetrical dihedral burin on blade, D) combination tool, E) double Zinken, F–G) Classic Hamburgian shouldered, and H–I) Havelte-phase tanged projectile point. The material stems from the A–G) Meiendorf 2, H) Jels 1, and I) Jels 2 inventories and are redrawn from Rust (Citation1937) and Holm and Rieck (Citation1992), respectively, by Louise Hilmar, Moesgaard Museum.

The first Hamburgian locales in Denmark were documented at the Jels lakes in the southern part of the country in the early 1980s (Holm and Rieck Citation1983, Citation1992). Notably, these were the first true sites of this culture documented north of the German border, despite a long and systematic tradition of archaeological investigations. Additional sites were later discovered at Slotseng, close to Jels (Holm Citation1991), demonstrating the presence of a settlement cluster. Around the same time, the site of Sølbjerg on the eastern Danish island of Lolland (Petersen and Johansen Citation1996), and later on close by Krogsbølle (Riede et al. Citation2019), were discovered and excavated, highlighting the existence of a second settlement cluster at the opposite end of the country. Most recently, the Jels 3 locale presented in this paper was discovered at the southern end of the Jels lakes. These excavated sites are supplemented by a dozen single finds of projectile points, blades, cores, and organic material whose attribution to the Hamburgian is less than certain, as well as the similarly uncertain assemblage Mölleröd from southern Sweden, which likewise contains weak diagnostic elements, such as a possible tanged point of the Havelte variant and Zinken-like implements (Larsson Citation1994). In contrast to Germany, all of the Hamburgian material from Denmark—with the exception of a doubtful single find from Bjerlev Heath (Becker Citation1971)—belongs to the late Havelte group. Furthermore, while Hamburgian sites in Germany are more numerous and more evenly distributed, the sites from Denmark appear to be confined to the two discrete settlement clusters in southern Jutland and on the island of Lolland, respectively. The distance from the Danish settlements to the nearest Hamburgian site to the south (e.g. Ahrenshöft; see Weber et al. Citation2010) is > 100 km, and the distance to the Ahrensburg tunnel valley is > 200 km. By current evidence, the two Danish settlement pockets constitute the northernmost frontier of human expansion at this time.

This evidence has previously been interpreted to indicate an ephemeral exploitation of the landscape (Eriksen Citation1999). The available radiometric data from this period have recently undergone several comprehensive reviews (Grimm and Weber Citation2008; Weber and Grimm Citation2009; Wild et al. Citation2021). While many of the available dates may be individually problematic, the Hamburgian remains one of the best-dated technocomplexes from Late Glacial northern Europe. While the radiometric dating evidence from the fauna-bearing sites in Germany and elsewhere is suggestive of repeated occupation of many sites (Grimm and Weber Citation2008; Weber and Grimm Citation2009), the ephemeral character of the northern sites is underlined by the combined radiocarbon and pollen analysis from Slotseng, which points towards a single deposition event of all faunal remains at the very end of the Bølling/Meiendorf warm period (Mortensen et al. Citation2014). Along with less secure OSL dating evidence from Krogsbølle (Riede et al. Citation2019), this could be suggestive of a very tight dating of the Hamburgian presence this far north towards the very end of the Bølling/Meiendorf. Meta-analyses of the available dating evidence for the Hamburgian highlight that the classic and Havelte phases overlap both temporarily and spatially (Grimm and Weber Citation2008; Weber and Grimm Citation2009; Riede Citation2014b), although the robusticity and extent of this chronological overlap is strongly dependent on the analytical protocol used. Employing more demanding selection criteria and an alternative calibration approach, Pedersen, Maier, and Riede (Citation2019), for instance, suggest multiple expansion pulses separated in time, rather than continuous or contiguous settlement phases.

The Jels 3 Site

Previous investigations

The Hamburgian was recognized for the first time in Denmark in 1981 with the test excavation of the site Jels 1, located by the so-called Upper Lake (Ovsersø) of the Jels lake complex. This locale was discovered through field reconnaissance conducted by an amateur enthusiast. Only 30 m from the Jels 1 site, another Hamburgian locale, Jels 2, was then located, and both were subsequently investigated by Holm and Rieck (Citation1983, Citation1992). Both sites yielded lithic inventories of the Havelte phase of the Hamburgian culture. The two sites differ somewhat in composition: Jels 1 is interpreted as a workshop, being dominated by material stemming from primary reduction and tool manufacture, while the Jels 2 site sports a higher frequency of tools, especially points, and was therefore interpreted as a hunting station. The differences are, however, relatively subtle, and taphonomic or stochastic distortions (cf. Ammerman and Feldman Citation1974) of these artifact frequencies cannot be ruled out. In connection with these investigations, a third site, Slotseng C, was discovered. Slotseng C turned out not only to be rich in lithic material, but faunal material, as well. The Slotseng site is located only 5 km southeast of the Jels lakes in direct connection with these through a river valley passage. The Jels 3 site reported here is, along with the other sites at Jels, located by the lake complex itself.

Topography

The lake complex at Jels is part of a small southwest-oriented tunnel valley ca. 4 km long and 0.5 km wide. The valley is part of the terminal moraine ridge system associated with the westernmost extension of the Scandinavian ice sheet during the Greenland Stadial 2 (Houmark-Nielsen and Kjær Citation2003). The site itself is located on a sandy plateau 47–47.5 masl situated 32 m from a dried-out watercourse and ca. 180 m from the Lower Lake (Nedersø). The extent of the Lower Lake itself is assumed not to have changed considerably since the Final Pleistocene (Holm and Rieck Citation1992, 18).

Discovery and excavation of the site

A preliminary survey was conducted at Jels in September–October 2008 after the area was scheduled for housing development.Footnote1 During this investigation, a series of 2 m wide trenches, running north-south and spaced 15–20 m apart, were machine-stripped. Three minor extensions were made during the preliminary investigation because of features dating to the Iron and Middle Ages. The awareness of previously excavated Hamburgian sites in the area led to the decision to conduct ploughing with the express purpose of detecting such ephemeral flint concentrations (Eriksen Citation2006; Veil Citation2006; Fischer Citation2012), albeit without meaningful results.

Systematic field assessments began in March 2009 by machine-stripping and closely examining the subsoil horizon for features. The removed soil was carefully monitored, leading to the discovery of the first Late Upper Palaeolithic artifacts. These ex situ finds were clearly concentrated towards the western end of the investigated area; given the rarity of Hamburgian sites in the region, the excavation strategy was adapted accordingly. This initially entailed the investigation of a large volume of topsoil aimed at recovering diagnostic artifacts. A large sieving operation was instigated using a custom-modified potato sorting rig. Subsequently, a 1 m2 grid was established in the area from where the lithic artifacts were assumed to stem and was gradually extended as more artifacts were uncovered. The grid system (240 m2) eventually covered an area characterized by fine sand, which contrasted markedly with the surrounding area, which was dominated by clay and entirely devoid of finds. Every square meter was excavated in 50 × 50 cm quadrants and in 10 cm artificial spits until the presence of artifacts ceased. All excavated matrix was wet-sieved using a 1 mm mesh. Due to time constraints and limited complexity and information in the layer sequence, no profiles were drawn.

The very southern part of the excavation area had been covered by a layer of clay when a rainwater basin had been established in the early 1990s. The construction of the same rainwater basin had also removed the westernmost part of the sandy area. The original extent of this area is therefore unknown. A 5–7 m broad zone surrounding the basin was completely disturbed and destroyed in connection with its construction. This disturbed zone is contiguous with the northwestern part of the excavated area, which is further disturbed in the southwestern part by a power cable ditch and other recent activities that section the sandy area squarely off towards the west. Core drilling seeking to reveal the presence of dead-ice holes in the vicinity of Jels 3 was unsuccessful.

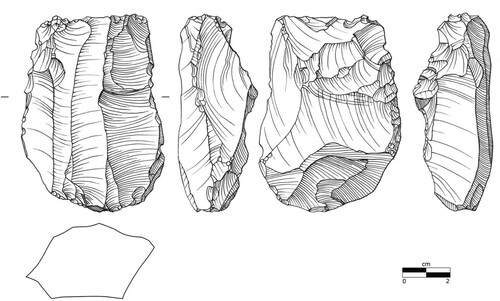

Following the excavation, an area close to it was surface surveyed in early 2011. In only a matter of a few hours, an additional 87 flint artifacts had been retrieved, including cores (n = 2), blade fragments (n = 11), and scrapers (n = 2). The majority (n = 53) of these artifacts are either white- or bluish-patinated. Of these, 26 are heavily white-patinated, a common trait for Late Palaeolithic flints in this region (Petersen Citation2006). Furthermore, eight pieces of burned flint were found. One of the cores is a double-platform blade core showing single-fronted exploitation, a technique most commonly seen in the Hamburgian (). The results of the 2011 survey not only show that more material is present at the Lower Lake, but the proximity of these newly discovered artifacts to the excavated site also suggests that these finds may be in direct connection to the Jels 3 site itself.

The Lithic Inventory

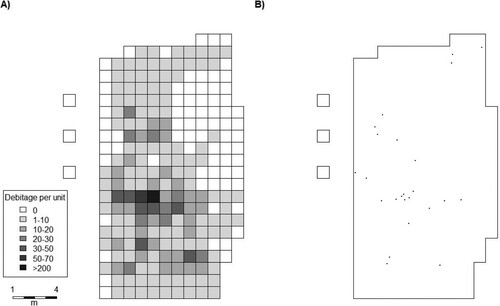

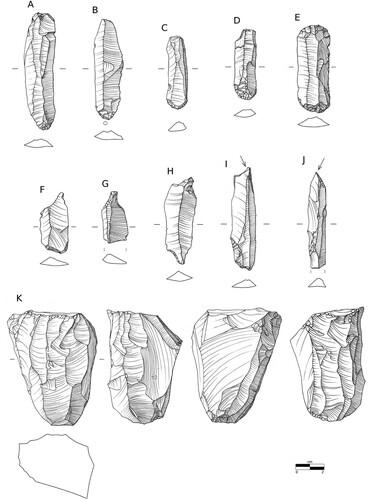

The excavation at Jels 3 has yielded no organic material, but a total of 2846 lithic artifacts of possible Late Pleistocene origin, 2652 of which derive from the area within the grid system. Of these, 1835 were encountered in situ in the sandy subsoil, mostly (n = 1592) in the uppermost 10 cm (). The plough layer yielded only 817 artifacts, indicating that the area has—quite remarkably—not been subject to intense and deep ploughing. The material was distributed into one major and two minor concentrations (). The preserved part of the sandy area covered 198 m2, but its original extent is unknown, due to the disturbance in the western part. Test pits (25 × 25 cm) placed around the rainwater basin and its zone of disturbed subsoil have shown that the sandy area did not extend further beyond the disturbed area, strengthening the association between the dry and well-drained sandy patch and the Palaeolithic site. The tight distribution of the artifacts and débitage indicate only minor post-depositional disturbance by ploughing (cf. Boismier Citation1997). Given the shallow, open-air nature of the site, however, it is likely that cryo- and bioturbation processes have almost certainly moved the artifacts around to some extent. The white to bluish patina and pale surface hue of the lithic material (n = 259) supports, albeit weakly, their Late Pleistocene age. Burnt material was found in small numbers (n = 25) but was evenly spread across the site (see ); no latent signs of a fireplace or other structures were encountered in the field. Primary flint production waste accounts for 96.8% of the material. Of this, 10% consists of blades, blade fragments, and cores. The remaining 90% are flakes. Secondarily modified products (formal tools and retouched material) represent 3.1% of the assemblage, and in spite of the small size of the inventory, it is relatively rich in tools (see ; ).

Figure 4. The Jels 3 grid system. The three stand-alone empty grid squares to the northwest indicate test pits made in order to estimate the extent of damage done during recent disturbances. A) The distribution of artifacts found in situ in the subsoil. B) The distribution of burnt material (each dot represents one piece of burnt flint).

Figure 5. Lithic material from the Jels 3 inventory: A–B) blades, C–E) blade end scrapers, F–H) single and double Zinkens, I–J) burins on blade, and K) single faced blade core. Drawn by Louise Hilmar, Moesgaard Museum.

Table 2. Summary of all artifacts from the excavated grid system and their respective contexts.

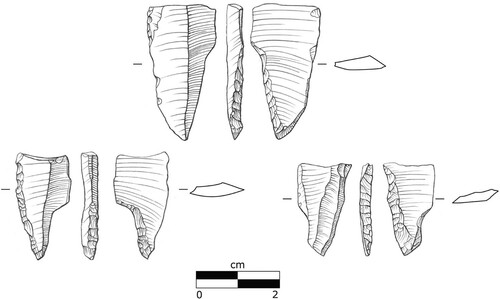

Projectile points

An important aspect of the Jels 3 assemblage is the projectile point material. Four fragments were found, one of which is difficult to confidently classify as such. The remaining three are all basal fragments with only the tang remaining and can more confidently be classified as fragments of Havelte-style tanged points (). In terms of projectile point function, the size of these specimens—here especially, the two ballistically significant dimensions, width and thickness (cf. Shea Citation2006), as well as their derivatives—strongly supports their association with the bow-and-arrow, though no currently known archaeological remains of bows or complete arrow shafts can be connected to Hamburgian contexts (Lund Citation1993; Weber Citation2009; Riede Citation2010; Wild et al. Citation2018). When assessing the fractures of the Jels 3 points, they are all medial and appear to be bending or “snap” fractures, two of which have a minor cone fracture on the breakage surface and one additionally featuring a minor uni-facial spin-off fracture on its ventral side. This could indicate that they broke from impact damage, although such interpretations always remain uncertain (cf. Rots and Plisson Citation2014). All projectile point fragments from the Jels 3 assemblage show the same orientation on the blank blade, with the tang located at the proximal end. The crafting of the tang itself involved, in one case, retouch from alternating surfaces on the opposing edges (i.e. propeller retouch). Two specimens were retouched from the same surface. This retouch does not lead to the formation of a clear tang; instead, the converging retouch forms a tapered point-like tang instead.

Figure 6. The three projectile point tangs of the Havelte variant found at Jels 3. Drawn by Louise Hilmar, Moesgaard Museum.

Within the Hamburgian tradition itself, classic assemblages contain a morphologically rather wide variety of asymmetric single-shouldered projectile point forms, while the Havelte inventories are much more uniform in this regard. This is in glaring contrast to the subsequent Federmessergruppen tradition of the Allerød chronozone, where projectile point morphology varies widely with little regionally discernible patterning (Ikinger Citation1998; Matzig, Hussain, and Riede Citation2021). Notably, Havelte phase sites from Denmark such as Jels 1 and 2 (Holm and Rieck Citation1983, Citation1992), Slotseng C (Holm Citation1991), Sølbjerg 2 (Petersen and Johansen Citation1996), and Krogsbølle (Riede et al. Citation2019), as well as sites from northern Germany such as Ahrenshöft LA 58 D (Weber et al. Citation2010) and LA 73 (Clausen Citation1998), all contain projectile points that are strikingly uniform in shape. The projectile point variants from Jels 3 find close parallels in those assemblages, too. This rather drastic change between the two Hamburgian phases in only one specific artifact category is noteworthy, and it has been suggested that the homogeneity in projectile point shape and preparation in Havelte assemblages—especially in this northernmost region—could be conditioned by social norms (cf. Tehrani and Riede Citation2008) and may serve as proxies for the craft signatures of individual flintknappers (Riede Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2009, Citation2014b; Riede and Pedersen Citation2018; Riede et al. Citation2019).

Blade technology

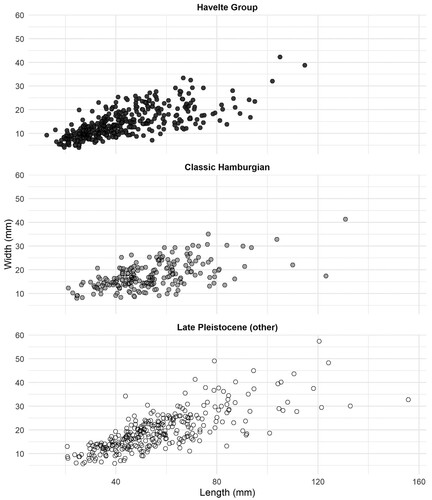

The analysis of the flint-working behavior at the Jels 3 site has been conducted following insights gained in the specifically Nordic (Madsen Citation1992; Ballin Citation1996; Sørensen Citation2006) and global (Inizan et al. Citation1999; Andrefsky Citation2005; Tostevin Citation2013) literature in this field. To assess the applied knapping methods and production technique, this analysis includes all non-cortical, complete blade blanks, with focus on variables such as linear measurements and technological attributes. Firstly, the blade material from the other two known Hamburgian inventories at the Jels Lakes—Jels 1 and 2—is included for comparison between sites within this micro-region of Hamburgian settlement. Secondly, several classic Hamburgian inventories from the Ahrensburg tunnel valley in northern Germany are included, as well, in order to evaluate the knapping behavior between 1) these two discrete regions and 2) classic and Havelte phase inventories. Thirdly, other Late Pleistocene inventories from both Germany and Denmark that belong to later technocomplexes such as the so-called Federmessergruppen and the Brommean are analyzed in order to provide a technological contrast to the Hamburgian (). The chronological and cultural relationship between these two latter technocomplexes is, however, unclear, with the Brommean likely being a sub-facies of the Federmessergruppen (cf. Riede Citation2017). The two are therefore referred to in the following under the summary label “Late Pleistocene (other).”

Table 3. Contextual parameters for the various inventories used for the technological analysis. DK = Denmark, DE = Germany, and SE = Sweden.

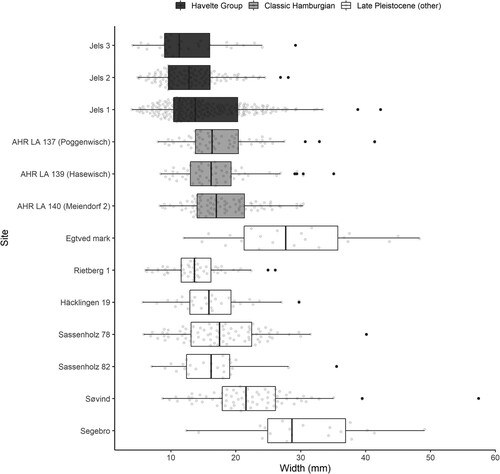

In terms of both length and width, it can be observed that blades from classic Hamburgian and Havelte inventories tend to distribute similarly, with the Havelte containing the smallest elements, which could allude to similar preferences in blade size at these locales. An expected overlap between the Hamburgian assemblages and those of a later date is also observed, albeit with the latter exhibiting a larger degree of size variability, as well as forming the majority of the larger elements and most extreme outliers (, ). In terms of size, the Hamburgian material overall stands out by reflecting uniformity when compared to material of later Pleistocene date.

Figure 7. Scatterplot visualizing the length and width of all blades. Note the larger degree of variability in the material succeeding the Hamburgian and how the majority of larger blades relate to this material.

Figure 8. Boxplot showing the distribution of blades in each assemblage according to their width. Note the close similarities between classic Hamburgian and Havelte Group assemblages and the larger degree of variation between locales of later Pleistocene date.

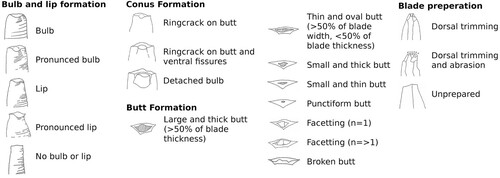

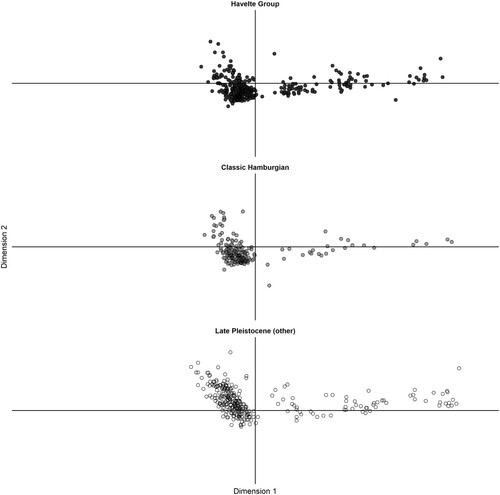

The technological attribute analysis focuses on the proximal end of the blades, as the morphological features present here are typically used as indicators for knapping techniques (). However, there are source critical elements associated with this methodological approach. The choices made by the flintknapper and what the analyst observe as technological attributes in the archaeological material are interrelated. However, by separating a lithic inventory into different predefined attribute categories, they risk becoming isolated. This understates their analytical value and the diversity in choices made by the past craftsperson, and the derived variation therefrom in the material cannot be retraced by the reader. Specific technological traits are therefore often treated typologically and qualitatively, which limits the potential for inferring relations between assemblages and processes of change over time (Bar-Yosef and Van Peer Citation2009; Riede and Jensen Citation2014). Furthermore, several studies have cast doubt on our abilities to confidently distinguish knapping techniques beyond the extremes of hard hammer percussion and pressure flaking (Damark and Apel Citation2008; Damlien Citation2015; Radinović and Kajtez Citation2021) or at least that much more controlled work and quantitative analyses need to be conducted in order to confidently infer technology from bulb and flake/blade morphology (Archer et al. Citation2017). Due to these issues, we here conduct an exploratory correspondence analysis (CA) at the assemblage level in order to evaluate the overall technology of the investigated inventories. This allows the analysis of all registered morphological features on a single blade at one time, as well as an assessment of how these features interrelate. Furthermore, it allows us to observe how all blades from the various inventories behave in relation to each other in a multivariate space and evaluate if it is possible here to discriminate between knapping techniques ().

Figure 10. CA scatterplots displaying the distribution of the blades of the various assemblages according to the technological attributes. Attributes that describe blade preparation (e.g. trimming, abrasion, and faceting of the butt), as well as punctiform butts and lip formation, appear within the lower left quadrant. Attributes that may indicate hard and direct knapping techniques (e.g. pronounced bulbar formation, conus formation, and large, thick, and plain butts), as well as limited blade preparation, appear within the upper left quadrant. Along the rightmost part of the x-axis are attributes that relate to fracture mechanics (e.g. broken butts and bulbar detachment). Although a significant overlap is present, both the Havelte and classic Hamburgian material cluster similarly, while material of the later Pleistocene traditions spreads out more evenly.

In the multivariate space of the CA, the technological variables orientate themselves in three main directions. Firstly, in the lower left quadrant are variables that describe blade preparation, such as trimming and abrasion techniques, as well as faceting of the butt. Attributes such as smaller and punctiform butts, as well as lip formation, also appear to be within this cluster. Secondly, in the upper left quadrant are a combination of pronounced bulb and conus formation, large, thick, and plain butts, and less preparation of the blade, all attributes which, together, indicate a hard and direct knapping technique. Thirdly, there are variables that orientate themselves in the rightmost part of the x-axis. These are broken butts and bulbar detachment, which are fracture mechanics more or less related to a range of knapping techniques.

The largest part of both Havelte and classic Hamburgian elements appear to cluster in the lower left quadrant, indicating that continuous preparation of the core in order to maximally control blade production is a consistent element in the Hamburgian knapping tradition. This correlates well with the actual cores from Jels 3, which generally appear strongly reduced and hence likely discarded in their final use phase. These cores have been rejuvenated often, and many smaller platform preparation flakes are present in the flake material. This is in complete alignment with Jels 1 and 2 (Madsen Citation1992). The bulb, lip, and butt morphology observed in this cluster could indicate the use of a soft-direct percussion technique, albeit less clearly. Overall, the material from Hamburgian contexts do appear to behave similarly across sites, indicating strong similarities in knapping behavior. The material from the non-Hamburgian contexts deviates from this pattern and appears to distribute more evenly between the lower- and upper-left quadrants, with the majority located within the latter. This not only indicates that a direct and hard knapping technique is more frequently applied here but also that the non-Hamburgian traditions practiced a more variable and perhaps more flexible knapping behavior than in the Hamburgian, where it appears that there were more normative guidelines for how lithic resources were utilized. These results are fully in line with earlier studies, which suggested a similar contrast in technological behavior between the strongly normative Hamburgian and the versatile Federmessergruppen (De Bie and Vermeersch Citation1998; De Bie and Caspar Citation2000; Sobkowiak-Tabaka Citation2020). There is, however, also a significant overlap between the investigated assemblages, which further supports the argument that it is difficult to discriminate, at the assemblage level, between specific knapping approaches with certainty, other than direct- and pressure techniques.

The main observation here is, however, that there is a vast bulk of blades from the three sites at Jels and the three classic Hamburgian sites which make a tight cluster. This observation conforms with the linear measurements. During analysis, the specific blade preparation technique en éperon (c.f. Barton Citation1991) was looked for, since it is known from both classic Hamburgian assemblages such as Teltwisch 1 and Poggenwisch, as well as the Havelte assemblage from Ahrenshöft LA 58D (Weber Citation2012) and Jels 1 (Madsen Citation1992). This specific preparation technique is, however, quite rare, and only examples that are probably nearer the “pseudo-éperons” described by Weber (Citation2012) could be observed in the Jels 3 material, as well as in the inventory from Meiendorf 2. In sum, the blade technology at the Jels 3 site falls entirely within the Hamburgian tradition and is, to all intents and purposes, identical to the other known locales at the Jels lakes. It is also fully comparable with all other southern Scandinavian Havelte inventories.

Discussion

The Jels 3 site is interesting in several ways. Firstly, it is a relatively small yet tool-rich site, dominated by scrapers and burins. Taken at face value, its tool spectrum differs from its close neighbors Jels 1 and 2, which also differ from each other. In open-air inventories of moderate size, such frequency differences can be readily explained by a range of post-depositional processes. They may also imply a certain, even if limited, degree of task differentiation in this landscape (Binford Citation1980) or differing occupation duration (Richter Citation1990) or intensity (Pedersen Citation2009). Importantly, and in spite of the limited size of the assemblage, the entire diagnostic lithic repertoire of the Havelte phase is represented: Zinken, burins on blade, blade end-scrapers with/without fine lateral retouch, Havelte phase projectile points, and flat bipolar single-fronted cores. The site is placed on a small plateau in the landscape, corresponding well with other known sites. There is no well-defined hearth, but the presence of burned flint indicates that some source of fire was present at the time of occupation. It is most likely that only a very few individuals were active at Jels 3 and only for a relatively short time (cf. Richter Citation1990). In the absence of use-wear analysis—often futile on such heavily patinated artifacts—inferences regarding the activities carried out at the site may be tentative at best. If we accept the linkage of formal tool types to certain economic activities, then tool manufacturing, as well as butchering, hide-scraping, and bone/antler-working, would have taken place at Jels 3, all carried out by the warmth and light of a small camp fire. The few broken projectile points found on-site might also point towards the aftermath of a hunt, where used and broken weapon components were discarded and new ones made and taken along to the next site (Caspar and De Bie Citation1996; De Bie and Caspar Citation2000). This interpretation aligns well with the character of southern Scandinavian Havelte sites: they are short-term and ephemeral, yet appear to represent a wide spectrum of domestic activities.

The Jels 3 locale is placed within one of only two settlement pockets in modern day Denmark that exclusively contain sites related to the Havelte tradition. These two discrete micro-regions act as satellite settlements in an otherwise barren landscape empty of archaeological finds in the absolute northern periphery of Hamburgian distribution, and thereby human dispersal, during this period. Further south, the Ahrensburg tunnel valley is more or less speckled with sites of the classic Hamburgian. Equidistant between these two areas, the sites by Ahrenshöft are placed at more than a 100 km distance to both. Especially interesting about Ahrenshöft is the fact that inventories containing Havelte tanged points and classic Hamburgian shouldered points, respectively, are situated in close proximity to each other (Hartz Citation1987) and that at the Ahrenshöft LA 73 site, they co-occur. This may be due to cryoturbation but cannot confidently be assigned to this natural phenomenon (Clausen Citation1998). Instead, this could be interpreted to indicate a close temporal proximity between bearers of Havelte tanged points and those carrying classic shouldered points. This pattern points toward a rather rapid expansion, moving from one point to another over a very short period of time. The strong similarities between the sites within the cluster at Jels described in this paper also indicate a very short duration of settlement. This settlement pattern is expected with the first phase of a leap-frog settlement model (see ). The large gaps in settlement are only settled in a more advanced phase, when better knowledge of the settled landscapes is achieved. This speaks to a focused, as well as spatially and temporally limited, use of this recently de-glaciated landscape characterized by targeted but also limited exploration and exploitation.

Essential to understanding the adaptability, and thereby ability, of Hamburgian groups to map onto these northernmost and unexplored landscapes is the concept of landscape learning. Pioneering groups need some form of predefined knowledge of their destination (i.e. earlier experience with environments that are used as analogues), but a rapid update of their locational, limitational, and social knowledge (sensu Rockman Citation2003, Citation2009, Citation2012) is crucial. With a leap-frogging model where the movement of a population is predicted to be temporally fast, spatially extended, and directed along a somewhat narrow pathway, locational knowledge may be collected rather quickly, but both limitational and social knowledge are difficult to update. For an advancing wave, movement is shorter in both space and time with a higher probability that populations can, to some degree, continue to interact with their previously inhabited and known environments. While locational knowledge may need to be updated rather quickly in such a scenario, both limitational and social knowledge can be brought up to date at a slower pace (Rockman Citation2009). Rockman (Citation2003) develops a biogeographical approach where three different barriers (population, social, and knowledge) for dispersing populations are described. Population barriers describe the compatibility between already-resident and incoming populations in terms of population density, compatibility of economic systems, and carrying capacity limitations (i.e. available niche space). Social barriers describe the resident population’s defense and information transmission systems. Knowledge barriers describe whether any usable, previously collected information (locational, limitational, or social) exists. In the case of a pioneering population, the barriers that relate to already resident populations (population and social) are expected to be low or non-existent, while the knowledge barrier is high. In the case of the Hamburgian, it appears that these groups of hunter-gatherers faced (due to the leap-frog settlement pattern) a great need to update all three information types (locational, limitational, and social), as well as (due to the lack of any resident populations), a high knowledge barrier.

Exactly how challenging this learning process was depends on the degree to which the newly entered landscape differed from the one left behind (Meltzer Citation2003). The Lapita people, linked to the pioneer human settlement of the Pacific, dealt with a high knowledge barrier by carrying crops and domestic animals with them in order to transform the uninhabited island biotas into an environment already known to the Lapita settlers, effectively transporting the entire landscape (Kirch Citation1997, 217–220). The Hamburgian manufacturing groups did not in the same sense bring with them an entire learned landscape package such as the Lapita, but they did bring with them their whole niche package by moving their entire households to significantly focus on reindeer hunting. This approach focuses on importing analog knowledge of an adaptation strategy that is already tested on a known environment. While the assemblages investigated here all stem from open-air sites procured with varying methods (see ), they still offer salient insights. In a northern European context, sites from this period are located in the open land and are variously disturbed by recent agricultural activities. Yet, because of their rarity, each locale makes up a significant share of the overall archaeological record worthy of scrutiny. Our technological analysis shows that—in general—there appears to be certain patterns of uniformity in the Hamburgian material, while material from subsequent periods stands out by being generally not only larger in bulk, but also more variable. Rather than linking this homogeneity to skill, we suggest that 1) the Hamburgian tradition followed rather strict norms for stone-working techniques and that 2) the producers of the northernmost sites were closely related chronologically and socially. In later cultures of the Late Pleistocene in the region, this pattern changes, suggesting that not only were knapping norms more relaxed but that more generations of knappers are represented in the material. While resources such as lithic outcrops that are static in space and time would be the first and easiest to learn (Kelly Citation2003; Meltzer Citation2003; Roebroeks Citation2003; Rockman Citation2009), the strict guidelines in knapping behavior followed by Hamburgian populations and their exhaustive utilization of lithic raw material could indicate a lack of updating locational knowledge in favor of relying on “imported” knowledge.

A strategy of closely targeting known ecological elements may result in successful exploitation of the unknown landscapes, which the faunal remains of several reindeer individuals found in a kettle-hole at the Slotseng locale could hint at. However, this strategy may also result in these groups of people carrying with them presumptions about the characteristics of an, at the end of the day, still unfamiliar ecosystem (potential productivity, resilience, and stress signals) that are based on the ostensible similarity to their environment of origin. While the Late Glacial period is related to an overall global warming, it is also characterized by severe climatic fluctuations (Rasmussen et al. Citation2014) affecting the stability of regional and local ecosystems. Dispersing Hamburgian groups reading their new environments by false analogy may then have masked critical thresholds and their related signals (McGovern Citation1994, 149; Meltzer Citation2003).

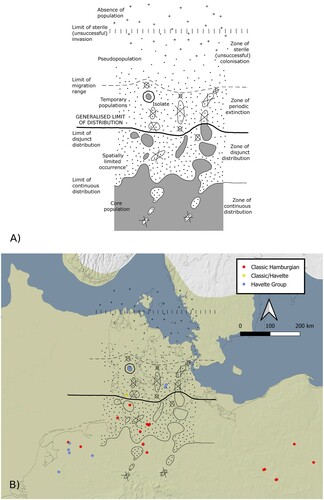

To view these dispersals in both geographic, as well as environmental, space, the model suggested here can be coupled with expected range boundaries (i.e. zones of distribution) for a species’ ability to successfully disperse from and survive outside of a core population (Gorodkov Citation1986; Roebroeks Citation2006; ). Viewing the archaeological evidence afresh within such a framework of various zones of distribution suggests that the locales from northern Germany fit rather well within the zone of “disjunct distribution,” with sites relatively evenly distributed, yet still reflecting an ephemeral use of the landscape. The northernmost sites in present-day Denmark would fall within the zone of “periodic extinction” characteristic of temporary dispersals that are highly vulnerable to extinction events. This zone lies beyond the limit of a generalized distribution, which is a boundary that describes the margin of a population’s physical adaptive range as the size of the population decreases. Groups may occupy areas beyond this boundary at certain intervals, and they may even leave behind archaeological evidence of their presence, but the occupations themselves are likely to have been short-lived and ephemeral. If such dispersals are successful, however, they may function as bridgeheads into these sub-marginal zones, allowing subsequent dispersals to fill in the empty spaces and thereby expanding the generalized limit of distribution (i.e. range). The Ahrenshöft area can be interpreted as a pivotal point, being the very northern margin of settlement for practitioners of the classic Hamburgian tradition and the very departure point and stepping stone for groups practicing the Havelte tradition that expanded into the recently de-glaciated landscapes of present-day Denmark. The archaeological evidence and the temporary character of these two distinct isolates so far removed from areas that may be interpreted as continuous distribution zones, indicates an isolation of this population and a depressed population fitness (i.e. the survival rate and thereby reproductive rate).

Figure 11. A) A schematic of the limitations of any given population’s ability to disperse into various geographic ranges while maintaining a sustainable occupation. Grey indicates constant populations, crossed out circles indicate temporary populations, dots indicate living individuals, and pluses indicate individuals susceptible to extinction (Gorodkov Citation1986; Roebroeks Citation2006). B) The same schematic superimposed onto the distribution of securely dated Hamburgian sites. Note that the northernmost sites are located within the “zone of periodic extinction” (i.e. an unsustainable occupation). Map made using QGIS (QGIS Development Team Citation2019). The basemap was compiled by ZBSA. For more information and the full list of references, please see: http://www.zbsa.eu/zbsa/publikationen/open-access-datenmaterial/epha-european-prehistoric-and-historic-atlas.

While these factors illuminate the question as to why the earliest attempt at settling the northern limits of Europe failed, the question regarding what followed and the consequences it had for these pioneering groups remains unanswered. The seeming disappearance of the Hamburgian from the archaeological record could, on the one hand, be related to the extinction of these small isolated groups, which in turn would suggest the termination of their tradition. However, it could, on the other hand, be related to extirpation, which describes a situation where a population simply no longer exists in a particular region but has moved elsewhere (cf. Riede Citation2014b). The fact that the overall “identity” of the Hamburgian disappears from the archaeological record would imply assimilation with more southerly groups (i.e. Federmessergruppen). Yet, no assemblages are known at present where definitive Hamburgian elements are contained within a later Federmessergruppen assemblage. While there is a continuum from a very local extirpation to complete extinction, the Hamburgian may lie more on the extinction end of this spectrum. Whether this extinction was cultural or biological is unknown, but this study at least suggests that, concerning the lithic technology, the Hamburgian differs from subsequent traditions—its cultural extinction at the end of GI-1e may be a reasonable cause.

Conclusion

The site of Jels 3 provides a rare and important contribution to the limited archaeological record for, as well as our understanding of, the Hamburgian culture in southern Scandinavia. The assemblage underlines the homogeneity of the southern Scandinavian material both in terms of the ecological/topographic setting of the sites as well as in terms of the material culture specificities. The many parallels between the southern Scandinavian Havelte phase sites raise questions regarding the strict contemporaneity of these sites, as well as regarding the nature and duration of Havelte phase presence in southern Scandinavia per se. Refitting between the concentrations present at the site of Jels 3 itself would more confidently establish that a single event is represented. Experimental attempts at refitting of the Jels 1 and 2 inventories have already provided promising results (Pedersen Citation2021). By extension, refitting between all three sites known at the Jels lakes could test notions of strict contemporaneity across sites (cf. Scheer Citation1986; Leesch et al. Citation2010), which again would support the hypothesis of a chronologically restricted occurrence of this techno-complex in southern Scandinavia. Renewed efforts at dating the Hamburgian occupation in the region and at analyzing Hamburgian technology with a view towards better capturing within- and between-assemblage variation—and the contrast of the Hamburgian with the following Federmessergruppen—would almost certainly shed additional light on the fate of the Havelte phase expeditions into southern Scandinavia. In sum, the fortuitous discovery and excavation of Jels 3, an extremely rare site from this earliest part of southern Scandinavian prehistory, offers the potential for providing important new insights—generated in the field and the laboratory—into this elusive period. As shown by our 2011 survey, the archaeological potential of the area around the Jels lakes is far from exhausted.

Geolocation Information

Longitude: 9.219177; Latitude: 55.358957.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (10.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (10.4 KB)Acknowledgements

F. R.’s contribution to this paper is part of CLIOARCH, an ERC Consolidator Grant project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 817564). The technological data on the assemblages from Rietberg 1, Häcklingen 19, Sassenholz 78 and 82, Søvind, and Segebro was collected by Christian Steven Hoggard as part of the LAPADIS project (grant #6107-00059B awarded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark), and we would like to thank the University of Cologne, Museum Stade, Moesgaard Museum, and the Historical Museum at Lund University, respectively, for granting access to these. We would also like to thank the Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie (ZBSA) and the Landesmuseum Schleswig-Holstein for their hospitality and for granting access to the AHR LA 137 (Poggenwisch), AHR LA 139 (Hasewisch), and AHR LA 140 (Meiendorf 2) inventories, as well as a special thanks to Dr. Mara-Julia Weber for her assistance. Similarly, we thank VejleMuseerne for kindly making the material from Egtved Mark available for analysis. We would also like to thank David Nicolas Matzig for his assistance regarding the analyses conducted in the R statistical environment. Lastly, J. B. P. would like to thank the University of Aarhus for granting a Ph.D. fellowship.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Data and Code Availability

All analyses and visualizations presented in this paper—unless stated otherwise—were prepared in R version 4.1.3 (R Core Team Citation2022) using the following packages: tidyverse (>= 1.3.1), FactoMineR (>= 2.4), here (>= 1.0.1), raster (>= 3.5–15), sp (>= 1.4–6), and maptools (>= 1.1–1). All datasets generated and/or analyzed in the current study, as well as all code associated with this paper, are available in the accompanying research compendium on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6457202.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jesper B. Pedersen

Jesper B. Pedersen (M.A. 2019, Aarhus University) is a Ph.D. student at Aarhus University, department of archaeology and heritage studies, under the supervision of Professor Felix Riede. His research interests include Palaeolithic societies, paleodemography, prehistoric individuals, cultural transmission theory, lithic technology, computational methods, geometric morphometrics, and climate modelling.

Martin E. Poulsen

Martin E. Poulsen (M.A. 2008, Aarhus University) is currently employed at Museum Sønderskov in southern Denmark. He is an experienced field archaeologist specializing in Nordic Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age society with a particular focus on settlement and building structures.

Felix Riede

Felix Riede (Ph.D. 2007, University of Cambridge) is Professor of Archaeology at Aarhus University in Denmark. His research focuses on climatic change and cultural responses in prehistoric European populations, especially during the Final Palaeolithic. Within a framework of extended cultural evolutionary theory and using computational and archaeometric methods, he seeks to relate climate, environment, and culture change to each other.

Notes

1 The Jels 3 site was discovered during cultural resource management investigations and not through a targeted fieldwork campaign with an ample budget and clear research questions to explore. The excavation and documentation of the site was therefore limited by the budget constraints of this contract work. However, in the context of such an endeavor, the excavators have carried out a rigorous excavation, making the documentation of the Jels 3 site as detailed and informative as possible under these conditions.

References

- Ammerman, A. J., and M. W. Feldman. 1974. “On the ‘Making’ of an Assemblage of Stone Tools.” American Antiquity 39 (4): 610–616. https://doi.org/10.2307/278909.

- Andersen, S. H. 2016. “Rensdyrjægere på Farten – Opholdssteder fra Senistid i Østjylland.” Kuml 65: 9–53.

- Anderson, D. G., and J. C. Gillam. 2000. “Paleoindian Colonization of the Americas: Implications from an Examination of Physiography, Demography, and Artifact Distribution.” American Antiquity 65 (1): 43–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/2694807.

- Andrefsky, W. 2005. Lithics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Anthony, D. W. 1990. “Migration in Archeology: The Baby and the Bathwater.” American Anthropologist 92 (4): 895–914. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1990.92.4.02a00030.

- Archer, W., C. M. Pop, Z. Rezek, S. Schlager, S. C. Lin, M. Weiss, T. Dogandzic, D. Desta, and S. P. McPherron. 2017. “A Geometric Morphometric Relationship Predicts Stone Flake Shape and Size Variability.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 10 (8): 1991–2003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0517-2.

- Ballin, T. B. 1996. Klassifikationssystem for Stenartefakter. Oslo: Universitetets oldsaksamling.

- Ballin, T. B., A. Saville, R. Tipping, T. Ward, R. Housley, L. Verrill, M. Bradley, C. Wilson, P. Lincoln, and A. MacLeod. 2018. Reindeer Hunters at Howburn Farm, South Lanarkshire. A Late Hamburgian Settlement in Southern Scotland - its Lithic Artefacts and Natural Environment. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Bar-Yosef, O., and P. Van Peer. 2009. “The Chaine Operatoire Approach in Middle Paleolithic Archaeology.” Current Anthropology 50: 103–131. https://doi.org/10.1086/592234.

- Barton, R. N. E. 1991. “The en éperon Technique in the British Late Upper Palaeolithic.” Lithics 11: 31–33.

- Beaton, J. M. 1991. “Colonizing Continents: Some Problems from Australia and the Americas.” In The First Americas: Search and Research, edited by T. D. Dillehay, and D. J. Meltzer, 209–230. Boca Raton: CRC.

- Becker, C. J. 1971. “Late Palaeolithic Finds from Denmark.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 37 (2): 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00012597.

- Binford, L. R. 1980. “Willow Smoke and Dogs’ Tails: Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems and Archaeological Site Formation.” American Antiquity 45 (1): 4–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/279653.

- Boismier, W. A. 1997. Modeling the Effects of Tillage Processes on Artifact Distributions in the Ploughsoil. A Simulation Study of Tillage-Induced Pattern Formation. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Bokelmann, K. 1991. “Some new Thoughts on old Data on Humans and Reindeer in the Ahrensburg Tunnel Valley in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.” In Late Glacial in North-West Europe: Human Adaptation and Environmental Change at the end of the Pleistocene, edited by N. Barton, A. J. Roberts, and D. A. Roe, 72–81. Oxford.

- Bratlund, B. 1994. “A Survey of the Subsistence and Settlement Pattern of the Hamburgian Culture in Schleswig-Holstein.” Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 41 (1): 59–93.

- Breest, K., and K. Gerken. 2008. “Kulturelle Einflüsse und Beziehungen im Spätpaläolithikum Niedersachsens–Ein Diskussionsbeitrag Sassenholz 78 und 82, Ldkr. Rotenburg (Wümme).” Die Kunde, Neue Folge 59: 1–38.

- Brinch Petersen, E. 2009. “The Human Settlement of Southern Scandinavia 12500-8700 cal BC.” In Humans, Environment and Chronology of the Late Glacial of the North European Plain - Proceedings of Workshop 14 (Comission XXXII) of the 15th U.I.S.P.P. Congress, Lisbon, September 2006, edited by M. Street, N. Barton, and T. Terberger, 89–130. Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums: Mainz.

- Caspar, J.-P., and M. De Bie. 1996. “Preparing for the Hunt in the Late Palaeolithic Camp at Rekem, Belgium.” Journal of Field Archaeology 23 (4): 437–460. https://doi.org/10.1179/009346996791973747.

- Clausen, I. 1998. “Neue Untersuchungen an Späteiszeitlichen Fundplätzen der Hamburger Kultur bei Ahrenshöft, Kr. Nordfriesland. Ein Vorbericht.” Archäologische Nachrichten aus Schleswig-Holstein 8: 8–49.

- Clausen, I., and A. Guldin. 2017. “Die Spätjungpaläolitischen Stationen des Ahrensburger Tunneltals in Neuen Kartenbildern (Gem. Ahrensburg, Kr. Stormarn).” In Interaktionen Ohne Grenzen - Beispiele Archäologischer Forschungen am Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts, edited by B. V. Eriksen, A. Abegg-Wigg, R. Bleile, and U. Ickerodt, 11–21. Kiel/Hamborg: Wachholtz Verlag.

- Damark, K., and J. Apel. 2008. “The Dogma of Immaculate Perception. An Experimental Study of Bifacial Arrowheads and a Contribution to the Discussion on the Relationship Between Personal Experience and Formalised Analysis in Experimental Archaeology.” In Technology in Archaeology – Proceedings of the SILA Workshop: The Study of Technology as a Method for Gaining Insight Into Social and Cultural Aspects of Prehistory, the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen, November 2-4, 2005, edited by M. Sørensen, and P. Desrosiers, 173–186. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Damlien, H. 2015. “Striking a Difference? The Effect of Knapping Techniques on Blade Attributes.” Journal of Archaeological Science 63: 122–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2015.08.020.

- Davies, W. 2001. “A Very Model of a Modern Human Industry: New Perspectives on the Origins and Spread of the Aurignacian in Europe.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 67: 195–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00001663.

- De Bie, M., and J.-P. Caspar. 2000. Rekem - A Federmesser Camp on the Meuse River Bank. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- De Bie, M., and P. M. Vermeersch. 1998. “Pleistocene-Holocene Transition in Benelux.” Quaternary International 49–50: 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-6182(97)00052-9.

- Eriksen, B. V. 1999. “Late Palaeolithic Settlement in Denmark - how do we Read the Record?” In Post-pleniglacial re-Colonisation of the Great European Lowland: Papers Presented at the Conference Organised by the International Union of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences, Commission 8, Held at the Jagellonian University, Kraków, in June 1998, edited by M. Kobusiewicz, and J. K. Kozlowski, 157–173. Krakow: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

- Eriksen, B. V. 2006. “Hvorfor Finder vi så få ældre Stenalders Lokaliteter ved Forundersøgelserne – og Hvad kan vi Gøre ved det?” Arkæologisk Forum 15: 13–16.

- Fischer, A. 1988. “A Late Palaeolithic Flint Workshop at Egtved, East Jutland.” Journal of Danish Archaeology 7 (1): 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0108464X.1988.10589994.

- Fischer, A. 2012. “The Fensmark Settlement and the Almost Invisible Late Palaeolithic in Danish Field Archaeology.” Danish Journal of Archaeology 1 (2): 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2012.760895.

- Fort, J., T. Pujol, and L. L. Cavalli-Sforza. 2004. “Palaeolithic Populations and Waves of Advance.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 14 (1): 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774304000046.

- Gorodkov, K. B. 1986. “Three-dimensional Climatic Model of Potential Range and Some of its Characteristics. II.” Entomological Review 65: 1–18.

- Grimm, S. B., and M. J. Weber. 2008. “The Chronological Framework of the Hamburgian in the Light of old and new C14 Dates.” Quartär 55: 17–40.

- Grønnow, B. 1985. “Meiendorf and Stellmoor Revisited: An Analysis of Late Palaeolithic Reindeer Exploitation.” Acta Archaeologica 56: 131–166.

- Hartz, S. 1987. “Neue Spätpaläolithische Fundplätze bei Ahrenshöft, Kreis Nordfriesland.” Offa 44: 5–52.

- Hartz, S. 1990. “Artefaktverteilungen und Ausgewählte Zusammensetzungen auf den Spätglazialen Fundplatz Hasewisch, Kreis Storman, BRD.” In The big Puzzle: International Symposium on Refitting Stone Artefacts, Monrepos 1987, edited by E. Cziesla, S. Eickhoff, N. Arts, and D. Winter, 405–429. Bonn.

- Hazelwood, L., and J. Steele. 2003. “Colonizing new Landscapes. Archaeological Detectability of the First Phase.” In Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes: The Archaeology of Adaptation, edited by M. Rockman, and J. Steele, 203–221. London: Routledge.

- Holm, J. 1991. “Settlements of the Hamburgian and Federmesser Cultures at Slotseng, South Jutland.” Journal of Danish Archaeology 10 (1): 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0108464X.1991.10590050.

- Holm, J., and F. Rieck. 1983. “Jels 1 - the First Danish Site of the Hamburgian Culture. A Preliminary Report.” Journal of Danish Archaeology 2: 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/0108464X.1983.10589888.

- Holm, J., and F. Rieck. 1992. Istidsjægere ved Jelssøerne. Haderslev.

- Holzkämper, J., A. Maier, and J. Richter. 2013. ““„Dark Ages” Illuminated–Rietberg and Related Assemblages Possibly Reducing the Hiatus Between the Upper and Late Palaeolithic in Westphalia.”.” Quartär 60: 115–136. https://doi.org/10.7485/QU60_6.

- Houmark-Nielsen, M., and K. H. Kjær. 2003. “Southwest Scandinavia, 40–15 kyr BP: Palaeogeography and Environmental Change.” Journal of Quaternary Science 18 (8): 769–786. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.802.

- Housley, R., C. Gamble, M. Street, and P. Pettitt. 1997. “Radiocarbon Evidence for the Lateglacial Human Recolonisation of Northern Europe.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 63: 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X0000236X.

- Ikinger, E.-M. 1998. Der Endeiszeitliche Rückenspitzen-Kreis Mitteleuropas. Münster: LIT.

- Inizan, M.-L., M. Reduron-Ballinger, H. Roche, and J. Tixier. 1999. Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone. Nanterre: CREP.

- Ivanovaité, L., and F. Riede. 2018. “The Final Palaeolithic Hunter-Gatherer Colonisation of Lithuania in Light of Recent Palaeoenvironmental Research.” Open Quarternary 4 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.5334/oq.39.

- Kabacinski, J., and I. Sobkowiak-Tabaka. 2009. “Big Game Versus Small Game Hunting - Subsistence Strategies of the Hamburgian Culture.” In Humans, Environment and Chronology of the Late Glacial of the North European Plain - Proceedings of Workshop 14 (Comission XXXII) of the 15th U.I.S.P.P. Congress, Lisbon, September 2006, edited by M. Street, N. Barton, and T. Terberger, 67–75. Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums: Mainz.

- Kelly, R. L. 2003. “Colonization of new Land by Hunter-Gatherers: Expectations and Implications Based on Ethnographic Data.” In Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes: The Archaeology of Adaptation, edited by M. Rockman, and J. Steele, 44–58. London: Routledge.

- Kelly, R. L., and L. C. Todd. 1988. “Coming Into the Country: Early Paleoindian Hunting and Mobility.” American Antiquity 53 (2): 231–244. https://doi.org/10.2307/281017.

- Kirch, P. V. 1997. The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Krüger, S., and M. Damrath. 2020. “In Search of the Bølling-Oscillation: A new High Resolution Pollen Record from the Locus Classicus Lake Bølling, Denmark.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 29 (2): 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-019-00736-3.

- Larsson, L. 1994. “The Earliest Settlement in Southern Sweden - Late Paleolithic Settlement Remains at Finjasjön, in the North of Scania.” Current Swedish Archaeology 2 (1): 159–177. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.1994.09.

- Leesch, D., J. Bullinger, M.-I. Cattin, W. Müller, and N. Plumettaz. 2010. “Hearths and Hearthrelated Activities in Magdalenian Open-air Sites: The Case Studies of Champréveyres and Monruz (Switzerland) and Their Relevance to an Understanding of Upper Paleolithic Site Structure.” In The Magdalenian in Central Europe. New Finds and Concepts, edited by M. Poltowicz-Bobak, and D. Bobak, 53–69. Rzeszow: Mitel.

- Lund, M. 1993. “Vorschäfte für Kerbspitzen der Hamburger Kultur.” Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 23 (4): 405–411.

- Madsen, B. 1992. “Hamburgkulturens Flintteknologi i Jels.” In Istidsjægere ved Jelssøerne, edited by J. Holm, and F. Rieck, 93–131. Haderslev.

- Maier, A. 2015. The Central European Magdalenian. Regional Diversity and Internal Variability. New York: Springer.

- Matzig, D. N., S. T. Hussain, and F. Riede. 2021. “Design Space Constraints and the Cultural Taxonomy of European Final Palaeolithic Large Tanged Points: A Comparison of Typological, Landmark-Based and Whole-Outline Geometric Morphometric Approaches.” Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 4 (4): 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00097-2.

- McGovern, T. H. 1994. “Management for Extinction in Norse Greenland.” In Historical Ecology, edited by C. L. Crumley, 127–154. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

- Meltzer, D. J. 2003. “Lessons in Landscape Learning.” In Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes: The Archaeology of Adaptation, edited by M. Rockman, and J. Steele, 222–241. London: Routledge.

- Meltzer, D. J. 2004. “Modeling the Initial Colonization of the Americas: Issues of Scale, Demography, and Landscape Learning.” In The Settlement of the American Continents: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Human Biogeography, edited by C. M. Barton, G. A. Clark, D. R. Yesner, and G. A. Pearson, 123–127. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Mortensen, M. F., J. Olsen, J. Holm, and C. Christensen. 2014. “Right Time, Right Place – Dating the Havelte Phase in Slotseng, Denmark.” In Lateglacial and Postglacial Pioneers in Northern Europe, edited by F. Riede, and M. Tallavaara, 11–22. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Mugaj, J. 2018. “Hunter-Gatherers on the Lowland - Some Remarks on the Hamburgian Re-Colonisation of Northern Europe.” Archaeologia Baltica 25: 12–21. https://doi.org/10.15181/ab.v25i0.1827.

- Pedersen, K. B. 2009. Stederne og Menneskene. Istidsjægere Omkring Knudshoved Odde. Gylling: Forlaget Museerne.dk.

- Pedersen, J. B. 2021. “Tidsrummet for Hamborgkulturens Bosættelse ved Jelssøerne Kommenteret Gennem Forsøg på Flintsammensætning.” Arkæologi i Slesvig-Archäologie in Schleswig 18 (2020): 303–317.

- Pedersen, J. B., A. Maier, and F. Riede. 2019. “A Punctuated Model for the Colonisation of the Late Glacial Margins of Northern Europe by Hamburgian Hunter-Gatherers.” Quartär 65 (2018): 85–104. https://doi.org/10.7485/QU65_4.

- Petersen, P. V. 2006. “White Flint and Hilltops - Late Palaeolithic Finds in Southern Denmark.” In Across the Western Baltic - Proceedings of the Archaeological Conference ‘The Prehistory and Early Medieval Period in the Western Balitic’ in Vordingborg, South Zealand, Denmark, March 27th-29th 2003, edited by K. M. Hansen, and K. B. Pedersen, 57–74. Odense: one. 2one.

- Petersen, P. V., and L. Johansen. 1996. “Tracking Late Glacial Reindeer Hunters in Eastern Denmark.” In The Earliest Settlement of Scandinavia and Its Relationship with Neighbouring Areas, edited by L. Larsson, 75–88. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

- Poulsen, M. E. 2013. Beretning for arkæologisk systematisk undersøgelse af HBV j.nr. 1316 Nedersøparken II, Jels. Museet på Sønderskov. Excavation report.

- QGIS Development Team. 2019. QGIS Geographic Information System, 3.10. A Coruña. Open Source Geospatial Foundation.

- Radinović, M., and I. Kajtez. 2021. “Outlining the Knapping Techniques: Assessment of the Shape and Regularity of Prismatic Blades Using Elliptic Fourier Analysis.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 38: 103079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103079.

- Rasmussen, S. O., M. Bigler, S. P. Blockley, T. Blunier, S. L. Buchardt, H. B. Clausen, I. Cvijanovic, D. Dahl-Jensen, S. J. Johnsen, H. Fischer, V. Gkinis, M. Guillevic, W. Z. Hoek, J. J. Lowe, J. B. Pedro, T. Popp, I. K. Seierstad, J. P. Steffensen, A. M. Svensson, P. Vallelonga, B. M. Vinther, M. J. C. Walker, J. J. Wheatley, and M. Winstrup. 2014. “A Stratigraphic Framework for Abrupt Climatic Changes During the Last Glacial Period Based on Three Synchronized Greenland ice-Core Records: Refining and Extending the INTIMATE Event Statigraphy.” Quaternary Science Reviews 106: 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.007.

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Richter, J. 1990. “Diversität als Zeitmaß im Spätmagdalénien.” Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 20: 249–257.

- Richter, P. B. 2001. ““Ein Spätpaläolithischer Schlagplatz Innerhalb Eines Mehrphasigen Siedlungsareals bei Bienenbüttel.” Ldkr. Uelzen.”.” Nachrichten aus Niedersachsens Urgeschichte 70 (1): 3–36.

- Richter, P. B. 2002. “Erste Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen Eines Spätpaläolithischen und Endneolithischen Siedlungsareals bei Häcklingen, Ldkr. Lüneburg.” Nachrichten aus Niedersachsens Urgeschichte 71 (1): 3–28.

- Richter, J. 2012. Rietberg und Salzkotten-Thüle: Anfang und Ende der Federmessergruppen in Westfalen. Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH.

- Riede, F. 2005. “To Boldly Go Where No (Hu-)Man Has Gone Before. Some Thoughts on The Pioneer Colonisations of Pristine Landscapes.” Archaeological Review from Cambridge 20 (1): 20–38.

- Riede, F. 2007. “Stretched Thin, Like Butter on Too Much Bread … ’: Some Thoughts About Journeying in the Unfamiliar Landscapes of Late Palaeolithic Southern Scandinavia.” In Prehistoric Journeys, edited by R. Johnson, and V. Cummings, 8–20. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Riede, F. 2009. “Climate Change, Demography and Social Relations: An Alternative View of the Late Palaeolithic Pioneer Colonization of Southern Scandinavia.” In Mesolithic Horizons - Papers Presented at the Seventh International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, Belfast 2005, edited by S. B. McCartan, R. Schulting, G. Warren, and P. Woodman, 3–10. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Riede, F. 2010. “Hamburgian Weapon Delivery Technology - a Quantitative Comparative Approach.” Before Farming 2010 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3828/bfarm.2010.1.1.

- Riede, F. 2014a. “The Resettlement of Northern Europe.” In Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers, edited by V. Cummings, P. Jordan, and M. Zvelebil, 556–581. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Riede, F. 2014b. “Success and Failure During the Late Glacial Pioneer Human re-Colonisation of Southern Scandinavia.” In Lateglacial and Postglacial Pioneers in Northern Europe, edited by F. Riede, and M. Tallavaara, 33–52. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Riede, F. 2017. “The ‘Bromme Problem’ - Notes on Understanding the Federmessergruppen and Bromme Culture Occupation in Southern Scandinavia During the Allerød and Early Younger Dryas Chronozones.” In Problems in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research, edited by M. Sørensen, and K. B. Pedersen, 61–85. Viborg: Specialtrykkeriet.

- Riede, F., and D. S. Jensen. 2014. “Book Review: Mara-Julia Weber: From Technology to Tradition. Re-Evaluating the Hamburgian-Magdalenian Relationship. Untersuchungen und Materialien zur Steinzeit in Schleswig-Holstein und im Ostseeraum 5. Neumünster 2012. 256 Sider. ISBN 978-3-529-018570-2. Pris: 50 EUR.” Kuml 63: 386–388.

- Riede, F., and J. B. Pedersen. 2018. “Late Glacial Human Dispersals in Northern Europe and Disequilibrium Dynamics.” Human Ecology 46 (5): 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-017-9964-8.

- Riede, F., M. J. Weber, B. Westen, K. M. Gregersen, K. K. Lundqvist, A. S. Murray, P. S. Henriksen, and M. F. Mortensen. 2019. “Krogsbølle, a new Hamburgian Site in Eastern Denmark.” In The Final Palaeolithic of Northern Eurasia - Proceedings of the Amersfoort, Schleswig and Burgos UISPP Commission Meetings, edited by B. V. Eriksen, E. Rensink, and S. Harris, 11–30. Kiel: Verlag Ludwig.

- Rockman, M. 2003. “Knowledge and Learning in the Archaeology of Colonization.” In Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes: The Archaeology of Adaptation, edited by M. Rockman, and J. Steele, 3–24. London: Routledge.

- Rockman, M. 2009. “Landscape Learning in Relation to Evolutionary Theory.” In Macroevolution in Human Prehistory, edited by A. M. Prentiss, I. Kujit, and J. C. Chatters, 51–71. New York: Springer.

- Rockman, M. 2010. “New World with a New Sky: Climatic Variability, Environmental Expectations, and the Historical Period Colonization of Eastern North America.” Historical Archaeology 44 (3): 4–20.

- Rockman, M. 2012. “Apprentice to the Environment - Hunter- Gatherers and Landscape Learning.” In Archaeology and Apprenticeship - Body Knowledge, Identity, and Communities of Practice, edited by W. Wendrich, 99–118. Tuscon: The University of Tuscon Press.

- Rockman, M., and J. Steele. 2003. Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes: The Archaeology of Adaptation. London: Routledge.

- Roebroeks, W. 2003. “Landscape Learning and the Earliest Peopling of Europe.” In Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes: The Archaeology of Adaptation, edited by M. Rockman, and J. Steele, 99–115. London: Routledge.

- Roebroeks, W. 2006. “The Human Colonisation of Europe: Where are we?” Journal of Quaternary Science 21 (5): 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1044.

- Rots, V., and H. Plisson. 2014. “Projectiles and the Abuse of the use-Wear Method in a Search for Impact.” Journal of Archaeological Science 48: 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2013.10.027.

- Rust, A. 1937. Das Altsteinzeitliche Rentierjägerlager Meiendorf. Neumünster: Karl Wachholtz Verlag GmbH.

- Rust, A. 1958. Die Jungpaläolithischen Zelt-Anlagen von Ahrensburg. Neumünster: Karl Wachholtz Verlag GmbH.

- Salomonsson, B. 1964. “Découverte D’une Habitation du Tardi-Glaciaire à Segebro, Scanie, Suède.” Acta Archaeologica 35 (1): 1–28.

- Scheer, A. 1986. “Ein Nachweis Absoluter Gleichzeitigkeit von Paläolithischen Stationen.” Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 16: 383–391.

- Shea, J. J. 2006. “The Origins of Lithic Projectile Point Technology: Evidence from Africa, the Levant, and Europe.” Journal of Archaeological Science 33: 823–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.10.015.