ABSTRACT

The origin and dissemination of paired horse burials and the implications of adopting wheeled vehicle technology on Bronze Age European societies has not been extensively studied. To address this, we present the chronological, artifactual, DNA, contextual, and zooarchaeological analytical results from a Bronze Age double-horse burial in a barrow from Husiatyn, Podolia Upland, western Ukraine. The burial was radiocarbon dated to the 15th century b.c., and the preserved antler bridle elements are stylistically similar to those from the Carpathian-Danube area. The coat color of the Husiatyn horses was determined from ancient DNA analysis, and their arrangement facing each other, combined with little evidence of lesions on their bones and teeth, suggest they were well treated and probably ridden and/or harnessed to a chariot/cart. We argue that Middle Bronze Age Trzciniec Circle communities northeast of the Carpathians adopted the chariot package as a useful component of their elaborate funerary rituals.

Introduction

Horses buried wearing harnesses are among the most spectacular archaeological funerary finds from the Bronze Age. Dating to 2100/2000–1400/1300 b.c., such burials have been recorded in several modern Eurasian countries (Przybyła Citation2020). The burials vary greatly and can include from one to nearly twenty individuals. These are often funerary deposits containing specific skeletal elements of horses, such as skulls or arrangements of crania and lower limbs (head-and-hoof deposits; see Anthony Citation2007). However, the burial of two complete horses—identified archaeologically from their well or partially preserved skeletons—was the most specific interment method for these animals in the Bronze Age. This special arrangement of burying paired horses in graves was recurrent at that time and represents a sui generis posthumous metaphor of their role pulling a light vehicle with spoked wheels (i.e., a chariot) when alive. The conviction that Bronze Age horses could have been used for these purposes is reinforced by observations of lesions on their bones and teeth (e.g., Kosintsev Citation2010, 55). Moreover, if the remains of such vehicles are found as a component of harnessed double-horse burials, we can speak of a full chariot package or horse-chariot complex (Kristiansen and Larsson Citation2005; Kuprianova et al. Citation2017; Maran Citation2020).

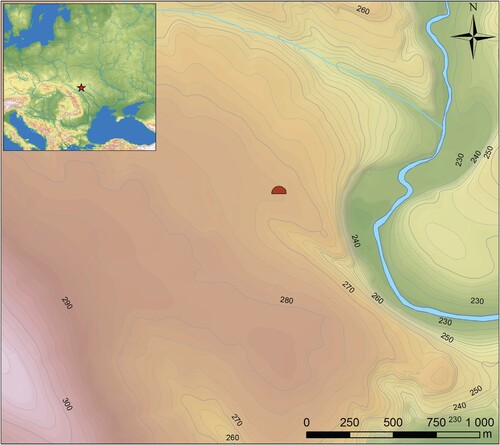

This article presents and interprets the results of studies and specialist analyses of an extraordinary late Middle Bronze Age burial of two horses deposited with a harness in a barrow grave in Husiatyn, Podolia Upland, western Ukraine (). This is one of the richest horse burials north of the Carpathian arc from that time. It serves as the point of departure for a discussion of paired horse burials in Eurasia and the dissemination of the chariot package throughout Europe. Specifically, the article first presents the archaeological context of the find, followed by the burial characteristics and the zooarchaeological descriptions of both animals. This includes their sex, age, height at withers, and color, as well as dental and skeletal pathological conditions and use-wear patterns that may shed light on the way they were used by Bronze Age communities. A detailed description of two unique horse harnesses from the Husiatyn deposit—comprised of both antler head gear toggles (cheekpieces) and knobs that were elements of a bridle—forms the basis for a typological analysis of these harness elements, a comparison with existing analogies, and an assessment of the cultural affiliation of the burial. Its chronology is more precisely situated through several modeled radiocarbon (14C) dates obtained from both and another measurement made on wood charcoal from the grave fill.

Figure 1. Location of the site in Husiatyn, western Ukraine (red star), and Digital Elevation Model of the barrow surroundings (barrow indicated by the red half circle) (drawing: J. Niebieszczański).

The discussion section addresses the question of the origins and dissemination of the custom of paired horse burials and argues that it first appeared in south Ural and the Kazakh steppes, from which it spread via the middle Volga drainage basin to Central-Eastern Europe and Greece. The potential mechanisms of this transmission are then presented in an interpretive model, making use of Fernand Braudel’s (Citation1992) universal concept of hierarchized space and the mechanisms of the dissemination of innovations over a long period of time (long durée). Furthermore, the meaning and symbolism of such a horse arrangement, its connection to the chariot package and—alternatively—cart transport are touched upon, as is the question of potential chariot functions in this geographic region. Consideration is also given to the social implications of introducing this innovation to Middle Bronze Age communities northeast of the Carpathians who were located beyond Europe’s major cultural development centers. In this context, attention is given to the emerging question of the relationship between the chariot package and local social elites. Here, we offer further evidence (Makarowicz et al. Citation2021) that these were not warrior elites but were instead members of dominant lineages that formed a collectivist rather than an individualized social structure of population groups in this part of the continent.

The Barrow and Double-Horse Burial

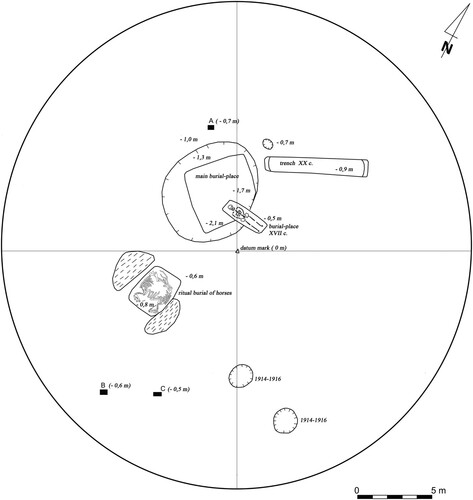

A round barrow was discovered in a field close to Husiatyn, Ternopil District, Ukraine (Ilchyshyn Citation2016). The barrow was located on a high plateau surrounded by the steep right bank of the Zbruch River, a left-bank tributary of the Dniester, to the northeast. Its mound has been largely levelled off by deep ploughing in modern times. The barrow resembled a flat oval elevation measuring 40 × 30 m (length × width) and 0.6 m in height. When exploring the barrow, several small human bone fragments and uncharacteristic pottery sherds tempered with burnt flint and granite were recorded, and an iron arrow point from early Scythian times (7th–early 6th century b.c.) was found at the foot of the southeastern sector of the mound at a depth of 0.5 m. Northwest of the center of the monument, a large trench was observed that destroyed the main feature beneath the barrow. In the backfill, a 17th century a.d. grave was dug. In addition, the barrow was found to have traces of trenches from World War II and later times ().

Figure 2. Plan of the barrow in Husiatyn. A) Human bones; B) iron arrowhead; and, C) pottery fragments.

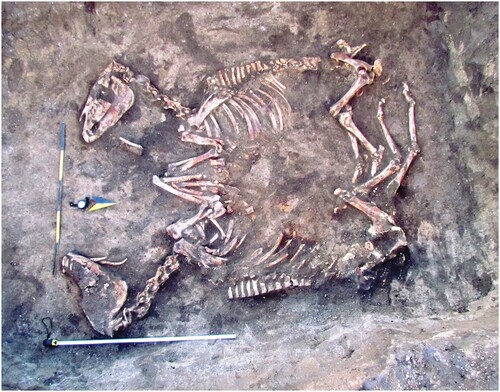

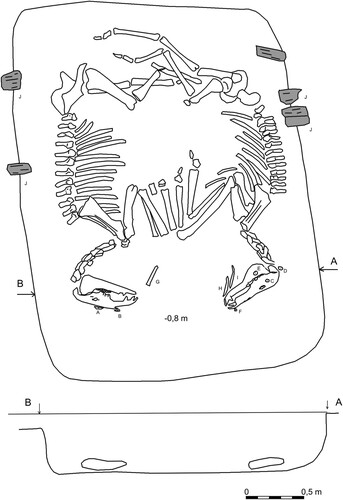

In the southwestern barrow sector, 5 m from its center and at a depth of 0.6 m below the modern ground level, a grave was unearthed that bore traces of a wooden cover made of oak.Footnote1 The grave resembled a rectangle measuring 3.4 × 2.4 m with its longer axis extending north–south. The chamber walls were straight and extended 0.4 m below the level of distinction (). On the northeastern and southwestern sides of the grave pit, two large oval-shaped clay clusters were recorded and were found to be identical to the clay of the bedrock beneath the barrow. At the bottom on the grave, two horse skeletons lay on their sides oriented along the north-south axis with their heads pointing south (see , ). They were arranged with their backs to the longer grave chamber walls and their heads facing each other. Their forelimbs were bent and touched each other, while the hind limbs were interlaced. Fragments of coccygeal vertebrae cartilage were found between the hind limbs on the ventral sides of their trunks. This suggests that the tails were intentionally bent downwards towards their underbellies during burial (Ilchyshyn Citation2016).

Figure 3. Grave and burial of horses from the Husiatyn barrow, including the locations of round antler knobs (A–F), rod antler cheekpieces (G–I), and remnants of wooden cover (J). An antler knob located below E is not visible in this view.

Horse 1 (western)

The age and sex of both horses were determined based on the completely preserved incisors and canine teeth in the upper (maxillary) and lower (mandibular) dental arches. The presence of large, fully developed canine teeth testifies to the male sex of Horse 1. When judged by the shape of the occlusal surface and the degree of infundibulum wear on the maxillary incisors (I1, I2, and I3), the age of the animal was estimated to be about 13–14 years at death, while the mandibular incisors (I1, I2, and I3) indicated 14–15 years. The degree of proportional wear on these teeth attests to the absence of any major malocclusion.

Regular fine flutes were observed on the enamel ledges on the labial surface of the I1s. The right canines (RC1 and RC1) were clearly worn on the occlusal surface when compared to their counterparts on the left side (LC1 and LC1). The maxillary and mandibular premolars (P1, P2, and P3 and P1, P2, and P3, respectively) exhibited traces left by the working elements of a bit, showing how the horse was used. Initial cemental hypoplasia of the rostral and distal infundibula was also observed (Kopke, Angrisani, and Staszyk Citation2012; Staszyk, Suske, and Pöschke Citation2015; Suske et al. Citation2016; Dixon Citation2017), accompanied by the slight exposure of enamel ledges on the buccal surface and the absence of any wear on the rostral side of the right P2 crown. In the case of the right P2, similar slight exposure of enamel ledges on the lingual side and fine traces of rostrally exposed enamel attest to the possibility that the horse had worn a bit, indicating it had been used for riding or as a draught animal (Bendrey Citation2007).

The occlusal surface of the premolars was characteristic for normal wear. Thus, it can be claimed that this horse did not suffer from frequent bit chewing or excessive anxiety (Dietz and Huskamp Citation2005). The right and left third molars (M3) had only minor damage to the tooth infundibulum and showed only slight exposure of enamel ledges on the lingual surface. Simply put, the horse did not show any typical dental lesions or caries, signs of periodontitis, malocclusion, or malfunctioning of the temporomandibular apparatus (Pasicka, Onar, and Dixon Citation2017). The only defect it suffered from was the incidental initial phase of cemental hypoplasia. The state and general appearance of its teeth, therefore, supports the conclusion that the animal was properly handled and occasionally ridden or used as a draught animal but was not excessively exploited.

Due to poor bone preservation, only a few specimens could be osteometrically analyzed. In the case of Horse 1, the following bones were measured according to Driesch (Citation1976): humerus, radius, femur, both (right and left) tibiae, and the proximal and distal phalanges. Based on the greatest length of the long bones, the height at the withers was calculated according to the methods of Vitt (Citation1952) and May (Citation1985). Horse 1 measured 134–138 cm at the withers, with an average value of 136 cm. According to Vitt's classification (Citation1952), the individual was classified as medium-sized (136–144 cm). For aDNA analysis, a petrosal bone was selected (sample EQ_Husia_01). The obtained data (EQ_145) suggests a chestnut color, which was common in the Bronze Age horse population in Eurasia (e.g., Ludwig et al. Citation2009; Wutke et al. Citation2016, 2; Librado et al. Citation2021).

Horse 2 (eastern)

Horse 2 was a male individual, based on its large, fully developed canine teeth. The shape of the occlusal surface and the degree of incisor infundibulum wear indicates its age was about 15–16 years at death.

A complete set of maxillary and mandibular incisors was identified. Unusual for archaeozoological materials, changes in maxillary teeth were observed especially on the right and left I1 and I2. On their labial surfaces, the dental tissue was worn down in a sinuous manner. This could have been the result of the extended, regular, and intentional feeding of the horse from a feedbag; the teeth could have been characteristically worn down via friction caused by regular contact with the feedbag surface. The left and right I1 and I2 bore similar but far more delicate flutes on their labial surfaces. The left and right C1 and a C1 were worn down; however, the oblique wear of the right C1 differed from its counterpart on the left side.

Upon close examination, the premolars of Horse 2 exhibited initial cemental hypoplasia of the rostral and distal infundibula of the right P2, slight exposure of enamel ledges on the buccal surface, and the absence of wear on the rostral side of the crown. As with Horse 1, the right and left P2 exhibited slightly exposed enamel ledges on the lingual surface and a trace of rostrally exposed enamel that was stronger on the left side, testifying to the use of a bit. Both left and right M3 displayed only slightly exposed enamel ledges on their lingual surfaces. The general appearance of the occlusal surfaces of these teeth attest to the animal's good health, absence of malocclusion, and to its decent handling.

As in the case of Horse 1, poor bone preservation allowed the measurement of only a few skeletal elements. They were as follows: one metacarpal III, two metatarsal III bones (left and right), and the proximal and distal phalanges. Height at the withers, calculated from the metapodial elements according to Vitt’s (Citation1952) method, was 148.2–154.6 cm, with an average value of 151.7 cm. Horse 2, according to Vitt’s (Citation1952) size classification, was therefore taller than medium-sized individuals (144–152 cm) and fell within the lower range for tall horses (152–160 cm). The measured bones showed such lesions as the fusion of the metacarpal II and III shafts and small osteophytes around the proximal end of metatarsal III. Moreover, a considerable accretion of bone tissue was noted on the shaft of a proximal phalanx that could have been caused by the excessive pressure of palmar ligaments.

For aDNA analysis, a petrosal bone was selected (sample EQ_Husia_02). The obtained data (EQ_146) suggests a bay or very dark to black color, conspicuous in the early stage of horse domestication in Eurasia (see Ludwig et al. Citation2009; Wutke et al. Citation2016; Librado et al. Citation2021).

The horses’ bodies were carefully placed on their sides in a mirror-image position. The autopodial segments of the forelimbs were drawn up, while the hind limbs were extended. The examination of their bones and teeth shows that the role and position of these horses were not equivalent. The traces left on the incisors of Horse 2 suggested that it had been particularly important and enjoyed its masters’ special favor. Furthermore, after death, its hind limbs came to rest on top of the limbs of Horse 1; this may illustrate its dominant role in the team. The superiority of Horse 2 most likely followed from the fact that it was clearly sturdier than Horse 1—it was taller by almost 15 cm.

Horse gear

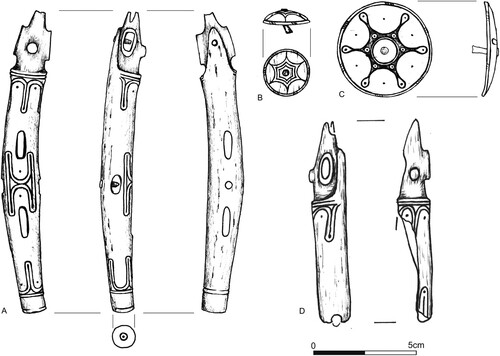

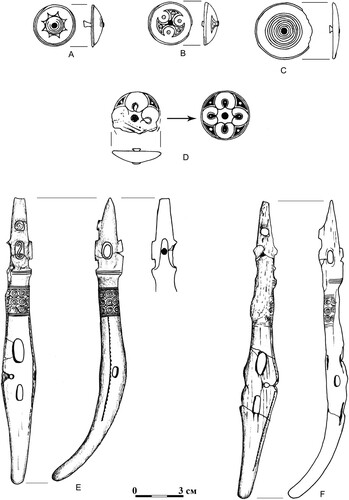

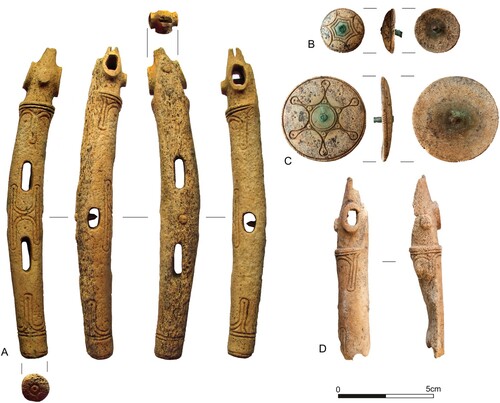

Both horse inhumations included elements of head gear (i.e., a harness). Specifically, the side elements of a bit (i.e., rod or rod-shaped toggles [cheekpieces] made of deer antler with bi-plane perforations for harness straps) and antler knobs with bronze rivets that fastened them to leather straps were functional-ornamental head gear elements (Ilchyshyn Citation2016).

An antler rod cheekpiece lay 12 cm east of the mandible of Horse 1 (western) and 10 cm to the north of its skull (G). It is 14.8 cm long and slightly crescentic in shape, while its cross-section is circular with a maximum diameter of 1.5 cm (A, A). A second partially preserved cheekpiece was not identified during initial excavations because it lay beneath the horse’s head (D, D). Its lower portion has broken off, causing its remaining length to be 9.1 cm, while its maximum diameter reaches 1.5 cm (for a detailed description, see Supplemental Material 1). Lying on Horse 1’s skull, a round antler knob with a lenticular cross-section was found, and another was found close to the nostrils (A, B) (see Supplemental Material 1).

Figure 5. Photo of the gear of Horse 1, including A, D) antler rod cheekpieces and B–C) round antler knobs.

Horse 2 (eastern) was accompanied by a richer inventory (, ). Two almost identical antler rod cheekpieces lay parallel to each other, almost touching the horse's mandible (H–I, ). In both cases, the lower portion of the rod is bent and rounded, while the surfaces of both are partially damaged. They measure 18 cm and 18.4 cm in length, respectively, and are oval in cross-section, with diameters in the middle portion that measure 2.3 × 1.6 cm (see Supplemental Material 1). On top of Horse 2’s skull, five antler knobs were found, of which one is only partially preserved (C–F, ; Ilchyshyn Citation2016, photo 1). The first lay next to the frontal bone, the second knob was next to the occipital bone (between the ears), the third rested below the canine teeth in the back of the mandible, as did the fifth on the opposite side, while the fourth was found next to the nostrils (C–F) (see Supplemental Material 1).

Figure 7. Photo of the gear from Horse 2, including A–B) antler rod cheekpieces and C–F) round antler knobs.

The alloy composition of the metal bolt rivets used to fasten the antler knobs was also analytically determined.Footnote2 The corroded surfaces were first cleaned, and the alloy compositions were measured using an Elva X fluorescent X-ray spectrometer. The results showed that the bolts from Knob A from Horse 1 and Knobs C and D from Horse 2 were made of low-tin-content bronze (Sn from 1.141–4.54%). The even lower tin content of three other knobs (Horse 1, nos. A and B, and Horse 2, no. E) was between 0.630 and 0.718%, which actually corresponds to the limit of artificial precipitation; Knob B from Horse 2 had only a trace impurity of tin (0.58%). Generally, when all components and their frequencies (see Supplemental Material 2) are considered, it can be claimed that the copper probably came from one deposit and that the bolt rivets were made in a single metallurgical workshop.

Burial Chronology

For determining the relative chronology and origins of the Husiatyn double-horse burial, typological classification of the preserved bridle elements, such as the antler cheekpieces and knobs with bronze rivets, is crucial. The cheekpieces found with both horses represent the Spiš type (Vladár Citation1971, 8; Hüttel Citation1981, 82–94, pls. 8–9); the specimens found with Horse 1 are sometimes also classified as the Borjas type (Mozsolics Citation1953, 95–97). According to Nicolaus Boroffka (Citation1998, 100–102), they can be classified as Type IVb. Generally speaking, rod-shaped cheekpieces (Stangenknebel) are stylistically related to those from the Carpathian Basin (Hüttel Citation1981; Boroffka Citation1998; Kristiansen and Larsson Citation2005; Przybyła Citation2020; Lindner Citation2021, 48; Metzner-Nebelsick Citation2021, 114) and occur towards the end of the Early and into the Middle Bronze Ages, specifically in Early Danubian (Frühe Danubische; FD) III–Middle Danubian (Mittlere Danubische; MD) III, according to B. Hänsel, or Bronze A2–Bronze D, according to P. Reinecke (Harding Citation2000, fig. 1.3; Gogâltan Citation2008; see Hüttel Citation1981, pls. 26, 46), or roughly 1700–1350/1300 b.c. Significantly, the Spiš type was in use the longest (Boroffka Citation1998, 103ff.; Harding Citation2000, table 1.3; Przybyła Citation2020, 33ff.). It must be stressed, however, that none of the Husiatyn specimens are closely analogous to existing types in either form or ornamentation.

The particular ornamentation motifs found on the Husiatyn cheekpieces are encountered not only on specimens belonging to the Spiš type and its variants but also on other types. The motif of a half oval on a cheekpiece body or head occurs on specimens from Jakuszowice in Poland, Østerup Bymark and Sealand in Denmark, and Waldi bei Toss in Switzerland (Hüttel Citation1981, pl. 11:110, 111; Bąk Citation1992, fig. 2:2; Vandkilde Citation2014, 617, fig. 7). The ornament of a single circle containing a central point located on a cheekpiece head is found, for instance, on specimens from Belz, Ukraine (Hüttel Citation1981, pl. 8:70) and Morawianki, Poland (Przybyła Citation2020, figs. 1, 2). In turn, the motif of tiny “hanging triangles” arranged horizontally and vertically alone or with other motifs is found on cheekpieces of the Spiš type from Gîrbovăţ, Romania, the Tószeg type from Hungary (Hüttel Citation1981, pl. 8:74, 76), the Füzesabony type from Nitrianský Hrádok, Slovakia (Hüttel Citation1981, pl. 5:39), the Köröstarcsa and Mezöcsát-Pástidomb types from Hungary (Mozsolics Citation1953, fig. 14; Hüttel Citation1981, pl. 6:52, 53; see Przybyła Citation2020, 26), and on Noua culture specimens from Bovshiv and Ostrivets, Ukraine (Krushenitska Citation2006, fig. 49:23–24). Furthermore, motifs similar to bands filled with a concentric circle motif from Husiatyn are also found on a Füzesabony type cheekpiece from Százhalombattta-Földvar (Kovács Citation1969, 159ff., Hüttel Citation1981, pl. 10:102) and those from Tószeg in Hungary (Mozsolics Citation1953, fig. 12) and Včelince in Slovakia (Furmánek and Marková Citation2008, fig. 16). They also occur on other artifacts, including, for instance, gold ones from Shaft Grave III in Mycenae (David Citation2007, pl. CVf) or antler ones from the inventories of the Mad’arovce culture from Malé Kosihy (Bátora Citation2018, fig. 160:1).

The Husiatyn antler knobs are closely analogous, formally and spatially, only to specimens from a double-horse burial in a barrow grave from Mezhirich, Volhynia, Ukraine. It yielded antler knobs with metal rivets with the same or similar ornaments (Pankovskiy Citation2020, fig. 21:1–6). Their counterparts found at other sites, especially in the Carpathian-Danube region, are not exact matches in terms of form or ornamentation. They lack bronze bolt rivets and instead have eyelets or central perforations and come from the fortified settlements of the classic and late phases of the Otomani-Füzesabony culture in Otomani, Romania (Ordentlich Citation1963, fig. 9:11; Chidioşan Citation1984, fig. 11:6; Daróczi Citation2018, pl. 17:6) and Nižnja Myšla, Slovakia (Olexa and Pitorák Citation2004, fig. 1:5), the Mad’arovce culture in Nitriansky Hrádok (Bátora Citation2018, fig. 159:3), and the settlements of the Vatin (Daróczi Citation2018, pl. 17:3–5), Monteoru (late phase?) and Noua (Phase I) cultures located between the Prut River and the Eastern Carpathians in, for instance, Bărboasa, Gâîrbovăţ, Cândeşti, Dumeşti, and Andrieşeni (Florescu and Florescu Citation1990, fig. 34:4; Florescu Citation1991, fig. 153:1–3; Diaconu and Sîbru Citation2014, figs. 1, 2). Unornamented knobs with eyelets were also found in a barrow grave in Morawianki, Małopolska, Poland (Przybyła Citation2020, fig. 3:3, 4).

Generally, the geometric and convoluted motifs recorded on the Husiatyn cheekpieces and knobs are variants of an ornamentation known as the Carpathian–eastern Mediterranean Wave Band Decoration (Karpatenländisch ostmediterrane Wellenbandornamentik) that is also found on artifacts unconnected with horse harnesses (David Citation1997, pl. 5:1, 2; Citation2007, figs. CIII–CV) in the 18th/17th–15th centuries b.c. (David Citation2007, 415). This decoration is characteristic of many Carpathian-Danube cultures (Mad’arovce-Věteřov-Boheimkirchen, Vatya, Mureş, Vatin, Hatvan, Otomani-Füzesabony, Wietenberg, Monteoru, and Noua) and also appears in Mycenaean Greece on the Peloponnese, in Anatolia, and in the Levant (David Citation2007, 412–413; Maran and van de Moortel Citation2014). Single occurrences of this motif are also found far from this region (for more, see Przybyła Citation2020, 26), on the eastern European steppes, for instance, where decorations are similar, but slightly different (Penner Citation1998, figs. 2, 5; Harding Citation2005, 298).

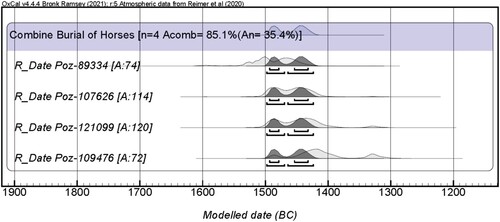

To determine the absolute chronology of the double-horse burial from Husiatyn, three 14C age determinations (AMS) were obtained from the teeth of both individuals. Additionally, the age of a piece of wood charcoal from the bottom portion of the grave fill was determined (). The body arrangement, context, and what is known to date about paired horse burials suggest that both individuals were simultaneously deposited in the grave during a single ritual act. This is supported by the similar age intervals calibrated for single 14C determinations using the OxCal 4.4.4. software (Bronk Ramsey Citation2009) and the date obtained for the charcoal. All individual determinations after calibration indicate, at the 2σ confidence interval, a period from the second half of the 16th century cal. b.c. to nearly the end of the 14th century cal. b.c. (see ). At the 1σ probability level, the Husiatyn horse burial should be situated within the 15th century cal. b.c. The Combine function was applied to two radiocarbon determinations for Horse 2, narrowing the time of its death and deposition in the grave to 1506–1433 cal. b.c. (95.4%), with this most certainly happening in the interval of 1484–1449 cal. b.c. (53.3%). The contemporality of the funerary episode, wherein the animals were simultaneously buried, allowed the same method of joint calibration to be applied to all of the 14C determinations. As a result, the time intervals of 1498–1424 cal b.c. (95.4%) and 1494–1433 cal b.c. (68.3%) were obtained with a goodness of fit (Acomb) of 85.1% (Bronk Ramsey Citation2009) (). Thus, it can be very credibly claimed that the horse burial took place in the 15th century b.c., possibly in its first half.

Table 1. 14C ages of samples collected from the double horse barrow grave in Husiatyn. The dates were calibrated with OxCal 4.4.4. (Bronk Ramsey Citation2009) using the IntCal 2020 curve (Reimer et al. Citation2020).

The generated dates are consistent with, or slightly later than, other 14C determinations obtained from archaeological horse bones deposited in similar “team arrangements” in sites northeast and east of the Carpathians () in such locations as Morawianki (3360 ± 70 b.p.; Przybyła Citation2020, 34) and Negrilești (3258 ± 68 b.p.; Bălășescu et al. Citation2018–2019, 11). Other contemporaneous double-horse burials include those with unpublished dates from sites in Poland, including Michałowice (3260 ± 35 b.p. and 3280 ± 30 b.p.), Dębiany (3270 ± 35 b.p.; M. M. Przybyła, personal communication 2022), and Kazimierza Wielka, where several horses were recorded (3215 ± 35 b.p., K. Tunia, personal communication 2022).

Figure 11. Dispersion of double-horse burials (complete skeletons only) ca. 2000–1400/1300 b.c., with Husiatyn indicated in red: 1) Morawianki, 2) Żerniki Górne, 3) Miernów, 4) Michałowice, 5) Gabułtów, 6) Kazimierza Wielka, 7) Wilczyce, 8) Bukivna, 9) Miluvannya, 10) Husiatyn, 11) Mezhirich, 12) Oarta de Sus, 13) Marathon, 14) Dendra, 15) Kokla, 16) Utyovka, 17) Krivoe Ozero, 18) Potapovskiy, 19) Sintashta, 20) Ozerny, 21) Tabyldy, 22) Novoilinovskiy, 23) Berlik II, 24) Novonikolovskiy, 25) Krasnogorskoe, 26) Ayapbergen, 27) Maytan, 28) Naberezhno-Chelninskiy, 29) Pesochnoe, 30) Kalinovka, 31) Khvorostyanka, 32) Novye Kliuchki III, 33) Komarovka, 34) Barannikovo, 35) Novousmanskiy, 36) Stepnoe VII, 37) Bestmak, 38) Khripunovskiy, 39) Nurtay, 40) Uvarovskiy II, 41) Negrileşti, 42) Ripiceni, and 43) Dębiany. According to: El Susi and Burtănescu Citation2000; Kuznetsov Citation2006; Kosintsev Citation2010; Makarowicz Citation2010; Kuprianova and Zdanovich Citation2015; Bălășescu et al. Citation2018–2019; Recht Citation2018; Krause et al. Citation2019; Kukushkin and Dmitriev Citation2019; Chechushkov, Usmanov, and Kosintsev Citation2020; Pankovskiy Citation2020; Przybyła Citation2020 (drawing: J. Niebieszczański).

Discussion

Despite their joint and simultaneous burial, the horses from Husiatyn presumably did not die at the same moment. They were buried after the natural or accidental death of one, and the second was then buried with its companion. It must be stressed that Horse 2 from Husiatyn belonged to the largest breed of Bronze Age horses in Eurasia. Its height at the withers was greater than that of Early and Middle Bronze Age horses in the Carpathian Basin and matched that of Roman period horses (Klecel and Martyniuk Citation2021, 7; Kanne Citation2022, fig. 7). Conversely, Horse 1 is comparable in this respect with horses from the same period (Noua culture) from such locations as Ripiceni and Negrilești in Romania (El Susi and Burtănescu Citation2000; Bălășescu et al. Citation2018–2019) and Middle Bronze Age specimens from modern Hungary (Kanne Citation2022, fig. 7). The unusual character of Horse 2 was highlighted by its exceptionally prestigious harness. Meanwhile, although Horse 1 was much smaller, it did not differ from typical horses of that age in terms of harness paraphernalia. Its harness was slightly more modest than that of Horse 2, but also spectacular.

Horses buried in single, double, or collective graves in various periods usually were arranged in a ventral-dorsal position (Świeżyński Citation1972). In this case, the horses lay on their sides with heads facing each other. When alive, a horse assumes such a lateral body position when asleep, specifically during the fourth phase of sleep, or REM, when muscle atonia sets in and the horse relaxes (Miyazaki, Liu, and Hayashi Citation2017). Hence, their body arrangement also likely represents their masters’ care to symbolically ensure eternal and uninterrupted rest for their faithful service to man.

The symmetrical arrangement of paired horses in burials reflects not only funerary customs but also the positions of these animals in the lives of Middle and Late Bronze Age communities on the vast expanses of Eurasia. In double burials, horses are usually arranged so that either their heads and limbs or backs face each other, and other arrangements are rare (Kosintsev Citation2010, 73–79; see Kosmetatou Citation1993; El Susi and Burtănescu Citation2000; Pappi and Isaakidou Citation2015; Recht Citation2018; Bălășescu et al. Citation2018–2019; Krause et al. Citation2019; Chechushkov, Usmanov, and Kosintsev Citation2020; Przybyła Citation2020, fig. 15; Metzner-Nebelsick Citation2021). Partially disarticulated horse burials are found, as well. They usually take the form of buried heads and hooves or only skulls with cheekpieces and are, in all likelihood, symbolic representations of animals harnessed to a chariot (Gening, Zdanovich, and Gening Citation1992; Kuznetsov Citation2006; Anthony Citation2007; Kosintsev Citation2010; Kuprianova et al. Citation2017; Chechushkov and Epimakhov Citation2018; Chechushkov, Usmanov, and Kosintsev Citation2020). It must, however, be stressed that the custom of depositing horse heads and hooves emerged in the steppes much earlier, probably during the initial stage of their domestication (Anthony Citation2007, 189; Anthony and Brown Citation2011, 138).

From 2100/2000–1400/1300 b.c., paired burials of complete horses were interred in several centers, from the Kazakh steppes in central Asia in the east to as far as the Małopolska Upland in the west and the Peloponnese to the south (see ). The earliest are connected to the Sintashta-Petrovka cultural complex in the southern Ural area, while later ones are associated with various other steppe and forest-steppe groups, such as the Andronovo, Potapovka, Alakul, and Srubnaya cultures, situated roughly between the upper Ishim River in central Kazakhstan and the middle Volga River (Kosintsev Citation2010, 73–79; see Hanks, Epimakhov, and Renfrew Citation2007; Lindner Citation2020). In the late 17th and early 16th centuries b.c., this practice emerged almost simultaneously among the Trzciniec Cultural Circle (TCC) in present-day southern Poland and southwestern Ukraine (Przybyła Citation2020, 34), the Noua Culture on the Prut River in today’s Romania (El Susi and Burtănescu Citation2000; Bălășescu et al. Citation2018–2019), and Mycenaean Greece (Drews Citation1993, 106; Maran Citation2020, 506). Hence, the chronology of such finds suggests that the custom in question spread west and southwest from the east over several hundred years. Interestingly, although the Carpathian Basin is a sui generis stylistic center of rod cheekpieces, with the earliest dating to the end of the Early Bronze Age (FD III) slightly before 1800 b.c. (Boroffka Citation1998, 116ff.; Pankau and Krause Citation2017, 361; Daróczi Citation2018; Przybyła Citation2020; see Fischl et al. Citation2015), only a single double- horse burial has been found in this region (see ). What poses a problem in this case is the absence of absolute dates from this area for specific rod cheekpieces beyond their broad cultural (layer) contexts. In addition to elongated (rod) ones, less common steppe disk-like cheekpieces are also found in the Carpathian Basin. Meanwhile, Carpathian cheekpieces are encountered in the steppe zone, which may indicate extensive contacts/interactions among communities from both regions (Kristiansen and Larsson Citation2005, 170–186, fig. 79; Maran Citation2020; Kanne Citation2022).

Burials containing the preserved skeletons of two horses with or without bridle elements are not found between the Don and Dnieper Rivers, or even—more broadly—between the Volga and Boh Rivers (one case only—see ). In the steppe zone, and almost as a rule north and east of the Carpathians, paired horse burials are recorded chiefly in barrows, often in their southwestern or southeastern sectors (Kosintsev Citation2010, 73–79; Przybyła Citation2020).

Concentrations of paired horse burials both with and without bridle elements visible in attest to the general direction of the dissemination of this custom. It spread over 4000 km from the east to the west and southwest within a period of six to seven centuries. Certain spatial discontinuities in this spread, and consequently in the dissemination of chariots/carts, can be explained by either a dearth in the state of research (which is rather implausible) or an actual tendency toward such concentrations of this innovation which was so important in the lives of Bronze Age communities.

Referring to the Braudelian concept of hierarchization of all societal spaces (i.e., cultural, economic, and political) and the distinction of central, peripheral, and marginal areas (Braudel Citation1992), one may assume that specific cultural patterns, including technological innovations and prestige objects, spread haphazardly like the movement of a knight on a chessboard rather than gradually and relatively evenly, as does a wave or ripple on water. The transmission, adaptation, or creative incorporation of such patterns, innovations, or inventions is possible only where there is a specific demand for them, the ground has been laid to receive them, and natural conditions are conducive to the rise of a network of interregional contacts that may foster their local or regional adaptation (Kadrow Citation2001; Makarowicz Citation2009, Citation2012, Citation2015). It appears that this mechanism for the propagation of specific cultural patterns and innovations can also be applied to the dissemination of the idea of a chariot drawn by a pair of horses over such long distances far from the Eurasian steppe where the concept originated. In the opinion of the present authors, the prime mover behind this spread could have been the aspirations of local Central-Eastern European elites.

In addition to ritual horse burials recovered from barrow graves, many deposits of post-consumption horse bones have been recorded in Central-Eastern European settlements and domestic/economic features dating to the end of the first half and the beginning of the second half of the 2nd millennium b.c., especially within the TCC oecumene (Makarowicz Citation2010; Górski Citation2017; Przybyła Citation2020). This shows how diversified attitudes toward horses were among the populations that settled this part of Europe. “Ritual” horses must have formed a separate group of selected animals that people diligently cared for (e.g., Horse 2 from Husiatyn likely ate from a feedbag) and treated with respect even after their deaths (e.g., spectacular harnesses were included in the Husiatyn double-horse burial that reflected their status when alive). They also lived to an advanced age of about 15 years. In some known cases, Middle Bronze Age draught horses reached an age of 20 years; frequently, these were stallions (e.g., El Susi and Burtănescu Citation2000; Bălășescu et al. Citation2018–2019; see Kanne Citation2022). It appears that the Husiatyn individuals can be considered extraordinary horses that were assigned to exclusively (or nearly exclusively) perform specific tasks connected to crucial spheres of social life within a community; they were not reared for slaughter but were used in ritual activities. Perhaps owing to their individual character traits tested during training (e.g., intelligence and the quick and easy ability to learn commands) and/or their physical and motor characteristics (e.g., size, suitable color, endurance, etc.), these horses became important participant-actors and co-creators of specific actions and events. As such, they were constitutive elements of the lifestyle of some communities living north and northeast of the Carpathians. Since only some of these horses were buried with harnesses, it may be presumed that a hierarchy was present in this animal category, as well.

In our opinion, the rise of the custom of burying paired horses wearing harnesses in Central-Eastern Europe, especially north and northeast of the Carpathian arc, may be connected to long-distance interactions among TCC communities, especially between local barrow elites (including Komarów culture representatives) and Srubnaya culture communities from the Volga-Don steppes on the one hand and societies of the Middle Bronze Age cultures from the Carpathian Basin and its eastern surroundings (Otomani-Füzesabony, Mad’arovce, Monteoru, Sabatinovka, and Noua) on the other (Sulimirski Citation1968; Gancarski Citation2002; Makarowicz Citation2009, Citation2012, Citation2015; Makarowicz, Górski, and Lysenko Citation2013; Makarowicz et al. Citation2016, Citation2019; Górski Citation2017).

In Bronze Age studies, a dominating view is that paired horses buried with harness elements—of which usually only antler cheekpieces typically survive—reflect the use of horses for pulling chariots. This view is supported by the finds of chariots and their elements or impressions of spoked wheels, with those from the Ural-Kazakh steppes being the earliest (Boroffka Citation1998; Anthony Citation2007; Chechushkov and Epimakhov Citation2018; Lindner Citation2020). Some authors believe that chariots simultaneously appeared in three zones: 1) the steppes between south Ural and central Kazakhstan, 2) the Middle East, and 3) the Carpathian Basin and the lower Danube (Burmeister and Raulwing Citation2012, 100ff.; see Pankau and Krause Citation2017; Maran Citation2020, 506). Moreover, it is stressed that particular elements of the chariot package may have originated in various locations (Maran Citation2020). Representations of chariots drawn by horses are found in the rock art of central Asia (Novozhenov Citation2012) and Scandinavia (Johannsen Citation2011; Vandkilde Citation2014), and other iconographic images of such vehicles, with or without charioteers, are evident in Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean, including the Mycenaean civilization (Littauer Citation1972; Feldman and Sauvage Citation2010; Novozhenov Citation2012; Chondros et al. Citation2016; Maran Citation2020). It must be observed, however, that there are no direct discoveries of chariots, and iconographic evidence of these vehicles is meagre in the Carpathian Basin and the lands to the north. The earliest comes from the late portion of the Middle Bronze Age or the beginning of the Late Bronze Age (e.g., two terracotta chariot models from Dupljaja in Serbia, the representation of a chariot on a Suciu de Sus culture vessel from Vel’ke Raškovce in Slovakia, and a model from Pecica in Romania; Boroffka Citation2004, fig. 12; Daróczi Citation2018, 118ff.; Nicodemus Citation2018).

Although horse burials north and northeast of the Carpathians are not accompanied by vehicles, many are furnished with cheekpieces and other bridle elements. Thus, it cannot be ruled out that horses may also have been ridden at that time (see Kanne Citation2022). Horseback riding, as some authors hold, was practiced on the Volga-Ural steppes during the Eneolithic or even earlier (Anthony, Brown, and George Citation2006; Anthony Citation2007; Anthony and Brown Citation2014, 55–57; for a different view, see Kosintsev and Kuznetsov Citation2013; see also Levine Citation1999). However, whether horseback riding was a permanent or common practice at that early time is questioned. Arguments against it include the fact that the representations of people on horseback appeared several centuries later than those of horse-drawn chariots in the art of the Middle East, Egypt, and Mycenaean Greece, and that horse riding became popular only in the Iron Age (Littauer and Crouwel Citation1979; Drews Citation2004, 20, 40–55; Harding Citation2005; Kelder Citation2012). On the other hand, new data and well-supported arguments have recently been presented that early 2nd millennium b.c. communities both on the steppes (Chechushkov, Epimakhov, and Bersenev Citation2018; Chechushkov, Usmanov, and Kosintsev Citation2020) and in the Carpathian Basin (Kanne Citation2022) had horseback riding skills.

For the case at hand, the question is of little significance, because horseback riding is more likely associated with single horse burials, and possibly collective ones, rather than with animals deposited in pairs, particularly those interred in a symmetrical, team fashion. Naturally, it should not be ruled out that horses were used for both pulling chariots or carts—which is more likely (Dietz Citation1992; see Littauer and Crouwel Citation1979, 91; Brownrigg Citation2006)—and riding, especially as the harness elements found next to horse burials would have served both purposes well (Harding Citation2005, 296; Metzner-Nebelsick Citation2021). Perhaps rod-shaped bits were more useful for riding on horseback, while disc-shaped ones were preferred for driving chariot horses, as many authors believe (Drews Citation2004; Chechushkov, Usmanov, and Kosintsev Citation2020; Kanne Citation2022), although they could have been successfully used for both purposes. However, only rod-shaped bits occur in Carpathian paired horse burials, suggesting that they were originally used for chariot teams.

Regardless, the considerable number of harness elements, especially bridle cheekpieces, and horse burials from sites in Central-Eastern Europe dating to the 2nd millennium b.c. are a powerful argument for the dissemination of the chariot idea throughout this part of the continent. It was thought of as a light ritual-parade vehicle or possibly a combat one, fitted with spoked wheels. In light of previous analyses and interpretations and recent Bayesian modelling of 14C dates, precursive chariots were likely first used by Sintashta-Petrovka culture communities on the Ural-Volga steppes in the late 3rd and (more likely) early 2nd millennia b.c. (Kuznetsov Citation2006; Hanks et al. Citation2015; Lindner Citation2020, Citation2021), shortly before the “true” chariot emerged in the Middle East (Littauer and Crouwel Citation1979; see also another opinion in Pankau and Krause Citation2017, 356–360, fig. 2; Maran Citation2020).

The contexts of cheekpieces and other bridle elements in Central European sites provide very interesting information. Specifically, in the southern region of the Carpathian Basin, horse remains and artifacts are primarily found in settlement contexts (Hüttel Citation1981; Boroffka Citation1998, 88–94), while funerary finds are incidental (see ). In contrast, north and northeast of the Carpathians, such horse remains and related artifacts are recorded almost solely in sepulchral contexts. This suggests their strong connection to this sphere of ritual life and ceremonial-parade functions. Furthermore, paired horse burials in this part of Europe usually occur independently of their deceased human handlers (i.e., without the accompanying remains of their teamsters). Meanwhile, incidental human burials that include the remains of many horses are not furnished with weapons. This indirectly shows that such burials were not connected with warfare (see Górski Citation2017).

Horse remains from funerary contexts dominate in many other regions (Pankau and Krause Citation2017) and on the steppe, too, where chariots are believed to have been used in warfare and competitive racing (Chechushkov, Usmanov, and Kosintsev Citation2020). However, due to the specific parameters of steppe vehicles when compared to Mediterranean and Middle Eastern ones, such uses are sometimes questioned (Littauer and Crouwel Citation2002; Drews Citation2004). For example, chariots became commonly used in combat in Egypt and the Middle East only in the second half of the 2nd millennium b.c. (Littauer and Crouwel Citation2002). In this context, the advanced age of the horses from Husiatyn and other sites, assuming that they pulled a chariot, argues in favor of a non-combat function of this vehicle north and northeast of the Carpathians and perhaps in the Carpathian-Danube region, as well (Maran Citation2020). The near complete lack of chariot remains from Middle Bronze Age funeral contexts in the Carpathian Basin and its surroundings is curious, as is the dearth of spoked wheel impressions like those from Sintashta-Petrovka complex sites (Gening, Zdanovich, and Gening Citation1992; Kuprianova et al. Citation2017; Chechushkov and Epimakhov Citation2018), and models of such vehicles are extremely rare. However, cart clay models, usually present as ceramic vessels, are relatively numerous in Middle Bronze Age sites in the Carpathian Basin (Csányi and Tárnoki Citation1992, 424; Boroffka Citation2004; Bondár Citation2012; Molnár and Katócz Citation2019), as are solid clay wheels in fortified and tell settlements (Vladár Citation1973, fig. 80; Csányi and Tárnoki Citation1992, 205, 422–423; Gancarski Citation2011, fig. 185). The furthest-reaching interpretation of this phenomenon is the hypothesis that horses may have also been harnessed to parade-prestigious carts in this region. Owing to their design, these vehicles were used for ritual or parade purposes and not combat ones. One must not forget, however, the chariot models from Dupljaja and Pecica and the finds of four-spoked wheels, in addition to vehicle clay models of chariots, no doubt, in the settlements of the Mad’arovce culture at sites such as Blučina in the Czech Republic, Iža, Šurany-Nitriansky Hrádok (Vladár Citation1973, figs. 62:5, 81:1, 3; Bátora Citation2018, fig. 114:4, 5), Santovka-Mad’arovce, Vráble, and Rybník (J. Bátora, personal communication 2022) in Slovakia, and in Böheimkirchen in Austria (Neugebauer Citation1994, fig. 64:8). Thus, it appears that the same horses could have been used for pulling chariots and carts, as well as riding, depending on the needs and kinds of activities undertaken by the community. From this perspective, the Husiatyn horses may have been occasionally ridden but regularly used to pull a chariot or other vehicle during rituals and ceremonies. The latter case may have involved, for instance, the transport of the dead to monumental graves (mortuary houses) where they were cremated in situ within wooden funerary structures prior to the building of a mound (Makarowicz et al. Citation2016, Citation2018; Romaniszyn et al. Citation2021; Niebieszczański et al. Citation2022).

It is worthwhile here to focus on the markers of the Otomani-Füzesabony culture (O-FC) north and northeast of the Carpathian arc. In modern Poland, both fortified and open settlements of this culture have been documented, and many of their stylistic patterns have been observed on ceramics and metal artifacts in Subcarpathia (Makarowicz Citation2015). Moreover, clear inspirations from the style of O-FC bronze items and ceramics are visible in TCC material culture (Gancarski Citation2002; Makarowicz Citation2009, Citation2012, Citation2015; Jaeger Citation2010). This includes all horses buried with harnesses and horse-related artifacts found north of the Carpathians (see ; Przybyła Citation2020). Similar inspirations from the circle of cultures known for spiral-knob ornaments (with the exception of fortified settlements, but this is clearly due to the state of research) have been recorded in Ukraine (eastern Transcarpathia), while abundant materials and stylistic reminiscences have been documented in local Komarów culture barrows (O-FC metals and ceramic styles in the Ukrainian Carpathian Foothills and in the upper Dniester Valley—Sulimirski Citation1968; Makarowicz Citation2009, Citation2012; Makarowicz, Górski, and Lysenko Citation2013; Makarowicz et al. Citation2016), as well as farther north and east (Makarowicz, Górski, and Lysenko Citation2013; Górski Citation2017). A strong O-FC impact—probably related to the organization of long-distance routes (for the exchange of goods and raw materials including amber, bronze, and gold)—may have been the reason why these indicators of foreign material culture (e.g., horses with elaborate harnesses, chariots, or carts) appeared in this part of Central-Eastern Europe, especially in barrow burials (Czebreszuk Citation2011; Makarowicz Citation2012).

A legitimate question concerns the types of social implications brought about by the introduction of the chariot to communities north and northeast of the Carpathians. For example, how did it change the life of these Middle Bronze Age communities, particularly TCC groups, and what purpose did it serve there? Some researchers believe that the dissemination of chariots was not necessarily part of a single uniform ideology communicated through the same symbols. They emphasize that every cultural community has a peculiar, sometimes unique, socio-political structure and a consolidated system of values. Hence, its members may react differently to innovations, including the chariot package (Feldman and Sauvage Citation2010; Maran Citation2020). In most cases, local groups creatively adapted them to suit their needs but did not necessarily adopt the original functions and meanings of such innovations that were dominant in other cultural contexts (creative translation—Vandkilde Citation2014).

TCC communities are generally defined as unstratified kinship groups (lineages) that were moderately socially ranked and deeply rooted in the collectivist post-megalithic ideology that was very popular in the Neolithic. The dominance of mass burials used for several generations (Makarowicz et al. Citation2021), equal rights for both sexes, as well as adults, juveniles, and children, and peculiar depersonalization and deindividualization of grave goods suggest that the ownership of some goods, in particular those of superindividual significance, could have been collective (Makarowicz Citation2003, Citation2010). However, single and collective burials furnished with bronze, gold, or amber prestige objects and vessels that are Transcarpathian in style (O-FC) are recorded in the south of the TCC oecumene, sometimes in the monumental stone-timber structures of barrow graves (mortuary houses). They presumably belonged to the families of local peripheral elites with extensive intergroup contacts (Makarowicz Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2015). In this context, it can be reasonably believed that chariots/ritual carts were collective rather than individual property. Ostentatiously touting the role of horses and not people (e.g., the absence of teamsters included with horses buried in a team arrangement and the virtual absence of horse remains from human burials in barrows) and the absence of the remains of chariots/carts may suggest that these vehicles belonged to a group, for instance to a dominating lineage, and not to specific individuals. After the death of the horses, these vehicles were not buried with them but probably continued to be used for the same purpose by a successive pair of horses. Transitive trappings may have also included valuable harness elements. This may explain why some chariot horse burials lack bridle furnishings in many communities on the steppe and beyond. This, however, does not apply to the Husiatyn horses that—by reason of being buried in their rich harnesses—must have been greatly valued and enjoyed much respect from the community in question.

To address the question posed earlier about the significance of the chariot package for TCC communities, it is worth stressing yet again that it has been discovered almost exclusively in funerary contexts (chiefly in barrow graves), which is consistent with steppe traditions. Some horses were vital for the ritual life of Trzciniec communities and so enjoyed the right to individual burial in full harness within timber structures located beneath barrow mounds and without accompanying human retainers. These contexts argue strongly in favor of the use of the chariot package (or a horse-cart package) in the elaborate funerary rituals and thanatology of Middle Bronze Age TCC communities.

Conclusions

Paired horses buried in harnesses attest to their use for pulling chariots or other wheeled vehicles. These contexts emerged in the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia b.c. on the Ural-Kazakh steppes. The custom spread west and became common in successive Bronze Age phases, first in the middle Volga drainage basin, and reaching the borderland between the forest-steppe and forest zones in Central-Eastern Europe and mainland Greece several centuries later. There, it formed several separate concentrations—secondary adaptation centers (i.e., settlement zones)—where this innovation was in demand and where conditions were conducive to its incorporation into local traditions. Among them, burial concentrations in Małopolska in Poland, Podolia in western Ukraine and northeastern Moldova, and the area between the Dniester and Prut drainage basins in southeastern Ukraine and Romania emerged at the end of the first half and the beginning of the second half of the 2nd millennium b.c. These double-horse burials, and the chariot package associated with them, were introduced to these areas through intensive contacts between TCC communities and the Middle Bronze Age societies of the Carpathian Basin on one hand (which is attested to by the Carpathian-Danube harness style) and the steppe and forest-steppe communities of the Srubnaya culture and TCC on the other (adaptation of the custom itself).

Among TCC communities, it seems that this process was initiated by local barrow elites and reveals their aspirations to participate in long-distance networks in order to access international contacts and transit routes throughout Middle Bronze Age Eurasia. However, these were not military elites, nor aristocrats for that matter, appearing in grand narrations as prime movers of all socio-political and economic changes (e.g., Kristiansen and Larsson Citation2005; Kristiansen and Earle Citation2015). Rather, they comprised dominant lineages that were part of communities whose social structures were based on kinship. The chariot package, or perhaps its modified version (a cart in place of a chariot), was adapted by Trzciniec communities as a useful instrument in their elaborate funerary rituals. If it was a cart, it was probably used in rites of passage to transport corpses to their final resting place in barrow graves (mortuary houses); if it was a chariot, it could have added splendor to the funerary ceremonies of a deceased lineage member (parade-prestige functions).

The Husiatyn double-horse burial, dated to the early 15th century b.c., is spectacular, owing to the remarkable harness elements of both animals and their special anatomical characteristics. It must be stressed that Horse 2 was buried not only with rich furnishings but also in a dominant position within the grave relative to the other animal. Horse 2 was sturdier and more important in the team. It is possible that its death caused the other animal to be killed for inclusion in the burial. Both horses were, however, treated with due respect when alive and after death. This testifies that they were highly valuable to their owners/users. They belonged to a group of horses selected for special purposes. These were ritual animals; their exceptional status is borne out by their right to burial. After their deaths, they were buried within a barrow grave and in a team arrangement that reflected their role when alive, but without their teamsters. Thus, they were laid to rest like people but in a separate barrow, close to the place where they had worked and served.

The deposition of these horses with their harnesses and in a mirror-image position, combined with the wear of their premolar teeth and bone lesions, suggests that the Husiatyn horses were not very intensively used, probably both pulled a chariot/cart, and may also have been ridden. Antler bridle cheekpieces of the Spiš type and antler knobs with bronze rivets found next to the remains of the horses bear rich ornamentation in the style of the Carpathian-Danube area and eastern Mediterranean, proving that patterns from these areas appeared in the “barbarian” north and northeast.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (9.7 KB)Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Przemysław Makarowicz

Przemysław Makarowicz (Ph.D. 1997, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland) is a professor of archaeology at the Faculty of Archaeology AMU Poznań. His scholarly interests concern the processes of social and cultural transformations in Central and Eastern Europe in the Final Neolithic and the Early and Middle Bronze Ages.

Vasyl Ilchyshyn

Vasyl Ilchyshyn (M.A. 2007, Ternopil National Pedagogical University) is Director of the Zaliztsi Museum, Ternopil Region, Ukraine, and a researcher at the Security Archaeological Service of the Institute of Archeology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine. His research interests include the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age archaeology of the western part of Ukraine.

Edyta Pasicka

Edyta Pasicka (Ph.D. 2012, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences) is an assistant professor in the Division of Animal Anatomy at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Wrocław University. Her research interests include the anatomy of domesticated and wild living animals, breeding and usage of horses, structure of movement apparatus, and functional morphometry.

Daniel Makowiecki

Daniel Makowiecki (Ph.D. 1997, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences) is a professor of archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń. His research interests include the zooarchaeology of Holocene vertebrates and environmental archaeology.

Notes

1 Dendrological analysis by Dr. Tomasz Stępnik, Uni-Art, Poznań, Poland.

2 Chemical analysis by T. Y. Goshko, Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University, Ukraine.

References

- Anthony, D. W. 2007. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. How Bronze–Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Anthony, D. W., and D. R. Brown. 2011. “The Secondary Products Revolution, Horse–Riding, and Mounted Warfare.” Journal of World Prehistory 24: 131–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-011-9051-9.

- Anthony, D. W., and D. R. Brown. 2014. “Horseback Riding and Bronze Age Pastoralism in the Eurasian Steppes.” In Reconfiguring the Silk Road. New Research on East–West Exchange in Antiquity, edited by V. M. Mair, and J. Hickman, 55–71. Pennsylvania: University in Pennsylvania.

- Anthony, D. W., D. R. Brown, and C. George. 2006. “Early Horseback Riding and Warfare: The Importance of the Magpie Around the Neck”. In Horses and Humans: The Evolution of the Equine–Human Relationship, British Archaeological Reports Int. Ser. 1560, edited by S. L. Olsen, 137–156. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Bátora, J. 2018. Slovensko v Staršej Dobe Bronzovej. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenskeho v Bratislave.

- Bălășescu, A., C. Ilie, A.-I. Adamescu, T. Sava, and C. Simion. 2018–2019. “The Noua Culture Horse Burials from Negrilești (Galaţi County)”. Dacia 52-53: 351–368.

- Bąk, U. 1992. “Bronzezeitliche Geweihknebel in Südpolen.” Archäologische Korrespondenzblatt 22: 201–208.

- Bendrey, R. 2007. “New Methods for the Identification of Evidence for Bitting on Horse Remains from Archaeological Sites.” Journal of Archaeological Science 34: 1036–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.09.010.

- Bondár, M. 2012. Agyag Kocsimodellek a Kárpát–Medencéből (Kr. e. 3500–1500). Budapest: Archaeolingua.

- Boroffka, N. 1998. “Bronze– und Frűheisenzeitliche Geweihtrensenknebel aus Rumanien und Ihre Beziehungen. Alte Funde aus dem Museum fur Geschichte Aiud 2.” Eurasia Antiqua. Zeitschrift fűr Archaologie Eurasiens 4: 81–135.

- Boroffka, N. 2004. “Bronzezeitliche Wagenmodelle im Karpatenbecken.” In Rad und Wagen. Der Ursprung Einer Innovation. Wagen im Vorderen Orient und Europa, edited by M. Fansa, and S. Burmeister, 347–354. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Braudel, F. 1992. Kultura Materialna, Gospodarka i Kapitalizm XV-XVIII Wiek. Tom III. Czas Świata. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- Bronk Ramsey, C. 2009. “Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates”. Radiocarbon 51 (1): 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033822200033865.

- Brownrigg, G. 2006. “Horse Control and the Bit”. In Horses and Humans. The Evolution of Human–Equine Relationships, British Archaeological Reports Int. Ser. 1560, edited by S. L. Olsen, 165–171. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Burmeister, S., and Raulwing, P. 2012. “Festgefahren. Die Kontroverse um den Ursprung des Streitwagens. Einige Anmerkungen zu Forschung, Quellen und Methodik”. In Archaeological, Cultural and Linguistic Heritage. Festschrift for Erzsebet Jerem in Honour of her 70th Birthday, edited by P. Anreiter, E. Banffy, L. Bartosiewicz, W. Meid, and C. Metzner-Nebelsick. Archaeolingua, Series Maior 25, 93–113. Budapest: Archaeolingua Alapitvany.

- Chechushkov, I., and A. Epimakhov. 2018. “Eurasian Steppe Chariots and Social Complexity During the Bronze Age.” Journal of World Prehistory 31: 435–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-018-9124-0.

- Chechushkov, I. V., A. V. Epimakhov, and A. G. Bersenev. 2018. “Early Horse Bridle with Cheekpieces as a Marker of Social Change: An Experimental and Statistical Study.” Journal of Archaeological Science 97: 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.07.012.

- Chechushkov, I. V., E. R. Usmanov, and P. A. Kosintsev. 2020. “Early Evidence for Horse Utilization in the Eurasian Steppes and the Case of the Novoil’inovskiy 2 Cemetery in Kazakhstan.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (32), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102420.

- Chidioşan, N. 1984. “Prelucrarea Osului în Aşezările Culturii Otomani din Nord–Vestul României.” Crisia 14: 25–52. https://biblioteca-digitala.ro.

- Chondros, T., K. Milidonis, C. Rossi, and N. Zrnic. 2016. “The Evolution of the Double–Horse Chariots from the Bronze Age to the Hellenistic Times.” FME Transactions 44: 229–236. https://doi.org/10.5937/fmet1603229C.

- Csányi, M., and J. Tárnoki. 1992. “Katalog der Ausgestellen Funde”. In Bronzezeit in Ungarn. Forschungen in Tell–Siedlungen an Donau und Theiss, Edited by W. Meier–Arendt, 175–210. Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte: Frankfurt am Main.

- Czebreszuk, J. 2011. Bursztyn w Kulturze Mykeńskiej. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie.

- Daróczi, T.-T. 2018. “Bronzization and the Eastern Carpathian Basin.” In Bronze Age Connectivity in the Carpathian Basin, edited by B. Rezi, and R. E. Nemeth, 7–99. Targu Mureș: Editura MEGA.

- David, W. 1997. ““Altbronzezeitliche Beinobjekte des Karpatenbeckens mit Spiralwirbel– Oder Wellenbandornament und Ihre Parallelen auf der Peloponnes und in Anatolien in Fruhmykenischer Zeit”.” In The Thracian World at the Crossroads of Civilisations, edited by P. Roman, 247–305. Bucharest: Romanian Institute of Thracology.

- David, W. 2007. “Gold and Bone Artefacts as Evidence of Mutual Contact Between the Aegean, the Carpathian Basin and Southern Germany in the Second Millennium BC.” In Between the Aegean and Baltic Seas. Prehistory Across Borders (= Aegaeum 27), edited by I. Galanaki, H. Thomas, and R. Laffineur, 411–420. Liège: Universitè de Liège.

- Diaconu, V., and M. Sîbru. 2014. “Butonii de os şi Corn Descoperiţi în Mediul Culturii Noua”. Angvistia 17–18: 125–136.

- Dietz, U. L. 1992. “Zur Frage Vorbronzezeitlicher Trensenbelege in Europa.” Germania 70: 17–36.

- Dietz, O., and B. Huskamp. 2005. Praktyka Kliniczna: Konie. Łódź: Galaktyka.

- Dixon, P. M. 2017. “The Evolution of Horses and the Evolution of Equine Dentistry.” AAEP Proceedings 63: 79–116.

- Drews, R. 1993. The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Drews, R. 2004. Early Riders. The Beginnings of Mounted Warfare in Asia and Europe. New York and London: Routledge.

- Driesch, von den A. 1976. A Guide to the Measurement of Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites. Cambridge, Mass: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology & Harvard University.

- El Susi, G., and F. Burtănescu. 2000. “Un Complex cu Schelete de cai din Epoca Bronzului Descoperit într-un Tumul la Ripiceni (jud. Botoşani).” Thraco-Dacica 21: 257–263.

- Feldman, M. H., and C. Sauvage. 2010. “Objects of Prestige? Chariots in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean and Near East.” Agypten und Levante 20: 67–181.

- Fischl, K., V. Kiss, G. Kulcsár, and V. Szeverényi. 2015. “Old and New Narratives for Hungary Around 2200 BC.” In 2200 BC: A Climatic Breakdown as a Cause for the Collapse of the Old World?, edited by H. Meller, H. W. Arz, R. Jung, and R. Risch, 503–24. Halle: Landesamt Für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt–Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle.

- Florescu, A. C. 1991. Repertoriul Culturii Noua — Coslogeni din România. Aşezari şi Necropole. Călăraşi: Muzeul Dunării de Jos., Institutul de Tracologie.

- Florescu, M., and A. Florescu. 1990. “Unele Observaţii cu Privire la Geneza Culturii Noua în Zonele de Carbură ale Carpaţilor Răsăriteni.” Arheologia Moldovei 13: 49–102.

- Furmánek, V., and K. Marková. 2008. Včelince. Archiv Dávnej Minulosti. Nitra: Slovenská Akadémia Vied.

- Gancarski, J. 2002. Między Mykenami a Bałtykiem. Kultura Otomani–Füzesabony. Krosno: Muzeum Okręgowe w Krośnie.

- Gancarski, J. 2011. Trzcinica – Karpacka Troja. Krosno: Muzeum Okręgowe w Krośnie.

- Gening, V. F., G. Zdanovich, and V. V. Gening. 1992. Sintashta. Arkheologicheskiy Pamyatnik Ariyskikh Plemen Uralo–Kazakhstanskikh Stepey 1. Chelyabinsk: Yuzh.–Ural. knizhne izdatelstvo.

- Gogâltan, F. 2008. “Fortified Bronze Age Tell Settlements in the Carpathian Basin. A General Overview”. In Defensive Structures from Central Europe to the Aegean in the 3rd and 2nd Millennia BC, edited by J. Czebreszuk, S. Kadrow, and J. Müller. Studien zur Archäologie in Ostmitteleuropa 5. Poznań – Bonn: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Dr Rudolf Habelt Verlag, 39–56.

- Górski, J. 2017. “The Trzciniec Culture. On the Periphery of Bronze Age Civilization (1800–1100 BC).” In The Past Societies. Polish Lands from the First Evidence of Human Presence to the Early Middle Ages 3: 2000–500 BC, edited by U. Bugaj, 87–126. Warszawa: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology Polish Academy of Sciences.

- Hanks, B., R. Doonan, D. Pitman, E. Kupriyanova, and D. Zdanovich. 2015. “Eventful Deaths – Eventful Lives? Bronze Age Mortuary Practices in the Late Prehistoric Eurasian Steppes of Central Russia (2100–1500 BC).” In Death Rituals, Social Order and the Archaeology of Immortality in the Ancient World, ‘Death Shall Have no Dominion’, edited by C. Renfrew, M. Boyd, and I. Morley, 328–347. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanks, B. K., A. V. Epimakhov, and A. C. Renfrew. 2007. “Towards a Refined Chronology for the Bronze Age of the Southern Urals, Russia”. Antiquity 81: 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003598×00095235.

- Harding, A. F. 2000. European Societies in the Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harding, A. 2005. “Horse–Harness and the Origins of the Mycenaean Civilization.” In Autochton: Papers Presented to O.T.P.K. Dickinson on the Occasion of his Retirement, edited by A. Dakouri-Hild, and S. Sherratt, 296–300. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Hüttel, H. 1981. Bronzezeitliche Trensen in Mittel– und Osteuropa, Prähistorische Bronzefunde XVI 2. Munchen: CH Beck Verlag.

- Ilchyshyn, V. 2016. “Pokhovannia Poznei Epokhy Bronzy v Kurhani Bilia Husiatyna Ternopilskoi Oblasti.” Visnyk Riativnoi Arkheolohii 2: 77–90.

- Jaeger, M. 2010. “Transkarpackie Kontakty Kultury Otomani-Füzesabony.” In Transkarpackie Kontakty Kulturowe w Epoce Kamienia, Brązu i Wczesnej Epoce Żelaza, edited by J. Gancarski, 313–330. Krosno: Ruthenus.

- Johannsen, J. W. 2011. “Carts and Wagons on Scandinavian Rock Carving Sites”. Adoranten 2011: 95–107.

- Kadrow, S. 2001. U Progu Nowej Epoki. Gospodarka i Społeczeństwo Wczesnego Okresu Epoki Brązu w Europie Środkowej. Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Kraków.

- Kanne, K. 2022. “Riding, Ruling, and Resistance Equestrianism and Political Authority in the Hungarian Bronze Age.” Current Anthropology 63: 3. https://doi.org/10.1086/720271.

- Kelder, J. 2012. “Horseback Riding and Cavalry in Mycenaean Greece.” Ancient West and East 11: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2143/AWE.11.0.2175875.

- Klecel, W., and E. Martyniuk. 2021. “From the Eurasian Steppes to the Roman Circuses: A Review of Early Development of Horse Breeding and Management.” Animals 11), https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071859.

- Kopke, S., N. Angrisani, and C. Staszyk. 2012. “The Dental Cavities of Equine Cheek Teeth: Three–Dimensional Reconstructions Based on High Resolution Micro–Computed Tomography.” BMC Veterinary Research 8: 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-8-173.

- Kosintsev, P. A. 2010. “Chariot Horses.” In Koni, Kolesnitsy i Kolesnichie Stepey Evrazii, edited by V. S. Bochkarev, A. P. Buzhilova, I. V. Chechushkov, E. A. Cherlenok, АА Khokhlov, L. S. Klejn, P. A. Kosintsev, S. V. Kullanda, E. E. Kuzmina, P. F. Kuznetsov, M. B. Mednikova, and A. N. Usachuk, 56–79. Ekaterinburg–Samara–Donetsk: Rosiiskaya Akademiya Nauk.

- Kosintsev, P., and P. Kuznetsov. 2013. “Comment on “The Earliest Horse Harnessing and Milking”.” Tyragetia. Arheologie. Istorie Antică 7 (1): 405–407.

- Kosmetatou, E. 1993. “Horse Sacrifices in Greece and Cyprus.” Journal of Prehistoric Religion 7: 31–41.

- Kovács, T. 1969. “A Százhalombattai Bronzkori Telep.” Archaeologiai Értesítő 96: 161–169.

- Krause, R., A. V. Epimakhov, E. V. Kuprianova, I. K. Novikov, and E. Stolarczyk. 2019. “The Petrovka Bronze Age Sites: Issues in Taxonomy and Chronology.” Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 47 (1): 54–63.

- Kristiansen, K., and T. Earle. 2015. “Neolithic Versus Bronze Age Social Formations: A Political Economy Approach.” In Paradigm Found: Archaeological Theory Present, Past and Future: Essays in Honour of Evžen Neustupný, edited by L. Šmejda, J. Turek, and E. Neustupný, 234–247. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Kristiansen, K., and T. B. Larsson. 2005. The Rise of Bronze Age Society. Travels, Transmissions and Transformations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Krushenitska, L. 2006. Kultura Noa na Zemlyakh Ukraini. Lviv: Natsionalna Akademiya Nauk Ukraini.

- Kukushkin, I. A., and E. A. Dmitriev. 2019. “Kolesnichnyi Kompleks Mogilnika Tabyldy (Centralnyi Kazachstan).” Archeologiya, Etnografiya i Antropologiya Evrazii 47 (4): 43–52.

- Kuprianova, E., A. Epimakhov, N. Berseneva, and A. Bersenev. 2017. “Bronze Age Charioteers of the Eurasian Steppe: A Part–Time Occupation for Select Men?” Praehistorische Zeitschrift 92 (1): 40–65.

- Kuprianova, E. B., and D. G. Zdanovich. 2015. Drevnosti Lesostepnogo Zauralya: Mogilnik Stepnoe VII. Chelabinsk: Entsiklopediya.

- Kuznetsov, P. 2006. “The Emergence of Bronze Age Chariots in Eastern Europe.” Antiquity 80: 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00094096.

- Levine, M. 1999. “The Origins of Horse Husbandry on the Eurasian Steppe.” In Late Prehistoric Exploitation of the Eurasian Steppe, edited by M. Levine, Y. Rassamakin, A. Kislenko, and N. Tatarintseva, 5–58. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

- Librado, P., N. Khan, A. Fages, M. A. Kusliy, T. Suchan, L. Tonasso-Calvière, S. Schiavinato, et al. 2021. “The Origins and Spread of Domestic Horses from the Western Eurasian Steppes.” Nature 598: 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04018-9.

- Lindner, S. 2020. “Chariots in the Eurasian Steppe: A Bayesian Approach to the Emergence of Horse–Drawn Transport in the Early Second Millennium BC.” Antiquity 94 (374): 361–380. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.37.

- Lindner, S. 2021. Die Technische und Symbolische Bedeutung Eurasischer Streitwagen fur Europa und die Nachbarraume im 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Berliner Archäologische Forschungen 20. Rahden/Westf.: VML Vlg Marie Leidorf.

- Littauer, M. 1972. “The Military Use of the Chariot in the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age.” American Journal of Archaeology 76 (2): 145–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/503858.

- Littauer, M. A., and J. H. Crouwel. 1979. Wheeled Vehicles and Ridden Animals in the Ancient Near East. Leiden: Brill.

- Littauer, M. A., and J. H. Crouwel. 2002. Selected Writings on Chariots and Other Early Vehicles, Riding and Harness, Edited by P. Rauling. Leiden–Boston–Köln: Brill.

- Ludwig, A., M. Pruvost, M. Reissmann, N. Benecke, G. A. Brockmann, P. Castaños, M. Cieslak, S. Lippold, L. Llorente, A.-S. Malaspinas, M. Slatkin, and M. Hofreiter. 2009. “Coat Color Variation at the Beginning of Horse Domestication.” Science (324), https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172750.

- Makarowicz, P. 2003. “The Construction of Social Structure: Bell Beakers and Trzciniec Complex in North-Eastern Part of Central Europe.” Przegląd Archeologiczny 51: 123–158. https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/bitstream/10593/5709.

- Makarowicz, P. 2009. “Baltic–Pontic Interregional Routes at the Start of the Bronze Age.” Baltic–Pontic Studies 14: 301–336. https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/handle/10593/5698.

- Makarowicz, P. 2010. “Trzciniecki Krąg Kulturowy – Wspólnota Pogranicza Wschodu i Zachodu Europy”. Archaeologia Bimaris, Monografie, vol. 3. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie.

- Makarowicz, P. 2012. “Zwischen Baltischem Bernstein und Transylvanischem Gold. Der Trzciniec–Kulturkreis – Nordostlicher Partner der Otomani/Fuzesabony–Kultur.” In Enclosed Space — Open Society. Contact and Exchange in the Context of Bronze Age Fortified Settlements in Central Europe (= Studien zur ArchäoLogie in Ostmitteleuropa 9), edited by M. Jaeger, J. Czebreszuk, and K. Fischl, 177–214. Poznań–Bonn: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Dr. Rudolf Habelt Verlag.

- Makarowicz, P. 2015. “Karpackie Osady Obronne i Dalekosiężne Szlaki Tranzytowe w II tys. BC – Perspektywa Północy.” In Pradziejowe Osady Obronne w Karpatach, edited by J. Gancarski, 109–130. Krosno: Muzeum Podkarpackie w Krośnie.

- Makarowicz, P., T. Goslar, J. Górski, H. Taras, A. Szczepanek, Ł Pospieszny, M. O. Jagodinska, M. O., Ilchyshyn, V., Włodarczak, P., Juras, A., Chyleński, M., Muzolf, P., Lasota-Kuś, A., Wójcik, I., Matoga, A., Nowak, M., Przybyła, M. M., Marcinkowska-Swojak, M., Figlerowicz, F., Grygiel, R., Czebreszuk, J., and I. T. Kochkin. 2021. “The Absolute Chronology of Collective Burials from the 2nd Millennium BC in East Central Europe.” Radiocarbon 63 (2): 669–692. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2020.139.

- Makarowicz, P., J. Górski, and S. Lysenko. 2013. “Pontic and Transcarpathian Cultural Patterns in the Trzciniec Circle Between the Prosna and Dnieper.” Baltic–Pontic Studies 18: 162–202. https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/handle/10593/13223.

- Makarowicz, P., I. Kochkin, J. Niebieszczański, J. Romaniszyn, M. Cwaliński, R. Staniuk, H. Lepionka, I. Hildebrandt-Radke, H. Panakhyd, Y. Boltryk, V. Rud, A. Wawrusiewicz, T. Tkachuk, R. Skrzyniecki, and C. Bahyrycz. 2016. Catalogue of Komarów Culture Barrow Cemeteries in the Upper Dniester Drainage Basin (Former Stanisławów Province), Archaeologia Bimaris, Monographies, vol. 8, Poznań: Institute of Archaeology AMU.

- Makarowicz, P., T. Goslar, J. Niebieszczański, M. Cwaliński, I. T. Kochkin, J. Romaniszyn, S. D. Lysenko, and T. Ważny. 2018. „Middle Bronze Age societies and barrow line chronology. A case study from the Bukivna ‘necropolis’, Upper Dniester Basin, Ukraine”. Journal of Archaeological Science 95: 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.04.010.

- Makarowicz, P., J. Niebieszczański, M. Cwaliński, J. Romaniszyn, V. Rud, and I. Kochkin. 2019. “Barrows in Action. Late Neolithic and Middle Bronze Age Barrow Landscapes in the Upper Dniester Basin, Ukraine.” Praehistorische Zeitschrift 94: 92–115. https://doi.org/10.1515/pz-2019-0013.

- Maran, J. 2020. “The Introduction of the Horse-Drawn Light Chariot – Divergent Responses to a Technological Invention in Societies Between the Carpathian Basin and the East Mediterranean.” In Objects, Ideas and Travelers Contact Between the Balkans, the Aegean and Western Anatolia During the Bronze and Iron Age. Volume to the Memory of Alexandru Vulpe Proceedings of the Conferecne in Tulcea, 10-13 November, 2017, edited by J. Maran, R. Băjenaru, S.-C. Ailincăi, A.-D. Popescu, and S. Hansen, 505–28. Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt Verlag.

- Maran, J., and A. van de Moortel. 2014. “Connections from Late Helladic I Mitrou and the Emergence of a Warlike Elite in Greece During the Shaft Grave Period.” American Journal of Archaeology 118 (4): 529–548.

- May, E. 1985. “Widerristhöhe und Langknochenmasse bei Pferden — ein Immer Noch Aktuelles Problem.” Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 50: 368–382.

- Metzner-Nebelsick, C. 2021. “Chariots and Horses in the Carpathian Lands During the Bronze Age.” In Distant Worlds and Beyond. Special Issue Dedicated to the Graduate School Distant Worlds (2012‒2021), Distant Worlds Journal Special Issue 3, edited by B. Baragli, A. Dietz, Zs. J. Foldi, P. Heindl, P. Lohmann, and S. P. Schluter, 111–13. Heidelberg: Propylaeum. https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.886.c11954.

- Miyazaki, S., C. Y. Liu, and Y. Hayashi. 2017. “Sleep in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Animals, and Insights Into the Function and Evolution of Sleep.” Neuroscience Research 118: 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2017.04.017.