The interconnection between archaeology as a discipline and the practice of it has been inextricably linked with the evolution of how we document places, monuments, objects, and people. From the late 19th to the early 20th century a.d., photography emerged as a powerful tool in this process. This technological advancement in turn facilitated a move towards greater efficiency in our near obsession with categorizing and inventorying “the past.” By the mid-20th century a.d., a paradigm shift occurred in archaeological methodology and recording. The emphasis on stratigraphy meant that archaeologists began to illustrate from the trenches, incorporating levels and coordinate measurements to visually represent the layers of history. The introduction of the Harris matrix and radiocarbon dating further enriched archaeological analyses by providing even greater detail in exploring contextual relationships over time. These new approaches enabled archaeologists to engage with past human experiences on a more profound level.

Advancements in survey approaches, too, allowed archaeologists to track changes in landscapes. Early maps and historical aerial images have been instrumental in identifying archaeological sites from the air. In densely covered regions, such as the Amazon basin, Central America, and Southeast Asia, lidar has become an increasingly powerful tool for broad-scale analyses; and when paired with integrative ethnographic methodologies, the results can be particularly revealing. This uplifting in socio-technological and participatory aspects of landscape documentation and transformation are bolstered by datapoints that allow us to track significant changes in climate. And, yet, how do we grapple with the experience of weather, of understanding how landscapes perform, and how communities respect and respond to significant, punctuated events as well as changes over a decade or so? How might more meaningful engagement deepen our commitment to the study of the longue durée and, more broadly, the Anthropocene?

Capturing the emotional and physical reactions to our bodies is something much more challenging, much more personal. Real-time documentation and on-the-ground fieldwork offers snapshots of transformative changes occurring year-by-year, decade-by-decade, century-by-century. These changes include the disappearance of lakes, rivers, forests, and glaciers due to factors such as flooding, desiccation, and fires, many inextricably linked to human-induced agency. How one reacts to an incoming torrential rainstorm, or the smoke-filled skies of a forest blaze, is often distant from what can be gleaned from the archaeological record. Archaeologists do, however, implicitly experience the impacts of weather in-place: the physical, the visual, and the audible. Whether the heat of the mid-day sun or a midnight summer lightning strike followed by a few minutes of unrelenting hail, extreme weather and its impacts on-site, in a region, come to be internalized by archaeologists. Yet, how do they respond to such events, as researchers, as people?

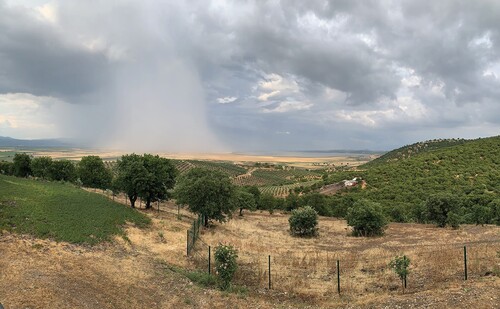

Indeed, in late October 2021, I found myself in this juxtaposition of science and experience as I tried to tame my headache from the relentless sounds and vibrations of a truck-mounted coring machine boring into a desiccated lakebed (). I lamented the disappearance of a wetland that I’d spent two decades of my own life coming to know (, ). Even so, I participated in the rush to study, to document the drastic changes taking place in the Marmara Lake Basin of western Anatolia, an area initially included in the proposed mixed natural-cultural landscape of the tentative list for World Heritage of The Ancient City of Sardis and the Lydian Tumuli of Bin Tepe (Luke Citation2019, 143–174). Natural Landscapes and the diachronic aspects of the region were removed from consideration, but research and development have continued apace. We now know from Ottoman narratives, archaeological datasets, and ethnographic study that the past vibrancy of life in this region significantly ebbed and flowed seasonally, responding to the lives of wetlands, ponds, lakes, and rivers (see , ). For millennia, these water features were active, living bodies; people once understood and responded to them as members of a community, as part of their place-making—from subsistence to symbolism (Luke and Roosevelt Citation2016; Roosevelt et al. Citation2018; Luke Citation2019; Marston et al. Citation2022; Çelik, Luke, and Roosevelt Citation2023; Irvine et al. Citation2023). Over the pandemic of COVID-19, I spent a lot of time here, and I saw this vast body of water slowly, but surely, disappear. I watched as mystifying storms rolled in (), and other days, I struggled to walk across the cracked, brittle, newly exposed face of the landscape. Careful not to turn an ankle, I was mindful of the things on the surface—fishing nets, bullet casings, as well as the adjacent fields of organic cotton and plans for future wheat cultivation in the lakebed. The day prior in a nearby industrial park, I’d gazed in awe at a giant heap of perforated irrigation hose (), the new normal in sustainable irrigation. A year later, in October 2022, I stared in silence from above () as the flight I was on happened to pass directly over. I tried in vain to grasp my own participation in the Anthropocene (Luke Citationin press).

Figure 2. Mid-day sun peeking through cloud cover over Lake Marmara, March 2021. Photo courtesy of author.

The performative aspect of climate and landscapes will feature in an upcoming special issue of the Journal. That archaeologists might engage with concepts of the Anthropocene, whether as an event or epoch, is not necessarily surprising, and the Journal has published essays on the topic for some time. Academic articles allow for critical assessments of human agency in specific places over long periods of time. Even so, how might we support our authors in their effort to convey the rich diversity of what happens in a place at a specific time? This is difficult at best through traditional, linear, academic, text-based narratives. This challenge has shaped the decision to open up the Journal to photo essays. While the approach is not new to publishing, it is new for us. The inaugural essay in this format, authored by Chad Hill and his colleagues, delves into their experiences during May and June 2023, which exposed them to the realities of catastrophic flooding in the Jordanian Black Desert. They thought that they knew this region, and with good reason. They had spent many years, at the same time each year, in-place (Rowan et al. Citation2015, Citation2017; Hill and Rowan Citation2022). And, yet, 2023 was different, at least for them.

In this photo essay, they explore a suite of images, and in so doing, they confront seasonality, climate change, and what it means to be in-place, to experience. This approach is both deeply personal and broadly significant for how researchers who don’t live in these spaces balance what is meant by knowledge. Once stranded, they learned that, while rare, such flooding wasn’t unknown—oral histories and knowledge bases of proximate communities confirmed that such events do happen. What this group of archaeologists grappled with, in addition to the weather, was their own limitations. Their self-reflectivity pushed them to document in photographs what they felt at the time, a period of increased risk as well as opportunity. This immersive experience provided their team with a profound and deeper understanding of the Black Desert.

Must all future photo essays in the Journal focus on weather, space, and climate? No, most certainly not. To our authors, we ask that you think holistically about how photo essays reveal aspects of doing archaeology and heritage in ways that challenge the format of linear text. As you consider your future work and themes, we encourage you to think broadly, to think differently. We look forward to capacity-building for innovation, leveraging all types of visual and technical engagement. For all those willing and interested, please be in touch.

References

- Çelik, S., C. Luke, and C. H. Roosevelt. 2023. “Ottoman Lakes and Fluid Landscapes: Environing, Wetlands and Conservation in the Marmara Lake Basin, Circa 1550–1900.” Environment and History.

- Hill, A. C., and Y. M. Rowan. 2022. “The Black Desert Drone Survey: New Perspectives on an Ancient Landscape.” Remote Sensing 14 (3): 702.

- Irvine, B., N. Shin, C. Luke, and C. H. Roosevelt. 2023. “Stable Carbon Isotope (δ 13C) Analysis of Archaeobotanical Remains from Bronze Age Kaymakçı (Western Anatolia) to Investigate Crop Management.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 1–12.

- Luke, C. 2019. A Pearl in Peril: Heritage and Diplomacy in Turkey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Luke, C. In Press. “The Longue-Durée of Paradise Lost: The Anthropocene of Anatolia’s Wetlands.” In Aquatic Worlds of Anatolia, edited by A. Wick, A. Rappas, and M. Harpster. Istanbul: Koç University.

- Luke, C., and C. H. Roosevelt. 2016. “Memory and Meaning in Bin Tepe, the Lydian Cemetery of the ‘Thousand Mounds’.” In Tumulus as Sema: Proceedings of an International Conference on Space, Politics, Culture, and Religion in the First Millennium BC, edited by U. Kelp, and O. Henry, 407–428. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Marston, J. M., C. Çakırlar, C. Luke, P. Kováčik, F. G. Slim, N. Shin, and C. H. Roosevelt. 2022. “Agropastoral Economies and Land Use in Bronze Age Western Anatolia.” Environmental Archaeology 27 (6): 539–553.

- Roosevelt, C. H., C. Luke, S. Ünlüsoy, C. Çakırlar, J. M. Marston, C. R. O’Grady, P. Pavúk, M. Pieniążek, J. Mokrisˇová, C. Scott, N. Shin, and F. Slim. 2018. “Exploring Space, Economy, and Interregional Interaction at a Second-Millennium B.C.E. Citadel in Central Western Anatolia: 2014–2017 Research at Kaymakçı.” American Journal of Archaeology 122 (4): 645–88. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.122.4.0645.

- Rowan, Y. M., G. O. Rollefson, A. Wasse, W. Abu-Azizeh, A. C. Hill, and M. M. Kersel. 2015. “The ‘Land of Conjecture:’ New Late Prehistoric Discoveries at Maitland’s Mesa and Wisad Pools, Jordan.” Journal of Field Archaeology 40 (2): 176–189.

- Rowan, Y. M., G. Rollefson, A. Wasse, A. C. Hill, and M. M. Kersel. 2017. “The Late Neolithic Presence in the Black Desert.” Near Eastern Archaeology 80 (2): 102–113.