ABSTRACT

Archaeologists routinely create backdirt during excavation, but it is rarely acknowledged and remains surprisingly undertheorized. In this paper, we treat backdirt as a uniquely archaeological product that is socially constructed and guided by culturally and historically situated motivations. Using Chaco Canyon as a case study, we examine the ways in which project priorities changed over nearly 150 years of excavation and (more recently) re-excavation. We illustrate the importance of understanding backdirt as a social product by comparing the avifaunal assemblages created by two major excavation projects at the great house of Una Vida. Differences in these assemblages demonstrate how changes in research goals structured what was collected, what was left as backdirt, and how this ultimately impacts interpretations about Chaco history. Finally, we offer thoughts about the future role of backdirt in archaeological praxis as a space to welcome feminist and Indigenous perspectives in the construction of archaeological narratives.

Introduction

Backdirt is generally understood as the material encountered during archaeological excavation for which further investigation is deemed unnecessary, in contrast with the materials that are collected as part of the archaeological record. While routinely created by archaeologists, backdirt is rarely acknowledged and remains one of the most undertheorized products of archaeology.

Fundamentally, backdirt reflects necessary choices made by all projects. Project directors decide where to survey and excavate in the field based on the research questions they hope to answer, as well as setting expectations about collection protocols such as screen size and when soil, flotation, or other samples should be taken. Excavators, both professionals and students, continuously make choices about what materials should be collected from the larger site matrix and what should be relegated as backdirt. The curation process introduces another step, with museum staff deciding what should and can be curated, what should be cataloged individually or in bulk, and how much care different materials require. Combined, all of these decisions structure the types of questions that can be posed by later researchers who decide which materials receive further analysis. Although few archaeologists would disagree that backdirt is the result of theoretical and methodological decisions, the lack of explicit focus on backdirt as an archaeological entity often leads to an implicit acceptance that it is self-evident and scientifically neutral. In contrast, by theorizing backdirt as a product of project goals and procedures at many stages, it can instead be viewed as a valuable and tangible record of a project’s decision making, guiding principles, and core question, including what should be excavated, recorded, collected, curated, and given additional analysis.

Since backdirt is not a static or neutral entity, it offers a unique opportunity to consider histories of archaeological praxis. In North American archaeology, the U.S. Southwest provides an ideal context for the reexamination of our relationships to, and the prospectives of, backdirt. From cowboy archaeologists and the fervid museum-sponsored excavations of the 19th and 20th centuries a.d., to decades of intensive field schools and extensive mitigation excavations in the wake of urban development, thousands of metric tons of fill have been excavated from archaeological sites in the region. Given the long record of excavation, the Southwest offers insight into the ways in which archaeological praxis has changed over the past century and a half. While scientific innovation and sampling strategies have driven many of these shifts, recent decades have increasingly focused on how our attribution of archaeological significance influences subsequent understandings of the past. Feminist (e.g., Gero and Conkey Citation1991; Wylie Citation1997) and Indigenous (e.g., Atalay Citation2016; Deloria Citation1969) critiques of archaeology, in particular, have pushed the discipline to critically reflect on how we produce knowledge about the past and whose pasts we emphasize in our narratives. A focus on backdirt can contribute to these critiques by highlighting what has and has not been considered a meaningful part of the archaeological record over time.

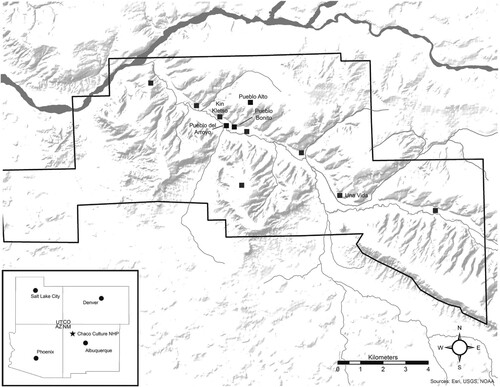

In this paper, we illustrate the impacts of historical and modern decision-making in the production of the archaeological record with examples from the history of research within Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (). Spanning well over a century, the history of research in what is now Chaco Culture National Historical Park (CCNHP) serves as a case study to examine the ways in which researchers have shaped the archaeological record and its subsequent interpretations through time (see Lekson Citation2018; Plog Citation2015, Citation2018; Plog, Heitman, and Watson Citation2017). We focus on the historically and culturally situated motivations, research questions, and methodologies that have structured the production of the archaeological record and its conceptual antithesis: backdirt. With an increasing awareness of curation limitations (e.g., Bawaya Citation2007) and a broad pivot towards prioritizing the conservation and preservation of archaeological sites (e.g., Comer Citation2020; Doelle Citation2012), we interrogate the ways backdirt has been produced and the potential of backdirt for future research into Southwest archaeology.

A Culture History of Backdirt Production in Chaco Archaeology

Located in the center of the San Juan Basin, Chaco Canyon (see ) and its prominent standing architecture have attracted archaeological attention since the mid-19th century a.d. The construction of monumental great houses, importation of distant and high value materials, and concentration of these objects within great house contexts have long been interpreted as evidence for substantial shifts in sociopolitical organization, but the specific structure of those relationships continue to be debated by scholars (e.g., Lekson Citation2018; Mills Citation2023; Plog Citation2018). As many prominent Southwest scholars have contributed to the creation of backdirt in Chaco Canyon over the past century, an examination of the history of Chaco’s excavation provides a window into the temporal development of archaeological research in the U.S. Southwest. A review of backdirt production in Chaco also provides a better understanding of the historic motivations, driving forces, and unintended biases that have guided these endeavors. Because a complete review of the history of research in and around Chaco Canyon is outside the scope of this paper (but see Lekson Citation1984, Citation2018; Mathien Citation2005; Plog Citation2015), we focus on the history of practice best exemplifying the ways in which backdirt was defined over time by archaeological practice and the interpretive implications of these decisions.

“Nothing of interest was found in this room” producing Chaco’s earliest backdirt

Some of the earliest excavations in the U.S. Southwest took place in Chaco Canyon. These projects were largely driven by the search for “museum-quality” objects to fill newly established museums in the late 19th and early 20th centuries a.d. (see Plog Citation2015, 6). A short trip to the canyon by Mr. Robert Singleton Peabody exemplifies this approach, as he was specifically employed to make a “typical collection in three weeks” (Moorehead Citation1906, 33). In a.d. 1897, Peabody excavated four rooms in Pueblo Bonito, destroying upper stories and scattering artifacts and human skeletal remains across five different rooms (Marden Citation2011, 205). The project eventually shipped around 2000 artifacts to the East Coast, but as noted by Crown and Wills (Citation2018, 901), the damage and confusion imposed from this single excavation “has taken over a century to document.” Peabody’s scattered materials, including the remains of countless Indigenous ancestors, can be seen as one of the earliest episodes of backdirt production in the region.

The first formal excavations in Chaco Canyon were undertaken in the 1890s a.d. by George W. Pepper and Richard Wetherill of the Hyde Exploring Expedition, sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History (Pepper Citation1920). As was also the case for the next large project headed by Neil M. Judd in the 1920s a.d. and sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, the focus of this work was on the large-scale excavation of Pueblo Bonito, the central and arguably largest great house located within Chaco Canyon. While these expeditions were driven by loosely defined scientific goals of identifying “archaeological cultures” (see Cameron Citation2005), this was an era of fierce competition amongst museum institutions working to establish a foothold by attracting wealthy patrons with the promise of spectacular discoveries (Snead Citation2001). This quest for prestige, power, and institutional prominence was also carried out amidst the increasing threat of antiquarians and pot hunters fueled by the economic opportunities associated with public interest in owning pieces of a newly discovered past (Snead Citation2001).

Combined, Pepper and Judd’s projects excavated nearly 95% of the 600 + room Pueblo Bonito, collectively shipping off thousands of objects by the trainload to their museum sponsors on the East Coast (see Plog Citation2015, Citation2018). Data collection for these projects was far less systematized, with much information documented solely in the field notebooks of project directors. As such, certain contexts, such as floors, rare or unusual deposits, and burials, received significant attention, while other materials like faunal assemblages and ground stone, were overlooked, as they were discarded as “trash” or viewed as unnecessary to record in detail (see Fladd, Hedquist, and Adams Citation2021; Heitman Citation2016).

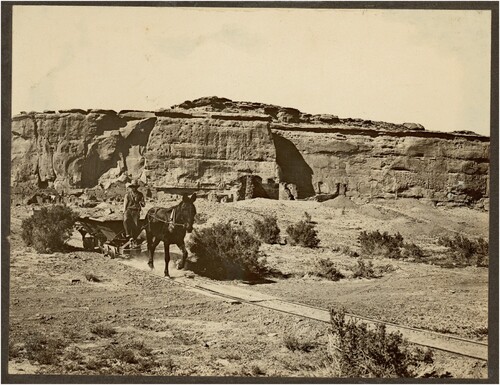

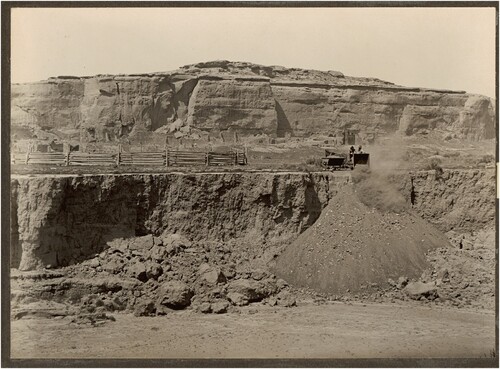

As noted earlier, most archaeologists privilege floor contexts as more valuable and informative than fill contexts. Driven by this assumption, fill was excavated largely in bulk, with only floor contexts being singled out for documentation (see Adams Citation2002, 19). The prioritization of objects of “museum quality” is made clear in the resulting publications from these excavations. Pepper (Citation1920), for example, frequently used the phrase “Nothing of interest was found in this room” when describing his excavations of rooms at Pueblo Bonito. While some have interpreted this as evidence for largely “empty” rooms, review of field notes by individual scholars (e.g., Neitzel Citation2003) and their entry into the Chaco Research Archive (CRA, chacoarchive.org) demonstrates the rooms simply did not contain materials deemed noteworthy for the time. These reviews have also made clear the number of objects that were either deliberately discarded or gifted to workers during the excavation process, as well as important developments in excavation methodologies (see Heitman Citation2011). Screening of sediments was not common at the time, with definitive screening of only one area of Pueblo Bonito—the highly culturally dense room block associated with the northern burial cluster (Plog and Heitman Citation2010, 19622). Additionally, these early excavations involved the routine dumping of room fill—including sediments, ecofacts, and objects—into the Chaco Wash to open rooms for public viewership and clear backdirt created by earlier excavations in the case of Judd’s 1920s a.d. fieldworkFootnote1 (Judd Citation1954, 18; ). Because the Chaco Wash floods periodically, the backdirt, or unwanted remains of previous archaeologists’ work, were ultimately carried downstream.

Figure 2. Mule-drawn carts used to carry backdirt from the great house excavations to Chaco Wash. Photo by Neil M. Judd, 1922. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NGS 0477.

Figure 3. Carts being positioned to receive backdirt in the West Court of Pueblo Bonito. Photograph by O. C. Havens, 1924. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NGS 0473.

Figure 4. Backdirt from Pueblo Bonito being dumped into Chaco Wash. Photograph by O. C. Havens, 1924. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NGS 0471.

In some instances, backdirt was treated as a resource to meet other needs. In the 1930s a.d., the National Park Service sought to circumvent erosion in Chaco Wash that was actively threatening many Chaco great houses and small sites. As part of an experimental erosion control study, backdirt from the University of New Mexico’s a.d. 1934 excavations of Kin Kletso, at times supplemented with the use of dynamite, was used to construct experimental erosion control features filling in eroding side arroyos that had formed over timeFootnote2 (Chauvenet Citation1935, 11–13). The use of the university’s backdirt was considered a mutually beneficial solution for both projects: “Excavation was carried on at Kin Kletso at the same time that the bank protection work was done. This work required a place to dump the refuse taken from the ruin. The nearness of the bank solved this problem in a very satisfactory manner. Extra material was needed for the bank protection, and this was easily and cheaply obtained from the excavation. Thus the two projects supplemented each other to their mutual advantage” (Chauvenet Citation1935, 11). The “refuse” referred to here emphasizes the view of archaeological backdirt as an archaeologist’s trash, a connotation that has long affected how researchers view materials and their meaning in the Southwest (see Fladd, Hedquist, and Adams Citation2021). In addition to the focus on erosional control, work by Civilian Conservation Corp groups in the 1930s a.d. also began the process of architectural stabilization to ensure site preservation and the potential for future visitors to the then National Monument (see Svare Citation2015, 11–12).

Together, these practices resulted in a highly curated collection of materials that is often taken as broadly representative of the entire Chaco region, culture, and time period. However, the role of archaeology in society and the sponsorship by museums, often on the East Coast, influenced this record by attributing more value to certain types of material than to others. While there remains significant value in working with these datasets, as will be discussed later in this paper, doing so requires a clear understanding of both what these collections represent and what was defined as backdirt by archaeologists working during this time.

Scientific turn in Chaco research

By the mid-1900s a.d., archaeologists were explicitly seeking to differentiate themselves from the other subfields of American anthropology (Fowles and Mills Citation2017, 26). Doing so required separating the discipline from antiquarians and looters by embracing archaeology as an explicitly scientific study of the past (sensu Binford Citation1962). This scholarship, primarily by university- or federally-led research projects and field schools, had a profound role in fostering novel developments in archaeological method and theory. Proponents of this newfound scientific approach to archaeology embraced sampling as a fundamental means of data standardization to more objectively evaluate salient patterns of human behavior.

In Chaco archaeology, this fluorescence of hypothesis testing is most clearly exemplified by the National Park Service’s widely-known Chaco Project, one of the largest field research projects to date (Lekson Citation2006; Mathien Citation2005). Conducted from 1971–1982, this project resulted in numerous publications following extensive survey and targeted excavations at select great houses and several small sites throughout the canyon (e.g., Judge and Schelberg Citation1984; Truell Citation1992). The project embraced new scientific methodologies, including the routine screening of sediment using standard-sized screens and the introduction of arbitrary excavation units. Robust sampling strategies guided the placement of excavation units and the collection of different classes of artifacts and pollen and flotation samples for botanical analyses (Mathien Citation2005, 11–17). They also identified certain materials, like roofing material, wood, and burned adobe, that could be sufficiently analyzed in-field by weighing and measuring before discarding. The updated methodologies allowed for the systematic testing of research hypotheses about Chacoan society (e.g., Judge Citation1979), a vastly different driving force than the earlier work focused on building museum collections.

In some cases, the perceived value of certain materials’ research potential changed over the course of the Chaco Project. For example, manuport pebbles were frequently encountered in their excavations. Although these materials were noted as being deliberately brought to these rooms by the residents of Pueblo Alto, the excavators decided that they lacked research potential because they had no observable evidence for modification. Although they temporarily tried to sample the pebbles for collection, Windes (Citation1987, 75) notes that “there were no cries of rage when this collection strategy died.” The decision itself reflects the need to make systematic changes throughout the excavation process to meet research needs. While these pebbles may or may not contain information of value for archaeologists, they do emblematize the ways in which decisions about archaeological practice define both the archaeological record and the backdirt left behind by excavation projects.

The focus of the Chaco Project’s research shifted Chaco scholarship significantly to an emphasis on large-scale investigations of social models and environmental reconstructions (e.g., Mathien Citation2005) and the targeted sampling of specific locales throughout the canyon. It is during this period that the project director James Judge (Citation1979) argued for Chaco as a pilgrimage center, suggesting that very few people actually lived in the canyon and instead that it was used to host migrants for ceremonies and events held by the local priestly population. This argument was primarily based on 1) the aridity of the region and 2) assumptions that great houses were not occupied, due to low artifact counts. The latter depended in part on the failure to account for different collection strategies, specifically the ways in which backdirt created by Pepper and Judd would frequently contain objects that would have been systematically collected by the Chaco Project. Additionally, the extrapolation of artifact counts from the Pueblo Alto sampling strategies was used to bolster these concerns (see Plog and Watson Citation2012 for a reanalysis). While the methodologies employed by the Chaco Project match closely those followed today, the consideration of the decisions involved in the creation of the archaeological record remains crucial for further interpretation of the sociopolitical realities of the Chaco people.

Re-Excavating Chaco: Scholarship in the 21st Century a.d. and the Changing Face of Una Vida

Research conducted in Chaco Canyon in the 21st century a.d. has largely pivoted to the reanalysis of existing collections and data and the re-excavation of old excavation units from earlier projects. Because of its long and varied history of archaeological research, all research on Chaco Canyon today requires regular and measured reconciliation of the differences between archaeological projects. Since each project was guided by different goals, backdirt can continue to reveal the priorities that structured the original excavations that are often left unstated. As such, backdirt can be used as a valuable analytical entity for reconstructing both archaeological histories and histories of archaeology.

Several notable projects have embarked upon the re-excavation of previously excavated contexts to either gather additional data or to test previous assumptions that were not recorded to modern standards. The University of New Mexico (UNM) has conducted two high profile re-excavation projects in the refuse mounds south of Pueblo Bonito (e.g., Crown Citation2016; Wills et al. Citation2015) and in Room 28 in the northern arc (Crown Citation2020). The re-excavation of Pueblo Bonito’s Room 28 not only answered important questions about the nature and timing of events that occurred within the space 1000 years ago but also provided unequivocal evidence of the extensive mixing of deposits in the backfill by early excavators (Crown Citation2016). The re-excavation of Neil Judd’s trenches in the refuse mounds south of Pueblo Bonito according to modern collection standards recovered over 217,000 artifacts previously unrecorded (Crown Citation2020). The University of Virginia’s work re-excavating portions of Roberts’ Great House revealed that the great house was never completed or occupied (Watson et al. Citation2014), confirming speculations by Roberts (Citation1929) that were previously lacking documentary evidence. Finally, an overlapping team led by Scarborough (Scarborough et al. Citation2018) from the University of Cincinnati relied upon Gwinn Vivian’s physical backdirt (and remnant flagging tape) to guide the placement of excavation areas for Optically-Stimulated Luminescence dating, which added invaluable chronological control to our understanding of agricultural infrastructure in the canyon (Vivian and Fladd Citationin press).

Building upon the insights from these projects, we ask: how have our decisions about what is discarded or kept, and what is analyzed or not analyzed, affected what we know and what is knowable in Chaco archaeology? How can the reexamination of backdirt contribute to resolving these debates? To illustrate the interpretive implications of different excavation projects through time, we offer a brief case study from the excavations of the great house Una Vida.

Excavating Una Vida

With construction phases beginning in the mid-800s a.d. and flourishing in the mid-900s a.d., Una Vida is one of the earliest Chaco great houses in the canyon, offering a unique glimpse into the early days of Chacoan life (Akins and Gillespie Citation1979, 2–3; Lekson Citation1984). The first formal excavations at Una Vida were carried out by Gordon Vivian in the 1950s and 1960s a.d. on behalf of the National Park Service. In a.d. 1956 and 1957, Vivian excavated one ceremonial structure called a kiva and trenched a portion of the eastern wing of the pueblo in the course of conducting stabilization work. Then in a.d. 1960, when Una Vida was selected to be excavated and left open for National Monument visitors, Vivian excavated 15 rooms in the northern corner of the great house (Lekson Citation1984, 90–93; Mathien Citation2005, 161–163, table A.4; Windes Citation1987, 10).

Vivian was not able to prepare a report summarizing his excavations before his death in a.d. 1966. The only components of Vivian’s excavations that were published were a stabilization report (Shiner and Vivian Citation1960) and a brief report on the remains of wild birds that had been analyzed by Lyndon Hargrave (Hargrave Citation1961). The remainder of Vivian’s excavation notes were sparse. It was not until a.d. 1978 that the National Park Service decided Una Vida would not be developed for tourism and that it was best to backfill the excavated rooms in order to eliminate the need for expensive stabilization efforts.

Before Una Vida was backfilled, Nancy J. Akins and William B. Gillespie took the opportunity to more thoroughly document the site as part of the National Park Service’s Chaco Project (Akins and Gillespie Citation1979; Mathien Citation2005, 161–163, table A.5). Because so little was known about Vivian’s excavations of Una Vida, the goal of the Chaco Project’s work was “to record pertinent archaeological data which were not collected at the time of [Vivian’s] excavation” (Akins and Gillespie Citation1979, 3). This work required direct engagement with Vivian’s backdirt, confronting the products of his priorities and decision-making. In one instance, Akins and Gillespie note finding a large fragment of a ceramic vessel that Vivian had excavated almost twenty years prior (Citation1979, 6). Often, it was clear that Vivian had not fully excavated the rooms. Driven by new research questions, these previously unexcavated contexts offered the opportunity for Chaco Project staff to apply new methodological techniques and sampling strategies, like screening excavated fills and collecting pollen and macrobotanical samples.

Comparing interpretations

Vivian’s excavations and those of the Chaco Project had vastly different goals. Vivian’s excavations were exploratory and preliminary, meant primarily to open rooms for visitation, whereas Akins and Gillespie were striving for comprehensive documentation and recovery to test hypotheses about Chacoan life. The latter resulted in detailed studies of architectural construction sequences (Gillespie Citation1980), and the systematic screening of fill allowed for more thorough recovery of artifacts that were either missed by Vivian or perhaps thought to be unworthy of recovering, like chipped stone (Cameron Citation1980) and macrobotanical remains (Toll Citation1985). To assess these two very different excavation projects, we draw comparisons between the only component of Una Vida’s excavations that has been reported for each excavation: the avifaunal remains ().

Table 1. Comparisons of faunal assemblages from the excavations of Una Vida. NR = Not Recorded.

In a.d. 1961, Lyndon Hargrave, a talented ornithologist who established the field of archaeo-ornithology, prepared a brief report of the wild bird remains from Vivian’s excavations of Una Vida. In this report, he identified the remains of a thick-billed parrot (one of only three such birds found in Chaco Canyon), along with instances of various species of hawk, eagle, crane, quail, and owl (Hargrave Citation1961). This report was part of Hargrave’s ambitious survey of avifaunal remains throughout the U.S. Southwest in his efforts to develop the discipline of archaeo-ornithology, in which Hargrave was keen on using archaeological assemblages as a tool for reconstructing historical ecologies of the region (Taylor and Euler Citation1980, 479). Hargrave did not report turkey remains from Una Vida, though he did identify them in the course of his analysis. He insisted that a separate report dedicated to turkeys was forthcoming. In explaining his omission of turkeys from a similar report on the remains of wild birds from Aztec Ruin, he wrote in a letter to the National Monument’s superintendent: “I did not list the Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) in the above as a wild bird to contribute to our study of the prehistoric ecology of the area since I consider the turkey a cultural product, important to the economy of the people and not an ecological factor of the area” (CRA #000628, emphasis added). Although no formal report on the turkeys of Una Vida was ever produced, a handwritten tally of element counts by species, archived at the CCNHP Archive and probably made by Charmion McKusick, reports 56 turkey bones (included in the tallies for ) (CRA #001650).

As with any excavated assemblage, the avifaunal assemblage of Una Vida has been shaped by the decisions, priorities, and recovery methods chosen by each excavator or project. The results of the Chaco Project’s 1979 excavation reveal a different picture than those of Vivian’s excavations as reported by Hargrave. First, Akins (Citation1982) analyzed and reported all excavated faunal remains, yielding a combined total of 3374 bones from cottontail, jackrabbit, deer, mountain sheep, coyote, bobcat, and large numbers of rodents like squirrels and pocket gophers. This analysis illustrates a more complete picture of daily life at Una Vida. They documented proveniences, pathologies, bioturbation, and instances of human processing like butchering, burning, and one instance of pigment-staining. The numbers reported by Akins include both material from previously excavated contexts as well as material from Vivian’s backdirt. This is clearly illustrated in the avifaunal assemblages. The higher representation in the Chaco Project material of small birds like horned lark, blackbirds, and sparrows, all of which have very small bones, highlights that the Chaco Project employed screening of backdirt at Una Vida. Their near absence in the assemblage excavated by Vivian and analyzed by Hargrave suggests that Vivian instead may have only hand-collected bone.

Another difference between these assemblages is that 62.8% of the Chaco Project’s reported number of identified specimens (NISP) could only be identified as Aves sp., while Hargrave did not report any indeterminate bird remains. All avifaunal identifications for the Chaco Project were made by trained faunal analysts and those trained in archaeo-ornithology, suggesting that the indeterminate designations do not represent a lack of skill or access to suitable reference material but instead that Vivian prioritized the collection of large, diagnostic specimens rather than the collection of all bone.

These differences become more startling when compared with Bishop’s (Citation2019) recent reanalysis of all bird bone excavated from Chaco Canyon (see ). In contrast to the modest number of avifaunal specimens reported from both Vivian’s and the Chaco Project’s excavations (160 elements), Bishop’s reanalysis reported an astounding 1404 specimens from Una Vida (Bishop Citation2019, table 5.3). Of these, 1333 are identified as turkey, 1316 of which were excavated by Vivian but were not reported.Footnote3 That 95% of all bird bones recovered from Una Vida were turkey means that more turkey remains were recovered from Una Vida than from any other site in the entire canyon, both proportionate to other avifaunal remains and in overall quantity (Bishop Citation2019, 188).

Una Vida’s abundance of turkey suggests two possibilities. On one hand, turkeys may have played a larger role at Una Vida than at other sites in the canyon. If so, Hargrave’s lack of attention to the turkey remains and their absence in his report would lead readers to a completely opposite conclusion, that turkeys, in fact, were barely present at the site. On the other hand, the abundance of turkeys in the Una Vida avifaunal assemblage may be heavily influenced by a lack of the collection by Vivian of the remains of other, perhaps smaller, less diagnostic, or less “exciting” birds. These two possibilities that may account for the high representation of turkeys at Una Vida are not mutually exclusive, but both are influenced by decisions made by excavators about which elements belong in the archaeological record and which belong in backdirt. Vivian likely prioritized the collection of large, diagnostic specimens, including a large number of turkey remains, but may have either unintentionally missed the remains of other, smaller birds or decided against their collection. These choices led to the likely overinflation, at least in part, of the abundance of turkey, while completely obscuring the potential importance of other birds.

The absence of a report written by Vivian or of a commissioned faunal analysis and the personal interests of Hargrave created a picture very different from that presented by an analysis of the full assemblage. Vivian’s excavations, as reported by Hargrave, suggest that the residents of Una Vida had strong preferences for exotic, visually striking, and difficult-to-procure species of birds. The omission of Una Vida’s most abundant bird—the turkey—in Hargrave’s report paints a specific picture of the past. Turkeys have served a significant role in the social, economic, and ceremonial lives of people for nearly 2000 years in the U.S. Southwest (e.g., Lipe et al. Citation2016, Citation2020). Indeed, one turkey at Una Vida was intentionally placed on the floor of Room 63 (Bishop Citation2019, 216). The Pueblo World, both today and in the past, is one with marked relationships with birds (e.g., Bishop Citation2019; Schwartz, Plog, and Gilman Citation2022), so the conspicuous use and deliberate deposition of such species is not surprising. However, the emphasis on the most conspicuous and perhaps ritualized elements of life paints a very curated picture. Comparatively, Akins and Gillespie’s excavations reveal the daily lives and diets of Una Vida’s residents, reporting the entire faunal assemblage with notable amounts of cottontail, jackrabbit, deer, and pocket gopher with evidence of butchering and “cooking brown” (Akins Citation1982, 6–7).

Broader interpretations of Chaco society often mirror the distinctions in the emphasis on the Una Vida case study, with some archaeologists focusing on evidence of religious practice and others highlighting economic and subsistence aspects. While both can be laudable goals, issues arise when these interpretations are taken as broadly representative of the data. Ultimately, this case study demonstrates that backdirt remains an important material archive of the past motives and assumptions structuring archaeological decision-making. How avifaunal remains (and those of other animals) were or were not reported by each project speaks to what project members and analysts considered to be important. Comparing these assemblages provides an opportunity to reflect on the motivations that drove each project and the role that backdirt and its varying definitions play in influencing or potentially limiting our interpretations of human behavior in the past.

Moving Forward: The Place of Backdirt in Archaeological Praxis

Key differences in collection, recording, curation, and analysis approaches continue to complicate our understanding of core tenants of Chacoan history, and interpretations of population estimates, great house function, and agricultural potential remain highly contentious. The history of practices related to backdirt production in Chaco Canyon speak to the importance of increasing consideration for how we define backdirt, as well as the potential for reinterpretations given a clearer understanding of these assumptions. As an analytical entity, backdirt provides an opportunity to revisit what was initially deemed irrelevant. Not only does its analysis offer us a chance to better understand the historical frameworks that guided earlier research, as demonstrated by the Una Vida case study, but it also offers an opportunity to revise and bolster our interpretations of past places and peoples.

In addition to reinterpretations of the history of Chaco Canyon itself, recognition of the decisions that have shaped and continue to shape the archaeological record can contribute to the correction of past issues in whose stories are heard and told. Feminist critiques of archaeology have long highlighted the genderless past world that has been created by androcentric research agendas (e.g., Gero and Conkey Citation1991; Moen Citation2019; Wylie Citation1997), and work in Chaco Canyon is no exception. Ground stone, as tools associated with women’s work, has been under-collected, under-curated, and under-studied in the Southwest (Heitman Citation2016; see also Lyons et al. Citation2023). This has had a dramatic impact on the interpretation of gender roles in Chaco history. Drawing from documented Pueblo gender roles, Heitman (Citation2016, 484) utilized “resuscitated data” from the CRA to demonstrate the overwhelming ubiquity of material evidence for women’s contributions to socio-religious life and the systematic relegation of evidence of these contributions, in the form of ground stone, to backdirt. The routine discard of ground stone is well illustrated in archival photographs showing an overwhelming abundance of manos and metates, which were sometimes even used by projects to create commemorative slogans for photographs (Heitman Citation2016, 481, see fig. 6). This relegation likely reflects multiple decisions regarding the value of the information available from ground stone at the time, the cost of transporting and storing large and heavy pieces, and a general belief that the material remains of women’s lives would not speak to broader questions of sociopolitical organization.

The creation of the archaeological record has historically prioritized Western scientific models for data collection, classification, and interpretation. For Indigenous groups who are encountering their own culture through an archaeological lens, these processes can serve to distance communities from their own pasts. However, Indigenous perspectives are increasingly calling archaeology’s supposed objectivity into question as part of broad disciplinary turns to increasingly collaborative methods.Footnote4 For example, Borck and colleagues (Citation2020) demonstrate crucial differences in how Indigenous potters and non-Indigenous archaeologists construct taxonomies of pottery fragments, while Fladd, Hedquist, and Adams (Citation2021) demonstrate that the term “trash” is a misleading notion that does not align with, and ultimately obscures, Hopi ontologies of ancestral places.

Indigenous perspectives are increasingly being centered in Chaco archaeology, adding new understandings to Chaco’s role in Indigenous history (e.g., Van Dyke and Heitman Citation2021) and reminding us that excavation projects and their resulting museum collections are not neutral (e.g., Cortez et al. Citation2021). As outlined in this paper, collection decisions in early Chaco excavations reflected museum preferences, while later projects emphasized sampling strategies of materials deemed to be best suited for archaeological reconstructions of the past. However, recent projects focused on centering Indigenous perspectives illustrate the multiple dimensions of culturally-, historically-, and situationally-contingent meanings embedded in materials, songs, histories, and landscapes that cannot be fully understood using traditional archaeological approaches rooted in Western science alone (e.g., Hanson, Seowtewa, and Hopkins Citationin press; Hanson et al. Citation2022; Hopkins et al. Citation2019; King Citation2003; Van Dyke and Heitman Citation2021). Inevitably, all projects have overlooked meaningful materials in their collection strategies and have failed to ask significant questions due to the positionality of the researchers themselves. As such, appropriate and ethical utilization of existing datasets requires a firm grasp of the decisions involved in creating the archaeological record, particularly as they are rooted in and guided by the historically- and culturally-situated contexts of research and researchers. We urge researchers to consider backdirt in contexts beyond the excavation process itself. Museums and researchers continue to make decisions about what materials to curate, prioritize, and examine in detail. Deaccessioned collection materials can be viewed as the “backdirt” of museum work, and unanalyzed objects become the “backdirt” of research projects. All of these practices contribute to the creation of the archaeological record as a tool for the interpretation of the past.

Understanding the creation of the archaeological record becomes critical as research increasingly prioritizes the reanalysis of existing collections of materials initially deemed unimportant by original excavators using new scientific techniques. As large, open access databases like the Chaco Research Archive (chacoarchive.org) and cyberSW (cybersw.org) make way for detailed analyses of material distributions (e.g., Bishop Citation2019; Bishop and Fladd Citation2018; Bishop, Fladd, and Watson Citation2023; Giomi and Peeples Citation2019; Hanson Citation2023; Mattson Citation2016; Weiner Citation2018) and expansive studies of social interactions (e.g., Mills et al. Citation2018), it becomes imperative that we understand that the decisions made throughout the research process—from the field, to labs, museums, and databases—determine what is knowable. The reexamination of backdirt not only permits reinvigorated studies of archaeological histories but also encourages us to question how these histories are created by archaeologists and more critically examine the decisions we make today regarding what is and is not backdirt within our research.

While we focus our attention on Chaco archaeology in this paper, the study of backdirt offers great value elsewhere, especially to provide training opportunities for students. As excavation-intensive field schools become increasingly uncommon and the discipline embraces low-impact approaches to archaeology like survey, remote sensing, and the reanalysis of museum collections (Comer Citation2020), projects focusing on the re-excavation of backdirt may provide an opportunity for students to develop the tactile skills of excavation, as well as training in the study of museum collections and the critical analysis of knowledge production, all while minimizing the impacts on the in situ archaeological record.

Ultimately, understanding the motives and goals that have guided the production of backdirt encourages us to consider the value systems that are prioritized in our work. Moving forward, we argue that backdirt is a unique space where Indigenous, feminist, and archaeological research needs might be met on a case-by-case basis (see also Van Dyke Citation2020). Engaging with backdirt as an analytical entity provides a fruitful avenue for a new wave of archaeological scholarship that considers the ways in which we create historical realities. By understanding past archaeological practices and the historical motives that guided them, we can position future work to accept the limitations of the archaeological record while embracing the wealth of potential that still exists in historic data, museum collections, and previously excavated sites.

Acknowledgements

We thank Allison Mickel for extending an invitation to participate in this special issue and for their support throughout this process. Thank you to Brenna Lissoway for providing access to archival materials from the National Park Service Archives. We also thank an anonymous reviewer whose suggestions strengthened this paper. Finally, we thank Steve Plog and Carrie Heitman for their work on the Chaco Research Archive. All errors are our own.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kelsey E. Hanson

Kelsey E. Hanson (M.S. 2016, Illinois State University) is a Ph.D. Candidate in the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona. Her research primarily focuses on technologies of human expression and pigment technology analysis, as well as critical analyses of archaeological praxis and community-centered scholarship in the U.S. Southwest.

Samantha G. Fladd

Samantha G. Fladd (Ph.D. 2018, University of Arizona) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology and Director of the Museum of Anthropology at Washington State University in Pullman, WA. Her research interests include social identity, room closure practices, the history of archaeology, and community-engaged research and museum practices.

Sarah E. Oas

Sarah E. Oas (Ph.D. 2019, Arizona State University) is a Data Specialist working with the cyberSW database at Archaeology Southwest in Tucson, Arizona. Her research focuses on the complex relationships between plants and people including foodways, cuisine, and food sovereignty.

Katelyn J. Bishop

Katelyn J. Bishop (Ph.D. 2019, University of California, Los Angeles) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her work focuses on human-animal relationships, particularly the role of birds, in North and Central America, collections-based and archival research, and the use of historic legacy data.

Notes

1 In the midst of the aforementioned institutional tensions, Edgar L. Hewett (Citation1936, 32) who directed a series of University of New Mexico field schools in Chaco Canyon, chastised the National Geographic Society’s excavations of Pueblo Bonito, accusing them of merely re-excavating Pepper’s backdirt. Judd (Citation1954, 18) describes Hewett’s statement as an explicit attempt to belittle the National Geographic Society’s project and maintains that they “carted away the excess dirt and rock the Hyde Expeditions had thrown out of their excavations” before initiating their own excavations in other portions of Pueblo Bonito.

2 Unfortunately, the success of this project was short lived, as much of the backdirt-fortified erosion control features were washed away after a summer storm (Chauvenet Citation1935, 17).

3 Hargrave did taxonomically identify many of the turkey remains excavated by Vivian, as evidenced by notations in museum catalogs, as well his preparation of typewritten and handwritten “Archaeo-Ornithology cards,” which he made for nearly every bird bone that he analyzed.

4 This approach has been made most explicit by the non-profit organization Archaeology Southwest, who have coined the term “Preservation Archaeology” to encapsulate an ethos of holistic inquiry through low-impact methods and a dedication to site protection, conservation, and collaboration with multiple stakeholders (Doelle Citation2012).

References

- Adams, E. C. 2002. Homol’ovi: An Ancient Hopi Settlement Cluster. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Akins, N. J. 1982. “Analysis of the Faunal Remains from Recent Excavations at Una Vida.” Ms. on file, NPS Chaco Culture NHP Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Akins, N. J., and W. B. Gillespie. 1979. “Summary Report of Archaeological Investigations at Una Vida, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico.” Ms. on file, National Park Service Chaco Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Atalay, S. 2016. “Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice.” In Indigenous Archaeologies, edited by M. Bruchac, S. Hart, and H. Martin Wobst, 79–85. New York: Routledge.

- Bawaya, M. 2007. “Curation in Crisis.” Science 317 (5841): 1025–1026.

- Binford, L. R. 1962. “Archaeology as Anthropology.” American Antiquity 28 (2): 217–225.

- Bishop, K. J. 2019. Ritual Practice, Ceremonial Organization, and the Value and Use of Birds in Prehispanic Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, 800-1150 CE. Los Angeles: University of California.

- Bishop, K. J., and S. G. Fladd. 2018. “Ritual Fauna and Social Organization at Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon.” Kiva 84 (3): 293–316.

- Bishop, K. J., S. G. Fladd, and A. S. Watson. 2023. “Reassessing Nearly a Century of Faunal Remains and Excavation Data from Chaco Canyon.” In Pushing Boundaries: Proceedings of the 2018 Southwest Symposium, edited by S. Nash, and E. Baxter. Louisville: University Press of Colorado.

- Borck, L., J. C. Athenstädt, L. A. Cheromiah, L. D. Aragon, U. Brandes, and C. L. Hofman. 2020. “Plainware and Polychrome: Quantifying Perceptual Differences in Ceramic Classification Between Diverse Groups to Further a Strong Objectivity.” Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology 3 (1): 135–150.

- Cameron, C. M. 1980. “Chipped Stone at Site 29SJ391—Una Vida.” Ms. on file, NPS Chaco Culture NHP Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Cameron, C. M. 2005. “Exploring Archaeological Cultures in the Northern Southwest: What Were Chaco and Mesa Verde?” Kiva 70 (3): 227–253.

- Chauvenet, W. 1935. “Erosion Control in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico for the Preservation of Archaeological Sites.” Master’s Thesis. University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Comer, D. C. 2020. “Conservation and Preservation in Archaeology in the Twenty-First Century.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by C. Smith, 2629–2635. New York: Springer.

- Cortez, A. D., D. A. Bolnick, G. Nicholas, J. Bardill, and C. Colwell. 2021. “An Ethical Crisis in Ancient DNA Research: Insights from the Chaco Canyon Controversy as a Case Study.” Journal of Social Archaeology 21 (2): 157–178.

- Crown, P. L. 2016. The Pueblo Bonito Mounds of Chaco Canyon: Material Culture and Fauna. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Crown, P. L. 2020. The House of the Cylinder Jars: Room 28 in Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Crown, P. L., and W. H. Wills. 2018. “The Complex History of Pueblo Bonito and its Interpretation.” Antiquity 92: 890–904.

- Deloria, V. Jr. 1969. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. Macmillan, New York.

- Doelle, W. H. 2012. “"What is Preservation Archaeology?”.” Archaeology Southwest 26 (1): 1–3.

- Fladd, S. G., S. L. Hedquist, and E. C. Adams. 2021. “Trash Reconsidered: A Relational Approach to Deposition in the Pueblo Southwest.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 61: 101268.

- Fowles, S., and B. J. Mills. 2017. “On History in Southwest Archaeology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Southwest Archaeology, edited by B. J. Mills, and S. Fowles, 3–71. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gero, J. M., and M. W. Conkey. 1991. Engendering Archaeology. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Gillespie, W. B. 1980. “Architectural Development at Una Vida, Chaco Canyon, N.M.” Ms. on file, NPS Chaco Culture NHP Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Giomi, E., and M. A. Peeples. 2019. “Network Analysis of Intrasite Material Networks and Ritual Practice at Pueblo Bonito.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 53: 22–31.

- Hanson, K. E. 2023. “Color and Chaco Performance: Spatial Histories of Blue-Green Paint Production at Pueblo Bonito.” Kiva 89 (2): 117–138.

- Hanson, K. E., S. Baumann, T. Pasqual, O. Seowtewa, and T. J. Ferguson. 2022. ““This Place Belongs to Us”: Historic Contexts as a Mechanism for Multivocality in the National Register.” American Antiquity 87 (3): 439–456.

- Hanson, K. E., O. Seowtewa, and M. P. Hopkins. In Press. “Ts’oya and the Multivalency of Color in the Archaeological Record.” In Attributes to Networks: Doing Archaeology at Multiple Scales with Multiple Voices. Proceedings of the 2023 Southwest Symposium, edited by J. Habicht Mauche and M. McBrinn. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Hargrave, L. L. 1961. “Wild Birds Identified from Bones from Una Vida Pueblo in Chaco Canyon National Monument.” Ms. on file, National Park Service, Western Archaeological and Conservation Center, Tucson.

- Heitman, C. C. 2011. “Architectures of Inequality: Evaluating Houses, Kinship and Cosmology in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, A.D. 800-1200.” PhD Dissertation, University of Virginia.

- Heitman, C. C. 2016. ““A Mother for All the People”: Feminist Science and Chacoan Archaeology.” American Antiquity 81 (3): 471–489.

- Hewett, E. L. 1936. The Chaco Canyon and its Monuments. Handbooks of Archeological History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico and School of American Research.

- Hopkins, M. P., O. Seowtewa, G. L. Berlin, J. Campbell, C. Colwell, and T. J. Ferguson. 2019. “Anshe K’yan’a and Zuni Traditions of Movement.” In The Continuous Path: Pueblo Movement and the Archaeology of Becoming, edited by S. Duwe, and R. Preucel, 60–77. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Judd, N. M. 1954. The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 124. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Judge, W. J. 1979. “The Development of A Complex Ecosystem in the Chaco Basin, New Mexico.” In Proceedings of the First Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks, edited by R. M. Linn, 901–906. Washington D.C: National Park Service Transactions and Proceedings 5.

- Judge, W. J., J. D. Schelberg (editors). 1984. Recent Research on Chaco Prehistory. Reports of the Chaco Center, No. 8. Division of Cultural Research, National Park Service, Albuquerque.

- King, T. F. 2003. Places That Count: Traditional Cultural Properties in Cultural Resource Management. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Lekson, S. 1984. Great Pueblo Architecture of Chaco Canyon. Publications in Archeology 18B, Chaco Canyon Studies. Division of Cultural Research, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Albuquerque.

- Lekson, S., ed. 2006. The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon: An Eleventh-Century Pueblo Regional Center. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Lekson, S. 2018. A Study of Southwestern Archaeology. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Lipe, W. D., R. K. Bocinsky, B. S. Chisholm, R. L. D, M. Dove, R. G. Matson, E. Jarvis, K. Judd, and B. M. Kemp. 2016. “Cultural and Genetic Contexts for Early Turkey Domestication in the Northern Southwest.” American Antiquity 81: 97–113.

- Lipe, W. D., S. Tushingham, E. Blinman, L. Webster, C. T. LaRue, A. Oliver-Bozeman, and J. Till. 2020. “Staying Warm in the Upland Southwest: A “Supply Side” View of Turkey Feather Blanket Production.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 34.

- Lyons, P. D., D. L. Burgess, V. W. Johns, and M. M. Marshall. 2023. “Corn-Grinding Stations at Point of Pines.” In Collected Papers from the 21st Biennial Mogollon Archaeology Conference, November 4-5, 2022, edited by L. C. Ludeman, and M. W. Diehl. Las Cruces, New Mexico: Friends of Mogollon Archaeology.

- Marden, K. 2011. “Taphonomy, Paleopathology and Mortuary Variability in Chaco Canyon: Using Bioarchaeological and Forensic Methods to Understand Ancient Cultural Practices.” PhD Dissertation, Tulane University.

- Mathien, F. J. 2005. “Culture and Ecology of Chaco Canyon and the San Juan Basin. Publications in Archaeology.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Santa Fe.

- Mattson, H. V. 2016. “Ornaments as Socially Valuable Objects: Jewelry and Identity in the Chaco and Post-Chaco Worlds.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 42: 122–139.

- Mills, B. J. 2023. “From Frontier to Centre Place: The Dynamic Trajectory of the Chaco World.” Journal of Urban Archaeology 7: 215–252.

- Mills, B. J., M. A. Peeples, L. D. Aragon, B. A. Bellorado, J. J. Clark, E. Giomi, and T. C. Windes. 2018. “Evaluating Chaco Migration Scenarios Using Dynamic Social Network Analysis.” Antiquity 92 (364): 922–939.

- Moen, M. 2019. “Gender and Archaeology: Where Are We Now?” Archaeologies 15: 206–226.

- Moorehead, W. K. 1906. A Narrative of Explorations in New Mexico, Arizona, Indian, etc. Department of Archaeology, Phillips Academy, Bulletin 3. Andover, MA. The Andover Press

- Neitzel, J. 2003. “Artifact Distributions at Pueblo Bonito.” In Pueblo Bonito: Center of the Chacoan World, edited by J. Neitzel, 107–126. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Pepper, G. H. 1920. “Pueblo Bonito.” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. New York.

- Plog, S. 2015. “Understanding Chaco: Past, Present, and Future.” In Chaco Revisited: New Research on the Prehistory of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, edited by C. C. Heitman, and S. Plog, 3–29. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Plog, S. 2018. “Dimensions and Dynamics of Pre-Hispanic Pueblo Organization and Authority: The Chaco Canyon Conundrum.” In Puebloan Societies: Cultural Homologies in Time and Space, edited by P. Whiteley, 237–260. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Plog, S., and C. Heitman. 2010. “Hierarchy and Social Inequality in the American Southwest, A.D. 800-1200.” PNAS 107 (46): 19619–19626.

- Plog, S., C. C. Heitman, and A. S. Watson. 2017. “Key Dimensions of the Cultural Trajectories of Chaco Canyon.” In The Oxford Handbook of Southwest Archaeology, edited by B. Mills, and S. Fowles, 285–306. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Plog, S., and A. S. Watson. 2012. “The Chaco Pilgrimage Model: Evaluating the Evidence from Pueblo Alto.” American Antiquity 77 (3): 449–477.

- Roberts, F. H. H., Jr. 1929. “Shabik’eshchee Village, a Late Basket Maker Site in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico.” Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 92. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Scarborough, V. L., S. G. Fladd, N. P. Dunning, S. Plog, L. A. Owen, C. Carr, K. B. Tankersley, J. P. McCool, A. S. Watson, E. A. Haussner, B. Crowley, K. J. Bishop, D. L. Lentz, and R. Gwinn Vivian. 2018. “Water Uncertainty, Agricultural Canals, and Ritual Predictability at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico.” Antiquity 92 (364): 870–889.

- Schwartz, C. W., S. Plog, and P. A. Gilman. 2022. Birds of the Sun: Macaws and People in the U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest. University of Arizona Press.

- Shiner, J., and G. Vivian. 1960. “The 1960 Stabilization of Una Vida Ruin, Chaco Canyon National Monument, New Mexico.” Stabilization report on file in the NPS Chaco Culture NHP Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

- Snead, J. P. 2001. Ruins and Rivals: The Making of Southwest Archaeology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Svare, M. E. 2015. “Speaking in Circles: Interpretation and Visitor Experience at Chaco Culture National Historic Park.” MA thesis, University of New Mexico.

- Taylor, W. W., and R. C. Euler. 1980. “Lyndon Lane Hargrave, 1896–1978.” American Antiquity 45 (3): 477–482.

- Toll, M. S. 1985. “Flotation and Macrobotanical Remains at Two Chacoan Greathouses: Una Vida (29SJ391) and Kin Nahasbas (29SJ392).” Ms. on file, NPS Chaco Culture NHP Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Truell, M. L. 1992. “Excavations at 29SJ 627, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, Vol. I: The Architecture and Stratigraphy.” Reports of the Chaco Center, No. 11. National Park Service, Santa Fe.

- Van Dyke, R. M. 2020. “Indigenous Archaeology in a Settler-Colonist State: A View from the North American Southwest.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 53 (1): 41–58.

- Van Dyke, R. M., and C. C. Heitman. 2021. The Greater Chaco Landscape: Ancestors, Scholarship, and Advocacy. Louisville: University Press of Colorado.

- Vivian, R. G., and S. G. Fladd. In Press. Capturing Water: Puebloan Resilience and Agricultural Sustainability in Chaco Canyon. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Watson, A., A. Holeman, S. Fladd, K. Bishop, M. Conger, and S. Morrow. 2014. “Damage Assessment and Data Recovery at 29SJ2384, Roberts’ Great House, July-August 2013.” Report submitted to the National Park Service, Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

- Weiner, R. S. 2018. “Sociopolitical, Ceremonial, and Economic Aspects of Gambling in Ancient North America: A Case Study of Chaco Canyon.” American Antiquity 83 (1): 34–53.

- Wills, W. H., D. E. Love, S. Smith, K. Adams, M. Palacios-Fest, P. L. Crown, W. B. Dorshow, B. Murphy, and H. Mattson. 2015. “Reopening National Geographic Society Trenches at Pueblo Bonito: Stratigraphic Overview.” Ms. on file, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Windes, T. C. 1987. “Research Goals and Methods.” In Investigations at the Pueblo Alto Complex, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico 1976-1979, edited by T. C. Windes, pp. 51-76. Publications in Archaeology 18F, Chaco Canyon Studies. National Park Service, Sante Fe.

- Wylie, A. 1997. “The Engendering of Archaeology Refiguring Feminist Science Studies.” Osiris, 2nd Series 12:80–99.