ABSTRACT

This paper presents a study of the San Isidro archaeological site in El Salvador, providing significant insights into the development of Preclassic settlements in the region. Through analysis of ceramic sequences, radiocarbon dating, and excavations, the study traces the site’s evolution and its contextual significance within Mesoamerican and Isthmo-Colombian spheres. We report on the discovery of over 50 mounds constructed around 400 b.c., indicating the emergence of a complex social structure at that time. The unearthed artifacts, including jade objects and Bolinas-type figurines, suggest cultural exchange with often distant regions of Mesoamerica and the Isthmo-Colombian area. This research not only contributes to understanding the chronological and geographic development of San Isidro but also highlights the site’s role in broader Preclassic Mesoamerican cultural dynamics. Our findings challenge existing perceptions of cultural peripherality and emphasize the need for nuanced regional studies in reconstructing ancient Central American history.

Setting

After approximately two centuries of its existence as a science, archaeology nowadays covers most of the world. However, it does so unevenly. There are significant portions of entire continents where our knowledge of the ancient past is profound, and archaeologists can now focus on minutiae of past political systems, worldviews, and rituals. Other places receive much less attention and intellectual effort. The reasons for such a relative neglect aside, the resulting spottiness of an imaginary archaeological map of the world inevitably influences the interpretations and models of ancient life constructed by modern scholarship in two interlaced ways. On the one hand, the available data from the “islands of knowledge”—be it particular sites or entire countries or even geographical areas—is often used to fill the gaps in the blank spots. On the other hand, the less-studied areas, by contrast, may appear devoid of complexity and agency and end up relegated to the category of “peripheries.”

The archaeology of El Salvador faces a significant challenge due to a scarcity of primary data. Most regional syntheses rely on detailed information from only a few sites, extrapolating their conclusions to extensive areas with minimal archaeological coverage. This extrapolation is somewhat justified by the fact that El Salvador is one of the smallest countries in the region; thus, in this case, “extensive areas” refers to expanses of hundreds, rather than thousands, of square kilometers.

On the other hand, the pre-contact lands that are now El Salvador straddled the fuzzy and poorly defined boundary between Mesoamerican and non-Mesoamerican areas.Footnote1 The predictability of cultural patterns in such a scenario is limited, especially given the fact that farther southeast, where Central America becomes a narrow funnel concentrating the movement of people and ideas, a mosaic of various traditions was much denser than that known from Mesoamerica (cf. Cooke Citation2021).

The spotty “archipelago of knowledge” results in a grossly oversimplified image of the past that does not account for entire cultural processes that could in fact dramatically change our understanding of the liminal zone between two large cultural areas: Mesoamerica in the west and the Isthmo-Colombian Area in the east. Among the unknowns are such fundamental questions as: who were the inhabitants of those lands? Were they aware of living in a transition sphere? How, if at all, did they cope with cultural pressures? Were they, as is often implied, peripheral and passive consumers of cultures developed somewhere else? Or did they actively and independently shape their own, regional traditions?

Large amounts of intellectual effort have been invested in attempts to attribute Salvadoran sites and areas to known, predefined cultural entities, such as the Maya, the Olmecs, and the Pipil, and to less known groups, such as Lenca, Xinca, or Cacaopera (Ashmore Citation2014; Fowler Citation1989; Sampeck Citation2010; Sharer Citation1978; Sheets Citation2002; White Citation2009). However, these efforts appear to be perpetually destined to fail for three reasons. First, most of the relevant data is forever lost underneath the little-controlled sprawl of modern architectural development in what is the most densely occupied country of both Americas. Second, the unambiguous, clear indicators of cultural attribution known from Mesoamerica, such as writing systems, are largely absent in El Salvador. And finally, the very assumption that ancient settlements in the modern territory of El Salvador were by default created and managed by homogeneous ethnolinguistic or cultural groups—a calque from the more clearly defined and historically documented Isthmo-Colombian area—is less than sound.

Therefore, much more nuanced datasets are required to reconstruct El Salvador’s past with an acceptable level of plausibility. In this article, we contribute one such dataset—a result of the first few seasons of work at a large, early site from the western portion of the country—that provides much needed radiocarbon, ceramic, and overall archaeological data. We attempt to fit this dataset within local and regional contexts of early development of complex societies based on stylistic comparisons and detectable connections with both large spheres that surround our area of interest: Mesoamerica to the west and the Isthmo-Colombian Area to the east.

San Isidro Archaeological Site

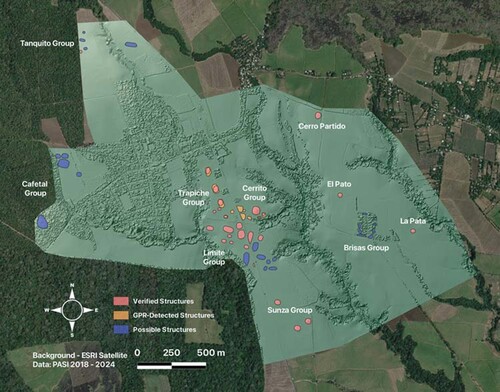

Prior to the ongoing investigation led by the authors, the archaeological site of San Isidro was one of several hundred registered but unexplored sites in the country. The site extends over sugarcane plantations in the Sonsonate Department, some 50 km west of El Salvador’s capital, on the outskirts of a modern town of the same name. The ancient settlement occupied an advantageous location at the junction of the Río Grande-Sensunapán and Zapotitán Valleys that connect the Pacific coast with rich and fertile hinterland, an access otherwise restricted for more than 100 km in either direction by the Apaneca and Bálsamo mountain ranges ().

In the first two seasons, conducted in 2018 and 2019, the investigation revealed the unusually large size of the settlement, encompassing more than 50 still-visible mounds and platforms scattered over some 6 km2 of a gently sloping plateau at the foot of the Santa Ana volcanic complex. These mounds assume a variety of shapes, from elongated through circular and oval to rectangular, measuring between just a few to over 60 m in diameter, or diagonal, and rising between less than a half to well over 10 m above the surrounding terrain ().

Remote sensing techniques, including Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), electric resistivity, and magnetometry, were employed in 2021 within the presumed center of the settlement. This corroborated the assumption that there were once more structures than those currently visible, as vestiges of several seemingly circular mounds, some nearly 50 m in diameter, were detected on radargrams but had been completely obliterated from the modern surface by heavy agricultural machinery. The geophysical survey also identified an extensive anomaly 0.75–1.25 m below the average surface. Archaeological verification revealed this anomaly to be a highly eroded layer of the TBJ, or tierra blanca joven—a stratum of ash from the eruption of the Ilopango volcano sometime between a.d. 430 and 540 (Dull et al. Citation2019; Smith et al. Citation2020). Notably, the TBJ is absent on sloping terrain, including all mounds—both visible and invisible on the surface—as well as the edges of canyons and ravines. It appears to be covering a post-abandonment eolic or erosion stratum rather than a cultural surface. Both of these facts suggest that San Isidro was already abandoned at the time of the eruption (Szymański et al. Citation2022).

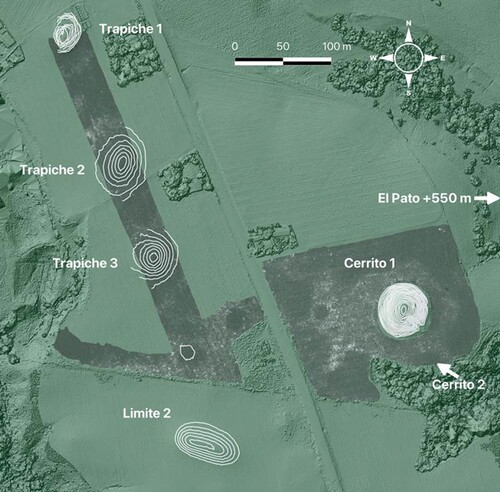

Previously, San Isidro was reported to lack discernible urban patterns or architectural groups. The only alignment of visible structures attesting to any particular site orientation was that of the Trapiche group, 19° west of north. However, upon completion of Digital Terrain Model (DTM) processing, aggregating the GPR-found anomalies, and overlaying the model with contour lines, it became apparent that there are several structures that have been oriented approximately 15° east of north, or 15° south of east—a common pattern in Preclassic Mesoamerica, including such prominent centers as San Lorenzo, Aguada Fenix, and later Teotihuacan (Šprajc Citation2017, 206; Šprajc, Inomata, and Aveni Citation2023). Examples of structures at San Isidro that display that orientation include Trapiche 3 and Cerrito 1, which face each other. Both are oval rather than round, with the shorter axes skewed 15° south of east. At least one elongated structure from the Limite group (Limite 2) to the south is oriented perpendicularly to the previous two, with its shorter axis oriented 15° east from the north-south line. Additionally, edges of the TBJ layer visible in the radargrams around Trapiche 2 and Cerrito 1 demonstrate the outlines of likely structures invisible on the surface that follow similar orientations ().

Figure 3. Center of the site with contour lines over structures and the extent of radargram anomaly overlaid around Cerrito 1 and along the Trapiche group.

Another notable feature of the site plan is its division by several deep ravines with nearly vertical slopes, reaching over 30 m in depth at some points. These ravines likely formed as a result of seasonal rainfall. With no permanent vegetation to cover and consolidate the loose, ashy surface, rainfall easily carves into the subsoils. Over a brief period of five field seasons, project members observed significant advance in the development of small and narrow cavities in the walls of the ravine closest to the Cerrito group, evolving into side ravines of their own. Despite the substantial size of some of those formations, whether they predate, coincide with, or postdate the lifespan of the archaeological site remains uncertain. The current rate of erosion suggests that the ravines may have formed after the site’s abandonment. This proposition gains strength from the observation that internal pedestrian circulation within the settlement would have been considerably complicated if the ravines were pre-existing. Navigating the settlement would have required maneuvering several hundred meters around the ravines to reach places only a few dozen meters away. Alternatively, it would have necessitated the construction of bridges. The lack of relevant data confines this discussion to the realm of speculation, although an interesting discussion on a similar topic in the context of Kaminaljuyu is provided by Jonathan Kaplan (Citation2011, 241–242).

Excavations: Discoveries and Interpretations

Archaeological excavations carried out during the 2021 and 2022 field seasons primarily focused on the most prominent structure of the site, Cerrito 1, which measures approximately 55 m north-south, 50 m east-west, and rises almost 13 m above the surrounding plantation. Additional operations were excavated at nearby structures: Cerrito 2, Trapiche 1, and Pato. Unfortunately, all other visible mounds exhibit severe deterioration and obliteration due to annual mechanized plowing. However, Cerrito 1, Trapiche 1, and Pato, being too large and steep for mechanized cultivation, avoided such damage, albeit with varying degrees of modern intervention and/or destruction.

The summit and higher slopes of Cerrito 1 underwent intermittent manual cultivation of maize, and laurel (Cordia alliodora), eucalyptus (Eucalyptus Spp.), and figs (Ficus americana) were planted along its perimeter in the mid-1990s (). Looter’s trenches are present on its eastern and southeastern sides. Trapiche 1, the closest mound to the modern town, exhibits remnants of an unfinished industrial sugarcane mill and press on its northern and eastern slopes, cutting several meters into the core of the structure. Pato’s summit features two perpendicular stone walls of a 20th century a.d. unfinished water tank and a modern iron observation tower on concrete feet. Despite interventions, these three structures are among the least altered, with damage limited to specific areas, leaving others relatively intact.

Figure 4. Cerrito 1 upon termination of the operations in 2022, with horizontal trenching into the core visible in the center. View towards south.

The archaeological operations aimed to obtain ceramic sequences from structure cores, understand construction techniques and materials, and determine intended layouts and accesses to summits. Gridded, extensive interventions on summits and deep, narrow trenching of slopes were employed where possible.

A consistent result across all operations is the absence of stones in the cores, except for occasional broken grinding stones (manos and metates). None of the excavations, except Cerrito 2, reached the very bottom and center of any mound, leaving the possibility of small stone nuclei within some structures. At least two unexcavated structures in the north of the site had been partially destroyed by an access road of the coffee plantation, and the exposed cuts show a number of medium-sized stones visible in the informal profiles. No formal facades, stairs, or ramps were detected in the excavated structures despite carrying out horizontal interventions for several meters into Cerrito 1 and Trapiche 1. It appears that the mounds were erected by heaping dirt and clay, the latter probably in a very moist state that hardened upon drying. The compacted clay varies in color from dark beige to chocolate brown. Large quantities of eroded domestic pottery sherds and clay figurine fragments were recovered from the cores, suggesting that the construction material came from household middens. The lack of facades does not mean, however, that the mounds were shapeless humps of dirt. Several structures appear to have had angular footprints, turned oval or round only after centuries of erosion. Some also feature longer and shorter sides, a clear indication of axiality in their design.

With the exception of Cerrito 1, all the investigated mounds have a uniform internal structure, lacking discernible construction phases. The absence of external layers of veneer or any other kind of formal facades may result from either a conscious design choice or natural and/or anthropic erosion. This poses a certain challenge during the excavation process, as there is no easily discernible contrast between layers of collapse and the intact core of the structures. The only clear difference is the hardness and compactness of the soil, although the progression of this characteristic from relatively soft and crumbly to hard and sticky is extremely smooth and gradual (). To mitigate the consequences of potential mixing of the two strata, an intermediate layer of arbitrary thickness, ranging from 10–20 cm, was distinguished in each case below the humus and above the compacted and uniform layer of structure fill.

Figure 5. One of the trenches into Trapiche 1 core showing uniform stratigraphy. The trench measures 4 × 3 m, with a 2 × 1 m extension to the north. Contrast modified to highlight the profiles.

Cerrito 1, the largest structure in San Isidro, is the only one that features vestiges of at least one earlier substructure enclosed in the final version of the mound—a pattern common in Mesoamerica. Although the excavation into the substructure is still unfinished, it appears that there had been a smaller version of the pyramidal platform with a modest wattle-and-daub structure on top. At some point, the roof, most likely made of thatch, burned and collapsed, and the walls toppled inward on top of the ashes. The wooden beams that formed frames for the walls then perished, leaving a latticework of perpendicular, tunnel-like voids encased in hardened clay (). Whether a conscious and planned termination, a result of accidental fire, or external or internal violence, this earlier structure was subsequently covered with a larger basal platform that seems to have mainly grown upwards and towards the east, or the back, as if the builders wished to maintain the new façade on the western side in roughly the same line as the older one. Currently, the summit of the final version of the mound is located between 1.2 and 1.6 m above the remnants of the collapsed substructure. No remnants of any buildings on the top of the final structure have been found, which may be attributed to the assumption that the summit, originally located significantly higher—perhaps on yet another small basal platform—eroded away some time in the ensuing 24 centuries. If this interpretation is correct, then all objects discovered within the fill above the collapsed substructure would have been deposited during the process of the enlargement of the mound, as there is no stratigraphic evidence for any posterior intrusions.

Figure 6. An ongoing excavation on the top of Cerrito 1 showing possible remains of an earlier collapsed structure in the northern (left) and eastern (right) profiles.

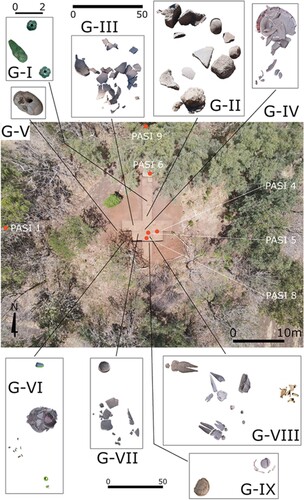

Around the center of the final Cerrito 1 summit, nine concentrations of ceramic vessels and other objects were discovered at varying depths within the fill, though generally not exceeding 0.6 m—thus, above the substructure. The nature and positioning of these finds indicate that they were intentionally deposited as superficial or sub-surface offerings, perhaps marking the perimeter of the most important space on the top, or the perimeter of the hypothetical platform, now obliterated. However, given the fact that particular elements of those concentrations were found in loose arrays with no clear boundaries, often close to or partially overlaying one another, we decided to apply to them a neutral term “groupings” instead of “offerings,” “caches,” or anything in a similar vein that would have steered the readers towards potentially misleading associations. The groupings, described in detail in , are labeled with a letter G and consecutive Roman numerals I–IX starting from the north and west and proceeding towards the south and east (). Positions and absolute depths of particular groupings are given in relation to the center of the mound (Lat. 13.784863 N, Lon. 89.553663 W, 748 masl). Wherever relevant, relative depth measured from the surface—which slopes downwards the further it gets from the center—is also provided.

Figure 7. Top of Cerrito 1 during excavations in 2022. Radiocarbon samples marked with red dots. Grouping scales in centimeters.

Table 1. Description of groupings of objects found at and around the center of Cerrito 1 during the 2021 and 2022 field seasons.

In El Salvador, similarly to much of Mesoamerica, relative typology of ceramics follows the Type-Variety scheme (see Aimers et al. Citation2013). The classifications for western El Salvador that remain in use have been developed mainly by Sharer (Citation1978) and his colleagues (Sharer and Gifford Citation1970), with later contributions and refinements made by Beaudry-Corbett (Citation1983) and Ichikawa and Guerra Clará (Citation2018), among others. Classification of ceramics from San Isidro conforms to that scheme, further divided into broad ceramic complexes, starting with Tok (ca. 1200–900 b.c.), followed by Colos (900–650 b.c.), Kal (650–400 b.c.), Chul (400–200 b.c.), Early and Late Caynac (200–1 b.c. and a.d. 1–200, respectively), and others not relevant to the material found thus far at the site.

The groupings, although found at different depths, are remarkably uniform in terms of ceramic types and relative chronology, generally falling within the moment of transition between the Kal and Chul complexes, placed by Sharer (Citation1978, 3:125) around 400 b.c. (). Some of the found objects (most of the jades, stone fragments, and perhaps some vessels) appear to be randomly deposited or moved from their original position by various processes of mound deterioration, whereas others (stacked vessels and large figurines) almost certainly were found at or very near their original, intended positions. This difference in positioning, coupled with apparent contemporaneity, strengthens the case for the hypothetical platform of reduced horizontal size on the top, with a wide terrace around it, that may have once crowned the mound. Most of the groupings, especially those found at greater depths, may have been deposited within the core of the structure at the time of its construction, while the ones found within humus could have been brought onto the completed structure as offerings and placed on the terrace around the topmost platform or deposited significantly after the building process or even after the structure’s abandonment. Subsequent erosion processes would cause the superstructure to slowly deteriorate onto the terrace, covering it along with the objects deposited there.

Table 2. Ceramic sequence from western El Salvador compared to sequences from other regions mentioned in the text; the table has been limited to periods relevant to the discussion.

The four stacks of vessels are peculiar in their composition, generally mixing types characteristic for two different complexes, representing two consecutive periods: Kal (650–400 b.c.) and Chul (400–200 b.c.). The arrangement of the stacks, with little empty space left within all but the topmost vessels, suggests that the ceramics themselves held significance rather than any content they may or may not have held. All the vessels are of very high quality likely intended for serving rather than preparing foods. It is further noteworthy that each of the stacks features at least one Usulutan ware. At least one stand-alone, complete-but-smashed vessel found upside-down in G-IX also belongs to the same ware. Usulutan pottery is characterized by a cream-colored fine paste, relatively thin walls, and a glossy surface decorated with reddish or orange motifs ranging from shapeless, blurred stains to neat and well-defined geometrical designs. Usulutan wares, probably first manufactured in Preclassic El Salvador and Honduras, were highly valued and traded items, known to be exported to regions as far as northern Guatemala and Belize to the west and Nicaragua and Costa Rica to the east. Currently, it is supposed that the manufacturing process was disseminated along with the actual vessels, as at many of the places outside of the initial Usulutan circulation sphere this kind of ceramics proved to be made of local clays (Goralski Citation2008; Platz Citation2015). In the case of San Isidro, all Usulutan examples are complete vessels found in the groupings or as separate deposits, while only less than a dozen Usulutan sherds were recovered from the shallow depths of the western slope of Cerrito 1. Altogether, six out of the total of 12 complete vessels found within the groupings turned out to be of Usulutan type. Of that number, three are bowls (two flared, one with concave bottom and straight walls) and three jars, including one miniature necked jar about 7 cm tall and 9 cm in diameter.

The figurines found within G-VIII are quite unusual in more than one aspect. The term “Bolinas,” by which they are known in El Salvador, was initially applied to a significant collection of figurines reported from a finca, or farm, of the same name, located on the outskirts of the city of Santa Ana in the westernmost portion of the country. All figurines from Finca Bolinas were tentatively dated to the period of 500–300 b.c. (Boggs Citation1973). Bolinas figurines exhibit a range of sizes, pastes, and iconographic elements. Perhaps the most peculiar within this type is a small number of relatively large (30–40 cm) solid figurines made from a very fine, cream-colored paste that represent broad-hipped, small-breasted women with slightly parted lips, some in different stages of pregnancy (Estrada Citation2017; González Citation2009; López Citation2007). Within this group, a few specimens have detachable heads, and even fewer have articulated arms and legs (Boggs Citation1973, 8). Although roughly 200 specimens are known in total, either from El Salvador or elsewhere, very few of them have been found in context. For that reason, the San Isidro figurines are exceptional. One of the larger figurines with movable heads represents a very rare, if not unique, instance of a male, additionally featuring a delicately carved design on his face representing either a tattoo or a scarification ().

Apart from the groupings, some objects were found at separate locations, seemingly not spatially connected with others. In this category are two small jade beads found west of the center but relatively far apart from each other. Numerous fragments of zoo- and anthropomorphic figurines, including torsos, limbs, and heads of other possible Bolinas specimens, were found throughout the fill of Cerrito 1, as well as in the fill of other mounds.

Perhaps due to the high acidity of the soil or other taphonomic processes, no zooarchaeological datasets have been recovered thus far, save for four small fragments of malacological material too eroded for any useful analyses. The same is true for paleobotanical findings. Additionally, the sticky and lumpy clay that is found uniformly throughout the excavations at San Isidro is not suitable for flotation. Therefore, the interpretations and reconstructions of the past at San Isidro, by necessity, have to rely exclusively on non-perishable remains.

Ceramic Sequence

A prevalent characteristic of the ceramic assemblage at San Isidro is its considerable state of deterioration. Many sherds and complete vessels exhibit severe erosion, making it challenging to identify their types. This erosion may be attributed to the high acidity of local soils, the poor quality of local clays, or a combination of both factors. Out of the total of just over 59,300 ceramic sherds collected from the surface and excavations, only slightly over 3200, or approximately 5.4%, were deemed diagnostic.

Kathryn Sampeck, in her surface survey of the Izalco area, reported an extensive Classic (a.d. 200–900) occupation at San Isidro (Citation2007, 164). However, the research conducted by the San Isidro Archaeological Project has, thus far, failed to recover a single ceramic fragment diagnosed as anything other than Preclassic. All the diagnostic ceramics found at San Isidro, both within excavations and on the surface, belong to Sharer’s typological complexes ranging from Tok to Caynac, dating from 1200 b.c.–a.d. 200 (see ; Sharer Citation1978, vol. 3). Interestingly, most of the Late Preclassic (400 b.c.–a.d. 200) types represented in the San Isidro collection permeate two consecutive complexes: Chul (400–200 b.c.) and the early facet of Caynac (200–1 b.c.). The “pure” Chul and Caynac types are scarce in the dataset.

The most prominent ceramic types at San Isidro include Izcacuyo incised of the Cutumay group (Colos complex, 900–650 b.c.), Lolotique red and Curaren incised of the Lolotique group (Kal complex, 650–400 b.c.), and various types of the Jicalapa and Nohualco groups, characteristic of both Chul and early Caynac complexes (400–200 b.c. and 200–1 b.c., respectively).

A new local type, labeled “El Sunza” by the authors during the 2021 season, is also present among the most frequent ceramics. It features a coarse orange-to-brown paste, thick walls, and incised and punctated decoration. Typologically resembling the Cutumay group of the Colos complex, with similarities in subsequent Kal complex groups Masahuat and Lolotique, El Sunza stands out for its significantly more robust proportions of vessel walls and thick, deep, and firmly marked decorations (). Chronologically, it appears to be a type with a long manufacturing tradition, with roots in the Colos complex and lasting into Kal, during which time its decoration began to lose some of its robustness, finally diluting between Curaren incised and Anguiatu incised.

As the overwhelming majority of ceramics come from the fill or the purported collapse layers of the four excavated structures (Cerrito 1 and 2, Trapiche 1, and El Pato), the sherds represent a broad spectrum of relative dates. The lack of a clear boundary between the collapse and the fill in most cases renders terminus post quem identifications vague.

Nevertheless, some chronological observations can be made. Primarily, the oldest ceramics recovered to date originate from deep levels at the base of Cerrito 1 (over 2 m below the current surface), as well as from fills of the remaining excavated structures. These ceramics predominantly belong to the Colos complex (900–650 b.c.), with a few potentially originating from either Colos or the preceding Tok complex. No exclusive Tok specimens were found. The composition of the structures’ fill, characterized by a high prevalence of broken kitchen wares and other domestic objects, suggests that the construction material was sourced from household middens. The combination of these two observations implies that the inception of occupation at San Isidro can be dated to at least the Colos period, potentially extending back beyond the Tok-to-Colos transition. Two superimposed structures at Cerrito 1 show that there were at least two different moments of labor-intensive construction activity at the site. Currently available data does not reveal how much time separated these episodes.

Radiocarbon Dates: Contextual Problems and Result Interpretations

Organic matter at San Isidro is scarce in archaeological contexts due to the high acidity levels of the local soils. The only suitable samples found during excavations were charcoal pieces collected at Cerrito 1, Cerrito 2, and Trapiche 1. Nine such samples were sent to the Waikato Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory in New Zealand for AMS radiocarbon dating. Eight of these samples provided results, while the single sample from Trapiche 1 (PASI 7) proved insufficient for dating. Additionally, the only sample from Cerrito 2 (PASI 2) and one from Cerrito 1 (PASI 3) returned very recent dates (209 and 160 ± 13 uncalibrated b.p., respectively).

In the case of the PASI 2 sample from Cerrito 2, a low mound located approximately 30 m south of Cerrito 1, the charcoal was obtained from a depth of about 75 cm, a threshold level of the modern plow’s reach. The other recent sample, PASI 3, was collected from the intermediate layer below the humus and fill at the western slope of Cerrito 1. While the mound is too steep for mechanical plowing, its slopes have been intermittently used for maize cultivation employing hand tools, including a modern-day version of the coa (a planting stick common in pre-contact times). This practice was observed by the authors in situ in 2018. Although the stick penetrates the ground no more than 5–10 cm, the roots of the maize specimens at San Isidro reportedly reach depths of about 40 to even 60 cm below the surface. After harvest, limited to the cobs, the stalks are left to dry and then burned to fertilize the soil.

Additionally, the layer of soil immediately below the humus is utilized by the nymphs of cicadas, most likely Diceroprocta belizensis (Sanborn Citation2001), which excavate tunnels often exceeding 15 cm in length. Hence, it is highly likely that the relatively recent charcoal migrated to lower strata of the surface. The remaining six samples, all from Cerrito 1, returned relatively consistent dates, all from the Preclassic period (see ; ). The Conventional Radiocarbon Ages (CRA) were calibrated using OxCal v. 4.4.4.

Table 3. AMS radiocarbon date ranges from Cerrito 1, San Isidro. Date ranges with significantly dominant probability are emphasized with bold font.

The PASI 1 sample was collected from a depth of 1.54 m below the surface at the base of the western slope of Cerrito 1, near the presumed junction of the mound’s collapse layer and a potential plaza floor. While the physical characteristics of both strata are nearly identical (with the lower one exhibiting a slightly lighter chocolate-brown color and increased hardness), there was an unusually high concentration of ceramic sherds and fragmented figurines precisely at the presumed boundary between the layers. Thus, the immediate context of the charcoal sample suggests that it may have been part of either a compacted pavement from the plaza surface during its use, debris left during or after the site’s abandonment, or the earliest layer of collapse washed down from the mound’s top. The accompanying ceramics represented a full spectrum of the San Isidro collection, ranging from Tok/Colos types (two diagnostic sherds) through pure Colos (80 sherds), Kal (95 sherds), and Chul (51 sherds) to Kal/Chul or even Kal/Caynac types (53 sherds).

Two other samples, PASI 8 and PASI 9, yielded very similar, narrow ranges around 400 b.c. PASI 9 comes from horizontal trenching into the northern slope of the mound, although it could not be determined whether the context of the sample was that of the collapse or already of the fill of the structure, as, apart from the humus layer, the entire operation was excavated through a uniform layer of chocolate-brown compacted clay without any discernible changes. That said, the sample was taken from the point located over 4 m into the heart of the mound. The associated ceramics span pure Colos (44 diagnostic sherds), Kal (102 sherds), and Chul (18 sherds), with Kal/Chul (33), Kal/Caynac (one), and Chul/Caynac (20) types represented, as well. It is noteworthy that within the humus layer, three sherds of Mizata orange type were found, a rare occurrence of the pure Caynac complex (200–1 b.c.) at San Isidro.

The PASI 8 sample is the only one derived from a clearly sealed context, originating from within the purported substructure collapse in the center of the mound, approximately 1.2 m below the summit. The narrow range of dates, from 410–390 b.c., may indeed correspond to the termination of the previous version of the structure. The few associated ceramics found embedded in the layer from which the sample was taken exclusively represent the Kal complex; however, that set of archaeological material, found during the 2024 season, was still pending thorough analysis at the moment of submission of this manuscript.

At first glance, the remaining three samples, PASI 4, PASI 5, and PASI 6, appear to be contradictory to what is assumed of the PASI 8 context. The first two come from layers deposited above the substructure, with PASI 5 collected just 10 cm below the G-VIII grouping of figurines and other objects and PASI 4 taken from approximately the same depth as G-VIII but over a meter to the east, outside the area outlined by the groupings of deposits. PASI 6 was obtained from a 1.5 m deep operation at the edge of the summit, beyond the point where the remains of a substructure disappear. PASI 4 resulted in a date range that barely overlaps with the narrow ranges of PASI 1, PASI 8, and PASI 9, while the other two samples yielded significantly older date ranges that do not overlap with the ca. 400 b.c. dating. All three results are much less exact, following a pattern common for most Middle Preclassic radiocarbon dates caused by flattening of calibration curves within the 2300–2700 b.p. CRAs range (see Love Citation2018, 261 for elaboration on the problem). The specimens constituting samples 4–6 were found in isolation as small, stand-alone chunks of charcoal or small pockets of ash with charcoal particles, consistent with the assumption that the fill of the structure contains mixed domestic refuse. Thus, it is logical to expect that, once the construction of Cerrito 1 was nearing completion, the construction material had to be mined from deeper, older layers of middens and deposited on top of the collapsed substructure to erect the superstructure, within which at least some groupings (G-II, G-III, G-IV, G-VIII, and G-IX), if not all of them, were enclosed.

The radiocarbon dates paint an unclear picture that may be interpreted in more than one way. However, at the present state of research, the one proposed here appears to be the simplest and most logical. The dates around 400 b.c. most likely indicate the moment of termination of the previous version of Cerrito 1 and construction of the final mound (especially PASI 8), while older, imprecise ranges serve uniquely to provide very vague terminus post quem dates for the extraction of construction material.

Discussion

As evidenced by the Tok and Tok/Colos ceramics, the earliest signs of a permanent settlement at San Isidro date back to at least the beginning of the 1st millennium b.c. However, the emergence of monumental architecture in the form of earthen mounds seems to occur no earlier than the Kal period, with the second construction episode coinciding with the transition from Kal to Chul. Typological chronologies provided by Sharer (Citation1978, vol. 3), Beaudry-Corbett (Citation1983), Ichikawa and Guerra Clará (Citation2018), and others place this transition around 400 b.c. (see ), aligning well with approximately half of the radiocarbon dates from Cerrito 1.

In the pre-monumental stage, ancient San Isidro may have been a large settlement or, possibly, a cluster of closely-spaced small settlements. Perhaps during the Kal complex duration, ca. 650–400 b.c., an unknown impulse prompted the community to transport hundreds of thousands of bucketloads of dirt and clay, excavated from refuse pits and, most likely, other locations as well, and heap them to form at least the early version of Cerrito 1, complete with the wattle-and-daub, thatched-roof building on top. Perhaps some other structures were erected at that time, as well. At the end of the Kal, or perhaps early in the ensuing Chul complex, more than 50 specific points were chosen to erect additional mounds, and existing ones were enlarged. Either of these collective efforts required incentive, planning, and coordination, indicating that both impulses happened under the auspices of an individual or a group of individuals capable of initiating and supervising such an endeavor. We grapple with the implications of the purported appearance of such elites further on.

The specific function of the mounds at San Isidro remains elusive. The variation in shapes and heights suggests that the lower and more extensive mounds could have served as foundational platforms for perishable superstructures, possibly for residential, administrative, or public purposes, or as elevated grounds for communal or ritual activities. The taller mounds with limited space on their summits might have functioned as architectural elements to delineate particularly revered spaces, reserved for ritual and religious use. This differentiation of space usage based on the shapes and dimensions of earthen structures is a recurring theme in Mesoamerican studies (see Daneels Citation2020, Citation2021). The discovery of precious jade objects and a tableau of figurines within the fill of Cerrito 1 suggests the possibility of a commemorative or even funerary function (see ).

Within the tableau, the figurines were arranged in a premeditated way. The male and one large female, and the “teenager,” were oriented along the presumed axis of the entire structure, that is, 15° south of west-east, with the heads facing the east. The male and the “teenager” lay next to each other, while the female was found somewhat apart, slightly to the north. The “baby girl” was found oriented face-down, perpendicular to the others, with the head pointing 15° east of north, and tucked close to the hip of the large female. Finally, the other large female was found some distance west from the first female, face-down, and with the head pointing almost exactly towards west. The “baby girl” was the only one intact, while all others had their limbs and/or necks broken off. The breakage was likely intentional, although the acacia roots that had weaved between the figurines make it impossible to entirely exclude natural processes.

One other site where very similar figurines were found in context is Tak'alik Ab'aj on the western Pacific slopes of the Guatemalan highlands. There, six such large female figurines were found in a tomb of an elite individual, forming part of larger funerary assemblage that also included serving vessels (some possibly stacked), numerous tubular jade beads, jade disks, and a jade pendant representing an abstract avian personage with the beak pointing down and arms or wings folded over the chest of an anthropomorphic body. The jades were discovered in groups indicating the location of wrists, ankles, and the upper chest of the buried individual, and two flat stones were placed on their edges delimiting the original position of the head. However, the actual skeleton did not survive taphonomic processes (Schieber de Lavarreda Citation2016). The entire burial has been dated roughly similarly to the findings at Cerrito 1, that is, to about 350 b.c., or the transition between late Charcas and early Providencia periods of the revised Kaminaljuyu chronology that has been commonly applied to most of the Guatemalan highlands (see ; Arroyo et al. Citation2020). The Bolinas figurines from Tak'alik Ab'aj, although found piled horizontally one on top of the other, were interpreted by Christa Schieber de Lavarreda as originally standing upright in a carefully arranged circular order related to cardinal directions and representing a ritual dance (Schieber de Lavarreda Citation2016).

The San Isidro figurines, also capable of standing upright, would in such a scenario face west or northwest, standing in line, with an exception of the “baby girl” who would stand in the same line, albeit facing north or northeast. However, given the high probability that all figurines but the “baby girl” were purposefully broken prior to, or during, deposition, they were most likely placed horizontally in the fill during construction of the topmost level of Cerrito 1. Perhaps, then, their purpose was to perpetuate images of actual personages and denote their mutual relations by their relative position. The need to portray a group of individuals may hint at the funerary function of the whole tableau, perhaps in an attempt to metaphorically send the family members of the deceased on the way to the other world as companions.

There may be other explanations and interpretations of the figurines, including that of symbolically representing an entire community (consisting of males, females, and children) in a rite promoting community well-being or depicting a set of divine beings in an unknown mythological or religious configuration. Nevertheless, the content of all the groupings from the top of Cerrito 1 closely resembles that of the funerary assemblage of the Tak'alik Ab'aj burial, including the tubular beads, jade disks, and a jade pendant in the form of an abstract avian personage. In both cases, the human remains are missing, although in Tak’alik Ab’aj, the funerary character of the context is clear. In the case of San Isidro, the purported erosion involving the washing down of the entire upper level of Cerrito 1 may be responsible for the disruption and shifting of some of the objects from their original position. That said, some of them, in particular the stacked vessels that maintain their original position, hint that the hypothetical burial was oriented along the 15° north skewed east-west axis rather than the equally skewed north-south line of the Tak'alik Ab'aj example.

The avian celtiform pendants found in both San Isidro () and Tak'alik Ab'aj have similarities reported at other sites throughout Mesoamerica, either in funerary contexts or as stand-alone offerings. Some of these sites include Cerro de las Mesas and Chaksinkin in Mexico, Altun Ha in Belize, and Copan and Playa de los Muertos in Honduras, as well as at least one other site in El Salvador, namely the Casa Blanca/El Trapiche area of Chalchuapa (Mora-Marín Citation2008). It is worth noting that avian celtiform pendants, as opposed to anthropomorphic ones, are believed to have originated in Costa Rica rather than Mesoamerica. They have been traced back to as early as 600 b.c., with numerous examples found in the Gulf of Nicoya and Guanacaste areas. Their presence in Mesoamerica, reciprocated by the existence of anthropomorphic pendants of “olmecoid” style in Central America, serves as an indicator of Middle and Late Preclassic exchange between the two large regions (Mora-Marín Citation2021, 53). Such exchange likely involved a combination of overland and oversea transportation, with hubs at sites controlling passage, such as San Isidro and Tak’alik Ab’aj on the Pacific coast and Playa de los Muertos, Altun Ha, and Cerro de las Mesas on the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico coasts.

The similarities between San Isidro and Tak’alik Ab’aj are also evident in the construction techniques. Many examples of Middle and Late Preclassic architecture at Tak’alik Ab’aj are constructed using compacted clay, a technique remarkably similar to that employed at San Isidro, with no stones present either within the fill or on the surfaces of the structures (Schieber de Lavarreda Citation1994; C. Schieber de Lavarreda, personal communication Citation2023). This technique seems to also be preferred among numerous contemporaneous sites that share other similarities with San Isidro, including Middle–Late Preclassic Izapa (Rosenswig Citation2021), Chocolá (Kaplan and Paredes Umaña Citation2018, 126–193; Kaplan, Valdes, and Paredes Umaña Citation2004), Kaminaljuyu (Kidder, Jennings, and Shook Citation1946), Santa Leticia (Demarest Citation1986, 32–34), and Casa Blanca/El Trapiche (Sharer Citation1978 vol. 1; Shibata Citation2021). In some of these sites, stones, adobes, and compressed volcanic ash blocks known as talpetate are present in contemporaneous constructions or constitute later stages of development. However, San Isidro appears to favor earthen constructions throughout its existence. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that some of the larger mounds may have stone cores deep within their centers or stone bases, as evidenced by the previously mentioned mounds cut through by a modern access road in the north of the site. Other examples of such construction technique were known to exist in the vicinity of San Isidro during the Preclassic period. In 2022, the authors, accompanied by Paul Amaroli of the National Foundation of Archaeology of El Salvador (FUNDAR), visited the site of Los Lagartos, located approximately 10 km southwest of San Isidro (see inset of ). The site has been known since at least the first half of the 20th century a.d. (Longyear Citation1944, 23). Our brief survey of the surfaces and vicinities of still-visible mounds provided tentative ceramic dating of the site to the Kal–early Caynac complexes (approximately 650–1 b.c.). Unfortunately, we discovered that at least three mounds on cultivated land had been recently bulldozed, their cores excavated and scattered with a backhoe. Around the destroyed and hollowed-out centers of the mounds, we observed large amounts of stones and smashed fragments of basalt or slate slabs, indicating that relatively small nuclei, or perhaps bases or initial constructions, were made of stones and subsequently covered with massive earthen structures, similarly to examples from Chocolá (Kaplan and Paredes Umaña Citation2018, 187, 191). This pattern may also be applicable to some structures at San Isidro and other Late Preclassic sites nearby, seemingly composed only of earthen materials, such as Finca Cuyancua and Papaturro (see , inset), located at the eastern outskirts of the town of Izalco and south of the limits of the town of Caluco, respectively.

The monumental earthen architecture in the form of clay mounds appears to have been a common feature along the Pacific coast of southern Mesoamerica around the Middle–Late Preclassic transition, dated to approximately 400 b.c. The presence of Bolinas figurines and distinctive avian celtiform pendants, possibly of Costa Rican origin, across this region further supports the existence of an exchange corridor connecting a string of cultural spheres. The list of analogies between San Isidro and other Pacific coast and highland sites is longer, however.

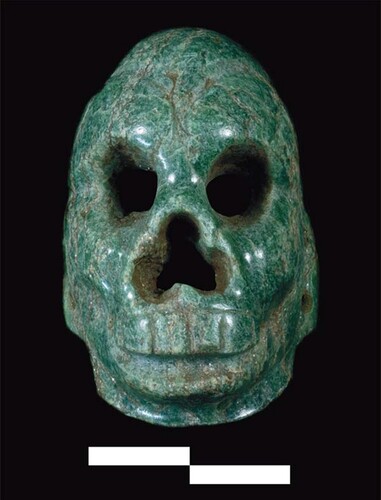

Curiously, two objects discovered in the westernmost groupings, G-I and G-VII—a small jade masquette in the form of a monkey skull and the travertine or calcite bowl—are indications of much broader connections, albeit of unknown character or chronology. The masquette is a distinctive object that does not resemble other jade works from El Salvador or southeastern Mesoamerica in general (). However, it bears a strong analogy to a miniature monkey masquette in the Dumbarton Oaks (DO) collection, catalog number PC.B.166. The DO specimen is similar in height (about 3 cm) and has been elaborated using solid drill bits, including the hollowing of the back part. The drillings for eyes, nose, and holes for threading a string are made biconically from either side of the openings. The DO specimen, like the San Isidro masquette, features sunken cheeks, seemingly created with a combination of shallow drilling and polishing. The Dumbarton Oaks masquette lacks provenience but was attributed to the Middle Preclassic Olmec sphere based on its stylistic features and certain similarities with three other specimens found in context at La Venta (Taube Citation2004, 153–155). The La Venta specimens, although similar in general material, size, shape, and elaboration technology, represent typically Olmec motifs of human, jaguarian, or were-jaguarian faces (Drucker, Heizer, and Squier Citation1959, 162–167, pls. 37–40). That being said, circumstantial evidence points to the San Isidro specimen’s origin and dating being the Middle Preclassic Gulf Coast of Mexico. Given that it was found at a relatively superficial depth, two scenarios are possible: either it was deposited at the time of the mound's construction, around 400 b.c., in its upper portion and surfaced recently due to erosion and the washing down of the superstructure or it was brought significantly later, most likely well after the abandonment of the site (or at least the portion with Cerrito 1) and placed there as an offering.

The second scenario gains more traction in conjunction with the second object—the travertine bowl. It, too, was found at a very shallow depth, roughly in the same area of the summit as the masquette. The exact material from which it was fashioned remains undetermined, but we are fairly certain that it is either calcite or travertine. Both of these minerals are highly reactive to moisture and acidity, factors that, unfortunately, are abundant at San Isidro, especially close to the surface. For that reason, the bowl displays a very advanced state of erosion, with its upper, presumably thinner, walls entirely dissolved, and the base and lower walls covered with a thick layer of crust. The crust was also found as a thin flake, detached from the bottom, underneath the vessel ().

Stone vessels in Mesoamerica are not uncommon, with the earliest examples coming from the Gulf Coast and Tehuacán Valley as early as the Early Preclassic (1850–1000 b.c.). However, these are made of granite and are quite crude in execution (Luke et al. Citation2002). Chlorite greenstone vessels were reported in the E-III-3 structure burials at Kaminaljuyu, dating to the Middle–Late Preclassic transition (Shook and Kidder Citation1952). The tradition of carving elaborate, thin-walled stone vessels geographically closest to San Isidro is in the Ulua Valley in northwestern Honduras, dated mostly to the Late Classic. They are known to have been traded and exchanged over vast areas, with specimens found as far as Pacbitun, Belize (King et al. Citation2022). Thus, Ulua Valley is one of the likely places of origin of the San Isidro bowl, although most forms of the Honduran vessels are much more elaborate than the specimen found at Cerrito 1. Some scholars use the term “marble” to describe the material from which the Honduran examples are made; nevertheless, it appears to be used as an umbrella term for a variety of rocks that include minerals as diverse as travertine, serpentine, soapstone, and even quartzite (Wells et al. Citation2014). The calcite and travertine (often called onyx or tecali in Spanish language sources) vessel tradition is documented in eastern Oaxaca and western Chiapas in Late Classic times (a.d. 600–900), expanding into Puebla and Hidalgo during the Postclassic (a.d. 900–1521). In Tula, one of the most important Postclassic sites, ancient travertine workshops were discovered (Diehl and Stroh Citation1978). As a matter of fact, all the places within ancient Mesoamerica that developed a tradition of carving calcite or travertine vessels had easy access to at least one but often multiple sources of that material, as the quarries and outcrops are abundant in Oaxaca, Puebla, Hidalgo, and Chiapas in Mexico and in multiple places in Honduras. One of the most remarkable discoveries of travertine vessels was a cache found in the Tapesco del Diablo cave in western Chiapas (Linares Villanueva and Silva Rhoads Citation2001). Two of the vessels, now displayed in the Chiapas Regional Museum, Tuxtla Gutierrez, are globular bowls on small feet. Except for the feet, the vessel shapes are similar to the one found at San Isidro, albeit the Chiapas examples are slightly larger. However, the most similar analogy once again comes from Dumbarton Oaks in the form of a highly eroded travertine vessel, PC.B.114. Its walls were preserved to a greater height than in the San Isidro case, but they display a similarly serrated upper edge caused by dissolution. The vessel has three prong-like thin legs. Although it lacks provenience, it has been tentatively attributed to Late Postclassic northwestern Oaxaca or southern Puebla (Benson Citation1963, 28).

Thus, while it is currently not possible to pinpoint the exact origin of the San Isidro travertine vessel (which shall be done in subsequent stages of the project through petrographic or molecular studies), it is reasonable to attribute it a date range between the Late Classic and Late Postclassic (a.d. 900–1521). It is possible, then, that someone deposited the vessel on the surface of Cerrito 1 several centuries after its abandonment. This would explain its very shallow context and advanced erosion. Perhaps a similar act resulted in the deposition of the jade masquette, which, in such a case, would be an object of remarkable antiquity at that time. If that was the case, then San Isidro, or at least its most prominent structure, would have remained a locus of veneration and ritual activity. Given the turbulent history of the Classic period in El Salvador, including the Ilopango eruption that effectively reset the cultural mosaic of the region towards the end of the Early Classic, the individuals who performed those acts of veneration were not, most likely, directly descendant from the original population of San Isidro.

The monumental core of the site appears to have had at least two moments of construction activity. The later one happened around 400 b.c., as suggested by ceramics and some of the radiocarbon dates, while the earlier one, thus far detected solely within Cerrito 1 during the 2024 field season, must have happened sometime during the Kal complex, 650–400 b.c., judging by the associated ceramics. That said, the detailed analyses of materials obtained during the 2024 season were still pending at the time of this manuscript’s submission. The abandonment of the site must have happened around the turn of the eras, as no sherds from the later facet of Caynac (a.d. 1–200) or later complexes have been detected so far. Naturally, the available data comes from a disproportionately small area. However, most, if not all of the remaining portions of San Isidro may have been irreparably mixed and destroyed in terms of their archaeological context. Thus far, it seems that the eruption of the Ilopango volcano between the 5th and 6th century a.d. covered with ashes a place with no activity in or around its monumental structures.

Concluding Remarks

In the absence of explicit data indicating otherwise, most ancient settlements grew through a process of gradual population aggregation rather than through an appropriation of vacant loci by already consolidated, homogeneous groups of migrants—an idea thoroughly explored in essays by Love and Arroyo, Canuto and Estrada-Belli, Rosenswig, Smith, and Yoffee in Michael Love and Julia Guernsey’s recent monograph (Citation2022). It is unsurprising, then, that groups of people migrating through interconnected valleys in what is now El Salvador found the area of San Isidro favorable for settlement. It provided a commanding view over the junction of the Zapotitán and Rio Grande-Sensunapan Valleys, making the place less susceptible to surprise attacks by potentially hostile groups and facilitating control of the trail. This trail must have been quite busy, as it was the only route for well over 100 km in each direction that provided such an unobstructed access to the Pacific from the hinterland.

By 1000 b.c., a group or groups of unknown origin, but displaying significant similarity in ceramic production with the early Maya to the west, established a permanent settlement, either as a single nucleated village or several smaller, decentralized hamlets. The population most likely grew not only through internal processes but also by accommodating more of such migrant groups, some likely coming not only from the west but from other directions, as well.

Some centuries later, during the Kal complex (650–400 b.c.), the community of San Isidro embarked on a construction program that resulted in the erection of at least one but most probably several more clay mounds. The exact impulse for such growth remains unknown, but it may have come from the intensification in the development of other, often distant areas and the widening of potential sources and destinations of exchange. It is noteworthy that much of the long-distance exchange along Mesoamerica, and between Mesoamerica and the neighboring Isthmo-Colombian Area, was based on cabotage navigation. In the absence of beasts of burden or wheeled carriages, the bulk of heavy goods was transported along both coasts and through inland waterways, while human porters distributed exotic objects on a local level and/or into less available places (Clarkson and Fowler Citation2021; Hudson and Henderson Citation2017). Thus, San Isidro could have assumed a role of an exchange hub, or a gateway community, not unlike contemporaneous Chalcatzingo in central Mexico, Izapa on the easternmost Mexican Pacific coast, and Tak'alik Ab'aj in Guatemala, or Classic period Copan in Honduras (Hirth Citation1978; Johnson and Canuto Citation2023; Rosenswig Citation2023; Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo Citation2023), controlling, or perhaps providing, the transition between the pan-regional and local networks.

At that time, Cerrito 1, being the tallest structure of the entire settlement even in its early version, was crowned by a wattle-and-daub structure with a thatched roof. Judging by the pyramidal shape of the mound, and the rather small size of the building on top, it most likely had a religious/ritual function. As hinted previously, such a labor-intensive and complicated endeavor as construction of a several meters tall pyramid with a temple on top indicates the existence of some sort of supervising elites, be it a group of people or a single individual. During the Middle Preclassic (1000–400 b.c.), there is very little evidence for the existence of rulers or consolidated elites in southern Mesoamerica, despite a number of monumental constructions and rich deposits of goods dating to that period. At Chalchuapa, located less than a day’s walk from San Isidro, several platforms were constructed at that time, as well as an early version of an impressive pyramid, E3-3, which most likely was, and still remains, the tallest prehispanic building in El Salvador. Despite the monumentality, no unequivocally elite burials were found from that period, while the richest deposits of prestige goods were found at the shores of a nearby lake, Laguna Cuzcachapa (Sharer Citation1978, 1:43–59). Therefore, it has been suggested that prior to the Late Preclassic, the social structure of southern Mesoamerican societies was less hierarchical, and elites or rulers had much less elevated—or permanent—status than their later counterparts. There is compelling evidence for similar trajectories of social development in Middle Preclassic Honduras, including Los Naranjos, Yarumela, Puerto Escondido, and the Naco and lower Cacaulapa Valleys (Dixon et al. Citation1994; Ito Citation2010; Joyce and Henderson Citation2002; Urban and Schortman Citation2012). It is thus quite probable that the Middle Preclassic surge of construction activity at San Isidro was supervised by the nascent elites that were not that far removed from the rest of the local society. In that case, the impulse behind committing what must have been an entire community to such an undertaking would be of either public, strictly ritual, or mixed character rather than commemorative. The public character of the motivation could stem from a need to visually fix, delimit, and center the settlement in the environment and to impress any newcomers and passersby in order to repel potential aggressors and display the right and ability to control the natural corridor leading to and from the coast. The religious and ritual functions, prior to the emergence of rulers with claims of divinity, would have concentrated on the worshipping of various deities and ascertaining their sympathy and benevolence towards the community.

The second moment of construction, likely on a much larger scale involving most, if not all, of the pyramids and platforms at the site, happened early in the ensuing Late Preclassic period, universally dated between 400 b.c. and a.d. 200 or 250. In the Guatemalan Highlands, the site of Kaminaljuyu enters the phase referred to as Providencia (400–100 b.c.), assuming either control, or at least an influence, over a vast area ranging from Tak'alik Abaj, Izapa, and beyond to the west and large portions of western El Salvador and southern Honduras in the east. In fact, the Chul and early Caynac complexes known from Chalchuapa, Santa Leticia, San Isidro, and other sites are often considered local manifestations of the Providencia sphere (Kosakowsky, Estrada-Belli, and Pettitt Citation2000). Apart from ceramics, one of the characteristic features of that sphere is the emergence of permanent elites and, possibly, rulers with ambitions to occupy some part of the spotlight hitherto reserved for the deities. The evidence for this change consists of the presence of elite burials within structures of unequivocally ritual character, i.e., pyramids, and the appearance of rulers in iconography, such as stelae and altars (Kaplan Citation2000). At San Isidro, at least three possible stelae were found, along with at least one possible altar, although all are devoid of any iconography, and judging by their smooth and polished surfaces, they were designed that way rather than losing any traces of iconography due to erosion. All were moved from their original positions by a tractor during plowing, although the authors managed to document one of them shortly after it was dragged to the surface by the plow on top of the Trapiche 3 mound, which directly faces Cerrito 1 (). Smooth stelae without iconography have been documented elsewhere within the Providencia sphere of the Late Preclassic, including Chalchuapa (Ichikawa, Shibata, and Ito Citation2009; Paredes Umaña Citation2012).

Figure 13. One of the plain stelae from San Isidro at the time of its accidental discovery by a plow in 2018.

Perhaps, then, the second impulse for embarking on the even more impressive endeavor of construction of over 50 mounds at San Isidro, including the termination of a temple on top of Cerrito 1 and the enlargement of the mound, came from a generation of elites that grasped enough power to bury one of their own in a space previously reserved for communal and/or religious purposes, now enlarged by the hands of their subjects. It would be one of the earliest such cases, dated to the very beginning of the Late Preclassic.

The people of San Isidro were not isolated in their building efforts, as a number of sites along the Pacific coast and the Guatemalan Highlands exhibited a similar construction heyday at the same time. This, most likely, signifies the pan-regional emergence, or consolidation, of ruling elites, capable of motivating or coercing entire societies to carry out such ambitious endeavors. The explicit and implicit indications of funerary activities within some of the structures with tentatively religious characters (i.e., pyramidal structures likely supporting perishable shrines or physically elevating sacred grounds) point to possible identification of the rulers with divine beings, justifying their burials in venerated loci. The identification of rulers with gods is one of the hallmarks of the ancient Mesoamerican worldview in the ensuing Classic period (Guernsey Citation2010; Houston and Stuart Citation1996; Looper Citation2010).

The exchange corridor created by a string of those sites traverses what modern archaeologists tend to call “cultural areas:” precious objects and ideas were brought back and forth between places as distant as Izapa in modern day coastal Chiapas (Mexico) and the Gulf of Nicoya in western Costa Rica. It is not much of a speculation to place the real western terminus of this corridor not along the Pacific coast but in the Central and Gulf Coast Mexico, where the cultural development and far-reaching connections were already in place even earlier, by the Early and Middle Preclassic times (Rosenswig and Martínez Tuñon Citation2020). There is also some circumstantial evidence that there may have been two such corridors, one along each coast or perhaps along the Pacific coast and overland through the base of the Yucatan peninsula (I. Šprajc, personal communication Citation2023). This would help to explain the presence of certain objects, such as Usulutan pottery and jade celtiform pendants, in south-central Yucatan and Belize. The linkages between both corridors would also have existed in between the endpoints, such as the Bolinas figurines and avian jade celtiforms, present in very analogous contexts in Tak’alik Ab’aj and San Isidro, that also appear in Playa de los Muertos in northwestern Honduras. The linkage of the Copan, Naco Ulua, and Comayagua Valleys of Honduras with El Salvador is further evidenced by the circulation of Usulutan wares throughout most of the Middle and Late Preclassic times. Usulutan pottery stands out in most ceramic assemblages, as it is usually manufactured from fine pastes and with relatively greater care than most other wares, quite obviously destined to be used during feasts, rituals, and other special occasions rather than for everyday domestic use. Usulutan vessels from San Isidro were uniformly found in contexts implying deliberate offering of special objects, thus fitting well in the general pattern. It appears that Late Preclassic elites of San Isidro ascribed to food serving etiquettes and ceramic manufacture modes that were in accordance with the tradition covering the entire area of El Salvador and great portions of Honduras and southern Guatemala.

The exact number and routes of the exchange corridors aside, the evidence directly indicates that the people inhabiting western El Salvador actively participated in (i.e., benefited from and contributed to) not only the pan-Mesoamerican exchange network but also the interregional connection that reached as far as Costa Rica since at least as early as the Middle–Preclassic transition dated to 400 b.c. Thus, any notions of peripherality, infused into the archaeological discourse through a wide adoption of the World-System Theory since the 1970s (see Blanton and Feinman Citation1984; Blanton, Kowalewski, and Feinman Citation1992; Carmack and Salgado González Citation2006, among others), need to be revised. In reevaluating the relationships between San Isidro and other western Salvadoran sites with the broader Mesoamerican region to the west and the Isthmo-Colombian Area to the east, the Community of Practice framework, which has been effectively applied in similar studies in Honduras and other locations (Joyce Citation2021a, Citation2021b), offers a promising alternative approach. Currently, there is not enough data to ascertain the ethnolinguistic composition of the Preclassic San Isidro community. Ceramic evidence demonstrates strong ties with, if not an outright participation in, the Providencia sphere of the early highland Maya tradition. Clues drawn from architecture and overall site orientation also indicate affinities of the early San Isidro population with broader Mesoamerica, yet they do not align with any specific culture. Connections with the east are too vague to provide concrete insights. Overall, the highland Maya groups remain the most likely sources of the ethnolinguistic identity of the San Isidro population, although before the Late Classic, all evidence remains circumstantial. The Community of Practice approach may allow us to trace and interpret particular strands of data indicating contacts and distinguish simple trade exchange from deeper relations indicating participation in shared traditions. In doing so, it may bring us a step closer to reconstructing the identities of the people who built and inhabited ancient San Isidro and other western Salvadoran settlements.

Importantly, the orientation of structures towards points in the horizon, often used as indicators of certain identity traits, has to be applied with extreme caution in the case of San Isidro. Most of the western, northern, and eastern horizon visible from the site have been dramatically altered since pre-contact times. The so-called Three-Volcanoes-Complex, consisting in fact of five peaks (Izalco, Cerro Verde, and Santa Ana in the back and Cerro Chino and San Marcelino in the front) is most likely a product of 17th century a.d. volcanic activity. The nearly 2000m high Izalco volcano emerged only during Colonial times, while the entire San Marcelino massif, consisting of San Marcelino proper and the adjacent Cerro Chino, is a parasitic creation that appeared during the early 18th century a.d. (Carr and Pontier Citation1981). The latter activity also resulted in one enormous lava spill that extends southeast from the volcanic complex for several kilometers, blocking direct access to the Zapotitan Valley and effectively creating a new horizon line. A similar fold of terrain braces the site from the west, also being most likely a product of the San Marcelino eruption or the earlier emergence of Izalco. It is therefore impossible to guess where the Preclassic inhabitants of San Isidro saw the rising and setting sun and how would it affect their place-making.

The picture painted by the information obtained from archaeological contexts at San Isidro, and from a growing number of analogies with places covering a vast area spanning several countries, shows that the “boundary area” between two large cultural spheres was not as peripheral, passive, and uncomplicated as the extant socio-political paradigms allude it to be. In particular, it appears to contradict the World-System model and puts in perspective the need for developing ever-sharper definitions of cultural boundaries.

The limited data in our possession suggests that the prosperity of San Isidro came to a rather abrupt halt around the turn of the eras. The cause is now purely speculative, with possible research directions including the expansion of the Chalchuapa and San Andres centers to the west and east of San Isidro, respectively, and a potential shift in transportation routes. Some four to five centuries later, the eruption of the Ilopango volcano in the late Early Classic times wiped all cultural activity from the region for decades. The return of settlements in the 7th century a.d. saw a new mosaic of identities and traditions that did not necessarily have direct links with the ones buried under the ashes. Nevertheless, even as late as the Late Classic or perhaps even Postclassic times, some people revered the ancient mounds of San Isidro enough to deposit precious goods on their abandoned, and perhaps overgrown, surfaces.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the National Science Center of Poland for funding the project (grant no. 2019/35/D/HS3/00219) and to the Ministry of Culture of El Salvador for the institutional support. We express our gratitude towards the ATAISI cooperative of San Isidro for giving us permission to work on their land. We are indebted to all the members of the San Isidro Archaeological Project, including our local workers, volunteering archaeologists, staff, and archaeology students, for all the hard work during and after the fieldwork. In particular, we would like to thank Joachim Martecki and Victor Escalón for organizing much of the work and leading by example. Special thanks go to our friends and families for support during the times of fieldwork and writing. Finally, we thank Paul Amaroli, Jonathan Kaplan, Carlos Flores Manzano, and Jarosław Źrałka, as well as three other anonymous reviewers, for sharing their knowledge and remarks that greatly improved this paper.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jan Szymański

Jan Szymański (Ph.D. 2013, University of Warsaw) is an archaeologist specializing in southeastern Mesoamerica. Among his research interests are questions of group identity formation and manifestation and the development of early sociopolitical entities. Currently, he is the director of the San Isidro Archaeological Project.

Miriam Méndez

Miriam Méndez is an archaeologist and ceramicist specializing in Salvadoran archaeology; previously, she led public archaeology projects in the Balsamo Mountains.

Notes

1 An onomastic problem arises with large portions of El Salvador and Honduras that seemingly did not participate in the Mesoamerican tradition at all or at least not until quite late in pre-contact history. The unfortunate yet all-encompassing term “Intermediate Area,” previously used to describe lands between Mesoamerica and the Andean Area in South America, was replaced by that of “Isthmo-Colombian Area,” which covers the span between southern Nicaragua and east-central Colombia but excludes Honduras and El Salvador. The purely geographical, culture-neutral term “Lower Central America” has been used with some reluctance as well, especially since its translation into Spanish (Centroamérica Inferior) carries a strong pejorative tone. The wedge-shaped part of non-Mesoamerican, non-Isthmo-Colombian Central America, comprised of eastern parts of El Salvador and Honduras, is yet to be adequately defined and named.

References

- Aimers, J.2013. Ancient Maya Pottery: Classification Analysis and Interpretation. Gainesville / Tallahassee /Tampa / Boca Raton / Pensacola / Orlando / Miami / Jacksonville / Ft. Myers / Sarasota: University Press of Florida.

- Andrews, V. E. W. 1976. The Archaeology of Quelepa, El Salvador. New Orleans: MARI, Tulane University Press.

- Arroyo, B., T. Inomata, G. Ajú, J. Estrada, H. Nasu, and K. Aoyama. 2020. “Refining Kaminaljuyu Chronology: New Radiocarbon Dates, Bayesian Analysis, and Ceramic Studies.” Latin American Antiquity 31 (3): 477–497.

- Ashmore, W. 2014. “Practices of Spatial Discourse at Quelepa.” In The Maya and Their Central American Neighbors: Settlement Patterns, Architecture, Hieroglyphic Texts, and Ceramics, edited by G. Braswell, 25–55. New York and London: Routledge.

- Beaudry-Corbett, M. 1983. “The Ceramics of the Zapotitán Valley.” In Archaeology and Volcanism in Central America, edited by P. Sheets, 161–190. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Benson, E. 1963. Handbook of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art. Washington D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection.

- Blanton, R., and G. Feinman. 1984. “The Mesoamerican World System.” American Anthropologist 86 (3): 673–682.

- Blanton, R., S. Kowalewski, and G. Feinman. 1992. “The Mesoamerican World-System.” Review 15 (3): 419–426.

- Boggs, S. 1973. “Ancient Costumes and Coiffures.” Americas 25 (2): 19–24.

- Carmack, R., and S. Salgado González. 2006. “A World-System Perspective on the Archaeology and Ethnohistory of the Mesoamerican / Lower Central American Border.” Ancient Mesoamerica 17 (2): 219–229.

- Carr, M., and N. Pontier. 1981. “Evolution of a Young Parasitic Cone Towards a Mature Central Vent; Izalco and Santa Ana Volcanoes in El Salvador, Central America.” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 11 (2-4): 277–292.

- Clarkson, P., and W. Fowler. 2021. “Human Caravans of Mesoamerica.” In Caravans in Global Perspective, edited by P. Clarkson, and C. Santoro, 235–266. London and New York: Routledge.

- Cooke, R. 2021. “Origins, Dispersal, and Survival of Indigenous Societies in the Central American Landbridge Zone of the Isthmo-Colombian Area.” In Pre-Columbian Central America, Colombia, and Ecuador: Toward an Integrated Approach, edited by C. McEwan, and J. Hoopes, 49–83. Washington D.C: Dumbarton Oaks.

- Daneels, A.2020. Arquitectura Mesoamericana de Tierra, Vol. 1. Mexico D.F: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Daneels, A.2021. Arquitectura Mesoamericana de Tierra, Vol. 2. Mexico D.F: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Demarest, A. 1986. The Archaeology of Santa Leticia and the Rise of Maya Civilization. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute Publication 52, Tulane University.

- Diehl, R., and E. Stroh. 1978. “Tecali Vessel Manufacturing Debris at Tollan, Mexico.” American Antiquity 41 (1): 73–79.

- Dixon, B., L. Joesink-Mandeville, N. Hasebe, M. Mucio, W. Vincent, D. James, and K. Petersen. 1994. “Formative-Period Architecture at the Site of Yarumela, Central Honduras.” Latin American Antiquity 5 (1): 70–87.

- Drucker, P., R. Heizer, and R. Squier. 1959. Excavations at La Venta, Tabasco, 1955. Washington D.C: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 170, United States Government Printing Office.

- Dull, R., J. Southon, S. Kutterolf, K. Anchukaitis, A. Freundt, D. Wahl, P. Sheets, P. Amaroli, W. Hernandez, M. Wiemann, and C. Oppenheimer. 2019. “Radiocarbon and Geologic Evidence Reveal Ilopango Volcano as Source of the Colossal Mystery Eruption of 539/40 CE.” Quaternary Science Reviews 222.

- Estrada, J. 2017. “Caminos Ancestrales: Las Rutas de Kaminaljuyu Durante el Preclásico Tardío.” (Licenciatura Thesis). Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala.