ABSTRACT

This paper coordinates archaeological information on the changing urban landscape of Egypt’s first Islamic-era capital, Fustat, with topographical, social, and economic insights from the Geniza archive and other sources. A focus on the organization of the city’s pottery industry provides new insights into the multiple “abandonments” and reoccupations familiar from historical sources, showing how diverse residential areas were turned to industrial use (and back) via adaptable transitional processes.

Fustat: Urban Context and Ceramic Significance

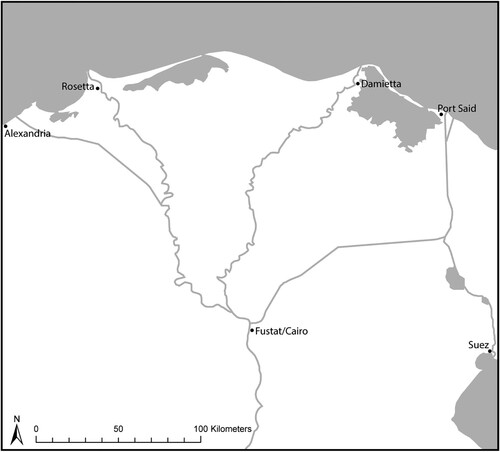

The great city of Fustat—the precursor to Cairo—is located on the eastern bank at the apex of the Nile Delta in Egypt (). A settlement here—Babylon of Egypt—is archaeologically attested from as early as the 6th century b.c. and continues, albeit with fluctuations in density and locale, to the present day (Sheehan Citation2010; ). A series of key events shaped this landscape: the construction in a.d. 107 by Trajan of the Nile-Red Sea canal through the site and its fortification by Diocletian ca. a.d. 300, who built a large fortress to defend the canal entrance; the establishment and embellishment of Fustat itself as a new capital city following the Arab-Muslim conquests in a.d. 641; the destruction of parts of this city in the ‘Abbasid conquest of a.d. 750 and subsequent redevelopment; the foundation of new quarters of the capital to the north and east by the ‘Abbasid, Tulunid, and Fatimid dynasties, with intermittent crises of security and prosperity leading to the use of large areas of Fustat for industrial purposes from the 13th century a.d. onwards; and, its subsequent and continuing redevelopment from the 17th century a.d.

Table 1. Summary of the main chronological phases, ruling dynasties, and key events relating to Fustat and the wider region.

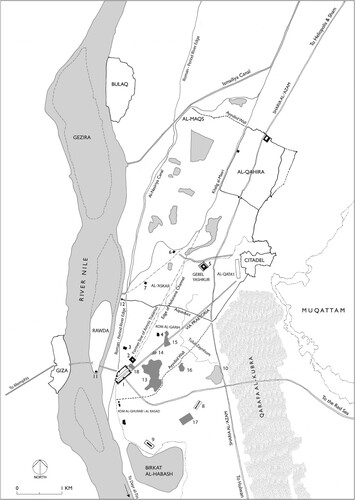

The archaeological site of Fustat was until recently an evocative but rarely visited area of crumbling ruins northeast of the fortress of Babylon and southeast of the Mosque of ‘Amr ibn al-‘As in the quarter now referred to as Old Cairo (). It is rapidly being lost to rising groundwater and encroachment from the modern city, and a major project has been underway since 2021 that is incorporating most of the area into the Fustat Hills Park. However, the remaining 20 ha, currently managed by the Ministry of Antiquities, only hints at the original scale of the settlement, for at different times the city of Fustat covered much of present-day southern Cairo, extending east to the ancient cemeteries at the foot of the Muqattam cliffs and south beyond the plateau of Istabl ‘Antar to the modern area of Dar al-Salaam, near the former Birkat al-Habash (, ). In addition to extensive residential quarters initially set out on tribal lines, Fustat contained a cosmopolitan mercantile and administrative center and a thriving port occupying a large area along the riverfront. Some parts of this conurbation were never abandoned and continued to be occupied through the post-medieval era to the present, in particular the riverside and parts of the district around Babylon. Much of the site, however, was reduced to ruins at various times and occupied only informally by the late medieval period.

Figure 2. View across the remains of Fustat, looking southwest from the Antiquities Inspectorate buildings, in January 2006 (A. L. Gascoigne).

Figure 3. The Fustat-Cairo area, with locations of features discussed in the text: 1) Babylon fortress, the area commonly known as “Old Cairo”; 2) Mosque of ‘Amr; 3) Church of Abu Sayfayn; 4) Tomb of Abu Su’ud; 5) Mosque of Ibn Tulun; 6) Mosque of Sayyida Zeinab; 7) Church of Mar Mina; 8) Saba‘ Banaat mausolea; 9) Fort of Istabl ‘Antar; 10) ‘Ayn al-Sira; 11) Nilometer; 12) Fumm al-Khalig; 13) Bahgat’s excavations; 14) Fustat-A; 15) Fustat-B; 16) Fustat-C; 17) Gayraud’s excavations; and, 18) fawakhir site (N. J. Warner/P. Sheehan).

Figure 4. Area around the Roman fort of Babylon, with locations of features discussed in the text: 1) Roman riverside towers; 2) Ben Ezra Synagogue; 3) Hanging Church; 4) Abu Serga Church; 5) Church of St. Barbara; 6) Wedding Hall; 7) Convent of St. George; 8) Mosque of ‘Amr; 9) Nilometer; 10) Ayyubid wall; 11) Bahgat’s excavations; 12) fawakhir gardens: a) Waseda University excavations lead by Sakurai and Kawatoko, b) Old Cairo Archaeology excavations lead by Sheehan, c) Supreme Council of Antiquities excavations lead by Muawad Hassan Hussein; and, 13) Fustat National Ceramics Centre (N. J. Warner/P. Sheehan).

Fustat is well represented in the collections of many western museums through the medium of pottery. Significant quantities of late Medieval glazed vessels and sherds produced in Fustat were retrieved, exported, and collected by these institutions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries a.d. Subsequent study of Fustat’s ceramic industries has until relatively recently been based largely on these museum collections, broadly divided between approaches more art-historical than archaeological (e.g. Scanlon Citation1999; Watson Citation2004) and archaeometric (e.g. Matin and Ownby Citation2023; Wolf et al. Citation2003), with less attention to the wider archaeological context. We therefore have a reasonable understanding of elements of the production of some Fustat ceramics (e.g. style, glaze technology, and composition) but much less of the urban setting of their production and its dynamic and changing location in the landscape. It is this question that we will address here.

The urban context of ceramic production sites is relevant to other Medieval settlements in the eastern Mediterranean. Excavations in Jerash have revealed the presence of ceramic production dating to the 7th−8th century a.d. in central quarters of the city and in proximity to important civic and religious buildings (Rattenborg and Blanke Citation2017, 317–318); centrally located production is also attested in ‘Abbasid–Fatimid Ramla (Masarwa Citation2015). However, other sites have provided evidence of externally located industrial suburbs. In Tiberias, a cluster of 10th−11th century a.d. ceramic production sites was identified south of the city (Stern Citation1995), while in Raqqa, “an extensive extramural industrial and commercial area,” including multiple ceramic kilns, developed in ‘Abbasid times. Henderson and colleagues (Citation2005, 133) note poorly characterized phases of decline, continuity, revival, and abandonment in this suburb between the 8th and 13th centuries a.d., indicating a system in dynamic flux and responding to diverse social, economic, and political pressures. Clearly, urban ceramic industry was differently located and variably expansive across time and space in a manner that is not yet well understood.

Returning to Fustat, an analysis of pottery production thus has great potential to augment understanding not only of the organization of this Medieval industry but also of the character, dynamism, and resilience of the city itself. Fustat clearly produced more than just pottery, but the site is heavily waterlogged with poor preservation; in the case of some industries, we must largely fall back on speculation to inform us as to their material nature. Other forms of production were certainly taking place in the Medieval city, but the signature of ceramic manufacture is highly visible if only through its products, and the scale of pottery-making can be industrial and messy, dominating the landscape.

Focusing on evidence for the ceramics industry, then, this paper investigates the processes by which Fustat underwent complex, multi-stage transitions, from a densely occupied, wealthy, early Islamic capital to late Medieval and early modern ruin fields, taking in informal settlement and polluting industry along the way. While the nature of particular parts of the city at various points in this process has been investigated in detail (Denoix Citation1992; Harrison Citation2015; Kubiak Citation1987; Kubiak and Scanlon Citation1989; Sheehan Citation2010), less attention has been paid to the social and economic factors that underpinned the repurposing of urban plots and districts. Throughout Cairo’s history, large-scale changes have been manifested by decree, as, for example, with the foundation of the elite administrative enclosures al-‘Askar, al-Qata’i‘, and al-Qahira, the 19th century a.d. reformulation of Downtown/Khedival Cairo to the north of Fustat (Mitchell Citation1991, 64–69), and indeed the current Fustat Hills Park project, but significant shifts in urban character have also resulted from informal decision-making by large numbers of independent inhabitants (Sims Citation2012). As we will demonstrate, both these models were influential during the development of Medieval Fustat but with informal processes of change more strongly manifested: industrial development shows self-organization within a hands-off framework of management, itself largely focused on control of product rather than space.

Available evidence for these complex processes is diverse, multidisciplinary, and challenging. Descriptions of Fustat such as those by Ibn Duqmaq (a.d. 1349–1406) and al-Maqrizi (a.d. 1364–1442) have been revealed as nostalgic, eschatological, and atemporal (Denoix Citation1996; Rabbat Citation2000, 24), characteristics obscuring their usefulness as indicators of short-term chronological change in specific locales. The accounts contain elements of confusion: al-Maqrizi, for example, linked one phase of abandonment to the burning of the city during the Crusader invasion in a.d. 1168, but Kubiak (Citation1976) questioned the scale and extent of this destruction, given that many parts of the city were already degraded; he argued that al-Maqrizi conflated the events with the earlier, more destructive burning of Fustat in a.d. 750. The Geniza archive from the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo contains many indicators of social and economic processes, but these tend to be specific to individuals or particular properties (Goitein Citation1967–1988). Most evidence from textual sources is thus difficult to locate precisely within the physical remains of the city. To what extent do the twin approaches of industrial and urban archaeology offer a way forward? Fustat has been the site of multiple excavations over more than a century, important among which are those of George Scanlon and Władysław Kubiak (Kubiak and Scanlon Citation1980, Citation1989; Scanlon Citation1965, Citation1966, Citation1967, Citation1971, Citation1976, Citation1979, Citation1981, Citation1984a, inter alia) and Roland-Pierre Gayraud (Gayraud Citation1997; Gayraud, Björnesjö, and Denoix Citation1986; Gayraud, Björnesjö, and Speiser Citation1994; Gayraud and Peixoto Citation1993; Gayraud and Treglia Citation2012; Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017; Gayraud et al. Citation1987, Citation1991, Citation1995). More recently, archaeological work undertaken in Old Cairo between 1999 and 2006 as part of the Old Cairo Groundwater Lowering Project investigated deposits obscured by subsequent and modern disturbances, providing truncated sequences typical of complex urban archaeology (Sheehan Citation2010). This work has transformed our understanding of both the early development of the city and the Medieval urban landscape, particularly when considered in conjunction with information from the abovementioned textual sources, especially the Geniza documents.

In this paper, we will first outline the chronological evidence for ceramic production, indicating major shifts in its location where the evidence allows, drawing on the results of diverse archaeological excavations, including our own. We will then situate the industry into its social and administrative context and discuss the implications for wider urban processes. Ultimately, we aim to introduce greater complexity into narratives around the relationship between industrial activity and urban “decline” and “abandonment,” where areas are given over to new purposes.

The Fustat Pottery Industries: Locations and Nature of Production

Pottery production was a significant aspect of the repurposing of large areas of Fustat at particular times. The industry flourished there from at least the 9th century a.d. to the present, adapting over time to changing socio-economic and urban contexts. Ceramic workshops were inserted into Fustat’s urban fabric in ways that reflect processes of decline vs. prosperity. As we will demonstrate, most industrial infrastructure was constructed in “abandoned” or re-purposed residential or elite areas, albeit ones that might be subsequently reoccupied and re-abandoned. The incorporation of industrial infrastructure into areas combining residential and industrial functions and having a protracted mixed-use character was apparently not common. Characterization of Fustat’s ceramic industries through time will facilitate understanding of production but, more importantly, of the long-term cycles of urban decline and regeneration that are a fundamental characteristic of Fustat’s history. To support this discussion, summarizes the evidence for ceramic manufacture from multiple archaeological interventions at the site. This reveals large-scale shifts from the south towards the north mirroring the development of the city, with social and urban pressures eventually pushing the industry back southwards due to its noxious nature, the growth of huge rubbish mounds generated by the Medieval city, and the availability of space.

Table 2. Summary of archaeological evidence for ceramic production in Fustat, organized broadly south to north.

Pottery production prior to ca. a.d. 800

There is no clear evidence for potting in Fustat before the 9th century a.d. Sparse indications from the wider region point to production located—like the Medieval/modern clay sources discussed below—south of the capital: a Roman faience kiln was excavated by Petrie at Memphis (Citation1909, 14–15), while 6th/7th century a.d. pottery workshops with several kilns were identified at the Monastery of Apa Jeremias, Saqqara (Ghaly Citation1992). 5th/6th century a.d. papyrological evidence supports the riverine transport of jars, and we might speculate that ceramics made their way northwards to the Babylon area by boat (Gallimore Citation2010, 183).

The Old Cairo riverside was already a major industrial and commercial zone in late Roman and early Islamic times. Much of Fustat’s commercial and strategic prominence derived from its function, inherited from Roman and Byzantine rule, as a port and customs point for ships and merchandise from Upper Egypt and the Red Sea, as well as a major crossing point of the Nile from the west bank at Giza via Rawda Island (Sheehan Citation2012, 103–115). Moreover, proximity to the Nile was of fundamental importance for activities such as delivery of raw materials, water provision, and access to markets. The waterfront’s importance to Fustat’s commercial activities after the Arab-Islamic conquest is clear from parts of the still-active Late Antique infrastructure in the area, including the Trajanic stepped quayside, transport links such as a bridge across the Nile, the Red Sea canal (the mouth of which was recut to the north: Sheehan and Gascoigne Citation2022), and granaries attested by papyrus receipts (Egyptian National Library Inv. No. 126, dated a.d. 706: Grohmann Citation1952, no. 286, 242–245; P. Vind. 6 474, dated 7th/8th century a.d.: Sijpesteijn Citation2013, 75).Footnote1 Another papyrus from a.d. 705 mentions an ironworks at Babylon (P. Lond IV 1421: Bell Citation1910, 242; Dennett Citation1950, 104). This commercial infrastructure was heavily impacted by the destruction of a.d. 750 (Bruning Citation2018, 19–20), but both historical and archaeological evidence point to industrial repurposing along the gradually westward-shifting riverside as the precursor and perhaps the stimulus to subsequent recovery in this area. At the Monastery of Abu Sayfayn, for example, originally located on the pre-Islamic riverbank, an abandoned church was used for sugar-cane refining in the period prior to its reconstruction in the late 10th century a.d. (Abu Salih Citation1895, 117).

Pottery production ca. a.d. 800-1000 (and later): Istabl ‘Antar

The earliest direct, well-dated evidence of pottery production comes from Istabl ‘Antar, excavated by Roland-Pierre Gayraud between 1985 and 2005, and confirms the spread of ceramic industries across a wide area in this period. This southern part of Fustat featured an Umayyad mosque and aqueducts, as well as ‘Abbasid elite burials (Gayraud, Björnesjö, and Denoix Citation1986; Gayraud, Björnesjö, and Speiser Citation1994; Gayraud and Peixoto Citation1993; Gayraud et al. Citation1987, Citation1991, Citation1995). Some industrial activity was, however, also evidenced: Gayraud excavated a kiln producing small bottles of alluvial clay, constructed within an ‘Abbasid mausoleum after it ceased to be an active funerary monument at the start of the 9th century a.d. (Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 39–46). Further evidence for the production of small bottles or sphero-conical vessels came from excavations directed by Mamdouh al-Said near the Fatimid Saba‘ Banaat mausolea just north of Istabl ‘Antar (Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 21; P. Sheehan and A. Gascoigne, personal observation). The Istabl ‘Antar kiln’s products are of standardized size, appearance, and technology. From the same phase came a kiln bar with traces of turquoise glaze, indicating glazed-ware production from the early 9th century a.d., while a pit dated to the end of the 9th century a.d. yielded wasters of water-lifting jars (qawadi, sing. qadus; Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 19). The kiln was thoroughly demolished prior to Fatimid reuse of the area, with leveling layers dated to the end of the first half of the 9th century a.d., followed by the construction of a garden with ornamental basin ca. a.d. 973 as part of a wider renovation of the necropolis. Further turquoise-splashed kiln bars came from levels reshaped during this Fatimid reoccupation at the end of the 10th century a.d. (Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 19–20). Wasters of “Fustat Fatimid Sgraffito” (FFS) glazed wares (turquoise; green; yellow; and, white splashed with cobalt blue) were also found; these may date to the end of the 10th or start of the 11th century a.d. but here presumably pre-date the Fatimid reoccupation (Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 20). The same may be true for the extensive evidence of ceramic production from the northern part of the excavations: wasters of cups/bowls like those from the Roman tower (dated to the 10th century a.d.: see below), water jars (qulal, sing. qulla) with filters, and spouted jugs, all of calcareous clay (calcareous, alluvial, and silicious clays were here in use simultaneously); the associated workshops were thought to lie beneath housing constructed since 1987 (Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 20–21, 30). Subsequent phases of activity at Istabl ‘Antar indicate ceramic production in the late medieval period: wasters of stacked and fused plain green-glazed (“pseudo-celadon”) bowls perhaps from the 15th century a.d. were found in occupation levels inside the remains of an ‘Abbasid cistern (Gayraud and Treglia Citation2012). Given the destruction of the upper archaeological layers of Istabl ‘Antar in the 1940s, further evidence of late Medieval and early modern industrial activity has no doubt been obscured (Gayraud and Treglia Citation2012, 297).

In this part of Fustat, then, a fairly intensive phase of industrial use in the 9th century a.d. was sandwiched between two periods of high-status activity, all prior to the known “abandonments” of the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries a.d., and the subsequent re-emergence of ceramic production in the 15th century a.d. Industrial infrastructure was constructed in “abandoned” areas, but uncharacteristically (see below), the “abandoned” area was funerary, not residential, in function. The area was subsequently reoccupied for funerary use, then once more abandoned, before being reused industrially. These excavations thus show multiple transitions between high- and lower-status activities, some reflecting elite decision-making, but others no doubt involving elements of grassroots initiative, self-organization, and opportunism.

Pottery production ca. a.d. 800–1000: the riverside

Ceramic production was thus underway in the southern zone of Fustat by the 9th century a.d. at the latest. The waterfront remained important for the development of industry throughout the medieval period and comprised first the existing pre-Islamic riverside zone, consolidated following the blocking of the Trajanic Red Sea canal ca. a.d. 700 (Sheehan Citation2010, 86), and then new land created by the westward-shifting Nile. The formation of new land west of the fortress may have happened quite quickly and appears to have accelerated between the 10th and mid-14th century a.d., perhaps triggered by the reported destruction during the Fatimid conquest of the pontoon bridge between Babylon and Rawda (Cooper Citation2014, 187–194; Sheehan Citation2010, 49, 86, 103). In the later medieval and early modern periods, toponyms (Denoix Citation1992, 86–91) and cartography (Description de l’Égypte, État Moderne I, pl. 16) indicate a mixed commercial, industrial, and residential zone, with activities tied to the Nile (fishing, loading boats, and drawing water). Streets running between Old Cairo and the riverfront tracked this shift, with the Description plan showing a route leading from the river to the heart of the former fortress where an Ottoman sabil (public fountain) now stands; it was only with the construction of the Cairo-Hulwan Light Railway (now the Metro) in a.d. 1889 that this relationship was obscured and the link severed.

The Old Cairo Groundwater Lowering Project excavations revealed significant new evidence for ceramic production, well established by the 10th century a.d. and possibly somewhat earlier. This was located in repurposed structures of the riverside Roman fortress, the surviving towers of which were annexed and reused in various ways. This activity, with the evidence from Istabl ‘Antar, probably represents an ‘Abbasid-era industrial zone on the city’s periphery, similar to that at Raqqa (Henderson et al. Citation2005). This industry thrived and then shifted location following a major urban revival in this part of Fustat around the end of the 10th century a.d., evidenced by both historical sources and excavations at a number of locations that point to the renovation of ruined churches and the conversion of others to synagogues, both trends reflecting the Fatimids’ need for minority support (Sheehan Citation2010, 92–96). These structures were located within the southern half of the fortress, which, unlike the northern half, had not been annexed for elite purposes under Umayyad rule and which took on its present distinct character as a Christian and Jewish enclave from the Fatimid period onwards. Here, then, an industrial phase preceded revival of the area, similar to the abovementioned sugar refineries in the church at Abu Sayfayn, which was also renovated at this time.

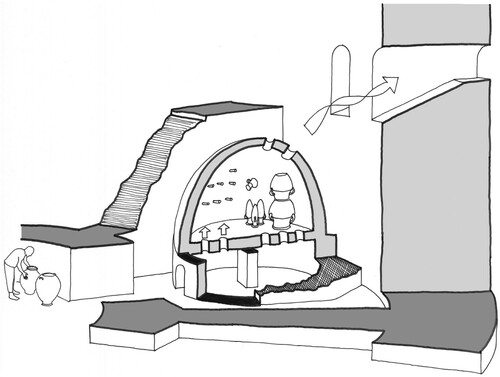

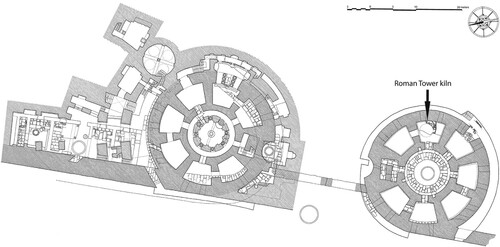

The most important evidence for this riverside industrial zone is a pottery kiln found inside the massive southern round tower of the Roman fortress (one of a pair originally located on the riverfront guarding the entrance to the Red Sea canal) associated with production of polychrome-glazed wares, a type simultaneously produced in Istabl ‘Antar with uncertain evidence for production in central Fustat (discussed below). Gayraud and Vallauri (Citation2017) note the appearance at Istabl ‘Antar of polychrome-glazed wares decorated in green and brown (often loops) over white in pits dated to the second half of the 9th century a.d., while more complex splashed designs and color schemes appeared from the first half of the 10th century a.d. Vessels decorated in radiating lines date from the second half of the 10th−11th centuries a.d., continuing into the 13th century a.d. “sous des formes et des décors appauvris” (Gayraud Citation1997, 264; Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 355). These types are distinguished in our corpus, termed FG16 (green and brown/black on white) and FG12 (yellow, green, blue, white, black, splashed, and/or in radiating lines).Footnote2 It thus seems clear that the Roman tower kiln, producing FG12 wares, flourished during the 10th century a.d. (and perhaps just into the 11th century a.d.: an example similar to some of the Roman tower sherds is “[u]n type plus ‘classique’ du XIe siècle:” Gayraud Citation1997, 266–268, fig. 10). The presence of FG12 wasters in the layers beneath the kiln (see below) suggests cycles of activity, including the replacement of derelict kilns with new ones.

The Roman tower kiln was partly ruined when first noted and further collapsed following groundwater draining and resulting settling of the sherd dumps upon which it was built (). It was apparently first exposed during restoration work in the early 1980s: it does not appear in photographs of the tower from the archive of the Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l’Art Arabe taken during excavations in 1948, which show what appears to be a late Medieval or early modern tomb with a stairway overlying the kiln’s location.Footnote3 The kiln is a circular fired-brick updraft structure, fitted into one of the trapezoidal ground-floor rooms of the round tower. It comprises an octagonal, probably originally domed, pot chamber with a circular interior (diameter 3.4 m) set over a lower vaulted firing chamber (diameter 1.8 m). Enough of the upper structure originally survived to show the position of air vents and the presence of an access hatch for arranging pots. The vents were located to draw air via the ground-floor windows of the tower at a time when the ground level outside was considerably lower than at present (ca. 25 masl). The ground level around the kiln (18.7 masl) is 1.3 m above the 17.4 masl of the original Roman period ground level inside the tower, perhaps due to build-up from previous cycles of abandonment, kiln construction, use, and destruction (and deliberate leveling dumps: see below). The kiln’s situation shows that the northernmost wall of its room was still in place at the time of its construction. Most of this wall and a large section of the kiln were subsequently removed, probably concurrently during construction of the abovementioned tomb.

Figure 5. The round Roman riverside towers, with the surviving kiln in an eastern room of the southernmost (N. J. Warner/P. Sheehan).

Figure 7. The Roman tower kiln. A) In 2001, during drainage works within the tower, prior to the collapse of the floor. B) In 2011, after excavation during preparation of the tower for public access (P. Sheehan).

Like other elements of the fortress reused in early Medieval times, the kiln was constructed directly over a ca. 1 m thick (the bottom was at 17.8 masl) ceramic dump, probably brought in to level existing features or to consolidate waterlogged land, providing a solid building surface. A significant proportion of the sherds within this layer came from the common Egyptian silt amphora LRA7, in use to the mid-9th century a.d., many with the corkscrew bases, chaffy fabric, thick walls, and angular shoulders associated with the latest types in Old Cairo (Gascoigne Citation2007, 166; Peacock and Williams Citation1986, 204–205, class 52; Riley Citation1981; Vogt et al. Citation2002). Also present were Aswan red-slipped fine wares (used until the 10th century a.d.: Gayraud Citation1997, 263), Aswan ware W12 (9th century a.d.−ca. a.d. 1300: Adams Citation1986, 557–559; Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, pl. 27, 7803-2, pl. 37, 5624-3), Aswan amphorae (Gascoigne Citation2007, 167), bag-shaped silt jars (second half of the 7th century−9th century a.d.: Engemann Citation1992; Citation2016, 114–115), cream-slipped and brown-striped silt qulal (water jars; 8th−9th century a.d.: Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, pl. 33, 10762-1; Scanlon Citation1981, 68, fig. 32), and green marl qulal of the late 8th century a.d. onwards (Pyke Citation2020, 212–214). As noted above, a few FG12 sherds were also present, indicating a relatively close chronology between the dump and the overlying kiln. A date for this assemblage around the 9th century a.d. seems reasonable; the FG12 sherds may indicate deposition towards the later end.

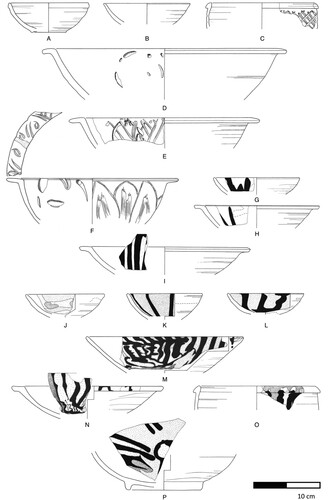

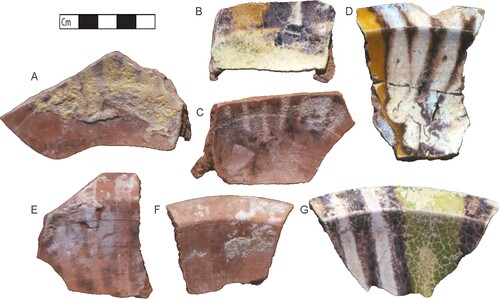

Debris around the kiln walls was largely associated with FG12 production, and many FG12 sherds and wasters, mainly small- to medium-sized bowls, were retrieved; the sheer quantities identify these as the primary product. Our excavations uncovered fragments in various stages of completion, including unglazed “biscuit” wares and vessels coated with fugitive glaze (not refired?) and plain and glazed examples of identical forms (, ; Supplemental Material 1). The products’ formal variability was relatively low, dominated by a small number of open forms, although the striped and streaked glazing manifested in a range of colors and designs. Many biscuit sherds were splashed with glaze dots, often in several colors; some bore marks of ring-bases on their interior walls and had apparently been used after breaking, in some cases more than once, to support vessels during firing. Also found were two glaze-splashed ceramic kiln batons; other batons came from 9th−10th century a.d. deposits at Istabl ‘Antar (Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 19–20). These are paralleled from a 10th century a.d. kiln in Tiberias; from Antioch and in Sirjan, Nishapur, and Merv at about the same date; from 11th/12th century a.d. contexts in Raqqa; and, from late 13th−14th century a.d. Jerusalem (Milwright Citation2010, 204, fig. 7.3 [6]; Stern Citation1995, 58). At Nishapur, batons were set in rows into the walls of kilns dated after the first quarter of the 11th century a.d. to the Mongol conquests and were interpreted as supports for vessels during firing (Molinari Citation1997, fig. 1; Wilkinson Citation1974, xxxvii–xl, fig. 16). The Roman tower batons were of similar fabric to the FG12 bowls, probably a marl-silt mix (Mason and Keall Citation1990, 174, “Polychrome glaze wares,” first petrofabric; fabric descriptions in Supplemental Material 1).

Figure 8. A selection of polychrome-glazed (FG12) bowls and related forms associated with the Roman tower kiln. A–F) Unglazed biscuit vessels. G–I) Vessels with fugitive glaze. J–P) Glazed vessels (G. Pyke/A. L. Gascoigne).

Figure 9. Fragments of polychrome-glazed vessels discarded at various stages of production. D) = N, E) = I, and F) = H. (A. L. Gascoigne).

How did the Roman tower kiln fit into the urban landscape? Outside the tower, another kiln of similar construction was noted abutting the massive stone wall built between the two round towers of the fortress probably around the end of the 7th century a.d. to block the canal entrance (Sheehan Citation2010, pl. 23). It is tempting to interpret these features together as representing an industrial zone that developed, probably from the 9th century a.d., on new ground formed by this closure. This is supported by archaeological evidence from shafts sunk in Mari Girgis Street during the Old Cairo Groundwater Lowering Project, which yielded material and structural evidence contemporary with the Roman tower kiln, and is paralleled by the similar processes underway at Istabl ‘Antar.

During the Fatimid-era revival of Old Cairo, other structures of the fortress were reused by different groups, perhaps because of their condition after a long period of abandonment following the destruction of a.d. 750. The South Gate and the northern round tower were converted into the (Coptic) Church of the Virgin (its popular name, the Hanging Church, reflects its relationship to the underlying gate) and the (Greek) Church of St. George, respectively. The earlier patriarchal Coptic church of Abu Serga and the nearby Church of St. Barbara were completely rebuilt ca. a.d. 1050. The Jewish enclave in Old Cairo was a new feature of this Fatimid revival, with the Ben Ezra Synagogue located in another church ruined in a.d. 750 and abandoned (Sheehan Citation2010, 92–96). Nor was the southern round tower the only part of the fortress converted to industrial uses: Geniza documents indicate that towers on the eastern wall were used for Jewish-owned workshops into the 12th century a.d., indicating potential continuity of industrial activity through the revival period (Goitein Citation1999, 47–48).Footnote4 Nonetheless, it is likely that the Abbasid-era industrial zone in Babylon and southern Fustat contracted and substantially relocated from Fatimid times.

In summary, then, the riverside was industrial in character from Late Antiquity, and these activities increased significantly at least from the 9th century a.d., taking advantage of locations still partly derelict or unused after the events of a.d. 750. Renovations of religious and residential structures close to the riverside in Fatimid times probably reduced the intensity of industrial activity in the area, although the Geniza evidence implies that it did not disappear altogether.

Pottery production ca. a.d. 1000–1200: central Fustat

Evidence for pottery production within central Fustat was uncovered during the excavations of Ali Bahgat, Albert Gabriel, and Felix Massoul, which began after 1912 and continued into the 1920s (Bahgat Citation1915; Bahgat and Gabriel Citation1921; Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930). This evidence was augmented by large-scale excavations undertaken from 1964–1972 by Scanlon and Kubiak in response to housing schemes and rubbish-dumping in the north and east of the site. This pioneering work excavated zones that had been broadly residential between the 9th and 11th centuries a.d., with densely clustered large and medium-sized houses overlain by extensive later rubbish mounds. Scanlon and Kubiak established a complex sequence of activity and clarified the ceramic and artifactual assemblages. These and related excavations (El-Hawary Citation1933; Mehrez Citation1972) have been re-evaluated by Matthew Harrison (Citation2014, Citation2015).

Explicit evidence for ceramic production during this period in central Fustat is minimal. Bahgat and Massoul note numerous wasters of lustreware from their excavations (Citation1930, 21), but those illustrated are imperfect rather than completely spoiled. The production of FFS may be suggested by Scanlon’s reference to archaeological finds of wasters in Fustat-A and Fustat-B (Citation1967, 75–6; Citation1999, 265; see also Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, color plate 4d). Unprovenanced FFS wasters are present in the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) (e.g. 398-1887, 398A-1887), while production of FFS tiles is indicated by an unfinished and spoiled example excavated by Bahgat and Massoul (Citation1930, 93, pl. N, fig. 131). Scanlon notes the presence of earlier, polychrome-glazed (“Fayyumi”) wasters in unspecified part(s) of Fustat but does not identify their type(s) (Citation1993, 295); these wasters are not illustrated, but a tendency to apply the term “waster” to sherds with minor aesthetic imperfections might lead us to interpret at least some of the evidence for Fatimid-era ceramic production in central Fustat with caution. Scanlon’s preliminary reports do describe industrial workshops of Fatimid/Ayyubid date, but his subsequent revisions of his own chronology (see below) reveal that these are all likely to be later, even where Scanlon did not explicitly revisit their dating. For this period, then, we must conclude that the core of Fustat was largely residential, with minimal if any ceramic production.

Pottery production ca. a.d. 1200–1500: central Fustat

Excavations in central Fustat uncovered unequivocal evidence for ceramic manufacture in the 13th−15th centuries a.d. Scanlon’s excavations in Fustat-A, east of the Mosque of ‘Amr, uncovered a large ceramic manufacturing facility (Scanlon Citation1965, 18–22). Finds included clay deposits (“buff-ware”), puddling pits, grinding emplacements, a glass kiln and ingots, and a large pottery kiln, apparently updraft. The facility was initially dated to the Ayyubid period, ca. a.d. 1170–1250, on the basis of masonry techniques and associated finds. However, both the function and date of the complex were subsequently reinterpreted, the latter to the Mamluk era (Kubiak and Scanlon Citation1980, 88, n. 46). The wares produced were not described, other than the presence of clay tripod separators, some still adhering to imperfectly fired sherds; this, with the glass ingots and grinding facilities, indicates production of glazed wares. A large Islamic-era pottery kiln was also present in Fustat-C, but no details of date or wares were reported (Kubiak and Scanlon Citation1989, 1–2; Scanlon Citation1982).

Bahgat and Massoul likewise discovered a 14th century a.d. potters’ quarter east of the Mosque of ‘Amr, running southwards from the tomb of Abu al-Su’ud (Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, 28–31). Their excavations yielded around 20 kilns, most poorly preserved (Bahgat Citation1915, 234, n. 2). The best preserved of these, destroyed during earthworks on Kom al-Garih during the 1980s (Kubiak Citation1987, 35, 138, n. 17), was an oval 1.65 × 1.5 m updraft kiln. The single hole in the center of the firing-chamber roof would have allowed flames and smoke to come into contact with the pottery, making control of conditions difficult. The excavators found no evidence for the use of saggers or shields, and Bahgat describes typical wasters being damaged on one side due to uneven firing (Citation1915, 235, fig. 2; Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, pl. B, 13, 13a). Wasters around the kiln comprised “imitation celadon,” and blue-and-white, black-and-turquoise, and blue/black-and-greenish-white underglaze-painted wares, all with sandy fabrics (Bahgat Citation1915). Wares were fired in mixed batches, as evidenced by fused pieces (Bahgat Citation1915, 240), as well as wasters in the V&A.Footnote5 Manufacture of unglazed wares was evidenced only by a waster and an example still adhering to its plaster prototype of decorative mid-Fatimid−14th/15th century a.d. qulla (water jar) filters (Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, 89, pl. LIXbis, fig. 122). Bahgat’s excavations also uncovered items of kiln furniture, including small clay tripods for separating vessels, and cylindrical clay stands (Bahgat Citation1915). However, no batons were noted, and the examples discussed above predate Bahgat’s kilns by several centuries. Also notable are plaques with glaze tests, including lustre glaze (Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, 27, pl. B, figs. 20–21).

Further evidence for the widespread nature of 13th−15th century a.d. ceramic production in Fustat (in addition to that from Istabl ‘Antar, discussed above) came from Scanlon’s evaluation of the poorly stratified upper levels of mounds in Fustat-B. Wasters of 13th century a.d. blue/black-and-white and black-and-turquoise underglaze-painted wares were identified, as were abundant wasters of 13th−14th-century a.d. “imitation celadon” (Scanlon Citation1971, 230; Citation1984b, 118–119). Blue-and-white underglaze-painted wasters, dated to the 14th−15th centuries a.d., were also abundant (Scanlon Citation1984b, 118).

Evidence from these large-scale excavations for the existence of areas of mixed residential/industrial use within Fatimid-era central Fustat is thus negligible. But the expansion of ceramic manufacture across the core of the site during the 13th−14th centuries a.d. represents a major shift in land use in favor of industry. It followed periods of decline in the 11th−12th centuries a.d. during which much of the population relocated northwards to other parts of the urban conglomeration, in particular al-Qahira. The nuances of the processes by which this played out from one locality to another cannot be fully established from Bahgat’s and Scanlon’s excavations, but Geniza documents from other areas of Fustat (discussed below) suggest mechanisms for this gradual process of industrialization from a.d. 1201 (Goitein Citation1999, 49, 51, 54), with the tipping point concurrent with the departure of wealthier members of the community. We suggest that there was a quantitative difference from around the mid-13th century a.d., with whole areas given over to potteries. The location of so many of the workshops listed by Ibn Duqmaq in central and northern Fustat (discussed below) likewise testify to this northerly shift or spread, notwithstanding the chronological uncertainties of this text.

Pottery production ca. a.d. 1500–2000: central Fustat and the riverside

The reduction in Cairo’s population caused by the Black Death from the mid-14th century a.d. certainly impacted demand for commodities. In the southern parts of the city, stagnation is notable until ca. a.d. 1800, no doubt reflecting complex economic and social trends including Egypt’s connectedness within the Ottoman world, of which it formed a part from a.d. 1517, and the shift of riverine activity northwards to Bulaq (Sheehan Citation2010, 115). We have no explicit evidence for ceramic production at this time, but the subsequent expansion of Cairo’s rubbish mounds may have pushed industrial activity, including potting, southwards towards Istabl ‘Antar, where post-Medieval levels were, however, truncated in the archaeological sequence (Gayraud and Vallauri Citation2017, 8).

There is both archaeological and historical evidence that the area around the Roman fortress saw increasing industrial activity, including lime kilns, iron foundries, and ceramic production, from the 18th century a.d. onwards, perhaps reflecting a continuation or resurgence of the southern extent of Mamluk-era industry (Sheehan Citation2010, 115–120). Of specific interest is the former fawakhir (potteries) area, also known as al-Qulaliya (Golvin, Thiriot, and Zakariya Citation1982, 1), to the south and east of the Mosque of ‘Amr. The area around the mosque had formed the core of the Umayyad capital and was probably the location of important public buildings that did not survive the destruction of a.d. 750. Re-settled in the Fatimid period, it was abandoned and robbed out following the upheavals of the 11th century a.d., then rebuilt and again abandoned ca. a.d. 1300 after the shift of the seat of power from Rawda to the Citadel (Sheehan Citation2010, 88, 99, 112–115; Sheehan and Gascoigne Citation2022). Prior to January 1998, the northern and eastern part of the fawakhir site still hosted a large concentration of modern potters’ workshops, covering some 4–5 ha (Golvin, Thiriot, and Zakariya Citation1982; ). The workshops were then bulldozed by the Cairo Governorate and eventually replaced by a public garden, which was completed in 2008 but has now been removed by the ongoing Fustat Hills Park development.

To establish the nature of late Medieval activity in this area, an archaeological evaluation was undertaken by the Old Cairo Archaeological Project in 1999, following 1998 excavations on the site by a team under Mutsuo Kawatoko (Kawatoko Citation2005, 845–848; Sheehan et al. Citation2000). The archaeological deposits revealed were complex and disturbed by subsequent, repeated digging for kiln-building into modern times. The evaluation revealed deep dumps of Mamluk-era pottery overlying the sparse, robbed-out remains of buildings (). As with similar sites explored within the walls of Babylon, at the Wedding Hall in 2002, and the Convent of St. George in 2004 (Sheehan Citation2010), this final occupation level appeared to represent the foundations of stone structures forming part of an Ayyubid/early Mamluk redevelopment built over leveled Fatimid-era brick buildings. Excavations in the western part of the fawakhir site led by Muawad Hassan Hussein in 2002 revealed comparable evidence, uncovering the relatively modern kilns (similar to features exposed by Kawatoko) mapped in the 1970s by Golvin, Thiriot, and Zakariya (Citation1982), which cut through the substantial remains of earlier, probably Fatimid-era, brick buildings (P. Sheehan, personal observation). No direct evidence for ceramic production came from layers pre-dating the modern kilns. The origins of the modern fawakhir industries, then, should be sought in the period after the final Ayyubid/early Mamluk occupation, post-dating the Mamluk-era dumps.

Beyond this, the date of the first fawakhir workshops is obscure. In the a.d. Citation1809 Description de l’Égypte (État Moderne I, pl. 16), the area is depicted as a depression surrounded by debris mounds, labelled “Carrières” (quarries), which are probably to be identified as products of the extensive robbing and turning over of the site that continued into the early 20th century a.d. The kilns and potters’ workshops are not shown on the Description plan, although the accompanying text references potters in the vicinity of the Church of St. George (i.e. the area around the Roman fortress) and provides a description and drawings of their methods and installations (Description, État Moderne II, pl. 2). This might suggest their presence near the mounds of debris around the fortress. The first unequivocal evidence of the fawakhir potteries dates from a.d. 1897, where they are shown on the “Plan Général de la ville du Caire” (Citation1897) of the Ministry of Public Works. An ethnographic study of these potters was undertaken in the late 1970s, when there were 72 kilns on the site, organized into larger/richer and smaller/poorer family-run workshops clustered together, staffed by potters including older children and unrelated employees, and—in a break from centuries of fine wares—producing coarse wares (Golvin, Thiriot, and Zakariya Citation1982, 81–86).

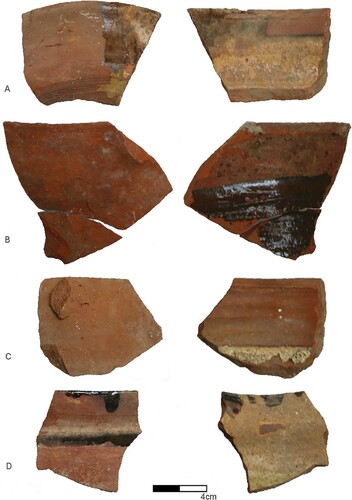

Possible traces of the potters at the Church of St. George mentioned in the Description were identified around the Roman tower kiln (discussed above) in the form of cooking pot wasters of various forms, their interiors thickly coated with dark-brown glaze (Old Cairo ware FG10b; ). These came from the uppermost strata in the room, which were disturbed and insecure. This material awaits further study but probably indicates production in relatively recent times.

Figure 12. A selection of brown-glazed silt (FG10b) cooking pots produced in the vicinity of the Roman tower kiln, exterior (left) and interior (right) views (A. L. Gascoigne).

Although the fawakhir potteries were cleared in 1998, the tradition of ceramic production continues on the site at the Fustat National Ceramics Centre, located between Babylon and the Fustat archaeological area (Abdulfattah Citation2010). This small institution houses artisans who produce studio pottery, often drawing on Egyptian and wider Islamic ceramic traditions, including those that flourished in Fustat a millennium ago.

The Organization of Fustat’s Ceramic Industries

Having sketched what we know of the locations of ceramic production from the 8th century a.d. to the present, we will now consider how these industries might have been organized and regulated in order to better understand their relationship with the wider city and its inhabitants. Additional evidence for this comes from Medieval written sources, specifically the Geniza documents and the narrative accounts of Ibn Duqmaq and al-Maqrizi. These indicate that the localized fluctuations in urban prosperity outlined above provided loci for industrial initiatives to meet the growing material needs of the city’s increasing population (Fustat’s industries were surely stimulated by the expansion of the metropolis of al-Qahira from the 10th−14th centuries a.d.). These loci often took the form of workshops established in areas that were wholly given over to industrial activity, but they could also exist amongst non-industrial neighbors. In the latter case, regulation could address the nuisance of pollution, as evidenced by Geniza documents regarding a 13th century a.d. glass-maker and a perfumer in the vicinity of the Ben Ezra Synagogue and a dyer in an unspecified residential neighborhood, whose activities were curtailed for the comfort of nearby residents (Ben-Sasson Citation1994, 208; Goitein Citation1999, 50–51). The Geniza archive is useful more generally in elucidating the transitional processes by which workshops occupied empty house-plots. Throughout the “classic” Geniza period (10th−13th centuries a.d.), documents frequently mention ruined structures: gifted, bequeathed, sold, or excluded from sale, rented, used for storage or occupation, neglected, rebuilt, and, when completely empty, sometimes confiscated (Goitein Citation1999, 49–54). There was a significant increase in vacant premises after a.d. 1200, by which time the more affluent of the Jewish community had largely moved from Fustat to al-Qahira (Ben-Sasson Citation1994, 207–208; Jefferson [Citation2022, 61–62] suggests that part of Cairo’s Muski quarter was settled by Jews around this time). The impression from the Geniza that Fustat’s various industries were organized as multiple individual small-scale enterprises—local, informal partnerships of artisans (like the 20th century a.d. fawakhir potteries, discussed above)—indicates activity that would be adaptable to whatever spaces became available. Workshops could also be inserted into the qa‘at (halls) of occupied houses (Goitein Citation1967–1988, 4:69–70). As part of these transitional processes, potting communities must have interacted with, and been interspersed among, a diverse urban population.

Later Medieval narrative sources elucidate this relationship, as well as the practical organization of workshops, including social, economic, administrative, and regulatory ties to the wider community. Ibn Duqmaq (d. a.d. 1407) wrote a nostalgic topography of Fustat in which he noted the (current or former) locations of a number of ceramic workshops (summarized in ), most of which can be assigned broadly to areas of the city (Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, 10–12; Milwright Citation1999, 505; see also Golvin, Thiriot, and Zakariya Citation1982, xi). Beyond the general area, the exact locations of these facilities remain unclear. Interpretation of Ibn Duqmaq is challenging given the presentation of the city as a lieu de mémoire (Denoix Citation1996; Rabbat Citation2000, 24). Nonetheless, his account reinforces the impression from the Geniza documents of multiple, small, independent workshops, some named for an individual (founder, leading potter, head of household, owner, or investor?), integrated into the urban fabric of a neighborhood, sometimes close to important public structures and sometimes replacing structures with other functions, including housing. The majority seem to be near the riverside or in areas where residential functions had already given way to industrial/mercantile ones.

Table 3. Ceramic-related features mentioned by Ibn Duqmaq (d. a.d. 1407), their urban context, and their suggested locations.

Further evidence for the social and technical organization of workshops comes from study of their products, and an examination of Fustat sherds in the V&A indicates the potential of this approach (A. Gascoigne, personal observation, with thanks to Mariam Rosser-Owen; see also Milwright Citation1999; Walker Citation2004). Analysis of sherds bearing names or “signatures” indicates variation: few examples of lustreware were signed, but signatures are common by the time underglaze-painted wares dominate. This correlates with other evidence for changing attitudes to and the status of craftsmen, and organization of production, between the 12th−14th centuries a.d. (Walker Citation2004). Blue-and-white underglaze-painted pottery appears more commonly signed than contemporary black-and-turquoise underglaze-painted ware (perhaps connected with the signing of Chinese blue-and-white); Mamluk sgraffito is likewise less commonly signed, at least in the Bahri period (Walker Citation2004, 42–54). This indicates a variety of conceptual approaches to production, and signatures cannot be considered to communicate consistent information across different wares. Diversity of production within a single workshop is indicated by the presence in the V&A of lustreware sherds with both proto-stonepaste and earthenware fabrics bearing the signature Sa‘d and wasters of different wares produced and fired together. However, the Geniza archive supports some specialization of production, with drainpipes, narrow-necked, spoutless water jugs, and “porcelain-like translucent dishes” (stonepastes?) produced by separate artisans (Goitein Citation1967–1988, 1:110–111). There is no reason to assume consistent practice by all pottery workshops. A more detailed investigation of Fustat’s products has the potential to reveal further significant insights.

Regulations regarding the manufacture of pottery are noted in 14th century a.d. hisba (market regulation) manuals: requirements included the use of particular fabrics for vessels of certain form or function; regularizing shape, size, and glazing; and, the use of specific glaze pigments, fuel types, and firing levels (Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, 12–14; Milwright Citation1999, 508; Walker Citation2004, 35–45). Clearly, the muhtasib (market inspector) aspired to as standardized a range of products as possible given the disparate nature of production.

A further question relates to the location of potteries making coarse wares. Gayraud suggests that the needs of a large urban center might increase diversity of production within workshops (Citation1997, 262–263). Walker proposes that the term (fakhkhurah) used for workshops by Ibn Duqmaq indicates coarse ware production (Citation2004, 38–39). However, such terms are difficult to define precisely and consistently, and beyond the evidence from Istabl ‘Antar and the fawakhir area, coarse ware production is almost entirely archaeologically unreported to date. Unglazed wasters (except biscuit wares) were not found around the kiln excavated within the Roman tower of Babylon, nor are they convincingly noted (although perhaps under-reported?) from other excavations; the numerous ceramic workshops attested archaeologically in Fustat apparently produced glazed wares almost exclusively. Where, then, were the potteries serving Cairo’s coarse ware needs? Roger Bagnall argues that, in Late Antiquity, potting was primarily a rural industry, located near clay sources but with limited transportation of clay to urban centers for fine ware production (Citation1993, 84–85, 129). Fuel for kilns was likewise imported to Fustat from the countryside: Ibn al-Ukhuwa’s (d. a.d. 1348) hisba manual notes the use of dung (Walker Citation2004, 41), while large quantities of halfa grass were brought to Fustat as a fuel in a.d. 1552–1553 (Michel Citation2018, 392–393, 410–411). Assuming continuity of practice, coarse wares were presumably shipped to Fustat, as they were in the 18th−20th centuries a.d., when rafts and boats brought jars northwards from Qena and Ballas to markets in Cairo, Damietta, and elsewhere (Cooper Citation2011). Having said that, the number of small, thrown-off-the-hump, low-fired, disposable silt bowls (used as take-away food containers) recorded during our Old Cairo excavations and in those at the walls of al-Qahira, where they represented ca. 30% of the Mamluk-period assemblage (Monchamp Citation2018, groupe 250), implies substantial production of coarse wares somewhere nearby—perhaps in the city’s immediate hinterland (like Kolkata’s modern bhar teacups, made in a northern riverside suburb of the city: Gustafsson and Mostafa Citation2016).

Clay-gathering is evidenced in the Fustat area, perhaps organized by dedicated collectors, the product differentiated into grades and sold to potters (Milwright Citation1999, 508). Al-Maqrizi notes the use of Nile silt, while Abu Salih records the use of yellow clay from an east-bank village called al-‘Adawiyya ca. 18 miles south of Old Cairo and, less certainly, from Habash (Birkat al-Habash, near Fustat) for glazed wares (Abu Salih Citation1895, 131, 136, n. 4, 141; Milwright Citation1999, 508; Monchamp Citation2018, 33); al-‘Adawiyya’s location corresponds to the modern industrial area of Hulwan.Footnote6 Recent Fustat potters acquired raw material from al-Tibin (Golvin, Thiriot, and Zakariya Citation1982, 6) at the southern limits of the city in the region still known as Dayr al-Tin (“monastery of clay”) and shown on the Description de l’Égypte plan of Old Cairo in the location of the suburb of al-Maadi (Etat Moderne I, pl. 16); when this clay source was first exploited is unknown. Clearly, clay was available outside but close to the city and perhaps within it as well.

Pot vendors were also present. A Geniza document from a.d. 1104 mentions “the shop known for the sale of oil and pots in Fustāt at the gate of Qaṣr ash-Sham‘, known as the Gate of the Turners” (Worman Citation1905, 26; see also Goitein Citation1967–1988, 1:83). This gate is not known from other sources but probably lay on the western side of the fortress, i.e. in the waterfront industrial area of which the Roman tower kiln formed a part.Footnote7 We have already noted Ibn Duqmaq’s market of fish and pottery near Abu Sayfayn, surely near the river. The fair sale of pots, as other commodities, was regulated under authority of the muhtasib by designated craftsmen: lists of pot-sellers’ obligations feature alongside those of producers in hisba manuals, identifying common scams (Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, 12–14; Milwright Citation1999, 508–509). Injunctions refer to the quality of objects sold, description of the range of quality on offer, buyers viewing purchases to agree a price as seen or duplicates to be of equivalent standard to a specimen, porterage, and passing off repaired seconds as undamaged. For uncertain reasons, sellers were required to sell ghadar (luxury wares? stonepaste?) vessels fired in large and small kilns separately. Hisba regulations for pottery repair relate to the nature of ingredients in glues. Contravening these injunctions led to public exposure with the object of shame around one’s neck (Bahgat and Massoul Citation1930, 13–14; Milwright Citation1999, 509).

Taken together, these sources indicate that fine wares were supplied to Cairene consumers by multiple workshops and commercial outlets of complex organization, with diverse economic and regulatory connections, located in proximity to landmarks and spaces of current or recent urban importance, with an embedded population of skilled workers, sellers, and purchasers. It is clear that Fustat’s “marginal” potteries were much more closely embedded into a lively and populous urban fabric than has often been assumed.

Conclusions: Fustat’s “Marginal” Industries

The principal excavator of Fustat, George Scanlon, wrote that “[t]he Old City (Misr Qadimah or Misr al-Fustat) was partially destroyed and for all practical purposes abandoned after the conflagration of November 1168” (Citation1982, 230). The term “abandonment,” with its implications of straightforward depopulation abruptly or over time, obscures the complexity of processes at play in Fustat, and we should more productively consider the urban re-purposing of the city, often specifically for practical purposes. As we have seen, Fustat saw multiple traumatic or more gradual episodes of “abandonment” alternating with periods of intense activity and growth, which played out differently in different parts of the city (Sheehan Citation2010, 79–115). One of the most important recent changes in our understanding relates to the nature of the abandonment of Fustat’s southern quarters, the two most significant episodes of which appear to have been occasioned first by the ‘Abbasid conquest of a.d. 750 and then by the economic and social upheavals of Fatimid rule in the second half of the 11th century a.d. (Kubiak Citation1976; Sheehan Citation2010; Sheehan and Gascoigne Citation2022). These abandonments were real enough. The ‘Abbasid conquest was marked by violent destruction that left much of the city in ruins, while the abandonment of Fustat at the end of the Fatimid period was effectively marked by an a.d. 1072 edict allowing people from nearby al-Qahira to remove building material from derelict structures in Fustat, suggesting a more gradual process of decline was already well under way (Denoix Citation1992, 54). In both cases, though, abandonment was neither total nor permanent. The new ‘Abbasid foundation of al-‘Askar to the north of Fustat was soon subsumed into the surviving core of the city. Equally, at least some of Fustat continued to function after the Fatimid period as an important commercial depot, with newly constructed residences of high-ranking notables located in proximity to the Ayyubid and Bahri Mamluk citadel on Rawda Island, as evidenced by our excavations in Old Cairo and at the former potteries (fawakhir) site (Sheehan Citation2010, 83, 105–112). This supports similar conclusions based on textual evidence (Denoix Citation1992; Petry [Citation1997, 274] even states that “Fustāt quite obviously made a full recovery during the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods”). Settlement also continued in much of the area of the Roman fortress, an important enclave of Christian and Jewish minorities under Fatimid rule, and along the riverfront, expanding with the later Medieval shift of the Nile westwards and surviving the decline of the Late Antique and early Islamic port in favor first of Fatimid al-Maqs and then Mamluk Bulaq (Cooper Citation2014, 187–194). It may thus be that only the areas towards the southern and eastern edges of first Umayyad and then Fatimid Fustat were ever truly “abandoned,” although in the latter case even some of these ruins were subsequently enclosed in the largely symbolic southern section of the early 13th century a.d. Ayyubid city wall (Kemp et al. Citation2004, 282–283). From the end of the 13th century a.d., the combined effects of famine, economic troubles, and severe outbreaks of plague again led to depopulation and a shrinking and repurposing of the metropolis, from which it struggled to recover until well into Ottoman times (Borsch Citation2005). It is therefore clear that cycles of boom and bust in the Medieval city were more complex and local than previous discussions of the phenomenon have tended to recognize.

Re-purposing of “abandoned” areas took various forms. Fustat experienced a range of processes including rural immigration, informal occupation, rubbish-dumping, and unwanted effects from industrial activities (for modern parallels, see Sims Citation2012). The construction of workshops and industrial installations for pottery production servicing the greater urban conglomeration indicates the continuation of urban life in these areas, albeit in different form. The concept of “urban persistence,” it has been argued, has been neglected in favor of processes of collapse; persistence is not a static state, though, and dynamic change within cities, such as that investigated here, can itself be part of a process to sustain resilience (Crawford et al. Citation2023).

Clearly, the relationship between industry and urban prosperity is complex. Pottery production in Fustat was constant from at least the 9th century a.d. to the present, with frequent changes in scale and shifts in location; we lack extensive evidence for where ceramic workshops were located at particular times, although informed speculation based on the archaeological record is possible. Fustat, and later Cairo, developed as a series of linked urban districts, each shaped by the existing forms of a physical and populated landscape; each incarnation of the city required numerous pots. Polluting industries clearly made use of peripheral areas to some extent. Prevailing breezes from the north meant that noxious industries (tanning, potting, quarrying, and lime-burning, all of which continued to some extent into modern times) could take place downwind of al-Qahira’s residential areas. The collection and sorting of the city’s garbage is another modern activity with ancient roots: archaeological evidence from Istabl ‘Antar shows that this southern edge of the city was used by garbage collectors in the wake of the ruptures following first the ‘Abbasid conquest and again at the beginning of the 12th century a.d. (Gayraud et al. Citation1991, 61, 71). The plateaux at the southern and eastern edges of the city also aided industry: several ruined windmills ascribed to the Napoleonic Armée d’Égypte (Gayraud et al. Citation1991, 72) still survive on the ridge of Kom al-Ghurab/al-Rasad in an area controlled today by the military. Mills and millers are likewise mentioned by Ibn Duqmaq and al-Maqrizi and in 12th−13th century a.d. Geniza documents, where they are located in the district of Musasa/Mamsusa, identified with al-Rasad, a part of Fustat with a strong Jewish presence located east of Babylon and accessed from the Jewish quarter within the fortress via a gate in its wall (Denoix Citation1992, 88; Worman Citation1905, 31). The separation of residential and industrial areas within Medieval Fustat was, though, less clear-cut than later Medieval legal models of idealized urban zoning, which place industry on the periphery and downwind of core urban centers, imply (O’Meara Citation2009, 8; Raymond Citation1990, Citation1998). The waterfront areas were key; parallels exist with Medieval (and modern) Fez, where tanneries are centrally located in the old city, on the river banks (Brunschvig Citation1947, 146–149; Burckhardt Citation1980, 168; thanks to Bethany Walker for this observation). We have already noted above the diversity of parallels in cities such as Raqqa, Jerash, Tiberias, and Ramla.

A number of factors might underlie the shifting of potters around the urban landscape: the gradual creep of rubbish mounds, tipping points in the “abandonment” of residential areas, changes in demand for products, or limits of government interference and taxation. At least some of the industrial activities described above may have been related to the re-use of by-products from the vast rubbish dumps of Tilul Zaynhum and ‘Ayn al-Sira that grew up close to the later Medieval city. These rubbish mounds have remained a significant feature of Cairo’s topography even down to their current rebranding as the Fustat Hills, and their dynamic growth during the city’s major expansion between the 10th and 14th centuries a.d. doubtless caused periodic shifts in the location of related industrial activities. From the later Mamluk period, turning over the site for building debris and organic-rich material to be used as fertilizer became an economically important activity. The site of Istabl ‘Antar yielded evidence of this, and the truncation it caused to later Medieval deposits, in the form of dockets, probably early 20th century a.d. in date, permitting mining of a certain quantity of material (Gayraud, Björnesjö, and Denoix Citation1986, 12). Patterns of rubbish disposal and retrieval can thus themselves be considered as drivers of urban change—beyond the creation of rubbish mounds themselves—the importance of which has been overlooked.

The evidence presented above indicates the close proximity of ceramics workshops in various areas of Fustat to residential and ceremonial sites and emphasizes the continued importance of the waterfront in the city’s industrial growth. Industry in Fustat throughout Medieval and early modern times was clearly reflexive and responsive, adapting to social and political events and cycles of growth and decline. Our study thus serves to reinforce the complex, changing nature of urban settlement in which limitations of space mean that “abandonment,” if it happens at all, is usually of limited duration before new land uses are found, whether informal or more regenerative.

Geolocation Information.

The center of the Fort of Babylon is around 30°00'23.80"N, 31°13'51.00"E.

Gascoigne_SM1_RFP.docx

Download MS Word (22.9 KB)Disclosure Statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alison L. Gascoigne

Alison L. Gascoigne (Ph.D. 2002, University of Cambridge) is Professor of Archaeology at the University of Southampton, UK. Her research interests focus on the Late Antique and early Islamic archaeology of Egypt, including Fustat, the Kharga oasis, the Aswan region, and Tell Tinnis, on which she published The Island City of Tinnis (2020). She has also worked at and published on the sites of Jam and the Bala Hissar, Kabul in Afghanistan.

Peter D. Sheehan

Peter D. Sheehan (M.A. 1998, University of York) is an archaeologist and Head of Historic Buildings and Landscapes with the Department of Culture & Tourism, Abu Dhabi. He has a particular interest in historic building preservation, site formation processes, and the development of cultural landscapes and has published widely on his work in and around the Roman fortress of Babylon in Old Cairo and the historic oasis landscape of the World Heritage Site of Al Ain in the UAE.

Notes

1 Certain features, including the presence of granaries, apparently had striking longevity: see for example the Description de l’Égypte (État Moderne I, pl. 16) marking the “greniers de Joseph” and the wheat (qamh) markets on the late 18th century a.d. riverfront.

2 Scanlon (Citation1993) dates “Fayyumi” wares to ca. a.d. 850–1150, while they are recorded as appearing “in and after the 9th century” at Raya (Shindo Citation2009, 32). An earlier appearance is proposed by Engemann for Abu Mina (Citation1990; Citation2016, 13): FG16 types in the first half of the 8th century a.d. and FG12 types from the start of the 9th century a.d., with radiating-line decoration emerging in the first half of the 9th century a.d.; also Bailey, who dates production of “Fayyumi ware” from the later 8th century a.d. (Citation1991, 205). Watson, like Scanlon, suggests that the tradition continued as late as the 12th century a.d. (Citation2004, 167).

3 The unnumbered photographs, dating from 1948–early 1950s, are in the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities archive; they show excavations following removal of houses from the northern part of the tower that preceded the construction of a new gate to the Coptic Museum.

4 Goitein (Citation1967–1988, 1:412, n. 20, vol. 2, 422) records the use of a tower adjoining the “Synagogue of the Iraqians” (between the Ben Ezra Synagogue and the Hanging Church: Ben-Sasson Citation1994, fig. 7.1) by a perfumer, who paid 6 ¾ dinars’ rent for 2 years during a.d. 1180–1184.

5 See C.229-1923 (fused proto-stonepaste sherds of black-and-turquoise underglaze-painted ware, pale green monochrome-glazed ware, and blue-and-white underglaze-painted ware), C.1317-1921 (fused proto-stonepaste sherds of monochrome-glazed ware in green-blue and dark blue and blue-and-white underglaze-painted ware), C.1322-1921 (two fused pieces with very different clay fabrics but similar olive green glaze), C.1018-1921 (fused proto-stonepaste underglaze-painted sherds in black-and-turquoise and blue-and-white), C.1258-1921 (fused proto-stonepaste underglaze-painted wares in blue-, black-and-white, and black-and-turquoise), and C.1316-1921 (fused sherds of monochrome green and black wares).

6 Abu Salih (Citation1895, 131) notes the use of clay from al-‘Adawiyya following a description of the Habash area, linked through land ownership by al-Mustansir’s vizier, Abu al-Faraj. He continues, “[a]t Al-‘Adawiyah are the quarries of yellow clay, of which the [pots called] khazaf are made; and they are to the north, on the estate of the vizier Abu ‘l-Faraj al-Maghrabi” (Citation1895, 141); by implication, there may have been clay quarries on Abu al-Faraj’s land in Habash, but the evidence is hardly explicit.

7 This was perhaps an alternative name for one of the two gates through the fortress’s western side, named by al-Maqrizi as Bab al-Hadid and Bab al-Sham (Monneret de Villard Citation1924, 81–90).

References

- Abdulfattah, I. R. 2010. “Fustat Fakharin: Throwing Clay the Classic Way.” Rawi Magazine 1, accessed 2 December 2022. https://rawi-publishing.com/articles/fakharin/

- Abu Salih the Armenian (attr.). 1895. History of the Churches and Monasteries of Egypt and Some Neighbouring Countries. Translated by B. T. A. Evetts. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Adams, W. Y. 1986. Ceramic Industries of Medieval Nubia. Lexington VA: University Press of Kentucky.

- Bagnall, R. S. 1993. Egypt in Late Antiquity. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bahgat, A. B. 1915. “Les Fouilles de Foustât: Découverte D’un Four de Potier Arabe Datant du XIVe Siècle.” Bulletin de I'Institut Égyptien 5e séries 8: 233–42.

- Bahgat, A. B., and A. Gabriel. 1921. Les Fouilles D’al-Foustat et les Origines de la Maison Arabe. Paris: E. De Boccard.

- Bahgat, A. B., and F. Massoul. 1930. La Céramique Musulmane de L’Égypte. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Bailey, D. M. 1991. “Islamic Glazed Pottery from Ashmunein: A Preliminary Note.” Cahiers de la Céramique Égyptienne 2: 205–19.

- Bell, H. I. 1910. Greek Papyri in the British Museum, Catalogue with Texts, vol. IV: The Aphrodito Papyri. Milan: Cisalpino-Goliardica.

- Ben-Sasson, M. 1994. “The Medieval Period: The Tenth to Fourteenth Centuries.” In Fortifications and the Synagogue: The Fortress of Babylon and the Ben Ezra Synagogue, Cairo, edited by P. Lambert, 201–23. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

- Borsch, S. J. 2005. The Black Death in Egypt and England: A Comparative Study. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bruning, J. 2018. The Rise of a Capital: Al-Fusṭāṭ and its Hinterland, 18/639-132/750. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Brunschvig, R. 1947. “Urbanisme Medieval et Droit Musulmane.” Revue des Études Islamiques 15: 127–55.

- Burckhardt, T. 1980. “Fez.” In The Islamic City, edited by R. B. Serjeant, 166–76. Paris: UNESCO.

- Cooper, J. P. 2011. “Humbler Craft: Rafts of the Egyptian Nile, 17th-20th Centuries AD.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 40 (2): 344–60.

- Cooper, J. P. 2014. The Medieval Nile: Route, Navigation, and Landscape in Islamic Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Crawford, K. A., A. C. Huster, M. A. Peeples, N. Gauthier, M. E. Smith, J. Lobo, A. M. York, and D. Lawrence. 2023. “A Systematic Approach for Studying the Persistence of Settlements in the Past.” Antiquity 97 (391): 213–230.

- Dennett, D. C. 1950. Conversion and the Poll Tax in Early Islam. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Denoix, S. 1992. Décrire Le Caire: Fusṭāṭ-Miṣr D’après Ibn Duqmāq et Maqrīzī. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

- Denoix, S. 1996. “Fustât, Lieu de Mémoire.” In Lieux D’Islam. Cultes et Cultures de L’Afrique à Java, edited by M. A. Amir-Moezzi, 46–59. Paris: Autrement.

- Description de l’Égypte, ou receuil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’armée française. 1809. Paris: Imprimerie impériale.

- El-Hawary, H. M. 1933. “Une Maison de L’époque Toulounide.” Bulletin de l’Institut d’Égypte 15: 79–87.

- Engemann, J. 1990. “Early Islamic Glazed Pottery of the Eighth Century A.D. from the Excavations at Abu Mina.” In Coptic and Nubian Pottery Part 1, International Workshop, Nieborów, August 29–31, 1988, edited by W. Godlewski, 63–70. Warsaw: National Museum.

- Engemann, J. 1992. “À Propos des Amphores D’Abou Mina.” Cahiers de la céramique Égyptienne 3: 153–9.

- Engemann, J. 2016. Abū Mīnā VI: Das Keramikfunde von 1965 bis 1998. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Gallimore, S. 2010. “Amphora Production in the Roman World.” Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 47: 155–84.

- Gascoigne, A. L. 2007. “Amphorae from Old Cairo: A Preliminary Note.” Cahiers de la Céramique Égyptienne 8: 161–73.

- Gayraud, R.-P. 1997. “Les Céramiques Égyptiennes à Glaçure, IX-XIIe Siècles.” In La Céramique Médiévale en Méditerranée: Actes de VIe Congrès de l’AIECM2, Aix-en-Provence (13-18 Novembre 1995), 261–70. Aix-en-Provence: Narration editions.

- Gayraud, R.-P., S. Björnesjö, and S. Denoix. 1986. “Istabl ‘Antar (Fostat) 1985: Rapport de Fouilles.” Annales Islamologiques 22: 1–26.

- Gayraud, R.-P., S. Björnesjö, S. Denoix, and M. Tuchscherer. 1987. “Istabl ‘Antar (Fostat) 1986: Rapport de Fouilles.” Annales Islamologiques 23: 55–71.

- Gayraud, R.-P., S. Björnesjö, P. Gallo, J.-M. Mouton, and F. Paris. 1995. “Istabl ‘Antar (Fostat) 1994: Rapport de Fouilles.” Annales Islamologiques 29: 1–24.

- Gayraud, R.-P., S. Björnesjö, V. Miguet, J.-M. Muller-Woulkoff, V. Roche, and M. Saillard. 1991. “Istabl ‘Antar (Fostat), 1987-1989: Rapport de Fouilles.” Annales Islamologiques 25: 57–87.

- Gayraud, R.-P., S. Björnesjö, and P. Speiser. 1994. “Istabl ‘Antar (Fostat) 1992: Rapport de Fouilles.” Annales Islamologiques 28: 1–27.

- Gayraud, R.-P., and X. Peixoto. 1993. “Istabl ‘Antar (Fostat) 1990: Rapport de Fouilles.” Annales Islamologiques 27: 225–32.

- Gayraud, R.-P., and J.-C. Treglia. 2012. “Céramiques D’un Niveau D’occupation D’époque Mamelouke à Istabl Antar/Fostat (Le Caire, Egypte).” In Atti del IX Congresso Internazionale Sulla Ceramica Medievale nel Mediterraneo, edited by S. Gelichi, 297–302. All’Insegna del Giglio: Firenze.

- Gayraud, R.-P., and L. Vallauri. 2017. Fustat II: Fouilles D’Isṭabl ‘Antar; Céramiques D’ensembles des IXe et Xe Siècles. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Ghaly, H. 1992. “Pottery Workshops of Saint-Jeremia (Saqqara).” Cahiers de la céramique Égyptienne 3: 160–71.

- Goitein, S. D. 1967–1988. A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Goitein, S. D. 1999. A Mediterranean Society: An Abridgement in One Volume, rev./ed. J. Lassner. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Golvin, L., J. Thiriot, and M. Zakariya. 1982. Les Potiers Actuels de Fustat. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

- Grohmann, A. 1952. Arabic Papyri in the Egyptian Library, vol. 4 (Administrative Texts). Cairo: Egyptian Library Press.

- Gustafsson, J., and K. Mostafa. 2016. Kolkata’s Age Old Tradition of ‘Bhar’ Clay Cups of Tea.” Al-Jazeera Gallery. Accessed 2 Dec 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2016/10/26/kolkatas-age-old-tradition-of-bhar-clay-cups-of-tea.

- Harrison, M. J. 2014. “The Houses of Fusṭāṭ: Beyond Importation and Influence.” In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 9–13 June 2014, Basel, vol. 2, edited by R. A. Stucky, O. Kaelin, H.-P. Mathys, S. Bickel, B. Jacobs, J.-M. Le Tensorer, and D. Genequand, 383–96. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Harrison, M. J. 2015. Fustat Reconsidered: Urban Housing and Domestic Life in a Medieval Islamic City. Ph.D. diss., University of Southampton. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/396526/.