ABSTRACT

The earthquakes on 6 February 2023 in southeastern Türkiye and northern Syria were a disaster on a massive scale. Tens of thousands of lives were lost, and the destruction is still being assessed and grappled with today, over a year later. As one of the archaeological projects in the disaster zone, we at the Tell Atchana Excavations, many of us survivors, have had to consider ways in which we can move forward while incorporating and honoring the past—both the past that we study and our own experiences. We have embraced the engagement with the past that characterizes archaeology as a discipline and have come together to support one another and our communities through a large-scale project of preserving the exposed mudbrick monuments at Tell Atchana. This photo essay journeys through the difficulties we faced and the opportunities we found in them and celebrates the healing potential of archaeology in the face of disaster.

Introduction

On 6 February 2023, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake hit 11 cities in southeastern Türkiye and northern Syria. Nine hours later, this was followed by another earthquake of 7.6 magnitude, an extremely unusual natural phenomenon along the East Anatolian Fault (Meng et al. Citation2024; Ren et al. Citation2024). A third, 6.3 magnitude, Antakya-based earthquake, 14 days after that, was followed by 40,000 aftershocks (Altunsu et al. Citation2024; Över, Demirci, and Özden Citation2023). The aftershocks that continue to this day no longer pose a threat but are horrifying to experience for people who went through the 6 February earthquakes, leading to major psychological trauma. According to official records, over 50,000 people in Türkiye and 3000 people in Syria died, with hundreds of thousands more injured. From historic buildings to modern apartments, nothing survived. In the cities impacted by the earthquakes, over half a million buildings were heavily damaged, and now, many are in the process of being demolished (see Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı Strateji ve Bütçe Başkanlığı Citation2023).

In Hatay, the most dramatic destruction was centered in Antakya, Samandağ, Kırıkhan, and Iskenderun. The morning of the earthquake in a city shattered into pieces, with thousands of dead bodies and severely injured people, was simply chaos; there was no electricity, the roads were closed due to deep cracks or collapsed buildings, and people had no chance but to wait for over five days to be rescued in an unsafe environment (, ).

Figure 1. An image taken by team member Gökhan Tektaş along the Orontes River in the Antakya city center the day after the earthquake.

Figure 2. Image of collapsed buildings taken by team member Gökhan Tektaş during his participation in rescue operations in Antakya.

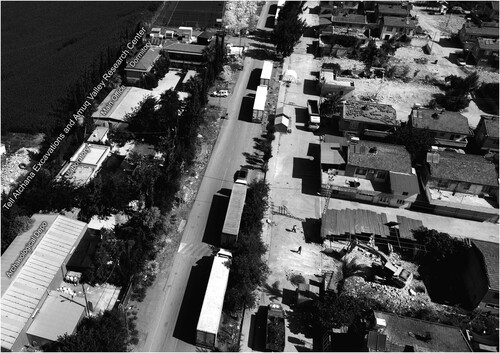

In these circumstances, we were privileged to have a fully functional archaeological research center established under the umbrella of Tell Atchana Excavations just 20 km outside the city center. The compound was not damaged and played a crucial role during this natural disaster, turning into an operational center for humanitarian support during the first months and demonstrating the value that research centers (or dig houses), often located outside urban areas, can have in such periods of crisis—a responsibility and opportunity that all archaeological projects, especially those with well-established facilities, should be mindful of and prepared for (, ). While the team members based in Antakya were struggling to make sense of the scale of the disaster, Hélène Maloigne launched a crowdfunding campaign. The money raised allowed us to acquire temporary living containers, tents, food, and medical supplies for the local communities. Since much of the humanitarian and official support prioritized people living in the city centers, we decided to focus our efforts on helping our communities: the villages near where our project is based and whose people we have been interacting and working with for more than 20 years, as well as providing stipends to our students to enable them to continue their studies.

Figure 3. Tell Atchana Excavations and the Amuq Valley Research Center, located in Tayfursökmen village. As seen in the image, many of the houses in the village were reported to have been heavily damaged and are in the process of being demolished.

Figure 4. The first night after the earthquake at the research center, hosting up to 40 people, including authors Murat Akar, Müge Bulu, Gökhan Tektaş, and Baran Kerim Ecer.

In this photo essay, we will not focus on the destruction. Instead, we want to celebrate the way our team and our communities—local and international—have come together as a family to support each other, strengthening existing and building new friendships (Hintz Citation2024), and to highlight the physical act of restoration and preservation at the site, which we have found has supported our own processes of grieving and coming to terms with personal loss. Our goal is ultimately to include the wider community in annual events celebrating traditional building methods and the preservation of intangible and tangible heritage. We are now in the process of organizing field schools, particularly for elementary and high school level students, for the 2024 field season to create further engagement opportunities, as well as a heritage day that will be open to the public. Such practices are already well established in other communities, for instance the yearly plastering festival at the famous mosque of Djenné, where collective community engagement is the key to preserving the monument (Marchand Citation2013). The major question is, then, how can we (re-)create such a model in preserving a heritage site that is 4000 years old? In our case, the earthquakes have presented an opportunity to both raise earthen heritage awareness, especially in a region where thousands have suffered under collapsed concrete buildings, and to help facilitate the healing process by involving the local community in physically embracing and rebuilding their cultural heritage. While this is grounded in established research about the usefulness of archaeology in dealing with grief and loss (Croucher et al. Citation2020), our experiences are not easily translated into the often “neutralized” or seemingly objective language of academia, and we appreciate the opportunity the JFA has created with these photo essays for more informal ways of communicating research, as we instead draw here on the personal, anecdotal experiences of this tragedy of both ourselves and our communities in Hatay. Most of our team members, from undergraduate students to project leaders and non-archaeological staff, are survivors of the earthquakes. Our joint responsibility was therefore to provide continued financial support and—through fieldwork—to provide a healthy and safe environment for our students, who were traumatized by the loss of their core family members, relatives, friends, houses, and their city. Archaeology, for us, has been rehabilitation and has created deeper bonds with the site, within the team, and with our local communities.

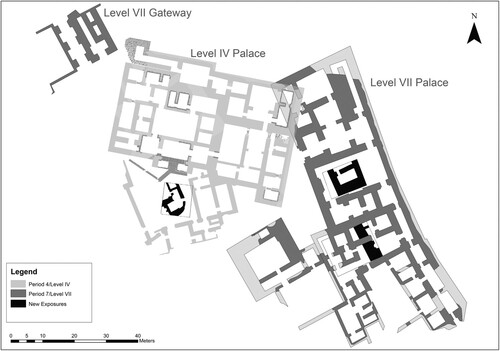

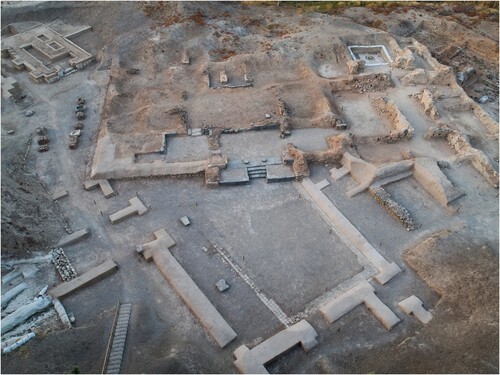

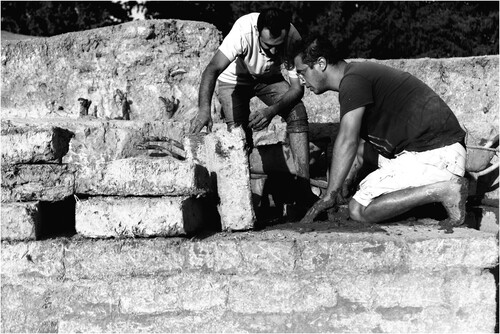

Tell Atchana, a Bronze Age regional capital, and the neighboring site of Tell Tayinat are located along a fault line, and in fact, the major damage that occurred along the main road is roughly 1 km from each of these sites. No major damage occurred at either Tell Atchana or Tell Tayinat, except for a few sections collapsing in the new excavation areas, whereas the large-scale exposures excavated by Charles Leonard Woolley during the 1930s and 1940s at Tell Atchana were severely damaged (Woolley Citation1955; ). Unfortunately, exposed over 80 years ago and already in fragile condition, the burnt mudbrick walls of the 18th century b.c. Middle Bronze Age (MBA, Level VII) palace walls partially collapsed, and stone orthostats were dislocated from their original location and shattered into pieces (, ). The royal hypogeum located on the southern section of the monument was badly damaged. Adjacent to that, the Late Bronze Age (LBA, Level IV) palace, built in the 15th century b.c. by King Idrimi, a prototype of the bit hilani-type palace with its stepped and columned entrance, suffered similar damage ().

Figure 6. The collapsed eastern wall of the MBA palace (Level VII). Usable bricks are being sorted out by Mehmet Fatih Sert.

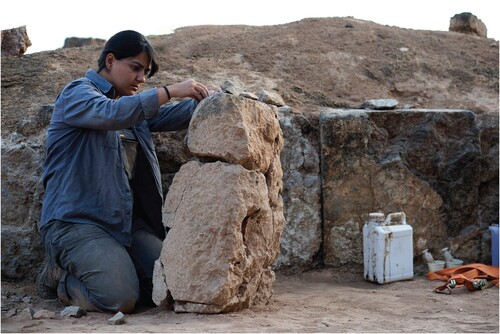

Figure 7. Restoration of the broken limestone orthostats of the MBA palace by conservator Hatice Nur Aydın (Level VII).

But the severity of the earthquakes was not the only factor in the scale of destruction at Tell Atchana. Woolley’s excavations on behalf of the British Museum (1936–1939 and 1946–1949) exposed roughly one-third of the mound, including the remains of the so-called Royal Precinct with palace complexes and associated structures. In modern archaeological standards, this task could only be accomplished over centuries of excavations. This is the irony modern archaeologists face: on the one hand, without these previous excavations that have given us thousands of objects and vast areas of standing remains to work with, our own work at the site and understanding of the ancient world would look very different. On the other hand, the work of those previous scholars, who (in keeping with the practices of the time) did not consider questions of sustainable heritage management and site preservation, can leave us with a very challenging legacy. Re-evaluating and refining Woolley’s results has dominated our research agenda at Tell Atchana for many years upon initially returning to the site over half a century after Woolley closed his excavations and walked away (Yener Citation2010; Yener, Akar, and Horowitz Citation2019). Over the last decade, we have increasingly turned our focus to questions of historical legacy, preservation, sustainability, and public engagement.

Preserving and Presenting the Past

In 2012, we first began transforming the site (which has always been publicly accessible) into an archaeological park. As has been explored elsewhere (Arauz Citation2014), we have worked closely with the community in developing panels, signage, and a viewing platform to facilitate public engagement. As this program had to run alongside our continued excavations in the Royal Precinct and previously unexplored parts of the site, our progress with the preservation and interpretation of the site was necessarily slow, and we were facing a monumental task. Woolley’s excavation area has not fared well over the years. All the exposed monuments are decayed and infested with an extremely deep-rooted wild plant called Syrian mesquite (Prosobis Farcta; Pasiecznik, Harris, and Smith Citation2004). To a visitor’s eye, it is difficult to comprehend what all the bumps (which were originally mudbrick walls) in the Woolley excavation area mean and what the Bronze Age city might have looked like ().

Figure 9. Photo taken in the summer of 2020, showing the condition of the LBA palace prior to the heritage preservation program.

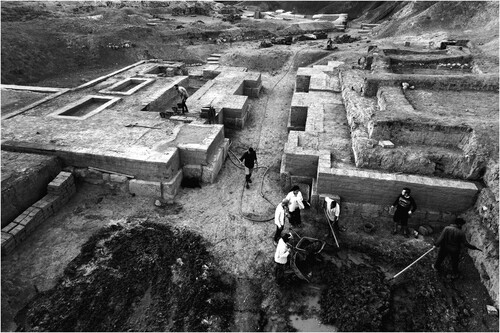

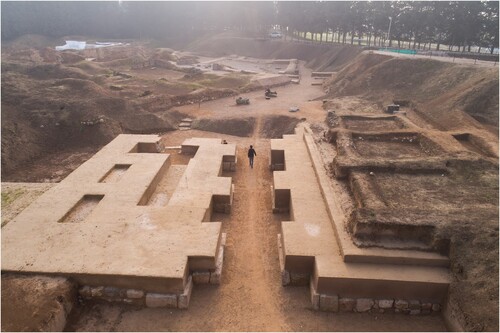

The preservation and presentation of mudbrick monuments and architecture on a large scale is a tremendous undertaking, as these monuments require yearly treatment and collective effort to prevent decay and collapse (Bizzarri et al. Citation2020; Gelin Citation2010). The rapid decomposition of the site is partly due to the nature of building materials in the ancient Near East. Mudbrick architecture is fragile, and once it is exposed, there is no way to provide long-term protection unless it is isolated from environmental stress. Though Woolley was not alone in giving little thought to the afterlife of archaeological excavations and sustainable heritage preservation, the site was abandoned and neglected after the termination of the excavations in 1949. Nature reclaimed the site, with teeming wildlife and deep-rooted plants that have made the architectural remains their home. Thousands of tell sites like Tell Atchana shape the archaeological landscapes of Anatolia, the Near East, and the Levant, and they decompose and deteriorate once deserted by archaeologists. The long-lasting effects of (scientific) colonization (going back to the Ottoman occupation of these regions), civil war, and invasion by European and American forces have exposed the fragility of the cultural heritage of the region and demonstrated the importance of sustainable management and community engagement (https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/projects/girsu-project). Over the last years, the economic impact of the civil war in Syria, the worldwide pandemic, and inflation rates in Türkiye have further affected the project at Tell Atchana. We have come to accept that little local support is available but have made the best of Murat Akar’s presence in Hatay, due to his position at Hatay Mustafa Kemal University, which allowed us to extend our field seasons from May–November. Since 2019, we have been working on removing the collapsed mudbrick detritus of the walls that, to a certain extent, preserved what is left underneath. Once this was accomplished, the general layout of the building plans once again became understandable, and a sense of space was created (). After the recent earthquakes, establishing a response plan for the site and bringing forward issues of resilient heritage became a necessity (, ). Below, we focus on one example of our pre- and post-earthquake preservation work at the site and the excavation compound to illustrate the work so far and the challenges that await us.

Figure 10. Photo taken in the summer of 2022 after the initial cleaning operations and the removal of mudbrick detritus from the LBA palace walls.

Mudbrick Capping of the Middle Bronze Age City Gate

The MBA city gate excavated by Woolley is a typical example of such structures that are attested over a long period in the region (Burke Citation2008; ). Like so many of the monuments excavated under his leadership, it was heavily decayed and pockmarked by the mesquite plant. It took weeks just to remove the plants to see what remained underneath. Once the entire surface was cleaned, we also realized that this was one of the locations of Woolley’s dump along the slopes of the tell, which had significantly altered the view of the site. All the walls had collapsed, and removal of the mudbrick detritus took a full season of fieldwork. Once this was achieved, it was clear that the monument required further treatment (, ).

Figure 14. Photo showing the condition of the eastern guard chamber of the MBA gate complex during the first days of the cleaning operation performed in 2021 (Photo: Ayça Deniz Çınar).

Thus, we began a mudbrick capping project. We already knew that such a project requires building strong walls around the decayed monuments, but before the earthquake, we only sealed the walls with a single row of mudbricks 20 × 20 × 40 cm in size. The idea was to improve the visual presentation of the site for visitors with minimal effort, but unfortunately this project was interrupted in the winter of 2023 by the earthquake, which led to the collapse of the capping walls.

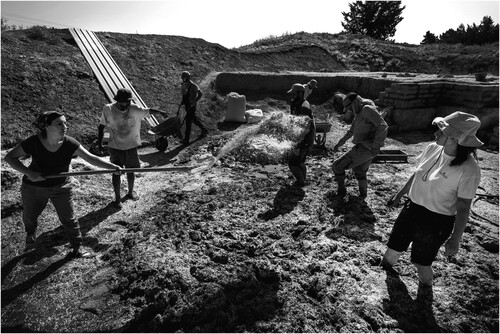

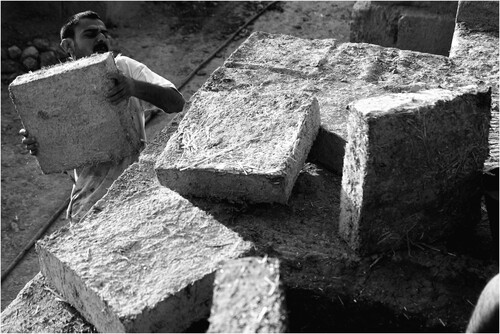

This work has been an important learning process for us, mainly starting with the choice of raw material, which we did not really think much about at the beginning, using soil that was brought from elsewhere in the valley with a high clay content. As part of this research, Onur Hasan Kırman acquired mudbrick samples from all buildings from various levels, and those samples were subjected to ICP-MS analysis (Kırman Citation2022). Macroscopically, the major distinction was the presence of a silty and sandy matrix in the MBA mudbricks and higher clay content in the LBA mudbricks. This, in tandem with our sediment coring project (Avşar, Akar, and Pearson Citation2019), proved that the MBA builders of Alalakh were using the flood deposits of the Orontes River throughout the MBA, and with the shift of the riverbed through time, mudbricks with higher clay content were noted for the later LBA II contexts. So, in the summer of 2023, we decided to proceed using soil from the site, converting Woolley’s and our own excavation dump into mudbricks. But first, it had to be excavated and sifted. The MBA silty matrix turned out to be the best choice to produce mudbricks, not only in terms of the quality of the bricks themselves but also in terms of matching materials and preserving historical accuracy. As temper, we used straw bought immediately after the harvest season directly from the field (). Water management was a major issue, as we were using 3000 liters of water daily from a tank equipped with a very long hose and a water pump. 200 kg of straw were used to produce a mud mixture of 5 tons, which was left to rest for a day. Every evening, as a team, we went to the site and used our bare feet to prepare the mudbrick mixture for the following day (). Although an important bodily engagement with the preservation process, the team became exhausted working over 12 hours a day. The physical work was soon replaced with a mini hoeing machine, thanks to the suggestion of the director of the Kültepe Excavations, Fikri Kulakoğlu, making the process much easier on tired team members ().

Approximately 4500 mudbricks were produced and used at the site over the course of the 2023 field season (). The change of brick size to the Bronze Age standards observed at the site of 40 × 40 × 20 cm, in order to remain as close to the original building methods as possible, required tremendous amounts of raw materials, as well as physical endurance, as each brick weighs up to 25 kg when dried. Our bricks were shaped in custom-made frames, allowing us to produce up to 200 bricks per day, which were dried in the sun over several days, turning them regularly to expose all sides to the air ().

Figure 19. Gamze Alkan, Defne Güler Bilgili, and Zeynep Türker making mudbricks as part of their daily routine.

Figure 20. Mudbricks produced in one day. On the left, Arman Alp is stacking bricks vertically to let them dry.

As has been the custom in archaeology in the Middle East for over 150 years, we have been relying on employing local labor (Mickell Citation2021), but as of this year, it has become challenging for us to retain people who in some cases are long-term colleagues. Now that the entire city is a construction zone following the destruction of the earthquakes, everyone in the region prefers to work on construction projects, and the daily wage is far above what we can afford. This has, once again, proven challenging for us as we, the team leadership and the students, have taken up most of the heavy manual work ourselves ().

Figure 26. Büşra Hekimoğlu and a small collection of the deep roots of Syrian mesquite (Prosobis Farcta) cleaned from around the gate complex.

The capping of walls with the new mudbricks was followed by mud plastering that will protect the monument from heavy rainfall in the winter (). shows a view of the gate from outside with the plastering work completed. shows the view from inside the city, illustrating the relationship between landscape and city, looking down the hills, and the old riverbed of the Orontes.

While this project is a unique opportunity and experience for us as archaeologists, which has created very strong bonds throughout the team, we do recognize the challenges going forward: our students learn vital skills of heritage preservation, but they have also been coming to Tell Atchana from around the world to learn from our cutting-edge excavation and finds processing approaches for over 20 years. Limited funding (local, national, and international) is forcing us to limit both aspects of our work, which we consider interconnected and inseparable.

Work on the Archaeological Collections in the Storage Facility

At Tell Atchana, we are proud to follow a no discard policy and have a very well-organized storage facility with a shelving inventory and labeling system, but sadly, we were not prepared for the earthquake—objects were displaced from shelves, and stacks of crates collapsed (). The cleaning and reorganization of the storage space over the summer of 2023 was an undertaking of its own, as it necessitated cleaning up, sorting through, cataloging, and reorganizing hundreds of objects and dozens upon dozens of crates and boxes full of the finds from over 20 years of excavation and survey. Even here, though, there was opportunity, and in the spirit of looking forward, we used this project as a chance to complete an audit of the material, to reorganize the depot space, and to lay the groundwork for our next excavation results monograph.

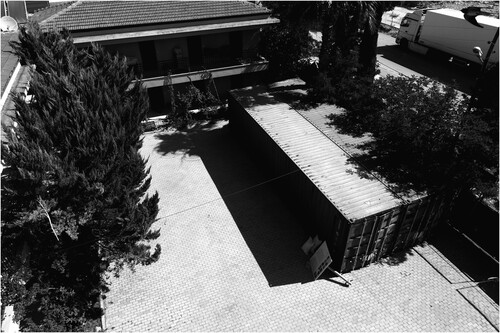

In the wake of this work, we have adopted further new precautions that include the reinforcement of the structure and the installation of netting to prevent objects falling from their shelves (). We are now also housing the archaeological collection from Kinet Höyük, as the Hatay Archaeological Museum will be undergoing repairs and reinforcements in the coming years. This had already been planned with Kinet Höyük’s excavation director, Marie-Henriette Gates, as a step towards consolidating and making accessible Hatay-related archaeological collections, but the earthquakes have required adjustments to these plans and timelines. Our storage facility is also home to the finds from Toprakhisar Höyük, our sister project which we have been conducting in the Altınözü highlands since 2016 (Akar and Kara Citation2020), and we have also made space for our colleagues from Tell Tayinat Excavations, whose excavation house in the city center was heavily damaged. Their work in the summer of 2023 was dedicated to the re-location and re-organization of their collections, currently stored in two shipping containers located in the garden of our research center ().

Figure 31. The archaeological collections’ depot was reinforced by supporting metal bars, creating barriers for each corridor, and the collection has been re-organized.

Figure 32. View of the courtyard of the research center with shipping containers storing the Tell Tayinat Excavations archaeological collections. As the region begins the process of recovery from the disaster, shipping containers like these can be seen everywhere, housing people, businesses, and even, as here, artifacts.

Conclusion

Tell Atchana continues to offer not only opportunities for groundbreaking and cutting-edge archaeological research, it also gives us the chance to engage with and reflect on the history of archaeology and the legacy that we have inherited from previous scholars. It is the perfect example to highlight concerns about the background of our discipline, when digging up the past was often performed without thinking of the future. We build upon what came before in many ways—past research that informs our own, as well as the decayed earthen remains from Woolley’s excavations that were so long neglected and must now be physically preserved—while looking to the present. As archaeologists, we firmly believe in the value of looking at the past to inform the future, and in the wake of the disaster of the 6 February 2023 earthquakes, we, as a team, have found engagement with the past and with archaeology to be a healing way to move forward.

Acknowledgements

Archaeology is nothing but teamwork. We are privileged to have a dedicated group of people working at Tell Atchana, Alalakh. We also would like to give our sincere thanks to the institutional and individual donors who have supported our heritage efforts in these tough times. We wholeheartedly thank, especially, all the members of our 2023 team: Hatice Nur Aydın, Gamze Alkan, Ebru Gizem Ayten, Zeynep Türker, Defne Güler Bilgili, Arman Alp, Mehmet Çalgıcı, Büşra Hekimoğlu, Hikmet Eslikızı, and Mustafa Bilgili, as well as the Varışlı village community members, including Abdullah Öz, Gazi Yılmaz, Mehmet Fatih Sert, Hüseyin Yener, Ahmet Kılıç, Yusuf Sertel, and Hasan Biçer. We also would like to give our sincerest thanks to Berati Sönmez, Hatice Sönmez, Ender Sönmez, and Hatice Sönmez and their family, with whom we’ve passed through these difficult times.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Murat Akar

Murat Akar (Ph.D. 2012, Università degli Studi di Firenze) is an Associate Professor of Anatolian and Near Eastern Archaeology at Hatay Mustafa Kemal University, and he is the Director of Excavations at Tell Atchana, Alalakh. His research areas include mudbrick architecture, memory, and landscape studies. His current research addresses the role of climate in the longue durée for understanding the continuously shifting population dynamics and cross-cultural encounters in eastern Mediterranean contexts.

Onur Hasan Kırman

Onur Hasan Kırman (M.A. 2020, Hatay Mustafa Kemal University) is the Field Director of excavations at Tell Atchana, Alalakh. His research areas include mudbrick architecture, geoarchaeology, and agency in the Anatolian and Near Eastern Bronze Age.

Müge Bulu

Müge Bulu (Ph.D. 2021, Koç University) is an Assistant Professor of Protohistory and Near Eastern Archaeology at Ankara University and the Assistant Director of Ceramic Studies at Tell Atchana, Alalakh Excavations. Her research interests include the reconstruction of pottery production technologies, the use of space through contextual analysis, and ancient foodways in the Near Eastern Bronze Age.

Hélène Maloigne

Hélène Maloigne (Ph.D. 2020, University College London) is Co-Editor for the Bulletin of the History of Archaeology and Assistant Director of Artefacts and Collections at Tell Atchana, Alalakh Excavations (Turkey). They are Lecturer in History at the University of Greenwich (London), with a research focus on the history of archaeology and its popular reception.

Tara Ingman

Tara Ingman (Ph.D. 2020, Koç University) is a senior editorial assistant at the Journal of Field Archaeology, a post-doctoral fellow at Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations (ANAMED), and the Assistant Director of Publications at Tell Atchana, Alalakh Excavations. Her research interests include funerary archaeology, burial practices, isotopic studies, and the Near Eastern Bronze Age.

Gökhan Tektaş

Gökhan Tektaş (B.A. 2020, Hatay Mustafa Kemal University) is a senior member of the excavations at Tell Atchana. His research areas include center and periphery dynamics in the Bronze Age through the study of metals.

Baran Kerim Ecer

Baran Kerim Ecer (B.A. 2020, Hatay Mustafa Kemal University) is a senior member of the excavations at Tell Atchana conducting fieldwork on mudbrick preservation and presentation.

References

- Akar, M., and D. Kara. 2020. “The Formation of Collective, Political and Cultural Memory in the Middle Bronze Age: Foundation and Termination Rituals at Toprakhisar Höyük.” Anatolian Studies 70: 77–103.

- Altunsu, E., O. Güneş, S. Öztürk, S. Sorosh, A. Sarı, and S. T. Beeson. 2024. “Investigating the Structural Damage in Hatay Province After Kahramanmaraş-Türkiye Earthquake Sequences.” Engineering Failure Analysis 157 (2024/03/01/2024): 107857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107857.

- Arauz, E. C. 2014. “Aççana Höyük, Alalah’ta Arkeo-Park Projesi ve Toplumsal Arkeoloji çalışmaları = The Arkeo-Park Project and Community Engagement at Tell Atchana, Alalakh.” In Unutulmuş Krallık: Antik Alalah’ta Arkeoloji ve Fotoğraf = The Forgotten Kingdom: Archaeology and Photography at Ancient Alalakh, edited by M. Akar, and H. Maloigne, 98–113. Istanbul: Koç Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Avşar, U., M. Akar, and C. Pearson. 2019. “Geoarchaeological Investigations in the Amuq Valley of Hatay: Sediment Coring Project in the Environs of Tell Atchana.” In The Proceedings and Abstracts Book, 72nd Geological Congress of Turkey with International Participation, edited by H. Sözbilir, Ç Özkaymak, B. Uzel, Ö Sümer, M. Softa, Ç Tepe, and S. Eski, 798–802. Ankara: Jeoloji Mühendisleri Odası Yayınları.

- Bizzarri, S., M. Degli Esposti, C. Careccia, T. de Gennaro, E. Tangheroni, and N. Avanzini. 2020. “The Use of Traditional Mud-Based Masonry in the Restoration of the Iron Age Site of Salūt (Oman). A Way Towards Mutual Preservation.” In 2020 International Conference on Vernacular Architecture in World Heritage Sites. Risks and New Technologies, HERITAGE 2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra), València, Spain, Sep 2020, edited by C. Mileto, F. Vegas, V. Cristini, and L. García, 1081–1088. Gottingen: Copernicus GmbH.

- Burke, A. 2008. “Walled up to Heaven”: The Evolution of Middle Bronze Age Fortification Strategies in the Levant. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Croucher, K., L. Büster, J. Dayes, L. Green, J. Raynsford, L. Comerford Boyes, and C. Faull. 2020. “Archaeology and Contemporary Death: Using the Past to Provoke, Challenge and Engage.” PLOS ONE 15 (12): e0244058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244058.

- Gelin, M. 2010. “Treatment, Conservation and Restoration of Mudbrick Structures.” In Hegra 1-Report on the First Excavation Season at Madâ'in Sâlih-2008 Saudi Arabia, edited by N. Laïla, a.-T. Daifallah, and V. François, 28–46. Riyadh: Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities.

- Hintz, L. 2024. “Academic Solidarity in the Wake of Disaster: Blueprint for an Online Writing Support Group.” PS: Political Science & Politics 16 (February): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096524000015.

- Kırman, O. H. 2022. “Aççana ve Toprakhisar Höyükleri (Hatay) Kerpiçlerinin Jeokimyasal Analizleri Kapsamında M.Ö. 3. Binyıldan M.Ö. 1. Binyıla İklimsel ve Tercihsel Değişimlerin Olası İzleri.” (M.A. Thesis). Hatay Mustafa Kemal University.

- Marchand, T. H. J. 2013. “The Djenné Mosque. World Heritage and Social Renewal in a West African Town.” In Religious Architecture, edited by V. Oskar, 117–148. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Meng, J., T. Kusky, W. D. Mooney, E. Bozkurt, M. N. Bodur, and L. Wang. 2024. “Surface Deformations of the 6 February 2023 Earthquake Sequence, Eastern Türkiye.” Science 383 (6680): 298–305. 10.1126science.adj3770.

- Mickell, A. 2021. Why Those Who Shovel Are Silent: A History of Local Archaeological Knowledge and Labor. Denver: University Press of Colorado.

- Över, S., A. Demirci, and S. Özden. 2023. “Tectonic Implications of the February 2023 Earthquakes (Mw7.7, 7.6 and 6.3) in South-Eastern Türkiye.” Tectonophysics 866 (11/05/2023): 230058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2023.230058.

- Pasiecznik, N., P. Harris, and S. Smith. 2004. Identifying Tropical Prosopis Species: A Field Guide. HDRA: Coventry.

- Ren, C., Z. Wang, T. Taymaz, N. Hu, H. Luo, Z. Zhao, H. Yue, X. Song, Z. Shen, H. Xu, J. Geng, W. Zhang, T. Wang, Z. Ge, T. S. Irmak, C. Erman, Y. Zhou, Z. Li, H. Xu, B. Cao, and H. Ding. 2024. “Supershear Triggering and Cascading Fault Ruptures of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye, Earthquake Doublet.” Science 383 (6680): 305–311. 10.1126science.adi1519.

- Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı Strateji ve Bütçe Başkanlığı. 2023. “Kahramanmaraş ve Hatay Depremleri Raporu.” Accessed 22 February 2024. https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2023-Kahramanmaras-ve-Hatay-Depremleri-Raporu.pdf.

- Woolley, C. L. 1955. Alalakh: An Account of the Excavations at Tell Atchana in the Hatay, 1937-1949. Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London 18. London: Oxford University Press.

- Yener, K. A.2010. Tell Atchana, Ancient Alalakh. Volume I: The 2003–2004 Excavation Seasons. Istanbul: Koç University Press.

- Yener, K. A., M. Akar, and M. T. Horowitz2019. Tell Atchana, Alalakh Volume 2: The Late Bronze II City. 2006-2010 Excavation Seasons. Istanbul: Koç University Press.