Abstract

The transition from centralized energy systems based on fossil fuels to renewable-based systems is a macro-level societal shift necessitated by climate change. This review of recent environmental education (EE) research identifies gaps and opportunities for promoting environmental action in this new context. We found that environmental educators and researchers are currently focused on researching and promoting energy conservation behavior with an emphasis on children and youth. We also found an emerging research focus on energy transitions at the regional and national levels. We recommend that environmental educators and researchers adopt a vision and strategy for climate change and energy education that more explicitly addresses the role of collective action, multiactor networks, and sociotechnical innovation in shaping energy transition processes.

The need for an urgent, radical transformation in energy systems throughout the world in the next two decades was highlighted in the most recent special report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, Citation2018). Burning fossil fuels for energy is the human activity contributing most to climate change (IPCC, Citation2018, Citation2014), and the urgent need to reduce the risks of climate change has motivated a sociotechnical transition away from fossil fuels toward more renewable-based energy systems (Friedman, Citation2008; Princen, Manno, & Martin, Citation2015). The renewable energy transition represents a transformative societal shift from a society based on fierce competition for a scarce resource (fossil fuels) to a society based on abundant and perpetual sources of energy (renewables) (Burke & Stephens, Citation2017). Beyond mitigating climate change, justifications for an energy transition include reducing the public health risks of fossil fuels, creating local and regional jobs, and reducing the political and economic power that is centralized in large fossil fuel companies (Burke & Stephens, Citation2018). The complex social, technological, and ecological changes involved in this global transition provide a potentially invaluable lens for environmental educators and researchers to advance EE goals during this time of rapid climate disruption and energy system change.

Existing frameworks for EE offer insufficient guidelines for how to prepare students for the rapidly changing realities of climate change and the renewable energy transition. As several scholars have noted (Jensen, Citation2004; Palmer, Citation1998; Sterling, Citation2001), EE does not have a well-developed approach to systemic environmental problems that are connected to “pervasive technological and social developments” (Jensen, Citation2004, p. 405). The conceptual and methodological foundations of EE were developed in the 1970s and 1980s when it was assumed that energy and environmental problems could be adequately addressed through resource conservation and incremental changes to technology and human behavior (Palmer, Citation1998; Sauvé, Citation2005). Climate change is a new and different kind of problem. It is a systemic problem of such scale and complexity that fundamental and transformative changes to society’s energy systems are required (Geels, Citation2010; IPCC, Citation2018). This implies fundamental and transformative changes to EE as well (Sterling, Citation2001).

In this article, we use a transitions framework to critically examine the recent EE literature on climate change and energy education with specific regard to its understanding of action and change. Our goal is to advance a new line of thinking and research that reframes climate change as predominantly an energy systems issue and identifies gaps and opportunities for promoting environmental action in this new context. To this end, our framework builds on EE’s tradition of promoting action at the individual level by adding insights from the sustainability transitions literature regarding actions to promote systemic change and energy system transformation.

The article addresses the following questions:

What does the EE research literature reveal about how EE researchers are currently conceptualizing the relationship between climate change and energy system change?

What actions are currently being researched and promoted in this context? Who are the primary actors and agents of change?

How can this information inform EE’s evolving strategy on climate change and energy education?

A transitions perspective on environmental education and action

The field of sustainability transitions embraces a sociotechnical systems perspective that integrates research on technological innovation, social sciences, and policy. A transitions perspective emphasizes systems level change that results from the interaction and coordination of actions and innovations across multiple levels of scale (Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016; Fischer-Kowalski & Rotmans, Citation2009). From a transitions perspective, sustainability does not emerge as a “passive consequence of consuming less” (Tainter, Citation2011, p. 93) but through the driving force of multiple actors that purposefully shape transitions around a shared long-term vision of the future (Farla, Markard, Raven, & Coenen, Citation2012, p. 992). The accelerating renewable energy transition may, in fact, result in some places and some people using more energy than before but energy that could come from a heterogeneous mix of renewable sources (Tainter, Citation2011). Transition scholars emphasize this kind of complexity and the interconnections of key drivers of change within sociotechnical systems (Fischer-Kowalski & Rotmans, Citation2009; Geels & Schot, Citation2007).

Whereas the field of sustainability transitions seeks to conceptualize, observe, and influence change at the level of systems, the field of EE has sought for much of its history to conceptualize, observe, and influence change at the level of individual persons (Courtenay-Hall & Rogers, Citation2002). Relatedly, whereas transitions researchers emphasize the emergent and public/political nature of action and change (Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016; Jacobsson & Lauber, Citation2006; Meadowcroft, Citation2011), EE researchers have often emphasized relatively benign actions in the private sphere over public and collective ones (Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Courtenay-Hall & Rogers, Citation2002; Jensen, Citation2002). EE scholars who have conducted energy-related research have typically focused on energy conservation and changing energy end-use patterns (Dresner, Citation1990; Honnold & Nelson, Citation1978; McLeod, Glynn, & Griffin, Citation1987) rather than energy systems and larger societal transitions.

To develop a multilevel framework for reviewing EE research related to these issues, we have conceptualized EE’s primary objective as promoting environmental action in the context of environmental problems (Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Jensen, Citation2004). We have interpreted EE’s history as an evolving attempt to refine the concept of environmental action in the context of increasingly complex and systemic problems (Sauvé, Citation2005). Here we refine the concept further to fit the current “historic and macro-cultural context” (Sauvé, Citation2005, p. 12) in which the climate is changing quickly and energy systems are rapidly transforming. We assume that environmental action in this context includes actions that benefit the environment indirectly by advancing the transformation of energy systems, from active participation in social movements to private transitions in everyday practices (Hermwille, Citation2016; Jacobsson & Lauber, Citation2006; Shove & Walker, Citation2010).

Based on Jensen (Citation2002), we define environmental action as action that contributes to solving an environmental problem and is decided upon by the actors themselves (p. 326). By contrast, environmental behavior connotes individual actors and pre-determined outcomes and is too narrowly fixed—both conceptually and methodologically—to capture the multiple actions and actors that emerge within sustainability transitions (Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016; Farla et al., Citation2012; Grin, Rotmans, & Schot, Citation2011). In this article we consider environmental behavior to mean private-sphere environmental action at the level of individual persons (Stern, Citation2000).

Our framework (see ) distinguishes among (1) public/private; (2) individual/collective; and (3) direct/indirect environmental actions (Courtenay-Hall & Rogers, Citation2002; Jensen, Citation2004; Stern, Citation2000). We define actor as “a person or organization, or a collective of persons and organizations, which is able to act” (Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016, p. 634). Potential actors in sustainability transitions (see ) include individual persons in their various public and private roles and a range of organizations in the public and private sectors (Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016). Collective action is action taken in common by a group of individual actors—whether persons or organizations—in pursuit of a perceived shared interest (Meinzen-Dick, DiGregorio, & McCarthy, Citation2004, p. 200). Some forms of collective action involve small groups of actors at the community level whereas others involve multiactor networks at the regional, national, or global levels.

Table 1. Types of environmental action (adapted from Jensen, Citation2002, p. 327; Jensen, Citation2004, p. 413; Stern, Citation2000, p. 409–410).

Table 2. Examples of individual and organizational actors, by sector, in sustainability transitions (adapted from Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016).

Collective action and innovation are key drivers of sustainability transitions. In this article we use the term transition experiments (Fischer-Kowalski & Rotmans, Citation2009) to refer to specific collective innovations such as community solar projects or energy cooperatives that emerge within the context of local and regional energy transitions. We use the term transition studies to refer to research on these innovations. Advocacy coalitions are when groups of individual actors come together to influence policy decisions through the advocacy use of knowledge. The efforts of advocacy coalitions to influence climate-energy policy are an example of public, collective, and indirect environmental action (Elgin & Weible, Citation2013; Jacobsson & Lauber, Citation2006).

Methods

We conducted the study as a “state-of-the-art review” (Grant & Booth, Citation2009) and employed methods common to this genre of research, the purpose of which is to provide readers with an overview of the current state of knowledge on a topic and suggest areas for future research. As such, we did not seek to conduct a comprehensive or exhaustive search, provide a retrospective account of past research, or identify a set of best practices in the field. We did, however, seek to critically assess gaps in current theorizing, methods, and conceptual/empirical findings. We limited the selection of articles to those published either online or in print between 2012 and December 2018 in Environmental Education Research, Journal of Environmental Education, Australian Journal of Environmental Education, and Canadian Journal of Environmental Education. The time period was selected to provide evidence of recent conceptualization within the field. To create a broad sample of recent conceptualization, the review includes reports of quantitative and qualitative research, academic literature reviews, theoretical papers, case study research, curriculum research, evaluation studies, and descriptive research in formal and non-formal settings.

Research articles were selected if the search terms climate or energy appeared in the title, abstract, or keywords of the article. This search generated 77 articles and after seven were excluded based on our selection criteria we analyzed 70 papers. First, we identified and categorized the research objectives, conceptual/theoretical framework, methodology/methods, and main findings/conclusions for each article. Our analysis of the articles focused on categorizing specific conceptual and methodological approaches to researching climate change and energy issues as well as identifying strategies of connection. An Excel spreadsheet was used to document the categorizations of the analysis, and the spreadsheet also captured references that occurred within the text of each article to the action and actor categories articulated in our framework (see and ). We also itemized similarities and differences among the studies in the review related to these categories (e.g., similar conceptions of climate action, divergent conceptions of energy action and literacy) and new emerging categories relevant to our research questions (e.g., environmentally responsible energy behavior, children as change agents). These categories were refined through a series of discussions among the coauthors that focused on a sample of studies representative of the evidence base and then applied across the reviewed literature in a second full-text reading conducted by the first author (Saldaña, Citation2009).

Findings and discussion

In terms of research objectives, methodology, and main findings of the research we reviewed, 54 of the 70 studies in our sample (77%) focused primarily on climate change education and communication, whereas 16 studies (23%) focused primarily on energy education and literacy. This result suggests that EE is significantly more engaged with climate change than energy issues presently. The climate change articles that referenced energy most often in the text were quantitative studies that used individual energy behavior categories as a dependent variable (Bofferding & Kloser, Citation2015; Fusco, Snider, & Luo, Citation2012; Ojala, Citation2012; Walker & Redmond, Citation2014) and climate science studies that conceptualized energy as part of Earth’s climate system (Shepardson, Niyogi, Roychoudhury, & Hirsch, Citation2012; Shepardson, Roychoudhury, Hirsch, Niyogi, & Top, Citation2014). The energy education studies that referenced climate change in the text typically used global concerns about climate change and energy insecurity as a background context and/or rationale for research on promoting energy conservation in the private sector (Aguirre-Bielschowsky, Lawson, Stephenson, & Todd, Citation2017; Petrova, Garcia, & Bouzarovski, Citation2017; Schelly, Cross, Franzen, Hall, & Reeve, Citation2012).

Three of the 70 articles were identified as transition studies (Adlong, Citation2012; Gress & Shin, Citation2017; Mélard & Stassart, Citation2018). In the first of these, Adlong (Citation2012) argued that EE should focus on “a vision of a society powered 100% by renewables” due to promising developments in renewable energy technologies and that a byproduct of these technical developments was “hope” that an adequate response to climate change was possible (p. 127). Because of this, Adlong (Citation2012) argued that EE should “develop the discourses of the large-scale transition to renewable energy, particularly in interaction with social movements” (p. 126) and that knowledge of technical innovations in the renewable energy field was an important aspect of environmental literacy. By contrast, the energy literacy criteria we reviewed emphasized “practical energy-related content knowledge as it relates to students’ own lives” rather than the “formal knowledge required by an energy scientist or professional” (DeWaters & Powers, Citation2013, p. 46).

In addition to Adlong’s (Citation2012) study, Mélard and Stassart (Citation2018) used case study methods to examine a transition experiment in Belgium, a wind energy cooperative that used a regional energy transition as a context for developing an innovative social collaboration between local citizens and professional scientists and engineers to develop new ecological practices. In the third transition study, Gress and Shin (Citation2017) conducted a content analysis of school curriculum and texts in Korea and found clear indications that Korea’s national energy transition policy was driving transitions in curriculum as well. They found that the energy curriculum after middle school had been revised and expanded to include “a new emphasis on renewable energy potential going forward” (p. 878). Gress and Shin (Citation2017) concluded that Korea was cognizant of the role of education “in empowering civil society to drive its green energy transitions” (p. 874). The literature also indicated that climate change education policies in Taiwan and Singapore were focused on empowering young people to influence a large-scale transition to sustainable energy (Chang & Pascua, Citation2017; Lee, Chang, Lai, Guu, & Lin, Citation2017). In each of these national-level cases (Korea, Taiwan, Singapore) state agencies were the primary actors driving curricular reform.

Apart from these studies, our analysis indicated that environmental educators and researchers are focused primarily on changing the energy behavior of individual persons and have effectively “privatized” and individualized the concept of environmental action in this context (Courtenay-Hall & Rogers, Citation2002, p. 290). The most common theme across the studies was energy conservation conceptualized as “climate action” and a form of private sphere pro-environmental behavior (Stern, Citation2000). As discussed following, these focal areas inspire limited connection to the macro-level transformation of energy systems that is occurring, particularly when they remain disconnected from collective actions and innovations in the public sphere.

In multiple articles, researchers used individual energy conservation behavior to measure the effectiveness of educational interventions in environmental education, climate change education, and energy education (). For example, Ojala (Citation2012) used self-reports of energy conservation behavior to examine whether constructive hope about climate change had a statistically significant effect on the pro-environmental behavior of young people when controlling for other factors. We interpreted this preoccupation among researchers as methodological and conceptual residue from an earlier period in EE’s history and evidence that environmental educators and researchers remain positive about energy conservation and behavior modeling research despite the need for a more dynamic and systemic framing of action and change in this context.

Table 3. Recent EE research that uses the energy behavior of individual persons to measure the effectiveness of educational interventions.

Our analysis indicated that energy conservation at the level of individual persons was also being promoted and reinforced in “green” and “net zero” schools through curriculum and instruction, peer-to-peer modeling, teacher modeling, school culture and governance, and building features (Murley, Gandy, & Huss, Citation2017; Schelly et al., Citation2012). We found additional instances where participatory approaches to education (e.g., project-based learning, action research) were conceptualized instrumentally as a means to promote energy conservation and efficiency behaviors (Buchanan, Schuck, & Aubusson, Citation2016; Petrova et al., Citation2017). Establishing personal and social norms regarding energy conservation in the context of individual households and schools was a central concern (Barata, Castro, & Martins-Loução, Citation2017; Buchanan et al., Citation2016). Similarly, households and schools were conceptualized as the primary contexts for action and children and youth the primary agents of change (Aguirre-Bielschowsky et al., Citation2017; Boon & Pagliano, Citation2014; Stevenson, Peterson, & Bondell, Citation2016; Williams, McEwen, & Quinn, Citation2017). By contrast, only two of the empirical articles we reviewed relied on a strong participatory approach to constructing knowledge about climate change (Öhman & Öhman, Citation2013; Stapleton, Citation2015).

The common rationale for these conceptualizations was that children and youth would be the generation most affected by climate change and would be responsible—as future leaders, citizens, and policymakers—for making difficult energy-related decisions in response to climate change. Focusing on everyday contexts and actions was also conceptualized as a way to empower children and youth, increase their understanding and engagement, and avoid the despondency and helplessness that climate change can foster. For example, Aguirre-Bielschowsky et al. (Citation2017) used the energy literacy framework developed by DeWaters and Powers (Citation2013) to conceptualize children’s influence over family members to save electricity as a form of agency. As such, children were conceptualized as “agents encouraging electricity conservation” although this agency was constrained to the level of individual households (p. 846). This bottom-up and intergenerational approach to action and change, where children use messages learned at school to influence the behavior of family members, was also evident in Williams et al.’s (Citation2017) climate adaptation study of flood preparation and household resilience. All of these conceptualizations are aligned with current frameworks for climate change education (Anderson, Citation2012; Mochizuki & Bryan, Citation2015) which recommend that climate change educators focus on “local, tangible and actionable” aspects of climate change that can be “addressed by individual behaviour” (Anderson, Citation2012, p. 197).

Analysis of climate change and energy actions in the reviewed literature provided additional instances of what Jensen (Citation2004) called an “individualistic conception of society” (p. 407). For example, in their study of the effects of different climate change framing statements on citizen scientists’ intentions to act, Dickinson, Crain, Yalowitz, and Cherry (Citation2013) framed collective action as a “large number of people” reducing their energy consumption “a small amount” (p. 149). Similarly, Ignell, Davies, and Lundholm (Citation2018) conceptualized “collective social action” (p. 5) as support among individual persons for market-based government interventions. We interpreted these instances as representing an individualistic conception of collective action—the collective sum of individual actions—rather than social collective action in the sense of action voluntarily taken in common by a group of actors in pursuit of a perceived shared interest (Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2004).

The literature we reviewed suggests that citizens and scientists who are interested in climate change share this more social and political interpretation of collective action. For example, Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012) conducted an exploratory qualitative study of 12 young adult environmentalists and found that although the participants were involved in individual behavior change, they were skeptical of its effectiveness in addressing climate change. Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012) concluded that what the participants lacked was the knowledge and power to engage in the “collective social actions” (p. 58) they believed were truly necessary but had difficulty envisioning. Waldron, Ruane, Oberman, and Morris (Citation2016) interviewed students, teachers, and climate specialists in Ireland and found a clear distinction between specialists’ conceptions of climate change as a social justice issue requiring collective political action and student/teacher conceptions of climate change as a geographical issue requiring action at the level of individual persons. Howell and Allen (Citation2016) surveyed 85 adults involved in climate change education and mitigation and found that their actions were motivated more by social and political concerns than environmental concerns. Fisher (Citation2016) and Stapleton (Citation2018) came to similar conclusions in qualitative studies of climate-engaged youth.

Recommendations toward a more strategic and impactful approach

This review of the recent EE literature at the intersection of climate change and energy education highlights several opportunities for EE. Here we recommend several strategic moves based on the literature we reviewed, additional EE research related to our findings, and the transitions framework articulated earlier in the article. These recommendations will be particularly relevant to EE in nations that are currently very dependent on fossil fuels for their energy supply.

First, we recommend that environmental educators and researchers move beyond pro-environmental behavior as a conceptual basis for action and change in this context. Although measuring changes to individual energy behavior may be methodologically necessary to developing a set of evidence-based practices in the field of climate change education (see Anderson, Citation2012), the conservation efforts of individual persons are unlikely to stimulate a transition toward renewable-based energy systems on their own. In fact, they may contribute more to sustaining the current “sociotechnical regime” (Geels, Citation2010) than transforming it. From a transitions perspective, it would be far more effective to educate children and youth for collective political engagement or careers in the renewable energy sector (Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Jennings, Citation2009). We were, therefore, concerned to find energy conservation projects identified as an effective climate education strategy in a recent systematic review of climate change education research (Monroe, Plate, Oxarart, Bowers, & Chaves, Citation2017).

Our primary concern here is that by focusing on energy conservation and changing personal end-use energy behaviors, environmental educators and researchers are neglecting the politics and policy of energy system transformation (Jacobsson & Lauber, Citation2006) and their responsibility to provide students with a range of options for participating actively in these systemic change processes (Stevenson, Citation2007). By minimizing the role of collective action, environmental educators and researchers may be reinforcing a simplistic and narrow conception of the relationship between climate change, human action, and energy system change and distorting the fact that many of the most impactful climate actions are decisions about energy supply systems that are made by state and market sector actors under direct pressure from advocacy coalitions and other social collectives. For these reasons, we recommend that EE consider Adlong’s (Citation2012) call for the field of EE to become more engaged with social movements related to climate change and the global, system-wide transition to renewable energy and integrate knowledge about social movement actors into its policies and programs. Additional qualitative and mixed-method research along the lines established by Kenis and Mathijs (Citation2012) that explores the interpretations of collective action among students and adult citizens who are interested in the politics of climate change and energy policy would be particularly useful in advancing the understanding of this educational focus.

Second, we recommend that environmental educators and researchers reconceptualize children and youth as actors and innovators within a much broader social network. Although teaching family members and peers about climate change and participating in and promoting energy conservation at home and at school can certainly be empowering, the literature we reviewed provided evidence that children and youth had a difficult time conceptualizing climate change and persuading others to change their actions on their own (Öhman & Öhman, Citation2013; Williams et al., Citation2017). In our view, new forms of participatory EE are required that include spaces for children and youth to interact and experiment with multiple types of actors that are seeking to understand our current situation and create innovative ways of responding. These multiactor networks—which could include climate scientists and activists, renewable energy firms and entrepreneurs, state agencies, NGOs, and community/civic groups—would provide opportunities for children and youth to acquire specialized action-oriented knowledge at the nexus between climate change and energy system change that is difficult to construct through everyday experience in familiar contexts such as home and school. These networks would also allow for the emergence of new and more relational forms of action and agency (Verlie & CCR 15, Citation2018) and promote the kind of co-constructed practice innovations which Dubois and Krasny (Citation2016) argued are necessary if environmental educators and researchers are to play a significant role in addressing climate change moving forward. Although EE researchers have recognized the value of a network-based approach to learning and action in the context of climate change (Boyd & Osbahr, Citation2010; Marcinkowski, Citation2009) and sustainability transitions (Sol, van der Wal, Beers, & Wals, Citation2018), these networks were notably absent from the empirical literature we reviewed.

Third, we recommend that environmental educators and researchers reconsider Adlong’s (Citation2012) recommendation to expand the current conception of energy literacy (DeWaters & Powers, Citation2013) to include knowledge about both technical and social innovation occurring as communities, organizations, and regions of the world transition to renewable-based societies. We are particularly interested in the potential for this knowledge to foster among young people the kind of constructive hope that the literature we reviewed suggests contributes to meaningful action (Li & Monroe, Citation2017; Ojala, Citation2012; Ojala, Citation2015; Ojala, Citation2016). New lines of research are required that examine the relationship between knowledge of technical developments in the renewable energy sector, hope concerning climate change, and participation in collective action to shape energy transitions across a variety of spatial scales.

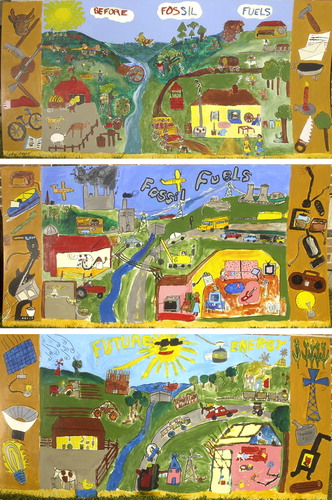

Fourth, we recommend that environmental educators and researchers focus on developing new narratives and guiding visions to support students’ long-term engagement with energy systems and transitions. Research suggests that these discursive features are essential to building collective competence within sustainability transitions, particularly at the regional level (Hermwille, Citation2016; Spath & Rohracher, Citation2010). Despite a few notable exceptions (Adlong, Citation2012; Dunkley, Citation2016; Gress & Shin, Citation2017), the literature we reviewed indicated a general lack of attention to developing competence to envision life in a renewable-based society. Our analysis indicates that this knowledge is sorely needed. For example, Stokas, Strezou, Malandrakis, and Papadopoulou (Citation2017) analyzed the drawings of 104 primary school children in Greece and found no evidence at all to indicate that the children associated “energy generation, distribution, and use with the present and future needs of their town” (p. 1106). Addressing this situation could begin by providing elementary students with simple visual cues associated with energy systems in transition ().

Figure 1. A series of painted murals depicting energy systems past, present, and future. Artist Carolyn Shapiro (Citation2004) working with Champlain Elementary School students through the Vermont Energy Education Program.

The members of the regional wind energy cooperative reported by Mélard and Stassart (Citation2018) developed a renewable-based society not only because of the potential to reduce the risks of climate change but also because of its potential to more equitably distribute economic and political power and specialized ecological knowledge. Building conceptual and practical bridges between transition experiments such as these and others such as renewable energy schools (Buchanan et al., Citation2016) would provide young people with a more coherent vision of life in renewable-based society and examples of environmental action in a broader socio-ecological context (Verlie & CCR 15, Citation2018). Energy experts and activists around the world are working to strengthen community control of energy, weaken corporate control, and resist fossil-fuel reliance because it contributes to a concentration of wealth and power in society as well as all the negative health, safety, and environmental implications (Adlong & Dietsch, Citation2015; Burke & Stephens, Citation2017). Given the powerful educational opportunities associated with envisioning renewable-based society, new forms of EE are required that include opportunities for students to develop these visions and experience the fundamental struggles and structural challenges involved in trying to enact them collectively.

Conclusions

Given that the global systemwide changes at the climate-energy nexus will be increasingly salient in the next decade, this review reveals a distinctive strategic opportunity, and perhaps an important responsibility, for the EE community to engage differently. We found that environmental educators and researchers currently conceptualize environmental action in this context primarily in terms of energy conservation behavior. We also found evidence that the large-scale transition to renewable energy is beginning to emerge within EE discourse through research on regional and national level energy transitions, although EE seems to have not yet embraced promoting action-oriented knowledge about these transitions in its research programs and practices. We recommend that EE adopt a vision and strategy on climate change and energy education that more explicitly addresses the role of collective action, multiactor networks, and sociotechnical innovation in shaping energy transition processes.

References

- Adlong, W. (2012). 100% renewables as a focus for environmental education. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 28(2), 125–155.

- Adlong, W., & Dietsch, E. (2015). Environmental education and the health professions: Framing climate change as a health issue. Environmental Education Research, 21(5), 687–709. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.930727

- Aguirre-Bielschowsky, I., Lawson, R., Stephenson, J., & Todd, S. (2017). Energy literacy and agency of New Zealand children. Environmental Education Research, 23(6), 832–854. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1054267

- Anderson, A. (2012). Climate change education for mitigation and adaptation. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 6(2), 191–206. doi:10.1177/0973408212475199

- Avelino, F., & Wittmayer, J. M. (2016). Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 628–649. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259

- Barata, R., Castro, P., & Martins-Loução, M. A. (2017). How to promote conservation behaviors: The combined role of environmental education and commitment. Environmental Education Research, 23(9), 1322–1334. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1219317

- Bofferding, L., & Kloser, M. (2015). Middle and high school students’ conceptions of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. Environmental Education Research, 21(2), 275–294. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.888401

- Boon, H. J., & Pagliano, P. J. (2014). Disaster education in Australian schools. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 30(2), 187–197. doi:10.1017/aee.2015.8

- Boyd, E., & Osbahr, H. (2010). Responses to climate change: Exploring organisational learning across internationally networked organisations for development. Environmental Education Research, 16(5–6), 629–643. doi:10.1080/13504622.2010.505444

- Buchanan, J., Schuck, S., & Aubusson, P. (2016). In-school sustainability action: Climate clever energy savers. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 32(2), 154–173.

- Burke, M. J., & Stephens, J. C. (2017). Energy democracy: Goals and policy instruments for sociotechnical transitions. Energy Research & Social Science, 33, 35–48. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.024

- Burke, M. J., & Stephens, J. C. (2018). Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Research & Social Science, 35, 78–93.

- Carmi, N., Arnon, S., & Orion, N. (2015). Seeing the forest as well as the trees: General vs. specific predictors of environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research, 21(7), 1011–1028. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.949626

- Chang, C.-H., & Pascua, L. (2017). The curriculum of climate change education: A case for Singapore. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(3), 172–181.

- Chawla, L., & Cushing, D. F. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 437–452.

- Clayton, S., Luebke, J., Saunders, C., Matiasek, J., & Grajal, A. (2014). Connecting to nature at the zoo: Implications for responding to climate change. Environmental Education Research, 20(4), 460–475.

- Courtenay-Hall, P., & Rogers, L. (2002). Gaps in mind: Problems in environmental knowledge-behaviour modelling research. Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 283–297.

- DeWaters, J., & Powers, S. (2013). Establishing measurement criteria for an energy literacy questionnaire. Journal of Environmental Education, 44(1), 38–55.

- Dickinson, J. L., Crain, R., Yalowitz, S., & Cherry, T. M. (2013). How framing climate change influences citizen scientists’ intentions to do something about it. Journal of Environmental Education, 44(3), 145–158.

- Dijkstra, E. M., & Goedhart, M. J. (2012). Development and validation of the ACSI: Measuring students’ science attitudes, pro-environmental behavior, climate change attitudes and knowledge. Environmental Education Research, 18(6), 733–749.

- Dresner, M. (1990). Changing energy end-use patterns as a means of reducing global-warming trends. Journal of Environmental Education, 21(2), 41–46.

- Dubois, B., & Krasny, M. E. (2016). Educating with resilience in mind: Addressing climate change in post-Sandy New York City. Journal of Environmental Education, 47(4), 255–270.

- Dunkley, R. A. (2016). Learning at eco-attractions: Exploring the bifurcation of nature and culture through experiential environmental education. Journal of Environmental Education, 47(3), 213–221.

- Elgin, D. J., & Weible, C. M. (2013). A stakeholder analysis of Colorado climate and energy issues using policy analytical capacity and the advocacy coalition framework. Review of Policy Research, 30(1), 114–133.

- Farla, J., Markard, J., Raven, R., & Coenen, L. (2012). Sustainability transitions in the making: A closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 79(6), 991–998.

- Fischer-Kowalski, M., & Rotmans, J. (2009). Conceptualizing, observing, and influencing social-ecological transitions. Ecology and Society, 14(2), 3.

- Fisher, S. R. (2016). Life trajectories of youth committing to climate activism. Environmental Education Research, 22(2), 229–247.

- Friedman, T. L. (2008). Hot, flat, and crowded. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

- Fusco, E., Snider, A., & Luo, S. (2012). Perception of global climate change as a mediator of the effects of major and religious affiliation on college students’ environmentally responsible behavior. Environmental Education Research, 18(6), 815–830. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.672965

- Geels, F. W. (2010). Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Research Policy, 39(4), 495–510. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.022

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2007). Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36(3), 399–417. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Gress, D. R., & Shin, J. (2017). Potential for knowledge in action? An analysis of Korean green energy related K3-12 curriculum and texts. Environmental Education Research, 23(6), 874–885. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1204987

- Grin, J., Rotmans, J., & Schot, J. (2011). On patterns and agency in transition dynamics: Some key insights from the KSI programme. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 76–81. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2011.04.008

- Hermwille, L. (2016). The role of narratives in socio-technical transitions–Fukushima and the energy regimes of Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 237–246. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2015.11.001

- Honnold, J. A., & Nelson, L. D. (1978). Public opinion regarding energy conservation. Journal of Environmental Education, 9(4), 20–29. doi:10.1080/00958964.1978.10801876

- Howell, R. A., & Allen, S. (2016). Significant life experiences, motivations and values of climate change educators. Environmental Education Research, 1–19. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1158242

- Ignell, C., Davies, P., & Lundholm, C. (2018). A longitudinal study of upper secondary school students’ values and beliefs regarding policy responses to climate change. Environmental Education Research, 1–18. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1523369

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2018). Global warming of 1.5 °C: IPCC special report. Geneva: IPCC.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (Ed.). (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC.

- Jacobsson, S., & Lauber, V. (2006). The politics and policy of energy system transformation–Explaining the German diffusion of renewable energy technology. Energy Policy, 34(3), 256–276.

- Jennings, P. (2009). New directions in renewable energy education. Renewable Energy, 34(2), 435–439.

- Jensen, B. B. (2002). Knowledge, action and pro-environmental behaviour. Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 325–334.

- Jensen, B. B. (2004). Environmental and health education viewed from an action-oriented perspective: A case from Denmark. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(4), 405–425.

- Kenis, A., & Mathijs, E. (2012). Beyond individual behavior change: The role of power, knowledge and strategy in tackling climate change. Environmental Education Research, 18(1), 45–65.

- Kil, N. (2016). Effects of vicarious experiences of nature, environmental attitudes, and outdoor recreation benefits on support for increased funding allocations. Journal of Environmental Education, 47(3), 222–236.

- Lee, L.-S., Chang, L.-T., Lai, C.-C., Guu, Y.-H., & Lin, K.-Y. (2017). Energy literacy of vocational students in Taiwan. Environmental Education Research, 23(6), 855–873.

- Lee, L.-S., Lin, K.-Y., Guu, Y.-H., Chang, L.-T., & Lai, C.-C. (2013). The effect of hands-on “energy-saving house” learning activities on elementary school students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding energy saving and carbon-emissions reduction. Environmental Education Research, 19(5), 620–638.

- Li, C. J., & Monroe, M. C. (2017). Exploring the essential psychological factors in fostering hope concerning climate change. Environmental Education Research, 1–19. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1367916

- Marcinkowski, T. J. (2009). Contemporary challenges and opportunities in environmental education: Where are we headed and what deserves our attention? Journal of Environmental Education, 41(1), 34–54.

- McLeod, J. M., Glynn, C. J., & Griffin, R. J. (1987). Communication and energy conservation. Journal of Environmental Education, 18(3), 29–37.

- Meadowcroft, J. (2011). Engaging with the politics of sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 70–75. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.003

- Meinzen-Dick, R., DiGregorio, M., & McCarthy, N. (2004). Methods for studying collective action in rural development. Agricultural Systems, 82(3), 197–214.

- Mélard, F., & Stassart, P. M. (2018). The diplomacy of practitioners: For an ecology of practices about the problem of the coexistence of wind farms and red kites. Environmental Education Research, 24(9), 1359–1370.

- Mochizuki, Y., & Bryan, A. (2015). Climate change education in the context of education for sustainable development: Rationale and principles. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 9(1), 4–26.

- Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A., & Chaves, W. A. (2017). Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the literature. Environmental Education Research, 1–22. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842

- Murley, L. D., Gandy, S. K., & Huss, J. M. (2017). Teacher candidates research, teach, and learn in the nation’s first net zero school. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(2), 121–129. doi:10.1080/00958964.2016.1141747

- Öhman, J., & Öhman, M. (2013). Participatory approach in practice: An analysis of student discussions about climate change. Environmental Education Research, 19(3), 324–341. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.695012

- Ojala, M. (2012). Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environmental Education Research, 18(5), 625–642. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.637157

- Ojala, M. (2015). Hope in the face of climate change: Associations with environmental engagement and student perceptions of teachers’ emotion communication style and future orientation. Journal of Environmental Education, 46(3), 133–148. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662

- Ojala, M. (2016). Facing anxiety in climate change education: From therapeutic practice to hopeful transgressive learning. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 21, 41–56.

- Palmer, J. A. (1998). Environmental education in the 21st century: Theory, practice, progress, and promise. London: Routledge.

- Petrova, S., Garcia, M. T., & Bouzarovski, S. (2017). Using action research to enhance learning on end-use energy demand: Lessons from reflective practice. Environmental Education Research, 23(6), 812–831. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1144177

- Princen, T., Manno, J. P., & Martin, P. L. (Eds.). (2015). Ending the fossil fuel era. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Sauvé, L. (2005). Currents in environmental education: Mapping a complex and evolving pedagogical field. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 10, 11–37.

- Schelly, C., Cross, J. E., Franzen, W., Hall, P., & Reeve, S. (2012). How to go green: Creating a conservation culture in a public high school through education, modeling, and communication. Journal of Environmental Education, 43(3), 143–161.

- Shapiro, C. (2004). Energy systems past, present, and future [Painting]. Burlington, VT: Champlain Elementary School, Vermont Energy Education Program.

- Shepardson, D. P., Niyogi, D., Roychoudhury, A., & Hirsch, A. (2012). Conceptualizing climate change in the context of a climate system: Implications for climate and environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 18(3), 323–352.

- Shepardson, D. P., Roychoudhury, A., Hirsch, A., Niyogi, D., & Top, S. M. (2014). When the atmosphere warms it rains and ice melts: Seventh grade students’ conceptions of a climate system. Environmental Education Research, 20(3), 333–353.

- Shove, E., & Walker, G. (2010). Governing transitions in the sustainability of everyday life. Research Policy, 39(4), 471–476.

- Sol, J., van der Wal, M. M., Beers, P. J., & Wals, A. E. J. (2018). Reframing the future: The role of reflexivity in governance networks in sustainablity transitions. Environmental Education Research, 24(9), 1383–1405.

- Spath, P., & Rohracher, H. (2010). “Energy regions”: The transformative power of regional discourses on socio-technical futures. Research Policy, 39(4), 449–458.

- Stapleton, S. R. (2015). Environmental identity development through social interactions, action, and recognition. Journal of Environmental Education, 46(2), 94–113.

- Stapleton, S. R. (2018). A case for climate justice education: American youth connecting to intragenerational climate injustice in Bangladesh. Environmental Education Research, 1–19. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1472220

- Sterling, S. (2001). Sustainable education: Re-visioning learning and change. Bristol, UK: Schumacher Society.

- Stern, P. C. (2000). Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424.

- Stevenson, K. T., King, T. L., Selm, K. R., Peterson, M. N., & Monroe, M. C. (2018). Framing climate change communication to prompt individual and collective action among adolescents from agricultural communities. Environmental Education Research, 24(3), 365–377.

- Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., & Bondell, H. D. (2016). The influence of personal beliefs, friends, and family in building climate change concern among adolescents. Environmental Education Research, 1–14. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1177712

- Stevenson, R. (2007). Schooling and environmental education: Contradictions in purpose and practice. Environmental Education Research, 13(2), 139–153.

- Stokas, D., Strezou, E., Malandrakis, G., & Papadopoulou, P. (2017). Greek primary school children’s representations of the urban environment as seen through their drawings. Environmental Education Research, 23(8), 1088–1114.

- Tainter, J. A. (2011). Energy, complexity, and sustainability: A historical perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 89–95.

- Verlie, B, & CCR 15. (2018). From action to intra-action? Agency, identity, and “goals” in a relational approach to climate change education. Environmental Education Research, 1–15. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2018.1497147

- Waldron, F., Ruane, B., Oberman, R., & Morris, S. (2016). Geographical process or global injustice? Contrasting educational perspectives on climate change. Environmental Education Research, 1–17. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1255876

- Walker, B., & Redmond, J. (2014). Changing the environmental behaviour of small business owners: The business case. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 30(2), 254–268.

- Williams, S., McEwen, L. J., & Quinn, N. (2017). As the climate changes: Intergenerational action-based learning in relation to flood education. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(3), 154–171.

- Yang, J. C., Lin, Y. L., & Liu, Y.-C. (2017). Effects of locus of control on behavioral intention and learning performance of energy knowledge in game-based learning. Environmental Education Research, 23(6), 886–899.